#Zen Master Rinzai

Text

Morning Meditaton — Because you've little faith.

Morning Meditaton — Because you've little faith.

https://wp.me/pFy3u-8xV

‘Followers of the way, because you’ve little faith, you run about seeking your head which you think you’ve lost.’

Zen Master Rinzai

Tulips.

On our Twitter account, Buddhism Now @Buddhism_Now, most mornings we post a ‘morning meditation’ like the one above.

On the net, of course, it’s morning, afternoon, evening, or nighttime 😀 somewhere.

Click here to read more Morning Meditation…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

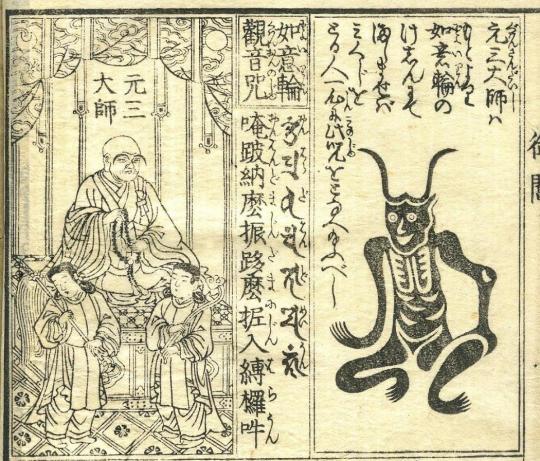

Horned hermits and immoral immortals: an inquiry into Zanmu's background

As you might remember from my previous post covering Zanmu, I was initially unable to tell how her historical background led to ZUN choosing to make her an oni. The historical, or at least legendary, Zanmu seemed to be, for all intent and purposes, a human. That has since changed, and the matter now seems considerably more clear to me. Read on to learn more about the real monk Zanmu is based on, and to find out what she has in common with the most famous Zen master in history, Taoist immortals, and Tsuno Daishi.

Even if you are not particularly interested in Zanmu, this article might still worth be checking out, seeing as the discussed primary sources are also relevant to a number of other Touhou characters, including Byakuren, Yoshika and Kasen.

As in the case of the previous Touhou article, special thanks go to @just9art, who helped me with tracking down sources advised me while I was working on this.

The historical Zanmu

Statue of Zanmu from the Sazaedo pagoda (Fukushima Travel; reproduced for educational purposes only)

As already pointed out by 9 here even before my previous post about Unfinished Dream of All Living Ghost, Zanmu is based on a real monk also named Zanmu. His full name was Nichihaku Zanmu (日白残夢), and he also went by Akikaze Dōjin, but even Japanese wikipedia simply refers to him as Zanmu. ZUN basically just swapped one kanji in the name, with 日白残夢 becoming 日白残無. The character 無, which replaces original 夢 (“dream”), means “nothingness” - more on that later.The search for sources pertaining to the historical Zanmu has tragically not been very successful. In contrast with some of the stars of the previous installments, like Prince Shotoku or Matarajin, he clearly isn’t the central topic of any monographs or even just journal articles. Ultimately the main sources to fall back on are chiefly offhand mentions, blog articles and some tweets of variable trustworthiness.

The only academic publication in English I was able to locate which mentions Zanmu at all is the Japanese Biographical Index from 2004, published by De Gruyter. The price of this book is frankly outrageous for what it is, so here’s the sole mention of him screencapped for your convenience:

The book referenced here is the five volume biographical dictionary Dai Nihon Jinmei Jisho from 1937. I am unable to access it, but I was nonetheless able to cobble together some information about Zanmu from other sources.

Not much can be said about Zanmu’s personal life. He was a Buddhist monk (though note a legend apparently refers to him as “neither a monk nor a layperson”, a formula typically designating legendary ascetics and the like) and a notable eccentric. Both of these elements are present in the bio of his Touhou counterpart.

The Sazaedo pagoda (Fukushima Travel; reproduced for educational purposes only)

Zanmu’s tangible accomplishments seem to be tied to the temple Shoso-ji, which he apparently founded. He is enshrined in the Sazaedo pagoda near it, though this building postdates him by over 200 years. It’s located in Aizuwakamatsu in Fukushima. You can see some additional photos of his statue displayed there in this tweet. It’s a pretty famous location due to its unique double helix structure, and it has a pretty extensive article on the Japanese wikipedia. It’s also covered on multiple tourist-oriented sites in English, where more photos are available (for example here or here). There’s even a model kit representing it out there. Sazeado’s fame does not really seem to have anything to do with Zanmu, though.

While many Buddhist figures ZUN used as the basis for Touhou characters in the past belonged to the “esoteric” schools (Tendai and Shingon), Zanmu was a practitioner of the much better known Zen, specifically of the Rinzai school.

The kanji mu (無 ) caligraphed by Shikō Munakata (Saint Louis Art Museum; reproduced for educational purposes only)

Since the concept of “nothingness” or “emptiness” represented by the kanji 無 (mu) plays a vital role in Zen (see here or here for a more detailed treatment of this topic; it’s covered on virtually every Zen-related website possible though), and there’s even a so-called mu kōan, it strikes me as possible this is the reason behind the slightly different writing of the names of ZUN’s Zanmu, as well as the source of her ability. Granted, the dialogue in the games makes it sound like Zanmu (and by extension Hisami) just talks about nothingness as a memento mori of sorts, which is not quite what it entails in Zen. Of course, ZUN does not adapt Buddhist doctrine 1:1 (lest we forget Kasen seemingly being unaware of the basics of Mahayana in WaHH) so this point might be irrelevant.

