#anapana sati

Photo

The Quest for Buddhism (113)

Buddhist cosmology

Samatha meditation

Samatha meditation (samathabhāvanā) is a meditation that cultivates concentration by attaching the mind to a specific object. Samatha is a Buddhist term for settling the mind on one object, often is translated as the "tranquility of the mind", "mind-calmness", or “cessation”.

The Pali Canon describes it as one of two qualities of mind which is developed (bhāvanā :Ref) in Buddhist meditation, the other being vipassana (insight).

In Theravada Buddhism there are 40 different meditation objects in total, called Karmasthana or Kammatthana. The meditation on compassion(Ref2), a type of samatha (cessation), is often performed as a preparatory step to Vipassana meditation (vipassanābhāvanā, lit. contemplation). The most commonly used samatha is anapana sati (Skt: anapana-smrti), which is a breath-controlled meditation.

[上記引用: “慈悲のこころは仏教の基本である。「生きとし生けるものが幸せでありますように (巴: サッベ-サッター・バーヴァントゥ・スッキータッター)」というのが、その基本となる精神である。”]

仏教の探求 (113)

仏教の宇宙論

サマタ瞑想

サマタ瞑想 (サマタめいそう、巴: サマタ・バーヴァナー)は、心を特定の対象に結びつけて集中力を養う瞑想である。サマタ(梵: シャマタ)とは、仏教用語で、ひとつの対象に心を落ち着かせることであり、しばしば「心の静寂」「心の落ち着き」または「止 (し)」と訳される。

パーリ仏典では、仏教の瞑想において「心の発達 (巴:バーヴァナー参照)」の2つの性質のうちの1つであり、もう1つはヴィパッサナー(観・洞察)であると説明されている。

上座部仏教では業処 (ごうしょ、巴:カンマッタ-ナ、梵: カルマスターナ)と呼ばれる瞑想対象が40種類ある。ヴィパッサナー瞑想(ヴィパッサナーめいそう、巴:ヴィパッサナー・バーヴァナー、観行の意)の準備段階としてサマタ(止) の一種である慈悲の瞑想(参照2)が行なわれることが多い。最も一般によく使われるサマタは呼吸を対照する安那般那念 (あんなはんなねん、巴: アーナーパーナ・サティ、梵: アーナーパーナ・スリムティ)である。

#samatha meditation#vippasana meditation#buddhist meditation#buddhism#buddhist cosmology#meditation on compassion#compassion#insights#tranquility of the mind#mind-calmness#cessation#anapana sati#philosophy#nature#art#buddha

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Il contraltare della concentrazione

Il contraltare della concentrazione

Piovono rane, piovono zerbini, nevica luce, ma senza pause, soffice-mente. Giustappongo frammenti di pensieri. A che pro? Nella speranza di trasformare il mio puzzle in un discreto mosaico, certo che qualche spirito eclettico ne coglierà l’afflato, mentre non si tratta, tutt’al più, che di un semplice gioco. Per ingannar qualcuno? No, è solo l’ennesimo tentativo per illudermi di riuscire a…

View On WordPress

#amore#anapana sati#attenzione#concentrazione#fermarsi#focus#infinito#interiorità#meditare#meditazione#mente#osservare#respiro#rilassamento#spiritualità#tempo#trataka

0 notes

Photo

Làm Sao Biết Cách Sống Cho Hiện Tại? 🌱

Dhamma là con đường của bây giờ và ngay tại đây. Bởi vậy chúng ta phải phát triển khả năng ý thức được giây phút hiện tại. Chúng ta cần một phương pháp để chú tâm vào thực tại ngay lúc này. Kỹ thuật anapana-sati (ý thức về hơi thở) chính là phương pháp này. Thực hành phương pháp này sẽ phát triển sự ý thức về chính mình ngay tại đây và ngay bây giờ: Ngay lúc này thở vào, ngay lúc này thở ra. Do thực hành ý thức về hơi thở, chúng ta nhận biết được thực tại.

Nguồn: https://theravada.vn/nghe-thuat-song-chuong-6-tu-tap-dinh-tam-2/

#nghethuatsong #goenka #ducphat #buddha #gotama #dhammatalk #theravada #phatphap #phatgiao #phatgiaotheravada #phatgiaonguyenthuy #dhamma #buddlist #buddhism #tungkinh #meditation #thiền #vipassana #thienvipassana #buddhateachings #sangha #nibbana #peaceful #peace #mindfulness

#nghethuatsong#goenka#vipassana#thienvipassana#phatgiaonguyenthuy#meditation#phatgiao#theravada#thiền#buddhism#buddhateachings#dhamma

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anapana Sati, Buddhist Breathing Meditation

by Saṃsāran

There is only one kind of meditation described by the Buddha which requires a specific posture and that is Buddhist breathing meditation Anapana Sati. All of the others can be done from any posture.

Anapana Sati is a very simple exercise. You are mindful (sati) of the observed breath (anapana). That is to say you sit crosslegged if possible, back erect and breathe evenly and as you do observe the sensation of the breath as it enters the body, is retained and exhaled. Focus your complete attention on the breath.

That’s it. Do this twice a day for five minutes. Just breathe and observe the breathng.

Now here is what is going to happen if you do this. First a chaotic swirling of thoughts. Then, maybe a little calm. Some quiet. Then, after regular practice, you will feel a burst of joy. It will fade and you will want to feel it again. With practice you will be able to sustain it for longer and longer periods. This joy is the first stage of a process.

I know this sounds simple but the peace this brings can change lives.

Is it religion? Is it philosopy, psychology or just an ancient brain hack? I dunno. It works and that’s all that matters.

The full yogic breath with teacher Kavita Maharaj

youtube

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lợi ích của Thiền Vipassana cho bản thân và xã hội

Lợi ích của Thiền Vipassana cho bản thân và xã hội

Usha Modak

Thiền Vipassana là một phương pháp để giúp chúng ta có được một đời sống nội tâm lành mạnh, an lạc. Sự an lạc nội tâm được gia tăng tùy theo sự tiến triển của cá nhân về mặt tâm linh. Ngài Gotama đã tìm thấy lại phương pháp này trong lúc thiền định một cách sâu xa. Ngài đã giác ngộ và giải thoát trong phương pháp này. Với lòng từ bi và tình thương vô biên, Ngài đã chỉ dẫn pháp môn này để giúp chúng sinh thoát khổ. Đời sống văn minh hiện đại tiến nhanh đến mức độ tranh thủ một chút thời gian để thở cũng không có. Cuộc sống bon chen, cạnh tranh như là cuộc chạy đua quyết liệt mà không có người thắng; những tiện nghi vật chất, những trò chơi phong phú, những cải tiến tốt nhất về kỹ thuật đã không làm cho con người sung sướng hơn. Về mặt vật chất, sự tiến bộ của loài người trên phương diện khoa học, kỹ nghệ và chính trị thật to tát. Con người là kẻ sáng lập và là kẻ tiêu thụ những phát minh này, nhằm mục đích cải thiện và hài hòa nếp sống của con người. Nhưng sự thực có phải như thế không? Chúng ta hãy nhìn rõ những xã hội trên thế giới được gọi là "văn minh hiện đại". Mặc dầu phát triển tối đa về phương diện học vấn, sức khỏe và kỹ thuật, nhưng họ lại đang rơi vào tình trạng khủng hoảng do bệnh tâm thần, nghiện ngập, tự tử, phạm pháp và tội ác đang gia tăng... Một xã hội được hình thành bằng những phần tử cá nhân, mỗi một cá nhân trong xã hội hiện đại không ít thì nhiều, là nạn nhân của sự căng thẳng và lo lắng. Mỗi một phút giây trong cuộc sống của họ là sự giằng co giữa vật chất và tinh thần. Xã hội vật chất đã thôi miên con người, làm cho con người chỉ biết bỏ thời gian để làm ra tiền và tiêu tiền. Con người trở thành nô lệ cho những dục vọng của chính mình; nói cho văn hoa hơn là con người có hoài bão, nguyện vọng, mục đích và lý tưởng. Những thứ này ít khi nào ta được đầy đủ, bởi vì chúng là nguyên nhân tạo ra những thất vọng, buồn khổ và bất mãn; cho dù ta "có" hay "không có". Do đó, đau khổ là một vấn đề chung của con người. Đau khổ không dành riêng cho một đất nước nào, một dân tộc nào, hay một đoàn thể riêng biệt nào, mà là cho tất cả những ai có mặt trên trái đất này. Vì đau khổ là một "bệnh" chung cho nhân loại nên "thuốc trị" cũng chỉ có một thôi, đó là thiền Vipassana. Căn bản của một xã hội lành mạnh, tốt đẹp phải là một xã hội gồm có những cá nhân tốt lành. Mỗi một cá nhân có những ý tưởng lành mạnh, tốt đẹp sẽ giúp cho xã hội tốt đẹp và lành mạnh theo. Thiền Vipassana là một phương pháp để giúp chúng ta có được một đời sống nội tâm lành mạnh, an lạc. Sự an lạc nội tâm được gia tăng tùy theo sự tiến triển của cá nhân về mặt tâm linh. Ngài Gotama đã tìm thấy lại phương pháp này trong lúc thiền định một cách sâu xa. Ngài đã giác ngộ và giải thoát trong phương pháp này. Với lòng từ bi và tình thương vô biên, Ngài đã chỉ dẫn pháp môn này để giúp chúng sinh thoát khổ. Phật không lập môn phái hay bảo mọi người phải tôn sùng Ngài. Phật chỉ dạy thiền Vipassana, một phương pháp để tẩy sạch cái tâm tham, sân, si của chúng ta. Thiền Vipassana là gì? Đây không phải là một nghi thức dựa theo sự tin tưởng mù quáng. Không có sự hình dung, tưởng tượng Thượng đế, các thần thánh hay một vật gì, cũng không có sự tụng đọc thần chú; càng không phải là một sự giải trí về trí óc hay triết học. Vipassana có nghĩa: "passa" là nhìn , là quan sát, và "vi" là một cách đặc biệt. Vipassana nghĩa là quan sát theo dõi chính mình một cách đặc biệt. Đây là một cách thanh lọc tư tưởng, để giảm thiểu tối đa những sân hận, tham lam, ích kỷ, v.v... bằng cách tự quan sát chính mình và soi xét nơi tâm. Đây là "thiền sáng suốt", giúp chúng ta nhìn thấy sự vật như "nó là", chứ không phải như thế này hay thế khác, hoặc thấy sự vật qua lăng kính đủ màu. Đây là một phương pháp giúp chúng ta sửa đổi những tập quán tham đắm, si mê đã in hằn trong tâm khảm từ lâu đời lâu kiếp. Thiền Vipassana được dạy căn bản trong vòng mười ngày. Khóa học đòi hỏi học sinh phải quan sát sự yên lặng và tuyệt đối tuân hành theo những luật lệ. Thời khóa biểu hàng ngày, trung bình, là mười tiếng thiền định, với những giờ giải lao. Lời hướng dẫn được đưa ra từng buổi trong ngày, và mỗi chiều có thuyết pháp bằng "videotape" của Thiền sư S.N. Goenka, giải thích những thắc mắc gặp phải khi tọa thiền.

Có ba bước thực tập trong khóa Thiền Vipassana.

