#cambodian dancer

Text

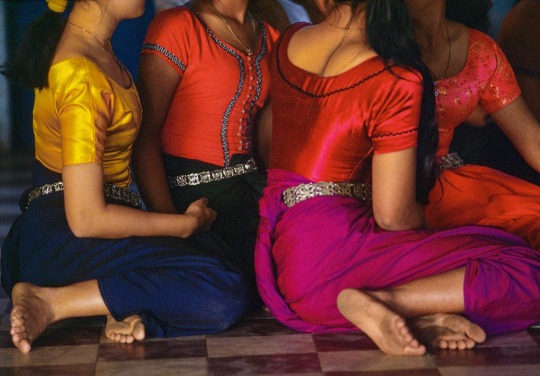

Ballet students at the Royal University of Fine Arts, Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 1999.

Photographed by Derek Hudson.

#derek hudson#royal ballet of cambodia#hands#1999#1990s#phnom pehn#cambodia#aspara dance#cambodian dance#cambodian dancer#cambodian#southeast asia#danseuse#danzatrice

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cambodian dancer on the 1922 Colonial Exhibition in Marseille, Provence region of France

French vintage postcard

#french#provence#colonial#carte postale#sepia#photo#postkarte#tarjeta#exhibition#ansichtskarte#marseille#postkaart#ephemera#postcard#vintage#historic#postal#region#dancer#briefkaart#1922#cambodian#france#photography

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dancers prepare backstage for Cambodian New Year, Chicago, 1993

#khmer#khmer dancing#khmer culture#cambodians#film photography#original photography#photographers on tumblr#dance#dancers#khmer children#cambodian children#chicago#mekong.net#bruce sharp#1993#kodak#pentax sf10#khmer in america#kodachrome

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

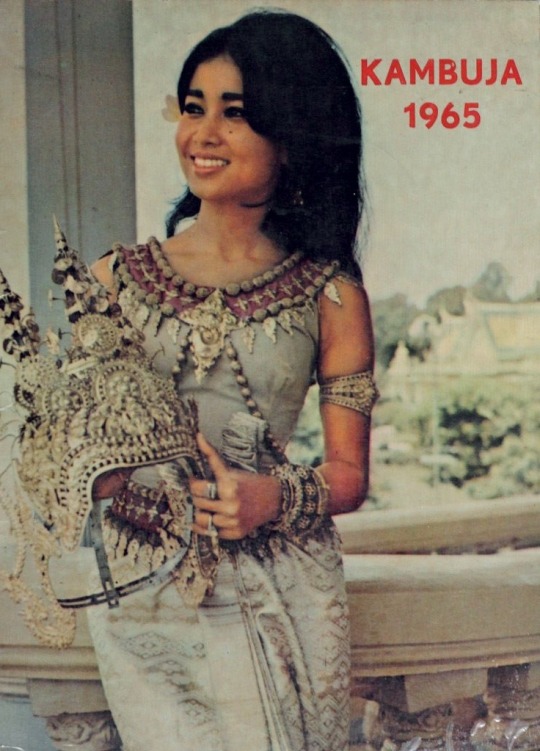

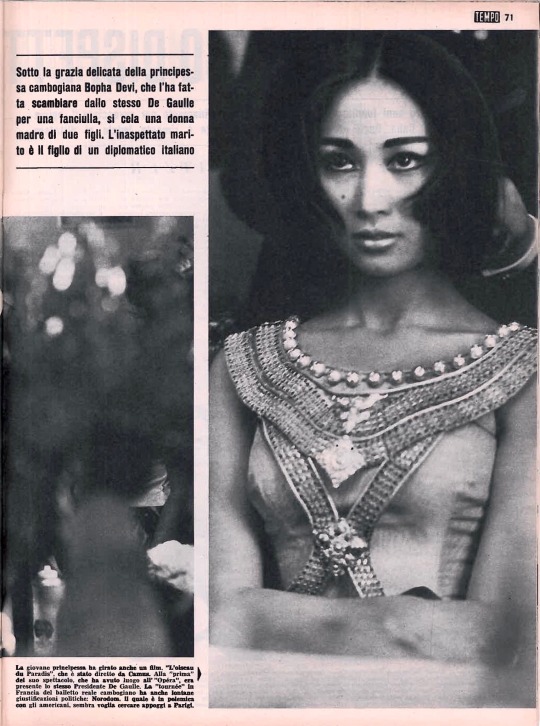

Cambodian Princess Norodom Buppha Devi in the 1960s. She was also a dancer, director of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, senator, and Minister of Culture and Fine Arts.

394 notes

·

View notes

Text

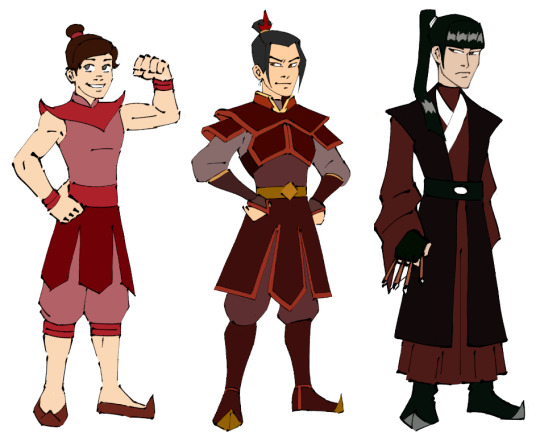

ATLA Gender Bender: Ty Lee, "Azulon", and "Mao"

Azula -> Azulon

Mai -> Mao

Ty Lee -> Ty Lee

"Azulon" is shown here wearing his Book 2 outfit. This is meant to be similar, but slightly different from Zuko's Book 1 outfit, to suggest that "Azulon" is wearing a nicer set of armor.

"Mao" seems to be the most popular name choice for male Mai. Like "Mai", the name "Mao" is Japanese in origin, but it is usually given to girls instead of boys. Still, there are examples of the name "Mao" being given to boys, though it is rare. I don't see the issue of him having an unusual name.

In ATLA, Mai's hairstyle is inspired by Nihongami, specifically fukiwa (see: atlaculture.tumblr.com/post/64…). As a male counterpart, "Mao"'s hairstyle is inspired by the sohatsu style. As it is drawn, this is not historically accurate, due to the length of his hair and his bangs. His clothes are visually inspired by the Korean drama "Hwarang" (2016). Note that the clothes of the hwarang are more Chinese inspired than native Korean. He is wearing a Chinese style banbi. In my mind, it makes sense for him to look like a hwarang, since he'd be an elite warrior youth.

Ty Lee's costume is visually inspired by traditional male Thai dancers and male performers of Phare, the Cambodian Circus. That's why I gave him a muscular appearance. Normally, I dislike it when the male version of a character is very muscular while the female version is not muscular. But in this case, there are too many reasons for male Ty Lee to be muscular in appearance. First, it would be odd for him to be named "Ty Lee" without possessing great physical strength. Second, when he runs off to join the circus it makes sense that he would be trained as a "strongman". Third, from a design perspective, it makes sense for the trio to include a taller, leaner boy and a shorter, more muscular boy. So in this specific case, I think it makes sense for male Ty Lee to have defined muscle structure, even though female Ty Lee does not. Still, he should not be as muscular as Bolin, since he is a couple years younger than Bolin. I tried to give him the musculature of a male circus performer without overdoing it.

