Text

käärijä looks so finnish it's insane, like ive for sure seen him in a hesburger somewhere

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient burial

In the old Karelian/Finland graveyards, remnants of burial structures, known as 'domoviny' or tombs, can be found – low resemblances of residential houses with roofs. Relatives strived to arrange the afterlife of the deceased as best as possible, even providing them with their own little house

#skull#grave#fantasy#fairy tale#fiction#story#slavs#finns#vikings#history#drawing#skeleton#burial#mysticism#forest#art#dnd#finland#scandinavian#baltic#ruin

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, I get being mad at the Eurovision results, but I personally draw the line at two things:

Personal attacks towards Loreen's character, appearance, etc., not to even mention misogynistic, transphobic, and racist slurs.

Dragging Sweden's colonization of Finland into it. Because while what is now modern-day Finland was gradually and sporadically under Swedish rule from roughly 1266 to 1809, and there were obviously some skirmishes related to the crusades and colonies, and your typical oppression of peasants here and there... we, by every possible European/international standard, have been fucking lucky. We've been largely left to our own devices: no serfdom, no violent and systematic erasure of language and culture, no unfair treatment compared to the rest of the population (generally speaking, of course). Hell, even the Russians treated us much better than many of the other peoples under imperial rule, even granting us autonomy. But my point is: I'm not trying to tell anyone how to feel about Finland's history with Sweden or what could have been if they hadn't colonized us (hint: it would have been Novgorod and/or the Germans instead), but I feel dragging something that happened centuries ago into it as if it’s relevant especially when Israel, who might well have won instead, is violently colonizing and oppressing Palestine as we speak is... kinda crass. So, in that respect, I say: get the fuck over yourselves, Finns. We are not special.

#not tagging this because I don't have energy for discourse#but I had to say something#like hell#I just got back from Latvia and learned more about their history with the German colonization#which was much more of a textbook colonization under the guise of a 'crusade'#oh and the Baltics were under Swedish rule too for some time#do you see them throwing tantrums at Sweden for that right now?#again#we are not special#or if we are it's because we've been hella lucky#like if we're going to be mad at historical colonizations#even Ukrainians could be mad at Sweden because Rurik was in all likelihood a Swede#Finns have such a massive main character syndrome sometimes and it's exhausting

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

En Route to Germany (No. 3)

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 10°E to 30°E longitude. A marginal sea of the Atlantic, with limited water exchange between the two water bodies, the Baltic Sea drains through the Danish Straits into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, Great Belt and Little Belt. It includes the Gulf of Bothnia, the Bay of Bothnia, the Gulf of Finland, the Gulf of Riga and the Bay of Gdańsk.

The "Baltic Proper" is bordered on its northern edge, at latitude 60°N, by Åland and the Gulf of Bothnia, on its northeastern edge by the Gulf of Finland, on its eastern edge by the Gulf of Riga, and in the west by the Swedish part of the southern Scandinavian Peninsula.

The Baltic Sea is connected by artificial waterways to the White Sea via the White Sea–Baltic Canal and to the German Bight of the North Sea via the Kiel Canal.

Source: Wikipedia

#MS Huckleberry Finn#TT-Line#morning light#Baltic Sea#Ostsee#travel#on board a ferry#original photography#vacation#summer 2020#Sweden#Sverige#Scandinavia#Northern Europe#en route to Germany#clouds#reflection#sun rays#tourist attraction#Atlantic Ocean#seascape#sky#horizon#nature

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I noticed that in one of your posts you showed an Iron Age Finnish woman's dress. Would you happen to have a good idea of what Finnish men were wearing in that era? The information on it seems sparse. I do have a relevant book that I'm about to look through, but I'd like to hear your insight too!

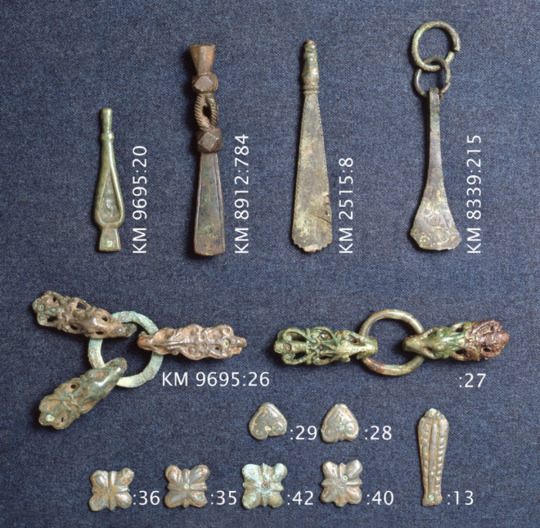

Hi! Thanks for the question (and sorry for the slow answer), I do love Finnish Iron Age clothing so it's always my pleasure to write about it. I've been wanting to do a deep dive into this for a long while, so maybe I'll do at some point a post about women's dress too.

Unfortunately no one has good idea of the Finnish Iron Age men's dress (and if you find any book or other source that claims otherwise, do not trust it), since there's much fewer archaeological finds of men's dress than women's dress. The most accepted theory on why the textiles of women's dress survived surprisingly well is because of the bronze ornamentation commonly sewn into especially the fine women's dresses of the era. The bronze protected them from decomposing fully. Presumably men's dresses were not decorated similarly then. There are some finds though and we can piece together at least some kind of vague picture.

