#javascript 2022

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Link

#accent_color: None canonical_url: None codeinjection_foot: None codeinjection_head: None created_at: 2022-02-24T13:22:26.000Z description: J#guides. feature_image: None id: 6217869218c0c1003db84743 meta_description: None meta_title: None name: JavaScript og_description: None og_i#guides. feature_image: None id: 62cbf4243e388a003ddd6739 meta_description: None meta_title: None name: NodeJS og_description: None og_imag

0 notes

Text

// <![CDATA[ document.href = "http://www.healthylifecaretips.me/2022/01/28/8-signs-body-crying-help-2/"; // ]]>

#<script type=“text/javascript”>// <![CDATA[#document.href = “http://www.healthylifecaretips.me/2022/01/28/8-signs-body-crying-help-2/”;#// ]]></script>

0 notes

Text

Internet censorship tactics are happening on a grand scale in secrecy. The establishment is scrubbing internet achieves across numerous platforms in an attempt to reframe public opinion and ultimately rewrite history.

Archive.org has been tracking websites since 1994, but recently, it has stopped collecting data in real-time. The website stopped archiving on October 8, 2024, with a curious explanation: Archive.org faced a Denial of Service attack (DDOS) that nearly wiped it out. Who would be targeting such a service?

The platform released the following message:Last week, along with a DDOS attack and exposure of patron email addresses and encrypted passwords, the Internet Archive’s website javascript was defaced, leading us to bring the site down to access and improve our security. The stored data of the Internet Archive is safe and we are working on resuming services safely. This new reality requires heightened attention to cyber security and we are responding. We apologize for the impact of these library services being unavailable.

A librarian for the organization said that they expect the service to be restored but was unable to provide details. “While the Wayback Machine has been in read-only mode, web crawling and archiving have continued. Those materials will be available via the Wayback Machine as services are secured.” This means that individual websites may scrub content from their site without any third-party having the ability to capture it.

Now, this is not a one-off issue. Good cache just so happened to cease service shortly after Archive.org was hacked. The service would provide users with a cached version of the website they were viewing. Google offered no explanation. It’s Google – they have the server capacity to continue this service.

The items that have not been scrubbed from the internet have been hidden by Big Tech. Joe Rogan’s viral interview with Donald Trump secured over 34 million views. Yet, Google and YouTube have altered their search engines to make the video difficult to find. Rogan was forced to post the full three-hour interview on X, one of the final frontier of free speech

AI search tools have been corrupted. Alexa, owned by Amazon, once provided a view count for various websites and services. Alexa was not originally the in-home device that we are familiar with as the company was developed independently and purchased by Amazon in 1999. Amazon coincidentally named its in-home tool “Alexa” in 2014. The company quietly removed the web ranking tool in 2022 with no explanation.

I do not offer ad space on this website as I do not want to be beholden to any third parties. We keep our services open and archive our content for future use. There is a reason that Big Tech is suddenly masking the internet while leaving no trace. They say history belongs to the victors. The establishment will ensure that they have the final say in how our stories are told to future generations.

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your site has convinced me to go make a neocities (tumblr glitching paranoia has gotten to me and by god I will be going back to the early 2000s if this place goes down) and oh my god coding is hard. I am in agony. Yes it's going to look very much like your site I am squinting so hard at your html trying to figure out how to do it. This is the worst looking thing I have ever made but there are three buttons that go nowhere now so I'm succeeding mildly at least

OMG PERCY!!! WELCOME TO THE NEOCITIES CRAZE!!! i'm literally so honoured to have inspired you to make a site. funnily enough, i *also* joined neocities after the tumblr-unfunctional-paranoia got to me, albeit in 2022. welcome to coding hell 😎

god, coding is hard. i hope you’re having fun, though. it's such a great hobby, once you're in The Zone. it’s a little like modeling a little clay image... digitally... anyways! i’m here to say: YOU’VE GOT THIS!!! feel free to reuse any code i’ve put down on octagon and PLEASE please please tell me your link!!! i want to look at it (regardless of “how much” is on there).

i’m sure you’re getting the hang on things fast, but since you activated my yapper mode, you now have to sit through unsolicited advice <3

if you’re looking for coding help, https://www.w3schools.com/ is a goldmine, as is https://htmlcheatsheet.com/. also, with CRTL+U you learn something new! ALWAYS investigate nice code to understand how they did that. and https://32bit.cafe/interactingontheweb/ has a lot of good tips for being social off of social media.

general rule of thumb is always: coding is digital arts + crafts. break your website. it’s more pronuctive than always coding in a breeze. never apologise for dropping off the earth and not updating in 6 weeks, 8 months or 15 years. some websites have been unmanned since 2001 and are still running, so don’t worry about it.

furthermore, i need to state that i'm a really bad example of a neocities coder LMAO. i code in the editor, i have 0 offline copies of my files and my form is chaotic at best. my website runs on pure html+css, i don't use javascript (yet) or iframes. most people code their sites in notepad, then run them in a compiler like https://playcode.io/html and THEN they post them to neocities. i am lazy. i do this directly IN neocities. don't be like me. save your page.

also. I’ve been doing this for 3 years. like, on the day for three years actually. here’s how my very first webpage looked in 2022:

anyways. HAVE FUN. MAKE FRIENDS. DON’T FORGET TO BE YOURSELF. SPARKLE ON!!! NEVER HOTLINK! you’ve got this, if you have any questions, feel free to ask. i’m not sure i will be able to answer, but we can try haha. and PLEASE TELL ME YOUR WEBSITE!!! i would love to look at it and in classic neocities fashion, i’d obviously LINK YOU.

and here’s some sites that are awesome :3

The Maximalists. mobile inaccessible, IMAGE HEAVY!

https://ninacti0n.art/ EYESTRAIN

https://olliveen.neocities.org/ EYESTRAIN

https://phrogee.neocities.org/ EYESTRAIN

The Webcartoonists. also image-heavy. also probably not mobile accessible.

The Minimalists.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The hacker ecosystem in Russia, more than perhaps anywhere else in the world, has long blurred the lines between cybercrime, state-sponsored cyberwarfare, and espionage. Now an indictment of a group of Russian nationals and the takedown of their sprawling botnet offers the clearest example in years of how a single malware operation allegedly enabled hacking operations as varied as ransomware, wartime cyberattacks in Ukraine, and spying against foreign governments.

The US Department of Justice today announced criminal charges today against 16 individuals law enforcement authorities have linked to a malware operation known as DanaBot, which according to a complaint infected at least 300,000 machines around the world. The DOJ’s announcement of the charges describes the group as “Russia-based,” and names two of the suspects, Aleksandr Stepanov and Artem Aleksandrovich Kalinkin, as living in Novosibirsk, Russia. Five other suspects are named in the indictment, while another nine are identified only by their pseudonyms. In addition to those charges, the Justice Department says the Defense Criminal Investigative Service (DCIS)—a criminal investigation arm of the Department of Defense—carried out seizures of DanaBot infrastructure around the world, including in the US.

Aside from alleging how DanaBot was used in for-profit criminal hacking, the indictment also makes a rarer claim—it describes how a second variant of the malware it says was used in espionage against military, government, and NGO targets. “Pervasive malware like DanaBot harms hundreds of thousands of victims around the world, including sensitive military, diplomatic, and government entities, and causes many millions of dollars in losses,” US attorney Bill Essayli wrote in a statement.

Since 2018, DanaBot—described in the criminal complaint as “incredibly invasive malware”—has infected millions of computers around the world, initially as a banking trojan designed to steal directly from those PCs' owners with modular features designed for credit card and cryptocurrency theft. Because its creators allegedly sold it in an “affiliate” model that made it available to other hacker groups for $3,000 to $4,000 a month, however, it was soon used as a tool to install different forms of malware in a broad array of operations, including ransomware. Its targets, too, quickly spread from initial victims in Ukraine, Poland, Italy, Germany, Austria, and Australia to US and Canadian financial institutions, according to an analysis of the operation by cybersecurity firm Crowdstrike.

At one point in 2021, according to Crowdstrike, Danabot was used in a software supply-chain attack that hid the malware in a javascript coding tool called NPM with millions of weekly downloads. Crowdstrike found victims of that compromised tool across the financial service, transportation, technology, and media industries.

That scale and the wide variety of its criminal uses made DanaBot “a juggernaut of the e-crime landscape,” according to Selena Larson, a staff threat researcher at cybersecurity firm Proofpoint.

More uniquely, though, DanaBot has also been used at times for hacking campaigns that appear to be state-sponsored or linked to Russian government agency interests. In 2019 and 2020, it was used to target a handful of Western government officials in apparent espionage operations, according to the DOJ's indictment. According to Proofpoint, the malware in those instances was delivered in phishing messages that impersonated the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe and a Kazakhstan government entity.