I've been imagining P. J. Byrne as the voice of male Ty Lee, Aaron Himelstein as the voice of "Mao", and Jason Marsden as the voice of "Azulon".

Like what I'm doing? Consider leaving me a donation via Ko-Fi.

#avatar the last airbender#atla genderbender#genderbend#azula#ty lee#mai#genderswap#rule 63#my art#atla

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cambodian Traditional Dances

Traditional dance is a popular art form in Cambodia and so greatly revered that no visit to Cambodia is completed without watching at least one Khmer traditional dance performance. During the Khmer Rouge reign from 1975 to 1979, much of this Cambodian traditional art form was almost wiped out. However, huge efforts have been done to rekindle the ancient art from into new life. Dances in Cambodia are divided into three main genres: Classical Dance for the royal court, Folk Dance portraying cultural traditions and Social Dances performed in social gatherings.

1. Classical Dances.

Khmer classical dance, or locally known as Robam Preah Reach Trop, is a highly stylized performing art form originating from the royal courts. Originally, it was performed and maintained by attendants of the royal palaces, with the purpose of calling upon the gods and spirits, as well as expressing the respect to the royal courts. Later then, Khmer classical dance was popularized to the public in the middle of the 20th century.

Khmer Classical Dance was originated from the royal courts.

It soon became the symbol of Cambodian culture and often performed during special occasions like holidays, public events and for tourists in main tourism hubs. In the performance of classic dance, intricately costumed dancers perform slow and figurative gestures, with the musical accompaniment of a pinpeat ensemble. The classical repertoire includes dances of tribute or invocation and the enactment of traditional stories and epic poems such as the Ramayana. There are more than ten Khmer classical dances but the most performed and known dances are Apsara Dance (Robam Tep Apsara) and Blessing Dance (Robam Choun Por).

Apsara Dance.

The most popular form of classical Cambodian dance is Apsara, stretching back to the 7th century. A walk around the main temples of Angkor gives tourists general ideas about the importance of Apsara Dance in ancient Khmer culture, with the images of apsara dancers carved into the walls and bas reliefs. Its roots were found in both Hindu and Buddhist mythologies, with the concept that Apsaras were beautiful female creatures that visited Earth from heaven to entertain Gods and Kings with their enchanting dance.

Apsara is the most popular form of classical Cambodian dance.

The Khmer King Javayarman VII in the 12th century was said to have over 3000 Apsara dancers in his court. The dance moves in slow, hypnotic, and gentle paces in order to reflect the idea that spirits entrap mortals with their beauty. With more than 1500 exist, hand gestures are the main traits of the dance. Every single movement of the fingers has its own distinct meaning. Some movements even require dancers to bend their fingers almost to their wrists.

Elaborate traditional costumes is the identification of Apsara Dance, and help to mirror the majestic moves of dancers. They wear elegant silk clothes with floral motifs, stunning jeweled headdress, and sparkling accessories like necklaces, earrings, bracelets and anklets. Due to the extreme complexity of this performing art, Khmer girls start training from a very young age to get enough flexibility in their hands and feet to execute intricate movements.

The Apsara Dance was almost wipe out because the Pol Pot-led regime took a massacre included Apsara dancers in Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge period in 1975-1979. Luckily, few surviving dancers kept the tradition remained by passing their knowledge and skills to the younger generations. The most outstanding event marking the new life of Apsara Dance was when Queen Sisowath Kossomak Nearirath Serey Vatthana, the wife of King Norodom Suramarit, visited the Sothearath primary school in 1940s.

She saw the school mistress prepare an inspirational Angkor Apsara dance performed by young school children in the paper apsara costume so she got the idea of rekindling the dance. She trained her first daughter, Princess Bopha Devi, to practice the dance and 5 years old and then princess became the first professional Apsara dancer in the 1950s and 60s. In 2003, Apsara Dance was recognized as the Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

Blessing Dance.

Robam Choun Por is performed to wish for good health, happiness, prosperity and success.

Cambodian Blessing Dance, or Robam Choun Por in Khmer language, is traditionally presented at the beginning of a ceremony or special occasion in Cambodia. This dance is performed by a group of young Khmer girls in odd numbers (3 – 5 or 7 persons) to wish for good health, happiness, prosperity and success. The female dancers are well-dressed with Khmer Classical Royal Ballet costumes to symbolize the Devata. Each carries a golden goblet filled with flower blossoms inside, like jasmine, lotus or Romdoul. In Khmer’s perspective, blossoms are represented for the blessings from the Gods. With charming and elegant movements, dancers hold the golden goblets, pluck the blossoms and gently toss them toward the audience with honor and wishful blessing.

2. Folk Dances.

Cambodia Folk Dances play important roles in highlighting various cultural traditions and ethnic groups of Cambodia. As opposed to the classical dances, these folk dances are faster paced movements and gestures are less stylized. Folk dancers wear clothes of the people whom they are play roles, such as Chams, hill tribes, farmers and peasants.

Typically, folk dance performances are accompanied by a mahori orchestra, including stringed and plucked instruments as well as flute. Cambodian folk dances are also regarded as ceremonial dances because they are not performed widely in public. They are inspired by countryside life and practices, and tend to be reserved for the particular rituals, celebrations and holidays among rural communities.

There is a wide variety of Cambodian folk dances with different meanings:

Cambodian Folk Dances highlight various cultural traditions and ethnic groups of Cambodia.

Trot Dance– a popular dance featuring a hunter who is chasing a deer. In ancient times, Khmer villagers got troubles from the wild animals going to their villages. Therefore, this dance was performed to protect them from this bad luck. Trot Dance is performed to ward off evil and bad luck from previous year and celebrate the coming of Khmer New Year.

Sneak Toseay Dance – a dance around animal characters, like tiger, peacock, and deer. The dance originates in Phnum Kravanh District, Pursat Province and depicts the Pear people.

Robam Kom Araek – a dance mainly used two or three bamboo pole which hitting every second. Farmers practice this bamboo dance at the end of a long working day in the fields as a way of entertainment. It is reported that the dance came from Kuy people but it is more believed that the birthplace is Philippines during the reign of King Norodom (1834-1904) when he was traveling in Philippines.

Robam Kngaok Pailin – a dance describing the movement and beauty of the peacock. This dance portrays the Kula people in Pailin and their amusement with a pair of peafowl, but also much influenced by Burmese dance.

Chhayam – a well-known entertainment dance about pleasure, including several comedic roles and beautiful girls. The dance is performed at holidays and is a pure Khmer dance.

Cambodian Coconut Dance – a dance performance involving coconuts with male and female dancers. Men wear a yellow shirt and dark red “Changkibin”. Women wear a button up shirt and a green silk “Changkibin”. The dance originated around 1960 from Romeas Haek District in Svay Rieng Province.

Cambodian Fishing Dance – a dance performance involving fishing that was composed in the 1960’s at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh. It involves male and female dancers.

Social Dances.

At social gatherings in Cambodia, social dances are performed with common types, such as: ramvong, ram kbach and ram saravan.