I will be discussing the period from Viking Age to Crusade Age in Finland. Viking Age is often defined to cover 800s to mid-1000s and the Finnish Crusade Age started right after the Viking Age and ended in the end of 1200s, where the Finnish Medieval era begins. Crusade Age refers to the period where mostly Swedish (also German) crusaders in the span of couple of centuries conquered lands of the Baltic-Finnic pagans. The crusades of this period targeted pagans all over eastern Baltic Sea, including Baltic-Finnic Karelians, Livonians and Estonians, and Baltic peoples, and the Scandinavia too, where Sámi people were targeted. After that the Finland and Sápmi were colonized by Norse people and stayed that way untill Finland was transferred under Russian rule, but to this day Sápmi still stays under colonial rule, including Finnish colonial rule. The current Finland was very multicultural area, mostly populated by Finno-Ugric peoples, including Sámi people, Karelians and various Finnish peoples.

It's important to understand that even just Finnish peoples where not homogeneous, but had distinct, yet of course strongly related cultures. These were Finns (suomalaiset) (yes most people we now call Finns were not in fact called that) in the coast of southwestern and western Finland, Tavastians (hämäläiset) in central-western lake-Finland and Savonians (savolaiset) in central-eastern lake-Finland. This means we can't mix findings from all over Finland to reconstruct a dress without evidencing that all the elements were actually used in one place. These three tribes had broadly similar base for their clothes, but distinctive jewelry and detailing. The big divide was and has always been between eastern and western Finnish peoples. This is because western Finnish people were in close contact through the sea with Norse people and southern Baltic-Finnic peoples, while eastern Finnish people, Savonians mostly, were influenced a lot by their proximity with Karelians. Another dividing factor was the very different environmental conditions between western and eastern Finland. The Finnish coast especially in west is very flat and fertile land, while the lake area, especially in eastern Finland is very rocky, hilly and quite infertile. The main way it effected clothing differences was that western Finland being more wealthy had more elaborate clothing. Tavastians in both occasions fall quite in between, but they tended to be more in the western cultural camp.

My most important sources are a study by a doctor of cultural anthropology, Jenny Kangasvuo, Savon historia I (Savonian history) digitized and open sourced here and the digitized archeological collection of Finnish Heratage Agency. They are all in Finnish so not very useful for most people unfortunately.

Finnish Men's Dress in Viking and Crusader Ages

The basic garments men wore were broadly similar as women. They wore a shift/shirt, knee or above-knee length dress, cloak, belt, shoes and some kind of headwear. Wool was used most commonly, though the shirt would sometimes be linen too. Even evidence of silk has been found in some western Finland graves. I would assume that would be from a dress of some great man, who traveled to gain riches, possibly with vikings. Embroidery and decoration with metals was a typical feature of the whole Eastern Baltic Sea area. In Finland during this period bronze was the most common decorative metal, but silver was used too. Decorative elements were usually woven with small bronze spirals into all kinds of patterns. Here's examples from the reconstructed Ravattula's dress (Finns) used by women.

Shirt

The shirt (in Finnish shift of both women and men was called shirt) was basically a long shirt or under dress. We can assume it was similar to those of women's except shorter since the dress men wore was shorter too. They were made from wool or linen, I would assume wool was used in winter and linen in summer, when linen was even available. The neckline had a cut and closed with a bronze brooch. Horseshoe brooch was common. The first one is a quite typical bronze horseshoe brooch with a bit of ornamentation from Salo (Finns). The second one is from Tuukkala, (Savonians), it has exceptional ornate detailing and is uncommonly silver, not bronze. The third picture has two quite uniquely ornamented horseshoe brooches, first from Köyliö (Finns), second from Kurikka (Finns).

Legwear and footwear

Very little of men's legwear has survived and it's unclear weather men wore pants or separate pant legs, leg wraps or perhaps long socks. Evidence of strings decorated with bronze spirals and tablet woven band has been found in leg area of men's graves. This could mean that they wore either leg wraps, long sock or some sort of pant legs that needed to be secured with string or band under knee. Women used strings and tablet woven tape to secure leg wraps and socks, which I think supports that theory. Sometimes both bronze decorated string and tablet woven band was found in the leg area, which would still be explained by this theory, since it was common to decorate the ends of the bands with bronze decorated strings. Here's an example of sock bands just like that from the earlier mentioned reconstruction of the Ravattula's women's dress. Since men's dress was shorter, I think it would make sense if they still wore some kind of pants or separate pant legs with socks or leg wraps like that.

However, the strings and bands could have also been part of the shoes. Everyone probably wore similar shoes - laced leather shoes with a bit of pointed end. They might have been short or ankle length and the lacing was done with either leather cord or tablet woven band, which would also explain the findings. Socks or feet wraps would have been used in them, and straw or wool could be added as filling for warmth. Here's a pair of traditional Izhorian shoes from Estonia from early 1900s, and a pair of traditional Sámi shoes. The designs were likely roughly similar in Viking and Crusader Ages, though obviously more simple, and it's probable that Finnish shoes very something like that too. Here's a 1893 drawing of what findings of shoe material from Korpiselkä (Savonian or Karelian) might have looked like. Considering the quality of archaeology of that time, copious amounts of salt should be applied. And finally as a fourth picture there's reconstruction shoes from Ravattula's dress.

