#just the collectivism of it all. kills the man

Text

makes me insane

#remember whn we first got this picture??#i go insane every time i think about it#just the collectivism of it all. kills the man#mcr#mcrmexico#mcr corona

729 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oh yeah the king family thing, it’s not like there was this big assassination of a very important person in Dallas who had the nickname Jack and it shook the world…who might have ended the Cold War sooner.

And his supposed killer was murdered before he was even questioned

And another character who filled his position wasn’t killed as well…

Okay allegedly it was the cia, but the FBI really think that the King family would buy their claim after wire tapping MLK own fucking home and sent that letter saying he should kill himself?

Oh and the Malcom x thing, I mean when you are a powerful figure that left an extremists group saying that white people was made in a lab by a bitter black guy. Not shocking who killed you

(Got a feeling the government payed NOI to do that hit?)

And Anna Frank thing, I presume her diary came out in the 50’s. Given that people had a panic about Pixar Turning Red the Asian female mc had LE GASP hormones(not to mention she tame af compare to the….less that ideal stuff I see women in fandom make) lords knows how many fathers and mothers would have heart attacks learn that their “innocent” daughters might be doing private if they read Anne Frank unedited diary

Fuck I sound like I’m on Epstein list

Oh yeah I heard about that academic paper, I mean leftist basically made the black version of birth of a nation with women king. And the majority of radfems goes uncheck and they have positions of power in institutions.

We only learn about the horrors the Nazis did, not the fact they had a “eat the rich” as the left don’t want to admit a lot of Jewish people that Hitler targeted was well off

Oh yeah the king family thing, it’s not like there was this big assassination of a very important person in Dallas who had the nickname Jack and it shook the world…who might have ended the Cold War sooner.

And his supposed killer was murdered before he was even questioned

For some reason I read this like 3 times and each time even though I knew it's JFK you're talking about my brain added a "Ruby" to Jack, which I suppose works since jack ruby is the guy that killed lee harvey oswald.

The X-Files did a episode where they went into a lot of different stuff that CSM did, if you know the show at all.

"Musings of a cigarette smoking man" It's a really good one, actually works as standalone that you don't need to know anything about the show to enjoy.

Mallcolm X stuff is nuts, I don't think the feds bothered with him though, it's farrakhan all the way there. If there was a firm move towards improved race relations he might just lose his cash cow, it's not just politicians that profit from the status quo, look at any social movement out there who's original stated goal was achieved.

Title IX and the Civil Rights Act should have been the stop and then nothing else legislative needed, but nope that didn't happen.

1948 for the Diary, there was just a lot of sexual stuff, bisexual to be more specific I believe, talk of her period, things you would imagine a girl that age would be talking about really, like you said, but not in 1948 you don't get that published around the globe then.

I'm good with keeping the sanitized version the one used in schools too, at least till college maybe I don't know.

We only learn about the horrors the Nazis did, not the fact they had a “eat the rich” as the left don’t want to admit a lot of Jewish people that Hitler targeted was well off

You also aren't going to learn that there was quite a bit of socialism mixed into the nazi deal, collectivization, hitler youth indoctrination centers where you learn that your duty is to your fatherland and your fuhrer,

My dad sings in the chorus for the local symphony, guy in it was hitler youth, said it was like a summer camp, but he was part of a group that did tours and sung patriotic songs so he lucked out, also lucked out that his mom kept him home from that last trip.

But ya there's a lot of that they can't bring up today, because it looks too much like socialism (because it is) weren't before because socialism bad nazi bad was good enough, for the most part.

Should have done better on that sadly

______________

Sorry this took so long I was facetiming a friend I never really get to do much more than text with.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you believe the Paris Commune could have succeeded in fully capturing power in France if it had pursued a different policy towards the Versailles? A friend of mine wrote a biography on Blanqui and he has argued to me that if Blanqui had evaded capture by the police before the rise of the commune, he could have plausibly led it to victory. Because to him the key reasons for the communes failure was its headlessness. It spent the initial weeks after taking power not sure of what to do, and that gave the Thiers time to reorganize its forces for an assault on Paris. He argues that Blanqui had the authority that he could have led the national guard to pursue the government while it was still shattered and give it the killing blow.

He's a big Jacobins fanboy though so I think he might just be a bit too persuaded by the whole "Jacobin regime 2: what did you say about me being Robespierre repeated as farce" of it all.

I'm less sure that Blanqui necessarily would have been the man of the hour, the dude had a lot of downsides as well as his upsides. (I'm more of a Louis Blanc man myself.)

But in general, I'm a bit less sanguine about the chances of the Paris Commune: at most, if they had successfully destroyed the government at Versailles, I think that would have just bought them a bit of time until a new government reformed somewhere else in France that would call in a much larger and better armed French Army to crush them.

The basic problem that the Paris Commune faced was that the French left's support was really concentrated in Paris and that, out in the rest of France, moderate republicanism was kind of the best you could hope for, and they were locked in a life-or-death struggle with the Orleanists, the Bourbonists, and the Bonapartists which would dominate much of the Third Republic.

The Left's fatal weakness in the French provinces wouldn't really be solved until after the crushing of the Paris Commune. Ironically, it was the revolutionary Marxist French Workers Party (POF) that led the charge, in part because they viewed organizational strength for the forthcoming revolution as more important than the immediate demands of bourgeois electoral politics. By the late 1880s, the POF had managed to get a foothold going in the Nord, Pas-de-Calais, Loire and Allier provinces, but things wouldn't really change until...

...the internal political implosion of their electorally-minded reformist rivals (the Possibilist Federation of the Socialist Workers of France). With a whole bunch of socialist organizers and voters out there with no home, the POF launched a major recruitment drive in 1890 and 1891 centered around May Day and the eight hour day, sending speakers and organizers out to provincial centers to agitate, propagandize, and above all, recruit. From an incredibly small base of only 2,000 members in 1889, the POF suddenly had 10,000 by 1893 - and equally importantly, it had a modern, organized party structure fully stolen from the German SPD.

This party organization in turn began to organize the provinces and develop a rural program that focused on nationalization of the railroads and the canals (which the farmers really liked, because they hated the railroads and canals as much as American populists did) and de-emphasized the immediate collectivization of land (which scared the hell out of the farmers). These campaigns bore results: in 1889, the POF had won only 167,000 votes (2%) and 13 seats in the Chamber of Deputies; by 1893, they were up to 400,000 votes (5.4%) and 41 seats; by 1898, they were up to 786,000 votes (9.7%) and 55 seats.

(Then again, there's a whole argument that the "modernization" of the French countryside in the 1880s/1890s rendered the rural voter more likely to support socialist parties, but that's sort of a chicken-and-egg thing.)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Different Types of Indifferent Violence

Wondering what violence is may seem superfluous, especially when viewers can see all definitions in practice they’d like by choosing any random streaming service episode. Everyone may be aware the term involves action that leads to something broken ranging from bones to furniture. But noting just who and what is involved may offer a bit of context to everyone sick of bloodshed. That’s almost everyone.

As always, liberalism is precisely inverted. Flipping over life is not just limited to thinking government stimulates the economy: there’s a body count, as well. The view that combat must be de-escalated disregards demons who keep taking it up.

The only way woke proselytizers could get more objectionable is by getting what they want. Very tolerant adherents desire to give much of Israel to its lunatic attackers. Meanwhile, they’re horrified by replying to said attacks on life itself. If there’s a purer example of screwed-up thinking, they haven’t found it yet despite dedicated efforts.

Deranged leftists are furious at the measured response to getting in the way of Hamas rockets. The terror squad didn’t kill more people only because they don’t possess the technology to fire missiles. Anti-Semites think Israel must have denied it to them.

