#especially how common rape was on plantations

Text

They’re literally saying enslaved Africans benefitted from Slavery in Florida now. We’re literally about to have the worst decade imaginable if we don’t vote these idiots out.

#like it’s gaslighting#they refuse to teach about the horrors of slavery too#especially how common rape was on plantations#the way they warped Christianity is fundemental to the US as well

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

No but for real can we TALK about how there is some genuinely offensive shit re: the Romani in Kleypas's book that gets a pass, but the in-character stupid line stuff gets cut bc it's the 21st century or whatever. Like I generally like her books, but if there's something to update that should be it!

Yeeeeah dude it really bugs me, ESPECIALLY because I feel like there's really zero excuse. Beyond just "educate yourself Lisa" ... she's aware that her books have "race issues". Because the incident that I'm pretty sure helped kick this off was Hello Stranger getting called out for a racist passage. Her oldest books (which she's essentially let go out of print) have been critiqued re: race. While there are some complex intersections re: race and ethnicity at play with Cam and Kev, I still feel like the fact that she's aware that her books aren't perfect re: race means she has to know those aspects are problematic.

I knew Seduce Me at Sunrise had edits to the moment when Kev kidnaps Win.... and though that's honestly one of my favorite moments in the book, I though maybe the edits were meant to be downplay the kidnapping as Kev's Mystical Rom Dude Ritual moment. Which I don't remember being HUGE in the act itself, but in dialogue, etc. But no! I was just basically taking away the aspects of "ravishing". Which is fucking stupid, lmao. Because in no way could you read the line about "she was going to be ravished" and interpret it as "Kev is going to rape Win". Why? Because we are in Win's head when that happens, and she is literally like "FUCKING FINALLY".

(Personally, I think Lisa unintentionally wrote Win as having a bit of a rape fantasy/CNC fetish vibe, and like... that's fine. People don't like to talk about it, but rape fantasies are among the most common fantasies for women to have, and it is fine, and it is one reason why a lot of people like old school romances, dark romance etc.)

But all the weird shit wherein, for example, Cam will be all "YOU ENGLISH DON'T UNDERSTAND, WE ROM DO NOT VIEW A HOUSE AS HOME" when like, the a good chunk of series revolves around the Hathaways basically doing a massive home reno in which Cam and Kev are both quite invested lmao, stays. The weird asides about Kev's hot-blooded Rom nature stay. (And might I add, lol... Kev seemed a lot more disconnected from that stuff, and one thing I dislike a good bit is that him shedding his inhibitions with Win and letting loose is like, aligned with him letting this Rom aspect of his personality that he'd been denying... free. The shedding of Kev's sexual inhibitions are aligned with his heritage, because in these books Lisa basically uses Roma to suggest "wild, untamed sexuality". And after his own book, Kev is significantly more involved in Cam's "let us help these unknowing English people with our mystical ways" stuff than he was before. Because now that he's fucking Win nasty the way he always wanted, he's like... more... Rom....? I love Kev and Win, but I hate that.)

Lisa is by no means the only historical romance writer who's done this. I think there's a grand tradition in historical writers working around the aughts especially where you get the vibe that they're like "well, I want to acknowledge that poc existed back then, and I want to portray them positively" but they also don't want to invest in deep characterization or push their (let us be real, often racist) readership too far... So it'll be like "here's the hero's best friend, a former slave!" "here's the hero's half-brother, also a former slave because their dad owned a plantation!" (Read a Tessa Dare book that did this, and I can absolutely see what she was going for, but it didn't come off well.) I love Jennifer Ashley's Mackenzie books. I LOATHE The Seduction of Elliot McBride because she tried to incorporate India into the narrative by having the hero like, live there in the past as a colonizer, and be all "India is amazing, here are my friends because I like Indian people more than white people now" (which, woof, but very common at this time) but lmao his buddies were his employees? And also his illegitimate daughter whose Indian mother was DEAD? Like, come on dude.

(Still not quite as bad as the Kerrigan Byrne book wherein the hero is a literal former war criminal whose big kindness was taking the lone survivor of a village he massacred home and making him his valet. But still.)

And I mean, this does continue, which in some ways I view more harshly because there has been years for feedback and critique to accumulate so more recently working authors should know better. Like the Evie Dunmore "hero has a Plot Important Dancing Shiva tattoo except that isn't actually Shiva in any way, shape, or form and also let's throw in a predatory villainous gay man for good measure" book.

And I'm not saying that Lisa's work is as egregious as those examples. I'm not. But none of the above examples are going back and revising their work in minute detail, while missing the most problematic aspects of the work lol.

I'll also be real and add that another huge reason why these edits suck is that... Nobody is saying you can't edit your work. Authors can and should be able to do that. But... It sucks when people don't know that they're buying what is essentially an abridged version of your book, especially when the edits are heavy, as they are with certain books. Someone could've read your book 10 years ago and when they buy it on Kindle now because they finally have an e-reader, they should be able to know outright that they're buying a different version.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, In my story I have a male slave born to another slave that's the product of rape by the slave owner. He is the same age as the slave owner's daughter who first treats him poorly but as they grow up with the changing times she begins to understand that slaves are wrong and starts treating him more as the half brother he really is. How quickly could things change and how helpful would news of nearby slave rebellions be? I can't figure out a suitable timeline.

I’m unclear on whether you’re asking about how quickly things could change in the broader society or with the personal relationship between these two characters but I can talk a little about both.

Personal change takes time, often years. Though I get the impression it is easier for younger people. A lot of people who grow up accepting awful things later reject them.

I get the impression that this sort of thing didn’t happen very often in plantation slavery. However now that I’m looking I don’t actually have any data to base that on. Certainly a lot of the children slave owners had went on to become slave owners themselves and support slavery. But that does not mean all of them did.

As a general rule I would advise you to be aware of the time period and culture you’re writing about. There’s a lot of romanticisation of slavery and slave built societies in fiction. There are a lot of stories that take agency away from enslaved characters so that other (usually white) characters can act heroically for them.

I don’t think any of this means that you can’t or ‘shouldn’t’ have a character born into a slaving family/culture becoming a good person. But it does mean there’s a lot to balance and navigate with this sort of scenario.

Above all else I’d suggest making sure these characters get an equal amount of focus, an equal amount of agency and that the enslaved character isn’t overshadowed by his sister.

Remember that, as Ambedkar put it, there can be better or worse masters but there are no good masters. A master can not be a good man.

Repairing the relationship between these siblings is going to be tricky, even once the daughter has become an abolitionist.

Trust is difficult for people trapped in these scenarios. Some slave owners, historically and today, hire people to ‘test’ slaves. They send these people among the slaves talking about escape plans, or plots against the owners, or even just offering an ‘illegal’ amount of support and friendship. And then they punish the people who respond.

So there is bad blood here but there is also a real sense of threat for the brother.

Giving this woman a chance isn’t just an emotional risk, it’s one that could have potentially lethal physical consequences for himself and those he cares about. So he needs a good reason to take that risk. Preferably one that shows the readers a bit about the kind of person he is.

It’s going to be a lot more believable if she acts rather then just saying the right things. And acts in a way that is genuinely helpful to her brother, rather then assuming what he wants or doing something that puts him at greater risk. This means listening to what he says and paying attention to her surroundings. For instance if he asks her for food and she knows that the slaves are punished if they’re found with food what steps is she going to take to ensure he doesn’t get caught or punished?

From his side establishing a relationship is a real and terrifying risk. From hers it… would probably seem like a very slow and difficult process that would probably become quite frightening as she got to know him better.

Because, depending on the setting and ages of the characters, this might be her first encounter with serious mental health problems. As far as I can tell the vast majority of enslaved people grappled with mental health problems at one point or another. Getting to know someone and realising that they are suicidal or severely depressed, seeing a panic attack for the first time- These can be frightening experiences and they’re things she’s more likely to encounter as the relationship develops.

If she can provide material help and emotional support during these episodes that is likely to help her case.

The whole thing is like to involve a lot of… two steps forward one back if you know what I mean.