These are not necessarily mutually exclusive theories. The lacing of the shoe could have been laced up the leg and used also to secure either sock or leg wrapping, or they could have been separately secured in ankle and knee respectively.

In some graves twill fabric has been found in the leg area. It could be part of pants or for example leg wrapping, which was often made of twill. One theory about pants is that they were similar as some findings in Sweden, where fairly tight pants made of twill were secured at the hem with buttons similar to cuff studs. These kinds of cuff stud buttons are quite a common find in Finland and some have been found in men's graves close to legs.

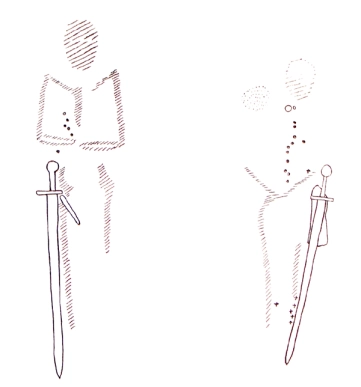

Dress

Again there's not much findings of dresses, but a little more perhaps. It was usually from wool. The shape was either a tunic or an open coat. In Karelia there's findings of men's dress suggesting tunics thicker than women's dresses and made from sarka, a type of broadcloth. On the other hand, in Masku (Finns) they found buttons in a row on top of the torso, which suggest a coat closed with buttons. The first picture is a drawing of the grave find. Similary coak closing amounts of buttons have also been found in other places in western Finland. This suggests that Finns and probably Tavastians too wore long coats buttoned to the waist and Savonians wore tunic of Karelian influence. Below there's couple of version of what might this western Finnish men's coat dress could've looked like. The first is an imagined version of the coat based on the Masku grave finds, second is just as imagined version based on Eura (also Finns) grave finds.

Take these "reconstructions" with a strong dose of salt. These are more artistic reconstructions than scientific, since there's not enough material and too much guesswork needs to be done. And because we can see in the Masku grave drawing right here that the other deceased has a large buckle to (probably) close the shirt (to be fair, it could for a cloak too), like was typical, I find it implausible that the coat neckline would be small and round covering the buckle. If you make a decorated big buckle, I assume you want to show it. I would find a v-neckline more probable. It's also easier to make without wasting expensive fabric.

The buttons are interesting. There were what you would imagine - your typical buttons made of bronze like seen in the first artifact from Hattula (Tavastians). But then there was silver jingle bells used as buttons, found for example in both Masku and Eura graves, Eura findings pictured below.

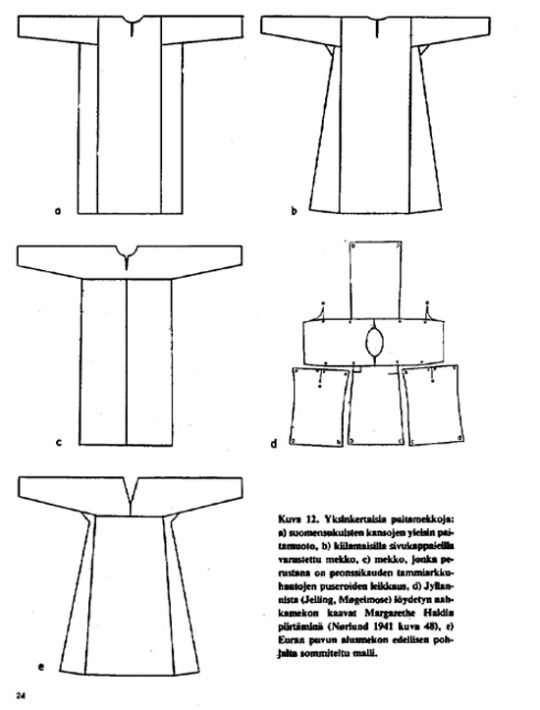

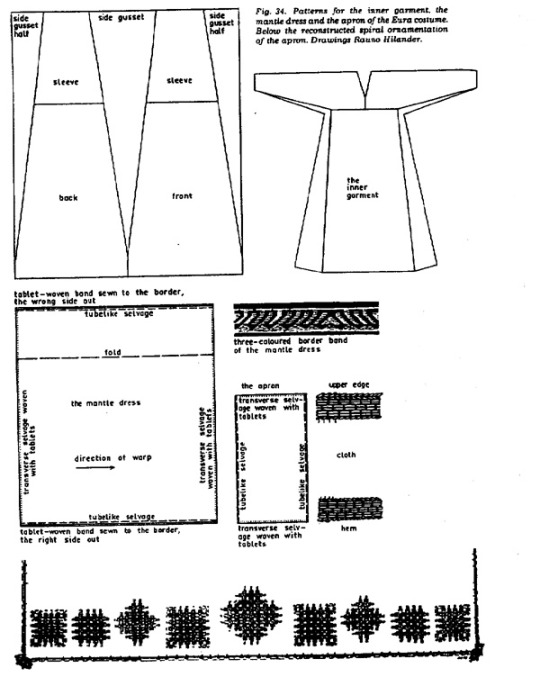

It's possible, even probable I'd say, that the hemlines of men's dresses were finished with tablet weaving patterns, like women's dresses. Also I would assume the pattern of the men's dress (and shirt) was mostly similar to the women's underdress/shirt patterns. So here's couple of different reconstruction patterns for women's dress. Different historians have made different interpretations of the patterns, so it's very much undecided what it really was like.

