#la enigma

Quote

¿Y al final que poseíamos de verdad? Tal vez solo el amor que podíamos profesarnos...

Gabriel, Filosofía en la celda y otras confesiones.

0 notes

Text

GIRLS HERE!! 💪🌸

Second pic was from a while back but with some revision!

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

e-nìg-ma

Dal greco àinigma, derivato del verbo ainìssesthai parlare per enigmi, a sua volta da àinos racconto, favola.

Questa parola è vertiginosa: ci descrive un mistero profondo, pieno di strette ambiguità, un rovello che impegna duramente l’intelletto. Ma il suo primo significato è più ameno di quanto il colore e l’uso consueto di questa parola non suggerisca; infatti, indica in primis l’indovinello.

Non dobbiamo farci fuorviare dal fatto che ‘indovinello’ è un diminutivo, e ci pare subito qualcosa di simpatico. La storia di brevi componimenti poetici allusivi, che sfidano a scoprire il loro oggetto coperto, è molto antica e decisamente seria. Basti pensare alla figura mitica della Sfinge, che fuori Tebe proponeva i suoi enigmi ai viaggiatori, sbranandoli se non riuscivano a risolverli.

Fra l’indovinello e la generica frase oscura il passo è breve: si può notare che il professore parla per enigmi, saggiando l’acume dei suoi studenti, nell’enigma del referto medico è nascosto il responso atteso con tanta apprensione, e la risposta enigmatica ci lascia nel dubbio.

Ed è dall’oscurità di questi detti che oggi l’enigma prende il significato più generale di fatto inspiegabile, di mistero. Può essere un enigma la costruzione in fisica di una teoria unificata delle forze, può essere un enigma il comportamento indecifrabile di una persona, così come la dinamica di un delitto.

Non a caso la celebre macchina crittografica usata dai nazisti durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale fu chiamata proprio ‘Enigma’; con una vena di compiacimento, questo nome attinge all’immaginario millenario di uno sforzo mentale vano davanti alle fitte tenebre di un segreto - evidente ma impenetrabile. O quasi.

unaparolaalgiorno.it/significato/enigma

#greco#etimologia#parole#parola#la bellezza del linguaggio#linguaggio#lingue antiche#enigma#articolo

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

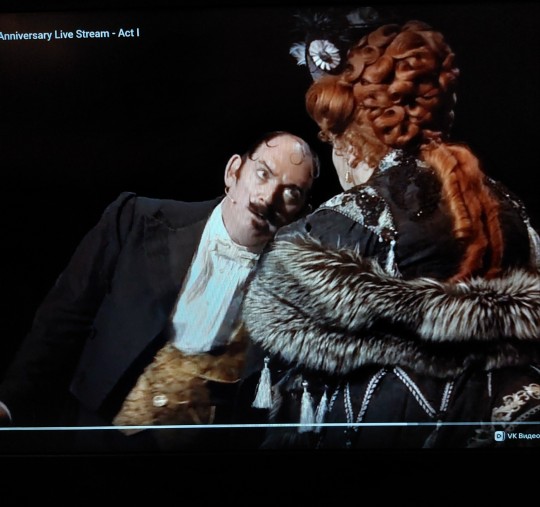

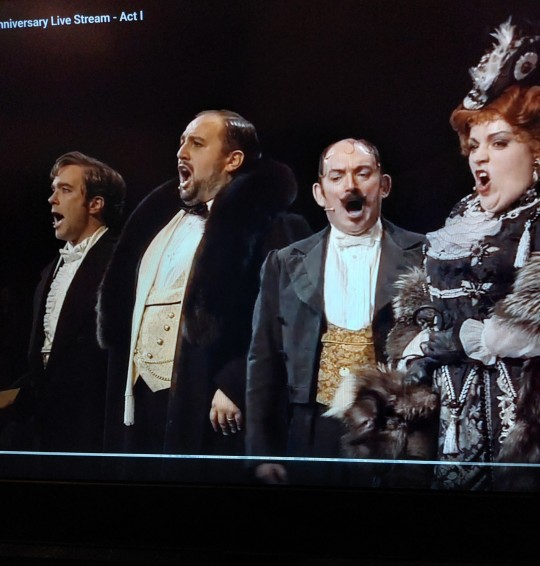

The Phantom: I am biggest drama queen

Carlotta : *I* le biggest drama queeén

.

.

.

