#historical men's fashion

Text

While I am still mad about historical men's fashion: my other pet peeve is when someone tries to do an "18th century vs. 19th century" thing, and it's literally court dress from like 1790, covered with embroidery and jewels, compared with ordinary day attire for a 19th century man.

Like. Imagine comparing the most outrageous cyber-goth club wear from the 1990s with a cheap 2010s men's business suit!

"THIS IS WHAT THE DOT COM BOOM TOOK AWAY FROM US! Men used to go to work with green plastic hair extensions and slutty fishnet tops with their tripp pants covered with bright cables and chains! Now they wear 'BUSINESS SUITS' in boring navy and black. 🙄😩💅🏻"

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ranking Men's Costumes in Period Dramas - Part II: The Good

Part I: The Bad

This is the second part to my ranking of men's costumes in Renaissance period dramas. I selected 10 shows and films which I think have great costuming for the female characters and ranked them according to their costumes for male characters. I have noticed that even when women's costuming is great, men's costuming might be absolutely dog shit. And that's very much what we saw in the first part, where I ranked the five worst entries. For some reason shows and movies are afraid to put men, especially the characters who are supposed to be cool, manly and hot, into historical costumes. And I'm not even asking for historical accuracy, I just don't want my male characters living in the actual 1500s in basically modern leather jackets and pants. Like I don't watch period dramas for vaguely historically inspired modern fashion, I watch it for the historical setting, which costumes help create. This time we will be looking some rare gems that actually imo have really good costuming even for the male characters. For the five best entries, we'll go from worst to best.

5. Eizabeth R (1971)

Elizabeth R is incredibly committed to historical accuracy in it's outfits, especially for queen Elizabeth herself, many of her costumes being directly recreated from her portraits. It covers the whole reign of Elizabeth, so this commitment is especially admirable as the timeline is more than 40 years, including a stark shift in fashion from less structured and more toned down Tudor fashion to the extremes of the highly structured Elizabethan fashion. It's not perfect, The hair is not always great and like many others they fail at French hoods, though they are not upward pointing or pseudo crowns detached from the hood, so could be much worse.

The men's costumes are also very good. They are faithful to history, they wear stockings, very short trunk hose, ruffs and even have some structuring in their doublets and jerkins. However, the reason this is not higher is that the men's costumes especially, but also many other costumes beside Elizabeth's are looking a little sloppy. There's some structure yes, but the men's silhouettes are just not bold enough and they end up looking a little costumy. Even the codpieces are shrunk so small I'm not even sure if they are the half the time. Cowardice. Here's two Robert Dudley's costumes and an actual portrait of him. I think the second costume is probably an attempt at recreation of that portrait, but it's just kinda halfway there.

4. Taming of the Shrew (1967)

This film is set in Renaissance Italy, the women's costumes fit well to 1520s-30s. They are honestly really great and cohesive. My only gripe is that their bodices have a very 1960s shape and the make-up is a little distractingly modern. But the costuming is not attempting to recreate historical accuracy, rather they took the historical silhouette and basic elements and crafted a very over the top but cohesive look. I honestly love these very much.

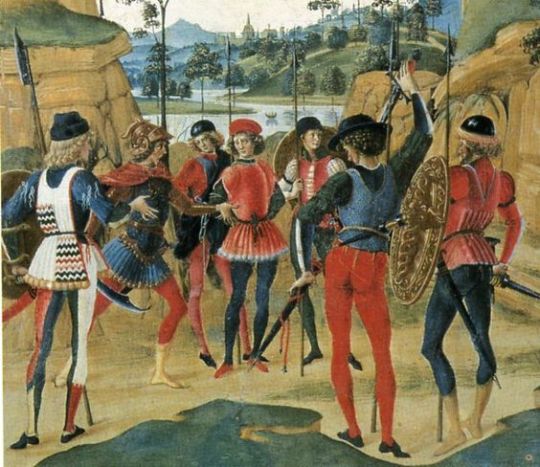

An interesting choice is made with the men's costuming, especially the main male lead, whose costume is based much more on the Renaissance German men's fashion of that period. His costumes resemble the over the top fashion of the German Landsknecht (first image below). In Italy (second image below) the doublets were also very voluminous and quite colourful but not to that extent as by the Landsknecht and literally no one, not even the other Germans, rocked that slashed style as hard.

This is not really criticism though. In fact I respect that choice a lot. His costumes are certainly not historically accurate, but they do fit the bombastic aesthetics of the overall costuming, they are loud, large and not afraid to fuck around. This man oozes sex-appeal much more than any character with some modern plain black pants and leather jacket. This is how you costume a Renaissance man who fucks.

3. Tulip Fever (2017)

I am stretching the definition or Renaissance here a bit, I admit. This movie is set during the 1630s tulip mania, by which point the remnants of Renaissance fashion had already been left to the previous decade. However, I do think most of the movies and tv set in Baroque era also struggle with the men's costumes. Though not as much, because black was fashionable for everyone, the cod piece was gone, trunk hose were replaced by more palatable Venetian hose, fashion was much more stripped down from embellishments, leather was not uncommon in jerkins and appeared even in doublets and hose and the Hollywoods beloved boots became as actual fashion items. The men's silhouette in this period is very silly in my opinion and people seem to agree because it's usually skipped in costuming, but overall the period seems to fit modern masculinity standards much more easily than Renaissance era.

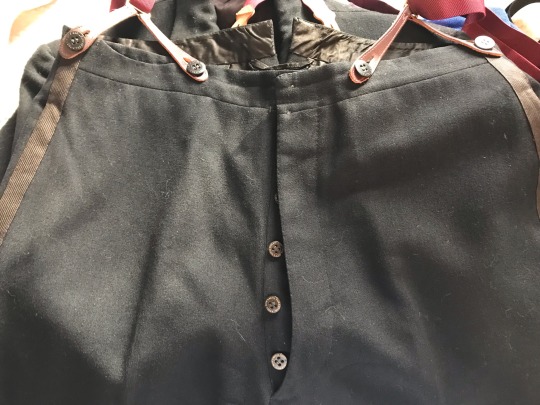

But I just really wanted to include this because the costuming is absolutely stunning. I have not watched the movie and probably never will because the post production was an absolute mess and it apparently came out as just a bad movie, which is a shame, but the costumes are so good. The ruffs are perfectly crispy. The buttons are dense and look just right. The shoes, both boots and otherwise are exactly right. The fabrics are honestly perfect. The silhouettes are just as goofy as they are supposed to be. And the women too have perfect silhouettes. All the details are just simply perfect. You rarely find costuming this meticulously created with historical details and great construction.

Honestly these top three could all be the best one. This final order was decided purely on which costumes i like more. And while I love the women's fashion of this period, I think the men's fashion is kinda stupid and boring, so I don't like these costumes on aesthetic level as much as the top two.

2. Romeo and Juliet (1968)

This movie is a perfect counterpart to the movie with the worst men's costuming which I talked about in the first post, Rosaline. They are both set in Italy around very end of 15th century and retell Romeo and Juliet. Both have very good costuming for female characters but obviously I think differ greatly in the male character costuming department. Romeo and Juliet costuming takes some artistic liberties to create a heightened reality quite similar to Taming of the Shrew costuming, but follows history much more closely. The colors are bright, the hose are tight, the giorneas are voluminous, the sleeves are long and massive and the cod pieces are prominent. Even the hair is perfect, even for women, they even use hairnets. I imagine the hair was quite easy to get right as hairstyles in 60s and 70s were basically lifted directly from 1400s Italian hairstyles. The men are even wearing appropriate hats??? Amazing.

The costuming perfectly captures the era, but they still clearly had fun with the costumes too. Honestly even though I appreciate the meticulously recreated historically accurate costuming, like in Tulip Fever, I tend to like more costuming that does take some artistic liberties to create a distinct look and atmosphere for the movie or tv show. There's some small things they don't get quite right, like having standard lacing instead of ladder lacing, metal eyelets (which would become a thing as late as in 1830s) and most egregiously Juliet in one scene has this very dumb supportive undergarment without even shift under it (first picture below)?? The outer garments were supportive during this era, there was no such thing as supportive undergarment. Shift was the only undergarment. But I will forgive these errors because the costuming is overall so fun and gorgeous. And they did get some details so so right, like look at Romeo's arming doublet (second picture below)! It has Lombardian sleeves!! This was a very specific style of arming doublet for this era and place. However those errors does prevent it from taking the first place. Which leads us to...

