#mbuti pygmies

Text

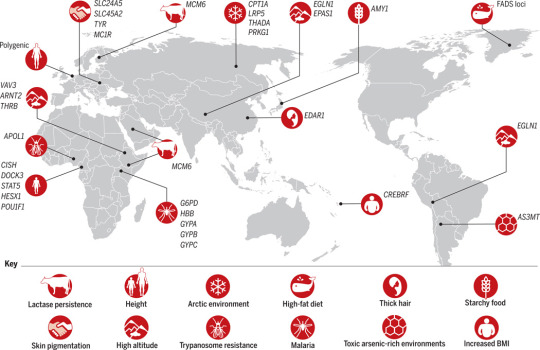

Recent evolutionary adaptations to the environment in human populations, from Going global by adapting local: A review of recent human adaptation (Fan et al., 2016). The icons show the type of adaptation recorded in various parts of the world, and the acronyms besides (e.g. EDAR1) are the names of the involved genes. Also see Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations (Sabeti et al., 2009), Population Genomics of Human Adaptation (Lachance & Tishkoff, 2013).

Some examples are:

Lactase persistence in Europe, Near East, and East Africa, allowing the digestion of milk in adult age (by default, the lactase required to digest milk sugar would only be produced by infants; this was just a matter of removing a timed switch).

Similarly, greater production of amylase, which breaks down starch, is reported in Europe and Japan (diet based on farmed grains) and among the Hadza of Tanzania (diet based on starchy tubers).

Improved conversion of saturated into unsaturated fatty acids in the Arctic Inuit peoples. This makes it easier to live on a diet of fish and marine mammals in an environment where plant food is scarce.

Smaller stature ("defined as an average height of <150 cm in adult males") in the "pygmy" peoples (Aka and Mbuti) of Central Africa, and other hunter-gatherer peoples in equatorial Asia and South America. This helps shed heat in a hot humid climate where sweat does not evaporate.

More efficient fat synthesis in the Samoa, helping with energy storage at the price of more risk of obesity or diabetes with a richer modern diet.

Improved resistence to malaria, sleeping sickness (trypanosome), and Lassa fever in Subsaharan Africa. Fighting off against parasites is especially difficult (since unlike the inorganic environment, parasites also evolve), so this resistence often comes at a cost, such as anhemia, but is still a great advantage on net. Some improved resistence to arsenic poisoning is noted in an Argentinian population.

Denser red blood cells on the Andean, Ethiopian, and Tibetan highlands, to carry more oxygen which is scarcer at high altitude. I recall from elsewhere that this might increase the risk of thrombosis or strokes due to obstructed blood vessels.

Less melanin (which blocks UV light) and therefore lighter skin color in Eurasia. Melanin shields skin cells from damage due to UV radiations, but some UV light is necessary for the synthesis of vitamin D.

A change in the gene EDAR1, resulting in denser head hair, slightly different tooth shape, and fewer sweat glands (all skin annexes), appears strongly selected for in East Asia, but as far as I can find the advantage of this mutation is still unknown.

From another article (Ilardo et al., 2018): the Sama Bajau people of Indonesia, who have a long tradition of free-diving in apnea, seem to have developed larger spleen to store more oxygenated blood during dives.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

(for context, the Mbuti are hunter-gatherer pygmies in the congo rainforest. they live in the forest itself, while the "villagers", bantu people, farm in spaces cleared from the forest, they have a complex interdependence)

Some Mbuti have learned to use matches, when available, and a few know of the fire drill from contact with their village neighbors. There is absolutely no indigenous method of making fire, however, and it is a point of no small importance to their social life that each household maintains its own hearth. Embers from this hearth are carried, usually by the woman, wrapped in fire-resisant leaves, during the hunt or while on the trail. At each new camp site, the family hearths are kindled from embers of the old family hearths, preserving a distinct sense of continuity. Whenever a communal hearth is required, as for the molimo, communal participation is accentuated by the compulsory contribution of embers from each family hearth. Whereas matches are rarely used, becoming quickly damp and useless, even if available, they are never used for kindling family or communal hearths, but only for such relatively mundane purposes as lighting a pipe or cigarette.

Wayward Servants, the two worlds of the Mbuti, Turnbull

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minimal differentiation of sex roles also exists among the Mbuti, who form the largest single group of pygmy hunters and gatherers in Africa. Their habitat and their heaven is the Ituri Forest.

The Mbuti have no creation myth per se. The forest is their godhead, and different individuals address it as "father," "mother," "lover," and/or "friend." The Mbuti say that the forest is everything: the provider of food, shelter, warmth, clothing, and affection. Each person and animal is endowed with some spiritual power that "derives from a single source whose physical manifestation is the forest itself." Disembodied spirits deriving from this same source of power are also believed to inhabit the forest; they are considered to be independent manifestations of the forest. The forest lives for the Mbuti. It is both natural and supernatural, something that is depended upon, respected, trusted, obeyed, and loved.

The forest is a good provider. At all times of the year men and women can gather an abundant supply of mushrooms, roots, berries, nuts, herbs, fruits, and leafy vegetables. The forest also provides animal food. There is little division of labor by sex. The hunt is frequently a joint effort. A man is not ashamed to pick mushrooms and nuts if he finds them or to wash and clean a baby.

