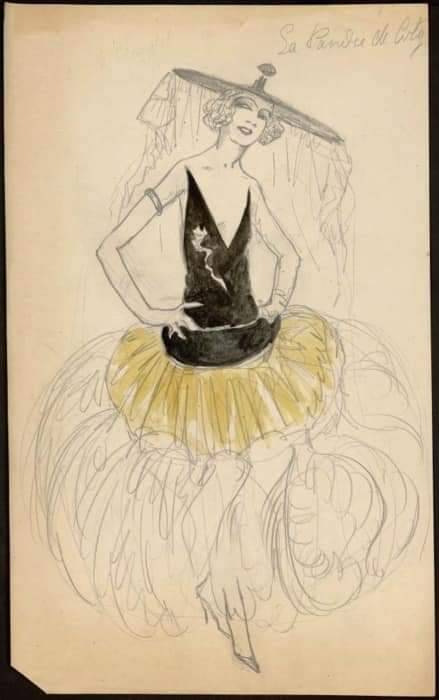

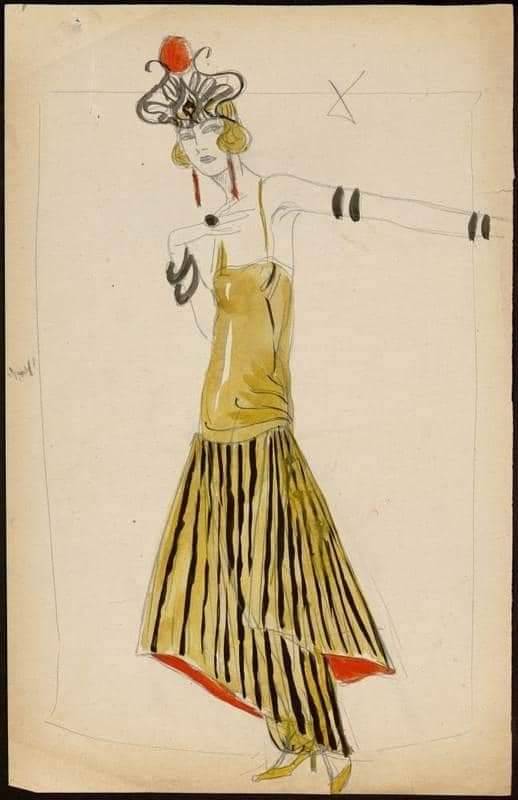

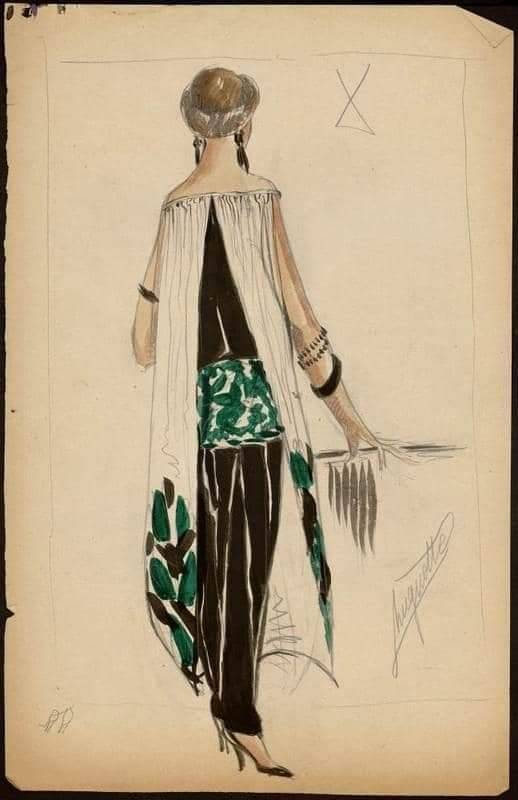

#madeleine chéruit

Text

Black Silk Dress with Sequins, 1927, French.

Designed by Madeleine Chéruit.

MFA Boston.

