#counterproof

Text

#16.05.22#2990#i have a counterproof to this theory i've been drinking so many energydrinks lately and i've never been less social#also i specifically drew the papillon flavor in there bc i think it was specifically the one i had that day#but bweh not a fan of that one#also funfact the papillon favor is called 'Monarch' in france

568 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter XI. Eighth Epoch. — The Property.

3. — How property depraves itself

By means of property, society has realised a thought that is useful, laudable, and even inevitable: I am going to prove that by obeying an invincible necessity, it has cast itself into an impossible hypothesis. I believe that I have not forgotten or diminished any of the motives which have presided over the establishment of property; I even dare say that I have given these motives a unity and an obviousness unknown until this moment. Let the reader fill in, moreover, what I may have accidentally omitted: I accept in advance all his reasons, and propose nothing to contradict him. But let him then tell me, with hand on conscience, what he finds to reply to the counterproof that I am going to make.

Doubtless the collective reason, obeying the order of destiny that prescribed it, by a series of providential institutions, to consolidate monopoly, has done its duty: its conduct is irreproachable, and I do not blame it. It is the triumph of humanity to know how to recognise what is inevitable, as the greatest effort of its virtue is to know how to submit to it. If then the collective reason, in instituting property, has followed its orders, it has earned no blame: its responsibility is covered. But that property, which society, forced and constrained, if I thus do dare to say, has unearthed, who guarantees that it will last? Not society, which has conceived it from on high, and has not been able to add to it, subtract from it, or modify it in any way. In conferring property on man, it has left to it its qualities and its defects; it has taken no precaution against its constitutive vices, or against the superior forces which could destroy it. If property in itself is corruptible, society knows nothing of it, and can do nothing about it. If property is exposed to the attacks of a more powerful principle, society can do nothing more. How, indeed, will society cure the vice proper to property, since property is the daughter of destiny? And how will it protect it against a higher idea, when it only subsists by means of property, and conceives of nothing above property?

Here then is the proprietary theory.

Property is of necessity providential; the collective reason has received it from God and given it to man. But if not property is corruptible by nature, or assailable by force majeure, society is irresponsible; and whoever, armed with that force, will present themselves to combat property, society owes them submission and obeisance.

Thus it is a question of knowing, first, if property is in itself a corruptible thing, which gives rise to destruction; in second place, if there exists somewhere, in the economic arsenal, an instrument which can defeat it.

I will treat the first question in this section; we will seek later to discover what the enemy is which threatens to devour property.

Property is the right to use and abuse, in a word, DESPOTISM. Not that the despot is presumed ever to have the intention of destroying the thing: that is not what must be understood by the right to use and abuse. Destruction for its own sake is not assumed on the part of the proprietor; one always supposes some use that he will make of his goods, and that there is for him a motive of suitability and utility. By abuse, the legislator has meant that the proprietor has the right to be mistaken in the use of his goods, without ever being subject to investigation for that poor use, without being responsible to anyone for his error. The proprietor is always supposed to act in his own best interest; and it is in order to allow him more liberty in the pursuit of that interest, that society has conferred on him the right of use and abuse of his monopoly. Up to this point, then, the domain of property is irreprehensible.

But let us recall that this domain has not been conceded solely in respect for the individual: there exist, in the account of the motives for the concession, some entirely social considerations; the contract is synallagmatic between society and man. That is so true, so admitted even by the proprietors, that every time someone comes to attack their privilege, it is in the name, and only in the name, of society that they defend it.

Now, does proprietary despotism give satisfaction to society? For if it were otherwise, reciprocity being illusory, the pact would be null, and sooner or later either property or society will perish. I reiterate then my question. Does proprietary despotism fulfil its obligation toward society? Is proprietary despotism a prudent administrator? Is it, in its essence, just, social, humane? There is the question.

And this is what I respond without fear of refutation:

If it is indubitable, from the point of view of individual liberty, that the concession of property had been necessary; from the juridical point of view, the concession of property is radically null, because it implies on the part of the concessionaire certain obligations that it is optional for him to fulfil or not fulfil. Now, by virtue of the principle that every convention founded on the accomplishment of a non-obligatory condition does not compel, the tacit contract of property, passed between the privileged and the State, to the ends that we have previously established, is clearly illusory; it is annulled by the non-reciprocity, by the injury of one of the parties. And as, with regard to property, the accomplishment of the obligation cannot be due unless the concession itself is by that alone revoked, it follows that there is a contradiction in the definition and incoherence in the pact. Let the contracting parties, after that, persist in maintaining their treaty, the force of things is charged with proving to them that they do useless work: despite the fact that they have it, the inevitability of their antagonism restores discord between them.

All the economists indicate the disadvantages for agricultural production of the parcelling of the territory. In agreement on this with the socialists, they would see with joy a joint exploitation which, operating on a large scale, applying the powerful processes of the art and making important economies on the material, would double, perhaps quadruple product. But the proprietor says, Veto, I do not want it. And as he is within his rights, as no one in the world knows the means of changing these rights other than by expropriation, and since expropriation is nothingness, the legislator, the economist and the proletarian recoil in fright before the unknown, and content themselves to expect nowhere near the harvests promised. The proprietor is, by character, envious of the public good: he could purge himself of this vice only by losing property.

Thus, property becomes an obstacle to labour and wealth, an obstacle to the social economy: these days, there is hardly anyone but the economists and the men of law that this astonishes. I seek a way to make it enter into their minds all at once, without commentary...