In general, leadership is minimal and there is no attempt to control or dominate either the geographical or human environment. Decision making is by common consent: Men and women have equal say because hunting and gathering are both important to the economy. The forest is the ultimate authority. It expresses its feelings through storms, falling trees, poor hunting—all of which are taken as signs of its displeasure. But often the forest remains silent, and this is when the people must sound out its feelings through discussion. Diversity of opinion may be expressed, but prolonged disagreement is considered to be "noise" and offensive to the forest. Certain individuals may be recognized as having the right and the ability to interpret the pleasure of the forest. In this sense there is individual authority, which simply means effective participation in discussions. The three major areas for discussion are economic, ritual, and legal matters having to do with dispute settlement. Participation in discussions is evenly divided between the sexes and among all adult age levels.

-Peggy Reeves Sanday, Female Power and Male Dominance: On the Origins of Sexual Inequality

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you were put in charge of fleshing out a non-racist version of the Pygmies in Warhammer, and were told you could give them the central jungle of the Southlands as their territory, as Games Workshop wished to seperate them from the Lizardmen in Lustria, how would you flesh out their culture to be similar to both Mbuti Pygmies and Zulus, whilst not being offensive? Also, what sort of character would be their Big Hero, like Sigmar for Humans or Grimgor for Greenskins?

If I wanted to do Southlands human stuff I would probably leave the pygmies in the bin where they belong. The actual Bambuti people would be best respected by not being in a Games Workshop property.

I think you could totally have a cool West/Central-African themed faction. Lightly armored. Maybe drawing upon dark magic but not necessarily being evil themselves. Golden warriors. Elite scouts. Witch doctors. I’m all in favor of cultural diversity in Warhammer, you just have to be a little bit careful and focus more on making things that look badass rather than offensive.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

B haplogroup M60 mutation, 60-65Kyr in Central Africa , clades B1, B1a, B2, B2a and many more.

svdsmw

read below, important

BT, origin:

70-80Kyr in North West or central West Africa

mutation:

M42

BT has not been found in any current population. No male has been shown to carry BT (BT*).

note

In Y haplogroups, paragroups are represented by an asterisk " * ", placed after the main haplogroup nomenclature. Paragroups contain the mutations which define the parent haplogroup, but they do not have any further (known) unique markers. Without these unique markers, they do not form truly independent sub-clades.

B haplogroup, origin:

60-65Kyr in Central Africa

mutation:

M60

current populations:

B is localized among the Baka and Mbuti peoples of the tropical forests of West-Central Africa and the Hadza of Tanzania. 2.3% of African-American males carry B.

B is the second oldest and a very diverse Y haplogroup, but it is scattered widely and thinly in Africa, suggesting that the carriers of B were displaced by later (5Kyr) flows of people and events. A competing hypothesis runs that the sub-Saharan population dwindled (to ~2K persons at 35Kyr) and that there were few remaining carriers of B around to have been displaced by even much later migrations of (Bantu) people.

Some of the sub-clades of B are:

B1

mutation: M236

current population: southern Cameroon (Bamileke 4%)

B1a

mutation: M146

current population: Burkina Faso (Mossi 2%)

B2

mutation: M182

current populations: Congo (Mbuti), southern Cameroon (Bakola), Namibia (Dama) and Central African Republic (Biaka "pygmy")

B2a

mutation: M150

current populations: Congo (Mbuti 8%), Cameroon (Tupuri 11%), Mali (Dogon 6%) and Kenya (Kikuyu and Kamba 2%)

B2a1

mutation: M218

current population: northern Cameroon

B2a1a

mutation: M109

current populations: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Sudan, Egypt (2%), Southern Iran (3%), African-Americans (1.5%), Pakistan and India

B2b

mutation: M112

current populations: Central African Republic (Baka "pygmy" 67%), Tanzania (Hadza 51%), Congo (Mbuti 43%), Namibia (San 31%)

B2b4

mutation: P7

current populations: Central African Republic (Baka 67% and Biaka 45%) and Congo (Mbuti 21%)

B2b4b

mutation: MSY2.1

current populations: Central African Republic (Biaka 20%)

CT haplogroup, origin:

68.5Kyr in East Africa

mutation:

M168

CT is often referred to as the "Eurasian Adam" - the most recent common ancestor of all non-African males. This hypothetical male is conjectured to have existed in Africa - immediately prior to the exodus of Anatomically Modern Humans from Africa. CT is the considered the common ancestral lineage of most men living today - though no male has been shown to carry CT (CT*).

The mutations M168, P9.1 and M294 have been found in all males tested - with the exception of those exclusively carrying A and B (sub-Saharan) haplogroups.

note

Paragroup (CT*) contains the mutations which define the parent haplogroup (M168, P9.1 and M294), but it does not have any further (known) unique markers.

0 notes

Text

The First One Now Will Later Be Last…

Within the labyrinth of language, where meanings often intermingle, two words—"indigent" and "indigenous"—stand as a testament to the complexity and irony of expression. Despite their disparate origins and definitions, an unintended bridge forms between them, highlighting the unforgiving path that many indigenous communities have tread. This linguistic anomaly draws attention to the poignant reality that historical injustices and systemic inequalities have tragically transformed "indigenous" peoples into the "indigent."

The word "indigenous" comes from the Latin indigena, meaning "born in a country" or "native." It is formed from the prefix "in-" (meaning "in" or "within") and "dignus" (meaning "worthy" or "appropriate"). Over time, this term has evolved to refer to people, cultures, or things that are native to a particular region, indicating a deep historical connection to that place.

