#legendary creatures

Text

Legends of the humanoids

Reptilian humanoids (12)

Toyotama-hime – Wani (Dragon) Goddess disguised as a human

Wani was a dragon or sea monster in Japanese mythology. Wani is discribed as "crocodile", or sometimes "shark".

Toyotamahime (See) is a goddess in Japanese mythology. Daughter of the sea god Watatsumi, she was said to reside in a dragon palace. Their palace was as if made from fish scales and supposedly lies undersea. Her true form was “Yahiro no Owani (meaning giant crocodile, approx. 24 m long)”, and she was the wife of Hoori (See2), is known as the epitome of human–animal marriage tales. She was the mother of Ugayafukiaezu-no-Mikoto (See3), father of Emperor Jinmu (the first Emperor: See4), and sister of Tamayori-hime (See5), the Emperor's mother.

Toyotamahime makes a fateful meeting with the demigod prince, Yamasachi, also known as Hoori ("Fire-Subside"). They married and lived happily in the dragon palace. 3 years later, she and her husband Hoori, who missed home, went ashore to give birth.

She then warned her husband, "All people from other parts of the world give birth in the form of their native country when giving birth. So I will give birth to a child in my true form”, and requested Hoori not watch how she gives birth. Hoori, however, was pazzled and peered in on his wife as she was giving birth, and saw her crawling around as a giant crocodile of about 24 metres (79 ft) long. He then startled in shock and retreated. Toyatama-hime learnt that being witnessed her true form by her husband, "I have always intended to pass through the path of the sea," she said, "but I am ashamed that you should have observed my true form.” She blocked the sea path, leaving the child behind and left.

伝説のヒューマノイドたち

ヒト型爬虫類 (12)

トヨタマヒメ 〜人間に変身する和邇 (龍) の女神

和邇は、日本神話に登場する龍または海の怪物のことである。和邇は「ワニ」、ときには「サメ」と表現されることもある。

トヨタマヒメ(参照)は、日本神話の女神である。海神ワタツミの娘で、竜宮城に住んでいると言われている。その宮殿は魚の鱗でできたようなもので、海中にあるとされる。その正体は「八尋の大和邇(やひろのおおわに: 体長約24mの巨大な鰐の意)」で、ホオリ(参照2)の妻であったことから、異類婚姻譚の典型として知られる。神武天皇(初代天皇: 参照4)の父である鵜葺草葺不合尊(うがやふきあえずのみこと: 参照3)の母であり、天皇の母である玉依姫(たまよりひめ: 参照5)の姉である。

トヨタマヒメは、半神の王子ヤマサチ、通称ホオリと運命的な出会いを果たす。二人は結婚し、竜宮城で幸せに暮らしたが、3年後、故郷が恋しくなった夫のホオリとともに出産のために陸に上がった。

その時、トヨタマヒメは夫に「すべて他国の者は子を産む時になれば、その本国の形になつて産むのです。それでわたくしももとの身になつて産もうと思いますが、わたくしを御覽遊ばしますな」と忠告した。ところが夫のホオリはその言葉を不思議に思い、妻が今盛んに出産している最中に覗いてみると、八丈 (約24m) もある長い鰐になって這いずり回っていた。そしてホオリは畏れ驚き退いた。しかるにトヨタマヒメは夫が窺見した事を知り、御子を産み置いて去った。「わたくしは常に海の道を通つて通おうと思っておりましたが、わたくしの形を覗いて御覽になつたのは恥かしいことです」と言い、海の道をふさいで帰ってしまった。

#toyotama-hime#Japanese mythology#dragon#humanoids#legendary creatures#hybrids#hybrid beasts#cryptids#therianthropy#legend#mythology#folklore#nature#art#sea monster

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome the newest member to Dimir Faerie Court - Talion, the Kindly Lord. I don't know how any of these can work together, they're all so different. They seriously need a connecting theme between them.

#mtg#magic the gathering#faeries#dimir#legendary faeries#legendary creatures#fantasy card game#wotc#wizards of the coast#oona#nymris#wydwen#talion#lorywn#shadowmoor#eldraine

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

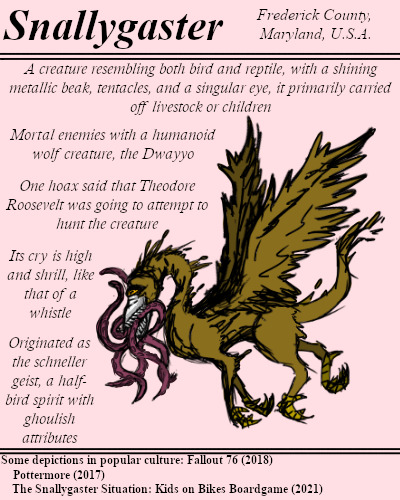

A fearsome legend who draws from German folklore spirits and dragons. The snallygaster flies almost completely silently, diving down to carry off prey in order to drain their blood for sustenance.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#monster#dragon#snallygaster#maryland legend#maryland folklore#frederick county maryland#legendary creatures#schneller geist#dwayyo#theodore roosevelt hoax

