#comparison to medieval monks

Text

"A god of tengu-warding": uncovering the connection between Okina and tengu

There’s something uniquely magical and captivating about Okina’s dialogue in HSiFS that neither subsequent final bosses nor even her own subsequent appearances manage to capture. Probably no other character managed to directly reference quite as many myths and religious concepts in her debut game appearance. And yet, without context many of these probably seem borderline nonsensical. Interviews and supplementary material sometimes help, but even that isn’t guaranteed.

This article will focus on only one such instance, the notoriously mystifying exchange between her and Aya which simultaneously casts her as a “god of tengu-warding” and implies a degree of kinship between them. What does this mean? Why does Okina have something to do with tengu in the first place? Where do tengu come from, anyway? Why crow tengu aren’t necessarily crows? Why is it possible to make a case for Byakuren being a tengu? This - and more - will be explored under the cut.

Matarajin and tengu, from tengu odoshi to Hidden Star in Four Seasons

In Aya’s route in Hidden Star in Four Seasons, Okina calls herself “a god of tengu-warding”. This is actually not something ZUN invented. Matarajin was the focus of a medieval Tendai Buddhist ritual known as tengu odoshi (天狗怖し) - “placating the tengu”. He was most likely himself understood as a tengu in this context. As such, he had to be placated by the monks performing the ritual, whose chaotic actions - chiefly noisy recitation of random sutras coupled - were meant to imitate his own behavior.

This approach is somewhat unusual: in many other similar ceremonies an appropriate deity or deities would simply be invoked to get rid of demonic interlopers. Here the risk of obstruction is so great that only by pretending to play along with it victory can be attained. Or, alternatively, perhaps to get rid of Matarajin and other tengu, the monks had to beat them at their own game by creating an even more disorderly display. Yet another option is that Matarajin had to be attracted with the ritual in order to ward off other, lesser tengu. No matter which interpretation is correct, it is evident there was a direct connection between them.

Matarajin and his attendants (Rhode Island School of Design Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

As a curiosity it’s worth pointing out that it has been suggested that tengu odoshi and other similar rituals and festivals might have resulted in the development of Matarajin’s well known role as a deity of the performing arts, especially noh, exemplified by his equation with a stock character from sarugaku, Okina, an auspicious old man represented by a characteristic bearded mask. Comparisons have also been made between the tengu odoshi and rituals involving Matarajin’s attendants Chōreita Dōji (丁令多童子) and Nishita Dōji (爾子多童子). Fittingly, one of the spell cards of their Touhou counterparts Mai and Satono is named Mad Dance "Tengu-Odoshi".

Shizuka Gozen performing in typical shirabyōshi attire, as depicted by Hokusai (wikimedia commons)

While this is only tangentially related to Matarajin, it’s worth pointing out that according to Yasurō Abe, it was also believed that tengu were enthusiasts of the performing arts in general. However, while Matarajin was associated with noh, tengu favored an earlier form of entertainment, shirabyōshi (白拍子). This term refers to a type of female dancer who performed in male formal wear. The reference to tengu enjoying their dances and songs might be an allusion to emperor Go-Shirakawa, who was known for similar artistic tastes and was commonly represented as a tengu in legends.

The association between Matarajin and tengu was also present in shugendō. In Kumano, local shugenja apparently perceived him as a tengu-like deity comparable to Iizuna Gongen (飯縄権現). It’s worth noting this is in theory who Megumu is based on, but tragically ZUN didn’t want to do much with the irl background in her case, so I doubt we'll ever see a reference to this in canon media.

An Edo period depiction of the ox festival of Matarajin (wikimedia commons)

It seems the only other possible reference to Matarajin as a tengu is a depiction of the famous (relatively speaking) Kōryū-ji ox festival from the Edo period Miyako Meisho Zue (都名所圖會) in which the person playing his role wears a tengu-like mask.

Considering ZUN has to be aware of at least some of the scholarship pertaining to Matarajin and tengu - tengu odoshi is not exactly a famous ritual, and most of the search results today are just Touhou - it seems safe to say that he had this very connection in mind. Aya mentions a category of beings she refers to as “people of impairments”, which according to her encompasses both the tengu and their metaphorical relatives who “hid behind Buddhas”, like Okina. This neatly corresponds to their shared role of their counterparts in medieval and early modern Buddhism.

In addition to the connections between Matarajin and tengu discussed above, there are multiple other instances of identifying him as a member of a category of beings usually perceived ambivalently, if not outright negatively, specifically because of their ability to impair the pursuit of enlightenment. If you read my previous post focused on Okina-adjacent topics, you already know that Matarajin was closely associated with dakinis, for instance. It’s worth noting that as an extension of this connection, he could also be associated with foxes. The Edo period treatise Inari Jinja Kō (稲荷神社考, “Reflections on Inari Shrine”) outright says that matarajin, treated as a generic term, not a given name, is one of the the terms which can be used to refer to supernatural foxes.

The oldest presently known reference to Matarajin describes him as a “yasha deity” (夜叉神, yashajin). This term is a loan from Sanskrit yakṣa, and refers to a class of nature spirits or low-ranking deities incorporated into Buddhism from preexisting tradition of India. They are portrayed as generally benevolent and protective. To be a yaksha in origin is no shame for a deity, despite their low status and occasional ambivalence. Bishamonten, who needs no introduction, as well as Konpira, the foremost of the Twelve Heavenly Generals, are both portrayed as yakshas who embraced Buddhism. Even the bodhisattva Kannon seemingly was portrayed as a reincarnation of a female yaksha named Cundī early on. In both China and Japan, the most widespread image of a yaksha is ultimately that of an armed, protective figure.

However, sometimes negative traits can be ascribed to yakshas too. For instance, the Tang period Buddhist scholar Guifeng Zongmi maintained that yakshas are child-eating demons - though he also recorded a custom of dedicating children to them in order to prevent them from harm. The tenth century Tendai monk Genshin stated they were among demonic beings who could potentially obstruct rebirth in a pure land. However, it was possible to solve this problem with the right rites.

The examples listed above are just a few glimpses of one of the most recurring topics in historical Japanese Buddhist literature: there were demons, and even deities (障礙神, shōgejin) keen on impairing the pursuit of enlightenment unless properly placated. This would either ward them off, or even turn them into fierce protectors of Buddhism instead (what ZUN presumably meant by Aya’s comment about “hiding behind Buddhas”). However, most of such beings originated in India and spread alongside new religious movements. How did tengu join their ranks? To answer this question, I will need to go beyond Matarajin and further back in time, to the Heian and Kamakura periods.

Makai, the realm of tengu

A group of Tengu constructing a temple in the tengu realm (wikimedia commons)

The emergence of tengu as a well defined class of beings is fundamentally tied to portraying them as a source of hindrances for practitioners of Buddhism. In the twelfth century, they came to be identified with the concept of ma (魔), a loanword from Sanskrit māra. In this context, it is to be understood as obstruction of enlightenment, or opposition to the Buddha, his teachings and the Buddhist law. There are both internal sources of ma, like doubt and worldly attachment, and external ones. Tengu, generally speaking, fall into the second category.

Tengu were believed to be reincarnations of those who lack bodhicitta (菩提心, bodaishin), the mindset necessary to pursue enlightenment. Those who become tengu at least nominally follow Buddhist teachings, but fail because of arrogance, greed and other earthly attachments. Those who mislead others by promoting incorrect practices also turned into tengu after death.

Many tengu narratives from the Heian period and the middle ages portray them as possessing extraordinary powers, which they use to trick and mislead monks and laypeople alike. They could be referred to as gejutsu (外術), literally “outside techniques”. A related term is gedō (外道), “outside way”. These labels are not necessarily pejorative, and can refer to any practices which are not strictly Buddhist, for example to Confucian or Daoist ones, and in fact some were integrated with Buddhist practices. However, depending on context other options might be preferable. For example, Haruko Wakabayashi went with “wicked sorcery” in her translation of a Konjaku Monogatari tale in which a tengu poses as a buddha in order to mislead laypeople. However, even if tengu could imitate miracles Buddhas and bodhisattvas were believed to perform, their results were only temporary because they lacked true power. In many tales the effects of tengu tricks only last seven days.

According to the Kamakura period anthology Shasekishū (沙石集), not all tengu are malicious, despite their origin. Those who are close to being redeemed, while held back by “superficial wisdom”, curtail the influence of their more malevolent peers and thus act as protectors of Buddhism. They eventually leave the realm of tengu. Other sources indicate that the malign tengu are destined to eventually be reborn as animals.

