#roberta close icon

Text

Heaven, I'm in heaven...

Script below the break

Hello and welcome back to The Rewatch Rewind! My name is Jane, and this is the podcast where I count down my top 40 most frequently rewatched films in a 20-year period. Today I will be discussing number five on my list: RKO’s 1935 musical comedy Top Hat, directed by Mark Sandrich, written by Allan Scott and Dwight Taylor, and starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

American dancer Jerry Travers (Fred Astaire) comes to London to star in a show produced by his friend Horace Hardwick (Edward Everett Horton). The night before the show opens, Jerry’s tapdancing in Horace’s hotel room awakens model Dale Tremont (Ginger Rogers) in the room below. She calls the manager to complain, who calls the room above hers, and Horace answers the phone. Because he can’t hear over Jerry’s dancing, he leaves to see what the manager wants. Tired of waiting for the noise to stop, Dale storms upstairs to confront the dancer. Upon seeing her, Jerry immediately falls in love, and the next day he starts following her around in a mildly creepy but mostly charming way. However, he never tells her his name, and when Dale learns that her friend Madge Hardwick (Helen Broderick)’s husband is staying in the room above hers, she naturally assumes that Jerry is Horace Hardwick. All of this results in much confusion, hilarity, and of course, dancing.

Top Hat was one of the many old movies that my mom introduced me to in 2002, and it has been among my favorite films ever since. I had already seen it several times before I started keeping track, and then I watched it five times in 2003, three times in 2004, three times in 2005, once in 2006, once in 2009, twice in 2010, three times in 2011, four times in 2012, once each in 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017, and 2018, twice in 2020, once in 2021, and once in 2022. This was the first Fred and Ginger movie I ever saw, and while I’ve since watched and enjoyed all nine others multiple times, none could top Top Hat, in my opinion.

This was the fourth film that Fred and Ginger made together, but only the second in which they had starring roles, and the first that was written specifically for them. Two of their previous films – 1933’s Flying Down to Rio and 1935’s Roberta – gave them relatively small parts, although their scenes were unquestionably the highlights. In Flying Down to Rio, they got fourth and fifth billing and are barely in it, but they caused a splash with their one dance number, and an iconic duo was born. They got second and third billing in Roberta, in which they basically function as the B romantic pair, with Irene Dunne and Randolph Scott as the A couple. Fred and Ginger’s first starring roles had been in 1934’s The Gay Divorcee, which was an adaptation of the Broadway musical Gay Divorce. Critics of Top Hat (including Astaire himself) complained that it was basically a rehash of The Gay Divorcee, and like, I can see their point: both films have a weird mistaken identity story and feature essentially the same cast filling very similar roles – with the notable change from Alice Brady to Helen Broderick in the “Ginger’s older relative/friend” role. But while I also enjoy The Gay Divorcee, somehow I feel like Top Hat just works better. The story makes at least a little bit more sense, and they didn’t devote a quarter of the runtime to a single interminable musical number like The Gay Divorcee did with the frickin Continental… although The Piccolino came dangerously close to replicating that. After Top Hat, Fred and Ginger made five more films with RKO in the 1930s: 1936’s Follow the Fleet, in which they were basically the B couple like they had been in Roberta, although they did get top billing in this one; 1936’s Swing Time, which is mostly very good and would probably have made it onto this podcast if not for that one blackface number; 1937’s Shall We Dance, which I kind of slept on for a while but now I think is probably my second favorite of theirs, although the ending drags a bit; 1938’s Carefree, possibly their weirdest movie, which involves hypnotism; and 1939’s The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle, which I find to be disappointingly forgettable. Then, after 10 years apart, they reunited for MGM’s The Barkleys of Broadway in 1949, which is basically Fred and Ginger fan fiction and it makes me so happy that it exists.

While there were lots of other dancing musicals being made in Hollywood around this time, the Astaire/Rogers ones feel like their own genre, and not just because of the stars. I think a big part of what makes Top Hat feel like the quintessential Fred and Ginger film is the supporting cast. Edward Everett Horton, Helen Broderick, Erik Rhodes, and Eric Blore were each in at least one other Fred and Ginger movie, but this is the only one that has all four of them. Edward Everett Horton excelled at playing the kind of guy who thinks he’s in control of every situation, but actually has no clue what’s going on, and he’s especially in his element as Horace Hardwick, convinced that he can get to the bottom of everyone’s strange behavior while never suspecting that he could end all the confusion just by meeting Dale. Helen Broderick delivers wisecracks in a brilliantly dry, cynical tone that contrasts with Horton’s bumbling to great comedic effect. Their characters don’t seem to have a very functional marriage, but they also don’t really seem to mind that. Typically the “haha, married couples hate each other” types of jokes really irritate me, but Horace and Madge are such ridiculous characters that it’s actually kind of funny when they do it. And then there’s Erik Rhodes, whose absurdly over-the-top Italian characterization in Top Hat and The Gay Divorcee so offended Mussolini that both those films were banned in Italy. Personally I feel like Top Hat’s portrayal of Venice as a giant white soundstage is probably more insulting to Italians than a guy doing a bad accent and being silly is, but I don’t know, maybe it’s still offensive. To me, as a non-Italian, I just think Erik Rhodes is very funny as Alberto Beddini, the dressmaker whose clothes Dale is modeling. He has some truly excellent lines, like, “Never again will I allow women to wear my dresses!” and “I am no man; I am Beddini!” Despite his declarations of love for Dale, he is extremely queer-coded, while also interestingly being one of the most masculine characters in the film, which is…kind of the opposite of how male characters are typically queer-coded. So Alberto is very silly but also quite fascinating. Eric Blore was in half of the Fred and Ginger movies and he’s always hilarious. In Top Hat he plays Horace’s valet, Bates, who always refer to themselves in the plural (“We are Bates, sir”), so the next time someone complains to you about this so-called newfangled trend of young people messing with pronouns, feel free to point out that at least one middle-aged man was doing that way back in 1935. One of my favorite exchanges in the movie is when Horace is trying to explain to Bates that Jerry seems to have gotten into a perilous situation with a woman by saying, “He has practically put his foot right into a hornets’ nest” and Bates respond with, “But hornets’ nests grow on trees, sir.” “Never mind that. We have got to do something.” “What about rubbing it with butter, sir?” “You blasted fool, you can’t rub a girl with butter!” “My sister got into a hornets’ nest and we rubbed HER with butter, sir!” “That’s the wrong treatment, you should have used mud – never mind that!” It has nothing to do with anything but it makes me laugh every time. This supporting cast adds a silly, somewhat Vaudevillian aspect to Top Hat that no Fred and Ginger film would be complete without.

Of course, Fred and Ginger movies are better known for a different somewhat Vaudevillian aspect: their songs. It’s very interesting to watch Top Hat from a musical history perspective because it was made before the advent of the book musical – that is, a show where the songs are fully integrated into the story and used to tell a specific narrative. The songs in this movie do sort of advance the plot, but the lyrics are generic enough that they stand alone completely out of context. It’s kind of a bridge between the disjointed songs and scenes of vaudeville and the continuously flowing story of book musicals. All the music in Top Hat was written by the legendary Irving Berlin, including two solo numbers for Fred: “No Strings (I’m Fancy Free)” which is what Jerry is dancing to in the hotel when he disturbs Dale, and “Top Hat, White Tie and Tails” which is part of his show; and three numbers for both Fred and Ginger to dance to: “Isn’t This a Lovely Day (to Be Caught in the Rain)?” for soon after they meet, before Dale thinks that Jerry is Horace, “Cheek to Cheek” when they’re in love but Dale is conflicted because she thinks he’s married to Madge, who is confusingly encouraging them to dance, and “The Piccolino” after Dale finally learns Jerry’s true identity. Both Astaire and Rogers were significantly better dancers than singers, but typically Fred did most of the singing, and the only song he doesn’t sing in Top Hat is the Piccolino, apparently because he didn’t like it, so Ginger sings it first and then an offscreen chorus repeats it. My favorite number in the film has always been “Isn’t this a Lovely Day (to Be Caught in the Rain)?” because I love the way Jerry starts dancing fancier and fancier and is pleasantly surprised that Dale can keep up with him, and it’s fun that Ginger got to wear pants for once, and I also just really enjoy that song. There was a time soon after I first fell in love with this movie when I tried to make saying the word “lovely” a lot part of my personality, mainly inspired by this song. I truly enjoy all the numbers, even if I do think The Piccolino goes on a bit too long, although, again, it’s not nearly as painfully long as The Continental in The Gay Divorcee, which it’s clearly meant to pay homage to. But Fred and Ginger’s most famous dance number – certainly in this film, and also probably in any of their films – is “Cheek to Cheek.” It is pure, breathtaking magic, and even knowing about the major drama with Ginger’s dress in no way detracts from that.

I’ve heard a few different accounts of the dress drama with slightly conflicting details, but what they all seem to agree on is that Ginger Rogers insisted that a low-backed, light blue, ostrich feather dress would look perfect during the “Cheek to Cheek” dance, and pretty much everybody else tried to talk her out of it, but she refused to back down until they were all forced to concede. And she was correct, it looks incredible, although if you’re watching closely you can see some feathers falling off while she dances, which was the main objection to the dress. Fred Astaire was reportedly extremely annoyed about the flying feathers, although he betrays none of that to the audience, and afterwards gave Ginger the nickname “Feathers,” which he continued to call her for many years. My interpretation of this is that it started as kind of an insult when he was genuinely upset about the incident but evolved to become more of a term of endearment, although obviously I don’t know for sure. As far as I can tell, apart from the occasional disagreement, Fred and Ginger got along pretty well in real life, although the studio sometimes invented or exaggerated stories about them fighting to try to generate more buzz. Personally I don’t think that was necessary; their talent spoke for itself, and audiences would have flocked to their films whether or not there was conflict offscreen.

One thing that I don’t like about old movies is that in general, most of the people who worked on them were deceased before DVDs were invented, which means that the special features are often lacking. I have watched Top Hat with commentary, but it’s by a film historian and Fred Astaire’s daughter who was born after this movie was made. It’s mostly the historian talking, but every once in a while Astaire’s daughter shares a memory of her father, and every. single. time. the historian responds with, in the most patronizing tone of voice I’ve ever heard, “Thank you for telling us that” and I hate it so much. But one thing that I did learn from the commentary that I definitely wouldn’t have noticed if nobody had told me is that Lucille Ball makes a very small appearance in this movie as a worker at the flower shop in the London hotel. She has a couple of lines, but even though I’m used to watching her in Stage Door, which was only made two years after Top Hat, I absolutely would never have recognized her. So that’s kind of fun.