Conversely, "indigent" is derived from the Latin indigens, meaning "needy" or "lacking." It is formed from the prefix "in-" (meaning "not" or "without") and "egens" (meaning "needy" or "requiring"). The root egens is derived from egere, which means "to lack" or "to need." Thus, "indigent" describes individuals or groups who are lacking financial resources or living in poverty.

While these terms possess distinct roots and meanings, their phonetic similarity can sometimes lead to confusion or unintended associations. This phenomenon, known as "false cognates," typically refers to words in different languages that appear similar but have different meanings. Although "indigenous" and "indigent" are not false cognates in the traditional sense, they illustrate how language can sometimes create unexpected connections between unrelated concepts.

Unfortunately, many indigenous communities worldwide have become indigent due to historical manipulation, greed, and systemic oppression. The sad reality is that many Native American communities face significant persecutions leading to economic hardship and poverty. Historical injustices—such as forced displacement from ancestral lands, cultural suppression, and systemic discrimination—have contributed to their marginalized status within society.

And they was here first.

The plight of indigenous Australians, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, continues to expose socioeconomic disparities bestowed upon native peoples. Historical colonization, land dispossession and ongoing systemic issues have contributed to their indigent status.

Similarly, the Māori people in New Zealand have dealt with land confiscation, loss of cultural heritage, and socioeconomic disparities that have led to their indigent status in certain areas. In Canada, many First Nations communities have experienced intergenerational trauma from the legacy of residential schools, loss of land, and limited access to resources, leading to high poverty rates and other socioeconomic challenges similar to those faced by Native Americans.

In Africa, groups such as the Bushmen, Pygmies, and Maasai exemplify this struggle. The San people, known as Bushmen or Basarwa, inhabit regions in southern Africa and are renowned for their intricate knowledge of the land and their traditional hunting and gathering lifestyle. Pygmy groups like the Aka, Baka, and Mbuti are found in central Africa and have faced similar socio-economic challenges. The Maasai, a semi-nomadic pastoralist community in Kenya and Tanzania, are recognized for their distinct culture yet also contend with ongoing hardships.

In the somber aftermath of exploration, conquest, and colonization, the lives of many indigenous communities have been shaped by forces beyond their control. This linguistic interplay between "indigent" and "indigenous" reflects an uncomfortable truth: the proud inheritors of ancient traditions, custodians of ancestral lands, have found themselves ensnared and enslaved by poverty and marginalization.

And it ain't no accident

It's what we call manifest destiny.

The connection between "indigent" and "indigenous" serves as a powerful reminder of the systemic inequalities that persist today. Addressing these cruelties requires not only recognition of the linguistic and historical context but also a commitment to justice and equality. As we engage with these terms, we must consider our roles in perpetuating or dismantling these injustices.

To move forward, society must prioritize policies that empower indigenous communities, ensuring their voices are heard and their rights respected. This includes advocacy for land rights, access to education, and economic opportunities. By fostering a deeper understanding of these issues and striving for tangible change, we can work toward a future where the proud heritage of indigenous peoples is celebrated rather than overshadowed by the specter of indigence. Ultimately, we must recognize that the fight for justice and equity is ongoing and that we all have a part to play in shaping a more inclusive world.

Or we just keep building walls

0 notes

Text

Mythic Creatures by Region & Culture

Part 9: Africa

Here is the overview of global creatures.

Cross-Cultural (across multiple but not all cultures)

Amadlozi of the Nguni people in South Africa; Anansi is Akan (which includes the Agona, Akuapem, Akwamu, Akyem, Anyi, Ashanti (!!!!!!!), Baoulé, Bono, Chakosi, Fante, Kwahu, Sefwi, Wassa, Ahanta, and Nzema) also found in African American lore; Asanbosam is Akan (which includes the Agona, Akuapem, Akwamu, Akyem, Anyi, Ashanti (!!!!!!!), Baoulé, Bono, Chakosi, Fante, Kwahu, Sefwi, Wassa, Ahanta, and Nzema) also found in Jamaican slave lore; Death; Jengu various peoples in Cameroon; Madam Koi Koi; Mami Wata; Mazomba; Mbombo; Mbuti Mythic Creatures; Mbwiri; Nandi Bear; Ninki Nanka; Nyami Nyami; Obambou; Obia also name for a creature in Latin American folklore (Garifuna of Bay Islands, Honduras); Ogun; Oshun; Shetani; Somali myth; Werehyena; Yumboes Wolof; Zār; Zuhri

allegedly African

Aegipan; Amphisbaena, in Greek myth, Perseus flies over Libya with head of Medusa…blood creates Amphisbaene; Catoblepas; Cerastes; Crocotta; Dingonek East Africa 1907-1918; Ethiopian pegasus; Forest Bull; Gold-digging ant; Griffon; Hypnalis; Leontophone; Lycaon; Macrobian; Pard; Pygmies; Rompo; Scitalis; Seps; Struthopodes maybe??; Syrbotae; Tarand; Theow; Wild Man, Wild Woman ; Wild Men, Wild Women; Yale

Angola

Kishi

Ashanti

Anansi; Asanbosam; Obayifo

Benin

Aido Hwedo, also in Haiti

Canary Islands (Guanches)

Guayota; Maxios; Tibicena; Witches of Anaga

Congo

Abada; Bunzi; Eloko ; Biloko; Jengu also known in Cameroon, called Bisimi with the Bakongo; Mfinda; Nkisi; Nkondi; Simbi

