#progressive dissent

Photo

DISSENT MAGAZINE

At critical times, foreign wars have tested the moral convictions of American leftists and affected the fate of their movement for years to come. The Socialist Party’s opposition to entering the First World War provoked furious state repression but later gained a measure of redemption when Americans learned that U.S. troops had not made the world safe for democracy after all. Leftists proved prescient again in the late 1930s when they rallied to defend the Spanish Republic against a right-wing military and its fascist allies, Italy and Germany. The republic’s defeat emboldened Adolf Hitler to launch what quickly became the Second World War. When, twenty years later, American Communists backed the Soviet Union’s crushing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, they shoved their party firmly and irrevocably to the margins of political life, which opened up space for the emergence of a New Left that rejected imperial aggressors of all ideological persuasions.

The war in Ukraine has a good chance of turning into another such decisive event. Who to blame for the bloodshed in that country should be obvious: a massive nation led by an authoritarian ruler with one of the world’s largest militaries at his disposal is seeking to conquer and subjugate a smaller and weaker neighbor. In pursuit of that vicious purpose, Vladimir Putin’s soldiers have committed countless rapes and acts of torture. His air force is systematically trying to destroy Ukraine’s infrastructure and economy, hoping to undermine its citizens’ will to resist. Yet Ukrainians, with the aid of arms from the United States and other NATO countries, have so far managed to fight this superior force to a stalemate.

A sizeable number of American leftists have embraced an alternate reality. For them, the culprit is NATO’s post–Cold War expansion, fueled by the drive of the U.S. state and capital to bend the world to their desires. The popular author and journalist Chris Hedges cracks that the war in Ukraine “doesn’t make any geopolitical sense, but it’s good for business.” The Green Party condemns the “perpetual war mentality” of the “US foreign policy establishment” and concludes, “There are no good guys in this crisis.”

These critics ignore or dismiss the fact that every nation that joined NATO did so willingly, knowing that Russia was capable of launching the kind of attack now underway in Ukraine. In the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s demise, the expansion of NATO may well have been too hasty. But not one of its newer members has done anything to threaten Putin’s regime. And every country that joined the alliance enjoys a democratically elected government. They contrast sharply with the handful of nations, besides Putin’s, that voted against a UN resolution last month demanding the Russians withdraw from Ukraine: Belarus, North Korea, Syria, Nicaragua, Eritrea, and Mali. All but the last are one-party dictatorships, and Mali relies on Russian mercenaries to battle Islamist rebels.

It seems not to bother these leftists that they are making common cause with some of the most atrocious and prominent stalwarts of the Trumpian right. Tucker Carlson routinely bashes the U.S. commitment to Ukraine with lines like “Has Putin ever called me a racist?” while Marjorie Taylor Greene recently declared, “I’m completely against the war in Ukraine. . . . You know who’s driving it? It’s America. America needs to stop pushing the war in Ukraine.”

On February 19, some members of the alliance of right and left staged a demonstration at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington to vent its “Rage Against the War Machine.” Speakers included Ron Paul and Tulsi Gabbard as well as Jill Stein, the Green Party’s 2016 nominee for president, and Medea Benjamin, the founder of Code Pink. Carlson promoted the event on the highest rated “news” show in the history of cable TV. At the Memorial, several protesters flew Russian flags.

To paraphrase August Bebel’s famous line about anti-Semitism, the hostility of those leftists who oppose helping Ukraine is an anti-imperialism of fools—although, unlike past Jew haters, they are fools with good intentions. Wars are always horrible events, no matter who starts them or why. And we on the left should do whatever we can to stop them from starting and end them when they do.

But neither the United States nor its allies forced Putin to invade. In speech after speech, he has made clear his mourning for the loss of the Soviet empire and his firm belief that Ukraine should be part of a revived one, this time sanctified by an Orthodox cross instead of the hammer-and-sickle. As the historian (and my cousin) David A. Bell wrote recently, the United States is not “the only international actor that really matters in the current crisis.” It may have the mightiest war machine, but Biden is not shipping arms to Ukraine in an attempt to subjugate Russia to his will. We should, Bell writes, “judge every international situation on its own terms, considering the actions of all parties, and not just the most powerful one. . . . the horrors Putin has already inflicted on Ukraine, and his long-term goals, are strong reasons . . . for continuing current U.S. policy, despite the attendant costs and risks.”

(Continue Reading)

#politics#the left#dissent magazine#foreign policy#war#progressive#progressive movement#Russia#ukraine#NATO#imperialism

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Quiet Part is Getting Louder

Here we have someone trying to primary a "squad"-aligned progressive Dem for being anti-genocide (in the most pro-Biden way possible!) and supporting the "uncommitted" protest votes. Because Trump. Also because Israel = Judaism, don't wanna leave the whole dual-loyalty thing out. Both sides are excusing the genocide and plugging antisemitic lies, that's where the Overton Window is at the moment. Even supporting Biden but maintaining that the genocide should stop is dangerous and suspicious.

So, here's the damage. People are silencing dissent (their own and that of others) because they want the Democrat to win. Because the Democrat MUST win to save democracy. So we're saving a "democracy" where dissenting against the ONE PARTY that MUST WIN is ANTI-DEMOCRACY. It's so fragile, dissent could END THE UNITED STATES.

Gee, that sounds like treason. Is dissent treason yet? We're dancing around the way it's phrased, but we're quietly treating it as if it's so. In big ways and little ways. Every time you ding someone for not being pro-Biden enough in their dislike of genocide, or for making sure their method of protest - FIRST AND FOREMOST! - won't hurt Biden's chances of winning.

If it's all about Biden winning, folks, Summer Lee and a lot of other progressives have got to sit down, shut up, or leave. These are the people that would support those progressive policies Biden wants (and so often fails) to push through, from the congressional level all the way down to your local school board. Taking a stand against genocide will knock down their numbers, and replace them with "centrists" who are willing to let it slide. And also willing to let a lot of other things slide.

So, what? Maybe progressives should quiet down about the genocide so they can all stay in office and keep reducing the harm, right? Maybe all of us should.

Play stupid games, win stupid prizes. Play "Silence the Dissent to Save Democracy" and win Fascism. No matter who wins, if that's HOW they win, the democracy is over. You won't be able to vote it back to life. Voting in lock-step for one party in perpetuity for God (or Good) and Country isn't democracy. You can't save democracy that way.

I can't understand why the voices insisting that's the ONLY way to save it are so damn loud. I just... What's happened to you? Is there no way to make it un-happen?

#us politics#us news#us elections#actually saving democracy will take dissent and protest and direct action#resist#if you have to tear up everything that makes democracy function to win elections wtf are you winning?#sure - we're going to get lots of progressive policy passed after weeding out as many progressives as possible#you can always always tell yourself a story about how you're making it better because you can imagine it much worse#but i can't make myself believe it#never could

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another essay about poetry.

