#sancho ii

Photo

The Siege of Zamora, Resin Magnet.

Our souvenir, which depicts King Sancho II of Castile being impaled by his own golden spear while doing his business, is a fun way to have a piece of history on your fridge.

Available in ArteFeudo’s Etsy shop.

#Arte Feudo#sculpture#toy art#art toy#resin figure#history#Zamora#Spain#Sancho II#Urraca#magnet#artists on tumblr#resin magnet#Bellido Dolfos#Spanish history#King Sancho II#king#kingdom

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

ISABEL TVE 2x06

#perioddramaedit#perioddramasource#weloveperioddrama#isabel tve#2x06#isabella i of castile#ferdinand ii of aragon#michelle jenner#rodolfo sancho

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Royal Birthdays for today, April 21st:

Sancho VI, King of Navarre, 1132

Wilhelmine Amalie of Brunswick, Holy Roman Empress, 1673

Elisabeth of Württemberg, Archduchess of Austria, 1767

Elizabeth II, Queen of the United Kingdom, 1926

Isabella of Denmark, Countess of Monpezat, 2007

#elizabeth ii#queen elizabeth ii#princess isabella#Elisabeth of Württemberg#elisabeth of wurttemberg#Wilhelmine Amalie of Brunswick#sancho vi#long live the queue#royal birthdays

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

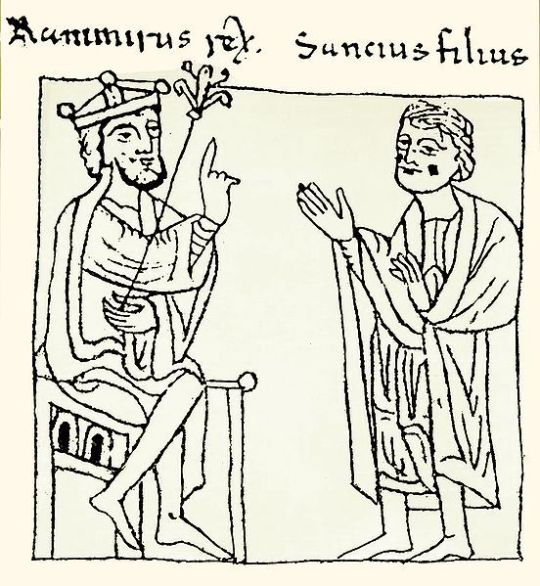

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

1) Ramiro I of Aragon (1006/7- 1063), son of Sancho III of Pamplona and Sancha de Aybar; with his son Sancho I of Aragon & V of Pamplona (1043-1094)

2) His wife, Ermesinda of Foix (1015 - 1049), mother of Sancho I of Aragon. Daughter of Bernard Roger de Foix and his wife Garsenda de Bigorra; and Sancha of Aragon (1045-1097), daughter of Ramiro I and Ermesinda

3) His father, Sancho III of Pamplona (992/96-1035), son of García II of Pamplona and Jimena Fernández

4) His brother, García III of Pamplona (1012-1054), son of Sancho III of Pamplona and his wife Muniadona of Castile

5) His nephew, Sancho IV of Pamplona (1039- 1076), son of García III of Pamplona and his wife Placencia of Normandy

6) His brother, Ferdinand I of Leon (1016- 1065), son of Sancho III of Pamplona and his wife Muniadona of Castile

7) His niece, Urraca of Zamora (1033-1101), daughter of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

8) His niece, Elvira of Toro (1038-1099), daughter of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

9) Sancho II of Castile (1038/1039-1072), son of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

10) Alfonso VI of Leon (1040/1041-1109), son of Ferdinand I of Leon and Sancha of Leon

#jonsnowfortnightevent#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medieval bastard kings#ramiro i of aragon#sancho i of aragon#sancha of aragon#ermesinda of foix#sancho iii of pamplona#garcía iii of pamplona#sancho iv of pamplona#ferdinand i of leon#urraca of zamora#elvira of toro#sancho ii of castile#alfonso vi of leon#bastard kings and their families#canonjonsnow

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michelle Jenner and Rodolfo Sancho as Isabel de Castilla and Fernando de Aragon in Isabel

#isabel tve#michelle jenner#rodolfo sancho#isabella i of castile#ferdinand ii of aragon#isabel de castilla#fernando II de aragon#tumblr art

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

This lovely Grey Cloak is worn on Rodolfo Sancho as King Fernando II in the The Broken Crown (2016) and its seen again on Uknown Actor as Noble in The White Princess (2017).