Thứ nhất, quan sát về năm giới cấm, những giới này ngăn cản sự bạo động, nói láo, ăn cắp, gian dâm, việc sử dụng rượu cùng những chất kích thích xấu. Tóm lại, sự quan sát về những giới này giúp chúng ta hành động đúng, sống đúng và nói lời thành thật. Khi một người phạm những giới trên, tự họ đã làm vẩn đục tư tưởng của chính mình. Những cái không tinh khiết là gốc rễ của căng thẳng, bất an, mà ai ai cũng muốn từ bỏ chúng.

Khi bạn thực tập Thiền Vipassana, trong lòng bạn nên hiểu rằng: mỗi lần bạn phạm một điều, trước hết tự mình làm khổ mình, và sau đó làm khổ người. Khi mà bạn tức giận, bạn cảm thấy khó chịu, khổ sở, như thế thì làm sao bạn an lạc được? Đó là luật tự nhiên.

Một sự thật không chối cãi được. Bước kế tiếp là làm sao để làm chủ cái tâm lăng xăng lộn xộn của chính mình, phương pháp thực tập là chú ý vào hơi thở, còn được gọi là Anapana-sati. Không cần tưởng tượng hay tụng niệm gì, chỉ quan sát hơi thở ra vào một cách tự nhiên. Sự tập trung này giúp cho tâm trí chúng ta nhạy bén hơn. Và sau đó, thiền sinh sẽ bước qua giai đoạn kế tiếp của Vipassana, đó là quan sát những cảm thọ trong cơ thể từng phút giây, giai đoạn tập trung liên tục giữa tâm và thân. Tâm trí chúng ta luôn luôn phản ứng theo những điều kiện ở bên ngoài, giữa "yêu" và "ghét".

Tìm hiểu và tham gia Khóa học thiền Vipassana : https://www.facebook.com/358166407640832/posts/1382147028576093/

Nhưng nếu chúng ta tra xét rõ ràng qua phương pháp Vipassana, chúng ta sẽ khám phá ra rằng khi mà chúng ta có những phản ứng, chỉ là phản ứng theo sự cảm thọ của thân hoặc của tâm, liên kết với những dữ kiện bên ngoài. Một ý nghĩ xuất hiện, tức thì có sự cảm thọ của thân, thích hoặc không thích, rồi thì yêu và ghét. Đây là luật tự nhiên. Dần dần sự yêu thích và ghét bỏ được củng cố thêm và kế đến là tham đắm,si mê thêm bành trướng. Chúng ta bắt đầu có những gút thắt trong tâm mình. Chúng ta gieo đau khổ cho chính mình bằng cách luôn phản ứng theo cảm thọ nhất thời.

Với phương pháp Vipassana này, chúng ta tập cho tâm trí mình quan sát theo dõi những cảm thọ một cách bàng quan, không thiên vị, nghĩa là, không ham muốn khi có những trạng thái sung sướng, dễ chịu, và không ghét bỏ khi có trạng thái khó chịu, hay khổ. Một khi chúng ta có thực tập, chúng ta sẽ nghiệm ra rằng, cho dù cảm thọ vui hay khổ, chúng cũng sẽ đổi thay không ngừng. Tất cả đều là vô thường, không thật. Đây là luật tự nhiên của vũ trụ, dù là hữu tình hay vô tình.

Theo kinh nghiệm thực tập, một người sẽ hiểu rằng phương pháp này không phải chỉ để học cho biết một cách qua loa. Một khi mà chúng ta bắt đầu có sự chú tâm về những cảm thọ khác nhau, dù dễ chịu hay khó chịu, tư tưởng sẽ dần dần trở nên sáng suốt vì có sự chú tâm. Lúc này, hàng rào ngăn cách giữa ý thức và vô thức bị sụp đổ, và chúng ta không còn phản ứng một cách mù quáng nữa. Những tham đắm, si mê chôn sâu trong vô thức ví như một hỏa diệm sơn đang ngủ, chỉ chờ cơ hội là vùng dậy làm điêu đứng chúng ta.

Muốn được giải thoát khỏi những hỏa diệm sơn đang ngủ, ta chỉ có cách là làm theo Chánh pháp. Sự giải thoát không phải một sớm một chiều. Chúng ta phải kiên tâm, bền chí thực hành phương pháp Vipassana một cách đúng đắn. Khi mà bạn tiến trên đường thực tập, bạn sẽ tự nhận diện được những phiền não như: nóng giận, ganh ghét, tự ti, ngã mạn, của chính mình, và bạn sẽ biết quan sát chúng một cách bàng quan để mà loại bỏ chúng. Vipassana là phương pháp thanh lọc tư tưởng qua sự quan sát nơi tâm. Đây là phương pháp "tự kiểm thảo", tự loại bỏ những gì không trong sạch trong tâm hồn chúng ta. Phương thức này không có "sự tôn thờ một giáo chủ", chính bạn phải vạch sẵn đường đi của chính mình. Không ai có thể làm thế cho bạn được. Bạn không thể trở thành thiền sinh đúng nghĩa, nếu chỉ thực tập có mười ngày. Khóa học mười ngày chỉ là một khuôn mẫu hướng dẫn, cần được thực hành hàng ngày, và nếu được, nên tiếp tục học những khóa kế tiếp, để củng cố và tiến hơn trên bước đường tu tập. Chỉ có như vậy chúng ta mới gặt hái được những lợi ích đáng kể trong lúc hành thiền Vipassana. Có những khóa học hai mươi ngày, ba mươi ngày, hay bốn mươi lăm ngày để giúp thiền sinh vững chãi hơn trên bước đường thực tập. Thực hành kiên trì trong một thời gian, tâm trí ta sẽ từ từ thoát khỏi những tham đắm, giận hờn, si mê. Và từ đó, ta tìm được hạnh phúc, an lạc cho chính mình, và luôn cả những người chung quanh cũng được lợi ích.

1 note

·

View note

Text

第二天開示

放諸四海皆準之善與惡的定義~八正道:戒與定

第二天已過去了。雖然比第一天稍微好些,但許多困難還是存在。心是如此不安、焦躁、狂野,宛如一隻野牛或野象衝進了人住的地方,造成很大的破壞。如果有智慧的人馴服了這頭野獸,就能將所有傷害人類的力量轉變成服務社會及利益人類。同樣的,人心比起野象來,還要更有力,更可怕得多,必須經訓練馴服後才能充分發揮,為你所用。你必須很有耐心,堅毅、持續不斷地用功練習。持續不斷的練習是成功的秘訣。

修行,必須靠自己用功,沒有任何人可以代替你去完成。已開悟的人,以最大的愛心與慈悲心,解釋了這條修行之道,但他不能背著任何人走到終點目的地。因為在修行道上,每一步都必須靠自己走,自我奮鬥,以求解脫。一旦你開始修行,所有護持正法的力量,都會開始幫助你,不過每一個人仍要靠自己走完修行道上的每一步。

要明白你已經踏上的修行之道是什麼,佛陀用很簡單的話來解釋:

諸惡莫作(不做任何罪惡、不道德的行為),

眾善奉行(只做虔誠正當的行為),

自淨其意(淨化心),

是諸佛教(這是覺悟者共同的教導)。

這是不分種族、文化背景、國家,人人都能接受的普遍正道。當失去了法的真諦,人們對善惡之定義產生了歧見,它變成門戶之見的教派,每個宗派有自己對善惡的議論成見,以某種外在表現或執行某種儀式,或遵守某些信條來表示虔誠,這都是分宗分派的定義,只能讓部份人士接受,並非所有的人皆能信受。但是正法有著放諸四海皆準的善惡定義。任何行為,凡是傷害他人、干擾他人的平安和諧,就是罪惡不道德的行為;而任何幫助別人,給予別人安詳和諧的行為,都是虔敬正當的善行。這是沒有任何偏狹的派別之分,合乎自然法則的定義。依照自然的法則,一個人會去傷害他人,必定是先在自己內心產生了負面情緒─生氣、害怕、怨恨....等等,然後才在行為語言上做出有害他人的行動;而當一個人有不淨心念時,他自己也置身在苦惱不安的情況下。同樣的道理,一個人必定是先在心中生起了愛、慈悲、善意,才有助人的行為;而一旦心中生起這些純淨特質,當下就會感到內在的祥和平靜。你幫助他人,同時也幫助自己;你傷害他人,也同時傷害自己。這就是法(Dhamma)、真理、定律,亦即普遍性的自然的法則。

法的修行之道,稱為八正道(聖道),聖道意指任何人走上這條道路一定會成為一個高尚賢聖的人。八正道分為三部份:戒、定、慧。戒(sila)是道德規範-戒除不正當的舉止言語。定(samadhi)-發展主宰自己心念的正當行為。修行戒和定是有益的,但持戒與修定無法完全根除內心累積的不淨雜染。因此,必須修行法的第三部份:慧(pabba)-培養智慧、洞察力,完全地淨化內心。

八正道中戒的部份有三項:

(1) 正語(samma-vaca)-正當的語言,清淨的口語行為。為了要了解什麼是正當的語言,必需先明白什麼是不正當的語言。說謊來欺瞞別人,背後誹謗他人、造謠中傷、刺耳的話,傷害別人,惡毒誹謗,嘮嘮叨叨說廢話,全是不清淨的語言。戒除以上的不正當語言,剩下的就是正當的語言。

(2) 正業(samma-kammanta)-正當的行為,純淨的身體行為。這條修行的道路只有一種尺度來衡量行為的清淨與否,無論是身體、語言、或心理的行為,也就是它究竟有益他人或傷害他人。因此殺人、偷竊、強暴他人、不正當的淫慾、飲酒過量、酒後亂性等等的行為既傷人亦害己。戒除上面各種不正當的行為,剩下來就是正當行為。

(3) 正命(samma-ajiva)-正當的謀生之道。每個人都需要有辦法謀生,並維持家計。但若謀生方法會傷害他人,就不是正當的謀生之道。或許不是親自去做,而是鼓勵他人去做敗壞道德、墮落的行為,如販賣烈酒、經營賭場、販賣武器、買賣活生生的動物、或販賣肉類,以上皆是不正當的謀生方法。而即使你位高權重,但賺錢的動機不良,只是利用剝削他人,也是不正當的謀生之道。假如動機是服務人群,憑自己的能力,努力工作服務社會,換取維持自己及家人生活的合法報酬,這就是正當的謀生之道。

一般在家修行人,必須自給自足賺錢養家,但可能的危險是因賺錢而自我膨脹、自傲:為己盡量積聚財富,又輕視其他比較不會賺錢的人,這樣的態度傷害他人也傷害自己,因為自我愈膨脹,就愈與解脫背道而馳。因此正命的一個重要觀念是捐獻布施,以部份所得與他人分享。那麼,人賺錢不但是利益自己,也是利益他人。

如果正法僅止於勸誡避免去傷害他人,那起不了作用。在理智上不難了解做壞事的壞處與做好事的益處,或者因敬重宣導戒律的人而肯定其重要性。然而人們還是重覆犯錯,因為無法主宰自己的心。因此法的第二部份是定-增長主宰自心的能力。

八正道中定的部份有三項:

(4) 正精進(samma-vayama)-正當的努力,正當的修練。當你練習時,已發現心是如此軟弱不定,反覆無常,這樣的心需經由修練使它堅強起來。正精進有四個要領:

已生惡令斷滅(去除心中已有的種種不善)