Now, when it comes to watching Top Hat from an aroace perspective, even I cannot deny that this movie in general, and the “Cheek to Cheek” number specifically, is extremely romantic. The main storyline is Jerry immediately falling for Dale and flirting with her until she falls for him, and then her attempting to suppress her feelings when she thinks he’s married to her best friend. But somehow, even watching it as a young teen who had no idea that I was aroace, this felt different from other romantic films I’d seen. I remember feeling irritated the first time I read a description of Fred and Ginger’s dancing as their version of making love because “ugh, why do people have to make everything about sex?” It took me a while to realize that not only is that an apt description, but it’s also part of what drew me to them in the first place. Because despite the way the terms “making love” and “being intimate” are now used almost exclusively as synonyms for “having sex,” they don’t necessarily have to be. There are other ways of experiencing and expressing love and intimacy besides sex. It’s just that our allonormative society puts sex on such a high pedestal and portrays it as the One True Form of Intimacy that all other forms are devalued to the point that often they feel barely worth mentioning. And I do feel like when some people talk about Fred and Ginger this way, what they’re implying is “Their dances were the Hays Code era version of sex scenes.” And, granted, it’s quite possible that that was the intent. But nothing about their dancing is inherently sexual, and yet, it would be hard to deny that it’s extremely intimate. So as someone who craves non-sexual intimacy, in a world where that concept almost seems oxymoronic, it’s so encouraging to see these characters express that. Of course, I don’t want exactly what they have – for one thing, I’m a terrible dancer, despite my one year of tap lessons in 2nd grade. And for another, what they have is way too romantic for me. But although I could never have articulated this at the time, just seeing this example of extreme intimacy coming in other, non-sexual forms as a young obliviously asexual person was so important. It gave me some armor against the onslaught of allo- and amatonormative messages implying that sexual relationships are inherently more valuable and valid than any other kind of relationship. Top Hat ends with the implication that Jerry and Dale are about to get married, so I guess we’re meant to infer that their relationship will eventually become sexual, but I don’t see how anyone could watch this movie and still think that a sexless marriage consisting of dance numbers like “Cheek to Cheek” would be any less valid than a sexual marriage. Like so many of my favorite movies, it’s not exactly ace representation, but it’s easy to imagine many of the characters in Top Hat as ace, and often that’s as good as it gets.

While the subtle and probably unintentional message that sex doesn’t have to be the end all be all is great, the main reason I love this movie is because it’s just a lot of fun to watch. I’ll be the first to admit that the plot is a little ridiculous and doesn’t make a ton of sense, but I also have to admire the lengths they go to in order to maintain the mistaken identity for so long. Like the part when the London hotel manager tells Dale that Horace Hardwick is the gentleman with the briefcase and cane on the mezzanine, and Horace steps behind a chandelier before Dale can see him, and while she’s trying to get closer, Jerry runs up to Horace and says that he has a phone call, and Horace hands Jerry his briefcase and cane and rushes off, so Dale will see Jerry alone holding a briefcase and cane and therefore still think he is Horace. Or when Horace just happens to be in the bathtub when Dale comes into their room in Italy. Or how Jerry tells Madge that he’s met Dale so she doesn’t think she needs to introduce him. It’s like simultaneously the most far-fetched, bizarre plot imaginable and also kind of brilliantly executed, and I love it for that. And even if the plot doesn’t work for you, this movie is still worth watching for its truly phenomenal dancing by one of the most iconic pairs in Hollywood history.

Thank you for listening to me discuss another of my most frequently rewatched films. When compiling this list, I was very surprised to discover that Fred Astaire would only appear in one film, since I consider him one of my faves, but I hope he would at least be happy to know that that one film is in my top five. Next week, I will be talking about another Old Hollywood musical that I watched two more times than Top Hat, for a total of 33 views, which stars a man who is often compared to Fred Astaire, although I feel like, apart from being dancers, they were very different. So stay tuned for that, and as always, I will leave you with a quote from that next movie: “I make more money than…than…than Calvin Coolidge! Put together!”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

A struggling young writer finds his life and work dominated by his unfaithful wife and his radical feminist mother, whose best-selling manifesto turns her into a cultural icon.

Credits: TheMovieDb.

Film Cast:

T.S. Garp: Robin Williams

Helen Holm: Mary Beth Hurt

Jenny Fields: Glenn Close

Roberta Muldoon: John Lithgow

Mr. Fields: Hume Cronyn

Mrs. Fields: Jessica Tandy

The Hooker: Swoosie Kurtz

Pooh: Brenda Currin

John Wolfe: Peter Michael Goetz

Cushie: Jenny Wright

Referee: John Irving

Ellen James: Amanda Plummer

Woman Candidate: Bette Henritze

Rachel: Katherine Borowitz

Real Estate Lady: Kate McGregor-Stewart

Michael Milton: Mark Soper

Stew Percy: Warren Berlinger

Ernie Holm: Brandon Maggart

First Coach: Victor Magnotta

Helicopter Pilot: Al Cerullo

Stephen: Ron Frazier

Marge Tallworth: Eve Gordon

Pilot (uncredited): George Roy Hill

Film Crew:

Producer: George Roy Hill

Screenplay: Steve Tesich

Novel: John Irving

Editor: Stephen A. Rotter

Director of Photography: Miroslav Ondříček

Producer: Robert Crawford Jr.

Executive Producer: Patrick Kelley

Casting: Marion Dougherty

Production Design: Henry Bumstead

Art Direction: Woods Mackintosh

Set Decoration: Robert Drumheller

Set Decoration: Justin Scoppa Jr.

Costume Design: Ann Roth

Hairstylist: Bob Grimaldi

Makeup Artist: Robert Laden

Movie Reviews:

#based on novel or book#childlessness#gay theme#homosexuality#love#paternity#pregnancy#Top Rated Movies#typewriter#wrestler#wrestling#writer

0 notes

Photo

The Vickers Family Art Collection Arrives at the Harn Museum

It’s moving day and the massive collection of Florida art has arrived at the Harn Museum of Art. Thanks to an extraordinary donation from Sam and Robbie Vickers, their once-private collection has found its public “forever home” at the Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida. Over a few days, I was able to document the behind the scenes process as Harn staff excitedly welcomed a truckload of more than 1,200 drawings, oil paintings, and watercolors — the largest single art collection ever gifted to the university.

The inaugural exhibition, A Florida Legacy: Gift of Samuel H. and Roberta T. Vickers, opens Feb. 26 and runs through Aug. 1, 2021. Art lovers will be able to marvel up close at Robert J. Curtis’s iconic 1838 portrait of Seminole leader Osceola; Winslow Homer’s action-filled Foul Hooked Black Bass; John Singer Sargent’s masterful Palm Thicket; Martin Johnson Heade’s rare Oleanders; Ralston Crawford’s soaring Overseas Highway #2; and Jane Peterson’s vibrant gouache, Toucans, Parrot Jungle — to name just a few of the delights on view.

#sam vickers#robert vickers#art collection#florida art#american artist#Winslow Homer#Robert J Curtis#Osceola#John Singer Sargent#Martin Johnson Heade#Jane Peterson#A Florida Legacy#Samuel P Harn Museum of Art#Harn Museum of Art#Harn Museum#uf#university of florida#aaron daye photography

0 notes

Text

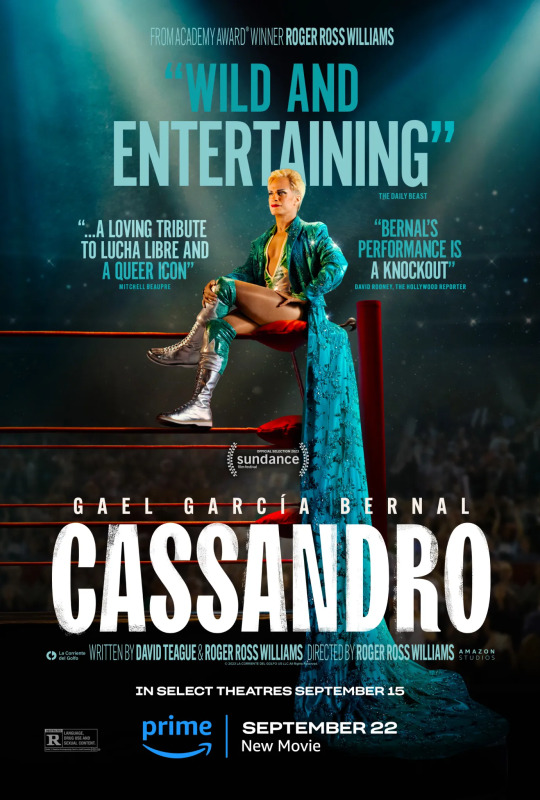

Mucha Libre - Film Review: Cassandro ★★★1/2

Who would have ever expected a film set in the ultra macho, extremely homophobic world of lucha libre wrestling to serve as a celebration of women and effeminate gay men? Director Roger Ross Williams along with co-writer David Teague have crafted such an experience with their biopic, Cassandro, the true story of Saúl Armendáriz, an underdog who achieved legendary status against all odds. With a fearless, career-defining performance by Gael García Bernal, this queer Rocky story has plenty of laughs and charm, but it also has real power in how it challenges gender conventions. It’s such a joy falling in love with Saúl.

When we first meet him, he’s an out gay, skinny 18-year-old living with his single mother Yocasta (the fantastic Perla De La Rosa) in late 1980s El Paso. His religious father left them when Saúl came out a few years prior, so he and his mom share a close bond. He works as an exótico in nearby Juárez, Mexico. Unlike the masked lucha libre wrestlers, exóticos don’t hide their faces and exist as the flamboyantly gay punching bags who purposefully lose their bouts to their more macho opponents while also getting brutally heckled by the audiences. Think of it as professional queer bashing. Undeterred and clearly made of stronger stuff, Saúl’s wheels start to turn after losing bout after bout.

Inspired by the women in his life such as his strong, courageous mother and his gutsy trainer Sabrina (an engaging Roberta Colindrez), Saúl creates his alter-ego, Cassandro, who sports leopard print leotards as well as makeup inspired by Yocasta, and vows to be the first exótico who wins. When he first enters the ring as Cassandro, defiantly baiting the booing crowd, feeding off of their slurs, camping it up wildly, his big gay hair flipped back just so, you can’t help but root for him. Just seeing him not bat an eye as he takes on a wrestler three times his size and give him a run for his money should inspire anyone who has ever felt threatened by a bully.

