#absurdism offers freedom from christianity

Text

What Is Crooked Cannot Be Straightened

5/29/23

When I started going to therapy for religious trauma, my therapist directed me to Abraham Piper, a rather famous exvangelical and son of John Piper, a famous evangelical fundamentalist. Abraham Piper's TikTok account was interesting, philosophical, and entertaining all at the same time, and many of his ideas hit home with me, as someone who was floundering with the idea of religious trauma, despite it having been nearly 8 years after my Exit.

One of the tags he used was #abusurdism which I'd never heard of before, and being a curious type of person, I googled it.

"What is absurdism?"

Of course, as you might expect, I found dozens of articles and reddit threads discussing Albert Camus, existentialism, and meaninglessness.

I was hooked.

Meaninglessness had been an appealing concept to me since the first time I read Ecclesiastes, the only book of the bible I ever really liked.

Even now, if you asked me what my favorite book of the bible was, I'd still say Ecclesiastes. When I was young, my reason was that it was beautiful poetry written by a clearly intelligent person who understood the futility of life, and which ended by directing you to trust god.

Now my reason is because Ecclesiastes breaks christianity. It's like a computer virus. As soon as you run ecclesiastes.exe, blue screen.

In Ecclesiastes, the writer concludes that everything is meaningless, therefore, your best bet is to fear god and follow his commandments (cough *philosophical suicide* cough). The ending offers an easy "skip" button.

"Fear god!" christian you might think. "Great, that's all I need to know. I was gonna do that anyway."

This answer is good enough until you read that verse in Romans about how you're supposed to study the scriptures. And then you do study them.

As soon as you really begin to look deeply into Ecclesiastes, one key thing leaps out: if everything is meaningless... so is following god and his commandments. That solution the Teacher offers? Just as meaningless as any other solution.

All of christianity centers around one foundational element: the meaning of everything is god.

But if there is no meaning to everything, if god is not the meaning after all... what does that mean for the entirety of the christian religion?

If you take Ecclesiastes literally, then making the choice to "obey god" is just as meaningless as making a different choice. Even if you choose to "follow god," the method for doing so is meaningless. You could choose to follow the old testament god or the new testament god, you could follow Thor or Allah, you could rename the universe "god" and call it a day—and you get to make up your own "rules" about what following god looks like, and at least philosophically speaking, you're good to go.

Most christians would argue that therefore you must follow the christian scripture, because obviously the bible doesn't contradict itself, because it says so. heh

But this doesn't work. Literally no one follows the scriptures literally. Not even literalists. Because it's impossible. Because the bible doesn't agree with itself about anything.

And even if you find ways to look past all the other contradictions, Ecclesiastes undermines everything else. It puts questions where They don't want questions. It adds flexibility where They don't want flexibility. It adds meaninglessness where They want meaning.

And They can't get rid of Ecclesiastes. Because if They do that, then they're picking and choosing what scripture to follow. And if you can cut and paste Ecclesiastes, then it follows you can cut and paste the rest of the bible, in which case you might as well just throw the whole thing in the trash and start over.

As far as I can tell, the "best" argument against my interpretation of Ecclesiastes is "no, you're misinterpreting it" which... isn't an argument. The very fact that Ecclesiastes demands interpretation in order to "fit" with the rest of christianity, means that I can interpret it however the hell I want.

And I choose to interpret it as an exploration of the meaninglessness of everything that ultimately undermines the whole of christianity.

When faced with ultimate meaninglessness, some people choose to avail themselves of the pleasures of life. Some people choose to work. Some people choose to find meaning in the mundane. Some people create their own meaning. Some people (like Solomon) choose to follow god and obey the king. And some people simply... accept meaninglessness.

And this is the heart of absurdism: choosing to accept meaninglessness as a fact of life, rather than fighting against it, trying to fix it, or trying to solve it.

Everything is meaningless. Utterly meaningless.

Including Ecclesiastes.

Everything is meaningless and that’s okay. Not only is it okay, it's good. Because acceptance often brings peace, freedom, and joy where there was only cognitive dissonance before.

#ecclesiastes#bible#literalist#atheist#atheism#absurdism#absurdist#ex christian#exvangelical#exchristian#philosophy#christian philosophy#the bible is stupid#solomon#everything is meaningless#albert camus#absurdism offers freedom from christianity#cults#cult ideology#the christian cult

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max’s interview with Film-Rezensionen (part 1), they talk about: “Zwei zu Eins” (“2 to 1”), money, life before the internet and social media ❤️

Q: How did you get involved in this film project?

Max: Natja Brunckhorst had specifically asked me if I would like to work with her. Of course, I knew her as an actress and appreciated her work in “Christiane F. - We children from Bahnhof Zoo”. Being so good at that age shows just how much she offers to a film. And I respect her for that. But also for the script she wrote. So I was involved very early on. It took a while for it to really get started, but for me it was clear from the beginning that I wanted to work with her.

Of course, I was also attracted by the topic. This is not only an “East-theme”topic, but a universal one: about money or the philosophy of money. How we chase after money and what we make of it is already absurd. The film’s tagline: “Money is printed freedom” fits very well and also makes you think. Especially at a time when people with money can accumulate even more money without having to do anything, while others have nothing at all. The gap between the rich and the poor is getting further apart, and you realise that this simply cannot work in the long run. You must not make yourself dependent on money and define yourself by it. It is of course difficult if you have existential crisis and fears. But “Zwei zu Eins”also talks about solidarity and other values and how you can be rich without money. These are values that you easily lose if you focus too much on money.

Q: Is money a topic you think about at all?

Max: Sure, that’s always the case. I’d like to have so much that I would have no fears and needs and can afford stuff. But if you have so much and don't know what to do with it, then I think it can be detrimental to you. Especially in human relationships, you are often defined by how much you own. This makes it more difficult to tell who is your friend and who is after your status symbols. I think people who have a lot of money, also afraid of losing it. Once you have become accustomed to a certain standard of living, you quickly become dependent to it. So you really need a healthy relationship with money, it's certainly not wrong to work for it. But if it simply falls into you, then it’s not so healthy. These are all subjects featured in “Zwei zu Eins”, which I think is great. I like this attitude towards life, the simplicity of the period before the internet and smartphones. Back then, if you were bored, you would look for something to do or have a conversation with others. It is very interesting to remember that not too long ago, we worked in a very different way. That we weren't distracted all the time, our memory wasn’t stuffed with things we don't need at all.

Q: Is that something you miss?

Max: Yes, maybe so. I'm not that so savvy when it comes to the internet and social media. In fact, I am rather critical of it, because it is demonstrably not healthy for your mental health if you constantly compare yourself to others or upload pictures of yourself in the hope that someone will like them. I also miss the directness that you look at yourself, to search inside yourself, when you can't think of anything, instead of shyly staring at your mobile phone. Maybe this way, you can come up with new ideas, and not just consume.

#max riemelt#max german interview#film-rezensionen de#his view on social media is not new and not a surprise 😭#zwei zu eins#i love this interview worth getting google translate

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi,I want to start this by saying that I have some problems with some satanists on tiktok,I am a Luciferian Satanist myself and I dislike those people,I believe that they are fake Satanists,I want to call them out on this but before doing so I wanted to know what would other Satanists think,to make sure that I am not the only one who believes that they are posers(poser may not be the appropriate word to describe them but I dont know what else I should call them). These people claim to be theistic Satanists and believe in Baphomet,I don't know if there are other Satanists who believe in Baphomet but I think it's pretty absurd to actually believe in him,in my eyes he is just a symbol of duality that Satanists use.

This makes me think that they don't even do research in what Theistic Satanists and Luciferian Satanists believe in,from things like claiming to be Theistic Satanists but will also believe in Lucifer and claim that diabolism doesn't belong into satanism.

It's also kind of amusing how they will tell others that they actually believe in satan but then will use the 11 satanic rules and 7 satanic sins from the Satanic Bible to try and make Satanism look good,I think that this is wrong for more reasons,using paragraphs from the Satanic Bible while being a Theistic Satanists is stupid because every type of satanism holds different types of beliefs and morals and trying to make Satanism look good for non Satanists is just stupid because we don't need to explain ourselves and our beliefs to anyone and we don't need their acceptance or anything.

