#red book of hergest

Text

My heart aches to find fellow bloggers who practice welsh folk magic or who love the mabinogion. Please interact with this if you are either or both!

#white book of rhydderch#red book of hergest#gwenhwyfar#blodeuwedd#welsh mythology#mabinogion#british folklore#celtic#welsh#wales#welsh witchcraft#witchcraft

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay I'm almost done with Fellowship, here's an incomplete list of shit I noticed and thought was buck fucking wild on my first ever read-thru: medieval edition.

In literally the second line of the book, Tolkien implies that Bilbo Baggins wrote a story which was preserved alongside the in-universe version of the Mabinogion (aka the best-known collection of Welsh myths; I promise this is batshit). This is because The Hobbit has been preserved, in Tolkien's AU version of our world, in a "selection of the Red Book of Westmarch" (Prologue, Concerning Hobbits). If you're a medievalist and you see something called "The Red Book of" or "The Black Book of" etc it's a Thing. In this case, a cheeky reference to the Red Book of Hergest (Llyfr Coch Hergest). There are a few Red Books, but only Hergest has stories).

not a medieval thing but i did not expect one common theory among hobbits for the death of Frodo's parents to be A RUMORED MURDER-SUICIDE.

At the beginning of the book a few hobbits report seeing a moving elm tree up on the moors, heading west (thru or past the Shire). I mentioned this in another post, but another rule: if you see an elm tree, that's a Girl Tree. In Norse creation myth, the first people were carved from driftwood by the gods. Their names were Askr (Ash, as in the tree), the first man, and Embla (debated, but likely elm tree), the first woman. A lot of ppl have I think guessed that that was an ent-wife, but like. Literally that was a GIRL. TREE.

Medieval thing: I used to read the runes on the covers of The Hobbit and LOTR for fun when I worked in a bookshop. There's a mix of Old Norse (viking) and Old English runes in use, but all the ones I've noticed so far are real and readable if you know runes.

Tom Bombadil makes perfect sense if you once spent months of your life researching the early medieval art of galdor, which was the use of poems or songs to do a form of word-magic, often incorporating gibberish. If you think maybe Tolkien did not base the entirety of Fellowship so far around learning and using galdor and thus the power of words and stories, that is fine I cannot force you. He did personally translate "galdor" in Beowulf as "spell" (spell, amusingly, used to mean "story"). And also he named an elf Galdor. Like he very much did name an elf Galdor.

Tom Bombadil in fact does galdor from the moment we meet him. He arrives and fights the evil galdor (song) of the willow tree ("old gray willow-man, he's a mighty singer"), which is singing the hobbits to sleep and possibly eating them, with a galdor (song) of his own. Then he wanders off still singing, incorporating gibberish. I think it was at this point that I started clawing my face.

THEN Tom Bombadil makes perfect sense if you've read the description of the scop's songs in Beowulf (Beowulf again, but hey, Tolkien did famously a. translate it b. write a fanfiction about it called Sellic Spell where he gave Beowulf an arguably homoerotic Best Friend). The scop (pronounched shop) is a poet who sings about deeds on earth, but also by profession must know how to sing the song or tell the story of how the cosmos itself came to be. The wise-singer who knows the deep lore of the early universe is a standard trope in Old English literature, not just Beowulf! Anyway Tom Bombadil takes everyone home and tells them THE ENTIRE STORY OF ALL THE AGES OF THE EARTH BACKWARDS UNTIL JUST BEFORE THE MOMENT OF CREATION, THE BIG BANG ITSELF and then Frodo Baggins falls asleep.

Tom Bombadil knows about plate tectonics

This is sort of a lie, Tom Bombadil describes the oceans of old being in a different place, which works as a standard visual of Old English creation, which being Christian followed vaguely Genesis lines, and vaguely Christian Genesis involves a lot of water. TOLKIEN knew about plate tectonics though.

Actually I just checked whether Tolkien knew about plate tectonics because I know the advent of plate tectonics theory took forever bc people HATED it and Alfred Wegener suffered for like 50 years. So! actually while Tolkien was writing LOTR, the scientific community was literally still not sure plate tectonics existed. Tom Bombadil knew tho.

Remember that next time you (a geologist) are forced to look at the Middle Earth map.

I'm not even done with Tom Bombadil but I'm stopping here tonight. Plate tectonics got me. There's a great early (but almost high!) medieval treatise on cosmology and also volcanoes and i wonder if tolkien read it. oh my god. i'm going to bed.

edit: part II

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! So let’s say one of your listeners’ whole knowledge about Arthurian legends is that there was King Arthur, knights, Round Table and Grail. And they were like: fine, doesn’t matter, I will certainly enjoy Camlann anyway. And let’s say that after two episodes they did realise that it matter to them and they do have a deep personal need to actually know something more. What would you recommend them to read to learn more (or like anything) about Arthurian legends?

HI!!!!! Well, in this hypothetical situation, first of all I would say thank you very much to this listener for caring enough to ask.

Second, my big recommendations would be Le Morte d'Arthur by Thomas Mallory (maybe the most famous Norman version of the stories) and The Mabinogion, translated by Sioned Davies (the most Welsh version of the stories!). In particular I'd recommend this listener read up on Culhwch ac Olwen and Peredur, which have been referenced so far. I'd also strongly recommend this person read Gawain and the Green Knight (I like Simon Armitage's version, which is also available as an audiobook).

If this person wanted to go further, they could also read translations of Chretien de Troyes' chivalric romances, Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Brittonum, and medieval Welsh poetry found in the Red Book of Hergest and the Black Book of Carmarthen.

