#paul theroux

Text

Book Review

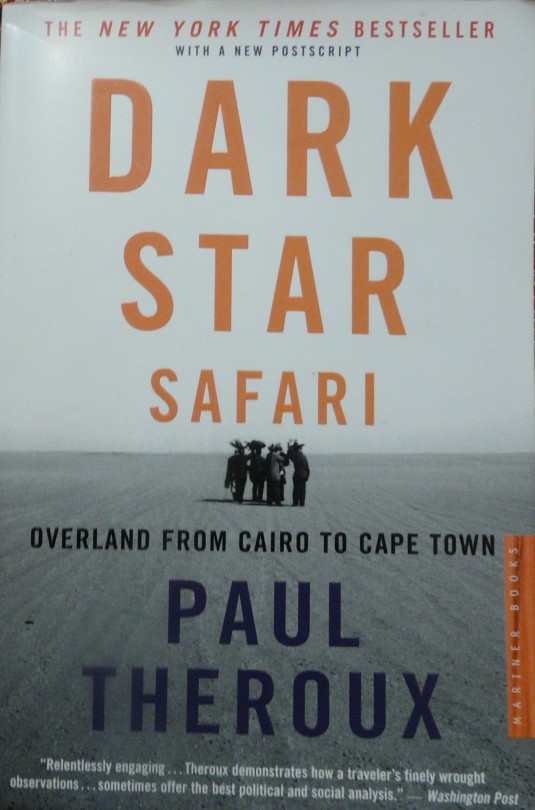

Dark Star Safari: Overland from Cairo to Cape Town

by Paul Theroux

Two decades ago, the novelist and travel writer Paul Theroux took an overland trip through Africa, starting in Cairo, Egypt and ending in Cape Town, South Africa. This certainly isn’t the safest or the most comfortable means of experiencing the supposed “dark continent”, but it makes for some interesting experiences and insights. Keeping in mind that Theroux’s observations are just one point of view among many, his resulting book Dark Star provides a unique look at a region of the world that holds a permanent place off the beaten path.

While Dark Star is an easy book to read, breaking it down into its individual elements is a good way to approach its merits and examine its flaws. The first element of importance is Theroux’s sense of place. Wherever he goes, the author describes what he sees and the vibe he gets from his surroundings. Starting on the tourist trail in Egypt, he heads south through Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Zambia, and South Africa. You quickly get a sense of what he appreciates and what he doesn’t. He doesn’t like sites that are swarmed with tourists, nor does he like cities with their concentrations of crime and poverty. He also doesn’t like the “death traps” as he calls public transportation which are usually over-croded minivans driven at dangerous speeds on poorly maintained roads, pockmarked with hippopotamus-sized potholes. If you’ve ever traveled in a Third World country, you will know exaclt what he is talking about.

The places that Theroux does like are usually rural, especially farm lands or jungle villages. These are the places where he sees Africans at their best, meaning Africans being Africans in the absence of corrupt and filthy cities built up on the foundations of European colonialism. Some of the book’s best passages involve descriptions of the pyramids in Sudan which are rarely seen by tourists, a boat trip across Lake Victoria, another boat trip from Malawi across the Zambezi over the border into Zimbabwe, and the pristine countrysides of Zimbabwe and South Africa. All places, whether Theroux likes them or not, are described with language that is clear, simple, and direct, making it easy to visualize what he sees.

Another element that is done to near perfection is writings about the people. Theroux talks with tour guides, people on the streets and in the villages, farmers, nuns, educators, government officials, Indian businessmen, prostitutes, authors, intellectuals, and ordinary people. Just like with the places he goes, he describes these people vividly with precision so that you feel like you quickly get to know them. But not everyone is to his liking. He gets into small argument with a fanatical Rastafarian in Ethiopia, a little ornery with physically fit young men who refuse to work, government officials who demand bribes to do their jobs, and he really gives a hard time to a young American missionary woman about the psychological damage that her evangelical ministry is doing to the local people. There is also plenty of anger directed at clueless tourists as well as NGO and charity workers who he sees as being the Westerners who do the most damage to Africa.

The third element of importance is the author, Paul Theroux himself, and his thoughts and commentaries on everything he sees. Before getting into this subject, it should be mentioned that Theroux had a purpose to his journey. In the 1960s he worked as a Peace Corps volunteer, teaching in Malawi. After getting involved with a Leftist political group, he got fired then accepted a teaching position at a college in Uganda. He wanted to return and see what results, if any, his contributions to Africa grew into. What he found was a major disappointment. The charming campuses and villages where he had lived were in ruins and instead of a thriving civilization, he saw emaciated beggars, starving children, an ignorant populace, and chronically corrupt politicians. Shops that were formerly owned by Indian immigrants were abandoned and burnt to the ground, the result of a campaign of ethnic cleansing. African people wanted to buy from shops owned by Africans, but Africans never took control over the businesses after the Indians were killed or chased away. They resorted to begging, theft, petty crime, prostitution, and laziness instead of making an effort to build better villages for themselves. Due to the hopelessness of African society, the most educated citizens fled to America or Europe instead of staying in their home countries where they were most needed.