#paris#womenswear#extant garments#silk#sequins#dress#mfa boston#20th century#black#france#french#madeleine chéruit#house of chéruit#1927#1920s#1920s dress#1920s France#third republic

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

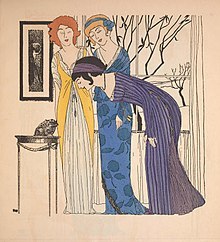

Pierre Brissaud, Je Suis Perdue: Robe d'été de Chéruit (I'm lost: Summer dress by Chéruit). La Gazette du Bon Ton, June 1913

#pierre brissaud#illustration#1913 fashion#fashion illustration#Chéruit#Maison Chéruit#Louise Chéruit#Madame Louise Chéruit#Mme Madeleine Chéruit#paris#parisian fashion#1910s fashion#1913 illustrations#mode#parisian mode#summer fashion#1910s summer fashion#edwardian#summer dress#country side#country style#chic#summer chis#art#french art#gazette du bon ton#cows#dogs#shepherd#lost

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

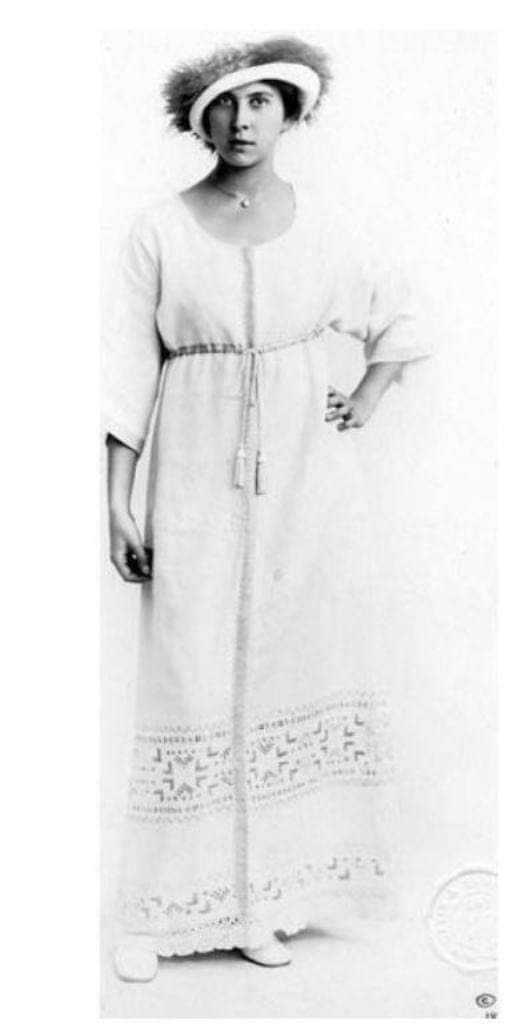

Afternoon dress by Chéruit, Les Modes 1917 (N174). Photo by Talma.

#les modes#1910s#1910s fashion#afternoon dress#chéruit#louise chéruit#madeleine chéruit#cheruit#talma

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Throwback Special: The Mysterious Madeleine Chéruit – The Girlboss Of The 1900s

If you are reading the title and wondering, “Who’s that?”, you’re not alone. She may not have been as famous as her peers like Coco Chanel or Elsa Schiaparelli, but her designs are part of fashion history. She paved the way for couturiers of her generation, and she also was the first woman to control a fashion house, something that was truly unthinkable at the time. So what was mysterious…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

France became dominant in the high fashion (couture or haute couture) industry by the end of the 19th century through the establishment of the great couturier houses.

The technology started to redefine Western society in many ways and this continued into the next decades as well.

New inventions (like cars) eased the lives of people. Activities such as sports, dance, and tea parties were growing bigger in the last decade.

The industry expanded through such Parisian fashion houses as the house of Jacques Doucet (founded in 1871), Rouff (founded 1884), Jeanne Paquin (founded in 1891), the Callot Soeurs (founded 1895 and operated by four sisters), Paul Poiret (founded in 1903), Louise Chéruit (founded 1906), Madeleine Vionnet (founded in 1912), House of Patou by Jean Patou (founded in 1919).

The fashion of the 1910s was still very similar to the 1900s -- with a puffy chest, a small waist, and long dresses/skirts.

The fashion was overall still very petite and romantic, with bright and dove colors as purple, pink and peach.

A lot of lace, details, and white to capture the pure and innocent fashion

Following the 1910 performance of “Scheherazade” by the Ballets Russes in Paris, a fashion mania for oriental styles was born.

Designs became asymmetrical. Preferred fabrics were satin, taffeta, chiffon, and lightweight silks, and cotton for the summer. Hemlines gradually rose and the female silhouette became straighter and flatter.

The Art Deco movement began to emerge at this time and its influence was evident in the designs of many couturiers of the time.

Simple felt hats, turbans, and clouds of tulle replaced the styles of headgear popular in the 1900s (decade).

It is also notable that the first real fashion shows were organized during this period in time by the first female couturier, Jeanne Paquin, who was also the second Parisian couturier to open foreign branches in London, Buenos Aires, and Madrid.

Two of the most influential fashion designers of the time were Jacques Doucet and Mariano Fortuny.