Dahomey

Aziza

Dogon

Nommo

Ethiopia

in the Quran, an Aksumite (Ethiopian) siege is averted by birds dropping stones: Ababil; Buda (Ethiopia & Eritrea, were-hyena & evil eye); Ethiopian superstition; Holawaka (Oromo, Ethiopia);

Igbo

Ibo loa also Haiti

Nkomi & Bakalai, Gabon

Koolakamba

Ghana

Abonsam, also Gold Coast; Adze, possessing "vampire" who stalks prey as firefly among the Ewe of Togo and Ghana

Gold Coast

Abonsam, also in Ghana

Kalenjin, Kenya

Kalenjin Mythic Creatures

Khoikhoi

Aigamuxa

Lingala

Mokele-mbembe

Lugbara (Congo to Sudan)

Adroanzi, "angels", benevolent children of the god Androa, but if you turn around to look at them you die

Malagasy

Kalanoro; Vazimba; Yateveo (Plant) alleged

Mozambique

Agogwe sighted by 2 Europeans in 1926-1927 but existed prior as a word & creature in indigenous oral traditions

Songhay

Hira; Zin Kibaru

Sotho, South Africa

Kammapa; Monyohe

South African Folktales

Grootslang

Tswana

Matsieng

Uganda

Jok (among Acholi of Uganda and South Sudan); Lukwata (Baganda of Uganda);

West Africa

Adze, possessing "vampire" who stalks prey as firefly among the Ewe of Togo and Ghana; Ekpo Nka-Owo (Ibibio, Southern Nigeria); Wereleopard; Zin;

Xhosa

Amafufunyana (possession, schizophrenia); Uhlakanyana

Yoruba

Abiku; Egbere; Emere; Shango; Yemọja

Zambia

Ilomba among the Lozi people

Zanzibar

Popobawa

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe Bird

Zulu

Inkanyamba; Isitwalangcengce; Lightning Bird; Tikoloshe; Uhlakanyana; Umamba; Usiququmadevu; Zulu religion

Ancient Egypt

Aani; Abezethibou, Testament of Solomon, acted during Book of Moses in Egypt; Abtu; Abyzou; Akhekh; Ammit; Anubis; Apophis; Ba (personality); Bennu; Griffon; Hieracosphinx; Isfet; Medjed; Mehen_Board_Game_Snake_God_Egypt; Meretseger; Nemty; Serpopard; Set animal; Sphinx; Taweret; Teka-her; Unut_Egypt_Rabbit-Snake-Lion_Goddess; Uraeus; Wadjet

allegedly Ancient Egyptian

Cynocephali; Phoenix

Notify me if there are mistakes or if any of these creatures, beings or figures should not be used in art or fiction. (Note that every artist & writer should consider whether use of these figures is appropriate whether someone has complained or not).

#mythic creatures#mythic creature list#legendary creatures#legendary creature#legendary being#legendary beings#creature list#legendary creature list#monster list#list of monsters

1 note

·

View note

Text

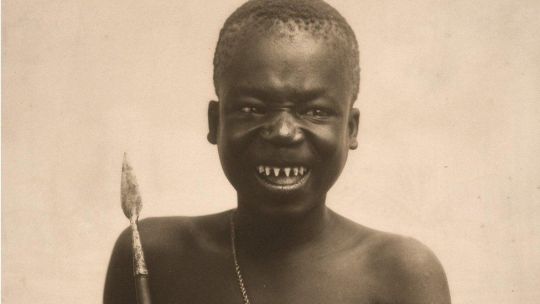

Ota Benga (c. 1883 – March 20, 1916) was a Mbuti (Congo pygmy) man, known for being featured in an exhibit at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis and as a human zoo exhibit in 1906 at the Bronx Zoo. He had been purchased from African slave traders by the explorer Samuel Phillips Verner, a businessman searching for African people for the exhibition, who took him to the US. While at the Bronx Zoo, he was allowed to walk the grounds before and after he was exhibited in the zoo’s Monkey House. He was placed in a cage with an orangutan as a lampoon on Darwinism. To enhance the primitive image and presumably protect himself if need be from the ape, he was given a functional bow and arrow. He used this instead to shoot at visitors who mocked him and partially as a result of this the exhibition ended. Except for a brief visit to Africa with Verner after the close of the St. Louis Fair, he lived in the US, mostly in Virginia, for the rest of his life.

African-American newspapers around the nation published editorials strongly opposing his treatment. Robert Stuart MacArthur, the spokesman for a delegation of African American churches, petitioned New York City Mayor George B. McClellan Jr. for his release from the Bronx Zoo. In late 1906, the mayor released him to the custody of James M. Gordon, who supervised the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn.

In 1910, Gordon arranged for him to be cared for in Lynchburg, where he paid for his clothes and to have his sharpened teeth capped. This would enable him to be more readily accepted in local society. He was tutored in English and began to work at a Lynchburg tobacco factory.

He tried to return to Africa, but the outbreak of WWI in 1914 stopped all ship passenger travel. He fell into a depression and died by suicide. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

1 note

·

View note

Text

https://www.liberty.edu/champion/2017/10/lynchburg-honors-ota-benga-with-historic-marker-where-he-died/

Lynchburg honors Ota Benga with historic marker where he died

Lynchburg unveils historic marker to honor the memory of the Congolese pygmy Ota Benga.

Ota Benga found sanctuary in Lynchburg after being displayed at zoos in New York and St. Louis in the early 1900s.