I will say Camlann is (very much on purpose) a chaotic mish-mash of Arthurian legends and British folklore. In some places we run very close to 'the canon', and in other places we throw it away completely. Sometimes I'll be referencing pretty obscure bits of Arthurian canon, sometimes we'll be bringing up fairly commonly accepted stuff.

I hope this hypothetical listener has fun!

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

DIAS Black Friday Sale

Once a year, the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies (DIAS), offers a sale for Black Friday -- DIAS is one of the major publishers for Celtic Studies, many of the best studies of medieval Irish material have come through there.

Some books that I recommend, personally:

Fergus Kelly, A Guide to Early Irish Law (26.25 Euro, normally 35) (THE introduction to law in medieval Ireland)

"", Early Irish Farming (26.25 Euro, normally 35) (Everything you wanted to know about day to day life in medieval Ireland but were afraid to ask. Literally. Everything.)

Medieval Irish Prose

Fergus Kelly, Audacht Morainn (18.75 Euro, normally 25)

Are you planning on becoming a medieval Irish king? Do you want to know what you should do to involve the total destruction of the natural order? Then this is the text for you! Now with English translation!

In all seriousness, this text is used a LOT with regards to studies of ideal kingship in medieval Ireland.

Cecile O'Rahilly, The Táin from the Book of Leinster (26.25 Euro, usually 35)

I'll be real with you, lads: I hate Cú Chulainn. I hate him. I hate his smug, misogynistic face. His creepy multi-pupiled eyes. The shitty way he treats Emer. The way that his presence is like this black hole in the study of medieval Irish literature that means that the Ulster Cycle can get a prestigious yearly conference held in its honor while the other cycles are left with either crumbs or outright dismissal. I think the Táin is boring and episodic as a piece of lit and I've never found anything overly redeeming about it over any other piece of medieval Irish literature, especially since imo other pieces of literature do women (and homoeroticism) much better and get much less praise for it.

...that being said. It's important. It IS iconic, both as a piece of medieval Irish literature and, in general, to Irish literature. Its status as The Irish Iliad means that, if you want to study medieval Irish stuff...you have to read the Táin. And this is a version of the Táin that you might not have gotten, translated and edited by a master of Old Irish, with commentary.

"", Táin Bó Cúailnge: recension I (10 Euro, normally 35)

See above.

Early Irish History and Genealogy

T.F. O'Rahilly, Early Irish History and Genealogy (30 Euro, normally 40)

So. On the record, a lot of what he says here is absolutely not currently believed in the field. Just. No. BUT. There's a reason why I always recommend him anyway, and it's because if you're serious about doing a study of Irish Mythology, whatever we take that to mean...you will not be able to avoid this man. His ideas were very popular for decades and still often are to people who don't really focus on mythology. It's better to know where these ideas come from and to identify them than not, and O'Rahilly, in his defense, had an *excellent* knowledge of his sources. It's dense, it's difficult (rather like the author himself, from the accounts I've heard), but it's necessary if you really want to attack this.

Joan Radner, Fragmentary Annals of Ireland (22.50, normally 30)

There is so much weird shit in the Fragmentary Annals. So much.

Welsh

Patrick Sims Williams, Buchedd Beuno: The Middle Welsh Life of St Beuno (22.50 Euro, normally 30)

I know what you're thinking: "Why the FUCK are they recommending this book about a random Welsh saint? Answer: Because this is how I learned Middle Welsh. The introduction to Welsh at the front of the book + the VERY good index at the back is still one of the best ways to learn Middle Welsh. Also if anyone was watching the Green Knight film and going "Why is there a lady with her head chopped off?" this answers that question.

R. L. Thomson, Pwyll Pendeuic Dyuet: the first of the Four Branches of the Mabinogi, edited from the White Book of Rhydderch, with variants from the Red Book of Hergest (15 Euro, normally 20)

Once you've gotten enough of a hang of Middle Welsh to know the basics, it's time to dive into the classics, and what better way to do it than with the Mabinogi, starting at the very beginning, with the First Branch? Personally, I dislike a lot of Thomson's orthographic decisions, but, hey, it's the First Branch, and that's Middle Welsh orthography for you.

Ian Hughes, Math uab Mathonwy (22.50 Euro, normally 30)

The Fourth Branch, my beloved. Incest, rape, bestiality (well...pseudo bestiality, really), creating a new life while not being willing to deal with the consequences of it...it truly has it all. Not for the faint of heart, but absolutely worth the read if you can stomach it because imo it handles its themes very well and it's incredibly haunting.

And a lot more -- go in, shop around, see what's available. Even with the older books, they're often things that we're still referencing in some way into the present.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elffin / エルフィン, Myrddin / ミルディン, and Merlinus / マリナス

Elffin (JP: エルフィン; rōmaji: erufin) is a bard involved with the resistance on the Western Isles in Fire Emblem: The Binding Blade. He gets his name from a figure in Welsh mythology, Elffin ap Gwyddno, lord of Ceredigion. Before his lordship, Elffin's father asked him to catch salmon - to his surprise what he found in the water was not fish but a lone infant. He took up the baby, who was capable of speaking in eloquent poetry, and called him Taliesin. Taliesin was a semi-historical figure, called Ben Beirdd, or "Chief of Bards" for his skill with poetry and serving as the bard to multiple kings. According to legend, Elffin was imprisoned by the king of Gwynedd when he refused to sing his praises, as Taliesin was a more skilled bard and Elffin's wife was more loyal and virtuous than all of the king's court. The King of Gwynedd then sent his son to take the wedding band from Elffin's wife to prove a lack of chastity. Luckily, Taliesin was blessed with prophetic visions and knew the means to prevent Gwynedd from undermining his family.

