#colin turnbull

Text

Plant Immune System Part 3

The plant immune system is the topic of my PhD thesis, which I'm currently writing following several years of lab-based research as a PhD student at Imperial College London under the supervision of Professor Colin Turnbull.

Here's an introduction to my research, which focused on how certain plants defend themselves against aphids.

Aphids are an important insect pest that threaten agriculture worldwide. As we learned in the previous post, plant resistance (R) genes control resistance to specific pests and pathogens through interaction with effectors from the invaders. Since examples of R gene-dependent aphid resistance have been documented in different plant species, aphid-specific R genes may enable the development of resistant crops.

In the model plant Medicago truncatula, there are some varieties that are resistant to aphids and other varieties that are susceptible to Pea Aphids (Acyrthosiphon pisum). Whether the plant is resistant also depends on the variety of aphid. In my project, the A17 plant is resistant to PS01 aphids but not to N116 aphids, while the DZA plant is susceptible to both aphid varieties.

What is the key difference in the resistant versus susceptible plants? Resistant A17 plants have a portion of their genome “Resistance to Acyrthosiphon pisum 1” (RAP1) which determines resistance to PS01 aphids, but the genes controlling the defence response and physiological defence mechanisms remain unknown. Two candidate R genes located in RAP1, designated “RAP1A” and “RAP1B”, may control resistance.

My main objective in my PhD project has been to determine whether RAP1A and RAP1B control aphid resistance, and to investigate the RAP1-mediated defence response. I look forward to sharing the findings in publications and in talks next year!

Image credit: Original diagram by Katia Hougaard with images from the Turnbull Lab.

#katia_plantscientist#science#biology#research#plants#botany#plantbiology#phdproject#plantbiology#plantscience#sciencecommunication#diagrams#phd#imperialcollegelondon#phdthesis#medicago#aphid#plantimmunesystem#pestsandpathogens#plantpathology#womeninscience#plantbiologist

#katia plant scientist#botany#plant biology#plants#plant science#diagram#science communication#science#sciencecore#plant scientist#biology#biologist#phdblr#phd life#phdjourney#phd student#phd research#gradblr#stem#immune system#cell biology#molecular biology#genetics#aphid#medicago#clover#plant pathology#my work

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1. Human Nature

Recommended Reading

Robert K. Dentan, The Semai: A Nonviolent People of Malaya. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979.

Christopher Boehm, “Egalitarian Behavior and Reverse Dominance Hierarchy,” Current Anthropology, Vol.34, No.3, June 1993.

Pierre Clastres, Society Against the State, (1974), New York: Zone Books, 1987.

Leslie Feinberg, Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman, Boston: Beacon Press, 1997.

David Graeber, Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology, Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2004.

Colin M. Turnbull, The Forest People, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961.

James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

Bob Black, “The Abolition of Work,” 1985. *

#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#anarchy works#reading list#recommended reading

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: The Mountain People by Colin M. Turnbull Hardcover Book.

0 notes

Text

Run, Jump, Throw

By Logan Maloley

On Thursday, April 6, the junior high track team participates in the HTRS invite at Pawnee City.

Girls Placings

Kinsley Benson: 400 - 1st; High jump - 3rd; Long jump - 4th

Taelyn Blecha: 4x100 - 2nd; 4x200 - 1st; 100 - 2nd; 200 - 1st

Emalyse Gottula: 400 - 3rd; 200 - 3rd; High jump - 4th; Pole vault- 1st

Breonna Gyhra: Shot Put - 5th; Discus - 5th

Denielle Gyhra- Due to a possible error in recording, Denielle should've placed 5th in shot put with a throw of 22 feet, but unfortunately did not get her seat.