The French designer Jacques Doucet excelled in superimposing pastel colors and his elaborate gossamery dresses suggested the Impressionist shimmers of reflected light.

His distinguished customers never lost a taste for his fluid lines and flimsy, diaphanous materials.

While obeying imperatives that left little to the imagination of the couturier, Doucet was nonetheless a designer of immense taste and discrimination, a role many have tried since but rarely with Doucet’s level of success.

The extravagances of the Parisian couturiers came in a variety of shapes, but the most popular silhouette throughout the decade was the tunic over a long underskirt.

Early in the period, waistlines were high (just below the bust), echoing the Empire or Directoire styles of the early 19th century.

Full, hip-length “lampshade” tunics were worn over narrow, draped skirts.

By 1914, skirts were widest at the hips and very narrow at the ankle. These hobble skirts made long strides impossible.

Waistlines were loose and softly defined. They gradually dropped to near the natural waist by mid-decade, where they were to remain through the war years.

Tunics became longer and underskirts fuller and shorter. By 1916, women were wearing calf-length dresses.

The tailleur or tailored suit of matching jacket and skirt was worn in the city and for travel.

Jackets followed the lines of tunics, with raised, lightly defined waists. Fashionable women of means wore striking hats and fur stole or scarves with their tailleurs, and carried huge matching muffs.

Most coats were cocoon or kimono shaped, wide through the shoulders and narrower at the hem. Fur coats were popular.

Shoes had high, slightly curved heels. Shorter skirts put an emphasis on stockings, and gaiters were worn with streetwear in winter.

“Tango shoes” inspired by the dance craze had crisscrossing straps at the ankles that peeked out from draped and wrapped evening skirts.

In this article, you can flip through pictures of probably the world’s first street style photographs taken at Parisian races such as the Longchamp Racecourse Grand Prix on the banks of the Seine River.

(Photo credit: Agence Rol / Europeana Archives / Wikimedia Commons).

Updated on: September 11, 2021

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/french-fashion-old-street-style-photographs/

#France#French fashion#couture#haute couture#1910-1920#fashion houses#old street style photographs#Jeanne Paquin#Jacques Doucet#Mariano Fortuny#fashion designers#19th century#20th century#Parisian fashion houses#Longchamp Racecourse Grand Prix#Seine River

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Paul Poiret, the self proclaimed, King of Fashion.

The story of Paul Poiret is one of a working class son, who used his natural charisma to gain entry into some of the most exclusive ateliers in Paris and eventually became one of the twentieth century’s great couturiers. But it’s also a cautionary tale about a man who refused to adapt to changing times and styles after WWII due to his arrogance and finally ended penniless and bitter, his once-great label long forgotten.

Paul Poiret is born 20 April, 1879 as the son of a cloth merchant, in Paris’s working-class quartier of Les Halles. As a young boy he is sent to apprentice with an umbrella manufacturer, where he gathers “the scraps of silk left over after the umbrella patterns had been cut,” and uses them “to dress a little wooden doll that his sister . . . had given him.”

Still a teenager, Poiret takes his sketches to Madeleine Chéruit, a prominent dressmaker, who purchases a dozen from him. He continues to sell his drawings to major Parisian couture houses, till he is hired by Jacques Doucet, one of the capital’s most prominent couturiers. Poiret is only nineteen years old at the time. Beginning as a junior assistant, he is soon promoted to head of the tailoring department. His debut design for Doucet, a red wool cloak with a reverse gray crepe-de-chine lining, receives 400 orders from customers.

After two years of mandatory military service (1914-1918), he returns to Paris and is hired by House of Worth, once founded by Charles Worth, but now taken over by his sons. Instead of working on the luxurious eveningwear the House is famous for, Poiret is put in charge of the less glamorous and more practical items. Gaston Worth, the business manager, referred to Poiret’s division as the “Department of Fried Potatoes.” His ideas and designs are not appreciated by the clients. One of his “fried potatoes,” a cloak made from black wool and cut along straight lines like the kimono, proved too simple for one of Worth’s royal clients, the Russian princess Bariatinsky, who on seeing it cried, “What horror; with us, when there are low fellows who run after our sledges and annoy us, we have their heads cut off, and we put them in sacks just like that.”

At twenty-four (Poiret has a tireless self-confidence, despite his experiences at the House of Worth) he breaks out on his own and after borrowing funds from his mother, opens his own shop on Rue Auber. Its flashy window displays attract attention and he makes his name with the controversial kimono coat. Looking to both antique and regional dress types, most notably to the Greek chiton, the Japanese kimono, and the North African and Middle Eastern caftan, Poiret advocated fashions cut along straight lines and constructed of rectangles.