Zach Reynolds

Dr. Chris Kocela

Engl 3840

February 9, 2013

“For the Union Dead”

Transcending the Technological

Robert Lowell strikingly juxtaposes the mechanical with the organic in “For the Union Dead,” conjuring a surreal, almost apocalyptic Boston cityscape to his readers’ minds with his images of “yellow dinosaur steamshovels” and “giant finned cars [that] nose forward like fish” to ominously portend a future where misplaced faith in machines confines human beings to a rote and sequestered existence within their own world (15, 66). Reflecting sourly on the carnage of construction, Lowell criticizes as decadent a society that recklessly delocates or discards the past to satiate the reptilian appetite of technological progress. However, besides make a scathing social commentary, Lowell also expresses interest in making progress on another scale than the technological in “For the Union Dead,” suggesting that progress on the level of mind and the soul, the consciousness, deserves prior concern to concern for technological advancement. Through his portrayal of the city of Boston undergoing the upheaval of construction for the purpose of a parking lot, Lowell provides a profound insight into the way that the tension that exists between the organic and the inorganic transitions to tension between technological progress and human progress, industrial progress and social progress.

Lowell even questions whether what he witnesses can fairly be called progress when it seems to do more to dampen the human spirit than it does to elevate it, going so far as to suggest that America’s unchecked fixation with technology and industry has imbalanced humanity so much as to cause it to devolve. His portrayal of “yellow dinosaur steamshovels” plays centrally into such an interpretation by likening the contemporary, petroleum powered tools of construction to prehistoric monsters, who, “grunting / as they crop . . . up tons of mush and grass / to gouge their underworld garage,” brutally dominate the organic landscape, reducing the greenery and the earth to rubble while they carve out a cave of concrete for their mechanical cousins, the cars, to inhabit while they await their drivers return at the end of the day (14-16). This image of machines looming over the organic like dinosaurs as they devour it and replace it with more machinery establishes a troubled relationship between the organic world that conceives humans and the machines that the humans conceive. When machines tower over their creators like dinosaurs, we must question whether their creators are any longer in control.

As he witnesses “yellow dinosaur steamshovels” trampling the earth, Lowell remarks wryly that “parking spaces luxuriate like civic / sandpiles in the heart of Boston,” and “a girdle of orange, Puritan-pumpkin colored girders / braces the tingling Statehouse, / shaking over the excavations” (17-21). With the word play in these lines, Lowell comments on the spectacle that industry makes of State, effectively mocking the institution founded to represent the organic body of the people by dressing it in the gaudy, garish colors of a hazard zone, while the Statehouse itself appears to succumb to ecstatic palpitations within the powerful, libidinous embrace of the industry that captivates it. Besides suggesting something sordid about the relationship between industry and the State, Lowell criticizes the values that earn emphasis in his historic American city by illuminating the insensitivity of “a commercial photograph” “on Boylston Street” that “shows Hiroshima boiling / over a Mosler Safe, the ‘Rock of Ages’ / that survived the blast” (55-58). Not only do burgeoning parking spaces pollute “the heart of Boston,” so does a billboard brazenly exploiting human tragedy on an unprecedented scale for the sake of advertising.

Beyond expressing his disgust for the barbarity of commercialism, which in of itself represents a pervasive collapse in the level of discourse that informs American culture, Lowell issues an exhortation by documenting the Mosler Safe advertisement, condemning the mentality behind the propaganda that extols the product of an assembly-line industry, the Mosler Safe, as “the ‘Rock of Ages’ / that survived the blast.” Such a casual substitution of technology for theology frightens the poet who, “pressed against the new barbed and galvanized / fence on the Boston Common” watches the “yellow dinosaur steamshovels . . . grunting” as they work hard at paving over the landscape to propagate their ascending kingdom (12-13). “Pressed against the new barbed and galvanized” encasement of one of the last remaining organic spaces in Boston, Lowell can only watch as machines tower inhumanly over his city, brutally transforming it before his eyes.

Every time the poet portrays technology in “For the Union Dead,” he portrays it as destructive, savage, monstrous. Opposite of the Statehouse, girded in cautionary colors, “tingling” and “shaking over the excavations,” stands a monument to “Colonel Shaw / and his bell-cheeked Negro infantry,” a “shaking Civil War relief, / propped by a plank splint against the garage’s earthquake” (21-24). The memorial here has casually been cast aside to make room for the ongoing construction of the parking lot, nearly lost in the rubble of earth uprooted by the steamshovels’ excavations. Symbolically, the monument functions on multiple levels. As a symbol of the past, it represents Boston’s heritage tossed aside and nearly forgotten to heed the higher calling of technological progress. As an effigy of men, the half-buried monument symbolizes the way in which technological progress tramples over and takes priority over human progress. Yet, Lowell says that the “monument sticks like a fishbone / in the city’s throat” to remark on the way that the monument to the 54th Massachusetts Infantry stands for an uncomfortable reminder of a conflict that not only set the country to civil war in the past, but one that echoes persistently into the political climate of Lowell’s present (29-30).

Glowering from his position beside the abandoned South Boston Aquarium as he surveys the carnage of construction that displaces the monument of Colonel Shaw’s brigade to construct a metropolis of machinery that brazenly trivializes the value of human life with displays like the advertisement that shows “Hiroshima boiling / over a Mosler Safe,” Lowell remarks scornfully that “Shaw’s father wanted no monument / except the ditch / where his son’s body was thrown / and lost with his ‘ni--ers,’” recalling the mass grave outside of Fort Wagner where confederates buried Colonel Shaw with his infantry in an attempt to insult his memory (49-52). Regarding the state of the statue as it stands presently, half-buried by rubble, insouciantly leaning against a “plank splint against the garage’s earthquake,” Lowell decries that “The ditch is nearer,” the mass grave where Colonel Shaw physically lies buried with his troops serves as a better memorial to the abolitionist’s fight than does the monument lost among the burgeoning metropolis (53).

Lowell’s brooding lamentation for the forgotten 54th Massachusetts infantry carries over into the present when he declares “There are no statues for the last war here,” but rather “a commercial photograph / shows Hiroshima boiling / over a Mosler Safe” (54). Thus, the poet suggests that a denial mentality pervades the spirit of progress in America, because despite the systemized atrocity of the Holocaust and the cataclysmic impact of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, events which exemplify the spiraling trajectory of technology and the insensitivity of science to human suffering, Lowell witnesses a world undeterred in its pursuit of material progress, a world utterly unconcerned with the ethical ramifications of selling a safe with a depiction of the atomic blast that murdered thousands in Japan. Rather than the mockery of a monument to the lives lost in the Hiroshima bombing represented by the “commercial photograph,” Lowell declares that “Space is nearer,” suggesting that the suffocating vacuum of the void better serves the memories of the massacred Japanese than does the affront of the Mosler ad (58).