The legendary Zanmu

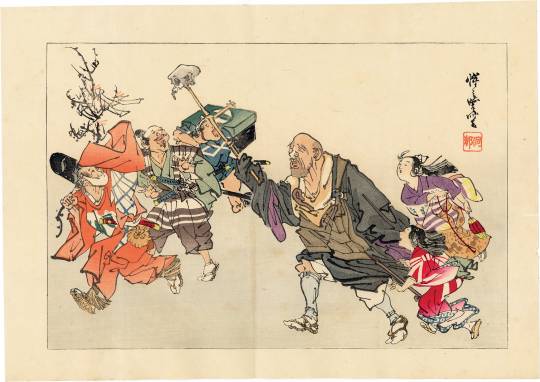

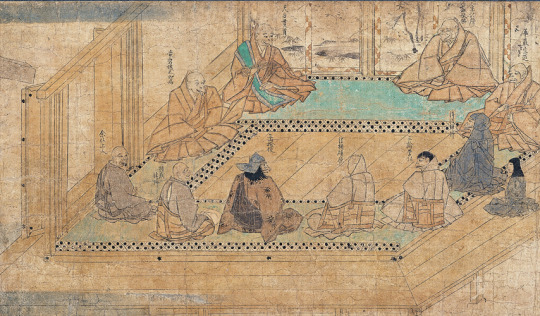

The eccentric monk Ikkyū (center), as imagined by Kawanabe Kyōsai (Egenolf Gallery; reproduced for educational purposes only)

A number of legends developed around the historical Zanmu. If this blog post is to be trusted, there is a tradition according to which he was a student of arguably the most famous member of the Rinzai school, and probably one of the most famous Buddhist monks in the history of Japan in general, Ikkyū. He is remembered as the archetypal eccentric monk, and spent much of his life traveling as a vagabond due to his disagreements with Buddhist establishment and unusual personal views on matters such as celibacy. As I already said in my previous article pertaining to Zanmu, long time readers of my blog might know Ikkyū from the tale of Jigoku Dayū and art inspired by it, though since this motif only arose in the Edo period it naturally does not represent an actual episode from his very much real career.

A page from Ikkyū Gaikotsu (wikimedia commons)

In art a distinct tradition of depicting Ikkyū with skeletons developed, as seen both in the case of works showing him with his legendary student Jigoku Dayū and in the so-called Ikkyū Gaikotsu. Skeletons also played a role in Zen-inspired art in general (for more information see here). Whether this inspired ZUN to decorate Zanmu’s rock with bones is hard to determine, but it does not seem implausible. It would hardly be the deepest art history cut in the series, less arcane of a reference than the very existence of Mai and Satono or Kutaka’s pose.

Obviously, it does not seem very plausible that Ikkyū ever actually met the historical Zanmu. Ikkyū passed away in 1481, and Zanmu in 1576, with his birth date currently unknown. Even if we assume he was a particularly long-lived individual and by some miracle was born while Ikkyu was still alive, it is somewhat doubtful that an elderly sick monk would be preaching Zen doctrine to an infant. However, apparently legends do provide a convenient explanation for this tradition. Purportedly Zanmu lived for an unusually long time. The figure of 139 years pops up online quite frequently, and does seem to depend on a genuine tradition, but even more fabulous claims are out there.

Kaison Hitachibō, as imagined by an unknown artist (wikimedia commons)

According to another legend, Zanmu was even older, and in fact remembered the Genpei war, which took place in the Heian period - nearly 400 years before his time. Supposedly he told many vivid tales about its famous participants, Yoshitsune and Benkei. A tradition according to which he was himself originally a legendary retainer of Yoshitsune, the warrior monk Kaison Hitachibō (常陸坊海尊) developed at some point. This has already been pointed out by others before me in relation to the Touhou version of Zanmu. From what I’ve seen, some Japanese fans in fact seem excited primarily about the prospect of Zanmu offering an opportunity to connect Touhou and works focused on the Genpei war.

The tradition making Zanmu a centuries-old survivor from the Heian period must be relatively old, as his supposed immortality is already mentioned in Honchō Jinja Kō (本朝神社考; “Study of shrines”) by Razan Hayashi, who was active in the first half of the seventeenth century, mere decades after Zanmu’s death. While I found no explicit confirmation, it seems sensible to assume this legend was already in circulation while Zanmu was still alive, or at least that it developed very shortly after he passed away. Perhaps he really was invested in accounts of that period to the point he sounded as if he actually lived through it.

The choice of Kaison as Zanmu’s original name in the legend does not seem random, as there was a preexisting tradition according to which this legendary Heian figure was cursed with eternal life for betraying Yoshitsune by fleeing from the battlefield instead of remaining with his lord to die. You can read more about this here. Apparently there is a version where he instead becomes immortal to make it possible to pass down the story of the Genpei war to future generations (this is the only source I have to offer though), and there's even a well-received stage play based on it, Hitachibō Kaison (translated as "Kaison, priest of Hitachi") by Matsuyo Akimoto.

Another thing worth pointing out is that Kaison was seemingly a Tendai monk from Mount Hiei, which means that even though Okina isn’t in a new game, you can still claim she’s metaphorically casting her shadow over it in some way if you squint (and that’s without going into the fact sarugami are associated with Mount Hiei). I've seen two separate sources which mention that according to a legend he trained Benkei there, and that the two did not get along because Kaison was a corrupt monk (lustful, keen on substance abuse, greedy, the usual routine). You can access them here and here,but bear in mind they're old.

Zanmu’s Genpei war connection does not really seem to matter in Touhou, though, as ZUN pretty explicitly situated his version in the Sengoku period, with no mention of earlier events. Granted, if you like it, this should not prevent you from embracing the view that Zanmu is an alter ego of Kaison as your headcanon - as I said people are already doing that. It seems equally fair game as “Okina is Hata no Kawakatsu”, easily one of the most popular “historical” headcanons in the history of the franchise.

According to this twitter thread, the legends about Zanmu’s longevity (or immortality) have a pretty long lifespan themseles, as they were referenced by relatively high profile modern writers, like Orikuchi Shinbou and Tatsuhiko Shibusawa.