It’s impossible to unlearn decades of prejudice and privilege in a day and how ever much this character is working hard to be better it isn’t her brother’s job to help her become better. Or to hold her hand while she tries to come to terms with the horror he has lived.

On a more personal note I think that a lot of fiction handles re-connecting with family, especially dysfunctional or abusive family very badly. It tends to assume that people should want family connections and should desire reconciliation.

This isn’t always the case.

So much fiction uses this, the prized place blood-family is put in, to put the pressure on survivors to forgive, forget and embrace the abuser when they’ve done the bare minimum.

In this case I think rejecting slavery is the bare minimum. I understand that the character is going further then that but- Is there a reason for the enslaved character to view her as a half sister? And if he does would that help or hinder their relationship?

Consider whether he’d be more comfortable rejecting familial terms. He might be; considering that his ‘father’ abused his mother and played no part in raising him. He might also find it easier to accept his half-sister as a growing, improving person and a friend if he doesn’t see her as family.

Because if she’s ‘family’ then it is crushingly unfair that he was abused while she had a ‘good life’.

Circling back to the main part of the question this kind of relationship change does take years. But how many depends on the individuals involved, their capacities, personalities and the effort they’re willing to put in.

I’m guessing. This isn’t something I can turn to statistics for. I think a minimum of 2 years sounds sensible, 5 sounds more reasonable and you could go as high as 10.

Part of the decision probably depends on what you want to do with the story. Having these characters drifting in and out of each other lives, helping, working together, then arguing and splitting up in a cycle could work for the longest time frame. Having them thrown together in adversity, working consistently against a common enemy could work well for the shortest time frame.

Think about how likely their personalities are to clash and whether any of the enslaved character’s symptoms are likely to make the relationship more difficult.

I don’t think news of near by rebellions is likely to help these characters build a friendly relationship. I think that it would put pressure on both of them, making them both feel under threat.

With rebellions near by slavers often became increasingly paranoid and meted out increasingly lethal and increasingly dramatic punishments. He would feel as if even the slightest transgression, such as speaking to the master’s daughter, could lead to him being tortured to death.

These rebellions often involved torturing slavers and their families to death. So she would also feel under threat, despite her beliefs. These rebellions did not tend to pause and consider sparing anyone associated with slavers.

And that action, that violence, needs to be taken in the context of the constant violence and degradation that was meted out on the enslaved.

On a societal level the pace of change is even harder to quantify.

It could potentially happen very rapidly, as it did in Haiti. Or it could happen very slowly indeed as it did in the United States, with abolition leading straight in to laws that stripped away the rights freedom was supposed to grant.

I think it’s important to understand that violent rebellion often didn’t lead to lasting societal change. In fact Haiti is the only example we have of a well recorded, successful slave rebellion. The wars in Brazil, Jamaica and Cuba went on for decades, if not hundreds of years. They didn’t overthrow slavery, though they did help a significant number of enslaved people.

To understand how these movements worked and what they achieved I think it’s important to look at more then one country. I would suggest Haiti and Brazil are both excellent places to start.

And if the historical pace of change seems too slow, remember there’s nothing to stop you deciding that society changed more quickly in your world.

I hope that helps. :)

Availableon Wordpress.

Disclaimer

#writing advice#tw rape#tw torture#tw slavery#tw child slavery#writing slavery#resistance to slavery#anti slavery movements#historical slavery#writing victims#haiti#torture survivors and relationships#tw suicide#tw self harm

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Misogynoir

- What is it?

The term misogynoir, which was made up by Moya Bailey, a queer black feminist, blends the words misogyny (hatred of women) and the French word “noir” (black) to explain the intersection of racism and sexism that black women experience. This manifests itself in many ways, including adultification of black girls, stereotypes, racial bias in the healthcare system and cultural appropriation.

Adultification of black girls

In 2017, a study from Georgetown University found that adults viewed black girls “as less innocent and more adult-like than white girls of the same age, especially between 5-14 years old.” When compared with white girls, black girls were perceived as needing less nurturing, protection, support, and comfort, being more independent, knowing more about adult topics, including sex.[1]

Adultification leads to rape culture, victim-blaming, sexualising and human trafficking of young black girls. Many black girls have at one point in their childhood, been told by an adult to not “be fast” or “dress grown”. A child is a child, so the issue lies with adults who do not perceive them as children and sexualise and prey on them. More than 20% of black women are raped during their lifetime – a higher share than among women overall, yet their rapists get significantly less jail time than if the victim was white. There is a link between imprisonment and sexual abuse and little black girls fall victim to “The Sex Abuse to Prison Pipeline”.[2]

Black girl stereotypes

Black women face many stereotypes and they all have dangerous consequences in society. Many of them originate from ideas that were established during colonialism and slavery. The four most prominent stereotypes are The Jezebel, The Sassy Black Woman, The Angry Black Woman and The Strong Black Woman.

1. The Jezebel

Black women have been hypersexualised since the beginning of slavery. White men justified the rape of slave women, saying that black women were insatiable. As a result of this, nowadays, many fetishize and dehumanise black female bodies and black women who report sexual abuse/assault are gaslighted by law enforcement and society.

2. The Sassy Black Woman

This stereotype portrays black women as one-dimensional, loud, finger clinking and neck rolling caricatures. Black women are complex and multi-faceted. Limiting black girls to these “funny in the 2000s” images dehumanises us. It is no shocker that non-black women can not empathise or recognize with black women’s pain when they do not see us as people.

3. The Angry Black Woman

This stereotype paints black women as irrationally angry and hysterical compared to both men and non-black women. People often say that black women are aggressive and scary for doing the exact same things that non-black women do. This concept belittles black women’s valid anger by portraying it as an inherent character flaw and not a logical reaction to offence or discomfort.

4. The Strong Black Woman

Black women enduring extreme hardship during slavery created the belief that we are impenetrable. The idea that we are strong all the time and can face any obstacle on our own is toxic. When men and non-black women think we can withstand anything, they are more willing to treat us deplorably. This leads to the physical, mental and emotional exploitation of black women.

Black women and pain

“Black women don’t feel pain”, “Black women exaggerate”

The idea that black women can not feel pain was established during slavery, as black women bore the brunt of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse while also enduring pain of working on plantations. This demonstrates itself in medical professional’s dismissal of black women’s pain and belief that black women have a higher pain threshold. Why must black women face scepticism from the people that are supposed to care for us?

In the mid-19th century, Dr. J. Marion Sims, “the Father of Gynaecology”, built his career on experimenting on black women’s genitalia without anaesthesia. He did it because of the racist notion that black women do not feel pain. He was free from moral, political, and economic judgment. Sims is praised for his findings of reproductive health, but history fails to recognise the black women whose bodies were instrumental in modern medicine. A lot of out knowledge about pregnancy came from experimentation on black women, so why do we have a greater chance of dying when we give birth in a hospital?[3]

Racism in the medical field is still very rampant, black women are 4-5 times more likely to die during childbirth than white women, and 2-3 times more likely than Hispanic and Asian women. This is not because of genetics but the racial biases of doctors and nurses. When taking the Hippocratic Oath, doctors make a commitment to the human condition, that includes black humans as well. Doctors need to listen when their black female patients express their concerns and not minimise our pain. Beyoncé and Serena Williams share a story in common that tells how they were treated inadequately by doctors. These ladies are rich, famous, and black, so think about how it is like for the average black woman.

Ways that Cultural Appropriation harms black women

- Cultural Appropriation mocks black women. Non-black people have very limited knowledge of black culture due to the lack of diverse portrayal of blackness in the media and when they imitate us, it is apparent. What is worse is black men playing the parts of black women in film/tv, because they feed into these stereotypes. When they think twerking, being aggressive or wearing braids are “acting like a black women”, they are telling us they we are a costume not a person, if you do not see us as more than a caricature you will continue to dehumanise us.