Belt

This is likely the most ornamental part of men's dress. They could be made out of leather or tablet woven band. And there's another east-west cultural divide here. Karelian belts were made out of leather, were usually 1,5-2,5 cm wide, decorated with iron or bronze studs and had a buckle made out of iron or bronze. These types of belts have been found in Savonia too, for example in Tuukkala grave find, which you can find very cool pictures of in this photo documentation of the dig in pages 173-175. In western Finland a "hela" belt was the common style. I don't think there's a world for hela in English. It's a sort of decorative lamella, small metallic plate (not necessarily square but often so) attached to fabric or leather with studs or sewing. Hela belt came from the Permians of Kama river, who were one of the many Finno-Ugric peoples who used to populate much of European side of Russia. Karelians lived closer to Permians, so you might think Permians would influence eastern Finland more, but my theory is that the costal Finns, who frequently joined viking crews and at least were in close contact with merchants including vikings, who would travel along the eastern route through the eastern European rivers, where they could go all the way to Kama river or at least meet traveling Permians. Here's yet another Finnish source more on the Finno-Ugric people around Kama river.

Anyway, hela belt was made of leather and filled with small decorated lamellas, often in square shape, but various other shapes too, like animal ornamentation. In this period hela belt helas were bronze. First image is a nice full set of hela belt metal pieces found in Pirkanmaa (Finns). Second is an older example, right before Viking Era, from Vaasa, costal settlement, (Finns), depicting a very Permian style. The third one is a lion hela found separately in Pälkäne (Tavastians). They are also found in Tuukkala, showing that both eastern and western cultural influences were present there at the same time.

Another western Finnish belt type for men had intricate tassels decorated with bronze spirals hanging on the waist at the end of the belt. They could be made out of leather or tablet woven band. First image depicts a reconstruction of such tassel. Belts in east and west would have strap dividers to hang straps for things like purse, knife and sword. The first picture above has couple of those, but the second picture below has two more of them in more detail in the middle of the picture. These finds are from Lieto (Finns).

Cloak

Like women's cloak, men's cloak was woolen and either a square or trapezoid. Cloak is yet another east-west divide. In western Finland men's cloaks have embroidery with bronze spirals. They in fact appeared earlier in men's cloaks (in 900s) than in women's cloaks (1100s). They were also a little different in men's cloaks. The spirals and the patterns themselves were bigger and the fastening thread itself was also used for the pattern creation, unlike in women's dresses, where the thread was mostly covered. In eastern Finland there has been no finds of bronze decorations in men's cloaks, mostly only cloak brooches have been left of them. Unsurprisinly same applies to Karelia. This also means there's very little fabric left too. There's one exception. In Tuukkala (Savonians) they found a piece of fabric probably from men's cloak, though it could be from a men's dress too. It was striped, with possibly white or brown base and wide stripes of red, blue and yellow. So perhaps eastern Finnish cloak was not non-decorated, but the decoration was in the fabric pattern. Unfortunately it's hard to know how common fabric like that was, when so little of it is left.

Accessories

It's safe to assume men too wore some type of headwear, but none of those has survived. It probably means it was entirely made out of fabric whatever it was. Some type of hat or cap was certainly used in cold weather at the very least. Tablet woven headband was also possible option for not too cold weather.

In Tuukkala there was couple of interesting jewelry finds too. Two graves had a necklace type mostly found in Karelia. It was birchbark tape covered with nettle fabric and had square helas sewn into it. There were also more typical Finnish necklaces made of beads and bronze spirals.

Razors have also been found with men in their burials, so we can assume shaven faces or at least trimmed beards and moustaces were fashionable.

#dress history#historical fashion#historical clothing#fashion history#history#iron age dress#finnish iron age dress#finnish history#archaeology#answers#anon

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finns visiting Estonia and other Baltic countries:

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking into the etymology of some Ethersea character’s names for fun and. I’m just gonna share my findings real quick cuz I think its cool lol (sources used are mostly wikipedia and behindthename. I could be wrong about some of this idk)

Oksana/Oxana is a Ukrainian name. It derives from either the Greek name Xenia, meaning “hospitality” or the word Xenos, meaning “stranger”. (Its also spelled “Aksana”!)

Griffin says “Boyar” is a German word for the child of a baron when he names Hermine, but its actually an Eastern European aristocratic term (apparently it WAS used by Baltic Germans too? But as far as I can tell not IN Germany) Hermine IS German though, its the feminine version of Herman, which means “army man”.

Tolliver is an anglicized variant of Taliaferro, which comes from Tagliaferro, an Italian surname meaning “iron cutter”. The spelling Taliaferro probably came from a transcription error. I was very surprised to find out its unrelated to Oliver lol

Declan is an Irish name. The Wikipedia article said it is “believed to mean” either “man of prayer” or “full of goodness” but there was no citation so idk.

