#export top china

Text

India Spices Exports – China is Top Export Destination for Indian Spices

India Spices Exports – China is Top Export Destination for Indian Spices

India is known as the birthplace of spices because it has a long history of trading with the ancient civilizations of Rome and China. Today Indian spices are in the greatest demand in the world for their texture, taste, aroma, and medicinal properties. 109 spices are listed by the International Organization for Standardization and exported all over the world

This is why Indian spices are in high demand all over the world, and countries like China import a lot of Indian spices.

India mainly exports pepper, chili, ginger, turmeric, coriander, ginger, cumin, cumin, and tamarind, as well as processed spices such as curry powder, mint powder, oil, spices, and resins. The main markets for Indian spices are China, the USA, Vietnam, Thailand, Bangladesh, United Arab Emirates, the UK, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and Germany.

Most of the spices are exported from India

Spices The export of products from India has increased over the years. Indian spices are not only known for their unique aroma and flavour, but they also have many health and medical uses. Many spices are exported from India such as chili, cumin, turmeric, cardamom, ginger, etc. These are some of the main spices exported from India.

● Chilli

India is one of the largest consumers, producers, and exporters of chili peppers in the world. Chile is grown in various states of India including Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka. Chile is one of the most exported spices in India. Chile's exports in 2018-2019 reached 468,500 tons.

● Cumin

Dill seeds are used in various cuisines around the world for their wonderful aroma. Apart from its culinary uses, cumin is also considered to be beneficial to health and fitness, it is one of the most important ingredients in Indian cuisine, with caraway exports of 180,300 tons and turmeric 180,300 tons. - 133 600 tons.

● Turmeric

India is one of the world's largest exporters of turmeric. Various types of turmeric are exported to different countries around the world, including Brazil, Germany, Malaysia, and others. Turmeric is useful in many industries, including cooking and cosmetics. India's annual cardamom production is around 22,000-24,000 tons, while India's cardamom exports in 201819 were around 860 tons.

● Ginger

Ginger is very popular in various cuisines around the world for its unique taste. As one of the most important spices in India, India is the world's largest producer of ginger. Other ginger-producing countries include China, Nepal, and Indonesia. It has a pungent odour and a pungent taste. Pepper is one of the most widely used spices in the world. Pepper exports from India increased by 21% to 8,200 tons in 2019-2020.

● Nutmeg

Nutmeg is another spice that is exported to many countries around the world. Nutmeg is the seed of several species of the genus Myristica that can also be used as a chopped spice. Nutmeg has many benefits and uses. India exports cinnamon to many countries around the world, including the USA, Canada, Australia, the UK, and New Zealand.

India's Spice Exports to China

China has become the number one export destination for Indian spices. Due to the pandemic and supply chain restrictions, India's spice imports from China increased in 2020 and reached $ 581.2 million in the same year.

Indian Spice Exports to China in 2021

China loves hot peppers from India as it imported about 1.4 million tonnes of chili peppers from India in FY20 out of 10,000 tonnes. varieties such as Teja, Sannam, and Bydagi, which are only available in India. The chart below shows the number of Indian spices (under 4 HS codes) exported to China in 2021 in dollars.

Spice exports from India to the world during

India is home to cleaner production and exports of Indian spices Spice exports to countries around the world also increased in 2020 despite the Covid19 pandemic. India's spice exports surpassed the $ 2 billion mark last year. ...The chart below shows the global spice exports from India in 2018-2020. In addition to China, consumption of Indian spices is also growing in Africa, South Asia, and Western Asia. India's top 10 spice export partners accounted for 87.2% of total shipments recorded in 2020, according to Indian trade data.

According to the Spices Board India, spice exports continued to grow in fiscal 21 despite the Covid19 pandemic. Exports of spices and condiments are projected for 202021 at 15.65,000 tons, up from 12.08,400 tons in the previous fiscal year. Chile's total exports in 202021 will be 6.01,500 tons, an increase of over 21% in volume. Last year it was 2.64.5 thousand tons. In addition to chili peppers, other spices that have significantly increased export turnover include turmeric, cardamom, ginger, and the seeds of spices such as cumin and fenugreek. Brands in Overseas Markets Let's see how much the Indian spice industry will grow in 2021.

Spice Export Destination

Indian Spices are very popular all over the world. We export spices from India to about 140 countries around the world. Major spice export destinations include the United States, China, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Bangladesh, Thailand, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka. Spices are also exported from India to many other countries. These are the main export markets for spices.

● USA

The USA is one of the largest importers of spices to India. The United States accounted for the highest volume of Indian spice exports in fiscal 2019, with an export value of around INR 37.4 billion.

● China

China is the second-largest importer of spices from India. The value of spices exported to China from India in fiscal 2019 was about Rs 31.38 billion.

● Vietnam

India also exports large quantities of spices to Vietnam annually. The value of spices exported to Vietnam from India in fiscal 2019 is approximately INR 16.93 billion.

● Iran

Indian spices are also exported to Iran. India's spice exports to Iran were valued at INR 12.05 billion in fiscal 2019.

● Thailand

Indian suppliers export large-scale spices to Thailand. The value of spices exported to Thailand from India in fiscal 2019 was about Rs 9.24 billion.

#indian spices#spices#cumin#chilli#cumin export#chilli exporter#cumin seeds supplier#china#export top china#export to usa#export from india#indian spices andmasala

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

In 2021, the People's Republic of China imported goods worth 2.056 trillion dollars from all over the world.

- China's Top Trading PartnersChina exported 2.591 trillion dollars worth of goods around the world in 2020, making it the world's largest exporter by value.

- Here is a list of China's top 15 trading partners in terms of export sales...

0 notes

Text

In the international trade platform, China is going to lose its longevity position as the US’s top #exporter. This is because of the tensions between the two big economies and a vital reconstitution of global supply chains. According to the latest reports, the #US Commerce Department exposes a significant downturn of around 20% in US product imports from China from January to December. For the place of #China, Mexico will be positioned for the US for the whole year. As per reports, US #imports from Mexico were a record in 2023 making around 15% of the total for the first 11 months.

Smartphone imports from China had a remarkable decrease of 10% while having surged imports of fivefold from India. Likewise, laptop imports from China also dropped by 30% but quadrupled from Vietnam. The diversification is aligned with the Friend shoring policy of Biden that emphasizes the significance of preserving supply chains within the allied and partner countries. Biden administration policy has also decided to retain the $370 billion worth of tariffs on China products that were imposed by Donald Trump.

Will Mexico take advantage of the US-China trade war?

Elevated restrictions by the #US on #China will witness a vital shift, with Mexico emerging as a leading beneficiary. Biden’s assertive moves, marked by restrictions and tariffs on critical technology exports from China have created a remarkable decrease in Beijing’s exports to the US. Chinese companies are planning to establish industrial operations in Mexico, which will change the dynamics of #trade in the region.

The shift in position will be reflected in the Chinese strategy to decrease dependence on America for exports. China’s government is working actively to increase the Yuan’s role in #globalpayments, looking for alternatives for the dollar. The government plans transactions with its vital partners like the Middle East, Russia, and South America.