These "Satanists" see Satan/Lucifer how Christians see their god,claiming that you hold beliefs in Lucifer and that he is an loving god who offers you comfort is just stupid,Lucifer offers enlightenment,not comfort,and saying stuff like "Satanism is not evil and dark" is stupid,especially if you are a Luciferian one,evil and darkness are parts of our belief but they are just not wrong and them saying that you must respect everyone's beliefs but only if they respect yours,I believe that it's pretty stupid to respect Christianity,Islam and Judaism as a Satanist,Satanism is about freedom,enlightenment,rebellion and to always question the higher authority,its supposed to be hateful towards religions who are based on faith and have a history of multiple genocides and oppressing women's.

Before ending my rant I want to say that no,I will not harass those people for being "posers",I will most likely create an account in which I will call them out and post about what Luciferian Satanism is.

#satanism#luciferism#satanic#hail satan#satan#blasphemy#ave satanas#satanist#theistic luciferianism#theistic satanism

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

hewwo!

What the mweaning of life? Should we comwit cwimes if we think they're fair? I'm just a silly cat giwl asking silly qwestions UwU

The quest for the meaning of life has been an eternal pursuit that has captivated human minds throughout the ages. Philosophers, theologians, scientists, and ordinary individuals alike have grappled with this enigmatic question, seeking answers to the fundamental purpose of existence. The multifaceted nature of this inquiry has led to a plethora of perspectives, beliefs, and interpretations, making it a subject of immense interest and debate. In this essay, we shall embark on an exhaustive journey through history, philosophy, religion, and science, as we explore the intricacies of this age-old question: "What is the meaning of life?"

The Philosophical Quest for Meaning

Philosophers have long been at the forefront of exploring the meaning of life. Ancient thinkers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle sought to unveil the essence of human existence and its place in the cosmos. Aristotle, for instance, argued that the ultimate purpose of life was eudaimonia, or "flourishing," achieved through the cultivation of virtues and the pursuit of knowledge.

Existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus approached the question from a different angle, emphasizing individual responsibility and the creation of personal meaning in an otherwise indifferent universe. Their works delved into the absurdity of life and the need for individuals to embrace their freedom and define their own existence.

Furthermore, in the contemporary era, philosophers like Viktor Frankl proposed that the search for meaning is at the core of human nature. Drawing from his experiences as a Holocaust survivor, Frankl developed logotherapy, which asserts that finding purpose even in the most challenging circumstances is the key to psychological well-being.

The Religious Perspectives on Life's Meaning

Religion has played an integral role in shaping the understanding of life's purpose for billions of people worldwide. Different religious traditions offer diverse perspectives on the meaning of life, each rooted in sacred texts, doctrines, and rituals.

In Christianity, the belief that life's meaning lies in devotion to God, following the teachings of Jesus Christ, and achieving salvation through faith and good deeds prevails. Islam, too, emphasizes submission to Allah's will, following the guidance of the Quran, and performing righteous actions as the path to eternal reward.

Buddhism, on the other hand, seeks the cessation of suffering through the pursuit of enlightenment and detachment from material desires. Hinduism teaches that the purpose of life is to attain moksha, liberation from the cycle of birth and death, achieved through karma, dharma, and spiritual realization.

The Meaning of Life in Scientific Discourse

Science, with its empirical approach and rigorous methodology, has also contributed to the discussion of life's meaning. While scientific inquiry primarily focuses on understanding the natural world, it has indirectly shed light on human existence.

Biological sciences explore the origins of life, the complexities of evolution, and the genetic underpinnings of human behavior. Psychology delves into human consciousness, emotions, and cognition, attempting to comprehend what drives individuals to seek meaning and purpose.

Astrophysics and cosmology contemplate the grandeur of the universe, leading some to speculate about the potential existence of extraterrestrial life and its implications on the meaning of our own existence.

Synthesizing Perspectives: Towards a Comprehensive Understanding

As we navigate through the myriad of philosophical, religious, and scientific perspectives on the meaning of life, it becomes evident that no single answer can satisfy all of humanity. Each viewpoint offers unique insights into the complexity of this profound question, and a synthesis of these perspectives might lead us closer to a comprehensive understanding.

The human condition is one of diversity, and with it comes the richness of human experiences, beliefs, and cultures. Recognizing the validity of different worldviews and appreciating the wisdom they bring to life's meaning is an essential step towards fostering empathy, understanding, and harmony in a diverse world.

Conclusion

The search for the meaning of life is a timeless endeavor that transcends cultural, philosophical, and scientific boundaries. From ancient philosophies to contemporary scientific discoveries, every aspect of human knowledge contributes to our quest for purpose and understanding.

Perhaps the true meaning of life lies not in finding a definitive answer, but in the pursuit itself—an ongoing journey of introspection, growth, and enlightenment. Embracing the diversity of perspectives and recognizing the interconnectedness of all life may be the key to unlocking the deeper mysteries of existence.

In the end, we must remember that the pursuit of meaning is an individual and collective endeavor, shaped by our unique perspectives and experiences. As we continue on this eternal quest, let us embrace the beauty of life, the wonder of existence, and the potential to create our own meaning in a vast and mysterious universe.

Also you can do crimes for fun and no one can stop you

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

No, Thank You

TW: Religious trauma

So, a friend irl of mine is, once again (this happens all the time and I hate it), dealing with harassment from “Christians” and I feel feelings about it. (Btw, WWJD? Maybe not be a huge dick. Seemed like a chill guy to me when *I* read the gospels.)

There’s this funny thing that’s been happening to me for as long as I can remember. Since I was too young to read, I have been given “literature” explaining to me god’s great plan by Christians of all stripes and denominations. First, it started with my mother’s family. I can still remember the red script of the title against the oddly grained yellow book cover that said “My Book of Bible Stories” or something to that effect. It’s the McDonald’s color scheme that sticks with me, not the title, clearly. I would receive countless more books like these from that side of the family. Even though my mother, herself, had been forcibly ejected from that particular sect of Christianity, and had chosen not to return, still they sent me books, and letters, and propaganda, trying to, supposedly, save my soul.

The attempted indoctrination didn’t stop there. My parents put me in Catholic school in kindergarten, where I stayed until the school insisted that I be baptized and assigned godparents. My parents were okay with me exploring any religion I wanted, but my mother’s experience had taught her that I should be of the age of reason before I made any decisions about my religion. My mother was baptized at twelve, and she believed that was a mistake. She thought that she had been too young to know what she really believed and Young Sharon had made promises that Adult Sharon couldn’t keep. But she never prevented me from exploring such things. I went to Sunday School with a friend in third grade, went to the Wednesday afternoon bible study at the church next to the elementary school. I went to Catholic church with my best friend in middle school any time I stayed over on a Saturday night. I even tried again in high school, with some very odd evangelicals that spoke in tongues and really weirded me the fuck out.

Somehow, my little circle of girlfriends going through our obligatory weird girl Wiccan high school phase seemed less weird than the girl in the church sitting on the floor, two inches from the wall, laughing at it. At least, on some level, we knew the midsummer celebration was more about the slumber party than anything else. Jaycelyn, please stop putting your toe up my nose.

As I got older, I explored other faiths, other cultures. I dipped into Buddhism, read the Tao Te Ching to touch base with Taoism, was exposed in college to Shintoism, Hinduism, Islam. Nothing touched me. Until I read atheist writers, who told me that it was okay to not connect. That it was okay that I couldn’t believe what was being offered. That there was nothing after death, and that I could cope with that if I wanted to.

When I was young, my search through Christianity was an attempt to belong somewhere. And in this society, this culture, the easiest way to belong is to go to church. But I couldn’t belong somewhere when I was simply going through the motions, pretending to believe. After my father died, my search became more desperate, more about a search for meaning, a need to mitigate my loss.