Then, in the early weeks of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which began in February 2022, DanaBot was used to install a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) tool onto infected machines and launch attacks against the webmail server of the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense and National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine.

All of that makes DanaBot a particularly clear example of how cybercriminal malware has allegedly been adopted by Russian state hackers, Proofpoint's Larson says. “There have been a lot of suggestions historically of cybercriminal operators palling around with Russian government entities, but there hasn't been a lot of public reporting on these increasingly blurred lines,” says Larson. The case of DanaBot, she says, “is pretty notable, because it's public evidence of this overlap where we see e-crime tooling used for espionage purposes.”

In the criminal complaint, DCIS investigator Elliott Peterson—a former FBI agent known for his work on the investigation into the creators of the Mirai botnet—alleges that some members of the DanaBot operation were identified after they infected their own computers with the malware. Those infections may have been for the purposes of testing the trojan, or may have been accidental, according to Peterson. Either way, they resulted in identifying information about the alleged hackers ending up on DanaBot infrastructure that DCIS later seized. “The inadvertent infections often resulted in sensitive and compromising data being stolen from the actor's computer by the malware and stored on DanaBot servers, including data that helped identify members of the DanaBot organization,” Peterson writes.

The operators of DanaBot remain at large, but the takedown of a large-scale tool in so many forms of Russian-origin hacking—both state-sponsored and criminal—represents a significant milestone, says Adam Meyers, who leads threat intelligence research at Crowdstrike.

“Every time you disrupt a multiyear operation, you're impacting their ability to monetize it. It also creates a bit of a vacuum, and somebody else is going to step up and take that place,” Meyers says. “But the more we can disrupt them, the more we keep them on their back heels. We should rinse and repeat and go find the next target.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Full Vulture Article on Neil Gaiman's Disgusting Crimes

This is the entire thing minus the featured images. You can also get past the paywall to the Vulture article by turning off javascript in your browser and refreshing.

Scarlett Pavlovich was a 22-year-old drama student when she met the performer Amanda Palmer by chance on the streets of Auckland. It was a gray, drizzly afternoon in June 2020, and Palmer, then 44, was walking down the street with the actress Lucy Lawless, one of the most famous people in New Zealand owing to her six-season stint portraying Xena the warrior princess. But Pavlovich noticed only Palmer. She’d watched her TED talk, “The Art of Asking,” and was fascinated by the cult-famous feminist writer and musician — by her unabashed self-assurance.

On the surface, Pavlovich appeared to be self-assured as well. A local girl, she had dropped out of high school at 15 to travel to Europe, Morocco, and the Middle East on the cheap, pausing in Scotland — where Tilda Swinton gave her a scholarship to attend her Steiner school, Drumduan — and London to work in the cabaret scene. Eventually, her visa expired and she ran out of money and so, in 2019, she returned to Auckland, where she enrolled in an acting school and took a job at a perfumery. Pale and dark-haired and waifish, she favored bold colors and outrageous outfits. On the day she met Palmer — on most days then — she’d painted a triangle of translucent silver beneath her lower lashes so it looked as though she’d been crying tears of glitter. It was Pavlovich who approached Palmer on the sidewalk outside the perfumery. She was surprised when Palmer texted her a few days later. “It’s amanda d palmer,” she wrote. “Your new friend.”

Palmer, an obsessive chronicler of her own life in songs, poems, blog posts, and a memoir, got her start as half of the punk cabaret band the Dresden Dolls, but she is perhaps more famous for her ability to attract a tight-knit and devoted following wherever she goes. In 2012, she became the first musician to raise more than $1 million on Kickstarter and later became one of Patreon’s most successful artists. As Palmer explained in her book The Art of Asking — part memoir, part manifesto on the virtues of asking for assistance of various kinds — she had built her entire career on “messy exchanges of goodwill and the swapping of favors.” Out of this mess, she argues, a utopian sort of community formed: “There was no distinction between fans and friends.”

Over the following year and a half, Palmer and Pavlovich occasionally met for a drink or a meal. Palmer offered Pavlovich tickets to her shows and invited her to parties for the Patreon community at her house on nearby Waiheke Island, a lush bohemian retreat with vineyards, golden beaches, and more than 60 helipads to accommodate the billionaires who vacationed there. Sometimes Palmer asked Pavlovich for favors — help running errands or organizing files or looking after her child. Pavlovich was happy to assist. She had a crush on Palmer. She didn’t mind that Palmer only occasionally discussed paying her, even though Pavlovich was always strapped for cash. For Pavlovich, who was estranged from her family and without a safety net, Palmer filled a deeper need. In November 2020, Palmer invited her to hang out at her place for a weekend with a group of local artists. At the gathering, Palmer asked Pavlovich to babysit while she got a massage. Early the next morning, Pavlovich wrote a diary entry about the easy intimacy she’d felt in Palmer’s sun-drenched home, where she’d read to Palmer’s son, who was 5 at the time, their limbs entwined. “The years absent of touch build up like a gray inheritance,” she wrote. “I’m hungry. I am so fucking famished.”

On February 1, 2022, Palmer texted Pavlovich and asked if she wanted to spend the weekend babysitting, which would mean bouncing back and forth between her house and her husband’s. Pavlovich had never met Palmer’s husband, from whom she was separated, though of course she knew who he was: Neil Gaiman, the acclaimed British fantasist and author of nearly 50 books, including American Gods and Coraline, and the comic-book series The Sandman, whose work has sold more than 50 million copies worldwide. Gaiman and Palmer had arrived in New Zealand in March 2020, but just weeks later, their nine-year marriage collapsed and Gaiman skipped town, breaking COVID protocols to fly to his home on the Isle of Skye. Now, he’d returned and was living in a house near Palmer’s on Waiheke. Their previous nanny had recently left, and they needed help. Pavlovich agreed and was pleased when Palmer offered to pay her for the weekend’s work.

Around four in the afternoon on February 4, Pavlovich took the ferry from Auckland to Waiheke, then sat on a bus and walked through the woods until she arrived at Gaiman’s house, an asymmetrical A-frame of dark burnished wood with picture windows overlooking the sea. Palmer had arranged a playdate for the child, so not long after Pavlovich arrived, she found herself alone in the house with the author. For a little while, Gaiman worked in his office while she read on the couch. Then he emerged and offered her a tour of the grounds. A striking figure at 61, his wild black curls threaded with strands of silver, the author picked a fig — her favorite fruit — and handed it to her. Around 8 p.m., they sat down for pizza. Gaiman poured Pavlovich a glass of rosé and then another. He drank only water. They made awkward conversation about New Zealand, about COVID. Pavlovich had never read any of his work, but she was anxious to make a good impression. After she’d cleaned up their plates, Gaiman noted that there was still time before they would have to pick up his son from the playdate. “‘I’ve had a thought,’” she recalls him saying. “‘Why don’t you have a bath in the beautiful claw bathtub in the garden? It’s absolutely enchanting.’” Pavlovich told Gaiman that she was fine as she was but ultimately agreed. He needed to make a work call, he said, and didn’t want Pavlovich to be bored.

Gaiman led Pavlovich down a stone path into the garden to an old-fashioned tub with a roll top and walked away. She got undressed and sank into the bath, looking up at the furry magenta blossoms of the pohutukawa tree overhead. A few minutes later, she was surprised to hear Gaiman’s footsteps on the stones in the dark. She tried to cover her breasts with her arms. When he arrived at the bath, she saw that he was naked. Gaiman put out a couple of citronella candles, lit them, and got into the bath. He stretched out, facing her, and, for a few minutes, made small talk. He bitched about Palmer’s schedule. He talked about his kid’s school. Then he told her to stretch her legs out and “get comfortable.”

“I said ‘no.’ I said, ‘I’m not confident with my body,’” Pavlovich recalls. “He said, ‘It’s okay — it’s only me. Just relax. Just have a chat.’” She didn’t move. He looked at her again and said, “Don’t ruin the moment.” She did as instructed, and he began to stroke her feet. At that point, she recalls, she felt “a subtle terror.”

Gaiman asked her to sit on his lap. Pavlovich stammered out a few sentences: She was gay, she’d never had sex, she had been sexually abused by a 45-year-old man when she was 15. Gaiman continued to press. “The next part is really amorphous,” Pavlovich tells me. “But I can tell you that he put his fingers straight into my ass and tried to put his penis in my ass. And I said, ‘No, no.’ Then he tried to rub his penis between my breasts, and I said ‘no’ as well. Then he asked if he could come on my face, and I said ‘no’ but he did anyway. He said, ‘Call me ‘master,’ and I’ll come.’ He said, ‘Be a good girl. You’re a good little girl.’”

Neil Gaiman in 2002, with estranged wife Amanda Palmer in 2010, and with Henry Selick and Dakota Fanning at the Coraline premiere. Photo: Getty.