[…]

Let us suppose that the proprietor, by a chivalrous liberality, yields to the invitation of science, allows labour to improve and multiply its products. An immense good will result for the day-workers and peasants, whose fatigues, reduced by half, will still find themselves, by the lowering of the price of goods, paid double.

But the proprietor: I would be pretty silly, he says, to abandon a profit so clear! Instead of a hundred days of labour, I would not have to pay more than fifty: it is not the proletarian who would profit, but me. — But then, observe, the proletarian will be still more miserable than before, since he will be idle once more. — That does not matter to me, replies the proprietor. I exercise my right. Let the others buy well, if they can, or let them go to other parts to seek their fortune, there are thousands and millions!

Every proprietor nourishes, in his heart of hearts, this homicidal thought. And as by competition, monopoly and credit, the invasion always grows, the workers find themselves incessantly eliminated from the soil: property is the depopulation of the earth.

Thus then the revenue of the proprietor, combined with the progress of industry, changes into an abyss the pit dug beneath the feet of the worker by monopoly; the evil is aggravated by privilege. The revenue of the proprietor is no longer the patrimony of the poor, — I mean that portion of the agricultural product which remains after the costs of farming have been paid off, and which must always serve as a new material for the use of labour, according to that fine theory which shows us accumulated capital as a land unceasingly offered to production, and which, the more one works it, the more it seems to extend. The revenue has become for the proprietor the token of his lechery, the instrument of his solitary pleasures. And note that the proprietor who abuses, guilty before charity and morality, remains blameless before the law, unassailable in political economy. To eat up his income! What could be more beautiful, more noble, more legitimate? In the opinion of the common people as in that of the great, unproductive consumption is the virtue par excellence of the proprietor. Every trouble in society comes from this indelible selfishness.

In order to facilitate the exploitation of the soil, and put the different localities in relation, a route, a canal is necessary. Already the plan is made; one will sacrifice an edge on that side, a strip on the other; some hectares of poor terrain, and the way is open. But the proprietor cries out with his booming voice: I do not want it! And before this formidable veto, the would-be lender dares not go through with it. Still, in the end, the State has dared to reply: I want it! But what hesitations, what frights, what trouble, before taking that heroic resolution! What trade-offs! What trials! The people have paid dearly for this act of authority, by which the promoters were still more stunned than the proprietors. For it came to establish a precedent the consequences of which appeared incalculable!... One promised themselves that after having passed this Rubicon, the bridges were broken, and they would stay that way. To do violence to property, what could this portend! The shadow of Spartacus would have appeared less terrible.

In the depths of a naturally poor soil, chance, and then science, born of chance, discovers some treasure troves of fuel. It is a free gift of nature, deposited under the soil of the common habitation, of which each has a right to claim his share. But the proprietor arrives, the proprietor to whom the concession of the soil has been made solely with a view to cultivation. You shall not pass, he says; you will not violate my property! At this unexpected summons, great debate arises among the learned. Some say that the mine is not the same thing as the arable land, and must belong to the State; others maintain that the proprietor owns the property above and below, cujus est soluw, ejus est usque ad inferos. For if the proprietor, a new Cerberus posted as the guard of dark kingdoms, can put a ban on entry, the right of the State is only a fiction. It would be necessary to return to expropriation, and where would that lead? The State gives in: “Let us affirm it boldly,” it says through the mouth of M. Dunoyer, supported by M. Troplong; “it is no more just and reasonable to say that the mines are the property of the nation, than it once was to claim that it was the property of the king. The mines are essentially part of the soil. It is with a perfect good sense that the common law has said that the property in what is above implies property in what is below. Where, indeed, would we make the separation?”

M. Dunoyer is troubled by very little. Who hesitates to separate the mine from the surface, just as we sometimes separate, in a succession, the ground floor from the first floor? That is what is done very well by the proprietors of the coal-mining fields in the department of the Loire, where the property in the depths has been nearly everywhere separated from the surface property, and transformed into a sort of circulating value like the actions of an public limited company. Who still hesitates to regard the mine as a new land for which one needs a way of clearing?... But what! Napoléon, the inventor of the juste-milieu, the prince of the Doctrinaires, had wanted it otherwise; the counsel of State, M. Troplong and M. Dunoyer applaud: there is nothing more to consider. A transaction has taken place under who-knows-what insignificant reservations; the proprietors have been rewarded by the imperial munificence: how have they acknowledged that favour?

I have already had more than one occasion to speak of the coalition of the mines of the Loire. I return to it for the last time. In that department, the richest in the kingdom in coal deposits, the exploitation was first conducted in the most expensive and most absurd manner. The interest of the mines, that of the consumers and of the proprietors, demanded that the extraction was made jointly: We do not want it, the proprietors have repeated for who knows how many years, and they have engaged in a horrible competition, of which the devastation of the mines has paid the first costs. Were they within their rights? So much so, that one will see the State finding it bad that they left there.

Finally the proprietors, at least the majority, managed to get along: they associated. Doubtless they have given in to reason, to motives of conservation, of good order, of general as much as private interest. From then on, the consumers would have fuel at a good price, the miners a regular labour and guaranteed wages. What thunder of acclamations in the public! What praise in the academies! What decorations for that fine devotion! We will not inquire whether the gathering is consistent with the text and to the spirit of the law, which forbids the joining of the concessions; we will only see the advantage of the union, and we will have proven that the legislator has neither wanted, nor been able to want, anything but the well-being of the people: Salus populi suprema lex esta.

