#longipteryx

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Direct evidence of frugivory in the Mesozoic bird Longipteryx contradicts morphological proxies for diet

Jingmai O’Connor, Alexander Clark, Fabiany Herrera, Xiaoting Zheng, Han Hu, Zhonghe Zhou

Summary

Diet is one of the most important aspects of an animal’s ecology, as it reflects direct interactions with other organisms and shapes morphology, behavior, and other life history traits. Modern birds (Neornithes) have a highly efficient and phenotypically plastic digestive system, allowing them to utilize diverse trophic resources, and digestive function has been put forth as a factor in the selectivity of the end-Cretaceous mass extinction, in which only neornithine dinosaurs survived. Although diet is directly documented in several early-diverging avian lineages, only a single specimen preserves evidence of diet in , the dominant group of terrestrial Cretaceous birds. Morphology-based predictions suggest enantiornithines were faunivores, although the absence of evidence contrasts with the high preservation potential and relatively longer gut-retention times of these diets. Longipteryx is an unusual Early Cretaceous enantiornithine with an elongate rostrum; distally restricted dentition; large, recurved, and crenulated teeth; and tooth enamel much thicker than other paravians. Statistical analysis of rostral length, body size, and tooth morphology predicts Longipteryx was primarily insectivorous. Contrasting with these results, two new specimens of Longipteryx preserve gymnosperm seeds within the abdominal cavity interpreted as ingesta. Like Jeholornis, their unmacerated preservation and the absence of gastroliths indicate frugivory. As in Neornithes, complex diets driven by the elevated energetic demands imposed by flight, secondary rostral functions, and phylogenetic influence impede the use of morphological proxies to predict diet in early-diverging avian lineages.

Read the paper here:

Direct evidence of frugivory in the Mesozoic bird Longipteryx contradicts morphological proxies for diet: Current Biology (cell.com)

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossilized seeds reveal fruit-eating habits of ancient bird

- By Nuadox Crew -

Researchers discovered fossilized seeds in the stomach of Longipteryx chaoyangensis, a 120-million-year-old bird, revealing it ate fruits.

Previously, it was believed that this species fed on fish or insects due to its long beak and strong teeth. This finding challenges those assumptions and suggests the bird had a varied diet.

Researchers now hypothesize that Longipteryx’s beak and teeth, which resemble those used by modern hummingbirds in combat, may have evolved for non-dietary purposes like social or sexual selection.

The study also raises broader questions about interpreting fossil traits to infer animal behavior.

Image: Longipteryx skull displaying its teeth. Credit: Xiaoli Wang.

Image: A photograph of the stomach contents of a fossilized Longipteryx, highlighting three round seed structures. Credit: Xiaoli Wang.

Image: A modern hummingbird, Androdon aequatorialis, with tooth-like structures at the tip of its beak used for fighting. Credit: Kate Golembiewski.

Header image: An illustration of Longipteryx, a fossil bird featuring unusually strong teeth located at the tip of its beak. Credit: Ville Sinkkonen (a grey filter was added).

Read more at Field Museum/SciTechDaily

Scientific paper: “Direct evidence of frugivory in the Mesozoic bird Longipteryx contradicts morphological proxies for diet” by Jingmai O’Connor, Alexander Clark, Fabiany Herrera, Xin Yang, Xiaoli Wang, Xiaoting Zheng, Han Hu and Zhonghe Zhou, 10 September 2024, Current Biology.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2024.08.012

Read Also

New fossil brings us a step closer to unravelling the mystery of feather evolution

0 notes

Text

Este passarinho pré-histórico andava armado até os dentes

Por Augusto Dala Costa • Editado por Luciana Zaramela Imagem: Ville Sinkkonen/Current Biology Cientistas descobriram que um pássaro com dentes, contemporâneo dos dinossauros, não era carnívoro, mas sim comia sementes. Desde 2020, quando o primeiro fóssil do Longipteryx chaoyangensis foi encontrado, na China, o bico alongado e cheio de dentes levou a ciência a crer que o animal teria comido…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Palaeontologists have found birds with teeth and told us what they ate

Palaeontologists have found birds with teeth and told us what they ate A recent discovery in the field of palaeontology has shed light on the behaviour of ancient birds.Researchers have found seeds preserved in the fossilised remains of one of the earliest birds, Longipteryx chaoyangensis, in their stomachs, indicating that they fed on fruit. via en.socportal.info

0 notes

Text

MOSZOIC BOOK 1 N 2

=

CAVE HUMANS

Deinonychus antirrhopus

Chasmosaurus belliS

SPINAURS

Utahraptor ostrommaysiS

BaryonyxS

Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis

Onchopristus dunkleiS

Dimorphodon macronyxS

Sarcosuchus imperatorS

TRISRTOPS

Madtsoia baiS

STAGOAURS

RAPTORS

Tapejara wellnhoferi, Darwinopterus modularis, Pteranodon Igens, Tupuxuara longicristatus and Microraptor zhaoianus

Parasaurolophus walkeriS

Centrosaurus apertus

Brontosaurus excelsus

Beelzebufo ampinga TREE FROGS

Troodon Formosus

TREXES

Deinosuchus hatcheriS

Quetzalcoatlus northropi FLY DINOS

Centrosaurus apertus

LongipteryxES

[ FOUND IN MOSOZIC ]

1 note

·

View note

Text

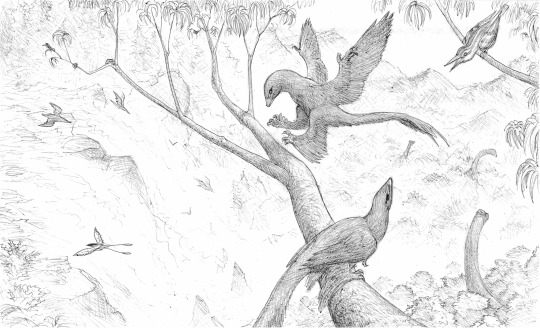

Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation

An illustration sketched with a ballpoint pen during my breaks at work (we've had a couple of slow days recently).

