#popular historiography

Text

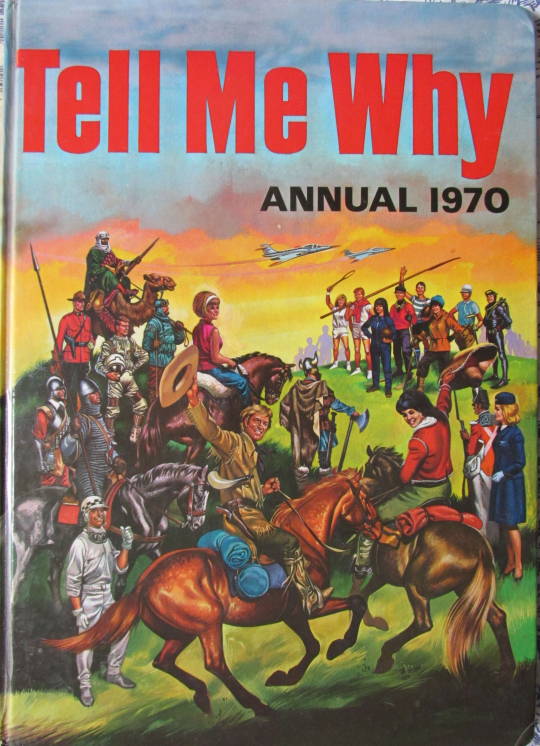

Tell Me Why children's annual 1970

@suburbanbeatnik @trashpoppaea @montagnarde1793 @patientsisavertu @taleon-arts @vivelareine

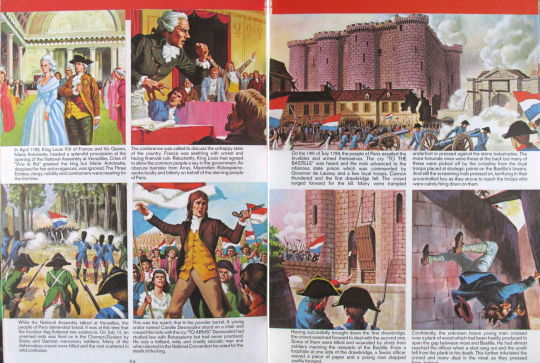

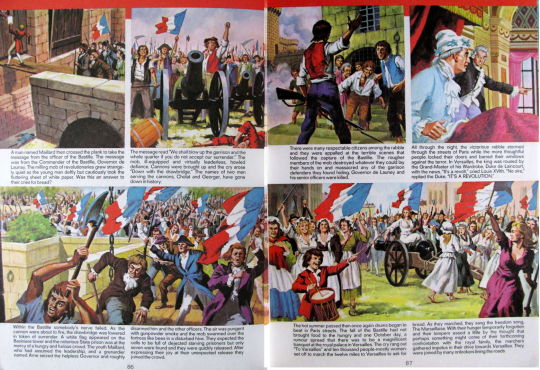

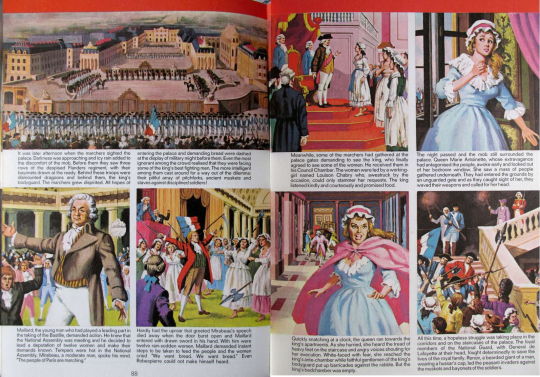

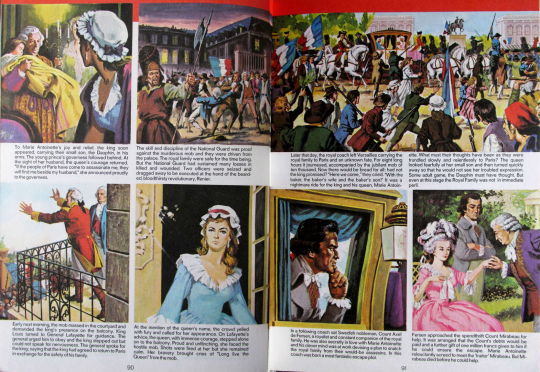

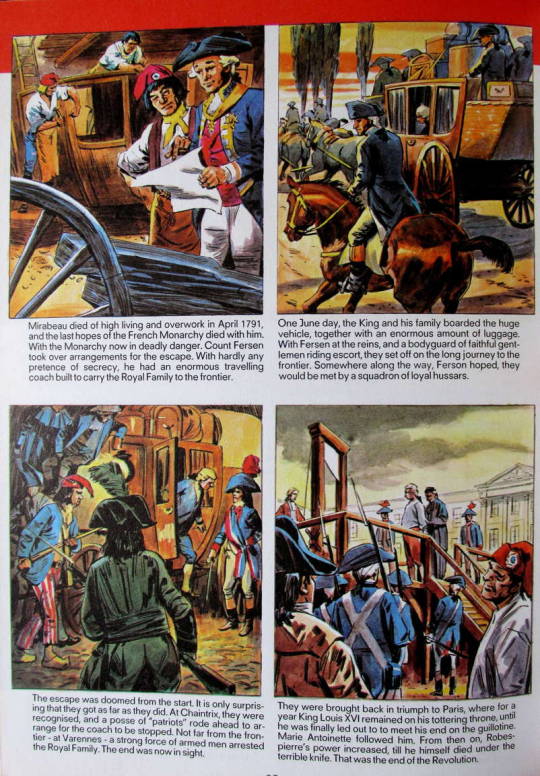

If you thought Jackie 1976 was bad… This is from Tell Me Why, a non-fiction annual from 1970. Good to see a piece on Vidocq, but Marie-Antoinette has the Julie Christie/Jean Shrimpton/Catherine Deneuve look of the Jackie heroine, and I'm not sure how old the artist thought Max was…! They've made him look older than Marat! In the children's books of this era, the Brissotins were generally presented as the only Revolutionaries you were allowed to like.

#french revolution#révolution française#popular historical iconography#popular historiography#vintage children's books

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excellent question! It might sound straightforward, but it's actually very fuzzy.

Optimate and populare were not ideologies, like "socialist" or "monarchist," and they weren't political parties, like "democrat" or "Tory." So what were they?

Depends on who you ask - and when. In the Pro Sestio, Cicero defined the optimates as decent, honorable people, and populares as demagogues who tried to appeal to the masses because they couldn't hack it in the Senate. But in his Fourth Catilinarian Oration, he uses popularis in a positive sense, more akin to "one who serves the popular will." He applies that word to himself and Julius Caesar(!), and contrasts it with politicians who talk a good game but haven't the guts or integrity to follow through.

Muddling things further, most Roman writers don't use either word in the same way as Cicero. They use populares to mean "countrymen" or "fellow Romans," and optimate is a rare synonym for aristocracy. Sallust never refers to them as distinct factions, even when he's talking about class conflict and political movements.

So, we're left with asking whether optimate and populare are useful concepts at all. Erich Gruen and Henrik Mouritsen reject them entirely, arguing that it makes more sense to divide Roman politics along family lines and personal rivalries. Andrew Lintott and T.P. Wiseman believe the terms could be used for describing ideological trends, albeit not for discrete political parties. Robert Morstein-Marx redefines them as methods for gaining influence - optimates networking with elite senators, populares appealing to the crowds - which weren't mutually exclusive.

Personally, I think it's useful to be specific. To speak of the Catonians and Marcelli, for instance, rather than lumping them both into optimates. And it helps to remember that political factions were time-bound: you can identify Marians and Sullans in 80 BCE, but the groups break down by 70 BCE. There weren't many organized groups or movements that lasted for multiple generations of the republic.

#sorry anon but i'm not going to talk about your favorite anime on here. i'll give you something more interesting: political historiography!!#just roman asks#optimates and populares#jlrrt essays

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why is it that certain sensationalist trivias, still get peddled by professional historians as absolute truths? Like the Caranus debacle. PG's Alexander of Macedon, despite being an excellent account, still mentions the Caranus + Europa double alleged BBQfication. Even though, the timeline&Caranus' unicorn name, reek of myth? Or Stateira getting long distance impregnated by Darius (though Green suggests in fine print that Alexander raped her). What makes a historical tale more or less credible?

First, I’d caution that we look at when some of these books and articles were written. While the more recent version of Green’s Alexander of Macedon (U. Cal, Berkeley) is 1991, it’s a reprint of his much earlier Thames-and-Hudson bio from 1974, sans pictures. (Also, Green—who’s still alive and kicking!—is 97 this year, so that contextualizes his age.) A general critique of Peter for a while now (as far back as From Alexander to Actium) is that he’s not on top of the more recent publications in the field, which causes some of his conclusions to be dated. Many older scholars can be guilty of that. I can’t even keep up with everything coming out on Alexander and/or Philip and/or Macedonia each year, especially as more and more are in languages I don’t read, such as Italian or Spanish. Even my German is shaky.

OTOH, the proliferation of academic publications in various languages is great, as it signals a healthy field. OTOH, it’s problematic, as most people just don’t read multiple languages, and what languages might have been fashionable back in grad school has shifted since. Additionally, Americans are at a real disadvantage due to our very poor education system here when it comes to learning languages (Spanish aside)—unless one is wealthy enough to attend private schools. And that’s a topic for a different post about elite education in Classics, and the language barrier.

