#artist: berliner philharmoniker

Text

Tracklist:

The Planets Op. 32: 1. Mars, The Bringer Of War • 2. Venus, The Bringer Of Peace • 3. Mercury, The Winged Messenger • 4. Jupiter, The Bringer Of Jollity • 5. Saturn, The Bringer Of Old Age • 6. Uranus, The Magician • 7. Neptune, The Mystic

Spotify ♪ Youtube

#hyltta-polls#polls#artist: gustav holst#artist: berliner philharmoniker#artist: herbert von karajan#language: instrumental#decade: 1980s#Modern Classical#Tone Poem#Romanticism#Impressionism

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rewind the Tape —Episode 1

Art of the episode

During our rewatch, we took note of the art shown and mentioned in the pilot, and we wanted to share. Did we miss any? Do you have any thoughts about how these references could be interpreted? How do you think Armand and Louis go about picking the art for their penthouse in Dubai?

The Fall of the Rebel Angels

Peter Bruegel the Elder, 1562

This painting is featured in the Interview with the Vampire book, and it was important enough to be included in the draft pilot script!

Bruegel the Elder was among the most significant Dutch and Flemish Renaissance artists. He was a painter and print-maker, known for his landscapes and peasant scenes.

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion

Francis Bacon, 1944

Bacon was an Irish figurative painter, known for his raw, unsettling imagery and a number of triptychs and diptychs among his work. At a time when being gay was a criminal offense, Bacon was open about his sexuality, and was cast out by his family at 16 for this reason. He destroyed many of his early works, but about 590 still survive.

The Tate, where these paintings are displayed, says this about the work: "Francis Bacon titled this work after the figures often featured in Christian paintings witnessing the death of Jesus. But he said the creatures represented the avenging Furies from Greek mythology. The Furies punish those who go against the natural order. In Aeschylus’s tragedy The Eumenides, for example, they pursue a man who has murdered his mother. Bacon first exhibited this painting in April 1945, towards the end of the Second World War. For some, it reflects the horror of the war and the Holocaust in a world lacking guiding principles."

Strawberries and Cream

Raphaelle Peale, 1816

Peale is considered to have been the first professional American painter of still-life. [Identified by @diasdelfuego.]

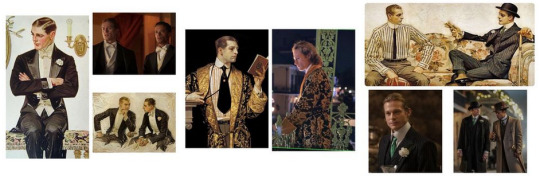

Outfits inspired by J.C. Leyendecker

Leyendecker was one of the most prominent and commercially successful freelance artists in the U.S. He studied in France, and was a pioneer of the Art Deco illustration.

Leyendecker's model, Charles Beach, was also his lover of five decades. You can read costume designer Carol Cutshall's thoughts on these outfits on her Instagram.

Iolanta

Pyotr Tchaikovsky, 1892

The opera Louis and Lestat go to was composed by Tchaikovsky, another gay artist. The play tells a story "in which love prevails, light shines for all, lies are no longer necessary and no one must fear punishment," as put by Susanne Stähr for the Berliner Philharmoniker.

On the Hunt or Captain Percy Williams On A Favorite Irish Hunter

Samuel Sidney, 1881

The unidentified painting on the right might be from the same hunting series, though we couldn't identify the exact one. There's also a taxidermy deer, ram, and piebald deer on the wall. [Identified by @vfevermillion.]

The Artist's Sister, Melanie

Egon Schiele, 1908

Schiele was an Austrian expressionist painter and protege of Gustav Klimt. Many of his portraits (self portraits and of others) were described as grotesque and disturbing. [Identified by @dwreader.]

A Stag at Sharkey's

George Wesley Bellows, 1909

Bellows was an American realist painter, known for his bold depictions of urban life in New York City. [Identified by @vfevermillion.]

Mildred-O Hat

Robert Henri, undated (likely 1890s)

Henri was an American painter who studied in Paris, where he learned from the Impressionists and determined to lead an even more dramatic revolt against American academic art. [Identified by @nicodelenfent, here.]

Starry night

Edvard Munch, 1893

Munch was a Norwegian painter, one of the best known figures of late 19th-century Symbolism and a great influence in German Expressionism in the early 20th century. His work dealt with psychological themes, and he personally struggled with mental illness. [Identified by @vfevermillion.]

If you spot or put a name to any other references, let us know if you'd like us to add them with credit to the post!

Starting tonight, we will be rewatching and discussing Episode 2, ...After the Phantoms of Your Former Self. We hope to see you there!

And, if you're just getting caught up, learn all about our group rewatch here ►

#louis de pointe du lac#daniel molloy#lestat de lioncourt#vampterview#interview with the vampire#iwtv#amc interview with the vampire#interview with the vampire amc#amc iwtv#iwtv amc#IWTVfanevents#rewind the tape#in throes of increasing wonder#analysis and meta#art of the episode

66 notes

·

View notes

Note

I deserve to be roasted for this (there’s a reason this is on anon) so do your worst:

Minutes: 174,378

Top Artists: Andrew Lloyd Webber, Berliner Philharmoniker, Phantom of the Opera Cast, Herbert von Karajan, Antonin Dvorak

Top 5 Songs: Various songs from Phantom of the Opera

Bud you already know how bad it is, do I even gotta say anything?

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top Artists — Medium Term (6 months)

Felbm

Radiohead

Bonnie "Prince" Billy

Kate Bush

Nick Drake

Midlake

Paul Simon

Simon & Garfunkel

Slowdive

Boards of Canada

Canary Room

The Beatles

Fionn Regan

Beach House

Leonard Cohen

hemlock

Vashti Bunyan

Clara Mann

Bob Dylan

The Smiths

ABBA

Grouper

David Bowie

The Clientele

Jessica Pratt

Olovson

Bill Callahan

Laura Marling

Rachel Grimes

Chet Baker

Belle and Sebastian

Sibylle Baier

Aldous Harding

Cocteau Twins

Acetone

Connan Mockasin

Fleetwood Mac

Cornelia Murr

John Martyn

Julie London

Sea Oleena

Sufjan Stevens

Meg Baird

Shannon Lay

Van Morrison

Pink Floyd

Caroline Says

Sun Kil Moon

Maxine Funke

Fairport Convention

that spotify stats page

Top Tracks — Long Term (years)

Calla — Canary Room

4 Lieder, Op. 27, TrV 170: IV. Morgen! — Richard Strauss, Jonas Kaufmann, Helmut Deutsch

6 Melodies, Op. 4 - 6 melodies, Op. 5: Allegretto — Fanny Mendelssohn, Beatrice Rauchs

Long Before Us — Rachel Grimes

Sandalwood I — Jonny Greenwood

Stabat Mater: 1. Stabat Mater — Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Emma Kirkby, James Bowman, Academy of Ancient Music, Christopher Hogwood

Thaïs / Act 2: Méditation — Jules Massenet, Joshua Bell, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Andrew Litton

Songs My Mother Taught Me, Op. 55 No. 4 — Antonín Dvořák, Alisa Weilerstein, Anna Polonsky

Elegy No. 1 in D Major — Giovanni Bottesini, Andrew Burashko, Joel Quarrington

The Carnival of the Animals, R. 125: XIII. The Swan (Arr. for Cello and Piano) — Camille Saint-Saëns, Yo-Yo Ma, Kathryn Stott

Julie With - 2004 Digital Remaster — Brian Eno

wallingford bossa — hemlock

Fantasiestücke, Op. 73: No. 1, Zart und mit Ausdruck — Robert Schumann, Sol Gabetta, Hélène Grimaud

By This River - 2004 Digital Remaster — Brian Eno

Just When You Need Yourself Most — Oberhofer

Gianni Schicchi: O mio babbino caro — Giacomo Puccini, Renée Fleming, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Sir Charles Mackerras

Bleecker Street — Simon & Garfunkel

House of Woodcock — Jonny Greenwood

Shaker — Acetone

All The Time — Acetone

Jazz Suite No. 2: VI. Waltz II — Dmitri Shostakovich, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Riccardo Chailly

Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade, Op. 35: II. The Kalendar Prince (Excerpt) — Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Riccardo Muti, Philadelphia Orchestra

Christine — Canary Room

Me at the Museum, You in the Wintergardens — Tiny Ruins

Valse sentimentale, Op. 51, No. 6 — Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Josef Sakonov, London Festival Orchestra

Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 73 "Emperor": II. Adagio un poco mosso — Ludwig van Beethoven, Wilhelm Kempff, Berliner Philharmoniker, Ferdinand Leitner

Deux Arabesques, L. 66, CD 74: I. Première Arabesque — Claude Debussy, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet

Green Bus — The Innocence Mission

Lucida — Thomas Bartlett

Introduction et Allegro, M. 46 — Maurice Ravel, Oxalys

Two Thousand and Seventeen — Four Tet

When It Rains — Felbm

Lake Effect — Canary Room

Candy Says — The Velvet Underground

Serenade for Strings in C Major, Op. 48, TH 48: II. Valse — Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Zagreb Philharmonic Orchestra, Dmitri Kitayenko

Schumann: Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6, Heft II: No. 14, Zart und singend — Robert Schumann, Jonathan Biss

Magnolia — J.J. Cale

day one — hemlock

Return From The Ice — Acetone

Requiem in D minor, K.626: 6. Benedictus — Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Anne Sofie von Otter, Barbara Bonney, Hans Peter Blochwitz, Willard White, English Baroque Soloists, John Eliot Gardiner

River — Terry Reid

Where Should I Meet You? — Canary Room

This Night Has Opened My Eyes - 2011 Remaster — The Smiths

Brother — Vashti Bunyan

Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007: I. Prélude — Johann Sebastian Bach, Yo-Yo Ma

Sweeten Your Eyes — The Clientele

Knickerbocker Holiday: September Song (Arr. by Paul Bateman) — Kurt Weill, Daniel Hope, Jacques Ammon, Zürcher Kammerorchester

Funicular — Felbm

Piano Sonata No. 12 in F Major, K. 332: II. Adagio — Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Jenő Jandó

Sensuela — Column

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#3 Woven Twist

Stitches: 30

Rows: 20

Rows in pattern: 8

Difficulty level: 3/10, it's pretty intuitive once you get going

Would I use it in a design: yes

Overall rating: 7/10

My Swatch:

Album: Shostakovich: Symphony No. 10 by Dmitri Shostakovich, performed by the Berliner Philharmoniker, conducted by Kirill Petrenko (2022)

Top descriptors that came to mind: unsettling, layered, depth, frenetic, waves

Where I got the recommendation: Spotify's "albums for today" section

Would I listen to it again: no

Cover: 3/10 bland but pretty

Intrigue in the artist: 5/10

Overall music rating: 4/10, it's well done but I don't care for it personally. Shostakovich isn't really my jam to begin with.

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

new cd!

Eternal City

Editions 013

cd+digital

Release date: January 8, 2024

Jason Kahn // electronics

Ulrich Krieger // tenor saxophone, contrabass clarinet, krummhorn

Three pieces spanning free improvisation, noise and extended saxophone technique by long-time collaborators Jason Kahn and Ulrich Krieger.

Edition of 200

Factory-pressed CD

Hand-painted covers on thick gray cardboard

CD duration 54.53

Tracks:

I (24.36)

II (16.49)

III (13.40)

Recorded by Ulrich Krieger on May 24, 2022 in Los Angeles.

Mix, mastering and cover design by Jason Kahn.

Label:

https://jasonkahn.net/editions

https://jasonkahn.bandcamp.com

Musicians:

Ulrich Krieger

As well as being respected composer in his own right, Krieger has worked with Lou Reed,LaMonte Young, Phill Niblock, Lee Ranaldo, John Duncan, Zbigniew Karkowski, Merzbow,Thomas Köner, DJ Olive, Christian Marclay, Kasper T Toeplitz, Antoine Beuger, RaduMalfatti, and many others. He studied saxophone, composition and electronic music at the University of the Arts Berlin and the Manhattan School of Music New York and performed with orchestras like the Berliner Philharmoniker, Deutsches Symphonie Orchester, Rundfunk-

Symphonie-Orchester Berlin and Ensemble Modern. Since 2007 he lives in Southern California, where he is associate professor for the composition faculty at the California Institute of the Arts in Los Angeles.

http://ulrich-krieger.de

Jason KahnSince moving to Europe from Los Angeles in 1990 Jason Kahn has been a fixture on the European improvised and experimental music scenes. Collaborations with a diverse array of artists, including Arnold Dreyblatt, Axel Dörner, Magda Mayas, Tony Buck, Olivia Block, Kevin Drumm, Steve Roden and many others. He lives in Zürich since 2000, where he is also active as a writer and visual artist.http://jasonkahn.net

1 note

·

View note

Text

actually the way berliner philharmoniker isnt even in my fave artists... great shock

1 note

·

View note

Text

Unbroken Melodies: The Enduring Quest for Music Preservation

Music is a transcendent art form, a vessel for human emotions, culture, and stories. It weaves the tapestry of our lives, reflecting the spirit of each era and the diversity of our world. However, the fleeting nature of music makes it a vulnerable treasure that can be lost to time. In this article, we will explore the imperative of music preservation and the innovative ways through which we are safeguarding these timeless melodies.

The Transience of Music

Music, like a passing breeze, fills our lives with its beauty, but it is equally brief. Traditional methods of preserving harmony, such as handwritten sheet music and early recordings, are susceptible to decay, threatening the very essence of the art form. Furthermore, oral traditions passed from generation to generation are at risk of disappearing as the knowledge holders age and modernization encroaches upon them.

Imagine the wisdom of indigenous cultures, whispered through generations in their musical traditions. Without proper documentation and preservation, these unique and culturally significant forms of music may vanish, taking centuries of history and meaning.

The Role of Music Archives and Libraries

Music archives and libraries stand as fortresses guarding the treasure trove of musical heritage. These institutions collect and curate sheet music, audio recordings, photographs, and personal documents of musicians. They act as guardians of our musical history, offering researchers, scholars, and the public access to a vast knowledge repository.

For instance, the Berliner Philharmoniker Digital Concert Hall provides access to thousands of live recordings, interviews, and documentaries, offering a digital sanctuary for classical music enthusiasts. By digitizing and cataloging these performances, the Digital Concert Hall ensures that the legacy of classical music remains vibrant.

International archives, like the National Sound Archive in India and the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP), contribute to the global effort to preserve musical heritage. By safeguarding recordings and compositions from around the world, they celebrate the cultural diversity of music.

Digitization: A Contemporary Shield

In the age of technology, digitization has emerged as a powerful tool for music preservation. By converting analog materials into digital formats, we create replicas that are less susceptible to deterioration. Digital archives are easily accessible, opening the gates of our musical heritage to a global audience.

Platforms like YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Music host vast collections of music, both old and new. These platforms not only preserve existing music but also enable contemporary artists to share their creations with the world.

The Internet has enabled collaborative music preservation projects like the Global Music Archive, which hosts thousands of songs from diverse cultures. These projects facilitate cross-cultural sharing and collaboration, preserving the beauty and diversity of world music.

Capturing Stories through Oral History

Beyond recordings and scores, the essence of music is found in the stories it tells. Interviews and oral history with musicians and musicologists offer invaluable insights into the context, evolution, and personal experiences tied to music.

The Alan Lomax Archive is a prime example of the importance of oral history. With a vast collection of interviews and field recordings, the archive provides an intimate look into the world of American folk music and the lives of those who created it. These interviews breathe life into the songs, connecting them to the human experience.

Preserving Endangered Musical Forms

Many unique musical traditions are endangered and threatened by societal changes, globalization, and shifting cultural dynamics. Initiatives like the Endangered Archives Programme support projects that document and preserve the musical traditions of marginalized and at-risk communities.

By funding these initiatives, the program ensures that endangered musical forms are not lost to history. It empowers communities to share and revive their traditions, preserving their cultural identity through music.