Based on some of the vertebrate fossils known from the Jiufotang Formation in China's Liaoning Province.

Foreground: several generic caterpillars, two Microraptor specimens, and a bird based on Longipteryx.

Background: one Confuciusornis, more Longipteryx-based birds, some generic titanosaurs.

#liaoning#china#early cretaceous#microraptor#confuciusornis#titanosaurs#longipteryx#enantiornithes#theropod#sauropod#feathered dinosaurs#birds#jiufotang formation#pen drawing#pen sketch#ballpointpen#paleoart#illustration#pen doodles

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A field guide to Mesozoic Twitter birds and other winged dinosaurs.

All can be downloaded here. Feel free to use for your own purposes.

#Palaeoblr#Dinosaurs#Birds#Twitter#Velociraptor#Microraptor#Buitreraptor#Yi#Caudipteryx#Anzu#Archaeopteryx#Jeholornis#Sapeornis#Confuciusornis#Eopengornis#Longipteryx#Schizooura#Yanornis#Ichthyornis

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

Results from the #paleostream! Natovenator, Struthiosaurus, Neuquenornis and Longipteryx

389 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Longipteryx chaoyangensis, an enantiornithine from the Early Cretaceous of China, about 120 million years ago. With a body length of only around 15cm (6″), it had a long snout tipped with a few hooked teeth and feet capable of perching -- features that indicate it may have lived very similarly to modern kingfishers, feeding on fish and small invertebrates in its swampy forest habitat.

The enantiornithines were a sort of “cousin” lineage to modern birds. Most had toothy jaws and clawed wings, and the wide variety in their skull shapes suggests that they were specialized for many different dietary niches. The entire group went extinct during the K-Pg mass extinction and left no living descendants, but during the Cretaceous they were the most widespread and diverse group of birds*, with fossils currently known from every continent except Antarctica.

* Depending on how you define “bird”.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#longipteryx#longipterygidae#enantiornithes#avialae#bird#stem-bird#opposite bird#dinosaur#art#what are birds?

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

my untreated sleep apnea was acting up buT I RETURN FROM MY ETERNAL NONRESTFUL SLUMBER to bring you our next dinosaur group race

enant groups based on Wang et al 2022 for my sanity

#dinosaurs#birds#polls#palaeoblr#hespeornithes#ichthyornis#enantiornithes#euornithes#gansus#apsaravis#longipteryx#pengornis#avisaurus

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Longipteryx chaoyangensis

By José Carlos Cortés on @quetzalcuetzpalin-art

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Longipteryx chaoyangensis

Name Meaning: One with Long Wing Feathers

First Described: 2001

Described By: Zhang et al.

Classification: Dinosauria, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Enantiornithes, Eoenantiornithes

Longipteryx is a well known Jiufotang Bird, living about 120 million years ago in the Aptian age of the Early Cretaceous. It is, thus, yet another in the long line of birdy animals from the Jehol Biota, and one of the many Opposite Birds known from the region. Longipteryx is known from multiple skeletons and was very well preserved, allowing for some decent idea of what it was like in life. It had a wingspan of about 34 centimeters and a body length of about 16 centimeters, and an estimated tail length of 18 centimeters, meaning that it had very large and broad wings, and a stubby tail without rectrices. It also had short legs.

By El Fosilmaníaco, CC BY SA 4.0

Longipteryx had a long bill, with large curved teeth in the tips of the jaw. These teeth were large and conical but also flattened and curved, indicating that Longipteryx may have been a fishing organism, catching small fish out of the swamps and lakes in its environment. It probably would have been a decent percher, and may have even been arboreal, which might indicate that it was an insectivore instead of a piscivore. It is also entirely possible that it had a mixed lifestyle of both - with so many other animals to compete against for food in its environment, exploiting multiple sources of food may have been a decent ecological strategy. It may have lived very similarly to a modern-day kingfisher.

By Scott Reid on @drawingwithdinosaurs

Longipteryx lived in a forested, temperate to subtropical swamp near stagnant lakes and rivers, and with its broad wings it probably used flapping flight to maneuver amongst the trees and, if it did fish for food, dive amongst these bodies of water looking for prey. It had a strengthened ribcage, which probably would have aided it in flight or support for its digestive system. It was very distinctive, even amongst Enantiornithines, for its unique combination of morphological traits.

Sources:

Martyniuk, M. P. 2012. A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and other Winged Dinosaurs. Pan Aves; Vernon, New Jersey.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Longipteryx

Shout out goes to @aagx3!

