#russian revolt

Text

Wagner Revolt: Russia's habit under President Valdimir Putin of using mercenary forces in many of its military operations backfired briefly in 2023 with a revolt by Yevgeny Prigozhin.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

(E.)LASKER–SCHÜLER.Sämtliche Gedichte;mit einem nachwort von (U.)WOLF.FISCHER Klassik.2016(2021).Frankfurt am Main.432pp.(Gedichte 1903 bis 1905).p.78: "Vollmond.||Leise schwimmt der Mond durch mein Blüt…|Schlummernde Töne sind die Auge der Tage.|Wandelhin…taumelher…|Ich kann deine Lippen nicht finden.|Wo bist Du ferne Stadt|Mit den segnenden Düften…..|Immer senken sich meine Lider|Ueber die Welt| Alles schläft….|Und hinter dem Mittag beugt sich|Ein alter, traumweißer Wind|Und bläst die Sonne aus.||

#ULiège#Else Lasker–Schüler#poetry#expressionism#Kitchenev pogrom#1904#Russian Revolt#1905#Sibelius#YouTube#Magical_Tales_of_Wolves#Chang#die Brücke#Modigliani

1 note

·

View note

Text

I say this every time I see a voting post on which people have made stupid comments but if you can't get your shit together enough to vote once every two years I absolutely do not think you will ever start, let alone join a revolution, and if one happens despite your lack of efforts I am fairly confident you think that your role in the commune will be to look at me and earnestly tell me that I should be cooking food for you because I'm so much better at it.

#And I want you to know that my role on the commune will be to hit you over the head with a shovel#Like do I personally feel great about the Russian revolution no but at least they revolted instead of whined from behind picrew icons

924 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alexander Ivanovich Morozov - Landscape with trees, 1893.

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

World events :]

#russia#Russia is revolting#russian revolution#russian revolution pt 2 electric boogaloo#world events#war in russia#war in ukraine#supernatural#supernatural meme

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiii king!! What's ur favorite salad? (with the intentions of learning a new salad recipe from an esteemed mutual)

Hiii hi hello heyy ok hear me out!!

This is something I literally made up on the spot mixing random stuff I found in my mom's fridge. It's quinoa, diced carrots and tomatoes, and sliced radish, with salt and olive oil. Idk if it is a favorite but I was surprised that liked it so much!

Also I sometimes get lunch at a self service buffet near my university and the vegetables there aren't super good quality so to make it more enjoyable I just throw some cold fusilli in there and make it a pasta salad. Genuinely upgrades it like magic. Lettuce tomato lentils broccoli and fusilli is my go to. %80 of cold vegetable salads can be improved by adding either avocado or cold pasta this is my wisdom. Add spring onions also

#i could have gone for fancier salads with more unique ingredients#but i wanted to stick with stuff that is simple and i can easily make for myself at home :]#special shout out to tabule and israeli salad and russian potato salad yes I'm jewish how could you tell#also i went into the wikipedia page for salads to see if there were any ones that i didn't remember and deserved a mention#and almost every single one of those looks revolting even a lot of the ones i like#idk if humanity is particularly incapable of taking good photos of salads or if here really are so many gross ones but that page is insane#anyways yeah i hope u like those sunny!! if you have some recepies u like send them my way I'm in a salad craze wooooooo#mutuals

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

i need to get my shit together and adopt a cool and aloof persona where i just speak russian as a ukrainian online and don't feel bad about it. like bad bitch vitaliy kim who keeps running an official ukrainian government telegram channel without avoiding/deleting russian texts he sends

it's really something to need a validation figure for something as stupid as this but here we are i guess. last week had to console my mum because a grown-ass woman was mean to her about it online, only to get sad about it myself today.

it's such an easy target to have on your forehead - today I didn't even speak russian, the exchange was in english, but my transliteration had 1 mistake in it (because of some frankly stupid choices ukraine implemented in 2007-2010 that result in VERY ugly -"ий" transliterations). and the other user decided this meant i was a filthy russophile traitor who did it on purpose to spite ukraine. there are ways to correct people that are in good faith, theirs was not.

physically it caused a, like, panic response, heart pounding feeling like i needed to "absolve" myself in their eyes, defend my worth, prove that i'm still ukrainian - specifically, prove that I speak ukrainian good enough to be ukrainian (i am decently fluent, but it's just not my #1 native language, that's not something I can change). i couldn't even think of anything to say, i just told them that it's hurtful for me that they assumed I was being malicious.

