#liminal spatial constructs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I love backrooms content, so I wanted to list some youtube channels to I guess recommend to people who are also into backrooms stuff, even though some channels have not posted in some time, I still think their videos are cool so here they are:

Kane Pixels

Lost in the Hyperverse

A-Sync Research

Kauffman

Backrooms Series

ReverseLogic

Matt Studios

Andy R Animations

Zloxe

Return to Render

Liminal Spatial Constructs

#the backrooms#backrooms#kane pixels#lost in the hyperverse#a-sync research#kauffman#kauffman backrooms#backrooms series#reverselogic#matt studios#andy r animations#zloxe#return to render#liminal spatial constructs#youtube#also if someone wants to recommend me some more channels I would appreciate it

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

ksd6700 - Gaming Squid Missile: influences

I love wearing them on my sleeve, so this music video comes with some massive shoutouts to:

The Scene / The New Dance Show: absolutely what I was going for with the set design and the general construction of the video

Ugo Ugo Ruga (and other early CGI): big influence on Firedrill's art and character design for the vid

bullet time / virtual cinematography of the Wachowskis, John Gaeta & co

Mummenschanz

and of course the Backrooms / liminal spaces phenomenon: too many to link, but here's a recent fav which gave me some set design ideas

#music video#new song#youtube music#cgi#blender 3d#dance music#acid house#techno#detroit techno#The Scene#The New Dance Show#Mummenschanz#The Matrix#the wachowskis#john gaeta#bullet time#virtual cinematography#virtual camera#ugo ugo ruga#the backrooms#liminal#liminal reality#liminal spatial constructs#retro cgi#retro graphics#low poly#vhs aesthetic

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Are the Backrooms a broken TARDIS?

Are the Backrooms a broken TARDIS?

🪞 What Are the Backrooms?

For those unfamiliar with the mythos, the Backrooms are a human urban myth/legend that describes an endless, liminal labyrinth of fluorescent-lit, yellow-carpeted rooms that one "noclips" into by accident—that is, by falling through reality itself. Once inside, escape is rare, sanity is optional, and time seems to move… wrong.

Key features include:

Shifting architecture: rooms repeat, distort, and change dimensions.

Non-Euclidean layouts: corridors loop or stretch in an impossible manner.

Chronological instability: time appears to pass inconsistently, if at all.

Paratextual paranoia: Vaguely-described 'entities' may stalk the corridors.

🌀 So, Are They a Broken TARDIS?

Let's examine the possibilities.

📦 TARDISes and Interior Collapse

When a TARDIS is damaged, especially from temporal stress, its dimensional interior can collapse into paradox loops or misfire into recursive spatial traps. We've seen:

Corridors twisting endlessly, and rooms vanishing from memory.

A corrupted TARDIS creating an infinite prison of alternate timelines.

So yes—TARDISes are capable of housing rooms that shouldn't exist and sometimes do so maliciously.

🔧 Diagnostic Parallels

Backroom-like phenomena could be explained by:

A rogue or feral TARDIS losing control of its architectural configuration.

An Interior Perception Filter gone haywire, trapping occupants in looping cognitive constructs.

A crashed prototype (pre-Type 40) abandoned in the vortex and left to rot until reanchored to N-Space.

🚫 Counterpoints

But let's not jump to conclusions:

The Backrooms have no known control room or Eye of Harmony.

The "noclip" mechanic is anomalous even by Gallifreyan standards. TARDISes don't usually kidnap people without a psychic link or a darn good reason (though you may counterpoint this one with sheer madness).

No known signs of a symbiotic interface.

🏫So ...

Could the Backrooms be the decaying husk of a broken TARDIS? Possibly. But they could just as easily be:

A collapsed pocket dimension.

A trapped reality fragment from the Dark Times.

A thought-based prison from the 10th Dimension.

Or (most likely) a low-level spatial trauma node clinging to a forgotten corner of the Web of Time.

Either way, we don't recommend it.

Related:

💬|🛸🌌Can a TARDIS be altered for travel in the multiverse?: How you might go about getting to the multiverse in your TARDIS.

💬|📱🕸️What does the Web of Time look like?: Overview on the Web of Time and its relevance.

💬|📱👁️What’s Eye of Harmony?: What this is and how it works, and how crucial it is to Time Lords.

Hope that helped! 😃

Any orange text is educated guesswork or theoretical. More content ... →📫Got a question? | 📚Complete list of Q+A and factoids →📢Announcements |🩻Biology |🗨️Language |🕰��Throwbacks |🤓Facts → Features: ⭐Guest Posts | 🍜Chomp Chomp with Myishu →🫀Gallifreyan Anatomy and Physiology Guide (pending) →⚕️Gallifreyan Emergency Medicine Guides →📝Source list (WIP) →📜Masterpost If you're finding your happy place in this part of the internet, feel free to buy a coffee to help keep our exhausted human conscious. She works full-time in medicine and is so very tired 😴

#doctor who#gallifrey institute for learning#dr who#dw eu#gallifrey#gallifreyans#whoniverse#tardis#tardis biology#ask answered#GIL: Asks#GIL: Gallifrey/Technology#GIL: Species/TARDISes#GIL

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

author reclist: wolfpants

over the last few months, i've been devouring @wolfpants' works. ever since reading pages of you in two days, their rendering of harry, draco and a vast array of incredibly compelling side characters have irrevocably hooked me.

wolf is an author in enthralling motion. their fics often feature places, temporalities and contexts far removed from where canon holds & leaves us, while simultaneously being tenderly familiar, like coming home. wolf's sense of & grasp over setting leaves me breathless and dumbstruck. their different spatialities inform & infuse character in admirable ways, at various levels of craft, enjoyment and inspiration. this fandom knows and loves the draco and harry they give us, but we delight in discovering new dimensions & aspects of these characters. it's always done brilliantly believably, especially in the framework of the worlds they construct— a breath of fresh air in a forest where the trees still know your name.

wolf's works also demonstrate, sometimes explicitly, sometimes implicitly, a really significant political sensibility. most of their fics are set against backdrops tight with political tension bleeding into the characters' circumstances and interpersonal dynamics. whether through a spectrality haunting the narrative or the crucial central diegetic thread, wolf's works are layered, interrogating and collapsing delineations among private, public and political, between history and contemporaneity and between narrative and commentary.

in the interests of length & theme of this list, i've specifically selected some fics that, for me, showcase wolf's mastery & playfulness with setting, understood as deviations in place, time and universe. the broader recommendation is, of course, to check out everything wolf has ever written!

nightcall (E, 1k) ft. a long distance phone call

On a top secret Unspeakable misson, Harry calls Draco from a remote phone booth on the Isle of Skye.

a stunning portrait of desire, longing and familiarity that uses distance as a device to intensify every element. it's unbelievable how much character & context 1k words of (mostly) smut can pack in. the slivers of backstory demand your investment, inform the dynamic in crucial ways and set up some delicious stakes and tension. and some absolutely fantastic dirty talk. see also: @getawayfox's gorgeous art for this fic!

long haul (E, 8.6k) ft. plane rides, mile high club, nyc

The last person Harry expects to run into on a long haul flight to New York City is Draco Malfoy.

the way wolf writes movement— between places, between people— strokes its way up your spine, warms you, walks with you. draco and harry, buoyed in the air, let preconceived notions fall away, to be replaced by startlingly rapid and exquisite intimacy. the liminal settings, specifically, allow mature, open-minded, desirous characterisation & some of the most glorious, soft, tender sex to fall into like a warm bed.

look for me in the sun (M, 8.7k) ft. americana, roadtrip/on-the-run vibes

Harry and Draco are on the run in America after a mysterious string of werewolf-like attacks in the Muggle community causes the Ministry to impose new and harsh anti-werewolf legislation.

atmospheric writing dialled up to eleven, like the smell of ozone in the air before a thunderstorm. the sense of limbo— transience, out of place and time, the complication of home— that afflicts the circumstances of draco & harry here is heart-wrenching. a taut rumination on otherness in a variety of ways, rendered through some of the most tense and subtle writing i've encountered.

under giant mountains (E, 33.7k) ft. norwegian dragon reserves & rampant escapist tendencies

Harry doesn't know where he's going. Everyone else has their life paths figured out; he doesn't even know where his map is. Who'd have thought Draco Malfoy bathing in a Norwegian forest would be the guidepost Harry needed?