#recycled costumes#the broken crown 2016#rodolfo sancho#King Fernando II#the white princess#period drama#historical drama#costume drama#reused costume#reused costumes#costumes#perioddramasource#perioddramaedit#dramasource

0 notes

Text

This lovely Grey Cloak was first spotted on Rodolfo Sancho as King Fernando II in the The Broken Crown (2016) and its seen again on Uknown Actor as Noble in The White Princess (2017).

#recycled costumes#La corona partida 2016#the broken crown 2016#Rodolfo Sancho#King Fernando II#period drama#historical drama#reused costume#costume drama#reused accessories#perioddramasource#perioddramaedit#dramasource

0 notes

Text

AU: Valois House. Children Francis I and Claude Valois.

Luisa(1515 - 1576). Queen of Spain and Empress of the Holy Roman Empire. Wife of Charles V. Despite the fact that the age difference between the spouses was 16 years, they loved each other. Charles treated his young wife with tenderness. She was interested in music, dancing and writing. Luisa and Charles had 7 children: John III, Claude, Philip, Ramiro, Ferdinand, Joana, Charles.

Charlotte(1516 - 1570). Queen of Portugal. Wife of Juan III and mother of 6 children: José I, Manuel, Isabella, Sancho, Aldegunda, Mary. Charlotte devoted much time to the education of her children and the enlightenment of the Portuguese court. She was the favorite sister of Francis II and maintained a close relationship with his wife.

Francis II(1518 - 1590). King of France. Husband of Mary Tudor. Francis loved his wife. Unlike his father and brothers, he never had mistresses or children out of wedlock. The reign of Francis II was an era of prosperity and rise. Father of 8 children: Claude, Francis III, Catherine, Charlotte, Tristan, Raoul, Adele, Henry.

Henry(1519 - 1587). Duke of Orleans. Husband of Catherine de Medici and father of 10 children: Francis, Elizabeth, Claude, Louis, Charles, Henry, Margaret, Hercule, Victoria and Jeanne. All his life loved only his mistress Diana de Poitiers, even wanted to marry her, but because of pressure from his father did not do it.

AU: дом Валуа. Дети Франциска I и Клод Валуа.

Луиза(1515 - 1576). Королева Испании и императрица Священной римской империи. Жена Карла V. Несмотря на то, что разница в возрасте между супругами была 16 лет, они любили друг друга. Карл с нежностью относился к молодой жене. Интересовалась музыкой, танцами и писательством. У Луизы и Карла родилось 7 детей: Хуан III, Клод, Филипп, Рамиро, Фердинанд, Хуана, Карл.

Шарлотта(1516 - 1570). Королева Португалии. Жена Жуана III и мать 6 детей: Жозе I, Мануэль, Изабелла, Саншу, Альдегунда, Мария. Шарлотта уделяла много времени образованию своих детей и просвящению Португальского двора. Была любимой сестрой Франциска II и поддерживала близкие отношения с его женой.

Франциск II(1518 - 1590). Король Франции. Муж Марии Тюдор. Франциск любил свою жену. В отличие от отца и братьев у него никогда не было любовниц и внебрачных детей. Правление Франциска II было эпохой процветания и подъёма. Отец 8 детей: Клод, Франциск III, Екатерина, Шарлотта, Тристан, Рауль, Адель, Генрих.

Генрих(1519 - 1587). Герцог Орлеанский. Муж Екатерины Медичи и отец 10 детей: Франциск, Елизавета, Клод, Людовик, Карл, Генрих, Маргарита, Эркюль, Виктория и Жанна. Всю жизнь любил только свою любовницу Диану де Пуатье, даже хотел на ней жениться, но из-за давления отца не стал этого делать.

Part 1.

#history#history au#royal family#royalty#au#france#france history#History of France#French royal family#french#french royalty#french royal family#French royal#Royal#Royals#the tudors#henryviii#mary tudor#the serpent queen#catherine de medici#mary stuart#Henryii#francis valois#The reign#elizabeth i#15th century#16th century#Francis i#Francisii#French kings

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro (1857-1929)

"Tragedy of Inês de Castro" (1901-1904)

Realism

Located in the Museu Militar de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

Inês de Castro (1325-1355) was a Galician noblewoman and courtier, best known as lover and posthumously-recognized wife of King Peter I of Portugal. The dramatic circumstances of her relationship with Peter (at the time Prince of Portugal), which was forbidden by his father King Afonso IV, her murder on the orders of Afonso--she was decapitated in front of one of her young children—Peter's bloody revenge on her killers—he captured two of them and publicly executed them by ripping their hearts out, claiming they didn't have one after pulverizing his own heart—and the legend of the coronation of her exhumed corpse by Peter, have made Inês de Castro a frequent subject of art, music, and drama through the ages.

