#saskatchewan history

Text

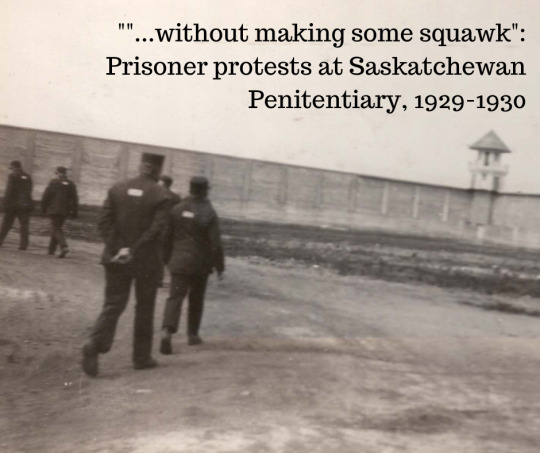

On November 14, 1929, a serious prison strike nearly broke out at the Saskatchewan Penitentiary in Prince Albert. Only by the narrowest of chances was the plot discovered by staff and the strike averted. The strike leaders were two convicts, Ashton and Jones, who referred to themselves in furtive notes as “sweethearts” and “lovers” - they dreamed of escaping to be together. Two hatchet-men from Ottawa were sent to clean up, senior officers of the penitentiary were dismissed, and the whole affair hushed up, save for a few stories in the newspapers. This is part of my rambling, fully informal, draft attempts to understand the origins and course and impact of the 1930s ‘convict revolt’ in Canada, and other issues related to criminality and incarceration Canadian history. (More here.)

Saskatchewan Penitentiary was, at the time, the newest federal penitentiary in Canada. Opened in 1911, to replace the territorial jail at Regina, parts of it were still under construction in 1929. UBC penologist C. W. Topping praised Sask. Pen as “the finest in the Dominion,” with supposedly ‘modern’ features in the cell-block and workshops, including an up-to-date brick factory that produced for federal buildings in the Prairies. Discipline and the organization of staff and inmates was functionally the same as everywhere else in Canada, however: forced labour, the silence system, limited privileges and entertainments, a semi-military staff force, and an isolated location far from major population centres.

The majority of inmates were sentenced from Saskatchewan and Alberta, but throughout the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, Saskatchewan Penitentiary was used as an overflow facility from overcrowded Eastern prisons. In April 1929, dozens of mostly malcontent prisoners were transferred from Kingston Penitentiary. A “row” was expected with these men, but they were not closely watched or segregated from the main population. In November 1929, there were 430 prisoners at Saskatchewan Penitentiary – almost 60 were from Kingston.

The staff at Saskatchewan Penitentiary were warned on the morning of November 14, 1929, by a ‘stool pigeon’ that all work crews (called gangs) would refuse to leave their places of work “until all their demands were met with.” The stool pigeon had no idea who the ringleaders were or the demands, but the Deputy Warden, Robert Wyllie, ordered his officers to keep “a sharp lookout” for suspicious actions. Over 70 prisoners were working outside the walls in two large groups - building a road and laying sewage pipe - and they were supposed to be the epicentre of the strike. Indeed, the whole day of the 14th staff had observed them talking and passing hand gestures. Other warnings came in throughout the day, so Wyllie ordered the penitentiary locked down and the next day interviewed several inmates at random who confessed they had no idea how word about the strike leaked out. For reasons we’ll get into, they were "amazed at being locked in their cells" and surprised by the swift reaction from the Deputy Warden. During the morning of the 15th, one man named Ford was strapped 24 times for attempting to incite a disturbance in his cell block. Noise and shouting echoed throughout the ranges.