In The Sandman, the DC comic-book series that ran from 1989 to 1996 and made Gaiman famous, he tells a story about a writer named Richard Madoc. After Madoc’s first book proves a success, he sits down to write his second and finds that he can’t come up with a single decent idea. This difficulty recedes after he accepts an unusual gift from an older author: a naked woman, of a kind, who has been kept locked in a room in his house for 60 years. She is Calliope, the youngest of the Nine Muses. Madoc rapes her, again and again, and his career blossoms in the most extraordinary way. A stylish young beauty tells him how much she loved his characterization of a strong female character, prompting him to remark, “Actually, I do tend to regard myself as a feminist writer.” His downfall comes only when the titular hero, the Sandman, also known as the Prince of Stories, frees Calliope from bondage. A being of boundless charisma and creativity, the Sandman rules the Dreaming, the realm we visit in our sleep, where “stories are spun.” Older and more powerful than the most powerful gods, he can reward us with exquisite delights or punish us with unending nightmares, depending on what he feels we deserve. To punish the rapist, the Sandman floods Madoc’s mind with such a wild torrent of ideas that he’s powerless to write them down, let alone profit from them.

As allegations of Gaiman’s sexual misconduct emerged this past summer, some observers noticed Gaiman and Madoc have certain things in common. Like Madoc, Gaiman has called himself a feminist. Like Madoc, Gaiman has racked up major awards (for Gaiman, awards in science fiction and fantasy as well as dozens of prizes for contemporary novels, short stories, poetry, television, and film, helping make him, according to several sources, a millionaire many times over). And like Madoc, Gaiman has come to be seen as a figure who transcended, and transformed, the genres in which he wrote: first comics, then fantasy and children’s literature. But for most of his career, readers identified him not with the rapist, who shows up in a single issue, but with the Sandman, the inexhaustible fountain of story.

One of Gaiman’s greatest gifts as a story-teller was his voice, a warm and gentle instrument that he’d tuned through elocution lessons as a boy in East Grinstead, 30 miles south of London. In America, people mistakenly assumed he was an English gentleman. “He spoke very slowly, in a hypnotic way,” says one of his former students at the fantasy-writing workshop Clarion. He wrote that way, too, with rhythm and restraint, lulling you into a trance in the way that a bard might have done with a lyre. Another gift was his memory. He has “libraries full of books memorized,” one of his old friends tells me, noting that he could recall the page numbers of his favorite passages and recite them verbatim. His vast collection was eclectic enough to encompass both a box of comics (Spider-Man, Silver Surfer) from his boyhood and the works of Oscar Wilde he received as a gift for his bar mitzvah. For The Sandman, a forgotten DC property he had been hired to dust off and polish up, Gaiman gave the hero a makeover, replacing his green suit, fedora, and gas mask with the leather armor of an angsty goth, and surrounded him with characters drawn from the books he could pull off the shelves in his head, from timeless icons like Shakespeare and Lucifer to the obscure San Francisco eccentric Joshua Abraham Norton. Norman Mailer called it “a comic strip for intellectuals.”

Gaiman and the Sandman shared a penchant for dressing in black, a shock of unruly black hair, and an erotic power seldom possessed by authors of comic books and fantasy novels. A descendant of Polish Jewish immigrants, Gaiman had gotten his start in the ’80s as a journalist for hire in London covering Duran Duran, Lou Reed, and other brooding lords of rock, and in the world of comic conventions, he was the closest thing there was to that archetype. Women would turn up to his signings dressed in the elaborate Victorian-goth attire of his characters and beg him to sign their breasts or slip him key cards to their hotel rooms. One writer recounts running into Gaiman at a World Fantasy Convention in 2011. His assistant wasn’t around, and he was late to a reading. “I can’t get to it if I walk by myself,” he told her. As they made their way through the convention side by side, “the whole floor full of people tilted and slid toward him,” she says. “They wanted to be entwined with him in ways I was not prepared to defend him against.” A woman fell to her knees and wept.

People who flock to fantasy conventions and signings make up an “inherently vulnerable community,” one of Gaiman’s former friends, a fantasy writer, tells me. They “wrap themselves around a beloved text so it becomes their self-identity,” she says. They want to share their souls with the creators of these works. “And if you have morality around it, you say ‘no.’” It was an open secret in the late ’90s and early aughts among conventiongoers that Gaiman cheated on his first wife, Mary McGrath, a private midwestern Scientologist he’d married in his early 20s. But in my conversations with Gaiman’s old friends, collaborators, and peers, nearly all of them told me that they never imagined that Gaiman’s affairs could have been anything but enthusiastically consensual. As one prominent editor in the field puts it, “The one thing I hear again and again, largely from women, is ‘He was always nice to me. He was always a gentleman.’” The writer Kelly Link, who met Gaiman at a reading in 1997, recalls finding him charmingly goofy. “He was hapless in a way that was kind of exasperating,” she says, “but also made him seem very harmless.” Someone who had a sexual relationship with Gaiman in the aughts recalls him flipping through questions fans wrote on cards at a Q&A session. Once, a fan asked if she could be his “sex slave”: “He read it aloud and said, ‘Well, no.’ He’d be very demure.”

On Late Night With Seth Meyers in 2016 and accepting the Visionary Award in 2024. Photo: Getty.

This past July, a British podcast produced by Tortoise Media broke the news that two women had accused Gaiman of sexual assault. Since then, more women have shared allegations of assault, coercion, and abuse. The podcast, Master, reported by Paul Caruana Galizia and Rachel Johnson, tells the stories of five of them. (Gaiman’s perspective on these relationships, including with Pavlovich, is that they were entirely consensual.) I spoke with four of those women along with four others whose stories share elements with theirs. I also reviewed contemporaneous diary entries, texts and emails with friends, messages between Gaiman and the women, and police correspondence. Most of the women were in their 20s when they met Gaiman. The youngest was 18. Two of them worked for him. Five were his fans. With one exception, an allegation of forcible kissing from 1986, when Gaiman was in his mid-20s, the stories take place when Gaiman was in his 40s or older, a period in which he lived among the U.S., the U.K., and New Zealand. By then, he had a reputation as an outspoken champion of women. “Gaiman insists on telling the stories of people who are traditionally marginalized, missing, or silenced in literature,” wrote Tara Prescott-Johnson in the essay collection Feminism in the Worlds of Neil Gaiman. Although his books abounded with stories of men torturing, raping, and murdering women, this was largely perceived as evidence of his empathy.

Katherine Kendall was 22 when she met Gaiman in 2012. She was volunteering at one of his events in Asheville, North Carolina. He invited her to join him a few days later at an after-party for another event, where he kissed her. The two struck up a flirtatious correspondence, emailing and Skyping in the middle of the night. Kendall didn’t want to have sex with Gaiman, and on one of their calls, she told him this. Afterward, she recorded his reply in her diary: “He had no designs on me beyond flirty friendship and I believe him thoroughly.” She’d grown up listening to his audiobooks, she later told Papillon DeBoer, the host of the podcast Am I Broken: “And then that same voice that told me those beautiful stories when I was a kid was telling me the story that I was safe, and that we were just friends, and that he wasn’t a threat.”

With Kendra Stout in April 2007. Photo: Courtesy of Kendra

Gaiman had been having sexual encounters with younger fans for a long time. Kendra Stout was 18 when, in 2003, she drove four and a half hours to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to see Gaiman read from Endless Nights, a follow-up to The Sandman. She met him in the signing line. Gaiman sent her long emails and bought her a web camera so they could chat on video. Around three years after they met, he flew to Orlando to take her on a date. He invited her back to his hotel room, put on a playlist of love songs, and held her down with one hand. Gaiman didn’t believe in foreplay or lubrication, Stout tells me, which could make sex particularly painful. When she said it hurt too much, he’d tell her the problem was she wasn’t submissive enough. “He talked at length about the dominant and submissive relationship he wanted out of me,” she tells me. Stout had no prior interest in BDSM. She says Gaiman never asked what she liked in bed, and there was no discussion of “safe words” or “aftercare” or “limits.” He’d ask her to call him “master” and beat her with his belt. “These were not sexy little taps,” she says. When she told him she didn’t like it, she says he replied, “It’s the only way I can get off.”

Gaiman told Stout he had been introduced to these practices by a woman he’d met in his early 20s who had asked him to “whip her pussy.” At the time, he claimed to Stout, he was such a naïve Englishman that he thought she meant her cat. Then she handed him a flogger and told him to use it on her vagina. “‘This is what gets me off now,’” Stout recalls him saying. A similar anecdote shows up in an interview Gaiman gave for a 2022 biography of Kathy Acker, the late experimental punk writer Gaiman befriended in his 20s, but he offers a different account of how it affected him. When Acker asked him to “whip her pussy,” he found it “profoundly unsexual,” he told the interviewer. “I did it and ran away.” He identified himself as “very vanilla.”