Throughout his travels in Tanzania, Uganda, and Malawi, Theroux gets increasingly bitter and cynical. He wanted to see Africans thriving and they weren’t. He directs all his wrath towards the Western charities and NGOs who he says are making the local people dependent on aid rather than learning how to run their societies for themselves. Even worse, these organizations work by bribing corrupt politicians to allow them to do work there, keeping greedy and psychotic leaders in positions of power they don’t deserve. Theroux points out that rural people who have given up on the hopeless market economy and returned to subsistence farming are the happiest and healthiest Africans he encounters. Heecomes close to advocating for a type of post-capitalist agrarian anarchism.

Some readers have criticized Theroux for his pessimistic views on contemporary Africa, but he does cite studies that support what he says. He also encounters a lot of Africans in several different countries that agree with him. To make sense of his negativity, you also have to remember that traveling overland through Africa is not exactly stress free. Anybody who has been on an extended backpacking trip anywhere in the world will tell you that traveler’s fatigue is a real thing. Theroux took a longer than average trip through one of the most underdeveloped regions in the world, got shot at by Somali bandits, stuck in the middle of nowhere when his transportation broke down, and got sick with food poisoning, magnifying his traveler’s fatigue to a outsize extent. These circumstances would make you grouchy too. But even in the darkest times, Theroux never loses his appreciation for Africa, the wildlife, the landscapes, and the people who are trying to make the best of their situations. Besides, by the time he crosses the river from Malawi into Zimbabwe, his mood really lightens up.

Dark Star is an engaging travelogue that should be read both critically and with an open mind. All the while, remember that this is Paul Theroux’s singular point of view. That doesn’t make it wrong; that just means that there are other points of view to take into account that may go against what he says even if they don’t necessarily invalidate his opinions. He saw what he saw and he expresses it well. This is raw and honest travel writing and if you haven’t been tough enough to make the same kind of journey, you’re not in a good place to be judgmental of the conclusions he draws.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The inner journey of travel is intensified by solitude.” - Paul Theroux.

Navarre Beach, Florida.

Fujifilm X-E3. 23mm f2. Classic Chrome.

Travel, Photography, Books, Music, Gear. Sign up for the Silver Compass Journal Newsletter.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I always thought the choice was mine

And I was right, but I just chose wrong

I start the day lying and end with the truth

That I'm dying for the knife

— ”Working for the Knife” by Mitski

###

"The history of mankind in four words..."

"Mimi nyama, wewe kisu. I’m the meat, you’re the knife."

— "I'm the Meat, You’re the Knife" by Paul Theroux

#working for the knife#mitski#i'm the meat you're the knife#paul theroux#the knife#parallels#music#literature#stories

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ben Gazzara - The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976) / Saint Jack (1979)

Stills

#ben gazzara#the killing of a chinese bookie#saint jack#john cassavetes#peter bogdanovich#1976#1979#1970s#usa#neo noir#frederick elmes#robby muller#roger corman#paul theroux#venice film festival#singapore#china#still

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Le voyage, prévient-il dès les premières pages, est un acte évanescent, la randonnée d'un solitaire le long de l'étroite ligne qui mène de la géographie à l'oubli... Mais le livre de voyage est l'inverse, le solitaire rebondit plus haut que dans la vie pour relater l'histoire de son expérience avec l'espace... C'est le mouvement mis en ordre par sa répétition dans des mots.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bruce Chatwin (1940-1989)

Het is al 35 jaar geleden dat “de Engelse Boudewijn Büch” Bruce Chatwin is overleden.

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#André Malraux#Boudewijn Büch#Bruce Chatwin#Eileen Gray#John Betjeman#Nicholas Shakespeare#Paul Theroux#Robert Mapplethorpe#Salman Rushdie

1 note

·

View note

Text

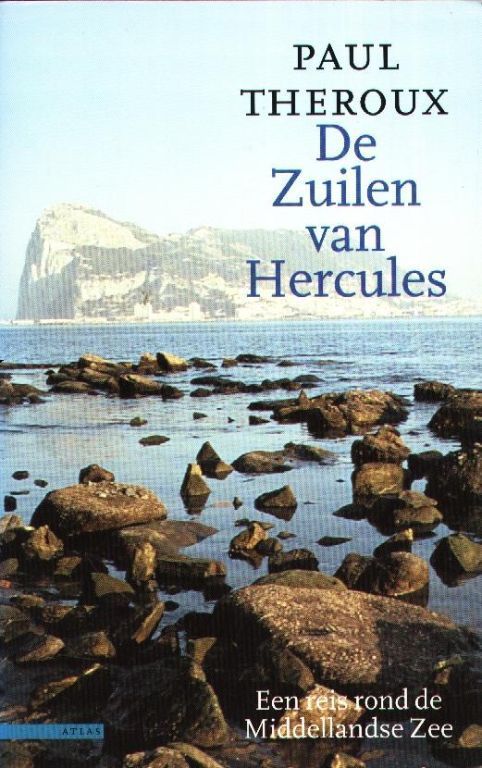

Paul Theroux – De zuilen van Hercules

De reisverhalen van Theroux zijn altijd leuk om te lezen, omdat hij een heerlijke atypische reiziger is. Als iets populair is, zal hij een andere route kiezen. Als hij zich als een local kan gedragen, doet hij dat. Hij slaapt in slechte hotels, zwerft door lelijke buurten en praat met velen om zodoende te weten wat er speelt in een land, niet wat de reisgidsen zeggen wat hij zou moeten zijn.