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

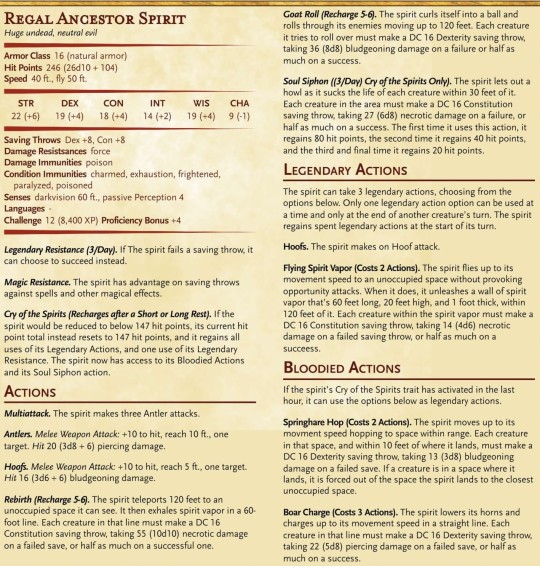

https://www.patreon.com/posts/regal-ancestor-76434944

Enjoy the Regal Ancestor Spirirt Homebrew statblock! support me on patreon and check out my tiktok for it!

https://www.tiktok.com/t/ZTRq3VdKQ/

#d&d 5th edition#d&d#dnd5e#dnd#elden ring#dark souls#video games#soulsborne#legendary creatures#boss#loot#regal ancestor spirit#homebrew 5e#homebrew#stat block

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notas sobre La Cabalgada de Hellequin

Uno de los problemas que tengo al escribir, y estoy seguro de no ser el único, es que tiendo a documentarme demasiado. Algo me sugiere una idea, esa me lleva a otra, lo que implica documentarme sobre algo distinto y buscar la manera de enlazarlo todo y así sucesivamente. Normalmente suelen ser cosas más o menos relacionadas, pero La Cabalgada de Hellequin es posiblemente el relato que he escrito con más influencias distintas, aunque conectadas, así que me parece interesante explorarlas todas.

La base del relato es la Cacería Salvaje. Es un mito bastante conocido, extendido principalmente en el norte de Europa, aunque tiene ramificaciones hacia el este y el sur, incluso en la península Ibérica. Hay numerosas variaciones, pero en todas se trata de un personaje principal, que puede ser un ser sobrenatural como un dios o diosa, un hada o duende o un fantasma o un ser humano condenado, que dirige una cacería formada por jinetes, perros y aves de cetrería en un tropel que se desplaza por los aires con gran estrépito en ciertas noches del año.

Las dinastías del relato están basadas en distintas versiones de la Cacería, adoptando el nombre del personaje protagonista y algunas de sus características. Pero además necesitaba detallar a sus acompañantes, los perros de presa de la cacería, y para eso tuve que profundizar un poco más.

En el caso de la Dinastía Berchtold se trata de la figura mitológica de Perchta o Berchta, también llamada Holla o Holda (de ahí Bercht-hold), asociada con la rueca, el invierno, la luz y la brujería, además de con la cacería salvaje, en la que se dice que lidera una tropa de demonios. Eso me dio la idea de hacerla acompañar de perchten, que es el nombre que reciben los disfraces de demonios que se usan en procesiones tradicionales en los Alpes y que se asocian con Frau Perchta. El resto de los detalles me los sugirió el personaje: la capucha y la falda de tejido balístico, el arma que recuerda a un huso y una rueca pero dispara proyectiles de energía (luz) y la rueca en manos del oso del emblema. Elegí un oso porque es un símbolo típico de Europa central y del norte, y de ahí surgió el nombre del personaje, Úrsula, que en latín viene a significar "Osita".

La cuestión con Hellequin es un poco más compleja. La primera aparición del nombre hace referencia a una leyenda de cacería salvaje en Normandía en el siglo XI. El nombre parece derivar de Herle cyning, "rey de la hueste", relacionado con el Erlkönig alemán y con el Herla (Herla King) anglosajón mencionado por Shakespeare, ambos líderes de sus respectivas cacerías. Pero lo más interesante es que de Hellequin deriva "arlequín", el personaje de la Commedia dell'Arte, y eso me dio la estética del personaje, con sus rombos de colores y su máscara negra, y el nombre de su arma, el "Marotte", que es el cetro con cascabeles de los bufones. Pero también me dio algo más: en el teatro Arlequín se caracteriza por dar cabriolas y saltos y de ahí los repulsores de la armadura de Jacques Hellequin.

Faltaban los acompañantes. En la leyenda normanda Hellequin lideraba una hueste de demonios y resulta que en la Divina Comedia de Dante aparece un demonio de nombre Arlicchino, parte de los Malebranche o Malasgarras, los demonios guardianes de Malebolgia. Eso me dio el nombre de los acompañantes de Hellequin e inspiró el que tengan alas y usen cuchillos curvos, a semejanza de los ganchos que usan en Dante, y me dio también el nombre del planeta natal de la dinastía Hellequin, Malebolgia. Pero fui un poco más allá: los nombres de los Malebranche son los de la Divina Comedia, usando parcialmente la traducción de Martínez de Merlo. En esta traducción Arlicchino pasa a ser Aligacho, así que me pareció interesante usar este nombre para el Malebranca al que Hellequin va a rescatar. Para imaginar el aspecto de los Malebranche, perros de presa pero también demonios, me inspiré en este cuadro del Diablo y San Agustín, de Michael Pacher (aunque con menos cuernos y sin ojos en el culo).

A los nombres de otras dinastías llegué de formas similares. La Dinastía Herletinga comparte etimología con la Hellequin: es la latinización de Herle cyng. Sus constructos, los eruli, se inspiran en los harii que cita Tácito, guerreros germanos que luchaban de noche y pintados de negro como fantasmas y cuyo nombre puede estar relacionado también con Herle. Eruli en concreto lo tomé de los hérulos, una tribu germánica muy posterior con una etimología posiblemente similar. El nombre de Suartas, el único erul que se menciona en el relato, es el de un caudillo hérulo. Como los harii se pintaban de negro para combatir me hizo gracia que los constructos fueran de un color tan oscuro que absorbe la luz como un agujero negro o pintura Vantablack.