A Collective Responsibility

Preserving musical heritage is a collective responsibility for musicians, enthusiasts, and local communities. Musicians are the torchbearers of their musical traditions, passing on their knowledge and skills to the next generation. Enthusiasts play a vital role by supporting local musicians and participating in cultural events celebrating traditional music.

Local communities are often the primary stewards of their musical heritage. Collaborative projects that involve and respect local knowledge are vital for the survival of unique musical forms.

Music preservation is a duty that transcends generations. Whether through archives, digitization, oral history, or community involvement, we must protect our musical legacy. Music is the soul's expression, and its preservation ensures that the stories and emotions of our ancestors continue to inspire and resonate with future generations. It's an unbroken melody, an eternal gift to the world.

0 notes

Text

Whimsical Adventures

~by Arya Tadepalli

Deciding to apply for the Oxford Summer Study Abroad program might be one of the best decisions I have made in college. Not only did I learn a lot about the world and was able to embrace different cultures, I also learned a lot about myself along the way as cheesy as that sounds.

I was part of Group 2 (the best group) and our itinerary was as follows: we took a flight from Atlanta to Amsterdam, Netherlands and then another flight to land in our first city Berlin, Germany. From Berlin we bussed to Leipzig, Germany stopping at Wittenberg on the way for lunch. After Leipzig we bussed to Prague, Czech Republic and stopped at Dresden, Germany for lunch. After Prague we went to Vienna, Austria stopping at Brno, Czech Republic on the way. From Vienna we stopped at a cute cabin hotel in the Alps for lunch before going to Lido right outside of Venice, Italy. From Venice we went to Rome, Italy with a quick stop at an Autogrill.

Side note: I am a huuuuuuuuge dog person and every time I saw a dog on this trip I would always squeal and point and say “DOG!” much to the embarrassment of anyone around me. At this Autogrill stop, which is basically what truck stops are called in Italy, I saw this beautiful German Shepherd. I had seen many dogs on the trip, but even with my two years of learning German in school I was not comfortable enough to go up to the dog owner to ask to pet their dog. However, something came over me when I saw this German Shepherd and people speak a lot more english in Italy so I just went up to the owner right before getting on the bus and asked to pet their dog. When they said yes I just started the usual small talk asking what their dog’s name is and how old they are etc. The owner said their dog’s name was Arya!! I then asked the owner how they spelled that name and they said, “A. R. Gamma. A.” I got so excited I said, “Wait! That is my name!” and I even pulled out my drivers license and pointed to my name to show the exact same spelling. Apparently in Italy, they do not have the letter Y so we got over the language barrier by gesturing the letters. Here is a picture of Arya squared.

Going back to the itinerary, when we were in Rome we went to the Vatican City for a day. Then, after Rome, we stopped at Montepulciano in Tuscany for lunch before continuing to Florence, Italy. Florence was the longest city of the travel portion for us and our schedule made it so that we had a half day for independent activities where a majority of us visiting the leaning tower of Pisa and an entire day for independent activities where many of us went to Monterosso in Cinque Terre for the day. From Florence we spent a night in Chamonix, France before leaving for Paris, France the next day. Paris was our last city of the travel portion so we ferried to Oxford, UK after.

I was not sure if I would enjoy the travel portion classes as much because I am more of an outdoorsy person instead of a gallery person, but I now realize those two are not mutually exclusive. I had such a great time learning about the art pieces and artists and then going to the gallery the very same day and seeing the original works of art in person. We went to a variety of famous galleries all over Europe from the Louvre in Paris to the Uffizi and Accademia Galleries in Florence to the Gemaldegalerie in Germany, they were all such cool experiences. The music class was just as fun because we would learn about different aspects of music and then go to a concert in a few cities. There were a variety of concerts that we went to. Our first concert was in Berlin where we saw the Berliner Philharmoniker perform the Turangalila Symphony which is a modern piece. Our second concert was at the National Theatre in Prague where we watched the Czech National Ballet and the National Theatre Orchestra present a spectacular performance of the “Onegin” Ballet which is a more Romantic piece. Our third concert was at the Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna where we watched the Schloss Schönbrunn Orchestra play Mozart, Haydn, J. Strauss, O. Strauss, and Lehár pieces which are more part of the Classical time period. The fourth concert was in the San Vidal Church in Venice, Italy where the Venetian Interpreters played Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons as well as Vivalid’s violin concerto and cello concerto. The last concert was in the Sunset underground part of the Sunset/Sunside Club in Paris, France where Larry Crockett and the Funky Cherokees performed jazz. Each gallery and concert made me appreciate the arts so much more and the talent and dedication that goes into every brush stroke or bow movement.

This trip also opened my eyes to how oblivious American tourists are, especially on public transportation. We are generally the biggest and loudest group, pretty clumsy especially the first day we are in the city, tend to hold people up the most when getting on or off buses and trains, and do not stay to the right side of the escalator to let people pass on the left. But we learned from our mistakes and tried to amend them later on in the travel portion. I mostly learned that I like traveling in smaller groups though. One of my friends and I had a plan to watch the sunrise in every city we traveled to and those were genuinely some of my favorite memories from the trip because it would usually just be the two of us planning where to watch the sunrise and traveling public transportation to get there and enjoy the views. This started during the very first city in Berlin when we ran from our hotel to the Brandenburg Gate for some pretty views.

Leipzig was the only city that we missed. In Prague we watched the sunrise from the Charles bridge. In Vienna we started near the Prater amusement park and walked around the city watching the sun rise. In Venice we watched the sunrise from the beach our hotel was right next to. In Florence we watched the sunrise from a park near our hotel. In Chamonix we hiked at 3AM up the French Alps near Mont Blanc doing a bunch of switchbacks below the Ski Lift that was shut off for the night.

In Paris my sunrise buddy fell asleep on me, but I was determined to maintain the streak especially since Paris was our last city of the travel portion so I mustered up the courage to travel Paris public transportation on my own at 5AM and I went to the Trocadero Square. This was a huge milestone for me because I had never traveled on my own before other than a few city exploration walks in well lit populated places and this experience was a culmination of all the tricks I had learned during traveling and Paris is notorious for pickpocketing so I had to be aware of my surroundings at all times.

I was able to apply everything I learned to my weekend trips I took during the Oxford portion. The first weekend we were told to stay in Oxford so I explored the town. The second weekend I went to Dublin. The third weekend I went to Amsterdam, Brussels, and Brugge. The fourth weekend I went to Wales and London, and the fifth weekend I went to Edinburgh. My favorite place during the Oxford portion was actually a 30 minute walk from Mansfield college and is called Port Meadow. I made it a point to go there every Sunday right after dinner to see the wild horses and cows and enjoy the sunset. It was such a magical place for me especially when the horses would come up to you to be petted because it made me feel like the chosen one.

All in all, the Oxford Study Abroad experience taught me a lot about being a considerate and respectful traveler and gave me the opportunity to immerse myself in the surrounding culture. It also gave me more confidence as a solo traveler and confidence in my ability to handle myself in general under various different circumstances.

0 notes

Note

🎼!!! omg i love this

Mozart’s last piano concerto….. I like this for you because it has the right balance of luminous strings and a sensitivity at the minor key second theme of the first movement. This concerto sees Mozart in his artistic maturity, giving the concerto a distinct character and allowing for experiments in style. You may find some of the upcoming Romantic era of music in his experimentations here. Both the tone and form of this concerto reminded me of you because of how your graphics are so distinct, creative, and polished! It speaks to the sort of artistic maturity Mozart had reached at this point and was still looking ahead to.

I chose Daniel Barenboim’s recording with the Berliner Philharmoniker in the late 1980s because it’s just pure class. I love the Berliner Philharmoniker and Barenboim is a known quantity when it comes to Mozart. He has a virtuosic touch but also an understanding of the music—in a way that holds depth. You can actually hear Barenboim talk about this piano concerto for five minutes!

send me a 🎼 for a mozart recording

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Oscars 2023

This year, I managed to watch all but one of the Oscar-nominated films before the ceremony, missing only the Documentary Short How Do You Measure a Year, although if the director's film from last year is anything to go by, this was no great loss.