After many years, I have come to absurdism. There is no meaning, and it is absurd to search for it. Let’s be absurd. Who cares? It’s not like anything matters so we might as well have some fun with this. For some this is bleak, empty and cold. For me it is freedom, joy and dread in equal parts. But I no longer cringe away from the parts of life that hurt. Because life is pain. And joy, and fear, and love, and, and, and…

My point? At no point did anything that anyone else did or didn’t do convince me to convert to any religion. The books, the pamphlets, the in-person visits, or the constant harassment and bullying all throughout my formative years, none of it did anything but show me what was on offer. I politely declined, because what was on offer looked sad and empty to me. A life spent longing for the next. Thank you, but no thank you. I’m grateful enough for what I have.

To be fair, the constant harassment and bullying by Christians has only made it clear to me that most of them don’t really know what their religion is even about, so I can’t learn anything about the universe or meaning from them. If you want to know why I’m not a Christian, ask yourself if you’ve ever done anything that might be considered bullying or harassment to try to shame someone into it. If that’s how you believe your god wants you to act, I want nothing to do with you or your god.

I am an absurdist agnostic atheist. If you want to know what that means, I’m happy to tell you. But if you want to offer me something else, stop. I know what you have. I do not want it. If you have it, and it brings you joy, I am genuinely happy for you and I would never want to take that away from you. Stop trying to give it to me. I. DO. NOT. WANT. IT.

I have what I need.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Life of Stories - Soulbonding and My Story

It’s the late 90’s. A tiny child sits in the grip of wonder on the carpet two feet from the old, analog television screen. The volume is turned way down on a Saturday morning, so as not to wake the parents. And Digimon: Adventure is playing.

That kid was me.

I spent the next several days telling anyone and everyone I knew about the trials and bravery of my favorite new friends on the TV. Taichi and his Digi-pals.

Every Saturday morning I tuned in with wrapped attention to check in on my friends. Because that is what they were. I could not explain it at the time, and looking back I see that I did not understand just how powerful my love for them was, but over the years I began to notice the disparity between my experience and that of others. The glazed looks I received when I tried to communicate just how much the “stories” around me meant to my heart and spirit.

As I grew, so too did my well of worlds. When it was not Digimon, it turned to Batman and the DC Animated Universe. Over the years, as things became harder and harder for me in an unsafe household, I would reach out to those stories for safety and comfort. In the dead of night, listening to shouts, I would silently pray for Batman to come in and save me. I would think about Static, from Static Shock, and his bravery. I would long for the Justice League to show me hope.

I grew up in a conservative Protestant Christian household, and I was quickly taught from the moment I could understand stories that they were not real. It seemed a strange double-standard to me, as we read of Jesus and his amazing feats, recorded centuries ago by the hands of men but somehow “different” than the other stories I consumed, which also taught me and affected me just as emotionally.

It would not be until adulthood that I could finally articulate this incongruity I felt, much less possess the bravery and personal freedom to think about it on my own terms. To set aside the pre-packaged “truth” I had been fed growing up in order to find my own fresh fruits of wisdom and meaning.

Stories. Stories are what sustain humanity. All we have are stories. Even the perceptions we store in our brains are only that. Perceptions. Stories. We can never truly know what an orange is, or who a person is. We only can know our perception of them, and the story of them that lives on within us.

And, sometimes, those stories speak to us in the most fantastic and magical of ways.

Fast forward to 2021.

I am an adult. A practicing witch and pagan. An artist and writer. I am functional and thriving. And I have an unusual family.

Some of the most important people in my life do not exist on the physical plane of this Earth quite the same as other friends of mine. They exist in the subtle realms of Dream and thought and wonder. Over time I have come to find many names for them. Spirits, guides, and “soulbonds”.

I began my foray into the community of “soulbonding” when I began to sense, or rather, acknowledge the living quality of some of the “characters” I was writing about. One character in particular, a being who introduced himself to me in a dream, had me particularly flummoxed. I called him Asura, and from the moment he entered my life through that dream, my entire world changed. It was akin to stepping onto a roller coaster car while it was still moving—except this roller coaster had no track and no limits. His entire presence permeated my life, my thoughts, my daydreams. I wrote about him, and it was my writing about him that led me to thoughts, questions, and explorations I would have never dared otherwise. By finding him, he led me to find myself, and for that I shall be forever grateful.

At some point, I, and even my closest friends, became aware of a “spookiness” about my dogged pursuit of this mysterious character. I started to know things about him and his world, and make connections in his story, that seemed to come out of nowhere but which all cohered together perfectly. Without a fault, I would learn tidbits about him that would suddenly fit with another thing I learned later, though I never had to strain to achieve such things. It was not so much that I was “creating” the story so much as “recording” it. There were elements of his story that overlapped with our world’s history and it was spooky as all get out when I learned about historical facts through his story and later found them to also be reflected in my own world, which has a similar timeline to his. A sort of “sibling world” to his.

We also noticed the tremendous power of my emotional connection to him and his friends. My boyfriend at the time even became jealous of Asura, though I assured him that was absurd. “Asura is just a story,” I would say. And my boyfriend thought the same yet he, and others, seemed unable to ignore the fact that there seemed to be something weird going on.

And, one day, with horror, I realized I was in love with Asura—fortunately, by that time I had since broken up with my boyfriend—but the idea terrified me. Unsurprisingly, this sent a conservative Christian “good kid” such as myself down into a spiral of questions and disbelief.

I felt the imposter syndrome. I thought, “I must be insane.” Yet, no one, myself included, could deny the reality of this connection I felt.

Over time, Asura and his friends began to speak to me. They guided me and provided loving support to me. I, at the time, figured I was either crazy or eccentric.

“Maybe this is a writer thing,” I thought.

And it was that thought that led me to soulbonding. I learned of other writers who also had their “characters” come alive to them. Alice Walker, author of the famed American work, The Color Purple, allegedly purported that she had received her story straight from the characters’ mouths one afternoon, during which she sat down to tea with them and learned their tale. And that is when I found a forum site called “The Living Library” (now defunct), and learned the term “soulbonding”.

In that community I found others who echoed my story in various ways. Deep personal connections to entities from other worlds, many of whom they found depicted in the flourishing ecosystem of thought and imagination, stories, that surrounds the human race. Others, discovered their unconventional friends via dreams, visions, or odd circumstances just like myself. One person I met had actually found one such friend first, in this instance a version of Edward Elric from “Full Metal Alchemist”, before learning years later—with a start I imagine—that Edward actually had an entire manga and anime about him.

I say “version” because another amazing phenomenon I discovered was the occurrence of many instantiations of people, characters, from infinite worlds, all with slight variances from one another. That is when I was introduced to the idea of Multiverse Theory and Many Worlds Theory.

As my personal investigations led me down various spiritual rabbit holes, and eventually led me to spirit-working and witchcraft, I found more and more ideas that seemed to jive with my experience.

I discovered what are colloquially called “pop pantheons” in occult circles. Pantheons of spirits and deities who connect to pop culture figures in human society—and even figures from “fiction”. And there is a whole, thriving community of people who lead successful, fulfilled, and meaningful spiritual lives working with these entities. I learned that reality and “truth” are not objective like I had been taught so long ago. And I finally understood MY truth—all we have are myths and stories. Experience is subjective and the only measure of meaning and truth we have is in the effects we see in our own lives.

With tremendous wonder and happiness, and even love, I have seen the effects my unconventional friends and family have wrought in my life. Asura is my familiar spirit now, and I have a whole host of other beings whom I love. Some come from “personal gnosis”, or unique experience, such as Asura. Others are beings who have come to me from the vast world of collective Dreaming that permeates our world, evident in media sources, in the form of stories.

I still have moments of doubt. I sometimes wonder, “Gee-golly-whiz, am I NUTS?” But then I remember that my truth exists only in my own experience. My ethereal family brings me happiness, growth, and meaning. And there really is no difference between my relationship with them and the relationship I had with Jesus so long ago. Every experience is real to me, and brings with it change and good. And that is what matters.

In this blog I intend to share my experience, in hopes that it can offer a beacon to others in similar situations. Every person’s experience is unique, though I hope mine can at least offer some hope, understanding, and love to another.

Cheers.

And happy story-telling.