this is a recurring interaction forum so I'm pretty sure they'll just treat me with suspicion forever. what do they want, my birth certificate? my lack of any ties to russia? a manifesto? i said nothing to them to start this, this is all based JUST on the fact that ukrainian is not my #1 first language and it shows sometimes.

if it were just this one user, it'd be whatever, but it's not - i've seen this sentiment in so many places, even down to mocking русский language when that language is not just a российский language but the language of, idk, your neighbours downstairs? your friend's family (even if that friend speaks ukrainian with you)? a huge percentage of people who live east of the dnieper/dnipro river? i dont know. it hurts to see it over and over again and it hurts even more to see my mum get hopelessly sad about this thing she also cannot change in herself.

#i dont want to feel like i'm going to be CLOCKED as a TRAITOR for speaking the language i've always spoken in my home city/country#its horrible to feel like i have to either defend myself or fucking grovel before Proper Ukrainians if i get caught#''getting caught'' shouldnt be a feeling i feel about my native language in my home country and cultural context!#but people are cruel. especially online where the other person is less real to them. and this mostly means other ukrainians to be honest#(russian opinions on this are not so much cruel as they are revolting; they dont hurt though because i dont care about them)#that's what hurts is hearing this from other ukrainians - people who i consider my cultural peers/my земляки#and then to see THEY dont think the same of me and mine for something we didnt get to choose. like a slap in the face#(ironic to see some of these people then argue SO vehemently to defend us in front of russians. would love some of that at home please)#(they dont realise theyre repeating the 'братья меньшие' bullshit only in the other direction -#- we russophone ukrainians are lesser but they'll HAVE us; they're so kind and patient; they'll FIX us to be correct ukrainians. i mean)#personal#ukraine

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is all quite ironic. russian propaganda tried so hard to push the narrative that "russians are fighting against nazi's and fascism," and "russia defeated the nazi's in WW2." And now actual nazi's are on their way to Moscow, with little to no resistance. Where is your fight against the nazi's now?

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nicholas I before the unit formation of the Life Guards of the Sapper Battalion in the courtyard of the Winter Palace on 14 December, 1825 (Decembrist Revolt)

by Vasily Maksutov

#nicholas i#winter palace#courtyard#decembrist revolt#art#history#russia#st petersburg#saint petersburg#russian#emperor#europe#vasily maksutov

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wonder if we can get enough people to tweet to Anonymous or reach out so they can help Russian Indigenous like they are helping Iran. Russia is boiling with revolting and this is the time to speak out. Zelenskyy also spoke out about the Indigenous genocide. Please share!

#indigenous#indigenous russian#indigenous russia#culture#russia#important#colonization#fypシ#fypage#anonymous#Revolt#Help#colonialism#russian imperialism#decolonize#Land back#landback

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

• Mossadegh media: newspaper & magazine articles, editorials

#iran#iranian#tehran#mossadegh#shah of iran#foreign policy#middle east#persia#milwaukee#cold war#britain#history#world history#russian#soviet union#foreign affairs#1950's#1953 coup#great britain#revolt

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Greens

'A "supplies squad" (prodotriad) would arrive in a village, take over the largest house, evict the "kulak" (rich peasant) who lived in it, and instruct all the villagers to deliver a pre-set quota of produce. Those who did not or could not comply were subject to searches, which might involve the ripping up of floorboards and the destruction of furniture, followed, if they proved fruitless, by beatings and arrests. Similarly, armed roadblocks were set up, and checkpoints at railway stations, where peasants taking produce to market were searched and in effect robbed.

At first peasants reacted to these measures with passive rather than active resistance and attempted to seal their economy off from that of town and army. But the Reds' conscription campaigns were merciless, and resistance to them counted as desertion or mutiny, which were punishable by death. The "deserters" would flee into the forests, there to set up armed bands, known as Greens, since they opposed both Reds and Whites. Sometimes they acted independently and sometimes as an armed wing of local peasant communities. In either case, they would operate as partisan bands have done over the centuries, keeping out of the way of large enemy forces, but descending and massacring small detachments and prodotriady.