Damian is used in a lot of countries with a lot of variations, but it’s ultimately from the Greek name Damianos, meaning “(I) conquer/tame/overcome”. Also the name of the Antichrist in The Omen, which I can’t help but feel might be related to why Travis picked it.

Cern is a German surname meaning “carrier” (some sort of connection to Declan being the Ballaster of Transit? Idk that might be a stretch)

Phineas is the anglicized form of Phinehas, a priest in the Hebrew Bible. The spelling Finneas might be influenced by Irish names containing the element “Finn”. Cawl was hard to find a good source on, but it’s the name of a Welsh soup, and it might be related to the Scottish surname Cowl or the Gaelic surname Cawley? Definitely seems Gaelic, in any case.

Aloysius is a Latinized form of Aloys, which is related to the name Louis. In the US, it’s mostly used by Roman Catholics. As far as I can tell Supreme isn’t actually used as a surname, but it comes from the Latin suprēmus.

Ravi is a Hindi name meaning “sun”. Montrell is Spanish or Italian (sources vary) and ultimately derives from the Latin word “monte”, meaning mountain.

Tessellation is a word meaning a tiling pattern with no gaps, which I think fits pretty well with the concept of brinarr

Guthrie is a surname that comes from the Gaelic word “gaothair”, meaning “windy place”.

Orlean comes from the French place name Orleans, which is related to the Roman family name Aurelius, meaning “golden, gilded.” The spelling Orlene is a French girl’s name meaning “golden” as well.

Aaaand I think thats all the ones I was gonna do thanks for bearing with me if you read this far o7

#icarus is talking#taz#taz ethersea#not tagging all these guys good lord#i was supposed to working on smthn else and went hmm let me look up hermine’s name and now im here

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Technically, every time I refer to Ahti, the little fellow in my profile picture, as Ahti II, I'm actually being somewhat incorrect. Ahti as I always draw him should really be called just Ahti, or Ahti Saarelainen, when we're being fancy. Otherwise I would be blowing his cover! But, let's slow down a bit.

I've yet to lay down Ahti's backstory in proper detail yet. As I've mentioned a few times before, he is a prince! The Baltic Sea is home to a merfolk kingdom named Osmeri, and Ahti II is the next in line for the throne. Osmeri royals have a tradition that spans at least a few centuries, where the young heir(s) must momentarily leave the life of royalty behind and live as "commoners" in another land. The official reason is to keep the royals in touch with how things work for average people and get them to socialise and familiarise themselves with everyday people, another reason might be to give the teenaged heirs one final vacation... and now it's the twins' Ahti II and Hienohelma's turn!

Ahti and his sister need to hide their true identity lest they end up in danger, of course. They go by the surname Saarelainen and live with their grandparents in southwest Finland. The native language of Osmeri, Surish, has an accent that sounds very much like a Swedish one to Finnish ears, so most people assume Ahti is a Swedish-speaking Finn, which is a minority group inside Finland (most live along the coast). He hides his merman tail most of the time so really, he's just some teenage boy. You don't tend to assume that the guy who sort of looks like the crown prince of another damn country is actually that crown prince in a silly disguise.

Here's Ahti in his two modes, as a helpful guide:

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Finland is not Nordic 🥲 It's a Finno-Ugric nation related to Estonia, Hungary as well as Finno-Ugric minority nations in the European Northeast.

Anon, I think you got Nordic and Scandinavian mixed up. You're right that Finland isn't Scandinavian, as that refers to the native cultures and languages of continental Northern Europe that originate from Norse and belong to the Germanic family. Nordic on the other hand refers to the cultural sphere of Northern Europe with significant Scandinavian (as opposed to Slavic) influence, which Finland is a part of, thanks to being a Swedish territory for most of its modern history. If there's any doubt, you can refer to the list of nations that make up the Nordic Council.

Finland also has no connection with Hungary outside of the fact that both of their languages belong to the Uralic language family. Finns may disagree if they're culturally more Nordic or Baltic, but there's no common cultural identity that contains all Uralic language speakers.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Etymological origins of the names of the regions of Finland

Suomi, Häme = Of the same origin together with "Sámi". There is no certainty of their etymology, but a common theory suggests they'd be a loan from the Baltic "žemē", meaning "land". However, modern linguists seem to argue that this is also inaccurate.

Satakunta = From Swedish "hundare", a Viking Age and early Middle Age Scandinavian war and governance system.

Pirkanmaa = Possibly from "birk", a special legal protection given to trading centers (early 1200s).

Uusimaa = Translated from Swedish "Nyland" (New Land).

Kymenlaakso = "Valley of Kymi". Kymi is a river. The word itself means... a big river.

Pohjanmaa = "Northland".

Keski-Suomi = "Central Finland".

Savo = From "Savilahti" (Clay Bay), the old name of the Mikkeli area. The origin of "Savilahti" is still debated, if it was originally savi (clay), savu (smoke), sauvo, or possibly a Sámi word for a backwater (savo, savu).

Karjala = A bit unclear. It comes from the word "karja", and if this word is of Germanic origin, then it could mean (war)band.