Among the hills of Lynchburg’s White Rock Cemetery lies the body of a Congolese pygmy named Ota Benga, who found deliverance in the Hill City after being displayed for his appearance at the Bronx Zoo’s Monkey House in the early 20th century. Where exactly Benga is buried remains unknown—decades of neglect caused the cemetery itself to be forgotten up until 1998 when it was rediscovered.

Despite the 101-year span between now and the day he killed himself on Seminary Hill, the memory of Benga has not been completely erased.

Formerly known as Mbye Otabenga, and later as Otto Bingo by Lynchburg residents, Benga and his incredible story have been depicted through movies and books. Brooklyn-based band Piñataland paid homage with a song titled “Ota Benga’s Name.” He even has a MySpace page.

And Benga was once again remembered Sept. 16 as the city of Lynchburg unveiled a historic highway marker in his memory.

The News & Advance reported more than 50 people gathered that Saturday morning to dedicate the marker at the intersection of Garfield Avenue and Hewitt Street. Among the crowd was Lynchburg Africa House Director Ann van de Graaf, Benga’s biographer Pamela Newkirk and others whose ancestors had welcomed the man into their city.

During the ceremony, Lynchburg Mayor Joan Foster announced Sept. 16 to be Ota Benga Remembrance Day.

“I want this to be remembered as a day of remembrance for Ota Benga,” Foster said at the ceremony. “His story touches me deeply.”

Benga had been living in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the turn of the century when his Mbuti tribe was virtually exterminated by the Force Publique—a group of Congolese and Belgian soldiers under the King of Belgium’s command.

The soldiers killed Benga’s wife and two children, and he was subsequently sold into slavery. In 1902, he was eventually traded for what van de Graaf said was salt and a piece of cloth to South Carolinian explorer Samuel Verner.

Verner had been commissioned by the St. Louis World’s Fair to venture out and retrieve Africans for an exhibition. He convinced Benga to travel with him, and two years later, he was a hit at the World’s Fair. People flocked to witness his 4-foot-10-inch, 104-pound frame. If they paid Benga five cents, he would flash his pointed teeth—”Gim’ nick, show teef,” he would allegedly say.

After the exposition, Verner brought Benga back to Africa, where he tried to readjust back to normal life while exploring the continent with Verner. But after his second wife died, Benga returned to America with his companion, and entered into an unorthodox living situation at the American Museum of Natural History in August 1906 and later, the Bronx Zoo.

There, he was free to roam the facilities, often helping employees take care of the animals and befriending an orangutan named Dohong. However, Zoo Director William T. Hornaday had different ideas, moving Benga’s hammock in a vacant cage of the zoo’s Monkey House and convincing him to shoot targets with a bow and arrows.

The New York Times caught wind of the Bronx’s newest resident, according to the Sept. 9 issue bearing “Bushman Shares a Cage With Bronx Park Apes” as its headline.

September 1906 saw 220,000 patrons of the zoo—double the number of visitors from September a year before. Upon entering the park, many would head straight to see Benga—billed as “The Missing Link”—wrestle with Dohong or play with his weapons.

Pamela Newkirk, author of “Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga,” writes of the damage the crowd inflicted upon the African.

“Benga became the object of pointing fingers, audible gasps, and bellowing laughter,” Newkirk wrote. “He did not initially comprehend their language, but could feel both the sting of their scorn and the pang of their pity…[He] could see his humanity…monstrously distorted.”

The exhibition, however, was short lived. Despite the grotesquely substantial enthrallment of the crowd, opposition quickly grew. New York’s African-American community was outraged, and Hornaday finally released Benga from his care.

The Mbuti pygmy spent the next decade of his life trying to adjust to American culture. In 1910, he relocated to Lynchburg, which became his sanctuary for the rest of his life.

Here, he enrolled in Virginia Theological Seminary, living with the school’s president, Hunter Hayes, for the next six years. He befriended African-American poet Ann Spencer, who taught him English, and worked at a nearby tobacco factory.

“He was so badly treated in New York at the zoo, and also in St. Louis,” van de Graaf told the News & Advance in a March interview. “But in Virginia, here in Lynchburg, he was happy… Here he found some peace, I think.”

But whatever peace he found was not enough. His desire to return to Africa grew stronger, as did his despair when the emergence of World War I hindered his plans to do so. On March 20, 1916, Benga shot himself in the heart, possibly out of torment at the hands of the 7,000 miles separating him from his home.

Over a century later, the marker now stands on the last street Benga walked, its inscription relaying his tragic story to anyone who might walk by. During the ceremony, Newkirk said the marker—the brainchild of van de Graaf— not only pays respect to Benga, but also to the city that sheltered him.

“Lynchburg gave this tragically displaced stranger home and semblance of family,” Newkirk told the crowd, as reported by the News & Advance. “This marker reflects your city’s values and highest ideals. So as you honor a man whose soaring humanity could neither be tarnished nor erased by the inhumanity of others, you illuminate your own.”