As already pointed out above, the notion of tengu being opponents of Buddhism already appears in Konjaku Monogatari, composed between 1120 and 1140. The tales involving them appear in the final chapter of the section focused on Buddhism in Japan, which sets them apart from most other supernatural beings. They are instead grouped with accounts of visits in hells and other realms of rebirth, and with narratives explaining the consequences of accumulation of bad karma.

In the Kamakura period, tengu received their own place in the Buddhist cosmos: an entire realm of rebirth. It didn’t replace any of the three other realms where one reincarnates as punishment due to accumulating bad karma - these of hungry ghosts, animals, and hell. It could be sometimes described as a specific hell (one of many) or as a part of the animal realm, but generally it was held to be something distinct. While still perceived negatively, it can effectively be considered a preferable alternative to rebirth as an animal or in hell, since to be reborn as a tengu does not necessarily prevent one from seeking enlightenment.

The realm of tengu was variously referred to as tengudō (天狗道; “realm of tengu”), madō (魔道; “realm of ma”) or makai (魔界; “world of ma”). The last of these terms has been present in Touhou for a while, though never in association with tengu, at least for now. I am aware many people are attached to the PC-98 portrayal of Makai and to Shinki, but I would argue there are endless possibilities in trying to make the medieval understanding of this term work in this context as well. Most notably, the notion of monks who failed in their pursuit of enlightenment would have interesting implications for Byakuren. Following medieval Buddhist logic, one could argue she is essentially already a tengu, even though ZUN refers to “sealing” in Makai, as opposed to being reborn there. She may deny it herself in Symposium of Post-Mysticism, but it's hard to argue with the evidence.

The oldest work establishing the existence of tengudō as a distinct realm of rebirth is Hirasan Kojin Reitaku (比良山古人霊託; “The Spiritual Oracle of the Old Man of Mount Hira”), in which the Tendai monk Keisei (1189–1268) learns about it from a tengu residing on Mount Hira. While left anonymous, the being states that he was alive in the times of Shōtoku and before the rise of Fujiwara no Kamatari to prominence, and explains that due to worldly attachments he was reborn in the realm of tengudō. He then provides information about many of Keisei’s family members and contemporaries, as well as assorted historical figures. Some of them have shared a similar fate, including emperors Sutoku and Goshirakawa and prominent members of Buddhist clergy like Ryōgen, Jien, and many others. Keisei and the anonymous tengu then engage in what I can only describe as a vintage example of power scaling, and start to compare the strength of the individual tengu (as we learn, Go-Shirakawa is more powerful than Sutoku).

Curiously, the anonymous tengu is entirely self-aware, and explains that his mind is filled with illusory thoughts, but proper Buddhist observance can nonetheless save him and other tengu from their current state. He notes that Ryōgen was able to leave the realm of tengu already, for instance. Another peculiar aspect of this account is the explicit reference to female tengu. The protagonist explains to Keisei that his wife is a fellow tengu, though she is only 400 years old. He also specifies many other tengu have families and even children.

A debate in the tengu realm (wikimedia commons)

The Buddhist views on tengu became firmly cemented thanks to the Tengu Zōshi (天狗草紙), a set of seven illustrated scrolls. This work most likely originally arose in the thirteenth century, in an era of conflicts between the well established esoteric schools of Buddhism, Tendai and Shingon, and the newcomers to the scene, like Zen and Pure Land. All parties involved accused each other of spreading false teachings and embracing ma. The new schools did not form a unified front, for clarity: for instance, Nichiren denounced the Shingon establishment about equally enthusiastically as Zen or Pure Land. There were also voices presenting the very act of criticism of other schools as worthy of critique in itself.

The goal of Tengu Zōshi was to criticize and satirize the various vices of contemporary Buddhist monks by presenting them as tengu. It states that there are seven kinds of tengu, corresponding to seven different sorts of pride (citing Haruko Wakabayashi: “feeling slightly inferior to those who are greatly superior, feeling superior to those who are inferior and equal to those who are equal, feeling superior to those who are equal and equal to those who are superior, feeling superior to those who are superior, being attached to oneself, committing evil and thinking one is virtuous, and feeling enlightened when one is not).

Five of the tengu types are supposed to represent monks of major temples of this era (Kōfuku-ji, Tōdai-ji, Enryakuji, Onjō-ji, and Tō-ji), the remaining two are yamabushi (mountain ascetics) and “recluses” (tonse). However, the scrolls culminate with a reveal that all of the depicted tengu attained salvation and eventually became Buddhas (save for Ippen, who was instead destined to be reborn in the animal realm). This once again puts an emphasis on tengudō not being quite as bad as the other paths of rebirth which should generally be avoided: one has to actually practice Buddhism in some form to get there in the first place, and it is possible to attain enlightenment as a tengu.

The notion of tengudō and tengu being fallen monks did not vanish after the middle ages, and appears for example in some tales about Yoshitsune’s youth and his training with these beings, for instance in the Miraiki (未来記; literally “chronicle of the future”). Therefore, it is safe to say that this is the closest thing to a universal explanation where do tengu come from. However, their history actually goes even further back.

Cats, comets, dogs and kites: the origin of tengu

A tiangou from the Classic of Mountains and Seas (wikimedia commons)

The history of tengu starts in China. At least the history of the name, that is. The word 天狗, which in Chinese is read as tiangou, already occurs in the Classic of Mountains and Seas, probably composed at some point in the second half of the first millennium BCE, either near end of the Warring States Period or in the beginning of the reign of the Han dynasty. While tiangou can be literally translated “celestial dog”, the creature is actually compared to a wildcat with a white head, and makes catlike sounds on top of that. It is also said to repel evil forces. This quality is also reaffirmed by the poet Guo Pu, who additionally states the tiangou is so small that a ruler could either eat it or wear it as a belt ornament to make use of its protection.

Next to this whimsical image of a benevolent supernatural creature, the term tiangou was also used to refer to comets and similar celestial phenomena. This meaning of the term entered Buddhist texts, for example in the Sutra on the Bases of Mindfulness of the True Dharma (正法念處經, Chinese Zhengfa Nianchu Jing, Japanese Shōbō Nenshokyō), tiangou serves as a translation of the Sanskrit term ulka, which refers to meteors. The astral tiangou eventually developed its own supernatural associations in China, becoming a sort of dog-shaped astral demon. I cannot cover this topic extensively here, but you will find plenty of information, including a first hand account of a modern celebration tied to these traditions, in Xiaosu Sun’s article in the bibliography.

The earliest Japanese reference to 天狗 occurs in the Nihon Shoki (completed in 720), specifically in the section recording the events from the reign of emperor Jomei (593-641). The reason why I’m using the kanji here is that the reading is not necessarily intended to be tengu in this case; the gloss indicates it is actually to be read as amatsukitsune, “heavenly fox” (I’ll go back to this term later). However, Haruko Wakabayashi states it’s safe to assume that it was used here in the astronomical Chinese meaning. The passage refers to observation of a comet, which reportedly made the sound of thunder as it passed from east to west.

Some other early references to tengu occur in literature of the Heian period (794-1185). In this context, this term seems to refer to nondescript mountain spirits. They were believed to possess people to make them fall ill or to cause disorder. All around it seems they weren’t really meaningfully distinct from any other beings or phenomena which could be subsumed under the label of mononoke (物の怪), and it's not clear how their name came to be applied to them. In the early twentieth century, the folklorist Kunio Yanagita tried to prove these early tengu might have represented people pushed into the mountains by the spread of a centralized Japanese state. However, this theory never took off. Even some of Yanagita’s contemporaries, especially Kumagusu Minakata, were critical of it, and it’s just a weird curiosity today. Similar assumptions were proven correct in the case of tsuchigumo, and might be correct in the case of some oni tales, but these are matters for another time.

The supernatural form of Sutoku, as depicted by Yoshitsuya Utagawa (wikimedia commons)

Notably, in the Heian period it was already believed that one can reincarnate as a tengu, though this belief didn’t become quite as well defined as it was in later sources. Probably the oldest story like that states that the monk Shinzei (真済; 800-860) a disciple of Kūkai (774-835), became a tengu and subsequently tormented empress Somedono (染殿后; Fujiwara no Akirakeiko), the wife of emperor Seiwa. In later tradition, emperor Sutoku came to be viewed as the archetypal example of a human who reincarnated as a tengu; it should be noted he was simultaneously viewed as a vengeful spirit (怨霊, onryō), though.