- Cultural Appropriation devalues us. When black women wear black hairstyles, they are described as messy, unprofessional, and dirty but when a white woman does the same thing, they are ground-breaking, cool, and edgy. This also applies to black women’s natural bodies and complexion. This double standard shows that society accepts black women and their culture when it is plastered on a white or non-black body, exhibit A the Kardashians.

Full credit to: @michaelabalogun on instagram

[1] https://www.law.georgetown.edu/news/research-confirms-that-black-girls-feel-the-sting-of-adultification-bias-identified-in-earlier-georgetown-law-study/

[2] https://www.law.georgetown.edu/poverty-inequality-center/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2019/02/The-Sexual-Abuse-To-Prison-Pipeline-The-Girls%E2%80%99-Story.pdf

[3] https://www.heart.org/en/news/2019/02/20/why-are-black-women-at-such-high-risk-of-dying-from-pregnancy-complications

1 note

·

View note

Text

New from A Reel of One’s Own by Andrea Thompson: ‘Antebellum’ is a disappointment of historical proportions

By Andrea Thompson

This movie should not be this bad this movie should not be this bad this movie should not be this bad this movie should not be this bad this movie should not be this bad this movie should not be this bad this movie should not be this bad this movie should not be this bad this movie should not be this bad

Forgive my attack of insanity. But I have seldom seen a film that knows how to do so many things so well…except for what it’s trying to do most. “Antebellum” opens exquisitely, on a southern plantation we’ve seen so many times before. It’s quite actually clever in how it shows us exactly why we return to such settings, which in many ways contain such beauty.

It’s not exactly a new approach, yet it still couldn’t be called common, in film at least. In Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” Sethe recalls Sweet Home, the farm that birthed such horrors, marveling at how such things could coexist. “It never looked as terrible as it was and it made her wonder if hell was a pretty place too.” The setting in “Antebellum” seduces in much the same way. Just try not to appreciate the beautifully lush landscape, especially when it comes with an adorable little white child in a yellow dress bringing flowers to a mother who is all smiles and benevolence as she gazes down at her in 19th century clothing which seems perfectly suited to a time and place that seems to cradle them in a gentle embrace.

Then “Antebellum” turns its gaze deeper, or rather, just past them, to the soldiers, and to those they and these supposedly beatific inhabitants have absolute power over, the enslaved who make the comfort we’ve just seen possible. It’s also the beginning of many dashed hopes, since things pretty much start going downhill after that. But we’ll always have those two minutes.

Lionsgate

“Antebellum” is clearly trying to make a point about how slavery’s violent, brutal past is lurking around every corner in our so-called enlightened, modern world. If only it showed any interest, any at all, in delving deep and exploring just how shockingly adaptable hatred can be as it continues to dehumanize and twist our perceptions of each other. But “Antebellum” would rather inflict brutality after brutality on Black bodies to prove its point, especially on Eden (Janelle Monáe) after her attempt to escape fails.

Monáe has done (and continues to do) fantastic work as one of our great modern artists before she branched out into acting, resulting in some truly incredible performances, such as on the series “Homecoming” and other excellent, mainly supporting roles in films as wide-ranging as “Moonlight,” “Hidden Figures,” and “Harriet.” She deserves better than the thankless one she has here, where suffering upon suffering is inflicted on her, as if we needed it to realize the horrors of slavery.

If there is any redemptive quality in “Antebellum,” it’s due to Monáe’s awe-inspiring skills as an actress, which are on full display as the camera lingers on her endlessly expressive face, not the violence itself, so we at least feel her pain throughout the entirety of the movie’s runtime of ill-advised (to say the least) choices, which includes branding, miscarriages, burnings, rapes, shootings, and other aggressions she and various Black characters suffer.

Even when the twist is revealed, and we see just what the connection is between Eden and her modern counterpart Veronica Henley, who is an extremely successful author with a loving husband and young daughter, it only makes the movie’s flaws that more apparent. And baffling. A good premise doesn’t necessarily have to be plausible to be horrific, as “Get Out” proved. But since “Antebellum” has only shown us the consequences of its scenario, with no true connection to our modern world, there’s no real emotional grounds for horror, resulting in the same lack of empathy it accuses the various white villains of.

Lionsgate

Said villains, the most notable of which is Jena Malone as a white feminist from hell, are also given no depth or exploration whatsoever, leaving us to hate them for the evil they inflict while ironically reassuring white audiences how safely removed they are from such deeds. Malone’s would be laughable if she didn’t channel pure viciousness so well, even as she’s saddled with a cartoonish southern accent and predictably icy persona. This has long since ceased to be edgy, given that we’ve been forced to acknowledge how white women weaponize their privilege on behalf of white supremacy. It’s surely no accident that as the villains begin to be punished, the most sadistic is reserved for Malone. Not that it even compares to what Monáe has had to endure.

When the dust has settled, there is likewise no hint of the greater conspiracy/movement that the movie has hinted at, and we only get the comfort that such cruelty has at least ceased…for now at least. What another, final letdown for a movie that clearly seeks to hold us, and history itself, accountable.

Grade: D

from A Reel Of One’s Own https://ift.tt/3mCxfc2

via IFTTT

from WordPress https://ift.tt/2RHOc6J

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

‘The legacy of the enslavement of Africans is still with us.’

The legacy of the enslavement of Africans is still seen today within two main institutions - schools and their education, and the Criminal Justice System. These two institutions are creating and perpetuating racial hierarchy through teaching an ethnocentric curriculum disregarding any black culture until one month of the year, and through racial discrimination which unfairly targets certain sets of people due to what they appear to represent rather than their actions. The two institutions involved maintain a level of inferiority pushed onto blacks and enable the systems of punishment to legally discriminate in ways that were acceptable during the enslavement period. By maintaining the subordinate position, many ask was slavery declared dead or just reincarnated through new institutions. This legacy haunts many today and questions the level of emancipation that has been ‘gained’ over the years. In this essay, I will argue that the role of education and police relations for those of African decent are intrinsically linked and that one often follows the other in what is known as a self perpetuating situation. Within education the example of the Jena Six incident in 2007 explains this view as well as the deep rooted racism that occurs in nearly all schools across the world. The police relations and Criminal Justice System also have deep rooted racism links and the example of Rodney King in 1991 and the events that followed show this in great detail. These specific instances are both recent points in history when the legacy of slavery can still be seen impacting lives after 129 and 145 years since the emancipation of all slaves was proclaimed. As James Baldwin said, the great force of history, comes from the fact that we carry it within us, unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do. Much political thought surrounding the situation have the mentality of ‘we are here because you were there’.

Firstly, in education the idea is that all students are taught the same lessons and subjects and it is their responsibility to work hard and achieve in order to move up in the world. However, research over the years has found this not to be the case.

Many education systems hold unconscious racial profiles and teach accordingly, often these are based upon stereotypes held by generations or images portrayed in the media. Blacks are often pushed into more physical activities and this could be based upon the idea that slave owners had a preference for athletic specimens on plantations. Schools stereotyping races into different areas of academia often leads to a poorer education and expectation of failure for the black students. If asked, schools would deny any aspects of institutional racism and through education we are taught a learned ignorance - we can see race but we aren't supposed to really see it. What this means is the colour of someone’s skin is still, subconsciously considered a marker of identity which was commonplace during slavery. Even when teachers aren’t subconsciously racist the system of education unfortunately is, and perpetuates the inferiority of black cultures as well as other non-Western cultures. There have been asks to include more culturally diverse teachings with education at all levels, yet this faced huge opposition especially to the changes designed to provide instruction in mother tongues, black studies and the appointment of more black staff in order to supply a role model and cultural diversity to an ever-continuing white system. By sidelining other histories especially, it reflects a racist ideology and cultural homogeneity which in turn causes an educational disadvantage among black children. Black Marxism believes that this hegemony maintains the position of power and by negating ‘others’ histories and cultures creates disadvantages within races.

