#medieval biography

Text

This is why we still need Women’s History Month.

By Martha Gill

What was life like for women in medieval times? “Awful” is the vague if definite answer that tends to spring to mind – but this is an assumption, and authors have been tackling it with new vigour.

The Once and Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society by Eleanor Janega, and The Wife of Bath: A Biography by Marion Turner both contend that women were not only bawdier but busier than we thought: they were brewers, blacksmiths, court poets, teachers, merchants, and master craftsmen, and they owned land too. A woman’s dowry, Janega writes, was often accompanied with firm instructions that property stay with her, regardless of what her husband wanted.

This feels like a new discovery. It isn’t, of course. Chaucer depicted many such cheerfully domineering women. The vellum letter-books of the City of London, in which the doings of the capital from 1275 to 1509 were scribbled, detail female barbers, apothecaries, armourers, shipwrights and tailors as a matter of course. While it is true that aristocratic women were considered drastically inferior to their male equivalents – traded as property and kept as ornaments – women of the lower orders lived, relatively, in a sort of rough and ready empowerment.

It was the Renaissance that vastly rolled back the rights of women. As economic power shifted, the emerging middle classes began aping their betters. They confined their women to the home, putting them at the financial mercy of men. Female religious power also dwindled. In the 13th century seeing visions and hearing voices might get a woman sainted; a hundred years later she’d more likely be burned at the stake.

“When it comes to the history of gender relations, storytellers portray women as more oppressed than they actually were”

Why does this feel like new information? Much of what we think we know about medieval times was invented by the Victorians, who had an artistic obsession with the period, and through poetry and endless retellings of the myth of King Arthur managed somehow to permanently infuse their own sexual politics into it. (Victorian women were in many respects more socially repressed than their 12th-century forebears.)

But modern storytellers are also guilty of sexist revisionism. We endlessly retread the lives of oppressed noblewomen, and ignore their secretly empowered lower-order sisters. Where poorer women are mentioned, glancingly, they are pitied as prostitutes or rape victims. Even writers who seem desperate for a “feminist take” on the period tend to ignore the angle staring them right in the face. In her 2022 cinematic romp, Catherine called Birdy, for example, Lena Dunham puts Sylvia Pankhurst-esque speeches into the mouth of her 13th-century protagonist, while portraying her impending marriage – at 14 – as normal for the period. (In fact the average 13th-century woman got married somewhere between the ages of 22 and 25.)

But we cling tight to these ideas. It is often those who push back against them who get accused of “historical revisionism”. This applies particularly to the fantasy genre, which aside from the odd preternaturally “feisty” female character, tends to portray the period as, well, a misogynistic fantasy. The Game of Thrones author George RR Martin once defended the TV series’ burlesque maltreatment of women on the grounds of realism. “I wanted my books to be strongly grounded in history and to show what medieval society was like.” Oddly enough, this didn’t apply to female body hair (or the dragons).

This is interesting. Most of our historical biases tend to run in the other direction: we assume the past was like the present. But when it comes to the history of gender relations, the opposite is true: storytellers insist on portraying women as more oppressed than they actually were.

“The history of gender relations might be more accurately painted as a tug of war between the sexes”

The casual reader of history is left with the dim impression that between the Palaeolithic era and the 19th century women suffered a sort of dark age of oppression. This is assumed to have ended some time around the invention of the lightbulb, when the idea of “gender equality” sprang into our heads and right-thinking societies set about “discovering” female competencies: women – astonishingly – could do

things men could do!

In fact the history of gender relations might be more accurately painted as a tug of war between the sexes, with women sometimes gaining and sometimes losing power – and the stronger sex opportunistically seizing control whenever it had the means.

In Minoan Crete, for example, women had similar rights and freedoms to men, taking equal part in hunting, competitions, and celebrations.

But that era ushered in one of the most patriarchal societies the planet has ever known – classical Greece, where women had no political rights and were considered “minors”.

Or take hunter-gatherer societies, the source of endless cod-evolutionary theories about female inferiority. The discovery of female skeletons with hunting paraphernalia has disproved the idea that men only hunted and women only gathered – and more recently anthropologists have challenged the idea that men had higher status too: women, studies contend, had equal sway over group decisions.

This general bias has had two unfortunate consequences. One is to impress upon us the idea that inequality is “natural”. The other is to give us a certain complacency about our own age: that feminist progress is an inevitable consequence of passing time. “She was ahead of her time,” we say, when a woman seems unusually empowered. Not necessarily.

Two years ago, remember, sprang up one of the most vicious patriarchies in history – women were removed from their schools and places of work and battoned into homes and hijabs. And last year in the US many women lost one of their fundamental rights: abortion. (Turns out it was pro-lifers, not feminists, who were ahead of their time there.)

Both these events were greeted with shock from liberal quarters: how could women’s rights be going backwards? But that only shows we should brush up on our history. Another look at medieval women is as good a place to start as any.

Martha Gill is a political journalist and former lobby correspondent

#Women’s History#books for women#The Once and Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society#Eleanor Janega#The Wife of Bath: A Biography#Marion Turner

752 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Neither a straightforward biography nor a modern summation of William of Auvergne’s philosophical and theological works, Lesley Smith’s new biography offers something much richer: the reconstruction of the life, thoughtworld, and audiences of William of Auvergne (d. 1249) from the massive surviving corpus of his sermons and scholarly works. . . . an immersive plunge into the fascinating world of late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century France. This book should inspire scholars and advanced undergraduate and graduate students interested in microhistory, biography, and the integration of intellectual and social history."