#trade finance#finance#banking#emeriobanque#import#letter of credit#emerio banque#tradefinance#trade finance services#international trade#China#US’s top exporter#Mexico#US imports#trade#export

0 notes

Video

youtube

China Overtakes Japan As World's Top Car Exporter. #news #asia #china #j...

#youtube#China Overtakes Japan As World's Top Car Exporter. news asia china japan ev live germany russia eu europe China says it has become the worl

0 notes

Text

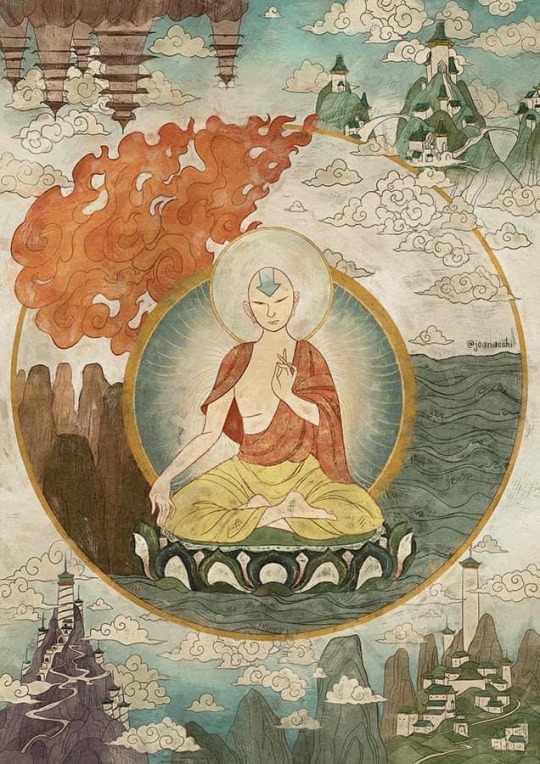

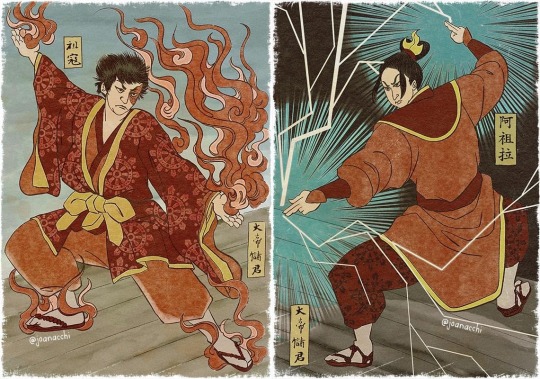

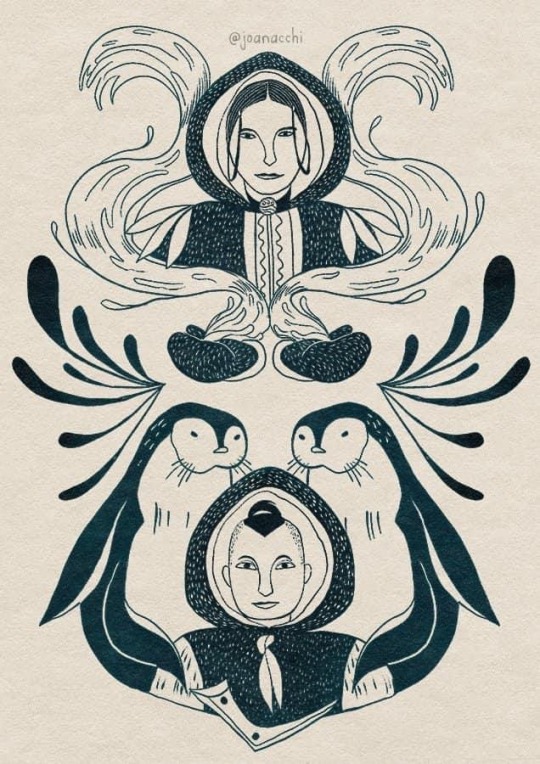

Amazing fanart by Joanacchi! Posted here on tumblr with their blessing. Each one is based on a style that reflects a particular ancient culture's art history. (See below for descriptions provided by the artist!)

Store (buy these prints!) Twitter Instagram

Aang: Tibetan Thangka

"Thangkas are traditional Tibetan tapestries that have been used for religious and educational purposes since ancient times! The techniques applied can vary greatly, but they usually use silk or cotton fabrics to paint or embroider on. What you can depict in a Thangka is really versatile, and I wanted to represent things that make up Aang as a character."

Zuko and Azula: Japanese Ukiyo-e

"Ukiyo-e is a style that has been around Japan between the 17th and 19th century, and focused mainly in representing daily life, theater(kabuki), natural landscapes, and sometimes historical characters or legends!

Ukiyo-e was developed to be more of a fast and commercial type of art, so many drawings we see are actually woodblock prints, so the artist could do many copies of the same art!

I based my Zuko and Azula pieces on the work of Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861) one of the last ukiyo-e masters in Japan! He has a specific piece which featured a fire demon fighting a lord that fought back with lighting, and that really matched Zuko and Azula's main techniques!”

Toph: Chinese Portraiture from Ming and Qing Dynasties

"Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) was one of the longest in China! It was also a period where lots of artistic evolutions were happening, especially when it comes to use of colour! There was not a predilection for portraits during this time, but there are a lot of pieces depicting idealized women and goddesses from the standards of the time. For this portrait of Toph, I imagined something that maybe their parents commissioned, depicting a soft and delicate Toph which we know is not what she is about ♥️

Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) was the last Chinese Dynasty to reign before the Revolution. One of the most famous emperors of this period was Qianlong, and he really liked Western art! He commissioned a lot of portraits of his subordinates, and I chose a portrait of one of his bodyguards as a reference for the second Toph portrait, which I believe is much more like how she would want to be represented! The poem on top talks about the bodyguards' achievements during a specific war. I had no time to come up with a poem for Toph, so I just used the same one for the composition!”

Sokka and Katara: Inuit Lithograph

"For a long time, Inuit art expressed itself in utilitarian ways. The Nomadic lifestyle of early Inuit tribes played a huge part in that: most art pieces are carved in useful tools, clothing, or children's toys, small and easy to be transported, and depicted scenes and patterns representing their daily lives!

That changed a lot during the colonization. Since the settling of the Inuit tribes, many art pieces began to be created in order to be exported to foreigns, so they started to sculpt bigger and more decorative pieces.

Lithography, which is a type of printmaking, was introduced to Inuit people by James Houston, that learned the technique from the japanese. The art form was quickly embraced by the inuit, as part of the process is very similar to carving. Prints that are produced by inuit artists are still being sold today!

As lithography is not an old art style and it's still commercially relevant to the Inuit communities, since creating these in 2021 I have been donating regularly to the Inuit Art Foundation, not only all the money I get from selling some prints of these but a bit more, at least once a year. Hopefully, I can increase donations this year!”

666 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this Op-Ed from the New York Times:

At first glance, Xi Jinping seems to have lost the plot.