Kainuu = Unknown. Theories include Germanic loan "kainu/kaino" (lowlands), "kainus" (knob-headed staff, wedge-shaped object), a Sámi origin (compare gaajnuo, gaajnuoladdje (non-Sámi peasant); kai´nōlatj (Swedish coastal peasant); kainolats, kainahaljo (Swedish or Norwegian peasant)), Old Icelandic "kveinir" (an unspecified Northern Nordic people) or Proto-Norse "gainuz" (gap, jaw) -> "kainu(s)" (dragnet, sleigh).

Lappi = The most controversial of them all, I'd say. "Lapp" name usually refers to Sámi people, although they do not like this term so don't call them that. As for the etymological origin of said word, two theories: 1) a translation of an ancient Sámi tribe name "wuowjoš", from the word "wuowˈje" (wedge, patch) -> "lapp" (patch, small piece of paper). Old Finnish term for Sámi people is "vuojolaiset". 2) Meaning a remote area. The region of "Lappi" in Finland is a combination of two lands: Peräpohjola (Back of the Northland) and the areas of Sápmi (in Finnish "Saamenmaa") which are within the borders of Finland. Former land is Finnish, the latter Sámi.

Ahvenanmaa = "Perch land". Two theories: either it comes from Proto-Norse "Ahvaland" (water land?), or the Finnish form is the original.

In Swedish in the cases where it differs from the Finnish origin:

Österbotten = "East Bottom". As opposed to West Bottom, Västerbotten, on the Swedish side of the Baltic Sea.

Kajanaland = From the historical Russian name for Kainuu, "Kajánij/Kayániy". Meaning unknown, though some say it means a land in which it is difficult to travel. Likely, it is connected to the word "Kainuu".

Tavastland = Apparently from Old Norse "Tafæistaland" (ᛏᛆᚠᛋᛏᛆᛚᚭᚿᛏ). Origin unknown, theories say the "ast" part could somehow be connected to Estonia.

Finland = Hahaha. Unknown. Old sources use the word "finn" and variants to refer to both Sámi and Finns and you never really know what's the intention (think of Finland and Finnmark). Theories say that the origin of the word could be connected to Germanic words such as "finthan" (find), "fendo" (wanderer).

Åland = "River land". Two theories: either it comes from Proto-Norse "Ahvaland" (water land?), or the Finnish from "Ahvenanmaa" (perch land) is the original.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

oops! all scandinavians!

florida panthers @ tampa bay lightning | 10.2.24 (x)(x)

bonus baltic because i like him and he was on the finn parade bus so :)

#anton lundell#eetu luostarinen#niko mikkola#tobias björnfot#jesper boqvist#uvis balinskis#florida panthers#2425#preseason#paul needs to have his lineup filled with scandinavians always#comfort scandinavians#its so beautiful#its like watching a herd of wildebeest roam the savannah#great migration and all that#ive watched disney nature movies i know what im talking about (does not know what theyre talking about)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

German troops of the Baltic Sea Division in Helsinki, Finland, April 1918. The Germans had arrived to help the White Finns against the Red Finns in the Finnish Civil War.

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

En Route to Germany (No. 9)

Møns Klint is a 6 km stretch of limestone and chalk cliffs along the eastern coast of the Danish island of Møn in the Baltic Sea. Some of the cliffs fall a sheer 120 m to the sea below. The highest cliff is Dronningestolen [da], which is 128 m above sea level. The area around Møns Klint consists of woodlands, pastures, ponds and steep hills, including Aborrebjerg which, with a height of 143 m, is one of the highest points in Denmark. The cliffs and adjacent park are now protected as a nature reserve. Møns Klint receives around 250,000 visitors a year. There are clearly marked paths for walkers, riders and cyclists. The path along the cliff tops leads to steps down to the shore in several locations.

On 29 May 2007, close to the cliff tops, the GeoCenter Møns Klint was opened by Queen Margrethe. The geological museum with interactive computer displays and a variety of attractions for children traces the geological prehistory of Denmark and the formation of the chalk cliffs. The museum was designed by PLH Architects, the winners of an international design competition.

Source: Wikipedia

#Møns Klint#Møn#Cliffs of Møn#original photography#summer 2020#travel#abroad a ferry#MS Huckleberry Finn#TT-Line#Danish island#Denmark#Baltic Sea#Ostsee#en route to Germany#Northern Europe#vacation#nature#ship#landscape#countryside#seaside#blue sky#clouds#reflection#water#tourist attraction#landmark

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite History Books || The Northern Crusades by Eric Christansen ★★★★☆

