#eidolon diska

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In the small town of La Laiterie, the Mystery Solvers' Club of 1979 come home from their summer road trip solving cases around the country to find that, perhaps, some mysteries were closer to home than they realized... and far bigger than anything they could ever have imagined.

Finally done with this! Started working at it way back around the start of May. It's wild to think that it's been so long since I finished Disco/Ska... It's been on my mind ever since, and I suspect I'll be thinking about the story for a good while longer, too. There are some absolutely masterful moves pulled off in terms of metafiction, mindblowing use of the medium of an actual play podcast... not to mention that whole crew is hilariously funny.

Separate pieces for each of the cast:

And one Jordan Rogers:

#eidolon playtest#eidolon disco#eidolon diska#kris draws#eidolon fanart#eidolon diska spoilers#bob mcgovern#maurice bailey#kc cardenas#haley holst#jordan rogers

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reaching for each other in the everything and the nothing.

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

I. Introduction

A while ago, I wrote on how Jack Slash was a prime example of how Worm approaches metatextual commentary. Wildbow has a general tendency in his first two serials especially to identify common story tropes and give them in-universe justifications. Jack Slash in particular is a response to the tendency for writers to give plot armor to the Joker and similar sorts of popular villain characters. The out-of-story justification of the authors ("we can't have someone just shoot him, that's boring, besides everyone loves this guy look at him go") becomes an in-story aspect of his powers: an ability to subtly influence other capes behavior allowing him to always escape danger. Plot armor transformed into an in-universe mechanic that characters are aware of, react to, and work against.

Notably, this tendency is never used to highlight the status of wildbow's characters as characters— there is no fourth-wall breaking or attempts to undermine the audience's perception of the story as containing essentially a self-contained world running on its own internal logic. But this certainly isn't the only way you could comment on Joker-type charcter's plot armor: Funny Games covers similar ground using the opposite trick, repeatedly having its home-invader villains draw attention to how they're characters in a story, and that whether they win or lose is determined wholly by the author's will. Director Michael Haneke continually draws his audience into the story only to violently and repeatedly pull them out with suspension-of-disbelief-shattering acts on the villains part. It's The Treachery of Images as a horror movie.

Together, Worm and Funny Games showcase two different approach to explaining why the villain gets to live another day. If you can explain their deal using only the internal logic of the story ("Jack has a power that lets them escape consequences"), then the author is giving a diegetic justification for the trope justified by mechanisms of the story's universe. If you can't explain their deal without reference to them being characters in a narrative ("Paul can talk to the audience and rewind time because he's a fictional character and can do whatever the author says he can do") then its a "narrative" or nondiegetic justification for the trope.

These can be combined. Seidlinger's Anybody Home? used them together for awkward effect: serial killers perform acts that get recorded by some mysterious "camera" that produces a log of their events, which through mystical and mysterious means gets distributed to film producers and adapted into horror movies. Killers have fully "narrative" reasons for following horror tropes—they know they have an audience and are behaving for their benefit. But the story suffers from its awkward in-story justification, its "mechanical" framing: the audience the killers are acting for are other people within the story's universe, not the readers of the book. Characters realize they're "victims" in a story, but they're framed not as existing fully for the story but as normal people who got caught within a story, stuck in it like one gets caught in a storm.

In this post I want to highlight some more elegant ways of combining the mechanical and narrative approaches to metafiction, especially in regards to plot armor. I'll be commenting on wildbow's second serial Pact, Homestuck, and Eidolon DISKA, and heavily spoiling all of them. I've divided them into sections so readers can avoid spoilers or skip over works they're uninterested in, though they're not separate essays. I'd maybe recommend checking out DISKA if you haven't. Its great. Alright then.

II.

Pact and the otherverse gives its characters diagetic reasons for following tropes that align with narrative rules though its magic system. Otherverse magic largely involves telling the universe a story and hoping that your behavior has enough symbolic resonance that it believes you. A lot of the magic spells work on a "I dunno, this feels like it would work" logic.