China’s president appears to be smothering the entrepreneurial dynamism that allowed his country to crawl out of poverty and become the factory of the world. He has brushed aside Deng Xiaoping’s maxim “To get rich is glorious” in favor of centralized planning and Communist-sounding slogans like “ecological civilization” and “new, quality productive forces,” which have prompted predictions of the end of China’s economic miracle.

But Mr. Xi is, in fact, making a decades-long bet that China can dominate the global transition to green energy, with his one-party state acting as the driving force in a way that free markets cannot or will not. His ultimate goal is not just to address one of humanity’s most urgent problems — climate change — but also to position China as the global savior in the process.

It has already begun. In recent years, the transition away from fossil fuels has become Mr. Xi’s mantra and the common thread in China’s industrial policies. It’s yielding results: China is now the world’s leading manufacturer of climate-friendly technologies, such as solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles. Last year the energy transition was China’s single biggest driver of overall investment and economic growth, making it the first large economy to achieve that.

This raises an important question for the United States and all of humanity: Is Mr. Xi right? Is a state-directed system like China’s better positioned to solve a generational crisis like climate change, or is a decentralized market approach — i.e., the American way — the answer?

How this plays out could have serious implications for American power and influence.

Look at what happened in the early 20th century, when fascism posed a global threat. America entered the fight late, but with its industrial power — the arsenal of democracy — it emerged on top. Whoever unlocks the door inherits the kingdom, and the United States set about building a new architecture of trade and international relations. The era of American dominance began.

Climate change is, similarly, a global problem, one that threatens our species and the world’s biodiversity. Where do Brazil, Pakistan, Indonesia and other large developing nations that are already grappling with the effects of climate change find their solutions? It will be in technologies that offer an affordable path to decarbonization, and so far, it’s China that is providing most of the solar panels, electric cars and more. China’s exports, increasingly led by green technology, are booming, and much of the growth involves exports to developing countries.

From the American neoliberal economic viewpoint, a state-led push like this might seem illegitimate or even unfair. The state, with its subsidies and political directives, is making decisions that are better left to the markets, the thinking goes.

But China’s leaders have their own calculations, which prioritize stability decades from now over shareholder returns today. Chinese history is littered with dynasties that fell because of famines, floods or failures to adapt to new realities. The Chinese Communist Party’s centrally planned system values constant struggle for its own sake, and today’s struggle is against climate change. China received a frightening reminder of this in 2022, when vast areas of the country baked for weeks under a record heat wave that dried up rivers, withered crops and was blamed for several heatstroke deaths.

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clean energy contributed a record 11.4tn yuan ($1.6tn [USD]) to China’s economy in 2023, accounting for all of the growth in investment and a larger share of economic growth than any other sector.

The new sector-by-sector analysis for Carbon Brief, based on official figures, industry data and analyst reports, illustrates the huge surge in investment in Chinese clean energy last year – in particular, the so-called “new three” industries of solar power, electric vehicles (EVs) and batteries.

Solar power, along with manufacturing capacity for solar panels, EVs and batteries, were the main focus of China’s clean-energy investments in 2023, the analysis shows.[...]

Clean-energy investment rose 40% year-on-year to 6.3tn yuan ($890bn), with the growth accounting for all of the investment growth across the Chinese economy in 2023.

China’s $890bn investment in clean-energy sectors is almost as large as total global investments in fossil fuel supply in 2023 – and similar to the GDP of Switzerland or Turkey.

Including the value of production, clean-energy sectors contributed 11.4tn yuan ($1.6tn) to the Chinese economy in 2023, up 30% year-on-year.

Clean-energy sectors, as a result, were the largest driver of China’ economic growth overall, accounting for 40% of the expansion of GDP in 2023.[...]

The surge in clean-energy investment comes as China’s real-estate sector shrank for the second year in a row. This shift positions the clean-energy industry as a key part not only of China’s energy and climate efforts, but also of its broader economic and industrial policy.[...]

The growing importance of these new industries gives China a significant economic stake in the global transition to clean-energy technologies.[...]

In total, clean energy made up 13% of the huge volume of investment in fixed assets in China in 2023, up from 9% a year earlier.[...]

The major role that clean energy played in boosting growth in 2023 means the industry is now a key part of China’s wider economic and industrial development.[...]

Solar was the largest contributor to growth in China’s clean-technology economy in 2023. It recorded growth worth a combined 1tn yuan of new investment, goods and services, as its value grew from 1.5tn yuan in 2022 to 2.5tn yuan in 2023, an increase of 63% year-on-year.

While China has dominated the manufacturing and installations of solar panels for years, the growth of the industry in 2023 was unprecedented.[...]

An estimated 200GW was added across the country during 2023 as a whole, more than doubling from the record of 87GW set in 2022[...]

China experienced a significant increase in solar product exports in 2023. It exported 56GW of solar wafers, 32GW of cells and 178GW of modules in the first 10 months of the year, up 90%, 72% and 34% year-on-year respectively [...] However, due to falling costs, the export value of these solar products only increased by 3%.

Within the overall export growth there were notable increases in China’s solar exports to countries along the “belt and road”, to southeast Asian nations and to several African countries.[...]

China installed 41GW of wind power capacity in the first 11 months of 2023, an increase of 84% year-on-year in new additions. Some 60GW of onshore wind alone was due to be added across 2023[...]

In addition, offshore wind capacity increased by 6GW across the whole of 2023.[...]

By the end of 2023, the first batch of “clean-energy bases” were expected to have been connected to the grid, contributing to the growth of onshore wind power, particularly in regions such as Inner Mongolia and other northwestern provinces. The second and third batches of clean-energy bases are set to continue driving the growth in onshore wind installations.

The market is also being driven by the “repowering” of older windfarms, supported by central government policies promoting the model of replacing smaller, older turbines with larger ones.[...]

Despite technological advancements reducing costs, increases in raw material prices have resulted in lower profit margins compared to the solar industry[...]

China’s production of electric vehicles grew 36% year-on-year in 2023 to reach 9.6m units, a notable 32% of all vehicles produced in the country.

The vast majority of [B]EVs produced in China are sold domestically, with sales growing strongly despite the phase-out of purchase subsidies announced in 2020 and completed at the end of 2022.[...]

Sales of [B]EVs made in China reached 9.5m units in 2023, a 38% year-on-year increase. Of this total, 8.3m were sold domestically, accounting for one-third of Chinese vehicle sales overall, while 1.2m [B]EVs were exported, a 78% year-on-year increase.[...]

China’s EV market is highly competitive, with at least 94 brands offering more than 300 models. Domestic brands account for 81% of the EV market, with BYD, Wuling, Chery, Changan and GAC among the top players.[...]

The analysis assumes that EVs accounted for all of the growth in investment in vehicle manufacturing capacity [...] while investment in conventional vehicles was stable[...]

Meanwhile, EV charging infrastructure is expanding rapidly, enabling the growth of the EV market. In 2022, more than 80% of the downtown areas of “first-tier” cities – megacities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou – had installed charging stations, while 65% of the highway service zones nationwide provided charging points.

More than 3m new charging points were put into service during 2023, including 0.93m public and 2.45m private chargers. The accumulated total by November 2023 reached 8.6m charging points.[...]