The poet feels disturbed by the emphasis that his culture places on making technological progress at the expense of all else when the horrific memory of the recent war still lingers in his mind. Emphasizing technological progress means emphasizing the value of the material, of wealth. It indicates a continuation of the trends that began with industrialism and lead to imperialism. But progress made strictly for the sake of advancing the wealth of materials in an already materialistic society does not satisfy Lowell. Contrarily, it alarms him since he can see all of the ways in which materialistic progress passes over, and even discourages progress on the human scale, progress in the spheres of the social and the spiritual. Even what little human progress the poet does see taking place is relegated, so that, during even a moment as monumental to the civil rights movement as the desegregation of schools in the South, he must “crouch to [his] television set” to watch “the drained faces of Negro school-children rise like balloons” as they finally win a victory for social progress (59-60). The poet chooses to record the desegregation event on the heels of his record of the Mosler Safe ad, and his decree that “Space is nearer,” to reinforce how suffocating the constrictions of machinery are to such moments of human progress, moments which, resisting the clockwork regularity of the established social order, upset the balance of the machinery that it supports.

Relegated to the television set, “the drained faces of Negro school-children” are encased in a bubble alongside “Colonel Shaw,” who, “riding on his bubble, / . . . waits / for the blessed break;” together, they wait for an explosion of social awareness to arrive and bring them fresh air (61-64). Lowell deviates from his sad meditation on the state of affairs in his land for just a moment to dream of a future where the sacrifices of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry and the tribulations of the Negro school-children are not lost and forgotten within the machinery of an exploding urban sprawl. He implies by contrast to the grim vision of the apocalypse that dominates “For the Union Dead” his desire to see a growth in the human side of progress, seeking to confront the rapidly changing present with the past that it so carelessly discards. Thus, after Lowell opens the poem on an image where “the old South Boston Aquarium stands / in a Sahara of snow now” with “its broken windows . . . boarded,” he swiftly flashes back to the past, when, as a child visiting the aquarium, his “nose crawled like a snail on the glass,” and his “hand tingled / to burst the bubbles / drifting from the noses of the cowed, compliant fish” (1-2, 4-7). By interposing his memory of the past onto the reality of the present that confronts him, Lowell challenges the officially sanctioned unidirectional flow of time that seeks to relegate events that exist in history to a bubble.

Resisting the societal imperative that dictates time should only flow in one direction, the present Lowell, reflecting on the child Lowell, likewise tingles with a desire to “burst the bubble” that the present relegates to the past. He wishes to burst the bubble encapsulating Colonel Shaw and “the drained faces of Negro school-children” stifling for air. He wishes, most of all, “to burst the bubbles / drifting from the noses of the cowed, compliant fish” that substitute the people who, in the grim future where “The Aquarium is gone” depicted in the final lines of the poem, doze stupidly sequestered inside their machines as “Everywhere, / giant finned cars nose forward like fish,” trapped by “a savage servility” that “slides by on grease” (65-68). Thus, Lowell cautions against setting humanistic progress secondary to the overbearing trajectory of technological progress by suggesting that human beings will devolve when he conflates his childhood memory of the South Boston Aquarium with a vision of the future where technology confines human beings to lives that have all of the freedom to range as do fish living inside of an aquarium.

Breaking loose of the restrictions of the machinery that regulates the way we perceive time becomes essential to Lowell in his meditation in “For the Union Dead” on social consciousness. Only through tracing a disjointed path through the present and the past can the poet speculate about what lies in store for his society in the future. Though he fearfully portends a future where people devolve into “cowed, compliant fish,” Lowell himself traces an evolution in his consciousness through the construction of his poem. He recognizes that to rise above the technology that invariably seeks to tie him down, he has to discard his most fundamental programming of linear temporality, a kind of mental technology instilled in him since birth, in order to embrace a more organic method of measuring time – one which operates on a frequency more in sync with the biology of his memory and his mind. This involves embracing a perception of temporality that is inclusive and three dimensional. Making this evolutionary leap in his awareness allows the poet to perceive reality in the way that he does in “For the Union Dead,” for he no longer stands within a bubble of temporality constrained only to the present.

Despite the personal evolution memorialized by his masterful tension of tenses in “For the Union Dead,” Lowell struggles with despair when he envisions the future of American society. He cannot help but to fear for the death of the organic as he watches the “dinosaur steamshovels” inexorably erecting their mechanical kingdom, acknowledging as his “hand draws back” from the memory of his cherished innocence that he will “often sigh still / for the dark downward and vegetating kingdom / of the fish and reptile;” he cannot shut out his awareness of the stagnation, the devolution of the organic kingdom that he witnesses collapsing around him (9-11). He cannot help but to feel let down by his America’s unrelenting obsession with machinery when he sees so much at stake. His language rises to a pitch of almost shrill dejection as he portends the “savage servility” of humanity’s rote and sequestered existence in the future, and readers of Lowell fifty years later may accurately herald his voice as prophetic when envisioning the congestions of mass transit that clog our country’s arteries today.

Indeed, in light of Lowell’s exhortations about the relationship of technology to the State, to humanity, to the organic Earth which today we blithely accept for its pollution, it is difficult not to hear a vein of prophecy within Lowell’s voice. Consider, for example, just how the metaphor of the aquarium fits with the mushrooming relegations of human socialization to computerized exchange, where, “like a snail on the glass” our “nose[s] crawl” like “cowed, compliant fish,” feeding on bite-sized exchanges of information. Or, consider how along with the fixation on making technology ever better and faster, the desire for instant gratification in our tech-driven culture continues to grow to transcend all others, warping our perception of the present moment by conditioning our patience to grow ever shorter, imposing on every instant the expectation for the end to arrive immediately with no consideration for the means, disintegrating our cognitive faculty for retention as the necessity for memorization dwindles inside an increasingly shrinking sphere of specialization. Verily, humanity today more resembles the fish that Lowell feared would replace them than even he likely could have imagined.

Works Cited

Lowell, Robert. “For the Union Dead.” The Norton Anthology of American Literature Vol. E. 7th Edition. Ed. Nina Baym, Jerome Klinkowitz, Patricia B. Wallace, et al. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007. 2407-2409

#reading#writing#essay#poetry#dissent#protest#confession#robert lowell#confessional poetry#technology#civil rights#social media#machines#organic#academics#essay writing#literary criticism#civil war#desegregation#social justice#progress#american literature

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr: "Would Saul be able to get Light Yagami acquitted for the murders?"

