#source: isabella roberts

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

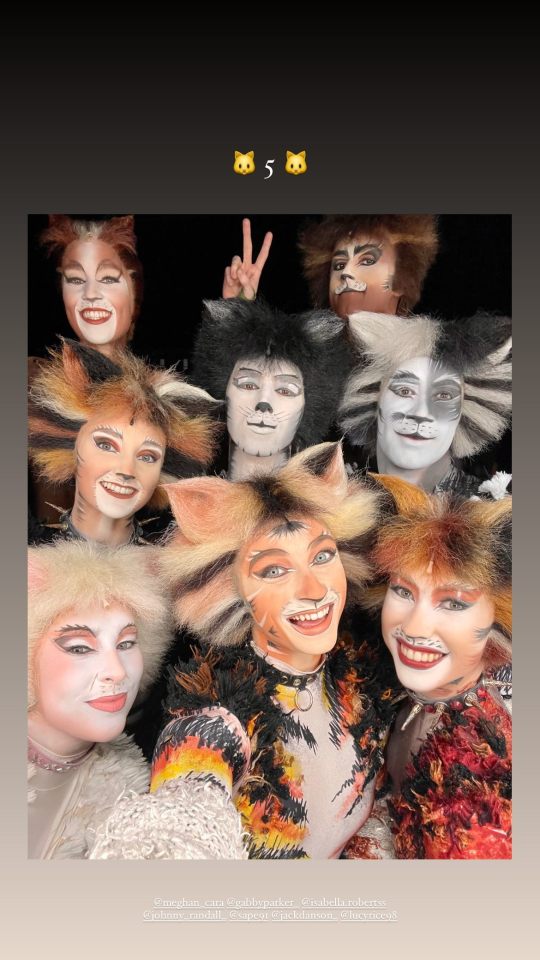

instagram story: Aug 10, 2023

#cats korea tour 2022#cats taiwan extension 2023#source: isabella roberts#source: saverio pescucci#isabella roberts#victoria (cats)#victoria the white cat#gabrielle parker#jemima (cats)#saverio pescucci#alonzo (cats)#meghan peploe williams#cassandra (cats)#backstage cats#please stop counting down shows you make me sad#closing cats countdowns skip the queue because i'm sad

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

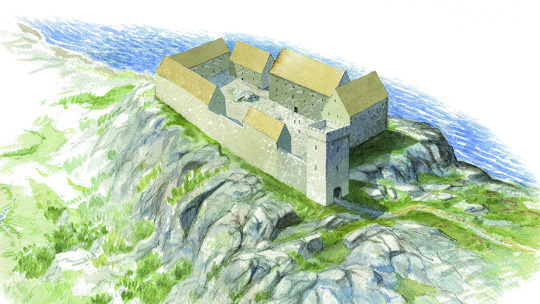

Devizes Castle - Wiltshire County - England

This image shows the Victorian "Castle" built in the 1800's the original Castle lies underneath the present structure being built in around 1080 as an early Norman motte and bailey with wooden pallisade and tower, built by Osmund, Bishop of Salisbury. It is first mentioned in 1106, when Robert of Normandy was imprisoned in it.

The original structure burned down in 1113 and was rebuilt in stone by Roger, Bishop of Salisbury, by 1120. In that era, it was said (by an unknown source) that it was the most beautiful fortress in Europe. He occupied it under Henry I and the castle was claimed by Stephen, King of England in the 1130s; Empress Matilda once took it but returned the castle to King Stephen when he threatened to kill her son. Matilda later reclaimed it and held the castle for some time. The property was owned by the Crown until the 17th century. It was used as a prison by Henry II and Henry III. It went on to become the property of Henry VIII who gifted it to his wife Catherine of Aragon and then reclaimed it after their divorce.

Important prisoners were held at the castle, including (from 1106) Robert Curthose, eldest son of William the Conqueror, and (in 1232) Hubert de Burgh. Also, in 1206, John, King of England held his second wife Isabella here as a prisoner.