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

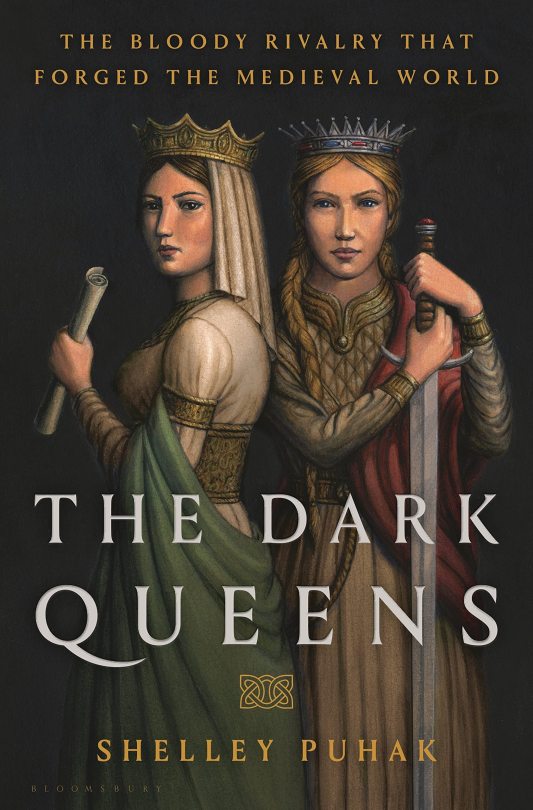

Title: The Dark Queens: The Bloody Rivalry That Forged the Medieval World

Author: Shelley Puhak

Series or standalone: standalone

Publication year: 2022

Genres: nonfiction, history, biography, feminism

Blurb: Brunhild was a Spanish princess, raised to be married off for the sake of alliance-building; her sister-in-law Fredegund started out as a lowly palace slave. And yet - in the 6th-century Merovingian Empire, where women were excluded from noble succession and royal politics was a blood sport - these two iron-willed strategists reigned over vast realms for decades, changing the face of Europe. The two queens commanded armies and negotiated with kings and popes; they formed coalitions and broke them; mothered children and lost them. They fought a years-long civil war against each other. With ingenuity and skill, they battled to stay alive in the game of statecraft, and in the process, laid the foundations of what would one day be Charlemagne’s empire. Yet, after Brunhild and Fredegund’s deaths - one gentle, the other horrific - their stories were rewritten, their names consigned to slander and legend.

#the dark queens the bloody rivalry that forged the medieval world#shelley puhak#standalone#2022#nonfiction#history#biography#feminism

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Article "Edward IV"

The fifteenth century English civil war that became known as the "Wars of the Roses" arose out of tension between the rival houses of Lancaster and York. Both dynasties could trace their ancestry back to Edward III. Both vied for influence at the court of the Lancastrian King Henry VI. The growing enmity that existed between these two noble lineages eventually led to a pattern of political manoeuvring, backstabbing, and bloodshed that culminated in a contest for the crown and Edward of York’s seizure of the throne to become Edward IV, first Yorkist King of England.

Born at Rouen on April 28, 1442, Edward was the eldest son of Richard, Duke of York, and Cecily Neville, "The Rose of Raby". Dubbed “The Rose of Rouen” due to his fair features and place of birth, Edward sported golden hair and an athletic physique. Growing to over six feet tall, the young Earl of March developed into the conventional medieval image of a military leader, ever ready to enter the fray. Intelligent and literate, Edward could read, write, and speak English, French, and a bit of Latin. He enjoyed certain chivalric romances and histories as well as the more physical aristocratic pursuits of hunting, hawking, jousting, feasting, and wenching. Edward proved time and again to be a valiant warrior and competent commander, personally brave and at the same time capable of understanding the finer points of strategy and tactics. As king, he displayed a direct straightforwardness and lacked much of the devious cunning exhibited by some of his contemporaries.

Young Edward of March became embroiled in the dynastic struggle between the Houses of Lancaster and York while still a teen. The family feud erupted into violence for the first time on May 22, 1455, when Yorkist forces under command of the Duke of York and the Earl of Warwick, and Lancastrian forces under command of the Duke of Somerset and King Henry, came to blows on the streets of St. Albans. After a disastrous debacle at Ludford Bridge on October 12, 1459, the Yorkist leaders fled for Calais and Ireland. Edward, Earl of March, was among those declared guilty of high treason by an Act of Attainder passed by Parliament on November 20.

In the summer of 1460, the Earl of March sailed from Calais to Sandwich with the Earls of Salisbury and Warwick and two-thousand men-at-arms. During Edward’s first proper taste of battle at Northampton in July of that year, he and the Duke of Norfolk co-commanded the vanguard that eventually breached the Lancastrian field fortifications, thanks in part to the traitorous actions of the Lancastrian turncoat Lord Grey of Ruthyn. After the Yorkist victory at Northampton, Edward’s father returned to England and made clear his desire to become king, but the assembled lords failed to support his claim.

With the contest between Lancaster and York still undecided, Edward was given his first independent command. He was sent to Wales to quell an uprising led by Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke, while his father marched out of London to tackle the northern allies of Henry VI’s Queen Margaret of Anjou. Drawn out of Sandal Castle by the appearance of a Lancastrian army, Richard of York fell in battle outside its walls on December 30, 1460. His severed head, along with those of his younger son Edmund, the Earl of Rutland, and Richard Neville, the Earl of Salisbury, soon adorned spikes atop the city of York’s Micklegate Bar. A paper crown placed on his bloody pate mocked the Duke’s failed bid for the throne. On the site of his father's death, Edward later erected a simple memorial consisting of a cross enclosed by a picket fence.

Now Duke of York, Edward gathered an army in the Welsh marches to avenge the deaths of his father and younger brother. Having spent his boyhood in Sir Richard Croft’s castle near Wigmore, Edward was well known in the region. He made ready to march toward London to support the Earl of Warwick, but then turned north to face an enemy force led by the Earls of Pembroke and Wiltshire. A strange sight greeted the anxious Yorkist troops at Mortimer's Cross that frosty dawn of February 2, 1461. Three rising suns shone in the morning sky. Quick to declare this meteorological phenomenon a positive omen, Edward announced that the Holy Trinity was watching over his army. After his victory at Mortimer’s Cross, Edward added the sunburst to his banner and badge. To make clear that the conflict had entered a more savage phase, Edward ordered the execution of Owen Tudor and nine other captured Lancastrian nobles. Tudor’s severed head went on display on the market cross at Hereford, where a mad woman combed his hair, washed his bloody face, and lit candles around the grisly memorial.