A kite-like tengu, as depicted by Sekien Toriyama (wikimedia commons)

The well known association between tengu and birds is already present in Heian sources too. Today, the bird-like depictions of tengu are known as “karasu tengu”, literally “crow tengu”, and in many modern works, including Touhou, this moniker is taken literally. However, through history the birdlike elements of the tengu were typically those of a bird of prey, not a corvid. As I mentioned, kites were the most common, but for example some depictions of Iizuna Gongen are eagle-like. This convention might have been influenced by garudas, a class of bird-like Buddhist protective figures.

A depiction of a garuda from Besson Zakki (別尊雑記), a Heian period Buddhist iconographic compendium (via Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Descriptions of tengu explicitly mentioning their resemblance to kites are quite common. In Zoku Honchō Ōjōden (続本朝往生伝; “Continuation of the Biographies of Japanese Reborn in a Pure Land Continued”) Ōe no Masafusa (who you might remember from my Ten Desires article) mentions a tengu turning into a kite to spy on a virtuous monk. In the historical epic Taiheiki Sutoku, presented as the ruler of all tengu, is said to have the form of a golden kite. However, in at least some cases tengu are not necessarily birds themselves, but merely use them as mounts. Granted, both traditions could coexist: Hirasan Kojin Reitaku explains that tengu ride kites, but it also describes them as possessing the legs, tail and wings of a bird themselves.

The oldest source to feature a large number of images of bird-like tengu is the already discussed Tengu Zōshi. These include high-ranking monks with beaks, yamabushi or monks with wings and beaks, slightly more bird-like figures portrayed largely without clothing, and finally non-anthropomorphic kites. There are also illustrations of seemingly regular humans labeled as tengu. Haruko Wakabayashi concludes that the use of multiple distinct iconographic types in the same scrolls might reflect belief in a hierarchy of tengu, with the beaked monks representing the upper echelons of the tengu society and the other varieties their servants. The regular kites presumably hold the lowest position. The tengu world thus seems to reflect a contemporary idealized image of Buddhist hierarchy, with lower ranking practitioners, wandering ascetics and laypeople guided by senior monks.

ZUN kept the notion of tengu hierarchy, though the classes listed in the relevant entry in Perfect Memento in Strict Sense are largely his invention, or at least represent pretty extensive reinterpretation (for instance, tengu dressed up as yamabushi aren’t associated with printing in any particular way). While many of these changes work very well with his idea to adapt the traditional role of tengu as peddlers of dubious interpretations of Buddhist doctrine and false miracles with a fresh twist by making them purveyors of misinformation, I will admit I’m not sure where did the idea of wolf tengu come from, as it fits neither this theme nor any genuine tengu background. The wiki insists that’s a reference to the Chinese tiangou, but I’m not buying this.

Iizuna Gongen riding on the back of a celestial fox (wikimedia commons)

I would argue foxes would probably work better than wolves. In some cases due to phonetic similarity a degree of conflation, or at least confusion, could occur between tengu and tenko (天狐), “heavenly foxes”. The fourteenth century treatise Byakuhō Kushō (白寶口抄) states the tenko has the form of a kite, for instance. It’s also why Iizuna Gongen was sometimes referred to as Chira Tenko (智羅天狐). The link with foxes was hardly universal, though. For example, it is absent from the tradition centered on Mount Atago, in which in addition to birds, tengu are associated with wild boars. Note that a myth dealing with Iizuna Gongen’s arrival in Japan does indirectly link this location with foxes, but this is basically extending his own connections to other tengu.

While the discussed animal connections are quite important for tengu iconography, I was unable to find any evidence that there was ever a particularly strong belief in mundane animals turning into tengu, as Aya’s bio from Phantasmagoria of Flower View would imply. The only source I am aware of which would state that directly is Atsutane Hirata, one of the most fanatical kokugaku authors, and even he still states that at least some tengu were reincarnated Buddhists. Note that his works are generally not a record of genuine mythology or folklore, but part of an effort to “purify” Japanese culture which directly led to the birth of the “contemporary” form of expansive nationalism. In any case, Hidden Star in Four Seasons and the historical context of information it provides opens the possibilities for much more interesting and unique tengu backstories than just stage 2-worthy beast youkai fare.

To sum up, while individual stories might portray tengu as arriving in Japan from Korea (Tarōbō), China (Zegaibō and his prototype Chira Yōju) or even India (an anonymous tengu in Konjaku Monogatari), these reflect the routes across which Buddhism was transmitted to Japan. The tengu as a distinct supernatural creature had elements which originated abroad, obviously, but ultimately represented a strictly Japanese contribution to Buddhist demonology. At least some Japanese authors were already aware of this in the middle ages, as evidenced by the Shasekishū.

The three meanings of 天狗 - the tiangou, the astral object and the tengu - are explicitly described as distinct from each other in the encyclopedia Jakushōdō Kokkyōshū (寂照堂谷響集) compiled by the monk Unshō (運敞; 1614–1693). The original tiangou is described here as a type of tanuki which eats snakes, but this doesn’t exactly contradict the Chinese description I’ve mentioned before, as 狸, the character referring to wildcat in Chinese, was adopted to represent the name of tanuki in Japanese. The astral tiangou is described as a “tengu star” (天狗星, tengu-sei) which has the form comparable to a dog. Unshō stresses that both of these are distinct from the Japanese tengu, despite their names being written identically. He places the tengu in the entourage of Mara, alongside dakinis and vinayakas (in this context demons representing something like an evil counterpart of Ganesha as a remover of obstacles).

Beyond animals: the long nose tengu and Sarutahiko

A Meiji period depiction of Sarutahiko (wikimedia commons)

A final matter which needs to be addressed here is a theory that tengu imagery is derived from Sarutahiko, which for some reason has been placed in the lead of the tengu article on wikipedia despite being hardly relevant academically. This proposed connection relies on the fact that from the very beginning Sarutahiko was described as long-nosed. In the section of the Nihon Shoki dealing with the “age of the gods”, the oldest text he appears in, it is said that “his nose is 7 feet long”. His other physical characteristics are also exaggerated, to be fair - he is said to be unusually tall, and his eyes are enormous too. All around, this description is presumably meant to make him seem intimidating. Still, the nose is what visual arts tend to highlight, sometimes for comedic purposes.

A long-nosed tengu, as depicted by Hokusai (wikimedia commons)

This characteristic also led to a development of a folkloric connection between Sarutahiko and the one type of tengu depictions I haven’t discussed yet - the long-nosed tengu, commonly called daitengu or “great tengu”. The origin of this iconographic variant remains poorly understood. While by far the most recognizable today, they are a relatively recent artistic convention - the oldest examples only date to the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, and they only became widespread in the Edo period. By then, tengu were present in Japan for some 700 years, and Sarutahiko doesn’t come up in sources describing them (and vice versa).

It also needs to be stressed that while the daitengu still have some birdlike traits, Sarutahiko lacks a connection to birds altogether. Instead, he is associated with monkeys (tengu never are, contrary to an unsourced claim on wikipedia). Historically he could even be identified with Daigyōji (大行事), a deity from Mount Hiei depicted with the head of a macaque.

It’s not impossible that the specific long-nosed type of tengu depictions was based on depictions of Sarutahiko, but it’s equally likely the influence actually went into the opposite direction (most depictions of Sarutahiko are from the Edo period or later, and most shrines dedicated to him are fairly recently established too, even though he was worshiped in one form or another through earlier periods already).

A statuette of a dancer wearing a Raryō-ō costume by Shōmin Unno (Imperial Household Agency; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Bernard Faure notes it’s also not impossible that both Sarutahiko’s iconography and the long-nosed tengu are simply both reflections of something else altogether, and suggests the long-nosed Raryō-ō (羅陵王; sometimes shortened to Ryō-ō, 陵王) masks used in bugaku performances as one possible candidate. Ultimately none of these possibilities can be proven conclusively, though, and it’s best to maintain caution.

ZUN seems to believe there is some truth to the proposal that tengu were derived from Sarutahiko, judging from the fact he referenced this connection multiple times in various ways. The oldest example are Aya’s spell cards in Mountain of Faith. It also comes up in Symposium of Post-Mysticism, where Miko and Byakuren seem to basically treat it as a fact. Aya in one of the short articles from the same book declares that “when it comes to white beard in Gensokyo, we tend to picture Sarutahiko. (...) he is also the god of us tengu”. Putting aside the latter claim, which is bit of a reach when it comes to real beliefs, it’s worth noting that the mention of the white beard is a pretty deep cut. It was actually not a part of Sarutahiko’s original iconography, but rather an addition which developed at the Shirahige Shrine on the shores of Lake Biwa. Originally the local deity, Shirahige Myōjin (白鬚明神), was considered a distinct figure. However, at some point he came to be identified with Sarutahiko, and the names seem to be used interchangeably in medieval and later sources. As a result, the latter received the former’s signature white hair and beard.