Los yeth son los sabuesos yeth, una de las formas de perros negros demoníacos de las leyendas británicas, y pertenecen a la Dinastía Dewer, cuyo nombre es el del demonio que lidera la cacería salvaje en Dartmoor. Los dips son perros fantasmales de la leyenda catalana. Hay varios mitos catalanes que parecen similares a la Cacería Salvaje, pero como algunos son creaciones literarias modernas preferí no darle nombre a la Dinastía. Del mismo modo, podría haber nombrado varios seres similares de la mitología canaria, pero aquí no parece haber equivalente a la cacería, seguramente porque hasta su introducción reciente no había presas de caza mayor.

#worldbuilding#inspiración#documentación#anotaciones#relatos#ciencia ficción#mitología#folklore#mythology#legends#legendary creatures#wild hunt#cacería salvaje

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tundra Unicorn stallions do battle, stirring up a flock of snow buntings.

Another piece for my next self-published book I have planned for 2023 (not to be confused with my new art book, due imminently).

#art#steve white art#traditional art#traditional drawing#unicorn#mythological creature#legendary creatures#unicorns

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

lóng [龙] (Chinese Dragons)

#writelykeekee#writerksmith#ksmith research#handy resources#learn with me#writing research#dragons#Chinese dragons#Chinese culture#culture#Chinese mythology#Chinese folklore#Chinese legend#mythology#folklore#myths and legends#legendary creatures#mythical creatures#龙#lóng

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#rogue racers fantasy artwork#fantasy artwork#dragon artwork#here be dragons#legendary creatures#rogue racer#amazing artwork

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legends of the humanoids

Reptilian humanoids (5)

Wuxing – the connections between the Five Dragon Kings (Ref) and the Five Elements philosophy

To better understand the origins of the Five Dragon Kings and the ancient Chinese legend, it is worth mentioning the wuxing of natural philosophy, which states that all things are composed of five elements: fire, water, wood, metal and earth.

The underlying idea is that the five elements 'influence each other, and that through their birth and death, heaven and earth change and circulate'.

The five elements are described as followed:

Wood/Spring: a period of growth, which generates abundant vitality, movement and wind.

Fire/Summer: a period of swelling, flowering, expanding with heat.

Earth is associated with ripening of grains in the yellow fields of late summer.

Metal/Autumn: a period of harvesting, collecting and dryness.

Water/Winter: a period of retreat, stillness, contracting and coolness.

The wuxing system, in use since the Han dynasty (2nd century BCE), appears in many seemingly disparate fields of early Chinese thought, including music, feng shui, alchemy, astrology, martial arts, military strategy, I Ching divination, and traditional medicine, serving as a metaphysics based on cosmic analogy.

The wuxing originally referred to the five major planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, Mars and Venus), which were thought of as the five forces that create life on earth. Wu Xing litterally means moving star and describes the five types of Qi (all the vital substances) cycles through various stages of transformation. As yin and yang continuously adjust to one another and transform into one another in a never-ending dance of harmony, they tend to do so in a predictable pattern.

The lists of correlations for the five elements are diverse, but there are two cycles explaining the major interaction. The yin-yang interaction, which by increasing or decreasing the qualities and functions associated with a particular phase, it may either nourish a phase that is in deficiency or drain a phase that is in excess or restrain a phase that is exerting too much influence (see below):

The Creation Cycle (Yang)

Wood feeds Fire

Fire creates Earth (ash)

Earth bears Metal

Metal collects Water

Water nourishes Wood

The Destruction Cycle (Yin)

Wood parts Earth

Earth dams (or absorbs) Water

Water extinguishes Fire

Fire melts Metal

Metal chops Wood

The Huainanzi (2nd BCE) describes the five colored dragons (azure/green, red, white, black, yellow) and their associations (Chapter 4: Terrestrial Forms), as well as the placement of sacred beasts in the five directions (the Four Symbols beasts, dragon, tiger, bird, tortoise in the four cardinal directions and the yellow dragon.

伝説のヒューマノイドたち

ヒト型爬虫類 (5)

五方龍王(参照)と五行思想の関連性

ここで、五方龍王の起源、そして古代中国の伝説をよく理解するために、万物は火・水・木・金・土の5種類の元素からなる、という自然哲学の五行思想について触れておきましょう。 5種類の元素は「互いに影響を与え合い、その生滅盛衰によって天地万物が変化し、循環する」という考えが根底に存在する。

五行は次のように説明されている:

木は、春の豊かな生命力、動き、風を生み出す成長期。

火は、夏の太陽の暖かさの下で行われる成熟の過程、熱で膨張する時期。

土は、晩夏の黄色い野原での穀物の成熟に関連している。

金は、秋の収穫、収集、乾燥の時期。

水は、冬の雪に覆われた暗い大地の中に潜む新しい生命の可能性と静寂の時期。 漢の時代 (紀元前2世紀頃) から使用されてきた五行説は、音楽、風水、錬金術、占星術、武術、軍事戦略、易経、伝統医学など、中国初期の思想の一見バラバラに見える多くの分野に登場し、宇宙の類推に基づく形而上学として機能している。