Buddhist immortals

A word carving of a sennin, "immortal" or "hermit" (wikimedia commons)

Legends about long-lived (or outright immortal) monks, such as Zanmu or Kaison, are hardly uncommon. A work which seems to be the key to understanding their early development, and by extension possibly also the portrayal of Zanmu in Touhou, might be Honchō Shinsenden, “Records of Japanese Immortals”. This title refers to a collection of setsuwa, short stories typically meant to convey religious knowledge or morals. Its title pretty much tells you what to expect.

Honchō Shinsenden is an interesting work in that while it in theory deals with Buddhism, and largely describes the individual immortals as, well, Buddhists, it ultimately reflects a Taoist tradition. There is a strong case to be made that it was an inspiration for another Touhou installment, specifically Ten Desires, already, seeing as it mentions prince Shotoku and Miyako no Yoshika and its Taoist-adjacent context has a long paper trail in scholarship, but I will not go too deep into that topic here - expect it to be covered in a separate article later on.

Stories of immortals are pretty schematic, and their protagonists can be categorized as belonging to a number of archetypes. I think it’s safe to say this has a lot to do with the self-referential character of this sort of literature - compilers of new works were obviously familiar with their forerunners, and imitated them for the sake of authenticity. In China, literary accounts of the lives of immortals circulated as early as in the first century BCE, with the concept of immortals (xian, 仙, read as sen in Japanese; this term and its derivatives have various other translations too, with Touhou media generally favoring “hermit”) itself already appearing slightly earlier.

It seems Shenxian Zhuan (Biographies of Spirit Immortals) by a certain Ge Xuan, certified immortals enthusiast and cinnabar-based immortality elixir connoisseur (discussing and developing immortality elixirs was a popular pastime for literati in ancient and medieval China), can in particular be considered the inspiration for the later Japanese compilation.

While the concept of immortals was largely developed by Taoists, tales focused on them were already not strictly the domain of Taoism by the time they reached Japan. They were embraced in Chinese culture in general, both in strictly religious context and more broadly in art. In Japan, they came to be incorporated into Buddhist worldview, and in fact Honchō Shinsenden states that their protagonists can be understood as “living Buddhas” (ikibotoke), a designation used to refer to particularly saintly Buddhists. Their devotion to both Buddhas and other related figures, and to local kami, is stressed multiple times too.

Presumably this was the result of the influence of the Japanese Buddhist concept of hijiri (聖), a type of particularly rigorous solitary ascetic in popular imagination regarded as almost divine. Needless to say, most of you are actually familiar with the hijiri even if you never read about them, as this is the source of Byakuren’s surname and a clear influence on her character too. In Honchō Shinsenden, it is outright said that the sign 仙, normally read as sen, should be read as hijiri in this case.

A portrait of Huisi (wikimedia commons)

The notion of extending one’s lifespan was not incompatible with Buddhism, as evidenced by tales of adepts who lived for a supernaturally long period of time to show their compassion to more beings or to get closer to the coming of Maitreya. Even the founder of the Tiantai school of Buddhism (the forerunner of Japanese Tendai), Huisi, was said to meditate in hopes of extending his life to witness Maitreya. At the same time, Chinese compilations of stories about immortals do not list Buddhists among them, in contrast with Japanese ones. This might be due to the rivalry between these religions which was at times rather pronounced in Tang China, culminating in events such as emperor Wuzong's persecution of Buddhism.

Let’s return to Honchō Shinsenden, though. Its original author was most likely Ōe no Masafusa, active in the second half of the eleventh century. No full copy survives, but the original contents can nonetheless be restored based on various fragmentary manuscripts. Some of the sections are preserved as quotations in other texts or in larger compilations of stories, too. I have seen claims online that the historical Zanmu is covered in some editions of the Honchō Shinsenden or works dependent on it. So far I was only able to determine with certainty that Zanmu is covered alongside the immortals from Honchō Shinsenden in at least one modern monograph (Nishi-Nihon-hen by Kōsai Chigiri; if anyone of you have access to it I’d be interested to learn what exactly it says about Zanmu) and a number of posts and articles online. However, he lived around 400 years after this work was completed, so he quite obviously does not appear in its original version, contrary to what the Touhou wiki says right now.

Masafusa does not necessarily portray the immortals as pinnacles of morality, and indeed moral virtues do not seem to be a prerequisite for attaining this status in his work. It is therefore possible that despite being setsuwa, his tales of immortals were an entirely literary endeavor and were not meant to evoke piety, let alone promote the worship of described figures.

A recurring pattern which unifies all of these tales is describing immortals as eccentric. As I already noted, this is a distinct characteristic of the historical Zanmu too, and it comes up in the bio of his Touhou counterpart as well. She has “reached the absolute pinnacle of eccentricity”. It seems safe to say ZUN is aware of that pattern, then, and consciously chose to highlight this. He also stresses that Zanmu has lived through an era of marital strife, specifically through the Sengoku period. The inclusion of such episodes is another innovation typical for Japanese immortal tales, and does appear to be a feature of the tradition pertaining to Zanmu’s counterpart too, as discussed above.

Horned hermits?

A modern devotional statuette of Laozi with horns, found on ebay of all places; reproduced here for educational purposes only.

There is a further possible feature of Zanmu that might be tied to Honchō Shinsenden. While there are numerous physical traits attributed to immortals in Chinese sources, Masafusa decided to only ever highlight two. One of them are unusual bones, the other - horns on the forehead. Tragically one of my favorites, square pupils (mentioned in Liexian Zhuan), is missing. Masafusa relays that an anonymous hijiri, the “Rod-Striking Immortal”, grew stumpy horns as a sign of attaining his supernatural status.This might be a stretch, but perhaps Zanmu, due to being the Touhou version of a legendary immortal, also already had horns before becoming an oni. You have to admit it would be funny.