As apparent from how much focus was given to him, The Binding Blade's Elffin pulls from aspects of Taliesin, borrowing his skills as a bard and his abilities as a seer. Additionally, Taliesin makes appearances in a few Arthurian tales like Culhwch and Olwen, where he acted as King Arthur's bard. This better ties him to the many existing allusions to the King Arthur mythos.

Elffin's true identity is that of Myrddin (JP: ミルディン; rōmaji: mirudin), the lost prince of Etruria. In Welsh legend, Myrddin Wyllt, also called Myrddin of Caledonia, is a bard accredited to poems found in The Black Book of Carmarthen and The Red Book of Hergest. In Welsh literary tradition are many poems presented as prophecies of coming battles; these are frequently attributed to the mind of Myrddin. It is said that after the death of King Gwenddoleu ap Ceidio, in the Battle of Arfderydd, Myrddin his adviser was driven to madness. He fled to the Caledonian Forest of Scotland, reflecting on that battle for the rest of his days. Or until saved by a saint, in modern Christianized adaptations.

There is plenty here already to relate to Fire Emblem's Prince Myrddin, but there is also an explicit connection made to Elffin. According to tellings of Elffin's imprisonment by Maelgwn Gwynedd, when asked to identify himself in the court of Gwynedd, Taliesin opened as such:

"Primary chief bard am I to Elphin,

And my original country is the region of the summer stars;

Idno and Heinin called me Merddin,

At length every king will call me Taliesin."

From the horse's mouth: Taliesin is Myrrdin, little sense as that makes. And so, the Etrurian Myrrdin and the bard Elffin, who is heavily based on Taliesin, are appropriately one and the same. And yet it goes deeper still.

Merlinus (JP: マリナス; rōmaji: marinasu) is a traveling merchant turned inventory manager and adviser to House Pherae in Fire Emblem: The Binding Blade and The Blazing Blade. Merlinus Caledonensis was another name for Myrddin Wyllt. And it was from Myrddin Wyltt, combined with a similar figure called Ambrosius Aurelianus, that Geoffrey of Monmouth created the character of the magician Merlin. Originally called Merlinus Ambrosius, he was a madman sired by an incubus, capable of prophecy and form-shifting magic. He used this magic to change the appearance of Uther Pendragon to that of his mortal enemy, so that he may bear a son - King Arthur - with the opposing king's wife in their own bed. Later French-based adaptations of the Matter of Britain would change Merlin from an insane visionary to a sagely wizard and adviser to Arthur from an early age. Merlinus, as Roy's tactician and adviser, is more based on the later versions of Merlin's character.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

agravain by @gringolet and lamorak by howard pyle, the opening lines of cuhlwch and olwen from the red book of hergest

[ID 1: digital lineart of agravain wearing detailed armour and holding a helmet of blood. next to it is a black and white illustration of lamorak wearing a surcoat with a matching shield. /end ID 1

ID 2: black script in an old manuscript. /end ID 2]

agravain and lamorak are classically the forbidden love due to their families having a blood feud and also agravain (& co) killing lamorak. it would infuriate gawain and the others, and given agravain's loyalty to his family would make excellent angst material. also it is very funny that agravain's biggest love rival is his mum.

cuhlwch and olwen are a classic example of a ship created to justify a quest, and they're also one of the oldest arthurian ships, which grants them a place in this tournament and in our hearts.

#agravaine#lamorak#cuhlwch#olwen#cuhlwch x olwen#cuhlwch and olwen#arthuriana ship bracket#arthuriana#arthurian literature#arthurian legend

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes from Ronald Hutton's lecture "Finding Lost Gods in Wales" from Gresham College

A major problem for locating Welsh paganism in historical terms is that there really is very little source material to work with, certainly not much medieval literature seems to have survived in Wales, at least when compared to other countries such as Ireland and Iceland. It was thought that several Welsh stories and poems reflected the presence of an ancient Druidic religion and thereby some form of paganism, but this idea has since been rejected. It is now believed these stories and poems originated much later, possibly dating to around 500 years after "the triumph of Christianity". Only four manuscripts written in the 13th and 14th centuries might contain some possible relevance to paganism. Hutton tells us that these are The Black Book of Carmarthen, The White Book of Rhydderch, The Red Book of Hergest, and The Book of Taleisin (so-called). About 11 stories from the White Book and Red Book were compiled into what was called The Mabinogion in the 1840s. None of these are stories are certain to be older than the 12th century, although the oldest stories in the Four Branches of the Mabinogion may have been written as far back as 1093, and according to Hutton some of the stories of the Mabinogion were actually inspired by foreign literature, including not only French troubadour stories but also Egyptian, Arabic, and Indian stories that were brought to Europe.

Hutton notes that, unlike in medieval Irish and Scandinavian literature, the stories of the Mabinogion don't seem to feature any gods or goddesses or their worshippers (at least not explicitly anyway), despite being set in pre-Christian times. Many characters have superhuman abilities, but it's apparently not clear if these are meant to be understood as gods, or magicians, or just narrative superhumans. If there are pagan survivals in these stories, it may be the presence of an otherworld realm called Annwn, often equated with the underworld, and/or the presence of shapeshifting abilities (and on this point I believe Kadmus Herschel makes a convincing point in True to the Earth about this being reflective of a non-essentialist pagan worldview). Of course, Hutton believes that these are generalized themes and no longer linked to paganism in themselves, but of course I'd say there's room for skepticism here (I'm not exactly picturing a Christian Annwn here).