Targeting fiends who hide in hospitals might get messy. It’s not that tricky to determine who’s responsible for those capable of reasoning and decency, which leaves out the left. A nation attacked for the crime of minding its own business does everything they can to minimize casualties from those who try to maximize them. Oh, and the latter slaughter innocents while the Middle East’s sole republic takes aim at perpetrators. It can’t get clearer.

The most enlightened reiterate war is bad as they do all they can to keep it existing. Armed battling is the poverty of international affairs. Everyone feels bad about collateral damage while the levelheaded know it can never be eliminated. Decreeing that it’s entirely possible to avoid innocent casualties is as oblivious as believing stores will stay open after shoplifting is legalized.

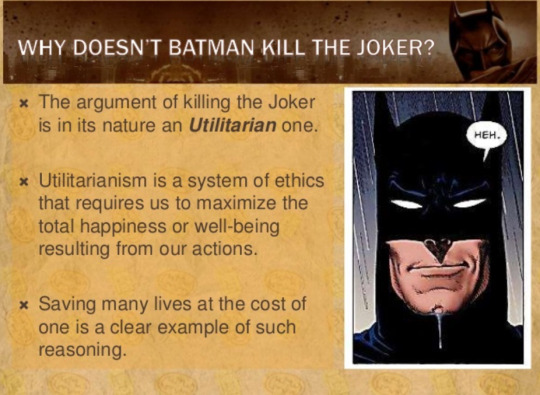

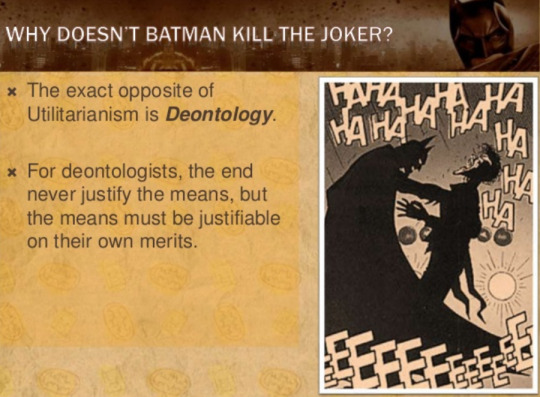

Everything’s backward in the minds of those who led us there. Classifying words as action epitomizes that charming totally incorrect manner of theirs. Israel’s American enemies are particularly offended by noting obvious truths, as they run counter to their preciously-guarded narrative. If Democrats truly oppose violence, they should keep cities from descending into live recreations of Batman movies before the titular character arrives.

Getting upset over nothing can get worse in what’s almost a feat. Social justice warriors don’t wage war against actual injustice. Sensible modern thinkers act like misgendering is an assault as they shrug away the Hamas branch of Planned Parenthood committing very late-term procedures. Changing from a man into a woman is as real Gaza Strip residents who support peaceful coexistence.

Purveyors of laxity should ponder what would happen in Gaza to a man who decides he’s not one. In America, we just stop drinking your appalling beer. Language is violence while violence isn’t in these advanced times. You may have noticed the outlook is exactly screwed up. Unhinged zealotry may not be a sign of acceptance.

Principles can be applied at any level, unfortunately. Academic dolts who perceive Hamas as freedom fighters also by pure coincidence treat criminality as the inevitable reaction to poverty. Never mind that collectivism’s enthusiasts cause the very brokenness they condemn. Struggling Americans who can’t afford crazy extravagances like items have compassionate confiscators to thank.

An unwillingness to differentiate between types of violence serves as a lame attempt to conceal moral cravenness. Practitioners are cagey about if they really think they’re above it all or root for the villain. A robber who shoots a victim and the cop who shoots back are engaging in precisely different types of violence that backers of defunding cops refuse to discern. In fact, the person enforcing laws is treated as a racist oppressor by those who want the state to have absolute authority.

Violence is indifferent. Indifferently denouncing violence shows a lack of sophistication from alleged experts. Active force is much like guns, which can be used to either inflict evil or interdict against it. Take, say, a parliamentary republic dropping brutality upon fiends who did so to them first. Israel’s disparagers hate devices as much as they do the notion that there’s one Jewish nation on Earth.

We live in Tom Wolfe’s world. it turns out his fiction was predictive. His nonfictional subjects exhibit such a perfectly twisted take on logic that they couldn’t mock themselves even if they were capable of introspection.

Self-righteousness aimed at the country defending from marauders makes the sides clear for anyone confused. Malicious clatter from campuses and maniacal rallies only sounds like a parody. Alleged backers of underdogs rabidly cheer against Israel. They pre-empt those who mock them.

Ghastly allies of terror drives couldn’t define themselves better. They’re not even trying. You’ve undoubtedly grown tired of attempting to determine whether the inability to distinguish between types of aggression constitutes blatant ignorance or ghastly devotion to diabolical causes. Inadvertently revealing they side with villains is the closest they’ll get to honesty.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

The Holodomor happened and Stalin could've avoided or stopped it at any time

Oooo, something I know a lot about!

Well, there is a half truth here, which is that, yes, yet another famine did indeed occur in Ukraine in the 1930s along with the greater Soviet region, as famines occured there repeatedly for many centuries, and this famine did indeed kill people.

This cycle of famine killed millions for hundreds of years under various tsars. And yet, less than a few decades after the Soviets took power, the cycle of famine was finally broken, and starvation in the region became a distant memory. The famine you call the "Holodomor" was one of the very last of these famines that the Communists worked diligently to prevent and alleviate--even during times of war and barbaric invasion and strangling siege from the world powers--and who the first finally successful in doing so.

So, how did this story get twisted from "the Soviets finally ended a brutal cycle of famine that the tsars did nothing about," to, "Joseph Stalin created a man-made famine to purposefully kill Ukranians in a campaign of genocide and terror"?

Let's talk about kulaks, international rightwing news, and then finish off with miscellaneous factors that exacerbated the famine and slowed Soviet response to it.

When the impoverished and starving masses of the Russian Empire and its colonies, led by the Bolsheviks, arose in a popular revolution a decade prior to seize society for themselves to build the socialist Union, there were many who fought quite viciously to stop this People's Government from coming to or keeping power. The remnants of the tsarist government, big corporations, fascists, white supremacists, the Orthodox Church hegemony, and opportunists all took money, weapons, training, soldiers, resources and other support from European and American monarchies/rulers and international corporations who had colonial interests in tsarist Russia and its own colonies; those who had a vested interest in keeping the Soviet people oppressed and suffering, from Russia to Ukraine to Kazakhstan, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Siberia, Georgia, Lithuania, and others. These counter-revolutionaries, this coalition of fascists and capitalists supported by or directly from the Western imperial powers, these people murdered civilians, minorities, and elected government officials in terror attacks, bombings, shootings, pogroms. They destroyed trains, granaries, farming equipment, factory equipment, tools, spare parts, buildings, homes, power grids, water pumps--this was a war directly on the masses, on the populace. This war on the life of the Soviet people themselves was most fierce in the civil war against the Whites (the tsarist remnants), and particularly in the genocidal Nazi invasion, but it continued for the entirety of the USSR's existence--and slowed but didn't stop even when the Union dissolved and the ex-Soviet states became capitalists or fascists themselves, up to this very day, manifest in NATO plans to balkanize and neoliberally colonize modern capitalist Russia.

One of the most despicable cases of this sabotage against the new, aspiring egalitarian society was the kulaks and what they did during these times of famine.

The Soviets had collectivized the land and the food, and began distributing it evenly to the peasants who had toiled in serfdom these lands for generations without reward; in essence, confiscating lands from wealthy slaveowners and giving the farmlands to the slaves, and ensuring those who were most vulnerable to starvation (such as during hard winter months, or famines) always had access to the bare necessities to live.

So, what did the kulaks do in response to this confiscation and just redistribution?

They burned their own crops. They killed their own cattle and horses and chickens and pigs by the herd. All to spite the new government of the people--and all leading up to and in the middle of this famine you reference as the "Holodomor."