#Lynchburg honors Ota Benga with historic marker where he die#Ota Benga#mbiti trive#congolese#kidnapped african#human zoos#bronx human zoo#nyc#human zoos in america#human tragedy#Black History Matters

1 note

·

View note

Photo

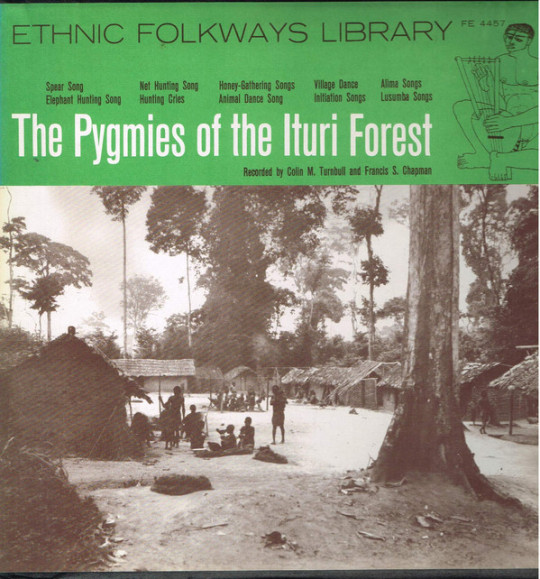

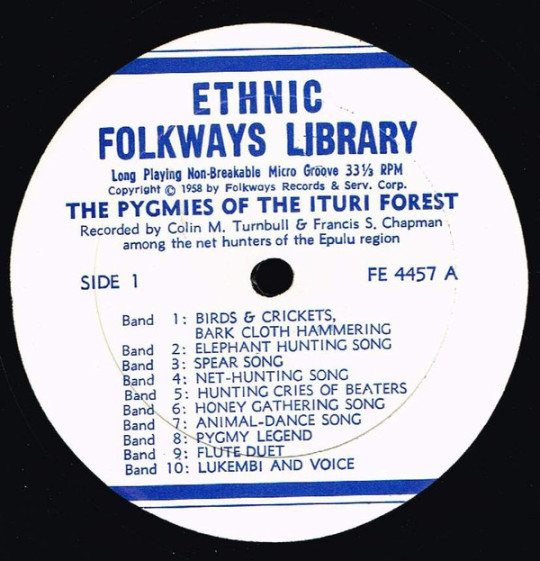

La playlist de l'émission de ce jeudi matin sur Radio Campus Bruxelles entre 6h30 et 9h : Full Moon Ensemble "Tribute to Bob Kaufman" (Crowded with Loneliness/Comet Records/1970-2022) Thelonious Monk "Straight, No Chaser" (Straight, No Chaser/Columbia Records/1967) Alexis Degrenier "Fatiguer" (La Mort Aura Tes Yeux/Murailles Music/2022) Daniel Schmidt with Gamelan Encinal & Mills Student Ensemble "Cloud Shadows" (Cloud Shadows/Recital/2022) Eric Chenaux "5 Intros and Spring" (Hello Eyes/ULYSSA/2022) Mim & Charlène Darling "La poudre" (L'amour aux mille parfums/L'amour aux mille parfums/2022) Bachir Attar & Elliott Sharp "Boujeloudia" (In New York/Dikraphone/1990-2022) Wau Wau Collectif "Xale (Toubab Dialaw Kids Rhyme)" (Mariage/Sahel Sounds-Sing a song fighter/2022) La Jungle "Helizona" (II/Black Basset Records/2016) Michel Cloup "Brûle brûle brûle" (Backflip au-dessus du chaos/Ici d'ailleurs/2022) Astéréotypie "Fantôme de Broglie, Fantôme de Strasbourg" (Aucun mec ne ressemble à Brad Pitt dans la Drôme/La Belle Brute/2022) Virgin Prunes "Baby Turns Blue" (...If I Die, I Die/Rough Trade Records/1982-2022) Tortoise "Not Quite East of the Ryan" (Rhythms, Resolutions & Clusters/Thrill Jockey Records/1995-2022) Samedi Dimanche (Nina Hennart + Joey Wright) "Catherine" (Samedi Dimanche/Wild Goose Chase/2022) Ivor Cutler "The Market Place" (An Elpee and Two Epees/Decca Records/1959-2005) Lee Scratch Perry "Supersonic Man" (The Compiler Vol. 1/Re Rectangle/2001) Rob "Make It Fast, Make It Slow" (Ghana Soundz (Afro-beat, Funk & Fusion In 70’s Ghana)/Soundway Records/1978-2002) The Pygmies of the Ituri Forest (with Ba Mbuti) "Spear Song" (The Pygmies of the Ituri Forest/Folkways Records/1958) Slowdive "Catch the Breeze" (7"/Creation Records/1991) Fleetwood Mac Christine McVie (1943-2022) "Oh Daddy" (Rumours/Warner Bros. Records/1977) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cln_FyMtLqc/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Video