opens with harry, stuck in the same place for far too long, and draco, avoiding fixity like the plague. this fic looks at both stagnation and escapism as iterations of each other & treats them with the gentlest empathy. the norwegian dragon reserve setting, whose visuality wolf's writing captures beautifully, becomes the canvas to explore both. desire, here, was simultaneously so evident from the outset and took its time to build— longing tinged every interaction & payoff, in the form of a sequence of some of the most emotionally fraught sex scenes i've ever read, was that much sweeter.

romp and circumstance (E, 35k) ft. a historical au set in the 1800s, regency era england

Since the war, Harry Potter has gone from Saviour to Scoundrel—not that he’s complaining. With a schedule full of gorgeous men, alcohol, and late nights, why would he want to change? Enter Draco Malfoy: beautiful, sharp, and completely untouchable. When Draco comes to Harry with a proposition to help him attract an engagement, Harry’s up for it—after all, how hard can it be not falling for his former nemesis? Very hard, apparently.

the very first wolf fic i read, in a brief little fandom interlude back in 2022. i remember thinking, then, what an author, i'm really missing out these days. one of my favourite post-war harry characterisations— raucous, promiscuous, messy and at heart, a hopeless romantic. also one of my favourite draco characterisations— pristine, a little uptight, cool and distant and untouchable, except what he really wants is to be unbuttoned, messed up. the transforming sentiments of their relationship were so compelling, the build of harry's feelings was perfectly achey and tender and this draco was a complex, nuanced, frightfully sexy version that i just couldn't turn away from.

pages of you (E, 101k) ft. a 1980s non-magical au

Summer, 1980. Harry is floating between university and becoming a Real Certified Adult. He's not ready. He really isn't. In a desperate attempt to have the Best Last Summer ever, he takes a casual job at his godfather's bookshop in London, starts an illicit pen pal affair with a wordy posh boy that he's catching feelings for, all while dealing with the son of Sirius's business rival, one Draco Malfoy, insufferable know-it-all extraordinaire.

gosh, what a fic. sensitive and sprawling, this work brings the spatialities of london, sirius and remus' queer comfort of a bookshop and harry's room at the residence halls to pulsing, colourful, splendid life. i can still close my eyes and imagine the spaces this fic occurs in, how important they are to the push and pull, ups and downs of the dynamic between harry and draco. a coming-of-age/sexual awakening & exploration story, summer romance and queer political fiction rolled into one, this is a fic that's hard to summarise and easy to obsess over. perfect characterisations, writing that burrows into your soul and a plot that unfolds with the slow and steady depth of gentle lake.

and lastly, a fic that's on my tbr:

terrible people (E, 52.7k) ft. cruises, beach holidays and more of @getawayfox's masterpieces

What happens when Harry and Draco end up on the same Muggle gay cruise? They certainly didn't plan for it to happen (but their friends might have). They're stuck with each other for a week, they might as well make the most of it, right?

in conclusion: vivid, descriptive, immersive storytelling from an author who understands the intricacies of different narrative elements and leverages them masterfully. can't wait to read the works i haven't, and for everything wolf writes in the future!

#wolfpants#drarry rec list#geets recs#drarry fic#drarry fanfic#drarry recs#draco malfoy#harry james potter#hpdm fanfic#hpdm#draco x harry

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

final project portfolio - "dimensions of light"

Shot on Sony A6400, low light - artificial lighting

Artist Statement: In this series, I explore the liminal space between two-dimensional photography and three-dimensional perception through the manipulation of projected colored light. By capturing fragments of light cast against walls and then reassembling these images into abstract "joiners," I create works that challenge the viewer's understanding of depth and dimension. The geometric formations emerge not from physical objects but from the interplay of light, shadow, and surface—transforming flat planes into seemingly tangible spaces.

My process involves positioning colored light projections, photographing moments of these illuminations, and then reconstructing them into cohesive and abstract compositions. The resulting are simultaneously flat photographs and illusory three-dimensional spaces that invite the viewer to mentally reconstruct their spatial relationships. The vibrant colors and dark shadows dominating the works evoke feelings of depth, mystery, and introspection.

Through this exploration of constructed space through light, I seek to question our conventional understanding of photography as a medium that simply documents reality. Instead, these joiners propose that photography can actively create new realities—spaces that exist only within the frame yet feel dimensionally authentic. By working with projected light rather than physical objects, I emphasize the nature of perception itself, suggesting that our understanding of space is as much a mental construction as a physical experience. The series ultimately invites viewers to reconsider their relationship with both photographic images and the spaces they inhabit.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Writing Initiative № 06

Which piece did you present to the class today? How does it relate to the other pieces previously presented?

This week I presented the first tests I did for my 2nd alter ego (Paulina)'s installation. Now that I established who she is—a designer/writer turned "detective," investigating the limits of body and self—and from where she is (Romania), I could begin specifically curating things for her desk. This includes a Romanian dictionary, Romanian and English books, readings like Freud (Id, Ego, Superego) and Lacan (Mirror Image), and Mademoiselle G's photos from the last taxonomy in her photo series, Liminal Bodies (capturing bodies blending with/fading into the landscape, similar to the Nabokov quote: "It may be wonderful to mix with the landscape, but to do so is the end of the tender ego.")

Describe 2–3 specific strengths your classmates found in your work and their reasons for identifying them.

My peers were interested in the variety of artifacts presented and what they told about the alter ego implicitly. They also enjoyed the fact that Mlle G's photos are included, implying an interaction between these two 'people.'

Describe 1–2 specific ways your classmates thought you could improve this work going forward.

The current iterations of the installation showed a few variations of organization: more orderly (as if the desk was tidied), more messy (looks like its been used/research is in progress), and very messy (chaotic working). My peers told how they preferred the in-between stage, where it looks like the desk is in use, but its still navigable as a viewer.

Finally, you have now had a chance to present each of your projects (2D, 3D, 4D, Reflective) in process to the class. Produce an image of each one and describe how an aspect of your word is manifested in each piece.

This is not the case for me. My circumstances have created a different trajectory for my progress, and what has yet to be developed is my 4D (film) and reflect (exhibition) both are dependant on the 3D stage being resolved first. But, since the beginning of the semester, I have scaffolded how each piece manifests my word. 2D is an investigation into spatial borders, by Mademoiselle G. 3D is an investigation into corporeal borders, the borders of self, by Paulina Austeru. 4D is an investigation into the role of language in delineating borders and constructions themselves ('Mademoiselle G' and 'Paulina Austeru'), and the investigation of textual borders, textual bodies (words), by "Alexandra Maftei". The reflect is the final "circle" encompassing it all, the "curation" and rationalization of all of this work by Alexandra Caroline Maftei.

0 notes

Text

Abstract Dreaming of Construction in Cubitis, Florida

Abstract Dreaming of Construction in Cubitis, Florida

Saturday morning, 20 July 2024

The setting of my dream implies that I live in Cubitis (unseen since July 1978), though my focus is on the neighbor's house (though not who lived there at the time). Real-world recall is virtually non-existent, as is logic and even size orientation. My sense of touch is sometimes present (though not vividly), but physicality is mainly undefined. This dream is abstract to some degree, but partially active somatosensory cortex dynamics are its main foundation and causality. I indirectly seek to validate tactility and resolve the concept of spatial orientation as a precursor to coming to my senses to wake, as simple as that. This attribute in this dreaming mode is always either the tip of something, like a screw or something potentially sharp, or the teeth of a nibbling animal.

An unknown man (personified protoconsciousness as an aid to attaining consciousness) and I are working on the north side of my neighbor's house. Instead of the windows in real life, there are two external structures about the size of an air conditioner. However, despite their small size, the implication is that they are rooms for people to use.

The activity occurs in a continually resetting format as I build my perception of temporality. It is not a looping and repeating narrative, but one that is slightly different each time as my dream self takes over the role of protoconsciousness.

One could say that the two rooms with no outer walls are like sections of a sizeable dollhouse, though my dream self sees them as part of the house.

Two sizeable screws need to go through the top of each "box." However, they are not supposed to go through their ceilings. I illogically perceive each "room" as a similar kitchen. The man's attempts to finish the work are not suitable because I can feel the bottom of each screw when placing my hand into the miniature room. I think such a feature will make the room more cramped - even though the idea of living inside a small box is ridiculous. I mentally help the man until the rooms have less of the four screws pushing through the ceiling.