五行とは文字通り「動く星」を意味し、五種類の気(生命維持に必要なすべての物質)が様々な変容の段階を経て循環することを表している。陰と陽は絶え間なく互いに調整し合い、調和の終わりのないダンスで互いに変化していくため、予測可能なパターンで変化する傾向がある。

五行の相関関係は多様だが、主要な相互作用を説明する2つのサイクルがある。陰陽の相互作用は、特定の相に関連する資質や機能を増減させることで、不足している相に栄養を与えたり、過剰な相を排出したり、影響力を及ぼしすぎている相を抑制したりする (以下参照):

相生(陽)のサイクル

木は燃えて火を生む

火が土 (灰) をつくる

土は金属を産出する

金属は表面に水を集める

水は木を育てる

相克(陰)のサイクル

木は大地を構成する

土は水を堰き止める

水は火を消す

火は金属を溶かす

金属が木を切る

『淮南子』(紀元前2世紀)には、五色の龍(紺碧・緑、赤、白、黒、黄)とその関連性 (第4章: 地の形)、五方位への聖獣の配置(四枢の四象徴獣、龍、虎、鳥、亀、黄龍)が記述されている。

#wuxing#5 dragon kings#5 elements#taoism#yin yang#humanoids#legendary creatures#hybrids#hybrid beasts#cryptids#therianthropy#legend#mythology#folklore#dragon#nature#art

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

You know, I really hope that when Standard gets to a point where all these overpowered Planeswalkers are gone, that Standard will be a better place to enjoy playing. That goes double for all these Legendary Creatures that are basically previously printed Enchantments on legs. It really sucks that it will take three years, if not more, to see any progress in the enjoyability of Standard. /rant

#mtg#magic the gathering#standard format#planeswalkers#legendary creatures#power creep#fantasy card game#wotc#wizards of the coast#hasbro

0 notes

Text

I'll elaborate if you want

#dragons#mythical creatures#mythology#folklore#myth#dinosaurs#dinosaur bones#dinosaur fossils#mythological creatures#folkloric creatures#legendary creatures#reptiles#legendary reptiles#mythical reptiles#mythological reptiles#change my mind

1 note

·

View note

Text

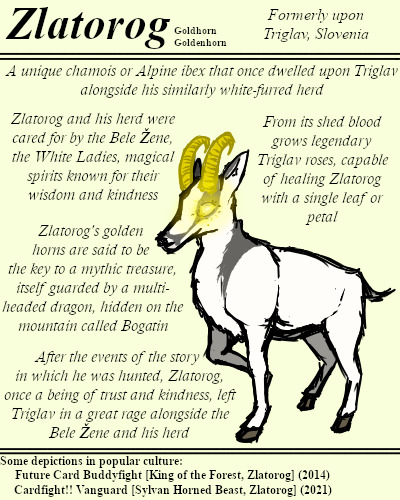

As an additional note, on the northern face of Mount Prisojnik, it seems the face known as Ajdovska Deklica, or the Heathen Maiden, can be seen. This face is that of a prophetic maiden (sometimes said to be a nymph or forest spirit), and it is said that she once predicted that a newborn chid would one day kill Zlatorog. Her siblings, angry with this prophecy, cursed her to turn to stone after she returned to her home.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#slovenian legend#slovenian folklore#slovenian folktale#zlatorog#goldhorn#goldenhorn#triglav#bogatin#legendary creatures

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE LAST WOLF

GUEST EPISODE · WITH SARA PEARL

Storyteller: Sara Pearl

Host: Rick Scott

The wind wolves kick up foam flecks from a heaving sea as their hunt hurtles toward the horizon. I wonder: am the last left alive? The thought expands, vast as the lake, vast as the sea, vast as the sky… my mind cannot hold it."

This is the tale of the last wolf in England, narrated by the wolf.

The unabridged version of Sara's story is available on Amazon Kindle for £2.

A more traditional version of the Last Wolf can be heard in one of our bonus episodes.

ON HUMPHREY HEAD

with Sara Pearl

The train from Lancaster to Kent’s Bank runs over water. I’m reminded of the sea tram in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, but we leave not a ripple in our wake. The sea sweeps beneath the rails and out the other side in a slick of silver, carving out crescents of sand and seabirds.

At Kent’s Bank, the platform borders high tide. Across the expanse of foam-flecked grey, a rim of dim shapes is visible: Lancaster and a ferry port, watermarks on the clouded horizon. There, across the water to the right, is the forest-furred outline of Humphrey Head.

Though this is the first time I’ve stood within sight of Humphrey Head, I know its plants, wildlife, views, the shape of its coastline in 1577, two centuries’ worth of local travelogues, and kilometres of the surrounding Google Streetviewed roads.

Yet, if you had mentioned Humphrey Head to me in 2017, I would’ve had no clue of its existence.

In spring 2018, I began to track the Cumbrian tale of the last wolf in England (also new to me), poring over worn 19th century travelogues on lectern-shaped cushions in the Rare Books room…

…leafing through a hefty 1978 volume of the Annals of Cartmel while the old timer for the ancient library lights clicked down into darkness…

…perching at a table in a local bakery at 7.30 a.m., zipping from stop to stop along Holy Well Lane via Google Streetview like a speedy virtual superhero…

…scrutinising antiquarian image archives for long-lost maps of the Cumbrian coastline…

…explaining to a patient librarian how a copy of a page from the Ulverston Advertiser from 1853 stored in the British Newspaper Archive would prove to be the clue to unravelling the whole mystery, and how very grateful I was to be holding it in my hand (I’m unsure the queue of readers behind me shared my enthusiasm).