These disorders rumbled on throughout 1919 but became more persistent during 1920 and the first part of 1921, when in many provinces of the south and east Communist rule was effective only in the towns and intermittently on the main roads and railways. In Ukraine the peasants' antiurban mood was colored by nationalism: here several of the Green leaders called themselves "Atamans." Elsewhere peasant unions were set up to coordinate civil administration with military activity, often with local SR leadership. From the autumn of 1920 partisan bands amalgamated into sizeable peasant armies in much of southeast European Russia, notably Tambov, the Don and Kuban regions, and western Siberia. In the last case, Green leaders captured and for a time ran major towns, such as Tobolsk and Petropavlovsk, entirely cutting communications with the rest of Siberia. Elsewhere the Greens were confined to villages and small towns.

The peasants' political aim in 1920-21 was simple: to defend their way of life against "commissarocracy" (as they called Communist rule) and when possible to take revenge on Communist party members.'

Russia and the Russians, by Geoffrey Hosking

0 notes

Text

no one does “im a piece of shit person but i loved and it broke me” music/books/poetry better than russians

#no one else gets it#russian literature#russian music#its because none of them are afraid to create an actually revolting bad character

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Central Asia Revolt of 1916

When you hear the words “1916” and “Revolt”, you most likely think of Easter Rising. However, there is another revolt in a different colonized territory held by a different imperial power, which was also sparked by delaying the indigenous people’s right to political engagement and threatening them with front line service.

The Central Asian Revolt of 1916 is a bit of an odd revolt because it occurred in the summer of 1916, so from a historical perceptive it’s overshadowed by the bigger battles of WWI and then by the Russian Revolution in 1917. Traditionally, it was thought that the Russian Revolution was more important than the one in Central Asia, so why bother? Thankfully, this opinion has changed over the last few years and now we have experts such as Jonathan Smele who go as far as claiming that the 1916 revolt was actually the beginning of the Russian Civil Wars. And since we are interested in the Central Asian component of the Russian Civil Wars, it makes sense to spend time delving deep into the revolt and its aftermath.

While many people may not know about the rebellion, it was an important moment in Central Asian history and Central Asian-Russian relations. It began Jun July 1916 and ended in February 1917, with losses for the Central Asians generally unknown, although I’ve seen 150,000-200,000 dead for the Kyrgyz people and that’s just the Kyrgyz’s that doesn’t include the Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Tajiks, and other minorities. Nor does it include the number of people displaced and who died fleeing to China following the Russian reprisals. It is only the first many conflicts that will fundamentally change the region and Kyrgyzstan has pressed for the Russian response to the revolt to be recognized as genocide.

Brief overview of Russia and WWI

Russia entered WWI in 1914 and it’s hard to determine if that was the worst decision Tsar Nicholas’ ever made or maybe only his tenth worst. I won’t go into too much detail into the war itself as that’s beyond the scope of this episode and channel, but I highly recommend the Great War, a YouTube history documentary. They do a fantastic job explaining the complexities, not just of the war itself, but specifically of Russia’s attempts to weather that storm. For the purposes of this episode, all we need to know is that when Russia first mustered soldiers for the war, the indigenous peoples of Central Asia were exempt of military service.

Tsar Nicholas 1

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a white man with short brown hair and a full mustache and beard. He is wearing a dark military tunic with epaullettes and many medals and a sash. His hands are held behind his back.]

There are many reasons as to why that was the case. Russia was a particularist empire which meant that that each social group had specific legal status and obligations to the state. The indigenous peoples were part of the inorodtsy, the “foreigners” of Central Asia who didn’t have certain rights, but also didn’t have certain obligations (such as military serve to the empire). Central Asia was also a recently incorporated region that had not known outright rebellion, but had experienced flashes of conflict between the arriving Russian settlers and the indigenous peoples such as the Kazakh and Kyrgyz peoples of the Steppe and the Uzbek and Tajik peoples of the more urban areas as they competed for land, work, and sparse resources. Turkestan was seen primarily as a cotton producer and a place to ship off the poor Russians looking for new opportunities denied them in Russia proper.

The administration was a military apparatus led by a governor-general and held together by two tiers of administrators, the higher tier who were all Russian and the lower tier who were indigenous peoples. Turkestan society was cleaved in two, allowing the indigenous people to pray as they saw fit and continue to use Islamic courts for crimes that weren’t against Russian settlers while creating completely new and guarded spaces for settlers. This combined with Russia’s paranoid fear of Islam and the uneven application of the Duma reforms created great tension within the society.