#longipteryx#longipteryx chaoyangensis#dinosaur#bird#palaeoblr#birblr#aagx3#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#דינוזאור#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍#恐龙#динозавр

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

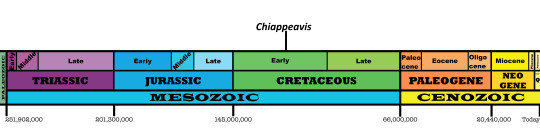

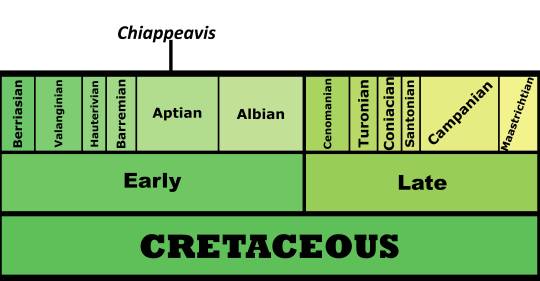

Chiappeavis magnapremaxillo

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: Chiappe’s Bird

First Described By: O’Connor et al, 2016

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Enantiornithes, Cathayornithiformes

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 120 million years ago, in the Aptian age of the Early Cretaceous

Chiappeavis is known from the Jiufotang Formation of China, specifically in the Shangheshou Beds

Physical Description: Chiappeavis was an Opposite Bird, ie the group of bird-like dinosaurs that were extremely diverse and widespread during the Cretaceous period. Chiappeavis is known from a nearly complete skeleton, including some feather impressions. It was a fairly large bird, probably around 20 or so centimeters (though this is a very rough estimate). It had a small snout, with small pointed teeth inside of it, and a fairly large head. Its body was long, and it had large wings - good for more powerful flying as opposed to tighter maneuvering in between trees. Interestingly enough, Chiappeavis had a giant tail fan, which was not actually universal among Opposite BIrds as it is in modern birds. It also had fairly thick, strong feet.

Diet: It is probable that Chiappeavis fed mainly on arthropods and other hard invertebrates.

By Ripley Cook

Behavior: It is uncertain what the behavior of Chiappeavis was, given that we do not have extensive skeletons of this dinosaur. Still, it probably wouldn’t have flitted about the trees as much as birds with wings better built for maneuvering. The tail fan of Chiappeavis probably would have been extremely useful in sexual display, as well as other forms of communication - especially since it does not appear to have been very good at generating lift during flight (hence it not being widespread in other Opposite Birds). As such, it is more likely than not that Chiappeavis would have been fairly social, living in groups of multiple birds which communicated and recognized each other with feather displays. This, therefore, leads us to yet another likely hypothesis: that it took care of its young, at least to some extent. Beyond that, the behavior of Chiappeavis is a bit of a question - though it may have been able to dig out insects and other grubs with its strong feet, and then bit into the tough exteriors of these animals with its many needle-like teeth.

Ecosystem: The Jiufotang Formation was one of the Jehol Biota ecosystems, aka a group of extremely diverse and lush environments that preserved birdie dinosaurs of the Early Cretaceous with great detail. In that, Chiappeavis is one of many dinosaurs found in this location with extensive feather preservation. TheJiufotang Environment was a dense forest, surrounding an extensive number of lakes, and near volcanically active mountains. Still, it isn’t quite as well known as the earlier Yixian formation, and in fact doesn’t seem to have as many plants preserved to inform the exact environment and temperature. Still, it’s reasonable to suppose it may have also been a temperate ecosystem, like the earlier Yixian Formation, potentially even with snow.

By Jack Wood

In this environment, there were an extremely wide variety of animals. There was a decent diversity of fish, quite a few kinds of mammals, and the weird, unclassifiable Choristoderes were represented by Philydrosaurus, Ikechosaurus, and Liaoxisaurus. This ecosystem was lousy with pterosaurs, featuring a variety of Chaoynagopterids - like Chaoyangopterus itself, Eoazhdarcho, Jidapterus, and Shenzhoupterus; Pteranodonts like Guidraco, Ikrandraco, Liaoningopterus, Nurhachius, Liaoxipterus, and Linlongopterus; Tapejarids like “Huaxiapterus”, (probably) Nemicolopterus, and Sinopterus; and the weirdly late-surviving Anurognathid Vesperopterylus.

As for dinosaurs, there were many, and most were bird like! There was of course the Ankylosaur Chuanqilong, and the early Ceratopsian Psittacosaurus; there was also an unnamed titanosaur. There was a Tyrannosauroid, SInotyrannus, the Chickenparrot Similicaudipteryx, the raptor Microraptor, and tons of early Avialans like Confuciusornis, Dalianraptor, Jeholornis, Omnivoropteryx, Sapeornis, Shenshiornis, and Zhongjianornis. There were also “true” birds (ie, the line of dinosaurs that would evolve into those we see today) such as Bellulornis, Piscivoravis, Archaeorhynchus, Chaoyangia, Jianchangornis, Parahongshanornis, Schizooura, Songlingornis, Yanornis, and Yixianornis. However, the most diverse group of dinosaurs were the Opposite Birds, of which Chiappeavis was only one of many. There was Alethoalaornis, Boluochia, Bohaiornis, Cathayornis, Cuspirostrisornis, Dapingfangornis, Eocathayornis, Piscivorenantiornis, Pengornis, Gracilornis, Huoshanornis, Largirostrornis, Longchengornis, Longipteryx, Rapaxavis, Shangyang, Sinornis, and Xiangornis - just to name a few! As such the Jiufotange remains as a rich ecosystem in which to study the evolution of this fantastic group of Cretaceous dinosaurs.