Inês and Peter also had several children, whom he would legitimize after her death. Afonso, died shortly after birth. John, Duke of Valencia de Campos, claimant to the throne during the 1383–85 Crisis. Denis, Lord of Cifuentes, claimant to the throne during the 1383–1385 Crisis. And Beatrice, who married Sancho Alfonso, 1st Count of Alburquerque, the great-grandmother of Ferdinand II of Aragon and thereby an ancestor of all Spanish monarchs.

#paintings#art#artwork#history painting#tragic love#columbano bordalo pinheiro#fine art#realism movement#lisbon military museum#museum#art gallery#portuguese artist#history#tragedy#doomed love#forbidden love#portugal#monarchy#early 1900s#early 20th century

109 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vere novo , priori jam mutato consilio , Alienora virgo regia , insignis facie , sed prudentia & honestate prestantior , futura Regina Sicilie , atque cum ea Nymphe obsequiis apte regalibus , accepta benedictione parentum , ab urbe Neapoli gloriosas discessit , per Calabriam , propter maris tedium , usque Regium iter agens : quam discedentem Neapolitane matres , quantum spectantes oculi capere potuerunt , effusis pre gaudio lacrimis affequute sunt.

Gregorio Rosario, Bibliotheca scriptorum qui res in Sicilia gestas sub Aragonum imperio retulere, I, p.456-457

Eleonora was born in Naples in the summer of 1289 as the tenth child (third daughter) of Carlo II lo Zoppo of Anjou, King of Naples, Count of Anjou and Maine, Count of Provence and Forcalquier, Prince of Achaea, and of Maria of Hungary.

Nothing, in particular, is known about her childhood, which she must have spent with her numerous siblings in the many castles of the Kingdom.

She is first mentioned in a Papal bull dated 1300 in which Boniface VIII annulled the marriage of 10 years-old Eleonora to Philippe de Toucy, Prince of Antioch and Count of Tripoli, (the contract had been signed the year before) on account of the bride’s young age and the fact that family hadn’t asked for the Pope’s dispensation.

Two years later, there were discussions of a match with Sancho, the second son (and later successor) of Jaume II of Majorca, but the engagement never occurred.

Finally, in 1302, Eleonora’s fate was sealed. On August 31st 1302 the Houses of Anjou-Naples and of Barcelona signed the Peace of Caltabellotta, which ended the first part of the War of the Sicilian Vespers and settled (or tried to) the problem of which House should have ruled over Sicily. Following this treaty, the old Norman Kingdom’s territory (disputed between the French and Spanish born ruling houses) was to be divided into two parts, with Messina Strait as the ideal boundary line. The peninsular part, the Kingdom of Sicily, now designed as citra farum (on this side of the farum, meaning the strait, later simply known as the Kingdom of Naples ), and the island of Sicily, renamed the Kingdom of Trinacria, designed as ultra farum (beyond the farum).

The Peace of Caltabellotta stipulated that Angevin troops should evacuate the island, while the Aragonese ones should leave the peninsular part. Foundation of the peace would have been the marriage between princess Eleonora of Anjou and King Federico III (or II) of Sicily (“e la pau fo axi feyta , quel rey Carles lexava la illa de Sicilia al rey Fraderich, que li donava a Lieonor, qui era e es encara de les pus savies chrestianes, e la millor qui el mon fos, si no tant solament madona Blanca, sa germana, regina Darago. E lo rey de Sicilia desemparava li tot quant tenia en Calabria e en tot lo regne: e aço se ferma de cascuna de les parts, e que lentredit ques llevava de Sicilia; si que tot lo regne nach gran goig." in Ramon Muntaner, Crónica catalana, ch. CXCVIII). The pact dictated also that once Federico had died, the two kingdoms would be reunited under the Angevin rule. This clause won’t be fulfilled.