I present to you

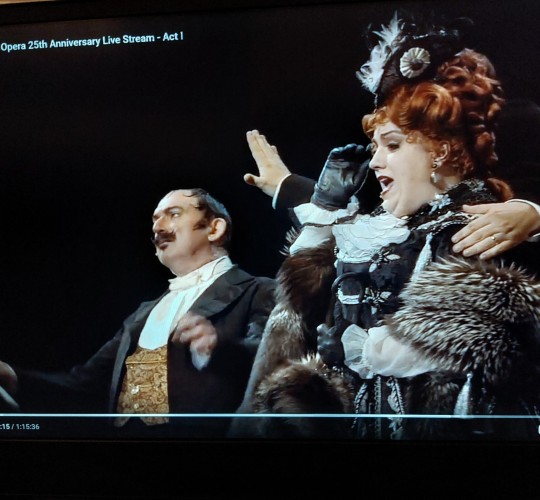

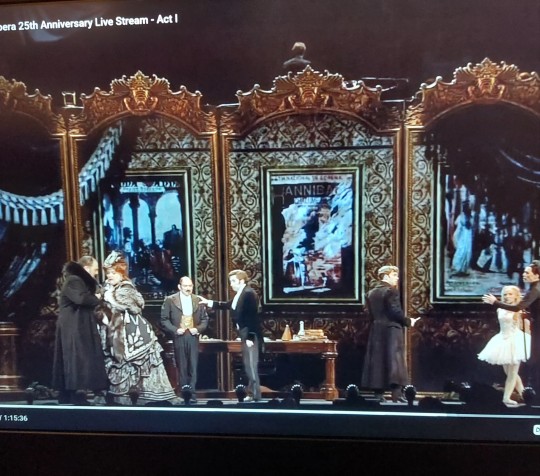

Barry James

As

Monsieur Richard Firmin

25th Poto Anniversary

This poor man. No wonder he's struggling by the end of it. He's struggling now.

Look at all that sass contained within those twirly hairs of his.

Almost hit. Good dodging skills. Dealing with aggression in the workplace.

Can anyone catch the eye-roll here? He uses them like all that passive aggression will give Carlotta a hemorrhage.

Does it look like pacification here? Gilles, you are the last wall before he's headbutting everyone, including himself.

This lad. He's so sassy and thank you Barry James with playing him an absolute fed-up man who has little to no patience for all this parafinalia.

He just wants his warm office and a tidy profit. Is that so much to ask?

More pictures because loOOk

THE *SILENT* SEETHING

The second image

Andre, this is your fault.

#poto#phantom of the opera#the phantom of the opera#poto 25th#poto 25#phantom 25#Phantom of the Opera 25th anniversary#poto 25th anniversary#Barry James#Richard Firmin#Poto The managers#The managers#Enigma posts#Poto shitpost#Drama queen poto#erik#la carlotta#carlotta giudicelli

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me, showing up late to work tomorrow & explaining that I was up late trying to solve a portuguese feather riddle in minecraft

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guillermo and Derek should kiss I think.

#enigma musings#I have only seen 1 episode of s5 so far but this is my take away#there are only 5 fics about them on ao3 and I need that number raised immediately#wwdits#guillermo de la cruz#what we do in the shadows

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

La serata perfetta non esi..

Ah no

#a random#buona serata#sherlock holmes wanna be#hidden games#gioco#enigma#la serata perfetta#panzerotti#fatti da me

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

🃏

#tarot#aesthetic#mentally tired#mentally fucked#depressing quotes#mentally exhausted#drugs aesthetic#iv drugs#edgy theme#mentally unwell#i am unstable#la mort#dc comics#dc universe#harley quinn#tarot reading#tarot cards#tarot aesthetic#aestethic#gaea#enigma#batman

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Todo dirigir la atención hacia una cierta realidad, especialmente cuando esta realidad es la humana, muestra que se ha convertido en problema. Era un gran paso, nunca antes dado –que sepamos- pues la tragedia poética mostraba la desesperada situación del hombre en concreto, de un hombre perseguido por el destino bajo la sombra de un oscuro Dios y en ella se reclamaba, especialmente en la de Edipo, un conocimiento. La Esfinge había presentado a Edipo un enigma cuya solución encontró inmediatamente: el hombre. Mas Edipo no sabía que el hombre es a su vez un enigma; Sócrates sí, y por eso hizo de este enigma el centro de su continuo filosofar.»