A educational disadvantage is clearly shown in the Completion Rates of 18 to 24 year olds - those who left high school holding a basic education. The completion rate of Blacks was 86.9% in 2008 compared to 94.2% of whites - meaning that 3,744,000 blacks had a basic education compared to 16,018,000 whites. In 2008 only 13.7% of blacks held this educational level compared to 62.3% of whites. These statistics show that the education deprived blacks massively and this separate and unequal education impacts more than most realise. With less blacks achieving the basic education, it then stops them achieving success and stunts their influence in the world forcing them into manual, low paid jobs often then housed in poor areas overrun with drugs and crime, which often ends in prison time. This stunted success keeps them at an inferior position much like the enslaved Africans unable to change their subordinate position. Black Liberals take the view that racism was to justify slavery and this is now the primary impediment to social progress in the world today. As long as there is racism, social progress will be stunted and disadvantage those of colour.

The Jena Six incident of 2007 illustrated how the institutional racism and tensions caused students to turn on each other, it also highlighted how responses to students are very different and how stereotypes can affect these outcomes. In Jena, Louisiana a high school that was predominately white had a long history of racial tensions from traditions that were continued into the 21st century. Students of white and black sat on opposite sides of the auditoriums, held separate dances and a common race-based practice involved a ‘White Tree’ where only white students sat. One black freshman asked to sit under this tree and shockingly the following day three nooses were found hanging from a branch. This is a clear link to the lynchings that haunt black history and was commonplace in slavery in order to scare into submission. The school spoke out against the ‘prank’ and no action was bought against the white students involved, this sparked the growing tensions and it resulted in clashes ending with a group of black students beating up a white student. One of the boys involved, Bell, who was only a minor at the time was charged with attempted murder and subsequently jailed. There was a national call to release this student and the school was put under fire for the way they punished the black students severely but did nothing to the white students that started this race-related conflict. More than twenty thousand supporters marched on Jena due to the severity of the sentence given making it the biggest civil rights campaign since the 1960s.

The Criminal Justice system and the criminalisation of certain communities is anchored in slavery as well as implying the view of a constrained emancipation, especially for those victimised by the system. Blacks are often the face of crime and the overpowering stereotypical image of deviance. The negative relations between police and blacks can be seen in the example of Rodney King. In 1991, he was caught after a high speed chase, the officers pulled him out of the car and beat him brutally while a cameraman caught it all on videotape. The four officers involved were indicted on charges of assault and excessive use of force. However, a predominantly white jury acquitted the officers sparking violent riots in Los Angeles., King became a symbol of racist tensions in America. In 2012 King spoke with The Guardian stating the assault was “like being raped…being beaten near to death…I just knew how it felt to be a slave”. The fact King was beaten by white officers increased the distrust the black held against the police as well as expose the racially skewed Criminal Justice System. Research then heavily focused on the prison populations and how the racial bias shown in the officers in 1991 was a product of the Criminal Justice system which disproportionally victimised those of colour. This is a direct link to slavery and how those of colour were automatically seen as criminals and ‘trouble’. This automatic link to criminality continues today and as Marc Maver articulates, black men are born with a social stigma equivalent to a felony conviction.

Once you look at the prison statistics the evidence is clear, there is an estimated 2.2 million people behind bars with blacks making up 46 percent of that population. In 2001, 18.6 percent of blacks were expected to go to prison with 32.2 percent serving time at least once. Once in prison and after, the term ‘felon’ especially for blacks carried the life sentence of legalised discrimination. In nearly all the ways it was once legal to discriminate against African Americans in slavery, a felon is subject to the same injustices. These felons become part of a growing under-caste that is found through the analysis of ‘the new racism’ and part of the Critical Race Theory. This theory believed that White Supremacy was maintained over time and law plays a role in this, it also believe that racial emancipation and anti-subordination should be a mass movement in order to change the systems. Even Black Marxist Wallerstein believed racism was institutionalised since the establishment of capitalism, but Robinson argues that racism was a product of history that has always been around. Once black civilians are locked up they are then locked out of mainstream society forcing them into menial jobs and into areas were gangs, crime and drugs are commonplace only to create cycles of oppression and resistive subcultures similar to those found in groups within slave plantations. In todays terms, mass incarceration is, metaphorically, the New Jim Crow. The nightmare of slavery continues to haunt us even today, through different institutions placing blacks in an interior role and ultimately seeing the colour of their skin as an indicator of their actions rather than actions themselves.

Even today, these two institutions show a complete difference in the way races are treated and this can be seen stemming from the enslavement of Africans. The educational system does discriminate against non-english speakers and those who do not have western ties in their histories. Many black histories especially are forgotten or told from a western standpoint according to Black Marxism which maintains inferiority. The Jena Six incident shows how schools can be racist due to a learned ignorance and punish differently according to colour. The fact the white students got away with a ‘prank’ but the retaliation landed black students with felony charges that shows this differing approach. The educational failings often then tie into police-relations and the high possibility of prison. Rodney King being unfairly targeted for his skin colour and then beaten on the side of the road showed how unforgiving the police can be. History has not passed by as far as we believe it has - the stagnation of many blacks and the stereotypes associated with their colour means that they are unfairly disadvantaged and this racism stopped social progress entirely according to Black Liberalists. One must ask is freedom really being achieved or is it constrained emancipation?

Bibliography

Ahlualia, Pal, and Miller, Toby, ‘We are here because you were there’, Social Identities, Vol 21/6 (2015), p527-528

Alexander, Michelle, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (The New Press; New York, 2010)

Berman, Bruce J, ‘Clientelism and Neocolonialism: Centre-periphery relations and political development in African states’, Studies in Comparative International Development, Vol 9/2 (1974), p3-25

Cascani, Dominic, ‘The legacy of Slavery’ BBC News, 20th March 2007 <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6456765.stm> [accessed 29th March 2018]

Chapman, C, Trends in High School Dropout and Completion rates in the United States: 1972-2008 Compendium Report, 2010 <http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2011/2011012.pdf> [accessed 3rd April 2018]

Davis, Angela Y, The meaning of freedom (City Lights Books; San Francisco, 2012)

Fanon, Frantz, The Wretched of the Earth (Penguin Books Ltd; London, 1967)

Hall, Catherine, ‘The racist ideas of slave owners are still with us today’, The Guardian, 26th Sept 2016 <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/26/racist-ideas-slavery-slave-owners-hate-crime-brexit-vote> [accessed 3rd April 2018]

MacNeill, Tim, ‘Development as Imperialism: Power and the Perpetuation of Poverty in Afro-Indigenous Communities of Coastal Honduras’, Humanity & Society, Vol 41/2 (2017), p209-239

Mulinge, Munyae M, and Lesetedi, Gwen N, ‘Interrogating Our Past: Colonialism and Corruption in Sub-Saharan Africa’, African Journal of Political Science, Vol 3/2 (1998), p15-28

Murji, Karim, and Solomos, John, Theories of Race and Ethnicity, Contemporary Debates and

Perspectives (Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, 2015)

Ramdin, Ron, The making of the black working class in Britain (Gower Publishing Ltd, Aldershot, 1987)

Robinson, Cedric J, Black Marxism, the making of the Black radical tradition (University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill, 2000)

‘Rodney King Biography’, 2018, <https://www.biography.com/people/rodney-king-9542141> [accessed 5th April 2018]

Russell Brown, Katheryn, The Colour of Crime Second Edition (New York University Press; New York, 2009)

Salih, M.A.R. Mohamed, and Markalis, John, Ethnicity and the state in Eastern Africa (Nordiska Afrikainstitutet; Uppsala, 1998)

‘Legacies’, 2011, <http://www.understandingslavery.com/index.php-option=com_content&view=article&id=313&Itemid=225.html> [accessed 29th March 2018]

0 notes

Note

Would you like to provide some links or examples as to how police favor white supremacists over black rights activists? No pressure to respond, of course, but if you do choose to, I'm not asking for anything exhaustive. Maybe a keyword or event or two so I can research it myself. Thanks.

Ha, this is not the ask I was expecting to get about that post!

Hm.

It’s possible that this article from the Atlantic about gun control has some relevant information, but it’s not comprehensive.

So here’s a summary of what I was referencing instead. When slavery was common in the South, there were gangs of white men who would search for runaway slaves and in general police black behavior. According to some sources, modern police forces are a direct descendant of these gangs.