The two horns - or rather small bumps, based on available descriptions - characteristic for some immortals were known as rijiao (日角; “sun-horn”) and yuenxuan (月懸; “moon crescent”). Such unusual physical features were already attributed to various legendary and historical rulers and sages in China in the first century CE, so this is not really a Taoist invention, but rather an adoption of beliefs widespread in China in the formative years of this religion. They also intersected with the early Buddhist tradition about the so-called “32 marks of the Buddha”, documented for example in Mahāvastu and later in Chinese Mahayana tradition which Taoist authors were familiar with. Yu the Great, the flood hero, was among the legendary figures said to possess horns in Chinese tradition. It is even sometimes believed Laozi had them when he was born, which according to Livia Kohn was meant to symbolically elevate him to the rank of such mythical figures as Fuxi.

While this is ultimately a post focused on Zanmu, I think it’s worth pointing out this belief in horned ascetics has very funny implications for Kasen. Being a “horned hermit” is not really an issue, it would appear. If anything, it adds a sense of authenticity. Clearly Kasen needs to study the classics more.

Immortals (and mortals) in hell

One last connection between Zanmu and legends about immortals is her role as an official in hell. However, this is much less directl. Early Chinese sources mention “Agents Beneath the Earth” (dixia zhu zhe 地下主者), a rank available to low class immortals choosing to serve in the land of the dead. They could be contrasted with the immortals inhabiting heaven, regarded as higher ranked than them. However, note that there are also many narratives focused on mortals becoming officials in hell - in Japan arguably the most famous case is the tale of Ono no Takamura, a historical poet from the early Heian period. In Chinese culture there are multiple examples but I think none come close to the popularity of judge Bao. It does not seem any immortals playing a similar role retain equal prominence in culture.

Ultimately this paragraph is only a curiosity, and a much closer parallel to Zanmu's role in hell exists - and it’s connected to materials ZUN already referenced to booth.

Corrupt monks, oni and tengu

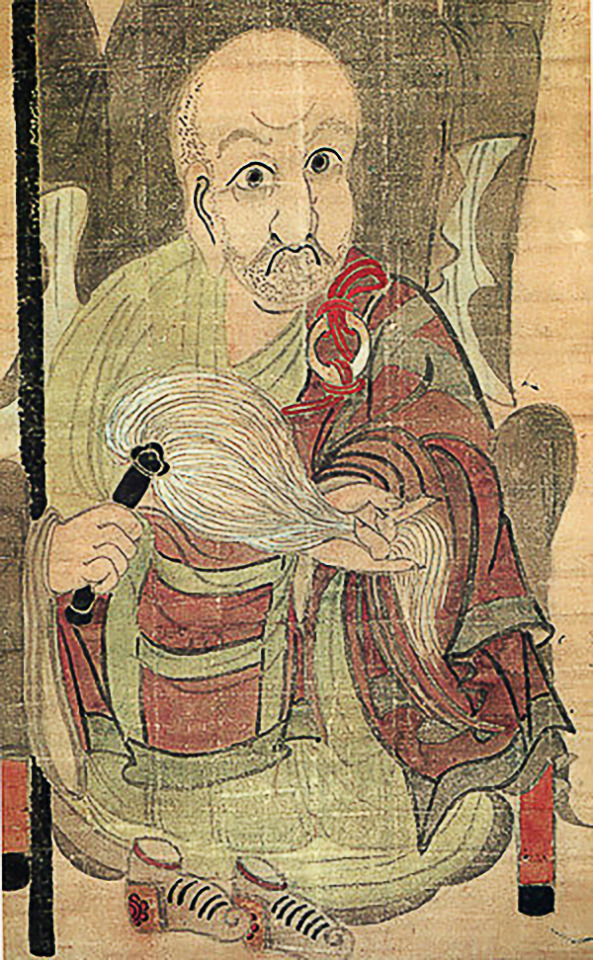

Ryōgen, the most famous monk turned demon, and his alter ego Tsuno Daishi (wikimedia commons)

In addition to characterizing Zanmu as eccentric, ZUN also wrote in her bio that she is a corrupt monk. As we learn, she developed a belief that the best way to reconcile the Sengoku period ethos which demanded boasting about the number of enemies killed with Buddhist precepts was to focus on spirits rather than the living, since she will basically deliver salvation to them. She ultimately “absorbed some beast-youkai spirits, thus discarding her life as a human”. This to my best knowledge does not really match any genuine tradition about the historical Zanmu, related figures or anyone else. As far as I can tell, it’s hard to find a direct parallel either in irl material or elsewhere in Touhou... at least if we stick to the details. More vaguely similar examples are not only attested, discussing them was for a time arguably the backbone of Buddhist discourse in Japan, and neatly explains why Zanmu became an oni.

The idea that monks who broke Buddhist precepts in some way turned into monsters is not ZUN’s invention. It first appears in sources from the Heian period, and gained greater relevance in the Kamakura period. Particularly commonly it was asserted that members of Buddhist clergy who fail to attain nirvana turn into tengu. However, oni were an option too. Bernard Faure points out that Ryōgen, the archetypal example of a fallen monk (see here for a detailed discussion of this topic, and of his return to grace as a demon keeping other demons at bay), could be described as reborn as an oni, for example. The Shingon monk Shinzei is variously described as turning into an oni, a tengu or an onryō (vengeful spirit). Oni are also referenced in a similar context in Heike Monogatari alongside tenma, a term referring to demons obstructing enlightenment in general.

Corrupt monks turned into tengu in the Tengu Zoshi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

Typically it was believed that monks who turned into demons went to a realm variously known as makai, tengudō or madō. As you may know, normally there are three realms one should avoid reincarnating in - beasts, hungry ghosts and hell - but this was basically a bonus fourth one. Granted, this view was not recognized universally, and the alternative interpretation was that it was just a specific hell with a distinct name.

At the absolute peak of this concept’s relevance, the foremost Buddhist thinkers of these times, including Nichiren, were accusing each other of being demons. Additionally, some of the past emperors, especially Sutoku and Goshirakawa, could be presented as tengu, for example in Hōgen monogatari. There was also an interest in finding gods who could keep the forces of disorder at bay. You can see echoes of these beliefs in rituals pertaining to Matarajin, which ZUN rather explicitly referenced in Aya's route in Hidden Star in Four Seasons.