Ericca Gyhra: 4x100 - 2nd; 4x200 - 1st

Kailey Hartman: 800 - 5th; 1600 - 5th

Adelyn Sisco: Shot Put - 2nd

Kaylee Turnbull: 4x100 - 2nd; 4x200 - 1st

Addison Peterson: 100 Hurdles - 3rd; 300 hurdles - 5th

Haylee Plager: 800 - 4th; 1600 - 3rd; Triple jump - 1st

Ashlyn Puhalla: 800 - 6th; Discus - 3rd; 4x200 - 1st

Boys Placings

Justin Beahr: 4x200 - 2nd

Dante Bassinger: 100 - 5th; 4x200 - 2nd; 4x100 - 4th

Colin Fender: 400 - 5th; Pole vault - 3rd; 4x100 - 4th

Luke Hunzeker: 4x100 - 4th

Jaydon Johnson: Shot put - 3rd; Discus - 5th

Dylan Layne: 4x200 - 2nd; Discus - 2nd; Shot put - 2nd place

Aidan Peterson: Shot put - 5th; Discus - 3rd

Aiden Tozer: 200 - 3rd; 100 hurdles - 3rd; Triple jump - 2nd

Carson Duryea: 4x100 - 4th; 1600 - 4th

Jaiden Howard: 4x200 - 2nd

Payton Rose: Triple jump - 1st

The next junior high track meet is the Pawnee City Invite on Thursday, April 13, at Pawnee City.

0 notes

Photo

The Forest People - Colin Turnbull

0 notes

Photo

Colin Turnbull (deceased)

Gender: Male

Sexuality: Gay

DOB: 23 November 1924

RIP: 28 July 1994

Ethnicity: White - English

Occupation: Anthropologist, writer

Note: Had HIV

#Colin Turnbull#lgbt history#gay history#lgbt#mlm#male#gay#1924#rip#historical#white#Anthropologist#writer#hiv