So, we have a region that has historically suffered from famine repeatedly for centuries, and right when they are due for another one, a class of people that amount to slaveowners and landlords and those that aspire to be like them starts sabotaging a socialist government by destroying food en masse.

Sure enough, famine hit, and large amounts of people died.

See, and this is where rightwing news sources come into play.

As referenced, there were many monarchist, capitalist, and fascist interests involved in destroying the socialist experiment from its birth until long after its death.

One microcosm of this genocidal hatred was the fake news. Anybody with even a moderate grasp on history and the realities of the modern day knows that any leftwing governments, movements, or individuals are subject to lies and deceit of their rightwing adversaries. 1930s Eastern Europe was no different. Sourced that were dismissed unanimously at the time even by liberals and conservatives alike as rightwing tabloids--the Breitbarts and Stormfronts and Fox Newses and 4chans and OANs of the day--all began inventing stories of thousands, no, hundreds of thousands, no, MILLIONS, NO, TENS OF MILLIONS of dead littering the dirt roads of Ukraine--a claim quickly debunked by several verified reports at the time from independent journalists, diplomats, and travelers of various nationalities and political predilections at the time.

And yet, what amounted to flat earth conspiracy in the 1930s got a veneer of trustworthiness as its newspaper pages yellowed charmingly with age, and after urgings by the CIA, began to be used as legitimate sources cited in scholarly articles in Ivy League campuses. The Banderites, a sect of Ukranian Nazi collaborators in WW2 who joined the German Nazis in raping, pillaging, and murdering their own countrymen, also spent their every waking moment pushing for decades pushing these otherwise contemptible narratives riddled with errors and blatant fabrication, forgery, and theft--pictures used from completely different famines in completely different countries, tallies of dead that do not match birthrates and subsequent censuses by the tune of millions of people, completely invented and unverifiable names of imaginary interviewees, even the supposed TRAIN SCHEDULES of these supposed "journalists" have been debunked to the point of proving none of them even set foot in Ukraine SSR or anywhere else nearby.

Suddenly, what was correctly seen by all normal people as total BS in the 1930s, after a century of legwork, suddenly was trustworthy primary sources that were cited by Harvard professors, and then American diplomats, and then Wikipedia, and now everybody on the Internet who recounts the tale of Stalin's genocide on the Ukranian people--an idea alone that is complete nonsese when one considers the vast resources that leaders such as Stalin invested into ENDING these famines, developing Ukraine, and feeding ALL the people within the Soviet Union, all at the EXPENSE of the Russian body.

The repeated behaviors of the Soviets show them to be concerned with helping the masses achieve the basic necessities of living, they show a longstanding love and comraderie between Ukraine and Russia, they show intense efforts to end natural disasters such as famine. The repeated behaviors of the USSR's enemies show a bunch of cowards who will stop at nothing, lying and destroying to sabotage anything even remotely leftwing that threatens their colonial interests, such as a large unified Eurasian world power that refuses to allow multinational corporations to have a blank check robbing their people for cheap labor or resources.

To let off the gas pedal and reach a stopping point, I must pay homage to some other factors.

The experiments of Soviet scientist Lysenko, one of those tasked with ending such famines and industrializing agriculture to a scale that could quickly feed the entire Soviet people, were a failure, and likely contributed to the predestined famine that struck 1930s Ukraine. While many valuable lessons were gleaned from the failure of Lysenkoism, it is no doubt that its failure may have exacerbated the famine.

There is also the question of the struggling, newly born Soviet state to modernize in its early days. There was some telegrams, but most communication still had to be done by horseback mail carriers, and telephones were barely a thing at all yet. News traveled slow through the mountains, steppes, tundras and forests.

Finally, there is a legitimate question as to mid-level Soviet officials being negatively motivated to exaggerate or outright lie to meet their quotas. While early Soviet history is filled with comraderie, cooperation, bravery, justice, determination, and communal compassion, it is also simultaneously, due to the extreme pressure from international invasion, civil war, sabotage, and the like, an era of violence, mistrust, paranoia, disloyalty, volatility, and a lack of confidence. Many of this Soviet officials feared failing their country, they feared losing their positions, many even feared overzealous higher-ups would deem their failures to be intentional, proclaim them a traitor, and imprison or kill them--it was difficult to tell during this time who was collaborating with or sympathetic to the enemy, who was being paid by foreign agents, who was an opportunist enriching themselves, and in this confusion and militant attempt to keep the ship from sinking, there are tales of innocents whose lives were ruined or even stolen from them. Many mid-level Soviet officials assigned to keep track of the region misrepresented and padded their numbers to make it appear things were well on-par with Soviet objectives. Thus, grain was exported even when the famine was full swing, because the reality of the famine--especially when combined with the slow-travelling news--had yet to truly sink in to the Soviet leadership.

In closing, the following:

Mistakes were certainly made, and many people died--the true number is hard to determine. However, what is sure is that modern Western estimates are grossly distorted. The famine of Ukraine in the early 1930s was one of the last of its ilk due to the diligent work of the Communist government to destroy the cycle of famine, and they eventually succeeded, and not only Ukraine but the entire multinational, multiethnic Soviet Union and its hundreds of millions of people never suffered starving or food insecurity for the rest of the Union's existence.

#ukraine#ukraine war#holodomor#famine#genocide#stalin#back in the ussr#ussr history#countryhumans ussr#ussr#russian invasion of ukraine#nato#fake news#world history#soviet#soviet union#communism#socialism#tankies#marxism leninism

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflection: On the Social Contract

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in On the Social Contract, writes on the nature of freedom, oppression, humanity, and government, outlining the “social compact” as a means to measure and attain what he values most in polity—independence. Rousseau critiques his contemporaries, particularly Hugo Grotius, for sophist justifications of slavery, criticizing their understanding of power and politics, and contending that the ultimate sovereign authority for any state lies in the collectivized will of its people.

Rousseau begins his work with a brief, poetic description of the human condition regarding independence—“Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains”—an eloquent phrase outlining the nature of social existence: only in one’s infancy is the individual unshackled from their social obligations (141). At face value, law and order would seem to be the enemy of autonomous agency in light of this observation. This extends beyond the level of the individual. Society is as shackled in its growing into maturity as the persons who constitute it, according to the philosopher. This imprisonment is avertable, though, and the author resolves to construct a mechanism by which a state may orient itself according to the united will of its people, referred to as the “social compact.” To more fully understand this, an examination of Rousseau’s ethic of force is requisite.

Interstitial to On the Social Contract is a striking critique of unexamined Machiavellian notions of force and power. Rousseau targets the work of Hugo Grotius, in particular, as an example of the philosophical inadequacies of such a base understanding of social order. The first four chapters of Book I (Subject of the First Book, Of the First Societies, On the Right of the Strongest, and On Slavery) are dedicated to dismantling such naturalist positions that justify the “right to rule” on the basis of force alone. He writes, “Grotius denies that all human power is established for the benefit of the governed, citing slavery as an example. His usual method of reasoning is always to present fact as a proof of right. A more logical method could be used, but not one more favorable to tyrants” (142). This reveals a few of Rousseau’s primary complaints: that his contemporaries 1) confuse status quo for status potissimus, making out the current state of affairs to be equivalent to a perfect (or at least reasonable state), and 2) do so in favor of their own self-interest, as a political action that substitutes a conscientious desire for good with a cowardly craving for security, acting much like the tyrants who they tacitly support. Rousseau asserts his aversion to this framework, noting that inequality does not stem from innate qualities of persons, but rather that “force has produced the first slaves.” [1]

Grotius’s position seems to follow a misguided line of reasoning about just acts in war, which Grotius uses to construct an understanding of compliance and obligation that makes the two synonymous. He concludes that, in war, one man has a right to kill another, and exercises that right through force. Grotius then notes that a more “legitimate” act, in such conditions, is the enslavement of the overpowered adversary, because it allows for more “profit” to both parties. [2] Further, he derives from this so-called legitimate act in war a privatized right of those in power to dictate the actions of those who fall prey to them, and considers the impulse to obey such commands to be the slave’s moral duty. Rousseau finds this argument to be ill-devised, in large part because war is divorced from the individual’s moral capacity—it stems from the state; a state cannot enslave a people since it is, by nature, composed of those people. Rather, should a people be oppressed under a state’s authority, that state is ruled by private opinion, by the minority, and is no longer a legitimate extension of such oppressed peoples’ moral power. Rousseau asserts that this state is not sovereign, or even a nation in any real sense: regarding this, he argues, “I see nothing but a master and slaves; I do not see a people and its leader. It is, if you will, an aggregation, but not an association. There is neither a public good nor a body politic there” (147). Persons under this condition have been robbed of their right to autonomy and cannot, as such, possess a duty to their masters. Still, Grotius’s standpoint contends that slaves have donated their right to life and must adhere to the mandates of their oppressors independently (i.e. as moral agents), as a pseudo-indemnification to repay their captors for their continued vital state.