Ramvong is social dancing form in traditional events, modern parties or celebrations.

Ramvong in Cambodia, Lamvong in Laos or Ramwong in Thailand represent for the popular social dancing form in these Southeast Asia countries. Both men and women can participate in the same circle, continuously move in a circular manner and perform basic hand movements and simple footwork. This slow round dance style can be seen in traditional festivals, popular celebrations and modern parties. In Cambodia, ram vong dance can be found among ethnic groups of the Phnong, Krung, Tampuan and Brao people.

Ram kbach dance is generally similar to ram vong in terms of circle arrangements, as well as hands and legs gestures. But the movements in ram kbach are slower and more gentle.

Besides ramvong and ram kbach, ram saravan dance style are also popular with Khmer people at festival time, when people gather and perform the dance together. Even being thought to traditionally originated from Laos, Khmer people love to perform it at special events like wedding parties, especially at Khmer New Year.

Like people all over the world, Cambodian people consider dancing is an integral part of spiritual life and rites of passage, as well as a popular form of entertainment. Moreover, they also believe that all dance styles – both traditional and modern styles, can help create friendship and happiness among society. If you are interested in exploring Cambodian culture through traditional dances, don’t hesitate to contact Cambodia Travel to plan your customized trip to this lovely country right now!

Cambodian Traditional Dances (cambodiatravel.com)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character list for the Heaven is in Your Arms series

Original Characters

(That I've been forced to create for the plot.)

Man Suang Characters

Dancers:

Suriya - a Thai dancer. He formally played female roles exclusively for Khon but once he joined man suang he also played female roles for Lakhon Nok and Lakhon nai. The self appointed leader of the Thai dance performers.

Sakda - a Thai dancer who plays female roles in Khon, Lakhon Nok and Lakhon Nai and is Suriya's rival for the lead roles.

Phichit - a Thai dancer who plays the role of the heroes in Khon, Lakhon Nok and Lakhon Nai. He is resentful of Khem who he feels is taking his roles away from him.

Lalita - a Thai dancer, she formally played the masculine hero roles in Lakhon Nai but since joining man suang she has also played hero roles for Khon and Lakhon Nok performances. She came from the palace after dance dramas were banned from court.

Kanchana - a Thai dancer, she plays principal heroine roles in Lakhon Nai, Lakhon Nok and Khon. In a not so secret relationship with Lalita.

Suda - a female Thai dancer who plays minor heroine roles.

Cheng Dieyi - a Chinese opera performer who plays female lead roles and is having an affair with Suriya.

Musicians:

Aadi - Indian, plays klong khaek tua aka Indian drum

Aahan - Indian, plays klong khaek tua mia and ching

Thep - Thai, plays ranet ek (Thai xylophone)

Amon - Thai, plays ranet thum (larger xylophone) and clappers

Feng - part Chinese, plays pi nai (Thai oboe)

Bun - Thai, plays klong that aka a pair of large drums

Poeu - Cambodian, plays ching (cymbals) and khong wong yai (going circle)

Vinod - Indian, plays tabla and harmonium

Others:

Malai - Khem's dresser, she takes care of his dance costumes and sews him into them for performances.

Kulap - a maid.

Fon - a maid

Chachoensao Characters

Chao Somchai - the local lord

Laksanara - Somchai's principal wife

Jaran - Somchai's son, former playmate of Wan

Saeng - overseer who worked for Somchai and controlled Khem and Wan

Bua - cook who works for Somchai and saved Khem

Nin - Wan's sweetheart

Kannika - girl who had a crush on Khem but was forced to marry Somchai.

Father Mikael - an English missionary

Historical Characters

(Names of real historical figures fictionalised for the story.)

Chetsadabodin - King of Siam

Mongkut - Chetsadabodin's half brother, a monk

Chuthamani - Mongkut's brother, a prince

Anand - a prince, Chetsadabodin's son

Bunnag - a very influential nobleman

Tish - Bunnag's son, Hong's friend in my story

That - Tish's brother

Sunthorn Phu - a famous poet

Luang Aphaiwanit - a rich chinese man who owns Ho Seng Tai manor and loves Thai dance.

#man suang fic inspiration#man suang fic#man suang fan fic#man suang oc characters#man suang characters#heaven is in your arms series

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Tell me more about spider destiny 👀👀

Cambodian Spiderman... Spiderwoman...?

17 year-old prodigy

Taught herself and is teaching her girlfriend, Sophea, English

Lesbian, with a dancer girlfriend

She is loud, cheerful and fun! Always chooses kindness before cruelty, and is quick to forgive even without there being any apologizes. (This is just how she is. She gets over things easily.)

Has lots of fun fighting bad guys. It's like a game to her, but she knows when to take it seriously. (Though, most of the time, she doesn't.)

I'm deciding if I should have her live in an apartment or a farm, like my grandmother and other relatives do.

Friends with Spiderman India! Because it's cute :)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

if there was ever a cambodian spiderman ngl i want a spin on the dancer outfit

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lyrics that promised us the riches of heaven were written by the engineers of our own public hell.

-Sophiline Cheam Shapiro

From her essay, “Songs My Enemies Taught Me”

Sopheline Cheam Shapiro was 8 years old when the Khmer Rouge invaded Phnom Penh and took power in Cambodia. She is a classically trained Cambodian dancer and above she was writing about the propagandist lyrics sung in Cambodia, lyrics perpetuated by the Khmer Rouge. Those lyrics promised growth and prosperity and those promises turned out to be empty for Shapiro.

If you want to read more, PBS have interviewed and written about her:

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

"Famed Cambodian dancer Sophiline Cheam Shapiro performs an unsanctioned dance at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to honor Cambodia’s stolen heritage."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 Fun and Interesting facts about Cambodia

Cambodia, a Southeast Asian gem, is a country rich in history, culture, and natural beauty, offering a blend of ancient wonders and fascinating traditions. Known primarily for the iconic Angkor Wat, the world's largest religious monument, Cambodia holds a treasure trove of intriguing facts that captivate both history enthusiasts and curious travelers. From the unique hydrological marvel of Tonle Sap Lake, which reverses its flow twice a year, to the haunting legacy of the Khmer Rouge and the Killing Fields, Cambodia's past is as complex as it is compelling. The country’s vibrant culture is also reflected in its traditional Apsara dance, a classical art form steeped in mythology and elegance. Moreover, Cambodian cuisine, with its rich Flavors and influences, offers a culinary journey that tantalizes the taste buds. Exploring Cambodia reveals a land of contrasts, where the ancient and modern coexist in a tapestry of captivating stories.

Here are some fun and interesting facts about Cambodia.

1. Angkor Wat: The World's Greatest Religious Structure:

Angkor Wat, the world's largest religious monument, is located in Cambodia and spans an area of more than 162 hectares (1.62 square kilometers). Angkor Wat was first built as a Hindu temple in honour of the god Vishnu in the early 12th century, but by the end of the century, it had changed to a Buddhist temple. The temple, with its elaborate carvings, enormous stone constructions, and vast network of temples and waterways, is a magnificent example of Khmer architecture. Appearing on Cambodia's national flag, it is a symbol of pride and one of the most important archaeological sites in Southeast Asia.