未生惡令不生(閉絕任何不善的生起進入)

已生善令增長(任何心中已有的美德,保持並增長它)

未生善令生起(尚未有的某些美德,開發並培養它)

在練習觀呼吸(Anapana)時,你已開始實行以上的四個要領。

(5) 正念(samma-sati)-正確的覺知,覺知當下此刻的實相。關於過去只是記憶,關於將來只是期待、恐懼或想像。你透過持續對鼻孔附近,當下所顯現的實相保持覺知來練習正念。你必須培養覺知整體實相的能力,從最粗顯的層面到最微細的層面。開始時,你注意的是有意識的、刻意的呼吸,然後是自然輕柔的呼吸,再然後是呼吸的碰觸。接著你專注在更微細的層面,去觀察這限定的小範圍內的自然的、身體的感覺。你可能會體驗到呼吸的溫度,發現呼出的氣會比吸進的氣暖一些。除此之外,還有很多與呼吸無關的各種感受,如熱、冷、癢、脈動、振動、壓力、緊張、痛等等。你無法自己選擇感受,因為你不能創造感受。只要觀察,保持覺知;是什麼感受、如何命名形容並不重要,重要的是你覺知感受的真相,而不作任何習性反應。

你也察覺到心的舊習性,是一直在回憶過去與期盼未來中流轉,製造貪愛和瞋恨。藉修行正念,你開始戒除這舊習性。並不是上完課你就會忘記過去的一切,也不去計畫未來。事實上你習於浪費太多精力在無謂的思考過去與未來,結果當你真正需要記憶或計畫事情時,反而無能為力。經由培養正念,你會發現當你真的想要記起某件事,或對未來做最好的計畫時,變得十分容易。你將能過著健康快樂的生活。

(6) 正定(samma-samadhi)-專注並非這修行方法之目的;你所培養的專注必須基於心念純淨。心中有貪瞋痴時,雖可專注,但不是正定。必須覺知自身當下的實相,不起貪愛或瞋恨;持續不斷地時時刻刻保持這覺知,才是正定。

你謹慎遵守五戒,就是開始修戒。持續練習用心專注在這限定範圍內當下所呈現的實相,沒有貪愛或瞋恨,就是修定。現在繼續努力用功練習,讓你的心更敏銳,這樣當你開始修慧時,你就能貫穿深入到潛意識,根除過去深藏在那裡的不淨,而享受真正的快樂,解脫的快樂。

祝大家享有真正的快樂。

願一切眾生快樂!

0 notes

Text

The Pali word for mindfulness is Sati, which actually means activity and is also translated as awareness.

While reading many explanations of mindfulness, I came to realize that a better understanding of mindfulness requires a tremendous amount of reading and comprehension. Even some of the most scholarly Monks that have written essays on this subject often say that much of the understanding is beyond words.

So where does that leave the average person, like you and I, in terms of gaining a better understanding?

Anapana Sati, the meditation on in-and-out breathing, is the first subject of meditation expounded by the Buddha. Mindfulness of the breath.

I think this is highly relevant that it was Buddha’s first teaching on meditation, because all things begin and end with the breath. What better way to begin mindfulness, than with the breath!

Think about it. If you have no breath, then there is no thought, no feeling, no sensation, no desire, no clinging, no attachment.

And while I do think that complete comprehension of mindfulness goes far beyond mere words, I feel confident that the breath can lead us to that deeper understanding.

If we can train our minds to be constantly aware of this breath, we become more and more mindful of thoughts and feelings (physical and emotional) that arise and fall away.

This is my best attempt at writing a “Mindfulness for Dummies”. Being aware of the breath, and always returning to the breath.

We all know that we are constantly breathing, now all we have to do is pay attention to this.

Don’t try to breathe, don’t focus on inhaling or exhaling. Just be aware. Just breathe.

And may you always be well, happy and peaceful.

0 notes

Photo

Ho provato e.. tutto cambia🌿🌀 Arriva un momento nella vita in cui la prospettiva cambia, un giorno ti svegli e qualcosa in te è diverso. Vuoi renderti Consapevole in tutto ciò che fai; ma come puoi riuscirci? ✨ La Meditazione è un grande aiuto che può cambiare veramente la tua prospettiva. Hai mai sentito parlare di Anapana Sati ? ✨ È la Respirazione Meditativa. * Ana significa inspirazione e * Apana espirazione. Quindi come possiamo capire, è una meditazione basata sul TUO RESPIRO... Come fare? * Regalati un po’ di Tempo * Scegli un posto della tua casa dove mediterai * Srotola il tuo tappetino, o prendi un cuscino, (se sei principiante puoi avvicinarti ad una parete per sostenerti le prime volte) * Incrocia le tue gambe * Busto eretto * Chiudi i tuoi occhi per lasciarti andare Ora fai alcuni respiri profondi e poi, lascia fluire il tuo respiro in modo naturale, porta la tua attenzione all’ Inspiro e all’Espiro, lasciati semplicemente andare. Conoscevi questa Meditazione? Per Info Link in Bio🌿 Ph.📸 @giacomo_biancalani #yoga #furiosayoga #anukalanayoga #meditation #anapanasati #meditazione #om #yogini #mindfulness #mat #practiceyoga #happy #empoli #yogateachers #loyoganonsiferma #yogapose #yogaitalia #yogagirl (presso Firenze, Italy) https://www.instagram.com/p/CIA98ArLWL0/?igshid=17o9kdbo1jyy0

#yoga#furiosayoga#anukalanayoga#meditation#anapanasati#meditazione#om#yogini#mindfulness#mat#practiceyoga#happy#empoli#yogateachers#loyoganonsiferma#yogapose#yogaitalia#yogagirl

0 notes

Photo

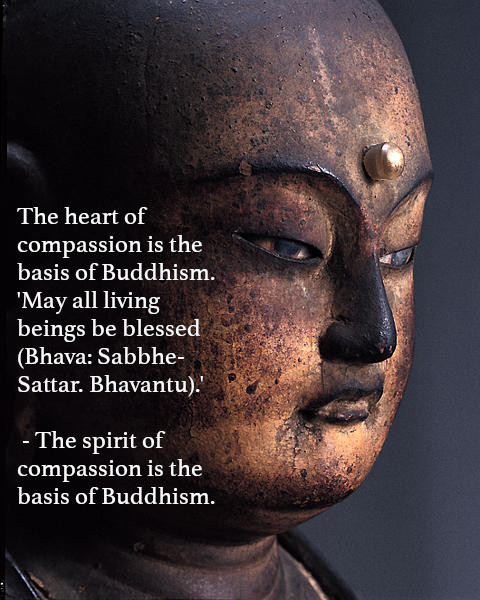

The Quest for Buddhism (114)

Buddhist cosmology

Anapanasati - "mindfulness of breathing"

Anapanasati (Skt.anapanasmrti), meaning "mindfulness of breathing" that "sati" means mindfulness; "anapana" refers to inhalation and exhalation, paying attention to the breath. It is a type of cessation (samatha meditation Ref) in which consciousness is calmed and focussed by being aware of the in-breath and out-breath (breath), or counting breath. In a broader sense, it moves from there to the observation of the body and includes the area of contemplation (vipassana meditation), which corresponds to the 4 presences of mindfulness (Pali: cattaro satipatthana), that is one of the seven sets of thirty-seven qualities (Ref2).

It is the quintessential form of Buddhist meditation, attributed to Gautama Buddha, and described in several suttas, most notably the Anapanasati Sutta.

Derivations of anapanasati are common to Tibetan, Zen, Tiantai and Theravada Buddhism as well as Western-based mindfulness programs.

仏教の探求 (114)

仏教の宇宙論

安那般那念〜「呼吸の心得」

安那般那念 (あんなはんなねん、巴: アーナーパーナ・サティ、梵: アーナーパーナ・スリムティ)とは、「呼吸の心得」を意味する、呼吸に注意を向ける瞑想法である。「サティ」は心得、「アーナーパーナ」は入出息 (呼吸)を意味する。息を吸ったり吐いたりすること(呼吸)を意識すること、または息を数えることによって意識を静め、集中させるサマタ瞑想 (止行:参照)の一種、ないしは導入的な一段階を意味するが、広義には、そこから身体の観察へと移行していき、四念処 (しねんじょ、巴:チャッターロー・サティパッターナー)に相当するヴィパッサナー瞑想 (観行)の領域も含む。四念処 (しねんじょ) とは、仏教における悟りのための4種の観想法の総称で、三十七道品(参照2)の中の1つ。

仏教の瞑想の真髄であり、ゴータマ・ブッダのものとされ、安般念経 (あんはんなねんきょう、巴: アーナーパーナ・サティ・スッタ) をはじめとするいくつかの経典に記述されている。

チベット仏教、禅宗、天台宗、上座部仏教、西洋のマインドフルネスプログラムに共通するのは、安那般那念 (あんなはんなねん、巴: アーナーパーナ・サティ) が由来している。

#anapanasati#mindfulness of breathing#samatha meditation#buddhism#vipassana meditation#buddha#forest mushrooms#mindfulness#nature#art

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anapana-sati - Nianaponika Thera

Anapana-sati – Nianaponika Thera

I seguenti appunti descrivono la tecnica di attenzione sulla respirazione “Anapana-sati”. Un metodo di meditazione relativamente semplice, ma prezioso e fondamentale. La loro lettura chiarirà alcuni tra i dubbi più frequenti e favorirà sicuramente la discussione. Tuttavia solo la pratica, regolare e ricorrente, ossia periodica, riuscirà a risolvere le questioni davvero concrete. Siffatto processo…

View On WordPress

#anapana sati#assorbimento#attenzione#buddhismo#calma#cammino#concentrazione#consapevolezza#essenza#meditare#meditazione#mente#Nianaponika Thera#postura#pratica#presenza#purificazione#respiro#samatha#spiritualità#tecniche#tranquillità#vipassana

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nghệ Thuật Sống – Chương 6. Tu tập định tâm

Chúng ta giữ giới (sila) để cố gắng kiểm soát lời nói và việc làm của mình. Tuy nhiên nguyên nhân của khổ đau lại nằm trong hành vi của ý. Chỉ riêng việc kiềm chế lời nói và việc làm sẽ vô ích nếu trong tâm ta vẫn tiếp tục sôi sục những ham muốn, ghét bỏ, những ý niệm bất thiện. Tự mình phân tán thân, khẩu, ý theo cách như thế, chúng ta sẽ không bao giờ hạnh phúc. Sớm muộn gì rồi tham lam và sân hận cũng sẽ bùng phát và chúng ta sẽ phạm giới, gây hại đến người khác và cho chính mình.

youtube

Về mặt tri thức, ta có thể hiểu rằng hành động bất thiện là sai trái. Nói cho cùng, mọi tôn giáo từ hàng ngàn năm qua đều thuyết giảng về tầm quan trọng của đạo đức. Nhưng khi những cám dỗ tìm đến thì tâm ý bị mất kiểm soát và người ta lại phạm giới. Một người nghiện ruợu biết rất rõ là không nên uống rượu vì ruợu gây hại cho anh ta, nhưng khi cơn thèm khát nổi lên anh ta vẫn uống rượu để rồi say khướt. Người đó không thể ngăn được chính mình vì anh ta không kiểm soát được tâm ý. Nhưng khi ta học được cách dừng lại những hành vi bất thiện của tâm ý thì việc kiềm chế những lời nói và việc làm bất thiện trở nên dễ dàng.