The administrators feared that allowing indigenous peoples into the ranks of the army would be like smacking the hornet’s nest with a 2 X 4 and stoke insurrection during a world war. They allowed for the formation of a few Turkmen cavalry units, but overall, they didn’t trust the indigenous people to serve in the military’s ranks. It should be noted that some indigenous peoples such as the Jadids, an Islamic modernizing group, and several Kazakh intellectuals wanted to serve in order to gain further rights from Russia after the war. We’ve seen this logic before in Ireland as they wrestled with balancing the desire for further representation and duty to empire.

So, 1914, the indigenous peoples weren’t conscripted into the army, but the region still felt the pinch of war. Before the war, the Kazakh and Kyrgyz people were being bulldozed off their land by Russian settlers and the focus of Russian’s development was on producing more cotton. By 1915, Turkestan produced the most cotton seen in the pre-revolutionary period, but by 1916 the output collapsed.

Kara-Kyrgyz Women from the ethnographical part of Turkestan Album

[Image Description: A sepia tone photo of a Kara-Kyrgyz woman wearing a fur trimmed hat, long, braided black hair, and a round pale face. They are wearing a long shirt and several different necklaces.]

The deportations, higher taxes, industries being commandeered to support the war effort, and ever-increasing demands for grain, overheated the Central Asian economy producing intense inflation in food and fuel prices. This led to increased clashes between the indigenous peoples, for example in February 1916 a group of women enraged by the inflation in food prices and food shortages attacked a Muslim bazaar in the European quarter. Adding to the pressure, and something I haven’t seen a lot of scholarship on yet, but am still looking, is the number of prisoner of wars who came through Turkestan, sometimes being held there is war camps, and sometimes passing through on their way to their final destination. This exasperated the food shortage. Additionally, the war measures combined with the settler’s own search for food drove many Kazakh and Kyrgyz people to starvation. Some historians argue that the Kazakh and Kyrgyz peoples believed they would have to fight for their very lives.

Now between 1914 and 1915, the war didn’t go well for Russia at all. By 1916, they had lost most of Poland and large parts of Ukraine, they had a huge refugee problem (a lot of it spurred by of dumb war policies that implemented a scourged earth policy as they retreated forcing people to follow the army or die), several pogroms, and increased discontentment and rumors that the Tsar had mismanaged the war and the Tsarina was either in bed with Rasputin or in league with the Germans. It’s unclear how much of this filtered into Turkestan, but Russia as a whole was hurting.

Russia would see some successes in their new offenses in 1916, but that also meant that Russia needed to fill the ranks with new soldiers. Feeling the pressure of the war, they broke their one rule: don’t conscript inorodtsy. They still don’t trust the indigenous people to actually fight. Instead, the Imperial Decree of July 7th, 1916, conscripted indigenous peoples into labor battalions. This decree was issued to all Muslims in the Russian Empire, but its disastrous implementation in Turkestan sparked the revolt.

The Imperial Conscription Decree

There were a number of problems with how the decree was implemented in Turkestan, but the biggest issues were how the decree was rolled out, the lack of bookkeeping by the Turkestan administration, and the distrust between the Russians administrators/settlers and the Indigenous peoples.

First, how was the decree rolled out? The short answer is not well. The problem was there was a lot of back and forth between the different levels of Russia proper bureaucracy in terms of when the decree was to take place, who did it affect, what regions were affected etc. Then there was a staggered implementation throughout Turkestan with some province administrators caving into local pressure (or buying themselves time to get organized) and pushing back when the decree would take effect and others holding their ground. Once the decree was announced, the Russian administration had to face the overwhelming task of actually conscripting the indigenous peoples which brings us to the second biggest problem: lack of bookkeeping.

Official Residence of the Russian Military Governor in Tashkent

[Image Description: A sepia tone photo of a stone mansion. It is surrounded by stone walls with a metal grate. There are trees surrounding the palace.]