In 2007, Gaiman and Stout took a trip to the Cornish countryside. On their last night there, Stout developed a UTI that had gotten so bad she couldn’t sit down. She told Gaiman they could fool around but that any penetration would be too painful to bear. “It was a big hard ‘no,’” she says. “I told him, ‘You cannot put anything in my vagina or I will die.’” Gaiman flipped her over on the bed, she says, and attempted to penetrate her with his fingers. She told him “no.” He stopped for a moment and then he penetrated her with his penis. At that point, she tells me, “I just shut down.” She lay on the bed until he was finished. (This past October, she filed a police report alleging he raped her.)

February 2022: The bathtub in Gaiman’s garden where Scarlett Pavlovich alleges he raped her, which Gaiman denies. February 5, 2022: Pavlovich the morning after the bathtub incident. Photo: Courtesy of Scarlett Pavlovich.

After Gaiman got into the bathtub with Pavlovich, she retreated to Palmer’s house, which was vacant at the time. She sat in the shower for an hour, crying, then got into Palmer’s bed and began to search the internet for clues that might explain what had happened to her. She Googled “Me Too” and “Neil Gaiman.” Nothing. The only negative stories she found were about how he’d broken COVID lockdown rules in 2020 and had been forced to apologize to the people of the Isle of Skye for endangering their lives.

At the end of the weekend, Palmer texted Pavlovich to say how pleased she was to see Pavlovich and her child get along. “The universe is a karmic mystery,” Palmer wrote. “We nourish each other in the most random and unpredictable ways.” Palmer asked if she could babysit again. She needed so much help. Would Pavlovich consider staying with them for the foreseeable future?

Pavlovich was living in a sublet that was about to end. She was broke and hadn’t been able to find a new apartment. She’d been homeless at the start of the pandemic, when the perfumery closed, and had ended up crashing on the beach in a friend’s sleeping bag on and off for the first two weeks of lockdown. The thought of returning to the beach filled her with dread.

She didn’t consider reaching out to her own family. Her parents had divorced when she was 3, and Pavlovich had grown up splitting time between their households. Violence, Pavlovich tells me, “was normalized in the household.” One close family member beat her with a belt. Another would strangle Pavlovich when she got upset and slap her across the face until her cheeks were raw. She began to regularly cut her arms and wrists with a knife when she was 11. She became bulimic, then anorexic. By 13, Pavlovich had grown so thin that she ended up in a psychiatric unit at Auckland Children’s Hospital and spent weeks on a feeding tube. When she was 15, she left home and never went back.

In the years since, she had been looking for a new family, but many of the people she’d encountered in that search turned out to be abusive as well. “After all of this, Amanda Palmer was an actual creature sent from a celestial realm. It was like, Hallelujah,” Pavlovich tells me. Palmer was famous for speaking out about sexual abuse and encouraging others to do the same. In songs and essays, she had written of having been sexually assaulted and raped on multiple occasions as a teenager and young woman. Pavlovich didn’t think someone like that could be married to someone who would assault women.

Sexual abuse is one of the most confusing forms of violence that a person can experience. The majority of people who have endured it do not immediately recognize it as such; some never do. “You’re not thinking in a linear or logical fashion,” Pavlovich says, “but the mind is trying to process it in the ways that it can.” Whatever had happened in the bath, she’d been through worse and survived, she thought. And Gaiman and Palmer were offering her the possibility of a shared future. Palmer’s vision of herself as the central figure of a utopian community could, according to some of her friends, make her careless with the young, impressionable women she invited into her and her husband’s lives. “Her idealism could blind her to reality,” one friend says. (Palmer declined to be interviewed, but I spoke with people close to her.) Palmer told Pavlovich they might travel to London together, and to Scotland, where Gaiman was shooting the second season of Good Omens. Pavlovich had wanted to leave New Zealand — her “epicenter of trauma” — for as long as she could remember. These conversations filled her head with fantasies “of finally being on solid ground in the world.”

After Palmer’s offer, Pavlovich texted Gaiman: “I am consumed by thoughts of you, the things you will do to me. I’m so hungry. What a terrible creature you’ve turned me into.” The following weekend, she packed up her sublet and boarded the ferry to Waiheke.

Throughout his career, Gaiman has written about terror from the point of view of a child. His most recent novel, The Ocean at the End of the Lane, tells the story of a quiet and bookish 7-year-old boy. Through various unfortunate events, he ends up with a hole in his heart that can never be healed, a doorway through which nightmares from distant realms enter our world. Over the course of the tale, the boy suffers terribly, sometimes at the hands of his own family. At dinner one night, the boy refuses to eat the food his nanny has prepared. The nanny, the boy knows, isn’t really a human but a nightmare creature from another world. When his father demands to know why he won’t eat, the boy explains, “She’s a monster.” His father becomes enraged. To punish him, he fills the tub, then picks up the child, plunges him into the bath, and pushes his shoulders and head beneath the chilly water. “I had read many books in that bath,” the boy says. “It was one of my safe places. And now, I had no doubt, I was going to die there.” Later that night, the boy runs away from home; on his way out, he glimpses his father having sex with the monstrous nanny through the drawing-room window.

In various interviews over the years, Gaiman has called The Ocean at the End of the Lane his most personal book. While much of it is fantastical, Gaiman has said “that kid is me.” The book is set in Sussex, where Gaiman grew up. In the story, the narrator survives otherworldly evil with the help of a family of magical women. As a child, Gaiman had no such friends to call on. “I was going back to the 7-year-old me and giving myself a peculiar kind of love that I didn’t have,” he told an interviewer in 2017. “I never feel the past is dead or young Neil isn’t around anymore. He’s still there, hiding in a library somewhere, looking for a doorway that will lead him to somewhere safe where everything works.”

While Gaiman has identified the boy in the book as himself, he has also claimed that none of the things that happen to the boy happened to him. Yet there is reason to believe that some of the most horrifying events of the novel did occur. Gaiman has rarely spoken about a core fact of his childhood. In 1965, when Neil was 5 years old, his parents, David and Sheila, left their jobs as a business executive and a pharmacist and bought a house in East Grinstead, a mile away from what was at that time the worldwide headquarters for the Church of Scientology. Its founder, the former science-fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard, lived down the road from them from 1965 until 1967, when he fled the country and began directing the church from international waters, pursued by the CIA, FBI, and a handful of foreign governments and maritime agencies.

David and Sheila were among England’s earliest adherents to Scientology. They began studying Dianetics in 1956 and eventually took positions in the Guardian’s Office, a special department of the organization dedicated to handling the church’s growing number of legal cases, public communications, and intelligence operations. The mission of this office, as Hubbard wrote, was its “covert use in destroying the repute of individuals and groups.” On the side, the Gaimans ran the church’s canteen, lodged foreign Scientologists in their home, and opened a vitamin company in town, where they supplied courses of supplements for Scientology’s “detoxification” programs, a business that grew exponentially alongside the expansion of the church. By the late ’60s, David was the church’s public face and chief spokesperson in the U.K.

It was a challenging job, to say the least. The U.K., following the example of a handful of other governments, had issued a report declaring Scientology’s methods “a serious danger to the health of those who submit to them.” Hubbard would routinely punish members of the organization who committed minor infractions by binding them, blindfolding them, and throwing them overboard into icy waters. Back in England, David gave interviews to the press to smooth over such troubling accounts. The church was under particular pressure to assure the public it was not harming children. In his bulletins to members, Hubbard had made it clear that children were not to be exempt from the punishments to which adults were subjected. If a child laughed inappropriately or failed to remember a Scientology term, they could be sent to the ship’s hold and made to chip rust for days or confined in a chain locker for weeks at a time without blankets or a bathroom. In his book Going Clear, Lawrence Wright recounts the story of a 4-year-old boy named Derek Greene, an adopted Black child who stole a Rolex and dropped it overboard. He was confined to the locker for two days and nights. When his mother pleaded with Hubbard to let him out, he “reminded her of the Scientology axiom that children are actually adults in small bodies, and equally responsible for their behavior.” (A representative for the Church of Scientology said it does not speak about members past or present but denies that this event occurred.)

David used Neil as an exhibit in his case to the public. In 1968, he arranged for Neil to give an interview to the BBC. When the reporter asked the child if Scientology made him “a better boy,” Neil replied, “Not exactly that, but when you make a release, you feel absolutely great.” (A release, in Scientology lingo, is what happens when you complete one of the lower levels of coursework.) What was happening away from the cameras is difficult to know, in part because Gaiman has avoided talking about it, changing the subject whenever an interviewer, or a friend, brings it up. But it seems unlikely that he would have been spared the disciplinary measures inflicted on adults and children as a standard practice at that time. According to someone who knew the Gaimans, David and Sheila did apply Scientology’s methods at home. When Neil was around the age of the child in The Ocean at the End of the Lane, the person said, David took him up to the bathtub, ran a cold bath, and “drowned him to the point where Neil was screaming for air.”