Vì bất ổn phát sinh từ tâm ý nên ta phải đương đầu với nó ở phương diện tinh thần. Để làm như vậy, ta phải thực hành bhāvanā, nghĩa đen là “phát triển tâm”, hay nói theo ngôn ngữ thông thường là thiền. Ngay từ thời Đức Phật ý nghĩa của từ bhāvanā đã trở thành mơ hồ khi sự hành thiền đi vào quên lãng.

Gần đây bhāvanā được dùng để chỉ bất cứ sự phát triển tinh thần hay sự thăng hoa tâm linh nào, và còn để chỉ ngay cả những hoạt động như đọc, nói, nghe, nghĩ về Dhamma. “Meditation” (thiền) là từ thông dụng nhất trong Anh ngữ dùng để phiên dịch chữ bhāvanā, thậm chí còn được dùng một cách phổ biến hơn để chỉ nhiều hoạt động, từ sự thư giãn tinh thần, quán tưởng và sự tự do kết hợp, cho đến sự tự kỷ ám thị.

Tất cả đều khác xa ý nghĩa mà Đức Phật muốn nói qua từ ngữ này. Ngài dùng bhāvanā để chỉ những cách tu tập tâm thức cụ thể, những kỹ thuật chính xác để quan sát tâm và thanh lọc tâm.

Bhāvanā gồm có hai phần tập luyện: định (samādhi), và tuệ (paññā). Tập định tâm còn được gọi là “phát triển an tĩnh” (samatha-bhāvanā), tu tuệ được gọi là “phát triển tuệ giác” (vipassana-bhāvanā). Sự thực hành bhāvanā bắt đầu với định, là phần thứ hai trong Bát Chánh Đạo. Đây là một cách tu tập thiện lành để kiểm soát các tiến trình của tâm, làm chủ tâm ý của chính mình.

Ba phần của Bát Chánh Đạo trong sự tu tập này là: chánh tinh tấn (nỗ lực chân chánh), chánh niệm (tâm chân chánh) và chánh định (định chân chánh).

Nỗ lực chân chánh (Chánh tinh tấn)

Nỗ lực chân chánh là bước đầu của sự thực tập bhāvanā. Tâm dễ bị sự vô minh chế ngự, cũng như dễ bị thèm muốn hay chán ghét chi phối. Bằng cách nào đó, chúng ta phải luyện tâm cho mạnh mẽ để nó trở nên vững vàng, ổn định, thành một công cụ hữu ích để nhìn nhận bản chất của chúng ta ở mức độ tinh tế nhất nhằm phát hiện và loại trừ nghiệp của mình.

Một bác sĩ muốn chẩn đoán bệnh của một bệnh nhân sẽ phải lấy mẫu máu và quan sát dưới kính hiển vi. Trước khi quan sát, ông phải chỉnh kính hiển vi hướng vào tiêu điểm thích hợp, rồi cố định vị trí tập trung này. Sáu đó ông mới có thể khảo sát mẫu máu và tìm ra nguyên nhân gây bệnh, rồi xác định phương cách trị liệu thích hợp để chữa khỏi bệnh. Cũng vậy, chúng ta phải học cách chú tâm, giữ tâm chuyên chú vào một đối tượng. Bằng cách này chúng ta biến tâm thành một công cụ để khảo sát thực tại tinh tế nhất của chính ta.

Đức Phật đã chỉ nhiều kỹ thuật để định tâm, mỗi cách thích hợp cho một hạng người tới gặp ngài để tu tập. Nhưng phương pháp thích hợp nhất để tìm hiểu thực tại nội tâm mà chính Ngài đã từng áp dụng là ānāpāna-sati, “ý thức về hơi thở.”

Hơi thở là một đối tượng chú tâm lúc nào cũng sẵn có cho mọi người, vì chúng ta ai cũng phải thở, từ khi chào đời cho đến khi chết. Nó là đối tượng thiền phổ quát được mọi người chấp nhận và dễ tiếp cận. Để tập bhāvanā, thiền giả ngồi trong một tư thế thoải mái, lưng thẳng, mắt nhắm. Thiền giả phải ở trong một căn phòng yên lặng, tránh bị phân tâm. Khi rời bỏ thế giới bên ngoài để quay vào với thế giới nội tâm, thiền giả thấy rằng hoạt động rõ ràng nhất là hơi thở; thiền giả chú tâm vào đối tượng này: hơi thở vào, ra qua lỗ mũi.

Đây không phải là một lối tập thở, mà là tập về ý thức. Ta không điều khiển hơi thở, nó ở trạng thái tự nhiên: hơi thở ngắn hay dài, nặng nề hay nhẹ nhàng. Ta chú tâm tâm vào hơi thở càng lâu càng tốt, đừng để bị xao lãng làm gián đoạn dòng ý thức.

Khi thực hành thiền, chúng ta sẽ thấy ngay việc làm được như trên thật khó biết chừng nào. Ngay khi ta vừa cố gắng chú tâm vào hơi thở, thì ta đã bắt đầu lo lắng vì chân đau. Khi ta vừa cố gắng đè nén được những ý nghĩ mông lung, thì tâm ta lại đầy ắp cả ngàn chuyện: nào là những kỷ niệm, những dự tính, những hy vọng hay sợ hãi. Tâm ta chú ý đến một trong những sự kiện này, và một lúc sau ta mới nhận biết ta đã quên bẵng đi hơi thở. Chúng ta lại cương quyết bắt đầu lại, và một lúc sau ta lại thấy tâm vuột đi mà không hay biết.

Ai là người làm chủ ở đây? Ngay khi ta mới thực tập thì ta đã thấy rõ rằng tâm ở ngoài vòng kiểm soát của ta. Tâm giống như một đứa bé được nuông chiều, vớ lấy một món đồ chơi, chơi chán rồi lại đổi hết món này đến món khác. Tâm không ngừng nhảy từ một ý nghĩ, một đối tượng của sự chú tâm sang cái khác, trốn chạy khỏi thực tại.

Đây là một thói quen đã ăn sâu vào tâm khảm và tâm ta đã hoạt động như vậy suốt cuộc đời. Nhưng khi ta bắt đầu nghiên cứu về bản tánh thực của mình, sự trốn chạy này phải được chấm dứt. Ta phải thay đổi thói quen của tâm và học cách sống với thực tại. Chúng ta bắt đầu bằng sự định tâm vào hơi thở. Khi thấy tâm lang thang thì ta kiên nhẫn và bình tĩnh kéo nó về với hơi thở. Nếu thất bại, ta lại cố gắng làm lại. Chúng ta tiếp tục lặp đi lặp lại sự luyện tập này một cách vui vẻ, không căng thẳng, không nản lòng. Dầu sao thì thói quen của cả đời không thể thay đổi trong một vài phút. Công việc đòi hỏi sự thực hành liên tục, nhiều lần và cần sự nhẫn nại, bình tĩnh. Đây là phương cách phát triển ý thức về thực tại. Đây là nỗ lực chân chánh.

Đức Phật nêu ra bốn loại nỗ lực chân chánh:

Ngăn không để cho điều xấu ác, bất thiện khởi sinh; Từ bỏ những điều xấu ác nếu đã khởi sinh;

Phát khởi những điều hiền thiện chưa có;

Duy trì những điều hiền thiện không xao lãng, làm chúng phát triển và đạt đến sự hoàn thiện.1 A.IV.ii . 3 (13), Padhana Sutta

Do thực hành ý thức về hơi thở, chúng ta đã thực hành cả bốn nỗ lực chân chánh như trên. Chúng ta ngồi xuống và chú tâm vào hơi thở, không để cho các ý nghĩ xen vào. Làm như vậy chúng ta khởi xướng và duy trì được trạng thái hiền thiện của sự tự ý thức. Chúng ta giữ cho chính mình không bị rơi vào xao lãng, đãng trí hay mất dấu thực tại. Nếu một ý nghĩ xuất hiện, ta không đuổi theo nó mà đưa sự chú ý quay về với hơi thở. Bằng cách này, chúng ta phát triển khả năng chú tâm vào một đối tượng và chống lại sự phân tâm: hai phẩm tính thiết yếu của định.

Ý thức chân chánh (Chánh niệm)

Quan sát hơi thở cũng là một cách thực hành ý thức chân chánh. Chúng ta khổ là do vô minh. Chúng ta phản ứng vì không biết mình đang làm gì và vì không biết rõ thực tại của mình. Tâm ta mất nhiều thì giờ vào những mơ mộng, ảo tưởng, làm sống lại những kinh nghiệm thích thú hay khó chịu và dự tính tương lai một cách sợ hãi hay hăng say. Trong khi đắm chìm trong thèm muốn hay chán ghét, chúng ta không ý thức được những gì hiện đang xảy ra, cũng như không biết mình đang làm gì. Thực ra thì giây phút này, hiện tại mới thực sự quan trọng nhất đối với chúng ta. Chúng ta không thể sống trong quá khứ, nó đã qua. Chúng ta không thể sống trong tương lai, vì nó ở ngoài tầm tay. Chúng ta chỉ có thể sống ở hiện tại.

Nếu chúng ta không ý thức về những hành động của mình trong hiện tại, chúng ta không tránh khỏi việc tái phạm những lỗi lầm trong quá khứ và không bao giờ có thể đạt được những ước muốn cho tương lai. Nhưng nếu có thể phát triển khả năng ý thức được hiện tại, chúng ta có thể dùng quá khứ như một hướng dẫn cho những hành động của mình trong tương lai, như vậy chúng ta có thể đạt được mục đích.

Dhamma là con đường của bây giờ và ngay tại đây. Bởi vậy chúng ta phải phát triển khả năng ý thức được giây phút hiện tại. Chúng ta cần một phương pháp để chú tâm vào thực tại ngay lúc này. Kỹ thuật anapana-sati (ý thức về hơi thở) chính là phương pháp này. Thực hành phương pháp này sẽ phát triển sự ý thức về chính mình ngay tại đây và ngay bây giờ: Ngay lúc này thở vào, ngay lúc này thở ra. Do thực hành ý thức về hơi thở, chúng ta nhận biết được thực tại.

Một lý do nữa để phát triển ý thức về hơi thở là vì chúng ta muốn thể nghiệm về chân lí tối hậu. Chú tâm vào hơi thở có thể giúp ta khám phá được những gì mà chúng ta không hề biết về bản thân, để mang những gì ở vô thức lên ý thức. Nó như một nhịp cầu nối liền vô thức và ý thức, hơi thở hoạt động cả ở vô thức lẫn ý thức. Chúng ta có thể thở theo một lối đặc biệt, có thể điều khiển hơi thở. Chúng ta cũng có thể ngưng hơi thở một lúc. Tuy nhiên khi chúng ta ngưng điều khiển thì hơi thở vẫn tiếp tục hoạt động như thường.