Prisoners working on a building foundation at Saskatchewan Penitentiary, c. 1927

In a state of growing panic, Wyllie first phoned Warden W. J. McLeod, on medical leave since September and so sick he could barely answer the phone. Wyllie then telegraphed Ottawa in a vague way, indicating a “serious situation” and asking for someone to come and take charge. Unsure of what was going on, the Superintendent of Penitentiaries, W. St. Pierre Hughes, dispatched five trusted officers from Manitoba Penitentiary, summoned the nearest RCMP detachment, and ordered his personal hatchet-man, Inspector of Penitentiaries E. R. Jackson, to proceed to Prince Albert and take charge. Jackson would be accompanied by R. M. Allan, Structural Engineer, who had worked at Saskatchewan Penitentiary for a decade in the 1910s and "who knew the prison from long experience."

Almost everything in the historical record about this episode comes from Jackson and Allan’s investigation. Their personalities and prerogatives colour completely the available accounts. They were not great record keepers. They were, like many civil servants of the era, bitchy gossips. Both men were known as severe disciplinarians. Jackson, though only appointed as an Inspector in 1924, had become an indispensable figure to Superintendent Hughes. Jackson would be sent to institutions that Hughes viewed as insufficiently following his regulations, or where inmate unrest posed a problem. Jackson was sent to handle a riot at St. Vincent de Paul Penitentiary in December 1925, ordering a brutal round of lashings against accused agitators. He headed the British Columbia Penitentiary for a year and a half when Hughes fired the warden on spurious ground.

It was at B.C. Pen that Jackson met Allan, then the Chief Industrial Officer, and the two would work together closely not just at Prince Albert but also in the construction and opening of Collin’s Bay Penitentiary in Kingston. Jackson also was acting warden at Kingston Penitentiary in summer 1930. One KP lifer testified in 1932 that Jackson was “a mean son of a bitch” who ordered draconian punishments for relatively minor offences. Allan would himself become warden of Kingston Penitentiary in mid-1934, and held that position until 1954.

In short, these were not men sympathetic to prison officers they viewed as incompetent or remotely curious about inmate complaints. Their investigation was about establishing blame and getting things back to ‘normal.’ They concurred with Hughes that "men never rebel where there is a tight grip retained of them by management." There is some truth to this, as sociologist Bert Useem has repeatedly argued in his work on American prison riots: a ruthless but effective and well organized prison staff is likely to stop even the best organized prisoner protest.

In a strictly hierarchical, patrimonial system like an early 20th century penitentiary, where all authority rests with a few men at the top, failures of leadership are often critical. This is a factor often overlooked in popular and academic histories of prisoner resistance and riots (rightly so, perhaps, as we should focus on the actions of the incarcerated, nor their jailers). Of course, strikes and riots in prisons, as elsewhere, never just happen – as Hughes himself noted, this “must have been developing for sometime - [revolts] never occur in a day or two."

This photo shows the chief officers involved in this event. From left to right: Saskatchewan Penitentiary Deputy Warden R. Wyllie and Warden W. J. Macleod, Superintendent of Penitentiaries W. S. Hughes, Accountant G. Dillon, Inspector of Penitentiaries E. R. Jackson.

Jackson quickly fixed blamed on Deputy Warden Wyllie. They were "very much surprised by the lack of initiative" of Wyllie, who seemed to have been cowed by the fifty men working on the outside that had tried to strike. This despite the presence of almost a dozen armed officers nearby! Wyllie had had a nervous breakdown from stress, and had allowed, in Jackson’s eyes, a “lack of efficiency and discipline” to pervade the prison. He was "indecisive" in giving punishments at Warden’s Court, causing “the inmates to gloat over and ridicule the officers…" Inmates charged with fighting, insolence, or swearing at officers were warned or reprimanded, the least severe punishment for such severe infractions of the rules. Several officers felt that “there was no use of reporting the inmates” and so they "closed their eyes to a lot of infractions." Another officer thought that since September 1929 "inmates had became cocky … would laugh in the my face and...tell me to report him when he liked...for it would do no good." This situation was very similar to Kingston Penitentiary before the riot in October 1932, and, indeed, typified the crisis of the 1970s in federal prisons as well.