Deception! First, it is not reason that the proprietors followed in coming together: they submitted only to force. To the extent that competition ruins them, they range themselves on the side of the victor, and accelerate by their growing mass the rout of the dissidents. Then, the association constitutes itself in a collective monopoly: the price of the merchandise increases, so much for consumption; wages are reduced, so much for labour. Then, the public complains; the legislature thinks of intervening; the heavens threaten with a bolt of lightning; the prosecution invokes article 419 of the Penal Code which forbids coalitions, but which permits every monopolist to combine, and stipulates no measure for the price of the merchandise; the administration appeals to the law of 1810 which, wishing to encourage exploitation, while dividing the concessions, is rather more favourable than opposed to unity; and the advocates prove by dissertations, writs and arguments, these that the coalition is within its rights, those that it is not. Meanwhile the consumer says: Is it just that I pay the costs of speculation [agiotage] and of competition? Is it just that what has been given for nothing to the proprietor in my greatest interest comes back to me at such an expense? Let one establish a tariff! We do not want it, respond the proprietors. And I defy the State to defeat their resistance other than by an act of authority, which resolves nothing; or else by an indemnity, which is to abandon all.

Property is unsocial, not only in possession, but also in production. Absolute mistress of the instruments of labour, she renders only imperfect, fraudulent, detestable products. The consumer is no longer served, he is robbed of his money. — Shouldn’t you have known, one said to the rural proprietor, to wait some days to gather these fruits, to reap this wheat, dry this hay; do not put water in this milk, rinse your barrels, care more for your harvests, bite off less and do better. You are overloaded: put back a part of your inheritance. — A fool! responds the proprietor with a mocking air. Twenty badly worked acres always render more than ten which take us so much time, and will double the costs. With your system, the earth will feed more men: but what is it to me if there are more men? It is a question of my profit. As to the quality of my products, they will always be good enough for those who lack. You believe yourself skilled, my dear counsellor, and you are only a child. What’s the use of being a proprietor, if one only sells what is worth carrying to market, and at a just price, at that?... I do not want it.

Well, you say, let the police do their duty!... The police! You forget that its action only begins when the evil has already been done. The police, instead of watching over production, inspects the product: after having allowed the proprietor to cultivate, harvest, manufacture without conscience, it appears to lay hands on the green fruit, spill the terrines of watered milk, the casks of adulterated beer and wine, to throw the prohibited meats into the road: all to the applause of the economists and the populace, who want property to be respected, but will not put up with trade being free. Heh! Barbarians! It is the poverty of the consumer which provokes the flow of these impurities. Why, if you cannot stop the proprietor from acting badly, do you stop the poor from living badly? Isn’t it better if they have colic than if they die of hunger?

Say to that industrialist that it is a cowardly, immoral thing, to speculate on the distress of the poor, on the inexperience of children and of young girls: he simply will not understand you. Prove to him that by a reckless overproduction, by badly calculated enterprises, he compromises, along with his own fortune, the existence of his workers; that if his interests are not touched, those of so many families, grouped around him, merit consideration; that by the arbitrariness of his favours he creates around him discouragement, servility, hatred. The proprietor takes offence: Am I not the master? says he in parody of the legend; and because I am good to a few, do you claim to make of my kindness a right for all? Must I render account to those who should obey me? That home is mine; what I should do regarding the direction of my affairs, I alone am the judge of it. Are my workers my slaves? If my conditions offend them, and they find better, let them go! I will be the first to compliment them. Very excellent philanthropists, who then prevents you from labouring in the workshops? Act, give the example; instead of that delightful life that you lead by preaching virtue, set up a factory, put yourself to work. Let us see finally through you association on the earth! As for me, I reject with all my strength such a servitude. Associates! Rather bankruptcy, rather death!

[…]

A poor worker having his wife in childbirth, the midwife, in despair, must ask assistance of a physician. — I must have 200 francs, says the doctor, I won’t budge. — My God! replies the worker, my household is not worth 200 francs; it will be necessary that my wife die, or else we will all go naked, the child, her and me!

That obstetrician, let God rejoice! was yet a worthy man, benevolent, melancholic and mild, member of several scientific and charitable societies: on his mantle, a bronze of Hippocrates, refusing the presents of Artaxerxes.[7] He was incapable of saddening a child, and would have sacrificed himself for his cat. His refusal did not come from hardness; that was tactical. For a physician who understands business, devotion has only a season: the clientele acquired, the reputation once made, he reserves himself for the wealthy, and, save for ceremonial occasions, he rejects the indiscreet. Where would we be, if it were necessary to heal the sick indiscriminately? Talent and reputation are precious properties, that one must make the most of, not squander.

The trait that I have just cited is one of the most benign; what horrors, if I should penetrate to the bottom of this medical matter! Let no one tell me that these are exceptions: I except everyone. I criticise property, not men. Property, in Vincent de Paul[39] as in Harpagon[40], is always monstrous; and until the service of medicine is organised, it will be for the physician as for the scientist, for the advocate as for the artist: he will be a being degraded by his own title, by the title of proprietor.