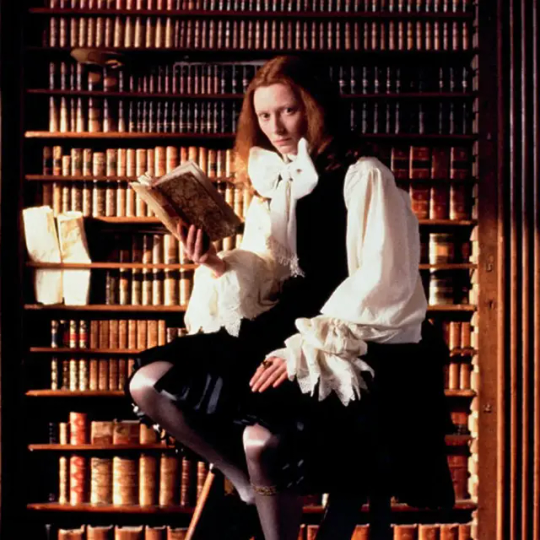

1. Orlando (1992)

This movie has Tilda Swinton in flamboyant Elizabethan men's clothing. That's all.

Okay, I that is all that needs to be said, but I will say more. This movie spans centuries and shows excellent costumes from several different periods, but I will focus on the Elizabethan costumes only for the sake of this post. The costuming is not super historically accurate in all the detailing, and clearly not trying to be, but it is always impeccable. Even while it takes artistic liberties and the story has an immortality fantastical element it still captures the men's fashion's silhouette much better than any other movie or tv show I know of set in this period. It does that better than the "we recreated these portraits" Elizabeth R. But what really makes this the best in my humble opinion, is that the movie is not afraid of the effeminate and emasculated modern perception of Renaissance men's fashion, no, it leans into it. The thole story is very much about gender and gender fuckery. Tilda Swinton plays the titular Orlando who is a cis man in Elizabethan era, becomes inexplicably immortal and later inexplicably turns into a woman for the rest of their several centuries. He is the embodiment of "I'm not sure if they are a butch or a twink" and as a bisexual I can only be grateful. But in all seriousness I think the costuming and the casting (queen Elizabeth is also played by a male actor) are so perfectly utilized to highlight the arbitrary construction of gender without needing to say it explicitly.

Conclusion

I have some closing thoughts. I took on this task as a way to show a point, which is that for some reason in Renaissance shows and film especially men's costuming is piss-poor, even when women's costuming is great. Male characters tend to have very bad costuming in Medieval media too, though this is also an issue for female characters. I don't think I have ever seen a Medieval show or movie with truly excellent costuming for anyone. In Renaissance media the issue is clearly not lack of skill or knowledge, they choose to do so. My thesis was that the producers think that the Renaissance men's fashion is too effeminate and too unsexy for the hot male very heterosexual lead, who the mostly female audience are supposed fawn over like the female characters. I still think it's very true.

Though there's an interesting trend I only noticed while doing this ranking; every entry (except the least bad) in the worst five list are from 21th century, and every entry (except Tulip Fever which is a little bit cheating anyway) in this best five list are from 20th century. I have some theories on why it turned out this way. First is that the studios have become increasingly more concerned with growing profits so they don't take risks and they put pressure on movies and tv shows to be as broadly appealing as possible. This means they can't just make period dramas for the core audience of period dramas, aka mostly women who are history nerds, so they pander to the modern sensibilities in costuming and not to the people who love to see actual historical costuming. Secondly, I think this might also tie to the broader conservative backlash against loosening of gender roles and broader queer acceptance. Among the core audiences of period dramas there are two distinct groups, queer nerds and conservative/centrist women, who don't want politics in their media, which is why they love historical stories because obviously queerness wasn't invented yet and people of colour didn't exist yet (they were and did). (They are not always this extreme, but you get the point.) As men wearing dresses has become a culture war issue, I think the studio executives are afraid that anything not masculine enough in modern standards might cause the more conservative audiences to turn on them. Even if they knew about the queer nerds, they wouldn't care about them.

This bears repeating: cowards.

As a thank you for reading all the way to the end I will leave you with the image of Tilda Swinton in mid 1600s men's clothing. You are welcome.

Part I: The Bad

#fashion history#history#historical costuming#costuming#renaissance fashion#renaissance costuming#film costuming#historical men's fashion

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

1930s evening ensemble

Every piece is vintage except for my socks, and I bought them all separately across the country over two years. Almost everything required repairs.

The jacket had damaged sleeve lining which I replaced. One of the front buttons had bent and busted off, and was placed in a pocket. It’s roughly 1930s I think. The company was Foreman & Clark Clothes, “Upstairs from coast to coast”.

The trousers are Basil Durant Inc. New York. Most likely 1930s as well. Basil Durant was a vaudeville actor who started a tailoring business after vaudeville’s decline. It has silk lining on the trousers which had to be restitched.

1940s/30s? Red Suspenders. I’m honestly not as sure on the date for these, but they are in perfect condition. Bonus picture of Paris Swing suspenders about 1930s or 40s.

Paris garters 1930s or 40s.

1910s/1920s vest. It was heavily yellowed from starch which came out with gentle hand washing. Unknown maker

1920s/1930s evening shirt. This one probably had the worst damage since I know it was used by costumers/actors. The second buttonhole was completely opened and ravelled. Various stains and pinholes. I had to rebound the buttonhole.

1900s-1920s collar

Silk scarf about 1940s.

1970s Floreshime shoes.

1890s-1910s watch fob.

#1930s#1930s menswear#historical fashion#extant garments#formal wear#tuxedo#historical men's fashion#menswear#vintage menswear#vintage

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photos of 16th-17th century Irish clothing

Extant garments in the National Museum of Ireland

Notes: The garments in this post are all bog finds which means their current color may not be their original color. Although some of these items were found with human remains, no photos of human remains are included in this post.