After the Civil War, former plantation owners and so on tried to reestablish their power. Part of the way they did this was through arresting lots of innocent black people; slavery was - and is - still legal as long as the slaves were criminals. The police didn’t function as protectors or as enforcers of the law, but instead as the implements of white supremacy.

All of this was accompanied by racist policies whereby insurance companies would devalue districts where black or other nonwhite people lived, resulting in white flight and creating ghettoes. Also, job discrimination created poverty; government welfare programs after wars and in the New Deal weren’t applied equally to whites and blacks, so that the form of welfare that blacks got ended up being more stigmatized. (For example, WWII veteran benefits included a Nice Picket Fence in Suburbia. Black people did not get that benefit.)

Skip ahead a few years the criminalization of blackness (and other minorities) continues to be a Major Problem. The police consistently act as enforcers of e.g. segregation laws. The criminal “justice” system consistently fucks over black people and forgives white supremacists, like the murderers of Emmett Till. (A little known fact is that Emmett Till had had polio, which left him with a consistent stutter. He was taught to whistle so that it was easier for him to speak. The incident that lead to his death was him whistling at a white woman. This is kind of far out there but it seems as though there’s a natural connection between these two facts.)

(Police also served as enforcers of gender normativity- there were laws that women had to be wearing three articles of men’s clothing at a time, and vice versa; also, gay sex was sometimes criminalized. The police would arrest and rape queer people routinely. This is depicted in Stone Butch Blues very disturbingly and it is also probably relevant to this Amnesty International article, “Brutality in Blue”. It’s part of what caused the Stonewall Riots.

In addition to this, the police would ignore crimes committed against queer people, turning a blind eye to queers being assaulted or raped. This is called selective enforcement and it is Very Bad.

This all means that black trans women are (likely) at a higher risk of having bad stuff happen to them; for an example, see the CeCe McDonald case.)

At some point the school-to-prison pipeline became a thing as well. The policing of black people was also extended to Latinos.

It only gets worse with the War on Drugs, wherein President Nixon deliberately and explicitly decided to criminalize crack in order to hurt black people (and marijuana in order to hurt the anti-Vietnam counterculture). A particularly notorious example of the criminalization of [stuff black people do] is the massive disparity in crack versus powder cocaine sentencing. Crack is something poor black people tended (tend?) to use more; powder is something rich white people tend(ed) to use. So of course…

…people faced longer sentences for offenses involving crack cocaine than for offenses involving the same amount of powder cocaine – two forms of the same drug. Most disturbingly, because the majority of people arrested for crack offenses are African American, the 100:1 ratio resulted in vast racial disparities in the average length of sentences for comparable offenses. On average, under the 100:1 regime, African Americans served virtually as much time in prison for non-violent drug offenses as whites did for violent offenses.

The disparity has since been reduced to a mere 18:1 ratio. Racial equality, eh?

This is a good time to mention that a good deal of Republican presidents, including Nixon and Our Good Friend Ronald Reagan, tried to pander to the South by being utter racists. They would deliberately say things like “welfare queens” or “thugs” or “law and order” or “states’ rights”, and the South would know that they really meant to say “fuck those uppity n-words, amirite?”. This was called the Southern Strategy. Internal records show that Nixon knew exactly what he was doing and that he was deliberately doing it; he summarizes his strategy in basically the same way I am.

At some point a narrative of black criminality started being common. Black people and black men especially were seen as threatening, thugs, brutes, less than human. They were threats to the beauty of the white women (as in Emmett Till’s case). This has also been applied to various other minorities (see: Donald Trump on Mexicans).

Unfortunately - somewhat similarly to their treatment of queers - , police are very bad at actually doing stuff about real crimes committed against black people- ie, the much vaunted black-on-black crime problem, which some people use to derail conversations about police brutality and abuses. The underpolicing of minority neighborhoods is actually an outgrowth of racism as well.

Partially due to a fear of blacks, and partially due to a neurotic fear of Communism, during the 70s or around that time, the FBI started keeping information on a lot of black activists, including the (radical! socialist!) Martin Luther King Jr. They assassinated or otherwise eliminated a lot of the black leadership. Here is a very emotional letter from James Baldwin to Angela Davis about her arrest, which is probably somewhat relevant. (Content warning for comparisons to the Holocaust.)

The media did not care about dead black people. The media did care when white college students, down in the South for Freedom Summer, started getting killed, by police forces. The involvement of white students, of course, was orchestrated by nonviolent black activists like King.

Another remarkable thing that King did was that he made going to prison a mark of prestige, rather than shame. This is really cool just on its own, but it’s even more clever when one considers the context.

Everyone knows about Martin Luther King Jr. Not everyone knows why he was so admirable, or so successful. Through nonviolence, he made clear what had been true for centuries- that the white supremacists were the initiators of violence and the breakers of peace. He actively worked against notions of black people as brutes or criminals.

Black Lives Matter and the Ferguson… thing… are reactions to hundreds of years of racist police enforcement and brutality. Conservative Republican reactions are, by and large, abysmal: whenever another black child gets murdered by the police people always try to justify it, claiming that the kid is Just A Thug. He stole cigarettes! He had his hand in his pocket. He was wearing a hoodie. He was so big and threatening. We had to tackle her to the ground because we were Just Scared. He was rude so we put him in a chokehold and ignored him saying he couldn’t breathe! They were just thugs.

As if these make someone less of a victim, or less worthy of care. As if this makes police officers less responsible for what they’ve done.

(Note that I’m not making specific claims about specific incidents- just, taken as a whole, it’s Very Very Damning.)

As a whole, the police force functions as an instrument of white supremacy. This is a disgusting perversion of the Lockean social contract and the rule of law.

And I don’t know how to solve it.

#transsexualism#Anonymous#asks#antiblack racism cw#transphobia cw#homophobia cw#oppositional sexism cw#rape cw#police brutality cw#assault cw#violence cw#stereotypes cw#white supremacy cw#transmisogyny cw#guns cw#slavery cw#you know what if you need a cw you should probably assume it's in here#misandry cw#misandrynoir cw#(that's not a word but I'm going to pretend it is)#prison cw#death cw

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

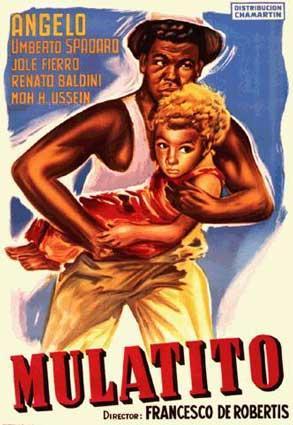

The Tragic Mulatto Myth

Lydia Maria Child introduced the literary character that we call the tragic mulatto1 in two short stories: "The Quadroons" (1842) and "Slavery's Pleasant Homes" (1843). She portrayed this light skinned woman as the offspring of a white slaveholder and his black female slave. This mulatto's life was indeed tragic. She was ignorant of both her mother's race and her own. She believed herself to be white and free. Her heart was pure, her manners impeccable, her language polished, and her face beautiful. Her father died; her "negro blood" discovered, she was remanded to slavery, deserted by her white lover, and died a victim of slavery and white male violence. A similar portrayal of the near-white mulatto appeared in Clotel (1853), a novel written by black abolitionist William Wells Brown.