While despite the existence of a genuine connection it is a stretch to call Sarutahiko a “god of tengu”, let alone their leader, this does not mean that figures which can be described this way are absent from tradition. In fact, I mentioned a number of them in passing in the previous sections. However, describing them in more detail a topic for another article. Look forward to "Tenma, boss of the tengu". Exploring the "heavenly demon(s)", coming next year!

Bibliography

Yasurō Abe, The Book of “Tengu”: Goblins, Devils and Buddhas in Medieval Japan

Bernard Faure, Protectors and Predators (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 2)

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Michael Daniel Foster, The Book of Yokai. Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore

Sarah Fremerman Aptilon, Goddess Genealogy: Nyoirin Kannon In The Ono Shingon Tradition in: Charles Orzech, Richard Payne & Henrik Sørensen (eds.), Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia

Wilburn N. Hansen, When Tengu Talk. Hirata Atsutane's Ethnography of the Other World

Richard E. Strassberg, A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways Through Mountains and Seas

Xiaosu Sun, Liu Qingti's Canine Rebirth and Her Ritual Career as the Heavenly Dog: Recasting Mulian's Mother in Baojuan (Precious Scrolls) Recitation

Haruko Wakayabashi, The Seven Tengu Scrolls. Evil and the Rhetoric of Legitimacy in Medieval Japanese Buddhism

Idem, Monks, Sovereigns, and Malign Spirits: Profiles of Tengu in Medieval Japan

Duncan Ryūken Williams, The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Sōtō Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The virtuous woman does not veil her body because she thinks that it is bad. Nor is she hiding herself from men. Rather, she is revealing her dignity to them.

A similar comparison could be made of how God revealed His glory to us through the Incarnation. While writing about the miracle of God becoming man in the person of Christ, an eighth-century monk said that Jesus was telling us:

I am covered by a cloud of flesh not that I may be hidden from those seeking me, but that I may be less bright for the sake of the weak. Let them heal the eyes of their minds, let them purify their ears, with faith, so that they may be worthy to look upon me. For "Blessed are the pure of heart since they will see God."1

Something similar could be said by the woman who dresses modestly:

I am covered by a cloud of modesty not that I may be hidden from the men seeking me, but that I may be less bright for the sake of the weak. Let them heal the eyes of their minds, let them purify their hearts, with faith, so that they may be worthy to look upon me. For "Blessed are the pure of heart since they will see God."

It is not arrogant for a woman to think of herself in such terms, believing that her body is a window of heaven. It's humble. Humility is nothing more than the truth, and the truth is that there's glory in the way a woman has been created. Perhaps this is why one brilliant medieval philosopher called the sensitivity to shame "a healthy fear of being inglorious."2 If that's true, one could argue that modesty is a healthy confidence of being glorious.”

-Jason Evert, How to Find Your Soulmate Without Losing Your Soul

1 St. Bede the Venerable, Magnificat

2 St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember, an elephant is not just for Christmas!

If you are a medieval ruler like Henry III who received an elephant from his brother-in-law (St) Louis IX of France in early December 1254, be prepared to spend:

£6 17 shillings 5 pence (refund to the sheriff of Kent for transporting the elephant from France to England)

£22 20 pence on a multi-purpose elephant house at the Tower of London

£24 14 shillings 3½ pence on food for the elephant every nine months

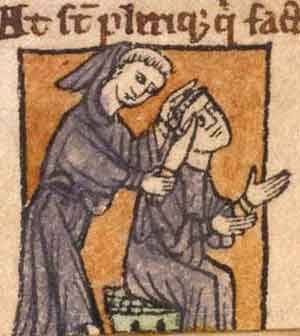

By comparison, a laborer might earn just 1-and-a-half pence per day, while a well-to-do knight might live on £15 per year. (For more, see Cassidy's and Clasby's article from the Fine Rolls of Henry III Project.) And don't forget, you will have to pay for the elephant's keeper, too! The monk-chronicler Matthew Paris helpfully depicted Henry III's elephants alongside one of its keepers for scale. The man is labelled as Henry de Flor, "mag[iste]r bestie" ("caretaker of the beast").

Sadly, Henry did not have these expenses for long: although many medieval legends emphasized elephants' longevity, this elephant only lived until 1257 in the inhospitable northern climate. When it died, it was initially buried in the tower, but Henry later had its bones transferred to Westminster Abbey.

Despite these difficulties and costs, elephants had a notable history as diplomatic gifts in the Middle Ages, even in regions where elephants did not naturally live. Charlemagne's elephant Abul Abbas is a very early example of the phenomenon, and by the eleventh century Byzantine emperors were receiving elephants in Constantinople. In 1228, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II received an elephant from al-Kamil, the ruler of Egypt, and King Louis IX probably also received his elephant from an Egyptian ruler before regifting it to Henry III.

Side note: although the "white elephant" gift exchange claims to be based on a southeast Asian ruler's practice of punishing courtiers with a gift that would cost them a lot of money, there is not much historical evidence for this before the story was shared in the Anglo-American world in modern era.

Some elephants fought back over being passed around as gifts, though. In the early 15th century an elephant and other rare animals arrived in Japan. (Martha Chaiklin has suggested that they were intended as a diplomatic gift for someone else, but were blown off course and ended up with the Ashikaga shogun.) The elephant was extremely grumpy and trampled some courtiers, so the shogun regifted it to Taejong, ruler of Korea. The elephant continued to trample courtiers in Korea and was expensive to feed, so Taejong exiled it to its own private island, where it continued to live.

Materials: parchment, ink, and pigments

Contents: Matthew Paris's Chronica Maiora

Origin: St Albans Abbey (made by the scribe-illuminator-chronicler-monk Matthew Paris)

Now Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 16 I, f. ii r

#elephant#elephants#medieval elephants#illuminated manuscript#13th century#medieval#elephants as gifts#unique gifts#medieval gifts#global middle ages#diplomacy

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Am I to understand correctly that what we believe about Irish paganism may not even be real? That it's just from the imagination of Medieval Christian monks?

Um... well yes but also no? All of our written sources for what Irish pagans believed and practiced are from NOT Irish pagans. So we have the classical sourses (Greek and Roman writers) who are mostly talking about the Gaulish tribes, as opposed to the Irish (or even the other insular groups) specifically and we have the Irish monks who wrote fairly extensively about what their pagan ancestors (for surviving manuscripts) or, possibly, what the pagans around them or maybe even what they believed before converting (in the earlier lost manuscripts which can be found in some fragments of the surviving texts).

This isn't particularly uncommon, Norse/Scandinavian myths and beliefs have a similar history. The Eddas were only recorded (by a Christian) so that scholars could continue to understand the praise poems about famous kings which used mythological comparisons.

So when looking at the texts we have to use discretion to try picking out what is propaganda or influence from the culture of the writer and what is authentic Irish Pagan beliefs. We also can draw from the archeological information avaliable to us and/or information we know about surrounding cultures (such as the other Celtic tribes) to try filling in some of the gaps or backing up some of the texts.

More or less Irish Pagan beliefs are something of a jigsaw puzzle and we have to fit the pieces together and be aware that some peices may be missing altogether. It's deeply frustrating but also, I feel, really rewarding when you get deep into the weeds about aspects that you find particularly interesting

P.S. I don't think the Irish monks were necessarily TRYING to muddy the water, I think they were just doing their best to make the information make sense. Either make sense to the 'modern' audience and/or make sense in their world view. For instance the stories in the book of invasions are pretty well accepted as 'authentic' to the pagan view, but the monks obviously added the portions about some 'characters' being children/grandchildren of Noah and such because it validated the Irish peoples in the Christian story

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does anyone have that chronicle (?) where the medieval monk was being pretentious about Jews not utilizing bells the way the church did, and the rabbi/Jewish leader he's talking to makes a comparison with the noise of market and says a truly quality product doesn't have to advertise itself?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