On February 17, the Earl of Warwick suffered his first defeat at the second battle St. Albans, brought about in part by treachery within his ranks. However, London refused to open its gates to Queen Margaret’s looting Lancastrian army, a force the citizens of the capital feared was full of northern savages. Reunited with King Henry, but frustrated by London’s mistrustful citizenry, the queen withdrew her forces toward York. Warwick and what troops he had left then met up with the victorious Edward at either Chipping Norton or Burford on February 22.

Greeted by cheers, Edward and the Earl of Warwick, marched into the capital on February 26. Warwick’s brother, the Chancellor George Neville, asked the people who they wished to be King of England and France. They answered with shouts for Edward. On March 4, 1461, the Duke of York rode from Baynard’s Castle to Westminster, where the Yorkist peers and commons and merchants of London formally proclaimed him King Edward IV.

The new Yorkist king’s official coronation was postponed while he prepared to set out in pursuit of Margaret and Henry. After sending Lord Fauconberg northward at the head of the king’s footmen on the 11th, Edward marched out of the capital on the 13th. He issued orders prohibiting his army from committing robbery, sacrilege, and rape upon penalty of death. He followed the trail of pillaged towns and razed homesteads left behind by Margaret’s northern moss-troopers.

On March 22, Edward received word that his enemies had taken up position behind the River Aire. On March 28, his vanguard tangled with a Lancastrian force holding the wooden span at Ferrybridge. Outflanking the defenders by sending a part of his army across the Aire at Castleford, Edward managed to push his men across the bridge and up the Towton road.

The two armies drew up in battle order on a snowy Palm Sunday, March 29, 1461. At some point during the morning the snow shifted, blowing into the faces of the Lancastrian soldiers. Taking advantage of the favourable wind, Fauconberg ordered his archers forward. The ensuing volley initiated the biggest, bloodiest, and most decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses.

Edward displayed steadfast courage as the battle raged. The young king rode up and down the line and joined in the melee whenever the ranks appeared ready to waver. No quarter was given, for both sides wished to settle the issue once-and-for-all, and the dead piled up between the opposing men-at-arms. At times, the fighting momentarily ceased while the bodies of the slain were pulled aside to make room for continued bloodshed.

After several hours of fierce fighting, the Yorkist line began to give way. However, the arrival of the Duke of Norfolk’s reinforcements tipped the balance in the Yorkist favour, and the exhausted Lancastrian army eventually faltered and broke. Many fleeing soldiers were cut down by Yorkist prickers in an area now known as Bloody Meadow. As was allegedly his habit when victorious, Edward may have given orders to spare the commons but slay the lords. Those Lancastrian nobles that survived the slaughter, along with King Henry, Queen Margaret, and their son Prince Edward, sought sanctuary in Scotland.

Victory at Towton established the Yorkist dynasty, but over the next three years Edward’s rule still faced a series of Lancastrian-inspired rebellions. Many of these uprisings against the Yorkist crown centred on Lancastrian strongholds in Northumberland. Most of Queen Margaret’s moves in the years immediately following the battle revolved around control of various castles, with some rather dubious aid from the Scots. In 1463, Margaret was finally forced to flee to France when Warwick and his brother routed her Scottish allies at Norham. Left behind by his queen, Henry VI held state in the gloomy fortress at Bamburgh. Warwick besieged this stronghold during the summer of 1464, and it became the first English castle to succumb to cannon fire. Captured in Clitherwood twelve months later and abandoned by his queen and allies, the Lancastrian king was sent to the Tower of London. Edward's throne finally seemed secure. However, Edward next faced threat from an unexpected corner as Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, turned on the man he helped make king.

In 1464, Edward secretly married Elizabeth Woodville, a comparatively lowborn Lancastrian widow. This caused a rift to form between the king and the Earl of Warwick. Edward's in-laws began to exert a growing influence over his court. Displeased with his own waning influence, in 1469 Warwick orchestrated a rebellion in the north. Edward remained in Nottingham while his Herbert and Woodville allies suffered defeat at Edgecote on July 26, 1469. The king then fell under Warwick's protection. On March 12, 1470, Edward was able to rout the rebels at the battle of Losecote Field, a moniker that arose from the fact that many men fleeing the battle discarded their livery jackets displaying the incriminating badges of Warwick and Edward's treacherous brother, the Duke of Clarence. With their treachery made plain, Warwick and Clarence sailed to France and formed an unlikely alliance with Margaret of Anjou. When Warwick returned to England with his new Lancastrian allies, Edward the lost support of the country and fled to the Netherlands. Warwick "The Kingmaker" reinstated the Lancastrian monarch during Henry's Readeption of 1470-1.

Edward IV spent his time in exile assembling an invasion fleet at Flushing and trying to woo his wayward brother back to the Yorkist cause. On March 14, 1471, Edward returned to the realm he claimed as his own, landing at Ravenspur. The Duke of Clarence promptly deserted Warwick and marched to his brother’s aid. Edward headed for London and entered the capital on April 11. Reinforced by Clarence’s troops, Edward took King Henry out of the capital and led a swelling army to face Warwick at Barnet. Edward suffered an early setback as he clashed with his one-time ally on that misty Easter morn of April 14, 1471. The Yorkist left collapsed, and the centre was slowly pushed back, but confusion caused by the obscuring fog eventually doomed Warwick's army. Warwick’s soldiers mistook the star with streams livery worn by the men of the Lancastrian Earl of Oxford for Edward’s sun with streams and loosed volleys of arrows into the approaching troops. With cries of “treason”, Oxford’s men left the field. Sensing the unease that rattled the Lancastrian ranks, Edward rallied his men and pressed the attack. Under this renewed pressure, Warwick’s army wavered and broke. The earl tried to flee the battlefield, but Yorkist soldiers pulled him from his saddle and despatched him with a knife thrust through an eye. Edward arrived on the scene too late to save Warwick from such an ignoble fate.