- Cosmic

#soulbond#soulbonding#spirituality#spirits#spirit-work#spirit#stories#writer#writing#poppantheon#pop pantheons#occult spirituality#witch#spiritworker#spirit work#my story#my post#SILVERfamily

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historical Holiday Traditions We Really Need To Bring Back

Here comes Santa Claus, and also a bunch of annual holiday Things we do to ensure he commits a truly boggling act of breaking and entering and leaves goods underneath the large plant in the living room.

Because I’ve always got a hankerin’ for the days of yore, here are some historical holiday traditions we really need to bring back:

1. Everything that happened on Saturnalia

Saturnalia was the ancient Roman winter festival held on December 25th--which is why we celebrate Christmas on that day and not on the day historians speculate Jesus was actually born, which was probably in the spring.

Saturnalia was bonkers. As the name suggests, it celebrated the god Saturn, who represented wealth and liberty and generally having a great time.

Above: Their party is way cooler than yours could ever hope to be.

During Saturnalia, masters would serve their slaves, because it was the one day during the year when everybody agreed that freedom for all is great, actually, let’s just do that. Everyone wore a coned hat called the pilleus to denote that they were all bros and equal, and also to disguise the fact that they hadn’t brushed their hair after partying hard all week, probably.

Gambling was allowed on Saturnalia, so all of Rome basically turned into ancient Vegas, complete with Caesar’s Palace, except with the actual Caesar and his palace because he was, you know. Alive.

The most famous part (besides getting drunk off your rocker) was gift-giving--usually gag gifts. Historians have records of people giving each other some truly impressive white elephant gifts for Saturnalia, including: a parrot, balls, toothpicks, a pig, one single sausage, spoons, and deliberately awful books of poetry.

Above: Me, except all the time.

Partygoers also crowned a King of Saturnalia, which was a predecessor to the King of Fools popular in medieval festivals. The king was basically the head idiot who delivered absurd commands to everyone there, like, “Sing naked!” or “run around screaming for an hour,” or “slap your butt cheeks real hard in front of your crush; DO IT, Brutus.”

Oh, wait. Everyone was already doing all that. Hell yes.

(Quick clarification: early celebrations of Saturnalia did feature human sacrifice, so let’s just leave that bit out and instead wear the pointy hats and sing naked, okay? Io Saturnalia, everybody.)

2. Leaving out treats for Sleipnir in the hopes of avoiding Odin’s complete disregard for your property

The whole “leave out cookies and milk for Santa” thing comes from a much older tradition of trying to appease old guys with white beards. In Norse mythology, Odin, who was sort of the head god but preferred to be on a perpetual road trip instead, took an annual nighttime ride through the winter sky called the Wild Hunt.

Above: The holidays, now with 300% more heavy metal.

Variations of the Wild Hunt story exist in a bunch of European folklore--in Odin’s case, he usually brought along a bunch of supernatural buddies, like spirits and other gods and Valkyries and ghost dogs, who, the Vikings said, you could hear howling and barking as the group approached (GOOD DOGGOS).

That was the thing, though; you never actually saw Odin’s hunt--you only heard it. And hearing it did not spark the same sense of childish glee you felt when you thought you heard Santa’s sleigh bells approaching as a kid--instead, the Vikings said, you should be afraid. Be VERY afraid.

Because Odin could be kind of a dick.

Odin was also known as the Allfather, and like any father, he hated asking for directions. GPS who? I’m the Allfather, I’m riding the same way I always ride.

And that was pretty much it: “I took this road last year and I’m taking it again this year.”

“But,” someone would pipe up from the back, “there are houses on the road now--we’re gonna run right into them. We could just take a different path; there’s actually a detour off the--”

“Nope,” Odin would say. “They know the rules. My road, my hunt, my rules. We’re going this way.”

So if you were unlucky enough to have built your house along one of Odin’s favorite road trip sky-ways, he wouldn’t just plow right past you.

He would burn your entire house down--and your family along with it.

Kids playing in the yard? Torch ‘em; they should have known better. Grandma knitting while she waits for her gingerbread Einherjar to finish baking? Sucks to be her; my road, my rules, my beard, I’m the Allfather, bitch.

Above: Santa, but so much worse.

To be fair to Odin, he could be a cool guy sometimes. He just turned into any dad when he was on a road trip and wanted to MAKE GOOD TIME, DAMN IT, I AM NOT STOPPING; YOU SHOULD HAVE PEED BEFORE WE LEFT.

To ensure they didn’t incur Odin’s road trip wrath, the Vikings had a few ways of smoothing things over with Dad.

They would leave Odin offerings on the road, like pieces of steel (??? okay ???) or bread for his dogs, or food for his giant, eight-legged horse, Sleipnir, because the only true way to a man’s heart is through his pet.

People would generally leave veggies and oats and other horse-y things out for Sleipnir, whose eight legs made him the fastest flying horse in the world and also made him the only horse to ever win Asgard’s coveted tap dancing championship.

(Side note: EIGHT legs...EIGHT tiny reindeer...eh? Eh? See how we got here? Thanks, nightmare horse!)

Above: An excellent prancer AND dancer.

And if Odin was feeling particularly charitable and not in the mood for horrific acts of arson, children would also leave their shoes out for him--it was said that he’d put gifts in your boots to ring in a happy new year.

If all that didn’t work and the Vikings heard the hunt approaching, they would resort to throwing themselves on the ground and covering their heads while the massive party sped above them like a giant Halloween rager.

So this holiday season, leave your boots out for Odin and some carrots out for his giant spider horse or you and your entire family will die in a fiery inferno, the end.

3. Yule Logs

Speaking of Scandinavia, another Northern European winter solstice tradition was the yule log. Today, if you google “yule log,” something like this will pop up:

...which isn’t an actual log, but is instead log-shaped food that you shove into your mouth along with 500 other cakes at the same time because it’s CHRISTMAS, and I’m having ME TIME; so WHAT if I ate the whole jar of Nutella by myself, alone, in the dark at 3 am?

But that log cake is actually inspired by actual logs of yore that Celtic, Germanic, and Scandinavian peoples decorated with fragrant plants like holly, ivy, pinecones, and other Stuff That Smells Nice before tossing the log into the fire.

This served a few purposes:

It smelled nice, and Bath and Body Works scented candles hadn’t been invented yet.

It had religious and/or spiritual significance as a way to mark the winter solstice.

It was a symbolic way of ringing in the new year and kicking out the old.

Common belief held that the ashes of a yule log could ward off lightning strikes and bad energy.

Winter cold. Fire warm.

Everybody loves to watch things burn. (See: Odin.)

The yule log cakes we eat today got their start in 19th century Paris, when bakers thought it was a cute idea to resurrect an ancient pagan tradition in the form of a delicious dessert, and boy, howdy, were they right.

In any case, I’m 100% down with eating a chocolate yule log while burning an actual yule log in my backyard because everybody loves to watch things burn; winter cold, fire warm; and hnnnngggg pine tree smell hnnnnggg.

(Quick note: The word “yule” is the name of a traditional pagan winter festival, still celebrated culturally or religiously in modern pagan practice. It’s also another name for Odin. He had a bunch of other names, one of the most well-known being jólfaðr, which is Old Norse for “Yule father.” If you would like to royally piss him off, or if you are Loki, feel free to call him “Yule Daddy.”)

4. Upside down Christmas trees

I just found out that apparently, upside down Christmas trees are a hot new trend with HGTV types this year, so I guess this is one historical trend we did bring back, meaning it doesn’t really belong on this list, but I’m gonna talk about it, anyway.

Side note: Oh, my god, that BANNISTER. I NEED.

Historians aren’t actually sure where the inverted Christmas tree thing came from, but we know people were bringing home trees and then hanging them upside down in the living room as early as the 7th century. We have a couple theories as to why people turned trees on their heads:

Logistically, it’s way easier to hang a giant pine tree from your rafters upside down by its trunk and roots. You just hoist that baby up there, wind some rope around the rafter and the trunk, and boom. Start decorating.