This is what this judge did not understand, too good a man for his time, who, yielding to the indignation of his conscience, decided one day to express public criticism of the corporation of lawyers. It was something immoral, according to him, scandalous, that the ease with which these gentlemen welcome all sorts of causes. If this blame, starting so high, had been supported and commented on by the press, it was made perhaps for the legal profession. But the honourable company could not perish by the censure, any more than property can die from a diatribe, any more than the press can die of its own venom. Besides, isn't the judiciary interdependent with the corporation of lawyers? Isn’t the one, like the other, established by and for property? What would Perrin Dandin[41] become, if he were forbidden to judge? And what would we argue about, without property? The order of lawyers therefore rises; journalism, the chicanery of the pen, came to the rescue of the chicanery of words: the riot went rumbling and swelling until that imprudent magistrate, involuntary organ of the public conscience, had made an apology to sophistry, and retracted the truth that had arisen spontaneously through him.

[…]

Thus property becomes more antisocial to the extent that it is distributed on a greater number of heads. What seems necessary to soften, and to humanise property, collective privilege, is precisely what shows property in its hideousness: property divided, impersonal property, is the worst of properties. Who does not realise today that France is covered with great companies, more formidable, more eager for booty, than the famous bands with which the brave du Guesclin[42] delivered France!...

Be careful not to take community of property for association. The individual proprietor can still show himself accessible to mercy, justice, and shame; the proprietor-corporation is heartless, without remorse. It is a fantastic, inflexible being, freed from every passion and all love, which moves in the circle of its ideas as the millstone in its revolutions crushes grain. It is not by becoming common that property can become social: one does not relieve rabies by biting everyone. Property will end by the transformation of its principle, not by an indefinite co-participation. And that is why democracy, or system of universal property, that some men, as hard-nosed as they are blind, insist on preaching to the people, is powerless to create society.

[…]

Work, the economists repeat ceaselessly to the people; work, save, capitalise, become proprietors in your turn. As they said: Workers, you are the recruits of property. Each of you carries in your own sack[43] the rod that serves to correct you, and that may one day serve you to correct others.[44] Raise yourself up to property by labour; and when you have the taste for human flesh, you will no longer want any other meat, and you will make up for your long abstinences.

To fall from the proletariat into property! From slavery into tyranny, which is to say, following Plato, always into slavery! What a perspective! And though it is inevitable, the condition of the slave is no more tenable. In order to advance, to free yourself from wage-labour, it is necessary to become a capitalist, to become a tyrant! It is necessary; do you understand, proletarians? Property is not a matter of choice for humanity, it is the absolute order of destiny. You will only be free after you have redeemed yourself, by subjugation to your masters, from the servitude that they have pressed upon you.[45]

One beautiful Sunday in summer, the people of the great cities leave their sombre and damp residences, and go to seek the vigorous and pure air of the country. But what has happened! There is no more countryside! The land, divided in a thousand closed cells, traversed by long galleries, the land is no longer found; the sight of the fields exists for the people of the towns only in the theatre and the museum: the birds alone contemplate the real landscape from high in the air. The proprietor, who pays very dearly for a lodge on this hacked-up earth, enjoys, selfish and solitary, some strip of turf that he calls his country: except for this corner, he is exiled from the soil like the poor. Some people can boast of never having seen the land of their birth! It is necessary to go far, into the wilderness, in order to find again that poor nature, that we violate in a brutal manner, instead of enjoying, as chaste spouses, its heavenly embraces.

Thus, property, which should make us free, makes us prisoners. What am I saying? It degrades us, by making us servants and tyrants to one another.

Do you know what it is to be a wage-worker? To work under a master, watchful [jaloux] of his prejudices even more than of his orders; whose dignity consists above all in demanding, sic volo, sic jubeo[46], and never explaining; often you have a low opinion of him, and you mock him! Not to have any thought of your own, to study without ceasing the thought of others, to know no stimulus except your daily bread, and the fear of losing your job!

The wage-worker is a man to whom the proprietor who hires his services gives this speech: What you have to do does not concern you at all: you do not control it, you do not answer for it. Every observation is forbidden to you; there is no profit for you to hope for except from your wage, no risk to run, no blame to fear.

Thus one says to the journalist: Lend us your columns, and even, if that suits you, your administration. Here is what you have to say, and here is what you have to do. Whatever you think of our ideas, of our ends and of our means, always defend our party, emphasise our opinions. That cannot compromise you, and must not disturb you: the character of the journalist, it is anonymous. Here is, for your fee, ten thousand francs and a hundred subscriptions. What are you going to do? And the journalist, like the Jesuit, responds by sighing: I must live!

One says to the lawyer: This matter presents some pros and cons; there is a party whose luck I have decided to try, and for this I have need of a man of your profession. If it is not you, it will be your colleague, your rival; and there are a thousand crowns for the lawyer if I win my case, and five hundred francs if I lose it. And the lawyer bows with respect, saying to his conscience, which murmurs: I must live!

One says to the priest: Here is some money for three hundred masses. You don’t have to worry yourself about the morality of the deceased: it is probable that he will never see God, being dead in hypocrisy, his hands full of the goods of other, and laden with the curses of the people. These are not your affairs: we pay, fire away! And the priest, raising his eyes to heaven, says: Amen, I must live.

One says to the purveyor of arms: We need thirty thousand rifles, ten thousand swords, a thousand quintals of shot, and a hundred barrels of powder. What we can do with it is not your concern; it is possible that all will pass to the enemy: but there will be two thousand francs of profit. That’s good, responds the purveyor: each to his craft, everyone must live!... Make the tour of society; and after having noticed the universal absolutism, you will have recognised the universal indignity. What immorality in this system of servility [valetage]! What stigma in this mechanisation!