Recognition that they are no larger than a sizable wooden box never conflicts with my dream self's belief they are rooms of a house.

Dream content building on the nature of sleep and as a guide to attaining consciousness (through the temporary and transient state of proto-consciousness) has no real-world "interpretation." Ultimately, it does not add up that society can be so "absent" to the nature of sleeping and dreaming. Even AI is corrupt and useless because it gleans virtually countless falsehoods from dream lore. The only way it could be relevant is to have a legitimate "understanding" of how a dreaming mind seeks to achieve consciousness, not a dream as an event with real-world meaning or symbolism (sans liminality and deliberately building a dream narrative to give the dream state a different function than as a crutch to achieve wakefulness) or the popular myth of the "subconscious mind.”

Key points:

Most "dream interpretation" (in the typical sense) is pointless (other than as an exercise in creativity) because many dreams (depending on their mode) are simply a result of the mind's attempt to wake - though the patterns of which have legitimate causality (autosymbolism, not symbolism in the conventional sense). How the average person fails to grasp this does not add up and implies something unknown (perhaps something neurologically missing from many humans) has a major influence on people. (Look at the state of the world, for example.)

The "subconscious mind" does not exist. In contrast, the temporary state of protoconsciousness is active in the transition from dreaming to waking. Liminality is proof that the "subconscious" is not a definable feature. Additionally, I have only known of a few people who could communicate on a transpersonal level (which society denies exists even though the main attributes of my life’s path were built upon this dynamic - so I have a completely different kind of quantifiable and duplicatable evidence, monitored over many years - than the majority).

The process of achieving wakefulness from the state of virtual amnesia and the absence of real-world logic and cognizance is crucial. How could anyone think it "represents" real-world factors?

AI is currently ineffective in understanding dreams due to the prevalence of false information (including religious doctrines and other occult falsehoods, which AI often gleans data from rather than genuine data).

0 notes

Text

To pursue poetry, I left Cebu a number of times, set out to literary spaces, moved to Manila, moved to New York; after each time, I would return to Cebu, the province where I was born and where I grew up in, which also happens to be the Philippines’ cultural and economic center in the Visayas region. Living in one of the many islands in an archipelagic country with more than a hundred languages, there is always a distinct sense of leaving a center and of reaching another every time I travel, such that the country’s capital Manila is not only a geographically different space but also a linguistically and socially different world as New York, too, being in a country an entire hemisphere and ocean away, is another world. In these worlds that are not the world I first learned to inhabit, I was as an outsider constructed in ways such as being assumed to be a cisgender woman who is heterosexual and fluent in Cebuano, and also one who would write, perhaps with nostalgia for belongingness, about my hometown and the ethos of my Visayan peoples. [...]

For although I recognized I may be from another “world” I found that, nevertheless, I felt a sense of affinity almost akin to belongingness in these spaces and places that were different and away – perhaps, precisely because they were different and away – from the actual place of my origin conventionally perceived as my home. This is not to mean the inverse that I am not at home in Cebu is also true; rather, that my cognition of being at home in a world and my sensibility of affinities have grown expansive by the lived pluralities of my identities.

By “world” I mean something modified from how María Lugones thought of it as one that is inhabited by actual people whether it be a few, as in a fraction of a society, a particular society in itself or even larger to include several peoples within the realm of animating principles. A world, to my sense, also includes an affective dimension in relation to a kind of durational and geographical-spatial zone that “homes” such world and the individuals inhabiting this world. In this way, a world may be thought as a relational, rhizomatic center of affect. It can be created temporally such as when individuals are brought together by circumstances; when diverse writers come together in workshops, residencies, fellowships, or festivals that, although may seem momentary, could be enduring in its subsequent forms as their meeting of persons may take place not only within the experienced physicality of the moment but also, among others, at the intersections of a language, at the contiguous borders of coloniality, in an interlude of what may later be understood as a lifelong advocacy, in the liminal spaces where nuanced interconnections are made as writers draw from where they have been, where they are at, together at the moment, and where they intend to move towards dreamed futures.

It is in these encounters that I found my selves in worlds with Merlie Alunan, with writers from eastern Visayas who write in their own local languages similar but different from Cebuano, with literary communities in Cebu such as Women in Literary Arts and Bathalad, as well as writers from other regions across the country through which I “became” a writer from the South. South, where Cebu is cartographically located in relation to the capital, Manila, less a geographical marker of where I am from as it is, to my sense, an identity, a position by affiliation or affinity, a kind of belonging, and complicated alliance to bring the idea of “nation” outside its conception within the confines of the country’s capital. That this world, mostly populated by writers from or writing in the Southern regions of the Philippines, may also nuancedly expand to include the entire country and even the Global South, gesturing at the irreducible variation of worlds that allows a world to be a kind of center in itself, created and grown within the labile self who provisionally inhabits this world through nodes of self-identifications and self-determinations.

A world, then, is never stagnant; it is mutable. It is also interconnected in myriad of ways to many worlds that a self has previously traveled and inhabited, corporeally or otherwise. It may be first cognized through mediated introductions: overheard from someone; read from a book; seen on-screen; reimagined constantly into becoming real enough to be inhabited by a self.

---

All text above by: shane carreon. “Archipelagic Interiority: Notes and Reflections on Poetic Voice and Trans Writing in the Philippines.” Kohl. Volume 9 Number 1. Special Issue: Anticolonial Feminist Imaginaries. Winter 2023. [Some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism purposes.]

#ecology#abolition#archipelagic#ecologies#geographic imaginaries#multispecies#tidalectics#archipelagic thinking#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies#gender and the sea#cebu poetry

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi <3 because you have written a lot about angel stuff what do you think about the depiction of heaven facilities in Supernatural, like it should have been like backrooms, like liminal spaces

HIII sorry first of all I’m going to be an annoying pedant about the term “liminal” because it’s an important geographic term. Like from a utility standpoint liminal spaces either facilitate human movement (roads, hallways) or are holding bays while waiting for movement to occur (hospital waiting rooms, airports). Their function is their lack of meaning aside from being a space that connects you to a place of meaning. I think that’s why on an emotional level people often express feeling strange in these spaces, whether it’s via memes about encountering demons in the hallway at 2am or feeling like an unplugged refrigerator in an airport waiting area. You feel “out of place” because the space is designed to be temporary. You don’t go to a sidewalk or road to hang out with your friends, for example!

So like Heaven as a space where angels hang out doesn’t fit that definition very well. We see them using it as a meeting place to talk with another, to observe humans in heaven, to receive punishment after disobeying, and all kinds of other things. It’s a place that has meaning for them that they use for a variety of different things, and it’s also a place they defend as their “home.” I don’t like most depictions of it in the show, but that takes a while to explain beyond the obvious of “it’s kinda lame”

The interesting thing about spn is that it takes the biblical* creation myth seriously while also acknowledging modern understandings of the creation of the universe (the Big Bang is referenced, Cas says he’s on Earth “several billion years after the beginning” that kinda thing), so Supernatural’s sense of temporal and spatial scale is much more vast than the religious history it’s drawing from. As a result angels seem to be a mix of traditional depictions of angels (wings, fire, glowing eyes, swords) and modern knowledge bases (Cas knows physics and calculus, there’s multiple references to them being machines/computers, he describes his true form in reference to modern architecture, “wavelength of celestial intent”, etc).

So like in light of that, I often think of Heaven not as like a three dimensional realm angels go to when they want to gossip with each other (which is how it’s presented in the show) but again as a blend of historical religious myth and modern science. The Halo games actually do this very well - the gods in those games constructed much of the laws of the universe that every living thing operates from, including upper dimensional channels for travelling vast distances. The gods themselves exist kinda like networks that transmit information across spacetime and don’t really exist in 3 dimensional form - think of a brain with much more complex architecture that spans the universe. Like in the same way a shadow is a 2D representation of a 3D object, their 5D “star roads” (transit channels) can sometimes be glimpsed in 3D “shadows” (this is a broad over simplification and I’m pulling from a rusty memory on Halo lore, so some of this is probably inaccurate). Dimensionality is reduced until the human brain can perceive it, and human beings can’t parse data in more than 3 visual dimensions. We can do 4d as long as the forth dimension is temporal (not visual), but even that is pretty difficult. But think of all the data loss in a shadow! How much do you know about an object if you just look at its shadow?