Grotius’s rationale is ironic, since it posits a “donation” of rights that nevertheless indebts the donor to their charitable recipient. Moreover, in a state of war, the principle right at stake for the citizen is their life, and autonomy by extension, yet Grotius does not consider the ethical liability relinquished alongside its source. Again, he confuses the prima facie state of things (that a slave apparently has a duty to obey a master) with the correct state of things (that a slave is obligated, through force).

This, of course, is a shallow argument, and fails to consider the relative moral weight of obedience compared to duty. The former, Rousseau contends, is morally empty; in On Slavery, he writes, “Removing all liberty from [a person]’s will is tantamount to removing all morality from his actions” (145). One cannot consider themselves to be a complete moral agent if they’ve surrendered their agency. Since liberty is necessary for any person to consider their thoughts, actions, and duties to be rational, sound, and binding, such a person, in Rousseau’s eyes, has surrendered not only their agency, but their own moral burden as well.

Rousseau’s introductory statement is further developed in this—one shackled under the yoke of society is free from some moral burden beneath it, as their ethical instrumentality is limited. To exemplify this, one may consider that a person who does not belong to a collective justice system may have a proper burden to seek retribution should another commit a crime against them. However in a body politic, this otherwise just act is criminalized as vigilantism and substituted with a systemic means of seeking restitution limited by a right to due process, afforded by some sovereign body. We will discuss this example at greater length later, as it gives additional insight into the nature of Rousseau’s argument. For now, it serves to illustrate that the subject in question emancipates themselves from their burden of retribution by their collaboration with their body politic.

Grotius has a response to this—he notes that a people can choose subjugation in giving themselves over to a particular sovereign. From this, Rousseau dissolves his opponent’s claims as, he points out, in order for a people to choose to collectively become subjects, they must be a collective in the first place. This is implicit in Grotius’s claim, and Rousseau finds common ground here to establish a “true foundation of society” (147). From this, Rousseau begins a positive construction of his social compact wherein the state of nature’s limitations on humanity’s maintained existence are overcome through an “alter[ed] mode of existence” (147). Of course, this mode of existence ought to preserve the goods inherent to the state of nature, in particular, freedom. To accomplish this, Rousseau composes the following basis for a proper, reasonable society: treating each person’s will as a variable which is optimized summarily with their peers, a society exists when this sum maximizes, positing a basis for sovereignty contingent on a sort-of “Pareto Optimality” of freedom. The philosopher refers to this maximal state as the “general will." Put in simpler terms, “true” society arises when each person acts in their greatest free capacity, insofar as that capacity does not, on the whole, inhibit the will of another, and limits on peoples’ will are agreeable if each person’s most possible free state is actualized by those limitations. [3]

Returning to the previous example, the person who forgoes their right to retribution in exchange for a right to due process has not given up much freedom on the whole but ensures that, by their sacrifice (and the sacrifice of each member of their state), the whole of society affords greater freedom by means of a fair justice system, where revenge and retribution are not as readily confused. Further, by unshackling that person from the duty to enact retribution, moral culpability for the action is the whole of that society's, motivating it and empowering it to construct systems that should be more capable of fulfilling those moral obligations bestowed upon it by the surrendered agency of its constituents.

Rousseau does not consider the general will to be a guiding moral principle. It is, at most, a means to test the validity of governance. This is clear in Book II, Chapter VIII, entitled On the People, where Rousseau considers that a people may freely choose vice, even collectively, and still act according to the general will, citing King Minos in Crete as a good lawmaker who “disciplined nothing but a vice-ridden people.” Of course, Rousseau considers this to be the exception, rather than the rule. Rousseau regresses in his argument when evaluating this case, proclaiming that a nation where the general will covets evil and has already undergone violent reform, needs a “master,” since “liberty can be acquired, but it can never be recovered” (166).

This notion is applied by Rousseau axiomatically, and (unsurprisingly) stirs up controversy. For one, astute readers will point to many nations which have undergone successive revolutions, such as France, China, Germany, etc.. This is an understandable misconstruction. The nations, at each of those revolutionary junctures, take on the same name as their predecessor, giving the illusion of continuity. Should the peoples’ general will allow it, they may even take on some of the same laws and customs. Yet each nation is born anew through these changes, and one cannot reasonably assert that the nations in question are constituted in the same way—the body of law discharged at these moments of change is altered too significantly to consider the nation to be the same, and indeed the context of the nation changes just as much with the passage of time. Were nations men and time a flowing river, Heraclitus’s famous words would come to mind, that, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same man.” At every point, the changing of a nation’s general will necessitates a new understanding of what that nation is.

The former notion of Rousseau’s is the more suspect of the two, though—that a state which revolts unsuccessfully against a corruption of morality or authority requires a master, rather than a liberator. His analysis of Peter the Great will assist us here. He notes that, in response to the Russian citizenry’s “barbarousness,” the monarch attempted to civilize his people prematurely (166). The philosopher’s assertion here is not that Peter was wrong in attempting to follow the general will of his people, but that in his imitations of Europe, he failed to allow his peoples to form a collective will of their own. As such, Rousseau seems to believe it would have been better for the Russians to have remained "un-westernized" until they’d established their cultural identity by forming a social order without the prompting of the monarch. This allows for a more true expression of the general will, in Rousseau’s eyes. In lieu of political turmoil, Rousseau seems to share this sentiment—that it is better for an infantile nation to constitute itself, and that a “master” acts as some necessary evil, a holdover until such a nation reaches the vigor of its youth.

Rousseau's critique of Grotius and his contemporaries can be seen as a call to reject the naturalistic justifications for oppression and to instead embrace a more collectivist understanding of the social contract. By emphasizing the importance of the social compact and the need for a legitimate and moral authority to oversee it, Rousseau seeks to provide a framework for creating a society that is both free and just. While his ideas may not have been fully realized in his own time, they remain relevant today as philosophers continue to grapple with questions of freedom, power, and oppression in contemporary societies.

Notes:

[1] Notably, Rousseau is not altogether modern in his stance here. In the same breath he asserts that “[Slaves’] cowardice has perpetuated [slavery].” Obviously, this is not aligned with the true nature of slavery, but it is consistent with much of Rousseau’s argumentation. For instance, in his discussion of a prince’s apparent wrongly-extended right to avoid usurpation on the pretense of peace, Rousseau notes that the apparent compliance of that sovereign’s people who he deceives and silences appears indicative of the favor of the general will, contrary to the matter-of-fact. Rousseau places the responsibility to circumvent this pattern in the hands of the people, though, in gathering and collaborating in their collectivized aspirations. This is much like his assertion about slavery—he regards the prince and the slaver as immoral actors, but does not see such judgements as actionable outright—the recipients of these injustices must, in Rousseau’s eyes, respond with clarity and purpose.