[…]

Abuse! Cry the jurists, perversity of man. It is not property that makes us envious and greedy, which makes our passions spring up, and arms with its sophisms our bad faith. It is our passions, our vices, on the contrary, which sully and corrupt property.

I would like it as well if one says to me that it is not concubinage that sullies man, but that it is man who, by his passions and vices, sullies and corrupts concubinage. But, doctors, the facts that I denounce, are they, or are they not, of the essence of property? Are they not, from the legal point of view, irreprehensible, placed in the shelter of every judiciary action? Can I remand to the judge, summon to appear before the tribunals this journalist who prostitutes his pen for money? That lawyer, that priest, who sells to iniquity, one his speech, the other his prayers? This doctor who allows the poor man to perish, if he does not submit in advance the fee demanded? This old satyr who deprives his children for a courtesan? Can I prevent a licitation[47] that will abolish the memory of my forefathers, and render their posterity without ancestors, as if it were of incestuous or adulterous stock? Can I restrain the proprietor, without compensating him beyond what he possesses, that is without wrecking society, for heeding the needs of society?...

Property, you say, is innocent of the crime of the proprietor; property is good and useful in itself: it is our passions and our vices which deprave it.

Thus, in order to save property, you distinguish it from morals! Why not distinguish it right away from society? That was precisely the reasoning of the economists. Political economy, said M. Rossi, is in itself good and useful; but it is not moral: it proceeds, setting aside all morality; it is for us not to abuse its theories, to profit from its teachings, according to the higher laws of morality. As if he said: Political economy, the economy of society is not society; the economy of society proceeds without regard to any society; it is up to us not to abuse its theories, to profit from its teachings, according to the higher laws of society! What chaos!

I not only maintain with the economists that property is neither morals nor society; but more that it is by its principle directly contrary to morals and to society, just as political economy is anti-social, because its theories are diametrically opposed to the social interest.

According to the definition, property is the right of use and abuse, which is to say the absolute, irresponsible domain, of man over his person and his goods. If property ceased to be the right of abuse, it would cease to be property. I have taken my examples from the category of abusive acts permitted to the proprietor: what happens here that is not of an unimpeachable legality and propriety? Hasn’t the proprietor the right to give his goods to whomever seems good to him, to leave his neighbour to burn without crying fire, to oppose himself to the public good, to squander his patrimony, to exploit and fleece the worker, to produce badly and sell badly? Can the proprietor be judicially constrained to use his property well? Can he be disturbed in the abuse? What am I saying? Isn’t property, precisely because it is abusive, that which is most sacred for the legislator? Can one conceive of a property for which police would determine the use, and suppress the abuse? And is it not evident, finally, that if one wanted to introduce justice into property, one would destroy property; as the law, by introducing honesty into concubinage, has destroyed concubinage?

Thus, property, in principle and in essence, is immoral: that proposition is soon reached by critique. Consequently the Code, which, in determining the right of the proprietor, has not reserved those of morals, is a code of immorality; jurisprudence, that alleged science of right, which is nothing other than the collection of the proprietary rubrics, is immoral, and justice, is instituted in order protect the free and peaceful abuse of property; justice, which orders us to come to the aid against those who would oppose themselves to that abuse; which afflicts and marks with infamy whoever is so daring as to claim to mend the outrages of property, justice is infamous. If a son, supplanted in the paternal affection by an unworthy mistress, should destroy the document which disinherits and dishonours him, he would answer in front of justice. Accused, convicted, condemned, he would go to the penal colony to make honourable amends to property, while the prostitute will be sent off in possession. Where then is the immorality here? Where is the infamy? Is it not on the side of justice? Let us continue to unwind this chain, and we will soon know the whole truth that we seek. Not only is justice, instituted to protect property, itself abusive, itself immoral, infamous; but the penal sanction is infamous, the police are infamous, the executioner and the gallows, infamous, and property, which embraces that whole series, property, from which this odious lineage come, property is infamous.

Judges armed to defend it, magistrates whose zeal is a permanent threat to those accused by it, I question you. What have you seen in property which has been able in this way to subjugate your conscience and corrupt your judgement? What principle, superior without doubt to property, more worthy of your respect than property, makes it so precious to you? When its works declare it infamous, how do you proclaim it holy and sacred? What consideration, what prejudice affects you?

Is it the majestic order of human societies, that you do not understand, but of which you suppose that property is the unshakeable foundation? — No, since property, as it is, is for you order itself; since first it is proven that property is by nature abusive, that is to say disorderly and anti-social.

Is it Necessity or Providence, the laws of which we do not understand, but the designs of which we adore? — No, since, according to the analysis, property being contradictory and corruptible, it is for that very reason a negation of Necessity, an injury to Providence.

Is it a superior philosophy considering human miseries from on high, and seeking by evil to obtain the good? — No, since philosophy is the agreement of reason and experience, and in the judgement of reason as in that of experience, property is condemned.

[...]

#organization#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#the system of economic contradictions#the philosophy of poverty#volume i#pierre-joseph proudhon#pierre joseph proudhon

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy #WorldChocolateDay 🍫!

Maria Sibylla Merian (Germany 1647 - Dutch Republic 1717)

Cocoa Tree with Southern Armyworm Moth, 1702-03

Watercolour & bodycolour w/ gum arabic over etched lines on vellum, 37.7 x 28.4 cm

Royal Collection Trust RCIN 921183

“A watercolour of a branch of a Cocoa Tree (Theobroma cacao) with the life cycle of the Southern Armyworm Moth (Spodoptera eridania). This is a version of plate 26 in Merian's Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium. In the text accompanying the plate, Merian described how, the Cocoa Tree was grown in the shade of a large tree such as a Banana, to protect it from the heat.”