They were again an excellent set of films, and it was a very entertaining project to undertake once again. There's a reason I try to do this every year, even though it sometimes, during the month of February, feels like millstone around my neck.

As usual, I'll count down the films from my favourite to least-favourite, with separate lists for the feature films and the shorts. I'll then fill out my Oscars ballot below, and I'm glad to announce that due to my 1993 short film Jez & His Brother Play Tennis And Struggle With Turning Off The Camera I've been granted membership of the Academy, so this year these votes count.

Let's get into it.

1. Tár

Directed by Todd Field

A gripping, compelling and profound film from Todd Field and Cate Blanchett, following Lydia Tár, renowned principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonik (Blanchett), as she prepares to record and perform Mahler's 5th Symphony—a piece that has eluded her throughout her career. It's also about a great deal more than that: with a deep exploration of power, abuse and self-fulfilment.

While it doesn't explicitly play out as a thriller, it is a psychologically intense film. Throughout the early stages we see glimpses of Tár photographed surreptitiously through a phone camera, superimposed with vaguely threatening texts. She receives suspicious gifts which she hastily disposes of. She takes drugs for anxiety prescribed for her wife. But the film never leads us down the obvious path here: we are given snippets of an incomplete picture, like fragments of a rehearsal, before Field allows the full orchestra to blast us in the latter third.

There is so much that is virtuosic about this film—it is a career high performance from Blanchett, who is utterly thrilling and potent on screen. She commands our attention in way that almost feels against our will—she demands it; we comply. And it's often not easy being face-to-face with that level of intensity.

The script from Todd Field is honestly incredible. There is an astonishing amount of detail and craft to it. The way the film unfolds is mesmerising in itself, but when you look backwards for all the links, you see what a complex beast it is. It's also the sort of film which would be fascinating to rewatch even soon after seeing it for the first time—if you can face it. This is true of both the sequences of great emotional upheaval, but also the clever and subtle characterisation which marks an extended opening sequence where Tár is being interviewed for the New Yorker. It could be extremely dry, but it's anything but: it's engaging, but more than that it provides us with an immediately fascinating portrait of the main character.

I haven't even spoken about some of the other wonderful elements to this film. Nina Hoss as Tár's wife (and concertmaster of the Philharmonik—a stark fact later in the film) is also incredible in a more subtle but no less complex role. The music and sound design is sublime—and not just because of the moments we spend with Mahler's 5th Symphony. The choices throughout are careful and perfectly evocative—right down to the Besomorph track which plays over the credits.

It only drops half a star because of the slight hiccup of the very final scene, which some others may have no problem with. But aside from that, it was a phenomenal experience. Despite it being among some strong competitors, Tár is without equal in the Oscars this year.

2. All the Beauty and the Bloodshed

Directed by Laura Poitras

A truly remarkable work of documentary, that sees stalwart of the form Laura Poitras reach new heights. We focus in on Nan Goldin: photographic artist, activist and former addict. It is in these latter two capacities that she takes up a fight against pharmaceutical giant Purdue. Furthermore, she levels her sights on Purdue's owners the Sackler family—well-known in the art world for their extensive philanthropy—for their profiteering off the opioid crisis in America.

It is a wonderfully gripping and thematically manifold documentary. We see Goldin, and her activist group P.A.I.N., target art institutions that have accepted donations from the Sacklers (in particular those who immortalise the Sackler name). We see the group's legal fight against Perdue, and their activism to destigmatise drug use.

But far more broadly, we take a deep and sometimes unsettling look into the life of our protagonist, told through her own photographs. These are uncommonly stark, candid, confronting and beautiful. Her subjects are the disenfranchised, the marginalised, the queers, the drug-users, the sex workers. But they come with a sense of intimacy and insight that's draws you in. These are the people who make up a community. Goldin shows us her world: These are the people who I live with, laugh with. These are the people I fuck.

It is from this sense of community and solidarity that the film gets its power. One of Goldin's subjects is the AIDS crisis of the 80s and 90s—a period she and her community lived through with immense pain. It decimated their ranks and showed starkly how pitiless a government and its institutions can be. We move from the acute intimacy of her photographic portraits, and their sense of belonging, to a sense of being blown apart and scattered like shreds. You understand why Goldin, now, is so fervent that this not happen again.

We also delve into the origins of who Goldin was. In particular, her relationship with her older sister who was repeatedly institutionalised by her parents. These same parents end up forcing the young Nan into foster care, with an unloving admission that they never wanted children anyway.

It's delicate but soul-clenching how Poitras weaves this tale together in non-linear fashion. It becomes a profound portrait of someone's life, in a way that I've rarely been done before. And despite everything, it's a celebration too. It's a celebration done with glorious, no-fucks-given style. It's laying bare the agony and affliction of a life and showing us: "that's what life, what real living is built on. That's what life is".

3. Everything Everywhere All at Once

Directed by Daniel Scheinert & Daniel Kwan

Another trip into the multiverse—the multiverse we actually want to visit again—with Michelle Yeoh as our favourite coin-laundry operator who may well have the fate of existence itself in her sausage-fingered hands.

It took me two trips through Everything Everywhere All at Once to really appreciate it. Sure, the first time I had a whole heap of fun. I related to the thematic content about family, and the lure of the void when the universe itself seems meaningless. I enjoyed the visuals and the costuming and the spectacle. But I also had trouble shutting off the analytical part of my brain which was trying to work out the logistics of dimension hopping, as Waymond Wang frantically explains it piece by piece, and we're then hurled from dimension to dimension.

The solution, you would think, is to not think. Let the mechanics wash over you and enjoy it for its story. Don't look too closely at the ideas of stochastic improbability that allow for jumping 'verses, lest they fall apart. In the meantime,you have a hell of a ride to jump on.

In reality though, seeing it a second time allowed the logic of the world to settle down. It may not feel true, or real, but the internals of the film have a neat consistency that allowed me to relax. And once I relaxed I realised what a truly wonderful film this was when you just allow yourself to have fun. Taking a breath was what was needed, even though the film gives you very few opportunities for that.

Michelle Yeoh is, of course, wonderful as Evelyn, and the second time around I saw the immense charm of Ke Huy Quan as Waymond—the first time, he was the source of too much consternation on my part. There's an intensity to the performances, but these characters have the stature to deliver emotional impact where required as well.

Moreover, the second time around, I much more appreciated the utility of the absurd as a plot mechanic. Evelyn reaches more distant universes, branching off from our own long, long ago—Evenlyn is, well, Michelle Yeoh, martial arts film superstar, humans have fingers shaped like long hotdogs and play piano with their toes, a teppanyaki chef is controlled by a sentient raccoon. Statistically more-improbable actions are required for longer jumps, so characters act erratically, comically, launching themselves over a wall and onto a buttplug-shaped award statue. It's bizarre, but by the second viewing, the film earns it, and it makes internal sense.

I've not even got into the richness of the editing and the cinematography. There's a wonderful nod to the films of Wong Kar-Wai, expressing the regret of missed opportunities in love, for example. It's all it needs to be technically to live up to its frankly astonishing conception.

I could go on. Suffice it to say that it's a film that holds up as a spectacle, but rewards another viewing for all the details you missed the first time around: and I guarantee there will be some of those. What is better, though, is when you're not frantically trying to keep up, you can see it much more clearly. And there's significant emotional and thematic depth. That's what truly makes it a good film.

4. Close

Directed by Lukas Dhont

A truly intimate and heartbreaking film which follows two 13-year-old boys, Léo (Eden Dambrine) and Rémi (Gustav De Waele) who share a deep friendship. When the two start high school, peer pressure and the perceptions of their relationship cause Léo to start pushing Rémi away.

It's a really exceptional film, told with sparse narrative from meaningful but often quite transient moments—a discussion in the class room about the kids' hobbies, a shot of Rémi playing the oboe, the two racing their bikes on the way to school. It's that style of filmmaking which draws you in by making you pay attention to the clues, and when it has you right in close it punches you hard.