The crusades to the Holy Land are well known, or, at least, widely heard of. The crusades against the Albigensian heretics, and against the Muslims of Spain, are familiar to students of medieval history. But the crusades of North-East Europe remain outside the scope of most English readers, and are remembered, if at all, as the subject of Eisenstein’s haunting essay in nationalist propaganda, the film Alexander Nevsky. He is said to have chosen the subject because so little was known about it that the facts were unlikely to interfere with his fictions. This book is an attempt to describe the struggles waged round the Baltic from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries in the name of Christianity, and to explain the part they played in the transformation of Northern societies which took place at the same time. There is no room for more. The general history of the Baltic world will only be referred to in so far as it directly concerns the crusades, and the reader will have to look elsewhere for a proper account of the rise and fall of the Scandinavian kingdoms, the East European principalities, the Hanseatic League, the fish trade, the German colonization of the East, the development of cities, churches and shipping. … Telling this story means keeping at least three balls in the air at the same time: a narrative of campaigns; a survey of ideological developments; and a sketch of political history. The crusades can be understood only in the light of, for example, the Cistercian movement, the rise of the papal monarchy, the mission of the friars, the coming of the Mongol hordes, the growth of the Lithuanian and Muscovite empires, and the aims of the Conciliar movement in the fifteenth century. Dealing briefly with all these big subjects, and linking them to the far north of Europe, has not been easy; and an English reader may well ask, is it worthwhile? There are several reasons for answering yes. In the first place, the Northern crusades were a part of a wider Western drive, and if that is to be studied it should be studied in full – in the most unlikely places, and in the most peculiar forms. The Holy Wars of the Mediterranean brought about spectacular conquests, and enduring obsessions, but amounted in the end to a sad waste of time, money and life. After 200 years of fighting, colonization, empire-building, missionary work and economic development, the Holy Places remained lost to Christendom. The Saracens won. The two faiths remained invincibly opposed, and if the cultures mingled it was not because the Christians had attempted to conquer the Near East; there were more enduring and less explosive points of contact. The Northern crusades were less spectacular, and much less expensive, but the changes they helped to bring about lasted for much longer, and have not altogether disappeared today. The southern coast of the Baltic is still German, as far as the Oder; and it is not sixty years since the Estonians and Balts lost the last traces of their German ascendancy and fell under a new one. Western forms of Christianity survive in all the coastlands opposite Scandinavia, and the Finns remain wedded to Western institutions and tolerant of their Swedish-speaking minority. The reborn republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania look west for support and sympathy. For seven centuries these east-Baltic countries were colonial societies, bearing the mark left by their medieval conquerors whatever outside power tried to annex or change them. If ever the crusades had any lasting effect, it was here, and in Spain.

#historyedit#bookedit#medieval#european history#northern crusades#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

I have a confession. I'm American, a few years ago in the middle of winter i visited Helsinki (very cool to see a frozen Baltic sea and thick fresh snow and all of the cars snowed in but was a bit frightening when the bus driver slammed on brakes and slid on the ice into the bus stop, but I could tell he was a pro) and took the ferry to Suomenlinna. My biggest fuck up of all time was walking into a building and opening someone's front door. The lady said " this is a private residence!" And shut the door and locked it. I always say and do stupid tourist things out of pure, crippling social anxiety, in America or abroad. I also took a bus to Espoo to visit my aunt who lived in an apartment, she gave me the address and described the building to me, but it gets dark at like 4pm in January and I got lost walking from the bus stop to her apartment because the snow obscures everything, and I walked into the wrong building and knocked on the wrong door. Anyway sorry to all Finns who encounter tourists like me.

Tourists mistaking Suomenlinna island as a full tourist attraction post and not an island where the tourist attraction is the castle only, and the houses are private houses were people live, is VERY common. Extremely common! You hear complaints about this annually from Suomenlinna residents, especially during summer.

But, I think it's also because there's not enough info and sign posts saying that this is a tourist spot, these are residential houses, please don't wander on any house's front or back yard. Only visit the castle ruins, the museum and the cafe-restaurant in the Suomenlinna harbor where the ferry stops.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Would the European Union’s eastern front-line states fight back like Ukraine if Russia attacked them? Unfortunately, this is no longer a hypothetical scenario: Hardly a day goes by without a Russian government official or pundit threatening Poland, Finland, or the Baltic states with missile attacks, an invasion, or both. In word and deed, Russian President Vladimir Putin has made clear that he seeks to restore Moscow’s former European empire.

The answer is probably yes, because the countries that have lived under the Kremlin’s rule know from their own long histories what Russian occupation entails. Those memories have been refreshed by today’s carnage in Ukraine, where the massacres of civilians by Russian soldiers in Bucha and Irpin served as a reminder that a loss of territory to Russia is not just a tactical setback, but also a prelude to barbaric violence.

The post-Cold War pretense that Russia would behave in a fundamentally different, more civilized way from its past practice is gone, reviving memories of more distant tragedies. Citizens of the three Baltic states remember mass executions and deportations at the hands of the Soviets in the 1940s, including the nearly 100,000 people who were deported to Siberia in 1949. Poles cannot forget the execution of more than 20,000 military officers in the Katyn Forest by order of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.

The list of Moscow’s crimes against its neighbors is long—and that list shapes Central Europe’s strategic posture today. As Polish Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski recently vowed, Poles would “eat grass rather than become a Russian colony again.”

Unsurprisingly, therefore, 80 percent of Finns surveyed in a 2022 poll said that they were prepared to defend their country. That same year, the Warsaw Enterprise Institute found that 66 percent of Poles were eager to come to their nation’s defense, and many are now volunteering for basic training. Residents of other nations from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea are expressing a similar determination to protect their lands and fellow citizens from a Russian assault.

The will is there, but is there a way? It remains uncertain whether there will be enough soldiers to fight Putin’s forces. Europe’s front-line countries may have a much greater recruitment problem than what Ukraine faces now—a problem that goes beyond these states’ already grim demographic trends, which have shrunk their populations by millions of people in recent decades.