An important figure within the Four Branches of the Mabinogion is Rhiannon, a woman from Annwn who often believed to be a surviving Welsh goddess or survival of the Gallo-Roman goddess Epona. Her marrying two successive human princes has been interpreted as signifying Rhiannon as a goddess of sovereignty. Hutton argues that this is not certain because Rhiannon does not confer kingdoms to her husbands, there is no clear sign of a sovereignty goddess outside of Ireland or British horse goddesses in Iron Age archaeology or Romano-British inscriptions. Hutton argues that it's more likely that Rhiannon was a member of human royalty or nobility rather than a goddess. Of course, this is perhaps a zone of contestation. Hutton does not deny the possibility that Rhiannon was a goddess, but believes that the decisive evidence is lacking. For what it's worth, Rhiannon is a unique figure in the literature of the time, as a being from the otherworld who chooses live in the human world and willing to stay there even after every misfortune or crisis she encounters, responding to every problem with an indomitable and perhaps "stoical" willpower and courage.

The mystical poems, or the court poets from 900-1300, are also thought to contain some aspect of lost Welsh paganism. These were to be understood as a kind of artistic elite that delighted in prose that was sophisticated to the point of being almost beyond comprehension. They apparently believed that bards were semi-divine figures, permeated by a concept of divine inspiration referred to as "awen". They drew on many sources, including Irish, Greek, Roman, and even Christian literature, but also apparently the earlier Welsh bards. Seven mystical poems are credited to Taliesin, and these could be dated any time between 900 and 1250, though contemporary scholars typically favour 1150-1250 as the likely timeframe. Despite probably being written at a time when Wales was likely already Christianized, the poems are repeatedly referred to as sources of paganism and ancient wisdom by modern commentators.

The poem Preiddeu Annwn is one "classic" example. It is the story of an expedition into the realm of Annwn, which is undertaken to bring back a magical cauldron. The poem that we have seems to be explicitly Christian, but it is often believed that this is merely a Christian adaptation of an older pre-Christian text. But apparently no one really knows the real meaning of the Preiddeu Annwn, not least because no one can agree on what a third of the actual words in the poem mean. No one really knows if Taliesin was demonstrating a certain knowledge that only he possessed or what, if anything, he was referencing, so in a way we just don't "get" his poem.

Over the years the court bards ostensibly developed a new cast of mythological characters, or simply an enhanced an older cast of characters, to the point that they seem superhuman or even divine, yet just as medieval as King Arthur or Robin Hood. One example of this is Ceridwen, a sorceress who first appears in the Hanes Taliesin. Court poets apparently interpreted her as the brewer of the cauldrons of inspiration, and eventually the muse of the bards and giver of power and the laws of poetry. In 1809 she was called the "Great Goddess of Britain" by a clergyman named Edward Davies, which has been taken up by many since. Then there's Gwyn ap Nudd, who appears in 11th and 12th century texts as a warrior under the command of King Arthur. In 14th century poetry he seems to have been interpreted as a spirit of darkness, enchantment, and deception, and in the 1880s professor John Rhys identified him as a Celtic deity. Another major character is Arianhrod, who first appears in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion as a powerful enchantress whose curses were unbreakable. Over time it was also believed that she could cast rainbows around the court, the constellation Corona Borealis was dubbed "the Court of Arianrhod", and somehow since the 20th century she was identified as an astral goddess.

Then we get to the canon known as "Arthurian legends": that is, the stories of King Arthur. Hutton says that these tales originated as stories of Welsh heroes who fought the English, and these stories also contained what are thought to be residual pagan motifs. One example is the gift of Excalibur from the Lady of the Lake, which is either based on memories of an older pre-Christian custom of throwing swords into lakes, the rediscovery of an older custom through finds, or even a persisting medieval custom of throwing a knight's weapons into a water. The Dolorous Blow which strikes the maimed king and turns his kingdom into a wasteland is thought to suggest a residual belief in the link between the health of a king and the health of a land, though the blow itself is inflicted by a Christian sacred object. The Holy Grail is often believed to derive from a pre-Christian sacred cauldron, but it was originally just a serving dish before becoming a Christian chalice.

And of course, there's Glastonbury, featuring as the Isle of Avalon, the refuge and possible burial site of Arthur. It has been thought since at least the 20th century that Glastonbury was a centre of paganism, but no remains have been found there which might suggest the presence of a pagan reigious site. And yet, in 2004, some prehistoric Neolithic post-holes were discovered near the Chalice Well garden in Glastonbury after the Chalice Well house started a kitchen extension. Although no deposits were found that suggest anything about the religious life of the area, the point stands that it was the first trace of anything Neolithic at Glastonbury. But there is perhaps always more to be found. As Hutton says, there are always new kitchen extensions, garden developments, street work, or any other renovation that might result in archaeological excavations, and we could find almost anything at any time. For my money, if there's hope anywhere, it's in that. Almost makes me want to get back into my childhood metal detecting hobby. It would certainly have a purpose: to rediscover anything from our pre-Christian past that could possibly be found.

From the Q&A we can incidentally note that many contemporary artefacts of Welsh national/cultural identity are very modern, they have nothing to do with some ancient past, but they weren't always to do with the romantic nationalism of Iolo Morganwg. The daffodil, for example, was probably first taken up as symbol of Wales in 1911, during the investiture of the then Prince of Wales. The leek, on the other hand, seems to have been symbolically associated with Wales since the Middle Ages, possibly as a reference to St David as his favorite dish, or possibly as a less then flattering reference to Welsh agriculture. The dragon, or rather Y Ddraig Goch (literally "the red dragon") as it is called here, dates back to a medieval narrative about a tyrannical king named Vortigern. He tries to build a castle but it repeatedly collapses, and according to the legend that's because two dragons, one red and the other white, are always fighting beneath the ground. The white dragon is supposed to represent the English and/or the Saxons, while the red dragon represents the Welsh and/or Celtic Britons. Although traditionally, at that time, Welsh princes took up the lion as their symbol much like English and other European royalty did, the Tudors established the red dragon as an official heraldic symbol of Wales to distinguish from English iconography, and that has been a mainstay of Welsh culture ever since. All-in-all, however, probably nothing to do with paganism here, unless the dragon has some older significance that we don't know about (and I'm inclined to be charitable here, considering that dragons in Christian symbolism usually represent Satan and/or evil).