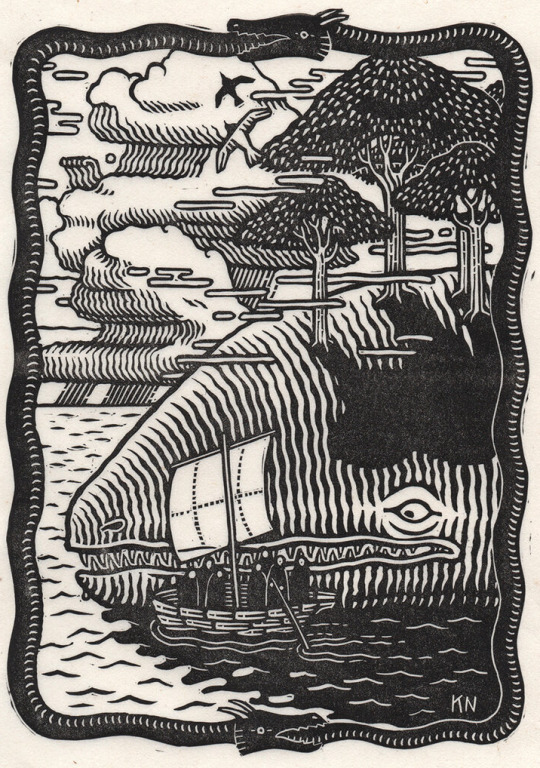

#unhallowedarts - Brendan's Uncanny Journey into the Unknown

‘O! tell me, father, for I loved you well, if still you have words for me, of things strange in the remembering in the long and lonely sea, of islands by deep spells beguiled where dwell the Elven-kind: in seven long years the road to Heaven or the Living Land did you find?’ (J.R.R. Tolkien, “The Death of St. Brendan”)

Kathleen Neely for A. B. Jackson's "The Voyage of St. Brendan" (2021)

It might be a bad case of “the grass is always greener on the other side” or just curiosity and a yearning to know what might be beyond the horizon of the broad Atlantic that washed upon their beaches, but it is the Gaels and the Britons, of all the Celtic people, the Insular Celts, who have the strongest tradition of tales about mythical islands and lost underwater kingdoms. Lyonesse west of the Scilly Islands in the Arthurian tradition, Ys off Brittany, the “Welsh Atlantis” of Cantre’r Gwaelod and the Irish legends of Tír Tairngire and Tír na nÓgm, whole Otherworlds and Happy Hunting Grounds out in the ocean and, of course, Hy-Brasil, an island cloaked in mist except for one day every seven years, that became the namesake of Brazil centuries later, to name but a few. A typical hero quest of Insular Celtic tradition was the voyage, by ship or magic horse, out there where adventure was awaiting and to return a better man or not at all. The motif of reaching the Great Beyond by ship was taken up by Irish monks in the early Middle Ages and transformed into Saints’ voyages to some Paradise or the other located west of Ireland, a type of tale called simply “immram”, voyage, and the most popular of the immrama is certainly that of St Brendan.

Whether or not the Blessed Brendan had founded Clonfert Cathedral in Galway in 563, usually named as the only historically secured feat of his vita, his tale, written down probably as late as the 10th century, became a long running hit in medieval literature with an impact history that lasted well into the Age of Exploration. The author or authors of Brendan’s travel story did, admittedly, their best to spin a whale of a tale that does not have to shun comparison with Coleridge’s “Ancient Mariner”. With elements of old legends, hell visions, probable early discoveries like the volcanoes of Iceland or places like the Faroe Islands, Greenland or Newfoundland, before Eric the Red and Leif Erikson followed the whale road across the Western Ocean around 1000 CE, the monks certainly held their audience in a thrall over the centuries. The most memorable event of Brendan’s maritime quest for the Garden of Eden certainly was the celebration of Easter Mass on an island that turned out to be the sleeping Jasconius, a giant, whale-like creature, awoken by the saint and his fellows when they lit a fire on the poor thing’s back. Nonetheless, St Brendan returned to tell the tale, became the patron saint of whales, founded various monasteries, finally died as an old man, allegedly, in 577 and was buried in Clonfert.

Brendan’s Island appeared on maps as late as the early 18th century, Henry the Navigator and Columbus believed in its existence, even though they placed it in west of Africa and not in the North Atlantic. Of course, Brendan joined the queue of pre-Columbian discoverers of America like the Welsh Prince Madoc or even pre-Viking explorers like Bran. In 1976, the British explorer, historian and author Tim Severin took the legends literally, build a currach, a type of Irish boat with a wooden frame over which ox hides are stretched as it was described in the old texts and used at least until the 17th century and set forth with a crew of three on an epic 4,500 mile voyage from the west of Ireland along the Hebrides and Iceland to Newfoundland, trying to prove that a voyage like St Brendan’s was at least possible in the early Middle Ages. The saint, in the meanwhile, is venerated as patron of sailors along with St Nick and various local heroes and, as of late, as the holy helper in cases where portable canoes are involved

All images above were created by Kathleen Neely A. B. Jackson's "The Voyage of St. Brendan" (2021) and found on the website below.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

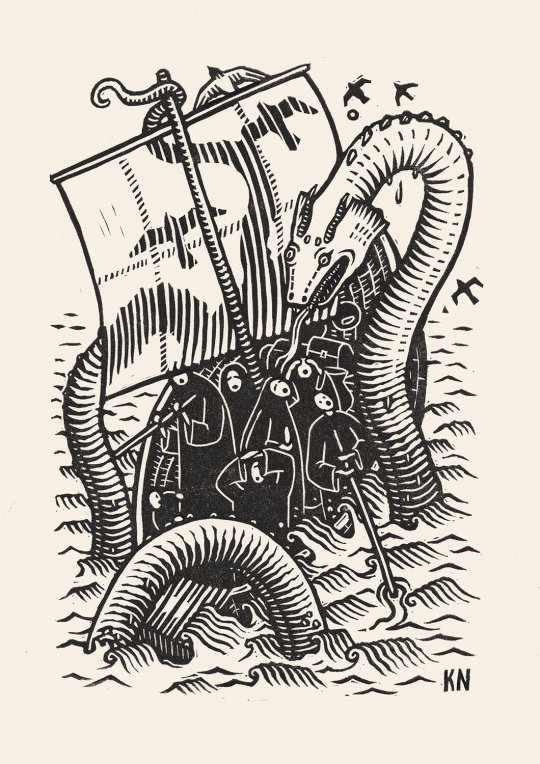

Thinking about Sea Monsters

I wonder if the decrease in incidence of “sea monsters” isn’t just due to the advancement of natural science and being able to identify them as normal animals, but also due to the decrease in sailing ships.

Think about it. Modern ships (even as far back as steam ships) make a lot of noise, there’s an engine or boiler running, there’s gears turning, a propeller churning. We know sea-noise is an actual ecological issue that messes with whales and dolphins, and many large cetaceans have scars from close brushes with propellers. Back in the age of sail, ships would have been so much quieter, only making the noise of their movement through the water and the people on board (at least from the perspective of something below the surface). Sailing ships also make more frequent stops and course-changes, being at the mercy of the wind and weather.

I can imagine all sorts of animals being curious about that huge dark shape near the surface, bigger than any whale or other predator they’ve ever seen, that’s just... sitting there. Or moving apace to the wind, which wouldn’t be too hard to keep up with. It’s not making much or any noise, it doesn’t move like a predator or a whale. Sometimes things fall in its wake that you can snack on, or follow to it, as it trails a weighted strand down into the depths.

Whales and dolphins would surely want to investigate this big neutral(?) entity (assuming of course it wasn’t a whaling ship they recognized, but I’m talking like earlier than the whaling boom) and see what it is. Seals as well. Even animals that don’t have a reputation for being terribly smart - squids, rays - would probably approach an anchored or slow-moving ship to see if it was something dead or dying they could take a bite out of.

And when I talk about “sea monsters” I mean the weird medieval ones like the “Bishop Fish” or “Sea Monk,” ones that at the time were believed to resemble human-like figures.

We can even see in this latter image the comparison being drawn to a misidentified squid. I also called out rays because other misidentified “sea monsters” are theorized to be a ray or an angel shark seen only from the underside.

Imagine being a sailor keeping watch while your ship is at anchor in shallow water. You hear a stirring at the side of the boat, maybe even a splash as if something has fallen back into the water. You go to take a look and find this grumpy face staring back up at you before it swims away!

In reality, you’ve just seen a 6-foot angel shark try and fail to get a mouthful of your boat’s encrusted barnacles. But you probably think you’ve just seen a pale man-sized thing glower up at you because you caught it trying to board your boat!

This isn’t a “ugh technology and science rob the magic from the world” kind of post. It’s just an idle musing about how our methods of functioning (even something as simple as traveling fast or while making a lot of noise) can change the way we perceive the world. How often do you hear birdsong? How often might you hear birdsong if there was no traffic noise?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

28.08.2024

Tuve junta con Sf y me dijo que voy muy bien. Pero también quedó claro que hay chingos de chamba que todavía falta y solo yo para hacerla. Abruma un poco.

Sigo emputado por lo de python.