And like given how bizarre angels are, how rare they were prior to their introduction in s4, and how the early seasons especially play with the cosmic horror element of them having to exist on earth, I think it’s maybe not a huge stretch to conceive of them as these vast informational networks and not like discrete bodies that are separate from each other. The Host is the amalgam of all angels, and angels are established in the show to be vehicles for God’s will who carry out orders without question. They are also, again, established to have advanced modern knowledge of things like math and string theory and natural selection. spn is actually a really good study in the naturalisation of religion into state authority, infusing the natural sciences (which are regulated and controlled by government bodies like the academy and scientific agencies) with religious importance, and naturalising religious figures such as angels by positioning them as authorities on science.

Anyway sorry lol this is all over the place. The point I’m trying to make is that, while this is not supported in canon explicitly, I think there’s a decent argument to be made that angels defy descriptions of “existing in a place.” We know their grace and their true bodies are separate things, we know from S8 that Cas can exist simultaneously in both Heaven and on Earth at the same time, and we know angels have the ability to monitor earth (and other places in spacetime) without interacting with it directly. I tend to therefore think of angels and Heaven as these not-spaces, and more like a cluster of information that gathers to exchange knowledge. Heaven is the medium through which that happens, and then angels converse with one another through that medium. They don’t necessarily have to “travel” there because their true forms exist discontiguously from their consciousness, so presumably angels don’t have to physically move their bodies to places in order to interact with other angels. So Heaven also doesn’t have to be strictly physical.

This is where I think spn suffers from its own visual medium. The written word is a lot more effective at communicating incomprehensibility (HDM’s version of angels described them as vast celestial architecture, and you can see giant impossible walls hanging out of their bodies when you look at them from your periphery), and I think that’s also why early seasons Heaven and Hell were a lot more intriguing because they were visually absent from the show. AND, also, the one time we did see Hell in the early season (the shot of Dean waking up in Hell in the s3 finale), it was depicted as an interlocking network of chains, which fucking owns and is partially the inspiration for conceptualising Heaven in a similar way.

—

*using the word biblical as a result of my own limitation of knowledge. I know a lot of the lead writers are Jewish and I don’t mean to downplay that. I also know spn exists in a bizarre intersection of being kinda Catholic and kinda Jewish so I don’t know what the exact appropriate term for this would be.

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (Lumière, 1895)

In 1895, inspired by the current topic du jour; which was to further investigate the stroboscopic principles explored with the zoetrope, and other contemporaneous devices that exploited our human persistence of vision, Auguste and Louis Lumière, in a Promethean move, invented the cinematograph. One of the earliest, and perhaps most profound experiments helmed by Lumière was Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (Lumière, 1895), which can now be asynchronously viewed as a singular, predominantly uncorrupted cinematic representation of actuality; a documentary - the workers operate on the virtue of their own agency as they scurry to enjoy their short reprieve before the travails of the following working day - absent is the accosting, performative behaviour one may observe if it were filmed in the 21st century, as for all intents and purposes, the workers, to be prosaic, are not yet acquainted with the role of the cinema and how time, framing, and thus reality can be manipulated. Whilst in its infancy, it must be noted that photography, an antecedent of the cinema, did very much exist, so it would be dismissive to assume that the very concept of surveillance is absent from the workers comprehension - that being said, however, due to this particular document existing in such an embryonic stage of the very notion of optic surveillance, we are presented with what is a platonic ideal of actuality in flux. In spite of this, however, if we were to view these experiments as pure exemplar representations without perversion, it would only be of service to the vitiation of the autonomy of the filmmaker; Lumiere articulated his gaze by setting up the camera in a specific spatial geometry that would adhere to his idealistic vision of how reality should be represented - that is to say nothing of course of his command of when time itself should begin and end. Autonomy is granted to the workers, as they embody a mercurial urge to escape the factory, they do not, however, escape the documentary gaze -

“For the real does not wait, and notably not for the subject, since it waits on nothing from language. But it is there, identical with its existence, noise in which everything can be heard, and ready to burst over what the "reality principle" there constructs under the name of the external world.” (Lacan, 1976-77)

- subjects are freed from the bonds of time, but they are not liberated from eternity, instead, they are interned within the liminal confines of a bell jar; the subjects are rendered a mere Sisyphean gesture of recurring labour.

This proposition serves as the foundation for all forms of cinema; the idea that we are simply unable to capture what is real, and in lieu of this, we must embrace the cinema as an ekphrasis; to capture the spirit of actuality, and not its surface. This understanding of the cinema is perhaps why documentary aesthetics that blur the lines between fiction and reality (vérité) are so prevalent in popular narrative cinema; as documentary ultimately failed its inveterate conquest to be a pure representation, and leaned into the form’s more superfluous tendencies over the years. It would be unscholarly, however, to suggest this is documentary's congenital birthright to be pure; as all art is inherently a corrupted abstraction of phenomena due to the intrinsic human intervention involved in the very practice of the craft (in this case, filmmaking).

To define documentary one must simply look to define cinema itself, as both fiction and that what we conceive of non-fiction runs parallel, and thus intertwines just as our cultural understanding of perceived knowledge is similarly corrupted over time. As a prudent illustration of this fact, one can simply look to Frank Capra’s Why We Fight anti-war series (1942-1945), and his liberal re-appropriation of footage originally captured as pro-Nazi iconography from Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda film Triumph of the Will (1935). This remains testament to the fact that human history itself, by all accounts, is interwoven and unspooled with an inscrutable amalgam of fantasy and actuality, and thus it is obstinately mirrored in our cultural artefacts - they uncompromisingly articulate the ghosts of our lives, and so documentary must in term represent the spirit, and not the surface - for this is an inherently fruitless crusade.

#Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (Lumière#1895)#1895#louis lumiere#auguste lumiere#lumiere bros#lumiere brothers#define documentary#documentary#cinema#silent#film#movie

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

liminality and spatial constructs, re-enforcing dystopic experiments for work, after work from home #dystopia #madrid #lookup #cityscape #blue #liminalspace #architecture https://www.instagram.com/p/CRhB3yboprB/?utm_medium=tumblr

1 note

·

View note

Text

ESSAY: Kali - Polysemantic Goddess

...Kali is, at her core, the embodiment of opposites. Through her, Hinduism has syncretized a variety of extremes: destruction and creation, death and rebirth, mother-love and sovereign sexuality, primordial violence and self-sacrificial wisdom.

Among the multifaceted pantheon of Hindu deities, the goddess Kali occupies perhaps the most fascinating yet frustratingly misunderstood position. Her iconography – filtered through the lens of parochial presuppositions – often distorts her persona into that of an ogress: bloodthirsty and warlike, with a penchant for destruction. However, this prescribed identity disregards the rich nuances of Kali's origins, reducing her instead to a chimera that arguably embodies the submerged fears of the archetypal, independent feminine. Too often, in text and media, she has been either devalued or demonized, consigned to the same spectrum of mythological would-be villainesses as Lilith, Hecate or Morrigan. New Age depictions of Kali are equally suspect for flattening her into a mere tool for social discourse. Neo-paganists and Western Kali enthusiasts have been accused of appropriating the goddess as a one-dimensional figurehead for Mother Earth, or as a self-serving expression of radical female sexuality, without taking into account her deeper symbolism within Hindu philosophy.

Modern cross-fertilization between the two cultures, thankfully, has allowed academics to defuse these seemingly irreconcilable caricatures. Today, a wealth of literature is devoted to understanding Kali's complex character and role. By navigating the maze between misconception and truth, what emerges is the realization that Kali is, at her core, the embodiment of opposites. Through her, Hinduism has syncretized a variety of extremes: destruction and creation, death and rebirth, mother-love and sovereign sexuality, primordial violence and self-sacrificial wisdom. Kali's incarnations, whether tranquil (saumya) or fearsome (rudra) are simply manifestations of omnipotent cosmic energy (sakti) which is the fuel within and behind every phenomenon of the manifested world. Kali, in short, is the fulcrum around which the cosmos revolves, and she wields her power in both transformative and terrifying ways.