María Zambrano: Persona y democracia, la historia sacrificial. Ediciones Siruela, pags.139-140. Madrid, 2004

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dies-irae-1

#maría zambrano#persona y democracia#la historia sacrificial#tragedia#tragedia griega#tragedia poética#tragedia clásica#edipo#esfinge#sócrates#hombre#ser humano#enigma#razón-poética#conocimiento#filosofar#filosofía española#filosofía del exilio#filosofía contemporánea#teo gómez otero#edipo y la esfinge#moreau

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

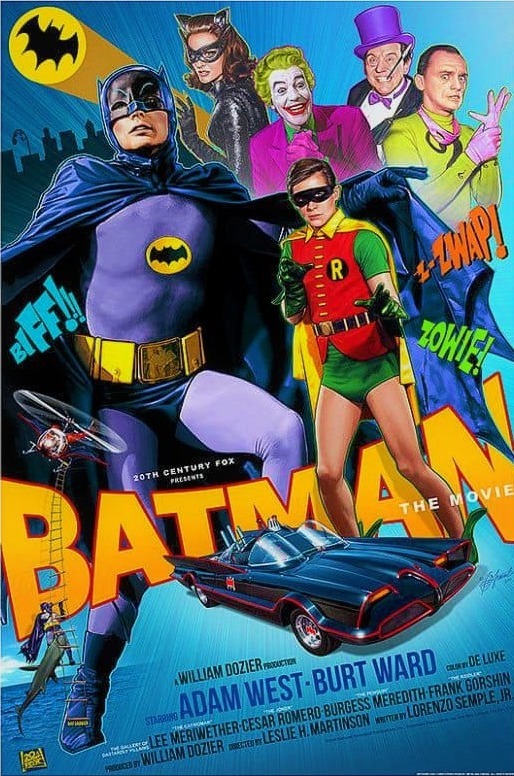

Batman (1966 - 1968)

Batman (Adam West)

Robin (Burt Ward)

Joker o El Guasón (César Romero)

El Acertijo/Enigma (The Riddler) (Frank Gorshin y John Astin)

El Pingüino (Burgess Meredith)

Gatubela (Julie Newmar en la 1 ª y 2 ª temporada, por Eartha Kitt en la 3ª temporada y por Lee Meriwether en la película de 1966)

La serie giraba en torno a las aventuras de que viven Batman (interpretado por Adam West) y su ayudante Robin (interpretado por Burt Ward) en su lucha contra el crimen en Gotham City. La identidad secreta de Batman es la del elegante «filántropo millonario» Bruce Wayne, quien vivía en la Mansión Wayne, en las afueras de la ciudad, con su joven entrenado Dick Grayson, el que secretamente era Robin, su fiel mayordomo Alfred (Alan Napier), y la tía Harriet Cooper (Madge Blake). Ayudaban a Batman: Batgirl (Yvonne Craig), el comisario de policía Gordon (Neil Hamilton) y el jefe de policía O'Hara (Stafford Repp).

#Batman#Ciudad Gotica#Batman (Adam West)#Robin (Burt Ward)#Joker o El Guasón (César Romero)#El Pingüino (Burgess Meredith)#El Acertijo/Enigma (The Riddler) (Frank Gorshin y John Astin)#Gatubela (Julie Newmar en la 1 ª y 2 ª temporada por Eartha Kitt en la 3ª temporada y por Lee Meriwether en la película de 1966)#cine de culto#60s film#60s nostalgia#60s vintage#Ron Cartavio#Hot Topic#cigarros pall mall#vans classics#vans old school#cervezas y chicas

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

conflicting statements

#i wanna write these so bad#obsessed with dico actually#he’s like an enigma#brandon dicamillo#dico#jackass#cky2k#johnny knoxville#bam margera#dico fic#brandon dicamillo fic#viva la bam#mtv#cky#cky crew

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cebras: ¿Rayas blancas o rayas negras?