//

Por otro lado me enteré que le pagan a gente por investigar textos antiguos de magia. Según perplexity:

Recent academic research has increasingly focused on the systematic analysis, classification, and contextualization of magical and occult texts throughout history. This research aims to explore how mystical and magical thought has evolved over time, as well as to classify the types of knowledge and beliefs associated with these texts.

Key Research Initiatives

MagEIA Project at the University of Würzburg

A significant initiative is the newly established research group at the University of Würzburg, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) with approximately 3.5 million euros. The project, titled "MagEIA - Magic between Entanglement, Interaction, and Analogy," focuses on magical texts from the Ancient Near East and Egypt. The researchers aim to analyze these texts to understand their role in the history of religion and ideas, examining cross-cultural correspondences and interactions among different magical traditions. This project emphasizes a multidisciplinary approach, combining philological studies with insights from cultural anthropology and archaeology, to develop new methods of textual analysis and models for cross-cultural comparison.

Historical Perspectives on Medieval Magic

Another relevant study is Sophie Page's Magic in the Cloister, which investigates the integration of magical texts within the monastic environment of medieval Europe. This work highlights how monks at St. Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury engaged with magical texts, viewing them as compatible with their religious beliefs. The book discusses various genres of magic present in medieval manuscripts and explores how these texts were adapted and interpreted in a religious context, thereby illustrating the evolving attitudes towards magic during this period.

Poetic Techniques in Ancient Incantations

Research on ancient magical texts, such as the Maqlû incantations, reveals the use of poetic devices and repetition as critical components of their structure. This analysis indicates that such techniques not only enhance the aesthetic appeal of the texts but also serve functional roles in rituals, contributing to their persuasive power and effectiveness in magical practices.

Conclusion

These research efforts collectively contribute to a deeper understanding of magical and occult texts, tracing their historical development and cultural significance. By examining these texts through various disciplinary lenses, scholars aim to uncover the complexities of magical thought and its transformations across different cultures and eras. This systematic analysis not only enriches our knowledge of historical beliefs and practices but also sheds light on the broader implications of magic in human society throughout history.

https://www.perplexity.ai/search/is-there-academic-research-tha-oIHYPh2NQNyHuJor2lPvFg#0

0 notes

Text

Whenever I'm looking at paleoart it's not hard to draw comparisons with illustrations of foreign animals in medieval manuscripts. Why does nobody know what to do with the stupid bony protrusions on deodon's and thylacosmilus' face for reconstructions. Why was the concept of a hippopotamus so difficult for medieval monks and scholars. Why do cotylorhynchus and erythrosuchus look so damn goofy

1 note

·

View note

Photo

What I would do with all the monk research if I wrote fiction...

I’d keep the choir master / choir boy dynamic. That is lit. I would shift it out of the old rag and bone warehouse on Elm Hill to Llanthony though because, well. Look at it. It’s walking distance to the picturesque ruins of the actual medieval priory. We could have some Hardy-esque bollocks about good clean country air and old stones and stuff. Contrasting the memory of grass and open spaces (pretend monk life) with the smog and crowding of the city (real life).

The monk would be that same kind of clueless upper middle class boy whose only previous experience of hard work has been fagging for a swell who loved nothing more than taking the piss out of their obvious infatuation with him. The kind of sad lonely type who only got affection from the staff, and that dried up when he got too old for that kind of familiarity to be acceptable.

Maybe some kind of earlier near death experience to help drive home their extreme religiosity and terror of damnation? Marking them out as different somehow within the family and social circle? Consumptive disease is the ideal, but I’ve always quite liked drowning in Victorian fiction. You get to play with that idea of the difference between the world below and above, and then repeat in the worlds of want and expectation.

So, yeah, a pasty introverted youth with ~delicate~ health and an obsession with serving God. (In a patriotically Anglican way, obviously.) Then the boy gets to be some slightly wild rustic. Like, they’ve never even experienced a properly starched Eton collar. Even if I pushed it into my beloved early Edwardian period, they probably still only had schooling up to the state mandated age of 12. Maybe their Welsh literacy is better than their English? Mamgu taught him everything he knows?

But they’d have learned stuff you can’t get from any amount of Latin grammar. There would be some faux fairytale / pagan revival style bullshit going on, about the old ways, and the love of God, and much fearful angsting that this angelic looking lad is temptation delivered by Satan himself. Because God can’t just love everyone? Without demanding constant penance and suffering? What even is this madness. Surely life can’t be that simple???

They need to double down on the self denial, and the fasting, and the helpless fainting during prayers or something.

And there would be a raging storm one day, for no particular reason. It would just look cool and somebody could be out catching their death of cold in it. Imagine: monk robes all sodden with mud and cold water, like drowning in the ornamental boating lake of their cousin’s estate one long ago morning.

And there would be some equally pointless scene at the ruins, playing hide and seek with local kids for some festivity or other. And they’d have to hunker out of sight in a darkened corner, chill enough that it raises goosebumps on the skin even though it’s the height of summer. Which would inevitably lead to the boy pressing a silencing finger to the monk’s lips in a symbolic not actual kiss that they’re gonna do all kinds of sinful things thinking about...

Eventually the monk would have to back to real life(tm) because no upstanding English family is going to let their kid prance about in this foreign regalia forever. They can get a curacy in a nice English village and marry a nice English girl and produce nice English children. It would seem so dull and grey and awful in comparison, like they’d been caught in a fairy trap and changed beyond belief while life at home went on as always, and they’d think about throwing reputation and respectability away to go be happy and live the kind of life they want.

But they wouldn’t, because that’s not how these things work. Instead WWI would steamroll along and they’d have to go do their patriotic duty. Be a good son, and a good brother, and then a good uncle, etc, etc, etc. Until they’re old, and need help to get around, and have pity visits from dutiful grand-nieces who take them on a drive out to the country to go see some pretty ruins from the ancient old days when there was no TV or miniskirts or portable transistor radios.

And there they’d meet some other young descendant who would conveniently have their own ties to the area and, I dunno, some memento from their dearly departed Tadgu that’s actually a pressed flower in glass commemorating a long ago summer day when two dumb idiots in love almost shared a not quite kiss...

Just, yeah. Self-denial and misery. But hope for the future that other people won’t have to.

0 notes

Photo

Parallels Between the Bene Gesserit & Medieval Monks & Friars:

The Bene Gesserit in David Lynch’s Dune mirror the monks and (especially) friars of medieval times. Unlike them though, they do not take vows of chastity or devote themselves to leave all material possessions behind. There are Bene Gesserit or lesser female acolytes who lead humble lives but aren’t required to leave all their material possessions behind. Like widows during medieval times, older and for the most part rich, women, decide to leave everything behind to live with the older Bene Gesserit sisters. This type of retirement offers a source of comfort to some and is a good way to show their devotion and gratitude to an order that is one of the most powerful and influential in the galaxy.

Lynch’s aesthetic choice could be owed due to the religious nature of this order. The Bene Gesserit use a hybrid form of religious text that combines all three monotheistic religious texts, in addition to other theological works, that is known as the “Orange Catholic Bible” (OCB). What better way to convey this than by showing them as nuns with tonsured styles once they become Reverend mothers?

The transition to becoming a Reverend mother is also depicted in Lynch’s film when Jessica and her son are still in hiding and Jessica -as in the book- is about to go through the “agony” that comes with drinking the “water of life.” Soon after, she shaves the crown of her head and in the next scene, we see her as a fully fledged Reverend mother with more solemn clothes that are similar to those of her superiors.

The first developments of these tests is heavily described in Dune extended universe which consists of mostly a series of prequel books penned by Frank Herbert’s son, Brian and a co-author, renowned science fiction novelists, Kevin J. Anderson. These books are based on unfinished manuscripts left behind by his father. One of these is “Sisterhood of Dune”. In the first chapters, there is a brief overview of the aftermath of the Butlerian Jihad, the beginning of schools for men and women whose graduates will come to replace the thinking machines that their ancestors once depended on. Among these schools is Rossak School headed by Raquella Berto-Anirul. Reverend Mother Raquella is dressed in plain black robes. She describes the “agony” and how, after countless trials, there hasn’t been one that’s ended in success. She can’t quite explain why. She and her mentor had been experimenting with many poisons until they discovered the amazing properties of spice melange and other deadly combinations which awakened a part of her mind that led her to become the first true Bene Gesserit.