In 1905 Poiret marries childhood friend Denise, with whom he’ll go on to have five children. “She was extremely simple,” he later will say, “and all those who have admired her since I made her my wife would certainly not have chosen her in the state in which I found her.” Denise Poiret will eventually become his artistic director as well as muse, wearing his designs as they travel around Europe together and winning a reputation as a trendsetter. (A fact her husband will later take credit for: “I had a designer’s eye, and I saw her hidden graces.”)

Years later, Denise Poiret is described as:

“the woman who had inspired the feminine silhouette of this century”

Poiret’s process of design through draping is the source of fashion’s modern forms. It introduced clothing that hung from the shoulders and facilitated a multiplicity of possibilities. Poiret exploited its fullest potential by launching, in quick succession, a series of designs that were startling in their simplicity and originality. From 1906 to 1911, he presented garments that promoted a high-waisted Directoire Revival silhouette. Different versions appeared in two limited-edition albums, Paul Iribe’s Les robes de Paul Poiret (1908) and Georges Lepape’s Les choses de Paul Poiret (1911).

Every decade has its fortune-teller, a designer who, above all others, is able to divine and define the desires of women. In the 1910s, this oracle of fashion was Paul Poiret, known in America as “The King of Fashion.” In Paris, he was simply Le Magnifique, after Süleyman the Magnificent, a suitable nickname for a couturier who, alongside the great influence of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, employed the language of orientalism to develop the romantic and theatrical possibilities of clothing. Like his artistic confrere Léon Bakst, Poiret’s exoticized tendencies were expressed through his use of vivid color coordinations and mysterious silhouettes such as his iconic “lampshade” tunic, “Kymono” coat and his “harem” trousers, or pantaloons. However, these orientalist fantasies (or, rather, fantasies of the Orient) have served to decline from Poiret’s more enduring innovations, namely his technical and marketing achievements. Poiret effectively established the canon of modern dress and developed the blueprint of the modern fashion industry. Such was his vision that Poiret not only changed the course of costume history but also steered it in the direction of modern design history..

Anecdote: Lady Asquith, wife of British Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, invites Poiret to show gowns at 10 Downing Street. Stories of half-nude models running amok at the prime minister’s residence cause a furor in the press and the resulting scandal almost forces Asquith to resign...

Paul Poiret on Tour with his Collections: Historians consider Poiret the first haute couturier to have taken his collections on tour in Europe and America. He visited Berlin in 1910, and the next year went on a six-week trek (in a chauffeured car) to Moscow, St. Petersburg, Warsaw, Vienna, Frankfurt, Berlin, and Bucharest—where he was arrested for not having a proper permit. Poiret’s arrival in New York in 1913 was prefaced by an open letter from John Cardinal Farley warning against the temptations offered by “the demon fashion.”

https://agnautacouture.com/2014/04/06/paul-poiret-le-magnifique-part-2/

https://agnautacouture.com/2014/05/11/paul-poiret-pictures-of-garments-accessoires-part-3/".

> Philip Pradere > Vintage Fashion uncovered

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Poiret: The King of Fashion

“I am an artist, not a dressmaker.” - Paul Poiret

Born from very humble origins, Paul Poiret became one of the most influential French fashion designers of the early 20th century. During the 1910s, In the United States Poiret was called “The King of Fashion,” while the French referred to him as “Le Magnifique.” During his career, Paul Poiret both “established the canon of modern dress and developed the blueprint of the modern fashion industry”(1).

Poiret’s Early Career

Paul Poiret was born on April 10, 1879 in Les Halles, Paris, France (2) into the bourgeois Parisian family of Auguste Poiret, a cloth merchant. Young Paul received his education at a Roman Catholic school.(3) When young Paul’s education was complete, his father apprenticed him to an umbrella maker, however Paul found the work unsatisfactory.(2,3) On his own time, he worked on fashion designs and enjoyed making doll clothes out of cloth scraps from the umbrella shop.

Portrait of artist and designer Paul Poiret (c. 1913). Photographer unknown. Image source

“Poiret’s route into couture followed the common practice [at the time] of shopping around one’s drawings of original fashion designs. His efforts were rewarded in 1898, when the couturière Madeleine Chéruit bought twelve of his designs”(1). That same year designer, “Jacques Doucet, one of the most prominent couturiers in Paris”(1) hired Paul to work for him.(1) The first item Poiret designed for Doucet was “a simple red cape with gray lining and revers. (3)” The cloak sold over 400 copies. Within 4 years, at the age of 23, Poiret headed Doucet’s tailoring department.(3) During that time in Paris, a sure way to get your designs noticed was through the theater and Poiret’s breakthrough was a mantle of “black tulle over black taffeta painted with large-scale iris”(3) that he designed for “ the actress Réjane in a play called Zaza”(1). Poiret found his dramatic designs were well suited for the theater. He would continue to design theatrical costumes throughout his career.