Unlike other conquered, Muslim territories, the Turkestan administration didn’t have a census of indigenous people who lived in the region. So, they didn’t know who to conscript or how many or anything useful. They turned to their indigenous administrators and told them to compile a list of conscripts. This incited corruption as the local administrators conscripted their enemies, rewarded friends, and protected their own families. This led to ramp corruption and the creation of rumors such as the Russians wanted to conscript ALL young Muslims to destroy what remained of their society and take their land or the Russians were lying about it being labor battalions. They were really suicide squads that would be sent to the most dangerous places of the front to kill all the Muslims and make it easier to take their land after the war. The Russian administration did like to nothing to combat these rumors and they only grew as different oblasts implemented the decree differently.

That leads us to the third biggest problem facing the Russian administration, the lack of trust between the government and indigenous people. The indigenous people had spent decades being confined into ever smaller and smaller safe spaces while many, like the Kazakh and Kyrgyz peoples were being pushed to the brink of mass starvation and homelessness. As we can see from the rumors, many indigenous people were convinced that the Russians were only waiting for the straw that would break the camel’s back and take all of their land and food from them. The indigenous people first turned their anger on the local administrators, threatening them should they create their lists or implement the decree. The Russians may have been able to utilize the local intellectuals such as the Jadids and the Kazakh intelligentsia, but they distrusted them the most. There was also the implicate understanding, at least on the side of the intellectuals, that if they fought for Russia, then they would earn additional political rights, which was the last thing Russia wanted.

All of these factors combined created an explosive power keg that only needed the tiniest of sparks to explode into a conflagration. That spark occurred in Jizzakh.

Central Asian Revolt of 1916

The revolt engulfed most of Turkestan one way or another, but what does that mean? First, we need to understand the geography of Turkestan, which is modern day Central Asia minus the Bukhara and Khiva emirates. We should picture Turkestan five different oblasts or provinces: the Syr Darya and Semirech’e which contain most of the steppe land, and makes up modern day Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. The Ferghana and Samarkand oblast which consist of the lands that once belonged to the former Kokand Khanate and now make up modern day Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan and the Transcaspian region which consisted of land that belongs to modern day Turkmenistan. Hopefully, my listeners who are geography challenged like me, are still with us.

Map of Turkestan

{Image Description: A graphic rendering of the map of Central Asian when it was understand Russian control. The different sections of territory are different pastel colors. The sections not part of the Russian Empire are grey]

Now if we use Easter Rising as a reference point, Easter Rising was a revolt concentrated within a specific city with hopes that the rural areas would rise up in rebellion as well, spreading the British forces thin. Here, in Central Asia, we have the opposite idea. The revolt is concentrated in certain areas such as Jizzakh in modern day Uzbekistan and would have been part of the Samarkand Oblast at the time I believe, most of Semirech’e oblast, and Torghai which is part of the Kazakh steppes, but there wasn’t a centralized location of conflict and there wasn’t a centralized group of ringleaders. There isn’t a Central Asia equivalent to the IRB calling the shots. There are certain leaders who rose up during the revolt, but it was an organic revolt that broke along already existing social ties and tribal affiliations and grew out of decades of tension and sporadic violence.

The first disturbance occurred in Khoqand, which is now in modern day Tajikistan. A large crowd of people gathered outside the offices of the District Commandant, but violence wasn’t the point, even though the police fired into the crowd and there seems to have been a scuffle between the protestors and Russian officials. The first truly violent protest occurred in Jizzakh (in modern day Uzbekistan) on July 12th.

The first violent protest occurred in Jizzakh, in modern Uzbekistan, on July 12th and from there it would spread to Samarkand, Ural’sk, Ferghana, Tashkent, and the Kazakh and Kyrgyz steppes. The rebels targeted not only Russian officials and settlers but their own people who they believed were collaborators, worked in the administration, or obeyed the state. The type of fighting could be divided between those who fought in more urban areas like Tashkent and Samarkand and those who fought in the steppes. Since European settlements and power were more concentrated in the cities, it was harder to organize and resist effectively. But in the Steppes, the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz were able to organize methodically and could rely on the steppe’s vastness to strike quickly and disappear just as quickly while the Russians spread themselves thin trying to find them. The Steppe rebels launched attacks on the core instruments of Russian power. They cut telegraph lines, attacked railways, and launched offensive against Russian garrisons and Russian-dominate towns. This quote from General Sadetskii the commander of the Kazan Military District responsible for sending the initial detachments of Cossacks to the region demonstrates the early success of the Kazakh and Kyrgyz rebels:

“Gathered together in large crowds numbering in the thousands of people, having elected khans for themselves, having earlier secured reserves of food for themselves, having concerned themselves with the organization of the crowd and having armed it, the Kirgiz began a mutinous movement against the Russian People’s right to rule and in general against Russian culture.”