A century later literary and cinematic portrayals of the tragic mulatto emphasized her personal pathologies: self-hatred, depression, alcoholism, sexual perversion, and suicide attempts being the most common. If light enough to "pass" as white, she did, but passing led to deeper self-loathing. She pitied or despised blacks and the "blackness" in herself; she hated or feared whites yet desperately sought their approval. In a race-based society, the tragic mulatto found peace only in death. She evoked pity or scorn, not sympathy. Sterling Brown summarized the treatment of the tragic mulatto by white writers:

White writers insist upon the mulatto's unhappiness for other reasons. To them he is the anguished victim of divided inheritance. Mathematically they work it out that his intellectual strivings and self-control come from his white blood, and his emotional urgings, indolence and potential savagery come from his Negro blood. Their favorite character, the octoroon, wretched because of the "single drop of midnight in her veins," desires a white lover above all else, and must therefore go down to a tragic end.(Brown, 1969, p. 145)

Vara Caspary's novel The White Girl (1929) told the story of Solaria, a beautiful mulatto who passes for white. Her secret is revealed by the appearance of her brown-skinned brother. Depressed, and believing that her skin is becoming darker, Solaria drinks poison. A more realistic but equally depressing mulatto character is found in Geoffrey Barnes' novel Dark Lustre (1932). Alpine, the light-skinned "heroine," dies in childbirth, but her white baby lives to continue "a cycle of pain." Both Solaria and Alpine are repulsed by blacks, especially black suitors.

Most tragic mulattoes were women, although the self-loathing Sergeant Waters in A Soldier's Story (Jewison, 1984) clearly fits the tragic mulatto stereotype. The troubled mulatto is portrayed as a selfish woman who will give up all, including her black family, in order to live as a white person. These words are illustrative:

Don't come for me. If you see me in the street, don't speak to me. From this moment on I'm White. I am not colored. You have to give me up.

These words were spoken by Peola, a tortured, self-hating black girl in the movie Imitation of Life (Laemmle & Stahl, 1934). Peola, played adeptly by Fredi Washington, had skin that looked white. But she was not socially white. She was a mulatto. Peola was tired of being treated as a second-class citizen; tired, that is, of being treated like a 1930s black American. She passed for white and begged her mother to understand.

Imitation of Life, based on Fannie Hurst's best selling novel, traces the lives of two widows, one white and the employer, the other black and the servant. Each woman has one daughter. The white woman, Beatrice Pullman (played by Claudette Colbert), hires the black woman, Delilah, (played by Louise Beavers) as a live-in cook and housekeeper. It is the depression, and the two women and their daughters live in poverty -- even a financially struggling white woman can afford a mammy. Their economic salvation comes when Delilah shares a secret pancake recipe with her boss. Beatrice opens a restaurant, markets the recipe, and soon becomes wealthy. She offers Delilah, the restaurant's cook, a twenty percent share of the profits. Regarding the recipe, Delilah, a true cinematic mammy, delivers two of the most pathetic lines ever from a black character: "I gives it to you, honey. I makes you a present of it." While Delilah is keeping her mistress's family intact, her relationship with Peola, her daughter, disintegrates.

Peola is the antithesis of the mammy caricature. Delilah knows her place in the Jim Crow hierarchy: the bottom rung. Hers is an accommodating resignation, bordering on contentment. Peola hates her life, wants more, wants to live as a white person, to have the opportunities that whites enjoy. Delilah hopes that her daughter will accept her racial heritage. "He [God] made you black, honey. Don't be telling Him his business. Accept it, honey." Peola wants to be loved by a white man, to marry a white man. She is beautiful, sensual, a potential wife to any white man who does not know her secret. Peola wants to live without the stigma of being black -- and in the 1930s that stigma was real and measurable. Ultimately and inevitably, Peola rejects her mother, runs away, and passes for white. Delilah dies of a broken heart. A repentant and tearful Peola returns to her mother's funeral.

Audiences, black and white (and they were separate), hated what Peola did to her mother -- and they hated Peola. She is often portrayed as the epitome of selfishness. In many academic discussions about tragic mulattoes the name Peola is included. From the mid-1930s through the late 1970s, Peola was an epithet used by blacks against light-skinned black women who identified with mainstream white society. A Peola looked white and wanted to be white. During the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement, the name Peola was an insult comparable to Uncle Tom, albeit a light-skinned female version.

Fredi Washington, the black actress who played Peola, was light enough to pass for white. Rumor has it that in later movies makeup was used to "blacken" her skin so white audiences would know her race. She had sharply defined features; long, dark, and straight hair, and green eyes; this limited the roles she was offered. She could not play mammy roles, and though she looked white, no acknowledged black was allowed to play a white person from the 1930's through the 1950's.

Imitation of Life was remade in 1959 (Hunter & Sirk). The plot is essentially the same; however, Peola is called Sara Jane, and she is played by Susan Kohner, a white actress. Delilah is now Annie Johnson. The pancake storyline is gone. Instead, the white mistress is a struggling actress. The crux of the story remains the light-skinned girl's attempts to pass for white. She runs away and becomes a chorus girl in a sleazy nightclub. Her dark skinned mother (played by Juanita Moore) follows her. She begs her mother to leave her alone. Sara Jane does not want to marry a "colored chauffeur"; she wants a white boyfriend. She gets a white boyfriend, but, when he discovers her secret, he savagely beats her and leaves her in a gutter. As in the original, Sara Jane's mother dies from a broken heart, and the repentant child tearfully returns to the funeral.

Peola and Sara Jane were cinematic tragic mulattoes. They were big screen testaments to the commonly held belief that "mixed blood" brought sorrow. If only they did not have a "drop of Negro blood." Many audience members nodded agreement when Annie Johnson asked rhetorically, "How do you explain to your daughter that she was born to hurt?"

Were real mulattoes born to hurt? All racial minorities in the United States have been victimized by the dominant group, although the expressions of that oppression vary. Mulattoes were considered black; therefore, they were slaves along with their darker kinsmen. All slaves were "born to hurt," but some writers have argued that mulattoes were privileged, relative to dark-skinned blacks. E.B. Reuter (1919), a historian, wrote:

In slavery days, they were most frequently the trained servants and had the advantages of daily contact with cultured men and women. Many of them were free and so enjoyed whatever advantages went with that superior status. They were considered by the white people to be superior in intelligence to the black Negroes, and came to take great pride in the fact of their white blood....When possible, they formed a sort of mixed-blood caste and held themselves aloof from the black Negroes and the slaves of lower status. (p. 378)

Reuter's claim that mulattoes were held in higher regard and treated better than "pure blacks" must be examined closely. American slavery lasted for more than two centuries; therefore, it is difficult to generalize about the institution. The interactions between slaveholder and slaves varied across decades--and from plantation to plantation. Nevertheless, there are clues regarding the status of mulattoes. In a variety of public statements and laws, the offspring of white-black sexual relations were referred to as "mongrels" or "spurious" (Nash, 1974, p. 287). Also, these interracial children were always legally defined as pure blacks, which was different from how they were handled in other New World countries. A slaveholder claimed that there was "not an old plantation in which the grandchildren of the owner [therefore mulattos] are not whipped in the field by his overseer" (Furnas, 1956, p. 142). Further, it seems that mulatto women were sometimes targeted for sexual abuse.

According to the historian J. C. Furnas (1956), in some slave markets, mulattoes and quadroons brought higher prices, because of their use as sexual objects (p. 149). Some slavers found dark skin vulgar and repulsive. The mulatto approximated the white ideal of female attractiveness. All slave women (and men and children) were vulnerable to being raped, but the mulatto afforded the slave owner the opportunity to rape, with impunity, a woman who was physically white (or near-white) but legally black. A greater likelihood of being raped is certainly not an indication of favored status.