Poiret Joins the House of Worth

After completing his military service in 1901, Poiret returned to Paris and became an assistant designer at “Worth, the top couture house”(3). There Poiret was assigned to design simple, serviceable clothes -- “what Jean Worth (grandson of the founder) called the ‘fried potatoes,’ meaning the side dish to Worth's main course of lavish evening and reception gowns…. For this Poiret felt looked down upon by his fellow designers, although his designs were commercial successes”(3). Adding to Poiret’s frustrations, Worth’s conservative clients found his clean, elegant designs as too modern, so in 1903 Poiret struck out and founded his own house.

“In 1905 [Poiret] married Denise Boulet, the daughter of a textile manufacturer, [her] waiflike figure and nonconventional looks would change the way he designed”(3). Boulet would serve as both Poiret’s model and muse. The couple would have five children together (2).

Paul Iribe Illustrates Poiret’s Fashions

The following year he would move his shop into 37, rue Pasquier.(3) In 1908 Poiret published a “limited edition deluxe album” of designs illustrated by artist Paul Iribe. Most fashion illustration of the time which showed models in traditional posed “against a muted ground, vaguely landscape or interior in feeling”(3); in contrast Iribe composed models in Poiret’s brightly colored fashions against black and white line drawn backgrounds, a technique which made the fashions pop from the page. Iribe’s work influenced fashion illustration and photograph for decades, and helped sensationalize Poiret’s designs.(3) The album also shows Poiret’s “attempt to cement the relationship between art and fashion”(1). By 1909 Poiret’s business had become so successful ,he moved to grander quarters at 9 avenue d'Antin.(3)

Paul Iribe, Illustration from Les Robes de Paul Poiret, p. 17, (1908). Image source.

Poiret’s Eastern Influences

Poiret found much of his inspiration in the past “notably to the Greek chiton, the Japanese kimono, and the North African and Middle Eastern caftan, Poiret advocated fashions cut along straight lines and constructed of rectangles”(1). His designs began to free women from the petticoat and later from the corset. In 1910, when a Ballet Russes production of Scheherazade was performed in Paris, Leon Bakst’s costumes and sets shook up the design world. “Whether inspired or reinforced by Bakst, certain near-Eastern effects: the softly ballooning legs, turbans, and the surplice neckline and tunic effect became Poiret signatures”(3). Poiret’s designs “shifted the emphasis away from the skills of tailoring to those based on the skills of draping. It was a radical departure from the couture traditions of the nineteenth century, which, like menswear…relied on…the precision of pattern making”(1).

Paul Poiret, Eastern influenced costume with harem pants, (1911). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum. Image source.

Poiret’s Jupe-Culotte

In 1911 Poiret asked artist George Lepape, who had recently worked on a second album of Poiret’s designs, to develop an idea for a new design. Lepape and his wife created a sketch that would inspire one of Poiret’s most radical designs – the Jupe-Culotte. This garment consisted of a long tunic worn over pants gathered at the cuffs. While the design was revolutionary, in reality, it “was wildly unmodern, requiring the help of a maid to get in and out of and utterly impractical for anything other than looking au courant” (3). Poiret would continue to work on versions of the Jupe-Culotte. Some of those designs would eventually inspire the modern pantsuit.

Poiret’s Marketing Flair

Poiret’s genius as a designer was almost matched by his talent in marketing. During his time there were no runway shows, so Poiret toured Europe showing off his work. He also loved throwing parties where guests would be wearing his designs. “On 24 June 1911 the renowned 1,002-night ball was held in the avenue d'Antin garden featuring Paul Poiret as sultan and Denise Poiret as the sultan's favorite”(3). Madame Poiret was outfitted in her husband’s latest version of the Jupe-Culotte. Guests received invitations that instructed them to dress in Persian costume.(3)

Paul Poiret, Tunic with Jupe-Culotte (1913). Collection of FIDMuseum. Image Source.

Les École Martine

In 1911 Poiret founded Les École Martine named after his second daughter. The school provided young working class Parisian women with design instruction and employment. “Poiret admitted to being inspired by his 1910 visit to the Wiener Werkstätte”(3). Through Les École Martine Poiret established his home décor line. Among the home furnishings his students designed were “richly colored gouache floral designs, created as samples for carpets in the early 1920s…. Poiret was not only ahead of his time in envisaging a brand universe in which furniture and fabrics were an integral part”(4).