On May 4, Edward once more led his troops into battle, this time against Queen Margaret’s army at Tewkesbury. Margaret and her son, Prince Edward, had landed at Weymouth with a small force the same day of Edward’s victory over Warwick at Barnet. Under the leadership of the Duke of Somerset, the Lancastrian force moved toward Wales to try to join forces with Jasper Tudor. Wishing to bring Margaret’s army to battle before it crossed the Severn, Edward gave chase. He caught up with Somerset and Margaret at Tewkesbury. Though his army was slightly outnumbered, the Yorkist king once again triumphed over the Lancastrians. Margaret's son, Prince Edward, was captured and slain. Some Lancastrian fugitives, including the Duke of Somerset, tried to seek sanctuary in Tewkesbury Abbey. Dispute surrounds the exact details regarding what happened inside. Edward either granted pardons to those sheltering within the abbey walls, and then reneged on his promise, or he and his men entered the building with swords drawn. Either way, those captives that survived the slaughter were subsequently executed.

With the exception of quickly quelled Kentish and northern revolts, Edward’s triumph at Tewkesbury signalled the end of Lancastrian opposition to his reign. Margaret was captured and brought before Edward on May 12. She remained his prisoner until ransomed by King Louis XI of France. After making his formal entry into London on the 21st, Edward arranged the clandestine murder of poor King Henry VI. Edward’s brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, entered the Tower that evening. By the next morning, Henry, the potential focus of future Lancastrian resistance to Yorkist rule, was dead.

Following his final victory, Edward IV reigned over a relatively stable, peaceful, and prosperous kingdom. Once the Yorkist usurper secured his throne, he showed a ravenous appetite for the opulence of royalty and eventually became rather overweight. As king, he ordered the construction of several grand churches. He was also known as a patron of the arts. A lover of luxury and keenly aware of the political power of a majestic presence, one of Edward’s first acts a few months after his return to the throne was the expenditure of large sums of money on a magnificent new wardrobe. The other crowned heads of Europe all recognized him as legitimate King of England. His brief war with France in 1475 ended when Louis XI agreed to pay Edward an annual subsidy. By 1478 Edward had paid off the debts amassed by his one-time enemies. Unlike many of England’s medieval kings, he died solvent. He introduced several innovations to the machinery of government that the Tudors later adopted and developed. However, his second reign was not without its troubles. Woodville influence over his court caused tension between Edward and the nobility. In 1478, Edward’s in-laws manipulated him into eliminating his disgruntled brother George, the Duke of Clarence. Edward died on April 9, 1483.

Edward of York had a remarkable military career. He personally commanded and fought in five separate battles, and never lost a single one. As a leader of armed men, he often displayed daring and dash. As leader of the Yorkist cause, he exhibited a contradictory mixture of magnanimity and ruthlessness. As king, Edward IV worked to elevate the crown above the nobility and did much to restore a sound government. Unfortunately, his rash marriage bore bitter fruit, sowing the seeds of disaster for his young sons. Edwards’s death in 1483 left a minor as heir. The Duke of Gloucester was named protector of the princes Edward and Richard. Gloucester eventually had his nephews declared bastards and had himself proclaimed King Richard III. His nephews may have been murdered in the Tower, perhaps under Richard’s direct order. Faced with an invasion force led by Henry Tudor, and betrayed by his barons, Richard fell in battle at Bosworth Field. His death marked the end of the Yorkist dynasty and the ascendancy of the Tudors.

The Poleaxe of Edward IV

Being a fierce fighter as well as a skilled commander, Edward was said to be especially proficient with that uniquely knightly pole arm, the poleaxe. A magnificently decorated example currently residing in the Musee de l’Armee in Paris, France, has been ascribed to that most aristocratic of medieval monarchs. The connection to Edward IV is dubious, but this beautiful weapon certainly belonged to some extremely wealthy French, Dutch, or English nobleman of the late fifteenth century. Any consummate warrior and lover of luxury such as Edward of York would certainly have appreciated how the weapon’s combination of fine fighting qualities and rich ornamentation.

Having more reach than a sword, the poleaxe was often the preferred weapon when men of rank fought on foot. Topped by a spike, the axe head was backed by either a hammer or a quadrilateral beak. Mounted on a haft about six feet long and wielded in both hands, the poleaxe could cut, bludgeon, and stab. Even though the example attributed to Edward’s ownership sports fine decorative elements, it still exhibits all the qualities of a functional weapon. A pronged hammer backs a slightly curved axe blade. A wickedly sharp, stout spike thrusts out of the hexagonal central socket. A sturdy rondel acts as a hand-guard.

The lordly embellishments of the Edward IV poleaxe set it apart from simpler period examples. It is profusely decorated with chiselled gilt bronze. The iron components emerge from the throats of stylized beasts. The socket is further decorated with engraved foliage, a knot of flowers, and a cluster of fiery clouds. The rondel takes the form of a full-blown heraldic rose. The assumption that this weapon once belonged to Edward IV arose from the fact that it exhibits the symbols of rose and flame, but such ornamentation was common in the fifteenth century. Still, this imagery does echo the white rose en soliel device Edward used on his banner and badge, so it may just be a weapon once wielded by that accomplished Yorkist warrior.

Sources

Arms and Armour from the 9th to the 17th Century by Paul Martin

Arms and Armour of the Western World by Bruno Thomas

Battle of Tewkesbury 4th May 1471 by P.W. Hammond, H.G. Shearring, and G. Wheeler

Battles in Britain and Their Political Background:1066-1746 by William Seymour

The Book of the Medieval Knight by Stephen Turnbull

Campaign 66: Bosworth 1485: Last Charge of the Plantagenets by Christopher Gravett

Campaign 120: Towton 1461: England's Bloodiest Battle by Christopher Gravett

Campaign 131: Tewkesbury 1471: The Last Yorkist Victory by Christopher Gravett

Men-at-Arms 145: The Wars of the Roses by Terence Wise

The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses by Philip A. Haigh

Who's Who in Late Medieval England by Michael Hicks

#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writers and poets#nonfiction#article#history#medieval#edward iv#military history#biography

0 notes

Text

Jane Boleyn: A Tudor Tale Of Intrigue & Misunderstanding - Part Three

#biographies#historians#historical fiction#history#Jane Boleyn#KING HENRY VIII#MEDIEVAL HISTORY#ROYAL HISTORY#royal women#the tudors#tudor history#world history

0 notes

Text

Lives of church fathers in 1487, printed by Hannibal Foxius. Two North American copies.