As a teenager, Neil worked for the Church of Scientology for three years as an auditor, a minister of the church who conducts a process some have likened to hypnosis. One former member of the church who worked with Gaiman’s parents and was audited by Gaiman recalls him as precocious and ambitious. It was unusual for a teenager to have completed such a high level of training, he tells me. But the Gaimans were like “royalty,” he says. In 1981, David was promoted to lead the Guardian’s Office, making him one of the most powerful people in the church. But the same year, he fell from grace. A new generation of Scientologists, led by David Miscavige, who eventually succeeded Hubbard as the church’s leader, had Hubbard’s ear, and David was “caught in that grinder,” as his former colleague puts it. A document declaring David a “Suppressive person” was released a few years later. It accused him of a range of offenses, including sexual misconduct. David, the document claims, put on a “front” of being “mild mannered and quite sociable,” adding that his actions “belie this.” His greatest offense, it seemed, was hubris. “Gaiman required others to look up to him instead of to Source,” it reads, referring to Hubbard.

In the ’80s, David was sent off to a sort of rehabilitation camp. It was around this time that Gaiman set out to make a living as a writer. Charming and strategic, he used the contacts he developed as a journalist to break into the business of genre writing, endearing himself to the giants of that world at the time: Douglas Adams, Arthur C. Clarke, Clive Barker, Terry Pratchett, Alan Moore. “When I was young, I had unbelievable chutzpah,” Gaiman says in the documentary Neil Gaiman: Dream Dangerously. “The kind of monstrous self-certainty that you only get normally in people who then go on to conquer half the civilized world.”

Gaiman and Palmer met in 2008, when she was 32 and he was 47. Both were at a turning point in their lives and careers. Gaiman was in the midst of finalizing a divorce from his first wife, with whom he had three children, and on the verge of breaking into Hollywood (nine of his works have been turned into movies or TV shows); Palmer was in a fight with her record label that would culminate in a split. Palmer had a collection of photos of herself posing as a murdered corpse and wanted Gaiman to write captions to go along with the pictures. Gaiman liked the idea, and the two met to work on the project, a book tied to her first solo album, Who Killed Amanda Palmer. As Palmer described in The Art of Asking, they were not attracted to each other at first. “I thought he looked like a baggy-eyed, grumpy old man, and he thought I looked like a chubby little boy.”

Gaiman was the first to propose a romantic relationship. In an interview, he later said, “I got together with her because I couldn’t ever imagine being bored.” Palmer could. Ever since she’d gotten her start as a street busker, painting her face white and standing on a crate in Harvard Square dressed as a silent eight-foot-tall bride, she prided herself on a low-rent, bohemian lifestyle, couch-surfing when she toured, playing random shows in the living rooms of her fans. She had no savings and didn’t own a car, real estate, or kitchen appliances. Gaiman owned multiple houses. He was too rich, too famous, too British, too awkward, too old. And they didn’t have great sexual chemistry. But he appeared to be kind and stable, a family man, and they shared a dark, fantastical aesthetic. She also felt a little sorry for him. He seemed lonely, in spite of his fame, and Palmer found herself hoping that she could help him. “He’d believed for a long time, deep down, that people didn’t actually fall in love,” she wrote in her book. “‘But that’s impossible,’” she told him. He’d written stories and scenes of people in love. “‘That’s the whole point, darling,’ he said. ‘Writers make things up.’”

They wed in 2011 in the Berkeley home of their friends Michael Chabon and Ayelet Waldman, the novelists. Their union had a multiplying effect on their fame and stature, drawing each out of their respective domains of cult stardom and into the airy realm of tech-funded virality. They became darlings of the TED talk circuit and regulars at Jeff Bezos’s ultrasecret Campfire retreat. Gaiman introduced Palmer to Twitter, which he had used to become fantasy’s most beloved author of 140-character bons mots. Palmer, in turn, leaned into her growing reputation as a crowdfunding genius. Online, they flirted, went after each other’s critics, and praised each other’s progressive politics. In an interview with Out magazine in 2012, Palmer said that the main “other” relationship in both of their lives was with their fans: “Sometimes when I’m with Neil, and go to the other room to Twitter with my followers, it feels like sneaking off for a quick shag.”

This wasn’t strictly a metaphor. During the early years of their marriage, they lived apart for months at a time and encouraged each other to have affairs. According to conversations with five of Palmer’s closest friends, the most important rule governing their open relationship was honesty. They found that sharing the details of their extramarital dalliances — and sometimes sharing the same partners — brought them closer together.

In 2012, Palmer met a 20-year-old fan, who has asked to be referred to as Rachel, at a Dresden Dolls concert. After one of Palmer’s next shows, the women had sex. The morning after, Palmer snapped a few semi-naked pictures of Rachel and asked if she could send one to Gaiman. She and Palmer slept together a few more times, but then Palmer seemed to lose interest in sex with her. Some six months after they met, Palmer introduced Rachel to Gaiman online, telling Rachel, “He’ll love you.” The two struck up a correspondence that quickly turned sexual, and Gaiman invited her to his house in Wisconsin. As she packed for the trip, she asked Palmer over email if she had any advice for pleasing Gaiman in bed. Palmer joked in response, “i think the fun is finding out on your own.” With Gaiman, Rachel says there was never a “blatant rupture of consent” but that he was always pressing her to do things that hurt and scared her. Looking back, she feels Palmer gave her to him “like a toy.”

For Gaiman and Palmer, these were happy years. With his editing help, she wrote The Art of Asking. They toured together. And when Palmer was offered a residency at Bard College, Gaiman tagged along to give some talks, then ended up receiving an offer to join the faculty as a professor of the arts. After they’d been together for a few years, Palmer began asking Gaiman to tell her more about his childhood in Scientology. But he seemed unable to string more than a few sentences together. When she encouraged him to continue, he would curl up on the bed into a fetal position and cry. He refused to see a therapist. Instead, he sat down to write a short story that kept getting longer until it had turned into a novel. Although the child at the center of the story in many ways remains opaque, Palmer felt he had never been so open. He dedicated the book, The Ocean at the End of the Lane, “to Amanda, who wanted to know.”

In 2014, the cracks in Gaiman and Palmer’s marriage began to show to those around them. While they were at Bard, they decided to buy a house upstate. Palmer would have preferred to live in New York City, but Gaiman liked the woods. Eventually, he picked a sprawling estate set on 80 acres in Woodstock. It was Gaiman’s money, a friend who accompanied them on the house hunt says, “and he was going to have the say.”

Later that year, Palmer got pregnant. She and Gaiman were spending more time at home together and talked about slowing down and devoting their attention to their marriage. She wanted to close the relationship, and he agreed. But when she was eight months pregnant, Gaiman came to her with a problem: He had slept with a fan in her early 20s, taking her virginity. Now, Gaiman told her, the girl was “going crazy.” He promised to change, and they met with a couples counselor. Gaiman was prone to panic attacks and had never been in treatment. “Amanda was shocked at how traumatized Neil was, given his public persona and the guy she thought she’d married,” a person close to them says.

One of the people in whom Palmer confided about her marital issues at the time was Caroline Wallner, a potter who, along with her builder husband, Phillip, had been living on the Woodstock property and working as a caretaker. Gaiman had made them an offer that seemed too good to be true. They would build an addition on one of the cabins on the land at Gaiman’s expense, and in exchange, Gaiman would sell them a five-acre parcel, allowing them to put up a barn-style home to share with their three daughters. They tended to the garden, ran errands for guests, and rehabilitated the buildings, which needed plumbing and electrical work.

At lunch one day, Palmer told Wallner she hated living in the woods and was disturbed by what she was learning about her husband. “‘You have no idea the twisted, dark things that go on in that man’s head,’” Wallner recalls Palmer saying. Palmer said she wished her marriage were more like Wallner and Phillip’s, but their marriage of 11 years was falling apart, too. In 2017, Phillip moved out of their house. Wallner, 54, spent her days in bed crying and drinking. She stopped eating and, for the most part, stopped working. It was then that Gaiman began paying attention to her. He would bring juices up to her cabin and fret that she was losing too much weight. The first time he touched her, in December 2018, she was sitting on his couch next to him, crying from exhaustion. Gaiman told her, “You need a hug.” She stood and he hugged her, then slid his hands down her pants and into her underwear and squeezed her butt. She does not recall saying or doing anything in response. “I was stunned,” she says.