84 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

youtube

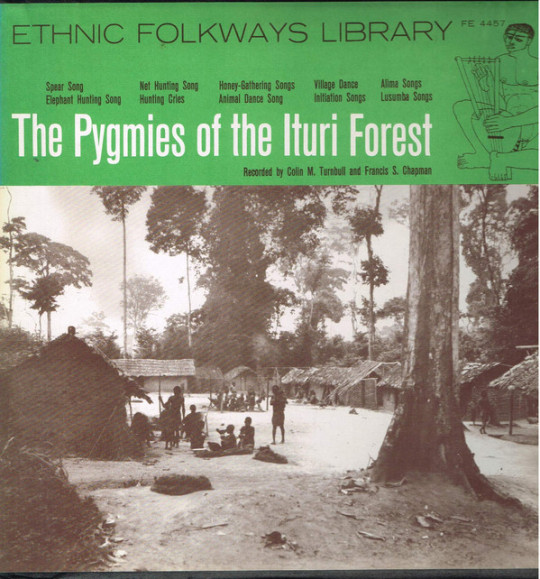

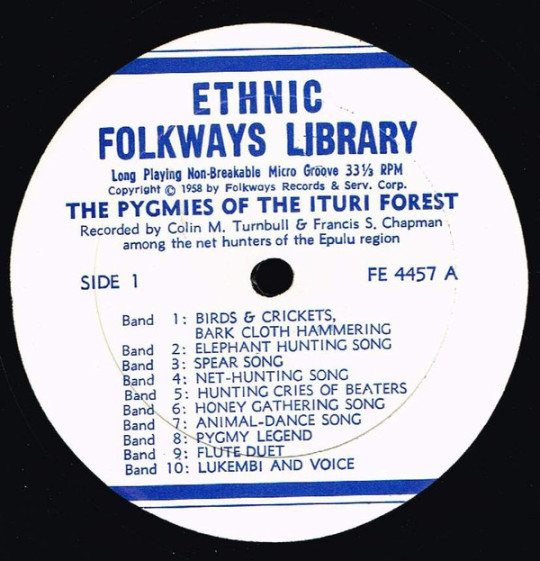

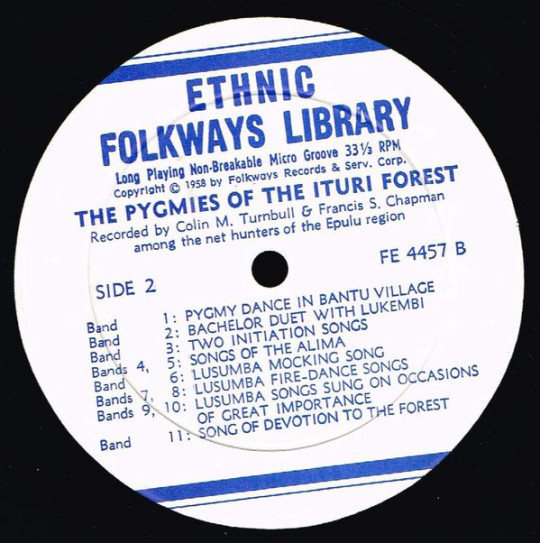

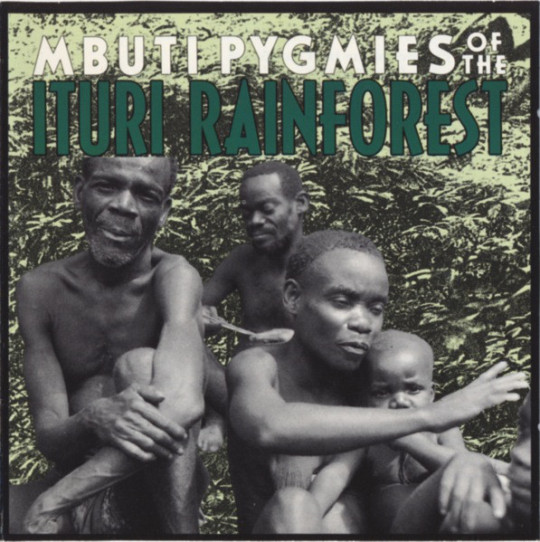

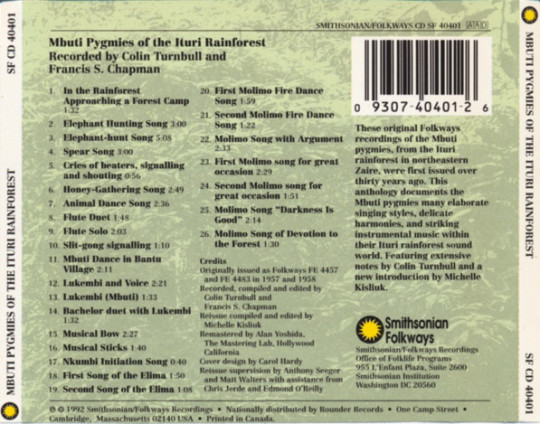

Mbuti Pygmies Of The Ituri Rainforest - Bachelor duet with Lukembi

Mbuti Pygmies Of The Ituri Rainforest - Pygmy Dance In Bantu Village

from

Mbuti Pygmies Of The Rainforest (Folkways, 1958)(Ethnic Folkways Library / Folkways FE 4457)

Recorded By Colin Turnbull And Francis S. Chapman

also

Mbuti Pygmies Of The Rainforest (Smithsonian Folkways, 1992)

****************************************************************************************

Mbuti Pygmies of the Ituri Rainforest captures the variety and tonal quality of the solo and choral traditions present in Mbuti vocal music. Songs are primarily concerned with Mbuti's nomadic life and the forest, from which their lives and those of the animal kingdom are sustained.