Typically the reason behind transformation into an oni, tengu or another vaguely similar being were earthly attachments. Alternatively, it could be pursuing gejutsu, “outside arts”, essentially teachings which fell outside of what was permitted by Buddhism. Note this does not necessarily mean anything originating in religions other than Buddhism, though, the term is more nuanced. So, for instance worship of kami or following Confucian values are perfectly fair game. A synonymous term was gedō, “heretical” way (on the use of the term “heresy” in the context of study of Buddhism see here). We can make a case for Zanmu’s bio alluding to that - she wanted to adhere to the social norms of the Sengoku period by symbolically taking in a headcount by absorbing spirits, I suppose. That’s not really a thing in any Buddhist literature, though, and I assume ZUN came up with this himself.

Conclusion

While this article is slightly less rigorous than my recent research ventures pertaining to Matarajin, let alone the Mesopotamian wiki operations, I hope it nonetheless sheds some additional light on Zanmu. I will admit I already liked her even before I started digging into the possible inspiration behind her, and finding out more only strengthened my enthusiasm.

While there are clear parallels between Zanmu, her namesake and a variety of other characters from Japanese and Chinese literature and religions, as usual for a character made by ZUN her strength lies both in creative repurposing of these elements and in adding something new.

Postscriptum: Zanmu and Tang Sanzang?

Xuanzang, as depicted by an unknown Qing artist (wikimedia commons)

While much about Zanmu’s character - her backstory as an eccentric fallen monk who became a demon, her apparent zen theme, and so on - all form a coherent whole, there is a tiny detail which does not really match anything else discussed in this article.

It does not come from her dialogue or bio, but rather from Enoko’s. As we learn, she became immortal herself after eating a piece of Zanmu’s body back when the latter was still a human. Or rather, the combination of that and subsequently consuming a magical gemstone as recommended by Zanmu did it - I’m pretty sure I misread this before. As 9 pointed out to me, probably the implications are just that Enoko’s backstory is a partial reference to Perfect Memento in Strict Sense, which does state that consuming the flesh of a monk would be a particularly suitable way for an ordinary animal to turn into a youkai.

Still, comparisons between this tidbit and Journey to the West have been made by others before already, so I figured it would be suitable to address them here even if they lie beyond my own argument about the inspiration behind Zanmu. In this novel, many demons want to devour its protagonist Tang Sanzang because his flesh is said to make anyone who consumes immortal. This is because he is a reincarnation of Master Golden Cicada (Jinchan zi, 金蟬子), a disciple of the Buddha invented for the sake of the story. Interestingly, Sanzang is portrayed as an adherent of Chan Buddhism, the school from which Japanese Zen is derived (note that his historical forerunner Xuanzang belonged to the Yogācāra tradition instead).

Despite the vague similarities, I ultimately do not think there are particularly close parallels between Zanmu and Sanzang. For starters, Zanmu is meant to be a corrupt monk, while Sanzang is the opposite of that. Their respective characters couldn’t differ more either. Throughout the entire novel, Sanzang is a pretty poor planner, shows doubt in his own abilities, and regularly misjudges the situation. Needless to say this does not exactly offer a good parallel to Zanmu. Sure, she creates a bootleg Wukong, but Sanzang did not create Wukong, the famous primate was just assigned to him as a bodyguard. Therefore, until evidence on the contrary appears (for example in an interview) I would personally remain cautiously pessimistic regarding a possible connection here.

Recommended reading

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Noga Ganany, Baogong as King Yama in the Literature and Religious Worship of Late-Imperial China

Zornica Kirkova, Roaming into the Beyond: Representations of Xian Immortality in Early Medieval Chinese Verse

Christoph Kleine & Livia Kohn, Daoist Immortality and Buddhist Holiness: A Study and Translation of the Honchō shinsen-den

Livia Kohn, The Looks of Laozi

James Robson, The Institution of Daoism in the Central Region (Xiangzhong) of Hunan

Haruko Wakabayashi, From Conqueror of Evil to Devil King: Ryogen and Notions of Ma in Medieval Japanese Buddhism

Idem, The Seven Tengu Scrolls. Evil and the Rhetoric of Legitimacy in Medieval Japanese Buddhism

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recommendation to be a "Great Fool"

Just being selfless will enable us to think of ourselves as being in the other person's situation. Just being a great fool will turn suffering into non suffering. And being selfless and a “great fool” will allow us to act from a true, sincere heart.

1, The state of mind of the famous Japanese Zen monk, Ryokan.

There is a short poem entitled "Okiagari-koboshi," which refers to a traditional Japanese toy called "Daruma" (a kind of roly-poly doll that bounces back up when knocked down).

"Just being tossed around or laughed at.

Not being bothered by this at all.

In my opinion, if my life were like yours (Daruma),

then I would be able to live without any cares."

In this poem, Ryokan, who called himself a "great fool," is in fact revealing the secret to living a peaceful life. We show emotions in situations and are not able to imitate the doll Daruma by bouncing back when difficulties knock us down. If we were to just go along with the circumstances, not upset by anything that comes our way, all difficulties would disappear naturally.

Ryokan is also famous for saying,

"When encountering disaster, just let it come.

When facing death, just accept it."

This is saying the same thing as the "Okiagari-koboshi" poem. Therefore, Ryokan stated confidently that this is in fact “the unique way to avoid disasters." It is the state of mind of a "great fool," and it has been said that Ryokan was the best example of someone who indeed lived this kind of life.

2, Suffering Comes from Our Attachments

Illusions and attachment create our worries and suffering. The Buddha has emphasized this. Being attached to things gives rise to our ego-consciousness and makes us act selfishly, only thinking about ourselves. What is more, because we don't think about others first, quarrels and battles have continued ceaselessly in this world. Anyone can easily see that this is true by looking at the world situation of today.