But the upshot is that, while older scholars often gain real breadth of knowledge that allows connections and conclusions younger scholars just can’t make yet, it can become harder to keep up with everything coming out, on top of teaching and service requirements at universities. I’d love to have more time to read the latest—but I can’t and get all my student papers graded, attend all the meetings I have to go to, prep new classes, learn online platforms, etc., etc.

One reason we try to protect pre-tenure faculty from undue service IS so they can write/publish (and do the reading required). Post-tenure, All That Other Stuff starts demanding our time. Way back in grad school, Gene Borza told me, “You will never have read so widely and know as much about a particular slice of the field than you do right now.” I thought he was joking. I know a lot more now than I knew then, to be sure—but feel perpetually behind on recent research.

Anyway, I mention the publication date because history is an ever-developing field. We can talk about Alexander studies as a series of “waves,” if you will. The initial wave viewed Alexander very positively, starting with Droysen (late 1800s), through Tarn, Burns, Milns, Robinson, some others, down into the 1960s and early ‘70s. Hammond was kinda the last of them, who published well into the ‘90s, also arguably Hamilton (although I see him as less forgiving). But this was the Great Man approach. Sources were taken mostly at face value, including Greek views of the Macedonians, with a distinct taste for colonialist narratives such as Plutarch (the Greek “civilizing” of the Barbarian East, etc.). Hammond, however, was among those who seriously questioned Greek views of Macedonians…even while he accepted other things uncritically.

So, in short, these are not absolutely separate buckets. Just general trends.

The next wave brought the Skeptics, engendered by Badian, Schachermeyer, Fredericksmeyer, Green, etc. It still had a fair bit of unconscious colonialist (and misogynistic) taint but began to do much more rigorous source criticism. Maybe ol’ Alexander wasn’t so great, after all. I think of Ian Worthington as still in that vein—Hammond’s flip side. Ha. (Which is funny as Ian edited Nick’s festschrift [a collection of papers in honor of a person]. But Hammond was a legend in his lifetime. Regardless of whether one agrees with everything he wrote, his impact on Macedonian history simply can’t be overestimated. I don’t think anybody, ever again, will [or can] have that sort of influence, given how the field has grown.)

Anyway, around the same time, Macedonian studies (and Philip) were opening as a field in their own right, thanks to Edson and Dell—and Hammond—followed by Borza, Errington, Ellis, Cawkwell, Walbank (Hellenistic), and Greeks like Hatzopoulos and Palagia, then Greenwalt, Anson, Adams, Heckel, Carney, Baynham, Atkinson, etc.

(I’m leaving out names, I’m sure, as I’m doing this on the fly without my library at hand, so apologies.)

Anyway, these things dovetailed to give us some new perspectives, including an attempt to detangle Macedonia from S. Greece, and to spot the misogyny behind texts (thank you, Carney and MacCurdy, et al.), and generally to think further about matters of culture and textual context.

I was a grad student at the back end of that wave, btw.

The “new”(-ish) wave(s?) have been to further contextualize our sources, not just to separate Greek from Macedonian, or to seek the sources behind our extant biographies, but to better recognize the Roman (imperial) overlay. It’s not that earlier historians didn’t know our existing sources were Roman era, but that the focus had been on trying to determine the sources behind our surviving sources: e.g., Kallisthenes, Kleitarchos, Ptolemy, Aristobulos, etc. Lionel Pearson’s The Lost Historians of Alexander the Great was the classic text of that type. What Pearson (and others) did less was talk about contemporary (Roman) influences on our surviving authors.

This new wave includes scholars like Asirvatham, Müller, Ogden, Bowden, Spencer, Pownall, Howe, Finn, etc., etc. There’s also good work being done on military stuff, following Heckel. They’re very much into the textual evidence. Also Carney still, and Baynham. So these are new trends in Alexander historiography.

A feature of this third/fourth wave has been to pick apart some heretofore accepted stories—such as, say, proskynesis. Or the story of Statiera mentioned in the Ask. You’ll see that new take in the forthcoming Netflix docudrama. Alexander isn’t so hands-off. Although I don’t think it was rape so much as Realpolitik, once it became clear Darius had abandoned his family to their fate. And maybe not even Alexander’s idea. 😉

We saw such questioning even in the second/early third wave. Take Karanos. That’s been questioned by Borza, Carney, Greenwalt, et al. BUT Greenwalt has really interesting things to say about the evolving genealogy of the Argead house across time, with morphing forefathers, depending on who the king was. So we get Perdikkas under Alexandros I and Perdikkas “II,” then an Archelaos under Archelaos (Euripides’ lost play), and finally, Karanos under Philip II (or post-Philip). Jonathan Hall in (et al.) Hellenicities talks about the creation of these falsified genealogies in ancient Greece as a means to build and (re-)affirm bonds for political, military, and trade purposes. These things don’t stay the same across time.

The upshot remains that it’s important to check the publication date for any particular book or article, and be sure it’s the original publication, too. Again, the 1991 Univ. of Cal, Berkeley edition of Alexander of Macedon = the 1974 Thames and Hudson’s book of the same title. (If you Google it, you’ll find the “originally published” date, btw.) In short, he wrote it before most people had begun to question the finer points of Kleopatra-Eurydike’s murder by Olympias. OR before so much doubt had been thrown on Justin as a source. (Just wait for the chapter by Carney in the work I’m currently editing. She’s going to trash and burn OH, so much of Trogus/Justin. I’ll give no more spoilers, but yeah. It’s a long, but very good chapter on historiography.)

So publishing date is one thing to look at.

The other is WHO did the writing.

There’s always been a small cottage industry in publishing on Alexander, but quite a few bios have come out recently by people who aren’t Macedonian specialists, or even (sometimes) trained Greek historians (Everitt, I’m looking at you).* Even Goldsworthy’s dual bio, which formed the basis of the recent History Channel episode, was written by a Romanist, albeit he’s known for his military topics. Paul Cartledge, who also wrote a popular bio on ATG, is a specialist on Sparta. Some scholars are one-foot-in, like Carol Thomas, who did Alexander and His World (2006). She knows more about Macedonia due to personal contacts, but her area of serious scholarship is the Dark Age/Early Archaic Age (= Early Iron Age).

So, yes, it’s really important to ask, Who wrote the book/article I���m reading? How deep are they into scholarship on ancient Macedonia/Alexander/Philip II, etc.

The latest bios of Alexander by actual Alexander specialists are Sabine Müller’s Alexander Der Grosse: Eroberungen - Politik – Rezeption (2019), Franca Landucci’s Alessandro Magno (2019), Hugh Bowden’s Alexander the Great, a very short introduction (2014), Edward Anson’s Alexander the Great: Themes and Issues (2013), Lindsay Adams Alexander the Great: Legacy of a Conqueror (2005), and Ian Worthington’s Alexander the Great: Man and God (2004) and the later By the Spear, which includes Phil, too (2016). (Ed Anson also did Philip II, Father of Alexander the Great: Themes and Issues, 2020.) I've probably missed one, so apologize in advance. Again...library is in my office.

If you want to read a biography of Alexander, read a couple of those.

I’ve thought more seriously of late about writing my own biography, intended for non-specialists (e.g., without footnotes but with “for further reading”). Many of these by my colleagues have been textbooks, like Lindsay’s and Ed’s. I’d be more inclined to write it for the interested non-specialist. But I’d have to find a publisher, and I wouldn’t even seriously consider it until this Hephaistion & Krateros book is done.

Also, I might have a hard time selling “yet another” biography on Alexander, especially if it’s not dripping with drama and/or cherished myth and/or doesn’t try to paint Alexander as either a god or a monster.

Or maybe THAT could be the selling point. “This is the biography by a specialist that brings the interested reader up to date on the latest scholarship regarding Alexander, Philip, and Argead Macedonia, but does it in layman’s language, and isn’t a college textbook.”

---------------------

*You may wonder why publishers buy books from historians who aren’t Macedonian specialists? Well, sometimes they want that. Carol wrote hers precisely because she’s not a specialist, but had contacts who were, and therefore was thought to be better at breaking it all down for students. Other publishers want the sensationalist stuff, or a “new angle” (which is rarely actually new).

#Alexander the Great#historiography of Alexander the Great#historiography of ancient Macedonia#ancient Macedonia#sensationalism in popular biographies on Alexander the Great#Classics#asks#tagamemnon#ancient Greece

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Partners will text you this out of nowhere and then add “feel free to post on tumblr.com”

#virginia couples do this: *get mad once a month about inordinately pro-confederate popular historiography*#me and jenny

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

imperialism and science reading list

edited: by popular demand, now with much longer list of books

Of course Katherine McKittrick and Kathryn Yusoff.

People like Achille Mbembe, Pratik Chakrabarti, Rohan Deb Roy, Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, and Elizabeth Povinelli have written some “classics” and they track the history/historiography of US/European scientific institutions and their origins in extraction, plantations, race/slavery, etc.

Two articles I’d recommend as a summary/primer:

Zaheer Baber. “The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge.” Journal of Contemporary Asia. May 2016.

Kathryn Yusoff. “The Inhumanities.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 2020.

