#samatha meditation

Photo

The Quest for Buddhism (115)

Buddhist cosmology

Samatha meditation – Part 2 [Part 1]

In Mahayana Buddhism, there are 5 hindrances (Ref) to samatha (Skt. shamatha, cessation): faith, determination, effort and sophistication of mind (belief, aspiration, diligence and lightness of mind) against the heavy-mindedness of omission, and the sati (Skt. smrti) against the careless mind.

Against the mind's losing sight of the object, against the mind's sinking without grasping the object such as depression, and against the mind's dissipation without staying on the object, it is correct knowledge, and against the rest it is inquiring mind and calmness of the mind.

Samatha meditation and jhana (dhyanaRef) are often considered synonymous by modern Theravada, but the four jhanas involve a heightened awareness, instead of a narrowing of the mind.

Through the meditative development of calm abiding, one is able to suppress the obscuring five hindrances: sensual desire, ill-will, tiredness and sleepiness, excitement and depression, and doubt. With the suppression of these hindrances, the meditative development of insight yields liberating wisdom.

仏教の探求 (115)

仏教の宇宙論

サマタ瞑想・その2(その1)

大乗仏教 (だいじょうぶっきょう、梵: マハーヤーナ)では止に対する5つの障害(参照)があるとし、心が重い懈怠 (けだい)に対しては信仰(信)、決断力(意欲)、努力(勤)、そして心の巧妙さ(軽安)であり、注意深さのない失念に対抗するのはサティ(梵: スムリティ、念)であり、鬱のように心が対象を把握せずに沈む惛沈 (こんじん) と心が対象にとどまらず散ってしまう掉挙 (じょうこ)には正知であり、それ以外に対しては、探求心と心の落ち着きが対抗する。

サマタ瞑想と禅定 (梵: デイヤーナ、巴: ジャーナ参照)は現代の上座部仏教 (じょうざぶぶっきょう、巴: テーラワーダ仏教)ではしばしば同義と考えられているが、4つのジャーナは心を狭めるのではなく、意識の高揚を伴うものである。

平静の瞑想的発展を通じて、人は官能的な欲望、悪意、疲労と眠気、興奮と落ち込み、疑いという不明瞭な五つの障害を抑制することができるようになる。これらの障害を抑制することで、瞑想的な洞察力を高め、解放的な智慧を得ることができる。

#samatha meditation#zen#mindfulness#buddhism#jhana#5 hindrances#zen tea#zen ikebana#wisdom#philosophy#nature#buddhist cosmology#art#art of zen

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Space is the Place--to Meditate...

The one who can control himself, can control the world—his world…

You don’t have to go anywhere to meditate, except inside. Much is made in the modern New Age movements of all the different kinds of meditation, which, according to the books and blogs can easily number into the dozens, if not hundreds. But most of those sources aren’t really Buddhist, not in any strict sense. Still, a quick…

View On WordPress

#anapanasati#Buddhism#CHRISTIANITY#dharma#Hardie Karges#language#mantra#meditation#mindfulness#New Age#samatha#Theravada#Tibetan#Transcendental Meditation#Vipassana#yoga

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Contemplative neuroscience (or contemplative science) is an emerging field of research that focuses on the changes within the mind, brain, and body as a result of contemplative practices, such as mindfulness-based meditation, samatha meditation, dream yoga, yoga nidra, tai chi or yoga"

#contemplative neuroscience#contemplative science#mindfulness#meditation#yoga#indus valley#physics#science#consciousness#samatha#tai chi#breathe#breathwork#neuroscience#neurophenomenology#Alan wallace#cognitive science#neurobiology#buddhism#Francisco varela#gnanayoga#Richard davidson#compassion#psychology#psychiatry#therapy#neuroplasticity

0 notes

Text

Concept of Death in

Theravada Buddhism - 01

Two common sayings particularly among Buddhists are

"Life is uncertain, death is certain" and "Death is certain, time of death is uncertain".

. However, most people,

Buddhists included, appear to be in complete denial of the possibility of death and they behave and live as if they are never going to die. Others are so terrified of their life ending in death one day, that they are reluctant to even talk about the subject of death. There is also a belief among some people that talking about the subject of death will somehow bring ill fate into their life. They fail to see the bare fact that death is a universal phenomenon which every living creature born into this world, human or otherwise, will have to face one day sooner or later.

Whatever one's circumstances are, young or old, rich or poor, strong or weak, healthy or ill, educated or uneducated etc. there is no one who can escape from the reality of death. In actuality, the process of death begins from the time of one's birth into this world and with each passing moment of one's life one is getting nearer and nearer to the inevitability of one's death. Some may die in the womb itself, others may die soon after birth, while others may die either young or old.

Medical definition of death is "Irreversible cessation of all vital functions especially as indicated by permanent stoppage of the heart, respiration and brain activity (including the brain stem)". In A Manual of Abhidhamma by Narada Thera, death has been defined as "the extinction of the psychic life (jivitindriya), heat (thejo dhathu) and consciousness (vinnana) of one individual in a particular existence". In broad Buddhist terms death can be described as a temporary end of a temporary phenomenon called life in this existence.

Concept of Death in

Theravada Buddhism - 02

The sight of four individuals including a dead man seen by Prince Siddhartha, is believed to have led him to give up the princely life and become a homeless ascetic in search of the way out of human suffering. The four sights were a feeble old man, a sick man, a corpse being carried by grieving relatives and finally a homeless ascetic in search of a way out of human suffering. Having listened to the explanations of these four sights given by his charioteer named Channa, he realised that no one including himself can escape from the suffering associated with old age, sickness and death. So, Prince Siddhartha gave up the royal luxuries to become a homeless ascetic in search of the way out of human suffering.

Ascetic Gautama learned and practised meditation under two of the most distinguished meditation teachers at that time called Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputta. He was able to master their meditation techniques quickly and was able to attain the highest possible deep states of absorption (jhana) that one could attain by practising concentration meditation (samatha bhavana). However, ascetic Gautama was not satisfied with such attainments as they did not lead to the deathless state with no more suffering that he was looking for. He subsequently left those two teachers to pursue his own search of a path out of suffering.

Then followed six years of severe austerity and self-mortification during which he was supported by five ascetic companions. Ascetic Gautama realized that neither the sensual pleasures that he had indulged in during his princely life nor the self mortification he underwent as an ascetic had helped him to find the way out of human suffering. Subsequently, he decided to follow the Middle Path which was to become one of the salient features of the Buddha's teaching.

On the night of the full moon of the month of May, at the age of 35 years, ascetic Gautama attained full enlightenment having realized Dependent Origination (paticca samuppada) and the four Noble Truths (chathur ariya sacca) and became Gautama Buddha.

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 03

In discussing the first Noble Truth, the Buddha described death as a cause of universal suffering along with other states such as birth, old age, sickness, separation from what one likes, association with what one dislikes, not getting what one desires etc.

It is said that while meditating during the process of attaining full enlightenment and investigating the cause of ageing and death through wise attention, the following order of the causative conditions appeared to ascetic Gautama's wisdom;

"Bhikkhus, before my enlightenment, while I was still a bodhisattva, it occurred to me: "Alas, this world has fallen into trouble, in that it is born, ages, and dies, it passes away and is reborn, yet it does not understand the escape from this suffering led by aging-and-death. When will an escape be discerned from this suffering led by aging-and-death? Then, bhikkhus, it occurred to me: When what exists does aging-and-death come to be? By what is aging-and-death conditioned? Then, bhikkhus, through wise attention, there took place in me a breakthrough by wisdom: When there is birth, ageing-and-death comes to be; ageing-and-death has birth as its condition"

In the same way, ascetic Gautama traced back the chain of causation by way of origin as far as ignorance;

"Birth is condition to old age and death

Becoming is condition to birth

Clinging is condition to becoming

Craving is condition to clinging Feeling is condition to craving Contact is condition to feeling

Six sense bases is condition to contact

Name and form is condition to six sense bases Consciousness is condition to name and form Mental formation is condition to consciousness

Ignorance is condition to mental formation"

Having fully realized the exact mechanism of Dependent Origination and attained full enlightenment, the Buddha declared the conditioned process of Dependent Origination which leads to existence of beings in the cycle of birth and death and to their suffering. The forward chain of the 12 factors which are interdependent shows the process of origination (samudayavara) that leads to rebirth, human suffering and death.