China is rapidly scaling up electricity storage capacity. This has the potential to significantly reduce China’s reliance on coal- and gas-fired power plants to meet peaks in electricity demand and to facilitate the integration of larger amounts of variable wind and solar power into the grid.

The construction of pumped hydro storage capacity increased dramatically in the last year, with capacity under construction reaching 167GW, up from 120GW a year earlier.[...]

Data from Global Energy Monitor identifies another 250GW in pre-construction stages, indicating that there is potential for the current surge in capacity to continue.

Construction of new battery manufacturing capacity was another major driver of investments, estimated at 0.3tn [yuan].[...]

Investment in electrolysers for “green” hydrogen production almost doubled year-on-year in 2023, reaching approximately 90bn yuan, based on estimates for the first half of the year from SWS Research. [...]

China’s ministry of transportation reported that investment in railway construction increased 7% in January–November 2023, implying investment of 0.8tn for the full year. This includes major investments in both passenger and freight transport. Investment in roads fell slightly, while investment in railways overall grew by 22%.

The share of freight volumes transported by rail in China has increased from 7.8% in 2017 to 9.2% in 2021, thanks to the rapid development of the railway network.

In 2022, some 155,000km of rail lines were in operation, of which 42,000km were high-speed. This is up from 146,000km of which 38,000km were high-speed in 2020.[...]

In 2023, 10 nuclear power units were approved in China, exceeding the anticipated rate of 6-8 units per year set by the China Nuclear Energy Association in 2020 for the second year in a row.

There are 77 nuclear power units that are currently operating or under construction in China, the second-largest total in the world. The total yearly investment in 2023 was estimated for this analysis at 87bn yuan, an increase of 45% year-on-year[...]

State Grid, the government-owned operator that runs the majority of the country’s electricity transmission network, has a target to raise inter-provincial power transmission capacity to 300GW by 2025 and 370GW by 2030, from 230GW in 2021. These plans play a major role in enabling the development of clean energy bases in western China.

China Electricity Council reported investments in electricity transmission at 0.5tn yuan in 2023, up 8% on year – just ahead of the level targeted by State Grid.[...]

China’s reliance on the clean-technology sectors to drive growth and achieve key economic targets boosts their economic and political importance. It could also support an accelerated energy transition.

The massive investment in clean technology manufacturing capacity and exports last year means that China has a major stake in the success of clean energy in the rest of the world and in building up export markets.

For example, China’s lead climate negotiator Su Wei recently highlighted that the goal of tripling renewable energy capacity globally, agreed in the COP28 UN climate summit in December, is a major benefit to China’s new energy industry. This will likely also mean that China’s efforts to finance and develop clean energy projects overseas will intensify.

Globally, China’s unprecedented clean-energy manufacturing boom has pushed down prices, with the cost of solar panels falling 42% year-on-year – a dramatic drop even compared to the historical average of around 17% per year, while battery prices fell by an even steeper 50%.

This, in turn, has encouraged much faster take-up of clean-energy technologies.[...]

The clean-technology investment boom has provided a new lease of life to China’s investment-led economic model. There are new clean-energy technologies where there is scope for expansion, such as [Hydrogen] electrolysers.

Mind-blowing is the only word for it rly [25 Jan 24]

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kenyan tea pickers are destroying machines brought in to replace them during violent protests that highlight the challenge faced by low-skilled workers as more agribusiness companies rely on automation to cut costs.

At least 10 tea-plucking machines have been torched in multiple flashpoints in the past year, according to local media reports. Recent demonstrations have left one protester dead and several injured, including 23 police officers and farm workers. The Kenya Tea Growers Association (KTGA) estimated the cost of damaged machinery at $1.2 million (170 million Kenyan shillings) after nine machines belonging to Ekaterra, makers of the top-selling tea brand Lipton, were destroyed in May.

In March, a local government taskforce recommended that tea companies in Kericho, the country’s largest tea-growing town, adopt a new 60:40 ratio of mechanized tea harvesting to hand-plucking. The taskforce also wants legislation passed to limit importation of tea harvesting machines. Nicholas Kirui, a member of the taskforce and former CEO of KTGA, told Semafor Africa 30,000 jobs had been lost to mechanization in Kericho county alone over the past decade.

"We did public participation in all the wards and with all the different groups, and the overwhelming sentiment we were hearing was that the machines should go," Kirui said.

In 2021, Kenya exported tea worth $1.2 billion, making it the third-largest tea exporter globally, behind China and Sri Lanka. Multinationals including Browns Investments, George Williamson and Ekaterra — which was sold by Unilever to a private equity firm in July 2022 — plant on an estimated 200,000 acres in Kericho and have all adopted mechanized harvesting.

Some machines can reportedly replace 100 workers. Ekaterra's corporate affairs director in Kenya, Sammy Kirui, told Semafor Africa that mechanization was “critical” to the company’s operations and the global competitiveness of Kenyan tea. As the government taskforce established, one machine can bring the cost of harvesting tea down to 3 cents (4 Kenyan shillings) per kilogram from 11 cents (15.32 shillings) per kilogram with hand-plucking.

Analysts partly attribute Kenya's unemployment rate — the highest in East Africa — to automation in industries, including banking and insurance. Some 13.9% of working age Kenyans (over 16) were out of work or long term unemployed in the final quarter of 2022.

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of the "Third World"

There is this false notion of "lesser economically developed countries", or "third world countries", wherein people from the "more economically developed countries" believe if the other places Did It Right, then they would become as prosperous and have as high living standards as the "first world".

This is false, because the "first world"'s entire way of living depends entirely on the "third world" taking a different trajectory.

There is literally no possible way for China to live like the UK without, for example, dominating other countries and using them as their main means of production instead, which is what the UK and the USA and France and Germany have done. We have exported our industries and imported all the benefits they bring.

This is why environmentalism is a fucking joke. The UK is so proud of being a greener country but we are simply exporting all our enviromental damage to China and India by having all our factories made there, and having all our vegetation made elsewhere in Europe. We make charts and say we are doing better! Our emissions are down! Look, we've banned petrol cars from London! Then we point to China and go, look how bad their environmental standards are! Look how bad that air pollution is!

Who is responsible for the air pollution in China? It isn't the Chinese. What if one day, China went "fuck this, your factories are ruining our lives and we aren't going to run them anymore"? Would China just get sanctioned into oblivion? Would they lose all the completely necessary economic development that the UK claims China is so behind on?

That's it though, if you're not top of the food chain like the UK was a century or so ago, you need to take a different route to get there because you haven't got the same means of enslavement and resources. And that either involves the domination of nearby countries, and exporting resources there to improve local quality of life, or it involves sacrificing your own environment in order to become an economically powerful country.