[2] This profit extends, in Grotius’s point of view, beyond material gain. His position contends that there is further value in subjugation insofar as it brings about a state of security; a slave’s master offers protection. This rationale is common to tyrants and warring states, and Rousseau argues that a polity that truly craves peace over autonomy is mad, and thereby not reasonable enough to be considered a people in the first place, since “Madness does not bring about right.” (144) One can find placid environments in all manner of undesirable places, such as dungeons and caves, but Rousseau seems to find that Grotius and his contemporaries would hardly vouch for those conditions on account of this one merit—so enforced order clearly cannot be the keystone metric for societal flourishing, given this exception. However, Rousseau is not consistent in this analysis, as he notes that a silent peoples’ consent to private will can be equated with the general will (154) despite these peoples not expressing a general will or even acting according to his own definition of a political “body.” (150). Further, his position here runs counter to the argument discussed in [1] regarding the devious prince.

[3] Note, this is distinct from each person’s desired willful state—Rousseau does not believe that each person, left to their own devices, will act according to the general will, as humans are wont to neglect the freest possible state of a collective in favor of the freest possible state of the self. It is best not to conceive of the general will as the abstracted private will of any one citizen or group of citizens, but rather as a social order constructed to optimize the autonomous capacity of its people, by treating them, at times, as subjects. However, this does not mean a state of anarchy is impossible according to the social contract, as is evidenced in the final paragraph of the third book where he writes “For if all the citizens were to assemble in order to break this compact by common agreement, no one could doubt it was legitimately broken” (203).

Bibliography:

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “On the Social Contract,” in Basic Political Writings, Edited and translated by Donald A. Cress, 141-204. Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987.

#philosophy#art#ethics#aesthetics#aesthetic#ethical#critique#beauty#sublime#religion#continental#revolution#politics#social contract#rousseau#slavery#grotius#an analysis of some philosophical shade#Not my proudest piece tbh#readability is LOW#Apologies#Discussion is welcome and encouraged#Love a good philosophical convo so let's get this thing crackin#Eh

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

S4. Ep14. Goodbye Iowa

Often referred to as one of the flyover states, Iowa is generally considered to be a place where not much happens. The title, “Goodbye Iowa,” clearly references Riley’s identity crisis, revealing the end of normalcy and innocence for him. In some ways it also applies to Buffy, as she has been trying once again to have a semblance of a normal life through dating Riley. Yet, just like before, Buffy must come to the painful realization that slaying will always interfere and take over her best attempts to be a regular girl.

In the book, “Myth, Metaphor and Morality in BTVS,” Mark Field talks about how this episode is the culmination of all the themes so far: identity, indoctrination, science vs. magic, and individualism vs collectivism. He talks about how society often dictates what is normal, and that that may sometimes clash with our true, authentic self, saying, “it’s indoctrination by society which forces us to be “normal,” and forcing us to “be normal” prevents us from developing our authentic identity; and the conditioning we receive from society can be seen as stealing our true, organic identity and replacing it with one society prefers. Maggie Walsh was a metaphor for all of these aspects of society. Because she occupied multiple positions, including professor and military leader, she served as a representative of the way school, government and society in general force us in the same direction.”

Her ideology was shown in “A New Man” and it was in direct opposition to Giles, who thought Buffy and other young people should be allowed the freedom to develop on their own. Of course, when Maggie couldn’t control Buffy she tried to kill her. Now with Riley, the very definition of normal, we’re seeing what happens when someone has been controlled and told how to develop, and then what happens when their worldview begins to crumble. Field goes on to say, “Riley is not becoming an authentic adult, he’s being molded into the role society demands for him…and the result is that Riley is in bondage in the sense of not being free to develop on his own…the control is subtle rather than overt, but it’s all the more effective for that."

#buffy summers#buffy the vampire slayer#buffy btvs#tv: btvs#buffy watching#becomingbuffypodcast#btvs s5#alyson hannigan#sarah michelle gellar

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

⌞DRAGON AU⌝

... history

content warnings: interspecies relationship (implied), shape shifting / hybrids, breeding, mention of killing / hunting, mention of oviposition

Blood. Weeping. Screams.

Since ancient times, humanity has been forced to fight for its existence with various animals — tigers, wolves, bears, lions, snakes, spiders, scorpions, crocodiles... but the most serious and bloodthirsty monsters to this day are dragons.

Huge creatures of various shapes and features, capable of inhabiting everywhere, from the lava of volcanoes to the deep bottom of the oceans, depending on their characteristics. People have never been able to relax and feel safe, being in constant fear of meeting a dragon capable of destroying many lives and getting away with it. And, although people still continued to engage in agriculture and cattle breeding, they were forced to hide and run away, often leaving their settlements if a dragon was nearby, and being forced to look for as small and wide places as possible to fit and find places for animals and crops, but without risking becoming a snack.

Able to soar through the air and cross oceans, huge and tiny, spewing flame, cold, poison — dragons were not too frequent an event, but always fatal. They destroyed crops, ate animals, killed people, burned villages - and could appear anywhere. High fitness, the absence of a specific mating barrier, the absence of enemies from other creatures, a huge life span — the only thing that stopped from destruction was a small number of cubs, long mating courtship, low fertility and little interest in finding a partner against the background of large territoriality. But this did not help those who were unlucky enough to be in the territory of the dragon.

... No one knows when everything changed — according to the legend, which became the official version, one day a bloody dragon descended from the Cloud Mountains to the damp earth, being seriously wounded by their siblings; too weak and defenseless to fight, the dragon sought death, although wanted to live. They were just lucky that there was a local person not far from the place of their fall, collecting herbs in weather when no dragon would fly for fear of getting lightning; and they were no less lucky that instead of escaping, a human came out to them and helped heal a tiny (by the standards of dragons) beast, not leaving them for weeks until the dragon completely set off — but instead of flying away or devouring a person, they stayed to guard and help, not returning to Cloud Mountain.

And even when the dragon got strong enough and grew up, becoming mature and receiving eggs, they still returned to man, entrusting them with the joint incubation of future cubs and taking care of the cubs afterwards.

This is considered the first case of the formation of a bond between a human and a dragon. But then how did it become possible to change the shape? No one knows.

Although some unequivocally talk about breeding, some scientists refer to hints that the "First Dragon" descended not in the form of a huge beast, but in the form of a human, albeit with some features — therefore, the 'first tamed dragon" person helped them, because people were forced to develop collectivism and help each other to an extreme degree. Even if a person had obvious deformities and oddities, it was considered a terrible sin to pass by.

However, such a version is not considered official — although the current tamed dragons all have a human form, wild dragons are not gifted with this ability, and in the case of tamed and wild dragons mating, it has been proven that there is a possibility of the birth of a tamed, but not able to change the form of a dragon, while the birth of an untamed, but possessing a human form the dragon didn't happen.

Tamed dragons give a tamed dragon, wild dragons give a wild dragon — but mating between them is possible, as is the birth of a fertile hybrid.

But then why did the first dragon have a human form? Or, if they didn't, then why did the person help them? And how the human form was acquired, because although dragons have a high fitness, this does not mean literally copying and creating a special form, just to be convenient for people. Aliens? Did the people of the past create dragons themselves? Was the first dragon really not a dragon? No one knows.

However, it is these very tamed dragons, which appeared from nowhere, that have become a significant means of combating their own relatives. It was then that the first dragon riders appeared — a profession that exists to this day.

People who have found a special connection with the dragon and become their "masters" / "mistresses" — and warriors who can save others.

And it was then that a new page of human history began.

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

Listening to a wokie fuckhead go on and on about how dare we put Shakespeare on still because….ummm….racism….sexism…Umm wolf shit? These unfucking cultured swines honestly need to fuck off they don’t have the fucking brain power for it.