The bridal party had to wait until spring 1303 before setting off for her new country since sea storms had damaged part of the fleet and thus delayed the departure. The voyage had cost 610 ounces, where the Florentine bankers Bardi and Peruzzi were asked to advance the payment, and the groom pledged to repay them 140 ounces.

By May 1303, Eleonora and her companions arrived in Messina where she was warmly welcomed and where on Pentecost, May 26th, of the same year she got married to Federico in Messina’s Cathedral (“E a poch de temps lo rey Carles trames madona la infanta molt honrradament a Macina, hon fo lo senyor rey Fraderich, qui la reebe ab gran solemnitat. E aqui a Macina, a la sgleya de madona sancta Maria la Nova, ell la pres per muller e aquell dia fo llevat lentredit per lola la terra de Sicilia per un llegat del Papa, qui era archebisbe, que hi vench de part del Papa, e foren perdonats a tot hom tots los pe cats quen la guerra haguessen feyts: e aquell dia fo posada corona en lesta a madona la regina de Sicilia, e fo la festa la major a Macina que hanch si faes.” in Ramon Muntaner, Crónica catalana, ch. CXCVIII).

After the wedding, most of the bridal party returned to Naples, while the newlyweds proceeded to Palermo.

On July 14th 1305 Eleonora gave birth to the heir, who was called Pietro in honour of the child’s paternal grandfather, Pere III of Aragon. To celebrate his son’s birth, Federico III gifted his bride of Avola castle and the surrounding land, to which will be added the city of Siracusa (in 1314), Lentini, Mineo, Vizzini, Paternò, Castiglione, Francavilla and the farmhouses in Val di Stefano di Briga. This gift would mark the creation of the Camera reginale, which would become the traditional wedding present given to Sicilian Queen consorts, and eventually would be abolished in 1537.

Including Pietro, she would give birth to nine children: Costanza (1304 – post 1344), future Queen consort of Cyprus, Armenia and Princess consort of Antiochia; Ruggero (born circa in 1305 - ?) who would die young; Manfredi (1306-1317) first among his brothers to hold the title of Duke of Athens and Neopatras; Isabella (1310-1349) Duchess consort of Bavaria; Guglielmo (1312-1338) Prince of Taranto and heir to the Duchy of Athens and Neopatras following the death of his brother; Giovanni (1317-1348) Duke of Randazzo, Count of Malta, later also Duke of Athens and Neopatras and Regent of Sicily; Caterina (1320-1342) Abbess of St. Claire Nunnery in Messina; Margherita (1331-1377) Countess Palatine consort of the Rhine.

Through these donations Eleonora became a full-fledged vassal, and had to pay homage to her husband the King. Thanks to official documents, we get the idea that Eleonora tried to manage her lands as much personally as she could do, naming herself vicars, administrators, and granting tariff reductions. Federico indulged his wife as much as he could, although in some cases (like the management of the city of Siracusa) his will was the only one taken into account.

Despite almost every time she was unsuccessful, Eleonora fully embraced her role as mediator between the Aragonese and Angevins. For example, in 1312 her brother-in-law, King Jaume II of Aragon, asked her to dissuade her husband (Jaume’s brother) to ally himself with the Holy Roman Emperor Heinrich VII of Luxembourg since this alliance could generate new friction with the Angevin Kingdom, as well as with the Papacy (with the risk of stalling the Aragonese occupation of Sardinia). After the King of Aragon, it was Pope Clemente’s turn to ask Eleonora to convince Federico to make peace with Roberto of Anjou. In both cases, though, her conciliatory efforts didn’t work.

In 1321 she witnessed her son Pietro being associated to the throne and thus crowned in Palermo (“Anno domini millesimo tricentesimo vicesimo primo, dum Johannes Romanus Pontifex contra Fridericum Regem, & Siculos propter invasionem bonorum Ecclesiarum precipue fulminaret, Fridericus Rex primogenitum suum Petrum, convenientibus Siculis, coronavit in Regem, & patris obitum, inopinatum premetuens, & ut filius qui purus videbatur & simplex, ab adoloscentia regnare cum patre affuesceret patrisque regnando vestigiis inhereret […]” in Gregorio Rosario, Bibliotheca scriptorum ..., I, p. 482). Pietro’s coronation publicly violated the Treaty of Caltabellotta (as the Kingdom should have returned to the House of Anjou), causing the pursuing of warfare between Naples and Palermo. Once again Eleonora’s attempts at peace-making failed miserably, with her nephew, Carlo Duke of Calabria, refusing to even meet her in 1325, after he had successfully raided the outskirts of Messina.