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 04

Forward chain of Dependent Origination

"Avijja paccaya sankhara

Conditioned by ignorance arise mental formations

Sankhara paccaya vinnanam

Conditioned by mental formations arises consciousness

Vinnana paccaya namarupam

Conditioned by consciousness arise mind and matter

Namarupa paccaya salayatanam

Conditioned by mind and matter arise six sense bases

Salayatana paccaya phasso

Conditioned by six sense bases arise contact

Phassa paccaya vedana

Conditioned by contact arise feeling

Vedana paccaya tanha

Conditioned by feeling arise craving

Tanha paccaya upadanam

Conditioned by craving arise clinging

Upadana paccaya bhavo

Conditioned by clinging arise becoming

Bhava paccaya jati

Conditioned by becoming arise birth

Jati paccaya jaramarana-soka-parideva-dukkha-domanassa-upayasa

Conditioned by birth arise ageing-death-sorrow-lamentation-pain-grief and despair"

The reverse order of the 12 factors of the Dependent Origination shows that when the factor of ignorance is eliminated by the development of true wisdom, all the other factors cease to arise leading to the deathless state of Nibbana and cessation of suffering.

In the Salla Sutta of the Khuddaka Nikaya, addressing a grief stricken father following the death of his son, the Buddha has stated the inevitability of death as follows;

"Un-indicated and unknown is the length of life of those subject to life

There is no means by which those who are born will not die With ripe fruits there is the constant danger that they will fall, in the same way, for those born and subject to death, there is always the fear of dying Just as the pots made by a potter all end by being broken, so death is of life"

In the Devaduta Sutta of the Anguttara Nikaya, the Buddha has described death as one of the three divine messengers along with old age and disease. When one encounters a dead body of a man or a woman, dead for a day, dead for two days, dead for three days, bloated up, livid, and oozing with impurities, one needs to reflect as follows;

"I too am subjected to death, I am not free from death,

Surely I had better do good through body, speech and mind"

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 05

Three universal characteristics

According to the Buddha's teaching, all physical and mental phenomena in the universe including human life are conditioned processes and have three common characteristics;

All conditioned phenomena are impermanent, meaning that they are subject to change (anicca) Due to impermanence, all conditioned phenomena are subject to unsatisfactoriness and suffering (dukkha)

All things conditioned and unconditioned have no autonomous or independent self (anatta)

However, due to the ignorance and our perverted thinking we see what is impermanent as permanent, what is suffering as happiness and what is non-self as self.

According to the Buddha's teaching, instead of an enduring and permanent entity called self or soul, what is conventionally described as a being, a person or an individual is a psycho-physical complex (nama-rupa), consisting of five aggregates which are interacting and interdependent on each other and are constantly in a state of flux;

Materiality (rupa)

Feeling (vedana)

Perception (sanna)

Mental tormation (sankhara and

Consciousness (vinnana)

The first aggregate is the material or physical matter while the other four are mental aggregates. Considering the fact that what we call a person, individual or a personality is nothing but a collection of the above five aggregates which are constantly in a state of flux, death can also be described as the dissolution of the above five aggregates.

So, when we consider one's death, in reality no particular person dies and dying is only a process with no person, soul or an enduring entity behind that process.

When one considers the phenomenon of death in human beings, it can refer to one of three types of death;

Death and rebirth cycle of physical matter and mental phenomena that takes place from moment to moment throughout one's life span (khanika marana)

Death of the physical body and the mental phenomena at the end of one's life span in this existence to be reborn in another existence (sammuthi marana)

Death of an enlightened (like the Buddha or an Arahant) following which there is no rebirth (samuccheda marana)

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 06

In Buddhist teaching there are four causes of death;

Kammakkhaya

When the potential energy of the kamma called the reproductive kamma that gave rise to a birth is exhausted, the life process will come to an end through death. This is similar to the flame of an oil lamp dying out when the wick is exhausted.

Ayukkhaya

When the life expectancy of the plane of existence that one is born into is exhausted, it will cause the death even if the kamma energy is still remaining. This is similar to the flame of an oil lamp dying out when the oil is exhausted, even though the wick is not exhausted.

Ubhayakkhaya

Here death will take place when both the reproductive kamma energy and the life expectancy are exhausted at the same time. This is similar to the flame of an oil lamp dying out when both the wick and oil are exhausted at the same time.

Upaccedaka

Here, while there is still remaining life expectancy, death will take place from unexpected or unnatural causes due to the appearance of a stronger kamma, positive or negative, that will obstruct the power of the reproductive kamma.

This is similar to the flame of an oil lamp dying out due to a strong wind though the wick and the oil are still not exhausted.

The first three types of death can be described as timely death (kala marana), while the fourth type of death (upaccedaka) is an untimely death (akala marana).

As can be seen above, kamma is a significant force influencing not only one's existence and the life experiences but also the manner and the timing of one's death in this existence. The word kamma in Pali, and karma in Sanskrit, means action, not all actions but intentional, volitional and willful actions which will lead to consequences sooner or later. Kamma is also called the law of cause and effect, every cause having an effect.

Once a volitional action has been performed it's effects, positive or negative, will eventually come to the person involved and no higher being or authority can do any thing about it.

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 08

According to Buddhist teaching, the death as we know it is considered an end of a temporary phenomenon, because following death the last stream of consciousness carrying the kammic energy will influence an immediate rebirth in another existence. At the time of one's death, the last thought moment called the death consciousness (cuti citta), will be influenced by a volitional action that is to be the reproductive kamma leading to the re-birth consciousness (patisandhi citta) of the following existence.

At the time of death there are four types of volitional actions that have the capacity to become the reproductive kamma and determine the nature of the next birth.

Weighty kamma (garuka kamma)

This is a strong volitional action, wholesome or unwholesome, committed by the dying person at any point in life which will overpower all other volitional actions and become the reproductive kamma at the time of death to determine the nature of the next birth.

Proximate kamma (asanna kamma)

This is a wholesome or unwholesome volitional action performed or remembered by the dying person just before the moment of death which, in the absence of a weighty kamma, will become the reproductive kamma and determine the nature of the next birth.

Habitual kamma (acinna kamma)

This is a wholesome or unwholesome volitional action that has been performed habitually during one's life, which at the moment of death, in the absence of a weighty or proximate kamma, will become the reproductive kamma and determine the nature of the next birth.

Reserve or cumulative kamma (katatta kamma)

This is the group of volitional actions in reserve that does not belong to any of the above three groups of kamma. At the moment of death, in the absence of any one of the above three groups of kamma, a cumulative kamma will become the reproductive kamma and determine the nature of the next birth.

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 09

Death Signs

Depending on the nature of the volitional action that is going to be the reproductive kamma, certain signs called death signs (nimitta) will appear at the moment of death.

These death signs can appear in one of three different forms;

A strong wholesome or unwholesome volitional action (kamma), that was performed during the life time or prior to the moment of death will appear in the consciousness as a memory through the mind door.

Instead of the actual volitional action, a symbol of the action (kamma nimitta) will appear in the consciousness.

For example, instead of remembering an unwholesome (e.g. killing a living being), one remembers the weapon that was used such as a gun or a knife. Likewise, instead of a wholesome act (e.g. an alms giving to Buddhist monks), one remembers the yellow robes or an alms bowl.

This sign can appear as an object through any of the six sense doors namely eye, ear, nose, tongue, body or mind door, which may have been the predominant sense at the time of performing the particular action.

A sign of destination (gati nimitta), indicating the type of the birth or the plane of existence one is going to be born into will appear in the consciousness as an object through the mind door. For example, if one is going to be born in a celestial world, welcoming celestial beings or palaces will appear as death signs and if someone is going to be born in a lower painful existence large fires or frightening faces will appear as death signs. It is believed that if the death sign indicates a negative or unhappy birth, it can be positively remedied to some extent by influencing the last thoughts of the dying person.

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 10

In Buddhist literature, there are two well known stories of two grief stricken ladies, who were helped by the Buddha by getting them to reflect on and realise the inevitability and the universality of death.

One was a lady known as Patachara, the daughter of rich parents, who had lost her two very young children, husband, both parents and brother through sudden death during a very short period. She lost her senses and was wandering in the streets weeping. People in the town chased her away by pelting stones at her and finally she arrived at the Buddha's monastery. When she had calmed down and composed herself in response to the Buddha's loving kindness and compassion, the Buddha had uttered the following two verses to console her and for her to reflect on;

"There are no sons for one's protection, neither father nor even kinsmen; for one who is overcome by death no protection is to be found among kinsmen

Realizing this fact let the virtuous and wise person swiftly clear the way that leads to Nibbana"

Having listened to and reflected upon the above statements by the Buddha, Patachara is said to have attained the state of Stream Enterer (Soatpanna). She became a Buddhist nun and eventually became an Arahant.