“It is a tale; full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

-– Macbeth

There's a profound irony in these pseudo-intellectuals and their extremely shallow takes on the Bard. They come from the same outrage mob mentality prevalent on Twitter, where the objective is to actively find a problem or invent a way to be offended, whether it's there or not, whether it's intended or not (Problematization).

Of course, these are the smooth-brains who insist that CRT is just about "teaching history" (it's not; or alternatively, is an obscure legal framework, which nobody is teaching - they can never decide which Motte to retreat to), and then proceed to get To Kill A Mockingbird removed because of the racism present in a compelling portrayal of history.

For people who declare themselves to be the most enlightened and awake of us all, aware of the invisible nuances the rest of us miss, they have only a few superficial dot-points cherry-picked from the stories, missing or ignoring the point entirely.

Othello is arguably one of the earliest examinations of racism; the lead and protagonist is the dark guy, not the white guy who's manipulating him. And when he succumbs to resentment, things go tragically wrong and there's no going back. A lesson the activist elite among us could well learn.

The Taming of the Shrew is literally a farce, and almost everyone in it is a terrible person doing terrible things; you’re not supposed to admire them. It’s like “Ruthless People”. It's the "shrew" herself who is the sympathetic character. In Macbeth, it's Lady Macbeth who motivates and pulls the strings of the entire thing, exercising her power and influence over her husband. (It actually reminds me, without the machiavellian aspects, of how Obama bragged that he ran every presidential decision by Michelle, effectively giving her the power of the Presidency; without the credit for success, but also with immunity to the consequences for failure. Women have always held power and influence, even when it wasn't in formal seats, in many ways more than the men who acted on their behalf.)

Romeo and Juliet is literally about two people who die directly as a result of tribalism and their families' inability to put aside old disputes.

https://www.magicalquote.com/60-life-lessons-from-william-shakespeare-quotes/

https://brightdrops.com/shakespeare-quotes

https://www.buzzfeed.com/sarahgalo/happy-451st-birthday-to-the-bard

Across all his works, one of the most consistent lessons is that people are complicated and flawed, because that is humanity. People can do good in their own way, and others who have good intentions can do bad things by circumstance, misunderstanding or manipulation. This is unforgivable to Wokistanians, as they hold fast to two-dimensional stereotypes and cliches. In order to sustain a war of "us vs them" collectivism based on superficial attributes, the individual must be kept at arm's length. It cannot and does not deal with an individual except through membership in its power categories.

Another is that of personal responsibility, which is outright rejected in preference to exalted helplessness in the face of a numinous "system," requiring wholesale emancipatory insurrection.

"The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,

But in ourselves, that we are underlings."

-- Julius Caesar

It's ironic in an almost Shakespearean way, that the people who could most stand to learn from Shakespeare are the shrill scolds who reject him.

"Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind;

And therefore is winged Cupid painted blind."

-- A Midsummer Night's Dream

"This above all; to thine own self be true;

And it must follow, as the night the day,

Thou canst not then be false to any man."

-- Hamlet

"Reputation is an idle and most false imposition:

oft got without merit, and lost without deserving."

-- Othello

“Strong reasons make strong actions.”

-- King John

“Love all, trust a few, do wrong to none.”

-- All's Well That Ends Well

#ask#Shakespeare#William Shakespeare#cancel culture#woke#woke activism#wokeness as religion#cult of woke#wokeism#pseudointellectual#outrage mob#outrage culture#easily offended#religion is a mental illness

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

In his excellent book The Breakdown of Nations the maverick economist Leopold Kohr makes several stunning yet, upon reflection, commonsense observations. He points out that small states have tended to be far more culturally productive than large states, that all states go to war but that big states have disproportionately bigger wars that kill many times more people, and that by far the most stable and advantageous form of political organization is a loose confederation of states, each so small that none can dominate the rest. Kohr arrives at his conclusions by a process of reasoning by homology (viz. analogy) by analyzing many of the problems of modernity as different manifestations of the same underlying problem: the problem of excessive scale.

Most people can relate to the concept of optimal scale on an intuitive, visceral level; we know when something is abnormally big or abnormally small, and we tend to dislike abnormality. The exceptions, be they midgets or giants, are considered freaks. In living things, growth tapers off and stops when the organism has reached its optimum size. Pursuit of largest possible size is a quixotic one, like that of the farmer who tries to grow the largest-possible turnip. Terms like “jumbo shrimp” make children giggle. There was once a very successful and influential religious cult devoted to finding the optimum in all things: the Greek cult of Apollo, with its motto of μηδὲν ἄγαν — “Nothing in excess.” Excess is never without cost, excessive size is no exception, and beyond a certain point the cost of excessive size becomes exorbitant.

This point is lost on very few people, virtually all of whom happen to be politicians. For them, there is simply no limit to how big their nation-state should be allowed to become. When they think “bigger” they automatically think “better” and “more powerful,” in spite of much evidence to the contrary. Incapable of understanding the concept of first diminishing, then negative economies of scale, they cannot understand why increased defense spending results in more military defeats, or why increased spending on education causes ignorance to spread and test scores to plummet, or why increased spending on health care results in an increase in morbidity and mortality. In their headlong pursuit of “growth” they work themselves into the cul de sac of excessive size, a predicament from which there is no escape except through collapse.

Kohr defines the effect of excessive size using the Law of Diminishing Productivity: if one adds variable units of any factor of production to a fixed quantity of another, at some point the effect of adding one more variable unit will decrease productivity rather than increase it.

The best example of this law in action we currently have is with population as the variable unit and Earth as the fixed unit. Indications are that we passed this point some time ago, but the population continues to grow because, although productivity is being steadily diminished, it is still above zero. Kohr’s ideas lived on in the work of E. F. Schumacher and others, but they have failed to gain enough traction to reverse the march to gigantism, followed inexorably by collapse.

(...)

According to Kohr, the small state has much to recommend it, especially if it exists in a loose but relatively peaceful confederation with other small states, none of them large enough to dominate the others (bringing to mind the outsized influence of Germany in the European Union).

He points out that the smaller the sovereign group, the greater is each individual’s share of personal sovereignty. An Icelander’s share of state sovereignty is over four thousand times that of a Chinese: a sovereign giant compared to a sovereign dwarf. A sovereign dwarf is a mere statistic, a depersonalized average man and an embodiment of the god of collectivism, and such impersonal collectivism is, to Kohr, ignoble. To him, nobility (by which he means nobility of spirit) is never just “doing your job” in some abstract and perfunctory way, but engaging with each person, and democracy does not exist wherever a direct conversation between the ruler and any one of his subjects is no longer possible. To test whether you are living in a democracy, go and demand to see the president. If you find yourself questioned by the secret police and put under surveillance, or arrested and jailed, or put in a psychiatric hospital, then there is a teensy-weensy chance that you are not living in a democracy.

Although Kohr’s work can be read as a warning of the dire consequences of excessive scale at every level, it can also be viewed as a message of hope for the future. The waning of the industrial age is making the maintenance requirements of gigantic political entities impossible to meet, and as they decay, collapse and devolve into much smaller and more local entities, the world may yet see a rebirth of states small enough to grant their members a reasonable share of personal sovereignty. Some of them may even become able to aspire to true, direct democracy and find ways to renew themselves, whereas the larger states can now only blunder along, biding their time. Kohr tried to get at this hopeful vision with this charming quote from André Gide: “Je crois à la vertu du petit nombre; le monde sera sauvé par quelques-uns.” [“I believe in the virtue of the small number; the world will be saved by the few.”]

(...)