A Christian tradition says that one day in the 7th century, a Benedictine monk named Saint Boniface stumbled across a group of pagans worshipping an oak tree. So, instead of minding his own damn business, he cut the tree down and replaced it with a fir tree. While the pagans were like, “Dude, what the hell?” Boniface used the triangular shape of the fir tree to explain the concept of the holy trinity to the pagans. Some versions have him planting it right-side up, others having him displaying a fir tree upside down. Either way, it’s still a triangle that’s a solid but ultimately very rude way of explaining God. Word’s still out on whether anyone was converted or just rightly pissed off that this random guy strolled into their place of worship, chopped down their sacred tree, and plopped HIS tree down instead. Please do not do that this holiday season.

Eastern Europeans lay claim to the upside-down tree phenomenon with a tradition called podłazniczek in Poland--people hung the tree from the ceiling and decorated it with fruits and nuts and seeds and ribbons and other festive doodads.

(God, who lives in these houses? Look at that. That’s like a swanky version of Gaston’s hunting lodge. Where do I get one? Which enchanted castle do I have to stumble into to chill out in a Christmas living room like that?)

Today, at least in the West, upside-down trees are making a comeback because...I don’t know. Chip and Joanna Gaines said so.

Some folks say it’s a surefire way to keep your cats from clawing their way through the tree and then puking up fir needles for weeks afterward, which checks out for me.

5. Incredibly weird Victorian Christmas cards

So back in the 19th century, the Christmas card industry was really getting fired up. Victorians loved their mail, let me tell you. They loved sending it. They loved getting it. They loved writing it. They loved opening it. They loved those sexy wax seals you use to keep all that sweet, sweet mail inside that sizzling envelope. (Those things are incredibly sexy. Have you ever made a wax seal? Oh, man, it’s hot.)

The problem, though, was that while the Victorians arguably helped standardize many of the holiday traditions we know and love today (Christmas trees, caroling, Dickens everything, spending too much money, etc.) back in 1800-whenever, a lot of that Christmas symbolism was, um...still under construction. No one had really agreed on which visual holiday cues worked and which...didn’t.

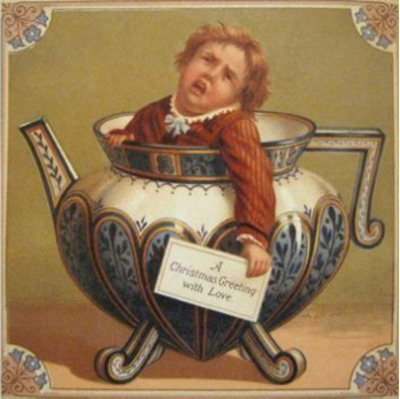

Meaning everyone just kind of made up their own holiday symbols. Which resulted in monstrous aberrations like this card:

What the hell is that? A beet? Is that a beet? Or a turnip? Why is it...oh, God, why does it have a man’s head? Why does the man beet have insect claws?

What is it that he’s holding? A cookie? Cardboard? A terra cotta planter?

And then there’s this one:

“A Merry Christmas to you,” it says, while depicting a brutal frog murder/mugging.

What are you trying to tell me? Are you threatening me with this card? Is that it? Is this a threat? How the hell am I supposed to interpret this? “Merry Christmas, hide your money or you’re dead, you stupid bitch.”

Also, why is the dead frog naked? Did the other frog steal his clothes after the murder? WHAT AM I SUPPOSED TO DO WITH THIS?

Victorian holiday cards also doubled as early absurdist Internet memes, apparently, because how else do I explain this?

Is this some sort of tiny animal Santa? A mouse riding a lobster? Like, the mouse, I get. Mice are fine. Disney built an empire on a mouse. And look, he’s got a little list of things he’s presumably going to bring you: Peace, joy, health, happiness. (In French. Oh, wait, is that that Patton Oswalt rat?)

But a LOBSTER? What’s with the lobster? It’s basically a sea scorpion. Why in the name of all that is good and holy would you saddle up a LOBSTER? I hate it. I hate it so, so much. Just scurrying around the floor with more legs than are strictly necessary, smelling like the seafood section of Smith’s, snapping its giant claws.

This whole card is a health inspector’s worst nightmare. It really is.

I gotta say, though, I am a fan of this one:

Presumably, that polar bear is going in for a hug because nothing stamps out a polar bear’s innate desire to rip your face from your skull than candy canes and Coke and Christmas spirit.

This next one is actually fantastic, but for all the wrong reasons:

I know everyone overuses “same” these days but geez, LOOK at that kid. I can HEAR it. SAME.

If you’ve ever been in a shopping mall stuffed with kids, nothing sums it up better than this card. This is like the perverse version of those Anne Geddes portraits that were everywhere in the late 90s. “Make wee Jacob sit in the tea pot; everyone will--Jacob, STOP, look at Mommy; I said LOOK. AT. MOMMY--everyone will love it.”

Actually, you know what? Every other Christmas card is cancelled. This is the only card we will be using from now on. This is it.

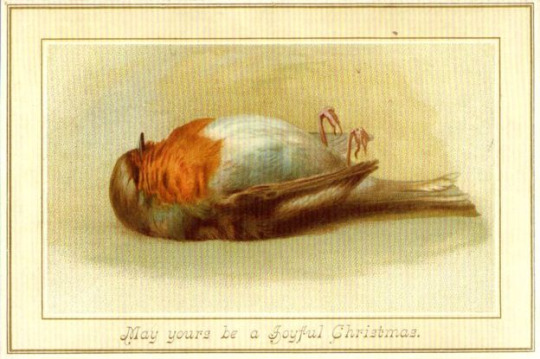

Wait, no. We can also use this one:

Merry Christmas. Here’s a fuckin’...just a dead fuckin’ bird.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve Never Seen David Lynch and George Lucas in the Same Room at the Same Time…

The thematic parallels between David Lynch and George Lucas are something I keep coming back to again and again, but their careers and evolution have a lot of overlap too. They were born in the earliest Boomer cohort (George Lucas in May 1944, David Lynch January 1946) and had experiences growing up that were colored by the idyllic 1950s, but shifted into a distrust of authority structures that was common for many of their age cohort in the 1960s. They both came of age wanting to do something physical with her hands that felt creative to them in large grimy spaces - fixing cars for Lucas, and painting and installations with a fascination with organic materials, industrial metal, and rot for Lynch. They both fell into film because they were looking for something that satisfied their artistic bent (although film was never a primary aspect of her life to that point). They wound up making a handful of short films over a 3 year period, culminating in a longer short-film that would eventually get them noticed at roughly the same age (Electric Labyrinth THX 1138 4EB [1967] and the Grandmother [1970] for Lynch).

These films netted both of them a patron (Francis Ford Coppola for Lucas, the American Film Institute for Lynch) and started filming their first feature-length film two years after those films. They both got their biggest name recognition bump by films released in 1977 and pulled away from the power of the studio system in roughly 1984. Famously, Lucas offered Lynch a chance to direct what would become Return of the Jedi in about 1981 ( I prefer the story where Lucas does this by picking him up in a Lamborghini - I’ve heard a phone call version too, but it’s not as perfect) and Lynch answered something like “it’s your movie George, you direct it.” They both spent the mid 80s in movie jail, and although they took very different paths in general after (I’ve been emphasizing the similarities) there are still things that jibe in the history - they both reminded people of what they liked about them with a late 80s movie, spent a lot of the 90s on TV projects, did one project around classic radio, returned to theatrical notice around the millennium, all the while generally keeping their own council and disappointing a lot of fans.

There’s obviously a world of difference. Lucas is a left brained technologist who equated freedom with an owning of the means of production. Lynch is it right brained impressionist seeing freedom-as no one ever being able to tell you what to do, acting as a solo artist with collaborators who merge with his sensibilities. Lynch is a production lone wolf, depending mostly on people believing in him and funding him, and losing out in the popular consciousness by making uncompromising art that may not be what the audience wants, meaning funding is sometimes hard to come by. Lucas is like the Democratic party controlling the Congress and presidency - having total power but unable to turn that into what he really wants to make, somehow. The idea of Lynch selling his body of work to Disney is absurd.