The November 14-15 disturbance was actually not the first strike episode at Saskatchewan Penitentiary that year. There had been unrest or talk of strikes among the prisoners since early September, with a general atmosphere of defiance and mockery of authorities. Many inmates resisted by going “through the motion of working" but not actually completing tasks. There had been a work refusal in late September, and two other strikes or work refusals in the middle of October. In these cases Wyllie intervened personally, but did not investigate, punish the strikers, or rectify the situation. There are not even reports on file about these events, and the record of reports against inmates for violating rules bears out this feeling that prisoners would “have their own way” and no ‘effective’ action would be taken against their rebellions. That is, effective by the standards of guards, who expected their commands to be obeyed absolutely.

Few demands were discovered – or least Jackson did not think the ones he turned up were worth elaborating on. There seemed to have been general opposition to the Steward's department – the “grub” was satisfactory, but apparently not distributed fairly, according to the inmates. The Steward and Deputy Warden had allowed inmates to place “special instructions” for their meals, and they would shout out their orders like they were at a diner, or exchanged their tickets to swap meals. The queued, single file, food line, with no talking and the same meal for everyone, had disappeared, and restoring this system was Jackson’s first act when he took over. Of course, food in prisoner protests stands in for more than just a meal, while also representing a very basic need that is one of the few things to look forward to during days of monotonous labour.

Much of the unrest centred on certain work crews, whose officers were resented, and communication with family, better work arrangements, socializing, access to newspapers, all are mentioned in passing in the investigation files. The “Kingston boys” were also the loudest supporters or organizers of the strikes, and they apparently resented being exiled to Saskatchewan. At least one inmate, Radke, told other inmates he wanted the strike to force a Royal Commission to investigate the prison. This kind of demand would be repeated again and again in 1932 and 1933 during prison riots across Canada.

Cell block in 1930 at Saskatchewan Penitentiary. The beds in the corridors are due to severe overcrowding.

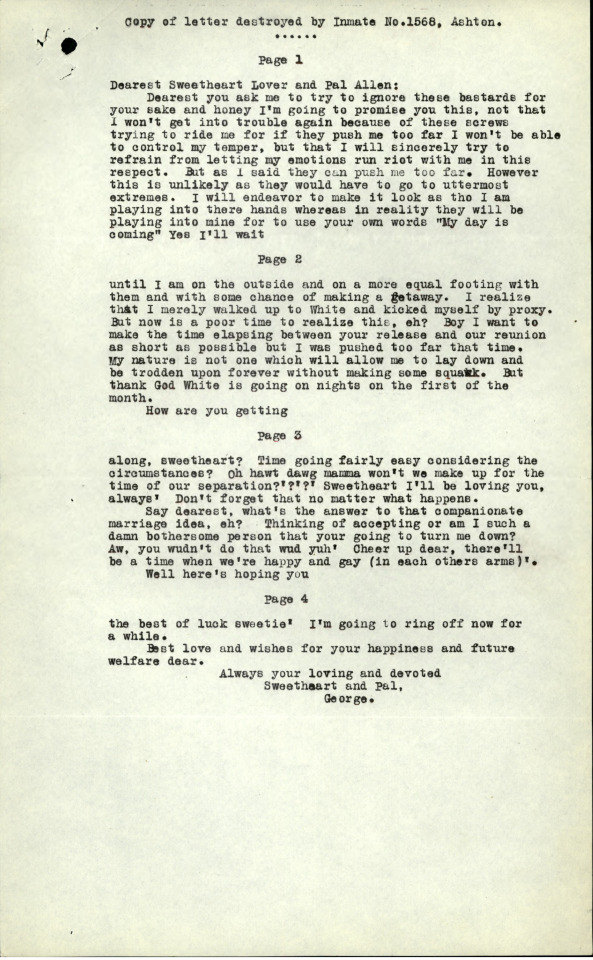

George Ashton was singled out as one of the organizers of the abortive strike. Serving a term for armed robbery, he was one of the Kingston transfers. On November 15, 1929, he was caught trying to throw a letter away. This letter is addressed to another inmate who he had hoped to escape with. Ashton, "a troublesome, Smart Alec kid,” was sentenced to be shackled for ten days to his cell bars and to spend sixty days in isolation. Typical of Jackson’s more ‘effective’ regime.