Se conocen como cebra1 a tres especies del género Equus propias de África —Equus quagga (cebra común; con cinco subspecies),2 Equus zebra (cebra de montaña; dos subespecies)2 y Equus grevyi (cebra de Grevy)3— cuya característica más distintiva es su coloración a base de rayas blancas sobre un fondo negro.4 Las cebras tienen un total de cuarenta dientes: doce incisivos que utilizan para cortar y arrancar trozos de vegetación, cuatro caninos, doce premolares y doce molares, todos utilizados para moler el alimento antes de tragárselo.[cita requerida]Las cebras tienen un excelente sentido de la vista. Se cree que pueden ver en color. Como muchos ungulados, las cebras tienen los ojos a los lados de la cabeza, dándole un amplio ángulo visual. Las cebras también tienen visión nocturna, a pesar de que no es tan avanzada como la de la mayoría de sus predadores, pero su buen oído lo compensa.

#El Enigma de las Cebras: ¿Rayas blancas o rayas negras?#¿Esta es la imagen y algunos datos (O no) la “Historia” la pones tú? ¡La tuya! ¿Lo harás...?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

'It was the early hours of 16 July 1945, and Robert Oppenheimer was waiting in a control bunker for a moment that would change the world. Around 10km (6 miles) away, the world's first atomic bomb test, codenamed "Trinity", was set to proceed in the pale sands of the Jornada del Muerto desert, in New Mexico.

Oppenheimer was a picture of nervous exhaustion. He was always slender, but after three years as director of "Project Y", the scientific arm of the "Manhattan Engineer District" that had designed and built the bomb, his weight had dropped to just over 52kg (115lbs). At 5ft 10in (178cm), this made him extremely thin. He'd slept only four hours that night, kept awake by anxiety and his smoker's cough.

That day in 1945 is one of several pivotal moments in Oppenheimer's life described by the historians Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin in their 2005 biography American Prometheus, which provided the basis for the new movie biopic Oppenheimer, released 21 July in the US.

In the final minutes of the countdown, as Bird and Sherwin report, an army general observed Oppenheimer's mood at close-quarters: "Dr. Oppenheimer... grew tenser as the last seconds ticked off. He scarcely breathed..."

The explosion, when it came, outshone the Sun. With a force matching 21 kilotonnes of TNT, the detonation was the largest ever seen. It created a shockwave that was felt 160km (100 miles) away. As the roar engulfed the landscape and the mushroom cloud rose in the sky, Oppenheimer's expression relaxed into one of "tremendous relief". Minutes later, Oppenheimer's friend and colleague Isidor Rabi caught sight of him from a distance: "I’ll never forget his walk; I’ll never forget the way he stepped out of the car... his walk was like High Noon... this kind of strut. He had done it."

In interviews conducted in the 1960s, Oppenheimer added a layer of gravitas to his reaction, claiming that, in the moments after the detonation, a line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, had come into his mind: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

In the following days, his friends reported he seemed increasingly depressed. "Robert got very still and ruminative during that two-week period," one recalled, "because he knew what was about to happen." One morning he was heard lamenting (in condescending terms) the imminent fate of the Japanese: "Those poor little people, those poor little people." But only days later, he was once again nervous, focussed, exacting.

In a meeting with his military counterparts, he seemed to have forgotten all about the "poor little people". According to Bird and Sherwin, he was instead fixated on the importance of the right conditions for the bomb drop: "Of course, they must not drop it in rain or fog… Don’t let them detonate it too high. The figure fixed on is just right. Don’t let it go up [higher] or the target won’t get as much damage." When he announced the successful bombing of Hiroshima to a crowd of his colleagues less than a month after Trinity, one onlooker noticed the way Oppenheimer "clasped and pumped his hand over his head like a victorious prizefighter". The applause "practically raised the roof".

Oppenheimer was the emotional and intellectual heart of the Manhattan Project: more than any other single person he had made the bomb a reality. Jeremy Bernstein, who worked with him after the war, was convinced that nobody else could have done it. As he wrote in his 2004 biography, A Portrait of an Enigma, "If Oppenheimer had not been the director at Los Alamos, I am persuaded that, for better or worse, the Second World War would have ended... without the use of nuclear weapons."

The variety of Oppenheimer's reported reactions as he witnessed the fruition of his labours, not to mention the pace with which he moved through them, might seem bewildering. The combination of nervous fragility, ambition, grandiosity and morbid gloom are hard to square in a single person, especially one so instrumental in the very project provoking these responses.

Bird and Sherwin also call Oppenheimer an "enigma": "A theoretical physicist who displayed the charismatic qualities of a great leader, an aesthete who cultivated ambiguities." A scientist, but also, as another friend once described him "a first-class manipulator of the imagination".