By Scott Reid

Other: Chiappeavis is probably not its own thing - it is one of a number of Opposite Birds described without substantial evidence that it was a distinct genus and, indeed, many researchers consider them to be members of other genera. In this case, Chiappeavis is probably the same as Pengornis. Still, until it is officially lumped in, it must be treated as its own genus. It had a lot of similarities to Pengornis, regardless, indicating the two may belong to a larger clade of Opposite Birds. In short, Opposite Bird Phylogeny is kind of a mess, and needs a lot more intensive work than has currently been done.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Czerkas, S. A., D. Zhang, J. Li and Y. Li. 2002. Flying dromaeosaurs. In S. J. Czerkas (ed.), Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight. The Dinosaur Museum Journal 1. The Dinosaur Museum, Blanding, UT 96-126

Czerkas, S. A., and Q. Ji. 2002. A preliminary report on an omnivorous volant bird from northeast China. In S. J. Czerkas (ed.), Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight. The Dinosaur Museum Journal 1. The Dinosaur Museum, Blanding, UT 127-135

Dong, Z.-M., Y.-W. Sun, and S.-Y. Wu. 2003. On a new pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Chaoyang Basin, Western Liaoning, China. Global Geology 22:1-7

Dong, Z., and J. Lü. 2005. A new ctenochasmatid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning Province. Acta Geologica Sinica 79(2):164-167

Dong, L., Y. Wang, and S. E. Evans. 2017. A new lizard (Reptilia: Squamata) from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China, with a taxonomic revision of Yabeinosaurus. Cretaceous Research

Evans, S. E., and Y. Wang. 2011. A gravid lizard from the Cretaceous of China and the early history of squamate viviparity. Naturwissenschaften 98:739-743

Evans, S. E., and Y. Wang. 2012. New material of the Early Cretaceous lizard Yabeinosaurus from China. Cretaceous Research 34:48-60

Gao, K.-Q., and R. C. Fox. 2005. A new choristodere (Reptilia: Diapsida) from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning Province, CHina, and phylogenetic relationships of Monjurosuchidae. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society of London 145:427-444

Gao, K.-Q., D. T. Ksepka, L. Hou, Y. Duan, and D. Hu. 2007. Cranial morphology of an Early Cretaceous monjurosuchid (Reptilia: Diapsida) from Liaoning Province of China and evolution of the choristoderan palate. Historical Biology 19(3):215-224

Han, G., and J. Meng. 2016. A new spalacolestine mammal from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota and implications for the morphology, phylogeny, and palaeobiology of Laurasian ‘symmetrodontans’. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 178:343-380

He, H.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Zhou, Z.H.; Wang, F.; Boven, A.; Shi, G.H.; Zhu, R.X. (2004). "Timing of the Jiufotang Formation (Jehol Group) in Liaoning, northeastern China, and its implications". Geophysical Research Letters. 31 (13): 1709.

Hou, L., and J. Zhang. 1993. [A new fossil bird from Lower Cretaceous of Liaoning]. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 31(3):217-224

Hou, L. H. 1997. Mesozoic Birds of China.

Hu, D., L. Li, L. Hou and X. Xing. 2010. A new sapeornithid bird from China and its implication for early avian evolution. Acta Geologica Sinica 84(3):472-482

Hu, L. Li, L. Hou and D., X. Xu. 2011. A new enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31(1):154-161.

Hu, D.-Y., X. Xu, L. Hou and C. Sullivan. 2012. A new enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of Western Liaoning, China, and its implications for early avian evolution. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32(3):639-645

Hu, Zhou and O'Connor, 2014. A subadult specimen of Pengornis and character evolution in Enantiornithes. Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 52(1), 77-97.

Hu, D., Y. Liu, J. Li, X. Xu, and L. Hou. 2015. Yuanjiawaornis viriosus, gen. et sp. nov., a large enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. Cretaceous Research 55:210-219

Hu, O'Connor and Zhou, 2015. A new species of Pengornithidae (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Lower Cretaceous of China suggests a specialized scansorial habitat previously unknown in early birds. PLoS ONE. 10(6), e0126791.

Ji, Q., S.-a. Ji, and L.-j. Zhang. 2009. First large tyrannosauroid theropod from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota in northeastern China. Geological Bulletin of China 28(10):1369-1374

Li, J.-J., J.-C. Lü, and B.-K. Zhang. 2003. A new Lower Cretaceous sinopteroid pterosaur from western Liaoning, China. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 42(3):442-447

Li, L., Y. Duan, D. Hu, L. Wang, S. Cheng and L. Hou. 2006. New Eoenantiornithid Bird from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Western Liaoning, China. Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition) 80(1):38-41

Li, Q., J. A. Clarke, K.-Q. Gao, C.-F. Zhou, Q. Meng, D. Li, L. D'Alba and M. D. Shawkey. 2014. Melanosome evolution indicates a key physiological shift within feathered dinosaurs. Nature 507:350-353.

Li, Z., Z. Zhou, M. Wang and J. A. Clarke. 2014. A new specimen of large-bodied basal enantiornithine Bohaiornis from the Early Cretaceous of China and the inference of feeding ecology in Mesozoic birds. Journal of Paleontology 88(1):99-108

Lu, J.-C., Q.-J. Meng, B.-P. Wang, DLiu, C.-Z. Shen and Y.-G. Zhang. 2017. Short note on a new anurognathid pterosaur with evidence of perching behaviour from Jianchang of Liaoning Province, China. In D. W. E. Hone, M. P. Witton, D. M. Martill (eds.), Geological Society of London Special Publications 455:95-104.