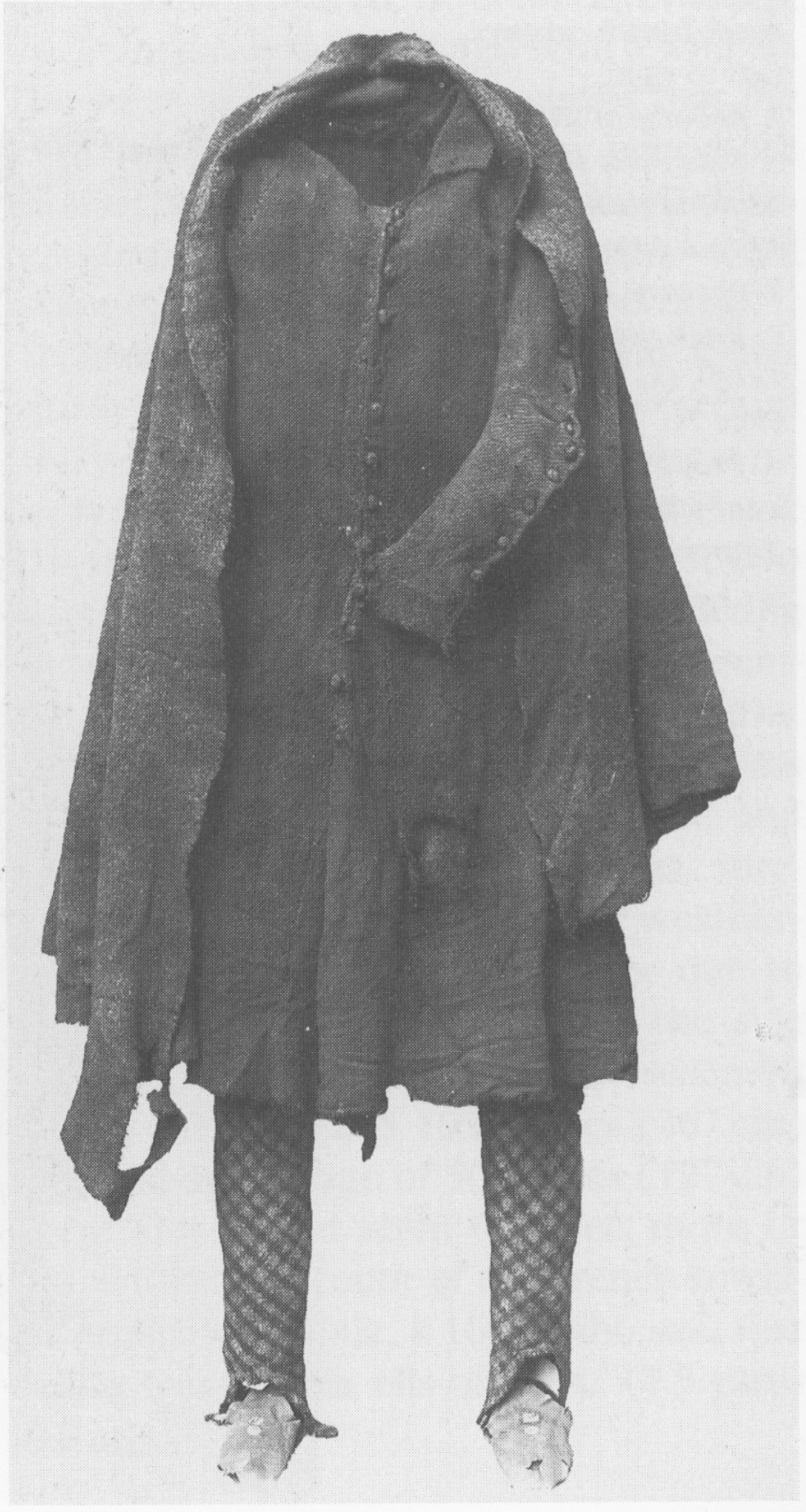

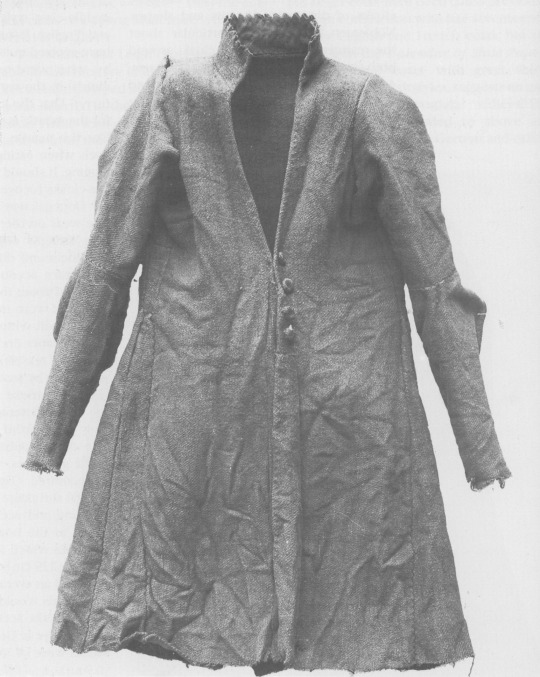

Killery Cóta Mór (great coat) and brogues:

photos by hayling billy used under non-commercial, share alike license

The Killery outfit comes from an adult male bog body found in Killerry parish, Co. Sligo in 1824. It includes a cóta mór, triús, a brat, and shoes which are on display in the museum, and a sheepskin biorraid (conical hat) which fell apart shortly after it was found (Briggs and Turner 1986).

Killery triús (trews):

photo by hayling billy

Killery outfit with and without brat:

The outfit is generally dated to the 17th c. (Dunlevy 1989). It matches Luke Gernon's 1620 description of Irish men's winter apparel:

"in winter he weares a frise cote. The trowse is along stocke of frise, close to his thighes, and drawne on almost to his waste, but very scant, and the pryde of it is, to weare it so in suspence, that the beholder may still suspecte it to be falling from his arse. It is cutt with a pouche before, which is drawne together with a string."

Additional photos of the outfit: cóta front, hem, buttons, and brat.

Shinrone gown:

photo by hayling billy

The Shinrone gown was found in a bog in 1843 in Co. Tipperary near Shinrone, Co. Offaly. Unlike the Killery outfit, there were no human remains or other items found with it (Briggs and Turner 1986). The ends of the sleeves and possibly also the bottom of the skirt are missing. The sleeves would have had wrist cuffs or ties that allowed them to be fastened around the wearer's wrists. It probably also had loops or rings along the U-shaped center-front opening for lacing. It is typically dated late 16th-early 17th c, based on its similarity to a circa 1575 illustration by Lucas DeHeere and to the dresses described by Luke Gernon in 1620 (Dunlevy 1989, McGann 2000). It could be older however, because Laurent Vital described dresses with this type of sleeve in 1518.

Copyrighted, better quality photos: left front, right front, back Additional details: side-front, front waistline

Tipperary Cóta Mór:

photos from Dunlevy 1989 and hayling billy

Another Cóta Mór. This one is from Co. Tipperary, exact find spot and date unknown. Like the Shinrone gown, it was not found with human remains or other items (Ó Floinn 1995). It is probably also from the 17th century (Dunlevy 1989).

Additional photos: front, side, front buttons, front detail, side

Brat and hats:

photo by hayling billy

I haven't been able to find any clear photos of the label on this display, but based on the excellent condition and the presence of the leather tie, I think this is the Meenybradden woman's brat.

Closeup of the tie:

The Meenybradden woman is a bog body found in Meenybradden bog, Co. Donegal in 1978. The brat was wrapped around her as a shroud and secured with the leather tie (Delaney and Ó Floinn 1995). No other garments or artifacts were found with her, although she may have been wearing a linen garment such as a léine when she was buried. Linen tends to not survive in bogs. The Meenybradden woman has a calibrated radiocarbon date of AD 1130-1310, but some archaeologist have suggested humic contamination from the peat may be throwing off the dating. Her brat is identical in cut to others from the 16th-17th centuries (Delaney and Ó Floinn 1995).

Meenybradden brat laid flat. (photo from Delaney and Ó Floinn 1995)

Wool hats:

Hats from Boolabaun, Co. Tipperary made of wool felt which has been cut and sewn to form the shape. They have togs of unspun wool worked into them giving them the appearance of faux fur. Dunlevy suggests a 15th-16th c date for them (Dunlevy 1989, McClintock 1943).

Wool cloak:

photo by hayling billy

The museum label says it's from Glenmalin bog, Malinmore, Co. Donegal, but I think this may be a mistake. According to Ó Floinn (1995), the artifact with accession number 1946:416 from Malinmore, Co. Donegal is a bale of linen. Ó Floinn's table also gives accession number 1946:416* for a group of clothing from Owenduff, Co. Mayo which includes a gown, a jacket, and a cloak. If the cloak in the photo is actually the one from Owenduff, it is probably from the 17th c (Dunlevy 1989). Alternatively, someone might have misidentified a wool cloak as a bale of linen. The museum label dates this as late Medieval to post-Medieval.

*Either Ó Floinn made a typo or this is a mistake in the museum records. Museums are not supposed to give the same accession number to 2 different artifacts. In the NMI's defense, 1946 was probably a messy year for everyone.

Bibliography:

Briggs, C. S. and Turner, R. C. (1986). Appendix: a gazetteer of bog burials from Britain and Ireland. In I. Stead, J. B. Bourke and D. Brothwell (eds) Lindow Man: the Body in the Bog (p. 181–95). British Museum Publications Ltd.

Delaney, M. and Ó Floinn, R. (1995). A Bog Body from Meenybradden Bog, County Donegal, Ireland. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 123–32). British Museum Press.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Gernon, Luke (1620). A Discourse of Ireland. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E620001/

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

McGann, K. (2000). What the Irish Wore/The Shinrone Gown — An Irish Dress from the Elizabethan Age. Reconstructing History. http://web.archive.org/web/20080217032749/http:/www.reconstructinghistory.com/irish/shinrone.html

O’Floinn, R. (1995). Recent research into Irish bog bodies. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 137–45). British Museum Press.

Vital, Laurent (1518). Archduke Ferdinand's visit to Kinsale in Ireland, an extract from Le Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagne, de 1517 à 1518. translated by Dorothy Convery and edited by me. https://irish-dress-history.tumblr.com/post/721163132699131904/laurent-vitals-1518-description-of-ireland

#16th century#17th century#irish dress#dress history#gaelic ireland#historical men's fashion#historical women's fashion#bog finds#irish history#historical dress#brog#bratanna#irish mantle#headwear#triús#cóta mór

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

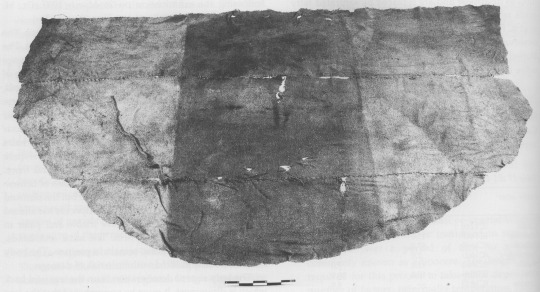

New shirts & handkerchiefs

Robert Coningham took such good care of his dearest boy, making sure he had enough clothes and didn't have to buy them abroad.