The other story is about a young lady called Kisa Gothami.

When her only child, a toddler son, died suddenly she could not accept his death and grief stricken went looking for a medicine to bring him back to life. She was eventually directed to the Buddha and when asked for a medicine, the Buddha asked her to go and get a mustard seed from a house where there had never been a death. She went from house to house asking for a mustard seed hoping that it would "cure" her son. She could not find a single household where there has never been a death in the family. Having discovered that there wasn't a single family who had not lost a family member through death, she came to the realisation that death is universal and is an inevitable aspect of life. Then, she was able to accept her son's death, buried his body and went back to listen to the Buddha. She too became a nun and attained Arahant stage.

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 11

Fear of death

Unless someone has attained enlightenment through wisdom from a Buddhist perspective, most people may have some anxiety and fear about death whether they express it openly, keep it to themselves quietly or repress it in their mind. Two types of the fear of death have been described; a healthy fear and an unhealthy fear. Those having a healthy fear of death are motivated to do some thing about it so that they can face death in a positive way by improving their attitudes, thinking patterns and behaviour including practising mindfulness and other meditation techniques related to death and dying. Those with an unhealthy fear of death are paralysed by it and are unable to do any thing about it through their anxiety and fear. It is said that people are actually afraid of the process of dying rather than death itself and it is not uncommon to hear people say that they are afraid to die a painful and traumatic death preferring to die in their sleep with no awareness.

One of the main reasons for developing a fear of death is the attachment to one's physical body and the mind that one identifies as "I" or "Me" and attachment to one's belongings which are identified as "Mine". This happens through the ignorance of the true characteristics of conditioned physical and mental phenomena which are impermanence, suffering and non-self. Some may worry about having to leave behind a spouse, children, relatives and friends as well as their assets and properties. Some of the other reasons for developing a fear of death may include;

Lack of insight into the nature of death

Fear of repercussions for bad things one has done in this

Fear of not knowing what will happen after death Fear of loneliness in death

Guilt for mistakes one has made Remorse for unfulfilled aspirations Remorse for unfinished affairs

Fear of physical and mental pain in death, and Living in a death denying culture

In the Abhaya Sutta of the Anguttara Nikaya, when a Brahmin called Janussoni stated to the Buddha that in his opinion there is no one who, subjected to death, is not afraid or in terror of death, the Buddha stated that there are those who are afraid of death and those who are not afraid of death.

• Those who are afraid of death are;

A person who has not abandoned craving for sensuality

A person who has not abandoned craving for the body

A person who has not done what is good and skillful

A person who is in doubt and perplexity about the true teaching of Dhamma

Those who are not afraid of death are;

A person who has abandoned craving for sensuality

A person who has abandoned craving for the body

A person who has done what is good and skillful, and

A person who has no doubt or perplexity about the true teaching of Dhamma.

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 12

Buddhist approach to facing death

An understanding that death is an essential part of human predicament and that death is a natural, inevitable and universal event in the life of every living creature including human beings born into this world will help one to develop a proper perspective of death. As stated by the following verse recorded in the the Maha Parinibbana sutta of the Digha Nikaya, one needs to understand that all conditioned phenomena including oneself which is just a psycho-physical complex (nama-rupa) consisting of the five aggregates are bound to pass away one day.

"Anicca vata sankhara, Uppada vaya dhammino"

"Impermanent truly are compounded things, By arising and passing away"

From the time of our birth, death is always behind us and it is so unpredictable that no one knows when, where and how one's death is going to come. There is no where that we can hide ourselves to protect us from death.

One can reflect on the three universal characteristics of all physical and mental phenomena as described by the Buddha; impermanence, suffering and the absence of a self or substantiality and try to realize the impermanent and transitional nature of this life. This should also help one to realize that death is only a process of dissolution of the five aggregates and that there is no person, individual or a self who dies or suffers in the process of dying.

According to Dhamma, the material aggregate and the four mental aggregates that we in conventional speech refer to as a person or an individual is composed of are in a state of constant flux. They undergo arising (birth), passing away (death) and re-arising (rebirth) on a continuous basis from the time of our birth till the time of our final death in this existence. So, we are dying and are re-born at each and every moment throughout our life though we are not conscious of it and the final death of the physical body and the mental faculties will be no different as it will lead to a rebirth in another existence straight away.

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 13

The twelve inter-linked factors of the Dependent Origination (paticca samuppada) explain the fact that one's birth and death are transient links in the cyclical nature of our existence in the cycle of birth and death (samsara). Thus, we may have been subjected to death followed by re-birth innumerable times previous to the present existence though we have no memory of it and will continue to do so until we attain Nibbana.

An understanding of the law of cause and effect (kamma) and how the wholesome and unwholesome actions performed have an influence on our birth, life experiences as well as our death may also help us to accept and face death in a more realistic manner. It will also encourage us to avoid unwholesome actions and perform wholesome actions in order to expect a positive outcome following the death in this existence. As described above, at the time of death a volitional action (kamma) committed in the past will appear as the reproductive kamma in the last consciousness and influence the nature of the next birth.

In Buddhist countries, it is customary for the relatives or clergy to remind a dying person of the meritorious actions that they have performed in their life so that hopefully one of those actions will appear as the last thought leading to a good re-birth.

The practice of mindfulness meditation as described by the Buddha will help the practitioner to reduce the attachment to one's physical body and also to realize the impermanence of the constituents of life. Mindfulness is the ability to attend objectively and non-judgmentally to the content of one's experience as it manifests from moment to moment in the immediate present. In the Satipatthana Sutta, the Buddha has described the four foundations of mindfulness.

The following two techniques of mindfulness out of the six techniques that the Buddha has described under the contemplation of the body will be helpful in reducing the attachment to the physical body and also to develop a realistic attitude towards death;

Mindfulness of repulsiveness of the body (patikulamanasika)

Nine cemetery contemplations (navasivathika)

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 14

The following two techniques of mindfulness out of the six techniques that the Buddha has described under the contemplation of the body will be helpful in reducing the attachment to the physical body and also to develop a realistic attitude towards death;

Mindfulness of repulsiveness of the body (patikulamanasika)

Nine cemetery contemplations (navasivathika)

In mindfulness of repulsiveness of the body, the meditator reflects on the impurity and repulsiveness of the various parts of the body from the soles up and from the top of the head hairs down. Thirty-two different parts have been described; head hair, body hair, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, tendons, bone, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, diaphragm, spleen, lungs, large intestines, small intestines, undigested food, faeces, brain, bile, phlegm, blood, pus, sweat, fat, tears, skin oil, saliva, nasal mucus, fluid in the joints and urine.

In nine cemetery contemplations, the meditator contemplates upon the nine stages of a decomposing corpse reflecting that one's own body is of the same nature as the decomposing corpse. Following death, one's own body will also decompose like that and no one can escape from it.

In the Upajjhatthana Sutta of the Anguttara Nikaya, the Buddha has described five subjects that should often be contemplated by every one; man, woman, lay person or a monastic:

I am subject to ageing, have not gone beyond ageing I am subject to illness, have not gone beyond illness I am subject to death, have not gone beyond death I will grow different, separate from all that is dear and appealing to me

l am the owner of my actions, heir to my actions, born of my actions, related through my actions, and have actions as my arbitrator.

There are people who are intoxicated with life and because of their intoxication they conduct themselves badly in their physical, verbal and mental actions. But, when they contemplate on the fact that they are subject to death and have not gone beyond death their intoxication with life will either be entirely abandoned or grow weaker.

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 15

Recollection of death (marananussati bhavana) is one of the ten recollections that have been described as suitable objects for meditation. It can greatly help the meditator to have an understanding of impermanence and the inevitability of death and as a result one may also change one's priorities in life. It will prepare one to face death in a more realistic way with less attachment to oneself and one's body, with equanimity and with no fear or anxieties about death.

In recollection of death, remembering a dead body one has seen and being mindful of one's own mortality, the following can be reflected upon;

"My body is also of a nature to die, Indeed, it will also die just like this one, It cannot avoid becoming like this"

Then the meditator can continue to reflect on the dead body by using one of the following thoughts;

"My death is certain; my life is uncertain"

"I shall certainly die"

"My life will end in death"

"Death - death"

In the Path of Purification (Visuddhimagga), Ven.