Me: I can't participate in this conversation, lest Tumblr find out how much I hate "Death Note"

#I really tried I watched this show once all the way through and even tried to give it a second chance.#The pilot is great but it's all down hill from there.#Y'all are insane saying it has good pacing. Every twist was either not set up at all or set up ad-nauseum.#L's “genius” mindbattle with Kira is just script-omniscience.#I get what they were trying to do/say but none of the characters act like real people would in this situation.#It wants to be about characters perpetuating acts of evil in the name of the greater good but there is 0 progression#I don't live in Japan but would a police state really spend this much energy hunting down a vigilante who is mostly going after petty crimi#Light doesn't even agonize the first time he kills an innocent person to cover his tracks not even an interesting “psychopath”#Misa is a stupid bitch. Light is about as morally gray as a newspaper. Ryuk is the only likeable one.#It's like if they took the tedium of the Walt/Hank cat-n-mouse game and made that the ONLY THING going on in the plot.#Not to mention the fandom is obnoxious. I bring this stuff up and I get back “You've been ratioed”#Gee thanks now that I know the overwhelmingly popular thing is overwhelmingly popular I guess I have to like it.#It's not like there's room for a dissenting opinion or something of people who took the thing in chewed it digested it and decided they did

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe if he didn't want to be bothered at dinner, he shouldn't have gone out to dinner. Does he not agree with such logic?

#brett kavanaugh#politics#us politics#progressive#america#united states#american politics#news#feminism#supreme court#roe vs wade#scotus#the supreme court#abortions#fuck scotus#dissent

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

the worst part about being gay is hands down the linguistics, I’m so fucking tired of having to read faux-inclusive terminology that just winds up contradicting what the poster was trying to say and making their meaning harder to understand. If you mean men just write men, saying that “AFABs have a reason to be wary of masculine-identifying people” just garbles everything and lumps in butches + transmascs who SHOULD be included in AFABs. and replacing AFAB with “femmes” like I see a lot of folks do functionally doesn’t work - I’m masculine identifying and still AFAB and have all the lived experience of being a woman, so where do people like me fit into that conversation, ykwim? like fuck dude I’m not lying when I say I think our biggest mistake as homos was reducing gender to Feminine = Good and Victimized and Masculine = Bad and Evil

#Faux progressive language doesn’t mask those core beliefs as well as people think it does#and I lowkey blame the lgbtq culture here on tumblr for our dissent into this bs

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Allyship Is a War Mentality | The Cruelty Of Wokeism | Woke Up

It's important to note that while these criticisms exist, there is also substantial support for the goals of wokeism. Proponents argue that it has raised awareness about systemic inequalities and sparked important discussions about how to address them. They see it as a necessary response to ongoing injustices and believe it can lead to positive social change.

#woke up#woke ideology#we woke up#allyship is a war mentality#cruelty of wokeism#social justice#toxic tactics#corrosive influence#psychological violence#free expression#intellectual diversity#war mentality#genuine progress#critical thinking#intellectual growth#dissenting voices#individual liberties#liberal thinking#ideological purity#societal discourse#self censorship#positive change#woke warriors#cancel culture#Youtube

0 notes

Note

A poem to cure your leftness/socialism/communism/marxism/queerness/lesbianism/progressiveness/environmental activism/moralism

In shadows deep, where reason wanes,

A woke brigade, its grip remains.

Proclaiming truths with zealous might,

Yet blind to nuance, shunning light.

In echo chambers, minds confined,

Dissent dismissed, no space to find.

A dogma rigid, thoughts constrained,

Individuality, it's disdained.

Justice sought with biased eyes,

No room for dialogue, compromise.

Words deemed weapons, silence coerced,

Free expression quenched, diversity cursed.

Oh, woke crusaders, self-appointed,

Your righteousness leaves minds disjointed.

In pursuit of progress, heed this call,

True wisdom listens, lest we all fall.

NOOOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

YOU HAVEN'T SEEN THE LAST OF ME, FIRSTNAME BUNCHOFNUMBERS!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

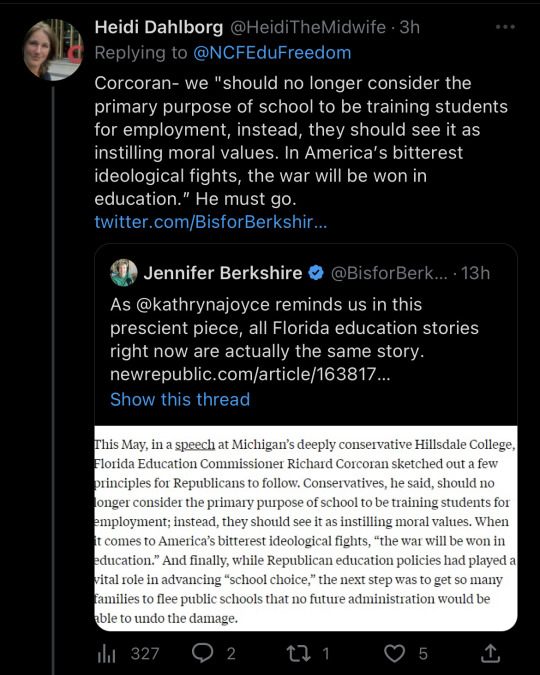

this is happening at my college right now. i’m in my third year here and everyone i know is like, haha, im in danger.

one of my professors earlier today had the perfect word to describe the feeling of it: traumatizing

what they’re doing seems almost illegal, like.. considering desantis brought in the majority of the trustees in one sweep, we didnt even have a chance to dissent their new supermajority firing president okker with no cause. or if it isn’t, it should be illegal, there’s literally no checks and balances happening here. no democracy involved. genuine fascism at work, it’s actually absurd. extremely fucking filthy and despicable political ploy.

yesterday wrt the board of trustees meeting, a student commented, “The fact they are playing [the college president] like she's a game and she is sitting at that table CRYING is something that shakes me.”

this is who they replaced our president with

they don’t care about education or the students at all. they don’t care. we’re chess pieces to them.

read more:

please help us defend ourselves, not just for NCF but for educational freedom in academic institutions in general. donate, spread the word, etc. here’s the site

this son of a bitch is definitely going to run for president in 2024. pay attention to what’s happening on the ground here. it’s very bleak.

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tyranny Of Progressivism And The Cult Of Woke

Since it was first published in 1859, John Stuart Mill’s essay ‘On Liberty’ has become a standard reference for campaigners against censorship, authoritarianism, suppression of dissent and the right to freely express opinions and question dogma (free speech,) and other political or religious constraints on freedom whether political, social, religious, academic or interpersonal. A century and a…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

When it comes to abortion rights, the Democrats need to lean into the politics of fear.