Perhaps most remarkable is that, in Hinduism, Kali is affectionately referred to as Maa, or Mother. This title of respect, with its intimate subtext, is important not because her devotees attempt to distinguish between the maternal Kali and the sanguinary Kali, but because in Hinduism, destruction and creation are regarded as complementary, rather than diametrical, facets of a single continuum (Kinsley 15). With each rebirth, human beings are free of the negative traits conducive to social and personal downfall: cruelty, greed, egotism, self-interest etc. This blank slate goes hand-in-hand with the opportunity to do good karma. Each birth is a new beginning, a fresh start to awaken one's potential for self-transformation. Death, therefore, is not a stillborn story, but one that begins, instead of ending, with the power to sidestep adharma and tread fully across the true dharma path. To accomplish this, Kali is instrumental. She is the Divine Mother who frees her children from the limitations of the physical realm – in this case the cyclical tedium of samsara. Infinitely patient and benevolent, she nurtures the souls (atman) of human beings until they have perfected their understanding of the Ultimate Reality (Brahman) and achieved liberation (moksha). Her color, the pure black of nothingness, can be viewed as the primordial womb within which the enlightened souls merge (Frawley 133).

Of course, to fully appreciate Kali's extraordinary complexity, it is necessary to delve into her etymology and history. In his book, Devī-māhātmya: The Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition, Thomas B. Coburn remarks that while Kali is simply a feminine play on the adjective Kaalam, or "darkness," the latter can also be linked to the derivative noun Kaala, or time. Kali, then, is meant to symbolize "that which brings all things to an end, the destroyer" (108). Kali's mythology and the beginnings of her worship are difficult to trace. However, the earliest known mention of Kali is observed in the Mundaka Upanishad, where she is the name of one of the seven terrible black tongues of the fire-god, Agni. In the Mahabharata, she makes a token appearance as one of the "mothers" who become companions of Karttikeya as he boldly ventures forth to slay the demon Taraka. But it is not until the Markandeya Purana, within the chapter Devi Mahatmya ("Glorification of the Goddess") that she makes her awe-inspiring debut. Here, Kali is depicted as both the purest manifestation of divine wrath, but also as the delivering heroine who is summoned to salvage a disaster that threatens to tear apart the fabric of the cosmos itself. Her mission is to destroy the demon-lord Rakhtabeeja (blood-seed) who possesses the power to generate clones of himself with every drop of his blood spilled to the ground. In the book, Kali: The Feminine Force, Ajit Mookerjee describes how Kali:

...manifested herself for the annihilation of demonic male power in order to restore peace and equilibrium. For a long time brutal 'asuric' (demonic) forces had been dominating and oppressing the world. Even the powerful gods were helpless and suffered defeat at their hands. They fled pell-mell in utter humiliation, a state hardly fit for the divine. Finally they prayed in desperation to the Daughter of the Himalayas to save gods and men alike. The gods sent forth their energies as streams of fire, and from these energies emerged the Great Goddess Durga. In the great battle to destroy the most arrogant and truculent man-beasts, the goddess Kali sprang forth from the brow of Durga to join in the fierce fighting. As the 'forceful' aspect of Durga, Kali has been dubbed 'horrific' or 'terrible' in masculine-biased commentaries, without understanding of the episode's inner meaning (21-55).

It is certainly true that Kali contradicts the ideological construct of the feminine as subordinate to the masculine. However, while Hindu philosophy binarizes its deities into symbols of male and female energy, it should be noted that there is an implicit androgyny within each depiction. Collectively, the Hindu pantheon represent the various spatial aspects of Brahman. Each god is an alternate component to a singular theistic unity. Gender is not always integral to this classification, although one can argue that within the social framework of Hinduism, which is heavily male-dominated, it carries significant weight. But that is, perhaps, what makes Kali all the more fascinating. Here is a goddess whose depictions are unabashedly female, yet who embodies the integral Hindu tenets of power and nature (sakti/prakriti), while simultaneously defying orthodox constraints of traditional Indian womanhood. In the book, Hindu Goddesses: Beliefs and Practices, Lynn Foulston and Stuart Abbott remark that, by transgressing the limitations of conventional Hindu womanhood, Kali represents the "transcendence of social and worldly values and the freedom this brings... As one of the Mahavidyas (i.e. one of the ten aspects of the Goddess Shakti), Kali can be understood as a liminal symbol, both occupying and traversing the very boundaries of social purity and order, danger and pollution" (118).

The diverse Puranic oeuvre only heightens Kali's uniqueness. Mother, lover, warrior, martyr – her story runs the whole gamut of human experiences. In popular folklore, for example, Kali slays the demonic Daruka and consumes his blood. However, she becomes dangerously intoxicated by the evil flowing through her veins, driven into a rampaging bloodlust. Like an embodied natural disaster, she sweeps across the earth, spreading catastrophe in her wake. Implicit in this tale is the theme of self-sacrifice. While the ferocious Kali is born to vanquish evil, it is clearly at the cost of herself (157).

Other versions present a more empowering outlook. In the book, Questions on Hinduism, John Renard recounts how, in a desperate attempt to cool Kali's wrath, her consort, Shiva, throws himself beneath her feet. This act establishes him as her more passive counterpart, playing on the pun Shava (corpse). More to the point, Kali's story clearly "identifies the female as the energy, the divine spark at the heart of reality, which confers on creation the power of transcendence" (124). Indeed, in traditional as well as contemporary artwork, Kali is often depicted as dancing upon Shiva's supine form. In these portrayals, titled the Dakshinkali, she embodies the unstoppable dance of Nature, while her mate, Shiva, becomes the manifestation of Consciousness. Rather than an active force, Consciousness plays a silent witness to the dynamism of Nature. Shiva, sprawled pale and corpselike beneath Kali's foot, illustrates how all that Consciousness perceives is the force of Nature (Pattanaik 53-67).

In other versions, Shiva does not throw himself beneath Kali's feet, but transforms into a bawling baby. When Kali hears the cries, her fury is subsumed beneath a flood of maternal instinct. Gathering the baby to her breast, she nurses him; her violent potential is thus sublimated into motherly largesse. While this retelling can be criticized as a patriarchal misappropriation – a blatant attempt to tame seemingly-destructive female independence through motherhood – it can also enjoy a kaleidoscope of interpretations. In contemporary Western feminism, it is perhaps not always fashionable to exalt motherhood, which so often conflicts with female self-expression and autonomy. However, the fact that Kali, whose persona is so fearsome, is woken emotionally by a child, and is able to discover opposite yet apposite aspects of her own fiercely protective nature, holds a life-affirming sweetness (Mohanty 55-70).

Other narratives completely dispel the notion that even the all-powerful Kali is inherently submissive to the male form of the divine. In the Tantric version of the Kali's battle, Shiva assumes the guise of a beautiful man and lays himself across Kali's path. Here, as in other adaptations, Kali ceases her rampage after stumbling across Shiva's chest. However, in this case, it is because she is consumed with lust. Flouting the conventions of decency, she straddles Shiva out in the open and begins to make love to him. For many, this combustible blend of violence and sexuality is an empowering motif with a potentially subversive edge. For others, however, it comes as no great shock that Kali, as the purest and most dynamic representation of sakti, is equally unapologetic of her desires (75).

Indeed, Tantric depictions of Kali engaged in coitus with Shiva, which shocked early British settlers as prurient, in fact held intensely ritualistic and symbolic underpinnings. According to Tantric doctrines, the human body symbolizes the microcosm of the universe. As such, Kali's union with Shiva is neither sinful nor shameful, but integral to the process of creation. In the book, Encountering Kali: in the Margins, at the Center, in the West, Rachel Fell McDermott et al. analyze this particular myth, faithfully recreated in ancient and contemporary artwork: "Siva is the inert soul, purusa, whereas Kali is the active, creative prakriti.... Tantra emphasizes the 'erotic' (that is, the simultaneously sexual and religious) symbolism of the image. In defiance of conventional sexual mores, Kali engages intercourse with Siva in the 'reverse position' ....since siva depends on sakti for the ability to orchestrate creation, preservation, destruction" (53-55).

Equating this unadulterated female power with the negative – a proclivity often seen in patriarchal interpretations – would be fallacious here. So too would be the tendency to pedestalize the divine, to fit female deities into tidy, distinct boxes of "maidenly" or "motherly." Kali's very mythology allows these generalizations more breathing space. Her destroyer/creator/mother/warrior/temptress/martyr mystique encompasses every facet of existence, from the beautiful to the horrifying. At the most fundamental level, her mythos serves to provoke a reaction – primeval, visceral – from observers and devotees alike. Rather than reducing her extremes to intellectual abstractions, her stories allow her to feel close and human. One might even argue that Kali's presence extends beyond liturgy and theology. Hers is a tactile and emotional experience; she exists equally in the frailties of human life and in the inevitability of death, in the fierce desire to nurture but also to defend, and in the human capacity for infinite, unceasing transformation.