It's also shot mostly in claustrophobic close-ups, usually of Léo's face, so we feel everything he goes through very profoundly. It's a remarkable performance from a young actor who has so much to do, and nowhere to hide. The film really rides on Dambrine, and his output is nothing less than extraordinary.

It's also judiciously edited. It runs at well less than two hours, which means that it feels compact and coherent—it makes its point with room to breathe, but it doesn't overstay its welcome or ever feel like it's dragging.

Overall, I really loved it, and it was one of the films over the past year that has had the most emotional impact for me. I look forward to seeing what more Lukas Dhont has to offer.

5. Glass Onion

Directed by Rian Johnson

I dearly loved Knives Out; I spent my first time watching it with hearts in my eyes, absolutely rapt and delighted with every trope and subversion. I have to admit there was a little part of me which was apprehensive of whether Rian Johnson and Daniel Craig could recapture the magic with this sequel. It took very little time for me to realise that I could relax, that this was a film to equal the original. Before long I'd left behind the part of me that wants to analyse or unravel it as a film. It was a relief to know I could just enjoy it.

And enjoy it I did. This was another film filled with exactly the same kind of loving deconstruction of the whodunnit, and filled with wonderfully captivating characters. Daniel Craig as Benoit Blanc is of course wonderful again—perhaps more so as we get to learn more about him as a character, including his flaws and idiosyncrasies. But he is aided by another excellent ensemble: Janelle Monae in particular is stunningly good; electric and magnetic on screen as she works through her character's various modes. Edward Norton plays Musk-esque billionare Miles Bron with a charismatic smarminess, Kate Hudson & Kathryn Hahn are both thrillingly repellent, and Dave Bautista has a really wonderful time as an obnoxious right-wing Twitch streamer.

On top of this, Johnson has provided us with yet another thrillingly compelling mystery, which, like Knives Out before us, manages to waylay us at numerous points (including providing the most wonderfully banal red-herring I think I've ever seen). It means that (I'm sure) rewatching the film will be as much of a treat as watching it. This, combined with some wonderfully leftfield production choices (the Philip Glass "bong" was just a constant delight), means that this will stand apart as another glowing entry in Johnson's oeuvre.

Where this perhaps even exceeds its predecessor is in the way it sharpens its satire. There's a perceptive and timely skewering of the billionaire class in this film which gives it much more heft than you would believe for such an thrillingly entertaining story. It improves significantly on the general sense of "wealth and entitlement makes you bad" of its predecessor to take some very pointed jabs at particular instances of conspicuous excess.

But of course, you can also just ignore this and go along for the ride. I'm so pleased we've got at least one more Blanc mystery coming our way, and based on the success of these, there's probably a long future for the franchise. I only hope it doesn't rob us of whatever brilliant new idea Rian Johnson would have come up with next.

6. Aftersun

Directed by Charlotte Wells

I've taken my time in writing up this film, because it really needed some time to percolate and settle in my brain. In a rather impressionistic style, it recounts a holiday in Türkiye for 11-year-old Sophie (Frankie Corio) and her soon-to-be 30-year-old father Calum (Paul Mescal). Told partially through snippets of home-video footage, which get woven in with the main narrative, it also has flash-forwards to Sophie as an adult of Calum's age, and dimly lit shots of Calum dancing at a kind of dark rave.

The film has a deeply felt sense of melancholy to it—a sense that the bright sunny beaches of these foreign climes are a garish cover for something darker. Calum is determined to be a good father, and has a strong relationship with his daughter. And yet there's a strong sense of distraction to him—something he can never quite remove, but that he's good as masking. It's a fine, and remarkably subtle performance from Mescal to achieve this.

The form and the narrative also helps—it's told in sometimes contextless snippets, much like how you might play back an old video tape of your own holiday. This allows director Charlotte Wells to focus on little interactions between Calum and Sophie in isolation, to introduce something that seems irrelevant but which takes on poignancy as the film progresses.

I'll admit that it wasn't until right at the end that the wave of all these little pieces eventually enveloped me, but when it did I was crushed by their accumulation. It's a really quite masterfully done thing—Sophie looking back on this time with her father; the sense of melancholia; adult Sophie's new baby; the dancing in the rave—they combine to form a powerful final realisation.

Overall, it was a film that really required some thought, and a little bit of reflection. But once I had that I realised that it was likely one of the most masterful films of the year.

7. The Quiet Girl

Directed by Colm Bairéad

A very subdued and, yes, quiet film about a young girl who is sent away from her family to live with distant relatives for the summer, while her mother has her next baby. There's a fairly alarmingly insouciance from her parents who discard her into the arms of strangers, and the naturally shy Cáit is even more wary of her new surroundings.

But over time, we learn gradually more about the couple who take her in. We learn (or suspect) more about Cáit's regular home life, and we start to see something that might be a better life for her.

It's very much a film that doesn't give you a lot of information—I love this mode of filmmaking, where things are conveyed with a look, with a word said or unsaid, with a little detail in a character's dress, or the way they hide food for later, when there may not be food to be had. I find it wonderfully engaging, because you're constantly on the lookout for the next clue, and as a result you get fully engrossed in the story.

The newcomer Catherine Clinch is wonderfully understated as Cáit, and manages to hold the whole film around her—it's a performance that allows the climax to have maximal impact because of all the work that was done before it. Similarly good are Carrie Crowley and Andrew Bennett as the Matthew & Marilla pair who take her in.

It's probably not a film for everyone—but if you like sparse, deliberate and ultimately quite devastating filmmaking, it is certainly one I'd recommend.

8. Top Gun: Maverick

Directed by Joseph Kosinski

I think it's fair to say I was deeply skeptical of this film. Top Gun, for all of its impact at the time of its release, was not the kind of film that was calling out to be revisited, and didn't have the depth of character and world-building to make another visit more than a nostalgia trip. Moreover, there is undoubtedly a role for this film to play in the insidious propaganda of "war and glory", and of the US military being the righteous force for good in the world.

But if you can put all of this aside: as a piece of cinema it is a deeply successful one. And in almost all ways it very much outstrips its predecessor.

For a start, there's something far more interesting about Maverick's character in this one. He has had a long career as a test-pilot; always with something to prove, always with an oppositional attitude that has stopped his career progression. When he's given one last shot as an instructor at the Top Gun academy, he comes in as a much richer individual.

It would be easy to squander this potential though by box-ticking references to the previous film: instead, we are thrown into a far more nuanced world coloured by history and interpersonal conflict. Rooster (Miles Teller) is one of Maverick's students, and the son of Goose, whose death Maverick still feels responsible for. Iceman (Val Kilmer) is now the naval commander who has shielded Maverick's career, but is fighting a life-ending illness. Maverick connects with an old flame, but does so with a lifetime of experience behind him. It's all far more interesting than it had any right to be.

Mostly, though, this was a fantastic example of a style of film-making that has been largely superseded by effects and super-heroes. There is something thrillingly real about the stakes here—this isn't about the destruction of the known universe: it's about a man with a mission and his ability to do it against the odds. We care not because we are navy fighter pilots, but because it's an analog for something we face, and something we care about.

It's really wonderfully shot as well. It no doubt has a great deal of CGI to it, but it also has a huge amount of genuine heart-thrumming action sequences that are shot using live aircraft. There's something that connected me to it in a much more physical way, and it was far more thrilling as a result.

Overall, I genuinely fully enjoyed this film, and that was with a lot of psychic barriers that I'd thrown up before I started watching it. It was honestly joyful that my skeptical expression gradually lessened and eventually turned into rapt entertainment. It's very good film-making.

9. The Fabelmans

Directed by Steven Spielberg

I was pleasantly surprised by this film. From Steven Spielberg, based on his own childhood and family, and in particular focusing on his love of movie making, it has the leaden weight of "Oscar bait" hanging from its presumably elongated neck. But in fact it was a remarkably engaging film for its extended running time, and for all of its introspection.

We follow Sam Fabelman (the Spielberg analogue, portrayed by Gabriel LaBelle) as he and his family move across the United States following his engineer father (Paul Dano). Accompanying them is Sam's mother Mitzi (Michelle Williams) and his father's friend "Uncle" Benny (Seth Rogen). Sam develops a love for making and editing 8mm films with help from his friends, and faces the challenges of being a Jew in a sometimes anti-Semitic society.