Mortimer, M. 2016. Chiappeavis is just another Pengornis. Theropod Database Blog.

O'Connor and Chiappe, 2011. A revision of enantiornithine (Aves: Ornithothoraces) skull morphology. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 9(1), 135-157.

O'Connor, J. K., Y. -G. Zhang, L. M. Chiappe, Q. Meng, Q. Li and D. Liu. 2013. A new enantiornithine from the Yixian Formation with the first recognized avian enamel specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33(1):1-12.

O'Connor, Zheng, Sullivan, Chuong, Wang, Li, Wang, Zhang and Zhou, 2015. Evolution and functional significance of derived sternal ossification patterns in ornithothoracine birds. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 28(8), 1550-1567.

O’Connor, J. K., X. Wang, X. Zheng, H. Hu, X. Zhang, Z. Hou. 2016. An Enantiornithine with a Fan-Shaped Tail, and the Evolution of the Rectricial Complex in Early Birds. Current Biology 26: 114 - 119.

O’Connor, J. K., X.-T. Zheng, H. Hu. X. Wang, Z.-H. Zhou, 2017. The morphology of Chiappeavis magnapremaxillo (Pengornithida: enantiornithes) and a comparison of aerodynamic function in Early Cretaceous avian tail fans. Vertebrata Palasiatica 55: 41 - 58.

Wang, X., T. Rodrigues, S. Jiang, X. Cheng, and A. W. A. Kellner. 2014. An Early Cretaceous pterosaur with an unusual mandibular crest from China and a potential novel feeding strategy. Scientific Reports 4(6329).

Wang, M., Z.-H. Zhou, and S. Zhou. 2016. A new basal ornithuromorph bird (Aves: Ornithothoraces) from the Early Cretaceous of China with implication for morphology of early Ornithuromorpha. 176(1):207-223.

Zhou, S., Z. Zhou, J. K. O’Connor. 2013. A new piscivorous ornithuromorph from the Jehol Biota. Historical Biology 26 (5): 608 - 618.

Zhou, Z.-h., F. Jin, and J.-y. Zhang. 1992. [Preliminary report on a Mesozoic bird from Liaoning, China]. Kexue Tongbao 1992(5):435-437

Zhou, Z. 1995. Discovery of a new enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 33(2):99-113

Zhou, X., and F. Zhang. 2001. Two new ornithurine birds from the Early Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. Chinese Science Bulletin 46(15):1258-1264

Zhou, Z. 2002. A new and primitive enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22(1):49-57

Zhou, Z., and F. Zhang. 2002. A long-tailed, seed-eating bird from the Early Cretaceous of China. Nature 418:405-409

Zhou, Z., and F. Zhang. 2002. Largest bird from the Early Cretaceous and its implications for the earliest avian ecological diversification. Naturwissenschaften 89(1):34-38

Zhou, X., and F. Zhang. 2003. Anatomy of the primitive bird Sapeornis chaoyangensis from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40:731-747

Zhou, Z., J. Clarke, F. Zhang and O. Wings. 2004. Gastroliths in Yanornis: an indication of the earliest radical diet-switching and gizzard plasticity in the lineage leading to living birds?. Naturwissenschaften 91(12):571-574

Zhou, Clarke and Zhang, 2008. Insight into diversity, body size and morphological evolution from the largest Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird. Journal of Anatomy. 212, 565-577.

Zhou, Z.-H., F. -C. Zhang, and Z. Li. 2009. A new basal ornithurine bird (Jianchangornis microdonta gen. et sp. nov.) from the Lower Cretaceous of China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 10:299-310

Zhou, Z., F. Zhang, and Z. Li. 2010. A new Lower Cretaceous bird from China and tooth reduction in early avian evolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277:219-227

#Chiappeavis magnapremaxillo#Chiappeavis#Opposite Bird#Bird#Dinosaur#Enantiornithine#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Birds#Cretaceous#Eurasia#Insectivore#Mesozoic Monday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

177 notes

·

View notes

Note

How true is the old stereotype that avialans can be diagnosed from other maniraptorans by unserrated teeth?

It’s true that avialan teeth generally lack serrations (except in Longipteryx). However, teeth without serrations are also found in oviraptorosaurs, alvarezsaurids, and some troodontids, so it’s not specific to avialans among maniraptors.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Piscivoravis lii

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Fish Eating Bird

First Described By: 2013

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Songlingornithidae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 120 million years ago, in the Aptian age of the Early Cretaceous

Piscivoravis is known from the Shangheshou Beds of the Jiufotang Formation in Liaoning, China

Physical Description: Piscivoravis was a fairly large proto-bird, growing between 30 and 35 centimeters long. It had a strong wishbone, which would have allowed for extensive chest muscles, giving it better flight ability than most of its relatives at the time. It had large claws and digits on its feet and hands which would have been very noticeable in the wings - it’s possible it may have used those claws to cling to branches and tree trunks. Piscivoravis was preserved with feathers, which show that it had an alula. Alulas are a group of three to six small, stiff feathers growing off of the first digit in modern birds - not preserved often in Mesozoic birds, scientists have limited themselves to looking for the specialized structure in the first finger that would indicate their presence. However, Piscivoravis doesn’t have that structure - indicating the alula feathers evolved before the structure did. It also had a full fan of tail feathers - a distinctive trait of the birdie dinosaurs that would become birds proper. The feathers were broad and rounded to form a single aerodynamic surface, which would have helped it to fly.