“More than eight decades ago, the dying and bitter Sorceress Ticia Cenva had given Raquella a lethal dose of the most potent poison available. Raquella should have died, but deep in her mind, in her cells, she had manipulated her biochemistry, shifting the molecular structure of the poison itself. Miraculously she survived, but the ordeal had changed something in her biochemistry, shifting the molecular structure of the poison itself. Miraculously she survived, but the ordeal had changed something fundamental inside her, initiating a crisis-induced transformation at the farthest boundaries of her mortality. She had emerged whole but different, with a library of past lives in her mind and a new ability to see herself on a genetic level, possessing an intimate understanding of every interconnected fiber of her own body.” -Sisterhood of Dune

This type of adaptation leads her to commit desperate acts. Desperate times require desperate measures after all. It is vital that she succeeds, if she doesn’t then all the knowledge she has acquired will die with her. The Dune encyclopedia also goes into detail about the Bene Gesserit early beginnings and practices. Many of these do mirrors the tonsured monks which David Lynch and de Laurentis seem to have based their Bene Gesserit on. Medieval monks shaved the crown of their heads as a sign of devotion and signal to an ascetic life. Depending on the religious order, each friar had a different focus -something that can also be found in the Bene Gesserit. The books mention how the Bene Gesserit send missionaries to distant planets, one of them being Dune, to plant seeds of superstition in the populace that will aid with their scheme to create the first male Bene Gesserit, a perfect specimen known as the Kwisatz Haderach. It is for this reason that Paul Atreides was able to gain many followers when he and his mother narrowly escaped the clutches of Baron Harkonnen and his cronies.

The parallels between the Bene Gesserit and the medieval monks are restricted solely to their ideological devotion and theological drive to convert others through knowledge or with the aid of their powerful patrons, and to reach a higher understanding of the world around them.

The Bene Gesserit are eternally devoted to their order’s ideals and precepts in the same manner that the medieval monks are. BUT that is where the similarities end. The Bene Gesserit do not care for vows of chastity or poverty. Some women decide to join the sisters later in life as a form of penance or because it is a high honor, but that is it. Monks and friars on the other hand take vows of chastity, leading an ascetic way of life, helping their communities by giving aid to the poor and tending to the sick when needed.

There were exceptions to the rule, but generally, once a man entered a monastery, he would leave the material world behind. This was especially true of friars. Founded in the twelfth century, friars led a stricter way of life than all other religious orders. Unlike monks and like the Bene Gesserit, they weren’t confined to a single community. Friars got to move around a lot and as a result knew more about what ailed the general populace.

Going back to their physical appearance. Monks and Friars were not the first nor the last of religious orders to adopt this type of hairstyle. Celtic priests were known to shave part of their heads, so did some Eastern Christian religious orders also adopted this hairstyle. This tradition in Roman Catholic Church arises from the belief that the apostle Peter -hailed as the founder of the Roman Catholic Church- was the first to adopt this hairstyle to prove his devotion to his lord and savior, Jesus Christ.

Read more here: https://www.facebook.com/fictionhistorybyanothername/posts/1976523749082358?__xts__%5B0%5D=68.ARD4binHYZ-xVxu3rbS025Fbtr_47Vh8-ZOkL3OFTLeCYzQRNAHATime74RxLF0bh_GrhuwVbzlXEZq3GyMb_eGWLmsDndEFnhTmAYM2jXMKbnAmFQlfAn9oKOwWrxb7-ZeAzSC46m3Wu6e1FJ60qhH8j6gc6o_YeT5IbetupgH_zIOcZgb9fg3Njha2aGFddJEXPj-dr6nZELgbgUD7BIXQ0eEkgTAFWE4M6bfovqfj68DEZB9Rh5urNTAVU59dvMQNcU1uQ_UNwcRbkWnGxpMFUWF4WnHX9OTu4MMZdKl0yblhOfbO7UlCgkudxPbmy-3fnm-Avb8kK_JQtCQo50JhwA&__tn__=K-R

#bene gesserit#david lynch's dune 1984#comparison to medieval monks#tonsured heads#history#science fiction

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Another then vs now. Not sure when exactly I drew the older one, but I’m guessing 2009/2010. The newer one I drew yesterday (4.12.2020)

1 note

·

View note

Text

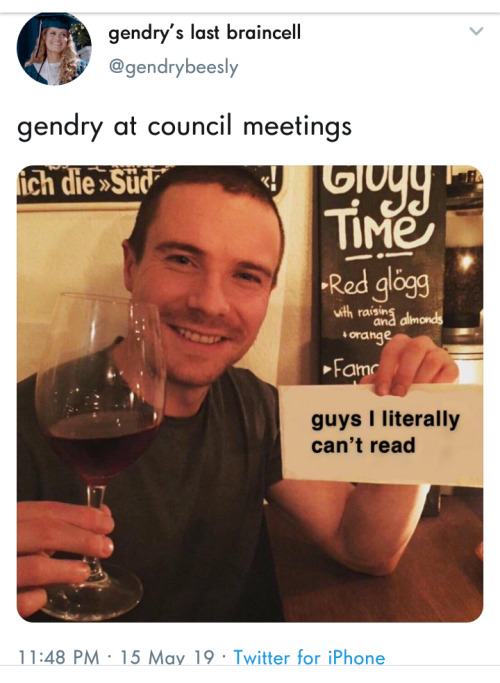

Is Gendry illiterate?

Short answer: Probably not.

Long answer:

I’ve noticed a lot of fanfiction trying to address Gendry’s illiteracy once he becomes a noble. Most fics depict him as being completely illiterate. Some depict him as having some level of literacy, but not enough for his new position. So let’s try to figure it out, shall we?

Part 1: Literacy

We have this assumption that in medieval times no one could read or write unless they were part of the nobility. That is not quite true. Firstly, we have to understand what it meant to be literate by medieval standards:

“In Medieval times, “Literate” actually meant able to read and write in Latin, which was considered to be the language of learning. Being able to read and write in the vernacular wasn’t considered real learning at all. Most peasants prior to the Black Death (which really shook up society) had little chance to learn - hard labouring work all of the hours of daylight does’t leave a lot of energy for reading or writing.

It’s worth noting, however the panic amongst the ruling classes when translations of The Bible started to appear written in English. This really started in the late 14th Century (about 30 years after the Black Death). The level of panic suggests that the Ruling Classes knew that the numbers of people who could read and write English was far greater than the numbers who could read Latin.”

However, there is no language quite like Latin in Westeros. The closest we come to something similar is High Valyrian. Which noble children seem to have a basic understanding of. We can safely assume that Gendry doesn’t have extensive knowledge of High Valyrian - so he is illiterate in that regard. But I don’t think High Valyrian is as widely used as Latin was in the Middle Ages. It’s also not a language with religious significance. As the Faith of the Seven doesn’t use High Valyrian the way that the Catholic Church used Latin.

So… taking that into account. What I assume that is meant by “literate” in Westeros is being able to read and write in the Common Tongue.

I will say that even by those parameters I don’t think most of the commoners would have been literate. However, Gendry was not in the same situation as most of the commoners.

Which leads me to...

Part 2: Socio-economic class in Medieval Times

The level of literacy among the commonfolk has to be examined on a case by case basis.

Literacy among “peasants” varied a lot depending on circumstance. So, for example, it’s not strange that Davos, who was a smuggler prior to meeting Stannis, was illiterate. Or Gilly, who was completely isolated from the world and in terrible conditions.

But Gendry is in a different situation.

As @arsenicandfinelace pointed out in this cool meta:

Gendry was definitely born low-class, as an unrecognised bastard whose mother was a tavern girl (read: one step away from prostitute). But the whole point of apprenticing with Tobho Mott is that that was a major leap forward for him, socially.

As Davos put it in 3x10, “The Street of Steel? You lived in the fancy part of town.” Yes, a tradesman of any kind is leagues below the nobility, and could never ever be worthy of marrying a highborn girl like Arya. But Tobho Mott is a master craftsman, the best armourer in the capital city of a heavily martial country. As far as tradesman go, he’s the best of the best, and charges accordingly.

There’s a reason Varys had to pay out the ass to get Gendry apprenticed there. If he had stayed, completed his apprenticeship, and eventually taken over the workshop, he would have been very wealthy (by commoner standards) and respectable (again, by commomner standards), despite his low birth.

Tobho Mott is a tradesman and a craftsman. He is part of the merchant class. * Merchants are often referred to as a different class from the rest of the population. The merchant class in Medieval Times was closer to the middle class of contemporary times.

“By the 15th century, merchants were the elite class of many towns and their guilds controlled the town government. Guilds were all-powerful and if a merchant was kicked out of one, he would likely not be able to earn a living again.”

Mott would be considered to be part of the merchant class - and not even a common kind of merchant either. He was the best Blacksmith in all of King's Landing, the capital of the Seven Kingdoms. So we can assume that Tobho Mott was a very wealthy and powerful craftsman and merchant.