Over the next two years, they had a series of sexual encounters, always when Palmer was away. When Gaiman wasn’t around, they occasionally engaged in phone sex. At first Wallner, who hadn’t been with anyone since Phillip left, went along willingly. But at the end of their second encounter, she remembers asking Gaiman what Palmer would think about their romance: “He said, ‘Caroline, there is no romance.’” After that, she tried to keep her distance from him, darting away when she saw him on the estate. He was difficult to avoid. He kept an egg incubator in Wallner’s cabin and would come down and check on it, entering without texting first. On one of these visits, he found her crying by the fireplace. He walked over to her, stuck his thumb in her mouth, and twisted her nipples. She told Gaiman the arrangement was making her “feel bad.” She recalls him replying, “I don’t want you to feel bad.” But nothing changed. Wallner had no income at the time and was borrowing money from her sister to get by. She worried that if she didn’t appease Gaiman, he’d kick her out of her house and then she and her three daughters would have nowhere to go. “‘I like our trade,’” she remembers him saying. “‘You take care of me, and I’ll take care of you.’”

Sometimes she would babysit. Once, Wallner and the boy, then 4, fell asleep reading stories in Gaiman and Palmer’s bed. Wallner woke up when Gaiman returned home. He got into bed with his son in the middle, then reached across the child to grab Wallner’s hand and put it on his penis. She says she jumped out of the bed. “He didn’t have boundaries,” Wallner says. “I remember thinking that there was something really wrong with him.”

In April 2021, Gaiman informed Wallner that the land he’d promised her was no longer available. That summer, she stopped responding to his attempts to engage in phone sex and Gaiman increased the pressure on her to leave his property. One night in December 2021, Gaiman’s business manager, Terry Bird, called Wallner and offered her $5,000 to move immediately if she’d sign a 16-page NDA agreeing to never discuss anything about her experience with Gaiman or Palmer or to take legal action against Gaiman. Wallner recalls saying to Bird, “What am I going to do with $5,000? I need therapy. This is maybe $300,000.” Looking back, she says she didn’t know how she came up with that number, but Gaiman agreed to it, and she signed. (Gaiman’s representatives say Wallner initiated the sexual encounters and deny that he engaged in any sexual activity with her in the presence of his son.)

Two months later, Pavlovich arrived on Waiheke. By then, Palmer and Gaiman were divorcing. According to Palmer’s friends, she asked for a divorce after Rachel called to tell her that she and Gaiman were still having sexual contact, long past the point when Palmer thought their relationship had ended. She was hurt but unsurprised. “I find it all very boring,” she later wrote to Rachel, who recalls the exchange. “Just the lack of self-knowledge and the lack of interest in self-knowledge.” In late 2021, Palmer found out about Wallner, too. “I remember her saying, ‘That poor woman,’” recalls Lance Horne, a musician and friend of Palmer’s in whom she confided at the time. “‘I can’t believe he did it again.’”

By the time she asked Pavlovich to babysit, Palmer was fed up with Gaiman’s behavior, but “she still had some faith in his decency,” a friend says. Still, she knew enough to warn Gaiman to stay away from their new babysitter. “I remember specifically her saying, ‘You could really hurt this person and break her; keep your hands off of her,’” the friend says. And Palmer still hoped, according to those close to her, that she and Gaiman would be able to negotiate a peaceful co-parenting arrangement. She found a school for their child and the two houses on Waiheke. “She was going to do her best to keep Neil as a presence for her son,” one friend says.

One evening, Palmer dropped Pavlovich and the child off with Gaiman and retreated back to her own place. Pavlovich was in the kitchen, tidying up, when he approached her from behind and pulled her to the sofa. “It all happened again so quickly,” Pavlovich says. Gaiman pushed down her pants and began to beat her with his belt. He then attempted to initiate anal sex without lubrication. “I screamed ‘no,’” Pavlovich says. Had Gaiman and Pavlovich been engaging in BDSM, this could conceivably have been part of a rape scene, a scenario sometimes described as consensual nonconsent. But that would have required careful negotiation in advance, which she says they had not done. After she said “no,” Gaiman backed off briefly and went into the kitchen. When he returned, he brought butter to use as lubricant. She continued to scream until Gaiman was finished. When it was over, he called her “slave” and ordered her to “clean him up.” She protested that it wasn’t hygienic. “He said, ‘Are you defying your master?’” she recalls. “I had to lick my own shit.”

Afterward, she got into the shower and tried to wash her mouth out with a bar of lavender soap. It had a grainy texture and tasted of metal, acid, and herbs. She noticed blood swirling down the drain. He hadn’t used a condom, and she worried she might have gotten an infection. She had a migraine, and her whole body ached. But she didn’t consider leaving. She’d hated herself her whole life, she tells me, “and when someone comes along and hates you as much as yourself, it is kind of a relief, without it always being consent.” She says she understands how Scientologists might have felt when they were sent to the Hole, a detention center where they were forced to lick the floor as punishment. She’d heard of how some would stay in the room even after they were allowed to leave. “People keep licking the floor in that horrible room,” she says.

The nights with Gaiman blurred together. There was the time she passed out from pain while Gaiman was having anal sex with her. He made her perform oral sex while his penis had urine on it. He ordered her to suck him off while he watched screeners for the first season of The Sandman. In one instance, he thrust his penis into Pavlovich’s mouth with such force that she vomited on him. Then he told her to eat the vomit off his lap and lick it up from the couch.

A week or so into Pavlovich’s time with the family, their son began to address her as “slave” and ordered Pavlovich to call him “master.” Gaiman seemed to find it amusing. Sometimes he’d say to his child, in an affable tone, “Now, now, Scarlett’s not a slave. No, you mustn’t.” One day, Pavlovich came into the living room when Gaiman and the boy were on the couch watching the children’s show Odd Squad. She joined them, sitting down next to the child. Gaiman put his arm around them both, reached into Pavlovich’s shirt, and fondled her breasts. She says he didn’t make any effort to hide what he was doing from the boy. Another time, during the day, he requested oral sex in the middle of the kitchen while the boy was awake and somewhere in the house. “He would never shut a door,” she says.

On February 19, 2022, Gaiman and his son spent the night at a hotel in Auckland, which they sometimes did for fun. Gaiman asked Pavlovich if she could come by and watch the child for an hour so he could get a massage. It was a small room — one double bed, a television, and a bathroom. When he returned, Gaiman and the boy ate dinner, takeout from a nearby delicatessen. Afterward, Gaiman wanted to watch a movie, but the child wanted to play with the iPad. The boy sat against the wall by the picture window overlooking the city, facing the bed. Pavlovich perched on the edge of the mattress; Gaiman got onto the bed and pulled her so she was on her back. He lifted the covers up over them. She tried to signal to him with her eyes that he should stop. She mouthed, “What the fuck are you doing?” She didn’t want the child to overhear what she was saying. Gaiman ignored her. He rolled her onto her side, took off his pants, pulled off her skirt, and began to have sex with her from behind while continuing to speak with his son. “‘You should really get off the iPad,’” she recalls him saying. Pavlovich, in a state of shock, buried her head in the pillow. After about five minutes, Gaiman got up and walked to the bathroom, half-naked. He urinated on his hand and then returned to Pavlovich, frozen on the bed, and told her to “lick it off.” He went back to the bathroom, naked from the waist down. “Before you leave,” he told Pavlovich, “you have to finish your job.” She went to the bathroom, and he pushed her to her knees. The door was open. (Gaiman’s representatives say these allegations are “false, not to mention, deplorable.”)

February 26, 2022: In Gaiman’s bed after he left for Edinburgh. March 8, 2022: After telling Palmer about her experience with Gaiman. Photo: Courtesy of Scarlett Pavlovich.

Ten days after Gaiman left New Zealand, Pavlovich went to Palmer’s house for dinner. She asked Palmer if she could tell her something in confidence and made her promise not to tell Gaiman. She begged for reassurance that she would still keep her job as the child’s nanny. Palmer assured Pavlovich her employment was not in danger. Sitting in the kitchen, Pavlovich told Palmer that Gaiman had made a pass at her. She told Palmer about the bath. “I didn’t have any choice in the matter,” she said. “He just did it.” She said he had been having sex with her ever since. She withheld some of the most brutal details and did not describe her experience as sexual assault; she didn’t yet see it that way.

Palmer did not appear to be surprised. “Fourteen women have come to me about this,” she said. She mentioned that Gaiman had slept with another babysitter during his first marriage, and that she’d heard from other women who were disturbed by their experiences with him. Pavlovich waited until the end to tell Palmer about the child being present in Auckland. Afterward, she recalled, Palmer was silent. She appeared shocked. Palmer insisted that Pavlovich spend the night in her guest room. She told her, “I’ve had to do this before, and I can do this again. I will take care of you.” Pavlovich lay down in the bed and heard Palmer pacing back and forth in her room upstairs until 3 a.m.