#james fitzjames#royal navy#naval history#historical men's fashion#1830s fashion#historical clothing

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

A friend made that for me. I am known too well by my friends. 😂

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I haven’t seen it on here, but Emma Corrin’s outfit was inspired by an outfit worn by Evander Berry Wall, a Gilded Age New York society man. I’d honestly never heard of him before, but his Wikipedia page is fascinating.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

GENTLEMANS' EMBROIDERED SILK SUIT, c. 1775

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

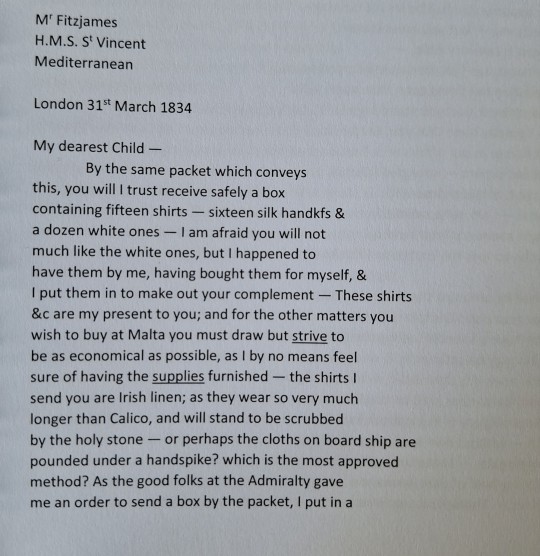

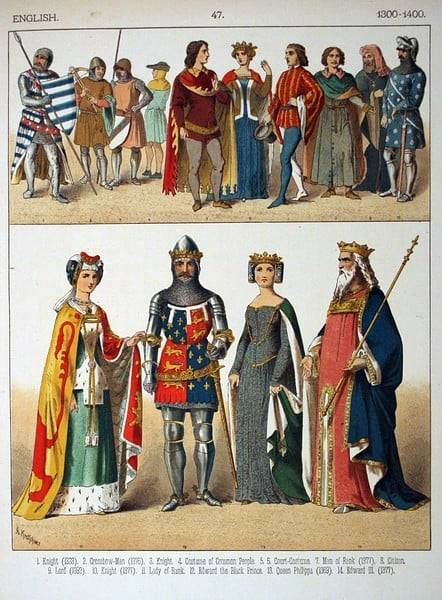

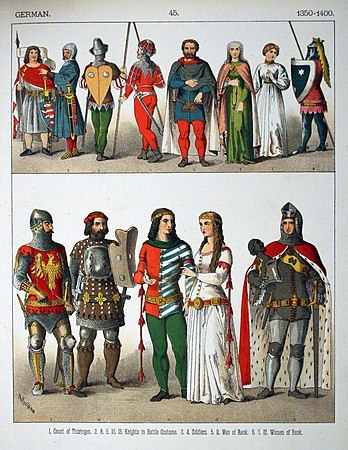

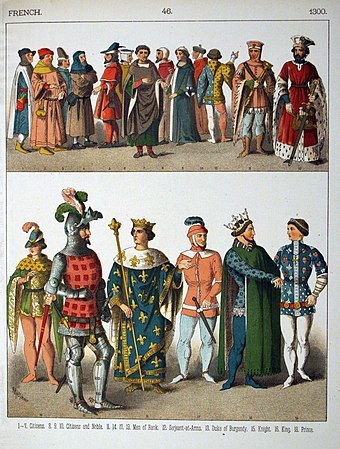

Part 1

So there have been a lot of posts about how "Men should dress like men" and how they miss "the good old days"

What they really mean to say is "I have no real idea how people dressed before the 1800s when long trousers (pants that resemble slacks or jeans) first became common."

Or "I imagine the "Good old days" as 1950."

Or "I don't realize that the only people who wore what we think of as pants were the poor or working class and even they likely ended at the knee"

Judging people by their clothing choices is flawed in many ways.

Many people are limited in what they wear by money, either the money to afford interesting clothing or the need to dress a certain way to hold a job.

Others (like myself) are limited by the lack of clothing that fit them or that they are comfortable in, just because someone makes clothes your size doesn't mean they feel emotionally or physically comfortable to some people.

Some people are limited because of their age and inability to buy their own clothes

Others are limited by motivation, they might like how certain clothes look and even think they would look cool on them but they just can't motivate to find stuff they like and try on new things.

But most people are just lacking enough IMAGINATION OR DARING to even think of trying something that isn't exactly what "Most people" do or that their father's approve of. It simply never occured to them to try anything different.

There is nothing wrong with dressing like the majority of other people in your community but it isn't a good way to judge others.

So for those who think the "Good old days" slacks and button down shirts here is just a sample of styles from the last 3000 or so years

#toxic masculinity#clothes dont make the person#historical men's fashion#let people like what they like#let people express themselves

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fabrics of Marryat's world

One of the things that stands out to me, as a twenty-first century reader of Captain Marryat, are his many references to specific textiles and fabrics. Part of that could be from his reputation as a man of fashion; but I suspect that it's mostly a reflection of the world he inhabited, full of bespoke clothing and aware of its value. (As Frank Mildmay said, "A tailor's bill you may avoid by crossing the channel; but the duns of conscience follow you to the antipodes, and will be satisfied.")

A hated assistant teacher in Jacob Faithful is identified by his coat of shalloon:

I have little further to say of Mr. Knapps, except that he wore a black shalloon loose coat; on the left sleeve of which he wiped his pen, and upon the right, but too often, his ever-snivelling nose.

The materials glossary in Handbook of English Costume in the 19th Century by C. Willett and Phillis Cunnington defines shalloon as, "A loosely woven worsted stuff, twilled on both sides."

In Poor Jack, the title character's mother is an ambitious businesswoman, who dresses her daughter to the best of her abilities and neglects her son. One character comments on this:

Does your mother make plenty of money by clear-starching? I know your sister had a spotted muslin frock on last Sunday, and that must have cost something. [...] Your mother dresses your sister in spotted muslin, and leaves you in rags

A spotted muslin dress for a child in the Victoria & Albert Museum collection, made c. 1800-1805.

This extant dress is embroidered with tambour work, noted as a pastime of well-bred young ladies in Japhet in Search of a Father ("Cecilia, my dear, show your tambour work to Mr. Newland, and ask him his opinion. Is it not beautiful, Mr. Newland?")

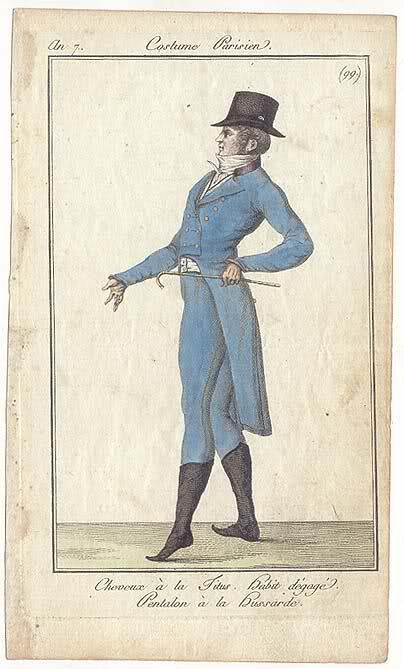

In Marryat’s world, textiles are named: kerseymere breeches, cambric handkerchiefs, cotton-net pantaloons. The cotton-net pantaloons are specifically mentioned in three of Marryat's novels: Peter Simple, Japhet in Search of a Father, and Poor Jack.

Names for textiles have changed over time, and I wonder if what Marryat calls "cotton-net" is synonymous with stockinette? ("[Pantaloons] were usually of stockinette or semi-elastic material," says Handbook of English Costume in the 19th Century). As much as Regency gentlemen wore some very suggestive clothing, I don't think they wore pants of sheer netting.

Still, one character in Poor Jack is showing off a lot of pantaloons in his (unfortunately) body-conscious choice of fabric:

Mr. Cobb was remarkable in his dress. Having sprung up to the height of at least six feet in his stockings, he had become remarkably thin and spare; and the first idea that struck you when you saw him was, that he was all pantaloons—for he wore blue cotton net tight pantaloons; and his Hessian boots were so low, and his waistcoat so short, that there was at least four feet, out of the sum total of six, composed of blue cotton net, which fitted very close to a very spare figure.

"Pentalon à la hussarde" in the collection of the Paris Musées (and on a more ideal figure).

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#regency#men's fashion#fashion history#textiles#fabrics#dress history#fashion#cotton-net#hussar pants eh#historical men's fashion#jacob faithful#japhet in search of a father#poor jack#peter simple#frank mildmay#pantaloons#if marryat's novels got the TV/film adaptations they deserved#i feel like almost all of them would have a trying-on-clothes montage

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

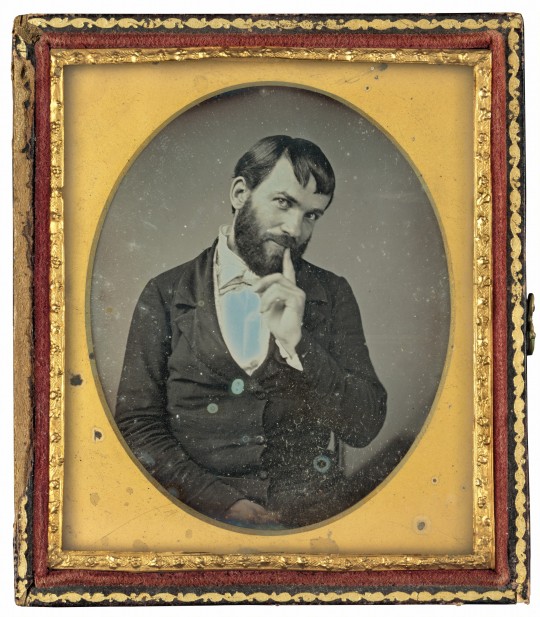

Eighteen-fifties man being silly in the photography studio, what will he do!