Read Part Two of “Paul Poiret: King of Fashion.”

References

Koda, H. & Bolton, A., (September 2008). Paul Poiret (1879–1944). https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/poir/hd_poir.htm

Wikipedia, (30 April, 2022). Paul Poiret. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Poiret

Milbank, C.R., (2022). Paul Poiret. https://fashion-history.lovetoknow.com/fashion-clothing-industry/fashion-designers/paul-poiret

Menkes, S., (26 April, 2005). Liberty Belle: Poiret's Modernist Vision. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/26/style/liberty-belle-poirets-modernist-vision.html

Maison Schiaparelli, (n.d). Shocking life: A Homage to the Famous Firsts of a Legendary Couturiee. https://www.schiaparelli.com/en/21-place-vendome/the-life-of-elsa/

For Further Reading

Deslandres, Yvonne, with Dorothée Lalanne. Poiret Paul Poiret 1879-1944. New York: Rizzoli International, 1987.

Paul Poiret. King of Fashion: The Autobiography of Paul Poiret. Philadelphia and London: J. B. Lippincott, 1931

White, Palmer. Poiret. New York: Clarkson N. Potter Inc., 1973.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, so I figured out why my tumblr wasn’t showing up for anybody, and it said I had to first make a few posts before it would show up, so I decided to leave the good stuff for when people can actually see it haha. For now, let me share a little bit about my trip to a historical fashion museum back in September of last year. Oh yes, the day I fell in love with the Edwardian era. I saw this dress in particular, and it took my breath away. The details! How much actual talent went into making this piece.

It’s a 1905 walking/afternoon dress if I remember correctly, and it was made by Madeleine Chéruit in Paris. That pigeon breast silhouette - beautiful. Those sleeves? Damn. It’s the one thing that I almost desperately want to recreate but I don’t have the skills (yet?). One day I might attempt it. Fingers crossed! 🤞🏼

Another gown that deeply fascinated me was the 1830s one. For one, because I am generally really fascinated by change and extravagance. Now, the 1830s were a follow-up to the Jane-Austen-Regency era, and people were sick of being rather plain (even though the regency period wasn’t just plain white dresses, contrary to popular belief!). Either way, women wanted poofy dresses back, and they got them.

I would dare to say that this is a rather plain specimen for that era (the sleeves could get HUGE) but still gorgeous. It must be an early 1830s piece as the sleeves tended to be poofier towards the bottom approaching the end of the decade. It would have been worn on top of several layers of petticoats, some of which were stiffened with horse hair to get this stiff-looking shape. I attempted a dress inspired by the 1830s and 1850s to wear for Christmas last year, using no pattern and eyeballing it but surprisingly, it fits? But I made it in a rush so I would finish it on time, so I didn’t fell the seams on the inside and it looks pretty rough to say the least. On the outside, however, it’s totally fine. I’ll talk about making this dress in a seperate post, so I won’t spoil with any pictures for now.

Anyways, speaking of extravagant eras, here’s the most out there, in-your-face kinda dress. A Robe à la Françasise from the 1740s.

(that pic is sort of really bad quality and I apologize but it was pretty far in the back in a glass case with around 20 other dresses and I had to zoom in a lot)

I wouldn’t say that I particularly like these types of dresses, as in I wouldn’t choose to make one myself, but I am very intrigued by the sheer width of that thing. I know from my own experience with 18th century garments that panniers were actually very easy to squish together, so moving around maybe wouldn’t have been as big of a problem as some might think nowadays, but I can’t imagine it being as comfortable or practical as a regular sized gown of that time. But obviously, it wasn’t about comfort or practicality, but simply about rich people wanting to show off. The more fabric you “wasted” on a dress, the wealthier you were. It’s that simple. 🤷🏻♀️

#fashion history#historical fashion#fashion#fashion museum#rococo#victorian#edwardian#victorian fashion#edwardian fashion#rococo fashion