#1950s#africa#congo#pygmies#mbuti pygmies#folk#world#tribal#tribal music#ethnic#ethnic music#ethnomusicology#traditional#traditional music#smithsonian folkways#fieldrecording#colin turnbull#francis s. chapman#music#music blog

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Alan Hull- Blue Murder

#alan hull#blue murder#pipedream#hull#john turnbull#colin givson#ken craddock#ray laidlaw#ray jackson#dave brooks#folk#folk rock#music#music is love#music is life#music is religion#raining music#70s#70s music

1 note

·

View note

Text

COLIN GRAEME (BRITISH 1858-1910)

REX

signed, inscribed and dated ’96, oil on canvas

Lyon and Turnbull

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy First Day of Summer 2024 from my garden to yours! I hope you have a summer filled with botanical delights, whether that is tending your own garden, travelling to experience wonders of the plant world in person, creating an indoor jungle via your houseplant collection, or working on plant science research in the lab or in the field.

This summer, I will be dividing my time between maintaining my own garden, working on my PhD thesis with my supervisor Professor Colin Turnbull from Imperial College London, and creating more inspiring new content for this page!

This collage features (going clockwise) James Galway climbing rose (Rosa sp), Mock Orange (Philadelphus × purpureomaculatus), Red Valerians (Valeriana rubra), Ox Eye Daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare), and Russell Lupin (Lupinus x regalis).

#katia_plantscientist #katia #flowers #summer #cotswolds #cottagegarden #womeninscience #womeninstem #biologist #scientist #plantscientist #botanist #gardener #firstdayofsummer #midsummer #summertime #garden

#katia plant scientist#botany#plant biology#plants#plant science#katia hougaard#flowers#pink flowers#white flowers#gardens#gardening#cottagecore#plant scientist#scientist#botanist#women in science#summer#midsummer eve#garden#floral#first day of summer

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1. Human Nature

Aren’t people naturally competitive?

In Western society, competition is so normalized it’s no wonder we consider it the natural mode of human relations. From youth, we’re taught that we have to be better than everyone else to be worth anything ourselves. Corporations justify firing workers, depriving them of sustenance and healthcare, so the company can “stay competitive.” Fortunately, it does not have to be this way. Industrial capitalism is only one of thousands of forms of social organization humans have developed, and with any luck it won’t be the last. Obviously, humans are capable of competitive behavior, but it’s not hard to see how much our society encourages this and suppresses cooperative behavior. Countless societies throughout the world have developed cooperative forms of living that contrast greatly with the norms at work under capitalism. By now, nearly all of these societies have been integrated into the capitalist system through colonialism, slavery, warfare, or habitat destruction, but a number of accounts remain to document the great diversity of societies that have existed.

The Mbuti hunter-gatherers of the Ituri Forest in central Africa have traditionally lived without government. Accounts by ancient historians suggest the forest-dwellers have lived as stateless hunter-gatherers during the time of the Egyptian pharoahs, and according to the Mbuti themselves they have always lived that way. Contrary to common portrayals by outsiders, groups like the Mbuti are not isolated or primordial. In fact they have frequent interactions with the sedentary Bantu peoples surrounding the forest, and they have had plenty of opportunities to see what supposedly advanced societies are like. Going back at least hundreds of years, Mbuti have developed relationships of exchange and gift-giving with neighboring farmers, while retaining their identity as “the children of the forest.”

Today several thousand Mbuti still live in the Ituri Forest and negotiate dynamic relationships with the changing world of the villagers, while fighting to preserve their traditional way of life. Many other Mbuti live in settlements along the new roads. Coltan mining for cell phones is a chief financial incentive for the civil war and the habitat destruction that is ravaging the region and killing hundreds of thousands of inhabitants. The governments of Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda all want to control this billion dollar industry, that produces primarily for the US and Europe, while miners seeking employment come from all over Africa to set up camp in the region. The deforestation, population boom, and increase in hunting to provide bush meat for the soldiers and miners have depleted local wildlife. Lacking food and competing for territorial control, soldiers and miners have taken to carrying out atrocities, including cannibalism, against the Mbuti. Some Mbuti are currently demanding an international tribunal against cannibalism and other violations.