Bhddhaghosa has described eight different ways of reflecting on death;

As having the appearance of a murderer, who is keeping a sword to the neck to cut off the head at any moment As the ruin of success, ruining all the successes in life By comparing oneself to others in seven ways; with those of great fame, great merit, great strength, great supernormal powers, great understanding, and with Private Buddhas (Pacceka Buddha) and fully enlightened Buddhas As to sharing the body with many, including the worms and other creatures inside the body and external creatures like snakes and scorpions who can cause death

As to the frailty of life, bound up with breathing, postures, cold and heat, primary elements and nutriment whose imbalance can cause termination of life

As sign-less, with no signs for life span, illnesses, when and where one will die, where the body will be laid down and where one will be re-born

As to the limitedness of the extent of life

As to the shortness of the moment to moment life.

Concept of Death in Theravada Buddhism - 16

From a Buddhist point of view, death is a universal and inevitable natural event subsequent to the birth of each and every living creature including human beings.

According to Buddhist teaching there is no self or an abiding entity in us, but just a collection of five interdependent aggregates which keep dying and being re-born every moment of our life. The final death of the physical body and the mental faculties will be a similar event influencing a re-birth in another existence straight away. An understanding of the Buddhist principles such as the kamma, Dependent Origination, rebirth, and the three universal characteristics; impermanence, suffering and absence of an abiding self will be helpful for one to understand and accept the reality of death as a temporary end of a temporary phenomenon called life in this existence. Study of the Buddha's discourses in relation to the phenomenon of death and the practice of mindfulness meditations into the repulsive nature of the physical body as well as contemplation on death as described above should help one to accept and face one's death without anxiety and fear.

It should finally be noted that once born into this world there is absolutely no way of avoiding one's death.

According to Buddhist teaching, the only way to avoid death is to avoid birth by attaining the deathless state of Nibbana with no further re-birth through the cultivation of the Noble Eight-fold Path.

(End of the explanation on the concept of death in Theravada Buddhism)

#buddha#buddhist#buddhism#dharma#sangha#mahayana#zen#milarepa#tibetan buddhism#thich nhat hanh#enlightenment spiritualawakening reincarnation tibetan siddhi yoga naga buddha

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The new Thammayut sect took a more austere line than the centuries-old Mahānikāy, eating only one meal a day and rejecting all practices they saw as superstitious or linked to older “magical” (Thai, saiyasat) roots. Those old practices are now commonly referred to as boran kammaṭṭhāna, traditional meditation practices, by Buddhist scholars and ethnologists. Many samatha practices related to the states of meditative concentration known as jhāna, particularly those that develop high-energy states of pīti—also popularly regarded as saiyasat—were treated with wariness or simply rejected.

Whatever good intentions may have been behind the early reforms, there is no doubt in retrospect that establishing a second ordination line weakened the ability of the Saṅgha to function with a unified voice to protect the Dhamma. This came to a head from the 1950s onward when heavy political promotion of a “new” vipassanā, or insight meditation, method from Burma led to active suppression of jhāna traditions that had been central to the Path since the time of the Buddha. The reform movement claimed that jhāna meditation was in fact not necessary to develop the entire Buddhist Path.

Within a few years, temples across Thailand and Burma, and soon more widely with repercussions worldwide, were instructed to cease teaching and practicing jhāna meditation, and to instead train in and teach the “more scientific” vipassanā methods.

[...]

Jhāna belongs within what is commonly described as the samatha division of Buddhist meditation, often translated as “tranquility” or “serenity,” with the second division being vipassanā, translated as “insight” or “wisdom.” Mindfulness, a much more familiar term in the West and well known in its own right as a recognized treatment for recurrent depression, is just one of several basic factors underpinning both samatha and vipassanā. Historically, over more than 2,500 years, Buddhist teachers have regarded both jhāna meditation and vipassanā as essential practices to complete the Path. Usually translated as “absorption,” jhāna has a secondary root, jhāpeti, meaning “to burn up,” which is a reflection that jhāna is a highly active and far from passive state, and that the translation of samatha as tranquility or serenity can be rather deceptive.

In core Buddhist meditation traditions, extending back to the time of the Buddha, samatha and vipassanā went hand in hand; they were twin aspects of the Path toward understanding the human condition and the arising and ending of suffering, leading ultimately to enlightenment, nibbāna. The reforms of the 1950s, however, attempted to remove this interdependence; samatha and jhāna practices were attacked as unscientific and were suppressed in favor of a “new” Burmese vipassanā tradition that claimed jhāna, and therefore samatha, was not necessary to develop insight and realization of Buddhist goals.

It has to be said that the reform movement was very successful, and by the mid-1960s any organized teaching of the old samatha practices had all but disappeared, certainly in Thailand and Burma, but soon across South and Southeast Asia and eventually worldwide. The new face of Buddhism had become vipassanā. In addition, many Buddhists in Thailand where the suppression had been most aggressive also believed it was not possible, in any case, to develop and practice jhāna in a lay context outside monastic and forest meditation traditions.

-- Paul Dennison, Jhana Consciousness

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

2.(✨)9.(🦄)10.(🍄)11.(🌻)12.(🦚)13.(🌿)14.(⭐) 17.(🧜🏿♀️) 18.(🧭) extra: 21.(🌈)What do you fall back on in times of uncertainty? Do you envision the destination, conjure up memories to give you strength or ______? Rivers!!! I loved reading your writings so I'll just go ahead and send in the rest of the ask game if nobody else has. Feel free to answer whatever you're comfortable with and I added a bonus just because I felt like it:

Looks like I’ll have to find myself another ask game now! I am happy you are so enthusiastic about my writing :)

2. (✨) - what was your first spell? Did it work?

It was a simple candle spell. A friend of mine was looking for a job and had no luck. He had been searching for weeks or months, I don’t remember exactly how long. So I carved Fehu into a green candle and prayed over it every morning for a week, asserting that he would find a job within one week’s time. And he did. He got a job offer from a friend of a friend after exactly one week.

9. (🦄) - what’s something that’s talked about too much in the witchcraft community?

This’ll have to be the same answer as its counterpart number 8, I’m afraid. I spend very little time online, so I’m not keeping track of community affairs.

10. (🍄) - do you use labels for your practice? Which ones?

I am a Buddhist, an animist, and an aspiring plant wizard! Sometimes a Druid too, though I’ve been a bit out of touch with Druidry lately.

11. (🌻) - post a photo of your altar or describe it if you’re comfortable.

No can do! In general I would advise against sharing any images that are important to one’s magical and spiritual practice, for the same kind of reason you wouldn’t want to leave your doors or windows open when you leave the house.

12. (🦚) - what does your religion or spiritual path mean to you?

Answered here

13. (🌿) - what witchcraft area are you super interested in but haven’t tried out yet?

If and when I have the time, energy and space for it, I would like to craft and keep spirit vessels. I love crafting – with thread, yarn, wood, clay. I enjoy designing sigils and writing poetry. I think these skills would come together quite nicely.

14. (⭐) - do you celebrate any sabbats/holidays? Which ones and which one is your favorite?

Unfortunately I am really bad at celebrating any kind of festival or holiday that occurs at certain times or days of the year. If it’s not something I can do everyday, any day, or spontaneously, it won’t make it into my practice. I would love to actively engage in seasonal celebrations. However I am very much guided by my own inner seasons and cycles. My body and mind also don’t align with the pagan wheel of the year. For instance, I feel most energised in spring and autumn, and find summer and winter quite draining. I also have zero interest in the fertility aspects of the sabbats. One day I’d like to design my own wheel of the year based on my personal inclinations. In terms of big Chinese holidays like New Year and Mid-Autumn Festival, my celebrations are pretty much “meet family, eat lots of food!”

17. (🧜🏿♀️) - how often do you meditate? Do you mainly do guided meditations or just listen to music/nature?

My meditation practice is currently rather sporadic. It’s a skill that still requires some work. At the moment I can comfortably meditate for 15 minutes without interruption, and on occasion for up to 30 minutes. My goal is to be able to meditate for at least an hour without getting too restless. I mainly practice samatha meditation (i.e. emptying the mind, non-attachment to thoughts and emotions). This is the main method of clearing psychic blockages and honing intuition. I’m quite a fan of the Druid colour meditations too.

18. (🧭) - where do you get most of the energy to do all your spells from?

There are two main things that drive me. Necessity, and inspiration.

21.(🌈)What do you fall back on in times of uncertainty? Do you envision the destination, conjure up memories to give you strength or __?

There is always one question that gets me through everything. “What can I do right now, with the resources that I have?” As long as I know the answer to this question, I will have a plan of action, and I will not worry. Even if the answer is “nothing”, in which case the action will be “wait and see how the situation develops” or “accept whatever happens and move on”. Knowing where I stand in any given situation calms me instantly.