Here are some examples of dictatorial successes in holding non-viable nation-states together. The authoritarian Josip Broz Tito held Yugoslavia together and made it a pleasant place. Once it was left with-out his unifying presence, Yugoslavia descended into ethnic cleansing, genocide and civil war. Saddam Hussein succeeded in creating a prosperous Iraq out of disparate bits and pieces of the Ottoman Empire, with a large, thriving, well-educated middle class. Once he was over-thrown, the country (if it can still be called that) descended into civil war, and is now an impoverished ghost of itself characterized by misery and permanent unrest. Muammar Qaddafi achieved similarly stellar results for Libya, and was for a time regarded as an honest broker and a peacemaker throughout Africa. He launched communications satellites in an attempt to break France Telecom’s stranglehold on that continent.

But he was overthrown, and now Libya is a war zone and a dangerous place for Washington’s ambassadors. Hafez al-Assad (father of Bashar, the current dictator) held Syria together for thirty-odd years, but now it has descended into civil war.

Yes, dictatorship is at best problematic. But any nascent nation-state that decides to give democracy a try is sure to confront many problems as well. To start with, democracy is a tradition that cannot be conjured up on the spot or imported and installed like a piece of industrial machinery; it has to evolve in place. The best, oldest, most stable democracies have tribal roots and rely on direct democracy at the local level. A representative democracy is a degenerate case open to many kinds of corruption and abuse that may become bad enough to invalidate the entire project. In a representative democracy the electoral process involves forming national political parties which tend to become financially dependent on the dominant class in a process that disenfranchises those whose only ambition is to pursue local interests.

On the other hand, violent confrontations over votes are likely when the elected representatives represent specific districts. An attempt to institute granular political representation in an already weak state dominated by non-state actors is a prescription for political violence.

Add to this the fact that, in a heterogenous population, proportional representation gives the more powerful and numerous tribes the upper hand over the smaller, minority tribes, which do not readily accede to such an arrangement and look for opportunities to make mischief.

-- Dmitry Orlov, The Five Stages of Collapse

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juno Steel and Sam Vimes are the same person

Well, no. Not actually. That's what I want to talk about.

They do have a lot of similarities: both have an intense relationship with their city, which they understand to be corrupted down to its core but which they nevertheless couldn't see themselves leaving even after it repeatedly almost killed them; both were raised (a generous word when applied to Sarah, but still) by their mothers with no input from a father; both are or had been cops in a failing, corrupted system; both have a moral core of, if you'll forgive the wordplay, steel, to the point where their moral outrage is seen as a defining trait; both are very smart, but tend to rush in; both have had symbolic eye injuries at one point; both were manipulated by the ruler of their city.

Same person, except their arcs end in incredibly different places, don't they? Why is that?

That's because The Penumbra Podcast and The Watch have different themes at their core.

Let's tackle their arcs individually, shall we? Spoiler alert.

We meet Sam Vimes at the absolute bottom, in a ditch, raving about Ankh-Morpork in a monologue that is similar in meaning, if not in articulation, to Juno's monologues about Hyperion City. He's an alcoholic. The Watch is a joke and has next to no actual power, consisting of only Sam, Nobby, and Colon. Their fourth man's funeral had just happened.

Yet, at the end of The Watch series, Sam Vimes is the richest man in the city, a Duke, with a loving wife and a son, extremely respected and having reformed the Watch to a point where it is efficient and the most diverse organization in the city. The cops he trained are in high demand in the country and are called sammies. He has shaken hands with kings and is highly respected by the Patrician.

How did he get there?

That's where The Watch's theme comes in: Sam Vimes is a very smart man, but he's only ever able to make actual change in the city due to the support and help of other people. In Guards! Guards!, those people are able to be counted in one hand, but some of them are also powerful: Sybil is the richest woman in the city, and one of the noblest; Vetinari, who impeded Vimes' investigation at first, ends up helping him out of the dungeon and rewarding the Watch at the end of the book; Carrot is the king by all rights, except for the fact that he doesn't want to be. Vimes'd go spare.

They are just people. But they're people who, at least at times, actively try to make the city better. And Vimes' support only grows with time.

Powerful people listen to Vimes. Most of them are even trying to do good independently of him, to make things better one step at a time. Goodness is something that is built slowly in places like Ankh-Morpork.

Sam Vimes tries, again and again, to do things on his own, only to be thwarted when people keep going with him. This isn't just his fight. He only gets to grow when relying on other people.

And he does grow. He stops drinking, and finds purpose in reforming the Watch with Carrot and Sybil's help, and then with the help of a dozen other people. He unlearns his prejudice.

There is a case to be made that, in staying in Ankh-Morpork and dedicating so much of himself to it, to the point where it more than once endangers his family, Sam never gets to stop overworking himself. He doesn't know how to take a holiday or a break. He canonically leaves Sybil alone for longer than she'd like.

It's impossible to imagine Sam Vimes retiring out of his own free will. That is not a good thing.

But, on the whole, he's in a much better place than at the beginning- and not only him, but the city; and not only the city, but the world. The Watch is a love letter to collectivism, even if it doesn't seem like that at times.

It says if enough people get up and do the job that's in front of them, the world gets better for it.

That is not the core of The Penumbra Podcast.

Now that we've seen what happens to Vimes, it's pretty easy to spot the difference when it comes to Juno's arc. While The Watch believes in organizations and communities, the junoverse believes in families and friends. While it does touch on the whole, it puts its faith on those small human connections.

Hyperion doesn't get better because a lot of people decide to work hard on it. Hyperion gets better because of a manipulator who could have ended humanity as we understand it and who believed Good meant taking people's lives off their hands. The result is almost collateral to Ramses' plan. And that's what drives Juno off world.

We don't actually see Juno at his worse. We know he drinks, that he's depressed and passively suicidal, that he drives almost everyone away, but his time in ditches is only referred to. When we meet him, Juno is mostly functional.

While Vimes' Watch was powerless, the police force in junoverse is very much powerful, if intensely corrupt, which is why Juno couldn't stay as a cop and still be a likable protagonist.

Whille powerful people do help him, it's often in their own interest: Vicky wants him to solve a case for her; Ramses wants him to assuage his guilt. Most often, the people who do help him with little to no ulterior motive are Rita, who's an incredible hacker, but in no way powerful beyond that as far as we know; Peter Nureyev, who does not want a whole planet to be wiped but really doesn't want to stay and work on its other problems; and Jet and Buddy, who do have the ulterior motive of wanting him to work for them but deserve a honorable mention for actually coming to care about him as a person later on.

Juno is not a person to Ramses. He's a tool, and a moral compass Ramses refuses to actually look at, and a victim he feels the need to recompense.

Is it any wonder, then, that Juno's arc leads him off Hyperion? That his epiphany is that he cannot, should not, pour himself into the city until it drains him dry? (There can be some symbolism in the test of generosity, if you look.) Juno grows by prioritizing himself and the people he cares about (Rita, at that point it's mostly Rita) above the city that has given him nothing.

Neither narrative is worth more or less than the other. Stay and help- a purpose can give you reason to work on yourself, and it is possible to make things better and Go, make sure you won't die here, the only reason you need is that other people care about you, and that you can learn to care about yourself are both very important messages.

Junoverse is far from over, though. Who knows what it will say when everything done with?

#alex wont shut up#discworld#the penumbra podcast#tpp#juno steel#sam vimes#meta#junoverse#this is a post for an audience of one

34 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Timothy Snyder

Published Jan. 9, 2021 - Updated Jan. 10, 2021, 10:12 a.m. ET

When Donald Trump stood before his followers on Jan. 6 and urged them to march on the United States Capitol, he was doing what he had always done. He never took electoral democracy seriously nor accepted the legitimacy of its American version.

Even when he won, in 2016, he insisted that the election was fraudulent — that millions of false votes were cast for his opponent. In 2020, in the knowledge that he was trailing Joseph R. Biden in the polls, he spent months claiming that the presidential election would be rigged and signaling that he would not accept the results if they did not favor him. He wrongly claimed on Election Day that he had won and then steadily hardened his rhetoric: With time, his victory became a historic landslide and the various conspiracies that denied it ever more sophisticated and implausible.