youtube

youtube

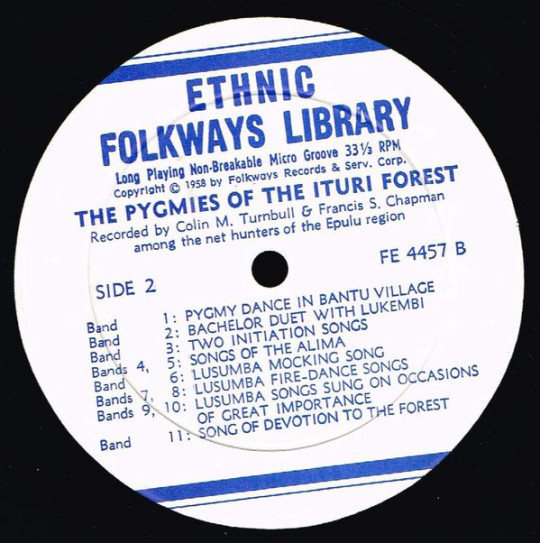

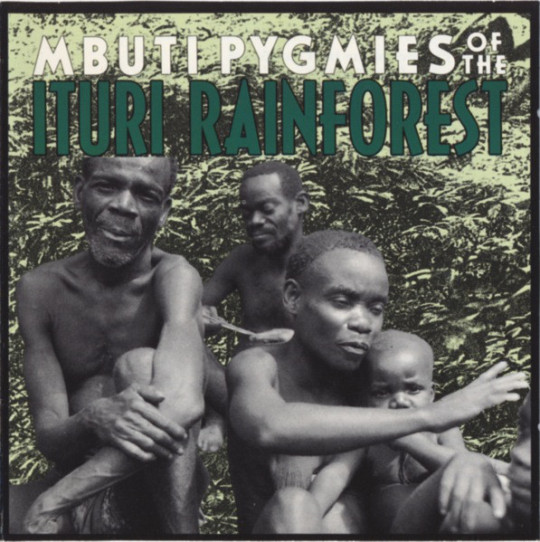

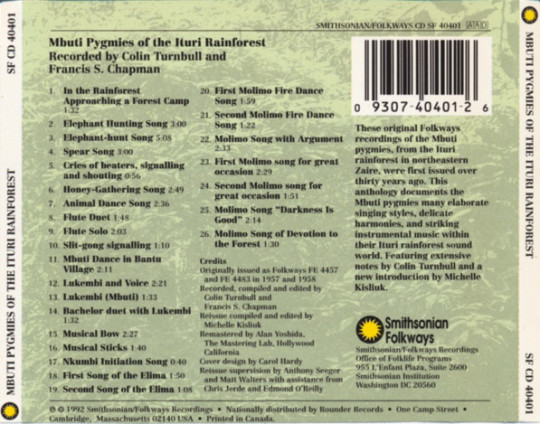

Mbuti Pygmies Of The Ituri Rainforest - Bachelor duet with Lukembi

Mbuti Pygmies Of The Ituri Rainforest - Pygmy Dance In Bantu Village

from

Mbuti Pygmies Of The Rainforest (Folkways, 1958)(Ethnic Folkways Library / Folkways FE 4457)

Recorded By Colin Turnbull And Francis S. Chapman

also

Mbuti Pygmies Of The Rainforest (Smithsonian Folkways, 1992)

****************************************************************************************

Mbuti Pygmies of the Ituri Rainforest captures the variety and tonal quality of the solo and choral traditions present in Mbuti vocal music. Songs are primarily concerned with Mbuti's nomadic life and the forest, from which their lives and those of the animal kingdom are sustained.

#1950s#africa#congo#pygmies#mbuti pygmies#folk#world#tribal#tribal music#ethnic#ethnic music#ethnomusicology#traditional#traditional music#smithsonian folkways#fieldrecording#colin turnbull#francis s. chapman#music#music blog

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Mushroom gathering lends itself especially well to lyrical accompaniment, for it is not in the least bit strenuous and often takes place in beautiful and spacious primary forest.... Yodels-calls or cries in which there is a transi tion between chest and throat voice—are the most natural and effective way to use the voice in this environment, be cause the voice resonates through the trees; both high and low notes hang in the air at the same time."

[...]

In the nighttime boyobi ceremony, fast drumming is added to the insect and human chorus, and as we mark the time, the forest music clearly has its place, the waves of overlapping crickets and cicadas, a high wash of frequencies whose musical purpose comes through. Bugs are above it all.

Here's a sonogram of part of the puya gathering ceremony, showing how the overlapping multispecies' rhythms appear:

The point I want to make with this picture is that it looks clearly organized, with different sounds specifically appearing at clear frequency ranges over time. The natural rainforest soundscape is no random melee of cacophonous sounds, but some kind of natural, total composition that nature has evolved itself. Human hocketing song is at the bottom, and higher up the fuzzy frequencies of bugs, frogs, occasional birds with a clear rhythmic crack. It's a very organized continuous soundscape, a clear image of acoustic niches filling the screen, a sonic Mbuti design that science puts into a picture. You could almost draw it as you listen. Every creature has its place amid the sonic frequencies, and seems to stay out of each other's way.

bug music, david rothenberg

#he keeps callin the mbuti 'pygmies' which is like..... :| ...... but this is a really cool phenomenon so im writing it down#reading#scraps book

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read too many ethnography books and now when I think about the religion of peolle I know irl my first reaction is a sort of startle at it jumping out of the books at me. Like unexpectedly meeting an mbuti pygmy in person

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

mbuti mythology • tore

tore is a god of the forests who supplies animals to hunters. he is also a thunder god who appears as a storm and hides in rainbows. most importantly, tore appears as a leopard in the initiation rites. the first pygmies stole fire from tore; he chased them but could not catch them, and when he returned home, his mother had died. as punishment, he decreed that humans would also die, and he thus became the death god.

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Horrific Story of Ota Benga

Benga was born in the Ituri Forest, in the extreme northeast of the colony, to the Mbuti Pygmies. His people lived in loose bands of family groups of between 15 and 20 people, moving from one temporary village or camp to another as the seasons and hunting opportunities dictated. Benga married young and fathered two children, which put him on track to start his own family and perhaps someday lead a band himself, like the Mbuti had done for thousands of years.

But that wasn’t to be. Benga would never lead his own band.