There is the suggestion that Arianrhod is to be identified with Ariadne, the Cretan princess who became the lover and consort of the Greek god Dionysus. Both Ariadne and Arianrhod are associated with the Corona Borealis, which in Greek myth was a diadem given to Ariadne as a wedding present from Aphrodite. But that's about it. Any identification based solely on that would be a stretch.

There is the discussion of the legend of Bran, or Bran the Blessed, a king of Britain whose head was said to be buried in a part of London where the White Tower now stands. Hutton says it's possible that this may have reflected an ancient pre-Christian custom of burying parts of "special" people in "special" places to give them enduring magical/divine power, or alternatively that it references a Christian tradition of similarly venerating the relics of saints (itself possibly adapted from pre-Christian traditions in the Mediterranean, but that's another story; any input on that subject though would be much appreciated!). Hutton suggests that Bran's head being specifically buried beneath The White Tower is one of the best indications that the Four Branches of the Mabinogion as we know them were composed no earlier than the early 12th century, because the White Tower was built by William the Conqueror in 1080, and the Norman occupation in Wales as well as England at the time was part of the backdrop of the writing of the Four Branches. Hutton also suggests that stories concern parables from a distant, lost ancient time that were marshalled by Welsh poets who applied them as lessons for how to survive in the present, against the threat of Norman occupation. I should like to have answers on that front, because something about the reactivation of a distant past against the present order resonates very well with Claudio Kulesko's concept of Gothic Insurrection. It makes for interesting horizons, especially when applied to radical political dimensions relevant to things like the question of political identity in the context of the British union.

Relating to the legend of Wearyall Hill, the place in Glastonbury where Joseph of Arimathea supposedly planted the "holy thorn", there is the point made by the late historian Geoffrey Ashe (who, incidentally, died in Glastonbury) that none of the legends concerning Glastonbury have been or even can be disproved, which means that they all just might be correct. Hutton seems inclined to take what could be described as the "glass half full" side of that problematic, in that he thinks the great thing about myths and legends is that there also the possibility that there's something to them. I think that this presents possibilities for paganism, but in the sense that we are to look at it as an act of assemblage, or rather re-assemblage, and in a sense it works to the precise extent that we take it as medieval and contemporary mythology, without at the same time believing the lies that we tell ourselves through our romance and mythology.

Then there's the subject of the demonization of Gwyn ap Nudd in the Buchedd Collen, which incidentally counts as yet another Glastonbury legend. Hutton says that there is no doubt that Gwyn ap Nudd was demonized by Christians, but says that this was not specifically the work of the St. Collen myth. The legend of St. Collen was already fairly well-established in the Middle Ages, and the Welsh town of Llangollen takes its name from St. Collen. The legend goes that Collen was preaching in Glastonbury when Gwyn ap Nudd had taken over the Glastonbury Tor (Ynys Wydryn) and set up a mansion from which to tempt and seduce the inhabitants with vices and pleasures. Collen then goes to Gwyn ap Nudd's mansion and sprinkles holy water everywhere, causing it to explode and leave nothing but green mounds. Hutton suggests that by the 14th century Gwyn ap Nudd was already interpreted as a demon, but we don't really know how or why that happened. Here a horizon of assemblage emerges from the context of Christian demonization.

Gwyn ap Nudd, if taken as a Welsh or Brythonic deity, is interesting to consider as a demon invading Glastonbury and being exorcised by a Christian monk with holy water. There's an obvious question, albeit one that may have no answer: why does Gwyn appear as the subject of an exorcism myth in the context of a Christianized society? It seems plausible to consider Christians interpreted Gwyn ap Nudd as a demon by way of his already being the ruler of Annwn, an otherworld realm then recast as Hell. It may also be possible that Gwyn was a persistent reminder of an older pre-Christian polytheism, even if it's unlikely that he was actually worshipped by anyone living in the Middle Ages. Everything sort of hinges on the fact that the figure of Gwyn ap Nudd was pre-eminent enough in medieval culture, and enough of a thorn on the side of the Christian imaginary, to first of all be recast as an evil demon and then become the central antagonist of the legend of a Christian saint who exorcises him. That might allow Gwyn's presence in the legend to be interpreted as symbolic of the pre-Christian past, albeit through Christian eyes, and a figure who could represent its potential reactivation in Wales.

Lastly, there's the matter of apparent similarity between Welsh and Irish mythology, and the idea of a shared "Celtic origin" between them, in which we are again at a crossroads of possibility. That whole connection comes with a problem: there are definitely similarities between the Irish and Welsh characters at least in name, but these characters also to tend to share names more than they share almost anything else. The two explanations are either that these characters were deities that were worshipped in pre-Christian Wales as well as Ireland, or that Welsh authors were just well-acquainted with Irish folklore and literature and simply borrowed ideas from there. Hutton suggests that the first explanation may not be entirely wrong, or at least not completely invalidated, and leaves it up to the individual to decide between the two possibilities. It is very difficult to be certain is the first possibility holds up, and I have the suspicion it might not, at least not sufficiently. But it doesn't seem totally impossible, given the resonances between the mythical figures in Wales vs the pre-Christian gods of other lands. A relevant example would be Nudd, or Lludd Llaw Eraint, the mythical hero whose name was cognate with the Irish Nuada Airgetlam and apparently derived from the name of the ancient god Nodens. Not to mention Lleu Llaw Gyffes coming from the name of the Celtic god Lugus. That presents the slim possibility of connection, and perhaps assemblage by way of Irish myth.