Then probably:

Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Colette Le Petitcorps. “Introduction: Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times.” Global Plantations in the Modern World: Sovereignties, Ecologies, Afterlives. 2023.

Sharae Deckard. “Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden.” 2010. (Chornological overview of development of knowledge/institutions in relationship with race, slavery, profit as European empires encountered new lands and peoples.)

Gregg Mitman. “Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia’s Plantation Economy.” Environmental History. 2017, (Interesting case study. US corporations were building fruit plantations in Latin America and rubber plantations in West Africa during the 1920s. Medical doctors, researchers, and academics made a strong alliance these corporations to advance their careers and solidify their institutions. By 1914, the director of Harvard’s Department of Tropical Medicine was also simultaneously the director of the Laboratories of the Hospitals of the United Fruit Company, which infamously and brutally occupied Central America. This same Harvard doctor was also a shareholder in rubber plantations, and had a close personal relationship with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, which occupied West Africa.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Globalizing the Routes of Breadfruit and Other Bounties.” 2008. (Case study of how British wealth and industrial development built on botany. Examines Joseph Banks; Kew Gardens; breadfruit; British fear of labor revolts; and the simultaneous colonizing of the Caribbean and the South Pacific.)

Elizabeth DeLoughrey. “Satellite Planetarity and the Ends of the Earth.” 2014. (Indigenous knowledge systems; “nuclear colonialism”; US empire in the Pacific; space/satellites; the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.)

Fahim Amir. “Cloudy Swords.” e-flux Journal #115, February 2021. (”Pest control”; termites; mosquitoes; fear of malaria and other diseases during German colonization of Africa and US occupations of Panama and the wider Caribbean; origins of some US institutions and the evolution of these institutions into colonial, nationalist, and then NGO forms over twentieth century.)

Some of the earlier generalist classic books that explicitly looked at science as a weapon of empires:

Schiebinger’s Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World; Delbourgo’s and Dew’s Science and Empire in the Atlantic World; the anthology Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World; Canzares-Esquerra’s Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World.

One of the quintessential case studies of science in the service of empire is the British pursuit of quinine and the inoculation of their soldiers and colonial administrators to safeguard against malaria in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia at the height of their power. But there are so many other exemplary cases: Britain trying to domesticate and transplant breadfruit from the South Pacific to the Caribbean to feed laborers to prevent slave uprisings during the age of the Haitian Revolution. British colonial administrators smuggling knowledge of tea cultivation out of China in order to set up tea plantations in Assam. Eugenics, race science, biological essentialism, etc. in the early twentieth century. With my interests, my little corner of exposure/experience has to do mostly with conceptions of space/place; interspecies/multispecies relationships; borderlands and frontiers; Caribbean; Latin America; islands. So, a lot of these recs are focused there. But someone else would have better recs, especially depending on your interests. For example, Chakrabarti writes about history of medicine/healthcare. Paravisini-Gebert about extinction and Caribbean relationship to animals/landscape. Deb Roy focuses on insects and colonial administration in South Asia. Some scholars focus on the historiography and chronological trajectory of “modernity” or “botany” or “universities/academia,”, while some focus on Early Modern Spain or Victorian Britain or twentieth-century United States by region. With so much to cover, that’s why I’d recommend the articles above, since they’re kinda like overviews.Generally I read more from articles, essays, and anthologies, rather than full-length books.

Some other nice articles:

(On my blog, I’ve got excerpts from all of these articles/essays, if you want to search for or read them.)

Katherine McKittrick. “Dear April: The Aesthetics of Black Miscellanea.” Antipode. First published September 2021.

Katherine McKittrick. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe. 2013.

Antonio Lafuente and Nuria Valverde. “Linnaean Botany and Spanish Imperial Biopolitics.” A chapter in: Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World. 2004.

Kathleen Susan Murphy. “A Slaving Surgeon’s Collection: The Pursuit of Natural History through the British Slave Trade to Spanish America.” 2019. And also: “The Slave Trade and Natural Science.” In: Oxford Bibliographies in Atlantic History. 2016.

Timothy J. Yamamura. “Fictions of Science, American Orientalism, and the Alien/Asian of Percival Lowell.” 2017.

Elizabeth Bentley. “Between Extinction and Dispossession: A Rhetorical Historiography of the Last Palestinian Crocodile (1870-1935).” 2021.

Pratik Chakrabarti. “Gondwana and the Politics of Deep Past.” Past & Present 242:1. 2019.

Jonathan Saha. “Colonizing elephants: animal agency, undead capital and imperial science in British Burma.” BJHS Themes. British Society for the History of Science. 2017.

Zoe Chadwick. “Perilous plants, botanical monsters, and (reverse) imperialism in fin-de-siecle literature.” The Victorianist: BAVS Postgraduates. 2017.

Dante Furioso: “Sanitary Imperialism.” Jeremy Lee Wolin: “The Finest Immigration Station in the World.” Serubiri Moses. “A Useful Landscape.” Andrew Herscher and Ana Maria Leon. “At the Border of Decolonization.” All from e-flux.

William Voinot-Baron. “Inescapable Temporalities: Chinook Salmon and the Non-Sovereignty of Co-Management in Southwest Alaska.” 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “White ants, empire, and entomo-politics in South Asia.” The Historical Journal. 2 October 2019.

Rohan Deb Roy. “Introduction: Nonhuman Empires.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35 (1). May 2015.

Lawrence H. Kessler. “Entomology and Empire: Settler Colonial Science and the Campaign for Hawaiian Annexation.” Arcadia (Spring 2017).

Sasha Litvintseva and Beny Wagner. “Monster as Medium: Experiments in Perception in Early Modern Science and Film.” e-flux. March 2021.

Lesley Green. “The Changing of the Gods of Reason: Cecil John Rhodes, Karoo Fracking, and the Decolonizing of the Anthropocene.” e-flux Journal Issue #65. May 2015.

Martin Mahony. “The Enemy is Nature: Military Machines and Technological Bricolage in Britain’s ‘Great Agricultural Experiment.’“ Environment and Society Portal, Arcadia. Spring 2021.

Anna Boswell. “Anamorphic Ecology, or the Return of the Possum.” 2018. And; “Climates of Change: A Tuatara’s-Eye View.”2020. And: “Settler Sanctuaries and the Stoat-Free State." 2017.

Katherine Arnold. “Hydnora Africana: The ‘Hieroglyphic Key’ to Plant Parasitism.” Journal of the History of Ideas - JHI Blog - Dispatches from the Archives. 21 July 2021.

Helen F. Wilson. “Contact zones: Multispecies scholarship through Imperial Eyes.” Environment and Planning. July 2019.

Tom Brooking and Eric Pawson. “Silences of Grass: Retrieving the Role of Pasture Plants in the Development of New Zealand and the British Empire.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. August 2007.

Kirsten Greer. “Zoogeography and imperial defence: Tracing the contours of the Neactic region in the temperate North Atlantic, 1838-1880s.” Geoforum Volume 65. October 2015. And: “Geopolitics and the Avian Imperial Archive: The Zoogeography of Region-Making in the Nineteenth-Century British Mediterranean.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2013,

Marco Chivalan Carrillo and Silvia Posocco. “Against Extraction in Guatemala: Multispecies Strategies in Vampiric Times.” International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. April 2020.

Laura Rademaker. “60,000 years is not forever: ‘time revolutions’ and Indigenous pasts.” Postcolonial Studies. September 2021.

Paulo Tavares. “The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of the Amazon’s Deep History.” Architecture in the Anthropocene. Edited by Etienne Turpin. 2013.

Kathryn Yusoff. “Geologic Realism: On the Beach of Geologic Time.” Social Text. 2019. And: “The Anthropocene and Geographies of Geopower.” Handbook on the Geographies of Power. 2018. And: “Climates of sight: Mistaken visbilities, mirages and ‘seeing beyond’ in Antarctica.” In: High Places: Cultural Geographies of Mountains, Ice and Science. 2008. And:“Geosocial Formations and the Anthropocene.” 2017. And: “An Interview with Elizabeth Grosz: Geopower, Inhumanism and the Biopolitical.” 2017.

Mara Dicenta. “The Beavercene: Eradication and Settler-Colonialism in Tierra del Fuego.” Arcadia. Spring 2020.