9 notes

·

View notes

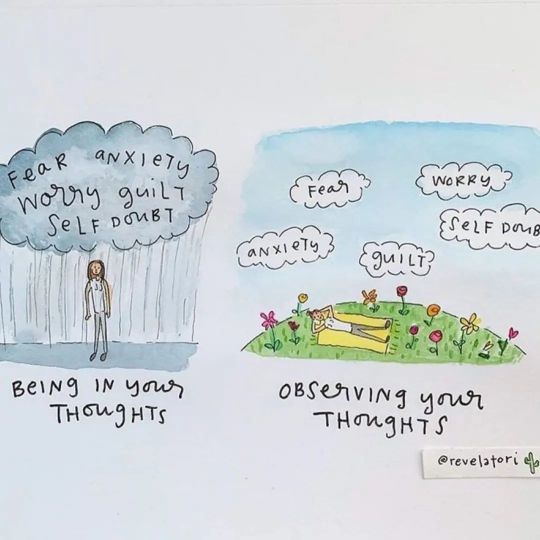

Photo

A beneficial side-effect of a regular meditation practice. #Mindfulness #Satipațțhāna #Shamatha #Samatha #Vipashyana #Vipassana #ShamathaVipashyana #SamathaVipassana (at New Haven Zen Center) https://www.instagram.com/p/CjNQsFFOoK5/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

That feeling when you meditate too hard and you get samatha all over your skandhas 😒

1 note

·

View note

Text

The full, formal name of the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment is the Great Corrective Extensive Perfect Enlightenment Sutra of the Complete Doctrine. Pretty daunting! As the title might suggest, It’s not an enlightenment that is attained from any partial aspect of the the Buddha’s teaching, such as the "elementary" teachings or prajñāpāramitā teachings.

This is the Buddha teaching the Bodhisattvas present how to break their own misconceptions and confusion about what they have gleaned from his previous sermons. And it’s not just so the assembled Bodhisattvas can realize their own awakening, but how to help and teach all sentient beings (of the degenerate age, as the Sutra terms it). And, we sentient beings (of the degenerate age) can break some our bad habits. How many of us fall into the trap of Sudden Awakening…and nothing else, or silent illumination is the way (gradual), or in our Sangha’s case, Sudden Enlightenment, Gradual Cultivation. How many fall into the Mahayana/Hinayana trap (even if we don’t use the “H” word any more), going back 1,500+ years to when that division was first made?

This Sutra, through the questions/dialogues with twelve bodhisattvas runs the gamut form Sudden (Manjushi’s opening chapter), all the way through to Perfect Enlightenment bodhisattva and Most Excellent of Worthies bodhisattva in the gradual end. The SPE’s key message is, as ZM Seung Sahn might say, “Try, try, try for 10,000 years, become enlightened, and save all beings.” The Buddha emphasizes to tool of meditation, for the bodhisattvas to make retreats of varying lengths, and for all sentient beings also practice it diligently also. For them he gives us the “try, try, try” approach—if samatha doesn’t do it, try samapatti, and if needed, to dhaysna. Calm the mind, become mindful of emptiness, then focus and concentrate. The Buddha doesn’t specifically say that they must go consecutively in that order, or that dhayana is superior to samatha.

Do whatever it takes to dispel preconceptions (and conceptions generally), realize the emptiness of them, and in so doing, liberate ourselves from hindrances. One vehicle isn’t great or lesser, the Pali Canon isn’t superior to the Mahayana (SPE is a Mahayana Sutra, after all) or vice versa. Anything that causes confusion or leads to misconceptions needs needs to be corrected, and through the bodhisattva’s questions provides an “owner’s manual” of what to do to make the repairs.

It’s not one of the better-known Sutras in the West, although it has been a formative teaching in China and Korea. It emphasizes the need for persistence, patience, and dedication to realizing the inherent ability for us all to Awaken, and the need for all of us to help all sentient beings to realize it.

The SPE has been a favorite of mine since I was initially introduced to it, if for no other reason than to break down barriers, and the need to “Try, try, try for 10,000 years, become enlightened, and to save all beings.”

youtube

0 notes

Text

body, thought, heat: interconnection

Ajahn Sucitto

There are two processes that steer the kamma of meditation. The first process is one of strengthening and healing the heart through calming (samatha). Samatha practices use a steadying focus and a soothing attitude. The second process is ‘insight’ (vipassanā) – which is about seeing how things really are. The two processes work together: as you get settled and at ease, your…

View On WordPress

#anatta#anicca#awareness#Buddhism#conscious experience#letting go#loving-kindness#metta#mindfulness#non-duality

0 notes

Text

Meditation and Spirituality: Exploring Different Cultural Practices

Meditation is a practice that transcends cultural and religious boundaries, offering profound spiritual benefits to practitioners worldwide. While the techniques and purposes of Best Meditation Center In Pokhara can vary widely across different traditions, the core objective remains similar: to attain a state of inner peace, heightened awareness, and a deeper connection with the divine or the self. This article explores the spiritual aspects of meditation in Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, and other spiritual traditions, highlighting the unique elements and commonalities that unite them.

Buddhism

Meditation in Buddhism is central to its practice and philosophy, aiming to cultivate mindfulness, concentration, and insight. There are two primary types of Buddhist meditation:

Samatha (Calm Abiding)

This practice focuses on developing concentration through mindfulness of breathing or other objects of meditation. The goal is to achieve a tranquil mind, free from distractions and agitation.

Vipassana (Insight)

Vipassana meditation involves observing the impermanent nature of all phenomena to gain deep insight into the nature of reality. It encourages the practitioner to develop a clear understanding of the Three Marks of Existence: impermanence, suffering, and non-self.

Buddhist meditation practices often include chanting, visualization, and prostration, with an emphasis on ethical conduct and mental discipline as essential components of spiritual growth.

Hinduism

Dhyan (Meditative Absorption)

Dhyan involves deep concentration on a single point of focus, such as a deity, mantra, or the breath. The aim is to transcend the ordinary mind and experience spiritual ecstasy or union with the divine.

Mantra Meditation

This practice involves the repetitive chanting of sacred sounds or phrases, such as "Om" or "Hare Krishna." Mantras are believed to have spiritual power and aid in purifying the mind and body.

Kundalini Meditation

Focuses on awakening the dormant spiritual energy (Kundalini) located at the base of the spine. Through practices like breath control (Pranayama) and visualization, practitioners aim to raise this energy through the chakras to achieve spiritual enlightenment.

Hindu meditation practices are often accompanied by rituals, devotional worship (Bhakti), and adherence to ethical principles outlined in texts like the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads.

Christianity

Meditation in Christianity is often contemplative, aimed at deepening one's relationship with God and experiencing divine presence. Key practices include:

Contemplative Prayer

This silent prayer practice involves focusing on a word or phrase that signifies God's presence. It aims to still the mind and open the heart to God's love and guidance.

Lectio Divina (Divine Reading)

A meditative approach to reading the Bible, involving four stages: reading (Lectio), meditation (Meditatio), prayer (Oratio), and contemplation (Contemplatio). This practice seeks to foster a deeper understanding of Scripture and its application to one's life.

The Jesus Prayer

A repetitive prayer practice, commonly used in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, involving the repetition of the phrase "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner." This prayer helps cultivate humility, repentance, and continuous remembrance of God's presence.

Christian meditation often incorporates elements of silence, reflection, and a focus on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ, encouraging a transformative encounter with the divine.

Other Spiritual Traditions

Sufism (Islamic Mysticism)

Sufi meditation practices, such as Dhikr (remembrance of God), involve the repetitive chanting of God's names or attributes. Sufis also engage in practices like Sama (listening to spiritual music) and Whirling (a form of meditative dance) to achieve spiritual ecstasy and union with the divine.

Taoism

Taoist meditation focuses on aligning with the Tao (the Way), cultivating inner peace, and harmonizing with nature. Techniques include breath meditation (Zuòwàng), visualization, and Qi Gong, which involve the cultivation and circulation of life energy (Qi).

Indigenous Traditions

Many indigenous cultures incorporate meditation-like practices in their spiritual rituals. These may involve vision quests, shamanic journeys, and communal ceremonies aimed at connecting with ancestral spirits and the natural world.

Commonalities Across Traditions

Despite the diverse methods and objectives, several commonalities unite these spiritual meditation practices:

Focus and Concentration

Almost all traditions emphasize the importance of focusing the mind, whether on the breath, a mantra, a sacred text, or a divine image.