If you want to see the full thing I'll link it below, here:

youtube

#wales#welsh paganism#britain#celtic polytheism#welsh literature#medieval literature#paganism#brythonic polytheism#glastonbury#arthurian legend#mabinogion#welsh mythology#british mythology#celtic mythology#gothic insurrection#Youtube

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

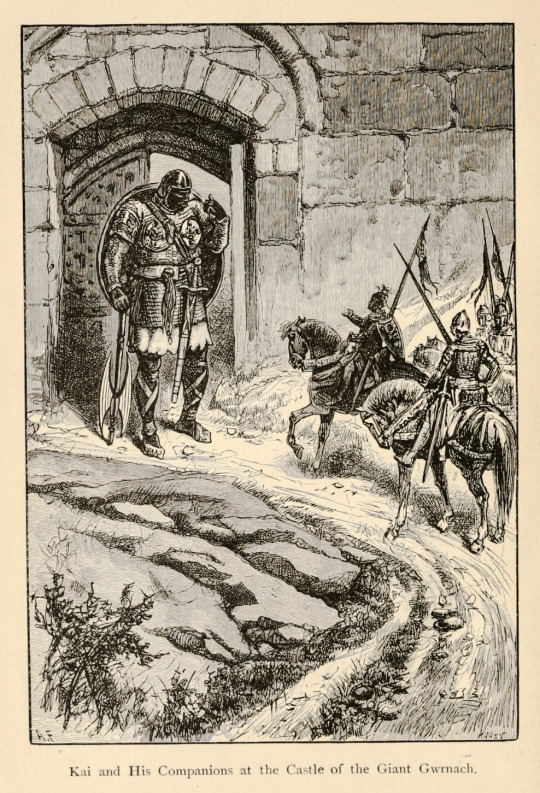

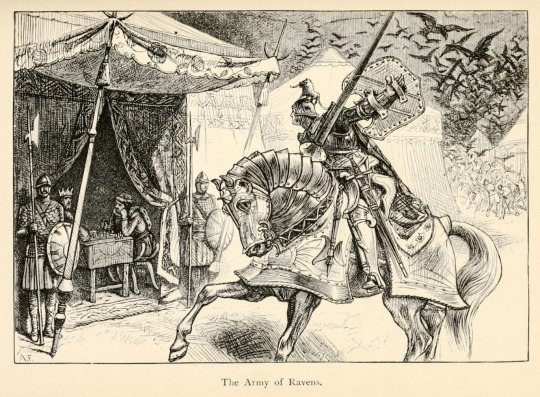

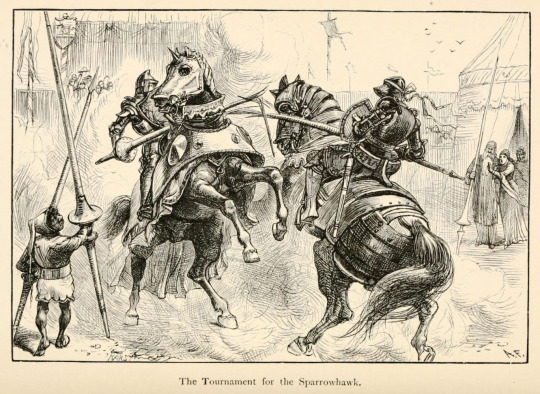

THE BOY’S MABINOGION edited for boys by Sidney Lanier. (New York: Scribners, 1881). Illustrated by Alfred Fredericks.

Being the earlest Welsh tales of King Arthur in the famous RED BOOK OF HERGEST

source

#beautiful books#book blog#books books books#book cover#books#illustrated book#vintage books#children’s book#victorian era#the mabinogion#welsh mythology#king arthur

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

from the medieval welsh englyn poem claf abercuawg (ed. jenny rowland, my translation)

the untamed englyn series

#cql#the untamed#mdzs#mdzsmultilingual21#wangxian#englynion#llyfr coch hergest#red book of hergest#welsh#cymraeg#wei wuxian#lan wangji

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

❤️🔥Rhiannon’s Fate❤️🔥

Edition of 12 printed on warm white Rives BFK heavyweight with oil based ink & painted with Ecoline Liquid Pigments

#rhiannon#welsh horse goddess#wales#the mabinogion#red book of hergest#mabinogion#mythology#celtic#celtic mythology#celtic myth#welsh myth#welsh mythology#linoprint#linocut#lino#art prints#printmaking#illustration#traditional illustration

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is there like. An arthuriana side of tumblr. Welsh tales? Triads? The four branches....? The Mabinogi? The red and white book?? Culhwch and Olwen? Rhonabwy?? Y gododdin?? Hi for the love of god hello????

#need. talk#I’m just sitting here#spamming keywords annoyingly like I’m staring directly at anyone who knows anything about these and twirling my hair#Len text#arthuriana#mabinogi#Mabinogion#red book of hergest#white book of rhydderch

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

In very basic summary, this is how I feel in regards to the continual arguments against the many mighty characters in the Mabinogion NOT being dieties.

I understand they may not be dieties and there's a rather grand lack of evidence in favor of them being dieties. Nonetheless I have heard the Cwn Annwn in my dreams and felt the presence of them in my day to day life. Even if they may not have been some sort of pre Christian, Welsh pagan dieties it does not de-note the modern day practioners and followers. The powers are there and the wonder is real.