When he was still a teenager, the eastern Congo erupted into a war that saw mass deportations, raids by Arab slavers, and an invasion by the Force Publique, a Belgian-led occupying army that was manned by the dregs of the colony and commanded by some of the worst sadists Belgium could produce; the Force Publique was originally formed to enforce rubber quotas and beat complainers with hippopotamus-hide whips.

Like many colonial militias, they were corrupt: they raped and murdered villagers, even collecting severed hands and heads. Sometime in the late 1890s, Force Publique “soldiers” found Benga’s family camp and killed his entire family. He was out hunting at the time, so he only got to see the aftermath of the massacre. To a hunter-gatherer like Benga, the family is life itself. Without them, he had the choice of wandering alone until he died, or seeking out a new family group and begging them to take him on as a helper.

However, aside from dying or finding a new family, fate tossed Benga a third option.

A short time after losing his family, he was picked up by slave traders who put him in chains and dragged him out of the forest, which had been the only home he had ever known. They put him to work as a laborer in an agricultural village. It was there, in 1904, that Benga was discovered by, of all people, an American businessman and amateur explorer named Samuel Verner.

Verner had been sent to the Congo on an expedition commissioned by the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, which was planning an exhibit for the St. Louis World’s Fair that would “educate” the public in what was then a racist, pseudoscientific brand of anthropology.

Verner’s job was to find some authentic African pygmies to display as “missing links” in human evolution. Looking at Benga, a lean, very black, very short man with teeth that had been filed into points, Verner knew he had what he needed. He bought Benga for a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth.

Verner’s group promptly brought Benga to St. Louis, where he was the hit of the 1904 World’s Fair.

He and the other captive Africans he had been lumped in with quickly figured out that the crowd wanted to see genuine African “savages,” so they started imitating the dancing and war-whoops they saw the nearby American Indians doing. He made friends with Geronimo and charged increasingly interested visitors five cents to see his teeth. At one point, the National Guard had to be called in to control the crowds because they were getting so large.

After the fair, Benga travelled with Verner and even returned to Africa for a time. In 1905, he took up residence with another Congolese tribe, the Batwa, and married a woman from the tribe. The marriage only lasted a few months, ending when Benga’s wife died from a snakebite. At loose ends again, Benga travelled back to the United States with Verner in 1906.

Upon returning to the United States in 1906, Benga’s first stop was a spare room at the American Museum of Natural History, where he again “delighted” visitors by pretending to be a babbling half-human. Everybody at the museum liked Benga, but the director refused to pay Verner the salary he was asking for, so eventually the pair picked up and moved to the Bronx Zoo.

Benga was allowed free movement through the zoo grounds, but his hammock was slung in the primate exhibit. He was displayed as part of the New York Anthropological Society’s exhibit on human evolution. Local black clergy were appalled by the exhibit and demanded Benga’s release, even lobbying the governor to force the zoo to shut down the display. Benga was eventually released into the custody of James Gordon, the minister who had led the charge to free him. He then went to live in Gordon’s black orphanage.

Still unhappy with his life, Benga eventually moved to Lynchburg, Virginia, to live with friends of Gordon named the McCrays. Gordon still managed Benga’s affairs, and he seemed to have definite ideas about how the 27-year-old man should live. Gordon arranged to have Benga’s teeth capped and enrolled him in a school for non-white children. He also got Benga a job at a local tobacco plant, where he seemed to have been popular and told his story for free root beer.

However, by 1914, Benga was planning a final return to Africa. Life in America, he decided, wasn’t for him. With the money he made from the tobacco job, Benga started putting things in order and looking for passage to the nearest port to his homeland. By this time, Leopold II was dead, and the Belgian government had stepped in to clean up some of the mess he’d left behind. Conditions were looking up in the Congo, and it was time to go home for good.

But this return passage was not to be. The outbreak of World War I suspended most cross-Atlantic shipping, and the German occupation of Belgium threw the Congo into bureaucratic chaos, with nobody allowed in or out. On March 20, 1916, depressed at the thought of not being able to return home, Ota Benga shot himself in the heart.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The greatest modern authority on hunter-gatherer egalitarianism is, by general consent, the British anthropologist James Woodburn. In the post-war decades Woodburn conducted research among the Hadza, a forager society of Tanzania. He also drew parallels between them and the San Bushmen and Mbuti Pygmies, as well as a number of other small-scale nomadic forager societies outside Africa, such as the Pandaram of south India or Batek of Malaysia. Such societies are, Woodburn suggests, the only genuinely egalitarian societies we know of, since they are the only ones that extend equality to gender relations and, as much as is practicable, to relations between old and young.

Focusing on such societies allowed Woodburn to sidestep the question of what is being equalized and what isn’t, because populations like the Hadza appear to apply principles of equality to just about everything it is possible to apply them to: not just material possessions, which are constantly being shared out or passed around, but herbal or sacred knowledge, prestige (talented hunters are systematically mocked and belittled), and so on. All such behaviour, Woodburn insisted, is based on a self-conscious ethos, that no one should ever be in a relation of ongoing dependency to anybody else. This echoes what we heard in the last chapter from Christopher Boehm about the ‘actuarial intelligence’ of egalitarian hunter-gatherers, but Woodburn adds a twist: the real defining feature of such societies is, precisely, the lack of any material surplus.

—The Dawn of Everything: A New Hisory of Humanity, David Graeber and David Wengrow, 2021

7 notes

·

View notes