Iconography, of course, serves to highlight her polysemantic and multifunctional role. Every aspect of her appearance carries a potent philosophical epithet. She is often depicted as a ferocious four-armed woman with either pitch black or dark blue skin, a mane of matted hair, three blazing-red eyes, sharp white teeth and a lolling red tongue. She is typically nude, festooned only in a necklace of skulls and a girdle of severed limbs. In two of her four arms, she wields a scythe (kharag) and a severed male head; the remaining two arms are positioned in hasta mudras that communicate the seemingly-ironic message 'Do not fear.' Despite this frightening visage, she is sacrosanct for well-grounded reasons. Her dark skin is tied to earth and space; to the fertile soil of the physical realm and the infinite darkness of the primordial cosmos. Much like black represents the all-encompassing quality of darkness, so too is Kali's darkness the signifier of her benevolent and accepting nature (Harding 38-52).

Equally powerful is the message behind Kali's nudity. She is described as garbed in space, or sky-clad, and this "absence of clothes denotes the absence of illusion" (Mascetti 47). In that sense, she is Nature at its most sublime, transcending the boundaries of name and form. As the Universal Truth, she has conquered the illusory trappings of maya. Through her, devotees can transform blind consciousness into perception, just as a wash of intense light illuminates dark corners, dissipating the shadows of ignorance. Her unbound hair, too, is charged with symbolic and cosmological significance. In the book, Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahāvidyās, David R. Kinsley suggests that Kali's disheveled mane of hair, such a jarring contrast to the way traditional Hindu women plait their hair in deference to social order, is indicative of Kali's unbridled independence. "Kali is free from convention, wild and uncontrolled in nature, and not bound to and limited by a male consort." In the same vein, Kali's loose curtain of hair is interpreted as the swathe of Space-Time, with its tangled mass suggesting the dissolution of cosmic balance. "Her hair has come apart and flies about every which way... all has returned to chaos. The 'braidedness' of social and cosmic order comes to an end in Kali's wild, unbound, flowing hair" (83-85).

Similar dualistic interpretations are found concerning Kali's tongue – blood-smeared and protruding. According to Puranic lore, Kali's lolling tongue allows her to slurp up the blood of Rakhtabeeja, before it can drip to the ground and spawn clones. In other narratives, Kali's outstretched tongue takes on broader, more psychological connotations. In The Book of Kali, Seema Mohanty states that, "With the outstretched tongue, Kali teases and mocks her devotees. She sees through their social façade and knows the dark desires they try so hard to deny or suppress. She provokes them to delve into their subconscious and confront all those memories and thoughts that they shy away from" (10).

For the colonial West, of course, this aspect of Kali's iconography seemed to fuse sexuality with brutality, social perversion with graphic violence. In the book, Encountering Kali: in the Margins, at the Center, in the West, McDermott et al. remark that Kali's tongue, filtered through the Western lens, became a blatantly phallic symbol, her persona little more than a terrifying figurehead of idolatrous depravity. Indeed, McDermott argues that for the colonial imagination, Kali was the embodiment of India itself, "imbued with debauchery, violence and death. Objectified under the 'colonial gaze'... Kali has always been an ambivalent source of mixed horror and fascination, of simultaneous revulsion and lurid attraction" (170-178). Unfortunately, such depictions, rooted in Eurocentric ambivalence, fail to appreciate Kali's full complexity. As a goddess, Kali explores and symbolizes all the uses and expressions of submerged human desire. It should be noted that in this instance, desire does not refer simply to biological imperatives with their natural rhythms of arousal and satiation. Nor is it linked purely to the erotic desire that is cloaked in visual and textual symbolism. This is desire at the cosmic, primordial level, beyond limits and civility. Taken in that sense, Kali's tongue "denotes the act of tasting or enjoying what society regards as forbidden, foul, or polluted... an indiscriminate enjoyment of all the world's 'flavors.' What we experience as ... polluted ... is grounded in limited human (or cultural) consciousness ... Kali invites her devotees to taste the world in its most disgusting and forbidden manifestations in order to detect its underlying unity or sacrality, which is the Great Goddess herself" (Kinsey 81-83).

Kali's ornaments and weaponry, too, carry a reservoir of allegorical and mystic nuance. Her garland of severed heads represent the fifty letters of the Sanskrit alphabet. These seedlings (beej) of sound – particularly the eternal syllable, Om – are the source of all creation. Adorned in the essence of reality, Kali is therefore the repository of eternal knowledge. She "decapitates words so that the seeker of truth is liberated from the limitations imposed by language" (Mohanty 13). Similarly, her girdle of severed limbs represents karmic annihilation. Each arm symbolizes the binding effect of deeds – karma – that Kali effortlessly chops down. Thus, she is instrumental in liberating her devotees from the cruel cyclicity of samsara, allowing them to achieve the ultimate spiritual realization (14).

Completing her otherworldly allure, the conjunction of femininity, monstrosity and strength, are Kali's four arms. According Bob Kindler's book, Twenty-Four Aspects of Mother Kali, her arms symbolize the cosmic circle of creation and destruction. The upper and lower right hands confer gracious and protective boons, the hands positioned in the Abhaya and Varada mudra respectively. The former is "a mystic gesture indicating the Divine Mother's serious warning to negative forces that attempt to harm Her precious spiritual children." The latter, meanwhile, signifies "gifts to those who approach Her for refuge" (22). Her left arms, brandishing the bloodied scythe and the severed head, symbolize Kali's power to eradicate ignorance. The head represents false consciousness, or the ego; the scythe is the weapon of knowledge. Thus, by slicing through the obstacles of ignorance, Kali frees her devotees from temporal bindings. Finally, her three eyes speak of her omniscience: they represent the sun, moon, and fire, which she uses as mediums to unlock the three facets of time – past, present and future (Kinsley 86-90). In ancient Greece, the ouroboros – a primeval serpent devouring its own tail – served to symbolize the coincidence of opposites, the infinite oscillation between destruction and creation, death and rebirth. In the same manner, Kali perfectly embodies the circular transience of being, the pivot upon which cosmic equilibrium rests.

Both legends and iconography reiterate her gift for transcending the broad spectrum of dichotomies because it is relevant. At her core, Kali's myth defies humanity's efforts to classify and control the unknown as a way of asserting its standing as a rational, privileged species. She corrects us of the dangerous misconception that human beings are a dominant outside force, rather than fragile stitches within the cosmic fabric itself. By understanding Kali, it is therefore possible to spark a genuine relationship with Nature in its manifold forms, and beyond them, with the all-pervasive life-force – sakti – that flows through the universe in its entirety. Renowned mythologist Joseph Campbell, in his classic work The Hero with a Thousand Faces, states it best:

The goddess is the fire of life; the earth, the solar system, the galaxies of far-extending space, all swell within her womb. For she is the world creatrix, ever mother, ever virgin. She encompasses the encompassing, nourishes the nourishing, and is the life of everything that lives. She is also the death of everything that dies. The whole round of existence is accomplished within her sway, from birth, through adolescence, maturity, and senescence, to the grave. She is the womb and the tomb: the sow that eats her farrow. Thus she unites the "good" and the "bad," exhibiting the two modes of the remembered mother, not as personal only, but as universal (95).

For the curious academic or the passionate devotee, there is no doubting Kali's appeal. But her paradoxical nature is the true crux of her uniqueness: at once a singularity and a multiplicity, she is immeasurable. Conceptually, Kali's presence is not just a part of the cosmos, but the same size as it. On one level, she is an abstract force that flows beyond the nacreous spectrum of time and space. On another level, she is a tangible, living presence swimming through the undercurrents of the real world we inhabit every day. Her voice may not always be audible to us, but the occasions when we do hear it are full of intimacy and truth.

Works Cited

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1973. 95. Print.

Coburn, Thomas B. Devī-māhātmya: The Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1984. 11-112. Print.

Foulston, Lynn, and Stuart Abbott. Hindu Goddesses: Beliefs and Practices. Brighton: Sussex Academic, 2009. 110-160. Print.