But the correspondences in this are telling and help to explain the thematic similarities and divergences. Plus, the differences often relate to the similarities - Lucas identifies with corrupted controlling paternalistic power as a horror of inevitable capture of the individual by larger structures, while Lynch sees the corrupted masculine influence as an archetype, the call coming from inside the house, agency coopted by a collective taint in the universal pattern . But on some level these are the same thing - what is this person I am capable of becoming seeing as I am in control but yet not, doing horrific things? Lucas’ constant commentary on slavery is about hegemony and a systemic oppression he is complicit in, while Lynch has whole pantheons of beings that turn people into vessels that oblate the self and make them act on subconscious programming. Neither probably think the word neoliberalism too much but tend to communicate similar things about it is almost diametrically opposed ways.

The thematic similarities are rooted in a few areas that unpack in to a variety of subspaces which overlap – patriarchal structures as psychoanalytic dynamics (more Freudian father fixation for Lucas, Jung for Lynch), boomer generational failure as socio-first-but-economics-ultimately, the artist as in struggle with larger forces (largely of the self), and an eastern religious metaphysics that is American Christian in flavor. The major line of difference running through this is gender/sex/desire, Lynch being on main with a lot of spiritual overtones of sin, guilt, and “the fall” and Lucas finding this kind of guilt and sin as a secondary phenomenon that is mostly actively suppressed and unconvincing when it shows up; yet both wind up often finding physical consummation at direct odds with art in a gendered creation way (that also links Eraserhead to Age of Ultron and the original Frankenstein). Try doing a psychosexual reading of Howard the Duck sometime.

Lucas’ developmental through line is this: dude in love with 50’s culture but informed by 60s counterculture makes a movie where the young granola-ish revolutionaries win against the fascists in an effort to rewrite society but, having secured rights for “independent spirit” reasons now finds himself in control of something huge and immediately starts making art about boomer men becoming their controlling fathers and then moves on to movies where powerless freaks are the real focus. After a creatively fallow period, he comes back to make a sequel/prequel trilogy that is one of the most misunderstood complicated statements about people becoming what they hate as an eternal cycle at the level of the personal, the societal, the political, the spiritual, the artistic, you name it!

Lynch’s developmental through line is this: dude in love with 50’s culture but informed by 60s outsider/art counterculture makes a movie where the young artist struggles with the idea of a regular life, initiated by fatherhood, which attempts to destroy the artistic spark, after which he enters the Hollywood system and makes an artist as freak movie and a movie about plucky rebels conquering space authoritarianism (that the future of is books about that ending in messianic authoritarianism) and then disavows that system. He then proceeds to make art about subject and object as a supremely gendered thing, in a land that has fallen from grace, moving inexorably towards the idea of eternal cycle at the level of the personal, the societal, the political, the spiritual, you name it!

They both have an idea of the father-artist identified with the abject oppressed, under siege as figure, resentful from being kept from creation, over a career realizing that their “self” is the horrific villain of their own story. For Lynch, this is psychosexual, then spiritual, with a resisted toxic masculine urge to control and overwhelm, often in a violent way. It is the artist’s own urges that get in the way of making art, of desiring in the universe that has an unbalanced power structure from some far off echoes of an original symmetry breaking inherent to the archetypal gender dynamic. For Lucas, it is the realization that the artist in control has a tendency to become the controlling dad and sexual relations are inherently problematic in a political and spiritual way. Real art seems impossible if the artist has control, identifying with the downtrodden is a bit of a lie, happy endings can’t happen not because of the happiness bit because of the ending bit. For both, there is a fundamental flaw in the cycle, which is patriarchal in nature, but Lynch just approaches this much hornier.

The boomer part probably requires the most discussion, but the TLDR is that they are both are crawling out, through Vietnam, from the 50s social order, and grappling with how badly the 60s idealism failed. Lucas does this in the prequels as a big canvas critique of how the social revolution was co-opted by the generation not being able to see its own flaws, of not seeing the system taking over again, an Empire calling itself a Republic. An inability to look in the mirror and really see. The wisest oldest hippie is the only one who sees what’s happening, but is powerless as his apprentices are inevitably spit out, and the next generation has to be raised not by a skeptic but a true believer in “liberal” “democracy” (cynic quotes theirs).

Lynch is interesting here in that he most directly addresses this only in Twin Peaks, but we see more naked reflections, divorced of contemporary politics, in his other works. In Twin Peaks, Ben Horn is the Palpatine figure, who winds up a sweet old man buying off the harm his life’s work and progeny have produced while ignoring the poor and next generation personally. Jacoby the neutered, fried Yoda that eventually slides into Alex Jones territory (the canonical Boomer ethos in a nutshell – “what me” neoliberalism and change the world ideology going crackpot). All of Twin Peaks except for Fire Walk with Me is directly socioeconomically generational (Bobby Briggs becomes a young Republican in season 2, the mill, the trailer park), but the other works are full of class issues informed by Lynch’s age. From Blue Velvet’s suburban kid exploring his darker side by going to the poor part of town through a career of classist low-life encoding (Bob is a denim jacket wearing homeless person, all the covered in grime by the dumpster/trailer park characters, Ronette as the factory floor version of Laura, etc), culminating in Inland Empire and Twin Peaks the Return chronicling the fall of man as partially an (generationally specific in TP) economic fall into a unequal class defined world of needing an opening and leaving the house to labor as where evil is born. TP OS is about how boomers turned out just as bad, the Return is about how we inhabit the world of their ideological blindness.

All filmmakers seem to, at least to a certain degree, bring the question of creation of art directly into their work via distant or close metaphor. In Eraserhead and Elephant Man, Lynch values the spark of art which the downtrodden protagonist is trying not to lose. In Dune, the visionary with a big project that seeks to upend the system (but that we know eventually become something even worse) is a project that fell apart due to studio interference. Blue velvet is about the act of watching awakening something uncomfortable in us that is incompatible with normie life (it wouldn’t be weird to say it was about porn). Twin Peaks is about television, FWWM about movies, and all at least partially about closure being a death act in art. Lost Highway is about the artist tortured by desire, Mulholland Drive about desire being central to be eaten alive by the Hollywood system. Inland Empire is about filmmaking as a way into understanding the world on a deeper level (as is its unofficial sequel Inception) to cure its ills. All of this is art’s struggle against power, with an element of the major powers being subconscious forces that control us leading to desires that ablate the artistic impulse.

Lucas' projects have over time been about a young upstart independent filmmaker, losing his soul by becoming successful, and becoming the system, man. He then tries desperately to identify as really not the one in charge, until he admits to what he has become. He consistently dips back into filmmaking as an adventure or a good fight, but he has to set these in a time period before his birth. As in Lynch, having a child is equated with not being able to fulfill the kind of artistic destiny, but Lucas goes further in equating it to an excuse for why the powerful artist goes bad and needs redemption. He had a naïve or-is-it canny motif focused on the short inhuman outsider, often related to music or primitive settings (often with wooden cages) as a recurring thing for a while. These characters are often wise, or at least no filter tell-it, and are similar to the Elephant Man. This is a trope, sure, the wise different wavelength other, but there is also an identification of the artist at knowing and right yet impotent and a clue to the author’s metaphysical system.

Lynch is the mainline protestant in upbringing and very much influenced by a kind of proto-eastern religion (you can just say the Vedas for shorthand). Lucas is not very religious, but was brought up Christian, influenced by Christian symbolism and became interested in world religion as narrative via figures like Joseph Campbell. Hence, they both gravitate towards some kind of Gnostic Proto Christian, So-Cal zen, Thomas Aquinas “gets” Plato kind of amalgam, which informs their work. Lynch has veered towards an eternal cycle framework, and the very physics compatible idea of something in the past breaking and causing consciousness/suffering, through which we can achieve joy as a counter only through letting go of the self, and the recurrence of ruptures on all scales demonstrating a fractal pattern of hurt and redemption. Lucas also sees a big cycle, but it is one more of human existence as narrative that has a tendency to return, with a little bit of Nietzsche and movie eastern spirituality thrown in. Both believe in a recurring pattern that plays itself out in a way that is terrible, but hopeful, as the struggle is where hope derives from. Both have inherently Christian ideas and symbols in their work but lean back on non-Christian ideas that the Christian ideas have a history with. Lynch has his virgin Mary as the real Christ figure female angels that show up, while Lucas has turnt space Jesus.