“This is one of a set of luxury versions of the plates from Merian's Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, published in Amsterdam in 1705.

To make these versions, Merian (probably assisted by her daughters) appears to have inked sections of each etched plate and run it through the press to create a partial print. While the ink of that print was still wet, she placed a sheet of vellum against it, transferring a reverse image onto the vellum. This 'counterproof' was then worked up and coloured by hand. The Royal Collection plates are partially printed and partially hand-drawn, the printing mainly being used for the insects. As Merian was only transferring selected areas of the printed image, she could vary the arrangements of the plates, with the positions of the butterflies and moths subtly altered to create unique compositions.”

#animals in art#european art#natural history art#scientific illustration#botany#entomology#life cycle#moth#Southern Armyworm Moth#Cocoa#World Chocolate Day#Maria Sibylla Merian#women artists#women in science#18th century art#Metamorphosis insectorum surinamensium#Dutch art#colonial art#Royal Collection Trust

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

💕, 🧡, 💚 for asoue!

💕: What is an unpopular ship that you like?

It's more of a platonic relationship for me (though I've read a short thing where this pairing was romantic, and would probably read more), but I have a soft spot for Hector and Widdershins in post-canon. Like, I have a soft spot for them, the Quagmire triplets, Fernald, and Fiona all living together post-canon in general, but I also like exploring the potential dynamic between these two in particular. The few remaining survivors from the Sugar Bowl Generation (and each of them being the only survivor the other keeps in touch with), the overly cautious one vs. the one who does not hesitate even when he ought to, two men who fucked up big time but maybe can make some amends now. I imagine they find each other annoying but also begrudgingly care about each other. Maybe not that begrudgingly as the time passes.

🧡: What is a popular (serious) theory you disagree with?

Miranda Caliban being Fernald and Fiona's mom. I have no substantial counterproof, I just don't vibe with it.

💚: What does everyone else get wrong about your favorite character?

It seems to me that everyone in the fandom actually has a good grasp of what Lemony is like? At least they did last time I engaged with it outside of my dashboard. The only wildly incorrect opinion I can think of is clearly an outsider perspective - that meme about how to treat the children of your dead beloved that uses Snape as the bad example and Lemony as the good one. He's no Snape, of course, but he didn't really help the Baudelaires either, unless you count cleaning their name in his books, and, if I remember correctly, we never learn if that even worked.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Climate Change

Long Post

Climate Change is a completely and utterly bullshit term. What they mean is Global Warming. The reason they changed it is the Global Warming is something that can actually be MEASURED. And if it can be measured, it can be refuted.

Every time a major weather event happens, people bring it out as proof of Global Warming, without the slightest effort to look into the data. I live in an area that became a worldwide exemplar for how Global Warming is killing us, but the fun thing is I’ve lived here my entire life. We had a similar heat dome 25-ish years ago. The reason it had record temperatures was that it happened earlier in the year than the last heat wave.

The Canadian government also uses REARWARD PROJECTIONS to prove the veracity of it’s forward projections for temperature. What this means is that we cannot believe anything the Canadian government says about temperature data. For the record, before the government did this, the temperature graph was basically flat.

Just before the change happened, there was a study that looked at mostly rural sites around the country, and showed no change.

But wait, is Carbon Dioxide a greenhouse gas or not?

Yes, yes, yes it is. And yes, for a time, the increase in global temperatures did match the increase in Carbon Dioxide in the atmosphere.

So, Global Warming is real then?

First, to put it into perspective, the three biggest contributors to global temperature, other than the Sun, obviously, (we’ll get to that later), is:

Water Vapour

Rayleigh Scattering

All Other Gases.

Carbon Dioxide is the biggest contributor from All Other Gases, but Oxygen and Ozone also apply.

Gas light absorption graphs are logarithmic. You need an order more gas to produce a linear increase in absorption. What this means is that at a minimum, for Carbon Dioxide to absorb more light, we’d need to double the current levels, and 10 times is not out the realm of the possible.

Before we jumped on the Global Warming bandwagon without any proof, (more on that later), the scientific consensus is that we were likely going towards a new ice age.

None of these theories are mutually exclusive. We added Carbon Dioxide to the atmosphere, and put off Glaciation, and then Carbon Dioxide reached saturation, (reached a point that it would require 10x more to increase the Greenhouse Gas Effect it can produce).

No onto some other issues that are often brought up as counterproof for Global Warming:

Acid Rain: We restricted the chemicals that were making acid rain. We did a fantastic job of cleaning up our emissions, until we started worrying about Carbon Dioxide.

Hole in the Ozone: This was caused by CFC’s, and we banned them. And the Ozone layer healed everywhere but Australia.

By contrast, CO2 is, literally, plant food. A number of green houses use CO2 generators because higher concentrations of CO2 allows them to grow more.

Alright, let’s say we want to stop producing CO2. Even if not for Global Warming, then as my father suggested, to save some carbon for when we’ll risk going back to glaciation. So, we want to reduce our carbon emissions, what do we do?

Solar Power: This takes a of energy to create. There are other problems, but the biggest one is that we don’t have storage. California has too much solar power, as they cannot store it for usage when they actually need it.