This means that characters need to be aware of how characters in good stories would act, and often need to behave in a way that is believable if they were characters in a story. The result is that Blake Thorburn ends up purposefully trying to emulate a monster from a horror story, purposefully playing into the tropes of such a character. He acts like a specific type of story character, not because he's broken the fourth wall and knows he's in a horror story, but because he knows convincing the universe that he's a horror villain will likely lead to the universe letting him survive just a little bit longer before he collapses into an exsanguinated heap.

However, Pact's approach to the specific mechanics and abilities of Blake and other monstrous entities of his ilk is much more in-line with how wildbow previously approached Jack Slash. Horror-movie style monsters are a grab-bag of entities called "Boogeymen" within the setting, with little in common outside of previously being people who had fallen through the cracks of reality and climbed out of the abyss changed.

The tropes of slasher movies are once again given mechanical justification: the monster drives conflict and acts unpredictably because being feared gives its more of a foothold in reality. It can't stay dead (and keeps returning for sequels) because it can always climb back out of the abyss again, or be summoned by Scourges to be used against their enemies. Some of the ways the in-universe boogieman mechanics reproduce these tropes are explicitly narrative justifications—they're stronger if the universe sees their ends as especially "iconic," and Blake seems to be empowered the most when he leans into character and goes on a rampage— but for the most part, you could explain their deal without having to refer to their roles as characters in a narrative.

III

The same couldn't be said for Homestuck's take on the serial-killer trope, which is explicable pretty much only in non-diagetic terms. Which is interesting insofar as its one of the only parts of Homestuck that doesn't at least provide a diagetic fig-leaf for a character following a cultural script.

Much like Pact's Otherverse, Homestuck also formalizes many narrative tropes as diagetic, in-universe mechanical laws of its setting. However, it doesn't bother giving justifications for why the setting has such mechanics. There's no equivalent to "they're like this because the magic of the abyss;" Homestuck's mechanical rules are almost more in the Funny Games vein of being inexplicable if you don't accept that they're the consequences of this being a story.

But the narrative rules it draws attention to are often all its own. See, in some ways the setting of Homestuck is meant to be an obvious set of fantasy Bildungromane. The characters enter a game world, Sburb, and are each deposited on a planet with almost stock templates: Land of Wind and Shade, Land of Heat and Clockwork, etc. Each are filled with a population of simple game constructs with little personality outside of what's needed to drop lore tidbits, and a slumbering denizen connected to a personal quest tailor-made for the player. This sense of "generic fantasy world made for a generic fantasy quest" is heightened by Homestuck's constant references to other media containing famous lands constructed from fantasy stories: Peter Pan/Hook, the Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, Don Quixote, and The Neverending Story. (That last example makes up not only a substantial amount of aesthetic references, but also structural echoes; as Homestuck copies it by having a second half in which reader-stand ins enter the story, characters go from one world to another, and the role of author and audience gets muddled in a world-threatening manner.)

It seems like the game Sburb created the players different worlds to facilitate a typical Bildungroman adventure. Enter the fantasy land, meet the locals, learn the lore, defeat the monster. Unlike Jacob's Bell, The Lands of Homestuck don't make sense as anything besides a game construct, a way to facilitate this narrative arc. And the character's tendency to sidestep the quests set up by the Lands and skip through or break things feels like a subversion of those typical sorts of fantasy stories.

A complicating factor, though, is that the game was set up with the expectation that the players would skip around and break things. The entire game is composed of a series of time loops, including the characters creating themselves, creating the big bad in an attempt to defeat him, etc. Everything that happens in a game session was engineered to happen "by" the game—including the parts that seem to break the intended narrative arc of the Lands. There's plenty of things that seem to be breaking the "intended" experience: Rose taking apart her game world, Vriska reading the mind of her Land's consorts to find out all the lore they have pre-programmed in, Jack Noir killing the Black King before the players could face him as the intended final boss. But all of these turn out to be essential conditions for the game coming to exist in the first place, for the characters to create themselves, for the Lands to be created as game constructs in the first place. The game creates conditions that require the players to "cheat."

In other words, its not just that the comic is subverting a typical fantasy story. Its that Sburb itself is a game that runs on the narrative rules. Not the narrative rules of a fantasy Bildungroman, but the narrative rules of a subversion of a fantasy Bildungroman. The subversion is expected and built-in.