658J. Eusebius – Only Two copies in the US

(La vita el transito) Eusebius Cremonensis: Epistola de morte Hieronymi; Aurelius Augustinus, S: Epistola de magnificentiis Hieronymi; Cyrillus: De Miraculis Hieronymi).

[Venice, Hannibal Foxius, 1 June 1487]. $7,000

Octavo 16.7x12cm. Signatures: a–i8. 72 leaves, 36 lines, Roman letter, rubricated with capital letters in red…

View On WordPress

#Church Fathers#early medieval biography#Hannibal Foxius#rare incunabula#St Augustine#St Cryll#St Jerome

0 notes

Text

Kroashent Character Spotlight: Arzhur II

For August/September, I'm taking on a little side project, cleaning up and finishing some of the placeholder characters on the Kroashent WorldAnvil. Oftentimes, inspiration strikes suddenly, leaving me with a lot of unfinished concepts that don't quite fit cleanly into the mix. I'll be returning to answering Q+As soon (questions are always open and welcome) and writing the next chapters of the book. In the meantime, working on a lot of commission work, so this is something of a side project when the tablet is charging.

------------

Val's Notes: Currently, I'm working through two major characters with a lot of stuff attached to them. Aoife, Kathalia's Aunt, has a good deal of source material in her inspiration, and balancing the Irish myths with her Kroashent side has taken a bit of finesse. (Canonically, the mythological Aoife is from Brittany, so the connection works well). More complex is Armel Guyon, a historical figure who features heavily in past events that heavily influence the story. Armel requires a lot of work since he's so important to the story and I'm not sure how much I should reveal.

Arzhur II is a pretty minor ruler of Letha, a guy with a peaceful reign and whose monumental administrative reforms are overshadowed by figures who wage war, poison each other, or fight dragons. Poor, hardworking bureaucrats like Arzhur get overlooked! I may revisit Arzhur II, as he is on the throne after Kathalia is born, but there's not a ton of interesting source material around his historical counterpart. There's some really interesting Franco-English relationship crisis points during the real Arthur II's reign, but not sure how those would translate into Kroashent.

There's also an Arthur I, historically, whose life is overshadowed by some juicy conspiracies, kidnappings and murders. Arzhur I never sat the throne in Kroashent, but his role is still in the air.

0 notes

Text

The Amazing Readathon Week Two

The Amazing Readathon is a readathon created by Brianna from Four Paws and a Book and co-hosted by many others in the BookTube and Bookstagram community. This one is based on the reality TV show The Amazing Race and it’s about spending the month of August travelling the world. There are prompts and ways you can get bonus points (team colour, BIPOC author, etc.). It turns out that we’re not…

View On WordPress

#Agatha Christie#Biography#Books#Eleanor Shearer#Elizabeth Chadwick#England#English History#Francis Walsingham#Henry I#Historical Fiction#Historical Thriller#History#King Stephen#Margaret Owen#Medieval#Mystery#Nancy Goldstone#Queen Matilda#The Amazing Readathon#Thriller

0 notes

Photo

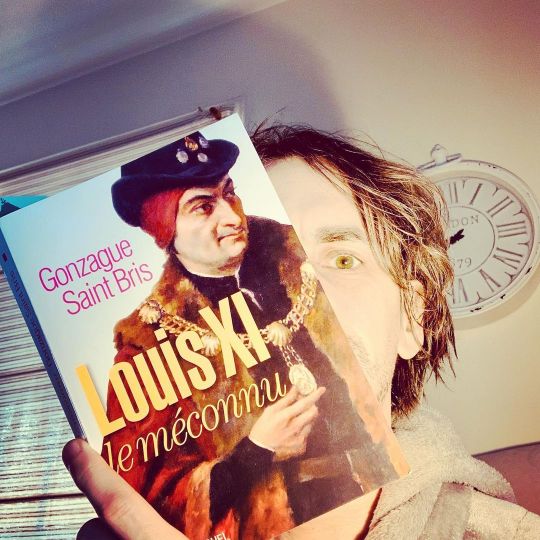

Louis XI Le méconnu. Fascinante histoire du roi de France qui a vu se terminer la guerre de cent ans. Personnage inspirant qui, plus souvent qu’autrement, utilisait la patience et des stratégies pour déjouer ses adversaires. Par son administration intelligente, il annonce l’arrivée de la renaissance. @editionsalbinmichel @albin_michel_canada #lire #lecture #lectureaddict #lecturedumoment #lecturedujour #lectureterminée #delire #lirepourleplaisir #france #roi #roidefrance #medieval #king #louisxi #royauté #francais #biographies #journalisme #renaissance #litterature #couverture #bouquin #doigts #visage #bookstagram #books #book #booklover #bookrecommendations #peinture (at Montreal, Quebec) https://www.instagram.com/p/CnfON-Wv_z8/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#lire#lecture#lectureaddict#lecturedumoment#lecturedujour#lectureterminée#delire#lirepourleplaisir#france#roi#roidefrance#medieval#king#louisxi#royauté#francais#biographies#journalisme#renaissance#litterature#couverture#bouquin#doigts#visage#bookstagram#books#book#booklover#bookrecommendations#peinture

0 notes

Text

Since my big Languages and Linguistics MEGA folder post is approaching 200k notes (wow) I am celebrating with some highlights from my collection:

Africa: over 90 languages so far. The Swahili and Amharic resources are pretty decent so far and I'm constantly on the lookout for more languages and more resources.

The Americas: over 100 languages of North America and over 80 languages of Central and South America and the Caribbean. Check out the different varieties for Quechua and my Navajo followers are invited to check out the selection of Navajo books, some of which are apparently rare to come by in print.

Ancient and Medieval Languages: "only" 18 languages so far but I'm pretty pleased with the selection of Latin and Old/Middle English books.

Asia: over 130 languages and I want to highlight the diversity of 16 Arabic dialects covered.

Australia: over 40 languages so far.

Constructed Languages: over a dozen languages, including Hamlet in the original Klingon.

Creoles: two dozen languages and some materials on creole linguistics.

Europe: over 60 languages. I want to highlight the generous donations I have received, including but not limited to Aragonese, Catalan, Occitan and 6 Sámi languages. I also want to highlight the Spanish literature section and a growing collection of World Englishes.