2. Tonle Sap Lake: An Exclusive Hydrologic System:

One of the most remarkable natural wonders of Cambodia is Tonle Sap Lake, the biggest freshwater lake in Southeast Asia. This lake's amazing hydrological phenomenon, its flow changing direction twice a year and its size fluctuating with the seasons is what sets it apart. The Tonle Sap River, which links the lake to the Mekong River, reverses its flow during the monsoon season, causing the lake to enlarge up to six times its typical size. Through farming and fishing, this natural wonder sustains a thriving ecosystem and gives millions of Cambodians a living. The fact that the locals have managed to adapt to this unusual environment is demonstrated by the villages that float on the lake.

3. The Killing Fields and the Khmer Rouge: A Somber Chapter:

There have been terrible times in Cambodian history, the most devastating of which was the Khmer Rouge rule from 1975 to 1979. The regime, headed by Pol Pot, attempted to establish a rural, classless society in Cambodia, which resulted in one of the bloodiest genocides of the 20th century. An estimated two million people, or almost a quarter of the population, perished from starvation, forced labour, and executions during this time. Many of these atrocities occurred in the "Killing Fields," which are now memorial sites that serve as a sobering reminder of Cambodia's tragic past. Despite this difficult period, Cambodia has demonstrated incredible fortitude and has worked hard to restore and maintain its rich cultural heritage.

4. Customary Apsara Dancing: An Important Cultural Artifact:

An ancient art form from Cambodia that originated during the Angkor era is the Apsara dance. This traditional dance has a strong cultural foundation in Cambodia and is frequently portrayed in carvings found in Angkor Wat and other historic temples. The slow, graceful movements of apsara dancers, who are dressed in elaborate costumes and headdresses, are symbolic of stories from Buddhist and Hindu mythology. Dancing is a spiritual and cultural expression that has been passed down through the ages; it is more than just entertainment. The Apsara dance is still a vital component of Cambodian culture and is acknowledged as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

5. Cambodian Food: A Harmony of Tastes:

The delicious fusion of Flavors that is Cambodian cuisine, also referred to as Khmer cuisine, is influenced by French colonization as well as neighbouring Thailand, Vietnam, and Laos. Meals in Cambodia typically consist of rice and fish, with Tonle Sap Lake and the Mekong River producing an abundance of freshwater fish. "Amok," a sort of curried fish wrapped in banana leaves and steam-cooked to perfection, is a well-liked dish. Bold Flavors are characteristic of Cambodian cuisine, which frequently combines tastes of bitter, salty, sour, and sweet in one dish. The distinctive and fragrant dishes that define Cambodian cuisine as a culinary adventure are frequently made with fresh herbs, spices, and ingredients like lemongrass, kaffir lime leaves, and coconut milk. The delectable "Prahok" (fermented fish paste) and the revitalizing "Nom Banh Chok" (Khmer noodles) are just two examples of the delectable Cambodian cuisine that any traveler hoping to experience the nation's rich cultural legacy must try.

Conclusion:

Cambodia is a land of captivating contrasts, where ancient history meets vibrant culture and natural wonders. From the awe-inspiring Angkor Wat to the unique Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia offers a diverse array of experiences that highlight its rich heritage and resilient spirit. Understanding the country's past, including the tragic era of the Khmer Rouge, adds depth to any visit, while the traditional Apsara dance and flavorful cuisine provide a glimpse into the living culture of the Cambodian people. For those planning to explore this intriguing destination, securing a Cambodia visa is the first step in uncovering the many layers of this fascinating country. Whether you're drawn to its historical sites, cultural treasures, or natural beauty, Cambodia promises an unforgettable journey filled with discoveries that will leave a lasting impression on any traveler.

0 notes

Text

Royal Cambodian Dancer of King Sisowath

French vintage postcard

#royal#dancer#carte postale#old#ansichtskarte#cambodian#photo#vintage#postkaart#king#photography#briefkaart#postkarte#french#ephemera#postcard#sepia#postal#sisowath#tarjeta#historic

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Different Stage Productions of Ramayana from Different Countries :

India:

Ramleela: An Indian Art of Story Telling that binds people from different cultures, religions, and faiths

credits to: linkedin.com

https://in.linkedin.com/company/ramleela

Ram Leela is a traditional theatrical performance that retells the story of the Ramayana, usually during the festival of Navratri. It is performed in many regions of India with local variations.

The whole act is performed in 10 nights depicting the birth of Lord Rama and different phases associated with his life in a melodrama style and finally, his overpowering the demon-King Ravana of Lanka, signifying the victory of virtues over the vices.

It elaborates costumes, vibrant music, dramatic dialogues, and intricate dance sequences. The performances often take place in open-air settings and involve community participation.

INDONESIA: WAYANG KULIT

CTTO: indoindindians.com

https://asiasociety.org/new-york/wayang-kulit-indonesias-extraordinary-shadow-puppetry-tradition

In Indonesia, particularly in Java and Bali, the Ramayana is performed using shadow puppets called Wayang Kulit.

The origin of the puppets has been traced to Indonesia. The most popular puppet performances enact the epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata from India, although the story in Indonesia is very different.

Puppets are intricately crafted from leather and manipulated behind a screen illuminated by a light source. A dalang (puppeteer) narrates the story, accompanied by traditional Gamelan music.

THAILAND: Khon “The Masked Pantomime”

ctto: disco.teak.fi

https://disco.teak.fi/asia/khon-the-masked-pantomime/

A battle between Pha Ram (Rama) and Totsakan (Ravana)

Khon is a classical masked dance-drama in Thailand, portraying the Ramakien, which is the Thai version of the Ramayana.

Performers wear elaborate masks and costumes, with intricate dance movements and gestures. The narration is often provided by a chorus, while the dancers enact the scenes.

CAMBODIA: KHMER REAMKER

ccto: bharatideology.com

https://bharatideology.com/reamker-the-cambodian-adaptation-of-the-ramayana/

The Khmer Reamker, a Cambodian epic poem, is a captivating rendition of the Indian ancient Sanskrit epic, the Ramayana. The Khmer Reamker, which follows the protagonist Prince Preah Ream on his quest to rescue his beloved wife Neang Seda from the clutches of the evil giant Reap (Ravana), holds a special place in Cambodian culture. It is a traditional Khmer dance with detailed costumes, and expressive hand gestures and facial expressions. The performance is accompanied by a traditional orchestra.

PHILIPPINES: Maharadia Lawana

A performance of Mahardia Lawana

ctto: medium.com

https://medium.com/@ckukur/im-writing-again-about-the-splendid-tale-of-rama-a-captivating-chronicle-chronicling-the-ventures-5b6c8dcf2519

The Maranao adaptation of the Ramayana in the Philippines, known as Maharadia Lawana, incorporates local folklore and traditions. It is performed as a dance-drama with colorful costumes, indigenous music, and storytelling elements unique to the Maranao culture.

The story begins with the formidable antagonist Maharadia Lawana (Ravana), hailing from the lineage of the esteemed Sultan and Sultana of Pulu Bandiarmasir, bearing the peculiar trait of possessing eight (or seven?) heads. However, his temperament proved vexatious, rendering the entire Sultanate a target of ridicule due to his actions. Eventually, word of his misconduct reached the ears of his father, resulting in his exile to the distant realm of Pulu Nagara. In that secluded isle, Lawana engaged in deep contemplation and devout penance and achieved spiritual fruition. Lawana returned to his ancestral dominion as a man reborn, eliciting boundless joy within the heart of his father.