Diet: Piscivoravis was found with fish preserved in its digestive tract, making it one of the few confirmed piscivorous Mesozoic birds.

Behavior: Piscivoravis would spend a lot of its time around the lakes of its environment, grabbing fish out of the water - a unique niche for it that would have helped it to avoid competition with other animals in its very diverse environment. It would have swallowed the food and separated it into digestible parts and non-digestible parts, and formed the latter into a pellet - much like modern hawks and owls do. This was preserved in its stomach, and it would then vomit up the pellet to save energy trying (and failing) to digest it.

By Scott Reid

As a strong flier, it’s possible that Piscivoravis would source over the lakes like some shorebirds today, looking for traces of fish and other aquatic sources of food under the surface. We don’t know how well it could see, however, to test if it would be able to spot such prey. It’s possible - since this was a system of lakes surrounded by forest - that Piscivoravis may have peered down at the lakes from trees (held onto with strong claws), then used their strong flight to fly down quickly towards the sources of food.

As a dinosaur, Piscivoravis most likely took care of its young, though it’s difficult to know either way without more fossils. It is uncertain whether or not it would have lived in groups - either possibility, solitary or social life, seems possible.

Ecosystem: Piscivoravis lived in the Jiufotang Formation, the later of the Jehol Biota formations that showcase the initial evolution of a lot of modern groups - especially birds, placental mammals, and flowers. It was a system of lakes, surrounded by a temperate forest. Active volcanoes nearby would explode on occasion, leading to rapid covering and then preservation of the life in the forest. The earlier Yixian Formation is somewhat better known and more diverse than the Jiufotang, but there was still a lot of fascinating creatures in the Jiufotang. Piscivoravis is known from the Shangheshou Bed, aka the second and third members of the formation, where a lot of the more famous animals of the environment are found. The environment was probably still heavily forested, mostly populated with coniferous trees and ferns, but with some burgeoning flowers as well. There was a variety of frogs and fish for Piscivoravis to feed on, though most of the named ones come from other parts of the formation.

Mammals were present in the formation - notably Lactodens and Liaconodon. The oddball, crocodile-esque Choristoderes were represented by Philydrosaurus and Ikechosaurus. Turtles include Perochelys and Liaochelys. There was the famed Jiufotang Lizard Yabeinosaurus as well. There were a lot of pterosaurs, including Sinopterus, Linlongopterus, Liaoxipterus, Chaoyangopterus, Longchengpterus, Eoazhdarcho, Huaxiapterus, Hongshanopterus, Jidapterus, and Shenzhoupterus. And this was just the non-dinosaurs.

By José Carlos Cortés

Dinosaurs included - well, there were a lot of them. The only Ornithischian known from this member was Psittacosaurus. There were a few non-Avialan theropods, too, such as Sinotyrannus, Microraptor and Similcaudipteryx. Still, the fast majority of dinosaurs present were birdie dinosaurs, which I’m just going to list now: Longipteryx, Confuciusornis, Omnivoropteryx, Sapeornis, Sinornis, Yixianornis, Bohaiornis, Parabohaiornis, Longusunguis, Juehuaornis, Parapengornis, Fortunguavis, Cathayornis, Largirostrornis, Yanornis, Gracilornis, Eocathayornis, Jeholornis, Schizooura, Zhongjianornis, Jianchangornis, Archaeorhynchus, Songlingornis, Chaoyangia, Longchengornis, Boluochia, Houornis, Xiangornis, Huoshanornis, Pengornis, Dapingfangornis, Piscivorenantiornis, Parahongshanornis, Alethoalaornis, Yuanjiawaornis, and Bellulornis. Feel free to dig through the ADAD blog to find out about all of these. Piscivoravis probably would have feared Sinotyrannus the most out of all these members of its environment, in terms of what would eat it.

Other: Piscivoravis was a Songlingornithid, a group of early very-near-birds found in the Aptian age of China. Many other kinds coexisted with Piscivoravis, and surprisingly, a lot of the group of birdie dinosaurs that became birds (the Euornithes) had at least somewhat aquatic lifestyles. So, full beaks in modern birds evolved in water-based environments, though we’re not entirely sure why.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Czerkas, S. A., D. Zhang, J. Li and Y. Li. 2002. Flying dromaeosaurs. In S. J. Czerkas (ed.), Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight. The Dinosaur Museum Journal 1. The Dinosaur Museum, Blanding, UT 96-126

Czerkas, S. A., and Q. Ji. 2002. A preliminary report on an omnivorous volant bird from northeast China. In S. J. Czerkas (ed.), Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight. The Dinosaur Museum Journal 1. The Dinosaur Museum, Blanding, UT 127-135

Dong, Z.-M., Y.-W. Sun, and S.-Y. Wu. 2003. On a new pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Chaoyang Basin, Western Liaoning, China. Global Geology 22:1-7

Dong, Z., and J. Lü. 2005. A new ctenochasmatid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning Province. Acta Geologica Sinica 79(2):164-167

Dong, L., Y. Wang, and S. E. Evans. 2017. A new lizard (Reptilia: Squamata) from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China, with a taxonomic revision of Yabeinosaurus. Cretaceous Research

Evans, S. E., and Y. Wang. 2011. A gravid lizard from the Cretaceous of China and the early history of squamate viviparity. Naturwissenschaften 98:739-743