The Queen didn’t have much luck in internal policy too as she failed to appease her husband and her protegé, Giovanni II Chiaramonte. After gravely wounding Count Francesco I Ventimiglia of Geraci (his brother-in-law and one of the King’s trustees), all that Eleonora could do was advise Chiaramonte to flee to avoid the death penalty.

Nevertheless, the Pope still hoped to use the Queen (who, at that time and alone in her Kingdom, was exempted from the Papal interdict) as mediator with her husband, promising to lift the excommunication in exchange for Federico’s backing down. Once again nothing happened.

On June 25th 1337 Federico III died near Paternò. He was buried in Catania since it was too hot for the body to be transported to Palermo (“Feretrum humeris nobiliores efferunt. Adsunt Regii filii, proceresque Regni. Exequias Regina, illustribus comitata matronis, prosequitur.” in Francesco Testa, De vita, et rebus gestis Federici 2. Siciliæ Regis, p.225). After the death of her husband, the now Dowager Queen turned to religion, following the example of those in her family who had consecrated themself to Christ (“At Heleonora certiorem fe de illa consolandi rationem inivit. Ipsa enim , ut Rex excessit e vita, ei, qui omnis consolationis fons est, fese in Virginum collegio Franciscanæ familiæ Catinæ devovit; in hoc Catharinan , & Margaritam filias imitata, quæ in ætatis flore, falsis terrestribus, contemptis bonis, Christ, cui fervire regnare est, in sacrarum Virginum Messanensi Collegio, de Basicò dicto, ejusdem Franciscanæ familiæ fese consecrarant; quod Collegium posteaquam Catharina fancte gubernavit, sanctitatis opinione commendata deceffit” in Francesco Testa, De vita..., p.226).

If Eleonora might have hoped to exert some kind of influence as many other Queen mothers did in the past and would do in the future over their weak-willed royal children, she would soon realize she had a powerful rival in the new Queen consort, her daughter-in-law, Elisabetta of Carinthia. Like Eleonora, the new Queen supported the Latin faction (a group of Sicilian noblemen who opposed the Aragonese rulership over Sicily, hoping the island would be returned under the influence of the Angevins instead). But, while Elisabetta had managed to raise the Palizzis to the highest positions at court, her mother-in-law still supported the Chiaramonte, making it possible for the exiled Giovanni II to return to Sicily, be pardoned by the King and see all his goods be returned. Soon though Chiaramonte resumed his personal feud against the Ventimiglia (also part of the Latin faction) and once again Eleonora's attempt to bring peace failed miserably. Only through Grand Justiciar Blasco II d'Alagona's intervetion, the crisis was averted.

In 1340, the Dowager Queen made a last attempt to appease the new Pope, Benedict XII. Unfortunately, the Sicilian envoys sent to Avignon to take an oath of vassalage (since Norman times Sicily theoretically belonged to the Papacy, who granted it to the Sovereigns who acted as Papal Legates) were treated roughly by the Pope, who declared Roberto of Anjou (Eleonora's brother) as Sicily's legitimate King.

Deeply distraught, the Dowager Queen resolved to definitely retire from public life. She spent what it remained on her life visiting the monastery of San Nicolo' d'Arena (Catania), joining the monks in their religious life. She died in one of the monastery's cells on August 10th 1341. Her body would be buried in the Church of San Francesco d'Assisi all'Immacolata (Catania), the construction of which she had personally promoted in 1329 to thank the Virgin Mary for protecting the city from one of many Mount Etna's eruptions.

Sources

AMARI MICHELE, La guerra del Vespro siciliano

CORRAO PIETRO, PIETRO II, re di Sicilia in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 83

DE COURCELLES JEAN BAPTISTE PIERRE JULLIEN, Histoire généalogique et héraldique des pairs de France: des grands dignitaires de la couronne, des principales familles nobles du royaume et des maisons princières de l'Europe, Vol. XI,

FODALE SALVATORE, Federico III d’Aragona, re di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 45

GREGORIO ROSARIO, Bibliotheca scriptorum qui res in Sicilia gestas sub Aragonum imperio retulere, I,

KIESEWETTER ANDREAS, ELEONORA d'Angiò, regina di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 42

de MAS LATRIE LOUIS, Histoire de l'île de Chypre sous le règne des princes de la maison de Lusignan. 3