Ví dụ, chúng ta có thể cố ý thở hơi mạnh một chút để ta có thể chú tâm được một cách dễ dàng. Ngay khi ý thức về hơi thở đã rõ ràng và vững rồi, thì ta để cho hơi thở tự nhiên, dù là mạnh hay nhẹ, sâu hay nông, ngắn hay dài, nhanh hay chậm. Chúng ta không làm một cố gắng nào để điều khiển hơi thở, ta chỉ cố gắng ý thức về nó mà thôi. Bằng cách duy trì được ý thức về hơi thở tự nhiên, chúng ta bắt đầu quan sát hoạt động tự động của cơ thể, một hoạt động thường là không cố ý. Từ sự quan sát thực tế thô thiển của hơi thở cố ý, chúng ta tiến đến sự quan sát sự thật tinh tế hơn của hơi thở tự nhiên. Chúng ta đã bắt đầu vượt ra ngoài thực tế bề ngoài đến sự ý thức về thực tế tinh tế hơn.

Một lý do nữa để phát triển sự ý thức về hơi thở là để thoát khỏi tham, sân, si (thèm muốn, chán ghét, vô minh), trước hết ta phải ý thức về chúng. Trong công việc này, hơi thở sẽ giúp chúng ta, vì hơi thở là phản ánh tâm trạng của ta. Khi tâm ta bình an và yên tĩnh thì hơi thở ta điều hòa và nhẹ nhàng. Nhưng khi bất tịnh nảy sinh trong tâm như giận dữ, hận thù, sợ hãi hay u mê thì hơi thở trở nên thô thiển, nặng nề và gấp rút. Nhờ vậy, hơi thở đã báo động cho chúng ta biết về trạng thái của tâm và cho phép chúng ta bắt đầu đối phó với nó.

Còn một lý do nữa để chúng ta thực hành sự ý thức về hơi thở. Vì mục đích của chúng ta là làm sao để tâm thoát khỏi những bất tịnh, nên chúng ta phải cẩn thận để mỗi bước tiến đến đích phải thanh tịnh và thiện lành. Ngay trong giai đoạn đầu để phát triển samadhi (định), chúng ta phải dùng một đối tượng quan sát thiện lành. Hơi thở là đối tượng này. Chúng ta không thể có ham muốn và ghét bỏ đối với hơi th��, và vì hơi thở là một thực tế, hoàn toàn thoát khỏi ảo tưởng, ảo giác. Do đó hơi thở là một đối tượng thích hợp cho sự chú tâm.

Giây phút khi hoàn toàn chú tâm vào hơi thở thì tâm thoát khỏi thèm muốn, chán ghét, vô minh. Dù thời gian thanh tịnh này có ngắn ngủi đến đâu thì nó cũng có một năng lực rất mạnh vì nó thách thức tất cả những dữ kiện quá khứ của ta. Tất cả những nghiệp tích lũy này bị khuấy động và bắt đầu xuất hiện như những khó khăn về thân cũng như về tâm. Những khó khăn này làm cản trở nỗ lực phát triển ý thức. Chúng ta có thể thấy nóng lòng muốn tiến bộ, hay tức giận, chán nản vì sự tiến bộ có vẻ chậm chạp, đấy là một hình thức của thèm muốn và chán ghét.

Đôi khi vừa ngồi xuống thiền ta đã bị trạng thái hôn mê áp đảo và ta ngủ thiếp đi. Có lúc ta thấy bồn chồn đến nỗi đứng ngồi không yên hay tìm cớ để khỏi thiền. Nhiều lúc nghi ngờ gặm nhấm ý chí hành thiền – sự nghi ngờ quá độ, vô lý về người thầy, về giáo huấn, hay về khả năng hành thiền của chính mình. Khi đột nhiên phải đối diện với những khó khăn đó, chúng ta có thể nghĩ đến bỏ thiền cho xong chuyện.

Vào những lúc như vậy chúng ta phải hiểu rằng, những trở ngại này khởi lên chỉ là phản ứng đối với sự thành công của chúng ta trong việc thực tập ý thức về hơi thở. Nếu chúng ta kiên trì thì chúng sẽ dần dần biến mất. Lúc đó sự hành thiền của chúng ta trở nên dễ dàng hơn, vì ngay trong giai đoạn khởi đầu này một vài tầng lớp của nghiệp cũ đã bị xóa bỏ khỏi bề mặt của tâm. Như vậy, ngay khi ta mới chỉ tập ý thức về hơi thở, chúng ta đã bắt đầu thanh lọc tâm và tiến đến gần hơn với sự giải thoát.

Định chân chánh (Chánh định)

Chú tâm vào hơi thở phát triển sự ý thức về giây phút hiện tại. Duy trì sự ý thức này từng giây từng phút, càng lâu càng tốt, là định chân chánh.

Trong đời sống bình thường, những hoạt động hằng ngày cũng đòi hỏi sự chú ý, nhưng không nhất thiết là định chân chánh. Một người có thể chú hết tâm vào việc thỏa mãn những khoái cảm hay trì hoãn những mối lo sợ. Một con mèo chăm chú rình hang chuột, sẵn sàng để vồ khi chuột xuất hiện. Một tên móc túi chăm chú rình bóp của nạn nhân, chỉ chờ cơ hội tốt để chộp lấy. Một đứa bé trong đêm tối nằm trên giường nhìn trân trân kinh hãi vào một góc buồng, tưởng tượng ra những con quái vật đang ẩn núp trong bóng tối. Tất cả những sự chú ý này không phải là định chân chánh, loại định có thể đưa ta đến giải thoát. Samadhi (định) phải có sự chú tâm vào một đối tượng hoàn toàn thoát khỏi ham muốn, ghét bỏ và vô minh.

Khi thực hành ý thức về hơi thở, ta thấy việc duy trì được sự ý thức không gián đoạn quả là một việc khó khăn. Mặc dù ta đã cương quyết chú tâm vào hơi thở, nhưng nó vẫn vuột đi mà ta không hề hay biết. Chúng ta thấy mình như một người say ruợu, cố gắng đi cho thẳng nhưng vẫn bước xiên xẹo. Sự thật thì chúng ta đã say vì vô minh và ảo giác, do đó chúng ta cứ tiếp tục đi lạc vào quá khứ, tương lai, hay thèm muốn, chán ghét. Chúng ta không thể nào ở yên trên con đường thẳng để giữ vững sự ý thức.

Là người hành thiền, điều tốt cho chúng ta là không nên chán nản hay thối chí khi phải đối diện với những khó khăn này. Ngược lại, ta phải hiểu rằng cần có thời gian để thay đổi những thói quen đã ăn sâu trong tâm thức tự bao nhiêu năm nay. Muốn có kết quả, chúng ta chỉ có cách kiên trì tập luyện, tập nhiều lần, liên tục, kiên nhẫn và bền bỉ. Công việc chính của chúng ta là khi tâm đi lang thang thì ta lại kéo nó về lại với hơi thở. Nếu làm được như vậy, thì chúng ta đã tiến được một bước quan trọng trong việc sửa đổi cái tâm hay đi lang thang. Và bằng cách tập đi tập lại, ta có thể kéo sự chú tâm trở lại ngày một nhanh chóng hơn. Dần dần khoảng thời gian xao lãng càng lúc càng ngắn đi và khoảng thời gian có ý thức càng lâu hơn.

Khi sự chú tâm đã vững mạnh, chúng ta cảm thấy thoải mái, sung sướng, tràn đầy nhựa sống. Dần dần hơi thở thay đổi, nó trở nên êm, đều, nhẹ và nông. Có lúc hình như hơi thở đã ngưng hẳn. Thật ra, tâm ta đã trở nên an tĩnh, cơ thể cũng trở nên yên tĩnh và sự biến dưỡng giảm đi, vì vậy chỉ cần ít dưỡng khí.

Trong giai đoạn này, nhiều người có thể có những kinh nghiệm bất thường như thấy ánh sáng hay ảo ảnh trong khi ngồi nhắm mắt, hay nghe thấy những âm thanh khác thường. Tất cả những kinh nghiệm siêu nhiên ấy là dấu hiệu cho biết tâm đã định ở một mức độ cao. Những hiện tượng này tự chúng không có một tầm quan trọng nào và chúng ta không nên để tâm đến chúng. Đối tượng của sự ý thức vẫn là hơi thở. Ngoài nó ra còn có những điều khác đều làm ta phân tâm. Chúng ta cũng không nên mong muốn có những kinh nghiệm này; chúng xuất hiện với người này, và có thể không xuất hiện với người khác. Tất cả những kinh nghiệm khác thường này chỉ là những cột mốc ghi dấu sự tiến triển trên con đường. Đôi khi những cột mốc này bị che lấp làm ta không thấy được, hay có thể ta mải mê trên con đường đến nỗi ta vượt qua mà không nhận thấy chúng. Nếu chúng ta lấy những cột mốc đó làm đích mà bám vào thì chúng ta không còn tiến bộ nữa. Thật ra có vô số những cảm giác bất thường để trải nghiệm. Những ai thực hành Dhamma không nên tìm kiếm những kinh nghiệm đó mà phải có tuệ giác về bản tánh của chính mình để có thể giải thoát khỏi khổ đau.

Vì vậy chúng ta tiếp tục chỉ chú tâm vào hơi thở. Khi tâm càng định thì hơi thở càng nhẹ nhàng hơn, và sự theo dõi càng trở nên khó khăn hơn nên ta cần phải cố gắng nhiều hơn để duy trì sự ý thức. Bằng cách này, chúng ta tiếp tục luyện tâm, làm cho sự định tâm được bén nhạy và biến nó thành một dụng cụ để thâm nhập thực tế bề ngoài để quan sát thực tế vi tế nhất ở bên trong.

Có nhiều kỹ thuật khác để phát triển sự định tâm. Hành giả có thể được dạy chú tâm vào một tiếng bằng cách tụng niệm tiếng đó, hay vào một hình ảnh, hay làm đi làm lại một động tác. Làm như vậy hành giả hòa nhập vào đối tượng của sự chú tâm, và đạt được trạng thái xuất thần. Hành giả cảm thấy lâng lâng dễ chịu, nhưng khi trạng thái đó không còn nữa, người đó lại trở về với đời sống bình thường với những khó khăn như trước. Những kỹ thuật này tạo nên một lớp bình an và an lạc ở bề mặt của tâm, nhưng không tới được những bất tịnh ở tầng lớp sâu bên dưới. Những đối tượng chú tâm được dùng trong những kỹ thuật này không liên quan gì với thực tại của hành giả. Trạng thái ngây ngất, sảng khoái mà hành giả có được là giả tạo, chứ không nảy sinh một cách tự nhiên từ đáy sâu của tâm đã thanh tịnh. Samadhi chân chánh không thể là cơn say tâm linh. Nó phải thoát khỏi mọi sự giả tạo và ảo tưởng.

Ngay trong giáo huấn của Đức Phật cũng có nhiều trạng thái xuất thần, nhập định – jhana – có thể đạt được. Chính Ngài đã được dạy tám tầng thiền định trước khi giác ngộ và Ngài tiếp tục luyện tập chúng suốt đời. Tuy nhiên những trạng thái nhập định này không thể giúp Ngài được giải thoát. Bởi vậy, khi Ngài dạy về những trạng thái này, Ngài đã nhấn mạnh công dụng của chúng chỉ như những viên đá lót đường đưa tới sự phát triển tuệ giác. Hành giả phát triển khả năng định không phải để kinh nghiệm trạng thái cực lạc hay ngất ngây, mà là để rèn luyện tâm thành một dụng cụ để quan sát thực tế của chính mình và loại bỏ những điều kiện (nghiệp) đã gây nên khổ. Đó chính là định chân chánh.