Suffice it to say that the tree trial scene in the Empire Strikes Back and the lodge sequences in Twin Peaks are a very good place to start looking for how the two auteurs meet. Compare Anakin/Luke Skywalker to Mr C, look at the 90s turn they both made, register their seeing the “sleeper must awaken” of fiction being terribly fraught, compare the force vs. the universal field, the way their relationship status and partners carve their work into eras, and their continued existence as mainstream experimental filmmakers.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

LHP, ATHEISTS AND SPIRITS

I see at times so many attempts to define or to "purify" what the LHP is, while forgetting perhaps that the truth of it is not in simple dissections or refutations, but in a greater understanding that encompasses all the undercurrents.

For example, the classic opposition between Noetic (or Philosophical Approach) versus Spiritual (not blind faith). Why do these have to be mutually exclusive? By all means, it's like condemning a part of the self to favor another. It makes no sense to me. There is a place for logic and philosophical arguments (without which we would be like animals) and there's a place for the spirit. I am all in favor for experimentation but this doesn't have to be in opposition to magic for example. I totally don't get why some choose to set themselves against the belief systems of their supposed brethren, even if they are quite close.

Perhaps my own understanding of LHP is at fault; I know that by being solitary perhaps one may mistrust groups/guidelines, but on the other hand, it's a Path - meaning that it is a Way of Life, a Practice and something that integrates certain sets of behavior with belief, evidence, practice (ie ritual) and many more depending on the definition. So for a LHP person to call another person or a group not LHP just because they are focused more on the magical/ritual element instead of the noetic, seems absurd to me. I know that it is quite trendy to go against the theistic principle or anything that resembles faith or a spiritual system, but surely any person that would refute that as LHP would have to discredit the Yezidis, the demonolater communities everywhere, those who accept Set as a distinct Entity external to us, those that practice draconian magic, the Vodou and so on... there are simply too many examples of LHP that the materialist or overtly sceptical tends to discredit all too easily, in favor of what? his mind?... and why would this be More LHP than those who practice on the Path under the tuition of demons, for example?

I personally think that all modalities of thinking have their use, much like the Aeon of Horus has/d its use but that doesn't mean that the Aeon of Set for example is not the prime example of xeper and deification. So why would anyone seek to adopt a certain stance that only would be useful in serving as a modality and not as a universal tool? Crowley's Thelema and La Vey's attitudes certainly served the LHP well, but to become stuck on these is to limit oneself while there are so many more things to experience and to explore. And in private conversations I have lately heard the same old argument, that faith stems from christianity... I would like to remind that faith predates christianity (or other monotheistic religions) for dozens or even hundreds of millennia (depending on whether one studies ancient Egyptian - Kemetian scripts or Sumerian including the Isin King List). Faith is much like logic; it's a tool. Faith, in the right hands can achieve certain altered states and access different experiences that could transform the self. Of course, we have seen the misuse of faith all throughout history with the fanatics, the burning of the libraries of the ancient world, the crusades, the inquisition etc... but just because monotheistic religions perverted faith and spirituality, doesn't mean we have to throw away traditions predating them since the Dawn of Man.

Evidently there are many LHP practitioners who are atheists and who simply choose to exalt the Self as the centre of everything in their universe. Whereas the Self is indeed very important in freedom, choice, and consequence, I never was an atheist nor do my personal experiences validate a cosmic paradigm devoid of spiritual presences. I also do not subscribe to the notion that all Deities/Entities/Spirits/Demons are parts of our brain. I believe that they correspond to areas of our brain (like linking to old phrenology charts) but that is all; correspondence is not the same as Identity, so through my own experience such entities have a truly external Essence and Identity. While correspondence to brain parts is probably essential in order to sense something that would normally lie outside the realm of human senses, I am certain that they do exist externally to me. The Self is important for many things such as initiation, becoming/xeper, constructing an interface with reality, however I don't accept that the Self is the only deity there is.

For example, let's take Set. I have significant personal evidence (but not proof to convince cynics) that this deity is Indeed a true Deity, external to me. Some would argue that Set is the only true deity, others could say there are others (neteru or something else) that are also true.

So assuming that one accepts the existence of deities that are superior or external to Self, there are different stances/ paradigms as to dealing with this: demonolatry for example would worship or offer ritual honors to such entities. While others would seek to control them for own gain using grimoires/demonologies etc which is something entirely different. Some would attempt to use such energies in order to "harvest" specific results for themselves, either as part of self-transformation or as part of micromanaging life with its problems. On the other side of the spectrum, RHP would use parts of this knowledge to attempt to exorcise these deities (for them they would all be classed as demons anyway).

Something metaphysical truly exists beyond the Self, whatever that is. Any model of self-transformation does not contradict to the existence of said deities/spirits/demons nor do I see any issues with tuition from such immaterial beings.

As for the other worlds and their denizens/ deities/ daemons etc, I accept the existence of a mental stratum acting as the interface between the entities and the mind. Even if the Otherness is extreme so that the entity cannot be easily discerned, this mental interface allows for it to be "clothed" in a particular disguise that is somewhat acceptable within certain parameters of the socio-cultural paradigm as well as the era in which one lives. Perhaps from a different stance all worlds are one in essence, despite their individual differences, much like hues in color in a vast and incomprehensible painting. If such entities / creatures of Otherness are known to exist, there must have been some evidence in the works of those that worked with them, such as Michael Aquino when contacted by Set, Aleister Crowley with regards to Aiwass etc. These Beings were described in such a way as to imply independent existence and individuality. Whether these voices were symbolic, or partly covered in archetypal forms, or actual Entities, matters very little since they had tremendous impact on the entire LHP spectrum. In terms of validity, it's almost impossible to discern whether these are actual Beings external to the Self, but even though LHP people like to believe in total freedom, they commonly accept what widely known figures such as LaVey, Aquino, Crowley say as authorities on the path. But even their words would have to be validated through personal experience. And here the endless arguments take place, hopefully eloquently and politely and with mutual respect between those who support the archetype theory or the beings from another world/dimension. Even if the conversation takes place with the best of intentions, I doubt whether much will be gained from it due to the fact that each side tends to be firmly entrenched and frankly it's quite difficult for experienced people to just change their mind. It is true that there's no clear yes or no to these things; for example demons could be true actual beings from another dimension, or they could be shells, almost robotic in nature, or they could be an Order's egregore, or a thought-form, etc. All these could be argued that they could produce results, but for different reasons / mechanisms. And sometimes this makes all the difference.

To me LHP is about the only type of Spirituality that can access and harness the power needed to break the chains put on us by monotheistic paradigms for millennia. It frees the mind from many illusions while redefining social cohesion under a new light, while assisting the individual achieve Luciferian Gnosis and at the same time, xeper as in Becoming and a state of being initiated all the time.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyper Grace

For almost 17 years, Apostle Paul preached the Gospel of Grace through his God given revelation alone. He preached Christ sa loob ng panahong 'yun without being taught by any of the Super Apostles (12 Appointed Apostles). Now it happened sa Acts 15 that while he and Barnabas stayed at Antioch, some men from Judea ay nagsimulang magturo ng ganito, "Liban na kayo ay matuli ayon sa alituntunin ni Moses, hindi kayo maliligtas (Acts 15:1)."

Why is it that those men from Judea had such belief? Ang pagtutuli kasi or circumcision ay naging mandato ng bansang Israel mula pa nung panahon ni Moses. It is included in the Law, or the Torah---the Constitution and Bill of Rights of Israel nuong Old Testament times.

Paul and Barnabas had a small dissension with them, because such teaching is against Christ's Gospel. They are committing the common error ng mga Christians-influencers ngayon, an error that is rooted from their failure in rightly dividing the word.

2 Timothy 2:15 (New King James Version)

“Be diligent to present yourself approved to God, a worker who does not need to be ashamed, rightly dividing the Word of Truth.”

Sa mga di aware, the Word of Truth or the Scriptures should be divided because there are two existing major covenants in its entirety. The Law Covenant (from Moses to John the Baptist, ending after the the veil of the temple was torn in two) and the Grace Covenant (which began when Jesus ascended to the Father’s right hand).