This subversion-as-the-rule is something Hussie enjoys making the narrative conciet of a story: early Problem Sleuth was written with the one rule that the audience could never be right about how the main character's office worked. Its also a feature of Homestuck's general approach to characters and dialogue. I think a good example of this is Eridan and Feferi's early conversations. They get introduced as the primary examples of a form of alien romance the narrative just got done explaining, a pair of moirails that the narrator declares are "made for each other". But of course, the subversion of that is already built in, as before Eridan's full introduction we learned that he wanted to be in a different relationship with Feferi. So when the first few on-screen appearances of these characters turns out to be their break-up texts, its a "subversion" of the destined romance the narrator set-up, but its a sign-posted and expected subversion.

But back in terms of Sburb's mechanics: players of the game who perform a ritual to achieve god-tier status can only die if their death is either Heroic or Just: that is, they can only die if it’s narratively satisfying. If a powerful character dies without it being a satisfying heroic sacrifice or a satisfying end to a villainous rein of destruction—in other words, if the death is uninteresting and narratively pointless, then the character pops right back up. Like in Worm, plot armor is a mechanic of the setting that the characters can find out about and exploit, and like with Pact's boogeymen, characters become whole new types of beings as part of fitting to a character narrative that'd require plot armor. But unlike in wildbow's work, Homestuck's God Tiers have little in the way of diagetic justification. Hussie knows that there are situations where an audience won’t accept the stakes set out before them—they can tell that the bad thing can’t be allowed to happen, because if it did the plot couldn’t continue or the story would suffer, so they know the bad thing won’t happen. Accepting this, they play around with the trope by having it literally impossible for the bad thing to happen if the story would be worse for it.

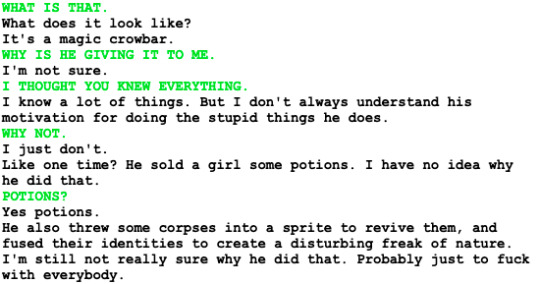

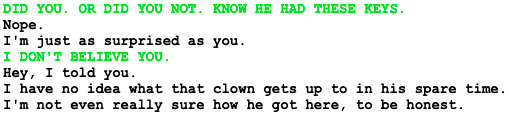

But where it gets weird is how this plot-armor mechanic gets applied to Gamzee, in one of my favorite sections of Act 6. Gamzee was introduced as a joke character riffing on the juggalo evil clown subculture, who later goes on a murderous rampage for reasons that are never made fully obvious in-text. He then scuttles about the story as a figure who keeps breaking the story’s rules: both the mechanical rules of how Sburb works and the rules of storytelling generally. This ramps up a lot in Act 6, where he puts on a fake god-tier outfit and starts showing up at times and places he should not be able to be based on the established mechanics of Sburb, which up until then had been incredibly strict parameters on the story. Unlike a lot of the items that loop back in time in convoluted ways, we don’t see how Gamzee appeared on Jane’s planet, or went to the future to raise the cherubs, or all the other shit he gets up to. And we aren’t given a reason for why he’s selling blood like an RPG merchant or why he’s raising the big bad or why he’s doing anything at that point. He becomes a deus ex diabolica, a character whose not really a character at all so much as someone who sets up the obstacles in the story and has no reason for doing so besides the fact that the story wouldn’t work if he wasn’t there to set up the stakes.

One especially odd thing about him though is that even though he never actually reached God tier, he seemingly couldn't be killed.

At first this seems weird. Gamzee is breaking a core mechanical rule of Homstuck: he's immortal despite not being God-tier. But then you remember that the mechanical rule of God-tier immortality was already just a formalization of a narrative rule: a character can't die if the story isn't done with them. Homestuck is breaking its diagetic rules, but following the narrative rules they reflect.