#Goenka #Vipassana #nghethuatsong #tutapdinhtam #phapbao

Theo nguồn: https://phapbao.net/nghe-thuat-song-c...

0 notes

Photo

Harnessing Your Own Innate Powers Fancy calming your mind, healing your internal organs, channeling chi into your bones and building an immortal energy body, by using nothing more than your attention and a basic skill you were born with? These are but a few of the numerous holistic health benefits available to us all. A dear friend of mine’s Grandmother was fond of saying “ten deep breaths will cure anything”. It is only much later in life that I began to understand the profundity of these carefully chosen words. Of all the processes we entertain in our busy lives, our breath seldom garners the attention it deserves. To some extent, we may be forgiven for taking this vital life-supporting process for granted. The very fact that it carries on, without too much effort on our part, may be precisely the reason its healing potential remains largely concealed. Fortunately, the subtle connection between our awareness and breath has been understood, and shared, by the masters of many martial and spiritual traditions throughout time. Universal Life Force There is also a common understanding and acceptance among these ancient traditions that we exist in, and are connected to, an all-encompassing energy field. This life force wears many labels. In the Taoist traditions of the East, it is known as ‘Qi’ or ‘Chi’. In Japan, it takes the name ‘Ki’. In Indic yoga traditions it is called ‘Prana’ and in Hawaii, it is ‘Mana’. Irrespective of which tradition you follow, when it comes to increasing this life force within, the practice of bringing focused awareness to your breath is common to all. Strengthening Your Bones Qigong masters have long known that this life force flows at five different levels; the skin, the flesh, the meridians, the organs, and the bones. Taoists understood the concept of the skeleton as a dynamic energy structure that can be maintained in optimum shape, and that the natural process of decay can be prevented. An adept of this path will practice techniques at the various levels to strengthen their ‘Qi’. It is their awareness of the subtle breath, the “breath that penetrates through every pore in the skin” that is then “guided through the bone marrow with their attention” that strengthens their energy bodies. This simple action activates a very powerful law of energy work that states that any place in our bodies we place our attention, a flow of energy is generated in that direction. If we were to move our attention from the tip of our index finger to our wrist, over and over again, warmth, tingling, heaviness or subtle vibration of the finger may be experienced. From the finger, the practice may be continued to the rest of the fingers and gradually up the arms, up the legs and the rest of the skeleton. [1] Alt text hereLife force flows even through our bones, and focusing our breath here can prevent decay. A very common and major goal of most Taoists is to achieve longevity and immortality, rather than enter the regular afterlife. The twofold approach includes outer alchemy and inner alchemy. Generally speaking, outer alchemy strengthens the physical body using moving meditation and various herbal formulas. Inner alchemy strengthens the energetic body with still meditation and cultivating chi. Although different, these two approaches are usually used together to complement each other, eventually resulting in self-cultivation. In Taoism, one’s soul or energy is intertwined with the vital energy, which is what nourishes your soul. Ridding the body of impurities can increase this energy, as does leading an upright, moral and benevolent life. Internal alchemy includes sophisticated visualization, strict dieting, specific sexual exercises, and self-control. The many different types of meditation all revolved around the common idea of breathing. Much of a Taoist’s time is spent meditating. A popular rule of thumb for breathing techniques include holding one’s breath for 12 heartbeats, better known as a ‘little tour’; 420 heartbeats is the ‘grand tour’, and the most prominent achievement in breathing is holding one’s breath for 1000 heartbeats.[2] The Buddhist meditative practice of Anapana Sati occurs at the confluence of our awareness and our breath. Through continually returning one’s attention to the breath, the practitioner is ushered towards a state of inner peace, releasing mental and physical tension. The Vipassana yogic tradition combines this awareness of subtle breath and bodily sensation with objective observation, from one moment to the next. The aforementioned Anapana meditation is to develop concentration, and Vipassana meditation to develop wisdom. Vipassana meditation involves really paying attention to whatever is happening to you in the present moment (sensations in your body, emotions, thoughts) with equanimity. Equanimity is the peace that comes from the power of observing; the ability to see, without being caught up in what we see. The Buddha described a mind filled with equanimity as ‘abundant, exalted, immeasurable, without hostility, and without ill-will’ Breath is life force, and it holds far more power than we realize. In the Pali language, native to the Indian sub-continent, the most common word translated as ‘equanimity’ is Upekkha, meaning ‘to look over’. Upekkha can also refer to the ease that comes from seeing a bigger picture. Colloquially, in India, the word was sometimes used to mean ‘to see with patience’ or ‘seeing with understanding’. By increasing both their awareness and their equanimity, the adept gain greater insight into their reality. The yogic practice of Pranayama, according to Swami Sivananda’s teachings, is the perfect control of the life-currents through control of breath, and is the process by which we understand the secret of Prana, and manipulate it. One who has grasped this Prana has grasped the very core of cosmic life and activity. Breath is a physical aspect, or external manifestation of Prana – the vital force, and thus Pranayama begins with the regulation of the breath. The yogi stores a great deal of Prana through the regular practice of Pranayama”[3] If building an immortal energy body or holding your breath for a thousand heartbeats seem a bit ambitious, start by closing your eyes and take a deep breath…actually take ten, and you might just feel much better for it. Author unknown

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Je peux vous donner un #mantra si vous le souhaitez.

Le shintoïsme est différent du bouddhisme. Le shintoïsme est basée sur l'animisme que tout a des phases de dieux. Ainsi, nous pouvons voir la spiritualité dans les montagnes, les rivières, voit, ciel, sable, bois, etc Le Japon a de nombreuses catastrophes:. Typhons, tremblements de terre, éruptions volcaniques, chutes de neige abondantes, etc, donc nous craignent naturellement énorme puissance de la nature. Il a été fait de nous de respecter la nature. Et il a été influencé par le taoïsme un peu. Il n'y avait aucune doctrine dans le shintoïsme, j'aime Shinto car il est très simple et il nous apprend à être humble de la nature.

Le bouddhisme est la manière la façon de surmonter la «douleur» que nous avons la douleur de la vie, la douleur du vieillissement, douleur de la maladie, de la douleur de la mort, etc Seul le Bouddha Gautama atteint à l'illumination par de profondes méditations, première étape consiste à compter le souffle. Et nous devons garder règles du bouddhisme; ne pas tuer, ne pas mentir, ne pas voler, etc

Il existe de nombreuses sectes du bouddhisme au Japon, mais plus de 90% d'entre eux sont Mahayana Vajrayana ou (près de bouddhisme tibétain ou une hindouisme). Vajrayana est la secte de ma famille, donc je pratique cet enseignement et Kundalini Yoga quand j'étais jeune. Je peux vous donner un mantra si vous le souhaitez.

Et il ya une autre secte du bouddhisme: Teravada qui est principalement cru dans les pays sud asiatiques: la Birmanie, la Thaïlande, le Sri Lanka, le Cambodge, etc Je crois Teravada est très proche de l'original d'enseignement de Bouddha. Ils pratiquent anapana sati qui observe le souffle de différentes manières.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Homage to the Blessed One,

Accomplished and Fully Enlightened

Ven. Mahathera Nauyane Ariyadhamma

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to Practice Samatha Meditation – by Mahasi Sayadaw

Samatha Meditation - THE METHOD IN BRIEF (BY MAHASI SAYADAW)

The samatha meditation comprises (40) sorts. They are as enumerated below:

1. Kasina (10)

2. Asubha (10)

3. Anussati (10)

4. Brahmavihara (4)

5. Aruppa (4)

6. Ahare Patikkulasanna (1)

7. Catu-dhatu-vavatthana (1)

THE TEN SORTS OF KASINA ARE:

1. Earth kasina (pathavikasinam)

2. Water kasina (apokasinam)

3. Fire kasina (tejokasinam)

4. Wind kasina (Vayokasinam)

5. Brownish or deep purplish blue kasina (nilakasinam)

6. Yellow kasina (pitakasinam)

7. Red kasina (lohitakasinam)

8. White kasina (odatakasinam)

9. Light kasina (alokakasinam)

10. Open air-space, sky kasina (akasakasinam)

THE TEN ASUBHAS ARE AS FOLLOWS:

1. Swollen or bloated corpse. (uddhumatakam)

2. A corpse brownish black or purplish blue with decay (vinilakam)

3. A festering or suppurated corpse (vipubbakam)

4. A corpse splattered half or fissured from decay. (vicchiddakam)

5. A corpse gnawed by animals such as wild dogs and foxes: (vikkhayittakam)

6. A corpse scattered in parts, hands, legs,

head and body being dispersed (vikkhitakam)

7. A corpse cut and thrown away in parts after killing. (hatavikkhittakam)

8. A bleeding corpse, i.e. with red blood oozing out. (lohitakam)

9. A corpse infested with and eaten by worms. (puluvakam)

10. Remains of a corpse in a heap of bones, i.e. skeleton. (atthikam)

THE TEN ANUSSATIS ARE:

1. Fixing the mind with attentiveness and reflecting repeatedly on the glorious virtues and attributes of Buddha. (Buddhanussati)

2. Reflecting with serious attentiveness repeatedly on the virtues and qualities of Buddha’s teachings and his doctrine. (Dhammanussati)

3. Fixing the mind strongly and repeatedly upon the rare attributes and sanctity of the Sanghas (Sanghanussati)

4. Reflecting seriously and repeatedly on the purification of one’s own morality or sila. (Silanussati)

5. Repeatedly reflecting on the mind’s purity in the noble act of one’s own dana, charitableness and liberality. (Caganussati)

6. Reflecting with serious and repeated attention on one’s own complete possession of the qualities of saddha. absolute faith, sila, morality, suta; knowledge, caga, liberality and panna, wisdom or knowledge just as the devas have, to enable one to be reborn in the World of devas. (Devatanussati)

7. Reflecting repeatedly with serious attentiveness on the supreme spiritual blissful state of Nirvana. (Upasamanussati)

8. Recollection of death or reflecting repeatedly on the inevitability of death. (Marananussati)

9. Reflecting earnestly and repeatedly on the impurity of the body which is composed of the detestable 32 constituents such as hair, body hair, nails, teeth, skin, etc. (Kayagata-sati)

10. Repeated reflection on the inhaled and exhaled breath. (Anapana-sati)

THE FOUR BRAHMAVIHARAS ARE:

1. Contemplation of loving kindness and goodwill or universal benevolence towards all sentient beings, praying “may all beings be happy.” (Metta)

2. Contemplation, of compassion, i.e. pity for and sympathy with those who are suffering praying in mind that “may all beings be free from misery and suffering.” (Karuna)

3. Contemplation of feeling rejoicing with others in their happiness or prosperity praying in mind that they “may continue to be happy and prosperous as at present with out diminution. (Mudita)

4. To remain indifferent with a feeling of equanimity to the state of condition of all beings, bearing an impartial attitude that things happen according to one’s own kamma that has been committed. (Upekkha)

THE FOUR ARUPPAS ARE:

1. Meditation or fixing the mind intently on the realm of infinity of space, sky pannata. (Akasanañcayatanam)

2. Meditation or fixing the mind intently on the realm of infinity of consciousness, pathama ruppavinnana. (Viññanañcayatanam)

3. Meditation or dwelling the mind intently on Nothingness, i.e. nothingness, that remains or exists from pathamaruppavinnana. (Akincannayatanam)

4. Meditation on the realm of Neither-perception nor Non-perception, i.e. semi-conscious state Jhana’s perception Tatiya (third) ruppavinnana as "so calm, tranquil and gentle.” (Nevasañña-nasaññayatanam) Ahare patikulasañña: means the consciousness or perception of the impurity of material food derived from fixing the mind intently on the food and eatables as being detestable. Catudhatuvavatthanam: means contemplation on the existence or composition of the main four elements of dhatu in the body, namely, vayo (air or wind) and their differences in nature.