By this point, Teague and Williams have done such a great job of letting us fall in love with Saúl, warts and all. Sure, we may see him party perhaps a bit too hard and maybe trust people a little too easily, but his steadfast belief in himself keeps you riveted. His secret relationship with a closeted married fellow wrestler, soulfully played by Raúl Castillo, seems like a bad idea from the jump. Early on, he secures a manager, Lorenzo (Joaquín Cosío) who has a loving way of cheering Saúl on, but he also has an assistant Felipe, played nimbly by music superstar Bad Bunny (aka Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio) who provides an endless supply of cocaine whenever needed. This dichotomy goes under-explored and could have provided a little more conflict. Much of the external conflict, in fact, gets a little glossed over.

Regardless, Saúl’s journey has enough riches without it, culminating in a series of crowd-pleasing sequences guaranteed to get you cheering and turn on the waterworks. It also contains a brief, powerful scene which provides every queer person with the tools for how to respond to a parent who has rejected their child. Bernal’s performance in this scene, as he gazes directly into the camera, is subtle and gorgeous.

Special mention must be made of cinematographer Matias Penachino's work, which lovingly captures the 80s and onward without fetishizing the times. The film has a visual poetry, such as in a wonderfully intimate pool scene in which Saúl and his mother daydream at a house they’d one day like to purchase and it achieves grandeur in that truly iconic final shot. Same goes for J.C. Molina’s lived-in production design, which feels so vivid and true.

It’s worth pointing out that Mexico was ahead of the United States on such issues as marriage equality despite its image as an ultra-conservative, macho society. I’d like to think that not only the acceptance but the outright celebration of queer icons such as Saúl Armendáriz contributed to such a cultural shift. Late in Cassandro, Saúl goes on a talk show and names women, famous and otherwise, who have shaped his life. He embraces women. He embraces his own femininity. The world would be such a better place if we could all be more like Saúl, but barring that, I hope Cassandro gets people to at least open their hearts.

Cassandro opens in select theaters September 15th, 2023 and streams on Amazon Prime September 22nd.

0 notes

Text

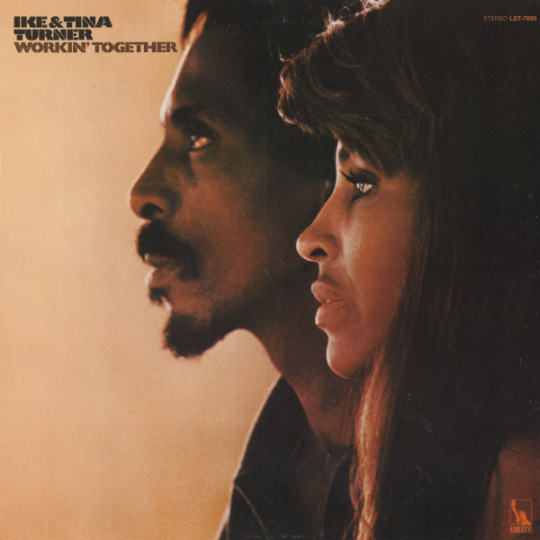

41: Ike & Tina Turner // Workin' Together

Workin' Together

Ike & Tina Turner

1970, Liberty

“Kenneth Anger and Tina Turner died on the same day,” my friend Jay broke the news to me yesterday afternoon. “And people say God isn’t homophobic.” (A bit later he added, “Apparently Martin Amis also died. So maybe God is bi,” which would explain His persecution complex, anyway.) Turner had been mythologized, homogenized, and eulogized a thousand times over well before her actual death at 83, and while a skim of her Wikipedia page suggests she’d been up to plenty over the past ten years (a weird Christian music foundation; a Broadway musical using her songbook; a hit on the UK charts featuring something called a 'Kygo'), unless she publicly forgave Ike or became Q-pilled, nothing was likely to change her legacy much.

Beyond the ‘80s pop megahits, that legacy rests on a period of her career (the ‘60s and ‘70s) that’s not adequately attested to by her LPs. Although the Ike & Tina machine churned out plenty of spectacular singles and b-sides (“River Deep – Mountain High,” “The Hunter,” “Nutbush City Limits,” “Contact High” etc.), they never delivered a wall-to-wall classic album. Their true power was as by all accounts the world’s greatest live rhythm & blues revue, driven by Ike’s stern leadership and Tina’s bottomless reserves of energy and mostly bottomless dresses.

Workin’ Together is generally considered their best studio effort, and it’s clear the goal was to capture as much of that live energy as they could. Like most of their albums, it mixes contemporary rock covers (Beatles, CCR), some new Ike originals (like the title track), and rinsed and reused re-takes on their early singles (“The Way You Love Me”; “Goodbye, So Long”). On Side Two in particular they deploy a lot of the tricks they used on stage: after rasping and strutting through the minor classic “Funkier Than a Mosquita’s Tweeter,” they milk a dramatic piano solo into (of all things) R&B chestnut “Ooh Poo Pah Doo.” A spoken intro by Tina follows while Ike croons lightly in the background, promising a ‘nice and rough’ rip through “Proud Mary”—and this is precisely what we get, on the album’s clear standout (and biggest hit). After a breath we’re into Ike’s “Goodbye, So Long” (another dance number they’d been playing since the mid-‘60s), followed by a vampy take on “Let It Be” that I’d happily take over the original.

Workin’ Together highlights Ike’s best and worst (musical) qualities. He was one of the great bandleaders in all of music for over 25 years, and he helped create Tina’s iconic style. He also embraced Black music’s movement toward funkier styles, styles he’d played a role in inventing. But he was also aggravatingly conservative, and his domineering management of Tina prevented her from flourishing as a recording artist to the degree peers like Aretha Franklin, Nina Simone, and Roberta Flack achieved. In another timeline, with the chance to work more closely with the great producers of the day, this might not be the best studio album she ever cut. But, despite plenty of great chart successes to come, she never bettered it.

41/365

youtube

#tina turner#ike turner#ike & tina turner#proud mary#workin' together#r&b#funk#rip tina turner#music review#vinyl record#kenneth anger#'70s music

1 note

·

View note

Photo

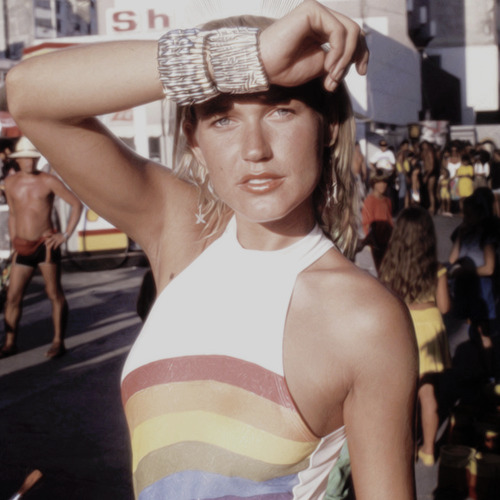

like or reblog.

#luiza brunet#luiza brunet icon#xuxa#xuxa icon#gloria pires#gloria pires icon#malu mader#malu mader icon#ana paula arosio#ana paula arosio icon#roberta close#roberta close icon#debora bloch#debora bloch icon#luma de oliveira icon#luma de oliveira#gisele bundchen#gisele bundchen icon#hj to inspirada em t80s#lutei muito pra fazer esses pqp#80s#80s icon#80s icons#brazil#brazil icon#o brazil ta matando o brasil#brasil#brasil icon#brasil icons#brazil icons

175 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roberta Close

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Most Important Review of Every Single Luca Marinelli Film

Listen, I’m not here to tell you if a movie’s plot is well-structured or whatever, ok? I’m here for objective, factual data on how Luca Marinelli’s brand is adhered to in every movie he’s been in so far.

(all gifs by @weardes)

La solitudine dei numeri primi (2010)

Does Luca smoke? No.

Does Luca sing? No.

Does Luca eat? No.

Does Luca get slapped? No. His life is hard enough as it is.

Is Luca naked? He’s wearing speedos in one scene, but he’s covered in s*lf-h*rm marks, it’s very sad and not sexy at all.

Is Luca gay? Hell if I know.

Is Luca a slut? He talks to like two people in the whole movie.

Lucameter: 2/100 pathetic (but like I get it it’s his first movie w/e)

L'ultimo terrestre (2011)

Does Luca smoke? Yes.

Does Luca sing? No, but Roberta is a captivating dancer.

Does Luca eat? No, though she takes a shot once.

Does Luca get slapped? Yes, but not in a fun way :(

Is Luca naked? No, but there are some thighs and belly with a mini skirt in between. No complaints.

Is Luca gay? Not enough data.

Is Luca a slut? No.

Lucameter: 1/100 horrible, Roberta deserved better

Waves (2011)

Does Luca smoke? No.

Does Luca sing? Yes, drunkenly!

Does Luca eat? They just won’t let him put food into his mouth! Watching Gabriele trying and failing to eat is Hitchcock-level suspense, though it all comes to a very satisfying conclusion when the camera isn’t focusing on him for a second, and he friggin’ inhales the food off the table.

Does Luca get slapped? No, but he gets pushed around a lot.

Is Luca naked? No, but he does take off his shirt a couple of times. Also his legs are like completely hairless?? Has anyone ever noticed that? They shaved his legs!

Is Luca gay? No proof that he is, no proof that he isn’t.

Is Luca a slut? No, he is the sweetest purest cinnamon roll.

Lucameter: 37/100 it’s getting better

Nina (2011)

Does Luca smoke? No.

Does Luca sing? No, but he plays the cello and dances.

Does Luca eat? No.

Does Luca get slapped? No.

Is Luca naked? No, though even if he was, you wouldn’t be able to enjoy it because he never gets any close-ups or decent lighting.

Is Luca gay? He’s shown to be into ladies.

Is Luca a slut? Please, he’s barely even a character.

Lucameter: 0/100 unwatchable

Tutti i santi giorni (2012)

Does Luca smoke? No.

Does Luca sing? No.

Does Luca eat? Yes, and he cooks!

Does Luca get slapped? Yes, lightly, in a patronizing way.

Is Luca naked? Oh yes.

Is Luca gay? He’s religiously devoted to his lady love.

Is Luca a slut? Not so much a slut as a hella thirsty bitch.

Lucameter: 43/100 half down ponytail saves lives

Maria di Nazaret (2012)

Does Luca smoke? No, obviously.

Does Luca sing? No. He dances once - very clumsily.

Does Luca eat? No.

Does Luca get slapped? No, though he almost drops a house on himself.