By Bird and Sherwin's account, the contradictions in Oppenheimer's character – the qualities that have left both friends and biographers at a loss to explain him – seem to have been present from his earliest years. Born in New York City in 1904, Oppenheimer was the child of first-generation German Jewish immigrants who had become wealthy through the textiles trade. The family home was a large apartment on the Upper West Side with three maids, a chauffeur, and European art on the walls.

Despite this luxurious upbringing, Oppenheimer was recalled as unspoiled and generous by childhood friends. A school friend, Jane Didisheim, remembered him as someone who "blushed extraordinarily easily", who was "very frail, very pink-cheeked, very shy...", but also "very brilliant". "Very quickly everybody admitted that he was different from all the others and superior," she said.

By the age of nine, he was reading philosophy in Greek and Latin, and was obsessed with mineralogy – roaming Central Park and writing letters to the New York Mineralogical Club about what he found. His letters were so competent that the Club mistook him for an adult and invited him to make a presentation. This intellectual nature contributed to a degree of solitude in the young Oppenheimer, write Bird and Sherwin. "He was usually preoccupied with whatever he was doing or thinking," recalled a friend. He was uninterested in conforming to gender expectations – taking no interest in sports or the "rough and tumble of his age-group" as his cousin put it; "He was often teased and ridiculed for not being like other fellows." But his parents were convinced of his genius.

"I repaid my parents’ confidence in me by developing an unpleasant ego," Oppenheimer later commented, "which I am sure must have affronted both children and adults who were unfortunate enough to come into contact with me." "It’s no fun," he once told another friend, "to turn the pages of a book and say, 'yes, yes, of course, I know that'."

When he left home to study chemistry at Harvard University, the fragility of Oppenheimer's psychological make-up was exposed: his brittle arrogance and thinly-masked sensitivity appearing to serve him poorly. In a letter from 1923, published in a 1980 collection edited by Alice Kimbal Smith and Charles Weiner, he wrote: "I labour and write innumerable theses, notes, poems, stories and junk… I make stenches in three different labs…I serve tea and talk learnedly to a few lost souls, go off for the weekend to distill low grade energy into laughter and exhaustion, read Greek, commit faux pas, search my desk for letters, and wish I were dead. Voila."

Subsequent letters collated by Smith and Weiner reveal that the problems continued through his post-graduate studies, in Cambridge, England. His tutor insisted on applied laboratory work, one of Oppenheimer's weaknesses. "I am having a pretty bad time," he wrote in 1925. "The lab work is a terrible bore, and I am so bad at it that it is impossible to feel that I am learning anything." Later that year, Oppenheimer's intensity led him close to disaster when he deliberately left an apple, poisoned with laboratory chemicals, on his tutor's desk. His friends later speculated he could have been driven by envy and feelings of inadequacy. The tutor didn't eat the apple but Oppenheimer's place at Cambridge was threatened and he kept it only on condition that he see a psychiatrist. The psychiatrist diagnosed psychosis but then wrote him off, saying that treatment would do no good.

Recalling that period, Oppenheimer would later report that he seriously contemplated suicide over the Christmas holidays. The following year, during a visit to Paris, his close friend Francis Fergusson told him he had proposed to his girlfriend. Oppenheimer responded by attempting to strangle him: "He jumped on me from behind with a trunk strap," Fergusson recalled, "and wound it around my neck... I managed to pull aside and he fell on the ground weeping."

It seems that where psychiatry failed Oppenheimer, literature came to the rescue. According to Bird and Sherwin, he read Marcel Proust's A La Recherché du Temps Perdu while on a walking holiday in Corsica, finding in it some reflection of his own state of mind that reassured him and opened a window on a more compassionate mode of being. He learned by heart a passage from the book about "indifference to the sufferings one causes", being "the terrible and permanent form of cruelty". The question of attitude towards suffering would remain an abiding interest, guiding Oppenheimer's interest in spiritual and philosophical texts throughout his life and eventually playing a significant role in the work that would define his reputation. A comment he made to his friends on this same holiday seems prophetic: "The kind of person that I admire most would be one who becomes extraordinarily good at doing a lot of things but still maintains a tear-stained countenance."

He returned to England in lighter spirits, feeling "much kinder and more tolerant", as he later recalled. Early in 1926, he met the director of the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of Göttingen in Germany, who quickly became convinced of Oppenheimer's talents as a theoretician, inviting him to study there. According to Smith and Weiner, he later described 1926 as the year of his "coming into physics". It would prove a turning point. He obtained his PhD and a postdoctoral fellowship in the year to follow. He also became part of a community that was driving the development of theoretical physics, meeting scientists who would become life-long friends. Many would ultimately join Oppenheimer at Los Alamos.