In…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

© Paolo Dala

The Appreciation Of Decay

It is only with age that you acquire the gift to evaluate decay, the epiphany of Wordsworth, the wisdom of wabi-sabi: nothing is perfect, nothing is complete, nothing lasts.

Paul Theroux

#Paul Theroux#Decay#Wabi-sabi#Buddha#Temple#Still Life#City#Wat Mahathat#Ayutthaya#Thailand#Ancient#History

0 notes

Text

Riding on the Equator

I left Facebook years ago. Myspace long before that. Twitter was my go-to until Elon came along. I have used Tumblr off and on through the years but never really with any gusto.

Now I'm lost in the internet wilderness, looking for a new home - an outlet - and I don't really want to sign up for the latest and greatest social media so here I am giving Tumblr another go.

I also still have Instagram but don't really care for it. I use it to keep up with people I actually know. I also keep up with a few guys in a couple of groups on GroupMe but that whole app seems so outdated and cumbersome and just - not modern I guess. Regardless, I am a latecomer to the established groups mainly discussing soccer and video games. I love soccer but not the league most of them are into. And I'm not a gamer. I sometimes feel when I post about non-gaming things in the non-soccer group, I'm just being a nuisance or treating the group as I would Twitter or Facebook before that - and that's not really what it's for.

So what to do to kill my boredom and write about things I'm in to without resorting to all of the above? Well...welcome to Slow Drives Redux. We'll see how long it lasts.

For my inaugural post I'm gonna keep it short and sweet, unlike the song below which clocks in at a good 9 minutes. It's my favorite song by my favorite band - well, at least one of my favorite bands. It's certainly on my favorite release by them.

youtube

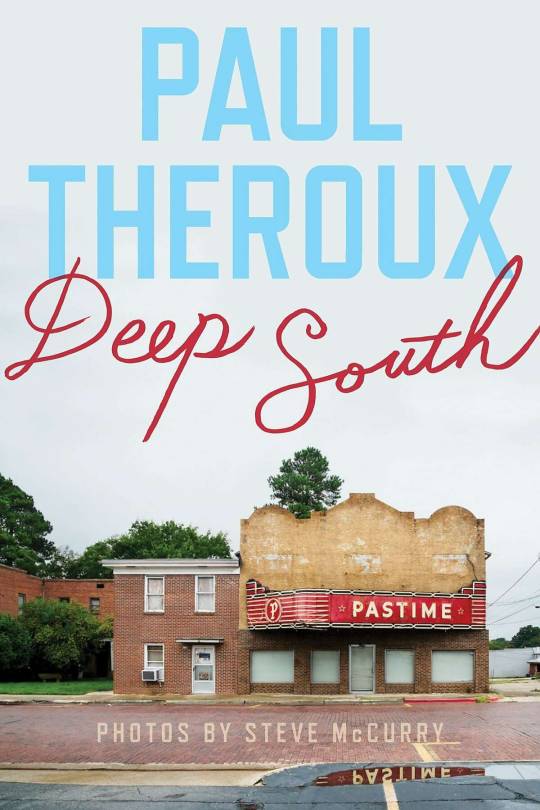

I will also use this post to reccomend a book I'm currently reading. It's a travel book, but there's not much in the way of talking about the journey and hardships of the travel itself, which is refreshing. Having grown up in the deep south, none of it is revelatory, but an interesting read nonetheless.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Boeken over Treinreizen - reizen per trein in je hoofd

Boeken over Treinreizen - reizen per trein in je hoofd

Boeken over treinreizen

In Amsterdam zoals in veel steden en dorpen loop je tegenwoordig in de straten tegen kleine houten bibliotheekjes aan – uitgelezen boeken vinden hier hun plek – niet het eindstation maar een verse kans voor leeshunker – gister vond ik hier op de hoek van de straat De Oude Patagonië expres van Paul Theroux – een fantastisch boek over een treinreis die Theroux in 1997…

View On WordPress

#5 (Nederlandse) bloggers die ook over treinreizen schrijven#boek kopen over treinreizen#boeken over treinreizen#De 8 mooiste treinreizen van Europa#De leukste treinreizen#De Oude Patagonië expres#De Oude Patagonië expres van Paul Theroux#eco reizen#eco reizen per trein#groen reizen#groen reizen per trein#met de trein door Europa#Met de trein door Europa | De mooiste routes op een rij#Paul Theroux#Treinblog#treinboog Europa#treinboog Nederland#Treinreis blog: reis per trein door Europa#treinreis boeken#treinreis europa#treinreisboek Latijns Amserika#treinreisboek zuid amerika#treinreisboeken Europa#Treinreizen binnen Europa vanuit Nederland#Treinrondreizen door Europa - Treinreizen - Liefde voor Reizen

0 notes

Text

Silver Compass Journal’s Winter Reading List - 2023

Purple Deceiver - Buck Reilly #10 - John H. Cunningham

I thought I'd start the winter reading list with a book set in warm, sunny Key West. I really enjoy the fun and exciting Buck Reilly series from John H. Cunningham. Buck is a treasure hunter turned seaplane pilot. These books are Indiana Jones meets Jimmy Buffett.