I think a lot of people in the UK still don't understand the great power that China and India have developed taking this path, they don't understand that if those countries stopped cooperating, the UK would die within a couple of months. We are not a strong, independent country with a good quality of life. We are like an old abusive relative who is taking advantage of our background of colonialism to exploit countries that are working way harder and better to grow.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: Rice noodles topped with yellow fried tofu and chives; piles of chili powder, peanuts, and chive stems to the side. End ID]

ผัดไทย / Phad thai (Thai noodle dish with tamarind and chives)

Phad thai, or pad thai ("Thai stir-fry") is a dish famous for its balance of sour, sweet, savory, and spicy flavors, and its combination of fried and fresh ingredients. It's commonly available in Thai restaurants in the U.S.A. and Europe—however, it's likely that restaurant versions aren't vegetarian (fish sauce!), and even likelier that they don't feature many ingredients that traditionalists consider essential to phad thai (such as garlic chives or sweetened preserved radish—or even tamarind, which they may replace with ketchup).

Despite the appeals to tradition that phad thai sometimes inspires, the dish as such is less than 100 years old. Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram popularized the stir-fry in the wake of a 1932 revolution that established a constitutional monarchy in Thailand (previously Siam); promotion of the newly created dish at home and abroad was a way to promote a new "Thai" identity, a way to use broken grains of rice to free up more of the crop for export, and a way to promote recognition of Thailand on a worldwide culinary stage. Despite the dish's patriotic function, most of the components of phad thai are not Thai in origin—stir-fried noodles, especially, had a close association with China at the time.

My version replaces fish sauce with tao jiew (Thai fermented bean paste) and dried shrimp with shiitake mushrooms, and uses a spiced batter that fries up like eggs. Tamarind, palm sugar, prik bon (Thai roasted chili flakes), and chai po wan (sweet preserved radish) produce phad thai's signature blend of tart, sweet, and umami flavors.

Recipe under the cut!

Patreon | Tip jar

Serves 2.

Ingredients:

For the sauce:

3 Tbsp (35g) Thai palm sugar (น้ำตาลปึก / nam tan puek)

2 Tbsp vegetarian fish sauce, or a mixture of Thai soy sauce and tao jiew

1/4 cup tamarind paste (made from 50g seeded tamarind pulp, or 80g with seeds)

Thai palm sugar is the evaporate of palm tree sap; it has a light caramel taste. It can be purchased in jars or bags at an Asian grocery, or substituted with light brown sugar or a mixture of white sugar and jaggery.

Seedless tamarind pulp can be purchased in vacuum-sealed blocks at an Asian grocery store—try to find some that's a product of Thailand. I have also made this dish with Indian tamarind, though it may be more sour—taste and adjust how much paste you include accordingly.

You could skip making your own tamarind paste by buying a jar of Thai "tamarind concentrate" and cooking it down. Indian tamarind concentrate may also be used, but it is much thicker and may need to be watered down.

For the stir-fry:

4oz flat rice noodles ("thin" or "medium"), soaked in room-temperature water 1 hour

1/4 cup chopped Thai shallots (or substitute Western shallots)

3 large cloves (20g) garlic, chopped

170g pressed tofu

3 Tbsp (23g) sweet preserved radish (chai po wan), minced

1 Tbsp ground dried shiitake mushroom, or 2 Tbsp diced fresh shiitake (as a substitute for dried shrimp)

Cooking oil (ideally soybean or peanut)

The rice noodles used for phad thai should be about 1/4" (1/2cm) wide, and will be labelled "thin" or "medium," depending on the brand—T&T's "thin" noodles are good, or Erawan's "medium." They may be a product of Vietnam or of Thailand; just try to find some without tapioca as an added ingredient.

Pressed tofu may be found at an Asian grocery store. It is firmer than the extra firm tofu available at most Western grocery stores. Thai pressed tofu is often yellow on the outside. If you can't locate any, use extra firm tofu and press it for at least 30 minutes.

Sweetened preserved radish adds a deeply sweet, slightly funky flavor and some texture to phad thai. Make sure that your preserved radish is the sweet kind, not the salted kind.

For the eggs

¼ cup + 2 Tbsp (60g) white rice flour

3 Tbsp (22.5g) all-purpose flour (substitute more rice flour for a gluten-free version)

1 tsp ground turmeric

About 1 ¼ cup (295mL) coconut milk (canned or boxed; the kind for cooking, not drinking)

¼ tsp kala namak (black salt), or substitute table salt

Pinch prik bon (optional)

To serve:

Prik bon

2 1/2 cups bean sprouts

3 bunches (25g) garlic chives

1 banana blossom (หัวปลี / hua plee) (optional)

1/3 cup peanuts, roasted

Additional sugar

Garlic chives, also known as Chinese chives or Chinese leeks, are wider and flatter than Western chives. They may be found at an Asian grocery; or substitute green onion.

Banana blossoms are more likely to be found canned than fresh outside of Asia. They may be omitted if you can't find any.

Instructions:

For the eggs:

1. Whisk all ingredients together in a mixing bowl. Cover and allow to rest.

For the noodles:

1. Soak rice noodles in room-temperature water for 1 hour, making sure they're completely submerged. After they've been soaked, they feel almost completely pliant. Cut the noodles in half using kitchen scissors.

For the tamarind paste:

1. Break off a chunk of about 50g seedless tamarind, or 80g seeded. Break it apart into several pieces and place it at the bottom of a bowl. Pour 2/3 cup (150mL) just-boiled water over the tamarind and allow it to soak for about 20 minutes, until it is cool enough to handle.

2. Palpate the tamarind pulp with your hands and remove hard seeds and fibres. Pulverise the pulp in a blender (or with an immersion blender) and pass it through a sieve—if you have something thicker than a fine mesh sieve, use that, as this is a thick paste. Press the paste against the sieve to get all the liquid out and leave only the tough fibers behind.

You should have about 1/4 cup (70g) of tamarind paste. If necessary, pour another few tablespoons of water over the sieve to help rinse off the fibers and get all of the paste that you can.

3. Taste your tamarind paste. If it is intensely sour, add a little water and stir.

For the sauce:

1. If not using vegetarian fish sauce, whisk 1 Tbsp tao jiew with 1 Tbsp Thai soy sauce in a small bowl. You can also substitute tao jiew with Japanese white miso paste or another fermented soybean product (such as doenjang or Chinese fermented bean paste), and Thai soy sauce with Chinese light soy sauce. Fish sauce doesn't take "like" fish, merely fermented and intensely salty, and that's the flavor we're trying to mimic here.

2. Heat a small sauce pan on medium. Add palm sugar (or whatever sugar you're using) and cooking, stirring and scraping the bottom of the pot often, until the sugar melts. Cook for another couple of minutes until the sugar browns slightly.

3. Immediately add tamarind and stir. This may cause the sugar to crystallize; just keep cooking and stirring the sauce to allow the sugar to dissolve.

4. Add fish sauce and stir. Continue cooking for another couple of minutes to heat through. Remove from heat. Taste and adjust sugar and salt.

To stir-fry:

1. Cut the tofu into pieces about 1" x 1/4" x 1/4" (2.5 x 1/2 x 1/2cm) in size.

2. Separate the stalks of the chives from the greens and set them aside for garnish. Cut the greens into 1 1/2” pieces.

3. Chop the shallots and garlic. If using fresh shiitake mushrooms, dice them, including the stems. If using dried, grind them in a mortar and pestle or using a spice mill.