LAOS: Phra Lak Phra Ram

ctto: wordpress.com

https://uddhamsoto.wordpress.com/2013/05/19/phra-lak-phra-lam/

In Laos, the Ramayana is known as Phra Lak Phra Ram, performed as a dance-drama. Performers wear traditional Lao costumes, with graceful dance movements and symbolic gestures. The story is narrated in the Lao language.

The battles between Hanuman and his monkey army with the army of Longka Island performed in dance to the accompaniment of the orchestral music adds much drama and entertainment to the evening performance.

MALAYSIA: Mak Yong

ctto: alamy.com

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/mak-yong.html

Mak Yong, a traditional Malay dance-drama, sometimes incorporates elements of the Ramayana. It combines acting, vocal music, instrumental music, and elaborate costumes. It is often performed by an all-female cast.

MYANMAR: Yama Zatdaw

ctto: bharatideology.com

https://bharatideology.com/myanmar-and-ramayana-an-enduring-epics-legacy-in-the-land-of-golden-pagodas/

The Burmese adaptation of the Ramayana is called Yama Zatdaw, performed as a traditional dance-drama. It features elaborate costumes, traditional Burmese music, and dance movements. The performance is deeply rooted in Burmese culture.

1 note

·

View note

Text

It is almost here - Asia North 2024 APIMEDA Makers Night Market is this Friday 5-9 pm! We are thrilled to have 14 vendors from across the Asian Diaspora sharing local and handmade goods. Join us for a night of festivities with Flowerhands Korean Natural Dye Workshop, Ethiopian food by @kosharycorner, Live Music by Steve Hung, Closing Event Performances & Festivities, last chance to see the 2024 Asia North Exhibit, and more!

Michelle is an American Filipina who delights in vibrant colors, movement, and sass in her often-nerdy art. She is a central Maryland native who takes inspiration from weird creatures, pop culture, and most importantly, her roots in the Philippines. Visit her booth on Friday to get Nerdy, sassy, dynamic art, stickers, paper goods, and accessories.

@martirology

Bijou Sachi is a natural, fragrance forward luxury hand and body care brand specializing in thoughtfully crafted, uniquely blended fragrances delivered via high quality ingredients.

Enjoy naturally fragranced mango seed butter hand and body balms scented in unique, luxurious combinations.

@bijoisachi

Craftstrology by Meredith is a Filipina-American astrologer and embroidery artist living in the Baltimore-Annapolis area and makes delightful handmade plushies and accessories.

@craftsology

Crafts Specialist and Dance Master Sochietah has been teaching at the Cambodian Buddhist Society Cultural Committee since 1999. His expertise is the villain role and Folk Dance. He is not only a dancer but also an expert craftsman innovatively creating beautiful headpieces, costumes, and jewelry for Cambodian Dances. His interest for dancing began when his grandmother told him that his grandfather was a star in Lakhorn Basaac (Khmer Opera). He started dancing in Cambodia in 1970 around the age of fourteen.

MAKERS NIGHT MARKET

Friday, May 31, 5 – 9 p.m.

Egyptian street food by @kosharycorner

Outdoors in front of the Historic North Avenue Market, 12-30 W. North Ave.

INFO: towson.edu/asianorth

Asia North 2024 is co-produced by @central_baltimore_partnership and Towson University’s @asian_arts_and_culture_center

0 notes

Text

Battleground Masculinity: Gendertroublers and Gatekeepers in Oliver Stone's Platoon (1986)

When Oliver Stone's autobiographically inspired war picture Platoon was released in the winter of 1986, it was one of the three movies that heralded a new era in the representation of the Vietnam war on the movie screen.1 Platoon set the tone for what was widely perceived as a realistic portrayal of the ordinary soldier's life in the war, a portrayal that refrained from inventing the Vietnamese as largely uncivilized and inhuman torturers, killers, and players of Russian Roulette and that took into account the cruelties and massacres occasioned by members of the United States armed forces. Time soon attributed its cover space to the movie and dubbed it "Viet Nam As It Really Was."2 Writer and director Oliver Stone was applauded for his sensitive and truthful account. The fact that his own tour of duty had inspired the film earned him the large-scale support of war veterans among the audience.

Yet Platoon is much more than a close-to-real-life depiction of a grunt's war experiences on the Vietnamese-Cambodian border. Due to its complexity as a cultural text, it is easily the one movie of its genre that has been most discussed and analysed in academia; having inspired well in excess of twenty scholarly articles on such issues as the film's Christian allegorical structure, the forces of good and evil, ritual and remembrance, the role of women, or colonialist subtexts in the film.3

Nevertheless, there remains a striking lacuna in the academic reflections on this culturally relevant filmic text, a blind spot that calls for attention.4 For while the homoerotic undertones of such homo-social genres as Western and war films have frequently been discussed, few movies have been engaged in negotiating the borders of the gender system as remarkably as Platoon.

Brief Summary

When young recruit Chris Taylor (Charlie Sheen) joins up with his unit in the Western part of Vietnam, he soon realizes that the platoon is split into two groups: the tough beer-drinkers and poker-players around Staff Sergeant Robert Barnes (Tom Berenger) and the music loving pot-smokers and dancers around Sergeant Elias Grodin (Willem Dafoe). Taylor finds himself oscillating between the toughness of Barnes and the moral integrity of Elias; and while he will come to incorporate traits of both, he is soon drawn into the den of the 'potheads.' Over the course of a few weeks, the platoon is involved in battle situations and actions of war several times, as it explores a booby-trapped bunker complex and loses some of its men; as the soldiers enquire about hidden weapons in a rustic village and come close to perpetrating a My Lai-type massacre; and as they are caught in an ambush and hit by friendly fire on patrol in the woods. Throughout these scenes, the animosities and rivalries between Barnes and Elias increase to the point where Barnes secretly murders his fellow soldier whom he perceives as a threat to successfully fighting and winning the war. In a furious climax, the platoon's position is overrun by VA forces and bombarded by the US Air Force. In the ensuing chaos, Chris takes revenge for Elias's death and shoots Barnes whom he has recognized as the responsible party. Injured, he is flown out of the battlefield.

War (Film) and the Feminine

It does not take much to realize that Platoon is doing without any female character of more than marginal importance. Where women appear at all, they figure as the victims of war atrocities and as sexual objects, or early on in the film as the absent receiver of the occasional letter home. Generally, though, Platoon presents a thoroughly male world where a lack of women is neither deplored nor, in fact, remarked upon. In the context of its genre, this consistent absence of female elements in narration and presentation is extremely rare. As has repeatedly been observed also in relation to the homo-social worlds of the generic Western movie, the occasional female character is important not only to slow down the narration and confront the male hero with moral and/or emotional conflicts; also, women characters are necessary in order to make sure that any sexual energy accumulating on the screen can find its place in socially indubitable heterosexual arrangements (cf. Esders; Neale).