Ashton’s note was addressed to his 'Pal', Allen, alias Bertram Allen Jones. Both worked in different work crews labouring outside the walls. Ashton’s letter to Jones identifies him as his sweetheart and lover, and promised that "he'll not get into trouble again because of these screws...I will sincerely try to refrain from letting my emotions run riot....My nature is not one which will allow me to lay down and be trodden upon forever without making some squawk." Ashton indicated he wanted to "make the time elapsing between your release and our reunion as sort as possible." He asked how Jones’ time was going, and ended by expressing his longing and desire to be with Jones:

"OH hawt dawg mamma won't we make up for the time of our separation??? Sweetheart I'll be loving you..." Say what's the answer to that companionate [sic] marriage idea? Thinking of accepting or am I such a damn bothersome person that your going to turn me down?.....there'll be a time when we're happy and gay (in each other arms).”

This was apparently one of many letters the two had exchanged, and contrary to the usual arrangements of wolves and punks in early 20th century prisons, where older men ‘protect’ younger inmates, often to extract sexual favours, this was apparently a consensual and sincere relationship. Not as uncommon as might be expected, of course, but it’s unusual to find such boldly expressed desire and love in this period of the archival record. Of course, Hughes thought this letter confirmed that Ashton was "a low bestial sort." Jones was identified as one of the other ringleaders, and he and Ashton had been seen talking to each other and making hand gestures several times in the months leading up to their strike attempt.

Who these men were and what happened to them after their time in prison I don’t know, yet.

Transcript of Ashton's letter to Jones, the only part of their correspondence that survives today

Inspector Jackson stayed in charge for another two months at Saskatchewan Penitentiary. An attempt to start on insurrection on November 20, 1929, was broken by strapping four of the leaders: “since then the Prison is absolutely quiet." Always full of himself, Jackson included letters of thanks from officers who praised his leadership, including the prison doctor: "We were drifting badly, discipline had practically ceased...now we are back and a Prison once more." He felt satisfied that retiring Wyllie and Warden Macleod had solved the problem, and left Allan in charge starting in mid-December 1929.

While I have no doubt that Deputy Warden Wyllie was responsible for the growth of an inmate strike movement, I don’t believe it is purely a case of his incompetence allowing inmates to organize. Rather, he proved himself to be an open door to prisoners already planning protests, and his inability to act with the severity expected by prisoners and staff alike encouraged further protests. Like a lot of federal civil servants, Wyllie was likely promoted above his abilities, with his loyalty to Hughes, seniority, indispensability to superior officers, and local influence helping to further his career. This was Jackson’s trajectory as well, ironically – once Hughes retired in early 1932, Jackson was on the outs, transferred to clerical duties in Ottawa, and he was dismissed in December 1932 as part of the purge initiated of penitentiary officers by the new Superintendent.

Additionally, it is clear to me that the issues at Saskatchewan Penitentiary extended beyond one officer – and indeed blaming Wyllie absolved a bunch of other officers of corruption and incompetence. Serious issues in the Hospital, Kitchen, School, and Workshops, were identified by Allan when he took over, with trafficking and contraband in cigarette papers, pipes, lighters, smuggled cigarettes, photographs and letters widespread. The Boiler House, where “considerable contraband has been located,” had seven inmate workers, who laboured "without direct supervision...” These men resented the crackdown and refused to work in February 1930 – which revealed to Allan the danger of allowing inmates to have full control of the power plant of the penitentiary.