538 notes

·

View notes

Note

1890s menswear by any chance? Colour is up to you. If you only do womanswear, then 1610s in yellow.

Thanks! I love your work, it's gorgeous

Sure thing! I don't usually draw men since I'm not great at them and woman's clothing gives me more options, but I tried!

Prompt: Send a year from 1400 - 1960 and a colour to my askbox and I’ll try to paint someone from that time period. (Status: Open) Note: I have only these two variables in the prompt to keep things simple for me. If you choose to request something more specific, I might go with it, but if I'm particularly busy or unfamiliar with the specified variable I might either ignore the more specific parts of the request or ignore the request entirely.

1730s Black, 1900 Pink | 1848 Violet | 1914 Green | 1890s White | 1700 Dark Green | 1860 Black | 1650 Red | 1650 Blue | 1924 Purple | 1847 Green | 1830 Light Blue | 1530 Green | 1402 Orange | Blue 1870s | Green 1471 | Mint Green 1540s | Red 1518 | Yellow 1480s | Violet 1950s | Purple 1880s | 1930s "Pink"

Disclaimer: Though I do try to research things and look at historical images and portraiture, I do make mistakes and make no promises that what I paint will be entirely historically accurate.

#historical dress#historical costuming#historical fashion#art#fashion#painting#drawing#watercolor#artists on tumblr#artwork#victorian fashion#victorian era#victorian#historical#fashion history#historical men's fashion#history of fashion#history#1890s fashion#1890s

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patterning a 16th c. Irish léine sleeve

Mid-16th c. images of the léine from "Drawn after the Quick" and Codice de Trajes

The léine of 16th century Ireland had huge, iconic sleeves. Sadly, we have neither surviving examples of this garment, nor detailed period documentation, so we don't know how these sleeves were made. I have seen a couple different sewing patterns purposed, but none of these match the voluminous, gathered sleeves shown in the Codice de Trajes and the costume album of Christoph von Sternsee. This is my attempt to create a sleeve pattern that better matches the surviving evidence.

The cut of léine sleeves probably varied across 16th c. Ireland, potentially impacted by factors like a person's wealth or where in Ireland they lived. It almost certainly changed over time as more of Ireland fell to English colonial conquest. The wearing of the large-sleeved léine was banned by King Henry VIII (McClintock 1943). Lucas de Heere’s circa 1575 illustrations show women with much smaller sleeves than earlier images. However, at least during the early part of the century, sleeves did not vary by gender. According to Laurent Vital, the only difference between a man's léine and a woman's léine was that the woman's had gores in the bottom it make it fuller (Vital 1518).

My goal with this project is to create a léine sleeve pattern for an early to mid-16th c. Irish person living outside of the Pale. Since none of the period images or texts are very detailed, I am combining information from several sources.

Englishman Edmund Campion who visited Ireland in 1569 gave the following derisive description of the léine: “Linnen shirts the rich doe weare for wantonnes and bravery, with wide hanging sleeves playted, thirtie yards are little enough for one of them” (Campion 1571).

Campion’s claim that the sleeves were pleated initially struck me as strange. English and continental European shirts from this period frequently had gathered sleeves (Mikhaila and Malcolm-Davies 2006, Arnold, Tiramani and Levey 2008), but pleating isn’t the same thing as gathering. However, other period writers made similar claims. Writing in 1596, Edmund Spenser mentioned "thicke foulded lynnen shirtes” as a garment worn by the Irish (Spencer 1633).

Similarly, Fynes Moryson described the léine as being made of “thirty or forty ells [of linen] in a shirt all gathered and wrinkled,” elsewhere he described it as “folded in wrinckles” (Moryson 1617).

In The Image of Irelande, John Derricke gave the following description of the léine:

Their shirtes be verie straunge,/ not reachyng paste the thie:/ With pleates on pleates thei pleated are,/ as thicke as pleates maie lye./ Whose sleves hang trailing doune/ almoste unto the Shoe (Derricke 1581)

Assuming that Derricke’s description is not just poetic license, I know of one 16th century construction method that matches the description “pleats on pleats [. . .] as thick as pleats may lie,” and that is cartridge pleating. Cartridge pleating is a technique that is more commonly used on thick fabrics like woolens, because a lot of fabric bulk is needed to keep the pleats standing properly, but extant 16th and early 17th c. neck ruffs use cartridge pleating to join massive lengths of fine linen to a neck band (Arnold, Tiramani and Levey 2008).

Cartridge pleating on a thick woolen fabric

A person unfamiliar with sewing methods and terms might well describe cartridge pleating as looking like folds, gathers, or wrinkles.

The léine sleeve patterns commonly used in modern reconstructions are completely flat, like a Japanese kimono sleeve with rounded corners. (There’s also a version which has a drawstring or gathering running along the top of the sleeve. This is a 20th c. Ren Fair invention which has no historical basis.)

The end-on views of the sleeve openings in the recently-discovered images from Codice de Trajes and the costume album of Christoph von Sternsee clearly show that this is not correct. The rounded shape they show for the sleeve end can only be achieved through gathering.

Archer from the von Sternsee costume album and the O’Brien messenger from The Image of Irelande

The best illustration of a léine in The Image of Irelande, the messenger on plate 7, also provides evidence for a gathered sleeve. The way the fabric drapes in the middle of the sleeve suggests that the sleeve is gathered at both ends. Furthermore, the way the mass of a léine sleeve centers under the wearer’s arm when the wearer holds their arm out straight, like the O’Brien messenger, but hangs down like a trumpet when the wearer lowers their arm, like on von Sternsee’s archer also suggests that the sleeve is a symmetrical shape that is gathered at both ends and not a trumpet shape that is only gathered at the wrist end.

With these elements in mind, I went looking for a pattern which would create the correct shape. I used Jean Hunnisett's 15th c. bagpipe sleeve pattern from Period Costume for Stage and Screen and the sleeve pattern from this 1630s English waistcoat (published in Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns) as a starting point.

1630s waistcoat sleeve pattern

I replaced the curved sleeve heads in these patterns with the straight sleeve end and square underarm gusset typical of mid-16th-18th c. shirts, since the léine, like the shirt, is an unfitted linen garment, and because the straight edge is much easier to gather all the way around. I don't have any actual evidence for square gussets in 16th c. Ireland, but this pattern definitely needs an ungathered piece at the underarm. Anyone who is bothered by the lack of evidence can use a triangular gusset like the one on the 15th c. Moy gown instead.

After that, I experimented with mock-ups until I figured out how to get the correct proportions. I don't have any training in patterning or draping, so this took several tries. I used my 1/3 scale ball-jointed doll (24 inches tall) as model, because he required a lot less fabric and sewing. Since this was just a mock-up, I used random linen remnants from my stash, and I didn't bother to finish most of the edges.

Here is the final sleeve with the seams sewn together, but before doing the gathering:

This sleeve, on his right arm, is based on the gathered-wrist cuff version of the léine from Codice de Trajes, the von Sternsee album, and The Image of Irelande.

This sleeve ended up with me having to gather 31 inches of fabric into a 5-inch armscye. So yeah, cartridge pleating became necessary, because there is no way to make that kind of reduction work with regular gathering. I also had to do some smocking to get the giant mass of fabric better controlled before I could attach it to the body of the léine.

While this pattern might seem absurd, (it does call for a sleeve end wider than the wear is tall to be pleated into the armscye,) a close examination of John Michael Wright's 1680 portrait of Sir Neil O'Neill shows remarkably similar sleeves.

While this painting is from a century later than my target time period and the clothing clearly shows changes like the addition of English-style shirt sleeve ruffles, the shirt still has elements which I have seen no where else in late 17th c. fashion that are probably derived from earlier Irish dress.

The doublet worn over top prevents it from hanging down properly, but this shirt sleeve has the same bagpipe shape as the 16th c. léine. I have highlighted it in magenta to make this easier to see. The fine, regular folds near the top of the sleeve (highlighted in yellow) are probably the result of smocking or cartridge pleating, indicating that this sleeve, like my purposed pattern, has a large amount of fabric gathered or pleated to the armscye. The wrist end of the sleeve has 3 rows of smocking stitches sewn with silk thread, which shows that the sleeve cuff has a huge amount of fabric gathered into it.