Ahare patikulasañña: means the consciousness or perception of the impurity of material food derived from fixing the mind intently on the food and eatables as being detestable.

Catudhatuvavatthanam: means contemplation on the existence or composition of the main four elements of dhatu in the body, namely, vayo (air or wind) and their differences in nature.

KASINA

A person who, of the forty sorts of samatha meditation, chooses the pathavi kasina as his subject of contemplation, should fix his eyes upon a spot of earth on the ground or a circle of earthdevice and contemplate mentally noting ‘pathavi, pathavi,’ or 'earth, earth, earth.’ After repeated contemplation for a considerable time, the vivid image or nimitta of the earth-device will appear in the mind when the eyes are closed as clearly as when they are open.

This appearance of mental image is called “Uggaha, nimitta” (acquired image). If this “nimitta” becomes fixed and steady in the mind, he can go to any place and take up a posture of either sitting, walking, standing or lying. He should then continue to contemplate on the “Uggahanimitta” by saying mentally 'pathavi, pathavi,’ or 'earth, earth.’ While thus contemplating, it may happen that the mind does not remain fixed on its object and is likely to wander to other objects in the following manner.

1. The mind may think of desirable or agreeable objects according to its own inclination. This is called “Kamacchanda. nivarana” (sensuous lust).

2. The mind may also dwell on thoughts of despair and anger. This is called “Vyapadanivarana” (ill-will).

3. Slackness in contemplation may take place and the mind becomes dull and foggy. This is “Thina-middha-nivarana” (sloth and torpor).

4. The mind may become unstable and fleeting or restless, and then recollecting the past misdeeds in speech and bodily action, is likely to become worried. These are known as “Uddhaccakukkucca-nivarana” (restlessness and worry).

5. Thoughts may arise 'whether the contemplation which is being undertaken is a right method, or whether it is capable of bringing beneficial results, or whether there is any chance to achieve any good result’s. This is “Vicikiccha-nivarana” (sceptical doubt).

When these five “Nivaranas” (Hindrances) appear, they should be discarded and rejected as they occur, and the mind should be immediately brought back to the original object of “Uggahanimitta” letting it dwell constantly on it, noting mentally as 'pathavi, pathavi.’ If the kasina object of “Uggaha-nimitta” disappears from the mind, one should go back to the place where the earth-device is kept and contemplate again: 'pathavi, pathavi’ by fixing the eyes on the device till “Uggahanimitta” is formed again in the mind’s eye.

Thereafter, one should return to the desired place and proceed with the contemplation as before in any posture of sitting, standing, lying and walking. Carrying on thus the contemplation of the object of “Uggaha-nimitta” repeatedly for a long time, the object assumes a very brilliant and crystalline appearance quite unlike that of the original. This is called “Patibhaga-nimitta” (counterpart-image). At the time the mind is free from all 'Nivaranas.’ It dwells fixedly on the “patibhaga-nimitta.” This state of mind is known as “Upacarasamadhi” (proximate concentration). Now, by continually fixing the mind with this “Upacarasamadhi” on the 'Patibhaga- nimitta,’ the mind reaches a state as if it were alive and sinks consciously into the object and remains fixed in it. This state of fixedness and stability of mind is known as “Appana-samadhi” (ecstatic concentration).

The Appana-samadhi is of four kinds, viz:

(a) the first Jhana

(b) the second Jhana

© the third Jhana

(d) the fourth Jhana

(a) In the first Jhana five distinct constituents are present; they are:

(1) Vitakka (initial reflection)

(2) Vicara (sustained investigation)

(3) Piti (rapture or ecstasy)

(4) Sukha (happiness or delight)

(5) Ekaggata (Tranquility of mind on one object with one pointedness.)

(b) One who has already attained the stage of first Jhana, seeing unsatisfactoriness in the first two constituents of 'Vitakka’ and 'Vicara’ again proceeds with the contemplation to overcome them and succeeds in attaining the stage of second Jhana where the three distinct constituents of 'Piti,’ 'Sukha’ and 'Ekaggata’ are obvious.

© Again seeing unsatisfactoriness 'in Piti,’ if he proceeds with the contemplation to overcome it and divests himself of ecstasy, he will attain the third Jhana which is a state of tranquil serenity and where the two distinct constituents of 'Sukha’ and 'Ekaggata,’ remains obvious.

(d) Again seeing unsatisfactoriness in 'Sukha’ he proceeds with the contemplation to overcome it. By doing so, he attains the stage of fourth Jhana in which the mind exalted and purified is indifferent to all emotions alike of pleasure and of pain. At this stage the two constituents of 'Upekkha’-(equanimity) and 'Ekaggata’ become manifested.

This is, in brief, the description of the manner of contemplation of the “Pathavi-kasina” and the development of the stages of four Jhanas. The same applies to the remaining kasinas.

ASUBHA

In the case of a person who wishes to practise 'Asubha’ meditation objects, he should fix his eyes on a bloated corpse, or a livid corpse, etc., and contemplate by saying mentally 'bloated corpse, bloated corpse,’ livid corpse, livid corpse, etc. This contemplation is similar to that of 'Pathavikasina,’ the fundamental difference being that the contemplation of these 'Asubha’ subjects will lead to the stage of First jhana.

ANUSSATI

Amongst the ten Anussatis, the contemplation of the impure 32 parts of the body (kayagatasati- kamma tthana) will also lead to the stage of First jhana. The eight reflections (Anussati) consisting of the subjects from “Buddhanussati” to “Marananussati”; reflection on the loathsomeness of food (Ahare patikulasañña) and analysis of the four elements (Catu-dhatuvavatthana) will lead only to the achievement of “Upacara-samadhi” (proximate concentration).

BRAHMA-VIHARA

Three Brahma-Viharas of 'Metta. Karuna and Mudita’ may carry one to the attainment of the three stages of lower jhanas, and a person who has attained the third jhana may, if he strives for the contemplation of “Upehkha,” the fourth of the Brahma vihara, can achieve the stage of Fourth jhana.

ARUPPA

A person who, by contemplation of kasina subjects, has attained all four jhanas, can achieve four Aruppa-jhanas by carrying out four Aruppa-kammatthanas in serial order one after another.

THE CONCISE METHOD OF ANAPANA MEDITATION

One who wishes to meditate 'Anapanassati’ meditation object should retire to a quite place and seat himself cross- legged or in any convenient manner so as to enable him to sit for a long time, with his body erect, and then first keep his mind fixed on the tip of the nostrils. He will then come to know distinctly the feeling of touch at the tip of the nostrils or at the edge of the upper lip, caused by the constant flow of his respiration.

This flow should be watched at the point of its contact and contemplated by noting 'coming, going, coming, going,’ on every act of inhaling and exhaling respectively. The mind should not be allowed to follow after the flow of the breath either on its inward or outward journey but should be kept at the point of touch constantly watching. While contemplating thus, there will be many hindrances ’nivaranas’ which make the mind wanders. Such hindrances should be dispelled bringing the mind back to the point of contact where in-breathing and out-breathing pass through, and then continue with the contemplation as 'coming, going, 'coming, going,’ as before.

By this means of continually watching the point of contact of the incoming and outgoing breath with attentive contemplation:

1. the long in-breathing and out-breathing are clearly noticed when they are long;

2. the short in-breathing and out-breathing are clearly noticed when they are short;

3. each course of gentle and delicate in-breathing and outbreathing with its beginning, middle and end is clearly noticed from the time it touches the tip of nose to the time when it leaves the nose; and

4. the gradual change from the harsh to the gentler form of inbreathing and out-breathing is also clearly noticed. As the respiration become more and more gentle, it would appear as if they have vanished altogether.

When it so happens, one may be searching for the incoming breath and outgoing breath, and may wonder what has happened. He may then remain at rest without carrying on the contemplation. However, it should not be done that way, and the mind should be fixed on the tip of the nose and the edge of the upper lip continuously noting as before. If the mind is so fixed attentively, the gentle form of flow of the in and out breathing will appear again and will be perceptible distinctly.

By thus proceeding with constant contemplation of in and out breathing, the incoming and outgoing breath will appear unusual and peculiar. The following are the peculiarities mentioned in the Visuddhi magga. In some cases the in-breathing and out-breathing appear like a shining brilliant star or a bead of red (ruby) precious stones or a thread of pearls; To some, it appears with a rough touch like that of a stalk of cotton plant or a peg (bolt) made of inner substance of hard wood; To other like a long braided chain (necklace), or a wreath of flowers, or a tip of a column of smoke; To other like a broad net-work of cobweb or a film of cloud or a wheel of a chariot or a round disc of moon or sun. It is stated in Visuddhi Magga that the variety of forms and objects visualised is due to differences in 'sañña,’ perception, of the individuals concerned. These peculiar visionary objects are known as “patibhaga-nimitta.” Commencing from the time of this nimitta, the samadhi which is then developed is called “Upacara-samadhi.” On continuing the contemplation with the aid of “Upacara-samadhi,” the stage of “Appana-samadhi” of four Rupa-jhanas can be reached. This is the brief description of the preliminary practice for 'Samatha’ by a person wishing to meditate by way of Samathayanika as a basis for the realization of Nibbana .

Source: http://www.yellowrobe.com/practice/meditation/224-how-to-practice-samatha-meditation.html

from Theravada - Dhamma Bậc Giác Ngộ Chỉ Dạy Được Các Bậc Trưởng Lão Gìn Giữ & Lưu Truyền - Feed https://theravada.vn/how-to-practice-samatha-meditation-by-mahasi-sayadaw/

from Theravada https://theravadavn.tumblr.com/post/624690207916228608

0 notes

Text

How to Practice Samatha Meditation – by Mahasi Sayadaw

Samatha Meditation - THE METHOD IN BRIEF (BY MAHASI SAYADAW)

The samatha meditation comprises (40) sorts. They are as enumerated below:

1. Kasina (10)

2. Asubha (10)

3. Anussati (10)

4. Brahmavihara (4)

5. Aruppa (4)

6. Ahare Patikkulasanna (1)

7. Catu-dhatu-vavatthana (1)

THE TEN SORTS OF KASINA ARE:

1. Earth kasina (pathavikasinam)

2. Water kasina (apokasinam)

3. Fire kasina (tejokasinam)

4. Wind kasina (Vayokasinam)

5. Brownish or deep purplish blue kasina (nilakasinam)

6. Yellow kasina (pitakasinam)

7. Red kasina (lohitakasinam)

8. White kasina (odatakasinam)

9. Light kasina (alokakasinam)

10. Open air-space, sky kasina (akasakasinam)

THE TEN ASUBHAS ARE AS FOLLOWS:

1. Swollen or bloated corpse. (uddhumatakam)

2. A corpse brownish black or purplish blue with decay (vinilakam)

3. A festering or suppurated corpse (vipubbakam)

4. A corpse splattered half or fissured from decay. (vicchiddakam)

5. A corpse gnawed by animals such as wild dogs and foxes: (vikkhayittakam)

6. A corpse scattered in parts, hands, legs,

head and body being dispersed (vikkhitakam)