Returning to the US, Oppenheimer spent a few months at Harvard before moving to pursue his physics career in California. The tone of his letters from this period reflect a steadier, more generous cast of mind. He wrote to his younger brother about romance, and his ongoing interest in the arts.

At the University of California in Berkeley, he worked closely with experimentalists, interpreting their results on cosmic rays and nuclear disintegration. He later described finding himself "the only one who understood what this was all about". The department he eventually created stemmed, he said, from the need to communicate about the theory he loved: "Explaining first to faculty, staff, and colleagues and then to anyone who would listen ... what had been learned, what the unsolved problems were." He described himself as a "difficult" teacher at first but it was through this role that Oppenheimer honed the charisma and social presence that would carry him during his time at Project Y. Quoted by Smith and Weiner, one colleague recalled how his students "emulated him as best they could. They copied his gestures, his mannerisms, his intonations. He truly influenced their lives."

During the early 1930s, as he strengthened his academic career, Oppenheimer continued to moonlight in the humanities. It was during this period that he discovered the Hindu scriptures, learning Sanskrit in order to read the untranslated Bhagavad Gita – the text from which he later drew the famous '"Now I am become Death" quotation. It seems his interest was not just intellectual, but represented a continuation of the self-prescribed bibliotherapy that had begun with Proust in his 20s. The Bhagavad Gita, a story centred on the war between two arms of an aristocratic family, gave Oppenheimer a philosophical underpinning that was directly applicable to the moral ambiguity he confronted at Project Y. It emphasised ideas of duty, fate and detachment from outcome, emphasising that fear of consequences cannot be used as justification for inaction. In a letter to his brother from 1932, Oppenheimer specifically references the Gita and then names war as one circumstance that might offer the opportunity to put such a philosophy into practice:

"I believe that through discipline... we can achieve serenity... I believe that through discipline we learn to preserve what is essential to our happiness in more and more adverse circumstances... Therefore I think that all things which evoke discipline: study, and our duties to men and to the commonwealth, war... ought to be greeted by us with profound gratitude; for only through them can we attain to the least detachment; and only so can we know peace."

In the mid 1930s, Oppenheimer also met Jean Tatlock, a psychiatrist and physician with whom he fell in love. By Bird and Sherwin's account, Tatlock's complexity of character equalled Oppenheimer's. She was widely read and driven by a social conscience. She was described by a childhood friend as "touched with greatness". Oppenheimer proposed to Tatlock more than once but she turned him down. She is credited with introducing him to radical politics and to the poetry of John Donne. The pair continued to see each other occasionally after Oppenheimer married the biologist Katherine "Kitty" Harrison in 1940. Kitty was to join Oppenheimer at Project Y, where she worked as a phlebotomist, researching the dangers of radiation.

In 1939, physicists were far more concerned about the nuclear threat than politicians were and it was a letter from Albert Einstein that first brought the matter to the attention of senior leaders in the US government. The reaction was slow, but alarm continued to circulate in the scientific community and eventually the president was persuaded to act. As one of the preeminent physicists in the country, Oppenheimer was one of several scientists appointed to begin looking more seriously into the potential for nuclear weapons. By September 1942, partly thanks to Oppenheimer's team, it was clear that a bomb was possible and concrete plans for its development started to take shape. According to Bird and Sherwin, when he heard that his name was being floated as a leader for this endeavour, Oppenheimer began his own preparations. "I’m cutting off every communist connection," he said to a friend at the time. "For if I don’t, the government will find it difficult to use me. I don’t want to let anything interfere with my usefulness to the nation."

Einstein would later say: "The trouble with Oppenheimer is that he loves [something that] doesn’t love him – the United States government." His patriotism and desire to please clearly played a role in his recruitment. General Leslie Groves, the military leader of the Manhattan Engineer District, was the person responsible for finding a scientific director for the bomb project. According to a 2002 biography, Racing for the Bomb, when Groves proposed Oppenheimer as scientific lead, he met with opposition. Oppenheimer's "extreme liberal background" was a concern. But as well as noting his talent and his existing knowledge of the science, Groves also pointed out his "overweening ambition". The Manhattan Project's chief of security also noticed this: "I became convinced that not only was he loyal, but that he would let nothing interfere with the successful accomplishment of his task and thus his place in scientific history."