Indeed, as Steve Cohan and Ina Rae Hark write in the introduction to Screening the Male (1993), "because the spectatorial look is so insistently male the erotic elements involved in the relations between the spectator and the male image have constantly to be repressed and disavowed" (3-4). Introducing a female character into the narration does, then, not only allow the (straight) male gaze to engage with a female form and avoid anxiety, it also helps disperse any doubts about the male heroes' sexual orientation and desires. Juxtaposed to a female object of desire, they smoothly assume their assigned places in a heteronormative society and are removed from the suspicion of homoerotic tendencies.5

At the same time, as philosopher Bar-On Mat-Ami has observed, especially in war films, women represent a 'rehumanizing power,' a moral force that counteracts the 'dehumanizing power' represented by the male. Where men kill and hurt and mistreat, women care and heal and cure. Without women's association with life, Mat-Ami argues, men, in their serious engagement with death, would not be able to come back home from the war and into their societies as whole human beings. If Platoon can do without any central female characters in its plot, she concludes, it is because the power to rehumanize is untypically attributed to a male character: Sergeant Elias.

Performing Masculinities, Differently

In fact, the two squads that the platoon is divided up into do not only stand for different choices of leadership and different preferences of night time entertainment; they also represent two different versions of masculinity.

On the one side, there are the 'Lifers' under the moral leadership of Sergeant Barnes: a predominantly Anglo-American circle whose members gather around beer, bourbon, and poker games. They share and enjoy heterosexual pornography and pride themselves in their physical strength. Bunny's (Kevin Dillon) proud display of his ability to bite a piece of aluminum from his beer can is one of the more curious proofs of excessive virile power. The atmosphere with the Lifers is sober as they sit in their well-lit tent, avoid physical contact with each other and preferably talk about sex and death. Barnes is the figurehead of their straight and no-nonsense masculinity: with his natural authority and self-denying courage he represents the classical, if not to say stereotypical, male hero. His association with weapons and his dedication to merciless fighting as well as his disfiguring scars6 clearly speak of his association with death and destruction.7 In the terminology of Mat-Ami, then, Barnes and the Lifers stand for a masculine, dehumanizing power. In the context of gender analysis, they represent a conventional, socially sanctioned and heteronormative way of being a man.

The pot-smoking 'Heads' around Elias, on the other hand, display a masculinity that is characterized by communal singing and dancing, by rituals of male bonding that involve uninhibited physical contact and a vague element of homoerotic seduction. Where the Lifers are basically passing time, the Heads' approach in their smoky, dimly-lit and altogether comfortable den is a considerably more dionysian one. The camera lingers on the naked, sweating bodies of dancers from different ethnicities and zooms in to a far greater closeness than it ever does with the Lifers. In this subtly homoerotic environment, Elias introduces stronger hints of queerness as he welcomes Chris into their community. Rather untypical of a courageous and responsible authority figure in a war movie, he acknowledges Chris's presence by waving at him, languidly reclined in a hammock, only half-clad, and sensually eating a banana. The ceremony of initiation that he performs later on with newly recruited Chris involves not only the passing of marihuana smoke through the phallic barrel of a gun but is also accompanied by a conspiratorial look and smile on the side of Elias and a somewhat curious yet disconcerted gaze by Chris – as though he were checking if anyone might watch and disapprove of this erotically charged moment. With its homoerotic overtones, the scene is strikingly reminiscent of the sexually coded passing of smoke through a straw in Jean Genet's gay prison art film, Un Chant d'Amour (1950), and it dissolves into a scene of soldiers relaxedly dancing with each other.

On the pictorial level, Elias's masculinity is coded as deviant and somewhat queer – especially in relation to the conventions of the genre. In excess of representing moral integrity, or, with Mat-Ami, the rehumanizing power in a dirty war, then, Elias might be considered to bear certain traits conventionally perceived as feminine: he is sensuous, emotional and caring, he promotes singing and dancing, and he cherishes romantic settings, as in the intimate conversation he has with Chris under a densely starred night sky with its obligatory shooting star.

Oedipal Structure

The film's distribution of characteristics traditionally conceived as masculine and feminine is underscored by the oedipal structure that governs the relationship among its three protagonists.8 When Chris is flown out of the battlefield, he ponders his experiences in Vietnam and observes: "I have felt like the child of these two fathers," Elias and Barnes. Given Mat-Ami's thesis, this would leave Elias in the position of the 'mother,' Barnes in the position of the 'father,' and Chris as the boy child of both. Indeed, the constellation between the characters repeats the traditional structure of desire, envy, and inclination to patricide developed by Sigmund Freud in Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie (Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality; 1905).

Chris and Elias soon develop a very strong bond that reverberates with a certain sexual desire (cf. the ritual of initiation discussed above). At the same time, Chris admires Barnes for his virility, his skill as a masculine, weapon-bearing leader. When, in what might be conceptualized as a primal scene, however, Chris realizes that Barnes 'fucks' with Elias, that he has in fact penetrated him with a projectile from a phallic gun, the symbolic son is rapidly possessed by the ardent wish to kill the symbolic father. By executing the patricide at the end of the film, Chris 'becomes' his father, he identifies with Barnes which enables him to dispose of the father and assume his position himself: "Only thing can get Barnes … is Barnes," Rhah (Francesco Quinn) observes in a preceding scene.

However, in a place like Stone's Vietnam, the Law of the Father does not go unchallenged, and rather than finding a stable place in the oedipal economy, Chris rises as a new brand of man, as the son of two fathers. He combines in himself the humanity and sensitivity of Elias and the toughness and violent relentlessness of Barnes. Achieving this feat, then, he does not only do justice to his oft-remarked upon association with Christ, heralding the advent of a new kind of man. Also, he follows the pattern of the classical Western hero's journey into the unknown, his confrontation with the moral darkness without and within him, and his ultimate rebirth as a more complete man, as one who can rightfully help construct a new and improved society.

Gatekeepers and Gendertroublers

The toting and wielding of the phallic gun – an instrument that, in the key scenes of the film, is presented as clearly ambivalent in its function in that it represents the possibility for both pain and pleasure – might be connoted with a certain jouissance.9 Nevertheless, the killings of Elias and Barnes are all essentially presented as jobs that need to be done, leaving the respective perpetrator disgusted, depressed, if not suicidal. Thus, after shooting Elias in the woods, Barnes resorts to getting heavily drunk. "I got no fight with a man does what he's told," he explains, "but when he don't, the machine breaks down, and when the machine breaks down, we break down. And I ain't gonna allow that."