While the rebellion spread throughout Turkestan, this podcast is going to focus on the fighting that occurred first in Jizzakh and then the different conflicts that occurred in the Steppes, but keep in mind that fighting also occurred in the Ferghana, on the Turkestan-China border (and may have been related to the opium trade there) and by several different groupings of Turkmen peoples.

Jizzakh

Jizzakh is where the violence began. It was limited to the volosts (or subdivisions) Za’amin, Boghdan, and Sanzar, and the old town of Jizzakh. The real cause of the violence seems to have been twofold: while other cities and provinces were delaying the implementation of conscription to honor Ramadan, Jizzakh’s administrators refused to do so. Additionally, after drafting a list of draftees, the Jizzakh administration threatened to take land away from anyone who resisted.

It seems that Nazir Khoja Ishan an indigenous merchant, returning from Tashkent (where they had delayed implementing the decree) gathered several hundred people to march on the Russian imperial authorities. Later, Ishan would deny being the leader of revolt during his interrogation. Instead, he stressed that the march was supposed to be “quiet and deliberative.” Instead, at some point during the march, the Russian administrator, Colonel Rukin and 4 members of his staff were killed. The marchers turned to looting and destroying the telegraph lines, bridges, and railways. The railway between Jizzakh and Obruchevo stations were destroyed while the Lomakino train station was burned and sixteen employees were killed. The Russian settlers hid in a local church that was protected by frequent patrols.

The riots continued unabated until the arrival of Russian Lt. Colonel Afanas’ev’s forces on July 17th. With thirty men under his command, he marched into Old Jizzakh to collect the dead. He was joined by General Ivanov on July 18th, who commanded thirteen companies, six cannons 300 Cossacks and an engineer regiment that arrived in an armored train. Their goal was to finalize the pacification of old Jizzakh, before extending military repression to Za’amin, Rabat, the mountain regions, and the volost of Boghdan. By July 21st, the Russians secured the railway stations. In late July/early August, General Aleksey Kuropatkin was removed from the eastern front and sent to Turkestan to put down the Central Asian revolt.

The Russian repression consisted of opening fire at will, burning houses and crops (when they weren’t carrying away the already harvested grain) and confiscating the agricultural tools. The colonial documents mention occasional cases of rape. In total, the initial repression confiscated 2000 desyatinas (which is about 8000 acres according to this conversion site I found) of farmland during harvest session. They would requisition 1000s of acres of land later in the year as continued punishment, exasperating the food and land issues facing the indigenous peoples. The requisition combined with the displacement of indigenous people led to a mass exodus and a famine.

The revolt in Jizzakh was put down on July 26th, lasting barely two weeks. In total, 34 people were arrested, including, Nazir, were sentenced to death by hanging, but only three were carried out. 4 of the prisoners were sent to labor camps, 27 were sentenced to 4 years of prison. On August 20th, General Aleksey Kuropatkin issued the following statement:

“We should hang all of you, but we let you live for you to be a dissuasive example to others. The place where Colonel Rukin was killed will be razed to zero over a distance of 5 versts and this area will become state property. We must not wait to expel the population living on the territory.”

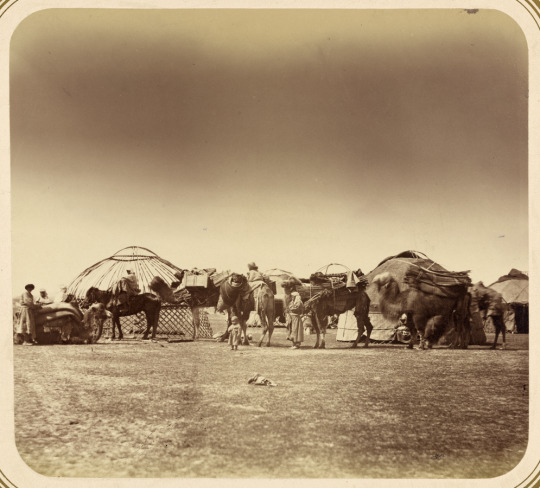

Kazakh and Kyrgyz Steppe (Semirech’e)