MUNTANER RAMON, Crónica catalana

Sicily/naples: counts & kings

TESTA FRANCESCO, De vita, et rebus gestis Federici 2. Siciliæ Regis

#historicwomendaily#historical women#history#history of women#herstory#eleanor of naples#frederick iii of sicily#house of aragon and sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#aragonese-spanish sicily#myedit#historyedit

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nesta foto, tirada em 1950 pelo fotografo francês Jean Dieuzaide na localidade de Vieira de Leiria, e a que deu o título "Mulher a Acartar", se percebe bem a estreita ligação do povo português com o povo árabe e a sua ancestralidade cultural com povos que viveram na Peninsula Ibérica, antes de terem sido derrotados em batalhas diversas e optado pela sua fuga para a província do Algarve, onde apenas foram desalojados no ano de 1234.

O Algarve foi considerado, durante séculos e até à proclamação da República Portuguesa em 5 de outubro de 1910, como o segundo reino da Coroa Portuguesa - um reino de direito separado de Portugal, ainda que de facto não dispusesse de - na prática, era apenas um título honorífico sobre uma região/comarca que em nada se diferenciava do resto de Portugal. Porém, que nunca nenhum rei português foi coroado ou saudado como sendo apenas "Rei do Algarve" - no momento da sagração, era aclamado como "Rei de Portugal e do Algarve" (até 1471), e mais tarde como "Rei de Portugal e dos Algarves" (a partir de 1471).

O título de "Rei do Algarve" foi pela primeira vez utilizado por Sancho I de Portugal, quando da primeira conquista de Silves, em 1189. Silves era apenas uma cidade do Califado Almóada, posto que nesta altura todo o Al-Andaluz se achava unificado sob o seu domínio. Assim, D. Sancho usou alternadamente nos seus diplomas as fórmulas "Rei de Portugal e de Silves", ou "Rei de Portugal e do Algarve"; excepcionalmente, conjugou os três títulos no de "Rei de Portugal, de Silves e do Algarve".

O único motivo que pode justificar esta nova intitulação régia prende-se com a tradição peninsular, de agregar ao título do monarca o das conquistas efetuadas. Mas, com a reconquista muçulmana de Silves, em 1191, o rei cessou de usar este título.

O Califado Almóada viria a desagregar-se na Hispânia em 1234, dissolvendo-se em vários pequenos emirados, as taifas. O Sul de Portugal ainda em mãos muçulmanas ficou anexado à taifa de Niebla, na moderna Espanha; o seu emir, Muça ibne Maomé ibne Nácer ibne Mafuz, proclamou-se pouco tempo mais tarde "Rei do Algarve" (amir Algarbe), posto que o seu Estado compreendia, de facto, a região mais ocidental do Al-Andaluz muçulmano.

Ao mesmo tempo, as conquistas portuguesas e castelhanas para o Sul prosseguiam. No reinado de D. Sancho II conquistaram-se as derradeiras praças alentejanas e ainda a maior parte do Algarve moderno, na margem direita do rio Guadiana; à data da sua deposição e posterior abdicação, restavam do Algarve muçulmano apenas pequenos enclaves em Aljezur, Faro, Loulé e Albufeira, os quais, devido à descontinuidade territorial e à distância que os separava de Niebla, se tornaram independentes do seu domínio.

João Gomes

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ISABEL TVE 1x09

@timesthatneverwere

#perioddramaedit#weloveperioddrama#isabel tve#1x09#isabella i of castile#ferdinand ii of aragon#michelle jenner#rodolfo sancho

89 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Birthdays for today, April 21st:

Sancho VI, King of Navarre, 1132

Wilhelmine Amalie of Brunswick, Holy Roman Empress, 1673

Elisabeth of Württemberg, Archduchess of Austria, 1767

Elizabeth II, Queen of the United Kingdom, 1926

Isabella of Denmark, Countess of Monpezat, 2007

#elizabeth ii#princess isabella#Wilhelmine Amalie of Brunswick#elisabeth of wurttemberg#queen Elizabeth ii#sancho vi#long live the queue#royal birthdays

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juraría que la conozco de algo...