Eastern saints and sages, the Buddha and the patriarchs; they were all concerned with this situation. They emphasized the necessity of learning the "way of saints" by studying the classics, and of cultivating the state of "selflessness"-- the way of the "great fool."

The truth is that there is nothing we should be attached to as “my own possession.” Even though we are each very attached to our own body, we still aren't able to keep it for ever. However, this uncertainty is in truth good news, because it teaches us that we don't have to suffer by trying to hold on to our own egoistic self.

Even though we have the impression that we possess permanent substance of our own, there is really nothing permanent or substantial at all. The ancients have described this situation in the following poem.

"Gathering grass and making lumber from trees permits us to build a hermitage;

But without even having to tear it down, it remains a field."

The poem is saying that even without the hermitage being literally torn down, in reality it is not there in any permanent substantial sense; therefore, it is "empty."

We should be aware that "there is nothing to be attached to" and should not be emotionally apprehensive about coming events. If we do this, then, we will gradually become free of self-attachment, and our minds will become light and bright.

Only then are we assured of a joyful life.

3, The "Great Fool" and "Selflessness"

As stated previously, the original formless self has been variously called "benevolence" , "sincerity" , and "Buddha-nature."

The Chinese Zen master, Linchi(Rinzai), who is the founder of the Rinzai school, also quotes the ancients' words.

"The body with a form is not the true way of our enlightened being.

The formless self, as it exists without the body and mind, is our true figure."

Just being selfless will enable us to think of ourselves as being in the other person's situation. Just being a great fool will turn suffering into not-suffering. And being selfless and a great fool will allow us to act from a true, sincere heart.

The Zen master Linchi also declared,

"Stopping all egoistic discriminations,

and dwelling free of concerns is the best way to be.

A delusion that has already occurred should not delude one again.

Even if this is possible, it would take more than ten years of your pilgrimage practice to accomplish."

If we avoid all unnecessary thoughts, we will not be bothered by anything, and our joy will never leave us. It is not so difficult to live in this state of mind. Let us stop thinking about what bothers us and embrace the selflesssness of the one called the "great fool."

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is this mind?

Who is hearing these sounds?

Do not mistake any state for self-realization, But continue to ask yourself even more intensely, What is it that hears?

Who is hearing?

Your physical being doesn't hear,

Nor does the void, Then what does?

Strive to find out.

Put aside your rational intellect, Give up all techniques,

Just get rid of the notion of self.

-Bassui Tokusho-Rinzai Zen Master

1327-1387

#spirituality#consciousness#non duality#nonduality#meditation#bassui tokusho#zen meditation#zen#self realization

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zen Buddhism in Japan

Three Main Schools of Zen

There are three main traditional schools of Zen in Japan, each with its own background and specificities.

The Soto Sect

Soto is the largest of the sects. Historically practiced by the lower classes, artists, and poets, the Soto sect emphasizes the practice of sitting meditation known as zazen. Practitioners face a wall or a curtain during this meditation.

The Rinzai School

Traditionally practiced by the samurai caste, the Rinzai School include the presence of Koan, a kind of short and paradoxical sentence that cannot be solved intellectually. However, those are usually introduced only after good posture and concentration were achieved during the seated meditation.

The Obaku Sect

The smallest of the sects, the Obaku sect was formed by a small group made up of Buddhist masters from China and Japanese students at the Manpuku Temple (Manpuku-ji). To this day, those in the Obaku sect continue to chant sutras in the Chinese language.

[Source]

70 notes

·

View notes

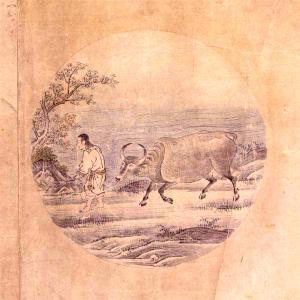

Text

In Zen’s history there have been a number of attempts at mapping the spiritual journey. The metaphor of taming an ox has been the most popular of these maps. The author of these “Ten Oxherding Pictures” is said to be a Zen master of the Sung Dynasty known as Kaku-an Shi-en (Kuo-an Shih-yuan) belonging to the Rinzai school. He is also the author of the poems and introductory words attached to the pictures.

"Here, our essential self is compared to an ox. We seek the ox, grasp it, tame it and finally the self which has always been seeking becomes completely one with the ox. But this also is forgotten so that we now simply carry on our ordinary lives. This is the process described by the Pictures." — taken from the Teisho (commentary) by KUBOTA Ji’un

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hymn of Zazen

Recently I stumbled a neat bit of Buddhist liturgy in the Rinzai Zen tradition called the Hakuin Zenji Zazen Go-Wasan (白隠禅師坐禅御和讃), or more simply the Zazen Wasan (坐禅和讃). This means “The Hymn of Zazen [of Zen Master Hakuin]”. In English it is sometimes called the “Song of Zazen”.1

Rinzai Zen is a somewhat unusual sect in Japanese Buddhism because although it was founded in the 12th century by…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Inganno - Delusion - Maestro Zen Rinzai

🌸Inganno🌸“Non farti ingannare da nessuno,questo è tutto ciò che insegno.Se vuoi farne uso,allora usalo subitosenza dubbi né ritardi.”Maestro Zen Rinzai🌸🌿🌸#pensierieparole🌸Delusion“Don’t be deluded by anyone, this is all I teach.If you want to make use of it, then use it right now without doubt or delay.”Zen Master Rinzai

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Academic Excursion- Zen meditation