Allan fired the officer in charge of the boiler house, the hospital overseer, the storekeeper, and reprimanded other officers for failing to confiscate contraband items. Fake keys were found throughout the prison, likely to be used in escapes or smuggling. Inmates had been allowed for years to order magazines direct from the publisher – and did not have them passed through the censor. Another mass strike was attempted in January 1930, apparently to protest Allan cracking down on these deviations from the regulations. As always, it should be recalled that what the officers saw as corruption or smuggling against regulations were all activities that made 'doing time' easier.

Why care about this episode, beyond some of the points I’ve already raised? One aspect of historical study I am most interested in are the precursors to a major event - the struggles, organizing, movements, victories and defeats that (sometimes with hindsight, sometimes without) shape a more influential and decisive event. This is especially difficult when writing the history of prisoner resistance, which often appears a discontinuous history, full of gaps and seemingly sudden flare-ups. The 1930s were a decade of prison riots, strikes, escapes and protests in federal and provincial prisons, but obviously these did not arise from nothing. The 1929 strike attempt at Saskatchewan Penitentiary is a transitional event – similar to earlier strikes and protests going back to the late 19th century, but occurring at the very start of the Great Depression, a premonition of things to come.

#prince albert penitentiary#prince albert#prison strike#prison riot#convict revolt#prisoner organzing#prison administration#prison management#causes of prison riots#my writing#dominion penitentiaries#saskatchewan history#queer history#history of homosexuality in canada#great depression in canada#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

A couple weary travellers hitch a ride outside Moosejaw, Saskatchewan.

Canada

1972

#vintage camping#campfire light#canada#saskatchewan#moosejaw#hitchhiking#hippies#history#camping#road trips#1970s

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

1994.

Dan Aykroyd: BANNED IN SASKATCHEWAN.

#dan aykroyd#rosie o'donnell#censorship#saskatchewan#canada#canadian#garry marshall#history of canadian comedy

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brothers Charlie and Harold Dyer, sons of William and Rebecca Dyer of Carlyle, Saskatchewan. Both died in service. Charlie was killed in August 1916, aged 24. Harold a few months later in October, aged 19.

#saskatchewan#world war one#world war 1#british army#ww1#wwi#great war#The Great War#The First World War#photography#historical photography#history#historical photos#British history#military history#canadian history#1918#1917#1916#siberia

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

WARNING: This article includes distressing details.

A Saskatchewan First Nation has found what it believes to be dozens of graves in its initial findings from a radar search in and around the cemetery at a former residential school.

English River First Nation says its ground-penetrating radar search that began two years ago has found 83 potential graves or areas of interest, some of which were unmarked, at the former Beauval Indian Residential School's cemetery.

A dozen of the potential graves average about 2.5 feet in length, which Chief Jenny Wolverine said is consistent with the burial of infants "and in line with several witness accounts of infant births, and subsequent deaths, by survivors of this school."

Most of the graves appear to be child-sized. [...]

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @politicsofcanada

#cdnpoli#Indigenous persecution#Indigenous politics#genocide#residential schools#canadian history#colonialism#English River Nation#Saskatchewan

100 notes

·

View notes

Video

Gull Lake SK Friday June 26th 1981 1350MDT by bill hooper

Via Flickr:

Eastbound passes the Gull Lake elevators on the Maple Creerk Subdivision in southwest Saskatchewan