In 1643, during the Civil War, the castle was occupied by Royalist troops and besieged by Parliamentary forces under Sir William Waller. However, three days later in the Battle of Roundway Down, Waller's army was routed by Royalist forces. At that time, Devizes was a base for Lord Hopton's forces. The castle and town remained in Royalist hands under the military governorship of Sir Charles Lloyd, the King's Chief Engineer, who defended the town against repeated attacks and bombardments by the Parliamentarians. In September 1645, Cromwell with large forces and heavy artillery invaded the town and laid siege to the castle, which surrendered after a bombardment by the 5,000 man Parliamentary army. In May 1648 the castle was dismantled following a Parliamentary Order, a process known as slighting. The stone used for building other local structures.

The remains of original castle (below the current castle) became a scheduled monument in 1953 based on excavations at the site, and is in the care of Historic England

In 1838 the castle lands were acquired by J. N. Tylee who sold them in 1838 to Valentine Leach, a Devizes tradesman. The present castellatedVictorian era 'castle', in a mixture of Neo-Norman and Gothic Revival styles, was designed by Henry Goodridge, an architect from Bath. It was begun about 1840 with a boldly asymmetrical design, and was extended northwards in the 1860s and succeeding decades. The north tower incorporates the remains of a 17th-century brick windmill.

This building is NOT open to the public and is in private hands

Text from Wikipieda

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

The dating sim beef is so silly.

The only people who actually “look” like their movie counterparts are Tedesco and kinda Benítez. Lawrence looks nothing like Ralph Fiennes and Agnes looks absolutely nothing like Isabella Rossellini at all. (Bellini looks vaguely like Tucci but it’s vague). They made Wozniak hotter. Where’s the anger for all the people on Twitter drawing Benítez as white or literally grey??? What’s the issue here?? The art style?? I’m lost on why that’s a problem. They didn’t whitewash him. Adeyemi is dark skinned and handsome!

The Tedesco criticism is always gonna be a criticism and people can have their opinions on that; but it’s interesting to note that the people who seem predominantly obsessed with him are also Muslim/poc. Idk if it’s white-knighting or what but lmao I think it’s just that people think Sergio is a hot old man. (I don’t get it but I respect the gilf enjoyers)

Some people are mad Adeyemi was treated too harshly, and it seems like other people are mad he wasn’t treated harsh enough. Do you all… do you all see how silly and ridiculous that is??

I get that people don’t like his good ending (everyone repentant deserves absolution!! But I’m on the fence if I like him or not) has him in Kabul taking over Benitez’s post; but bishop missionaries aren’t the ones directly aiding the people they serve. (That would be a nurse or a doctor). They’re the ones dealing with the local authorities/managing deliveries/keeping the lights on, which is why it’s dangerous to have that position. They’re the ones whose life is on the line first.

Idk. I feel like this is very much a situation where people are bitching on anon because they don’t have enough courage to say it with their name attached. Are there criticisms? Sure!! I have several! Why is Ray a yandere??? He deserved to be a full blown dating option and I’m mad about the fact he wasn’t. Tremblay and Adeyemi over Ray was certainly a choice!!!

But if you want to have a discussion and not a discourse you have to be willing to start a discussion.

As always in fandom spaces; fanworks are treated more harshly than their source material.

Where’s this energy at Robert Harris for making every single character the most racially stereotyped version of that group??

Why is the African Cardinal the one with a sex scandal who abandoned his kid? Why is the Italian Cardinal the racist fascist Mussolini asshole? Why is the Southeast Asian Cardinal the one treated as a mystic/higher spiritual guide for the white character AND ALSO has some poorly researched bs about gender/sex and the culture surrounding it? Two for one there on racist stereotypes for book Benítez. Great job, Rob.

The flaws are in the original text. If we wanna have a discussion as fans let’s have a discussion!! But to act like a fan project made by like two people for free is somehow more harmful/worse that the original work that got nommed for several Oscars and made millions? Keep that energy for Robert Harris please.

~

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The incredible story of Carlos Diehz, the star of “Conclave” who had never acted in his life.

The director [Edward Berger] wanted someone practically unknown, or little known, for the role of Cardinal Benítez”, says Carlos Diehz. What Edward Berger was looking for was for that newcomer feeling to be felt on and off the set. And so it happened: Ralph Fiennes, Stanley Tucci and John Litgow came up to me to ask me when I started, how I got there, etc.”.

Diehz confesses that, at first, it was overwhelming to think about the idea of working with actors with such long careers as the aforementioned, Isabella Rossellini for example. “But it's been an exercise in constant self-esteem, in trusting the process. And being on the set, it was fantastic to have the support of all of them, to receive their advice”, says the Mexican, who has a couple of moments in the film - a monologue and a dialogue - that are very demanding, but from which he comes out of them with flying colors.