Barnes, then, does not kill so much for the satisfaction of violent drives, but in order to guarantee the continuation of a system that he decidedly approves of. And just as he is prepared to take any necessary measure to win the war for his country, so he is ready to kill whoever provides a threat to the stability of the social machine that produces gendered – and straightly gendered – bodies for a heteronormative regime.10

"Elias is a troublemaker," Lieutenant Wolfe (Mark Moses) establishes at one point in the film – and indeed, Elias complicates and threatens to break up hegemonic gender structures. In addition to well-established elements of masculinity,11 his performance of being a man includes slippages, actions and ways of behavior that connote queerness and that do not quite fit into the heterosexual matrix. As he so frequently does in the film,12 Barnes takes responsibility in the face of these challenges to an established order and assumes the role of gatekeeper, of border patrol of the dividing line between morally sanctioned, 'correct' and deviant, 'wrong' performances of being a man. Elias, as an obvious threat to the heteronormative system, is punished in a way that exemplifies Judith Butler's observation that "we regularly punish those who fail to do their gender right" (1999: 178).13

In the case of Chris's murder of Barnes, things lie slightly differently: Chris doubts the prevailing system and wants to have it changed.14 "It's the way this whole thing works," he explains his lethargy after Elias's death. "People like Elias get wasted and people like Barnes just go on making up rules any way they want […]." For him, Barnes is revealed as (one of) the bearer(s) of a conformity proscribing system. Chris, however, has come to appreciate different ways of being and, under Elias's influence, has matured into a promoter of a far less restrictive gender system. So that eventually, Barnes himself has to die for his role and function in a system that might be about to come to an end as Chris surges from the ideological battlefield as the new, and more complete, man.

The 'child of those two fathers,' Barnes and Elias, Chris comes to integrate both their dehumanizing and rehumanizing powers. From Elias, he inherits tolerance and flexibility as much as the appreciation of the deviant and different; from Barnes, on the other hand, he takes the skills and abilities of the efficient gatekeeper. Returning home, one is bound to believe, Chris does not only carry the change that Vietnam has effected on him back into a United States society. Also, he might serve as both the constructor and the guard of a more flexible and comprehensive gender system, one that allows for deviantly doing one's gender and whose borders may, at the same time, be effectively defended against the infringement of delimiting and homogenizing forces.

Coda

Steve Cohan and Ina Rae Hark have remarked in relation to the "considerable force of the male in Hollywood cinema": "The scant attention paid to the spectacle of men ends up reinforcing the apparent effacement of the masculine as a social construction in American culture." Mainstream cinema, they claim, "screens out socially unacceptable and heterogeneous cultural constructions of masculinity" (2-3).

Platoon, while still offering itself as a realistic and authentically scripted representation of the Vietnam experience, does address as well as negotiate the construction of maleness in a heteronormative environment. The way that the film brings to the fore issues of masculinity and discusses the repressive forces inbuilt into any social system makes it stand out among mainstream films of any genre.

Christina Judith Hein, "Battleground Masculinity: Gendertroublers and Gatekeepers in Oliver Stone's Platoon (1986)," Current Objectives of Postgraduate American Studies, vol. 8, Mar. 2012

Endnotes:

1 The other two were Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket (1987) and John Irvin's Hamburger Hill (1987). Earlier films had presented the Vietnam war in the frame of a traditional Western plot (as did Ray Kellogg's and John Wayne's The Green Berets of 1968), as a psychedelic drug trip into the heart of moral darkness (Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now of 1979), or had primarily focused on the challenges that awaited both returning veterans and their home communities in the United States (the so-called homecoming films, with Hal Ashby's Coming Home of 1978, Michael Cimino's The Deer Hunter of the same year, and Ted Kotcheff's First Blood of 1982 as outstanding examples).

2 The issue appeared on January 26, 1987.

3 See the Works Consulted list at the end of this article for a complete account of scholarly articles on Platoon.

4 This essay is much inspired by the thoughts that Judith Butler has so poignantly formulated in her influential Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity of 1990. It must be noted that Gender as well as Queer Studies have evolved considerably since the film's release in 1986, so that a critical look at the film and its negotiation of masculinities from today's perspective is warranted.

5 In the context of the productive power of censorship of speech in Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative (1997), Judith Butler remarks that "[i]n relationship to the masculine military subject, […] the norms governing masculinity will be those that require the denial of homosexuality" (131). The structural properties in films that center on homosocial communities and that portray a very conventional straight notion of masculinity (war films, Westerns, crime and mafia films) conform to this observation.

6 Over the course of his deployment in Vietnam, we learn, he has been shot and recovered seven times. Barnes is virtually deathless and can, as it turns out later on, only be killed by consent.

7 Or, as John Stone poignantly puts it: "Barnes could serve as the poster boy for anger" (82).

8 Freudian psychoanalysis and Hollywood mainstream narratives have existed in very close association, as has been remarked, among others, by Glen Gabbard. That entertainment film and psychoanalysis share the 1890s as their era of emergence in Western cultures is often taken to underscore their close connections. Interestingly, Sigmund Freud was himself approached by Samuel Goldwyn to collaborate on a love film about Anthony and Cleopatra, but he declined.

9 Again it is Bunny with his sadistic pleasure in the raid of the village who best exemplifies the excitement connoted with the use of a gun.

10 That Barnes should order Elias's men to "get back to church" when, in fact, he wants them to return to the specific ruin of a church where the platoon are regrouping, is telling in this context. His intention to get his soldiers 'back in line,' to get them to adhere to the doctrines of heteronormative gender conventions reveals itself in the grammatical slippage of his command.

11 It must not be overlooked here that in relation to conventionally approved performances of masculinity, Elias's way of being a man is excessive rather than deficient. His inclinations to queerness do not in any way stand in opposition to his qualities as an outstanding soldier but are complementary, additional. In this respect, Elias's gender performance combines a variety of differently coded traits, thus constituting an ever more subtle challenge to the fiction of a clearly discernible borderline in a binary gender system.

12 Barnes is invested in the film with the ability to see clearly through complexities and complications, and he is even credited by Chris as the man "at the eye of our rage – […] through him, our Captain Ahab – we would set things right again." Embodying the straight eye of the platoon's small-scope ersatz-society, it is Barnes's role and function to 'set things right again' where they have gone amiss. That he should draw from this strength and straighten out a queered gender order by disposing of Elias is therefore much in line with his character's setup.

13 It is important to note here, however, that whereas on the level of narration, Elias is punished for his deviant behavior, the film goes on to sanctify him, on the pictorial level particularly. The depiction of his death scene employs iconographic elements of a Christian tradition. Running from the woods and onto a clearing, pursued and repeatedly shot by enemy VA soldiers, Elias, like Christ under the cross, falls once, then twice. In a dramatic posture, he drops to his knees, flings his arms skywards, the film jumpcuts closer and closer to his face. Elias remains as in a position of crucifixion before the film further emotionalizes the sequence by repeating the moment of the last, deadly shot in slow motion. Samuel Barber's Adagio for Strings adds a note of tragedy as do the reaction shots to Chris who observes the goings-on from an elevated vantage point. Like Christ, one is bound to infer, Elias is sacrificed for a higher cause.

The very sober execution of Barnes at the movie's end, mainly in full shot, stands in stark contrast to the spectacle of Elias's death. And while Barnes, tellingly, is killed after he has received a bullet wound uncomfortably close to the crotch, after an attack at his virility, that is, Elias maintains his queer position. As Laura Mulvey has noted in her influential essay, "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" (1974), it is usually the female figure that is turned into a "to-be-looked-at" spectacle on the screen – with the cutting up of her body by means of fetishizing close ups as a recurring stylistic device. Steve Neale, in "Masculinity as Spectacle" (1993), reads the violent intrusion on male bodies in war films as a way to mediate a desiring male gaze, to mark the male body as an erotic object that may be voyeuristically gazed at (16-18). In death, then, Elias evades the degradation and punishment that Barnes, in his role as gatekeeper of a heteronormative gender system, attempts to impose upon him, leaving open a number of queer strands.