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

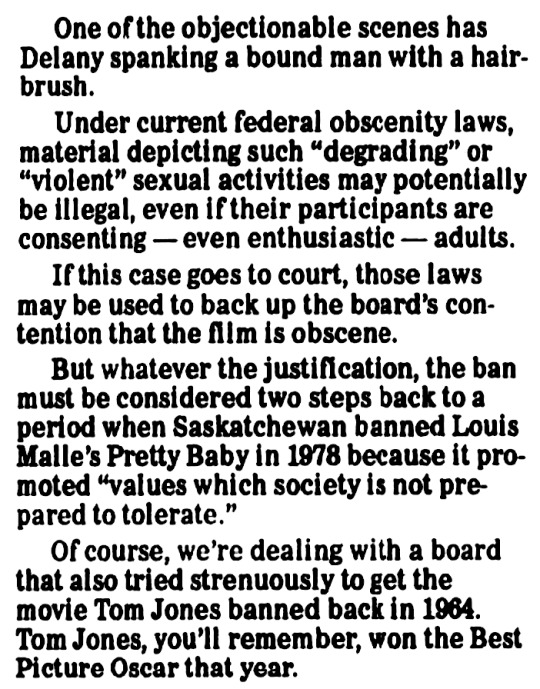

st cassian chamber choir yearbook, official promotional media from the website (2011-2013)

↓ extras below

yearbook page + png

clicking on the image leads to an interactive flash flip book, however im unable to play the site :( please feel free to dm any findings!

#ride the cyclone#ocean o'connell rosenberg#constance blackwood#noel gruber#mischa bachinski#ricky potts#jane doe#ocean was a LIBRA ???? that made so much sense. good on her for liking karl marx i suppose. the “first hear me out” in saskatchewan history#also “aka bad egg” lmfaoo he totally threw a fit to get his youtube featured#also the yearbook png is so Cool im geeking#img#old rtc#my media

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

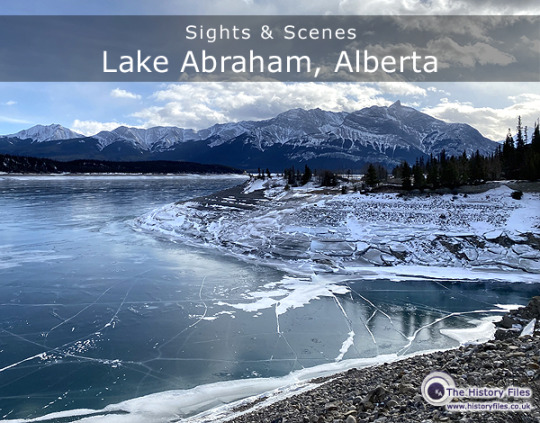

Lake Abraham, Alberta: this lake in Alberta was created in 1972 as part of the process of building the Bighorn Dam, being added along the upper course of the North Saskatchewan River.

#history#historyfiles#lake abraham#abraham lake#alberta#canada#sights and scenes#photos#nature photography#nature beauty#artificial lake#rocky mountains#canadian rockies#north saskatchewan river#bighorn dam

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first transcontinental passenger train departed from Montreal’s Dalhousie Station, located at Berri Street and Notre Dame Street at 8 pm on 28 June 1886, and arrived at Port Moody at noon on 4 July 1886.

#Toronto Railway Museum#Gare du Palais by Harry Edward Prindle#Quebec City#Québec#Windsor Station#Montréal#Toronto#travel#original photography#vacation#tourist attraction#landmark#first transcontinental passenger train#28 June 1886#anniversary#Canadian history#Union Station#Moose Jaw#Saskatchewan#Craigellachie Last Spike Cairn#Craigellachie#British Columbia#engineering#technology

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sylvia Fedoruk

youtube

Medical physicist Sylvia Fedoruk was born in 1927 in Canora, Saskatchewan. Fedoruk conducted groundbreaking research on the medical use of radioactive isotopes, and helped develop the first cobalt-60 therapy unit, which became widely used to treat cancer. She was a Professor of Oncology at the University of Saskatchewan, and chief medical physicist of the Saskatchewan Cancer Foundation. In 1988, Fedoruk became the first woman to serve as Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan.

Sylvia Fedoruk died in 2012 at the age of 85.

#science#stem#women in stem#medicine#women in medicine#canada#canadian#saskatchewan#women's history#Youtube

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Legacy of Saskatchewan’s Most Controversial—and Impactful—Artist Program

The infamous Emma Lake Artists’ Workshops were ad hoc, low budget, and falling apart. They also reimagined the possibilities of art

Among the guest mentors were some of the most radical — and polarizing — figures in modern art, including Clement Greenberg and Barnett Newman. They inspired locals to consider new techniques, new styles. Some artists took to the challenge, while others bristled at the presumption of an outsider deciding how they should approach their work. According to some critics, these outsider voices even remade the region’s style in their own image. The debate continues, but many can agree that for the nearly six decades it survived, Emma Lake succeeded in creating as much conflict as history.