Wind Power: We are doing this in an insanely stupid way. I’m seriously, most wind turbines are the worst way we would do it. Wind Power is also highly temperamental, and we don’t have a good way of storing it.

These both work on smaller scales, and are something we can slowly lean into, but they cannot provide most of our power. Actually, we can learn from Germany. Germany had the highest amount of power from renewables in the world, and decided to increase the ratio. The rest of their power was from nuclear, so they shuttered nuclear power plants to replace them with solar and wind. But, solar and wind are temperamental, and you need something that can quickly spin up to make up for any shortfall. And that is fossil fuels.

So, Germany trades nuclear for fossil fuels, which they were getting from Russian. And then the Ukraine war started, and the US convinced the EU to no longer pay Russia for gas. And that’s how you get an energy crisis.

Nuclear Power: Canada solved all of the problems with Nuclear Power in the 60′s. And I do mean all of them. CANDU reactors CANNOT go critical, cannot meltdown, and can use natural uraniums, so they don’t need enrichment. Nuclear power is the only method we can quickly scale up for out usage. Quite frankly, if we are going to replace fossil fuels, this is the only method of producing power we can use to do it. Like I said, Solar and Wind can be developed slowly, but we need to work on storage.

The best / only way to store power in the grid currently is pumped hydro. Which works, extremely well, but the problem is that regions that can use pumped hydro can just use hydroelectric dams. Hydroelectric dams and geothermal power are both fantastic, but you have to have the right environment.

How can we store power?

Lithium: It works. It’s extremely expensive, extremely inflammable, and we probably don’t have enough for the entire world’s needs.

Hydrogen: Hydrogen fuel cells work. Hydrogen combustion engines work. Hydrogen never went away.

Synthetic Fuel: One of the major car racing organizations, (can’t remember which one), is planning to switch to wind-generated synthetic fuel that is made using atmospheric gases, (primarily CO2), and water.

And now for electric cars. If everyone switched to electric cars, it would be better for the environment? No. Ignoring the fact that a lot of people cannot use electric cars, the switch would cost most energy than we would save. Gasoline cars can work for 20 years without a problem. Electric / hybrid cars typically need a battery replacement after 5 years, which is often the same value as the car at that time. This means you cannot buy the car for any price, as you will have to shell out thousands, (maybe tens of thousands for a truck), for a used car. I bought my first car for $1,000. I traded it in for $500. Not only are we locking most people out of the car market, but we are making it so that financially, you might as well just buy a new car. For electric cars (US):

New Nuclear Power Plant every 2 weeks for 20 years.

Quadruple the electrical infrastructure in all regions, without taking growth into account.

Have every - single - apartment building have individual garage stalls that can have a charger hooked up.

Even then, it’s still terrible for people living up North, as the cold takes a HUGE amount of power from the batteries. With gasoline cars, we use waste heat from the engine to heat the cabin.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cottage Beside a Canal with a View of Ouderkerk (counterproof). ca. 1641. Credit line: Rogers Fund, 1919 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/391763

#aesthetic#art#abstract art#art museum#art history#The Metropolitan Museum of Art#museum#museum photography#museum aesthetic#dark academia

1 note

·

View note

Note

And how do you know they do speak to each other sincerely and support each other or show attention? Because all I see is Louise doing that for Alex but not the other way around. Alex certainly hasn't opened up to her since he keeps her at arm's length. So not sure where you get all this from. / I don't know, in fact I said "if for example" because from the outside we only have an idea of how it could be, we don't have counterproof or absolute truth

Again, are you aware on what kind of blog you are? I think you're missing the point here. Nobody claims to know absolute truth.

0 notes

Text

anon you're so funny why are you lying when counterproof is so easy to find

#also it took me so long to realise you didn't mean jeffrey lol#anyways i hope you enjoy my content x

0 notes

Text

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Three Nudes in the Forest [counterproof] (Drei Akte im Walde) [Umdruck], (1933)

0 notes

Note

I think Louis has matured. He became a dad,

Have you ever tried to know what his fans say about his 7 years old son? He clearly allowed it bc otherwise he would told then fuck of off. :)

I am not interested in that man to verify your theory. I am not interested in any proof or counterproof to your statement at all. I simply do not care about Louis Tomlinson and I can’t believe such an irrelevant man is causing so much discourse in my inbox and I have no interest in a prolonged conversation about him.

#last time I entertained any convo about him#people got mad mad#same with any convo about Camille Rowe