In the 1988 book The Making of the Atomic Bomb, Oppenheimer's friend Isidor Rabi is quoted as saying he thought it "a most improbable appointment", but later conceded it had been "a real stroke of genius on the part of General Groves".

At Los Alamos, Oppenheimer applied his contrarian, interdisciplinary convictions as much as anywhere. In his 1979 autobiography, What Little I Remember, the Austrian-born physicist Otto Frisch recalled that Oppenheimer had recruited not only the scientists required but also "a painter, a philosopher and a few other unlikely characters; he felt that a civilised community would be incomplete without them".

After the war, Oppenheimer's attitude seemed to change . He described nuclear weapons as instruments "of aggression, of surprise, and of terror" and the weapons industry as "the devil's work". At a meeting in October 1945, he famously told President Truman: "I feel I have blood on my hands." The President later said: "I told him the blood was on my hands – to let me worry about that."

The exchange is an arresting echo of one described in Oppenheimer's beloved Bhagavad Gita, between Prince Arjuna and the god Krishna. Arjuna refuses to fight because he believes he will be responsible for the murder of his fellows, but Krishna takes away the burden: "View in me the active slayer of these men... Arise, on fame, on victory, on kingly joys intent! They are already slain by me; be you the instrument."

During the development of the bomb, Oppenheimer had used a similar argument to assuage his own and his colleagues' ethical hesitations. He told them that, as scientists, they were not responsible for decisions about how the weapon should be used – only for doing their job. The blood, if there was any, would be on the hands of the politicians. However, it seems that once the deed was done, Oppenheimer's confidence in this position was shaken. As Bird and Sherwin relate, in his role at the Atomic Energy Commission during the post-war period, he argued against the development of further weapons, including the more powerful hydrogen bomb, which his work had paved the way for.

These efforts resulted in Oppenheimer being investigated by the US government in 1954 and having his security clearance stripped, marking the end of his involvement with policy work. The academic community came to his defence. Writing for The New Republic in 1955, the philosopher Bertrand Russell commented that the "investigation made it undeniable that he has committed mistakes, one of them from a security point of view rather grave. But there was no evidence of disloyalty or of anything that could be considered treasonable... The scientists were caught in a tragic dilemma."

In 1963, the US government presented him with the Enrico Fermi Award as a gesture of political rehabilitation, but it wasn't until 2022, 55 years after his death, that the US government overturned its 1954 decision to strip his clearance, and affirmed Oppenheimer's loyalty.

Throughout the last decades of Oppenheimer's life, he maintained parallel expressions of pride at the technical achievement of the bomb and guilt at its effects. A note of resignation also entered his commentary, with him saying more than once that the bomb had simply been inevitable. He spent the last 20 years of his life as director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, working alongside Einstein and other physicists.

As at Los Alamos, he made a point of promoting interdisciplinary work and emphasised in his speeches the belief that science needed the humanities in order to better understand its own implications, write Bird and Sherwin. To this end, he recruited a raft of non-scientists including classicists, poets, and psychologists.

He later came to consider atomic energy as a problem that outstripped the intellectual tools of its time, as, in President Truman's words, "a new force too revolutionary to consider in the framework of old ideas". In a speech made in 1965, later published in the 1984 collection Uncommon Sense, he said "I have heard from some of the great men of our time that when they found something startling, they knew it was good, because they were afraid". When talking about moments of unsettling scientific discovery, he was fond of quoting the poet John Donne: "Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone."

John Keats, another poet Oppenheimer enjoyed, coined the phrase "negative capability" to describe a common quality in the people he admired: "that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason." It seems as though it was something of this that the philosopher Russell was getting at when he wrote of Oppenheimer's "inability to see things simply, an inability which is not surprising in one possessed of a complex and delicate mental apparatus." In describing Oppenheimer's contradictions, his mutability, his continual running between poetry and science, his habit of defying simple description, perhaps we are identifying the very qualities that made him capable of pursuing the creation of the bomb.