Read more at thewalrus.ca.

Artwork by Kenneth Lochhead and Reta Cowley. Full credits at source.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

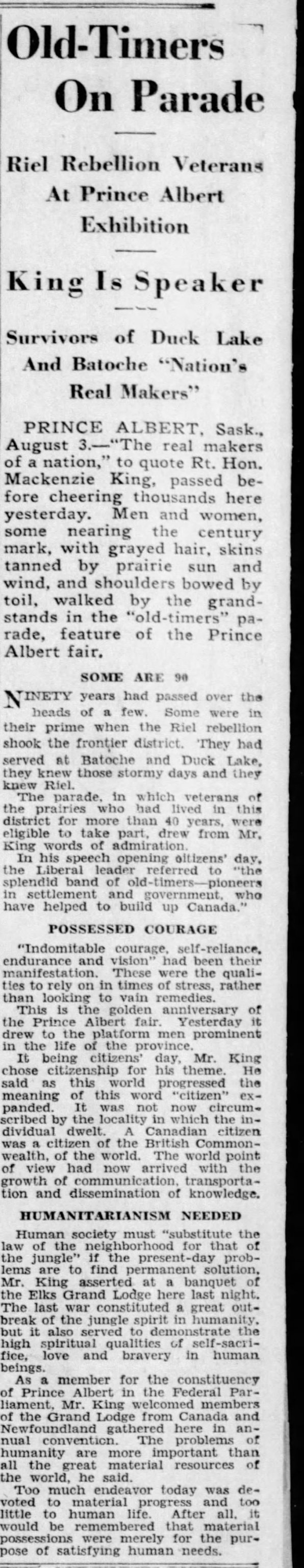

"Old-Timers On Parade," Border Cities Star. August 3, 1933. Page 10.

----

Riel Rebellion Veterans At Prince Albert Exhibition

----

King Is Speaker

----

Survivors of Duck Lake And Batoche "Nation's Real Makers"

---

PRINCE ALBERT, Sask., August 3. - "The real makers of a nation," to quote Rt. Hon. Mackenzie King, passed before cheering thousands here yesterday. Men and women, some nearing the century mark, with grayed hair, skins tanned by prairie sun and wind, and shoulders bowed by toil, walked by the grandstands in the "old-timers" parade, feature of the Prince Albert fair.

SOME ARE 90

NINETY years had passed over the heads of a few. Some were in their prime when the Riel rebellion shook the frontier district. They had served at Batoche and Duck Lake, they knew those stormy days and they knew Riel.

The parade, in which veterans of the prairies who had lived in this district for more than 40 years, were eligible to take part, drew from Mr. King words of admiration. In his speech opening citizens' day, the Liberal leader referred to "the splendid band of old-timers-pioneers in settlement and government, who have helped to build up Canada."

POSSESSED COURAGE

"Indomitable courage, self-reliance, endurance and vision" had been their manifestation. These were the qualities to rely on in times of stress, rather than looking to vain remedies.

This is the golden anniversary of the Prince Albert fair. Yesterday it drew to the platform men prominent in the life of the province.

It being citizens' day, Mr. King chose citizenship for his theme. He said as this world progressed the meaning of this word "citizen" expanded. It was not now circumscribed by the locality in which the individual dwelt. A Canadian citizen was a citizen of the British Commonwealth, of the world. The world point of view had now arrived with the growth of communication, transportation and dissemination of knowledge.