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Women in Design “For too long their work has been lost in the mists of time and therefore gone unacknowledged. Our book’s central message to women following in the wake of these remarkable female design pioneers is: ‘Yes, you can, now go and do it!’” - Charlotte Fiell. Aino Aalto, Anni Albers, Laura Ashley, Gae Aulenti, Lina Bo Bardi. Cini Boeri, Irma Boom, Marianne Brandt, Vivianna Torun Bülow-Hübe, Margaret Calvert, Louise Campbell, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, Gabrielle 'Coco' Chanel, Louise ‘Madeleine’ Chéruit, Kim Colin (Industrial Facility), Collier Campbell, Matali Crasset, Lucienne Day, Carlotta De Bevilacqua, Elsie De Wolfe, Sonia Delaunay, Elizabeth Diller, Nanna Ditzel, Marion Dorn, Nipa Doshi, Dorothy Draper, Clara Driscoll, Ray Eames, Estrid Ericssson, Vuokko Eskolin-Nurmesniemi, Front, Georgina ‘Georgie’ Gaskin, GM’s ‘Damsels of Design’, Sophie Gimbel, Glasgow Girls, Lonneke Gordijn (Studio Drift), Eileen Gray, April Grieman, Maija Grotell, Zaha Hadid, Katharine Hamnett, Ineke Hans, Edith Head, Margaret Howell, Maija Isola, Grete Jalk, Betty Joel, Hella Jongerius, Ilonka Karasz, Susan Kare, Rei Kawakubo, Florence Knoll, Florence Koehler, Belle Kogan, Jeanne Lanvin, Estelle Laverne, Amanda Levete, Shelia Levrant de Bretteville, ’Lucile’ Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, Elaine Lustig Cohen, Märta Måås-Fjetterström, Greta Magnusson-Grossman, Cecilie Manz, Enid Marx, Bonnie MacLean, Grethe Meyer, Rosita Missoni, May Morris, Marie Neurath, Neri Oxman, Maria Pergay, Charlotte Perriand, Miuccia Prada, Mary Quant, Ingegerd Råman, Ruth Reeves, Lilly Reich, Lucie Rie, Astrid Sampe, Paula Scher, Elsa Schiaparelli, Margarete ‘Grete’ Schütte-Lihotzky, Denise Scott Brown, Inga Sempé, Alma Siedhoff-Buscher, Alison Smithson, Sylvia Stave, Varava Stepanova, Nanny Still McKinney, Gunta Stözl, Marianne Straub, Anne Swainson, Faye Toogood, Nynke Tynagel (Studio Job), Patricia Urquiola, Valentina Kulagina, Mimi Vandermolen, Lella Vignelli, Nanda Vigo, Vivienne Westwood, Yiqing Yin, Eva Zeisel, Nika Zupanc . ‘Women in Design: From Aino Aalto to Eva Zeisel’ by Charlotte Fiell, Clementine Fiell, published by ’Laurence King Publishing’. #neonurchin #neonurchinblog https://www.instagram.com/p/B7-yVKIA-t0/?igshid=zeffnlqo6xud

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Female Designers who changed fashion

Coco Chanel

Donatella Versace

Madeleine Chéruit

Madame Gres

Diane Von Furstenburg

Carolina Herrera

Donna Karan

Madeleine Voinnet

Claire McCardell

Stella McCartney

#stellamccartney#claire mccardell#madeleinevoinnet#donnakaran#carolinaherrera#dvf#dianevonfurstenberg#madame grès#madeleinecheruit#versace#donatella versace#chanel#coco chanel#fashion#fashionblog#fashiondesigners#fashionweek#fashionicon#fashionidols#fashiongoals#highend#highenddesigners#femaledesigners#feminism#girlssupportinggirls#womensfashion#womenswear#womenstyle#girllove#whattowear

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of Madame Helleu with a Parasol (c.1899). Paul-César Helleu (French, 1859-1927). Oil on canvas.

In this dreamy portrait Madame Helleu is shown from an angle that lends her a certain grandeur, as if her silhouette were dominating the heavens. The brushwork is rich and intense. The milky white of the clouds and the lady’s clothes – she is wearing a stylish dress designed by Madeleine Chéruit – are brought to life with golden tints, and stand out against the soft blue ground with crystal sharpness.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louise Chéruit - House of Chéruit

Louise Chéruit - House of Chéruit #louisechéruit #chéruit #houseofchéruit #cheruit #perfettamentechic #felicementechic #creatoredellostile #creatoredellamoda

Madame Louise Chéruit, nata Louise Lemaire, spesso erroneamente chiamata Madameine Chéruit, fu tra le principali couturier della sua generazione e una delle prime donne a controllare una grande casa di moda francese. Il suo salone operato in Place Vendôme a Parigi, sotto il nome di Chéruit dal 1906 al 1935. Chéruit è ricordata oggi come il soggetto di una serie di ritratti di Paul César Helleu,…