The tale I had set out to find can be traced back to a poem entitled ‘The Last Wolf’ authored by the mysterious “P.” published in the Ulverston Advertiser on Thursday 28 April 1853 (Dr Rick Scott has a copy, if any reader cares to dare the chivalric epic).

On reflection, I pursued the legend with the combined fervour of folktale fangirl and (aptly) dogged detective. This culminated in The Last Wolf story you’ll be able to hear on Lore and Legend in November 2019. I’m still chasing a couple of leads, but case [almost] closed.

So, when I see Humphrey Head across the water, I feel a puzzle piece click into place: this is Humphrey Head in late summer on Sunday 1 September 2019, viewed from the north-east. If the past is anything to go by, this view will look very similar in another two to four centuries; I’m just passing through.

Across the tides of time, Christopher Saxton the cartographer is making measurements here in 1577, the Atkins family are traveling through in 1820, and Edwin Waugh is jotting down lyrical travelogue notes sometime in the mid-1800s…

*

The poem ‘The Last Wolf’ was printed just 3 years after the death of William Wordsworth who, with the Lake Poets, had popularised the Lake District as a place of outstanding natural beauty and literary interest. It is possible that both Atkins’ and Waugh’s Lake District travelogues were inspired by the Lake Poets’ lyrical descriptions of this region. The route of the poem encircles not only a geographical, but also a literary, cultural and historical landscape.

Though the route of ‘The Last Wolf’ seemed improbable, when drawn on a map with calculations of speed and distance, its furthest extent matched the distance a wolf can travel in a day, and the duration of the route corresponded with the distance a wolf can travel in urgency. The anonymous poet P may have been familiar with the endurance of horses or dogs, or have used an historical source in addition to Atkins’ letter. One notable feature of Atkins’, P’s and Mercier’s versions of the tale is the pervasive absence of the titular wolf, which in all three cases appears for just a few lines.

The humans of the Lake District claimed locations by naming them, as in the case of ‘Ulverston’, marking them with an edifice or monument like Wraysholme Tower or Cartmel Priory and creating a visual representation on a map. What did the same terrain mean to the wolf? Zoology and biology reveal that wolves mark by scent and sound, and demarcate territory by patrolling. If we read the route as the wolf’s territory, then every step in the poem represents land being claimed away from one creature by another. A wolf knows the land in ways humans never can: through scent, close to the ground, through intricate soundscapes and personal memories. This intimate knowledge is the wolf’s advantage. However, the wolf lacks the skills of tool-making and the domestication of dogs and horses. For the wolf, the route is demarcated by lieux de memoire similar to those described by Pierre Nora and those traditionally used by Arctic communities for navigation.

My retelling of the legend takes the Ulverston Advertiser’s ‘The Last Wolf’ as its starting point, following the route detailed in the poem. The themes of the poem include the demarcation of land and, as Mercier and Winder note, the fulcrum of an historical moment as an expanding agrarian landscape and lifestyle superseded the nomadic lifestyles of forest-dwelling wolves. In this legend, field is in conflict with forest, wolf with sheep, human with wolf. Mercier places the events of the legend in the fourteenth century, when the English wool industry was expanding and the related increase in the value of sheep flocks increased the expense of wolf-related sheep loss. As Winder notes, the thriving of sheep flocks in wolfless pastureland played a key role in the expansion of the English economy through the international wool trade.

My version aims to counterbalance the poem by imagining the wolf’s voice. In the present context of proposals for the rewilding of wolves in Scotland, the establishment of an Eden Project at Morecambe Bay, and Extinction Rebellion’s description of the fragility of our own human future, this tale is once again relevant to our times. This retelling is not straightforward advocacy - there is no doubt that a hungry wolf can be a hazardous companion for a human and a fatal one for a sheep. I would no more ask a human to cohabit with a wolf than invite a wolf to cohabit with a human.

Notably, P’s poem is a tale in which one wolf outruns all but one of ‘threescore men’ (Ulverston Advertiser, p. 4). Consequently, I started out with one important assumption: the wolf is smarter than me. As I sketched out a relief map of the route, I realised how much strategy of terrain it involved, and turned to Sun Tzu’s The Art of War for tactical advice. The wolf presented in the podcast is a virtual simulation - my model of data from various sources run through the narrative and geographic parameters outlined by the poem. I expect my model to fall short of the experiences and observations of people who work with wolves every day and apologise for the limitations of my research, knowledge and skill.

*

Having memorised the maps, landscape and travelogue accounts, Humphrey Head had became a place I felt I knew well. So, when passing by, I made a detour to read the land with my feet.

One must carefully cross train tracks to reach the village of Kent’s Bank. On the land side, a neatly-painted hut houses box seats, a tiny library and a display telling the story of Dennis Philips, who grew up here to become the youngest Station Master in the UK in 1956 and the final Station Master of Kent’s Bank. In melancholy contrast, the display records that no one now remembers the name of the porter who stands beside him, smiling in the ‘best kept station’ award photo. The tides of time reach further than the sea.

The station incorporates a small but airy whitewashed art studio filled with stained glass sun catchers and glazed ceramics. I ask directions of the gentleman supervising this Sunday afternoon.

Following the described route, the tarmac road climbs through woodland, up past well-appointed peak-roofed houses and bungalows with carefully tended gardens, to the crossroads at the edge of Kent’s Bank. From there, left down the steep and winding Jack’s Hill, passing sunflowers and a neat subterranean garage. Scattered houses spread out below, and a party of Nordic walkers marches by in full mountain gear, stopping to assure me this is the right direction.