It would be too easy to say this is the film that Spielberg has been waiting his whole career to make. And it's not that. But he's astute enough to realise that there's a good story in the telling of his life, and he engaged the right people to help him do it. Tony Kushner co-authors the script with Spielberg, John Williams writes the score. He's assembled a genuinely excellent cast, with the standouts being Michelle Williams as Mitzi, and amusing one-shot cameos from Judd Hirsch and David Lynch. LaBelle is also a workhorse, having to propel most of the film along its length.

And there's good drama extracted from what could have been anyone's family history. There's nothing all that remarkable about the story itself, but in the telling there's a really good understanding of how to keep an audience engaged and entertained. There's something charismatic about everyone on screen, even as they're showing their faults and humanity. It's a delicate thing to get right.

I really think we're seeing a resurgence from Spielberg in his latter career. As much as this film might be seen as navel-gazing from him, he's honestly manage to craft something worthwhile and universal from something quite personal. Moreover he's at a stage where he's earned the ability and the right to do that.

10. RRR

Directed by S. S. Rajamouli

A wonderfully joyous, and undeniably bananas piece of Tollywood filmmaking, RRR is an epic that ties together friendship, betrayal and the fight for Indian independence. We follow two historical figures of Indian resistance, Komaram Bheem, and Rama Raju, imagining what it would have been like if they were best buddies. Bheem is in Delhi to rescue a child from his village, stolen by the frankly evil English governor and his wife, while Raju is an undercover police officer trying to stop him. For various reasons, neither of them know this about the other, and they end up effectively falling in love. It's honestly quite sweet. Then come the twists, revealed in typically melodramatic fashion.

For all of this, it does feel like a somewhat simple film. The plot is in many ways straightforward, and it's not trying to be a film with some deep, fundamental meditations on the human spirit.

This is a film designed to be about watching your heroes on screen just be badass and kick some butt. There are some frankly wild set pieces in this, including the introduction to Raju, where he singlehandedly fights an entirely rampaging mob in his search for a criminal, a wonderful musical number (set to the song which is up for Best Original Song at the Oscars) where Raju and Bheem have to out-dance those rich, snobby English, and a jawdroppingly bonkers scene where the two use a menagerie of captured wild animals in a plot to create chaos in the governor's mansion.

It's just a film that can do that. It has no qualms about absolutely suspending believability for the sake of spectacle; it goes as big as it can and then just goes a little bit bigger to tip it over into the ridiculous. It makes it, in so many ways, so stupid, but it's also remarkably freeing for the audience. You might want to pull it apart, but you're too busy just enjoying it, and that makes someone like me realise that if you get the entertainment right, you really just want to stop nitpicking.

Turns out, a film can do whatever the hell it wants. That's a wonderfully refreshing experience.

11. The Banshees of Inisherin

Directed by Martin McDonagh

The Banshees of Inisherin is wonderful black comedy, based around a simple premise but delving into deep truths. Pádraic (Colin Farrell) and Colm (Brendan Gleeson) are long time friends living in a small village on an island off the Irish coast. When Colm suddenly decides he no longer wants to be associated with Pádraic any more, it causes Pádraic a crisis of self, and starts an increasingly dark feud between the two.

Martin McDonagh has a truly wonderful handle on tragicomedy. It's a style he's very good at, and he uses it to good effect in this film. It's easy to laugh at the peculiarity of the situation and how it's presented, but it's also a way to unmask themes of depression, of rejection, of seeking purpose in one's life. Brendan Gleeson has a subtle but powerful role to play in this—while there's some truly wonderfully and more overt performances from Farrell, and from Barry Keoghan as Dominic, the son of the local garda.

There's also some truly wonderful cinematography showing off the harsh beauty of the isle, matched to Carter Burwell's score, and to the plaintive folk tunes that Colm writes.

I found the film less successful in its symbolism with regard to the Irish Civil War. It felt heavy-handed, and ultimately a little reductive. If you ignore the parallels McDonagh is trying to draw, then it's fine as a backdrop—the cannons firing on the mainland provide atmosphere rather than commentary on the relationship between Pádraic and Colm. But it's a shame, because it's clear that the message was supposed to be deeper.

Overall though, it was a very engaging film—sometimes tragically hilarious, sometimes hilariously tragic. If nothing else, it's another example that McDonagh can craft entertaining but poignant films, even across very disparate styles.

12. Empire of Light

Directed by Sam Mendes

I genuinely enjoyed this rather understated film from Sam Mendes, which seems to have been critically ignored or worse this Oscars season. Olivia Colman plays Hilary, the duty manager of a cinema on the south coast of England in the early 1980s. She's lonely, possibly depressed and forced into fleeting sexual encounters by her boss Mr. Ellis, played wonderfully against type by Colin Firth. Her life changes when she befriends her new, young co-worker Stephen (Micheal Ward).

As much as I was afraid this was going to be a movie about the movies, a long tired tradition, this was about a lot more. It was about mental health, and taking chances, about regret and purpose. It was about race and politics in the country of Thatcher. It was nostalgia for the past and a warning for the present.

Quite aside from the thematic content, it was also beautiful to look at. Mendes's love of the cinema as an object is on display here, and his eye for detail in production design and photography was wonderfully transporting. I also genuinely liked the script, which was understated but never vague. Hilary is vivacious in all her various guises (even those where she's flattened by lithium), and Olivia Colman is once again magnetic in her role. It is, to some extent, rather ambivalent about mental illness, but Hilary is never unsympathetic. I found Stephen's character a little thin, however, which makes him feel more like a concept than a person—a target for racism, but used to some extent as a plot device rather than to really empathise with the victims of racism.

I also found some of the changes in perspective a little jarring. For the most part, our focus is Hilary, and the story is seen through her eyes alone. But later, we start to examine more of Stephen's life, and we start to get scenes solely from him—it's something that takes us out of the interiority and claustrophobia of the earlier parts, perhaps intentionally. But with Stephens character being never fully fleshed out, it means that it feels like these scenes are stretched for emotional content.

But overall, there was much to like in this film. The cast in general is excellent—I'm waiting for Toby Jones to get his late-career leading role that earns him an Oscars nod, for instance—the script is mostly very good, and it's overall largely a joy to look at. I think it's a lot better than it's given credit for.

13. Causeway

Directed by Lila Neugebauer

A very solid film, in the subdued story-telling style of independent cinema. Jennifer Lawrence plays Lynsey, who is forced to return home to New Orleans from Afghanistan after suffering a brain injury in an explosion. We see her gradual recovery, and the development of her relationship with James (Brian Tyree Henry) whom she meets by chance.

It's a fine, and mostly understated film, as Lynsey and James help each other process their traumas. Lynsey also has to reconcile her life in the military, which gave her a sense of purpose, and an escape from her family life, with the reality that she may now be stuck in this city forever. A vital part of this conflict comes from Linda Emond, who is extremely good as Lynsey's unreliable mother.

The film is only up for a single Oscar this time around, and that for the performance by Brian Tyree Henry, who is indeed extremely charismatic and intriguing on screen. Lawrence is, by comparison, more staid, but she well captures the military stiffness that forms Lynsey's shield.

It's also a well-crafted script, which places pieces of the puzzle down gradually—allowing them to create the film's narrative drive and emotional impact. A poignant scene towards the end between Lynsey and her brother really draws the whole thing together.

It's the sort of filmmaking I really enjoy, and while we've seen similar things to this before, this is a fine example of it. And when you get a fine example of something that you generally really enjoy, you can be sure that it's a successful experience.

14. Navalny

Directed by Daniel Roher

The "documentary as thriller" is alive and well, as shown by this remarkable effort by Daniel Roher focusing on the assassination attempt of Russia's main opposition leader Alexei Navalny. Focusing on the investigation of his poisoning after the fact, while in exile in Germany, Navalny and his team seek to unravel a conspiracy.