Evans, S. E., and Y. Wang. 2012. New material of the Early Cretaceous lizard Yabeinosaurus from China. Cretaceous Research 34:48-60

Gao, K.-Q., and R. C. Fox. 2005. A new choristodere (Reptilia: Diapsida) from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning Province, CHina, and phylogenetic relationships of Monjurosuchidae. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society of London 145:427-444

Gao, K.-Q., D. T. Ksepka, L. Hou, Y. Duan, and D. Hu. 2007. Cranial morphology of an Early Cretaceous monjurosuchid (Reptilia: Diapsida) from Liaoning Province of China and evolution of the choristoderan palate. Historical Biology 19(3):215-224

Han, G., and J. Meng. 2016. A new spalacolestine mammal from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota and implications for the morphology, phylogeny, and palaeobiology of Laurasian ‘symmetrodontans’. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 178:343-380

Hou, L., and J. Zhang. 1993. [A new fossil bird from Lower Cretaceous of Liaoning]. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 31(3):217-224

Hou, L. H. 1997. Mesozoic Birds of China.

Hu, D., L. Li, L. Hou and X. Xing. 2010. A new sapeornithid bird from China and its implication for early avian evolution. Acta Geologica Sinica 84(3):472-482

Hu, D.-Y., X. Xu, L. Hou and C. Sullivan. 2012. A new enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of Western Liaoning, China, and its implications for early avian evolution. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32(3):639-645

Hu, D., Y. Liu, J. Li, X. Xu, and L. Hou. 2015. Yuanjiawaornis viriosus, gen. et sp. nov., a large enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. Cretaceous Research 55:210-219

Hu, H., J. K. O'Connor, and Z. Zhou. 2015. A new species of Pengornithidae (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Lower Cretaceous of China suggests a specialized scansorial habitat previously unknown in early birds. Plos One 10(6):e0126791

Ji, Q., S.-a. Ji, and L.-j. Zhang. 2009. First large tyrannosauroid theropod from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota in northeastern China. Geological Bulletin of China 28(10):1369-1374

Evans, Q., and Y. Wang. 2011. A gravid lizard from the Cretaceous of China and the early history of squamate viviparity. Naturwissenschaften 98:739-743

Li, J.-J., J.-C. Lü, and B.-K. Zhang. 2003. A new Lower Cretaceous sinopteroid pterosaur from western Liaoning, China. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 42(3):442-447

Li, L., Y. Duan, D. Hu, L. Wang, S. Cheng and L. Hou. 2006. New Eoenantiornithid Bird from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Western Liaoning, China. Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition) 80(1):38-41

Li, Z., Z. Zhou, M. Wang and J. A. Clarke. 2014. A new specimen of large-bodied basal enantiornithine Bohaiornis from the Early Cretaceous of China and the inference of feeding ecology in Mesozoic birds. Journal of Paleontology 88(1):99-108

Li, L., D.-y. Hu, Y. Duan, E=p Gong, and L.-h. Hou. 2007. Alethoalaornithidae fam. nov.: a new family of enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica 46(3):365-372

Li, L., J.-Q. Wang, and S.-L. Hou. 2011. A new ornithurine bird (Hongshanornithidae) from the Jiufotang Formation of Chaoyang, Liaoning, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 49(2):195-200

Li, L., W. G. Joyce, and J. Liu. 2015. The first soft-shelled turtle from the Jehol Biota of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 35(2):e909450

Liu, J. 2004. A nearly complete skeleton of Ikechosaurus pijiagouensis sp. nov. (Reptilia: Choristodera) from the Jiufotang Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Liaoning, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 42(2):120-129

Lü, J., and C. Yuan. 2005. New tapejarid pterosaur from western Liaoning, China. Acta Geologica Sinica 79(4):453-458

Lü, J., and Q. Ji. 2005. New azhdarchid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of western Liaoning. Acta Geologica Sinica 79(3):301-307

Lü, J., X. Jin, D. M. Unwin, L. Zhao, Y. Azuma and Q. Ji. 2006. A new species of Huaxiapterus (Pterosauria: Pterodactyloidea) from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China with comments on the systematics of tapejarid pterosaurs. Acta Geologica Sinica 80(3):315-326

Lü, J., J. Liu, C. Gao, Q. Meng, and Q. Ji. 2006. New material of pterosaur Sinopterus (Reptilia: Pterosauria) from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation, Western Liaoning, China. Acta Geologica Sinica 80(6):783-789

Lü, J., D. M. Unwin, L. Xu and X. Zhang. 2008. A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China and its implications for pterosaur phylogeny and evolution. Naturwissenschften 95:891-897

Martyniuk, M. P. 2012. A Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and other Winged Dinosaurs. Pan Aves; Vernon, New Jersey.

Meng, J., Y. Wang, and C. Li. 2011. Transitional mammalian middle ear from a new Cretaceous Jehol eutriconodont. Nature 472:181-185

Norell, M. A., Q. Ji, C. Yuan, Y. Zhao, and L. Wang. 2002. 'Modern' feathers on a non-avian dinosaur. Nature 416:36-37

O’Connor, J. K.; Zhang, Y.; Chiappe, L. M.; Meng, Q.; Quanguo, L.; Di, L. 2013. A new enantiornithine from the Yixian Formation with the first recognized avian enamel specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33(1): 1 - 12.