What the Russian invasion of Ukraine has made clear is that technology cannot take the place of soldiers in a major land war. They are needed to crew tanks and trenches, move and service artillery, fly planes and drones, and occupy and keep territory. Ukraine, for instance, needs thousands of new soldiers each month to rotate forces, replace casualties, and prevent further Russian advances. Even more would likely be needed (along with regular allotments of Western-supplied ammunition) for Kyiv to go back on the offense and push Moscow’s forces out of the occupied parts of Ukraine. A country’s ability to generate a large and steady stream of infantry is thus essential to deter and, if necessary, defeat a potential invader.

But no matter what they tell pollsters, many citizens of Russia’s potential targets may choose to leave when the prospect of war becomes real. Their westward migration would be much easier than it might have been when these countries were not yet members of the European Union. In addition, there is a demand pull from Western Europe, which faces its own population shortages and need for labor. If these factors are not addressed, the likelihood of an exodus casts doubt over these countries’ capacity to guard Europe’s eastern frontier.

Central Europe is a beneficiary of one of the EU’s greatest successes: freedom of movement. The absence of internal borders between most EU member countries allows an easy flow of people and goods, ensuring the rights of nationals and legal residents to live and work in other EU countries. Short distances, cheap flights, educational opportunities, and cultural affinity have created unprecedented mobility of EU nationals. Equipped with language abilities and fungible skills, many young people from Warsaw, Tallinn, or Helsinki feel more at home in Berlin, Amsterdam, or Barcelona than in their own countries’ towns and villages.

In recent years, many Central Europeans have also acquired second residences abroad. Poles, for instance, have been buying real estate in Spain in record numbers. If their rising prosperity and desire to diversify their savings is one reason, then unease about the future since the return of Russian aggression is likely another. In Spain, after all, they would be safe from errant missiles and artillery duels.

The second reason why Europe’s front-line states may have a recruitment problem if Russia attacks is that much of Western Europe would be more than happy to accept large numbers of young people from their eastern neighbors, even if the migration was induced by war. Western Europe’s own labor shortages—and the prospect of large numbers of skilled young migrants who are considered easy to integrate—would be as much of a motivation for Western European generosity as solidarity with a country under attack, as suggested by the reaction to the influx from Ukraine in nations such as Germany.

Europe’s demographic trends are by now familiar: The continent’s working-age population has been shrinking for 13 years, now down by almost 10 million people—from a peak of 270 million in 2011 to roughly 260 million now. Today, the worker shortage is acute. Out of the 27 EU countries, 19 have shortages of bricklayers, truck drivers, nurses, and other skilled laborers. At the end of 2023, three-quarters of small- and medium-sized European businesses reported that they were failing to find needed labor. Germany alone is set to lose as much as 10 percent of its working-age population over the next decade. Europe is aging fast and losing tax-paying citizens—a threat that, to countries farther from Russia, feels as existential as the threat of war in the east.

It follows that many EU countries would be more than happy to absorb working-age people escaping front-line states under attack. Instead of being an economic burden, these war refugees would be a boon to Europe’s labor-deprived economies.

What’s more, many countries across the West face military recruitment problems. There is simply a shortage of people willing to serve and fight if needed. Poland now plans to train Ukrainian citizens of conscription age living on its territory for potential deployment in Ukraine. But this would also create a precedent for establishing a foreign fighting force on Polish territory, which other states could follow as a way to replenish their demographically shrunken forces. In the past, it has not been unusual for a country to have military brigades or even divisions composed of foreign citizens from war-torn nations.

From a political and societal perspective, it will also be easier for Germany, France, or Italy to take in European refugees who have connections across the continent, share a similar culture, and are generally eager to integrate. For European politicians, this could be a way to promote immigration without the political backlash that was visible in the recent EU parliamentary elections, where parties campaigning against the current trend of mass migration from Africa and the Middle East polled a record share of the vote.

The EU’s front-line states, if under attack, may therefore face a soldier shortage considerably more dire than the one facing Ukraine. It is hard to have a nation under arms if the bulk of the nation can easily leave. Of course, the affected countries could always institute border controls to keep recruits from fleeing, which even EU law allows. But unless there is a firm and detailed plan, these kinds of controls would take days, if not weeks, to put in place—and they would likely be met with an outcry in Brussels and Western European capitals, since they would contravene one of the EU’s proudest achievements. And by definition, any plan implemented only as a last resort following an attack would come too late to deter Moscow from attacking in the first place.

As war-waging Russia advances westward, European countries on the front line need to plan how to retain their own people. The ability of an EU member to fight will depend on the timely imposition of border controls, but even more on the patriotism of its people. Like the Ukrainians now, many front-line Europeans will fight for their nation—and for their nation’s place in a free Europe. But if their fondness for other parts of Europe trumps the sense of duty to their country, then they may choose to enjoy the benefits offered across the continent rather than face the Russian armies on their native lands.

One of the tasks for Europe’s front-line countries is, therefore, to sustain a vibrant patriotism. Only a deeply shared sense of nationhood can overcome the temptation of an easy and comfortable exit—and engender a willingness to sacrifice. Without cultivating this sense of patriotism and duty, Europe’s front-line states may face a soldier shortage that they haven’t bargained for.

7 notes

·

View notes