Although he had more than one 'coach' in the process, and several of them recommended him not to look for references and inspirations so as not to “contaminate himself” and fall into imitation, Diehz recognizes that Robert Powell's performance in the remembered miniseries “Jesus of Nazareth” by Franco Zeffirelli helped him a lot to build his character. Two historical figures were also important: St. Francis of Assisi and St. Ignatius of Loyola.

I myself had a spiritual, almost mystical stage when I was 19 or 20 years old,” he says. I thought about going into service, changing the world. I read about the life of St. Francis and St. Ignatius, I got really into it. Until a priest who was my spiritual guide told me, 'Take it easy. Live, finish a career, and then see if this is truly your calling.' And well, 30 years later, with this Benitez character, I think that's the way I would have liked to be if I had followed that path”.

Source

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

On April 1st 1295 Robert Bruce, “The Great Competitor” and grandfather of King Robert the Bruce, died.

Many people make the mistake of thinking that it was the Robert the Bruce that fought for our freedom at Bannockburn that was also one of the men that was up against John Balliol in the “great cause” when Edward I of England chose the successor to Margaret, Maid of Norway, it was his Grandfather the subject of this post. There is a lot of confusion when talking about the family the explanation will become apparent.

The family of Bruce originated from the town of Brus, modern Brix between Cherbourg and Valognes in Normandy and was founded by one particular Norman knight by the name of Robert who came across to England in the wake of the Norman conquest of 1066 and was granted some manors in Yorkshire by William I.

It has to be said that the Bruce family displayed a distinct lack of imagination in the naming of their sons. Having settled on the name Robert they stuck with it through thick and thin down the generations. Hence there are a succession of eight Robert Bruce’s over a period of three centuries and to make matters worse there are four generations of Roberts who each chose a wife named Isabel/Isabella.

You might think that this would be a source of confusion and you would be correct. More than one source gets hopelessly mixed up between Robert Bruce and another and it sometimes seems to be the case that no one is quite clear which Robert Bruce did what.

The second Robert of Bruce was notable for his friendship with David son of Malcolm III, king of Scots, who spent the early part of his life living in England as the Earl of Huntingdon, after his marriage with Matilda, daughter of Waltheof Siwardson and heiress to the estate of Huntingdon.

When David finally became David I, king of Scots, Robert was one of a number of Norman knights invited north to help David knit together the rather disparate group of territories that fell under his rule. Robert was granted the Lordship of Annandale, which was then within the territory of Strathclyde in what later became Dumfriesshire in the south western corner of Scotland.

Having said that nothing was ever black and white in those days and when King David fought the English at the Battle of the Standard in the year 1138 this Robert was on the English side. It was nothing personal but at this point The Bruce family owned land in what is now Yorkshire. To complicate things further by now there was a third Rober and you guessed it, the younger man was fighting on the Scottish side, this is what is known as hedging your bets! This third Robert subsequently lost control of the family land in Yorkshire.

The fourth Robert’s great contribution was to marry Isabel of Scotland the daughter of William the Lion, king of Scots. This was an indication of how important the Bruce family had became within the young kingdom of Scotland, but the marriage achieved an even greater significance in later years, as it was this connection with the Canmore dynasty that was to form the main basis of the claims by this Robert’s great-great-grandson to the throne of Scotland.

The fifth Robert married another Isabel, Isabel of Huntington who was the daughter of David, Earl of Huntington and Matilda of Chester. This David was the son of Henry of Huntington, son of David I of Scotland and Isabel was therefore niece of the aforementioned William the Lion; so yet another connection was made with the House of Canmore.

On to number six, I was going to make a joke about the Prisoner, but perhaps not! This is the Robert who died on this day in 1295. The sixth Robert continued the family tradition and married yet another Isabel, this time Isabel de Clare daughter of Gilbert de Clare and Lady Isabel Marshall which established a connection with the powerful Anglo-Norman de Clare and Marshall families.

This Robert was the first of his line to promote his claim as a candidate for the Scottish throne which became vacant following the death of Queen Margaret in 1290. He wasn’t successful on this occasion but it brought the Bruces right to the forefront of Scottish politics.