Europeans travelling through central Africa during their colonization of that continent imposed their own moral framework on the Mbuti. Because they only encountered the Mbuti in the villages of the Bantu farmers surrounding the Ituri forest, they assumed the Mbuti were a primitive servant class. In the 1950s, the Mbuti invited Western anthropologist Colin Turnbull to live with them in the forest. They tolerated his rude and ignorant questions, and took the time to teach him about their culture. The stories he recounts describe a society far outside of what a Western worldview considers possible. Around the time that anthropologists, and subsequently, Western anarchists, began to argue about what the Mbuti “meant” for their respective theories, global economic institutions were elaborating a process of genocide that threatens to destroy the Mbuti as a people. Notwithstanding, various Western writers have already idealized or degraded the Mbuti to produce arguments for or against primitivism, veganism, feminism, and other political agendas.

Therefore, perhaps the most important lesson to take from the story of the Mbuti is not that anarchy — a cooperative, free, and relatively healthy society — is possible, but that free societies are not possible so long as governments try to crush any pocket of independence, corporations fund genocide in order to manufacture cell phones, and supposedly sympathetic people are more interested in writing ethnographies than fighting back.

In Turnbull’s perspective, the Mbuti were resolutely egalitarian, and many of the ways they organized their society reduced competition and promoted cooperation between members. Gathering food was a community affair, and when they hunted often the whole band turned out. One half would beat the bush in the direction of the other half, who waited with nets to snare any animals that had been flushed out. A successful hunt was the result of everyone working together effectively, and the whole community shared in the catch.

Mbuti children were given a high degree of autonomy, and spent much of their days in a wing of the camp that was off-limits to adults. One game they frequently played involved a group of small children climbing up a young tree until their combined weight bent the tree towards the earth. Ideally, the children would let go all at once, and the supple tree would shoot upright. But if one child was not in synch and let go too late, the child would be launched through the trees and given a good scare. Such games teach group harmony over individual performance, and provide an early form of socialization into a culture of voluntary cooperation. The war games and individualized competition that characterize play in Western society provide a notably different form of socialization.

The Mbuti also discouraged competition or even excessive distinction between genders. They did not use gendered pronouns or familial words — e.g., instead of “son” they say “child,” “sibling” instead of “sister” — except in the case of parents, in which there is a functional difference between one who gives birth or provides milk and one who provides other forms of care. An important ritual game played by adult Mbuti worked to undermine gender competition. As Turnbull describes it, the game began like a tug-of-war match, with the women pulling one end of a long rope or vine and the men pulling the other. But as soon as one side started to win, someone from that team would run to the other side, also symbolically changing their gender and becoming a member of the other group. By the end, the participants collapsed in a heap laughing, all having changed their genders multiple times. Neither side “won,” but that seemed to be the point. Group harmony was restored.

The Mbuti traditionally viewed conflict or “noise” as a common problem and a threat to the harmony of the group. If the disputants could not resolve things on their own or with the help of friends, the entire band would hold an important ritual that often lasted all night long. Everyone gathered together to discuss, and if the problem still could not be solved, the youth, who often played the role of justice-seekers within their society, would sneak into the night and begin rampaging around the camp, blowing a horn that made a sound like an elephant, symbolizing how the problem threatened the existence of the whole band. For a particularly serious dispute that had disrupted the group’s harmony, the youth might give extra expression to their frustration by crashing through camp itself, kicking out fires and knocking down houses. Meanwhile, the adults would sing a two-part harmony, building up a sense of cooperation and togetherness.

The Mbuti also underwent a sort of fission and fusion throughout the year. Often motivated by interpersonal conflicts, the band would break up into smaller, more intimate groups. People had the option to take space from one another rather than being forced by the larger community to suppress their problems. After travelling and living separately for a time, the smaller groups joined together again, once there had been time for conflicts to cool down. Eventually the whole band was reunited, and the process started over. It seems the Mbuti synchronized this social fluctuation with their economic activities, so their period of living together as an entire band coincided with the season in which the specific forms of gathering and hunting require the cooperation of a larger group. The period of small, disparate groups coincided with the time of the year when the foods were in season that were best harvested by small groups spread throughout the whole forest, and the period when the whole band came together corresponded with the season in which hunting and gathering activities were better accomplished by big groups working together.