Inner Peace and Stillness

The goal of achieving a state of inner calm and tranquility is universal across different meditation practices.

Ethical and Moral Conduct

Many traditions stress the importance of living a virtuous life as a foundation for effective meditation. Ethical conduct helps to cultivate a mind that is conducive to deep meditation.

Connection with the Divine or Higher Self

Meditation is often seen as a way to deepen one's relationship with the divine, attain spiritual insights, or realize the true nature of the self.

Transformative Experience

Meditation is regarded as a transformative practice that can lead to profound personal and spiritual growth, helping practitioners develop qualities such as compassion, wisdom, and humility.

Conclusion

Meditation is a universal practice that transcends cultural and religious boundaries, offering profound spiritual benefits to practitioners around the world. Whether it's through the mindfulness of Buddhism, the devotional practices of Hinduism, the contemplative prayers of Christianity, or the mystical traditions of Sufism and Taoism, meditation serves as a powerful tool for attaining inner peace, heightened awareness, and a deeper connection with the divine. By exploring and embracing the unique elements and commonalities of these practices, individuals can enrich their spiritual journey and cultivate a more harmonious and enlightened life.

0 notes

Photo

The Quest for Buddhism (114)

Buddhist cosmology

Anapanasati - "mindfulness of breathing"

Anapanasati (Skt.anapanasmrti), meaning "mindfulness of breathing" that "sati" means mindfulness; "anapana" refers to inhalation and exhalation, paying attention to the breath. It is a type of cessation (samatha meditation Ref) in which consciousness is calmed and focussed by being aware of the in-breath and out-breath (breath), or counting breath. In a broader sense, it moves from there to the observation of the body and includes the area of contemplation (vipassana meditation), which corresponds to the 4 presences of mindfulness (Pali: cattaro satipatthana), that is one of the seven sets of thirty-seven qualities (Ref2).

It is the quintessential form of Buddhist meditation, attributed to Gautama Buddha, and described in several suttas, most notably the Anapanasati Sutta.

Derivations of anapanasati are common to Tibetan, Zen, Tiantai and Theravada Buddhism as well as Western-based mindfulness programs.

仏教の探求 (114)

仏教の宇宙論

安那般那念〜「呼吸の心得」

安那般那念 (あんなはんなねん、巴: アーナーパーナ・サティ、梵: アーナーパーナ・スリムティ)とは、「呼吸の心得」を意味する、呼吸に注意を向ける瞑想法である。「サティ」は心得、「アーナーパーナ」は入出息 (呼吸)を意味する。息を吸ったり吐いたりすること(呼吸)を意識すること、または息を数えることによって意識を静め、集中させるサマタ瞑想 (止行:参照)の一種、ないしは導入的な一段階を意味するが、広義には、そこから身体の観察へと移行していき、四念処 (しねんじょ、巴:チャッターロー・サティパッターナー)に相当するヴィパッサナー瞑想 (観行)の領域も含む。四念処 (しねんじょ) とは、仏教における悟りのための4種の観想法の総称で、三十七道品(参照2)の中の1つ。

仏教の瞑想の真髄であり、ゴータマ・ブッダのものとされ、安般念経 (あんはんなねんきょう、巴: アーナーパーナ・サティ・スッタ) をはじめとするいくつかの経典に記述されている。

チベット仏教、禅宗、天台宗、上座部仏教、西洋のマインドフルネスプログラムに共通するのは、安那般那念 (あんなはんなねん、巴: アーナーパーナ・サティ) が由来している。

#anapanasati#mindfulness of breathing#samatha meditation#buddhism#vipassana meditation#buddha#forest mushrooms#mindfulness#nature#art

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

A supplicant seeks the compassion of Kuan Yin

The Practice of Meditation

By the autumn of this year, 2020, I will have been practising meditation for fifty years. I began as an undergraduate, when I joined a Buddhist class to learn Samatha meditation, which focuses primarily on the breath. Later I changed to a different, Western practice which uses an inner sound as its focus. Meditation itself is subtle, but the most effective practices tend to use very simple methods to help still the mind, paying attention to breath, sound, or an image. There is no striving for effects; the aim is to bypass the ‘busy mind’. Trains of thought, rising and falling emotions, and physical sensations can be acknowledged, but are not dwelt on. We cannot stop these entirely, but we can learn to let them go, and thereby open up to a different, spacious and more inclusive form of consciousness.

‘The essence of meditation is the engagement and holding of a mental object, which can be a sound, image, or movement like walking. As the mind stays with this object it gradually magnetises all the mental movements, flurries of thought and feelings, associative chattering etc. towards a single vector, rather like iron filings turning in one direction. And so random thought activity tends to die down, and settle, not so much around, as near the object, which itself gets finer and finer as does the breath. The seed-object can disappear, or hover on the edge of awareness, and pure consciousness rest within itself like fine wine upon its lees.’

(Tessellations, Lucy Oliver – Matador, 2020, p.51)

In the traditions I’ve studied and encountered, regular practice is crucial, along with an experienced teacher or ‘checker’, at least in the early years, to help you stay on track. Meditation as such can’t really be learnt from books. And it also takes time. My first meditation teacher described the practice as being like a drip, drip, drip of water – a drop a day, perhaps – until the cistern eventually fills up and you have a reservoir. Regular meditation is not exciting or instantly gratifying, although it can and does bestow a sense of calm, and helps to centre one’s being. Over time, though, it becomes a core practice, which can become the quiet centre of your daily life.

I’ve written this brief overview of meditation as a prelude to introducing a more specific and defined kind of practice. This is the Moon Meditation of Kuan Yin: a combination of meditation and visualisation. I suggest though that rather than using it a core meditation practice, it’s perhaps best attempted occasionally, or for short periods. It does not need a teacher as such, and is something that might be rewarding to try, whether you’re already a regular meditator or not. As I’ll outline, it focuses on a female figure – archetype, goddess, spirit of the feminine as you will – that of Kuan Yin.

Spirit of the feminine in meditation

Meditation generally aspires to reach a level of consciousness which transcends male and female differences. But it could be argued that some practices are at least more outwardly orientated to a masculine or feminine approach. So how do you approach a more feminine form of meditation? A few years ago, I was delighted to come across a tradition of meditation which does just that, and is associated with the archetypal figure of Kuan Yin, also known as ‘the universal goddess of compassion’. Since then, I have often practised Kuan Yin Moon Meditation at times when I wish to strengthen my contact with the feminine spirit, perhaps when life has been particularly bruising. ‘She Who Hears the Cries of the World’ is a calming and helpful presence.

The temple of Kuan Yin, Georgetown, Penang

Discovering Kuan Yin

I first discovered Kuan Yin’s temples when visiting Hong Kong, Penang and Singapore on different occasions. Each one was a feast for the senses, decked in rich, red and gold colours, imbued with the heavy scent of incense, and enlivened by the constant clatter of divination sticks shaken in brass cylinders. The temple is also an oracle, and so it’s possible to ask Kuan Yin personal questions through the 100-stick divination system, each of which has its own interpretation. Here, I watched worshippers young and old, male and female, as they piled fruit and flowers on Kuan Yin’s shrines, and sought her guidance. Later, looking into the mythology of her origins, I found that she is one of the most widely prevalent forms of the divine feminine spirit, who cannot be pinned down to one religion or culture. She slips from Buddhism to Taoism and Shintoism. She has connections both with Christianity, and the ancient religion of Egypt. And, strictly speaking, she is neither a goddess, immortal spirit, nor Madonna, but embraces all these definitions. Her predominant qualities are that of mercy and benevolence.

The temple of Kuan Yin, Georgetown, Penang

Kuan Yin’s Meditation

The meditation that I share here is a traditional one, based on her long association with the moon and the ocean. (She has other attributes, but these are the most relevant here.) In her Moon form, she represents the waters of compassion, and the gentle light of healing.

This Moon Meditation can be practised without having a particular religious or cultural affiliation. The version that I use comes from the account of an old Chinese nun, who had practised it constantly during her lifetime.* Here, Kuan Yin is seen robed in white, a lady of the seas, who rises above the waves to unite sky and sea, moon and earth. This is the theme of the meditation, where she is invited to shine forth, and – if we’re lucky – bring comfort and wisdom to our hearts.

Practising Kuan Yin meditation may be particularly appropriate at certain times in our lives. For women, it may be when we long to re-connect with a tender, intimate version of the feminine spirit. For men, the practice of opening the heart via the feminine spirit can help to awaken subtle emotions. For both, the practice can be consoling in times of need. And beyond the personal level, the aim of this meditation is to help generate compassion for the good of all our fellow human beings.