A Step Beyond Chaos - Alex Rutledge #10 - Tom Corcoran

Another novel set in Key West. This is the 10th book by Tom Corcoran that features the photographer and reluctant crime solver Alex Rutledge. Alex is one of my favorite characters. He tries to live a quiet life in Key West but is constantly pulled into helping KWPD solve murders around the island. If you haven't read these, I recommend starting with the first one 'The Mango Opera' and reading them all.

The Paris Bookseller - Kerri Maher

"The dramatic story of how a humble bookseller fought against incredible odds to bring one of the most important books of the 20th century to the world." This is the story of how Silvia Beach opened the famous Paris bookstore Shakespeare and Company, published James Joyce's Ulysses, and befriended the characters of 1920's Paris including Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Gertrude Stein.

The Search for the Genuine - Jim Harrison

"The first general nonfiction title in thirty years from a giant of American letters, The Search for the Genuine is a sparkling, definitive collection of Jim Harrison's essays and journalism-some never before published." I'm a big fan of Jim Harrison, particularly his non-fiction writing about food, wine, hunting, fishing, travel, and life.

The Great Railway Bazaar - Paul Theroux

"In 1973, Paul Theroux embarked on a four-month journey by train from the United Kingdom through Europe, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. In The Great Railway Bazaar, he records in vivid detail and penetrating insight the many fascinating incidents, adventures, and encounters of his grand, intercontinental tour." I'm currently reading his follow up to this book called Ghost Train to the Eastern Star Where he re-visits his journey in The Great Railway Bazaar 30 years later.

0 notes

Text

9 The Kalka Mail for Simla

IN spite of my disheveled appearance, it was thought by some in Delhi to be beneath my dignity to stand line for my my ticket north to Simla, though perhaps this was a tactful way of suggesting that if I did stand in line I might be mistaken for an Untouchable and set alight (these Harijan combustion are reported daily in Indian newspapers). The American official who claimed his stomach was collapsing with dysentery introduced me to Mr Nath, who said, 'Don't sweat. We'll take care of everything.' I had heard that one before. Mr Nath rang his agent. At four o'clock there was no sign of the ticket. I saw Mr Sheth. He offered me tea. I refused his tea and went to the travel agent. This was Mr Sud. He had delegated the ticket buying to one of his clerks. The clerk was summoned. He didn't have the ticket; he had sent a messenger, a low-caste Tamil whose role in life, it seemed, was to lengthen the lines at ticket windows. An Indian story : and still no ticket. Mr Nath and Mr Sud accompanied me to the ticket office, and there we stood ('Are you sure you don't want a nice cup of tea?') watching this damned messenger, ten feet from the window, holding my application. Bustling Indians began cutting in front of him.

‘Now you see,’ said Mr Nath, ‘with your own eyes why things are so backwards over here. But don’t worry. There are always seats for VIPs.’ He explained that compartments for VIPs and senior government officials were reserved on every train until two hours before departure time, in case someone of importance might wish to travel at the last minute. Apparently a waiting list was drawn up every day for each of India’s 10,000 trains.

‘Mr Nath,’ I said, ‘I’m not a VIP.’

‘Don’t be silly,’ he said. He puffed his pipe and moved his eyes from the messenger to me. I think he saw my point because his next words were, ‘Also we could try money.’

‘Baksheesh,’ I said. Mr Nath made a face.

Mr Sud said, ‘Why don’t you fly?’

‘Planes make me throw up.’

‘I think we've waited long enough,’ said Mr Nath. We’ll see the man in charge and explain the situation. Let me do the talking.’

We walked around the barrier to where the ticket manager sat, squinting irritably at a ledger. He did not look up. He said, ‘Yes, what is it?’ Mr Nath pointed his pipe stem at me and, with the pomposity Indians assume when they speak to each other in English, introduced me as a distinguished American writer who was getting a bad impression of Indian Railways.

‘Wait a minute,’ I said.

‘It is imperative that we do our utmost to ensure –’

‘Tourist?’ said the ticket manager.

I said yes.

He snapped his fingers. ‘Passport.’

I handed it over. He wrote a new application and dismissed us. The application went back to the messenger, who had wormed his way to the window.

‘It’s a priority matter,’ said Mr Nath crossly. ‘You are a tourist. You have come all this way, so you have priority. We want to give favourable impression. If I want to travel with my family –– wife, small children, maybe my mother too –– they say, “Oh, no, there is a tourist here. Priority matter!”’ He grinned without pleasure. ‘That is the situation. But you have your ticket –– that's the important thing, isn't it?’

*

The elderly Indian in the compartment was sitting crosslegged on his berth reading a copy of Filmfare. Seeing me enter, he took off his glasses, smiled, then returned to his magazine. I went to a large wooden cupboard and smacked it with my hand, trying to open it. I wanted to hang up my jacket. I got my fingers into the louvered front and tugged. The Indian took off his glasses, and this time he closed the magazine.