Academic Excursion

In reference to my blog post for this day which I mentioned all about the zen gardens and what we went through during our time in meditation I thought it would only be fair to talk more about because I was blown away by it. The sheer willpower one had to have to go and make sure the rock formations that they had in these dry gardens were perfectly lined and well maintained all the time is nothing short of inspiring. How they perfectly selected rocks that had the perfect shape to be able to be attributed to something real like a boat or a mountain and placing it in this one large landscape of the zen garden is so perfect. Nothing is done by accident and everything has a precise and known reason for being that way that it is. As soon as I saw the sign saying they offered meditations on the weekends for one hour my mind was made up, I had to go. Meditation and calming one’s mind has always been a big part in my family because my mom is a big fan of yoga and during my highschool cross country career she taught me what it meant to slow down and visualize yourself overcoming an obstacle so I felt drawn to this meditation for that reason among others

Academic reflection

The article that I picked out and will be citing in this reflection is titled “Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan” by William M Bodiford. Even though the article mainly focuses on Soto Zen and we went to a Rinzai temple it may still be useful in providing us the origins of Zen meditation in Japan and seeing what may have caused the differences from school to school. Bodiford claims that although many Japanese scholars point to the existence of Japanese zen as something that came on its own and developed within Japan it is almost impossible to talk about Japanese zen separate from the many aspects of Chinese meditation that came and influenced the Japanese. One of these aspects is the idea of silent illumination or mozhao in chinese which has heavily influenced the practice of shikantaza or “just sitting” in zen. It aims to clear your mind and allow you to be aware of the present moment. All schools adopt the idea of just sitting in a broad sense, like we did at the Daisen-in but some may introduce a different aspect in this mediation by asking questions that invoke you to think paradoxically, these are called koans. This is seen from the Rinzai school which is the one that we went to but as it was just a basic meditation session I am sure they did not feel the need to ask a bunch of foreigners questions that we wouldn't understand in Japanese. The sect of buddhism that this article talks about is Soto Zen which is different from the one that the Daisen-in uses which is from the Rinzai school. This difference is actually pretty important as Soto zen focuses more on religious worship and funeral services then maybe more traditional zen practices like meditation or as the article called it Zazen. Going to the Daisen-in you can see this difference first hand as the temple did not seem very open to have people worship and practice there as there was no statue or anything like that to sit down and pray to the only thing they had advertisements for was their meditations. From then on the article also goes on to talk about how mediation in Japan has always been associated with the mountains. They called it pure practice or “jogyo” and they called meditation (zen gyo) and the meditation masters who trained here were called zenji or meditation masters. The mountain aesthetic was present in the Daisen-in as in their main room that was supposed to represent only the bare ocean; the only thing that stood out from this plain landscape were two tall mountains in the middle of the ocean. Reading the article after going to the mediation cleared up a lot of the holes or things that I didn't quite understand revolving zen meditation and put it in perspective that made me appreciate the fact that I went through something that has its roots well planted into ancient history.

Source: Bodiford, William M. Soto Zen in medieval Japan / William M. Bodiford University of Hawaii Press Honolulu 1993

1 note

·

View note

Text

Troga sword of truth

Remix of Go Rin No Sho, Heiho Kaden Sho, Fudochi Shinmo Roku & Taia Ki Tekst dotyczy buddyjskich korzeni kenjutsu, a jego wartość polega na bezpośrednim odwołaniu się do klasyków myśli samurajskiej – MUSASHI MIYAMOTY, TAKUANA SOHO, MUNENORI YAGYUīy Miyamoto Mushashi, Yagyu Munenori & Takuan Soho Mam przyjemność przedstawić ciekawy tekst opracowany przez Autora posługującego się pseudonimem : VIN AL KEN. KEN ZEN ICHI / MIECZ I ZEN TO JEDNOŚĆ – na podstawie klasyków myśli samurajskiej Takuan's book (one of most important work of " Kenjutsu -Ryu" Library) He has also been credited with the invention of the yellow pickled Daikon radish that carries the same name, "Takuan." His influence still permeates the work of many present-day exponents of Zen Buddhism and martial arts. His collected writings total 6 volumes and over 100 published poems, including his best known treatise, The Unfettered Mind. Known for his ascerbic wit and integrity of character, Takuan exerted himself to bring the spirit of Zen Buddhism to many and diverse aspects of Japanese culture, such as Japanese swordsmanship, gardening, Sumi-e, Shodo, and Tchado. With regards to his character, Takuan remained largely unaffected by his popularity and famed reputation. Yagyū Munenori (Daimyo and kenjutsu master, head of Yagyū Shinkage-ryū style of swordsmanship) - Takuan's writings to kenjutsu master, Lord Yagyū Munenori, are commonly studied by contemporary martial artists. It is stated that Takuan advised and befriended many persons, from all social strata of life. His tomb is located in the Shinagawa area of Tokyo at Oyama Cemetery of Tokaiji Temple. At the moment before his death, Takuan painted the Chinese character 夢 ("dream"), laid down his brush and died. Takuan Sōhō died in Edo (present-day Tokyo) in December of 1645. Later, Takuan was invited by Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604–51) to become the first abbot of Tokai-ji Temple in Edo, which was constructed especially for the Tokugawa family. By 1632, there was a general amnesty after the death of Hidetada Tokugawa and Takuan’s period of banishment came at an end. In 1629, Takuan was banished to northern Japan by the Shogunate of Hidetada Tokugawa due to his protest of political interference in Buddhist temple matters pertaining to ecclesiastical appointments. Throughout his journeys, Takuan raised and collected funds for the renovation of Daitoku-ji Temple and other Zen temples. Unfortunately, Takuan's appointment was shortened as he left for a prolonged period of traveling. By the age of 14 in 1587, Takuan started studying the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism under the tutelage of his sensei Shun-oku Soen.īy age 36 in 1608, Takuan was made abbot of the Daitoku-ji Temple in Kyoto, Japan. At the age of 8 in 1581 young Takuan began his religious studies and 2 years later he entered a Buddhist monastery. Takuan Sōhō was born into a family of farmers in the town of Izushi, located in what was at that time called Tajima province (present-day Hyōgo Prefecture). Takuan Sōhō (沢庵 宗彭, 1573–1645) was a major figure in the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism. To umysł przenikający przez całe ciało i jaźń." "Czysty umysł nie jest skoncentrowany w żadnym miejscu, nie pochłania go zadna myśl. Takuan Soho - Buddhist Monk, Intellectual and Spiritual Mentor of MUNENORI YAGYU

1 note

·

View note

Text

Master Rinzai reveals the true nature of a shit-stick

With Zen, it is easy to take on many 'views of Zen' and think to yourself, "This is Zen" up to the point when that view reveals itself to 'yet be another delusion', then you are off to the next view of Zen! Hahaha...