14 As such, Chris himself becomes a part that does not 'function properly' and threatens to break down the machine that Barnes stands in for. The sergeant's battle crazed attempt at Chris's life just seconds before the final air strike might well be read in that vein. (On the moral plain, this scene establishes a connection between Barnes and a certain demoniacal force. Beside himself with rage, red-eyed, and ready to kill, he raises his arms in a way vaguely recalling Elias's death scene. The fiery and hellish lighting behind him, however, underscore an association with evil, as he is about to smash in Chris's head with a shovel. The opposition between Barnes and Elias is clearly stressed by these moments of Christian and Satanic contextualisations).

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. New York: Routledge, 1997.

—. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Cohan, Steven and Ina Rae Hark. "Introduction." Screening the Male: Exploring Masculinities in Hollywood Cinema. Ed. Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark. London: Routledge, 1993. 1-8.

Esders, Karin. "The Return of Femininity: Romance and Reminiscences in the Western Film." Popular Culture in the United States: Proceedings of the German-American Conference in Paderborn, 14-17 September 1993. Ed. Peter Freese and Michael Porsche. Essen: Die Blaue Eule, 1994. 235-43.

Freud, Sigmund. Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie. Wien: Deuticke, 1947.

Gabbard, Glen O. "The Psychoanalyst at The Movies." International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 78 (1997): 429-34.

Halberstam, David. "Platoon: Viet Nam As It Really Was." Time Magazine 26 January 1987: 54-62.

Mat-Ami, Bar-On. "Platoon and the Failure of War." Sexual Politics and Popular Culture. Ed. Dyane Raymond. Bowling Green: Popular P, 1990. 211-18.

Mulvey, Laura. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." 1974. Film and Theory: An Anthology. Ed. Robert Stan and Toby Miller. Molden: Blackwell, 2000. 483-509.

Neale, Steve. "Masculinity as Spectacle: Reflections on Men and Mainstream Cinema." Screening the Male: Exploring Masculinities in Hollywood Cinema. Ed. Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark. London: Routledge, 1993. 9-20.

Platoon. Dir. Oliver Stone. USA, 1986.

Stone, John. "Evil in the Early Cinema of Oliver Stone: Platoon and Wall Street as Modern Morality Plays." The Journal of Popular Film and Television 28.2 (2000): 80-87.

Un Chant d'Amour. Dir. Jean Genet. F, 1950.

Works Consulted

Bates, Milton. "Oliver Stone's Platoon and the Politics of Romance." Mosaic: Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 27.1 (1994): 101-21.

Beck, Avent Childress. "The Christian Allegorical Structure of Platoon." Screening the Sacred: Religion, Myth, and Ideology in Popular American Film. Ed. Joel W. Martin and Conrad E. Oswalt Jr. Boulder: Westview Press, 1995. 44-54.

Christopher, Renny. "Negotiating the Vietnam War Through Permeable Genre Borders: Aliens as Vietnam War Film, Platoon as Horror Film." LIT: Literature Interpretation Theory 5.1 (1994): 53-66.

Dalton, Mary and Jarrett Steve. "Platoon: The Fiction of History." Creative Screenwriting 3.2 (1996): 19-30.

Doyle, Jeff. "Missed Saigon: Some Recent Film Representations of Vietnam." Crossing Cultures: Essays on Literature and Culture of the Asia-Pacific. Ed. Bruce Bennett, Jeff Doyle, Satendra Nandan and Loes Baker. London: Skoob, 1996. 91-99.

Ecker, Michael. "Vietnam in the Genre Film: Essential Vocabulary of an Imaginary Hollywood File on Various Devices Expedient for the Success of (War) Movies." Modern War on Screen and Stage / Der moderne Krieg auf der Bühne. Ed. Wolfgang Gortschacher and Holger Klein. Lewiston: Mellen, 1997. 163-78.

Halberstam, David. "Platoon." Oliver Stone's USA: Film, History, and Controversy. Ed. Robert Brent Toplin. Lawrence: U of Kansas P, 2000. 110-19.

Hedges, Andrew. "Inter(Active)Textuality: An Examination of Platoon as a Film and as a Simulation Game." Kodikas 14.1-2 (1991): 175-83.

Helt, Richard C. "Kulturkritik or Anti-Americanism? The Reception of Recent Popular American Cinema in West Germany, with Special Focus on Platoon." Journal of Popular Culture 25.3 (1991): 189-97.

Hilbish, Melissa. "'Isn't It Just a Movie': Lessons Learned from Oliver Stone and Platoon." Reader: Essays in Reader Oriented Theory, Criticism, and Pedagogy 38-39 (Fall 1997 – Spring 1998): 42-62.

Jeffords, Susan. "Masculinity as Excess in Vietnam Films: The Father/Son Dynamics of American Culture" [with a reply from Claudia Springer]. Genre: Forms of Discourse and Culture 21.4 (1998): 487-522.

Kinney, Judy Lee. "Gardens of Stone, Platoon, and Hamburger Hill: Ritual and Rememberance." Inventing Vietnam: The War in Film and Television. Ed. Michael Anderegg. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1991. 153-65.

Klein, Michael. "Historical Memory, Film, and the Vietnam Era." From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film. Ed. Linda Dittmar and Gene Michaud. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1990. 19-40.

Large, Ron. "Platoon: Fear, Loathing, and Salvation in Vietnam." Journal of Evolutionary Psychology 11.1-2 (1990): 116-23.

Lichty, Lawrence W. and Raymond L. Carroll. "Fragments of War: Platoon (1986)." American History / American Film: Interpreting the Hollywood Image. Ed. John E. O'Connor and Martin A. Jackson. New York: Ungar, 1988. 273-87.

Palmer, William J. "Symbolic Nihilism in Platoon." America Rediscovered: Critical Essays on Literature and Film of the Vietnam War. Ed. Owen W. Gilman Jr. and Lorrie Smith. New York: Garland, 1990. 256-74.

Porteous, Katrina. "History Lessons: Platoon." Vietnam Images: War and Representation. Ed. Jeffrey Walsh and James Aulich. New York: St. Martin's, 1989. 153-59.

Ringnalda, Donald. "Unlearning to Remember Vietnam." America Rediscovered: Critical Essays on Literature and Film of the Vietnam War. Ed. Owen W. Gilman Jr. and Lorrie Smith. New York: Garland, 1990. 64-74.

Schechter, Harold and Jonna G. Semeiks. "Leatherstocking in 'Nam': Rambo, Platoon, and the American Frontier Myth." Journal of Popular Culture 24.4 (1991): 17-25.

Schneider, Tassilo. "From Cynicism to Self-Pity: Apocalypse Now and Platoon" [with replies from Anthony R. Guneratne and Terry Dibble]. Cinefocus 1.2 (1990): 49-59.

Taylor, Clyde. "The Colonialist Subtext in Platoon." From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film. Ed. Linda Dittmar and Gene Michaud. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1990. 171-74.

#oliver stone#platoon#scholarly articles#academics#journals#academia#gender in platoon#gender studies#lgbt studies

1 note

·

View note