‘Please,’ he said, ‘you will break the air conditioner.’

‘This is an air conditioner?’ it was a tall box the height of the room, four feet wide, varnished, silent, and warm.

He nodded. ‘It has been modernized. This carriage is fifty years old.’

‘Nineteen twenty?’

‘About that,’ he said. ‘The cooling system was very interesting then. Every compartment had its own unit. That is a unit. it worked very well.’

I didn't realize there were air conditioners in the twenties,’ I said.

‘They used ice,’ he said. He explained that blocks of ice were slipped into lockers under the floor – it was done from the outside so that the passengers’ sleep would not be disturbed. Fans in the cupboard I had tried to open blew air over the ice and into the compartment. Every three hours or so the ice was renewed. (I imagined an English man snoring in his berth while at the platform of some outlying station Indians with bright eyes pushed cakes of ice into the lockers.) But the system had been converted : a refrigerating device had been installed under the blowers. Just as he finished speaking there was a whirr from behind the louvres and a loud prolonged whoosh !

‘When did they stop using ice?’

‘About four years ago,’ he said. He yawned. ‘You will excuse me if I go to bed?’

The train started up, and the wood paneling of this old sleeping car groaned and creaked; the floor shuddered, the metal marauder-proof windows clattered in their frames, and the whooshing from the tall cupboard went on all night. The Kalka Mail was full of Bengalis, whose complexion resembles that of the black goddess of destruction they worship, and who have the same sharp hoop to their noses, have the misfortune to live at the opposite end of the country from the most favoured Kali temple. Kali is usually depicted wearing a necklace of human skulls, sticking her maroon tongue out, and trampling a human corpse. But the Bengals were smiling sweetly all along the train, with their baskets of food and neatly woven garlands of flowers.

I was asleep when the train reached Kalka at dawn, but the elderly Indian obligingly woke me up. He was dressed and seated on the drop-lead table, having a cup of tea and reading the Chandigarh Tribune. He poured his tea into the cup, blew on it, poured half a cup into the saucer, blew on it, and then, making a pedestal of his fingers, drank the tea from the saucer, lapping it like a cat.

'You will want to read this,' he said. 'Your vice president has resigned.'

He showed me the paper, and there was the glad news, sharing the front page with an item about a Mr Dikshit. It seemed a happy combination, Dikshit and Agnes, though I am sure Mr Dikshit's political life had been blameless. As for Agnew's, the Indian laughed derisively when I translated the amount he had entered into rupees. Even the black-market rate turned him into a cut-price punk. The Indian was in stitches.

In Kalka two landscapes meet. There is nothing gradual in the change from plains to mountains : the Himalayas stand at the upper edge of the Indo-Gangetic plain; the rise is sudden and dramatic. The trains must conform to the severity of the change; two are required - one large roomy one for the ride to Kalka, and a small tough beast for the ascent to Simla. Kalka itself is a well-organized station at the end of the broad-gauge line between the Himalayas and Kalka is the cool hill station of Simla on a bright balding ridge. I had my choice of trains for the sixty-mile journey on the narrow gauge : the toy train or the rail car. The blue wooden carriages of the train were already packed with pilgrims - the Bengals, nimble at boarding trains, had performed the Calcutta trick of diving headfirst through the train windows and had got the best seats. It was an urban skill, this somersault - a fire drill in reverse - and it left the more patient hill people a bit glassy-eyed. I decided to take the rail car. This was a white squarish machine, with the face of a Model-T Ford and the body of an old bus. It was mounted low on the narrow-gauge tracks and had the look of a battered limousine. But considering that it was built in 1925 (so the driver assured me), it was in wonderful shape.

I found the conductor. He wore a stained white uniform and a brown peaked cap that did not fit him. He was sorry to hear I wanted to take the rail car. He ran his thumb down his clipboard to mystify me and said, 'I am expecting another party.'

There were only three people in the rail car. I felt he was angling for baksheesh. I said, 'How many people can you fit in?'

'Twelve,' he said.

'How many seats have been booked?'

He hid his clipboard and turned away. He said, 'I am very sorry.'

'You are very helpful.'

'I am expecting another party.'

'If they show up, you let me know,' I said. 'In the meantime, I'm putting my bag inside.'

'It might get stolen,' he said brightly.

'Nothing could please me more.'

'Wanting breakfast, sahib?' Said a little man with a pushbroom.

I said yes, and within five minutes my breakfast was laid out on an unused ticket counter in the middle of the platform: tea, toast, jam, a cube of butter, and an omelette. The morning sunlight struck through the platform, warming me as I stood eating my breakfast. It was an unusual station for India : it was not crowded, there were no sleepers, no encampments of naked squatters, no cows. it was filled that early hour with the smell of damp grass and wildflowers. I buttered a thick slice of toast and ate it, but I couldn't finish all the breakfast. I left two slices of toast, the jam, and half the omelette uneaten, and I walked over to the rail car. When I looked back, I saw two ragged children reaching up to the counter and stuffing the remainder of my breakfast into their mouths.