And then here are some books:

Africa as a Living Laboratory: Empire, Development, and the Problem of Scientific Knowledge, 1870-1950 (Helen Tilley, 2011); Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Londa Schiebinger, 2004)

Red Coats and Wild Birds: How Military Ornithologists and Migrant Birds Shaped Empire (Kirsten A. Greer); The Empirical Empire: Spanish Colonial Rule and the Politics of Knowledge (Arndt Brendecke, 2016); Medicine and Empire, 1600-1960 (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2014)

Anglo-European Science and the Rhetoric of Empire: Malaria, Opium, and British Rule in India, 1756-1895 (Paul Winther); Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Sadiah Qureshi, 2011); Unfreezing the Arctic: Science, Colonialism, and the Transformation of Inuit Lands (Andrew Stuhl)

Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture (Britt Rusert, 2017); Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022); Colonizing Animals: Interspecies Empire in Myanmar (Jonathan Saha)

The Nature of German Imperialism: Conservation and the Politics of Wildlife in Colonial East Africa (Bernhard Gissibl, 2019); Curious Encounters: Voyaging, Collecting, and Making Knowledge in the Long Eighteenth Century (Edited by Adriana Craciun and Mary Terrall, 2019)

Frontiers of Science: Imperialism and Natural Knowledge in the Gulf South Borderlands, 1500-1850 (Cameron B. Strang); The Ends of Paradise: Race, Extraction, and the Struggle for Black Life in Honduras (Chirstopher A. Loperena, 2022); Mining Language: Racial Thinking, Indigenous Knowledge, and Colonial Metallurgy in the Early Modern Iberian World (Allison Bigelow, 2020); The Herds Shot Round the World: Native Breeds and the British Empire, 1800-1900 (Rebecca J.H. Woods); American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science (Megan Raby, 2017); Producing Mayaland: Colonial Legacies, Urbanization, and the Unfolding of Global Capitalism (Claudia Fonseca Alfaro, 2023)

Domingos Alvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World (James Sweet, 2011); A Temperate Empire: Making Climate Change in Early America (Anya Zilberstein, 2016); Educating the Empire: American Teachers and Contested Colonization in the Philippines (Sarah Steinbock-Pratt, 2019); Soundings and Crossings: Doing Science at Sea, 1800-1970 (Edited by Anderson, Rozwadowski, et al, 2016)

Possessing Polynesians: The Science of Settler Colonial Whiteness in Hawai’i and Oceania (Maile Arvin); Overcoming Niagara: Canals, Commerce, and Tourism in the Niagara-Great Lakes Borderland Region, 1792-1837 (Janet Dorothy Larkin, 2018); A Great and Rising Nation: Naval Exploration and Global Empire in the Early US Republic (Michael A. Verney, 2022); In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850-1960 (Alice Conklin, 2013)

Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Daniela Cleichmar, 2012); Tea Environments and Plantation Culture: Imperial Disarray in Eastern India (Arnab Dey, 2022); Drugs on the Page: Pharmacopoeias and Healing Knowledge in the Early Modern Atlantic World (Edited by Crawford and Gabriel, 2019)

Cooling the Tropics: Ice, Indigeneity, and Hawaiian Refreshment (Hi’ilei Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart, 2022); In Asian Waters: Oceanic Worlds from Yemen to Yokkohama (Eric Tagliacozzo); Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Urmi Engineer Willoughby, 2017); Turning Land into Capital: Development and Dispossession in the Mekong Region (Edited by Hirsch, et al, 2022); Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910 (Sarah E.M. Grossman, 2018)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski); Colonial Fantasies, Imperial Realities: Race Science and the Making of Polishness on the Fringes of the German Empire, 1840-1920 (Lenny A. Urena Valerio); Against the Map: The Politics of Geography in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Adam Sills, 2021)

Under Osman’s Tree: The Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Environmental History (Alan Mikhail, 2017); Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (Jim Endersby); Proving Grounds: Militarized Landscapes, Weapons Testing, and the Environmental Impact of U.S. Bases (Edited by Edwin Martini, 2015)

Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (Multiple authors, 2007); Space in the Tropics: From Convicts to Rockets in French Guiana (Peter Redfield); Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 (Andrew Togert, 2015); Dust Bowls of Empire: Imperialism, Environmental Politics, and the Injustice of ‘Green’ Capitalism (Hannah Holleman, 2016); Postnormal Conservation: Botanic Gardens and the Reordering of Biodiversity Governance (Katja Grotzner Neves, 2019)

Botanical Entanglements: Women, Natural Science, and the Arts in Eighteenth-Century England (Anna K. Sagal, 2022); The Platypus and the Mermaid and Other Figments of the Classifying Imagination (Harriet Ritvo); Rubber and the Making of Vietnam: An Ecological History, 1897-1975 (Michitake Aso); A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Kathryn Yusoff, 2018); Staple Security: Bread and Wheat in Egypt (Jessica Barnes, 2023); No Wood, No Kingdom: Political Ecology in the English Atlantic (Keith Pluymers); Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1768-1941 (Lynn Hollen Lees, 2017); Fish, Law, and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia (Douglas C. Harris, 2001); Everywhen: Australia and the Language of Deep Time (Edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker, and Jakelin Troy); Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo-American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Joyce Chaplin, 2001)

American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750-1865 (Jeremy Zallen); Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire (Erik Linstrum, 2016); Lakes and Empires in Macedonian History: Contesting the Water (James Pettifer and Mirancda Vickers, 2021); Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti); Seeds of Control: Japan’s Empire of Forestry in Colonial Korea (David Fedman)

Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination (Julie Cruikshank); The Fishmeal Revolution: The Industrialization of the Humboldt Current Ecosystem (Kristin A. Wintersteen, 2021); The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O’Connor); An Imperial Disaster: The Bengal Cyclone of 1876 (Benjamin Kingsbury, 2018); Geographies of City Science: Urban Life and Origin Debates in Late Victorian Dublin (Tanya O’Sullivan, 2019)

American Hegemony and the Postwar Reconstruction of Science in Europe (John Krige, 2006); Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule (Ann Laura Stoler, 2002); Rivers of the Sultan: The Tigris and Euphrates in the Ottoman Empire (Faisal H. Husain, 2021);

The Sanitation of Brazil: Nation, State, and Public Health, 1889-1930 (Gilberto Hochman, 2016); The Imperial Security State: British Colonial Knowledge and Empire-Building in Asia (James Hevia); Japan’s Empire of Birds: Aristocrats, Anglo-Americans, and Transwar Ornithology (Annika A. Culver, 2022)

Moral Ecology of a Forest: The Nature Industry and Maya Post-Conservation (Jose E. Martinez, 2021); Sound Relations: Native Ways of Doing Music History in Alaska (Jessica Bissette Perea, 2021); Citizens and Rulers of the World: The American Child and the Cartographic Pedagogies of Empire (Mashid Mayar); Anthropology and Antihumanism in Imperial Germany (Andrew Zimmerman, 2001)

The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century (Multiple authors, 2016); The Nature of Slavery: Environment and Plantation Labor in the Anglo-Atlantic World (Katherine Johnston, 2022); Seeking the American Tropics: South Florida’s Early Naturalists (James A. Kushlan, 2020); The Postwar Origins of the Global Environment: How the United Nations Built Spaceship Earth (Perrin Selcer, 2018)

The Colonial Life of Pharmaceuticals: Medicines and Modernity in Vietnam (Laurence Monnais); Quinoa: Food Politics and Agrarian Life in the Andean Highlands (Linda J. Seligmann, 2023) ; Critical Animal Geographies: Politics, intersections and hierarchies in a multispecies world (Edited by Kathryn Gillespie and Rosemary-Claire Collard, 2017); Spawning Modern Fish: Transnational Comparison in the Making of Japanese Salmon (Heather Ann Swanson, 2022); Imperial Visions: Nationalist Imagination and Geographical Expansion in the Russian Far East, 1840-1865 (Mark Bassin, 2000); The Usufructuary Ethos: Power, Politics, and Environment in the Long Eighteenth Century (Erin Drew, 2022)

Intimate Eating: Racialized Spaces and Radical Futures (Anita Mannur, 2022); On the Frontiers of the Indian Ocean World: A History of Lake Tanganyika, 1830-1890 (Philip Gooding, 2022); All Things Harmless, Useful, and Ornamental: Environmental Transformation Through Species Acclimitization, from Colonial Australia to the World (Pete Minard, 2019)

Practical Matter: Newton’s Science in the Service of Industry and Empire, 1687-1851 (Margaret Jacob and Larry Stewart); Visions of Nature: How Landscape Photography Shaped Setller Colonialism (Jarrod Hore, 2022); Timber and Forestry in Qing China: Sustaining the Market (Meng Zhang, 2021); The World and All the Things upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration (David A. Chang);

Deep Cut: Science, Power, and the Unbuilt Interoceanic Canal (Christine Keiner); Writing the New World: The Politics of Natural History in the Early Spanish Empire (Mauro Jose Caraccioli); Two Years below the Horn: Operation Tabarin, Field Science, and Antarctic Sovereignty, 1944-1946 (Andrew Taylor, 2017); Mapping Water in Dominica: Enslavement and Environment under Colonialism (Mark W. Hauser, 2021)

To Master the Boundless Sea: The US Navy, the Marine Environment, and the Cartography of Empire (Jason Smith, 2018); Fir and Empire: The Transformation of Forests in Early Modern China (Ian Matthew Miller, 2020); Breeds of Empire: The ‘Invention’ of the Horse in Southeast Asia and Southern Africa 1500-1950 (Sandra Swart and Greg Bankoff, 2007)

Science on the Roof of the World: Empire and the Remaking of the Himalaya (Lachlan Fleetwood, 2022); Cattle Colonialism: An Environmental History of the Conquest of California and Hawai’i (John Ryan Fisher, 2017); Imperial Creatures: Humans and Other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1819-1942 (Timothy P. Barnard, 2019)

An Ecology of Knowledges: Fear, Love, and Technoscience in Guatemalan Forest Conservation (Micha Rahder, 2020); Empire and Ecology in the Bengal Delta: The Making of Calcutta (Debjani Bhattacharyya, 2018); Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880-1914 (Kristen Hussey, 2021)

Biotic Borders: Transpacific Plant and Insect Migration and the Rise of Anti-Asian Racism in America, 1890-1950 (Jeannie N. Shinozuka); Coral Empire: Underwater Oceans, Colonial Tropics, Visual Modernity (Ann Elias, 2019); Hunting Africa: British Sport, African Knowledge and the Nature of Empire (Angela Thompsell, 2015)

326 notes

·

View notes

Note

I understand you're well read, more than myself, but from my own research and just by reading virtually any alchemical text, the aspiration to a connection and understanding with the divine is a major them. It's not just something Jung made up. Alchemy WAS a practical activity, sure, but you're going all the other way, saying it was only that, when clearly, both researchers and a plain reading disagrees, balantly. Again, I really advise you to be more careful with such sweeping statements.