Isabel (2012-2014), 2×01 Desencuentros II El Ministerio del tiempo (2015-), 1×04 Una negociación a tiempo

#el ministerio del tiempo#isabel tve#1×04#una negociación a tiempo#2×01#desencuentros#nacho fresneda#aura garrido#rodolfo sancho#michelle jenner#eusebio poncela#ramón madaula#alonso de entrerríos#amelia folch#julián martínez#fernando ii de aragón#ferdinand ii of aragon#isabella i of castile#isabel i de castilla#cardenal cisneros#gonzalo chacón#francisco jiménez de cisneros#emdt#mdt

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

i haven't gotten to do a deep dive blaseball numbers question in a while. so when @leonstamatis asked a question and i realized i was curious, i got excited.

how common/likely is it for a blb player to have a completely unique name that they do not share with anyone. a first and last name, neither of which has been given to anyone else yet.

TLDR: 5.5% of all randomly-generated names are fully unique, and 7% of randomly-generated names of beta players are fully unique within the beta.

but let's break it down a little more.

so first thing's first: i needed a list of players. a quick check with sibr and i ended up using astrology to get two lists: one of all the players from the beta/gamma teams, and one of all the players on delta/coronation teams. i merged the lists and made a note of when players first appeared: beta, coronation, coffee cup, prehistory, the forbidden short circuits teams that didn't make it onto the website, you get the idea.

final list: 5,072 names. boy howdy.

next: nonrandom names! a lot of names were generated in nonrandom ways, like replicas (which are all named after the original player), coffee cup teams (where the artists/data witches/real game band were all manually named), and even things like evelton mcblase ii and bontgomery mullock, where the name is based on another randomly generated name.

list of random names: 4,876. if that's not 3.8% more manageable then i don't know what is!

from there the steps were pretty simple. separate the names into first/given names and last/surnames, see how many of each of those was unique, and then see how many names were not shared with anyone else.

so looking at all of the 4,876 players randomly generated ever at all:

752 have unique first names (15.4%)

926 have unique surnames (19%)

259 have completely unique names (5.3%)

most of the 259 unique names come from prehistory, with an overwhelming 51%, followed by 26% from beta and 13% from the coronation era.

of course, most of us are here primarily for the beta, so how does that stack up? there are 973 names generated that were on beta teams, either in active play or in the shadows. of those 973 names,

227 have unique first names (23%)

250 have unique last names (25.7%)

68 have completely unique names (7%)

for me, this all naturally leads to another question: what are the most common names? across all 4,876 players the most common first names are:

dimi (12)

sebastian (12)

chandra (10)

ruth (10)

bennett (10)

bernie (10)

dagmar (10)

dominic (10)

eliot (10)

wyatt (10, although 4 of these are due to the wyatt masoning)

and the most common surnames are:

murphy (12)

davis (11)

caster (10)

highway (10)

horne (10)

schofield (10)

based on these numbers, which names are the least unique - that is to say, who has the most other players that match either their first or last name?

juan murphy (6 other juans, 11 other murphys)

eliot schofield (8 other eliots, 9 other schofields)

sebastian owens (11 other sebastians, 6 other owenses)

dimi santana (11 other sebastians, 6 other santanas)

and the final question: what full names have been randomly generated more than once? there are 8, and all of them happened in short circuits:

bees manhattan

candy finnegan

copernicus biscuits

layla pork

levar shoemaker

sancho thrower

tall everts

worf hatchler

and notably, the pairs of candy finnegan and layla pork were within the same short circuit! every other pair was across two different circuits.

if you're interested in name uniqueness, here's my spreadsheet - i did the legwork so you don't have to! please drop me a line if you notice anything weird (sooooooo many nonrandom names have snuck into my random names tab) and if you do any other name number crunching, let me know about that too!

#waveridden.txt#i need a blaseball tag#did i have a tag for weird stats stuff. i don't think i did#anyways this was fun as hell. tell your friends. please god

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thoughts on Sade?

Nothing there. I did an experiment around the lockdown over four years ago where I would write little essays on my main site that weren't book reviews. They were pegged to circulating "discourse," like my Sunday Substack posts today. I discontinued the practice back then, however, because it clashed with the site design! Anyway, I wrote one of those about Sade. I repost it below the line, not having updated my views, though maybe someday I will.