Is Luca naked? Guys, it’s a Bible movie.

Is Luca gay? Come on, he’s Saint Joseph.

Is Luca a slut? Lol no.

Lucameter: -10/100 just for that hair

La grande bellezza (2013)

Does Luca smoke? No.

Does Luca sing? No.

Does Luca eat? No.

Does Luca get slapped? No.

Is Luca naked? Full frontal, but in a disturbing way. Red body paint is involved.

Is Luca gay? Who’s to say?

Is Luca a slut? Please.

Lucameter: 4/100 which is more than the number of his on-screen minutes

Il mondo fino in fondo (2013)

Does Luca smoke? No.

Does Luca sing? No.

Does Luca eat? Briefly; he mostly drinks.

Does Luca get slapped? No, but he gets a fruit thrown at him.

Is Luca naked? He’s never more naked than a T-shirt and underwear, but those fuzzy thighs strike back hard after Waves.

Is Luca gay? He’s married to a woman.

Is Luca a slut? I mean, he’s married but goes to a strip club anyway.

Lucameter: 12/100 though he looks really hot in this movie

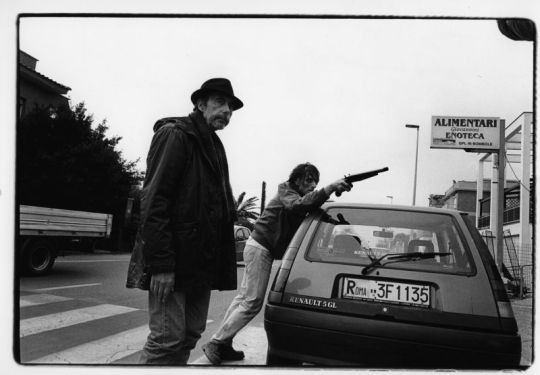

Non essere cattivo (2015)

Does Luca smoke? Yes, a lot, and he does lots of harder stuff.

Does Luca sing? No, but boy does he dance.

Does Luca eat? He briefly chews on something, but he mostly drinks.

Does Luca get slapped? Yes, wonderfully, multiple times, so good.

Is Luca naked? Fully clothed the entire time.

Is Luca gay? He emanates just the most Gay Longing™

Is Luca a slut? Not actually in practice, but the vibe is there.

Lucameter: 86/100 would have been more if he’d had any nude scenes, but that butt in those jeans is very much appreciated

Lo chiamavano Jeeg Robot (2015)

Does Luca smoke? No, he takes care of his body!

Does Luca sing? Only in the best karaoke scene ever committed to screen. And a little in the car with his buddies. It’s wholesome.

Does Luca eat? He gets a whole ball of mozzarella shoved into his mouth. Luca Marinelli... is lactose intolerant.

Does Luca get slapped? No, but he gets sexy scratches on his face, so points for originality.

Is Luca naked? He’s got all the buttons of his shirt undone in one scene, and there’s also like a quarter of the butt.

Is Luca gay? He’s definitely not straight.

Is Luca a slut? He’s a slut for YouTube views and empowering female songs.

Lucameter: 97/100 I was missing The Slap but whatcha gonna do

Die Pfeiler der Macht (2016)

Does Luca smoke? No.

Does Luca sing? No, but he dances sluttily.

Does Luca eat? Yes, though all the food in this movie looks disgusting.

Does Luca get slapped? Very hard.

Is Luca naked? Not as naked as he should be considering the everything about him.

Is Luca gay? He fucks everything in this movie.

Is Luca a slut? He fucks everything in this movie.

Lucameter: 64/100 weak

Slam - Tutto per una ragazza (2016)

Does Luca smoke? Yes.

Does Luca sing? No.

Does Luca eat? No.

Does Luca get slapped? No.

Is Luca naked? He gives us a full butt moment.

Is Luca gay? Not in the slightest.

Is Luca a slut? Definitely, but it all happens off screen somewhere.

Lucameter: 34/100 the butt is doing all the work here

Il padre d'Italia (2017)

Does Luca smoke? Yes, a lot.

Does Luca sing? Yes, and he dances while singing!

Does Luca eat? No, but he drinks champagne like a fancy bitch.

Does Luca get slapped? Yes, by life.

Is Luca naked? We get everything in the first five minutes. Everything.

Is Luca gay? Yes, canonically and explicitly.

Is Luca a slut? No, he’s full of gay sin and self-loathing.

Lucameter: 99/100 glorious

Lasciati andare (2017)

Does Luca smoke? No.

Does Luca sing? No.

Does Luca eat? No.

Does Luca get slapped? He doesn’t have time for anything else but he always has time to get slapped.

Is Luca naked? Not in the slightest.

Is Luca gay? He just wants to be loved T__T

Is Luca a slut? The virgin vibes are stronger than in the Bible movie.

Lucameter: 8/100 it didn’t have to be this way

Una questione privata (2017)

Does Luca smoke? This movie is covered in smoke from Milton’s cigarettes. Seriously, he smokes all the time. Including the scene where he gets called ugly.

Does Luca sing? No, not even in the scene where he gets called ugly.

Does Luca eat? He drinks an egg, though not in the scene where he gets called ugly.

Does Luca get slapped? No. He gets called ugly, though.

Is Luca naked? No.

Is Luca gay? Strong bisexual vibes from this one.

Is Luca a slut? Again, major virgin energy.

Lucameter: 17/100 can you imagine they had the audacity to call him ugly???

Fabrizio De André - Principe libero (2018)

Does Luca smoke? In every scene. Every. Single. One.

Does Luca sing? Duh, while playing the guitar.

Does Luca eat? Yes.

Does Luca get slapped? No, everybody is soft for Fabrizio.

Is Luca naked? He’s wearing nothing but a bath towel for a whole scene.

Is Luca gay? He’s very much into ladies, although he’s got sizzling chemistry with every male character.

Is Luca a slut? He’s very into ladies.

Lucameter: 94/100 almost perfect

Trust (2018)

(it’s not a movie, but Primo is so iconic I can’t and shan’t leave him out)

Does Luca smoke? It’s the 70s and Italy, come on.

Does Luca sing? Unfortunately, he doesn’t, but he’s one hell of a dancer.

Does Luca eat? Munches on spaghetti like there’s no tomorrow.

Does Luca get slapped? Yes. And he doesn’t forget it.

Is Luca naked? Sadly no, but man does the camera love his butt hugged tightly by those slutty 1970s pants. Also balls. Just... just balls.

Is Luca gay? We don’t know for sure, but his whole vibe is kinda the exact opposite of heterosexuality.

Is Luca a slut? For money and power.

Lucameter: 82/100 would benefit from like a karaoke scene or something

Ricordi? (2018)

Does Luca smoke? No.

Does Luca sing? No.

Does Luca eat? Yes.

Does Luca get slapped? No.

Is Luca naked? Oh yes. And he fuuuuuuuuuuucks.

Is Luca gay? This relationship is so heterosexual the couple are literally called Him and Her.

Is Luca a slut? He fucks a lot, but somehow in a very unslutty way. He’s mostly just sad.

Lucameter: 51/100 and he’s called ugly again???

Martin Eden (2019)

Does Luca smoke? Yes.

Does Luca sing? Amazingly, yes, very softly. He also dances.

Does Luca eat? Yep.

Does Luca get slapped? Finally the slappee has become the slapper.

Is Luca naked? Man, I wish. He doesn’t even take his shirt off like wtf dude what did you build all that bigness for???

Is Luca gay? No, and I think he’d be happier if he were.

Is Luca a slut? No, and again, I think it’d have served him better to be a slut.

Lucameter: 62/100 it’s a fine movie that would’ve benefited from more trademark Luca stuff okay

The Old Guard (2020)

Does Luca smoke? No.

Does Luca sing? No.

Does Luca eat? Briefly.

Does Luca get slapped? A lot of violence happens in this movie, but not a single slap, ridiculous.

Is Luca naked? Shirtless, with a close-up on the nipple.

Is Luca gay? Oh, I don’t know, does being one half of the most wholesome and perfect gay couple count?

Is Luca a slut? How dare you. He’s been happily married for 900 years.

Lucameter: 25/100 none of Luca’s trademarks are present but the epicness of his immortal marriage warms me when I shiver in cold

#luca marinelli#the old guard#martin eden#ricordi?#trust fx#fabrizio de andré - principe libero#una questione privata#lasciati andare#il padre d'italia#slam - tutto per una ragazza#die pfeiler der macht#lo chiamavano jeeg robot#non essere cattivo#il mondo fino in fondo#la grande bellezza#maria di nazaret#tutti i santi giorni#nina#waves#l'ultimo terrestre#la solitudine dei numeri primi

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

SO YALL SAW MY MAN MADE DINOSAUR POST DID YA!?!?! WELL LETS TALK REAL DINOSAURS NOW!!! BTW TALK TO ME ABOUT DINOSAURS AND STUFF

Jurassic park, walking with dinosaurs, national geographic, Disney's dinosaur, land before time and rather old dinosaur books got me into loving these long gone bird bois and girls as well as their reptile flying and swimming friends.

Even now when I see the brachiosaurus scene and hear that music welling up I get the shakes and get tears in my eyes!

Then there's good old Roberta the tyrannosaurus. Ya her name was roberta not Rexy. However you could call her both that always works. A stunning icon for the species.

Then we come to jurassic park 3 the infamous child of the series. Loved this film despite its issues. What made me love it was its monster dinosaur, the spinosaurus

I wanna jump now to fallen kingdom my least favorite of the jurassic park story. The reason was...well the dock scene. I don't wanna elaborate you know what I speak of...*crying*. However thats not what I wanna talk about. When our human clone Maisie released the dinosaurs from a terrible fate I internally cheered. If the dinosaurs HAVE to go extinct again let them go under the stars or the sun. Not in a gas filled chamber. She did the right thing.

When I watch walking with dinosaurs I still cry like a baby at episode 4 and 6. This documentary series didn't pull any punches and it was the first time I cried towards any form of media

National geographic always has awsome dinosaur art I would just marvel at. Even paleoart in general. The amount of work and time making them is amazing and I wish I saved those pages and framed them. I gotta find the artists

Despite Disney's dinosaur having issues like all forms of historical media it was still a overall good story. The carnotaurs introduced me to the bull and I love the design. Hell I even have a figure of it in my bedroom besides PJ'S king Kongs vestatasaurus Rex

Need I say anything about land before time? Actually there is one. Sara was always an arse and I never liked her. Petrey, Ducky, and Spike were always my favorites. Spike probably made be a Foodie. Thanks alot you loveable dumb stegosaurus

I don't remember the book series but they came in three HUGE binders of books. I think it was the entire series all showing 1980s style of dinosaurs and so on. Crap I gotta remember what they were.