At seven-fifteen, the driver of the rail car inserted a long handled crank into the engine and gave it a jerk. The engine shook and coughed and, still juddering and smoking, began to whine. Within minutes we were on the slope, looking down at the top of Kalka Station, where in the train yard two men were winching a huge steam locomotive around in a circle.

The rail car’s speed was a steady ten miles an hour, zigzagging in and out of the steeply pitched hill, revering on switchbacks through the terraced gardens and the white flocks of butterflies. We passed through several tunnels before I noticed they were numbered; a large number 4 was painted over the entrance of the next one. The man seated beside me, who had told me he was a civil servant in Simla, said there were 103 tunnels altogether. I tried not to notice the numbers after that. Outside the car, there was a sheer drop, hundreds of feet down, for the railway, which was opened in 1904, is cut directly into the hillside, and the line above is notched like the skidway on a toboggan run, circling the hills.

After thirty minutes everyone in the rail car was asleep except the civil servant and me. At the little stations along the way, the postman in the rear seat awoke from his doze to throw a mailbag out the window to a waiting porter on the platform. I tried to take pictures, but the landscape eluded me : one vista shifted into another, lasting only seconds, a dizzying displacement of hill and air, of haze and all the morning shades of green. The meat-grinder cogs working against the rack under the rail car ticked like an ageing clock and made me drowsy. I took out my inflatable pillow, blew it up, put it under my head, and slept peacefully in the sunshine until I was awakened by the thud of the rail car’s brakes and the banging of doors.

‘Ten minutes,’ said the driver.

We were just below a wooden structure, a doll’s house, its window boxes overflowing with red blossoms, and moss trimming its wide eaves. This was Bangu Station. It had a wide complicated verandah on which a waiter stood with a menu under his arm. The rail-car passengers scrambled up the stairs.

My Kalka breakfast had been premature; I smelled eggs and coffee and heard the Bengalis quarrelling with the waiters in English.

I walked down the gravel paths to admire the well-tended flower beds and the carefully mown lengths of turf beside the track; below the station a rushing stream gurgled, and signs there, and near the flower beds, read NO PLUCKING. A waiter chased me down to the stream and called out, ‘We have juices ! You like fresh mango juice? A little porridge? Coffee, tea?’

We resumed the ride, and the time passed quickly as I dozed again and woke to higher mountains, with fewer trees, stonier slopes, and huts perched more precariously. The haze had disappeared and the hillsides were bright, but the air was cool and a fresh breeze blew through the open windows of the rail car. In every tunnel the driver switched on orange lamps, and the racket of the clattering wheels increased and echoed.

After Solon the only people in the rail car were a family of Bengali pilgrims (all of them sound asleep, snoring, their faces turned up), the civil servant, the postman, and me. The next stop was Solon Brewery, where the air was pungent with yeast and hops, and after that we passed through pine forests and cedar groves. On one stretch a bamboo the size of a six-year-old crept off the tracks to let us go by. I remarked on the largeness of the creature.

The civil servant said, ‘There was once a saddhu – a holy man – who lived near Simla. He could speak to monkeys. A certain Englishman had a garden, and all the time the monkeys were causing him trouble. Monkeys can be very destructive. The Englishman told this saddhu his problem. The saddhu said, “I will see what I can do.” Then the saddhu went into the forest and assembled all the monkeys. He said, “I hear you are troubling the Englishman. That is bad. You must stop; leave his garden alone. If I hear that you are causing damage I will treat you very harshly.” And from that time onwards the monkeys never went into the Englishman’s garden.’

‘Do you believe that story?’

‘Oh, yes. But the man is now dead – the saddhu. I don't know what happened to the Englishman. Perhaps he went away, like the rest of them.’

A little farther on, he said, ‘What do you think of India?’

‘It’s a hard question,’ I said. I wanted to tell him about the children I had seen that morning pathetically raiding the leftovers of my breakfast, and ask him if he thought there was any truth in Mark Twain’s comment on Indians : ‘It is a curious people. With them, all life seems to be sacred except human life.’ But I added instead, ‘I haven’t been here very long.’

‘I will tell you what I think,’ he said. ‘If all people who are talking about honesty, fair play, socialism, and so forth – if they began to practise it themselves, India will do well. Otherwise there will be a revolution.’

He was an unsmiling man in his early fifties and had the stern features of a Brahmin. He neither drank nor smoked, and before he joined the civil service he had been a Sanskrit scholar in an Indian university. He got up at five every morning, had an apple, a glass of milk, and some almonds; he washed and said his prayers and after that took a long walk. Then he went to his office. To set an example for his junior officers he always walked to work, he furnished his office sparsely, and he did not require his bearer to wear a khaki uniform. He admitted that his example is unpersuasive. His junior officers had parking permits, sumptuous furnishings, and uniformed bearers.

‘I ask them why all this money is spent for nothing. They tell me to make a good first impression is very important. I say to the blighters, “What about second impression?”’