#white book of rhydderch#red book of hergest#gwenhwyfar#blodeuwedd#welsh mythology#mabinogion#british folklore#celtic#welsh#wales#witchcraft#welsh folklore#welsh witch#welsh witchcraft

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthurian Annotations: 'Once And Future' #19 And The Origins Of Merlin

Arthurian Annotations: @kierongillen and @DanMora_c 'Once And Future' #19 And The Origins Of Merlin

With the return of Kieron Gillen and Dan Mora’s Once and Future this past week one of the major players I have yet to tackle in my frequent ‘Arthurian Annotations’ is Merlin. A half-man, half-demon that is a figure at the heart of most retellings and re-imaginings of the legend.

Like so many other Arthurian elements, Merlin was introduced by Geoffrey of Monmouth into his 12th century work, The…

View On WordPress

#Black Book of Carmarthen#Boom! Studios#Dan Mora#Geoffrey of Monmouth#Keiron Gillen#King Arthur#Merlin#Red Book of Hergest#The History of the Kings of Britain

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seuss Prompts Day 7: Wonder

Prompt from @writeblrs March Seuss Prompts.

A younger Gemma experimenting with potions before the events of Heart to Heart.

WC: 398

Maybe… No, that probably wouldn’t work.

But it might.

Worth a shot, right?

After hurriedly writing down the seven herbs on a sticky note, Gemma jumped up from her workstation and hustled down the hallway toward her component pantry. A wall of neatly labeled jars, corked beakers, and narrow plastic bins greeted her when she flicked the light switch.

“Mugwort, mugwort, mugwort…” she mumbled, and dragged her finger down the lines of shelves.

The old recipe didn’t say what part of the plant to use. Or how to prepare it. Or anything useful, really, so she was on her own, as usual. Good thing she knew what she was doing.

Seeds wouldn’t work here, since it needed to be ingested. Maybe an oil would be best. Typically, it’s lit on fire, so she could boil it and include it that way. Usually, leaves were incorporated as tea.

“Mugwort!” she chirped, grabbing the beaker and returning it to her workstation. Only six more ingredients to find and integrate. No problem.

_

Slight problem.

When her mother taught her how to interpret the Red Book of Hergest in conjunction with modern herbalism practices, she didn’t really explain individual recipes. Like this cure for fevers. Which, in modern terms, meant “flu stuff.” That meant it was time to improvise.

She’d steeped, the mugwort, meadowsweet, hemp, and milfoil leaves into a tea that smelled like fresh laundry. She’d stared at the madder root until she remembered she had to grind it before adding it in. After googling Korean and Chinese traditional medicine, she cooked the red cabbage into a clear broth. The last step in the components process was to find a vial of tutsan oil in the pantry. Combining them all was fairly simple. Tea first, then three drops of oil, and then titrate the broth into the mixture.

And because this was for Oz’s niece, and Gemma knew that kid had a sensitive stomach, she added a few drops of agrimony tincture and topped the whole brew off with a sprinkle of cinnamon. Kids liked sweet. Plus, without it, this potion would taste like old wet dirt.

All that was left was to wait for the color to change.

Two minutes of spinning around on her stool and humming Miley Cyrus later, Gemma smiled as the beaker sparked and flushed a rosy pink. Perfect.

Sometimes, experimentation really paid off.

H2H WIP Tag | Character Page | WIP Page

Character Tags: Gemma | Mel | The Ladies | Fred Coriander | Officer Oz

Tag List: @katekyo-bitch-reborn @cawolters @wasting-ink-not-youth @quilloftheclouds

(Let me know if you want to be added or removed!)

#seussprompts#seussprompts day7#writeblr#writing#amwriting#seussprompts2019#fiction#original fiction#spilled ink#fantasy#apothecary#potions#bookenders original#heart to heart#Gemma#red book of hergest#this involved lots of googling#like a metric ton of googling#all my ads will be for herbal remedies now

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Usual

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Welsh lake no bird will ever fly over and 9 other dark myths from the waters of Wales

From WalesOnline - which as a website is guaranteed to almost always crash your computer from the sheer number of clickbait popups so I'm reposting the below to keep, and refer back to, without making my laptop sound like its full of bees... and to share with you of course, since it's spooky-season

by Nathan Bevan, senior reporter. 15 October 2021.

📷The remains of ancient forests on the Welsh coastline, linked to Cantre'r Gwaelod, the mythical ancient kingdom submerged under the waters of Cardigan Bay (Image: Keith Morris)

Wales is as famed for its breathtaking scenery as for its legends.

And some of those fantastical myths and fables have been hewn from the very landscape itself. Some tales are as tall as our most ancient oaks and as windswept as those undulating hills and vales.

But those born from its lakes, pools and rivers, like the ones which we're about to tell, are very deep and dark indeed....

Llyn Tegid

📷 Llyn Tegid is home to Wales' answer to Nessie (Image: Getty Images/iStockphoto)

According to legend, Tegid Foel had a fine palace now underneath the lake and lived a life of opulence and excess. He also had a reputation for cruelty and greed. During a lavish feast he had employed a harpist to entertain his guests. As he played, he thought he heard a quiet voice behind him whispering in his ear “vengeance will come”. After playing, he left the palace and fell asleep nearby. When he woke, he looked out on an entirely new landscape, now full of water, with the palace nowhere to be seen.

The Afanc Lake monster

People in Betws-y-coed tell the tale of a monster in nearby Llyn-yr-Afanc, which is sometimes referred to as the Welsh Loch Ness Monster.

The Afanc is said to have taken the form of a crocodile, giant beaver and a demon and was said to attack then eat anyone who entered its waters.

One tale said that the wild thrashings of the Afanc caused flooding which drowned all the people of Britain save for two, named Dwyfan and Dwyfach.

Other sites also lay claim to be home to the Afanc, among them Llyn Llion and Llyn Barfog.