This meta-interpretation of Gamzee's immortality is strengthened by the fact that the above conversation is taking place between Andrew Hussie and one of their characters. Furthermore, said character is a fandom stand-in who later transitions into being an author stand-in. This character (Caliborn) is the main villain of Homestuck, and has been interpreted as everything from the chains of narrative inevitability, to the interface of the webcomic itself, to Homestuck readers with an unhealthy relationship to the work, to the viler tendencies of Hussie themself present throughout the comic.

Not the only such stand-in; nearly all the villains of Homestuck assume some authorial role, as Hussie has an ongoing theme of equating the author role to being a manipulator. Thus the most heroic characters generally are reactive rather than proactive, thus Doc Scratch/Vriska/Dirk/etc all trying to author the timeline or claim causal responsibility for events while manipulating other characters, etc. But Caliborn ends up representing some more of Hussie's specific creative tendencies, and is the only character that Hussie's in-comic self has a conversation with.

Notably, this conversation has pretty much the only instance of Hussie presenting all the weird obstacles of Sburb as something they've set up as the author.

Oddly enough, apart from this, the yellow yard, and the Spades Slick sideplot, "Hussie" as a character has all but no role in the story. Which is in keeping with their (possible farcical?) ethos of all their characters existing as their own entities/character types, with Hussie just expressing them. The Entities in Worm actually end up being more direct author figures than Andrew Hussie's own self-insert, since they at least perform the role of authors (control characters in a way that produces dynamic and interesting scenarios).

This is a part of why the Hussie stand-in apparently lacks knowledge of their own story, and gets surprised by it.

Hussie claims even they don't know where Gamzee got things, what he gets up to, or why he's doing what he's doing. The first two things are probably true, honestly. The actual author Hussie may not have an idea in mind for how Gamzee gets to any of the places he does, since its not really relevant to the story. It feels weird that he doesn't, since so much of the rest of Homestuck is tracking how various objects travel from one point in a timeline to another, but when there's no interesting answer to be constructed by the author none really has to be provided. Again, by this point Gamzee is a plot device that Hussie has dressed up as a funny clown for the audience's amusement, he's not really a character.

But if the Hussie stand-in is meant to be taken seriously when they say they don't know why Gamzee has the keys, then there's a disconnect between Hussie the character and Hussie the author. Since the keys do have a plot purpose that's revealed almost immediately, and that Hussie almost certainly had planned.

A weakness in metafiction generally is that having the author be a character in any real capacity lowers they're ability to be a true author figure. If the stand-in is surprised by something the author wrote, then they're not reflecting the author. If the characters kill the author stand-in, but the story keeps on going, then what the hell was the author representing?

IV

The only piece of metafiction I've seen that squared that circle is EIDOLON DISKA, which mostly suceeds because of its structure as an actual-play. It has a GM who serves as a narrator alongside being the voice of almost all the characters, but all the main characters are acted out by other people. So it can pull a lot of the standard metafiction moves in much more convincing ways. The narrator reveals that he's an in-universe character who they actually know, and whose been writing the story they're all in. When the player characters are still able to rebel and fight against the narrator, it works, because the PCs actually are representing other people making decisions apart from the GM. Even a character usurping the author ends up working, since it just means that character's player becomes the GM.

As you'd expect, EIDOLON DISKA is another piece that blends diagetic and narrative rules. Gods currently writing the story (aka the current GM) can't rewrite portions that previous gods wrote, because doing something so narratively unsatisfying would break their own godhood. Breaking the rules of the Eidolon rpg system also risks being usurped, since they're the narrative rules the story runs on, and the diagetic rules of Godhood are just narrative rules.

This gets most interesting when the characters end up dying, as will sometimes happen in an actual-play of a ttrpg where death is a mechanic. The podcast is divided into two time periods, with the first group being the founding members of their school's mystery solvers club. The second group are the members of the same club 20 years later, trying to solve the murder of the founders. Because the first group's death is a set event that the narrator already wrote would happen at a specific time, every time the characters in that first group die before that point, they have to come back. And once it becomes clear that they're characters, they become aware of this, and start abusing it. They take bigger risks, stop freaking out when their friends get hurt or killed in battle, start getting chatty with the increasingly annoyed grim reaper—in other words, they realize they have plot armor and start acting like it. Since they're aware of and secure of their plot armor, they use it more fully than Blake does. And since its an actual play instead of something written by one person, they're actually able to use that plot armor to be more than a villain thrown into heroes way like Jack Slash or Gamzee. DISKA isn't finished yet, but I have the most hope for it going into interesting places with plot armor out of any of these stories.