And then there's deadsounds magnum opus. Dinosauria. A *to my knowledge* 5 episode series of dinosaur stories he himself has animated and created by himself. So far two episodes have been shown and both are heart wrenching and beautiful examples of paleomedia. And darn it why can't I have more images!?!?

And truth be told I can't truly pick favorites. I love them all and I'm so hecking sad their extinct. (I am aware birds are dinosaurs bur you know what I mean). They didn't die of by changes in environment that was naturally made by the planet. They didn't change into new things because of the planet. They died because a hunk of space rock from nowhere came crashing in a screwed everything up. Nature didn't select them to die MALCOLM space was just an asshole and stuff happened.

If I could I'd defiantly do what Hammond did and bring them back in some kind of form. I understand the impacts on nature it'll do, what it could do to the dinosaurs, and humans in general. However with enough time, multiple voices, many form of expertise from many groups of people, and cooperation it can be done. We can bring back extinct species. Perhaps not perfectly like they were but close enough to where they can survive in this world and we can deal with new neighbour's. It can be done.

I would love to see another spin off of jurassic park where we see the lives of animal handlers and caretakers in the various parks. So the scene I would love to see most of is where a cartaker is calling to a triceratops by name and in a rampant calling/screaming said triceratops comes charging towards their handler not in violence but "OH MY GOD MOM!!! YOUR BACK!!!" Kinda like how you'd see handlers interact with large animals they cared for deeply. Or something similar to that. Jurassic park and it's story dosnr always have to be "AAHHH DINOSAURS ARE MONSTERS AND ATE MY HANDS". I would love to see more wholesome moments. More animal moments if you will.

What really sucks abour dinosaurs is that we will never know the full category. Ever. This was explained by kurzgesagt that there's an unkown unkown zone in biological history. This was caused by scavengers, natural events, acidic earth in jungles and so on. So there could have been some really crazy animals out there that we will never again see or know about. Hell perhaps even dragons or something that can be called a dragon could have existed.

youtube

Honestly I love them all. Even those that arnt dinosaurs by definition such as aquatic and air based reptiles. I love them all and I'm so sad their gone, mocked, and everything else that's negative. Hell eveey extinct animal I'm sad about. All of them. Even the giant sea scorpions and so on.

Also youtube, why are there so many dumb children's toy dinosaur videos. What the heck how do I fix this shit?

#wholesome#dinosaurs#i love dinosaurs#writing stuff#writing#stuff#talk to me#talking#i love animals#jurassic park#walking with dinosaurs#disneys dinosaur#national geographic#Roberta#land before time#spinosaurus#brachiosaurus#Youtube

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Points of view – The Interview: Luca Marinelli

How do you approach your characters.

Sometimes I also wonder how I get to the character. For “Non essere cattivo”, I had a very detailed script and a fascinating director at my disposal, so I didn't struggle to relate. It was a very brave script for the way it dealt with reality. At first my auditions went in the direction of Vittorio's character but also knowing the figure of Cesare, more than once I thought I would like to play him. I saw the auditions of others and I stopped to think how I could have done Cesare. Then at a certain point I remember that Claudio looked at Valerio and told him that it would be better to reverse the roles, to let me try Cesare, and so it went. When I read the script of “Lo chiamavano Jeeg Robot”, the first thing that struck me, besides the courageous imagination, was to understand how a film of this kind could be made.

In the first part of your career, you brought an image of introverted and staid youth to the screen. Was this a choice.

Absolutely not. Or rather yes, it was the choice of those who met me first. Perhaps a part of my personality has been seen that could best marry the characters in question. It happened both in “La solitudine dei numeri primi” by Saverio Costanzo and later with Virzì in "Tutti i santi giorni", then it can be said that with Casare of “Non essere cattivo” and the Zingaro of “Lo chiamavano Jeeg Robot” I was allowed to turn things around slightly, to play a character who had a disposition and behavior that was completely the opposite of what I had faced previously.

What do you remember about your debut with Saverio Costanzo.

He was my initiation into cinema, I came from the Academy and I had no idea what it was like to work on a set. The best memory, in addition to the experience of the film with him and Alba, is the first meeting, the first audition, where I really understood that I strongly wanted to work with him and that if this had happened I would have ended up in the hands of a great author.

With that film you found yourself in the main competition of the Venice Film Festival. What memories do you have of that first time at the lido.

Of a huge confusion and a big headache. We were tossed around from one interview to another and not only that, because the worst thing was always answering the same questions, and I was terribly worried not to make the situation even more boring for the machine operator, who never changed, and I don't think could take it longer to hear the same phrases over and over. Fortunately, Alba was there as well and saved me in more than one interview. The experience helped me because the following times I knew slightly more what I was going through and how to manage situations and keep stress at bay. Or maybe not yet, it's a long way.

I noticed that when you talk about your job you do it using the verb “to play” (giocare). Is it a coincidence or the choice has a precise meaning.

Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that in English the term recite is said precisely in this way because in my opinion to play, or the French jouez, represents the feeling of freedom and fun that is inherent in the job I do, better. As far as I'm concerned, the moment of the take is when the actor has to stop thinking, abandon worries, to be able to bring out the energy of his character. He has to play with the same seriousness and commitment with which a child does. I remember a piece of advice from Carlo Cecchi on the fact that in acting counts listening and the here and now. Being actively present to oneself and to others at that exact moment.

You have a method for achieving this condition.

If someone asked me something about technique, I wouldn't know what to answer, apart from listening. On the set of Andrea Molaioli's film in which I am the father of the young protagonist, the actor who plays him, Ludovico, who is really good, full of talent and very smart, once asked me what was the technique to make the best of the character, and the only thing I felt able to advise him was to try to be present in that moment and then to let go, listen and not think about the rest.

But I imagine that there are also practical aspects in the preparation that precedes the start of filming.

As for me, I try to prepare as much as I can before arriving on set because at the start of the shoot it would be good to be ready. But not everything happens automatically, in the sense that you can’t always find the character immediately. However, I have always been lucky enough to have more or less long periods of rehearsal before starting a film. I remember this moment with Saverio and Alba, where we spent weeks among us and also with the kids who would have played us as children, to try the various scenes and to create a union and harmony between the characters. The same happened with Paolo Virzì, Thony and I, more than once we gather, facing the script, to clarify all the passages and moments of the scenes.

And how did things go with Claudio Caligari.

The same thing also happened with Claudio even though the illness made everything more complicated for him. He asked us to change our bodies, to participate in the auditions of the other actors. This allowed all of us, the cast, to integrate and develop a unity of purpose and a truly rare familiarity. So in front of the camera it seemed to me that the gang, to which Cesare and Vittorio belonged, was really part of my life, that it wasn’t hard to pass from Luca to Cesare, because I had found him. And always to identify with the environment of the story, I preferred a house in Ostia, and Alessandro often came to me from Rome to spend time between the two of us. Claudio, in addition to having reading meetings together, also showed us films that were a source of inspiration for him for this film, such as “Accattone” by Pier Paolo Pasolini, “Rocco e i suoi fratelli” by Luchino Visconti and “Mean Sreet” by Martin Scorsese.

Instead, I wanted to ask you what happens between takes, for example when you come home after a day of work. You stay inside the character as it happens to Daniel Day Lewis, or you put it aside and think of something else like Marcello Mastroianni did.

I try to disconnect from the set. I try. I go home and try to do something else, but the last thought before falling asleep always goes to the next day's work plan and I leave myself a few minutes for the memory and concentration useful for tomorrow and then I close my eyes.

We asked Roberta Mattei and we ask you too. During the processing you were aware of the exceptional nature of what you were doing.

Yes. Let me explain: I saw with my own eyes that what was happening was exceptional, a man who was dying wanted to give his latest work to the public, to his audience, to his people, to people. This has no equal for me. Don't think about yourself in such a situation but about others.

Then it was the turn of Lo chiamavano Jeeg Robot.

I shot Jeeg Robot in March 2014, and therefore before “Non essere cattivo”. The fact that Mainetti's film is only coming out now is due to the long post-production period necessary to assemble the shot with the special effects present in the film.

Here as well it was an interpretation and a character who completely overturns the transparent and pristine image of the first part of your career.

To make Jeeg Robot we had to convince each other, Gabriele Mainetti and I, about my success in the character. I pushed him towards a theatricality and Gabriele towards a real madness, a pure pain. In the end, I think we have found the right amount.

The construction of the Zingaro was already very clear in the writing and it was up to us, however, to find its true aspect.

Guiding him is this crazy and boundless ego, and the obsession with having to leave a mark. The Zingaro's eccentricity is partly reflected in his look, halfway between a rock star and a suburban bully. For the costumes and make-up we were inspired by the great rock icons. We dared in some choices, such as the black coat with pink leopard lining that characterize the wardrobe. For the aspects related to the way of performing, his model was Anna Oxa and in particular the video of her at Sanremo, when she sings “Un’emozione da poco”.

In part you have already answered, but I wanted to know how you choose to accept the proposals that are made to you and if you have any foreclosures towards television, or more generally towards commercial cinema.

I choose the proposals on the basis of love at first sight that must happen with the film, with its screenplay. Then figure out who will be leading the film, meet the director. I don't have any kind of foreclosure, let's say that if I don't like something I don't do it and if I like it I do. And it doesn't matter if it's cinema or television.

As a spectator what is the cinema you love.

I like films that have something to say and that I also choose based on who directed and starred in it. Usually when they ask me to name some titles I have a void. Think that the same thing happened to me also during the audition to enter the experimental center, when Lina Wertmuller asked me the title of a film I had seen recently. I was struck by a cosmic void and instead of naming her an authoritative and important film I left her stunned by citing Batman, I think Nolan's first, still a good film, but I still had Wertmuller in front of me... But to go back to what you asked me, I tell you that in general I always like to watch films that come from Sundance, of which I remember, for example “Like Crazy”, which I found disarmingly beautiful, the films of P.T. Anderson, Wes Anderson, the Cohen, there are many, and among the Italians those played by Alba Rohrwacher, Valerio Mastandrea, Elio Germano, Kim Rossi Stuart and directed by Alice Rohrwacher, Costanzo, Virzì, Sorrentino, Garrone, Salvatores. Without forgetting those of the great Joaquin Phoenix. But in reality I look at everything, let's say that I try not to lose anything of these.