Pistyll Rhaeadr Falls

Another legend that involves good triumphing over evil is that of the Dragon of Llanrhaeadr at Rhaeadr Falls in Powys.

It concerns a winged snake called a Gwybr that lived in the lake above the falls which would fly down to terrorise the villages below.

However, the canny villagers mocked-up their own dragon to trick the Gwybr and, upon attacking it, the creature impaled itself on spikes hidden therein. thus allowing the villagers to live in peace.

The Lady of the Lake

📷 Llyn y Fan Fach (Image: Creative commons/ Flickr/ Angel Ganev)

The story goes that it was at Llyn y Fan Fach, a remote lake in the Black Mountains, where a young farmer named Gwyn won and then tragically lost the love of his life.

He fell in love with a beautiful woman who emerged from the water and agreed to marry him but warned him she would leave him forever if he hit her three times.

They lived happily for many years and had three sons, but after Gwyn struck her once for laughing during a funeral and again for crying at a wedding, an accidental third meant she disappeared into the lake never to been seen by him again.

She would sometimes re-appear to her sons and teach them the powers of healing with herbs and plants.

They became known as the Physicians of Myddfai and some of their ancient remedies have survived and are in the Red Book of Hergest, one of Wales' most important medieval manuscripts.

Cadair Idris

One of Wales' most iconic peaks, standing in southern Snowdonia, its name directly translates as Idris' Chair in reference to the mythical giant who once used the mountain as his throne. There are numerous stories and legends associated with the mountain and Idris.

A few of the nearby lakes - such as Tal-y-llyn - are reputed to be bottomless, and those who venture up the mountain at night should take heed before sleeping on its slopes. It is said that those who sleep on the mountain will awaken either as a madman, a poet or, indeed, never wake again.

Cantre'r Gwaelod

The kingdom of Maes Gwyddno, more commonly known as Cantre’r Gwaelod, is said to lie under the Irish Sea in Cardigan Bay. It was ruled by Gwyddno Garanhir (Longshanks), born circa 520AD, and the land was said to be extremely fertile but depended on a dyke to protect it from the sea.

The dyke had sluice gates which were opened at low tide to drain the water from the land, and closed as the tide returned. But, around 600AD, a storm blew up from the south west and the appointed watchman was too drunk to notice the and to shut the gates. The water gates were left open, and the sea rushed in to flood the land of the Cantref, drowning more than 16 villages.

The haunted shores of Rhossili Bay

It might be one of Britain’s best beaches, but beautiful Rhossili on the tip of Gower is also a hotspot for paranormal activity.

There have reportedly been sightings of a mysterious couple in Edwardian dress at the National Trust-owned Rhossili Rectory, while, supposedly, the spirit of Reverend John Lucas can be seen galloping across the sand on his ghostly horse.

The Reverend shares the beach with Squire Mansell who, on stormy nights, is said to search the sands for buried gold in a carriage drawn by four ghostly horses.

The great flood of Gorslas and Llyn Llech Owain

There was once said to be a magic well on the mountain Mynydd Mawr, which lies just north of Gorslas. The entrance to this well was protected with a huge flagstone, which was watched over by a local farmer.

One day, a thirsty young man named Owain came by the well and removed the stone so he and his horse could drink the water within. The pair then fell asleep shortly after without covering the well back up. Masses of flowing water then flooded the land, which was only stopped after Owain galloped around it on horseback, using his magic to contain it. The resultant lake on Mynydd Mawr was hence named Llyn Llech Owain (the lake of Owain’s stone slab).

Cwm Idwal

📷Cwm Idwal, Snowdonia (Image: Les Haines/Flickr)

The lake in this valley is named after a young man who died a tragic and unnecessary death. Legend has it that Idwal was the son of the 12th century prince Owain Gwynedd.

Beautiful and clever, Idwal did not have the makings of a warrior and was sent away to stay in safety with his uncle, Nefydd, while his father was at war. Nefydd was a jealous man whose own son Rhun, in contrast to Idwal, was witless and dull. Torn apart by bitterness, Nefydd took the boys for a walk by the lake and pushed Idwal in, drowning him.

Owain was devastated and named the lake after his son. Legend has it that the birds that inhabited the lake flew away in sorrow, never to soar above it again.

Tyno Helig, the Welsh Atlantis

One of the legends associated with the Great Orme, the massive headland to the west of Llandudno Bay, is that of Llys Helig (Helig's Palace) and the lost land of Tyno Helig.

The legends surrounds the daughter of Helig ap Glannawg, the prince of Tyno Helig, who is said to have lived in the sixth century. His daughter Gwendud had a cruel heart and when she was courted by Tahal, the son of a Snowdonian baron, refused to marry him unless he acquired the golden collar worn by noblemen of the time.

Tahal murdered a Scottish chieftain, stealing his collar, and the two were wed. But on the wedding day the ghost of the murdered Scots appeared, cursing the family. Some generations later, during a night of revelry in the royal palace, sea water began pouring into the cellar before completely submerged the palace. Many believed this was the revenge the Scottish chieftain had promised.

#....for reference... 👀👀#chwedloniaeth cymraeg#long post#spooky season#Wales#Cymru#welsh folklore#Welsh myth#I've never seen a ghost but honestly I wouldn't be surprised if rhossili was haunted!#I think I have a spooky photo of rhossili from when the weather was shocking but i drove there for my birthday regardless#I'm surprised they couldn't find one suitable for the article....#Welsh legends#mythology#legend#spooky#ghost stories#ysbrydion#cantre'r gwaelod#cwm idwal#cadair idris#llyn y fan fach#halloween#calan gaeaf

122 notes

·

View notes