Unfortunately for us, neither the economic, political, or social structures of Western society are conducive to cooperation. When our jobs and social status depend on outperforming our peers, with the “losers” being fired or ostracized without regard to how it hurts their dignity or their ability to feed themselves, it’s not surprising that competitive behaviors come to outnumber cooperative behaviors. But the ability to live cooperatively is not lost to people who live under the destructive influences of state and capitalism. Social cooperation is not restricted to societies like the Mbuti who inhabit one of the few remaining pockets of autonomy in the world. Living cooperatively is a possibility for all of us right now.

Earlier this decade, in one of the most individualistic and competitive societies in human history, state authority collapsed for a time in one city. Yet in this period of catastrophe, with hundreds of people dying and resources necessary for survival sorely limited, strangers came together to assist one another in a spirit of mutual aid. The city in question is New Orleans, after Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005. Initially, the corporate media spread racist stories of savagery committed by the mostly black survivors, and police and national guard troops performing heroic rescues while fighting off roving bands of looters. It was later admitted that these stories were false. In fact, the vast majority of rescues were carried out not by police and professionals, but by common New Orleans residents, often in defiance of the orders of authorities.[5] The police, meanwhile, were murdering people who were salvaging drinking water, diapers, and other living supplies from abandoned grocery stores, supplies that would otherwise have been ultimately thrown away because contamination from floodwaters had made them unsalable.

New Orleans is not atypical: everyone can learn cooperative behaviors when they have the need or desire to do so. Sociological studies have found that in nearly all natural disasters, cooperation and solidarity among people increase, and it is common people, not governments, who voluntarily do most of the work carrying out rescues and protecting one another throughout the crisis.[6]

#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#anarchy#anarchists#libraries#leftism#anarchy works

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Among nomadic Mbuti communities, Colin Turnbull described the habit of claiming kinship relations with every other member of the community, as well as with neighboring communities, regardless of whether common ancestors or blood relations were a genetic “fact.” Traditionally, kinship relations were deliberately ambiguous, all the adults of a community were parents to all the children, and all the children of the same age group were siblings. In fact, the anthropologist reports that the Mbuti got annoyed when he tried to map out a “factual” family tree of the community to ascertain who, within a Western conception, was related and who was not.

Societies without an anti-authoritarian ethos, we can surmise, treated relations not as an opportunity for everyone’s mutual enrichment, but as a resource to be controlled. And for someone to gain power from access to a resource, they first must make that resource artificially scarce. In fact, the whole Western concept of an “objective” kinship based on shared genetic material, or in earlier terms, “blood,” is little more than a massive mythical justification for limiting familial relations.

“Worshiping Power: An Anarchist View of Early State Formation” by Peter Gelderloos

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Revisiting the Ik

The book club I’m a member of has just read the 1970s anthropology book The Mountain People, by Colin Turnbull. At the time it was a cause célèbre: my wife went to a theatre production at London’s Roundhouse based on it. Since then it’s become more controversial.

The Ik (pronounced Eek) are a group who live in Uganda, close to the Kenyan border. They had, at least by Turnbull’s (contested)…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

The Mountain People - Colin Turnbull

[NB: This is a case of the book being cited as containing wildly incorrect information. You can read more about it here]

0 notes

Photo

Colin Turnbull (deceased)

Gender: Male

Sexuality: Gay

DOB: 23 November 1924

RIP: 28 July 1994

Ethnicity: White

Occupation: Anthropologist, geologist, writer

Note: Had HIV

#Colin Turnbull#lgbt#lgbt history#queer history#gay history#male#gay#1924#rip#historical#white#scientist#Anthropologist#writer#geologist#hiv

61 notes

·

View notes