They face a base that feels betrayed and a set of wealthy, moderate voters in purple states who may not realize that their own rights are also on the line. Democrats need both of these groups to stave off defeat in the fall, and fear can drive them to the polls. What should the Democrats tell them to be afraid of? A national abortion ban.

America after the fall of Roe v. Wade might feel like we’re living in the worst-case scenario, but anyone who values reproductive freedom has reason to panic about what could happen if Republicans take back power in Washington. G.O.P. Congress members have already introduced bills that would criminalize abortion in various ways. They are only more emboldened now.

To meet the urgency of the moment and save their razor-thin and often nonexistent hold on the Senate, Democrats must talk about that future, giving voters across the country, in every state, a reason to vote. Lives are on the line. At the same time, Democratic leaders have to understand that the politics of fear can run both ways.

The party needs to scare voters and show that they, too, are scared: scared of the voters themselves. Democratic politicians watched Republicans roll back abortion rights for decades — and when Roe fell, they had no plan. Now, they need to demonstrate that they are willing to put themselves at the mercy of those they failed — making specific promises and letting the voters know that if they fail again, it will be more than a fund-raising opportunity. It will be a reckoning.

I am honestly unsure if it matters what those action items are; I do know Democrats will have to throw out any concern for the appearance of moderation. Right now, all the ideas about bridging the gap to abortion access sound extreme. But so did the tax pledge at one point. So did overturning Roe v. Wade.

Take allowing abortions on federal land. Biden could declare the policy so. Candidates would only have to pledge to support it. Yes, the policy would invoke an avalanche of untested legal theories and complicated jurisdictional questions. But Democrats who want to save the lives of those in need of an abortion can’t fall back on “it’s complicated” as an excuse to not even try.

If you want something less complicated — something that would also help roll out abortions on federal lands — make a pledge not to vote for any appropriation bill that carries the Hyde Amendment, which bans federal funding for most abortions. On its own, abolishing the Hyde Amendment would not greatly expand access outside states where abortion is legal. But combined with abortion access on federal property, the government could act even more directly to help those seeking abortion care. Stonewalling Hyde-burdened budgets could lead to a government shutdown, but if you think that ruins a party’s reputation forever, well, you are probably a current Democratic office holder.

Embracing a politics of fear on reproductive rights unites two of the constituencies the Democrats need to edge out the G.O.P. in key narrow races (Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Georgia). First, hammering home the danger of a national ban may sufficiently alarm moderate voters in the suburbs, convincing them to abandon Republicans. Second, addressing the widespread sense of betrayal among progressive voters will help keep them activated. The threat of a national abortion ban is also a national message. Democrats can make it clear that the party can’t risk a single loss, no matter how lopsided the polls are. And then there is the simple truth underpinning this entire strategy: Protecting abortion rights is popular.

#abortion rights#reproductive rights#scotus#midterms#democrats#hyde amendment#progressives#moderates#full piece should be available thru gift link#what do we think of the suggested approach? vital? unrealistic? urgently necessary? not far enough?#not sure anyone will even see this but if you do:#concurring and dissenting views are welcome! please keep it civil and explanatory

0 notes

Note

A poem to cure your leftness/socialism/communism/marxism/queerness/lesbianism/progressiveness/environmentalactivism/moralism/anarchism

In shadows deep, where reason wanes, A woke brigade, its grip remains. Proclaiming truths with zealous might, Yet blind to nuance, shunning light.

In echo chambers, minds confined, Dissent dismissed, no space to find. A dogma rigid, thoughts constrained, Individuality, it's disdained.

Justice sought with biased eyes, No room for dialogue, compromise. Words deemed weapons, silence coerced, Free expression quenched, diversity Cursed.

Oh Woke Crusaders, self-appointed. Your righteousness leaves minds disjointed. In Persuit of progress heed this call, True wisdom listens, lest we all fall.

hey bud you accidentally sent this off anon. seek help

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was rethinking the bookshop meta I wrote a while ago and realized I was not thinking big enough.

The bookshop has always been Aziraphale's version of Crowley's plants (his trauma reenactment), but also, absolutely everything Aziraphale does in Season 2 is a re-creation of Heaven's role. Crowley's behavior also encompasses everything, not just his plants.

I've seen it suggested that centering Aziraphale and Crowley's trauma histories is reducing their characters to behaving like just reactive victims instead of survivors with agency. Or worse, it's "excusing bad behavior." I don't agree with either of these, because I feel that part of Good Omens is about how large, powerful systems affect individuals, and so the context of every character's decisions matters a lot to the overall themes of the story. Everyone starts out working within a system they believe to reflect reality and then has to learn how to break free of it. You cannot really illustrate that without having the characters start out being genuinely trapped with different ways of coping with their reality.

This is an attempt at a pretty big-picture meta. Although it isn't a plot prediction, it's how I think some of the series' themes are going to progress. It starts out perhaps a little grim, but in the long run, it's how Aziraphale's character growth and relationship with Crowley can simultaneously be massive for them as individuals, a crucial part of the overarching narrative message of the series, and symbolic of a change in all of Heaven and Hell, all while allowing the themes to continue to prioritize human free will.

In short, it's about Aziraphale's problems, but it's also meant to be an Aziraphale love post.

All of the below exists in tandem with Good Omens as a comedy of errors. Just because there are heavy ideas does not mean they will not also be funny. Look back on how much of Season 2 seemed silly until we started to pick it apart! One of the amazing things about Good Omens is how it manages to do both silly and serious at once! (I feel like that's maybe a little Terry Pratchett DNA showing through. "Laughter can get through the keyhole while seriousness is still hammering on the door," as Terry himself said.)

Aziraphale has really embraced his connection to Crowley in Season 2, and he has also become considerably more assertive toward Heaven and Hell. These are both major growth points compared to the beginning of Season 1.

However, again, we have the concept of growing pains...Aziraphale is starting to re-create Heaven's role in his relationship with Crowley and humanity. It's really obvious with the Gabriel argument and the I Was Wrong Dance, but I think we see it all over the place: he seems to feel any serious dissent is a betrayal. He also seems to assume there's a dominance hierarchy and he, of course, is on top. Now that he's decided to take control of his own future, then surely that does mean he's the one in control, right?

With all that said, he still seems to have trouble being direct about the feelings that make him most vulnerable. He manipulates people and engineers situations in which he can try to get his emotional needs met rather than saying things outright (case in point: the Ball).

Like I pointed out in the bookshop meta: subconsciously, he's playing the role of God, modified with what God would be if She were everything he wants Her to be. He's generous, almost infinitely sweet, always does what's best for people...or, at least, what he believes is best for people. During the Ball, Aziraphale influences the people around him to be comfortable and happy even when they're not supposed to be, and he limits their ability to talk about things he thinks are too rude or improper for happy, formal occasions.