Frawley, David. Inner Tantric Yoga: Working with the Universal Shakti: Secrets of Mantras, Deities and Meditation. Twin Lakes, WI: Lotus, 2008. 130-136. Print.

Harding, Elizabeth U. Kali the Black Goddess of Dakshineswar. Newburyport: Nicolas-Hays, 1993. 38-52. Print.

Kindler, Bob. Twenty-four Aspects of Mother Kali. Portland, OR: SRV Oregon, 1996. 22. Print.

Kinsley, David R. Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahāvidyās. Berkeley: U of California, 1997. 29-90. Print.

Mascetti, Manuela Dunn., Jennifer Woolger, and Roger Woolger. Goddesses: Mythology and Symbols of the Goddess. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1998. 47. Print.

McDermott, Rachel Fell., and Jeffrey J. Kripal. Encountering Kali: in the Margins, at the Center, in the West. Berkeley: U of California, 2003. 21-152. Print.

Mookerjee, Ajit. Kali: The Feminine Force. New York: Destiny, 1988. 21-55. Print.

Mohanty, Seema. The Book of Kali. New Delhi: Penguin India, 2004. 6-100. Print.

Pattanaik, Devdutt. 7 Secrets of the Goddess. Chennai: Wastland, 2014. 53-67. Print.

Renard, John. Questions on Hinduism. Mumbai: Better Yourself, 1999. 124. Print.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Structures of Isolation

Liminal - The Albanian Landscape Journey Through a Still Image is a research project with a photograph exhibition by Saimir Kristo and Sonia Jojic. The project travel between architecture and photography in order of active exploration of the landscape and possible relationships between inhabitants and bunkers in particular contexts and locations around Albania.

In Albania are approximately 170.000 documented bunkers, which are symbols of war and isolation. With a different spatial typologies, geographical position and structural features, bunkers were structured as singular fire units but also as elaborated ensembles of three or more, up to tunnels constructed inside hills and mountains.

Numerous typologies were created also by different locations, from seaside to valleys and mountains. The strategies of positioning were defined by borders with Montenegro, Kosovo, Greece, Northern Macedonia, Adriatic Sea and Italy.

Albania was isolated for almost half a century, so people stayed in country’s heavily guarded geography without any travel opportunities. Not even a possibility to escape from a village or a city were they were born. A sad reality of a country as a living prison.

---

Liminal - A Journey Through the Albanian landscape Research project and photographic exhibition by Saimir Kristo and Sonja Jojic, Polis University Tirana Presented at Off Gallery, Graz

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Traces

Anio

.

‘‘ML: You do something with architectural means that makes an obsolete reality present again.

PZ: I think it is more about creating a feeling for the things that are absent than about creating a feeling of presence for things lost. So I try to create a feeling for things that are no longer here or for the lost context of things that are still here.’’

Peter Zumthor and Mari Lending - A Feeling of History

Allmannajuvet Zinc Mine Museum in Sauda - Peter Zumthor

As a child I rarely took the tube. But when I did, I found it a hostile environment; the artificial light, or better said the lack of natural light, the unrealistic fear of falling on the train tracks, the lack of anything to do while waiting. As I grew up I had to start taking the metro in Bucharest. I remember going to drawing lessons from school, and in winter, when I was coming back, it was right at that time of day when the light is dimming. 5 minute wait, 12 minute ride, 4 stations, and when I’m out its pitch dark. I find it the closest mean of transport to teleportation.

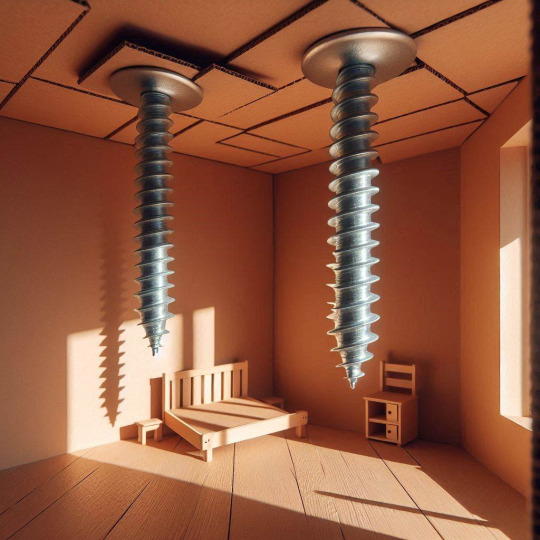

Imagine yourself in a city where you’ve never been before in an underground station. Remove from your mental image the station sign, the clock (including the line monitor) and the posters. Now you find yourself in any station of that city, at any time of the day, at any time of the year, in any year since the station was build; it’s a feeling of atemporality and a-spatiality. Most underground stations are quite sterile spaces, they are utility constructions that are guided by the laws of efficiency. The materials used are durable and don’t show signs of weathering - glazed tiles, metal or plastic seats, rubbery paint; they are materials that don’t absorb any memories, except of their initial moment(from station to station they vary slightly in fashion according to the time they were built).

Berlin underground stations closely respects this morphology (I will be referring as underground stations to both U-Bahn and S-Bahn stations that are in the underground). Built at the beginning of the 20th century, with a rapid growth up until the Second World War, and further, after the separation of the city, Berlin underground system(and overground) was and is an ever changing fingerprint of the city. From the lines’ web to the specific sign and lettering it is a system, or better said the circulation of the city’s body particular for Berlin and only for Berlin. Even though it respects the guidelines on which a metro is built, it can only tell the story of Berlin. One distinctive aspect to be noted about German underground stations is that you don’t have any form of physical barriers when accessing the platform; in this way I would argue that the stations become extensions of the streets and the ‘no questions asked’ public space. It acts primarily as part of the transport scheme, but auxiliary it undertakes non-direct characteristics of shelters, meeting spaces and shortcuts in the urban scape.

As a downfall, Berlin underground stations develop as more than shady places. For instance, the film ‘Christiane F. - Wir kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo’ - 1981 (Christiane F. - Us children from Bahnhof Zoo) focuses on a group of West Berlin teenagers who get addicted to heroin. They’re place of hangout is an U-Bahn station around which are depicted scenes of drug dealing, violence and prostitution. Another example, is set in East Berlin in the film ‘Coming out’ focused on the LGBT community in an oppressive regime(the film first airs publicly the night Berlin wall fell). One of the scenes shows a man being beaten up by a group of people in a tube station for looking distinctive.

From ‘Christiane F. - Wir kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo’

From a historic point of view, Berlin underground bears marks and tears, nowadays mostly concealed or erased, of the city’s life. In WW2 part of the tube stations served as air-raid shelters and housed military wounded in trains on underground sidings. In the final Battle of Berlin, on 2 May 1945, the Nord-Süd-Bahn tunnel (a major service line) gets flooded, leaving behind an unknown number of casualties, making it paradoxically a safe space and a death trap.

The night commencing the 13th of August 1961, underground passengers were the first to experience the division of the city. The late-night trains started stopping at the boundary between sectors, travellers were brought to the side they belonged to, and outside there was the wall. In the following years to come, the whole metro system got separated, cut in two, being another form of disruption. Bearing this in mind, it had its blind spots, small inaccuracies given by the complexity of the rail system, both physical and political.

Certain lines(U6, U8 and S2), primarily in the West were still running under sections of Eastern ground. This services were not interrupted, but it was decided to continue working without stopping in Eastern stations. They become ‘ghost stations’; on western maps they are crossed out, while on eastern maps they disappear all together, access being sealed and guards permanently surveying them from newly built concrete booths. In 1989, shortly after Berlin wall fell, Max Gold films one of the ghost stations(Potsdamer Platz). In the video you can see the station, in a form of weathering and decay through lack of use, but at the same time it is frozen in time in 1961. There are not many differences to any other station in Berlin, besides the old posters and the guard booth, but it is covered in thick dust and tiles are falling off the wall. In 1992, Potsdamer Platz S-Bahn station is the last ghost station to reopen, after the restoration of the Nord-Süd-Bahn tunnel. The station looks awfully a lot as it looks in the 1989 footage, even the white tiles covering the concrete columns are kept the same, making it almost impossible to distinguish if you’re in 1961 or 1992 or 2019.