‘Blighters’ was a word that occurred often in his speech

Lord Clive was a blighter and so were most of the other viceroys. Blighters ask for bribes; blighters try to cheat Accounts Department; blighters are living in luxury and talking about socialism. it was a point of honour with this civil servant that he had never in his life given or received baksheesh : ‘Not even a single paisa.’ Some of his clerks had, and in eighteen years in the civil service he had personally fired thirty-two people. He thought it might be a record. I asked him what they had done wrong.

‘Gross incompetence,’ he said, ‘pinching money, hanky-panky. But I never fire anyone without first having a good talk with his parents. There was a blighter in the Audit Department, always pinching girls’ bottoms. Indian girls from good families ! I warned him about this, but he couldn't stop. So I told him I wanted to see his parents. The blighter said his parents lived fifty miles away. I gave him money for their bus fare. They were poor, and they were quite worried about the blighter. I said to them, “Now I want you to understand that your son is in deep trouble. He is causing annoyance to the lady members of this department. Please talk to him and make him understand that if this continues I will have no choice but to sack him.” Parents go away, blighter goes back to work, and ten days later he is at it again. I suspended him on the spot, then I charge-sheeted him.’

I wondered whether any of these people had tried to take revenge on him.

‘Yes, there was one. He got himself drunk one night and came to my house with a knife. “Come outside and I will kill you!” That sort of thing. My wife was upset but I was angry. I couldn't control myself. I dashed outside and fetched the blighter a booming kick. He dropped his knife and began to cry. “Don’t call the police,” he said. “I have a wife and children.” He was a complete coward, you see. I let him go and everyone criticized me – they said I should have brought charges but I told them he would never bother anyone again.

‘And there was another time. I was working for Heavy Electricals, doing an audit for some cheaters in Bengal. Faulty construction, double entries, and estimates five times what they should have been. There was also immorality. One bloke – son of a contractor, very wealthy – kept four harlots. He gave them whisky and made them take their clothes off and run naked into a group of women and children doing puja.

Disgraceful! Well, they didn't like me at all and the day I left there were four dacoits with knives waiting for me on the station road. But I expected that, so I took a different road, and the blighters never caught me. A month later two auditors were murdered by dacoits.’

The rail car tottered around a cliffside, and on the opposite slope, across a deep valley, was Simla. Most of the town fits the ridge like a saddle made entirely of rusty roofs, but as we drew closer the fringes seemed to be sliding into the valley.

Simla is unmistakable, for as Murray’s Handbook indicates, ‘its skyline is incongruously dominated by a Gothic Church, a baronial castle and a Victorian country mansion.’ Above these brick piles is the sharply pointed peak of Jakhu (8000 feet); below are the clinging house fronts. The southerly aspect of Simla, is so steep that flights of cement stairs take the place of roads. From the rail car it looked like an attractive place, a town of rusting splendour with snowy mountains in the background.

‘My office is in that castle,’ said the civil servant.

‘Gorton Castle,’ I said, referring to my handbook. ‘Do you work for the Accountant General of the Punjab?’

‘Well, I am the A.G.,’ he said. But he was giving information, not boasting. At Simla Station the porter strapped my suitcase to his back (he was a Kashmiri, up for the season).

The civil servant introduced himself as Vishnu Bhardwaj and invited me for tea that afternoon.

The Mall was filled with Indian vacationers taking their morning stroll, warmly dressed children, women with cardigans over their saris, and men in tweed suits, clasping the green Simla guidebook in one hand and a cane in the other. The promenading has strict hours, nine to twelve in the morning and four to eight in the evening, determined by meal times and shop openings. These hours were fixed a hundred years ago, when Simla was the summer capital of the Indian empire, and they have not varied. The architecture is similarly unchanged – it is all high Victorian, the the vulgarly grandiose touched colonial labour allowed, extravagant gutters and porticoes, buttressed by pillars and steelwork to prevent its slipping down the hill. The Gaiety Theatre (1887) is still the Gaiety Theatre (though when I was there it was the venue of a ‘Spiritual Exhibition’ I was not privileged to see); pettifogging continues in Gorton Castle, as praying does in Christ Church (1857), the Anglican cathedral; the viceroy’s lodge (Rastrapati Nivas), a baronial mansion, is now the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies, but the visiting scholars creep about with the difference of caretakers maintaining the sepulchral stateliness of the place. Scattered among these large Simla buildings are bungalows – Holly Lodge, Romney Castle, The Bricks, Forest View, Sevenoaks, Fernside – but the inhabitants are now Indians, or rather that inherited breed of Indian that insists on the guidebook, the walking stick, the cravat, tea at four, and an evening stroll to Scandal Point. It is the Empire with a dark complexion, an imperial outpost that the mimicking vacationers have preserved from change, though not the place of highly coloured intrigues described in Kim, and certainly tamer than it was a century ago. After all, Lola Montez, the grande horizontale, began her whoring in Simla, and the only single women I saw were short red-cheeked Tibetan labourers in quilted coats, who walked along the Mall with heavy stones in slings on their backs.