Despite the certificates of esteem you have received for your performances, the impression is that of an understatement that almost seems not to be aware of what you have achieved so far as an actor.

Whenever I see a film of mine I always think there is something I could have done better. But basically I'm happy with what I've done so far. Having said that, I think that the films alone should be enough to explain everything and that the interviews don’t add anything new to what there was to say before making them. But when I am in the dance, when I need to promote, I am committed to doing it in the best possible way. I strongly think that in life and at work it’s important to demonstrate that you know how to do and not to show at all costs that you do.

DREAMINGCINEMA

Just wanted to translate this old interview for the non-italian’s fans ^^ (sorry for my English)

#Luca Marinelli#interview#english translation#mine#english#non essere cattivo#lo chiamavano jeeg robot#slam tutto per una ragazza#la solitudine dei numeri primi#Tutti i santi giorni#actor#cinema#film

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tip Top Tap: Great Tap Performances in Film By Constance Cherise

In my opinion, there is no conversation surrounding classic musical tap dancing in film without including the likes of the Nicholas Brothers, Fred Astaire or Gene Kelly. Over the years, there have been countless memorable dance scenes, and in compiling a list of the routines I felt were exceptional, I wanted to search further than my initial go-to's. Here, in no certain order are my not so obvious choices of remarkable classic musical tap-dancing performances.

The Nicholas Brothers: “Jumpin’ Jive” – STORMY WEATHER (‘43)

They are the incomparable Nicholas Brothers. Their bodies act like boneless structures, they leap through the air defying gravity and land in splits, consecutively. Just when you think the dance cannot get any better, they move to the next set, where the finale is literally and figuratively unbelievable. This is why Fred Astaire called this performance, “The best ever put on film.” If this is your first time seeing this sequence, I can assure you it will leave you shaking your head in pure amazement. Baryshnikov, Balanchine, Astaire and Kelly, were humble fans of the Nicholas Brothers, and all were in awe of their capabilities. Not only is this performance astonishing, according to the brothers, it was unrehearsed and executed in one take.

Judy Garland and Gene Kelly: “Barn Dance” – SUMMER STOCK (‘50)

Gene Kelly and Judy Garland...pure chemistry. This is not Kelly and Garland’s first dance number together. In fact, during their MGM career, they co-starred in THE PIRATE (’48) and FOR ME AND MY GAL (’42). Kelly is his normal effervescent self, performing his discipline in grounded masculinity. Garland, who did not arrive at MGM as a professionally trained tap dancer, matches Kelly move for move until Kelly performs his signature airplane twirl. Although Garland is the healthiest we've seen her in years at the point of this picture—as she recently completed a stent in a detoxification facility (note the measurable difference in her weight by the end of the film in the musical number “Get Happy”)—she remains as light as a feather. “Barn Dance” is a joyful, exuberant number and is reflective in the expression on their faces. SUMMER STOCK would be Garland's last film with MGM. It’s a fitting circumstance that Kelly would become Garland's final partner, as eight years earlier, Garland welcomed and mentored Kelly in his first film, FOR ME AND MY GAL, a facet of their friendship he would always remember.

Gene Kelly: “I Like Myself” – IT’S ALWAYS FAIR WEATHER (‘55)

As if his SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN (‘52) icon status, Hollywood good looks, voice and choreography skills weren't enough, Gene Kelly performs in a pair of roller skates in IT'S ALWAYS FAIR WEATHER (‘55) and once again proves his genius. But, he doesn’t just roller skate. He performs with the precision and grace of a professional ice skater. No stunt doubles here, this is all Kelly (he did the majority of his own stunts). His performance is flawlessly intricate, and for Kelly, it seems as natural as walking. When he breaks into tap dancing, performing time steps and heel clicks, you start to wonder what can't he do? Twenty-five years later and with just as much stability, he would once again don a pair of skates while performing in the cult classic fantasy film XANADU (‘80).

Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly: “The Babbitt and the Bromide” – ZIEGFELD FOLLIES (‘45)

This is the first time Kelly and Astaire dance together on film (they would not dance together again until THAT'S ENTERTAINMENT, PART II, [‘76]). It is a clever vaudevillian-style number, allowing exactly enough time to showcase each performer's attributes, amusingly injecting instigation, to highlight their professional rivalry, concluding in an energetic finale. It is an excellent visual example of distinguishing their unique technique. Each is certainly at their best given their status and subsequent comparison. However, those who are true classic musical fans understand Kelly and Astaire cannot be compared. Although their dance styles are different, they are also equally extraordinary. Kelly's athleticism in juxtaposition to Astaire’s delicacy is perfectly matched.

Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers: “I’ll Be Hard to Handle” – ROBERTA (‘35)

The pairing of Astaire and Rogers was destiny. This particular number was performed live: live music, live tap dancing, with no cuts and done in one take. If you listen closely, you can even hear Rogers’ giggle. It seems as if they casually blend into the dance, but of course we know this is not the case. At times, their movements are deliberately delayed and at others, they are kinetic. Midway, the two have an argumentative exchange exclusively through tap dancing. Rogers echoes Astaire tap for tap and their symbiosis is apparent. It is a lighthearted and carefree number, and as with all Rogers and Astaire performances, absolutely delightful.

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson: Stair Dance

Best known for his successful pairings with Shirley Temple, of which both were sincerely fond of each other, here he performs his famous stair dance. Bill “Bojangles” Robinson honed his craft from childhood, which eventually led him to become one of the first African American’s to appear in vaudeville without blackface and as a solo performer. Here, he uses his hands and his feet before climbing the steps, as if testing them to see if they are worthy enough to withstand his elegantly polished footwork. He continues to elaborate each pattern in growing confidence. His feet remain low, and at times it seems that he is standing still. Every tap is clean and sharp as each stair resonates with a different note. Robinson's genius is in creating a performance that is technically complex and elaborate, that appears as if it were commonly effortless.

#Tap dancing#old hollywood#classic film#musicals#nicholas brothers#Gene Kelly#Judy Garland#Fred Astaire#Ginger Rogers#Bill Bojangles Robinson#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Constance Cherise

366 notes

·

View notes

Text

gifs and ships

I was tagged by @pichitinha to describe my ships using gifs!

1. First Ship - Ana / Danilo (Chocolate com Pimenta)

soap operas are a huge thing here in Brazil (the mexican ones were my favorites! they’re a classic around here if you are keen to drama). but the first couple I remember rooting for is from a brazillian one. they had a lot of winning tropes: angst, slow burn (kinda), they had a son and she didn’t tell him.... yep, that’s good lol

2. First OTP - Diego / Roberta (Rebelde)

remember when I told you mexican soap operas were dramatic? well... Rebelde had three seasons (with more than 100 episode... EACH), so you can imagine how much drama and slow burn I had to put up with lol

the soap opera and the band (RBD, if you don’t know) were the first things I can remember being truly a fan. I still love them (the band split up almost 13 years ago and the original airing of rebelde ended back in 2006). roberta and diego are the definition of enemies to lovers (and back to enemies... and then to lovers once again haha). they were pure chaotic energy, I love it! it’s one of my fav ships ever and it’ll always be ♥

3. Current fav ship - Betty / Jughead (Riverdale)

bughead exes to lovers 2021 let’s goooooo!!! they are truly iconic. imagine not shipping this excellence? cannot relate *inserts shrug emoji here*

(ps: this kiss is one of the hottest things I’ve ever seen... better than a lot of sex scenes we’ve seen in this show hehe)

4. Your Ship Since the First Minute - Alex / Piper (OITNB)

I didn’t even know what lovers to enemies to lovers was but those lesbos gave me everything I didn’t even knew I needed lol (I didn’t even finish oitnb but they always be one of my wlw ships)

5. You Wish They Had Been Endgame - Simon / Alisha (Misfits)

this one will ALWAYS bring me pain. ugh. so good and so sad! a broody/emo boy + bad girl? yes sign me up.

(also house/cuddy from house m.d)

6. You Wish They Had Been Canon - Draco / Hermione (Harry Potter) AND Rachel / Santana (Glee)

JK had the opportunity to give us one of the most iconic enemies to lovers couples ever and fucked it up so yep...... hp canon story? (keke palmer’s voice) he could be walking down the street, I wouldn’t know a thing.

faberry who? please, pezberry had THE enemies to lovers feat. hate fuck energy we deserved to see. no I don’t make the rules and yes you are wrong if you don’t ship them.

7. Most of the Fandom Hates, but You Love - Finn / Rachel (Glee)

this one is so close to my heart! I didn’t even finish glee because it became a shit show and I couldn’t watch after Cory’s passing, but finn and rachel were IT for me since day 1. ALL of my friends hated finchel on twitter bc they shipped faberry, but here on tumblr, I found so many artists that gave me tons of gifs and fanfics hehe

8. You Don’t Even Watch the Show, but You Ship Them Anyways - Clarke / Lexa (The 100)

yep.

9. You Wish They Had a Different Storyline - Callie / Arizona (Grey’s Anatomy)

the cheating storyline was the beginning of the end for me, they destroyed a PERFECT ship. I still don’t accept that. justice for may babies (they are kinda [?] endgame but the writers did them SO DIRTY!)