4. Roast peanuts in a skillet on medium heat, stirring often, until fragrant and a shade darker.

5. Remove the tough, pink outer leaves of the fresh banana blossom until you get to the white. Cut off the stem and cut lengthwise into wedges (like an orange). Rub exposed surfaces with a lime wedge to prevent browning. If your banana blossom is canned, drain and cut into wedges.

6. Heat a large wok (or flat-bottomed pan) on medium-high. Add oil and swirl to coat the wok's surface.

If you're using extra firm (instead of pressed) tofu, fry it now to prevent it from breaking apart later. Add about 1" (2.5cm) of oil to the wok, and fry the tofu, stirring and flipping occasionally, until golden brown on all sides. Remove tofu onto a plate using a slotted spoon. Carefully remove excess oil from the wok (into a wide bowl, for example) and reserve for reuse.

7. Fry shallots, garlic, preserved radish and tofu (if you didn't fry it before), stirring often, until shallots are translucent. Add mushroom and fry another minute.

8. Add pre-fried tofu, drained noodles, and sauce to the wok. Cook, stirring often with a spatula or tossing with tongs, until the sauce has absorbed and the noodles are completely pliant and well-cooked. (If sauce absorbs before the noodles are cooked, add some water and continue to toss.)

9. Push noodles to the side. Add 'egg' batter and re-cover with the noodles. Cook for a couple minutes, until the egg had mostly solidified. Stir to break up the egg and mix it in with the noodles.

10. Remove from heat. Add half the roasted peanuts, half of the bean sprouts, and all of the greens of the chives. Cover for a minute or two to allow the greens to wilt.

11. Serve with additional peanuts, bean sprouts, banana blossom wedges, chive stems, and lime wedges on the side. Have prik bon and additional grated palm sugar at table.

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

On May 14, Washington slapped new tariffs on China in what looks at first glance like the latest round of a familiar trade spat. The White House imposed duties of 25 to 50 percent on a range of industrial, medical, and clean tech goods—including semiconductors, solar cells, batteries, steel, aluminum, graphite, magnets, syringes, and ship-to-shore cranes. Strikingly, the latest measures also include a whopping 100 percent tariff on electric vehicles, effectively shutting the U.S. market to Chinese-made EVs.

Seen from Washington, these measures also look like a political move as U.S. President Joe Biden courts blue-collar voters in industrial swing states such as Michigan and Pennsylvania ahead of the November presidential election. It’s unlikely, however, that Beijing shares this benign interpretation. Seen from China, the tariffs look like a serious escalation of the U.S.-China contest and are probably raising alarm bells. Here’s why.

1. Washington is playing the long game. Stories of how China has become the world leader in EV manufacturing and is flooding the world with cheap vehicles have flourished over recent months. At the global level, there certainly is something to this analysis. Chinese exports of EVs jumped by a whopping 80 percent last year, propelling China to the top of the global ranking of car exporters. Yet this does not apply to the United States, where China supplied just 2 percent of EVs sold last year. (U.S. consumers appear to have a distinct preference for South Korean, Japanese, and European EV imports.) In other words, a 100 percent tariff on a few thousand cars will not hit Chinese firms hard.

A closer look at the list of targeted sectors suggests that batteries, not cars, will be the real pain point for China. The U.S. market is important for Chinese battery firms, which supply around 70 percent of the lithium-ion batteries used in the United States. For China’s battery sector, this means that the impact of the latest U.S. tariffs will likely be huge: The usual rule of thumb is that a 1 percentage point increase in tariffs entails a 2 percent drop in trade. With tariffs rising from 7.5 percent to 25 percent, the rule suggests that Chinese battery firms’ U.S. sales could drop by around one-third—or by $5 billion when one includes the entire battery supply chain. With Chinese battery-makers already seeing their profits plummet amid softening global demand, this is certainly bad news for Beijing.

Crucially, batteries are also an area where the U.S. government is investing huge amounts of public funds, in particular through the Inflation Reduction Act, which seeks to boost U.S. domestic production of clean tech goods. Seen in this light, the latest U.S. tariffs are preemptive measures to protect a nascent clean tech industry and make sure that there is domestic demand for future U.S. production. This suggests that the United States is playing the long game here, with little chance the tariffs will be lifted anytime soon. On the contrary—the U.S. clean tech market could well be closed to Chinese firms from here on out.

2. The White House is trying to force Europe to come on board and impose similar tariffs on China. Biden is probably seeking to score electoral brownie points with a 100 percent tariff on EVs, making former President Donald Trump’s proposal for 60 percent on U.S. imports from China look almost feeble. (Not to be outdone, Trump just announced that he would apply a 200 percent tariff on Chinese-branded cars made in Mexico.) Yet the reality is that Biden’s tariffs will not prove game-changing in the short term: Their implementation will be phased in over two years, and supply chain adjustments typically take time. In short, the measures are unlikely to fuel a U.S. industrial boom in time for the November elections.

What will happen before the election, though, is the conclusion in June or July of the European Union’s ongoing anti-subsidy investigation into China’s EV makers. Rumors abound of a possible tariff of 20 to 30 percent on Chinese EVs. Such a prospect is probably unnerving for Beijing; the EU is the biggest export market for China’s EVs, absorbing around 40 percent of Chinese shipments. The United States hopes that its 100 percent tariff on EVs will compel the EU to not only follow Washington’s example in imposing a tariff on Chinese EVs but perhaps also consider a higher one. This bold strategy could well work. Europe is unlikely to enjoy having its arm twisted by Washington, but the bloc will also worry that Chinese EV makers could double down on their push to dominate the EU market now that they have lost access to the U.S. one.

Chinese EVs look set to be a key topic when G-7 leaders meet for their annual summit in June. The United States will probably try to cajole Germany, which has long been dovish vis à vis China, into supporting sharply higher tariffs. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has pointed to the fact that European auto manufacturers “sell a great many vehicles that are produced in Europe to China”—hinting at German fears that China could retaliate against EVs and internal combustion engine cars imported from the EU.

3. The tariffs are a serious escalation from Washington’s previous de-risking strategy. In recent years, U.S. de-risking has focused on reducing the United States’ reliance on China for crucial goods and curbing Beijing’s access to dual-use technology in a bid to avoid fueling the country’s military advances. To implement this strategy, Washington has so far relied on two main tools from its economic statecraft kit: financial sanctions (for instance, on firms linked to the People’s Liberation Army) and export controls (notably on semiconductors, which are dual-use goods found in most military equipment).

Washington is slowly realizing that these two tools are imperfect. China’s massive sanctions-proofing efforts mean that sanctions do not always deal a blow to Chinese firms, which may no longer be using the U.S. dollar (China now settles around half of its cross-border trade in renminbi) or Western financial channels such as SWIFT, the global payments system. Washington also understands that export controls on clean tech would not curb China’s ambitions in the field, as Chinese firms already have all the tech they need. This leaves only one option for U.S. economic statecraft: tariffs that leverage one of the country’s greatest economic assets—access to its market.