That's why I worded my post like this

That is why I said "well alchemy isn't about the chemicals, it's all spiritual"

Because of Jung's sloppy historiography, there are people who think entire alchemy texts have nothing to do with proto-chemistry, and are actually coded spiritual codexes. Actual history is being discarded for pseudohistory.

I'm not claiming that alchemy never involved spirituality. But Jung's work popularized the idea that alchemy was chiefly, or even solely, about spirituality. And that has done enormous damage to alchemical scholarship.

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultural domination is doubtless a major aspect of imperialist domination as such, and 'culture' is always, therefore, a major site for resistance, but cultural contradictions within the imperialized formations tend to be so very numerous - sometimes along class lines but also in cross-class configurations, as in the case of patriarchal cultural forms or the religious modes of social authorization - that the totality of indigenous culture can hardly be posited as a unified, transparent site of anti-imperialist resistance.

The difficulties of analytic procedure which arise from such complexities of the object of analysis itself are further compounded by the verv modes of thought which are currently dominant in literary debates and which address questions of colony and empire from outside the familiar Marxist positions, often with great hostility towards and polemical caricature of those positions. First, the term 'culture is often deployed as a very amorphous category - sometimes in the Arnoldian sense of 'high' culture; sometimes in the more contemporary and very different sense of 'popular culture; in more recent inflations that latter term, taken over from Anglo-American sociologies of culture, has been greatly complicated by the equally amorphous category of 'Subaltern consciousness which arose initially in a certain avant-gardist tendency in Indian historiography but then gained currency in metropolitan theorizations as well. Meanwhile, the prior use of the term 'cultural nationalism', and of other cognate terms of this kind, in Black American literary ideologies since the mid 1960s - not to speak of the Negritude poets of Caribbean and African origins, the Celtic and nativist elements in Irish cultural nationalism, or the Harlem Renaissance in the United States - then endows the term, as it is used in American literary debates, with another very wide range of densities. Used in relation to the equally problematic category of 'Third World', 'cultural nationalism' resonates equally frequently with tradition', simply inverting the tradition/modernity binary of the modernization theorists in an indigenist direction, so that 'tradition' is said to be, for the 'Third World', always better than 'modernity', which then opens up a space for defence of the most obscurantist positions in the name of cultural nationalism. There appears to be, at the very least, a widespread implication in the ideology of cultural nationalism, as it surfaces in literary theory, that each 'nation' of the Third World' has a 'culture and a 'tradition', and that to speak from within that culture and that tradition is itself an act of anti-imperialist resistance. By contrast, the principal trajectories of Marxism as they have evolved in the imperialized formations have sought to struggle - with varying degrees of clarity or success, of course - against both the nation/ culture equation, whereby all that is indigenous becomes homogenized into a singular cultural formation which is then presumed to be necessarily superior to the capitalist culture which is identified discretely with the 'West', and the tradition/modernity binary, whereby each can be constructed in a discrete space and one or the other is adopted or discarded.

Aijaz Ahmad, In Theory

#aijaz ahmad#looking at this it’s actually ‘funny’ (you know not haha funny like chortle chortle uuuugh funny)#that I consider reading this text a personal ‘back to basics’

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The winning of constitutional independence in any given African territory has to be correlated with winning of independence everywhere else on the continent and in Asia, so as to determine to what extent the so-called peaceful handover of power was really peaceful and was due to the goodness of the colonizers, and to what extent it was an option forced on them by examples of violence in particular colonies and by the threat of violence implicit in any nationalist movement which had shaped the people into a single resolute force. It is, for example, palpably obvious that the French learned from defeats in Vietnam that they should quit the whole of Indochina 'peacefully', rather than perish at other Dien Bien-Phus. The French repeated their high-handed actions in Africa and found that the national war of liberation threatened to reduce the French 100-franc note to a piece of worthless paper, and had already bequeathed the National Assembly in Paris with a succession of jack-in-the-box premiers. There was clearly a connection with the unsuccessful French wars of repression in Algeria and the haste with which they tried to establish acceptable African governments in West Africa.

As for the British, Malaya haunted them in Asia and the example of Kenya gave them diarrhoea in Africa. True, they did suppress the Mau Mau land and freedom army, but at what cost! Imperialism is not imperialism if it costs more to suppress the exploited than the imperialists receive in surplus. The British knew that it was wise to proceed with African independence rather than court more Mau Mau. Even in far-off British Guiana, the popular movement of the 1950s could exert some leverage on the British by threatening them with Mau Mau.

India is often given as the classic example of non-violent transfer of power from the imperial power to the indigenous nationalist forces. But it should be remembered that India had a powerful current of mutinous soldiers and other political traditions opposed to the non-violence of Gandhi. The British retreated as much from the threat of millions of Indians lying peacefully on the roads and railways as from the possibility that they might get up and strike back, given the example of those nationalists who were attacking British life and property before and during the Second World War."

Walter Rodney, The British Colonialist School of African Historiography and the Question of African Independence

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

You feel helpless sometimes. It comes and goes, like the waves crashing against sandy shores of your consciousness before receding back into the deep blue ocean of your subconscious.

Lately it's been more helpless than not. You can't figure out what it is, but since the new semester started a few weeks ago, your focus is faltering, organisation dropping off, grades slipping. Confiding in your friends usually helps, but they've got enough on their plates, and hearing things like "it's normal to feel that way" when you feel like you're drowning inside your own head, only makes it worse.

The professor of your history class is droning on about one thing or another while you worry. Ponder. Stress. You're not quite in the right headspace to be here; your morning was full of misplacing important objects, and you forgot to put your wet clothes un the dryer the night before, and you ended up bringing the wrong notebook with you to class.

You left your waterbottle on the kitchen bench, too.

Then your name is called.

Your heart stops. Panic pumps through your veins, running them both freezing cold and boiling hot. You look up at your professor, feel not only his eyes, but those of your peers, and time starts to drag.

"Says here 'historiography is the changing interpretations of the past, rather than studying history itself.'" Comes a voice next to your ear, projecting back to the professor. The blonde boy who sits behind you is leaning into your space, pointing to scribbles in your notepad that definitely do not say anything about the subject. "Why you always picking on the introverts? Your end of year survey is gonna be full of negative feedback, professor." He huffs, falling back into his chair as people murmur around you in agreement.

The professor sends you an apologetic look, and you feel the panic subside, but it doesn't go away completely. While your pulse slows, you still feel exhausted and deflated, like all hopes and dreams for the day are flowing down the drain.

Then a note lands on your desk, something folded into a messy square, torn from a notebook.

You owe me a coffee. You free after class?

- Bakugo

His number is scrawled under his name, and you resist the urge to turn around and ask him if he's joking, fear of being called out in front of the class again a shadow at the back of your brain.

But now you really can't focus, and it's for another reason completely. Bakugo is cute. Cuter than cute, and smart, and popular, and it takes you another whole minute to process this but... he saved your ass.

You try to steal a sneaky glance back at him, only to make eye contact with dark ruby eyes, and he winks.

328 notes

·

View notes

Text

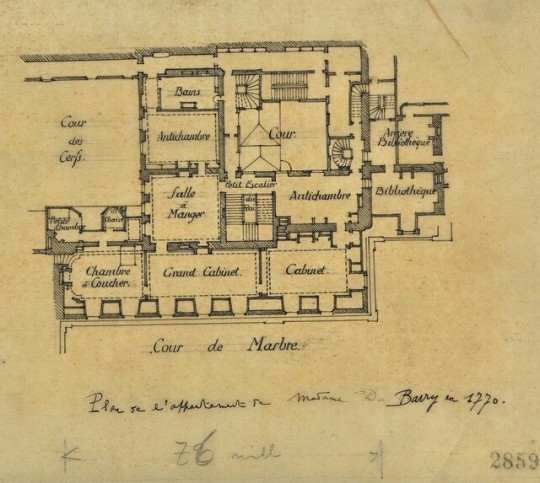

The plan for Madame du Barry's apartments in 1770. Note that she had both a chaise room (for toilet facilities) and a bain/bathroom for bathing. Du Barry's bathroom had running plumbing, a feature which Louis XV, who was known for being very strict when approving plumbing construction for bathrooms, denied to his own daughters before approving for his mistress.

Courtiers who lived at Versailles who had the space for dedicated bathrooms (which at the time were for bathing only, as bathrooms were meant to be luxury spaces, not somewhere you'd put your commode!) had to apply to the king for the construction of running plumbing.

Under Louis XV, running plumbing appeals from courtiers were rejected on the basis that he only intended to approve this type of construction for royal apartments due to the expense--except in the case of his mistresse. And he didn't always approve such requests for members of the royal family (ie, his daughters).