Left again, through what appears to be a shared backyard, and down into a neat woodland avenue. Sunlight dapples the pale mud track, patterned with puddles and leaves. It is a tunnel of trees, the end a perfect circle of landscape, like a painted miniature.

Beyond this circle is an expanse of late summer sky. Left again, onto a well-kept tarmac track. Through a gate, I glimpse Humphrey Head, larger now. The afternoon sun adorns the roadside with a lace of leaf-shadows. The hedgerow is bright with harvest: thick clusters of green, red and blackberries, umbrellas of bright elder, pastel flowers. Above, the sky is soothing blue, floating motionless cotton wool clouds. Pastureland smoothly undulates to either side, a quilt stitched together with woodland. Sheep drift sleepily from pasture to pasture, mirroring the clouds.

Wraysholme Tower, squat and square, now incorporated into a farmhouse with cattle fields, caps a low rise to my left. The drive is gated off. Turning a curve in the road, I watch three unlit warning lamps and cross a railway line, deserted. Fields stretch in every direction. The sun catches the clouds with the brightness of a gleam through glass. Humphrey Head is clearly visible now, rising above the hedgerows. Tall old wooden telegraph poles run along the road; plain staves of wood with no footholds or fastenings, the wire simply looped and hooked at the top. This straight stretch of road continues all the way to the horizon, like the archetypal road of the American desert. I put one foot in front of the other, patient under the sun. One step becomes one thousand. Tall red grasses rustle above the hedgerow, feathered in the breeze.

At the end of the road, an old wooden signpost to Humphrey Head - the only one on the route - points right. The rise begins to sweep upward to my left, and a more modern sign notifies me of an upcoming left turn to Humphrey Head Outdoor Education Centre. I take it, climbing the grassy slope - and find myself on the gently rising back of the ridge.

Wading through long glossy grass, I pass embedded outcroppings of limestone, climbing upwards and upwards, passing grazing cows and hunched hawthorns, up and up, seeing the sinking sands of Morecambe Bay stretched, etched and mirror-bright to the right; emerald patchwork pastures spread out behind me; and a thin mane of woodland rising to the left. The curve of a rainbow crosses the distant rainclouds beyond.

The view is extraordinary - wisps of cloud catch the light like lantern flames. The low sun of a late summer afternoon sets the bay ablaze. Lone hawthorns curl sculpturally, clawing at the wind. A basic fence - simple staves and wire again - keeps walkers from sliding down the righthand slope into Holy Well Lane. The wind from that direction is extraordinary - a relentless, roaring, body-buffeting force hurling in from the sea. The tide has carved sinuous paths and channels into the bay. I wonder whether these change every day, demarcating a new map each time.

A herd of cows have braved the wind to graze along the ridge. The honey-coloured light of a sinking sun stretches the shadows further and further.

At the apex of Humphrey Head is a trig point (S5589). I realise now why Atkins and P favoured this as the vantage of the wolf - one can see for miles around, looking down at a living map, and the climb itself is not particularly onerous; a leisurely afternoon stroll rewarded with a disproportionately great view.

The outcroppings of rock are pale in colour and chalky in texture, with patches of dark grey and bright orange-yellow xanthoria parietina lichen. The water in one hollow is rust-coloured, but there is no trace of the rust marks from oxidised iron ore one would expect from deposits of the hematite famously found nearby in Barrow-in-Furness. I wonder whether the water is coloured by the lichen, which can be used as a pink dye.

Down the rocky ridge, the headland promontory extends into the tidal plain. A family are there, and seem to be watching an otter at play. Looking from the map on the wooden exit gate to the sands, I realise Holy Well Lane is flooded with a fast-flowing river of water, and call out to ask the family whether they can see the road from their position. The grandfather confirms it is flooded out. There is only one route back - over the ridge again - and no chance of seeing the Holy Well today. I climb a short way onto the rocky shelf above the fast flood, careful to keep safe footing, and to avoid stepping on what appears to be long grass but squelches alarmingly underfoot - there are numerous quicksand warnings in this area (in a yellow triangle, a tiny figure waves urgently while sinking below a black line).

Back over the ridge again. The family spin a frisbee across the blue and green of sky and land. The grandfather points out to me the distant cockle-picking tractors, who set out at low tide to scavenge the sands. I remember the cockle-pickers encountered by the Atkins family in Briggs’ Remains, more than a hundred years ago, and the more recent tragedy of the tides in Morecambe Bay. As the sun sets, shadows stretch across the grass, across the road, across the dirt track and Jack’s Hill - over which I struggle, but determinedly prove Nordic walking poles unnecessary - all the way across Kent’s Bank into evening, and later into night.

There is a preoccupation with and deep pride in the past at Kent’s Bank Station, Grange-over-Sands and Lancaster. Grange, particularly, has the air of a recently out of season Victorian seaside resort, with faux Norman arches in the station walls and elaborately swirling ironwork in bright heraldic shades (today, très steampunk). Standing under these arches, it does not seem strange for a faux-medieval poem to provide a frame narrative for the view from Humphrey Head, which may have been popular with the many 19th century visitors to the Lakes (it’s certainly the type of walk one could complete in a crinoline).

As the tide rolls out from the coastline of Kent’s Bank and Grange, it reveals a sometime undersea expanse of long grasses stretching all the way to the tideline; a perilous and temporary land of sinking sands.