View On WordPress

#"Madeleine" Chéruit - Louise Lemaire#21#Belle Époche#Boulanger#Carnavalet Museum#Chéruit#EDWARD STEICHEN#Elsa Schiaparelli#Evelyn Waugh#Evelyn Waugh&039;s Vile Bodies#Flapper Dress#House of Chéruit#Huet & Chéruit Srs.#Jeanne Eagels#La Gazette du Bon Ton#La House of Chéruit#Louise#Louise Chéruit#Louise Lemaire#Lucien Vogel#Madame Chéruit#Madame Louise Chéruit#Madameine Chéruit#Madames Wormser#Madeleine#Marcel Proust#Marie Huet#Marion Morehouse#Parigi#Paul César Helleu

0 notes

Photo

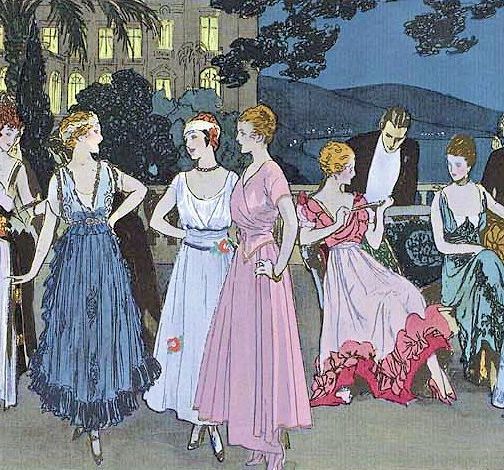

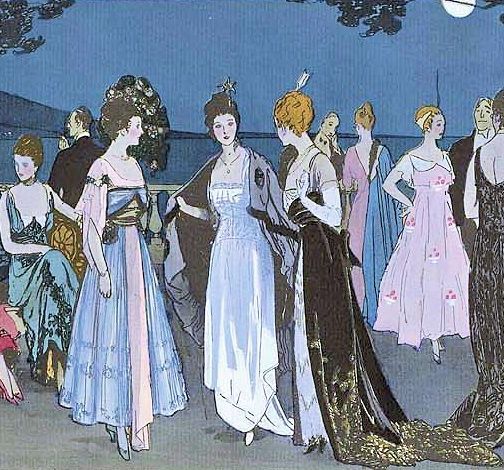

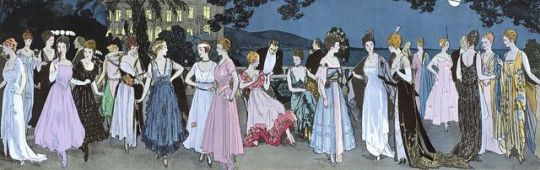

Louis Strimpl, detail, La Cote d'Azur ou Une fête sur la terrasse (The Cote d'Azur or A party on the terrace), La Gazette du Bon Ton, Summer 1915.

Louis Strimpl Illustrating design by Georges Dœuillet, House of Beer, Madeleine Chéruit, House of Callot Soeurs, Mme. Jeanne Paquin, House of Worth, Jeanne Lanvin, Jacques Doucet, Martial & Armand, Jenny Sacerdote, known as Madame Jenny and House of Premet.

#louis strimpl#1915#cote d'azur#detail#La Gazette du Bon Ton#gazette du bon ton#summer 1915#summer fashion#1910s summer#1910s summer fashion#strimpl#georges dœuillet#house of beer#madeleine chéruit#house of callot soeurs#callot soeurs#jeanne paquin#house of worth#jeanne lanvin#jacques doucet#martial & armand#jenny sacerdote#madame jenny#house of premet#1910s fashion#1910s fashion illustration#illustration#fashion illustration#vintage illustration#vintage fashion illustration

674 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Suit, Madeleine Chéruit (French, 1906–1935) for Raudnitz and Co. - Huet and Chéruit (French): ca. 1905, French, wool, silk, cotton, linen. Marking: [label] (in back of jacket lining) "Huet & Cheruit, Anc.ne Mon. Raudnitz & Co., 21 Place Vendome, Paris"

0 notes

Photo

Edward Steichen (American, born Luxembourg; 1879–1973)

Marion Morehouse Modeling a Chéruit Gown in Condé Nast’s Park Avenue New York Apartment

Published: American Vogue, May 1, 1927

Gelatin silver print, 1927

Christie’s, New York

#Condé Nast#Edward Steichen#Madeleine Chéruit#Marion Morehouse#Mrs. E. E. Cummings#Park Avenue#Vogue#chic#dresses#fashion magazines#fashion photography#flappers#haute couture#high style#interiors#jet beads#models#patterns#sofas#Ain't She Grand?#Chéruit#American photographers#American artists#glamour#American publishers#shimmering#textiles

16 notes

·

View notes