O'Connor, J. K., C. Sun, X. Xu, X. Wang, and Z. Zhou. 2012. A new species of Jeholornis with complete caudal integument. Historical Biology 24(1):29-41

Provini, P., Z.-H. Zhou, and F.-C. Zhang. 2009. A new species of the basal bird Sapeornis from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 47(3):194-207

Rodrigues, T., S. Jiang, X. Cheng, X. Wang, and A. W. A. Kellner. 2015. A new toothed pteranodontoid (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Jiufotang Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Aptian) of China and comments on Liaoningopterus gui Wang and Zhou, 2003. Historical Biology 27(6):782-795

Wang, M., J. K. O’Connor, Z. Zhou. 2014. A new robust enantiornithine bird from the lower Cretaceous of China with scansorial adaptations. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Wang, M., and Z. Zhou. 2017. A morphological study of the first known piscivorous enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 37(2):e1278702:1-13

Wang, X., and Z. Zhou. 2002. A new pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea, Tapejaridae) from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of western Liaoning, China and its implications for biostratigraphy. Chinese Science Bulletin 47(20):1521-1527

Wang, L., L. Li, Y. Duan and S.-L. Cheng. 2006. A new iodactylid pterosaur from western Liaoning. Geological Bulletin of China 25(6):737-740

Wang, X., D. A. Campos, Z. Zhou and A. W. A. Kellner. 2008. A primitive istiodactylid pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea) from the Jiufotang Formation (Early Cretaceous), northeast China. Zootaxa 1813:1-18

Wang, X., Z. Zhang, C. Gao, L. Hou, Q. Meng and J. Liu. 2010. A new enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. The Condor 112(3):432-437

Wang, X., B. Zhao, C. Shen, S. Liu, C. Gao, X. Cheng, and F. Zhang. 2015. New material of Longipteryx (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China with the first recognized avian tooth crenulations. Zootaxa 3941(4):565-578

Wang, Y., M. E. H. Jones, and S. E. Evans. 2007. A juvenile anuran from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation, Liaoning, China. Cretaceous Research 28:235-244

Xu, X., Z. Zhou, X. Wang, X. Kuang, F. Zhang and X. Du. 2003. Four-winged dinosaurs from China. Nature 421:335-340

Zhou, C.-F. 2010. New material of Chaoyangopterus (Pterosauria: Pterodactyloidea) from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of western Liaoning, China. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen 257(3):341-350

Zhang, Z., D. Chen, H. Zhang and L. Hou. 2014. A large enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of China and its implication for lung ventilation. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 113:820-827

Zhou, S., Z. -H. Zhou, and J. K. O'Connor. 2012. A new basal beaked ornithurine bid from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 50(1):9-24

Zhou, S.-A., Z. -H. Zhou, and J. K. O'Connor. 2013. Anatomy of the basal ornithuromorph bird Archaeorhynchus spathula from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33(1):141-152

Zhou, S., Z. Zhou, J. K. O’Connor. 2013. A new piscivorous ornithuromorph from the Jehol Biota. Historical Biology 26 (5): 608 - 618.

Zhou, Z.-h., F. Jin, and J.-y. Zhang. 1992. [Preliminary report on a Mesozoic bird from Liaoning, China]. Kexue Tongbao 1992(5):435-437

Zhou, Z. 1995. Discovery of a new enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 33(2):99-113

Zhou, X., and F. Zhang. 2001. Two new ornithurine birds from the Early Cretaceous of western Liaoning, China. Chinese Science Bulletin 46(15):1258-1264

Zhou, Z. 2002. A new and primitive enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22(1):49-57

Zhou, Z., and F. Zhang. 2002. A long-tailed, seed-eating bird from the Early Cretaceous of China. Nature 418:405-409

Zhou, Z., and F. Zhang. 2002. Largest bird from the Early Cretaceous and its implications for the earliest avian ecological diversification. Naturwissenschaften 89(1):34-38

Zhou, X., and F. Zhang. 2003. Anatomy of the primitive bird Sapeornis chaoyangensis from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning, China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40:731-747

Zhou, Z., J. Clarke, F. Zhang and O. Wings. 2004. Gastroliths in Yanornis: an indication of the earliest radical diet-switching and gizzard plasticity in the lineage leading to living birds?. Naturwissenschaften 91(12):571-574

Zhou, Z., J. Clarke, and F. Zhang. 2008. Insight into diversity, body size and morphological evolution from the largest Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird. Journal of Anatomy 212(5):565-577

Zhou, Z.-H., F. -C. Zhang, and Z. Li. 2009. A new basal ornithurine bird (Jianchangornis microdonta gen. et sp. nov.) from the Lower Cretaceous of China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 10:299-310

Zhou, Z., F. Zhang, and Z. Li. 2010. A new Lower Cretaceous bird from China and tooth reduction in early avian evolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277:219-227

#Piscivoravis#Piscivoravis lii#bird#dinosaur#songlingornithid#palaeoblr#birblr#factfile#feathered dinosaurs#euornithine#Water Wednesday#piscivore#Eurasia#Cretaceous#birds#dinosaurs#prehistoric life#prehistory#paleontology#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

282 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think it’s likely that longipterygids are oversplit?

I suppose it’s possible. Shanweiniao and Longirostravis are quite similar to one another, though I think that their differences in sternal morphology are distinct enough to warrant separation for now. Probably the most likely candidates for synonymy are Boluochia and Longipteryx, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

1 note

·

View note