The mulatto woman was depicted as a seductress whose beauty drove white men to rape her. This is an obvious and flawed attempt to reconcile the prohibitions against miscegenation (interracial sexual relations) with the reality that whites routinely used blacks as sexual objects. One slaver noted, "There is not a likely looking girl in this State that is not the concubine of a White man..." (Furnas, 1956, p. 142). Every mulatto was proof that the color line had been crossed. In this regard, mulattoes were symbols of rape and concubinage. Gary B. Nash (1974) summarized the slavery-era relationship between the rape of black women, the handling of mulattoes, and white dominance:

Though skin color came to assume importance through generations of association with slavery, white colonists developed few qualms about intimate contact with black women. But raising the social status of those who labored at the bottom of society and who were defined as abysmally inferior was a matter of serious concern. It was resolved by insuring that the mulatto would not occupy a position midway between white and black. Any black blood classified a person as black; and to be black was to be a slave.... By prohibiting racial intermarriage, winking at interracial sex, and defining all mixed offspring as black, white society found the ideal answer to its labor needs, its extracurricular and inadmissible sexual desires, its compulsion to maintain its culture purebred, and the problem of maintaining, at least in theory, absolute social control. (pp. 289-290)

George M. Fredrickson (1971), author of The Black Image in the White Mind, claimed that many white Americans believed that mulattoes were a degenerate race because they had "White blood" which made them ambitious and power hungry combined with "Black blood" which made them animalistic and savage. The attributing of personality and morality traits to "blood" seems foolish today, but it was taken seriously in the past. Charles Carroll, author of The Negro a Beast (1900), described blacks as apelike. Regarding mulattoes, the offspring of "unnatural relationships," they did not have "the right to live," because, Carroll said, they were the majority of rapists and killers (Fredrickson, 1971, p. 277). His claim was untrue but widely believed. In 1899 a southern white woman, L. H. Harris, wrote to the editor of the Independent that the "negro brute" who rapes white women was "nearly always a mulatto," with "enough white blood in him to replace native humility and cowardice with Caucasian audacity" (Fredrickson, 1971, p. 277). Mulatto women were depicted as emotionally troubled seducers and mulatto men as power hungry criminals. Nowhere are these depictions more evident than in D. W. Griffith's film The Birth of a Nation (1915).

The Birth of a Nation is arguably the most racist mainstream movie produced in the United States. This melodrama of the Civil War and Reconstruction justified and glorified the Ku Klux Klan. Indeed, the Klan of the 1920s owes its existence to William Joseph Simmons, an itinerant Methodist preacher who watched the film a dozen times, then felt divinely inspired to resurrect the Klan which had been dormant since 1871. D. W. Griffith based the film on Thomas Dixon's anti-black novel The Clansman (1905) (also the original title of the movie). Griffith, following Dixon's lead, depicted his black characters as either "loyal darkies" or brutes and beasts lusting for power and, worse yet, lusting for white women.

The Birth of a Nation tells the story of two families, the Stonemans of Pennsylvania, and the Camerons of South Carolina. The Stonemans, headed by politician Austin Stoneman, and the Camerons, headed by slaveholder "Little Colonel" Ben Cameron, have their longtime friendship divided by the Civil War. The Civil War exacts a terrible toll on both families: both have sons die in the war. The Camerons, like many slaveholders, suffer "ruin, devastation, rapine, and pillage." The Birth of a Nation depicts Radical Reconstruction as a time when blacks dominate and oppress whites. The film shows blacks pushing whites off sidewalks, snatching the possessions of whites, attempting to rape a white teenager, and killing blacks who are loyal to whites (Leab, 1976, p. 28). Stoneman, a carpetbagger, moves his family to the South. He falls under the influence of Lydia, his mulatto housekeeper and mistress.

Austin Stoneman is portrayed as a naive politician who betrays his people: whites. Lydia, his lover, is described in a subtitle as the "weakness that is to blight a nation." Stoneman sends another mulatto, Silas Lynch, to "aid the carpetbaggers in organizing and wielding the power of the vote." Lynch, owing to his "white blood," becomes ambitious. He and his agents rile the local blacks. They attack whites and pillage. Lynch becomes lieutenant governor, and his black co-conspirators are voted into statewide political offices. The Birth of a Nation shows black legislators debating a bill to legalize interracial marriage -- their legs propped on tables, eating chicken, and drinking whiskey.

Silas Lynch proposes marriage to Stoneman's daughter, Elsie. He says, "I will build a black empire and you as my queen shall rule by my side." When she refuses, he binds her and decides on a "forced marriage." Lynch informs Stoneman that he wants to marry a white woman. Stoneman approves until he discovers that the white woman is his daughter. While this drama unfolds, blacks attack whites. It looks hopeless until the newly formed Ku Klux Klan arrives to reestablish white rule.

The Birth of a Nation set the standard for cinematic technical innovation -- the imaginative use of cross-cutting, lighting, editing, and close-ups. It also set the standard for cinematic anti-black images. All of the major black caricatures are in the movie, including, mammies, sambos, toms, picaninnies, coons, beasts, and tragic mulattoes. The depictions of Lydia -- a cold-hearted, hateful seductress -- and Silas Lynch -- a power hungry, sex-obsessed criminal -- were early examples of the pathologies supposedly inherent in the tragic mulatto stereotype.

Mulattoes did not fare better in other books and movies, especially those who passed for white. In Nella Larsen's novel Passing (1929), Clare, a mulatto passing for white, frequently is drawn to blacks in Harlem. Her bigoted white husband finds her there. Her problems are solved when she falls to her death from a sixth story window. In the movie Show Boat(Laemmle & Whale, 1936), a beautiful young entertainer, Julie, discovers that she has "Negro blood." Existing laws held that "one drop of Negro blood makes you a Negro." Her husband (and the movie's writers and producer) take this "one drop rule" literally. The husband cuts her hand with a knife and sucks her blood. This supposedly makes him a Negro. Afterward Julie and her newly-mulattoed husband walk hand-in-hand. Nevertheless, she is a screen mulatto, so the movie ends with this one-time cheerful "white" woman, now a Negro alcoholic.

Lost Boundaries is a book by William L. White (1948), made into a movie in 1949 (de Rochemont & Werker). It tells the story of a troubled mulatto couple, the Johnsons. The husband is a physician, but he cannot get a job in a southern black hospital because he "looks white," and no southern white hospital will hire him. The Johnsons move to New England and pass for white. They become pillars of their local community -- all the while terrified of being discredited. Years later, when their secret is discovered, the townspeople turn against them. The town's white minister delivers a sermon on racial tolerance which leads the locals, shamefaced and guilt-ridden, to befriend again the mulatto couple. Lost Boundaries, despite the white minister's sermon, blames the mulatto couple, not a racist culture, for the discrimination and personal conflicts faced by the Johnsons.

In 1958 Natalie Wood starred in Kings Go Forth (Ross & Daves), the story of a young French mulatto who passes for white. She becomes involved with two American soldiers on leave from World War II. They are both infatuated with her until they discover that her father is black. Both men desert her. She attempts suicide unsuccessfully. Given another chance to live, she turns her family's large home into a hostel for war orphans, "those just as deprived of love as herself" (Bogle, 1994, p. 192). At the movie's end, one of the soldiers is dead; the other, missing an arm, returns to the mulatto woman. They are comparable, both damaged, and it is implied that they will marry.

The mulatto women portrayed in Show Boat, Lost Boundaries, and Kings Go Forthwere portrayed by white actresses. It was a common practice. Producers felt that white audiences would feel sympathy for a tortured white woman, even if she was portraying a mulatto character. The audience knew she was really white. In Pinky(Zanuck & Kazan, 1949), Jeanne Crain, a well-known actress, played the role of the troubled mulatto. Her dark-skinned grandmother was played by Ethel Waters. When audiences saw Ethel Waters doing menial labor, it was consistent with their understanding of a mammy's life, but when Jeanne Crain was shown washing other people's clothes audiences cried.

Even black filmmakers like Oscar Micheaux made movies with tragic mulattoes. Within Our Gates (Micheaux, 1920) tells the story of a mulatto woman who is hit by a car, menaced by a con man, nearly raped by a white man, and witnesses the lynching of her entire family. God's Step Children (Micheaux, 1938) tells the story of Naomi, a mulatto who leaves her black husband and child and passes for white. Later, consumed by guilt, she commits suicide. Mulatto actresses played these roles.

Fredi Washington, the star of Imitation of Life, was one of the first cinematic tragic mulattoes. She was followed by women like Dorothy Dandridge and Nina Mae McKinney. Dandridge deserves special attention because she not only portrayed doomed, unfulfilled women, but she was the embodiment of the tragic mulatto in real life. Her role as the lead character in Carmen Jones (Preminger, 1954) helped make her a star. She was the first black featured on the cover of Life magazine. In Island in the Sun (Zanuck & Rossen, 1957) she was the first black woman to be held -- lovingly -- in the arms of a white man in an American movie. She was a beautiful and talented actress, but Hollywood was not ready for a black leading lady; the only roles offered to her were variants of the tragic mulatto theme. Her personal life was filled with failed relationships. Disillusioned by roles that limited her to exotic, self-destructive mulatto types, she went to Europe, where she fared worse. She died in 1965, at the age of forty-two, from an overdose of anti-depressants.