10. Fav Ship That is Endgame - Chuck / Blair (Gossip Girl)

iconic shit right here, I don’t even need to explain.

tagging @feisty-aquarius4, @dreamingofbughead, @aresaphrodites, @courtaa, @stonerbughead and whoever wants to participate! (@pichitinha if you want to make a book edition with gifs or maybe fanarts... so I’m tagging you again! haha)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Radix Dance Convention, Atlanta, GA: RESULTS

High Scores by Age:

Rookie Solo

1st: MIla Simunic-’Never Enough’

2nd: Brenna Ferrell-’Showstopper’

2nd: Alaina Chadbourne-’Walk The Dinosaur’

Mini Solo

1st: Ellie Melchior-’Function’

2nd: Barrett Robison-’Ping’

3rd: Spencer Parnell-’The Return’

3rd: AnaKate Danner-’Unleashed’

3rd: Paislyn Schroeder-’Vibin’

4th: Kaylee Schwamb-’See Me Now’

4th: Lily Planck-’She’s A Lady’

5th: Georgia Beth Peters-’Come Together’

5th: Ava Grace Merritt-’Love Me’

5th: Anslee LeBlanc-’Take Care Of Yourself’

6th: Bella Smith-’Against The Music’

6th: Clare Gibbons-’Baby I’m A Star’

7th: Xin Lee-’Finding Home’

7th: Avery St John-’Tomorrow’s Song’

8th: Londyn Knox-’Without You’

9th: Lauren Fenton-’Boogie Shoes’

9th: Madelyn Laken-’Surprise’

10th: Penelope Thomas-’Love Shack’

10th: Lila Morath-’Miss Velour’

Junior Solo

1st: Amaya Llewellyn-’Must’

1st: Leila Winker-’Takt’

2nd: Emme James Anderson-’Resume’

3rd: Riley Fiorello-’Crippled Bird’

3rd: Estella Guzman-’No Contamination’

3rd: Ally Reuter-’Stagma’

4th: Mia Doyle-’Designated Harmony’

4th: Brinkley Pittman-’Gravity’

4th: Addison Cullather-’Tangent’

5th: Morgan Belyeu-’Older’

5th: Kalli Ramet-’Rock Me Baby’

5th: Roberta Marcos-’Torn’

6th: Luna Powell-’1977′

6th: Ella Paige Moore-’Breaking Point’

6th: Zella Wentz-’Fearless’

7th: Addison ?-’How Does A Moment Last Forever’

7th: Collier McLain-’Love Has No Limits’

7th: Mia Mondok-’Music Box’

7th: Gabriela Miller-’Sinking’

8th: Mia Narvaez-’Destinations’

8th: Amanda Fenton-’Devil In Disguise’

8th: Annabel Ellis-’The Forest’

8th: Sidney Hill-’The Moon’

9th: Zoe Kappler-’Changeling’

9th: Callie Ludtke-’Impossible’

9th: Leah Midgett-’Mirror Mirror’

10th: Kinley Andrews-’All That Jazz’

10th: Meredith Lee-’Especially A Woman’

Teen Solo

1st: Harlow Ganz-’End of Love’

1st: Preslie Rosamond-’Possibly Maybe’

2nd: Emery Sousley-’Birds of Paradise’

3rd: Olivia Taylor-’Closure’

3rd: Oliver Keane-’Electric Pulse’

4th: Kenzie Robertson-’1977′

4th: Josh Stephens-’Fires’

4th: Johanna Jessen-’Party’

4th: Gabriella Kennedy-’Ritz’

4th: Rianna Weck-’Sensory Overload’

5th: Delaney Lorenz-’Creep’

5th: Haley Midgett-’Smile to Me’

5th: Sydney Tam-’Touch’

6th: Natalie Bumgarner-’Maybe This Time’

6th: Kate Higginbotham-’Polly’

7th: Kennedi Washington-’Epilogue’

7th: Kayla Pierce-’Fire Speak’

7th: Kayla Montgomery-’Lalia’

8th: Cady Cropper-’Godspeed’

8th: Maddie Laine Callaway-’Piece by Piece’

9th: Mia Lott-’Flawless’

9th: Jordan Stevener-’Ghosts’

9th: Ally Organo-’Like You’ll Never See Me Again’

10th: Julia Deana-’Hate You’

10th: Madison marshall-’Icon’

10th: Dempsey Foxson-’Vain’

Senior Solo

1st: Seth Gibson-’Identity’

1st: Dai Boyd-’Try A Little Tenderness’

2nd: Libby Wiley-’By Thy Light’

3rd: Brittany Willard-’Unchained Melody’

4th: Raven Rutledge-’A Pale’

5th: Rebecca Lewyn-’Devil I Know’

5th: Anna Goodman-’Fallen Alien’

5th: Alexandra Jinglov-’Take It Easy’

6th: Belle Mason-’Drones’

6th: Katelynn Midgett-’Georgia’

6th: Ayana Davis-’Progressing’

7th: Kaili Tam-’Malamente’

7th: Elaina Samady-’Loving Ghosts’

7th: Ally Pereira-’Daring to Love’

7th: CJ Parker-’A Letter From France’

7th: Madison Phelps-’A Feeling Felt’

7th: Avery Ferguson-’When You Sleep’

8th: Izzie Bringle-’Hush’

8th: Molly Fisher-’Moved’

8th: Lexi Elias-’The Weight’

9th: Gracie Avalos-’A Body’

9th: Kirsten Brown-’Asylum’

9th: Julia Hale-’Cellophane’

10th: Brooke Manchester-’Go’

10th: Ainsley Wharton-’These hands’

10th: Sophie Hooker-’We’ll Meet Again’

Mini Duo/Trio

1st: Academy for The Performing Arts-’Fall For You’

2nd: Milele Academy-’Miami’

3rd: Studio 413-’Party Planners’

3rd: Milele Academy-’Vibology’

Junior Duo/Trio

1st: Milele Academy-’Fiyah Speak’

1st: Academy for the Performing Arts-’Oceania’

2nd: B-viBe The Dance Movement-’The Mess We’re In’

3rd: Dance Productions Unlimited-’Superpowers’

Teen Duo/Trio

1st: The Royal Dance Academy-’Greiving’

2nd: Milele Academy-’Down We Go’

2nd: Accolades Movement Project-’I Remember Her’

3rd: Studio 413-’Distortion’

3rd: Academy for the Performing Arts-’Fledglings’

3rd: Academy for the Performing Arts-’Rebuild’

3rd: Academy for the Performing Arts-’Tiny Cities’

Senior Duo/Trio

1st: Studio 413-’Black Flies’

2nd: Milele Academy-’Darkest Hour’

3rd: B-viBe The Dance Movement-’Heartbeat’

Rookie Group

1st: Elite Studio-’I Don’t Want to Show Off’

2nd: Elite Studios-’90′s Babies’

Mini Group

1st: Encore Studio-’Uptown Girl’

2nd: Encore Studio-’Windowdipper’

3rd: Encore Studio-’Turn to Stone’

Junior Group

1st: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’All I Want’

1st: B-viBe The Dance Movement-’Down The Line’

1st: B-viBe The Dance Movement-’History In The Making’

2nd: Milele Academy-’Save a Horse’

3rd: Elite Studio-’Collective Breath’

Teen Group

1st: Academy for the Performing Arts-’Don’t Forget Me’

1st: Encore Studio-’Kinjabang’

2nd: Studio 413-’Social Media Overload’

3rd: Milele Academy-’Close Up’

Senior Group

1st: Elite Studios-’I Still Remain’

2nd: Milele Academy-’Get It’

3rd: Academy for the Performing Arts-’Holdin Out’

Rookie Line

1st: Encore Studio-’Conga’

Mini Line

1st: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Jailhouse Rock’

2nd: Encore Studio-’Truth’

3rd: Elite Studio-’Get Busy’

3rd: Elite Studios-’What You Did To Me’

Junior Line

1st: Milele Academy-’Missy’

2nd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’It’s About That Walk’

3rd: Studio 413-’Into the Night’

Teen Line

1st: Studio 413-’Hold On Tight’

2nd: Encore Studio-’Yikes’

3rd: Encore Studio-’Just Say’

Senior Line

1st: Studio 413-’Rumors’

2nd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Lost’

3rd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Who You Are’

Mini Extended Line

1st: Encore Studio-’Vibeology’

2nd: Studio 413-’Critical Level’

3rd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’I’m Alive’

Junior Extended Line

1st: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Covergirl’

1st: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Footloose’

1st: Studio 413-’Goodbye’

2nd: Studio 413-’Girl Boss’

Teen Extended Line

1st: Studio 413-’No One’

2nd: Studio Powers-’BLACK’

3rd: Studio 413-’Ready or Not’

Senior Extended Line

1st: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Shut It Down’

2nd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Trust Me Again’

3rd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Resolution’

Junior Production

1st: Studio 413-’Electricity’

Teen Production

1st: Encore Studio-’Cardi’

2nd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’JLo’

3rd: Elite Studio-’That 70′s Show’

High Scores by Performance Division:

Rookie Jazz

1st: Encore Studio-’Conga’

2nd: Elite Studio-’I Don’t Want to Show Off’

Rookie Tap

Elite Studios-’90′s Babies’

Mini Jazz

1st: Encore Studio-’Uptown Girl’

2nd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Jailhouse Rock’

3rd: Milele Academy-’Move Your Body’

Mini Hip-Hop

Studio 413-’Lose Control’

Mini Tap

Studio 413-’Critical Level’

Mini Contemporary

1st: Encore Studio-’Windowdipper’

2nd: Encore Studio-’Turn to Stone’

3rd: Encore Studio-’Truth’

Mini Lyrical

1st: Elite Studios-’Every Single Thing I Have’

2nd: Vermont Ballet Theater-’Build It Up’

Mini Specialty

Jill’s Studio of Dance-’I’m Alive’

Junior Jazz

1st: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Covergirl’

2nd: Studio 413-’Electricity’

3rd: Milele Academy-’Save a Horse’

3rd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’It’s About That Walk’

Junior Hip-Hop

1st: Milele Academy-’Missy’

2nd: Studio 413-’Girl Boss’

3rd: Academy for the Performing Arts-’New Skool’

Junior Tap

1st: Studio 413-’Into the Night’

2nd: Academy for the Performing Arts-’You Can Feel It’

Junior Contemporary

1st: Studio 413-’Goodbye’

2nd: B-viBe The Dance Movement-’Down The Line’

3rd: Elite Studio-’Collective Breath’

Junior Lyrical

Jill’s Studio of Dance-’All I Want’

Junior Musical Theatre

1st: Academy for the Performing Arts-’Guns and Ships’

2nd: Vermont Ballet Theater-’We Go Together’

Junior Specialty

1st: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Footloose’

2nd: B-viBe The Dance Movement-’History In The Making’

Teen Jazz

1st: Encore Studio-’Just Say’

2nd: Studio 413-’Body Language’

3rd: Studio 413-’Social Media Overload’

Teen Hip-Hop

1st: Encore Studio-’Yikes’

2nd: Studio Powers-’BLACK’

3rd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Fire Emoji’

Teen Tap

1st: Studio 413-’No One’

2nd: Encore Studio-’Cardi’

Teen Contemporary

1st: Studio 413-’Hold on Tight’

2nd: Encore Studio-’Kinjabang’

2nd: Academy for the Performing Arts-’Don’t Forget Me’

2nd: Encore Studio-’Sadness’

3rd: Milele Academy-’Hurting You���

Teen Lyrical

Vermont Ballet Theater-’Gravity’

Teen Musical Theatre

1st: Elite Studios-’Take Off With Us’

1st: Academy for the Performing Arts-’Wait For Me’

Teen Specialty

1st: B-viBe The Dance Movement-’Cage of Bones’

2nd: Studio Powers-’Area 51′

Senior Jazz

1st: Studio 413-’Rumors’

2nd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Shut It Down’