I had tea with the Bhardwaj family. It was not the simple meal I had expected. There were eight or nine dishes: pakora, vegetables fried in batter; poha, a rice mixture with peas, coriander, and turmeric; khira, a creamy pudding of rice, milk and sugar; a kind of fruit salad, with cucumber and lemon added to it, called chaat; murak, a Tamil savoury, like large nutty pretzels; tikkiya, potato cakes; malai chops, sweet sugary balls topped with cream; and almond-scented pinnis. I ate what I could, and the next day I saw Mr Bhadwarj’s office in Gorton Castle, It was as sparsely furnished as he had said on the rail car, and over his desk was this sign :

I am not interested in excuses for delay;

I am interested only in a thing done

–– Jawaharlal Nehru

*

The day I left I found an ashram on one of Simla’s slopes. I had been interested in visiting an ashram ever since the hippies on the Tehran Express had told me what marvellous places they were. But I was disappointed. The ashram was a ramshackle bungalow run by a talkative old man named Gupta, who claimed he had cured many people of advanced paralysis by running his hands over their legs. There were no hippies in this ashram, though Mr Gupta was anxious to recruit me. I said I had a train to catch. He said that if I was a believer in yoga I wouldn't worry about catching trains. I said that was why I wasn't a believer in yoga.

Mr Gupta said, ‘I will tell you a story. A yogi was approached by a certain man who said he wanted to be a student . Yogi said he was very busy and had no time for man. Man said he was desperate. Yogi did not believe him. Man said he would commit suicide by jumping from roof if yogi would not take him on. Yogi said nothing. Man jumped.

‘“Bring his body to me,” said yogi. Body was brought Yogi passed his hands over body and after a few minutes man regained his life.

‘“Now you are ready to be my student,” said yogi. “I believe you can act on proper impulses and you have shown me great sincerity.” So man who had been restored to the living became student.’

‘Have you ever brought anyone to life?’ I asked.

‘Not as yet,’ said Mr Gupta

Not as yet! His Guru was Paramahansa Yogananda, whose sleek saintly face was displayed all over the bungalow. In Ranchi, Paramahansa Y. had a vision. This was his vision : a gathering of millions of Americans who needed his advice. He described them in his Autobiography as ‘a vast multitude, gazing at me intently’ that ‘swept actorlike across the stage of consciousness … the Lord is calling me to America … Yes! I am going forth to discover America, like Columbus. He thought he had found India; surely there is a karmic link between these two lands!’ He could see the people so clearly, he recognized their faces when he arrived in California a few years later. He stayed in Los Angeles for thirty years, and, unlike Columbus, died rich, happy and fulfilled. Mr Gupta told me this hilarious story in a tone of great reverence, and then he took me on a tour of the bungalow, drawing my attention to the may portraits of Jesus (painted to look like a yogi) he had tacked to the walls.

‘Where do you live?’ asked a small friendly ashramite, who was eating an apple. (Simla apples are delicious, but, because of a trade agreement, the whole crop goes to Poland.)

‘South London at the moment.’

‘But it is so noisy and dirty there!’

I found this an astonishing observation from a man who said he was from Kathmandu; but I let it pass.

‘I used to live in Kensington Palace Gardens,’ he said. ‘The rent was high, but my government paid. I was the Nepalese ambassador at the time.’

‘Did you ever meet the queen?’

‘Many times ! The queen liked to talk about the plays that were on in London. She talked about the actors and the plot an so on. She would say, “Did you like this part of the play or that one?” If you hadn't seen the play it was very difficult to reply. But usually she talked about horses, and I’m sorry to say I have no interest at all in horses.’

I left the ashram and paid a last visit to Mr Bhardwaj. He gave me various practical warnings about travelling and advised me to visit Madras, where I could see the real India. He was off to have the carburettor in his car checked and to finish up some accounts at his office. He hoped I had enjoyed Simla and said it was a shame I hadn't seen any snow. He was formal, almost severe in his farewell, but walking down to Cart Road, he said, ‘I will see you in England or America.’

‘That would be nice. I hope we do meet again.’

‘We will,’ he said, with such certainty I challenged it.

‘How do you know?’

‘I am about to be transferred from Simla. Maybe going to England, maybe to the States. That is what my horoscope says.’

0 notes

Text

Don’t Let the Prefect Be the Enemy of the Gay

Don’t Let the Prefect Be the Enemy of the Gay

Where I live, a powerful local official causes a contribution to be withheld from an organization planning a pride festival in the town square. The official does not wish the county’s name to be associated with a drag show, a one-hour feature of the day-long event.

A citizen of another country tells me of reading Paul Theroux’s book “Deep South” and marveling at the number of churches and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Very sad and yet very truthful.

If you cannot go and tour the Border area or if you have ever been curious about what is Real about US/Mexico relations along the border of Texas, don't believe the hype. Go read this book.

Theroux is the best writer to live vicariously through but a lot of this is just so sad and disappointing because it is real and preventable. It was hard to get through at time, being a Texan.

Theroux brings out the human drama of those living on each side of the border so well. There is also the running theme of change and how actions by the Clinton administration instantly turned lively, full, thriving Mexican areas into abandoned ghost towns.

It is a book I think you won't forget if you take the chance to read it.

#bookblr#books#book review#racism#disparity#paul theroux#on the plain of snakes#Texas#Mexico#the border

0 notes