_______________________________

Mitchell Abidor reflects on “Reading Sade in the Age of Epstein,” with a useful history of the notorious author’s welcome reception by the 20th-century intelligentsia:

Then, in the aftermath of World War II, there was an extraordinary explosion of analyses of Sade. Pierre Klossowski, in his 1947 Sade, mon prochain, claimed that Sade was a man deeply influenced by Christian mystics. In a 1951 article in Les Temps modernes, Simone de Beauvoir famously asked: “Must We Burn Sade?” Answering in the negative, Beauvoir was not reticent in pointing out the flaws and contradictions of Sadeian thought. Warning against a “too easy sympathy” for him, she wrote, “it is my unhappiness he wants; my subjection and my death.” Still, she concluded by enlisting him in the Existentialist cause, saying that: “He forces us to put in question the essential problem that haunts this time in other forms: the true relationship between man and man.”

I will confess I’ve never finished anything by Sade, though I’ve probably read about 200 non-sequential pages by him, enough to get the flavor. I took two graduate seminars on Enlightenment literature and philosophy; in one, I was assigned (and did read) excerpts from 120 Days of Sodom, and in the other I was assigned all of Justine, or The Misfortunes of Virtue, but in a scholarly lapse I quit that one at the halfway point, having by then gotten the message.

Did I get the message? Faking it in the seminar room—I had no idea whether I was saying something odd or reinventing the wheel—I suggested it was a parody of Rousseau’s Nouvelle Héloïse, which we’d discussed earlier in the semester. The professor nodded sagely, as if I’d made a worthwhile claim, so I will take that as confirmation. This was a decade before what Abidor, with journalistic Hegelianism, calls “the age of #MeToo and Jeffrey Epstein,” so the seminar at large seemed more or less delighted by Sade’s sexual assault on Rousseau’s Romanticism (which, by the way, I also hated—scorning the Continentals, I wrote my final essay on Laurence Sterne and Ignatius Sancho, ribald authors of a more humanistic mentality).

Later, I dutifully read Adorno and Horkheimer, who—if I got their message—ambivalently praise Sade for revealing the secret underside of the Enlightenment, the hidden truth of bourgeois morality. I also read Roger Shattuck’s chapter on “The Divine Marquis” in Forbidden Knowledge: From Prometheus to Pornography, but found that piece disappointing. Shattuck effectively rebuts the Sadeophile French modernists and poststructuralists by juxtaposing their grandly philosophical advocacy of Sade with his texts’ grisly reality. Then Shattuck tries to argue for Sade as a dangerous author by finding among his admirers not only the likes of Barthes and Bataille but also Ian Brady and Ted Bundy.

But in a book querying limits to knowledge and indeed to free speech, focusing on a pornographer, even a major one, seems like a failure of nerve. A handful of disturbed people might have read Sade before committing crimes on unfortunate individuals; on the other hand, the perpetrators of countless pogroms and genocides and mass murders worldwide found inspiration where else but in the Bible, while Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot studied not Sade but Marx. (Examples could be multiplied among the world’s religious scriptures and political programs.) I would have devoted a chapter on dangerous literature that perhaps ought to be forbidden—though I certainly don’t think any literature should be forbidden, at least legally—on the latter texts instead of on any kind of pornography, whose influence is by its nature more self-limiting than the effect of texts advertising themselves as universally salvific. The postmodernists, despite their sometimes reckless libertinism, had a point about that. Shattuck decides against censoring Sade, it should be noted, but advocates instead “that we should label his writings carefully: potential poison, polluting to our moral and mental environment.”

But intelligence and sensibility—not to mention limited time—demand standards above mere contrariness, or else we’ll be wasting our lives on trash produced only to provoke the pious, an unworthy goal. Sade wins undeserved readers only because he is, in some sense, or for some people, forbidden, despite his academic celebrants. So we shouldn’t burn Sade; we should ignore him. We should ignore him because his fiction and his thought are without interest. Elaborate sexual geometries illustrating fetishes not one’s own, without persons or plots to care about—who needs it? (For more on the boring nature of transgressive literature, see my pieces on Ballard and Bataille.)

As for the philosophy, it is three words long and requires no elaboration: might makes right. A thought so crude does not reveal the terminus of the Enlightenment by abstracting into cold formalism the Enlightened belief in a rational social order, as if that order’s contents did not matter; nor does it help us to understand the Enlightenment’s underside, because it is itself too one-dimensional to count as an instance of the irrational at large, as if one could only be a robot or a rapist. There’s more insight into these psycho-political conundrums on one page of Frankenstein or Hawthorne’s short stories or even Grant Morrison’s comic-book commentaries on Sade than in anything I’ve read by the man himself.

2 notes

·

View notes