One day Zen Master Rinzai (Ch. Lin-chi) said, “There is a true man of no rank in the mass of naked flesh , who goes in and out from your facial features. Those who have not yet testified, look, look!”

A monk came forward and said, “Who is this true man of no rank?”

Master Rinzai came down from his seat, grabbed the monk by the throat and said, “Speak! Speak!”

The monk hesitated.

Master Rinzai let go and said, “What a worthless shit-stick this true man of no rank is!”

Having had a stroke a while back, I was robbed of my speech for a while. It was amazing for me to realize how much of my own Identity, the view of myself, I carry with my ability to speak as well as to hear myself speak. The old saying "Like to hear oneself talk" speaks to the self-absorbed and self-important in one's speech, without having much or any regard for those to whom one is talking.

I was also robbed of using my right hand as well, so my writing and typing became greatly diminished - thus my ability to become self-indulgent, in pleasing and entertaining myself was also taken.

Though others may panic at such a plight, I was actually fascinated by this. For how easy it was to flow into ones own speech and writings in creating this 'View of oneself' that can be eradicated in a moment! HA!

You see, this mortal body, this shit-stick, is just liken to an instrument that is played by ones' very essence (spirit/soul). When one cast the body aside, one sees how worthless it is without the essence that animates it!

As for that essence inside each of us? What is that, and where was it before this body was born, and where does it go after this body is cast aside? That is the mystery for you to discover and reveal to yourself.

This is The path of Zen. All the Zen masters of old speak to this mystery, all of them implore you to give up your views, your ranks, your positions and, your own thoughts - to 'Take the backwards Step' and see the instrument upon you call 'yourself' and to if for 10th of a second to see the mystery of your own essence for yourself thus lighting the lamp (enlightenment).

0 notes

Text

Morning Meditaton — To become a great vessel.

Morning Meditaton — ‘To become a great vessel.

https://wp.me/pFy3u-8on

‘To become a great vessel, it is important not to put into it any errors of others.’

Zen Master Rinzai

Evening sky over Totnes.

On our Twitter account, Buddhism Now @Buddhism_Now, most mornings we post a ‘morning meditation’ like the one above.

On the net, of course, it’s morning, afternoon, evening, or nighttime 😀 somewhere.

Click here to read more Morning Meditation posts.

Click here for…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Master of the Shouts - Osho

The Master of the Shouts – Osho

A little note about Rinzai, master of the irrational.

Rinzai, also known as Lin-Chi, was born in the early ninth century and was to become the founder of one of the most significant schools of Zen.

Brilliant as a child, later, when Rinzai became a priest, he studied the sutras and scriptures. Realizing the answer did not lie within them, he went on pilgrimage, visiting Obaku and Daigu, two great…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

*No Language Is Able To Translate An Inner Experience- Osho* One of the most difficult things is to change an experience into explanation, and from one language to another it becomes almost an impossible task. But Bodhidharma managed it, and Rinzai also managed. This transmission of the lamp has to be understood deeply; only then will you be able to understand the sutras that follow. No language is able to translate an inner experience, a subjective experience, for the simple reason that language is created for the objective world, about things, about people. No language has been created about the innermost center of your being, for the simple reason that when two men of the same experience meet there is no need to say anything. Their very presence, their very silence, the depth of their eyes and the grace of their gestures is enough. There are only three possible situations. Either two enlightened beings meet, then language is not needed; they both meet beyond language, their meeting is the meeting of no-mind. The second situation is if two unenlightened people meet: they will talk much, they will use great words, much philosophy, much metaphysics, but it will all be meaningless. It will not be supported by their experience. They are just parrots, repeating other people's words. Obviously they cannot create the language for the buddhas. They have no idea what it is in the innermost core of your being. The third possibility is a meeting between an enlightened person and an unenlightened person. The enlightened person knows, the unenlightened person does not know. But although the enlightened person knows, it is not enough to convey it. To know is one thing; to transfer it into language is another thing. - Osho, "Rinzai Master of the Irrational", Ch# 1. #nature #buddha #love #music #universe #osho #beauty #enlightenment #rumi #bliss #meditation #death #awareness #india #divine #peace #intuition #intimacy #healing #jiddukrishnamurti #zen #nirvana #tantra #consciousness #yoga #multipleorgasms #freedom #dance #celebration #awakening # https://www.instagram.com/p/CdvxE0LP-Qe/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#nature#buddha#love#music#universe#osho#beauty#enlightenment#rumi#bliss#meditation#death#awareness#india#divine#peace#intuition#intimacy#healing#jiddukrishnamurti#zen#nirvana#tantra#consciousness#yoga#multipleorgasms#freedom#dance#celebration#awakening

0 notes

Quote

There is no place of rest in the Three Worlds; it is like a house on fire.

This is not a place for you to stay long.

The Zen Teaching of Rinzai, trans. Irmgard Schloegl

#post - the practice of pointing#quotes - rinzai gigen zenji#zen buddhism#linji yixuan#rinzai zen#obey your master - rinzai gigen zenji

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"So, the Taoist trick is simply, 'Live now and there will be no problems.' That is the meaning of the Zen saying, 'When you are hungry, eat. When you are tired, sleep. When you walk, walk. When you sit, sit.' Rinzai, the great Tung dynasty master, said, 'In the practice of Buddhism, there is no place for using effort. Sleep when you're tired, move your bowels, eat when you're hungry---that's all."

- Alan Watts

245 notes

·

View notes