Eurasia: over 25 languages that were classified as Eurasian to avoid discussions whether they belong in Europe or Asia. If you can't find a language in either folder it might be there.

History, Culture, Science etc: Everything not language related but interesting, including a collection of "very short introductions", a growing collection of queer and gender studies books, a lot on horror and monsters, a varied history section (with a hidden compartment of the Aubreyad books ssshhhh), and small collections from everything like ethnobotany to travel guides.

Jewish Languages: 8 languages, a pretty extensive selection of Yiddish textbooks, grammars, dictionaries and literature, as well as several books on Jewish religion, culture and history.

Linguistics: 15 folders and a little bit of everything, including pop linguistics for people who want to get started. You can also find a lot of the books I used during my linguistics degree in several folders, especially the sociolinguistics one.

Literature: I have a collection of classic and modern classic literature, poetry and short stories, with a focus on the over 140 poetry collections from around the world so far.

Polynesia, Micronesia, Melanesia: over 40 languages and I want to highlight the collection for Māori, Cook Islands Māori and Moriori.

Programming Languages: Not often included in these lists but I got some for you (roughly 5)

Sign Languages: over 30 languages and books on sign language histories and Deaf cultures. I want to highlight especially the book on Martha's Vineyard Sign Language and the biography of Laura Redden Searing.

Translation Studies: Everything a translation student needs with a growing audiovisual translation collection

And the best news: the folders are still being updated regularly!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

“This evocative book, both solidly documented and full of original ideas, renews studies on Eleanor of Aquitaine. Reading medieval and modern texts on the queen with finesse and respect, Sullivan takes us into the mentality of their authors, whose interests, sensibilities, and values are at once so close to and yet so far from ours. Piercing the silence that surrounds women of the twelfth century, this book opens the door to a culture of gender so often forgotten.”

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHAPPELL ROAN at the 2024 MTV Video Music Awards

In the past century in particular, Joan has come to be for many a feminist and queer icon, with Vita Sackville-West first putting forth speculation about Joan’s sexuality in her provocative 1936 biography Saint Joan of Arc. Sackville-West’s Saint Joan represents a landmark moment in queer history, and it is undeniable that Joan’s refusal to conform to medieval conceptions of female propriety and the persecution suffered due to preference for traditionally male clothing have contributed to Joan’s legacy as the essence of transgressive androgyny [...]

Soldier or martyr, patron saint or witch, hero or heretic – whoever Joan truly was, perhaps the most accurate descriptor is simply ‘icon.’ - Evey Reidy (Who was Joan of Arc?)

#chappell roan#joan of arc#roan of arc#chappellroanedit#chappellsource#mtv vmas#2024 vmas#lgbtq#lgbtqedit#lesbian#myedit#p: chappell roan

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pentiment's Complete Bibliography, with links to some hard-to-find items:

I've seen some people post screenshots of the game's bibliography, but I hadn't found a plain text version (which would be much easier to work from), so I put together a complete typed version - citation style irregularities included lol. I checked through the full list and found that only four of the forty sources can't be found easily through a search engine. One has no English translation and I'm not even close to fluent enough in German to be able to actually translate an academic article, so I can't help there. For the other three (a museum exhibit book, a master's thesis, and portions of a primary source that has not been entirely translated into English), I tracked down links to them, which are included with their entries on the list.

If you want to read one of the journal articles but can't access it due to paywalls, try out 12ft.io or the unpaywall browser extension (works on Firefox and most chromium browsers). If there's something you have interest in reading but can't track down, let me know, and I can try to help! I'm pretty good at finding things lmao

Okay, happy reading, love you bye

Beach, Alison I. Women as Scribes: Book Production and Monastic Reform in Twelfth-Century Bavaria. Cambridge Univeristy Press, 2004.

Berger, Jutta Maria. Die Geschichterder Gastfreundschaft im hochmittel alterlichen Monchtum: die Cistercienser. Akademie Verlag GmbH, 1999. [No translation found.]

Blickle, Peter. The Revolution of 1525. Translated by Thomas A. Brady, Jr. and H.C. Erik Midelfort. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985.

Brady, Thomas A., Jr. “Imperial Destinies: A New Biography of the Emperor Maximilian I.” The Journal of Modern History, vol 62, no. 2., 1990. pp.298-314.

Brandl, Rainer. “Art or Craft: Art and the Artist in Medieval Nuremberg.” Gothic and Renaissance Art in Nuremberg 1300-1550. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986. [LINK]

Byars, Jana L., “Prostitutes and Prostitution in Late Medieval Bercelona.” Masters Theses. Western Michigan University, 1997. [LINK]

Cashion, Debra Taylor. “The Art of Nikolaus Glockendon: Imitation and Originality in the Art of Renaissance Germany.” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, vol 2, no. 1-2, 2010.

de Hamel, Christopher. A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. Phaidon Press Limited, 1986.

Eco, Umberto. The Name of the Rose. Translated by William Weaver. Mariner Books, 2014.

Eco, Umberto. Baudolino. Translated by William Weaver. Mariner Books, 2003.

Fournier, Jacques. “The Inquisition Records of Jacques Fournier.” Translated by Nancy P. Stork. Jan Jose Univeristy, 2020. [LINK]

Geary, Patrick. “Humiliation of Saints.” In Saints and their cults: studies in religious sociology, folklore, and history. Edited by Stephen Wilson. Cambridge University Press, 1985. pp. 123-140

Harrington, Joel F. The Faithrul Executioner: Life and Death, Honor and Shame in the Turbulent Sixteenth Century. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

Hertzka, Gottfired and Wighard Strehlow. Grosse Hildegard-Apotheke. Christiana-Verlag, 2017.

Hildegard von Bingen. Physica. Edited by Reiner Hildebrandt and Thomas Gloning. De Gruyter, 2010.

Julian of Norwich. Revelations of Divine Love. Translated by Barry Windeatt. Oxford Univeristy Press, 2015.

Karras, Ruth Mazo. Sexuality in Medieval Europe: Doing Unto Others. Routledge, 2017.

Kerr, Julie. Monastic Hospitality: The Benedictines in England, c.1070-c.1250. Boudell Press, 2007.