Historically, silk was the thread of choice for smocking, because it is smoother and has greater tensile strength than wool, linen, or cotton. Several 16th c. sources note that the Irish used silk thread when making their léinte (Gresh 2021). Laurent Vital described Irish women as wearing, "chemises with wide sleeves, worked around the collar and in the seams with silk needlework of different colours" (1518). The presence of smocking on O'Neill's shirt combined with my experience trying to recreate this sleeve makes me think that at least some of that 16th c. silk needlework was smocking.

For the left sleeve of my mock-up, I tried to recreate the flatter sleeves from "Drawn After the Quicke". These sleeves do not have a gathered wristband.

This sleeve used basically the same pattern, but the lack of gathering at the wrist opening meant that the whole sleeve was slightly smaller, so I only had to pleat 26 in of fabric into the armscye instead of 31 in. This was just enough of a difference that I could set the sleeve without smocking it first, unlike the right sleeve. I guess this is the more budget-friendly option for your less wealthy kern.

I also made the curve at the bottom of the sleeve wider to give this one a more square shape.

Some of my failed experiments:

I would like to thank my friend Nikki for loaning me her smocking machine. This project would have been a much bigger pain if I had to do all those gathering stitches by hand.

Since this post has gotten rather long, I am putting the actual drafting instruction for this sleeve pattern in a separate post.

If anyone would like to support my work financially, I now have a ko-fi page.

Bibliography:

Arnold, Janet, Tiramani, J., & Levey, S. (2008). Patterns of Fashion 4. Macmillan, London.

Campion, Edmund. (1571). A Historie of Ireland, Written in the Yeare 1571. Dublin. https://archive.org/details/historieofirelan00campuoft/historieofirelan00campuoft/page/n5/mode/2up

Derricke, John. (1581). The Image of Irelande, with the discoverie of a Woodkarne. John Daie, London. https://archive.org/details/imageofirelandew00derr/page/n29/mode/2up?view=theater

Hunnisett, Jean. (1996). Period Costume for Stage & Screen: Patterns for Women's Dress, Medieval-1500. Players Press, Inc, Studio City.

Gresh, Robert. (2021). The Saffron Shirt, Part 1: Saffron and Silk, Urine and Grease. Wilde Irish. https://www.wildeirishe.com/post/the-saffron-shirt-part-1-saffron-and-silk-urine-and-grease

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

McGann, K. (2008). The Invention of Drawstrings and Pleated Sleeves. Reconstructing History. https://reconstructinghistory.com/blogs/irish/the-invention-of-drawstrings-and-pleated-sleeves-1

Mikhaila, Ninya, & Malcolm-Davies, Jane (2006). The Tudor Tailor. Quite Specific Media Group, Ltd, London.

Moryson, Fynes. (1617). An Itinerary Containing His Ten Yeeres Travell through the Twelve Dominions of Germany, Bohmerland, Sweitzerland, Netherland, Denmarke, Poland, Italy, Turky, France, England, Scotland & Ireland. volume 4. https://ia801307.us.archive.org/16/items/fynesmorysons04moryuoft/fynesmorysons04moryuoft.pdf

North, Susan and Jenny Tiramani, eds. (2011). Seventeenth-Century Women’s Dress Patterns, vol.1, V&A Publishing, London.

Spencer, Edmund. (1633). A View of the present State of Ireland. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E500000-001/index.html

Vital, Laurent (1518). Archduke Ferdinand's visit to Kinsale in Ireland, an extract from Le Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagne, de 1517 à 1518. translated by Dorothy Convery. https://irish-dress-history.tumblr.com/post/721163132699131904/laurent-vitals-1518-description-of-ireland

#16th century#irish dress#dress history#leine#art#gaelic ireland#irish history#historical men's fashion#historical dress#historical women's fashion#sewing

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

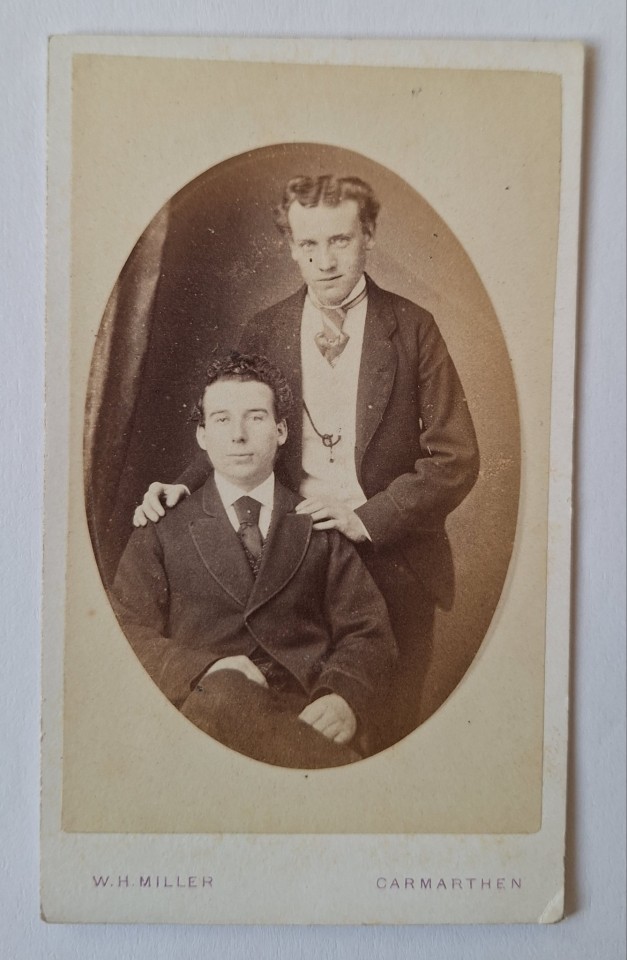

Victorian Friends

Unfortunately these two gentlemen who had their picture taken in 1870s Carmarthen, Wales are not identified. I wonder what their relationship and story is. And wish James Fitzjames and John Barrow could've gotten their picture taken like this.

Carte de visite from my collection:

#carte de visite#historical men's fashion#victorian fashion#victorian photography#friendship#1870s fashion#victorian#early photography#wales#carmarthenshire