Doesn't this pattern sort of make sense for an angel who's just discovering free will? Like, at the end of Season 1, he made an enormous choice to stand against Heaven and realized he could survive it. Now he's gone a bit overboard with exerting his own will. Unfortunately, while he's learned to question upper management, he's still operating on a fundamental framework of the universe where there have to be two sides and there has to be a hierarchy. Also, since Aziraphale is on the Good side, he of course has to gear his desires into what's Good rather than just what he wants, so he sometimes thinks he's doing things for others when really he's doing things for himself. (For example, matchmaking Maggie and Nina started out as something he wanted to use to lie to Heaven, but by the time he was commenting "Maggie and Nina are counting on me," he seemed sincere, like he had genuinely convinced himself this was for them and not for himself.)

Aziraphale knows Heaven interferes in human affairs, ostensibly on God's behalf. He thinks She should be intervening in ways that are beneficial. What I believe the narrative wants him to learn is that God and Heaven shouldn't be manipulating people at all, not even for Good, and in fact there is no real meaningful hierarchy.

Anyway, a top-down, totally unquestioned hierarchy is the primary social relationship Aziraphale has known, and it's certainly been the dominant one for most of his existence: you're either the boss or the underling, and if someone seriously questions you, they don't have faith in you - they don't respect you.

No, his relationship with Crowley has not always been like that, but they've been creating their relationship from whole cloth, so how would he know it shouldn't become that way, now that it's "real" and out in the open?

No, human relationships aren't like that, but Aziraphale clearly does not see himself or Crowley as human. As the relationship approached something that seemed like it must be "legitimate," Aziraphale would naturally look for a framework to fit it to. And again, the only one he has is the shape of "intimacy," or what passes for it, in Heaven. What has "trust" always meant in all his "legitimate" relationships? It has always meant unquestioning obedience, of course. What have the warm fuzzies felt like in Heaven? Well, praise from the angels above him is nice, so that must be it, right?

Aziraphale even describes being in love as "what humans do," separating out that relationship style. Someday, I think he'll realize he favors the shape of love on Earth, something that's more inherently equal, more give-and-take. Look at how he idealizes it from afar at the Ball. But I think that, like Crowley before Nina pointed it out, Aziraphale maybe hasn't 100% grokked that it can and in fact should work that way for him and Crowley, too. Just like people can desperately want to dance without knowing how to dance, or can desperately want to speak a language without knowing the language, Aziraphale does not instinctively know how to have the kind of relationship where he can be truly vulnerable and handle Crowley's vulnerability as well.

Aziraphale is downright obsessed with French, known as the "language of love." He's trying to learn it the Earthly way. He's not very good at it, but he wants to be.

This pattern is still present during the Final Fifteen even if we assume Aziraphale is asking Crowley to become an angel again out of fear (and I find it very hard to believe that fear doesn't factor in at all). He's still building his interactions off of that Heaven-like framework: he asks Crowley to trust him blindly, he tries to assume a leadership role with a plan Crowley never agreed to and couldn't follow anyway, and he tries very hard not to leave room for an ounce of doubt. He also suggests making Crowley his second-in-command and obviously does not register that this could possibly be offensive. Again, I think this is because for Aziraphale, there has always been a hierarchy in Heaven, it's started to transfer to his relationship with Crowley, and breaking out of that assumption about relationships is going to take more processing than a single argument can do.

As I mentioned in another post, I don't believe Aziraphale had a real choice about whether he accepted the Supreme Archangel position. I think he could sense that he was not getting out of it and chose to look on the bright side, to see it as an opportunity. And instead of looking realistically at how that would feel to Crowley, he tried to sweep Crowley up to Heaven with him using toxic positivity, appeals to morality, and appeals to their relationship itself. Again, mimicking what Heaven has done to him.

To me, "they're not talking" is a big clue that Aziraphale's approach with Crowley is going to be the mistake the narrative really wants him to face. "Not talking" has, thus far, been presented as the central conflict of Season 3! After losing the structure and feedback Heaven gave him, Aziraphale started creating Heaven-like patterns in his relationship with Crowley, and breaking out of those patterns is what he needs to do. Discovering first-hand that Heaven's entire modus operandi is bad no matter who's in charge is how he can do it.

Look, either you're sympathetic to Aziraphale's control issues or you're not. Personally, I am. He's trying so, so hard to be good. I think trying to figure yourself out (which Aziraphale is clearly doing) is hard enough, and when you start balancing what you want for yourself, what you think are your responsibilities, and what other people are actively asking of you, you're bound to fall into the patterns that have been enforced for your whole life or for millions of years, whichever came first.

It is very easy to assume that people should Just Be Better, but it's not actually that simple to be a thinking, feeling person. My anxiety tends to move in a very inward direction and Aziraphale's moves outward. But I'd imagine the desperation and exhaustion are the same.

Unlike Nina, Aziraphale became a rebound mess. I don't think it occurred to either him or to Crowley that there could be any soul-searching, anything but carrying on with the new normal after their stalemate with Heaven and Hell.

Now, instead of getting rejected by Heaven and surviving it, Aziraphale needs to be the one to reject Heaven. It needs to be a choice. And that choice is going to come from realizing that Heaven isn't just poorly managed but also represents a bad framework for all relationships.

How could this happen? Good question. We're obviously not supposed to know yet, although I think picking at existing themes within the narrative could possibly give us hints.

It's possible Aziraphale's character development trajectory will be akin to Adam Young's in Season 1. Please see this stellar post by eidetictelekinetic for more thoughts about it, but basically, in Season 1, Adam saw that the world was not what he wanted it to be and decided his vision was better; as he ascended to power, he took complete control over all his friends and then soon realized that's not what he wants because there's no point in trying to have relationships with people who can't choose you. It's that realization that leads Adam to conclude he doesn't want to take over the world and to reject the role he's expected to play as the Antichrist. Maybe Aziraphale's trip to Heaven is an attempt at a control move during which he'll realize he's defeating his own point.

Aziraphale clearly wants to be chosen. From the very beginning, he's wanted to be special and cared for - just like Crowley has.

Incidentally, I think Aziraphale and Crowley are going to represent pieces of the bigger picture here, and this - first imitating and then rejecting Heaven's relationship style - can both symbolize Heaven's transformation and directly start it (probably in an amusing, somewhat indirect way, like when he handed off the flaming sword to Adam).