HUMANITARIANISM NEEDED

Human society must "substitute the law of the neighborhood for that of the jungle" if the present-day problems are to find permanent solution, Mr. King asserted at a banquet of the Elks Grand Lodge here last night. The last war constituted a great out- break of the jungle spirit in humanity. but it also served to demonstrate the high spiritual qualities of self-sacrifice, love and bravery in humanbeings.

As a member for the constituency of Prince Albert, in the Federal Parliament, Mr. King welcomed members of the Grand Lodge from Canada and Newfoundland gathered here in annual convention. The problems of humanity are more important than all the great material resources of the world, he said.

Too much endeavor today was devoted to material progress and too little to human life. After all, it would be remembered that material possessions were merely for the purpose of satisfying human needs.

#prince albert#saskatchewan history#riel rebellion#northwest resistance#canadian veterans#settler colonialism in canada#empire building#william lyon mackenzie king#politics of chaos#canadian history#liberal party of canada#member of parliament#fall fair#great depression in canada#canadian patriotism

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Camping roadside near the Trans Canada Highway.

Qu'Appelle Valley, Sakatchewan

1954

#vintage camping#campfire light#saskatchewan#road trips#qu'appelle valley#history#camping#hiking#outdoors

289 notes

·

View notes

Text

1965.

Canada versus First Nations peoples.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

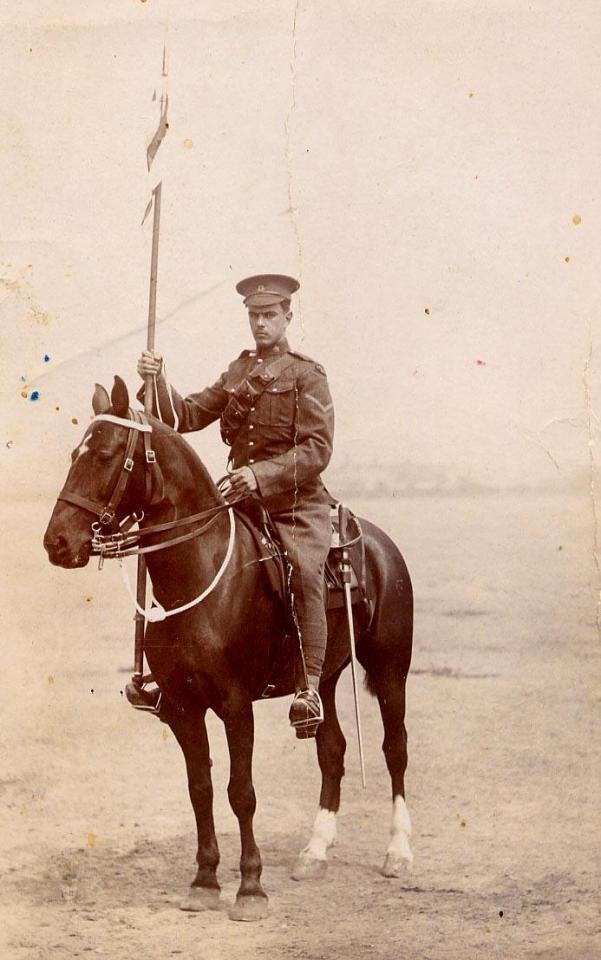

Cuthbert King Matthews was born in London, England in June, 1892. He emigrated to Canada at age nineteen, where he began homesteading in Saskatchewan. Matthews enlisted in Winnipeg, Manitoba in March, 1916. He served overseas in Belgium and France until wounded in August, 1918 and returned to Canada in 1919.

#WWI#WW1#The First World War#The Great War#1918#1916#1917#historical photos#history#photos#war#remembrance day#war horse#saskatchewan#belgium#veterans

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 No. 5 “Marlborough Evolution”

Acrylic on Canvas, 20X24 inches

#aleksi draws#aleksi ann#aleksiann#painting#artists on tumblr#acrylic#art#acrylic painting#architecture#North Battleford#Marlborough hotel#Saskatchewan#Canada#Time Machine#hotel#history#2023

12 notes

·

View notes