“That many 'middle class' people (tradesmen, merchants and the like) could read and write in the late middle ages cannot be disputed.”

I’m not saying that all tradesmen/merchants/craftsmen were literate back then. It was still a smaller percentage than the nobility. Only the richer and more influential of tradesmen would learn Latin. But I think most of them would be literate enough in the vernacular to run a business. Considering Mott’s reputation and his clientele I’m certain that Mott is part of that literate percentage.

In season 2, Arya accidentally reveals to Tywin that she can read. Realizing her mistake she covers up by saying that her father, a ’stonemason', taught her. Of course, I don’t think that completely fooled Tywin but why did Arya say her father was Stonemason. Why did his profession matter at all? Surely it wouldn’t have mattered if he was a fisherman or a farmer... a peasant is a peasant, right?

Wrong.

“The Medieval Stonemason asserts that they were not monks but highly skilled craftsmen who combined the roles of architect, builder, craftsman, designer, and engineer. Many, if not all masons of the Middle Ages learnt their craft through an informal apprentice system”

“Children from merchants and craftsmen were able to study longer and continuous, so they were able to learn Latin at a later age. This way, everyone learned to read and write (some better than others) sufficiently for their trade.”

Stonemasons were the architects of the time and no doubt the top tier was literate.

Many trades (by the 15th C) required reading and writing, so it was taught to apprentices by the masters. We know from apprenticeship agreements that many masters were expected to continue the apprentice's literacy or start it, which makes sense for the wider viability of the trade.

The War of the Roses took place in the late 15th Century. So I’m guessing that that’s the time period that ASOIAF is mostly based on.

Part 3: Level of literacy

I think it’s safe to say that Gendry has some level of literacy. However, his “level” is pretty much up for debate. If he’d finished his apprenticeship it’s likely he’d have a decent level of reading/writing comprehension. However, near the end of his apprenticeship he was kicked out.

I’m not sure how much Gendry could read/write by the time that he was kicked out by Tobho Mott. But he’d already been his apprentice for 10 years (in show canon). More than enough time to get some basic reading/writing/basic math lessons.

It seems that show!Gendry is more likely to have a higher level of literacy than book!Gendry. In the show, he leaves Tobho Mott at 16, while in the book he is 14. This is just my own impression, but I think his education would be more complete by age 16 than age 14.

Not to mention that book!Gendry is still in the Riverlands and working for outlaws. But in the show we can assume that Gendry has been smithing in King’s Landing for years and it is insinuated that he owns a shop. Meaning he might have reached “Master” status and can take on apprentices of his own. It might seem like Gendry is too young for that. But it’s actually not that strange.

“Apprentices stayed with their masters for seven to nine years before they were able to claim journeyman status. Journeyman blacksmiths possessed the basic skills necessary to work alongside their master, seek work with other shops, or even open their own businesses.”

Considering that Gendry has been with Mott for 10 years in show!canon, it’s possible that Gendry was a “journeyman” and not an “apprentice” by the time that Ned meets him in season 1. But he might be nearing the end of his apprenticeship in the books.

Guilds also required journeymen to submit work for examination each year in each area of expertise. So, a journeyman who perhaps crafted swords, locks, and keys would need to submit each item to his guild annually for inspection. If the guild approved the craftsmanship of the products, the journeyman could eventually move up to master status.

The process of becoming a master could take from 2 to 5 years. Considering that Gendry is regarded as talented, it’s likely that he achieved this in a shorter period of time. As a journeyman he also needed to work alongside a master for 3 to 4 years before he could obtain master status. Which would still explain why he was so upset at being kicked out by Mott - it’s like someone getting kicked out while they’re trying to obtain a PHD.

By the time we meet him in season 7 it’s very possible that Gendry is now considered a master of his trade.

He also seems to be making armour and weapons for “Lannisters” which means he has a mostly noble clientele. He probably has plenty of fancy clients asking for custom-made products. With sketches and measurements and all that shit. Which is not surprising since he probably has a de facto reputation simply by merit of being Tobho Mott’s apprentice (lets ignore how dumb it is that no one discovered that Gendry was in King’s Landing since he made no effort to hide who he was or try to hide from the nobility lol).

Conclusion:

It’s safe to say that Gendry had some access to higher education. He can probably read and write enough for his line of work. It’s likely that his level would still leave much to be desired once he became a noble though. For comparison, imagine if someone left school at age 11 and was then required to write a college-level thesis. So he’d definitely need some “lordly” writing lessons and further education.

Gendry is still wildly uneducated for what he needs to do. So...

This meme is still gold 10/10

* Correction: Though Mott would be considered part of the same socio-economic class as merchants he is primarily a tradesman/craftsman, and would be referred to as such. Since merchants didn’t produce the goods they sold. However they could belong to the same guild, along with artisans and craftsmen.

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

UPG-ish/doxa: I think general thievery falls under An Morrígan's jurisdiction because She steals cattle (measurement of wealth in prehistoric to medieval Ireland) for funsies. If it's at all viable or useful to compare Her to any Greco-Roman Theoi (whose myths Irish monks would absolutely have had access to, given their Latin tutelage) then She's got some qualities that perhaps would be considered "Mercurial," though this is not a 1:1 comparison due to the geographic expanse between the two regions. However, trade with Roman Britain prior to Christian conversion definitely had a sizable impact on Ireland's east coast religious traditions, too. Also, corvids are just Like That.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“These cultural understandings of male and female reproductive “nature” become more complex when different religious beliefs emphasize different aspects of them. Such is the case with Jewish and Christian attitudes toward reproduction. The disparity between Jewish and Christian attitudes is well known and has been the root of many debates over the centuries. While Jews saw the commandment to procreate—“pru urvu” (be fertile and increase) (Gen. 1:28)—as an important foundation of Jewish belief, Christians did not. Many scholars have referred to this distinction as limiting the possibilities for comparison between Jewish and Christian family life, and as justification for studying each society separately.

Even scholars who have examined Jewish and Christian family institutions in tandem have emphasized the theological gap that exists in this context. The Christian preference for celibacy was central from its beginnings. Indeed, most of the extant medieval records dealing with attitudes toward procreation were written by the same small and select group that chose celibacy as its way of life. Men who lived in monastic frameworks understood their choice as an expression of their ability to refrain from worldly pleasures and remain pure. Women who chose to be nuns viewed their celibacy, especially if they were virgins, as a ticket to the male spiritual environment and an escape from their fate as women.

Yet despite the many references to these men and women in medieval literature, we must remember that this was not the majority choice. Most Christians throughout the ages were married, not celibate. Because they esteemed the ideal of celibacy, Christian society treated married life as the less ideal choice. Nevertheless, in their discussions of noncelibate married women, the medieval authors resembled their Jewish peers. The cultural significance of women as childbearers is also evident in these authors’ descriptions of women who forewent motherhood to become brides of Christ. As a number of scholars, especially Caroline Bynum, have shown, images of birth and of maternity are prominent in descriptions of all women, including those who do not actually give birth. Jews, as is well known, did not share this attitude toward celibacy.

While only few Christians actually chose the monastic way of life, all saw this as an ideal, albeit one that posed too big a challenge for most. In contrast, all Jews saw procreation as an obligatory and positive commandment. Jewish and Christian attitudes toward the biblical commandment of procreation from antiquity through the Middle Ages have been examined in a recent study by Jeremy Cohen. Cohen examined Jewish and Christian attitudes toward the biblical command. His study altered the prevailing tendency to present Jewish and Christian attitudes as completely distinct. Cohen emphasized that in spite of their fundamental difference, there were also areas of similarity.

For example, Cohen maintained that despite the ideal of celibacy, some Christian scholars included procreation as part of the ius naturalis (natural order). In other words, procreation was not simply a commandment to be interpreted allegorically, but one that had practical implications. Thus, Cohen demonstrates that among the eastern Church Fathers, procreation within a family framework was understood as a positive commandment. Procreation was often reassessed and discussed in Western Christian thought throughout the Middle Ages. While some claimed that procreation was a biblical commandment no longer relevant to Christian lives, other interpreters began to attribute more importance to the commandment to procreate within the marital framework.

For example, in some cases, the biblical commandment was recited at the wedding ceremony. Thus, it became an important part of the blessing for a newlywed couple. This change in the ceremony was part of a major shift in Christian understandings of marriage that, in the twelfth century, made marriage one of the sacraments. At the same time, fertility became a far more important part of the church’s understandings of marriage. This change brought Jewish and Christian understandings of procreation somewhat closer. Studies concentrating on Christian society have emphasized the growing importance of marriage and family in medieval Christian theology and explained the changing significance accorded the family as a consequence.