This is why the latest U.S. tariffs are likely raising red flags in Beijing. The United States is now severing access to its market in clean tech and other areas that China sees as crucial for its plans to become the world’s future economic superpower. If the EU plays ball, this approach would expose a central flaw in Beijing’s industrial strategy: What if the world’s two biggest markets—the United States and the EU—become no-go areas for Chinese firms dependent on exporting their vast production, leaving them with piles of unused goods? Few other markets are available for Chinese clean tech exports—outside Europe, North America, and East Asia, most countries lack the infrastructure for large-scale EV adoption, for example. This prospect may well keep Beijing’s planners up at night, with no easy solution in sight.

The question now is whether and how Beijing will react. Serious retaliation is unlikely, since the United States exports far less to China than vice versa. Given its current economic woes, China also has little interest in further weakening its economy—for example, by imposing export bans on critical raw materials, rare earths, or other crucial goods for Western economies.

As the latest skirmish in the battle for economic dominance between Washington and Beijing, the new U.S. tariffs raise a number of bigger questions: Will Washington succeed in its efforts to create a domestic ecosystem for clean tech? Will the United States and Europe manage to cooperate—or go their own ways in their economic relations with China? Will the United States continue to curb Chinese access to the U.S. market for the purposes of de-risking—and if so, in which sectors? There is probably only one certainty in the U.S.-China economic war: The conflict will continue well after the November elections, whatever their outcome.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Have I ever told y’all how much I hate fellow Americans sometimes?

Anyways. Russia is trying to hide jets by gluing spare tires to them, Ukraine has taken a port, there’s another coup starting in the Congo, China grows increasingly aggressive in the Taiwan Strait, cocaine is about to surpass oil as Columbia’s top export, the F-35 is apparently stealthy enough that not even the US government could find the lost one for more than a day, and there is no insider trading in Ba Sing Se (Unity is absolutely fucking up right now).

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jo is the holder of a newly minted degree in English literature from one of the top universities in Laos. But the 22-year-old, who graduated only weeks ago, says he already feels "hopeless".

Confronted with a barren job market, the Vientiane resident holds no hope of finding work at home, and instead aims to become a cleaner or a fruit picker in Australia. His aspirations are low, but they reflect a hushed disenchantment spreading among his peers; the result of a severe and sustained economic downturn that has ravaged Laos for the past two years.

"Every person in this generation doesn't believe in the government. They want to leave Laos, they don't believe anything the government says," he tells the BBC. "Most of my friends have the same thoughts, but we only talk about it privately. If you say bad things about them in public, I don't know what will happen."

The economic crisis has been caused by a rash programme of government borrowing used to finance Chinese-backed infrastructure projects which has begun to unravel. The crisis shows little sign of easing, with public debt spiralling to unsustainable levels, resulting in government budget cuts, sky-high inflation and record-breaking currency depreciation, leaving many living on the brink in one of South East Asia's poorest countries.

Faced with a dire economic situation, and with the April shooting of activist Anousa "Jack" Luangsuphom underscoring the brutal lengths authorities in the one-party state will go to silence calls for reform, a generation of young Laotians increasingly see their future abroad.

"[Young people] aren't even thinking about change, it's a feeling of how am I going to get out of this country - I'm stuck here, there's no future for me," said Emilie Pradichit, a Lao-French international human rights lawyer and the founder of human rights group Manushya Foundation.

"If you see your country becoming a colony of China, you see a government that is totally corrupt, and you cannot speak up because if you do you might be killed - would you want to stay?"

The 'debt trap'

A sparsely populated, landlocked country of 7.5 million people, Laos is one of the region's poorest and least developed nations. In a bid to transform the largely agrarian society, the past decade has seen the government take on major infrastructure projects, mostly financed by historic ally and neighbour China - itself on a lending spree since 2013 as part of its global infrastructure investment programme, the Belt and Road initiative (BRI).

Laos has built dozens of foreign-financed dams to transform itself into the "battery of South East Asia" as a major exporter of electricity to the region. But oversupply has turned many dams unproductive, and the state electricity company sits in $5bn (£4.1bn) debt. Lacking funds, Laos handed a majority Chinese-owned company a 25-year concession to manage large parts of its power grid in 2021, including control over exports.

Also among the debt-laden megaprojects is the Lao-China railway, connecting Vientiane to southern China. It opened in December 2021 at a cost of $5.9bn (£4.85bn), but saddled the Lao government with $1.9bn in debt. Beijing says the railway has created an "economic corridor", but the numbers just don't add up for some economists, not least because Chinese state-owned companies hold a 70% stake.

"I'm sure people are happy to travel very quickly across Laos, but it's not justified at the cost that was agreed to," economist Jayant Menon, a senior fellow at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, says of the railway.

All of this has added to Laos' ballooning debt, which is now ninth highest globally as a share of its GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund. Around half of that is owed to China, and Laos is now having to borrow more from lenders in the country just to stay afloat.

"Laos is so heavily indebted to China that their negotiating position is compromised," he said. "It's having to borrow just to service the debt. That's the definition of a debt trap."

The Lao government could not be reached for comment. But Mr Menon emphasised that Laos has repeatedly rejected other international lenders in favour of Beijing, perhaps because of a belief within the government that China "will not let another socialist country fail". He added that Beijing was also cautious about letting another BRI country default on its debt after Sri Lanka.

The only thing currently preventing that outcome are repeated Chinese debt deferment agreements - the conditions of which remain highly opaque. This has raised concerns over Beijing's growing sway over Laos. When asked if Laos is at risk of becoming a vassal state, Mr Menon said "that ship has sailed".

He said that the "macro-instability" caused by "massive debt accumulation" has also caused the decline of the Lao currency, the kip, which continues to depreciate to record lows against the US dollar. This has led to a decades-high rise in prices, and nowhere is this being felt more acutely than among ordinary Laotians.

'If I don't fight, I'll die'

"'I have never experienced anything like this year," says Phonxay, a frail looking woman in her 60s, selling household staples at a food market in Vientiane. She said her customers are buying less because "prices go up day to day", adding that August was the most expensive month yet. Her family has had to adapt to survive.

"My family needs to eat more cheaply than ever before. We eat half of what we used to eat," Phonxay says. "But I'll fight until the end. If I don't, I'll die."

But it's young Lao, their futures mortgaged off for the benefit of infrastructure projects offering them few tangible opportunities, that will bear the brunt of the economic crisis for years to come.

"Lao is very good to travel, but not good to live in," says Sen, a 19-year-old working as a receptionist in a hotel in Luang Prabang in northern Laos.

The city is bustling once again, with its Unesco World Heritage Old Quarter of pristine French colonial-era buildings filled with tourists. But Sen says times remain tough: "For normal people like me it's very hard. It's just better than living as a homeless person in India, and maybe just better than North Korea. I'm serious, we're just trying to survive."

He earns just $125 per month at his hotel job, but he doesn't see any point in going to university or applying for government jobs as he'd have to "pay lots of money" to corrupt officials to get anywhere as he has no family connections.

"At the moment, almost every Lao student like myself doesn't want to go to university," he says. "They study Japanese or Korean and then apply to work in factories or farming in those countries."

It's this "sense of discouragement among Lao youth… that needs urgent attention," says Catherine Phuong, the deputy resident representative at the UN Development Programme in Laos. She pointed to the "staggering" NEET (not in education, employment or training) rate of 38.7% among 18-to-24-year olds - by far the highest in South East Asia.