A blanc-de-chine porcelain statue of Kuan Yin, in my possession, which has been made in the same way, and in the same location in China, for several hundred years. There is a water reservoir inside, so the figure of the goddess can pour little drops of water from her flask into the lotus pool below.

The Practice

Here is how I’ve formulated this ancient practice, and taught it to others in accordance with modern needs:

The meditation can be practised for between ten minutes and half an hour, but I suggest you aim for something shorter to begin with. It’s suitable for practising either within a group, with someone who can lead it from stage to stage, or else as a personal contemplation, where you go at your own pace. It’s necessary to conduct it in a quiet place, which is likely to be in a room indoors, although the traditional instructions suggest it can also be done on a hilltop, or under an open sky. Do everything gently: no forcing, just allowing. You are activating this sequence, and envisaging images as needed, but in a spirit of gentle calmness.

To begin:

Sit quietly, with your eyes closed, and let your mind go still. Release any thoughts or images, and gradually glide into neutral. Relax the breathing, until it finds a natural, unhurried level.

Now let your internal gaze rest on an empty expanse, as if on a dark, empty sky, or as if you are looking into darkness before your eyes adjust to what is there. This might sound difficult, but is quite easy in practice, and you only need to hold this for a few seconds.

Then, something comes into view. You can now see the sea in front of you, and you witness the moon rising above in the night sky. The moon bathes the sea with a soft brightness, rippling with little silver-topped waves. Allow yourself to gaze now at the moon, and to feel calm and happy. Give this a few minutes to develop.

Then observe how the moon is getting smaller, but brighter. It becomes so bright and so small that it reduces to a dazzling pinprick of light, a radiant tiny pearl in the night sky. Then this seed of light begins to grow, and, as it does so, it becomes the figure of Kuan Yin herself. She stands tall against the sky, robed in gleaming white. Around her head is a halo of light. Her feet float on the crest of the waves.

Kuan Yin smiles, and you feel her affection, love and compassion. Allow yourself to rest in her presence. You can allow emotions to arise and fade away again, like the lapping of the water. Let the meditation take its course: Kuan Yin may stay with you for a long time, or just for a brief spell. As she leaves, your image of her gets smaller and smaller until she vanishes, along with the sea and the sky. All that is left is space. Relish this space; become a part of it, and know that you are not separate from it.

As with all meditation practices, it’s advisable to make a definite ending, but to do so calmly and slowly. Now return gently to sensing your body; observe your posture, and allow sensation in your limbs. Then open your eyes, and collect yourself, body and mind. If it seems appropriate, offer thanks for the experience.

*The original description of this meditation is contained in Bodhisattva of Compassion: the Mystical Tradition of Kuan Yin, John Blofeld (p.124 in my edition).

You may come across Kuan Yin figures in unexpected places. This one sits on a resplendent mantlepiece in Saltram House, a National Trust stately home.

Other References

The Kuan Yin Oracle: The Voice of the Goddess of Compassion, by Stephen Karcher

Kuan Yin: Myths and Revelations of the Chinese Goddess of Compassion, by Martin Palmer, Jay Ramsay & Kwok Man-Ho

The Meditator’s Guidebook: Pathways to Greater Awareness & Creativity, by Lucy Oliver; see also her website ‘Meaning by Design’

Samatha meditation classes can be

Source: https://cherrycache.org/2020/05/28/the-moon-meditation-of-kuan-kin/

0 notes

Text

item # K22C54

RARE Pra Somdej Pai-pok, Luang Phu Peuak, Wat King Kaeo, Nua Pong. The Buddha amulet with a bas-relief of a Meditating Buddha in Dukkarakiriya (self-mortification or Fasting Buddha) seating on a 16 tiers platform, and in the back is a bas-relief of a “Yant Kru” of Luang Phu Peuak of Wat King Kaeo, Thai numbers, and the number 2515 the Buddhist Era it was made. Made from many types of holy powder includes the Pattamang Holy Powder of Luang Phu Peuak of Wat King Kaeo, blended with holy water, and plaster cement. This amulet was made in a shape of an ancient Chinese playing card (Cherki) or Pia-pok in Thai. Made by Wat King Kaeo, Samut Prakan Province in BE 2515 (CE 1972), the Grand Blessing / consecration Ceremony and Ritual were held at the temple of Wat King Kaeo, also attended by Luang Phu Toh of Pradu Chimphli, and other guru monk of that period.

……………………………………………………

BEST FOR: Thais believe thatPra Somdej Pai-pok, Luang Phu Peuak, Wat King Kaeo helps bring luck in betting and gambling, esp card games like Poker, Blackjack, and Baccarat. It also helps you achieve prosperity and fulfillment in your work and career, avoid misfortune, and improve your luck, power, and prestige. It protects and secures you from all peril, misfortune, and disaster. Anything you wish for, and it could change your life for the better. Klawklad Plodpai (bringing safety, and pushes you away from all danger), Kongkraphan (making you invulnerable to all weapon attack), Maha-ut (stopping gun from shooting at you), Metta Maha Niyom (helping bring loving, caring, and kindness, and compassion from people all around you to you), Maha Larp (bringing Lucky Wealth / wealth fetching), and Kaa Kaai Dee (helping tempt your customers to buy whatever you are selling, and it helps attract new customers and then keep them coming back. Ponggan Poot-pee pee-saat Kunsai Mondam Sa-niat jan-rai Sat Meepit (helping ward off evil spirit, demon, bad ghost, bad omen, bad spell, curse, accursedness, black magic, misfortune, doom, and poisonous animals). And it helps protect you from manipulators, backstabbers, and toxic people.

……………………………………………………

The Buddha amulet with 16 tiers

The amulet with figure of Buddha seating on a 16 tiers, it represents Buddha is above Brahma Loka (Brahma Worlds or Brahmā Realms). According to the Brahma Worlds (brahma loka) in Theravada Buddhism, the Brahma Loka is under Nirvana (where Buddha is), and there are sixteen realms, or planes or heavens, of fine material existence (rupa brahma loka) in which rebirth takes place when one passes away while in one of the first four deep absorption states (rupa jhana) through concentration meditation (samatha bhavana).

1)Retinue of Brahma (brahma-parisajja)

2)Ministers of Brahma (brahma-purohitha)

3)Great Brahmas (maha brahma)

4)Devas of limited radiance (parittabha)

5)Devas of unbounded radiance (appamanabha)

6)Devas of streaming radiance (abhassara)

7)Devas of limited glory (parittasubha)

8)Devas of unbounded glory (appamanasubha)

9)Devas of radiant glory (subhakinna)

10)Very fruitful devas (vehapphala)

11)Devas with only the body and no mind (asanna satta)

12)Durable devas (aviha)

13)Untroubled devas (atappa)

14)Beautiful devas ( sudassa)

15)Clear sighted devas (sudassi)

16)Peerless devas (akanittha)

REMARK: Nirvana is when a person, characteristically an enlightened Buddhist monk, has spent all their karma and will no longer be reborn. One cannot attain nirvana while alive, though. The last stage in the attainment of nirvana, called parinirvana, happens only at the time of death. The Buddha himself is said to have realized nirvana when he achieved enlightenment at the age of 35. Although he destroyed the cause of future rebirth, he continued to live for another 45 years. When he died, he entered nirvana, never to be born again while Brahma Loka, the rebirth takes place.

……………………………………………………

FASTING BUDDHA

After reaching enlightenment at Bodhgaya, Buddha meditated and fasted for forty-nine days. Thus, showing him as an emaciated renouncer relates to his enlightenment and his status as a yogic ascetic who has ultimate control over his body). In Buddhism, fasting is considered a method of purification. Fasting in Buddhism is to develop control of one’s attachments so the mind can be freed to develop higher awareness. Also fasting can be done so that one restricts from a pleasure (food) and dedicate it to someone sick, in need or dying. Basically to restrict one’s body from the normal food intake is to develop discipline, awareness, self-control and even appreciation for all one has.

……………………………………………………

Yant Kru of Luang Phu Peuak, Wat King Kaeo

Yant Kru of Luang Phu Peuak, Wat King Kaeo is a formula of a Yant Na Metta and a Yant Lersi (Great Master Hermit) Cabalistic Writings which is best for Metta Maha Niyom (making people around you love you, be nice to you, and willing to support you for anything), Klawklad Plodpai (bringing safety, and pushing you away from all danger), Kongkraphan (making you invulnerable to all weapon attack), and anything you wish for.