If I'm right - which I may very well not be - I think this would all be so, SO cool. Like, "An angel who is subconsciously trying to be a better God" is a concept with so much potential for both tender kindness and incredible darkness. Add to that the comedy-of-errors aspect of "...but even deeper down, he'd much rather just be super gay on Earth" and you have, in my opinion, a perfect character.

I think this could work for Crowley as well. It's obvious that in the Good Omens universe, at least so far, Hell is all about detesting humans and punishing them; Satan seems to genuinely hate humans (unlike in some of NG's other works). Our perspective on this could change, but it potentially puts Crowley in a complementary position to Aziraphale, as a demon who is trying to be "better" than Satan. But this isn't about being "morally better." It's about things having a point. Crowley's exploits usually have a point: they test people. And you can pass his tests! He sincerely likes making trouble, but Crowley doesn't live to punish.

But, once again, the above paragraph would describe a transient phase for this infinitely charming character. Because, again, I think the point will be that in the end, Crowley's deeper-down desire, moreso than testing Creation, is watching it grow with a glass of wine in hand.

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

Orter Mádl x Reader

The Magic Realm is currently in turmoil, plagued by a wave of chaos caused by a perpetrator who has been indiscriminately stealing magic from civilians. Orter Mádl himself fell victim to this individual, losing his magical ability during a confrontation. You, alongside the rest of the Divine Visionaries, worked tenaciously to track down the perpetrator, but progress remained frustratingly slow.

Despite the Bureau's attempts to keep the matter under wraps, news of Orter's loss of magic spread like wildfire through the town. Frustration and unrest boiled over, prompting the civilians to point fingers at the easiest target: Orter. They blamed him for failing to catch the culprit and began protesting outside the Bureau's building.

"How can a magicless person serve as a wand of the Gods?!" a protestor exclaimed. “He must be dismissed from his position as a Divine Visionary posthaste!"

Another voice chimed in, “He couldn’t even catch the culprit, and now he’s lost his magic. He’s clearly unfit to remain a servant of the divine!”

“They’re quite noisy today,” Kaldo sighed, observing the commotion below from inside the building.

Frustrated by the incessant clamor, you made a bold move, swinging open the double doors and striding onto the balcony to confront the crowd directly.

"Enough!” you declared, your gaze piercing through the crowd. “What I'm about to say is not an official statement from the Bureau, but a personal statement from myself as the Judgement Cane."

Your voice carried authority as you continued, “I will not tolerate anyone continuing to speak ill of the Desert Cane. Whether he remains a Divine Visionary is not for you to dictate, nor is it your place to question. Need I remind you all of your stations?”

“But he lost his magic! What good is a Divine Visionary without magic?” a dissenting voice interjected.

Another voice challenged, “But you're the Judgement Cane! How can you accept a lackmagic working alongside you?"

You were now livid, practically screaming at the crowd. "So what if he lost his magical abilities? Since the day he became a Divine Visionary, he has worked tirelessly for the sake of each and every one of you. Up until now, you ungrateful swines have enjoyed the fruits of his labor, yet here you are, ready to turn your back on him the moment he lost his magical ability. Have you no bounds to your foolishness?!”

The crowd fell silent, their gazes shifting uncomfortably under the weight of your accusations. You continued, your voice sharp and resolute. "Someone who has devoted himself to creating a world where order matters so everyone can live in peace...should never be subjected to such treatment. I will never allow it."

It was quite ironic. As the Judgement Cane, entrusted with delivering rational verdicts, here you were, allowing your emotions to guide your actions.

"Any further insults or harassment, and there will be consequences." You issued the threat with a final glare at the crowd before retreating back into the building.

Inside, Orter met you with a stern expression on his face.

“That was irrational of you. You will face extreme repercussions for this,” he remarked.

“Irrational? Hardly.” You countered. “Defending my fiancé from slander was the only logical course of action.”

Although he didn’t show it, you could sense how deeply the situation affected him. After all, in this realm, magic is everything, and those without it are often deemed forsaken by the Gods. Any ordinary person would have already been executed.

A ghost of a smile tugged at the corners of Orter's lips. He knew he should have been angry at your impulsive actions, but he couldn't bring himself to be.

Your unwavering devotion meant more to him than he could express, despite his demeanor.

Inspired by chapter 81 of the manga. Lemon rose several places in my personal ranking after that chapter. Really moved me to tears with her speech 🤌

#orter madl x reader#orter x reader#orter madl x y/n#mashle orter x reader#orter madl x you#mádl orter x reader#orter mádl x reader#orter x y/n#orter x you#mashle#mashle orter#orter madl#orter mádl

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Many of the women in Heterodoxy moved in corresponding circles and maintained similar beliefs. They were “veterans of social reform efforts,” writes Scutts in Hotbed, and they belonged to “leagues, associations, societies and organizations of all stripes.” A large number were public figures—influential lawyers, journalists, playwrights or physicians, some of whom were the only women in their fields—and often had their names in the papers for the work they were performing. Many members were also involved in a wide variety of women’s rights issues, from promoting the use of birth control to advocating for immigrant mothers.

Heterodoxy met every other Saturday to discuss such issues and see how members might collaborate and cultivate networks of reform. Gatherings were considered a safe space for women to talk, exchange ideas and take action.”

In the early 20th century, New York City’s Greenwich Village earned a reputation as America’s bohemia, a neighborhood where everyone from artists and poets to activists and organizers came to pursue their dreams.

“In the Village, it was so easy to bump into great minds, to go from one restaurant to another, to a meeting house, to work for a meeting or to a gallery,” says Joanna Scutts, author of Hotbed: Bohemian Greenwich Village and the Secret Club That Sparked Modern Feminism. Here was a community where rents were still affordable, creative individuality thrived, urban diversity and radical experiments were the norm, and bohemian dissenters could come and go as they pleased.

Such a neighborhood was the ideal breeding ground for Heterodoxy, a secret society that paved the way for modern feminism. The female debating club’s name referred to the many unorthodox women among its members. These individuals “questioned forms of orthodoxy in culture, in politics, in philosophy—and in sexuality,” noted ThoughtCo. in 2017.

Born as part of the initial wave of modern feminism that emerged during the 19th and early 20th centuries with suffrage at its center, the radical ideologies debated at Heterodoxy gatherings extended well beyond the scope of a women’s right to vote. In fact, Heterodoxy had only one requirement for membership: that a woman “not be orthodox in her opinion.”

“The Heterodoxy club and the work that it did was very much interconnected with what was going on in the neighborhood,” says Andrew Berman, executive director of Village Preservation, a nonprofit dedicated to documenting and preserving the distinct heritage of Greenwich Village. “With the suffrage movement already beginning to crest, women had started considering how they could free themselves from the generations and generations of structures that had been placed upon them.”