1 note

·

View note

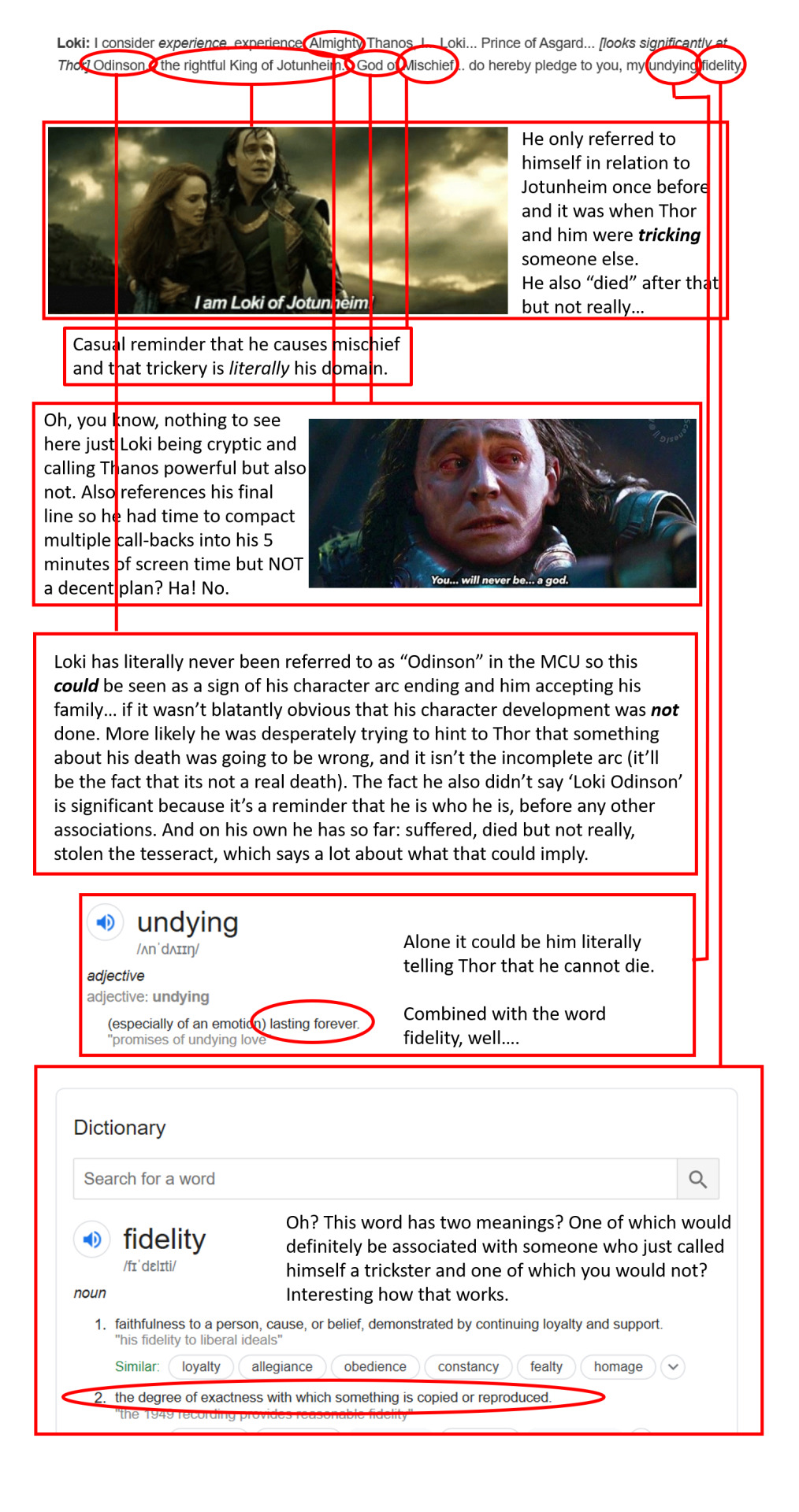

Photo

It is not “””denial””” if there is more proof supporting your claims than against it

#above: I analyse one line of dialogue in Infinity War in order to prove that Loki isnt dead#it may seem like flimsy evidence until you realise that the only proof against loki being dead is that we saw him die#which isnt even proof because we've seen that before#so nice try marvel you're going to have to do better next time#maybe start by actually showing a funeral#since only characters that actually die get funerals#(proof: tony peggy frigga. counterproof: natasha loki thanos)#see I can do solid evidence#tldr: loki didnt die. obviously.#TheBadKindOfDeath#TBKOD

135 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landscape with Four Trees and a Church at Right (counterproof), Augustin Hirschvogel, 1545 (?), Metropolitan Museum of Art: Drawings and Prints

Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1940

Size: Sheet: 6 1/16 × 7 5/16 in. (15.4 × 18.6 cm)

Medium: Etching; counterproof

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/336261

134 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two Soldiers Stripping Corpses; verso: Soldier Discovering Corpse (counterproof), Salvator Rosa, c. 1662, Harvard Art Museums: Drawings

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Frances L. Hofer

Size: actual: 15.6 x 11 cm (6 1/8 x 4 5/16 in.)

Medium: Red chalk on cream antique laid paper, laid down on verso of counterproof

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/295694

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

cursed concept: actually, dogen is loboto's kid. proof: blue(ish) skin, was the first one abducted; counterproof: loboto would not care at all if his kid blew up someone's head and would probably encourage it. also fun to imagine: sasha running around the motherlode with a photo of cal, asking if anyone has seen the escaped criminal and compton just looks at it and goes: that's my fucking son-in-law

Ok so firstly glad you added the “son-in-law” bit at the end bc I was right about to be like we know who loboto’s parents are tho,,,

Secondly I can’t quite see this even as a cursed concept, but I do admit the humor potential is crisp like an apple

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fauness and Woman (Faunesse et femme), counterproof, Pablo Picasso, (Oct. 5, 1945), MoMA: Drawings and Prints

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund

Size: plate: 10 1/2 x 6 1/2" (26.6 x 16.5 cm); sheet: 12 5/8 x 9 15/16" (32 x 25.3 cm)

Medium: Etching

http://www.moma.org/collection/works/67652

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rearing Horse and Rider, Antonio Tempesta , c. 1600, Cleveland Museum of Art: Drawings

Size: Sheet: 19.5 x 16.7 cm (7 11/16 x 6 9/16 in.)

Medium: red chalk counterproof

https://clevelandart.org/art/2003.274

20 notes

·

View notes