Under Louis XVI, approval for plumbing was notably looser. We know that the apartments of Marie Antoinette, Louis XVI, Madame Elisabeth, the comte and comtesse de Provence, the three daughters of Louis XV (Mesdames); the comte and comtesse d'Artois; and select courtiers, including the queen's favorites, the princesse de Lamballe and duchesse de Polignac, and apartments reserved for certain ministers had running plumbing. (Although Marie Antoinette's Versailles apartments did not have running plumbing until 1788-1789, and it's unknown if she ever ended up using them.)

For residents, royal or otherwise, without running plumbing but who had large enough apartments to allot dedicated bathrooms, tub bathing would have been done with tubs that were brought into these rooms and filled by servants. This is how Marie Antoinette bathed when she took immersion baths:

Campan:

... a slipper bath was rolled into her room, and her bathers brought everything that was necessary for the bath. The Queen bathed in a large gown of English flannel buttoned down to the bottom; its sleeves throughout, as well as the collar, were lined with linen.

For residents of Versailles who didn't have enough rooms for a dedicated bathroom, tubs were rolled into their regular room(s) and filled by servants.

For servants who had tiny apartments that were basically just small rooms often big enough for a bed, a desk and a drawer, they would have used wash basins for regular washing, as everyone (including aristocrats) did for daily hygiene.

Image: A well-to-do woman being washed by a servant using a wash basin.

I don't think it would have been impossible for some servants to have had standing rolling tubs that they might have split among others, as people of modest means outside of Versailles would have done. But since documentation of 'lower servant' life at Versailles is limited, it's hard to say. They could have also gone to nearby rivers or lakes to bathe if they wanted full immersion baths. Louis XIV was known for bathing in rivers, especially after the hunt.

People, particularly aristocratic women who could afford specialized pieces like this, would have also used bidets to regularly clean their private parts.

Oops I just meant to add the note about Du Barry getting running plumbing when Louis XV rejected his own daughters' requests for running plumbing, but have this other information too.

I am slowly working on a proper article about the myriad of popular culture myths about Versailles and hygiene, hopefully I will be able to sit down and force myself to finish it soon. Working on this particular article has definitely forced me to re-evaluate the general lack of solid historiography on the subject, even from historians that ought to be trusted to analyze and vet sources more seriously.

#versailles#french history#18th century#madame du barry#louis xvi by comparison was like#you get plumbing! you get plumbing! and you get plumbing!

124 notes

·

View notes

Note

I see you talk a lot about historiography! What would you consider the most important development of Alexander’s historiography?

What the Hell is Historiography? (And why you should care)

This question and the next one in the queue are both going to be fun for me. 😊

First, some quick definitions for those who are new to me and/or new to reading history:

Historiography = “the history of the histories” (E.g., examination of the sources themselves rather than the subject of them…a topic that typically incites yawns among undergrads but really fires up the rest of us, ha.)

primary sources = the evidence itself—can be texts, art, records, or material evidence. For ancient history, this specifically means the evidence from the time being studied.

secondary sources = writings by historians using the primary evidence, whether meant for a “regular” audience (non-specialists) or academic discussions with citations, footnotes, and bibliography (sometimes referred to as “full scholarly apparatus”).

For ancient history, we also sometimes get a weird middle category…they’re not modern sources but also not from the time under discussion, might even be from centuries after the fact. Consider the medieval Byzantine “encyclopedia” called the Suda (sometimes Suidas), which contains information from now lost ancient sources, finalized c. 900s CE. To give a comparison, imagine some historian a thousand years from now studying Geoffry Chaucer from the 1300s, using an entry about him in some kid’s 1975 World Book Encyclopedia that contains information that had been lost by his day.

This middle category is especially important for Alexander, since even our primary sources all date hundreds of years after his death. Yes, those writers had access to contemporary accounts, but they didn’t just “cut-and-paste.” They editorialized and selected from an array of accounts. Worse, they rarely tell us who they used. FIVE surviving primary Alexander histories remain, but he’s mentioned in a wide (and I do mean wide) array of other surviving texts. Alas this represents maybe a quarter of what was actually written about him in antiquity.

OKAY, so …

The most important historiographic changes in Alexander studies!

I’m going to pick three, or really two-and-a-half, as the last is an extension of the second.

FIRST …decentering Arrian as the “good” source as opposed to the so-called “vulgate” of Diodoros-Curtius-Justin as “bad” sources.

Many earlier Alexander historians (with a few important exceptions [Fritz Schachermeyr]) considered Arrian to be trustworthy, Plutarch moderately trustworthy if short, and the rest varying degrees of junk. W. W. Tarn was especially guilty of this. The prevalence of his view over Schachermeyr’s more negative one owed to his popularity/ease of reading, and the fact he wrote on Alexander for volume 6 of the first edition (1927) of the Cambridge Ancient History, later republished in two volumes with additions (largely in vol. 2) in 1948 and 1956. Thus, and despite being a lawyer (barrister) not a professional historian, his view dominated Alexander studies in the first half of the 20th century (Burn, Rose, etc.)…and even after. Both Mary Renault and Robin Lane Fox (neither of whom were/are professional historians either), as well as N. G. L. Hammond (with qualifications), show Tarn’s more romantic impact well into the middle of the second half of the 20th century. But you could find it in high school and college textbooks into the 1980s.

The first really big shift (especially in English) came with a pair of articles in 1958 by Ernst Badian: “The Eunuch Bagoas,” Classical Quarterly 8, and “Alexander the Great and the Unity of Mankind,” Historia 7. Both demolished Tarn’s historiography. I’ve talked about especially the first before, but it really WAS that monumental, and ushered in a more source-critical approach to Alexander studies. This also happened to coincide with a shift to a more negative portrait of the conqueror in work from the aforementioned Schachermeyr (reissuing his earlier biography in 1973 as Alexander der Grosse: Das Problem seiner Persönlichtenkeit und seines Wirkens) to Peter Green’s original Alexander of Macedon from Thames and Hudson in 1974, reissued in 1991 from Univ. of California-Berkeley. J. R. Hamilton’s 1973 Alexander the Great wasn’t as hostile, but A. B. Bosworth’s 1988 Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great turned back towards a more negative, or at least ambivalent portrait, and his Alexander in the East: The Tragedy of Triumph (1996) was highly critical. I note the latter two as Bosworth wrote the section on Alexander for the much-revised Cambridge Ancient History vol. 6, 1994, which really demonstrates how the narrative on Alexander had changed.

All this led to an unfortunate kick-back among Alexander fans who wanted their hero Alexander. They clung/still cling to Arrian (and Plutarch) as “good,” and the rest as varying degrees of bad. Some prefer Tarn’s view of the mighty conqueror/World unifier/Brotherhood-of-Mankind proponent, including that He Absolutely Could Not Have Been Queer. Conversely, others are all over the romance of him and Hephaistion, or Bagoas (often owing to Renault or Renault-via-Oliver Stone), but still like the squeaky-nice-chivalrous Alexander of Plutarch and Arrian.

They are very much still around. Quite a few of the former group freaked out over the recent Netflix thing, trotting out Plutarch (and Arrian) to Prove He Wasn’t Queer, and dismissing anything in, say, Curtius or Diodoros as “junk” history. But I also run into it on the other side, with those who get really caught up in all the romance and can’t stand the idea of a vicious Alexander.

It's not necessary to agree with Badian’s (or Green’s or Schachermeyr’s) highly negative Alexander to recognize the importance of looking at all the sources more carefully. Justin is unusually problematic, but each of the other four had a method, and a rationale. And weaknesses. Yes, even Arrian. Arrian clearly trusted Ptolemy to a degree Curtius didn’t. For both of them, it centered on the fact he was a king. I’m going to go with Curtius on this one, frankly.

Alexander is one of the most malleable famous figures in history. He’s portrayed more ways than you can shake a stick at—positive, negative, in-between—and used for political and moral messaging from even before his death in Babylon right up to modern Tik-Tok vids.

He might have been annoyed that Julius Caesar is better known than he is, in the West, but hands-down, he’s better known worldwide thanks to the Alexander Romance in its many permutations. And he, more than Caesar, gets replicated in other semi-mythical heroes. (Arthur, anybody?)

Alfred Heuss referred to him as a wineskin (or bottle)—schlauch, in German—into which subsequent generations poured their own ideas. (“Alexander der Große und die politische Ideologie des Altertums,” Antike und Abendland 4, 1954.) If that might be overstating it a bit, he’s not wrong.

Who Alexander was thus depends heavily on who was (and is) writing about him.

And that’s why nuanced historiography with regard to the Alexander sources is so important. It’s also why there will never be a pop presentation that doesn’t infuriate at least a portion of his fanbase. That fanbase can’t agree on who he was because the sources that tell them about him couldn’t agree either.

SECOND …scholarship has moved away from an attempt to find the “real” Alexander towards understanding the stories inside our surviving histories and their themes. A biography of Alexander is next to impossible (although it doesn’t stop most of us from trying, ha). It’s more like a “search” for Alexander, and any decent history of his career will begin with the sources. And their problems.

This also extends to events. I find myself falling in the middle between some of my colleagues who genuinely believe we can get back to “what happened,” and those who sorta throw up their hands and settle on “what story the sources are telling us, and why.” Classic Libra. 😉

As frustrating as it may sound, I’m afraid “it depends” is the order of the day, or of the instance, at least. Some things are easier to get back to than others, and we must be ready to acknowledge that even things reported in several sources may not have happened at all. Or at least, were quite radically different from how it was later reported. (Thinking of proskynesis here.) Sometimes our sources are simply irreconcilable…and we should let them be. (Thinking of the Battle of Granikos here.)