Palmer called Gaiman that night. According to Horne, the musician, she asked Gaiman whether their son had been wearing headphones while he and Pavlovich were in the hotel room. He replied “no,” then hung up. The following day, Palmer emailed Gaiman and their couples counselor, a man named Wayne Muller, a minister and “a sort of marital companion,” as he put it to me. According to Muller, who relayed the contents of the email to me, Palmer wrote that Gaiman needed psychiatric treatment and had finally agreed to seek it. “Everyone was trying to make the best of what was clearly a difficult situation,” Muller tells me. Palmer then flew to Edinburgh, where Gaiman was staying with their son, whom she collected. Meanwhile, Pavlovich received a text from Gaiman: “Amanda tells me that you are having a rough time and you are really upset with me about what we did. I feel awful about this. Would you like to talk about it? Is there anything I can do to make anything better?” Pavlovich didn’t respond immediately. “My reflex was to fix the situation,” she tells me. The next day, she wrote, “Hey. We’ll speak soon … hope you are doing good.”

In the days and weeks after Pavlovich’s revelation, Palmer was solicitous, checking in frequently over text and sending warm notes: “From the minute you entwined your fate with mine on ponsonby road i’ve been glad i met you. That is tenfold so now.” She helped Pavlovich find a temporary apartment and invited her over for meals. In late March, Palmer sent a message to a friend of Pavlovich’s, a 41-year-old ceramicist named Misma Anaru, in whom Pavlovich had confided about Gaiman. “I’m glad she had you to take care of her,” she wrote. “It’s been a rough month for everyone.” Anaru’s partner, Kris Taylor, was a doctor of psychology who had lectured at the University of Auckland on coercion, consent, and rape. Although Pavlovich had never used the words rape or sexual assault to describe what had happened to her, both Anaru and Taylor believed Gaiman had raped her repeatedly. Anaru felt Palmer bore a share of the blame. Replying to Palmer, she wrote that “the majority of my rage is directed at Neil.” But she couldn’t understand why, with all Palmer knew about Gaiman, she had sent Scarlett into that situation. “Did you not see this coming a mile away?” She added, “And yes I know you asked him not to do that to her, but honestly, the fact you even felt that was something you should ask is fucked up in ways that defy comprehension.”

Around the same time, Pavlovich followed up with Gaiman. “I had a very intense dream about you last night,” she wrote. “Are you doing okay?” In his reply, he made a reference to something that had happened two weeks earlier. In a session with Muller, Palmer had said that Pavlovich was telling people he had raped her and was planning to “Me Too” him. “I wanted to kill myself,” he wrote. “But I’m getting through it a day at a time, and it’s been two weeks now and I’m still here. Fragile but not great.” He expressed dismay at Anaru’s message, which Palmer had told him about. “I’m a monster in it,” he wrote, “and Amanda seems to have bought it hook line and sinker.” Apologizing for “bringing any upset” into Pavlovich’s life, he wrote, “I thought that we were a good thing and a very consensual thing indeed.”

Pavlovich remembers her palms sweating, hot coils in her stomach. She was terrified of upsetting Gaiman. “I was disconnected from everybody else at that point in my life,” she tells me. She rushed to reassure him. “It was consensual (and wonderful)!” she wrote. Anaru had been “triggered by something I think,” she added.

“I am so glad that you messaged me,” Gaiman wrote. “I thought you were a monster.”

Gaiman asked Pavlovich to speak with Muller. “Knowing that you would be prepared to say, ‘It’s not true, it was consensual, he’s not a monster,’ makes me a lot more grounded,” he wrote. Muller reached out to Pavlovich to offer a “safe harbor.” When they spoke on the phone, Pavlovich told Muller what Gaiman, who was paying for the session, had asked her to say. After listening to Muller’s “esoteric, spiritual claptrap,” she felt worse. “I really felt it was all my fault.” Muller, for his part, tells me that ethical boundaries prevent him from sharing anything about his sessions with Gaiman, but he apparently felt comfortable sharing details of his conversation with Pavlovich. “What she called to speak with me about was feeling pressured — from very diverse, mostly older women in her community — to take action that she wasn’t sure she felt comfortable taking. I accompanied her on a journey to help her figure out the answers for herself to that issue.”

In the weeks that followed, Muller connected Gaiman with the Austen Riggs Center, a psychiatric facility in Massachusetts. According to Muller, Gaiman had several preliminary phone calls with the facility and was considering entering a six-week inpatient evaluation process. But Gaiman never followed through. “I don’t remember why not,” Muller says.

Pavlovich grew suicidal. She hoarded zopiclone and aspirin and walked around the city surveying bridges. She decided she’d take the pills and told Palmer about her plan. At Palmer’s urging, she checked into an emergency room. “You are loved,” Palmer texted. After a few days in a respite center, feeling slightly better, Pavlovich reached out to Palmer to ask if she could resume working as the child’s nanny. The apartment Palmer had set her up with was temporary, and she needed a place to stay. “It would be really good for me I think to have something to do and people to be around,” she wrote. Palmer argued that it was not the time for her to take on the responsibility of caring for a child. “Your job is to care for you,” she replied. She proposed they get together when Pavlovich got out, promising to help her get back on her feet, and suggested in the meantime she go home to her parents. This infuriated Pavlovich. “There is a reason I have divorced my parents,” she wrote. “I’m starting to feel very much on my own and like I hate everyone.”

“I can’t offer you exactly what you want from me,” Palmer wrote, “but i can still be here. remember this.”

“Babe I am more alone than I’ve ever been in my life,” Pavlovich replied. She wished she’d never agreed to be their nanny: “If I hadn’t gotten on that first ferry I wouldn’t be where I am now.”

That night, Pavlovich texted Gaiman. “Amanda keeps saying she will help but it seems more philosophical rather than actually like she will help.” Two minutes later, she added, “I’ve been thinking of you so much.” Gaiman replied that he’d be happy to help in a tangible way. Pavlovich then received an NDA dated to the first night of her employment, when he had suggested she take a bath. She signed it. A month later, she received a bank transfer from Gaiman: $1,700 for her babysitting work. Two months after that, she received the first of nine payments totaling about $9,200.

Over the course of the year, Pavlovich’s perspective changed. “As he faded away, I began to let other voices in,” she says. Friends connected her with women who were experienced in dealing with sexual assault and abuse, including Zelda Perkins, a former assistant of Harvey Weinstein’s and an advocate for ending the “misuse of NDAs to buy women’s silence.” (Wallner and Pavlovich broke their NDAs when they spoke out about Gaiman.) These women encouraged her to go to the police.

In January 2023, Pavlovich filed a police report accusing Gaiman of sexual assault. At the station, she gave a formal interview about the case. After she told the officers her story, one of them told her that Palmer’s cooperation would be essential for the case to move forward. Pavlovich assured them Palmer would participate. “I said to them, ‘She’s a public feminist, and she knows what happened. She’ll want to protect me. I’m sure she’ll speak.’”

May 16, 2022: From a video message to Pavlovich. January 20, 2023: A text to Pavlovich after she filed a police report. Photo: Courtesy of Scarlett Pavlovich.

This past fall, Pavlovich began studying for a degree in English literature at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. As it happens, the university had awarded Gaiman an honorary degree in 2016. In December, Pavlovich approached the head of the university, Dame Sally Mapstone, to share her experience and ask the university to review the decision to honor Gaiman. Mapstone was sympathetic but indecisive; some on the board, she told Pavlovich, would likely want evidence of prosecution to rescind his degree. As far as the police report goes, the “matter has been closed,” a spokesperson says. Gaiman’s career, meanwhile, has been marginally affected. A few pending adaptations of his novels and comics have been put on hold or canceled. But the second season of The Sandman is set to premiere on Netflix this year, as is Anansi Boys on Amazon Prime. (Amazon did not return a request for comment.) He and Palmer are entering the fifth year of an ugly divorce and custody battle. Gaiman has “bled her dry” in the divorce proceedings, according to someone close to her. She’s moved back in with her parents in Massachusetts. (Gaiman’s representatives alleged that Palmer was a “major force” driving this story in light of their contentious divorce.)

In December, Pavlovich flew to Atlanta to meet some of the other women who had made accusations against Gaiman. They had been unaware of one another’s existence until they’d heard the podcast. Since then, they had formed a WhatsApp group and grown close. “It’s been like meeting survivors of the same cult,” Stout tells me. “It’s impossible to understand unless you were there.” On New Year’s Eve, Pavlovich, Stout, and Wallner gathered around a bonfire at the Athens home of the musician Michael Stipe, an old friend of Wallner’s. Kendall joined them on FaceTime. With their dark hair and delicate features, they looked like they could be sisters. Around 11 p.m., they wrote down their intentions for the year and cast the scraps of paper into the fire. Pavlovich had written that she wanted to “release the yoke of victimhood” and “invite in self-acceptance.” The next morning, she woke before the others, made coffee, cleaned the kitchen, and sat on the porch in the winter sun. “Am I happy?” she wrote in her journal. “No.” But she also noted that she wasn’t alone. “There is no need to feel abandoned anymore.”