……………………………………………………

Luang Phu Peuak of Wat King Kaeo, Aug 12, BE 2412 to Mar 29, BE 2501

Luang Phu Peuak of Wat King Kaeo is one of holy guru monks of Thailand, the amulets made by Luang Phu Peuak are very powerful, and best for Metta Maha Niyom (making people around you love you, be nice to you, and willing to support you for anything), Klawklad Plodpai (bringing safety, and pushing you away from all danger), Kongkraphan (making you invulnerable to all weapon attack), and anything you wish for. Luang Phu Peuak of Wat King Kaeo was also best at making Pong Pattamang Holy Powder, Yant Na Metta and Yant Lersi Cabalistic Writings.

Luang Phu Peuak of Wat King Kaeo was a disciple of Luang Phu Thong of Wat Ratchayotha (Wat Lat Bua Khao), Luang Phu Thong of Wat Ratchayotha was a junior class mate of Somdej Pra Buddhachan Toh of Wat Rakhang under the same Vipassana Meditation master, the Holy Luang Phu Sang of Wat Mani Chon Khan, the Pra Arahant Jet Pandin (the Arahant (one who achieved nirvana / spiritual enlightenment) who lived in the reigns of 7 Kings of Thailand). Luang Phu Peuak of Wat King Kaeo was a close alliance of Luang Phor Fug of Wat Bueng Thong Lang , Luang Phu Pann of Wat Saphan Sung, and Luang Phu Peuak of Wat Lat Phrao.

Luang Phu Peuak born Peuak Boonsukthong on August 12, BE 2412 (CE 1869) at Ban Klong Sam Rong, Samut Prakan Province. Peuak ordained as Buddhist Monk at the age of 21 at Wat King Kaeo, under the care of Luang Phu Thong of Wat Ratchayotha, and Pra Archan Im, the abbot of Wat King Kaeo. Luang Phu Peuak stayed at Wat King Kaeo til the year BE 2442 at the age of 30, Luang Phu Peuak was promoted to the abbot of Wat King Kaeo, and Luang Phu Peuak passed away on March 27, BE 2501 (CE 1958) at the age of 88, 67 years in monastery, and 59 years as an abbot of Wat King Kaeo.

……………………………………………………

Luang Phu Toh of Wat Pradu Chimphli

Luang Phu Toh of Wat Pradu Chimphli, or official name of Chao Khun Prarachsangwara Bhimonda, was a local of Bangkontee district, Samutsongkram province.He was born on March 27 B.E.2430 to the family of Mr.Loy and Mrs.Tub Ruttanakon, who had another child named Mr.Chuey, the younger brother of Luang Phu Toh.

By the time he was 13, both parents had passed away, and Luang Phor Kaew, a relative, moved him away to stay at Wat Pradu Chimphli, where he was educated by Luang Phu Suek, the then abbot of the temple. At the age 17, he was ordained as a novice, but unfortunately a day after, Luang Phu Suek passed away.

As a result Mr.Klai and Mrs.Pun, Luang Phu Suek’s relatives, decided they would do all they could to support Luang Phu Toh until he was 20, at which time he was ordained as a monk by Luang Phu Saeng (Phra Kru Sammana Tamsamahtahn) of Wat Paknam, at 3.30 PM., on July 16, B.E.2540. Also present as a preceptor was Phra Kru TammawiRat (Chei) Wat GumPaeng. At the time he was renamed as “Intasuwanno”. after Luang Phu Suek, by the son of Mr Klai, Luang Phu Kum the Abbot of Wat Praduchimplee

Luang Phu Toh was a dedicated and merciful monk, highly respected by the locals, but he wanted to learn more about Lord Buddha’s Dharma and magic sciences. Because of his desire and quest for knowledge he actually moved away to Wat Bhoti in Bangkok. It was not long however that the locals pleaded for his return. When Luang Phu Toh had reached the age of 26, Luang Phu Kum resigned from his position at the temple, and Luang Phu Toh succeeded him. In fact he remained Abbot until his death at the age of 68 on March 5, B.E.2524. Luang Phor Toh himself was succeeded by Luang Phu Virojana-kittikun, who remains the current Abbot at the age of 94

Luang Phu Toh was so interested in magic sciences that even before he was ordained as a monk he was learning from Luang Phor Phromma who was then the Abbot of Wat Pradu Chimphli. After Luang Phu Phromma had passed away, Luang Phu Toh studied under many senior monks such as Luang Phor Roong of Wat Takrabue, Samutsakorn province, Luang Phu Nium of Wat Noi, Supanburi province, Luang Phor Pum Wat Bangklo, Bangkok. Moreover, Luang Por Pan of Wat Bangnomko, Ayudhaya province, had introduced Luang Phu Toh to Luang Phor Nong, from whom he learned a lot of magic sciences, so much so that Luang Phu Toh regarded him as his principal.

When Luang Phu Toh began to join the Buddhist ceremonies he also attempted to seek further knowledge. A close follower of Luang Phu Toh revealed that every time he was invited to a ceremony he would touch the sacred thread, and incredibly would know the strength of the magic power, if the power was strong he would enquire as to who created the sacred thread in order to learn further. Luang Phor Toh was involved in many mass chanting ceremonies such as Phra Somdej Luang Phor Pae Roon Rahk chanting at Wat Suthat in BE 2494, 25 Puttawat chanting in BE 2500, Phra Luang Phor Thuad chanting at Wat Prasat in BE 2506, Phra Somdej 09 chanting at Wat Bankhunprom in BE2509, Phra Somdej Roy Pee chanting at Wat Rakang in BE 2515. Even as Abbot of the temple, Luang Phu Toh would spend much time traveling to seek the knowledge that he desired. Beside the lay people, the 9th or the present King of Thailand and the royal family respected Luang Phu Toh very much. One can see from many photographs of the royal family taken with Luang Phu Toh.

In BE2463, Luang Phu Toh chanted the first batch of amulets made of Neua Phong. The most popular Pim from this batch is the Pra Somdej Ka Toh , which is very rare and expensive now. Since that time, Luang Phu Toh continued to chant many batches of amulets of many types, such as Phra Pidta, Somdej, Roop Meuan and Rians etc. All Luang Phu Toh’s amulets are very well-proven to be able to protect people from accidents and hardship.

……………………………………………………

DIMENSION: 6.90 cm long / 3.30 cm wide / 0.80 cm thick

……………………………………………………

item # K22C54

Price: price upon request, pls PM and/or email us [email protected]

100% GENUINE WITH 365 DAYS FULL REFUND WARRANTY

Item location: Hong Kong, SAR

Ships to: Worldwide

Delivery: Estimated 7 days handling time after receipt of cleared payment. Please allow additional time if international delivery is subject to customs processing.

Shipping: FREE Thailandpost International registered mail. International items may be subject to customs processing and additional charges.

Payments: PayPal / Western Union / MoneyGram /maybank2u.com / DBS iBanking / Wechat Pay / Alipay / INSTAREM / PromptPay International / Remitly / PAYNOW

*************************************

0 notes

Text

The Tibetan term for Samatha is

"Zhi gnas," which translates to "Calm." Samatha

Meditation is a practice that cultivates the ability to attain single-pointed equipoise or perfect concentration of the mind. This meditation is typically carried out in a serene setting, employing the "Seven-point meditation posture of Vairochana." Within the thangka, nine progressive stages of mental development are depicted, symbolizing the journey. These stages are guided by the "Six powers" of Study, Contemplation, Memory, Comprehension, Diligence, and Perfection. A burning flame is situated alongside, representing the level of effort required for the development of both mindful recollection and understanding. This flame gradually diminishes as one progresses through each of the nine meditation stages.

#buddha#buddhism#buddhist#dharma#sangha#mahayana#zen#milarepa#tibetan buddhism#thich nhat hanh#padmasambhava#inner peace#four noble truths#tantra#green tara#Guru Rinpoche#Longchenpa#dalai láma#dhamma#Dzogchen#Bodhisattva#buddha samantabhadra#medicine buddha

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meditation – Was ist das? Einführung und Nutzen

Meditation ist ein Begriff, der eine Vielzahl von Techniken umfasst, die in verschiedenen Religionen und Kulturen auf der ganzen Welt praktiziert werden. Insbesondere im Hinduismus und Buddhismus sind Meditationstechniken tief verwurzelt. Es gibt jedoch keine einheitliche Definition von Meditation, da sie in unterschiedlichen Traditionen verschiedene Formen annehmen kann.