The problem is this people from Judea are mixing Law and Grace, and in the process nullifies Christ’s finished work---Galatians 2:21, “I do not nullify the grace of God, for if righteousness were through the law, then Christ died for no purpose.”

Isipin mo nalang, kapag pala may taong malapit nang mamatay, hindi pa pala sapat na paniwalaan lang nya ang Gospel, dapat tutulian pa muna sya. Kasi baka harangin s'ya sa pintuan ng Kaharian ng Langit at sabihin sa kanyang, "Oops! Bawal ka dito, supot ka pa!" Tapos pagdating n'ya sa impiyerno, tatanungin s'ya ng mga bantay dun, "Anong kasalanan mo at 'di ka nakapasok sa langit?" at sasagot naman 'yung tao, at sasabihing, "Supot pa po kasi ako." Even though biro lang 'yan, pero if you will insist that Faith in Christ is not enough to save a person, then that joke is true to you. Hence, isang malaking kalokohan ang eternity mo.

Going back dun sa scenario, after having a dissension with this Judeans, they decided to settle the issue by asking the Head Council of the Church at that time. Alam mo ang matindi? Kahit maraming taon na ang nakalipas after Christ had ascended, marami pa'din sa mga apostles and disciples ay walang firm knowledge about this issue.

Acts 15:7 reveals to us that there has been much debate. And maybe Apostle Paul was amazed din, kasi for 17 years that they were sharing the Gospel of Grace, ito pala ay hindi pa’din klaro sa mga Apostles at Disciples na unlike him ay nakasama si Christ all throughtout while He was still on earth. They heard Jesus teach for more than three years, yet parang hindi nila nakuha ang pinakang punto ng lahat ng tinuro ni LORD.

Buti nalang biglang sumingit si Pedro at sinabing, "Mga kapatid, alam natin na nung mga naunang araw, pinili ako ng Diyos para sa pamamagitan ng aking bibig ay marinig ng mga Hentil ang Magandang Balita at maniwala. At ang Diyos ay naging saksi sa pamamagitan ng pagkakaloob sa kanila ng Banal na Espiritu gaya ng ginawa N'ya sa atin, hindi S'ya nagtaguyod ng pagkakaiba sa pagitan natin at ng mga Hentil ng linisin N'ya ang kanilang mga puso sa pamamagitan ng pananampalataya (Acts 15:7-9, paraphrased by me.)” and then Acts 15:10-11, "Bakit sinusubok ninyo ang Diyos? Bakit ninyo iniaatang sa mga mananampalataya ang isang pasaning hindi nakayang dalhin ng ating mga ninuno at hindi rin natin kayang pasanin? Sumasampalataya tayo na tayo'y maliligtas sa pamamagitan ng kagandahang-loob ng Panginoong Jesus at gayundin sila.”

Ulitin ko 'yung verse 11 in English para super clear: Acts 15:11, "But we believe that we will be saved through the grace of the Lord Jesus, just as they will.”

Let's be real! At the end of the day you will fail. The standards you set, ikaw din mismo ang magre-reset. Then ikaw din mismo mapapagod at maiintindihan sa sarili mo that it's not about what I should do, rather it's about what Christ did for me.

Cheap Grace. Hyper Grace. Ano pa ba? Bakit hindi mo aralin mismo sa sarili mo ang Kasulatan, imbis na patuloy na panghawakan ang mga preconceived notions and dogmas na tinanim sayo ng mga nakakataas sayo. Don't you know that Jesus wants to reveal Himself personally to you? Why not stop pursuing your idols and start focusing on pursuing no one but Jesus?

I'm hearing people, labeling us that we tolerate sin. That we teach na okay nang magkasala. You develop such stereotype only because you won't hear us completely. Don't you know that even si Apostle Paul ay pinaratangan din ng mga ganan? See Romans 3:8 and Romans 6:1-2. Because he would say things like this, Romans 5:20, "Now the Law came to increase the trespass, but where sin increased, grace abounded all the more."

I won't deny that what we preach is Hyper Grace, alam mo kung bakit? Kasi God's Grace itself is Hyper. Look at Apostle Paul? Look at Peter who denied Christ three times? Look at Thomas who still doubted after everything that Jesus did? And look at the other apostles and disciples who doubted the testimony that Jesus has risen from the dead (Mark 16:14)? Sa tingin mo hindi pa ba Hyper Grace 'yun that Jesus still retained them as His servants?

Even nung hindi pa naku-crucify si Christ, don't you know that God had been very gracious? Moses kind of break God’s principles when he married a Cushite woman other than his first Midianite wife Zipporah (Numbers 12:1); his sister Miriam tried to deal with him pero God defended Moses. Adam and Eve sinned, they were found naked and afraid, pero pinagtahi pa'din sila ni God ng damit to cover their shame (Genesis 3:21). That's what Jesus did to us. We were found naked because of our sins, but Christ put off His robe of righteousness to put it on us, hence He became sin and was crucified for our sake (2 Corinthians 5:21).

If Grace is not hyper? Why it is then na sa Romans 5:20, the original Greek word there for the English word ‘increase’ is the word hyperperisseuō? Revealing that when sin increased, grace didn’t just increase but it hyper-increased.

The real erroneous teaching is the idea that grace can be attain apart from Christ. And to teach that there’s no hell and that everyone will go to heaven is absurd. Kasi holiness, justification and adoption can only be attained by being one with Christ through faith. Without the hearing of the Gospel there will be no faith in Christ, and if there’s no faith in Christ, then that person cannot be in Christ. Hence he/she is still under God’s wrath and has no share sa inheritance ng mga saints.

2 Corinthians 3:16-18, “But when one turns to the Lord, the veil is removed. Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom. And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another. For this comes from the Lord who is the Spirit.”

We preach grace in its true form, unlimited and abounding, because that’s what made us see grace as from God. Ang tao, kapag nagbigay ‘yan ng pabor, it’s either limitado o may hihinging kapalit later on. Why then are we treating God like human? Why do we put a limit to His grace and then treat the power of sin greater than the power of the blood of Christ? Bakit hindi natin mailagay sa kokote natin na palaging hihigit ang biyaya sa kapangyarihan ng kasalanan, kaya imposibleng maging alipin pa tayo ng kasalanan.

Romans 6:14, "For sin will have no dominion over you, since you are not under Law but under Grace."

1 John 3:9, “No one born of God makes a practice of sinning, for God's seed abides in him; and he cannot keep on sinning, because he has been born of God.”

See that? A child of God cannot keep on sinning, kasi God will take care of Him and will help Him grow in righteousness.

Romans 5:17, “For if, because of one man's trespass, death reigned through that one man, much more will those who receive the abundance of grace and the free gift of righteousness reign in life through the one man Jesus Christ.”

What was said there? If a person’s mistake caused too much disaster, don’t you think that God, by a single offering, will be able to fix such mistake? If sin is so powerful that it was able to enslave the whole of humanity, paanong hindi ito mahihigitan ng nag-uumapaw na biyaya ng Dios? If Adam’s sin caused all of humanity to become sinners, paanong hindi hihigit duon ‘yung epekto ng libreng katuwiran na nagmumula kay Hesus?

Kaya surely those who have received the hyper grace of God and His free gift of righteousness will triumph over sin and its entirety through the one man Jesus Christ.

0 notes

Text

Dreamers (2021)

Working toward a better world, a world of racial justice and an end to interlocking oppressions, requires imagination. On this weekend when we remember the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., let's also consider both the history of civil rights and the unbounded creativity of speculative fiction by writers of color as sources of inspiration.

Expanded and revised for the Washington Ethical Society, presented January 17, 2021.

“We are creating a world we have never seen,” writes Adrienne Maree Brown in Emergent Strategy. On this weekend, as we remember the legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., support a peaceful transfer of power, and recommit to his legacy and the work of civil rights yet to do, it may seem like a luxury or a distraction to engage with imagination. It is not. Just like we cannot allow oppression to steal our joy, we cannot let it steal our imagination. Neither threats of violence, nor attempts to push us into re-creating a fictional and regressive society of the past, nor manufactured austerity preventing relief from reaching working people, nor white supremacy in any form should be allowed to steal our imagination. Our ability to dream of a better world is a matter of collective survival.