THIRD/SECOND-AND-A-HALF …a growing awareness of just how much Roman-era attitudes overlay and muddy our sources, even those writing in Greek. It would be SO nice to have just one Hellenistic-era history. I’d even take Kleitarchos! But I’d love Marsyas, or Ptolemy. Why? Both were Macedonians. Even our surviving philhellenic authors such as Plutarch impose Greek readings and morals on Macedonian society.

So, let’s add Roman views on top of Greek views on top of Macedonian realities in a period of extremely fast mutation (Philip and Alexander both). What a muddle! In fact, one of the real advantages of a source such as Curtius is that his sources seem to have known a thing or three about both Achaemenid Persia and also Macedonian custom. He sometimes says something like, “Macedonian custom was….” We don’t know if he’s right, but it’s not something we find much in other histories—even Arrian who used Ptolemy. (Curtius may also have used Ptolemy, btw.)

In any case, as a result of more care given to the themes of the historians, a growing sensitivity to Roman milieu for all of them has altered our perceptions of our sources.

These are, to me, the major and most significant shifts in Alexander historiography from the late 1800s to the early 2100s.

#asks#historiography#alexander the great#arrian#curtius#plutarch#diodorus#justin#w.w. tarn#fritz schachermeyr#a.b. bosworth#peter green#n.g.l. hammond#mary renault#robin lane fox#j.r. hamilton#ernst badian#classics#ancient history#ancient macedonia

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something that strikes me is that, I think, a lot of pre-modern literary works weren't theory conscious in the way that modern litfic is. Like, litfic is written in large part by the sort of people who like to think about literature, and so it seems like a lot of it is written very explicitly "to the frameworks". It's written to be interpreted by other literary theorists. Now, this kind of theory awareness is characteristic of some pre-modern literature (although, of course, not with regard to the same set of frameworks that motivate modern litfic authors). A lot of historical Chinese literature, for instance, seems to have been written very consciously with Confucian historiography and Classical Chinese literary scholarship in mind. But a lot of pre-modern literature isn't like this.

I was thinking about this in the context of Beowulf, which strikes as like... well, it's not consciously "about" anything in the way that modern litfic is "about" things, and there are a lot of failed attempts to analyze Beowulf by positing that it is. I think, realistically, Beowulf is mostly just... a juicy story. It doesn't exist to be analyzed, it exists to be told and to be heard. And I think, like, that's the nature of most writing, obviously. That's the way popular works of fiction have always been. But I think when it comes to these prestigious classical works, literary scholars can sometimes fail in assigning them, like, too much agency in their own interpretation. Agency that was never really there. Does that make sense?

I don't know.

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snow and Dirty Rain (Merlin)

Richard Silken, "Snow and Dirty Rain" // BBC Merlin

Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3 / Part 4

-

it's finally here! the fourth and final part!!!

this one was hard, I had the most trouble with the last three pictures. I really wanted to include Elena and Mithian as well as Geoffrey, but they just... didn't really fit. it was objectively awful. sorry for that. so I reached out to @shana-rosee , and they threw me a few ideas! it was their call to have Geoffrey last - and they might not have realized it, but it turned out great for the symbolism, as I'll point out below. so thank you for that! (/gen) but yeah, today it was just bugging me and I NEEDED to get it done, and I think it turned out pretty good!

so the first image is alluding to part 3, where the line "if this isn't a kingdom, i don't know what is" is assigned to Arthur. for "the hunter's heart" I had the unicorn horn, because it showed that Arthur was pure of heart. for "the hunter's mouth" I had Leon, (yay! Leon!) because he's Arthur's advisor, and speaks for him.

I was DETERMINED to get Leon, Hunith, and Gaius in this one, and I'm so glad I did.

Tristan and Isolde have their line to represent, honestly, what they did in the show - a reflection of Merlin and Arthur, and how their great love (filled with magic, secrets, and war), ends in tragedy.

Hunith and Gaius are there to represent "the space between the trees", as they are Merlin's sanctuary, his parental figures, the ones who know about his magic and love him - not in spite of, but for it. and of course I had to have Gaius casting a spell for the gold line!

for the last three, it got a little complicated, but I figured it out.

for "the words frozen," I did the moment that Arthur and Merlin became officially forever connected - when Uther assigned Merlin as Arthur's servant after he saved his life. the knife in the throne, the speechless moment that followed.

for "the creatures frozen.", I had the most difficult time with. Shana suggested the Lamia, which was a great idea, but I didn't think that it quite fit with the rest. so instead, I did Dragoon at Camlann. that lightning is the moment that even a fraction of Merlin's true power is shown. Dragoon is representative of Merlin being allowed to be his true self, and the consequences that come with it. Merlin can literally freeze creatures using his words - a la spells, or, more fitting, dragonspeak. people also freeze in terror or awe at the very mention of the name Emrys. so yeah, I think it worked out quite well!

and lastly, for "Explaining will get us nowhere." as i said, Shana suggested Geoffrey here, likely because of his love of the library. that reason was actually why I considered putting him under "the words frozen," but I realized putting him last was much better. why?

well, because Geoffrey of Monmouth was a real person. who, you ask, exactly is he? well, just "one of the major figures in the development of British historiography and the popularity of tales of King Arthur." yeah, in case you didn't know, Geoffrey the record keeper in BBC Merlin was an allusion to the man who helped carry Arthur's tale throughout the years.

so, why "explaining will get us nowhere?" well, because, if you accept BBC's Merlin as the true canon, then Geoffrey recorded it wrong! lol.

(in line with this, if you haven't read it already, go read @katherynefromphilly 's We Begin Again series. it's absolutely incredible, well worth the long read, and will leave you wanting more! in a good way, I promise. in it, Merlin in the present day goes out of his way to fix everything history got wrong, and it's incredible. also I distinctly remember there being fish in little pond things indoors, which was a super cute detail.)

-

so, that's the last of my Snow and Dirty Rain/Merlin series. I went a little overboard explaining things, but it was just so fun finding and linking the symbolism!! I hope you all enjoyed!

(p.s. I'm planning to make more of Snow and Dirty Rain, but with twelveclara/whouffaldi from Doctor Who. if you're interested in that or other things I make, check out my richard siken or original post tags in my blog.)

#bbc merlin#original post#richard siken#poetry#merlin#arthur#arthur pendragon#merlin emrys#dragoon#dragoon the great#leon#leon the long suffering#sir leon the long suffering#tristan and isolde#hunith#gaius#merthur#geoffrey#geoffrey of monmouth#snow and dirty rain#I'm sorry I didn't include you elena and mithian#I love you I promise#content creator#sort of#we begin again#love that fic sm

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

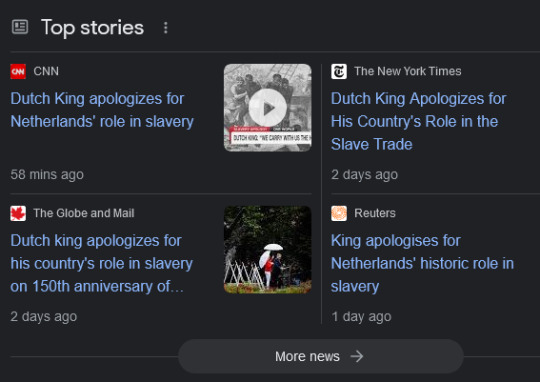

“Dutch King apologizes for Netherlands’ role in slavery.”

The Dutch/Netherlands abducted slaves from West Africa; hosted the Dutch West India Company; operated an extensive profitable sugar plantation industry built on slave labor; and established colonies in the greater Caribbean region including sites at Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten, Bonaire, and the adjacent “Wild Coast” (land between the Orinoco and Amazon rivers, including Guyana and Suriname). Many of these places remained official colonies until between the 1950s and 1990s.

---

Scholarship on resistance to Dutch practices of slavery, colonialism, and imperialism in the Caribbean:

“Decolonization, Otherness, and the Neglect of the Dutch Caribbean in Caribbean Studies.” Margo Groenewoud. Small Axe. 2021.

“Women’s mobilizations in the Dutch Antilles (Curaçao and Aruba, 1946-1993).” Margo Groenewoud. Clio. Women, Gender, History No. 50. 2019.

“Black Power, Popular Revolt, and Decolonization in the Dutch Caribbean.” Gert Oostindie. In: Black Power in the Caribbean. Edited by Kate Quinn. 2014.

“History Brought Home: Postcolonial Migrations and the Dutch Rediscovery of Slavery.” Gert Oostindie. In: Post-Colonial Immigrants and Identity Formations in the Netherlands. Edited by Ulbe Bosma. 2012.

“Other Radicals: Anton de Kom and the Caribbean Intellectual Tradition.” Wayne Modest and Susan Legene. Small Axe. 2023.

Di ki manera? A Social History of Afro-Curaçaoans, 1863-1917. Rosemary Allen. 2007.

Creolization and Contraband: Curaçao in the Early Modern Atlantic World. Linda Rupert. 2012.

“The Empire Writes Back: David Nassy and Jewish Creole Historiography in Colonial Suriname.” Sina Rauschenbach. The Sephardic Atlantic: Colonial Histories and Postcolonial Perspectives. 2018.