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

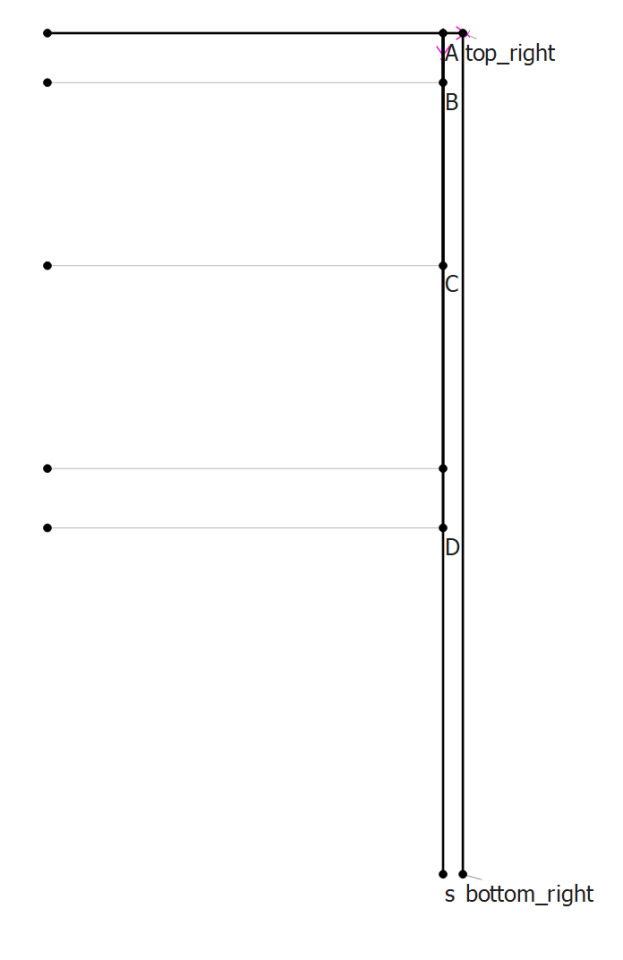

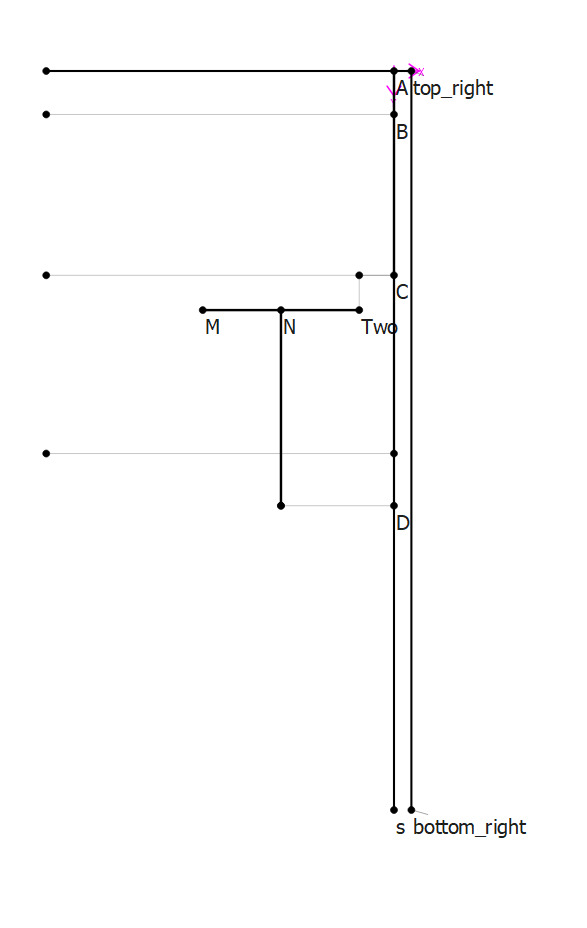

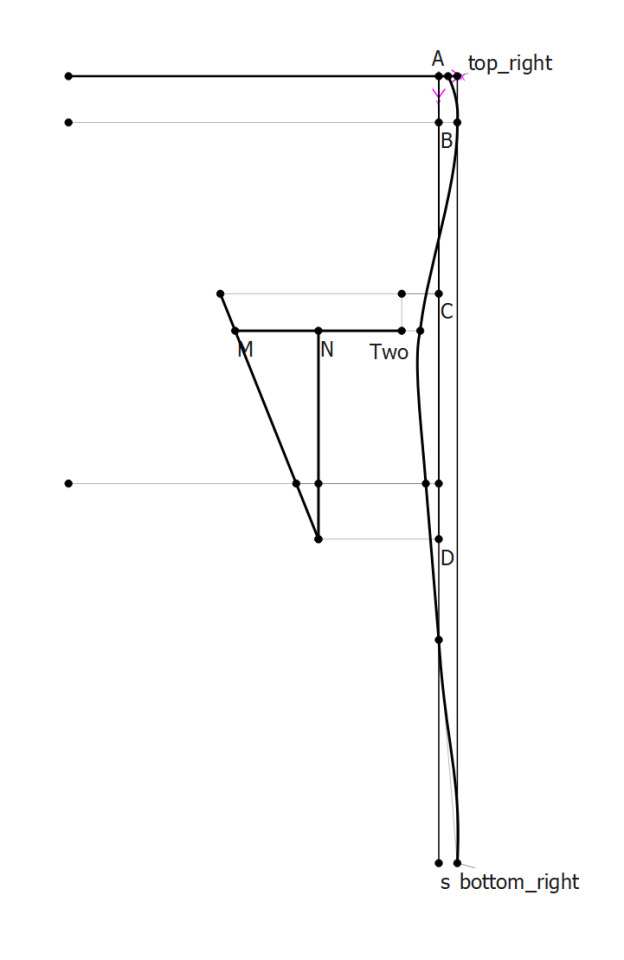

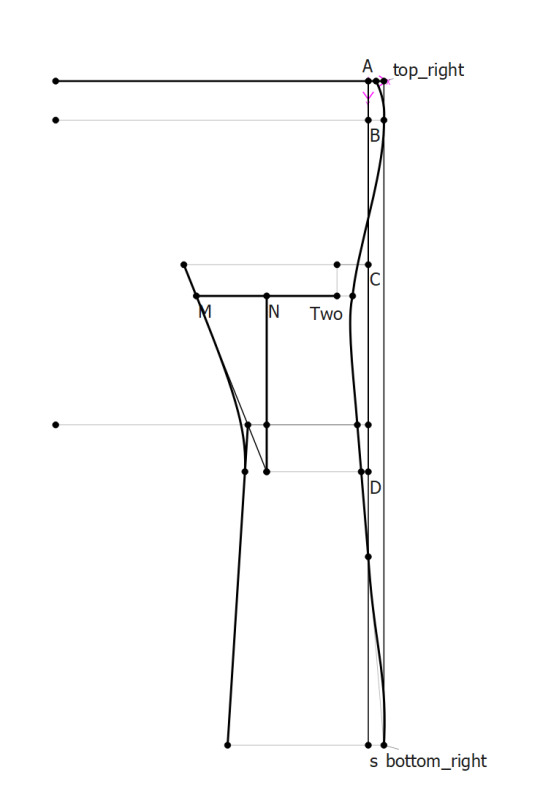

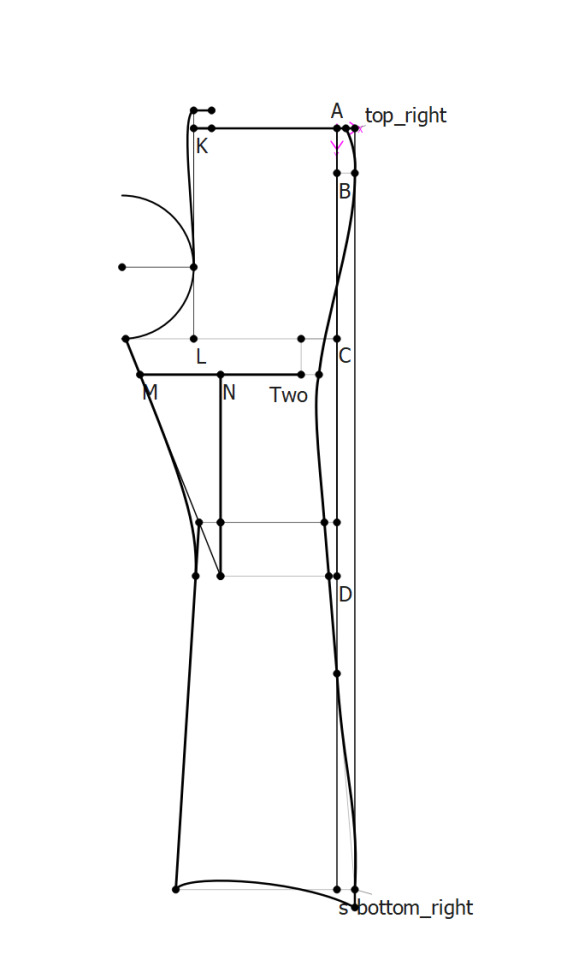

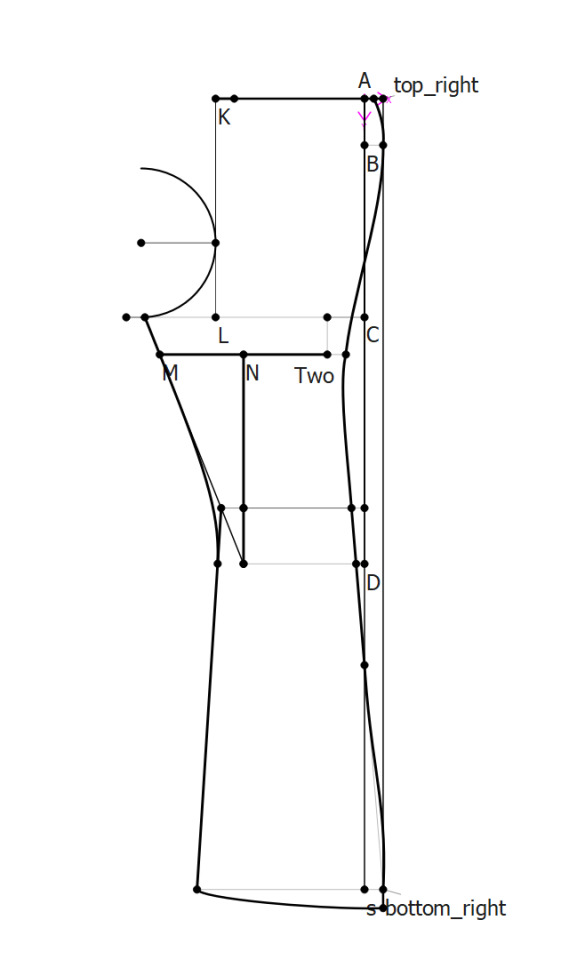

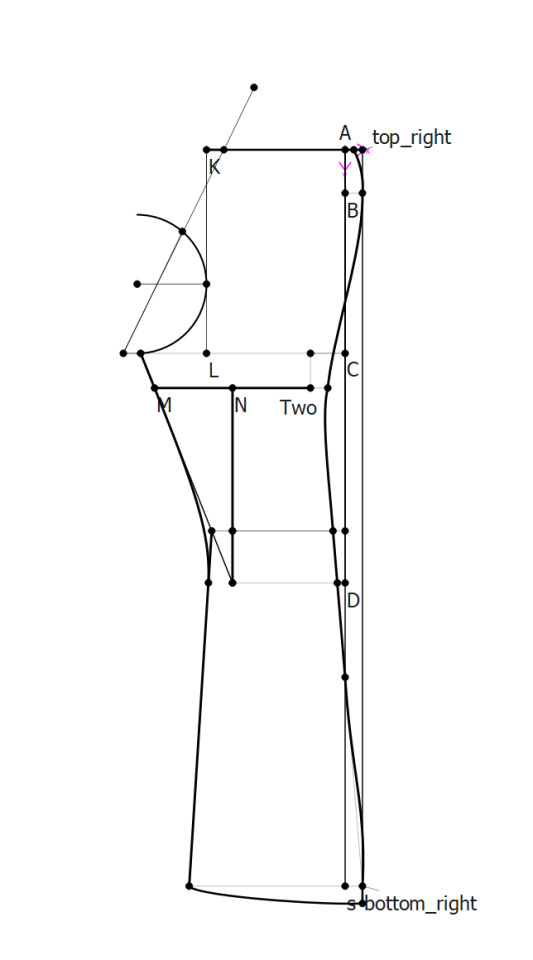

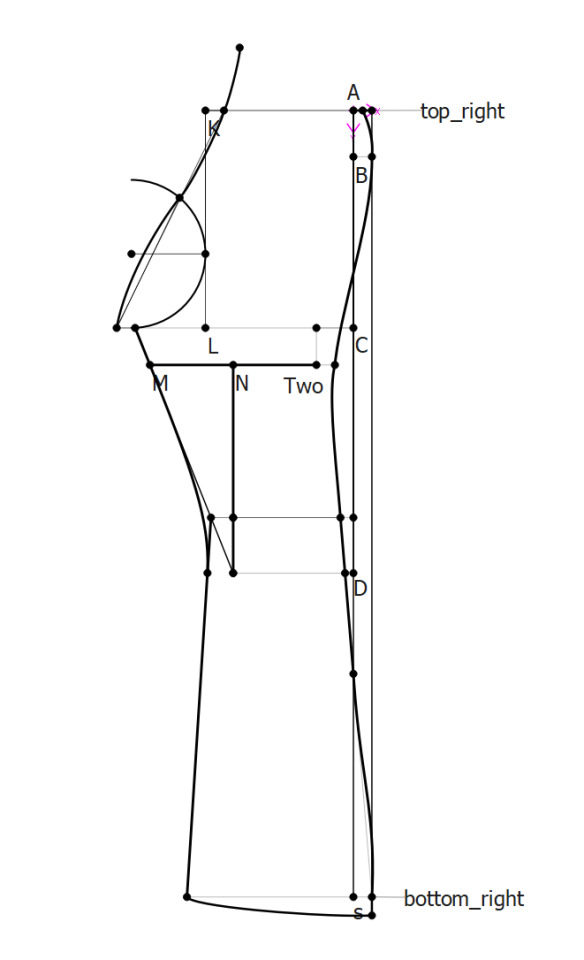

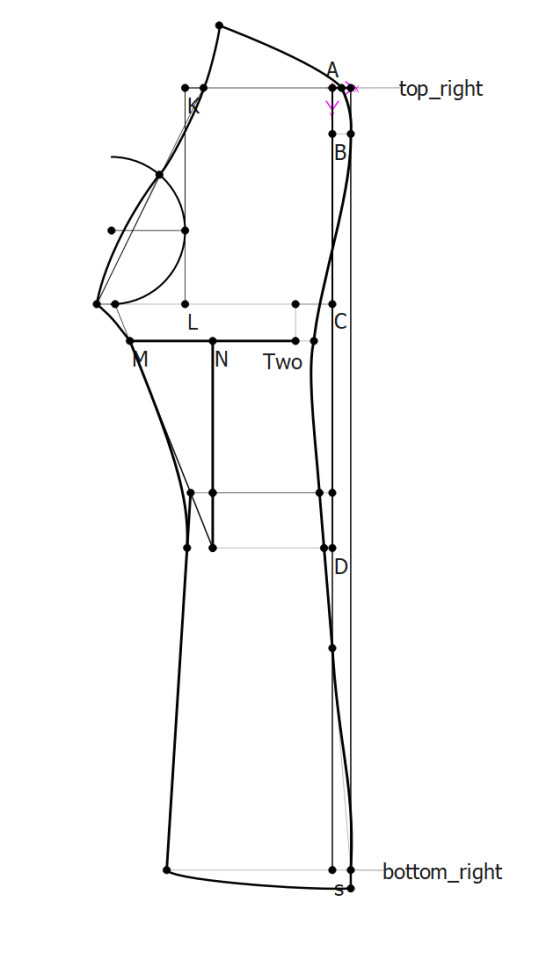

I've spent a while trying to decipher an 1831 tailoring manual (The Improved Tailor's Æra), so here is my actually readable translation of the instructions. (I hope.)

This is my first time doing any pattern drafting, so the instructions from nearly 2 centuries ago weren't all too clear to me, but I'm very excited to try and make my first pair of actual drafted trousers. (Some day, when I have time.)

I had to do a bit of guessing at the top, so let me know if you have any comments on it.

Below are all the instructions and used measurements if anyone is actually interested.

Waist to hip = 'L1' (= 2,5)

Waist to crotch = 'L2' (= 11,75)

Waist to knee = 'L3' (= 25)

Waist to ankle = 'L4' (= 42,5)

Waist width = 'W' (= 18)

Thigh width = 'T' (= 9)

Above Knee w. = 'aK' (= 7)

Knee width = 'K' (= 6,5)

Opening width = 'O' (= 10)

Draw a square line 1 inch (2,5cm) from the edge. The top is A

Measure down and mark the points:

B at 'L1' down from A

C at 'L2' down from A

D at 'L3' down from A

x at '3 inches (7,5cm) up from D'

S at 'L4' down from A

Mark 2 inches (5cm) in and down from C. This is '2

Measure 'T' in from 2. This is 'M'.

Halfway on this line is 'N'.

Draw a square line from N down, until you meet D.

Mark this point.

Draw a line from this point to M and continue it until C.

Mark the intersection with the line above the knee.

Mark the point 'aK' out from this point.

Draw a line from this new mark down to the bottom edge.

Drawing the side seam:

Mark the points (in from the edge):

- 0,5 inch (1,25cm) at A

- 0 inch (1,25cm) at B

- 2,0 inch (5 cm) at 2

- 0,5 inch (1,25cm) at A

Draw a curve resembling the one above through all these marks.

And slightly curve the line at the bottom.

Measure 'O' in from S. Mark this point.

Draw a line from this mark up to the mark above the knee.

Curve this line slightly as shown above.