#wormblr#parahumans#homestuck#eidolon diska#eidolon playtest#wildbow#andrew hussie#Youtube#pactblr#otherverse#mals says

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jack Bailey is just as fucked up as the Shiragorov twins btw. you can even see the exact same problems in him as you do in both of them. he is Naomi's tendency towards perfection plus their later preoccupation with finding meaning in a fictional universe, blended with Jake's hunger for recognition, poured through a filter made up of Maurice's terminal main character syndrome and Flannery's need to bend the world to her will. Plastic Cup Politics is not the Eidolon of a man with a healthy relationship to his friends and family

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

The disco group having the exact same conversation that the ska group had about whether its B&E if an animal unlocked the door down to the conclusion that animals are not beholden to the law, thereby retroactively making the ska conversation a reenactment is really funny

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

pop/rock shirts i made! big thanks to @spades-gameing for some help with brainstorming.

#crtm#eidolon playtest#eidolon rock#eidolon pop#yeehaw this took way too long but i'm really happy with them both#the screen printing kit is nice but it's definitely more work with less precision than i anticipated#way cheaper tho and it's somewhat faster than lino. at the downside of not being able to keep the design unless you buy a new screen#and a screen is more expensive than just buying the lino#anyway moving onto other stuff for now#i picked up diska again and i REALLY wanna draw regina and charlie at homecoming

135 notes

·

View notes

Text

before ascending to godhood to cope you should try hrt or stimulants

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

how seriously (if at all) were you considering having Regina die in diska?? there was a while where it seemed like she was looking for an excuse to die. relatedly, do you think she ends up happy, down the line? really looking forward to the ska post-mortem!! you really did a fantastic job with Regina, she's such a compelling and interesting character

I'm just gonna throw this under a Read More lol. The post-mortem comes out next week but I don't touch on this the most there.

Extremely seriously, to the point where I was a little annoyed that she didn't face consequences during Disco 50 just because of the little trick Bob pulls so that everyone's alive after the fight. That said, I think its probably best that she didn't die.

After her phantom fight she definitely is re-evaluating why she's doing all of this for people who she doesn't know who are friends with a guy who will grow up to kill her girlfriend. So when she asks Kacey if she wants to leave (and she was counting on Kacey turning her down), that's the last straw, right?

She wanted to die in those moments very badly, but when the draws came around, it didn't make sense for her to accept the deaths in ska 48 and 49, especially being offered The World both times. In-character, what was going through my mind was her taking the card that wasn't The World would be exposing that pain to the rest of the team in a way she didn't want to - they can literally hear her choosing what to take, so she takes The World both times because she cannot let them see her vulnerable.

The whole thing with Regina that I came into the season with is 'Pride as a mask,' which is why all of the shadowy figures in her eidolon have animal masks, its why she won't let anyone in close, its how I feel constantly lol.

I would like it if she ends up happy. I'm not going to say she does one way or another, and I don't think we're ever going to revisit these characters. It would go against everything we did this season to say whether or not she's happy. That's up to her.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

eidolon diska is so fucking good guys. have i mentioned how good eidolon diska is?

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you think reading umineko could fix jordan

my understanding of Umineko is that it mostly consists of a pathetic guy trying and failing to solve mysteries while a witch (who may or may not have ever existed in any meaningful way) taunts him about his limitations while asserting her own omnipotence.

so no. I am reasonably certain that the best-case scenario for "Jordan Rogers reading Umineko" is that he becomes a transgender kinnie and somehow even worse as a person in the process. we're talking Baby Bear II here.

#ask#anon#eidolon playtest#eidolon playtest spoilers#(for diska part one)#thank you for the question.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the small town of La Laiterie, the Mystery Solvers' Club of 1999 set out to do the same thing as all past graduating members have done for their senior year of high school: try and piece together what happened to the very first Mystery Solvers, who disappeared under mysterious circumstances in the year 1980. However, they quickly realize that there is more than meets the eye to their small burg...