Today's successful mulatto actresses -- for example, Halle Berry, Lisa Bonet and Jasmine Guy -- owe a debt to the pioneering efforts of Dandridge. These women have great wealth and fame. They are bi-racial, but their statuses and circumstances are not tragic. They are not marginalized; they are mainstream celebrities. Dark-skinned actress -- Whoopi Goldberg, Angela Bassett, Alfre Woodard, and Joie Lee -- have enjoyed comparable success. They, too, benefit from Dandridge's path clearing.

The tragic mulatto was more myth than reality; Dandridge was an exception. The mulatto was made tragic in the minds of whites who reasoned that the greatest tragedy was to be near-white: so close, yet a racial gulf away. The near-white was to be pitied -- and shunned. There were undoubtedly light skinned blacks, male and female, who felt marginalized in this race conscious culture. This was true for many people of color, including dark skinned blacks. Self-hatred and intraracial hatred are not limited to light skinned blacks. There is evidence that all racial minorities in the United States have battled feelings of inferiority and in-group animosity; those are, unfortunately, the costs of being a minority.

The tragic mulatto stereotype claims that mulattoes occupy the margins of two worlds, fitting into neither, accepted by neither. This is not true of real life mulattoes. Historically, mulattoes were not only accepted into the black community, but were often its leaders and spokespersons, both nationally and at neighborhood levels. Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. DuBois, Booker T. Washington, Elizabeth Ross Haynes,2 Mary Church Terrell,3 Thurgood Marshall, Malcolm X, and Louis Farrakhan were all mulattoes. Walter White, the former head of the NAACP, and Adam Clayton Powell, an outspoken Congressman, were both light enough to pass for white. Other notable mulattoes include Langston Hughes, Billie Holiday, and Jean Toomer, author of Cane (1923), and the grandson of mulatto Reconstruction politician P.B.S. Pinchback.

There was tragedy in the lives of light skinned black women -- there was also tragedy in the lives of most dark skinned black women -- and men and children. The tragedy was not that they were black, or had a drop of "Negro blood," although whites saw that as a tragedy. Rather, the real tragedy was the way race was used to limit the chances of people of color. The 21st century finds an America increasingly more tolerant of interracial unions and the resulting offspring.

© Dr. David Pilgrim, Professor of Sociology

Ferris State University

Nov., 2000

Edited 2012

1 A mulatto is defined as: the first general offspring of a black and white parent; or, an individual with both white and black ancestors. Generally, mulattoes are light-skinned, though dark enough to be excluded from the white race.

2 Elizabeth Ross Haynes was a social worker, sociologist, and a pioneer in the YWCA movement.

3 Mary Church Terrell was a feminist, civil rights activist, and the first president of the National Association of Colored Women.

Also See: Tragic Mulatto Stereotype Image Gallery

#tragic mulatto#stereotypes#racial myths#Dr. David Pilgrim#Jim Crow#history#slavery#race#racism#sociology#Lydia Maria Child#William Wells Brown#Vara Caspary#Geoffrey Barnes#Fredi Washington#Fannie Hurst#Claudette Colbert#Louise Beavers#Juanita Moore#Susan Kohner#E.B. Reuter#J. C. Furnas#Gary B. Nash#George M. Fredrickson#Charles Carroll#D. W. Griffith#Thomas Dixon#William L. White#Mary Church Terrell#Natalie Wood

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i wrote a not very good essay a while ago about connections between William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom and Chuck Palahniuk’s Rant (specifically about the relationship between Faulkner’s alleged anti-Eurocentric style of retelling colonial histories versus the splintered time theory of Rant) and found it today and thought i’d throw it into the void, here goes~

A Man Who Wanted A Son:

Faulknerian Techniques in Palahniuk’s Rant

Absalom, Absalom is widely considered one of William Faulkner’s most difficult novels to comprehend and enjoy. It is a dramatic and ambitious work, and its plot spans nearly a century. It is not unlikely that this novel and its companion, The Sound and the Fury, were primarily responsible for Faulkner’s Nobel Prize win in 1949. In Absalom, the story of one of Faulkner’s most enduring protagonists is told: Thomas Sutpen, the obsessed, incestuous, murderous patriarch of a doomed dynasty.

One of the vital characteristics that sets Absalom apart from most novels with clear main characters, and even from Faulkner’s other novels, is that Sutpen doesn’t do the telling: his past is relayed by a series of characters, most of whom heard their information secondhand. It’s a difficult and complex storytelling technique, and Faulkner certainly doesn’t make figuring it out easy for the reader, but knowing the absolute truth about the events in the novel isn’t really the point. As Richard P. Adams writes in Faulkner: Myth and Motion: “In the text, the question of ‘truth,’ in any sense of historical accuracy, is hardly relevant. The issue is not what is true about Sutpen but what it is like to live in the South.” (183)

Sutpen’s goal, and his eventual downfall, is his obsession with conceiving an heir who would live up to his own self-imagined legacy. During an interview at the University of Virginia in 1957, when Faulkner was asked by an unnamed audience member whether the central character in Absalom, Absalom was actually Thomas Sutpen, he responded: “The central character is Sutpen, yes. The story of a man who wanted a son and got too many, got so many that they destroyed him. It's incidentally the story of—of Quentin Compson's hatred of the—the bad qualities in the country he loves. But the central character is Sutpen, the story of a man who wanted sons.” (Faulkner at Virginia)

Comparing any author to Faulkner tends to elicit impassioned responses, which is fine, because Chuck Palahniuk and Faulkner don’t have very much in common anyway. Faulkner was an undisputed master of prose who won multiple Pulitzer Prizes, and is continually considered one of the greatest American novelists and essayists of all time, whereas Palahniuk is mostly known for his 1996 novel Fight Club, which features a scene in which a man steals human fat from a liposuction clinic dumpster in order to make soap. Despite occasional tastelessness, Fight Club is a widely-known and relatively respected novel—at least compared to Rant, which Palahniuk published 11 years later to significantly lesser acclaim.

Rant was kind of unprecedented, even to Palahniuk’s cult followers. The novel presents itself as an “oral biography:” a compilation of interviews with friends and acquaintances of Buster “Rant” Casey, our protagonist, concerning his childhood, activities as a young adult, and the events leading up to his suicide in a fiery crash. (Henceforth, he’ll be referred to as “Buster” to reduce confusion with the title of the novel.) The story takes place in two locations: Middleton, Buster’s fictional Southern hometown, and the unnamed city Buster moves to in order to realize his goal of becoming a sort of patient zero for rabies.

Rant takes place in a science-fictional America in which society has been crippled by a voyeuristic form of entertainment known as “boosting peaks,” which is best described as a sort of mental virtual-reality lens that allows users to jack into others’ experiences and view them firsthand, complete with all the sensory stimuli. Only someone with a surgically installed ports can boost, and a port can be deactivated by something like a traumatic injury or brain inflammation. Buster’s actual objective in spreading rabies throughout the populace is to disable as many people’s ports as possible, and free society to live in the physical realm, rather than basking in self-induced mental dissociation. Admittedly, it’s a bit of a heavy-handed metaphor.

Although the harmful detachment to the real world caused by the ubiquitousness of technology is the most obvious “message” of Rant, there’s an even more intricate subplot that is revealed late in the novel: it is discovered that by crashing a car just the right way, an individual with rabies can travel through time. Most of the narrators don’t fully understand how it works, but one character who calls himself Green Taylor Simms claims to have done it himself. As Buster’s father describes it, Simms visited Buster and explained that one could achieve immense power and even immortality by going back in time and impregnating their female ancestors. The purity of the bloodline would turn the traveler into some sort of superhuman, according to Simms.