Potzdamer Platz S-Bahn Station in 1989

U-Bahn map West Berlin

S-Bahn and U-Bahn map East Berlin

I’ve set as a direction for ‘Traces’ the insertion or change of an element in the Potsdamer Platz S-Bahn station that gives it a sense of temporality and spatial distinction, while alluding to its memory, without reconstructing it in any forward manner. By decomposing the station into component parts I focused on identifying the bit that interacts with the largest amount of people, that realistically, is touched, directly or indirectly, by anybody who passes through the space; and that would be the pavement/flooring. What I would find as being the three pieces characteristic for a metro station flooring are the general waiting area, the delimitation strip (for example the yellow line in London) and the space between the delimitation line and the track lines, where you are not allowed to step if the train isn’t in the station. This structure triggered my interest, as it creates a visual and tactile language that communicates to you through changes in colour and texture.

Materiality, Form and Sizing

After watching Adrian Forty’s lecture on his book ‘Concrete and culture’ I have reinforced my idea of concrete as a suited material for my endeavour. He argues for the multiple dualities of concrete; natural-artificial, historic-unhistoric, universal-local, memory-amnesia etc. Moreover, I took as inspiration Rachel Whiteread’s approach on concrete as a material that can embed the memory of an object, while creating an identity of its own. Through experiments, I have tested how different compositions of concrete get set or altered by the use of textiles. The indentations are generally made by using my fingertips not only to show how concrete can be easily manipulated, emphasising the antithesis between solidity and fragility, but also to give a scale for the striations that are meant to be felt while not being dangerous(if you’re not wearing stilettos). The patterns create shadows that give relief to the station, moving it away from a 2D register of materials.

The pavement is able to store information such as the weather outside, or the time of year, while being quite durable and easy to maintain. It might resemble to the eye the side of a river where there used to be water, suggesting the tunnel’s flooding (Potsdamer Platz was and is part of the Nord-Süd-Bahn tunnel). The liminal bit is rougher making a visual statement of danger and brittleness, while the demarcation strip is set in wood and stuck in using mortar, talking about an old ‘doorstep’, that was hard to place, but effortlessly removed. The model is 40cm x 64cm so it can be tested. The liminal bit and the strip will rarely be stepped on as they have a width of 24cm while an average step from heel to heel is 76cm, leaving an untouched space.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historia multidisciplinaria de la liminalidad

Referencia APA: Lim, J.P. & Ng, V. (2018). Tracing liminality: A multidisciplinary spatial construct. Journal of Engineering, 6(1), 76-90. Recuperado de: http://jea-net.com/vol-6-no-1-june-2018-abstract-8-jea

Citas e ideas:

liminalidad: simplemente, el intermedio o transición entre dos estados

introducido por Van Gennep en 1909 para la antropología y conectado al espacio por Turner en 1967

han habido interpretaciones espaciales y mucha teoría, pero no hay un entendimiento común del concepto ni de su aplicación

van Eyck y el resto del team 10 - '62, proponen una filosofía de la puerta, el uso del in-between o del umbral para resolver divisiones espaciales

Hertzberger - '91, el umbral es un espacio por derecho propio, clave para la transición y conexión (para difuminar bordes) de áreas en tensión; además de que un edificio debe ser una estructura que permita al usuario interpretarla y definir cómo habitarla

Zukin - '91, el estado de liminalidad es la difusión de bordes entre lo público y lo privado

Rendell - 2012, la liminalidad es un estado de transición o umbral definido para difuminar el in-between, involucra la interrelación entre dos fenómenos y una reconciliación entre polaridades espaciales (relacionada con zumthor)

las características espaciales de estos espacios hace que los liguen con características poéticas

el continuo público-privado da vida a la arquitectura e identidad a sus usuarios

"las condiciones para la privacidad y mantener el contacto entre usuarios son igualmente esenciales, justo como los umbrales son necesarios para la interacción social y los bordes para preservar límites personales"

1 note

·

View note

Text

PORNOPTICON

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Agrest, Diana, “Architecture from Without: Body, Logic, and Sex,” Assemblage 7 (October 1988), pp. 28-41.

Agrest, Diana, Patricia Conway, and Leslie Kanes Weisman (eds.), The Sex of Architecture (New York: Abrams, 1997).

Bajac, Quentin and Didier Ottinger (eds.), Dreamlands. Des parcs d’attractions aux cités du future (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2010).

Bancel, Nicolas et al., Zoos humains. De la Vénus Hottentote aux reality shows (Paris: La Découverte, 2002).

Banham, Reyner, Age of Masters: A Personal View of Modern Architecture (New York: Harper and Row, 1966).

Baudrillard, Jen, “Disneyworld Company,” Libération, March 4, 1996.

—, Utopia Deferred, Writing for Utopie, 1967-1978 (New York: Semiotext(e), 2006).

Bentham, Jeremy, Panopticon Writings (New York: Verso, 1995).

Birkin, Lawrence, Consuming Desire: Sexual Science and the Emergence of a Culture of Abundance, 1817-1914 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1988).

Bruno, Giuliana, “Bodily Architectures,” Assemblage 19 (December 1992), p.106.

—, “Site-seeing: Architecture and the Moving Image,” Wide Angle 19.4 (1997), pp. 8-24.

Bueno, María José, “Le panopticon érotique de Ledoux,” Dix-huitième siècle 22 (1990), pp. 413-21.

Butler, Judith, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (New York: Routledge, 1993).

—, Excitable Speech: The Politics of the Performative (New York: Routledge, 1997).

—, Giving an Account of Oneself (New York: Fordham University Press, 2005).

—, the Psychic Life of Power: Theories on Subjection (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997).

Califia, Pat, Public Sex: The Culture of Radical Sex (Pittsburgh: Cleis Press, 1994).

Case, Sue Ellen, Feminism and Theater (London: Macmillan, 1998).

Cass, Jeffrey, “Egypt on Steroids: Luxor Las Vegas and Postmodern Orientalism,” in Medina Lasanky and Brian McLaren (eds.), Architecture and Tourism: Perceptions, Performance and Place (Oxford: Berg, 2004).

Chapman, Michel, “Architecture and Hermaphroditism: Gender Ambiguity and the Forbidden Antecedents of Architectural Form,” Queer Space: Centers and Peripheries, Conference Proceedings, Sydney (2007), pp. 1-7.

Colomina, Beatriz, “Architectureproduction,” in Kester Rattenbury (ed.), This is Not Architecture: Media Constructions (New York: Routledge, 2002), pp. 207-21.

—, “Media as Modern Architecture,” in Anthony Vidler (ed.), Architecture: Between Spectacle and Use (New Haven: The Clark Institute/Yale University Press, 2008).

—, “The Media House,” Assemblage 27 (August, 1995), pp. 55-56.

—, Privacy and Publicity: Architecture as Mass Media (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996).

Colomina, Beatriz (ed.), Sexuality and Space (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1992).

Debord, Guy, The Society of Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York: Zone Books, 1995).

DeJean, Joan, The Reinvention of Obscenity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002).

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari, Mille plateau. Capitalisme et schizophrénie 2 (Paris: Minuit, 1980).

—, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia II (London: Continuum, 1987).

Derrida, Jacques, Monolingualism of the Other, Or the Prosthesis of Origin, trans. Patric Mensah (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 1998).

de Sade, Marquis, “Projet de création de lieux de prostitution, organisés, entretenus et dirigés par l’État,” in Joseph F. Michaud, Biographie Universelle (Graz: Akademische Druck-U. Verlagsanstal, 1968).

Downey, Georgina and Mark Taylor, “Curtains and Carnality: Processual Seductions in Eighteenth Century Text and Space,” in Imagining: Proceedings of the 27th International Sahanz Conference, 30 June-2 July 2010 (New-castle, New South Wales).

Eisenstein, Sergei M., “Montage and Architecture,” Assemblage 10 (1989), pp. 110-31.

Fludernik, Monika, “Carceral Topography: Spatiality, Liminality and Corporality in the Literary Prison,” Textual Practice 13.1 (1999), pp. 43-47.

Foucault, Michel, Abnormal: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1974-75 (New York: Picador, 2003).

—, The Archeology of Knowledge (New York: Pantheon Books, 1972).

—, “Des espaces autres,” Revue d’Archittetura cronache e storia 13.150 (1968), pp. 822-23.

—, “Des espaces autres,” Revue d’Architecture (October 1984), pp. 46-49.