*

For three days after finishing the recording script for Last Wolf, while battling ‘flu, I was haunted by the final scene:

It is like this: I am standing barefoot on the beach. The only sounds are the sound of the sea and a soft, high keening. The half-moon, high now, frosts waves inseparable in darkness from the sky. To the left, at the tideline, the hunter bends over the body of the wolf, wary, leaning heavily on his spear. To the right, by the rise, the one-eyed dog whines at the side of his companion, whose breath squeezes out in feeble wheezes. Further back, at the base of the cliff, the white hide of the horse spasms.

Around them, the night is quiet, calm and peaceful, and it feels like it shouldn’t be. It feels like there should be shouts or tears or protests, cortisol and adrenaline — some kind of noise, avalanche, tsunami, the clamour of disaster. But there’s just the breeze that brushes my arms and stirs my hair, cool salt and the sound of sea.

I wonder whether I told it wrong, whether that’s why I can’t leave. But this is the tale: of an ordinary day, in which terrible things happened. The protests are removed — they don’t occur here at this time, but in another place, centuries later. They can’t reach the casualties here. Would it make a difference to them, here, if they knew they were mourned by people whose hands can’t help them, whose voices can’t comfort them? But our only human representative here is the hunter, leaning on his spear, curved like the moon over the corpse of a creature he’s still too scared to touch (maybe it’s only playing dead). He doesn’t know this is the last wolf. He won’t realise until months or years later, and then won’t really care — except that it increases his fame. His colleague has already ridden home, ahead of the dark.

After a while — is the hunter counting the waves? — he will poke the corpse tentatively with his stick. Then roll it over. Monochrome in moonlight, it is clearly inanimate, stiffening. It was the wind, flickering in its fur, that frightened him. The eyeless dog limps from him to its companion, whining urgently, and this reminds him of the cold, that he is stranded, his aching, bruised and battered limbs, the long walk home. He looks at the horse — regretting, now, his recklessness? But he is determined. He staggers, slings the still-warm wolf over his shoulder. Its weight heats his back, shielding him from the cold. He remembers carrying his grandmother like this, some time before she died. Anchoring each step with his stick he follows his hound to the fallen one, sees it will not survive. What does he do then? In the morning, the tide will slide both horse and dog into the sea, after the peregrine feeds.

The hunter walks from the beach, slowly, painfully, stumbling, the hound’s high cry rebuking him, through the high grass, the billowing wind, step by step through the strange nocturnal world, accompanied by the inexorable moon. Gold points across the plain widen into planets, spheres, window panes. And he walks to the gate and the gatekeeper is silent, awed, shocked speechless. And he walks across the torchlit courtyard and through the muddy straw-strewn yard and under the archway, through cool halls which resound with the sounds of riotous feasting and abandonment. His slow steps echo, forgotten. And he enters, unnoticed at first, and then a hush spreads out, and out, and out… and there is only silence… and then a roar.

But I do not elect this representative. So I am on the beach, where I cannot leave her, standing in a frozen moment.

‘Vigil’, one calls it. Mourning ’til morning.

Now, having named it, I settle cross-legged on the sand, understand, and see the sun rise at last. I realise I am cold, damp with sea spray, and sand-sore… and I can leave the scene.

*

I catch the train back toward Lancaster in rain - sea and sky submerged in mist - and watch tiny seabirds shelter from the wind in wave-carved ripples of sand. The sea has the last word here, writing its story onto the land, erasing and writing again.

*

Here are a few pieces of flotsam and jetsam found on the shores of time, circa 2018-19:

—In 1538 the first Guide to the Sands of Morecambe Bay was appointed. This role survives today: http://www.guideoversands.co.uk/history/ and https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/apr/12/sands-of-time-run-out-for-queens-guide-to-morecambe-bay

—In 1577, a cartographer named Christopher Saxton published a map of Lancashire. On surviving copies of this map, Humphrey Head is clearly marked, though the shape of the sands and tideline are a little different to those on Google Maps 2019.

—In 1820, Leonard Atkins, in the company of his sister and uncle, travelled around the Lake District describing their journey via letters to his brother Tom, who was studying at Cambridge. Atkins included two stories from his uncle: ‘Wraysholme Tower' and ‘The Last Harrington’. These letters were later published in the Lonsdale Magazine, edited by John Briggs, and collected in The remains of John Briggs (1825).

—In 1825, the widow and friends of John Briggs published a compilation of The remains of John Briggs: containing Letters from the Lakes; Westmorland as it was; Theological essays; Tales; Remarks on the Newtonian theory of light; and Fugitive pieces / to which is added a sketch of his life, including Atkins’ letters.

—On Thursday 28 April 1853, the Ulverston Advertiser published a poem entitled ‘The Last Wolf’ by the mysterious “P.”.

—In 1864, Edwin Waugh included the same poem entitled ‘The Last Wolf’ by an anonymous author in his book Rambles in the Lake Country and its Borders.

—On Thursday 5 June 1873, the poem ‘The Last Wolf’ was reprinted by the Ulverston Advertiser.

—In 1884, Mrs Jerome Mercier used the narrative of the poem ‘The Last Wolf’ as a frame for a Christian romance novel for young readers.

Since Mrs Mercier’s The Last Wolf in 1884, this Cumbrian tale has fallen out of favour, though the title ‘The Last Wolf’ has been used in English by writers including Jim Crumley, MacGillivray, Mini Grey, László Krasznahorkai, Margaret Mayhew, Michael Morpurgo, David Shaw Mackenzie, David Stephen and Robert Winder. As Jim Crumley notes in his excellent exploration of wolves, last wolf tales proliferate. Creative works with this title can be found in Spanish ‘el ultimo lobo’, in French ‘le dernier loup’ and in Simplified Chinese ‘最后一只狼’. There is perhaps a fascination with the wolf viewed from a human perspective, with uniqueness and loss.