While the investigation is genuinely fascinating in many ways, and provides a taut narrative about how close Navalny came to death, it's also wildly entertaining. There's an element of farce about how the Moscow4 (as they're dubbed, for amusing reasons) set about the assassination attempt, and their eventual coverup. A particular sequence where Navalny himself prank-calls the suspected perpetrators is honestly one of the most jaw-dropping scenes I've witnessed in many years.

It also attempts to provide a realistic portrait of Navalny himself. He's a charismatic man, with a good sense of humour and rapport with his staff. But to be honest, the depiction overall is fairly burnished. While it asks some difficult questions of him, it never really grapples with things like his association with racists and Nazis early in his career. His answers—revolving around the need to build a coalition, and that Russia is still only in a nascent place where it comes to human rights anyway—are evasive, and make me wonder who a future President Navalny might end up being, and whether he will truly herald a break from the world of strongmen and oligarchs.

Still, it's a fascinating piece of filmmaking, and a thoroughly engaging one. As far as documentaries go, you rarely get one that has as much intrigue as a scripted political drama. Roher handles the story with much more finesse and skill than other recent attempts (for example, Icarus). That's worth a lot.

15. EO

Directed by Jerzy Skolimowski

A fascinating and ultimately quite dynamic adaptation of Au Hazard Balthazar follows the titular EO, a circus donkey, through various misadventures after the circus is closed down. It's a simple premise, but it allows the director Jerzy Skolimowski to explore little snippets of humanity (good, and most certainly bad) through a natural framing device.

There's a reason why you use a donkey for this type of story. They have a natural sense of despondency to them, but a willingness to accept what the world imposes upon them. They're strong, but servile. I feel like humans have a natural empathy for them in a way that we don't for other similar animals, and this allows them to be a powerful conductor for emotion.

The soundtrack is another important element in this film's impact. It has extremely striking musical cues to punctuate the action, in particular brash horns which mimic donkey's cries (and, of course, the name of our protagonist). There's always a sense of turmoil, of impending doom, or perhaps a sense of representing the interiority of the donkey's psyche—in contrast with his placid exterior.

Plot-wise, it is undoubtedly a little meandering, as EO moves from one situation to another, often with rather contrived methods of escape. After a while it feels like it's repeating itself, and in some ways it seems as though it's marking time until it can progress to its conclusion.

Skolimowski is, however, a peculiar director, and one who couches his messages in fairly oblique imagery. We get travel sequences bathed in blood-red lighting, segments involving robot dogs dealing with a similarly uncaring world, drone shots that fly among wind-turbines. There's a suggestion that there's a powerful message all the way through, but it's not until the final scenes that we get any kind of certitude about what he's telling us.

It was at times a perplexing film, but by the end there was a sense that that was at least partially the point. While we might not agree with Skolimowski's world view, was can at least appreciate the potency of it.

16. A House Made of Splinters

Directed by Simon Lereng Wilmont

A bittersweet documentary about a Ukrainian institution for children—a temporary one that acts as a safe place before children, often neglected by their parents, get moved to a more permanent home. There's a sense of hope and love within these walls, but never a sense of belonging. Children will be moved on: perhaps to a foster carer, perhaps to a state-run orphanage. Perhaps, if they're lucky, to a relative who can adopt them.

We focus on the lives of some of the children as they face these challenges. Most have alcoholic parents—some leave them alone for days while they go on binges, leaving them to fend for themselves. Almost all still have the deep, unflinching attachment to the homes they know, despite this.

There are some tales of optimism, and some of desolation. The older children may have been here three or four times. Some are reaching their maximum stay length and will be moved to a far less caring environment as a permanent solution. Some try to run away. Some sneak out to smoke, or find community with criminals.

But, starkly, most are just children, doing child-like things. They make friends, they play, they draw, they go to school. Perhaps their conversation slips every now and then ("my parents used to make me drink beer, did yours do that too?"), but maybe they're just looking for something normal.

There's also something poignant about focusing in so tightly on this place, when all we generally see of Ukraine nowadays are the broad strokes of the war with Russia. It takes us inside, and in some ways removed from the war, to show us something intimate and human. That can be a very powerful thing.

17. Puss in Boots: The Last Wish

Directed by Joel Crawford

A very enjoyable animated feature, that harnesses the caricature of Antonio Banderas's Puss in Boots and turns it into a journey of discovery, when he realises he's burned through 8 of his 9 lives and can no longer live his swashbuckling devil-may-care life. Initially finding himself at a home for abandoned kitties, he eventually reunites with Kitty Softpaws (Salma Hayek) and they team up to carry off the ultimate heist.

The plot is serviceable enough, and the cast of characters are enjoyable, including "Goldie" and the 3 Bears (now a crime syndicate), Big Jack Horner, determined to harness magical powers for himself, and Perrito, the eternally optimistic therapy chihuahua. They provide enough substance to allow the film to explore its themes about the chances you get in life, the small moments you can take along the way, and the importance of family, both traditional and found.

It's also beautifully animated—taking a hybrid approach in action sequences to give them a wonderful comic-book style. It manages this while still feeling true to the origins of the character in the naissance of 3D animation. But it's a choice that elevates this film while also softening some of the more violent sequences.

Most importantly, I saw this film in the cinema with my 6yo and my 2yo and both of them sat rapt and engaged for its full length. If that's not a success then I don't know what is.

18. All That Breathes

Directed by Shaunak Sen

A very deliberately paced documentary that follows the tale of two brothers who run a wildlife shelter for injured black kites in Delhi. The brothers, guided by Islamic teachings, see this work as charity specifically called out as good works in the Quran. They fund their venture with the meagre profits from their business producing soap-dispensers, but seek external funding and training from abroad.

But the documentary develops as the story does. It becomes less about the brothers and more about the country. We hear political messages blasted through loudspeakers. We listen to debates on religious freedoms. The family off-handedly discuss their passports, the spelling of their names on their documentation, whether that might cause them trouble. We see the ever increasing number of birds which they care for, the pollution in Delhi, the rains that flood their workshop with sewage.

It's meditative. We get long tranches of footage of the wildlife that is now integrated with the city in India—monkeys climbing across the electrical wires, kites feeding off the landfill, frogs illuminated in the night lights of the road. It gives us plenty of time to reflect on what we're seeing, and the many ways we are interconnected.

It's not altogether that gripping, and it has no intention of ramming a message down your throat. Its design is to be persuasive in a far more subliminal way, to guide us towards a conclusion that it wants us to make—parallels between its strands that we can make our own decisions about. This can be a very effective way to make a point.

Overall, I thought it was a fine piece of film-making. While it wasn't as compelling or impactful as many others this year, it showed a great deal of craft and subtlety.

19. Elvis

Directed by Baz Luhrmann

An undoubtedly very stylish picture from Baz Luhrmann, Elvis tells the tale of The King himself, through the framing device of his long-time manager Colonel Tom Parker. Parker is portrayed by a prosthetics-enhanced Tom Hanks, while Austin Butler takes on the mantle of Elvis.

You can see from early on why Butler was cast: he is a pretty magnetic performer, and he has the physical swagger of Elvis when he's performing, as well as being a good vocal match. But, partially due to Luhrmann's always ostentatious direction (he has a habit, for instance, of skipping over things that might be plot relevant in favour of pure spectacle), transferring his swagger to the rest of Elvis's life-story makes it lose a lot of its humanity.

Instead, the film tried to be overtly political: in some ways, this is a refreshing surprise given it could have been all style and no substance. And in other ways, it almost feels like a necessity. How can you grapple with the concept of Elvis without examining the debt he owes to the blues, and to the Black folk who brought it to life. It's done in some subtle and some less-subtle ways: from blending Elvis's music with the likes of contemporary musicians such as Denzel Curry, to making the assassination of Martin Luther King a plot point of the film.

But the film really struggles when it tries to examine the human drama. There's conflict between Presley and Parker, of course, which has its moments of true tension. But there are also scenes, such as the breakup of Elvis and Priscilla where Luhrmann is out of his comfort zone and Butler is not up to the task of making us feel something.

Despite its unwieldy nature though, or perhaps because of all of the manifold pieces jammed together, it ends up feeling like a reasonable portrait of a flawed individual, complete with his contradictions and uncomfortable truths. It was nothing if not A Show.