“The Scholarly Atlantic: Circuits of Knowledge Between Britain, the Dutch Republic and the Americas in the Eighteenth Century.” Karel Davids. 2014. And: “Paramaribo as Dutch and Atlantic Nodal Point, 1640-1795.” Karwan Fatah-Black. 2014. And: Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680-1800: Linking Empires, Bridging Borders. Edited by Gert Oostindie and Jessica V. Roitman. 2014.

Decolonising the Caribbean: Dutch Policies in a Comparative Perspective. Gert Oostindie and Inge Klinkers. 2003. And: “Head versus heart: The ambiguities of non-sovereignties in the Dutch Caribbean.” Wouter Veenendaal and Gert Oostindie. Regional & Federal Studies 28(4). August 2017.

Tambú: Curaçao’s African-Caribbean Ritual and the Politics of Memory. Nanette de Jong. 2012.

“More Relevant Than Ever: We Slaves of Suriname Today.” Mitchell Esajas. Small Axe. 2023.

“The Forgotten Colonies of Essequibo and Demerara, 1700-1814.” Eric Willem van der Oest. In: Riches from Atlantic Commerce: Dutch Transatlantic Trade and Shipping, 1585-1817. 2003.

“Conjuring Futures: Culture and Decolonization in the Dutch Caribbean, 1948-1975.” Chelsea Shields. Historical Reflections / Reflexions Historiques Vol. 45 No. 2. Summer 2019.

“’A Mass of Mestiezen, Castiezen, and Mulatten’: Fear, Freedom, and People of Color in the Dutch Antilles, 1750-1850.” Jessica Vance Roitman. Atlantic Studies 14, no. 3. 2017.

---

This list only covers the Caribbean.

But outside of the region, there is also the legacy of the Dutch East India Company; over 250 years of Dutch slavers and merchants in Gold Coast and wider West Africa; about 200 years of Dutch control in Bengal (the same region which would later become an engine of the British Empire’s colonial wealth extraction); over a century of Dutch control in Sri Lanka/Ceylon; Dutch operation of the so-called “Cultivation System” (”Cultuurstelsei”) in the nineteenth century; Dutch enforcement of brutal forced labor regimes at sugar plantations in Java, which relied on de facto indentured laborers who were forced to sign contracts or obligated to pay off debt and were “shipped in” from other islands and elsewhere in Southeast Asia (a system existing into the twentieth century); the “Coolie Ordinance” (”Koelieordonnanties”) laws of 1880 which allowed plantation owners to administer punishments against disobedient workers, resulting in whippings, electrocutions, and other cruel tortures (and this penal code was in effect until 1931); and colonization of Indonesian islands including Sumatra and Borneo, which remained official colonies of the Netherlands until the 1940s.

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Black Rider: Nikolaos Plastiras

Colonel Nikólaos Plastiras (1883 - 1953) was a general and politician, who served twice as the Prime Minister of Greece. He was a politically conflicting or, even, confusing leader who however was very popular at his time. Contemporary historiography evaluates Plastiras as neither a particularly competent politician nor perceptive enough for such a position, however historians agree he was a rare example of a prominent man being very notable for his sense of honour, lawfulness and temperance.

Plastiras fought in the Macedonian Struggle, the Balkan Wars, the National Defense Movement (against the King), World War I, alongside the Allies in the war of the Red and the White Army in Ukraine. Due to his distinction in battle, he earned the name "Ο Μαύρος Καβαλάρης" (O Mávros Kavaláris), "the Black Rider".

Source: mixanitouxronou.gr

In 1922, Plastiras' Regiment was transferred to Smyrna (Izmir) during the Greco-Turkish War. Plastiras was the only anti-King officer that was not dismissed from the army, simply because his Regiment threatened they wouldn't fight under any other commander. While the war ended with Greece's defeat, Plastiras was singled out and called by the Turks as "Kara Biber" (Black Pepper) and his Regiment as "Şeytanın Askerleri" (the Satan's Army).

After the defeat, Plastiras along with Colonel Stylianos Gonatas and Commander Phokas organized the September 1922 Revolution which led to King Constantine I's resignation and the return of the exiled politician Eleftherios Venizelos. His most controversial moment was the "Trial of the Six" (Η Δίκη των Έξι) were six officers were deemed as the major culprits of the disastrous war for Greece, partly due to their blind devotion to the King and their contempt against the popularity of Venizelos. They were condemned to death.

Once, his brother, Giorgos Plastiras, 60 years old at that point, asked for a job in a FIX beer factory. Hearing his surname, they asked him whether he was related to the PM. His brother admitted it but begged them to keep it a secret from him. They agreed and hired him immediately. However, as it happens, a few days later it was all over the news. Plastiras, furious, called his brother to his house and scolded him for getting a job relying on the family name. He counter-proposed that if his brother had financial issues, he should stay with him and share the food.

Plastiras was chronically ill and he lived in a tiny house in Mets (unthinkable for a politician and twice PM). Once, somebody suggested to set up a landline phone for him. Plastiras refused. "How do you even suggest this? Greece will be in poverty while I get to enjoy my phone!?"

Plastiras adopted five orphans from men who fell in battle. He never married and had no biological children.

One night of August 1922, during the Greek army's retreat from Asia Minor, the soldiers were so exhausted that they all fell asleep. When they woke up the next morning, they saw Plastiras on his horse, guarding them. They asked him, "Sir, you - our commander - are standing guard over us?!". Plastiras replied; "I am riding and I am well rested. You travel on foot and carry the supplies. If I don't protect you, then who ought to?"

The publisher of two prominent to this day newspapers (ΒΗΜΑ and ΝΕΑ) once gifted an expensive golden pen to Plastiras. Plastiras refused the gift. When his secretary argued that the publisher might get offended, Plastiras insisted. "I do not need to sign in gold. My little pen is enough. I don't want gifts. For those who make gifts often expect 'gifts in return' (=implied he suspected bribery)".

Plastiras was once visited by Queen Frederica of Greece (daughter-in-law of the king he so fought). She was shocked by the state of his humble home. She asked him why he was sleeping in a cheap camp bed. Plastiras replied that he was used to it since his military days and that many people in the country lived in far worse conditions after all.

Nikolaos Plastiras slept with three frames on the wall over his bed; an icon of Saint Nicholas (his namesake), a painting of French Revolutionists in 1789 and an image of Eleftherios Venizelos!

Plastiras' will to an adopted daughter included the following, which were all his possessions at the time of his death: 216 drachmas, a 10 dollar bill and a note reading "All for Greece". There was also a military receipt charging him with 8 drachmas for a bed he'd lost during the wars. The receipt was accompanied with the amount of money required, with Plastira's requirement to be granted to the public sector, so that he wouldn't die "owing to the Fatherland".

Plastiras was a centrist who often collaborated with liberals and leftists at a time the left was tragically marginalised, at least to the degree that didn’t threaten his own position much. He was likely Venizelos' ultimate fanboy, he was a fierce anti-royalist and loathed the dictatorship of Metaxas. He tried to prevent the Civil War but failed. He was the first one to use the term "Civil War" at a time when others still called it "bandit war", to put the entire blame on the communists. During the war, Plastiras condemned both the Left and the Right for their actions which led to "kin killing kin". As a politician, Plastiras was a pacifist wishing for the unity of the Greek people, but he did not succeed much.

After his death, his body was found to have 27 sword scars and 9 wounds from bullets. His heart was removed and preserved. It was wrapped in a Greek flag and sent to his homeland, Karditsa, as was his wish. His heart is in the Folk Museum of Karditsa.

His heart is kept in a golden capsule in the museum.

Tavropós lake, the lake of Karditsa and a famous artificial lake of Thessaly, was attributed to him. Once, Plastiras was visiting his home Karditsa during severe rainfalls that caused destructive floods in the region. Plastiras looked at the flooded region and said: "This place will become a lake someday". The project for the creation of the lake started a few years later. The lake's actual name is Lake of Tavropós but it is best known as Plastiras' Lake.

Plastiras Lake

#greece#europe#history#Greek history#people#European history#20th century#Greek people#modern Greek history#nikolaos plastiras

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the tea on Sheila Fitzpatrick? Haven't gotten around to any of her work yet

Sheila Fitzpatrick is one of the prominent historians of the "revisionist" school of the Soviet Union, which emerged as a response to the "totalitarian" or "traditionalist" school that was prominent earlier, such as Robert Conquest. Fitzpatrick's most notable contributions to history come from the perspective of the lower classes of the Soviet Union, that the Soviet Union was not a singular ideological monolith driven from the top-down and that it had to respond to social forces within its own nation. In many ways, it's actually a welcome revision from the 1950's era of Soviet historiography, and the scholarship produced has increased the overall level of historical understanding.

For herself, Sheila Fitzpatrick is perhaps most notable for her "people's history" of the Soviet Union, one divorced from ideology and focused mostly on social mobility and the experiences of the peasantry and line workers. Perhaps most controversially (and what I was referencing in the earlier post), is that Fitzpatrick contends that the Great Purge and Stalinism was an albeit brutal form of democratic revolution, due to the people that were able to move into the places of those purged and experience social advancement. Stalin secured a way of public buy-in through a newly-empowered cadre of middle-class individuals to achieve legitimacy for his government and secure popular buy-in.