Measure W in from A. This is 'K'.

Draw a square line down from K to C. This is 'L'.

Mark the point 4 inches (10cm) above L.

Mark the point 4 inches (10cm) in from this point. This is 'R'. (I forgor.)

Draw a 4 inch (10cm) semi-circle from R.

This point is deduced by me, because there are no instructions on this at all.

Draw the fall front:

Mark 1 inch above K. And mark 1 inch out of this point.

Draw a line between these points.

Draw a curve (going slightly out) down to the point above L.

There is supposed to be a line down (and slightly in) from the point right above K, but I have no idea what exact angle that should be.

This is for boots or other tall shoes. (Or just fashion).

Otherwise the pattern before is the completed front trouser pattern.

Measure 1,5 inch (3,75cm) down from the bottom of the edge.

Draw the leg opening as a curve going up.

Now for the back of the trousers. These will be very similar to the front.

Copy (or redraw) the pattern from three images ago.

For boots, keep the point below s, but now draw the curve below.

Measure 1 inch (2,5cm) in from the crotch at C.

Draw a line from this mark to the mark right of K and continue it 3,5 inch (8,75cm) past.

Mark this height.

(I did not do this, but draw a small horizontal line here.)

Draw a curve from the new crotch to the intersection with the semicircle. The amplitude of this curve is 0,5 inch (1,25cm).

Draw a curve from this intersection to the point right of K.

Continue this curve to the top (drawn line).

Note: this will be about 0,5 inch in from the marked point

Again this point just kind of existed on the image, but was nowhere to be found in the text.

Connect the point at the top to the leg seam (0,5 inch out of A) with a slight curve.

This is now the pattern for the back of the trousers.

This is the original image from the book. I think my guesses are pretty reasonable.

#1830s#historical men's fashion#1830s fashion#historical clothing#historical costume#I just spent like 10 hours of my life writing a post no one will ever see :)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why did so many Victorian men look like that? With the questionable facial hair, pained expressions, and silly hats? New transition goal acquired.

0 notes