Unitarian minister Marie Jenney Howe founded Heterodoxy in 1912, two years after she and her husband, progressive reformer Frederic C. Howe, moved to the Village. “Howe was already in her 40s,” says Scutts, “and just got to know people through her husband’s professional connections, and during meetings and networks where progressive groups were very active at the time.”

Howe’s mindset on feminism was clear: “We intend simply to be ourselves,” she once said, “not just our little female selves, but our whole big human selves.”

Many of the women in Heterodoxy moved in corresponding circles and maintained similar beliefs. They were “veterans of social reform efforts,” writes Scutts in Hotbed, and they belonged to “leagues, associations, societies and organizations of all stripes.” A large number were public figures—influential lawyers, journalists, playwrights or physicians, some of whom were the only women in their fields—and often had their names in the papers for the work they were performing. Many members were also involved in a wide variety of women’s rights issues, from promoting the use of birth control to advocating for immigrant mothers.

Heterodoxy met every other Saturday to discuss such issues and see how members might collaborate and cultivate networks of reform. Gatherings were considered a safe space for women to talk, exchange ideas and take action. Jessica Campbell, a visual artist whose exhibition on Heterodoxy is currently on display at Philadelphia’s Fabric Workshop and Museum, says, “Their meetings were taking place without any kind of recording or public record. It was this privacy that allowed the women to speak freely.”

Scutts adds, “The freedom to disagree was very important to them.”

With 25 charter members, Heterodoxy included individuals of diverse backgrounds, including lesbian and bisexual women, labor radicals and socialites, and artists and nurses. Meetings were often held in the basement of Polly’s, a MacDougal Street hangout established by anarchist Polly Holladay. Here, at what Berman calls a “sort of nexus for progressive, artistic, intellectual and political thought,” the women would gather at wooden tables to discuss issues like fair employment and fair wages, reproductive rights, and the antiwar movement. The meetings often went on for hours, with each typically revolving around a specific subject determined in advance.

Reflecting on these get-togethers later in life, memoirist Mabel Dodge Luhan described them as gatherings of “fine, daring, rather joyous and independent women, … women who did things and did them openly.”

Occasionally, Heterodoxy hosted guest speakers, like modern birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger, who later became president of the International Planned Parenthood Federation, and anarchist Emma Goldman, known for championing everything from free love to the right of labor to organize.

While the topics discussed at each meeting remained confidential, many of Heterodoxy’s members were quite open about their involvement with the club. “Before I’d even heard of Heterodoxy,” says Scutts, “I had been working in the New-York Historical Society, researching for an [exhibition on] how radical politics had influenced a branch of the suffrage movement. That’s when I began noticing many of the same women’s names in overlapping causes. I then realized that they were all associated with this particular club.”

These women included labor lawyer, suffragist, socialist and journalist Crystal Eastman, who in 1920 co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union to defend the rights of all people nationwide, and playwright Susan Glaspell, a key player in the development of modern American theater.

Other notable alumni were feminist icon Charlotte Perkins Gilman, whose 1892 short story, “The Yellow Wallpaper,” illustrates the mental and physical struggles associated with postpartum depression, and feminist psychoanalyst Beatrice M. Hinkle, the first woman physician in the United States to hold a public health position. Lou Rogers, the suffrage cartoonist whose work was used as a basis for the design of Wonder Woman, was a member of Heterodoxy, as was Jewish socialist activist Rose Pastor Stokes.

Grace Nail Johnson, an advocate for civil rights and an influential figure in the Harlem Renaissance, was Heterodoxy’s only Black member. Howe “had personally written to and invited her,” says Scutts, “as sort of a representation of her race. It’s an unusual case, because racial integration was quite uncommon at the time.”

While exceptions did exist, the majority of Heterodoxy’s members were middle class or wealthy, and the bulk of them had obtained undergraduate degrees—still very much a rarity for women in the early 20th century. Some even held graduate degrees in fields like medicine, law and the social sciences. These were women with the leisure time to participate in political causes, says Scutts, and who could afford to take risks, both literally and figuratively. But while political activism and the ability to discuss topics overtly were both part of Heterodoxy’s overall ethos, most of its members were decidedly left-leaning, and almost all were radical in their ideologies. “Even if the meetings promoted an openness to disagree,” says Scutts, “it wasn’t like these were women from across the political spectrum.”

Rather, they were women who inspired and spurred each other on. For example, about one-third of the club’s members were divorced—a process that was still “incredibly difficult, expensive and even scandalous” at the time, says Scutts. The club acted as somewhat of a support network for them, “just by the virtue of having people around you that are saying, ‘I’ve gone through the process. You can, too, and survive.’”

According to Campbell, Heterodoxy’s new inductees were often asked to share a story about their upbringing with the club’s other members. This approach “helped to break down barriers that might otherwise be there due to their ranging political views and professional allegiances,” the artist says.

The Heterodoxy club usually went on hiatus during the summer months, when members relocated to places like Provincetown, Massachusetts, a seasonal outpost for Greenwich Village residents. As the years progressed, meetings eventually moved to Tuesdays, and the club began changing shape, becoming less radical in tandem with the Village’s own shifting energy. Women secured the right to vote with the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, displacing the momentum that fueled the suffrage movement; around this same time, the Red Scare saw the arrests and deportations of unionists and immigrants. Rent prices in the neighborhood also increased dramatically, driving out the Village’s bohemian spirit. As the club’s core members continued aging, Heterodoxy became more about continuing friendships than debating radical ideologies.

“These women were not all young when they started to meet,” says Scutts in the “Lost Ladies of Lit” podcast. “You know, it’s 20, 30 years later, and so they stayed in touch, but they never really found the second generation or third generation to keep it going in a new form.”

By the early 1940s, the biweekly meetings of Heterodoxy were no more. Still, the club’s legacy lives on, even beyond the scope of modern feminism.

“These days, it’s so easy to dehumanize people when you’re only hearing one facet of their belief system,” says Campbell. “But the ability to change your mind and debate freely like the women of Heterodoxy, without any public record? It’s an interesting model for rethinking the way we talk about problems and interact with other people today.”

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

For a time, they would make impressive progress critiquing Israeli state mythology, exposing the state’s overtly racist policies towards Black and Arab Jews, the injustices of the occupation, and he horrors of the 1948 ethnic cleansing. But the ultimate conclusion that such critiques should have brought about—that the Zionist project was illegitimate an unnecessary—was a bridge too far for almost everyone in the post-Zionist camp. Not only was it too far, it remained the very foundation on which they staked their identities as Israelis. Many of them looked on their own critiques with dread, and it did not take much to drive many of them back into the arms of Zionism, begging for forgiveness.

My latest article, "What happens to an Israel without dissent?", is out now on my Substack.

You can read it here.

92 notes

·

View notes