The fighting in the Steppe, especially Semirech’e (se mi retch eh) was a fight for the right to exist. The Kazakh and Kyrgyz people had spent decades desperately trying to retain their ever-shrinking land as more and more settlers streamed in and this revolt seems to have been a culmination of all that fear, frustration, and loss. The revolt started with the rebels threatening indigenous officials, even though many of the leaders of the revolt were in fact administrators of the volosts. Additionally, many of these leaders were known as baatyrs, individuals of military prowess proven in daring exploits against enemies. Russian officials arrested these agitators but only angered the indigenous people who began to demand that local officials give them the list of draftees. Communal meetings of indigenous people met and discussed the draft, and they decided to resist.

Syr Darya Oblast. Kyrgyz Migration

[Image Description: A sepia toned photo of a caravan of camels gathered together. There are wood frames for khurts. Men and women are preparing for the day.]

Early August saw the first violent clashes between the rebels and Russian officials. It began in the Lepsinsk district between July 24th and August 1st, when a Russian border patrol detained a fleeing family. On August 3rd, in the eastern part of Vernyi, the assistant head of the district Khlynovskkii and the District Police Captain Kulaev and fifteen soldiers and policemen took several Kazakh dignitaries hostage in an effort to force the volost to produce lists within five hours. The Kazakhs asked Khlynovskii three times to release the arrested and delay the draft. Khlynovskii fired into the air to disperse the crowd but his men thought it was an order to shoot and they killed two Kazakhs. The crowd killed a policeman and then the Cossack cavalry squadron was sent in the area on the same day.

Then on August 6th also in the Vernyi district, a native administrator manipulated the list to including Kazakhs of the rival party. The aggrieved party approached the district police captain Gilev, but he sided with the volost head, believing the indigenous people were plotting to revolt. He used twenty policemen against the rival party in the area of the Samsy station. The native population gathered in a large crowd and forced Gilev and his men to retreat while firing into the crowd, killing twelve Kazakhs. The Kazakhs targeted the telephone poles, plundered the station, and rustled cattle. They then fled into Bishkek district, but not before killing sixteen settlers and taking 35 settlers captive. Their arrival in Bishkek sent panic but they began to organize, one group attacking a post office at Jal-Aryk station.

The rebels went from random, mass groups of people into organized units headed by military commanders drawn from the volost heads. They wore metal badges and the rebels sent messages through lanterns. Some even had banners. On July 31st, only a thousand Steppe rebels reported for duty. By mid-August that would grow to 10,000-20,000 rebels in the Semirech’e oblast.

By August 7th, the Russian administrators were sending panicked reports that all of Semirech’e was in revolt. Similar to the rebels in Jizzakh, the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz targeted the telephone poles and railway stations before unleashing punitive attacks on Russian settlers. Some of the worst violence would be seen in the districts of Bishkek and Karakol where 3000+ Russian settlers were killed.

On August 12, 1500 rebels attacked a Cossack sotnia, and a 350 settler militia in a battle in the environs of Toqmaq. The Russians nearly lost a machine gun and retreated into Toqmaq. On August 13, 5000 rebels besieged the city, which was cut off from Vernyi and Tashkent for two weeks between August 13 and 22. The city was able to rebel against their attacks because the rebels were poorly armed. The Kazakhs also laid sieges to the settlement at Preobrazhenskoe, a safe haven for refugees from 10 to 29 August. On 28 August, a punitive expedition lifted the siege and the rebels retreated. In response to the rebel units, the settlers began to mobilize as well, creating militias to defend themselves.

By early September, the Russians sent 35 infantry companies, 24 Cossack cavalry squadrons, 20 mounted scouts, 16 field guns, and 47 machine guns to Semirech’e to put down the revolt. Some of their methods included driving Kazakhs into ambushes and execute as many as possible. For example, 500 Kyrgyz were killed at one time in a valley near Bishkek. They took land and killed women and children and there were reports of rape. While rape wasn’t an order, the soldiers were commanded to murder and plunder, the Russians determined to crush the revolt brutally both as a deterrent and to indulge in the bad blood between settlers and the indigenous peoples. Rebel leaders were executed on the spot by field courts for state treason and a general, Folbaum, ordered the complete extermination of the entire native male population of the Atekinskaia and Sarybagishebskaia volosts.