7. A corpse cut and thrown away in parts after killing. (hatavikkhittakam)

8. A bleeding corpse, i.e. with red blood oozing out. (lohitakam)

9. A corpse infested with and eaten by worms. (puluvakam)

10. Remains of a corpse in a heap of bones, i.e. skeleton. (atthikam)

THE TEN ANUSSATIS ARE:

1. Fixing the mind with attentiveness and reflecting repeatedly on the glorious virtues and attributes of Buddha. (Buddhanussati)

2. Reflecting with serious attentiveness repeatedly on the virtues and qualities of Buddha's teachings and his doctrine. (Dhammanussati)

3. Fixing the mind strongly and repeatedly upon the rare attributes and sanctity of the Sanghas (Sanghanussati)

4. Reflecting seriously and repeatedly on the purification of one's own morality or sila. (Silanussati)

5. Repeatedly reflecting on the mind's purity in the noble act of one's own dana, charitableness and liberality. (Caganussati)

6. Reflecting with serious and repeated attention on one's own complete possession of the qualities of saddha. absolute faith, sila, morality, suta; knowledge, caga, liberality and panna, wisdom or knowledge just as the devas have, to enable one to be reborn in the World of devas. (Devatanussati)

7. Reflecting repeatedly with serious attentiveness on the supreme spiritual blissful state of Nirvana. (Upasamanussati)

8. Recollection of death or reflecting repeatedly on the inevitability of death. (Marananussati)

9. Reflecting earnestly and repeatedly on the impurity of the body which is composed of the detestable 32 constituents such as hair, body hair, nails, teeth, skin, etc. (Kayagata-sati)

10. Repeated reflection on the inhaled and exhaled breath. (Anapana-sati)

THE FOUR BRAHMAVIHARAS ARE:

1. Contemplation of loving kindness and goodwill or universal benevolence towards all sentient beings, praying "may all beings be happy." (Metta)

2. Contemplation, of compassion, i.e. pity for and sympathy with those who are suffering praying in mind that "may all beings be free from misery and suffering." (Karuna)

3. Contemplation of feeling rejoicing with others in their happiness or prosperity praying in mind that they "may continue to be happy and prosperous as at present with out diminution. (Mudita)

4. To remain indifferent with a feeling of equanimity to the state of condition of all beings, bearing an impartial attitude that things happen according to one's own kamma that has been committed. (Upekkha)

THE FOUR ARUPPAS ARE:

1. Meditation or fixing the mind intently on the realm of infinity of space, sky pannata. (Akasanañcayatanam)

2. Meditation or fixing the mind intently on the realm of infinity of consciousness, pathama ruppavinnana. (Viññanañcayatanam)

3. Meditation or dwelling the mind intently on Nothingness, i.e. nothingness, that remains or exists from pathamaruppavinnana. (Akincannayatanam)

4. Meditation on the realm of Neither-perception nor Non-perception, i.e. semi-conscious state Jhana's perception Tatiya (third) ruppavinnana as "so calm, tranquil and gentle." (Nevasañña-nasaññayatanam) Ahare patikulasañña: means the consciousness or perception of the impurity of material food derived from fixing the mind intently on the food and eatables as being detestable. Catudhatuvavatthanam: means contemplation on the existence or composition of the main four elements of dhatu in the body, namely, vayo (air or wind) and their differences in nature.

Ahare patikulasañña: means the consciousness or perception of the impurity of material food derived from fixing the mind intently on the food and eatables as being detestable.

Catudhatuvavatthanam: means contemplation on the existence or composition of the main four elements of dhatu in the body, namely, vayo (air or wind) and their differences in nature.

KASINA

A person who, of the forty sorts of samatha meditation, chooses the pathavi kasina as his subject of contemplation, should fix his eyes upon a spot of earth on the ground or a circle of earthdevice and contemplate mentally noting 'pathavi, pathavi,' or 'earth, earth, earth.' After repeated contemplation for a considerable time, the vivid image or nimitta of the earth-device will appear in the mind when the eyes are closed as clearly as when they are open.

This appearance of mental image is called "Uggaha, nimitta" (acquired image). If this "nimitta" becomes fixed and steady in the mind, he can go to any place and take up a posture of either sitting, walking, standing or lying. He should then continue to contemplate on the "Uggahanimitta" by saying mentally 'pathavi, pathavi,' or 'earth, earth.' While thus contemplating, it may happen that the mind does not remain fixed on its object and is likely to wander to other objects in the following manner.

1. The mind may think of desirable or agreeable objects according to its own inclination. This is called "Kamacchanda. nivarana" (sensuous lust).

2. The mind may also dwell on thoughts of despair and anger. This is called "Vyapadanivarana" (ill-will).

3. Slackness in contemplation may take place and the mind becomes dull and foggy. This is "Thina-middha-nivarana" (sloth and torpor).

4. The mind may become unstable and fleeting or restless, and then recollecting the past misdeeds in speech and bodily action, is likely to become worried. These are known as "Uddhaccakukkucca-nivarana" (restlessness and worry).

5. Thoughts may arise 'whether the contemplation which is being undertaken is a right method, or whether it is capable of bringing beneficial results, or whether there is any chance to achieve any good result's. This is "Vicikiccha-nivarana" (sceptical doubt).

When these five "Nivaranas" (Hindrances) appear, they should be discarded and rejected as they occur, and the mind should be immediately brought back to the original object of "Uggahanimitta" letting it dwell constantly on it, noting mentally as 'pathavi, pathavi.' If the kasina object of "Uggaha-nimitta" disappears from the mind, one should go back to the place where the earth-device is kept and contemplate again: 'pathavi, pathavi' by fixing the eyes on the device till "Uggahanimitta" is formed again in the mind's eye.

Thereafter, one should return to the desired place and proceed with the contemplation as before in any posture of sitting, standing, lying and walking. Carrying on thus the contemplation of the object of "Uggaha-nimitta" repeatedly for a long time, the object assumes a very brilliant and crystalline appearance quite unlike that of the original. This is called "Patibhaga-nimitta" (counterpart-image). At the time the mind is free from all 'Nivaranas.' It dwells fixedly on the "patibhaga-nimitta." This state of mind is known as "Upacarasamadhi" (proximate concentration). Now, by continually fixing the mind with this "Upacarasamadhi" on the 'Patibhaga- nimitta,' the mind reaches a state as if it were alive and sinks consciously into the object and remains fixed in it. This state of fixedness and stability of mind is known as "Appana-samadhi" (ecstatic concentration).

The Appana-samadhi is of four kinds, viz:

(a) the first Jhana

(b) the second Jhana

(c) the third Jhana

(d) the fourth Jhana

(a) In the first Jhana five distinct constituents are present; they are:

(1) Vitakka (initial reflection)

(2) Vicara (sustained investigation)

(3) Piti (rapture or ecstasy)

(4) Sukha (happiness or delight)

(5) Ekaggata (Tranquility of mind on one object with one pointedness.)

(b) One who has already attained the stage of first Jhana, seeing unsatisfactoriness in the first two constituents of 'Vitakka' and 'Vicara' again proceeds with the contemplation to overcome them and succeeds in attaining the stage of second Jhana where the three distinct constituents of 'Piti,' 'Sukha' and 'Ekaggata' are obvious.

(c) Again seeing unsatisfactoriness 'in Piti,' if he proceeds with the contemplation to overcome it and divests himself of ecstasy, he will attain the third Jhana which is a state of tranquil serenity and where the two distinct constituents of 'Sukha' and 'Ekaggata,' remains obvious.

(d) Again seeing unsatisfactoriness in 'Sukha' he proceeds with the contemplation to overcome it. By doing so, he attains the stage of fourth Jhana in which the mind exalted and purified is indifferent to all emotions alike of pleasure and of pain. At this stage the two constituents of 'Upekkha'-(equanimity) and 'Ekaggata' become manifested.

This is, in brief, the description of the manner of contemplation of the "Pathavi-kasina" and the development of the stages of four Jhanas. The same applies to the remaining kasinas.

ASUBHA

In the case of a person who wishes to practise 'Asubha' meditation objects, he should fix his eyes on a bloated corpse, or a livid corpse, etc., and contemplate by saying mentally 'bloated corpse, bloated corpse,' livid corpse, livid corpse, etc. This contemplation is similar to that of 'Pathavikasina,' the fundamental difference being that the contemplation of these 'Asubha' subjects will lead to the stage of First jhana.

ANUSSATI

Amongst the ten Anussatis, the contemplation of the impure 32 parts of the body (kayagatasati- kamma tthana) will also lead to the stage of First jhana. The eight reflections (Anussati) consisting of the subjects from "Buddhanussati" to "Marananussati"; reflection on the loathsomeness of food (Ahare patikulasañña) and analysis of the four elements (Catu-dhatuvavatthana) will lead only to the achievement of "Upacara-samadhi" (proximate concentration).

BRAHMA-VIHARA

Three Brahma-Viharas of 'Metta. Karuna and Mudita' may carry one to the attainment of the three stages of lower jhanas, and a person who has attained the third jhana may, if he strives for the contemplation of "Upehkha," the fourth of the Brahma vihara, can achieve the stage of Fourth jhana.

ARUPPA

A person who, by contemplation of kasina subjects, has attained all four jhanas, can achieve four Aruppa-jhanas by carrying out four Aruppa-kammatthanas in serial order one after another.

THE CONCISE METHOD OF ANAPANA MEDITATION

One who wishes to meditate 'Anapanassati' meditation object should retire to a quite place and seat himself cross- legged or in any convenient manner so as to enable him to sit for a long time, with his body erect, and then first keep his mind fixed on the tip of the nostrils. He will then come to know distinctly the feeling of touch at the tip of the nostrils or at the edge of the upper lip, caused by the constant flow of his respiration.

This flow should be watched at the point of its contact and contemplated by noting 'coming, going, coming, going,' on every act of inhaling and exhaling respectively. The mind should not be allowed to follow after the flow of the breath either on its inward or outward journey but should be kept at the point of touch constantly watching. While contemplating thus, there will be many hindrances 'nivaranas' which make the mind wanders. Such hindrances should be dispelled bringing the mind back to the point of contact where in-breathing and out-breathing pass through, and then continue with the contemplation as 'coming, going, 'coming, going,' as before.

By this means of continually watching the point of contact of the incoming and outgoing breath with attentive contemplation:

1. the long in-breathing and out-breathing are clearly noticed when they are long;

2. the short in-breathing and out-breathing are clearly noticed when they are short;

3. each course of gentle and delicate in-breathing and outbreathing with its beginning, middle and end is clearly noticed from the time it touches the tip of nose to the time when it leaves the nose; and

4. the gradual change from the harsh to the gentler form of inbreathing and out-breathing is also clearly noticed. As the respiration become more and more gentle, it would appear as if they have vanished altogether.

When it so happens, one may be searching for the incoming breath and outgoing breath, and may wonder what has happened. He may then remain at rest without carrying on the contemplation. However, it should not be done that way, and the mind should be fixed on the tip of the nose and the edge of the upper lip continuously noting as before. If the mind is so fixed attentively, the gentle form of flow of the in and out breathing will appear again and will be perceptible distinctly.