20. All Quiet on the Western Front

Directed by Edward Berger

It's been almost 100 years since the last time All Quiet on the Wester Front won a Best Picture Oscar, so you can understand why the time might be right to try it again. We follow Paul Bäumer (Felix Kammerer) an idealistic German youth who joins Germany's war effort with the promise of conquering Paris in weeks. Instead, of course, he's forced into the reality of trench warfare as he watches his friends and comrades die around him.

There's no doubt this is a very grim film. It's a hard watch, and very deliberately so. Like the book before it, it is a fervently anti-war film—it shows the brutalities of war starkly and up very, very close. One minute the soldier next to you is chatting to you, the next second they're dead. This is how it is. We see the affect this has on Paul as he develops from wide-eyed youngster, to battle-hardened machine—it's a quite excellent performance from Kammerer to develop this journey.

In a change from the 1930 version, there's a parallel story in this film about the armistice negotiations between Germany and France. I wasn't entirely sure about the purpose of this, as it often took us out of the action right as the tension was building up (although perhaps that was the purpose—it's hard enough to watch without being mired in it). It did however show us the disconnect between those in power and those who were actually losing their lives, and Daniel Brühl as the German politician in charge of negotiations had a quiet pain in his performance.

I do feel like this kind of film is one to be endured rather than enjoyed, but I do understand the desire and the drive to make films about the horrors of war. It would be too easy to forget what war really means, and perhaps another reminded is just what the world needs right now.

21. The Batman

Directed by Matt Reeves

Let's put aside my concerns about whether we need another Batman film, let alone another Batman franchise running concurrently with the existing Batman franchise, shall we? We can take those as read. If we can manage that, then The Batman is honestly quite good fun.

Focusing on Batman as "world's greatest detective", this is effectively a neo-noir, as Batman tries to unravel a series of high-profile murders among Gotham's underworld. It uses its comic-book trappings as a foil, but it would almost be as effective were it shot in black-in-white with Batman as a 1940s Chicago flatfoot.

It is actually executes a rather effective plot, as the Riddler taunts and ultimately ties Batman into his plans, while the city police grudgingly use Batman's extra-judicial methods to assist the investigation.

It's also the film which perhaps best explores the paradox at the heart of Batman: what is it that causes this reclusive billionaire to become a vigilante. How is this helping the city he says he's helping? How does it hurt it? How does Batman himself cause the same problems he's trying to fix? That's not to say it's overly deep philosophically, but it at least engages with the problem.

Robert Pattinson is honestly wasted in the role, but he brings his dark charisma to it anyway, and in an always eclectic career, he's found another strange direction to go in. I also quite enjoyed Zoë Kravitz as Catwoman, although it's a starkly under-written role. And there's a certain thrill from the unceasingly grim production design and shadowed cinematography.

All up, I genuinely did enjoy it a good deal. But, admittedly, to get to this point, you do have to ignore the question of its relevance and necessity, plus you have to grapple with its bloated almost 3-hour running time. These are certainly things that make me pause from embracing it wholeheartedly.

22. Argentina, 1985

Directed by Santiago Mitre

Julio Strassera (Ricardo Darín) is a public prosecutor, who is responsible for leading cases brought before the Argentinian court of appeals. After the military's most recent dictatorship is toppled, the prosecution of the former leaders falls to him—a weighty task that involves threats to him and his team, a lack of cooperation from other established lawyers and, ultimately, perhaps even the fate of Argentinian democracy.

It's an interesting historical portrait—especially its depiction of the instability of Argentinian society which is used to the brutal rule of the junta. There's a sense of emerging from oppression and bringing things into the light—but it also exposes the fear that's associated with doing that. People might have feared and despised military rule, but its absence is in some ways also an unfamiliar threat.

I did find, however, that it was a little underwhelming as a legal drama—and that's largely how it's both billed and performed. After all, the majority of the film is set inside the court room. There's very little in it that's surprising in the way the argument rolls out: which is fine as a historical document of what was probably a long, technical trial. But it didn't really engage me in the plot. It doesn't try to do this, of course—it's more interested in making observations about the state of Argentinian society at the time, and the gradual understanding of the crimes of the dictatorship.

Overall, though, it was certainly a solid film, with a good deal to recommend it. But it didn't really manage to feel like the gut-punch of a film it might have been if it took us on a little more of a ride.

23. Women Talking

Directed by Sarah Polley

The women of a Mennonite community somewhere in the United States discover that the men have been drugging and raping them over many years, and they resolve to make a stand. When a vote is tied between leaving the colony or staying and fighting the men, a small group of women are chosen to decide for the whole.

The film then revolves around the hayloft where they convene to discuss the fate of the community—11 women, and the young male schoolteacher who, as one of the few left who can write, is tasked with keeping the minutes.

What follows is an interesting but perhaps not particularly novel investigation of feminism—the women, often downtrodden in this conservative society, go about deriving the tenets of gender equality from first principles, coming to see through a basic truth about fairness and kindness that they only have one option.

It's an interesting exercise, but in some ways it's not a particularly gripping one. I found the script a little leaden at times—it skips around without a lot of rhetoric power, and too often finds itself bogged down in theology. This is necessary given the setting, of course, but it often means it finds itself in cyclical patterns that feel self-perpetuating. There's the potential for this thematic material to be devastating, raw and powerful, and I really feel as though it never reached an emotional climax worthy of it.

I thought the performances were fairly solid, although I also found the characterisation lacking distinction—Claire Foy, Rooney Mara and Jessie Buckley's characters all blended into one for me, leaving the older women and Michelle McLeod's Mejal the most fully formed. Better is the understated performance from August Winter as Melvin, a transgender man who looks after the colony's children—their performance is subtle but marked with pain. Also good is Ben Whishaw as the schoolteacher, August, in particular towards the end of the film.

Overall though, it felt like a film that was so full of potential that it couldn't realise. Sarah Polley is a director I genuinely love, and this should have been an absolute golden moment of cinema for me. So even though it was interesting, solid and well made—that still feels a little like a disappointment.

24. Triangle of Sadness

Directed by Ruben Östlund

In so many ways, I had a great time with this film. Director Ruben Östlund has a great skill with a kind of dark, depressing satire taken to logical and artistic extremes in some of his previous work, in particular The Square. Triangle of Sadness sees him move to English-language cinema for the first time, and it feels like there's rich fodder here for him to lampoon a fresh segment of society.

We first meet Carl (Harris Dickinson) and Yaya (Charlbi Dean), two models, who are together "for the 'gram", and have squabbles over money, gender roles and manipulation while attending one of Yaya's fashion shows. It's a prologue to the main story, which is set on an exclusive luxury cruise. Carl and Yaya run shoulders with oligarchs and retired arms dealers, while waited upon by the staff of the boat, lead by Paula (Vicki Berlin), and the captain of the vessel (Woody Harrelson) who spends most of his time drunk in his cabin.

The unfortunate thing about the film is that it really struggles to hone its satire to a meaningful point. It is in so many ways a giddy and hilarious experience, especially as the ship eventually suffers a series of disasters that causes the social order of the cruise to invert. The characterisation and dialogue is honestly wonderful, and it makes individual scenes very entertaining to watch. But by the end of the film, I was expecting a punch—something to really drive the satire home; to make a bigger point about our own current societal inequality, or to provide some kind of call to action. And nothing really manages to provide it.

But that, I guess, is not Östlund's way of working. His tool is a mirror, not a scalpel. "Here are some sardonic observations on society", he says, "it's not my job to figure out how to fix them." But this also means that the film ultimately feels shallow, especially after some reflection on what I was meant to take away from it.

Still, I was entertained. And that's worth something. It's just disappointing when it could have been so wonderfully trenchant at the same time. That's when the film would have had real impact.

25. Turning Red

Directed by Domee Shi

I so often love the start of Pixar films, which do such a good job of selling their concept. In this case, it's the story of a teenage girl who discovers that excess emotional stress turns her into a giant red panda. It's beautifully juxtaposed with the turbulent time which is puberty, while examining life from the perspective of a young person growing up and making their own way in the world.