Russian Response and the Urkun Exodus

By October, the Russian regained control over Semirech’e with Kuropatkin declaring that wherever the Russian blood had been spilled, the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz were to be expropriated and expelled. According to him the natives had forfeited the right to live together with the Russians because of the uprising and proposed creating an ethnically-cleansed zone for Russian settlement on the best land in the region around Issyq-Kul. About 37,000 Kazakh and Kyrgyz households were affected. 16% of their land was expropriated while the Slavic population grew to 23% of the entire population. 190,000 people were removed from the Pishpek, Przheval’sk, and Dzharkent districts. Przheval’sk was completely cleaned of its Kyrgyz and Dungan population. They and other indigenous peoples were forcibly relocated to the mountainous areas near Naryn where they would be fenced off by mountains and a string of militarized Cossack settlements.

It is estimated that the Russians killed 16,000 Kyrgyz and Kazakh peoples, while about 3000 Russian settlers were killed. A massive famine devastated the indigenous people while hundreds of thousands fled to China and died along the way, in what is now known as the Urkun exodus. Early blizzards, deep ravines and sharp cliffs, lack of grass and heavy livestock losses, coupled with chaos and stampeding of animals and people killed more people than guns and cannons. Still more died in China and at home after the return. Out of the 164,000 refugees who made it to China, about 130,000 were Kyrgyz and 34,000 were Kazakhs. By May 1917, 70,000 Kazaks and Kyrgyz starved to death.

And yet fighting would continue in 1917. Another group of Steppe rebels would reorganize in Torghai region in Kazakh Steppe. By October, a 50,000 strong rebellion besieged the town of Torghai, were defeated, and fought a guerilla war against the Russians forces sent against them. They were still fighting by the February Revolution. There was also a minor rebellion led by the Turkmen in Khiva, led by Junaid khan (later emir of Khiva?) and the Turkmen at Chikishlar on the Caspian Sea where they clashed with Russian fishermen. It can even be argued that some of the fighting merged into the civil war that followed the fall of the Tsar and that the Central Asia Revolt, truly was the beginning of the Russian Civil war.

It is estimated that the Russians killed 88,000 indigenous peoples while 250,000 people fled to China. That’s about 20% of the population. Additionally, 50% of the local population’s horses, 50% of their camels, 39% of their cattle, and 58% of their sheep and goats were killed or confiscated. The bloody suppression of the revolt shocked and revolted people in Russia. Alexander Kerensky, who grew up in Tashkent, criticized the monarch’s response in the Duma. He even went on tour of the region and there was a cry to address indigenous people’s wants and desires within the empire. However, the revolt was quickly overshadowed by the Russian Revolution of 1917 and, the civil wars that followed.

Resources:

Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent 1865-1923 by Jeff Sahadeo

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Knowledge and the Ends of Empire: Kazak Intermediaries and Russian Rule on the Steppe, 1731-1917 by Ian W. Campbell Published by Cornell University Press, 2017

Russia and Central Asia: Coexistence, Conquest, Coexistence by Shoshana Keller Published by University of Toronto Press, 2019

Russia’s Protectorates in Central Asia: Bukhara and Khiva, 1865-1924 by Seymour Becker, Published by RoutledgeCurzon, 2004

The “Russian Civil Wars” 1916-1926 by Jonathan Smele, Published by Oxford University Press, 2017

#central asia#central asian history#Central Asian Revolt 1916#history blog#queer historian#podcast episode#blog post#queer podcaster#season 2: central asia#world war 1#WWI#russian empire#russian colonialism#Spotify

0 notes

Text

The Road to Intervention: March-November 1918 :: Michael Kettle

View On WordPress

#0-4150-0371-7#allied forces#baltic fleet#bolshevik history#books by michael kettle#czech revolt#first edition books#first international battalion guards#history red army#history russia#history soviet union#military history#russia and the allies 1917-1920 series#russian diplomacy#russian diplomatic relations#russian fleets#russian history#soviet diplomatic history#soviet union forces world war#vladivostok

0 notes

Photo

(via पुतिन के खिलाफ सार्वजनिक विद्रोह - इसके परिणाम(Revolt against Putin))

1 note

·

View note