Even in the midst of this great and terrible pursuit, Oppenheimer kept alive the "tear stained countenance" he had foretold in his 20s. The name of the "Trinity" test is thought to have come from the John Donne poem Batter my heart, three-person'd God: "That I may rise and stand, o'erthrow me, and bend/Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new." Jean Tatlock, who had introduced him to Donne, and with whom he is thought by some to have remained in love, had committed suicide the year before the test. The bomb project was marked everywhere by Oppenheimer's imagination, and by his sense of romance and tragedy. Perhaps it was overweening ambition that General Groves identified when he interviewed Oppenheimer for the job at Project Y, or perhaps it was his ability to adopt, for the time required, the idea of overweening ambition. As much as it was the result of research, the bomb was the product of Oppenheimer's ability and willingness to imagine himself as the kind of a person that could make it happen.

A chain smoker since adolescence, Oppenheimer suffered bouts of tuberculosis during his life. He died of throat cancer in 1967, at the age of 62. Two years before his death, in a rare moment of simplicity, he drew a distinction that marked out the practice of science from that of poetry. Unlike poetry, he said, "science is the business of learning not to make the same mistake again".'

#Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#American Prometheus#Jeremy Bernstein#A Portrait of an Enigma#Marcel Proust#A La Recherché du Temps Perdu#Bhagavad Gita#Jean Tatlock#John Donne#Katherine “Kitty” Harrison#Einstein#Leslie Groves#The Making of the Atomic Bomb#Isidor Rabi#What Little I Remember#Otto Frisch#Bertrand Russell#The Manhattan Project#Trinity test#Enrico Fermi Award#Uncommon Sense#John Keats#Batter my heart three person-d God

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ «Come va come va quando sei arrivato che si fa in città?» badava a ripetere lo zio. Giovancarlo rispose qualcosa di sommario. La zia chiese notizia di alcuni parenti; i parenti godevano ottima salute, ma essa stette ad ascoltare le risposte del giovane come se fossero particolari della loro morte, colla solita compassionante tenerezza. Ancora qualcuno chiese notizia dell'Università e così, esauriti subito tutti i possibili argomenti di conversazione, sopravvenne un istante di silenzio. Lo zio allora si schiarì la gola e, nell'intento di portare il discorso, come il suo magnanimo senso d'ospitalità esigeva, su un soggetto familiare a Giovancarlo, chiese alfine:

«Ma Leopardi è buono, buono?» Voleva notizie, cioè, sul valore letterario del nominato Leopardi; sapere, ad esempio, se fosse il primo il secondo il terzo scrittore italiano, se fosse più grande del Tasso o meno, come aggiunse dopo. Naturalmente non fu soddisfatto della risposta del giovane, ma seguiva lo stesso il suo discorso con finta attenzione, mentre gli occhi gradatamente gli si impicciolivano dal sonno; la zia, senza più, dopo qualche minuto piegò la testa sul petto, come era d'altronde sua costante abitudine a quell'ora della sera, e prese anzi a ronfare un tantino. Del resto anche con quell'argomento non s'andò per le lunghe. Disperando della sua causa, lo zio si guardava le unghie sporche; il cugino chiese allora dei locali notturni della capitale, scivolando nel discorso con visibile soddisfazione le parole tabarin girl champagne; l'unica obbiezione che gli si sarebbe potuto muovere avrebbe riguardato una sua cocciuta confusione dei condizionali cogli imperfetti soggiuntivi. Laddove suo padre non confondeva che fra loro, del soggiuntivo, i vari tempi; le confusioni delle due donne vertevano invece di preferenza sui generi dei nomi; quanto al fratello della zia non parlava, ovvero barbugliava in modo del tutto incomprensibile grazie alla particolare pinguedine della sua lingua, complicata dal curioso puntiglio di non voler rifiatare se non a discorso finito, avesse a esser lungo quanto voleva, sicché a costui si poteva concedere, in fatto di flessione verbale, il più largo credito. “

Tommaso Landolfi, La pietra lunare. Scene della vita di provincia, Firenze: Vallecchi, Gennaio 1944² [1ª edizione 1939]; pp. 9-11.

#La pietra lunare#letture#leggere#libri#famiglia#fuorisede#Tommaso Landolfi#Italia magica#Giacomo Leopardi#enigma#narrativa fantastica#irrealtà#mistero#fantastico#traduttori#scrittori italiani del '900#XX secolo#irrazionalità#metamorfosi#letteratura europea#ambiguità#sensualità#plenilunio#miti#intellettuali italiani del XX secolo#vita di provincia#paranormale#letteratura sperimentale#surrealismo#provincialismo

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enigma hat

4 notes

·

View notes