People believed him, which is not at all surprising. It takes a tremendous amount of work to educate citizens to resist the powerful pull of believing what they already believe, or what others around them believe, or what would make sense of their own previous choices. Plato noted a particular risk for tyrants: that they would be surrounded in the end by yes-men and enablers. Aristotle worried that, in a democracy, a wealthy and talented demagogue could all too easily master the minds of the populace. Aware of these risks and others, the framers of the Constitution instituted a system of checks and balances. The point was not simply to ensure that no one branch of government dominated the others but also to anchor in institutions different points of view.

In this sense, the responsibility for Trump’s push to overturn an election must be shared by a very large number of Republican members of Congress. Rather than contradict Trump from the beginning, they allowed his electoral fiction to flourish. They had different reasons for doing so. One group of Republicans is concerned above all with gaming the system to maintain power, taking full advantage of constitutional obscurities, gerrymandering and dark money to win elections with a minority of motivated voters. They have no interest in the collapse of the peculiar form of representation that allows their minority party disproportionate control of government. The most important among them, Mitch McConnell, indulged Trump’s lie while making no comment on its consequences.

Yet other Republicans saw the situation differently: They might actually break the system and have power without democracy. The split between these two groups, the gamers and the breakers, became sharply visible on Dec. 30, when Senator Josh Hawley announced that he would support Trump’s challenge by questioning the validity of the electoral votes on Jan. 6. Ted Cruz then promised his own support, joined by about 10 other senators. More than a hundred Republican representatives took the same position. For many, this seemed like nothing more than a show: challenges to states’ electoral votes would force delays and floor votes but would not affect the outcome.

Yet for Congress to traduce its basic functions had a price. An elected institution that opposes elections is inviting its own overthrow. Members of Congress who sustained the president’s lie, despite the available and unambiguous evidence, betrayed their constitutional mission. Making his fictions the basis of congressional action gave them flesh. Now Trump could demand that senators and congressmen bow to his will. He could place personal responsibility upon Mike Pence, in charge of the formal proceedings, to pervert them. And on Jan. 6, he directed his followers to exert pressure on these elected representatives, which they proceeded to do: storming the Capitol building, searching for people to punish, ransacking the place.

Of course this did make a kind of sense: If the election really had been stolen, as senators and congressmen were themselves suggesting, then how could Congress be allowed to move forward? For some Republicans, the invasion of the Capitol must have been a shock, or even a lesson. For the breakers, however, it may have been a taste of the future. Afterward, eight senators and more than 100 representatives voted for the lie that had forced them to flee their chambers.

Post-truth is pre-fascism, and Trump has been our post-truth president. When we give up on truth, we concede power to those with the wealth and charisma to create spectacle in its place. Without agreement about some basic facts, citizens cannot form the civil society that would allow them to defend themselves. If we lose the institutions that produce facts that are pertinent to us, then we tend to wallow in attractive abstractions and fictions. Truth defends itself particularly poorly when there is not very much of it around, and the era of Trump — like the era of Vladimir Putin in Russia — is one of the decline of local news. Social media is no substitute: It supercharges the mental habits by which we seek emotional stimulation and comfort, which means losing the distinction between what feels true and what actually is true.

Post-truth wears away the rule of law and invites a regime of myth. These last four years, scholars have discussed the legitimacy and value of invoking fascism in reference to Trumpian propaganda. One comfortable position has been to label any such effort as a direct comparison and then to treat such comparisons as taboo. More productively, the philosopher Jason Stanley has treated fascism as a phenomenon, as a series of patterns that can be observed not only in interwar Europe but beyond it.

My own view is that greater knowledge of the past, fascist or otherwise, allows us to notice and conceptualize elements of the present that we might otherwise disregard and to think more broadly about future possibilities. It was clear to me in October that Trump’s behavior presaged a coup, and I said so in print; this is not because the present repeats the past, but because the past enlightens the present.

Like historical fascist leaders, Trump has presented himself as the single source of truth. His use of the term “fake news” echoed the Nazi smear Lügenpresse (“lying press”); like the Nazis, he referred to reporters as “enemies of the people.” Like Adolf Hitler, he came to power at a moment when the conventional press had taken a beating; the financial crisis of 2008 did to American newspapers what the Great Depression did to German ones. The Nazis thought that they could use radio to replace the old pluralism of the newspaper; Trump tried to do the same with Twitter.

Thanks to technological capacity and personal talent, Donald Trump lied at a pace perhaps unmatched by any other leader in history. For the most part these were small lies, and their main effect was cumulative. To believe in all of them was to accept the authority of a single man, because to believe in all of them was to disbelieve everything else. Once such personal authority was established, the president could treat everyone else as the liars; he even had the power to turn someone from a trusted adviser into a dishonest scoundrel with a single tweet. Yet so long as he was unable to enforce some truly big lie, some fantasy that created an alternative reality where people could live and die, his pre-fascism fell short of the thing itself.

Some of his lies were, admittedly, medium-size: that he was a successful businessman; that Russia did not support him in 2016; that Barack Obama was born in Kenya. Such medium-size lies were the standard fare of aspiring authoritarians in the 21st century. In Poland the right-wing party built a martyrdom cult around assigning blame to political rivals for an airplane crash that killed the nation’s president. Hungary’s Viktor Orban blames a vanishingly small number of Muslim refugees for his country’s problems. But such claims were not quite big lies; they stretched but did not rend what Hannah Arendt called “the fabric of factuality.”

One historical big lie discussed by Arendt is Joseph Stalin’s explanation of starvation in Soviet Ukraine in 1932-33. The state had collectivized agriculture, then applied a series of punitive measures to Ukraine that ensured millions would die. Yet the official line was that the starving were provocateurs, agents of Western powers who hated socialism so much they were killing themselves. A still grander fiction, in Arendt’s account, is Hitlerian anti-Semitism: the claims that Jews ran the world, Jews were responsible for ideas that poisoned German minds, Jews stabbed Germany in the back during the First World War. Intriguingly, Arendt thought big lies work only in lonely minds; their coherence substitutes for experience and companionship.

In November 2020, reaching millions of lonely minds through social media, Trump told a lie that was dangerously ambitious: that he had won an election that in fact he had lost. This lie was big in every pertinent respect: not as big as “Jews run the world,” but big enough. The significance of the matter at hand was great: the right to rule the most powerful country in the world and the efficacy and trustworthiness of its succession procedures. The level of mendacity was profound. The claim was not only wrong, but it was also made in bad faith, amid unreliable sources. It challenged not just evidence but logic: Just how could (and why would) an election have been rigged against a Republican president but not against Republican senators and representatives? Trump had to speak, absurdly, of a “Rigged (for President) Election.”

The force of a big lie resides in its demand that many other things must be believed or disbelieved. To make sense of a world in which the 2020 presidential election was stolen requires distrust not only of reporters and of experts but also of local, state and federal government institutions, from poll workers to elected officials, Homeland Security and all the way to the Supreme Court. It brings with it, of necessity, a conspiracy theory: Imagine all the people who must have been in on such a plot and all the people who would have had to work on the cover-up.

Trump’s electoral fiction floats free of verifiable reality. It is defended not so much by facts as by claims that someone else has made some claims. The sensibility is that something must be wrong because I feel it to be wrong, and I know others feel the same way. When political leaders such as Ted Cruz or Jim Jordan spoke like this, what they meant was: You believe my lies, which compels me to repeat them. Social media provides an infinity of apparent evidence for any conviction, especially one seemingly held by a president.

On the surface, a conspiracy theory makes its victim look strong: It sees Trump as resisting the Democrats, the Republicans, the Deep State, the pedophiles, the Satanists. More profoundly, however, it inverts the position of the strong and the weak. Trump’s focus on alleged “irregularities” and “contested states” comes down to cities where Black people live and vote. At bottom, the fantasy of fraud is that of a crime committed by Black people against white people.