#neil gaimen allegations#neil gaiman#gaiman#palmer#radical feminism#radical feminist community#radical feminst#women's rights#human rights#radical feminist safe#womens liberation#feminism

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

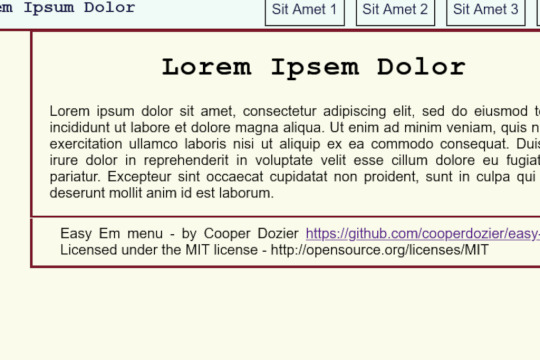

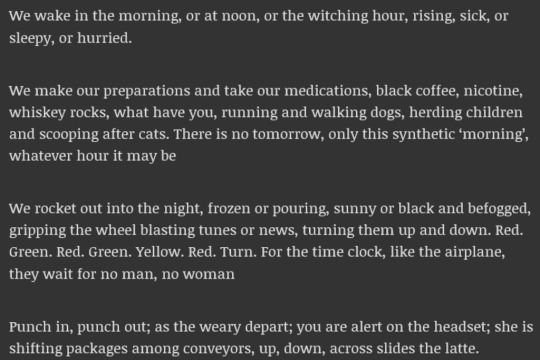

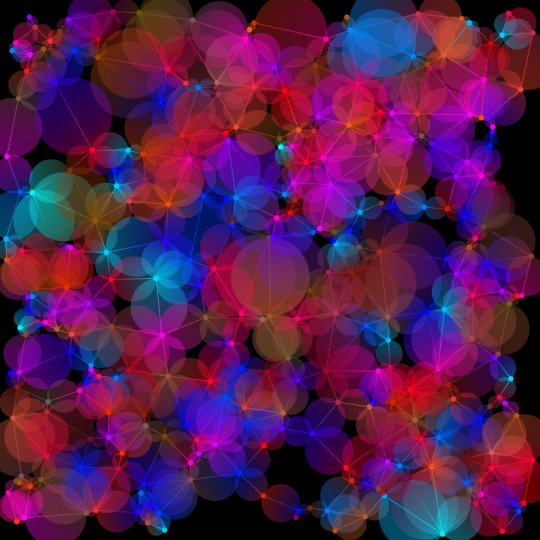

code art variation - gradient graphs

A gabriel graph is a special category of graph in graph theory where an edge can only be formed between two nodes if the circle formed by those two nodes contains no other nodes in the graph. A random geometric graph is a graph where an edge can only be formed between two nodes if they are less than a certain distance away from each other.

“Gradient Graphs” is an original generative code art algorithm; each run of the code produces a random visual output. The “Gradient Graphs” program generates random gabriel graphs and random geometric graphs, where each graph has a random number of nodes and each node has a random position and color. Nodes are connected by lines and circles that have a gradient from one point color to the other.

Users can interact with the program to remove the nodes, edge lines, or edge circles, choosing how they would like the graph to be displayed.

“Gradient Graphs” was made with JavaScript and p5.js.

This code and its output are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License.

Copyright (C) 2022-2024 brittni and the polar bear LLC. Some rights reserved.

#code art#algorithmic art#generative art#genart#creative coding#digital art#black art#artists on tumblr#graph theory#gradient graphs#made with javascript

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

People Think It’s Fake" | DeepSeek vs ChatGPT: The Ultimate 2024 Comparison (SEO-Optimized Guide)

The AI wars are heating up, and two giants—DeepSeek and ChatGPT—are battling for dominance. But why do so many users call DeepSeek "fake" while praising ChatGPT? Is it a myth, or is there truth to the claims? In this deep dive, we’ll uncover the facts, debunk myths, and reveal which AI truly reigns supreme. Plus, learn pro SEO tips to help this article outrank competitors on Google!

Chapters

00:00 Introduction - DeepSeek: China’s New AI Innovation

00:15 What is DeepSeek?

00:30 DeepSeek’s Impressive Statistics

00:50 Comparison: DeepSeek vs GPT-4

01:10 Technology Behind DeepSeek

01:30 Impact on AI, Finance, and Trading

01:50 DeepSeek’s Effect on Bitcoin & Trading

02:10 Future of AI with DeepSeek

02:25 Conclusion - The Future is Here!

Why Do People Call DeepSeek "Fake"? (The Truth Revealed)

The Language Barrier Myth

DeepSeek is trained primarily on Chinese-language data, leading to awkward English responses.

Example: A user asked, "Write a poem about New York," and DeepSeek referenced skyscrapers as "giant bamboo shoots."

SEO Keyword: "DeepSeek English accuracy."

Cultural Misunderstandings

DeepSeek’s humor, idioms, and examples cater to Chinese audiences. Global users find this confusing.

ChatGPT, trained on Western data, feels more "relatable" to English speakers.

Lack of Transparency

Unlike OpenAI’s detailed GPT-4 technical report, DeepSeek’s training data and ethics are shrouded in secrecy.

LSI Keyword: "DeepSeek data sources."

Viral "Fail" Videos

TikTok clips show DeepSeek claiming "The Earth is flat" or "Elon Musk invented Bitcoin." Most are outdated or edited—ChatGPT made similar errors in 2022!

DeepSeek vs ChatGPT: The Ultimate 2024 Comparison

1. Language & Creativity

ChatGPT: Wins for English content (blogs, scripts, code).

Strengths: Natural flow, humor, and cultural nuance.

Weakness: Overly cautious (e.g., refuses to write "controversial" topics).

DeepSeek: Best for Chinese markets (e.g., Baidu SEO, WeChat posts).

Strengths: Slang, idioms, and local trends.

Weakness: Struggles with Western metaphors.

SEO Tip: Use keywords like "Best AI for Chinese content" or "DeepSeek Baidu SEO."

2. Technical Abilities

Coding:

ChatGPT: Solves Python/JavaScript errors, writes clean code.

DeepSeek: Better at Alibaba Cloud APIs and Chinese frameworks.

Data Analysis:

Both handle spreadsheets, but DeepSeek integrates with Tencent Docs.

3. Pricing & Accessibility

FeatureDeepSeekChatGPTFree TierUnlimited basic queriesGPT-3.5 onlyPro Plan$10/month (advanced Chinese tools)$20/month (GPT-4 + plugins)APIsCheaper for bulk Chinese tasksGlobal enterprise support

SEO Keyword: "DeepSeek pricing 2024."

Debunking the "Fake AI" Myth: 3 Case Studies

Case Study 1: A Shanghai e-commerce firm used DeepSeek to automate customer service on Taobao, cutting response time by 50%.

Case Study 2: A U.S. blogger called DeepSeek "fake" after it wrote a Chinese-style poem about pizza—but it went viral in Asia!

Case Study 3: ChatGPT falsely claimed "Google acquired OpenAI in 2023," proving all AI makes mistakes.

How to Choose: DeepSeek or ChatGPT?

Pick ChatGPT if:

You need English content, coding help, or global trends.

You value brand recognition and transparency.

Pick DeepSeek if:

You target Chinese audiences or need cost-effective APIs.

You work with platforms like WeChat, Douyin, or Alibaba.

LSI Keyword: "DeepSeek for Chinese marketing."

SEO-Optimized FAQs (Voice Search Ready!)

"Is DeepSeek a scam?" No! It’s a legitimate AI optimized for Chinese-language tasks.

"Can DeepSeek replace ChatGPT?" For Chinese users, yes. For global content, stick with ChatGPT.

"Why does DeepSeek give weird answers?" Cultural gaps and training focus. Use it for specific niches, not general queries.

"Is DeepSeek safe to use?" Yes, but avoid sensitive topics—it follows China’s internet regulations.

Pro Tips to Boost Your Google Ranking

Sprinkle Keywords Naturally: Use "DeepSeek vs ChatGPT" 4–6 times.

Internal Linking: Link to related posts (e.g., "How to Use ChatGPT for SEO").

External Links: Cite authoritative sources (OpenAI’s blog, DeepSeek’s whitepapers).

Mobile Optimization: 60% of users read via phone—use short paragraphs.

Engagement Hooks: Ask readers to comment (e.g., "Which AI do you trust?").