3rd: Elite Studios-’Sleep’

Senior Hip-Hop

Academy for the Performing Arts-’Welcome to Our Hood’

Senior Tap

Academy for the Performing Arts-’Holdin’ Out’

Senior Contemporary

1st: Elite Studios-’I Still Remain’

2nd: Milele Academy-’Get It’

2nd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Lost’

3rd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Who You Are’

3rd: Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Trust Me Again’

Senior Lyrical

1st: Elite Studios-’Kissing You’

2nd: B-viBe The Dance Movement-’Came Here For Love’

Senior Specialty

1st: Academy for the Performing Arts-’Still Smiling’

2nd: B-viBe The Dance Movement-’For This You Were Born’

Best of Radix:

Rookie

Elite Studio-’I Don’t Want to Show Off’

Encore Studio-’Conga’

Mini

Milele Academy-’Move Your Body’

Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Jailhouse Rock’

Encore Studio-’Uptown Girl’

Junior

Elite Studio-’Collective Breath’

Milele Academy-’Missy’

B-viBe The Dance Movement-’History In The Making’

Studio 413-’Goodbye’

Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Covergirl’

Teen

Academy for the Performing Arts-’Don’t Forget Me’

Studio 413-’Hold On Tight’

Studio Powers-’BLACK’

Milele Academy-’Hurting You’

Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Fire Emoji’

Encore Studio-’Yikes’

Senior

Milele Academy-’Get It’

Elite Studios-’I Still Remain’

Studio 413-’Rumors’

Academy for the Performing Arts-’Holdin Out’

Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Lost’

Studio Standout:

Elite Studios-’I Still Remain’

Academy for the Performing Arts-’Holdin Out’

B-viBe The Dance Movement-’History In The Making’

Encore Studio-’Yikes’

Jill’s Studio of Dance-’Lost’

Milele Academy-’Get It’

Studio 413-’Hold On Tight’

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

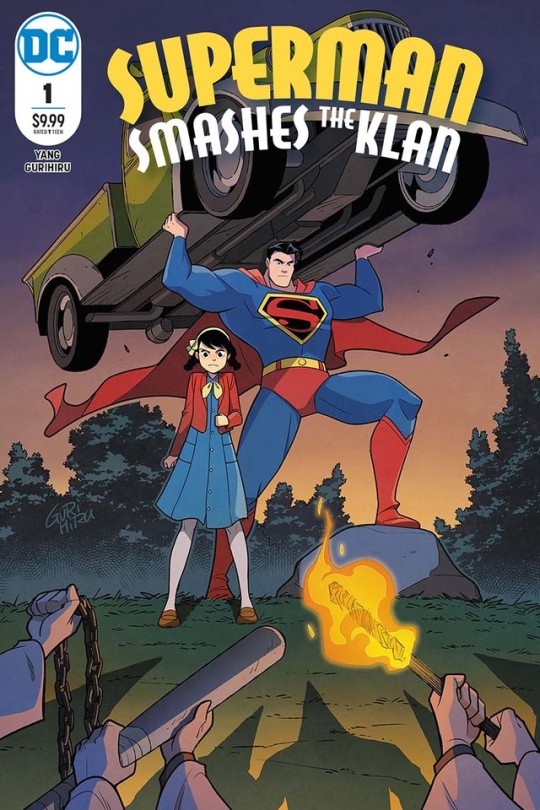

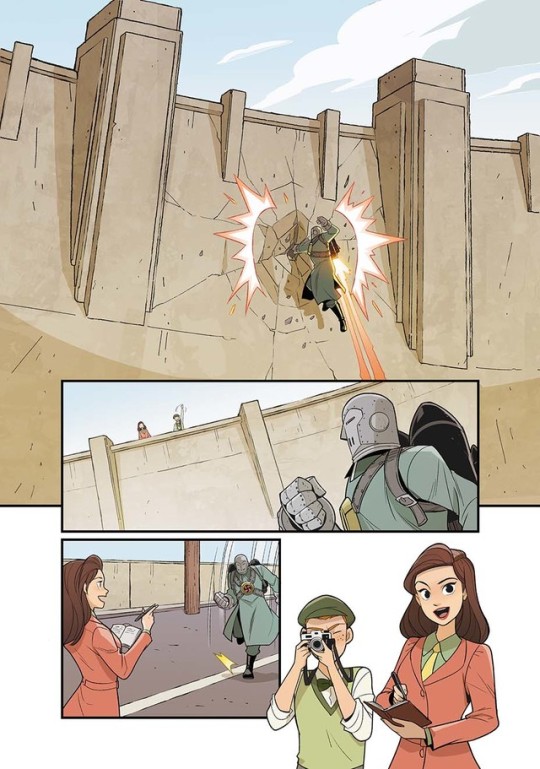

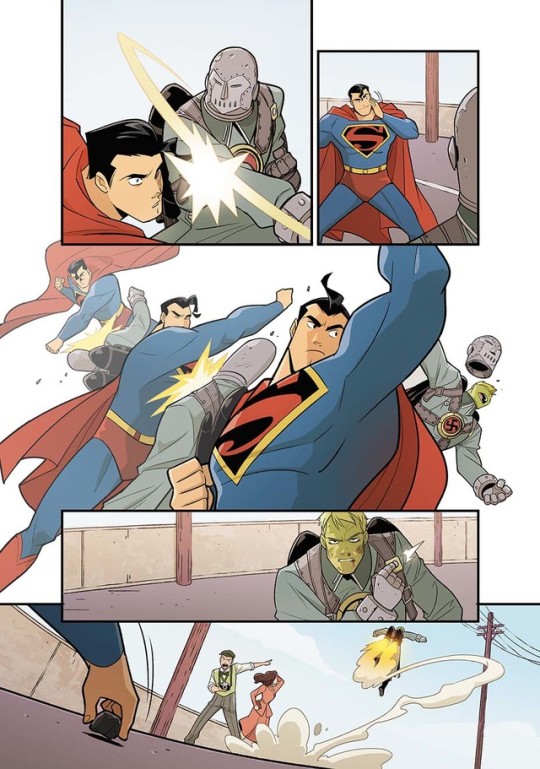

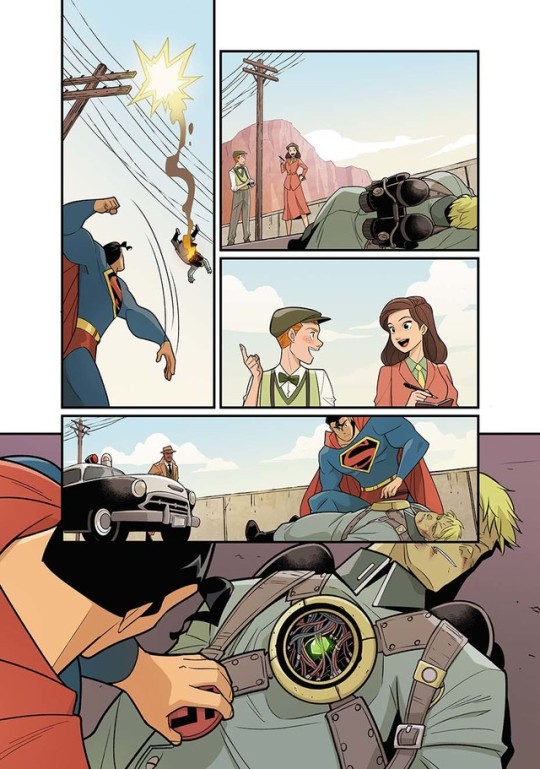

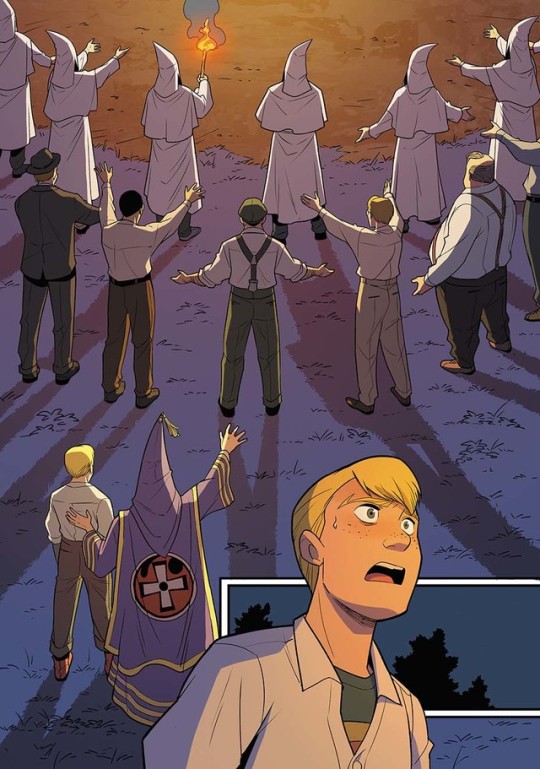

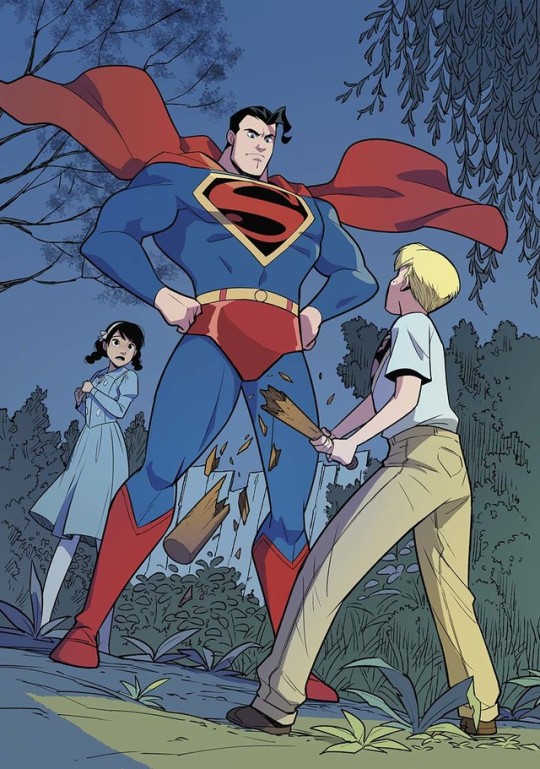

Preview Pages and Interview for SUPERMAN SMASHES THE KLAN

Superman Smashes the Klan launches Oct. 16, with the first of three 80-page perfect bound issues. The collected edition of the story will be released in 2020. DC’s official solicitation for the first issue is below, followed by artwork from the issue.