"We're especially concerned in Laos that with the debt situation we are seeing reduced investment in the social sector, including health and education," she told the BBC. "I'm sure you can imagine the impact that will have on this generation, not just in the coming years, but in the next 10 to 20 years."

But with the Lao People's Revolutionary Party, which has ruled the country since 1975, intolerant of dissenting voices, young people have had to turn to social media to air their grievances.

It was in March 2022, as inflation and the cost of living began rising, that Anousa "Jack" Luangsuphom created Kub Kluen Duay Keyboard or "The Power of the Keyboard", one of a growing number of social commentary Facebook pages critical of authorities.

The 25-year-old was drawing tens of thousands of followers when he was attacked at a cafe in Vientiane on April 29. CCTV footage shows a masked man firing a bullet into Jack's face and chest. A police statement days later blamed a business dispute or lover's quarrel. Jack survived the attack, but for his followers, the culprit was obvious.

"I feel really bad that the government would shoot him, that they would try to control us like that," says Jo, the university student in Vientiane, who follows Jack's Facebook page. "Jack is the voice of Lao people, he said things that normal people are afraid to say."

But these calls for reform will only be ignored or suppressed, and few know this better than Shui-Meng Ng - the wife of disappeared Lao civil society advocate Sombath Somphone.

Sombath has not been seen since being detained by police in Vientiane in December 2012, a time when his influence was growing and there was hope of reform.

Speaking to the BBC from her craft shop in downtown Vientiane, the last place she saw her husband the day he was abducted, Shui-Meng said voices like Jack's and Sombath's are squashed because they grow "too big a following" at times when the "Lao political elite are facing difficulties".

"Every time something like [Jack's shooting] happens, you see this," she said, zipping her lips. "People go silent."

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

Care to share the James Bond moment?

18 years old. Beijing. Burns Supper Event. Government officials, business people and…me are all attending this event being hosted at a stunning five star hotel. A Scottish ceilidh band had been flown in to Beijing to host and everything, and they’d sourced all of the ingredients for haggis to be made in China (as you can’t export haggis due to issues exporting offal).

This event was on from 5pm to 7am the next morning. 7 courses. Open bar. Midnight snacks. Breakfast in the morning. It was nuts.

I’m sitting at a table with the First Secretary of Scottish Affairs - the Scottish Government’s top person in China - and a mixture of other government & business folk.

I’m one of the few attendees wearing a kilt and, not to wank myself off, but I’m pretty good at ceilidh dancing so I get stuck in when the band starts playing. Gay Gordon’s is my absolute jam.

After the first few dances, more and more people gain the confidence to join in and this culminates in a *huge* Orcadian Strip the Willow. The band starts it relatively slowly but by the end they’re playing absolutely full pelt and the speed has skyrocketed.

2/3rds of the way through the song, when me and my partner were going down the middle - one of the tassels from my sporran came off and hit the deck. The dance was so fast that I was never gonna be able to grab it without interrupting the whole flow.

First Secretary for Scottish Affairs picked it up and shouted to me that he had it, I yelled to throw it and managed to catch it one-handed, mid-spin without slowing down.

Will forever be one of the coolest Bond moments of my life.

361 notes

·

View notes

Text

The AP found that U.S. prison labor is in the supply chains of goods being shipped all over the world via multinational companies, including to countries that have been slapped with import bans by Washington in recent years. For instance, the U.S. has blocked shipments of cotton coming from China, a top manufacturer of popular clothing brands, because it was produced by forced or prison labor. But crops harvested by U.S. prisoners have entered the supply chains of companies that export to China.

While prison labor seeps into the supply chains of some companies through third-party suppliers without them knowing, others buy direct. Mammoth commodity traders that are essential to feeding the globe like Cargill, Bunge, Louis Dreyfus, Archer Daniels Midland and Consolidated Grain and Barge – which together post annual revenues of more than $400 billion – have in recent years scooped up millions of dollars’ worth of soy, corn and wheat straight from prisons, which compete with local farmers.

...Incarceration was used not just for punishment or rehabilitation but for profit. A law passed a few years [after the formal end of the convict-leasing system in 1928] made it illegal to knowingly transport or sell goods made by incarcerated workers across state lines, though an exception was made for agricultural products. Today, after years of efforts by lawmakers and businesses, corporations are setting up joint ventures with corrections agencies, enabling them to sell almost anything nationwide.

Civilian workers are guaranteed basic rights and protections by OSHA and laws like the Fair Labor Standards Act, but prisoners, who are often not legally considered employees, are denied many of those entitlements and cannot protest or form unions.

“They may be doing the exact same work as people who are not incarcerated, but they don’t have the training, they don’t have the experience, they don’t have the protective equipment,” said Jennifer Turner, lead author of a 2022 American Civil Liberties Union report on prison labor.

#this whole article is good read the whole thing#it's extremely important that reporters & activists continue to bring to light the horrific abuses of prison labor#& that we all understand that none of this is new - angola / louisiana state prison is immense & has a vast bloody history#the largest agricultural producer in the state of texas in the 60s was the department of corrections#& as this article points out a rising reliance on incarcerated labor is one response#to the labor shortages caused by unchecked covid deaths + restrictive immigration policy#the whole of american incarceration & labor policy is evil. blood on the leaves & blood at the root

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s been almost two full years since Russia invaded Ukraine, prompting the West to impose unprecedented sanctions on Russia’s economy, which happened to be Europe’s main energy supplier at the time. To this day, Russia remains the world’s most sanctioned country, far surpassing other ‘revisionist’ states like Iran, Syria and North Korea.

One month after Russian tanks rolled across the border, President Biden announced that “the ruble was almost immediately reduced to rubble” and “the Russian economy is on track to be cut in half”. Likewise, the French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire foresaw “the collapse of the Russian economy”. Russia “was ranked the 11th biggest economy in the world before this invasion,” Biden added. “Soon, it will not even rank among the top 20”.

How have these predictions panned out?

Not well. As an article in the FT notes, “Russia grew faster than all G7 economies last year and the IMF forecasts it will again in 2024”. So not only has the Russian economy failed to collapse – let alone be cut in half – but it’s actually growing at a steady clip. According to the IMF, Russia grew 2.6% in 2023, as compared to 0.8% in France, 0.5% in Britain and –0.3% in Germany.

A big problem for the West is that the stuff Russia sells – oil and gas – is extremely useful. So one way or another, countries are going to try to get their hands on it. This includes Europe. As of Q3 2023, Russia still accounts for 12% of the EU’s natural gas imports – and more than 20% of its fertiliser imports. In fact, EU imports of Russian LNG have jumped 40% since the invasion began so that EU countries now account for the majority of Russia’s LNG exports.

Another big problem is that Russia has a strong ally in China, the world’s second most powerful country and the main geopolitical rival of the US. While China has refrained from supplying lethal aid to Russia for sound strategic reasons, it absolutely wants to avoid a scenario where the Russian state falls apart. As I wrote of the Chinese last summer, “they can’t tolerate a defeated Russia but can easily live with a weakened one”.

9 notes

·

View notes