Bibliography

—Anon.,‘The Last Wolf’, in Soulby’s Ulverston Advertiser and General Intelligencer [newspaper] (Ulverston: 28 April 1853 and 5 June 1873), The British Newspaper Archive [online archive]. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk accessed May 2019.

—Bravo, Michael, North Pole: Nature and Culture (Reaktion Books, 2018)

—Briggs, John, ‘Letters III’, The remains of John Briggs: containing Letters from the Lakes; Westmorland as it was; Theological essays; Tales; Remarks on the Newtonian theory of light; and Fugitive pieces / to which is added a sketch of his life (Kirkby Lonsdale: A. Foster, 1825) pp. 35-39.

—Cumbria County History Trust, ‘Old Maps of Cumbria Gallery’ [online gallery] (2018). https://www.cumbriacountyhistory.org.uk/gallery/old-maps-cumbria-gallery accessed 10 December 2018.

—Google, ‘Cumbria’, ‘Humphrey Head’, ‘Kirkhead', ‘Holker’, ‘Newby’, ‘Leven’, ‘Torver’, ‘Coniston Old Man’, ‘Esthwaite’, ‘Sawrey's Pass’, ‘Windermere’, ‘Gummerhowe’, ‘Withels Lack’, ‘Aggerslack’, ‘Grange’, Google Images [online image repository] (2018). https://www.google.com/imghp?hl=en accessed 21 December 2018.

—Google, ‘Humphrey Head’ (street view), ‘Cartmel’ (street view), ‘Kirkhead’ (street view), ‘Holker’ (street view), ‘Newby’ (street view), ‘Leven’ (street view), ‘Torver’ (street view), ‘Coniston Old Man’ (street view), ‘Esthwaite’ (street view), ‘Sawrey’s Pass’ (street view), ‘Windermere’ (street view), ‘Gummerhowe’ (street view), ‘Withels Lack’ (street view), ‘Aggerslack’ (street view), ‘Grange’ (street view), Google Maps [online map] (2018). https://www.google.com/maps accessed 21 December 2018.

—Harris, Michelle, and Hughes, Brian, ‘Saxton’s Map 1577’, The Fylde & Wyre Antiquarian [website] (30 May 2007). http://wyrearchaeology.blogspot.com/2007/05/saxtons-map-1577.html accessed 10 December 2018.

—Mercier, Mrs. Jerome, The last wolf: a story of England in the fourteenth century (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge; New York: E. & J. B. Young and Co., 1884).

—Norgate, Jean, and Norgate, Martin, ‘Saxton 1579: Map, hand coloured engraving, Westmorlandiae et Cumberlandiae Comitatus ie Westmorland and Cumberland, scale about 5 miles to 1 inch, by Christopher Saxton, London, engraved by Augustinus Ryther, 1576, published 1579-1645’, Guides to the Lakes [website] (2014). http://www.geog.port.ac.uk/webmap/thelakes/html/saxton/sax9fram.htm accessed 10 December 2018.

—Stockdale, James, Annals of Cartmel (Beckermet: Michael Moon, 1978) pp. 5-20, 141-160.

—Sun Tzu, The Art of War (Filiquarian: November 2007; first published circa 5th century BC).

—Waugh, Edwin, ‘Over Sands to the Lakes: Chapter the Second’, Rambles in the Lake Country and its Borders (Manchester: John Heywood, 143, Deansgate; London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., 1864) pp. 77-83.

—Winder, Robert, ‘Peter and the Wolf’, The Last Wolf: The Hidden Springs of Englishness (London: Little, Brown, 2017) pp. 1-11.

#cultural legends#folklore history#legendary creatures#folktales and legends#folklore podcast#folklore tales#ancient legends#fables and legends#folklore storytelling#spotify#folklore#mythology#audio drama#fantasy#folk horror#podcast#storytelling#supernatural#legends#dark fantasy#horror#mystery#adventure#fiction#folk tales#creatures#folk music#worldbuilding#magic#enchanting

0 notes

Text

Don't It Make My Green Eyes Red: The Beast of Chickamauga Battlefield

Since originally publishing my first account Ole Green Eyes, I have had the good fortune to talk with some folks who have their own encounters with this particular entity, which in turn prompted me to dig deeper into the old accounts and reports.

Ol’ Green Eyes, whatever it may be, has roamed Chickamauga Battlefield since at least the time of the Civil War

In my very first book about all things wondrous, wicked, or weird found in the Mid-South, Strange Tales of the Dark and Bloody Ground, Chapter 34 revolved around the Haunted Hallowed Ground of Chickamauga. In that chapter, I chronicled several anomalous apparitions and other phenomena…

View On WordPress

#BIGFOOT#CRYPTOZOOLOGY#Fantastic Beasts#Green Ghoul of Chickamauga#LEGENDARY CREATURES#Old Green Eyes#STRANGE TALES

0 notes

Photo

Elesh Norn, Mother of Machines

Artist: Junji Ito

TCG Player Link

Scryfall Link

EDHREC Link

#mtg#magic the gathering#tcg#junji ito#elesh norn mother of machines#phyrexia: all will be one#legendary#creature#phyrexian#praetor

618 notes

·

View notes