Finally done with this! Started working at it way back around the start of May. It's wild to think that it's been so long since I finished Disco/Ska... It's been on my mind ever since, and I suspect I'll be thinking about the story for a good while longer, too. There are some absolutely masterful moves pulled off in terms of metafiction, mindblowing use of the medium of an actual play podcast... not to mention that the whole crew is hilariously funny.

Separate pieces for each of the cast:

And, of course, Bug!Solo, Fang and... just a McRib?:

#eidolon playtest#eidolon ska#eidolon diska#kris draws#eidolon fanart#eidolon diska spoilers#kacey chambers#regina rosenthal#charlie o'neil#solo apogee#solaris apogee#jake shirogorov#naomi shirogorov

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

The third season of Eidolon Playtest has done more with its medium as an actual play show than I’ve considered possible. It’s amazing how many new ways it finds to fuck with the basic expectations inherent to its format. And it somehow did so while presenting itself as an entirely different medium. Seriously, if you want to widen your idea of what a ttrpg-based show could be (or even what a ttrpg itself could be), then listen to Eidolon DISKA.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"No, he's unreliable"

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

KC Cardenas accidentally cosmically forcefemmed Fang. discuss

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

i swear there's a riff in the Ska "positive downtime" track that sounds just like Lonely Rolling Star and I can't help but notice it every time

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posting this analysis I did on a transfem Jake reading after crystal mentioned it in the discord because I'm proud of what I've written and I think there's some interesting stuff here.

The transmasc read of the Shirogorov twins is the one that is more obvious/easier of course but a transfem reading is very interesting and compelling. In this read Adonis's aggressive gendering of Naomi as his Wife would not be exclusively the enforcement of cisheteropatriarchal marriage, instead being an attempt to affirm her gender while ignoring the more complicated aspects of it and still both re-enforcing heteropatriarchal marriage and now also being a bit (a lot) of a chaser about it (or at least he is very transmisogynistic about their marriage). Jake identifying himself strongly and specifically as "a man" (instead of Naomi's less traditionally gendered identification as "a detective") reads as repression in this lens, as well as defining himself as a sort of Un-Naomi (an observation that valerie @ty-bayonet-betteridge had made) and if Naomi is the one with more gender going on then clearly they are the Trans One™ (and thus the Girl One™) leading to Jake, like Adonis, flattening Naomi's gender in order to validate his own (by taking ownership of the role he was forced into as the Self discarded by Naomi in order to be Naomi (Nikolai allowed Naomi to be a person and to transition but Jake was denied personhood and thus also transition.)) It is interesting that the things which most directly imply a transmasc read of the twins are introduced or implied by Jake himself, which implies that it either points to the more complicated gender stuff going on with both of them or is a symptom of the way Jake tries to "Own his masculinity." It also serves the purpose of further endearing KC to the twins' plight with Nikolai (and specifically Jake's suppression) by presenting it not only as abuse but transphobic abuse specifically. Which ties into Jack and how he is socially cis (regardless of which direction you read the twins as trans in) and has subdued his Naomi (and thus is also repressing the non-masculine aspects of his gender) which Jack specifically describes as him not being "broken" which through this lens reads as him repressing both his plurality and his transfemininity and speaks to an attitude towards both which Jake also has where they are both weaknesses which he should not have (another reason why he genders himself as male and antagonizes Naomi.)

I also think the Jake vs Jacob distinction is interesting because as far as I can remember Nikolai is the main person who calls him Jacob, although given that's how he is credited in the finale I could be forgetting something there (which if I am it is likely either Merlin calling him that or him "reclaiming" the name as part of becoming the detective prince/"manning up and getting a real job" both of which would back up my further analysis.) This brings to mind Bob and their name being the shortened form of a more masculine given name, which is explicitly a denial of gender identity by authority figures, which Nikolai and Merlin both are. Jake being credited as Jacob is thus a sign that he, like Jack has repressed/given up on his transfemininity in order to "grow up" and assume his role as the director of the FBI and the head of the Shirogorov clan.

It's definitely a very interesting read on the characters and one worthy of further analysis, although I would need to do a closer re-listen to do more.

8 notes

·

View notes