Kieckhefer, Richard. Forbidden rites: a necromancer’s manual of the fifteenth century. Sutton, 1997.

Kuemin, Beat and B. Ann Tlusty, The World of the Tavern: Public Houses in Early Modern Europe. Routledge, 2017.

Ilner, Thomas, et al. The Economy of Duerrnberg-Bei-Hallein: An Iron Age Salt-mining Center in the Austrian Alps. The Antiquaries Journal, vol 83, 2003. pp. 123-194

Lang, Benedek. Unlocked Books: Manuscripts of Learned Magic in the Medieval Libraries of Central Europe. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008

Lindeman, Mary. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Lowe, Kate. “’Representing’ Africa: Ambassadors and Princes from Christian Africa to Renaissance Italy and Portugal, 1402-1608.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society Sixth Series, vol 17, 2007. pp. 101-128

Meyers, David. “Ritual, Confession, and Religion in Sixteenth-Century Germany.” Archiv fuer Reformationsgenshichte, vol. 89, 1998. pp. 125-143.

Murat, Zuleika. “Wall paintings through the ages: the medieval period (Italy, twelfth to fifteenth century).” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, vol 23, no. 191. Springer, October 2021. pp. 1-27.

Overty, Joanne Filippone. “The Cost of Doing Scribal Business: Prices of Manuscript Books in England, 1300-1483.” Book History 11, 2008. pp. 1-32.

Page, Sophie. Magic in the Cloister: Pious Motives, Illicit Interests, and Occullt Approaches to the Medieval Universe. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013.

Park, Katharine. “The Criminal and the Saintly Body: Autopsy and Dissectionin Renaissance Italy.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol 47, no. 1, Spring 1994. pp. 1-33.

Rebel, Hermann. Peasant Classes: The Bureaucratization of Property and Family Relations under Early Habsburg Absolutism, 1511-1636. Princeton University Press, 1983.

Rublack, Ulinka. “Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Female Body in Early Modern Germany.” Past & Present,vol. 150, no. 1, February 1996.

Salvador, Matteo. “The Ethiopian Age of Exploration: Prester John’s Discovery of Europe, 1306-1458.” Journal of World History, vol. 21, no. 4, 2011. pp.593-627.

Sangster, Alan. “The Earliest Known Treatise on Double Entry Bookkeeping by Marino de Raphaeli.” The Accounting Historians Journal, vol. 42, no. 2, 2015. pp. 1-33.

Throop, Priscilla. Hildegarde von Bingen’s Physica: The Complete English Translation of Her Classic Work on Health and Healing. Healing Arts Press, 1998.

Usher, Abbott Payson. “The Origins of Banking: The Brimitive Bank of Deposit, 1200-1600.” The Economic History Review, vol. 4, no. 4. 1934. pp.399-428.

Waldman, Louis A. “Commissioning Art in Florence for Matthias Corvinus: The Painter and Agent Alexander Formoser and his Sons, Jacopo and Raffaello del Tedesco.” Italy and Hungary: Humanism and Art in the Early Renaissance. Edited by Peter Farbaky and Louis A. Waldman, Villa I Tatti, 2011. pp.427-501.

Wendt, Ulrich. Kultur and Jagd: ein Birschgang durch die Geschichte. G. Reimer, 1907.

Whelan, Mark. “Taxes, Wagenburgs and a Nightingale: The Imperial Abbey of Ellwangen and the Hussite Wars, 1427-1435.” The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, vol. 72, no. 4, 2021, pp.751-777.

Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Yardeni, Ada. The Book of Hebrew Script: History, Palaeography, Script Styles, Calligraphy & Design. Tyndale House Publishers, 2010.

420 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eleanor, the Queen: Defending Monks and Clergy in Medieval England

View On WordPress

#biographies#Eleanor Of Aquitaine#Eleanor of Aquitaine&039;s Advocacy for Clergy&039;s Rights#history#late middle ages#Medieval England#MEDIEVAL HISTORY#Monks&039; Land Rights#Queen Eleanor&039;s Defense of Monks&039; Land Rights in Medieval London#Queen Eleanor&039;s Support for Monks and Pope Alexander III#ROYAL HISTORY#royal women

0 notes

Text

Lives of church fathers in 1487, printed by Hannibal Foxius. Two North American copies.

658J. Eusebius – Only Two copies in the US

(La vita el transito) Eusebius Cremonensis: Epistola de morte Hieronymi; Aurelius Augustinus, S: Epistola de magnificentiis Hieronymi; Cyrillus: De Miraculis Hieronymi).

[Venice, Hannibal Foxius, 1 June 1487]. $7,000

Octavo 16.7x12cm. Signatures: a–i8. 72 leaves, 36 lines, Roman letter, rubricated with capital letters in red…

View On WordPress

#Church Fathers#early medieval biography#Hannibal Foxius#rare incunabula#St Augustine#St Cryll#St Jerome

0 notes

Text

A very detailed character biography to help build characters. I found the original template HERE and edited it to make it more suitable for the characters I'm creating, and also to add some more details, such as a mental illness checklist section to use for myself to reference (because it helps to know what's wrong with your characters) and other details. You may not need so many minor details for a character, but you never know if you'll end up needing an explanation for something. I'll be using this template myself so I figured I'd share it in case it could help others too. I have edited it to better suit my own medieval fantasy characters, so I'm not sure how well it will work with other genres. Enjoy. ♡

☆Trigger Warning - Sensitive Mental Health Topics☆

Character 1

• Character’s full name:

• Reason or meaning of name:

• Character’s nickname:

• Reason for nickname:

• Character’s titles & what they mean:

• Birth date/season:

Physical appearance

• Age:

• Appears how old:

• Race:

• Gender:

• Weight:

• Height:

• Body build:

• Shape of face:

• Eye color:

• Skin tone:

• Distinguishing marks:

• Predominant features:

• Hair color:

• Hair type:

• Usual hairstyle:

• Voice:

• Overall 1-10 attractiveness scale:

• Physical disabilities:

• Usual fashion:

• Favorite outfit:

• Jewelry or accessories:

• Tattoos:

• Miscellaneous:

Personality

• Good personality traits:

• Bad personality traits:

• Most common mood:

• Sense of humor:

• Greatest joy in life & why:

• Greatest fear & why:

• What event would be most devastating & why:

• Most comfortable when:

• Most uncomfortable when:

• Most angry/furious when:

• Most depressed/sad when:

• Most happy/joyful when:

• Priorities:

• Life philosophy:

• Biggest wish & why:

• Character’s soft spot:

• Is this soft spot obvious to others or common:

• Political views:

• Greatest strength:

• Greatest weakness:

• Greatest vulnerability:

• Biggest regret:

• Minor regret:

• Biggest accomplishment:

• Minor accomplishment:

• Most embarrassing event & why:

• Character’s darkest secret, if any:

• Does anyone else know this secret:

• Miscellaneous:

Goals & Dreams

• Drives/Motivations:

• Immediate goals:

• Long term goals:

• How to accomplish the goals:

• How others will be affected if the goals are achieved:

• How long has character had the goals:

• Goals that character thinks are hard to achieve:

• Goals that character thinks are easy to achieve:

• Goals that character has already started working on & how long:

• Dreams:

• Miscellaneous:

Past

• Location of birth/childhood:

• Socioeconomic status:

• Cultural traditions:

• Parents Socioeconomic ranking:

• Parents involvement:

• Type of childhood:

• Siblings/other family involvement:

• Friends/Acquaintances:

• First memory:

• Most important memory & why:

• Childhood hero:

• Pets:

• Dream job:

• Education:

• Religion:

• Wealth/inheritances:

• Miscellaneous:

Present

• Current location:

• Currently living with:

• Type of residence & who owns it:

• Possessions/Owned assets:

• Weapons owned:

• Socioeconomic ranking & how it was achieved:

• Cultural traditions/practices:

• Religion:

• Sexual orientation:

• Occupation:

• Wealth:

• Acquaintances/Friends/Lovers:

• Pets:

• Miscellaneous:

Family

• Mother:

▪︎Alive or Deceased:

▪︎Relationship with her:

• Father:

▪︎Alive or Deceased:

▪︎Relationship with him:

• Siblings:

▪︎Alive or Deceased:

▪︎Relationship with them:

• Spouse:

▪︎Alive or Deceased:

▪︎Relationship with him/her:

• Children:

▪︎Alive or Deceased:

▪︎Relationship with them:

• Other important family members:

▪︎Alive or Deceased:

▪︎Relationship with them:

Favorites

• Color:

• Food:

• Form of entertainment:

• Story/Myth/Legend:

• Mode of transportation:

• Most prized possession:

• Location/place:

• Season/weather:

• Miscellaneous:

Habits & Activities

• Hobbies:

• Training:

• Magical/special abilities:

• How he/she would spend a rainy day:

• Spending habits:

• Smokes tobacco:

• Drinks:

• Drugs/herbs:

• Activity does too much of:

• Activity does too little of:

• Extremely skilled at:

• Slightly skilled at:

• Extremely unskilled/terrible at:

• Nervous tics:

• Usual body posture:

• Mannerisms:

• Peculiarities:

• Places visited for fun/interest:

• Miscellaneous habits:

• Miscellaneous activities:

Traits & Flaws

• Optimist or pessimist:

• Introvert or extrovert:

• Daredevil or cautious:

• Logical or emotional:

• Disorderly/Messy or Methodical/Neat:

• Prefers working or relaxing:

• Confident or unsure:

• Easy to anger:

• Easily pleased:

• Manipulative:

• Apologetic:

• Accepting of advice:

• Easily bored:

• Mentally/Emotionally strong:

• Accountability:

• Ambitious:

• Work ethic:

• Demanding & bossy:

• Submissive & subordinate:

• Playful or boring:

• Brave or cowardly:

• Chases power/success/glory:

• Protective of loved ones:

• Doubts themselves or others:

• Talkative or quiet:

Mental Illnesses

• Trauma & why/who/what/when:

• Addictions:

• Depression:

• Anxiety:

• Paranoia:

• Hallucinations:

• Personality disorder:

• PTSD:

• Obsessive compulsive:

• Bipolar:

• Stable:

• Triggers:

• Miscellaneous:

Self-perception

• Feelings about himself/herself:

• One word the character would use to describe self:

• One paragraph description of how the character would describe self:

• Character considers their best personality trait:

• Character considers their worst personality trait:

• Character considers their best physical characteristic:

• Character considers their worst physical characteristic:

• Character thinks others perceive them:

• Character's aspect they would change about themself:

• Miscellaneous:

Relationships with others

• Opinion of people in general:

• Does the character hide opinions/emotions from others:

• Most hated/Biggest enemy & why:

• Most loved & why:

• Best friend(s):

• Love interest(s):

• Who to go to for advice:

• Who they're responsible for/Who they take care of:

• Who character feels shy or awkward around:

• Who character openly admires:

• Who character secretly admires:

• Most important in character’s life before story starts:

• Most important after story starts:

• Opinion of relationships with family:

• Opinion of relationships with lovers:

• Opinion of relationships with friends:

• Treats strangers:

• Treats authority figures:

• Opinions of authority figures:

• Treats subordinates:

• Opinions of subordinates:

• Treats the opposite gender:

• Opinions of the opposite gender:

• Treats other races/cultures:

• Opinions of other races/cultures:

• Treats children:

• Opinions of children:

• Treats others with different tastes/interests/activities:

• Opinions of others with different tastes/interests/activities:

• How they treat others who admire them:

• How they treat others who love them:

• How they treat others who betray/harm/bully them:

• How they treat others who disrespect/harm others:

• How they react when someone needs their help:

• How they react when someone tries to help them:

• How they react to sexual/romantic advances:

• Opinions of sex & brothels:

• Miscellaneous:

#character creation#character traits#character building#character analysis#character design#character development#character writing#writing characters#fictional characters#character sheet#character bio#character concept#character backstory#character template#character bio template#character building template#writing tips#writing inspiration#writing prompt#novel writing#writing#creative writing#fantasy writing#writing advice#writing ideas#writing resources#writing motivation#writing community#author tips#aspiring author

2K notes

·

View notes