The seventh Robert married Marjorie of Carrick (the Countess of Carrick), and by right of his wife thereby obtained the title of Earl of Carrick.

Like his great-great-grandfather, he too fought on the English side against the Scots, this time at the battle of Dunbar in 1296. Although such is the confusion between the various Bruces, others suggest that it was not him but his son Robert the Bruce who did so, which would be doubly ironic.

And the most important one the most well-known is number eight Robert the Bruce who was the great champion of Scottish independence, who was crowned king of Scotland in 1306, defeated Edward II of England at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314, issued the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320, he died in 1329.

And there it ended, Robert broke the long line of Bruces named Robert and named his oldest son David, who became David II of Scotland.

There was another Robert Bruce though, but he was illegitimate to an unknown mother, Sir Robert Bruce, Lord of Liddesdale. He was killed leading a charge at the Battle of Dupplin Moor on 11 August 1332. during the second wars of Independence..

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw a saying that Isabella from France may not have cheated on her?

Hi, yes! The idea that Isabella had an adulterous relationship with Roger Mortimer has been widely accepted by historians, novelists and commentators for some time but contemporary and near-contemporary records do not unambiguously support it. In recent years some historians, such as Seymour Phillips, Michael Evans and Kathryn Warner, have been more cautious about the idea that Isabella and Mortimer did have an affair.

In some contemporary records, we have the report of rumour - The Chronicle of Lanercost claims "there was a liaison suspected between him and the lady queen-mother, as according to public report" while the unreliable Geoffrey le Baker claimed that Isabella was "in the illicit embraces" of Mortimer. Some sources seemed to describe their relationship in the discourse of royal favouritism (similar language is used to describe the relationship between Edward II and Piers Gaveston and Richard II and Robert de Vere). Adam Murimuth claimed Isabella and Mortimer had an "excessive familiarity (nimiam familiaritatem)" and another chronicler described Mortimer as her "amasius" (or lover), which is a term used also to describe Gaveston in relation to Edward. Jean Froissart, writing long after the event, even claimed Isabella fell pregnant with Mortimer's child but there is no other evidence for this claim and it's difficult to see how it could have been kept secret.

There is little support in other contemporary chronicles, which often only mention Mortimer in his less scandalous role of councillor of the queen and as a participant in the rebellion. In some cases, euphemistic language might be employed (the Brut describes Mortimer making himself "wonder priuee" with Isabella and Edward II himself wrote Isabella kept Mortimer's "company within and without house" while the report of a story Edward told of an unnamed queen who was disobedient to her husband and deposed, very likely alluding to Isabella, may also be a veiled reference to Isabella's adultery) but we don't know whether a euphemism was intended and we undoubtedly read it in the context where the idea of an affair has not only been raised but has been so widely accepted.

Basically, the evidence does not universally support the idea that they definitely had an affair, much less that they were brazen about it. It does seem like there were rumours about it and that chroniclers perhaps explained Mortimer's rise to power in the same way they explained Gaveston and the Despensers' rise (on that note: we don't know whether Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger were Edward's lovers - it's certainly possible, perhaps even likely, but there's no way to know).

Warner has also argued that Isabella had too much sense of royal dignity to have an affair with a man of Mortimer's rank and that she was too pious to lie to the Archbishop of Canterbury about her desire to return to Edward - but I don't find these arguments particularly convincing. They're too subjective and are reliant on Warner's idea of what Isabella was "really like" while I believe that we don't and can't know what Isabella was really like to make these type of arguments.

Did Isabella have an affair with Mortimer? We don't know. It's possible she did - there is some supporting evidence for it. But the evidence may only be recording of rumours or slander. Where each person feels about the question probably relies on what they think of the narratives about Isabella's affair with Mortimer and what they think Isabella was "really like".

I don't have a strong opinion either way. I can see the argument for and I can see the argument against, and I think we should be cautious about taking the position that one is absolutely more likely to be true than the other. At a distance of 700 years, we have no way to know who Isabella really was and no way to prove or disprove whether she had sex with Mortimer or not.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Northanger Abbey Readthrough, Ch 10

Oh Isabella Thorpe, you delightful, ridiculous girl. You know if she was just a vacation friend she'd be fine; there are lower standards for vacation friends. Catherine and her would be close for a few weeks, be pen pals for a few months and then totally forget about each other. But no, she has to pull shit like this:

I assure you, my brother is quite in love with you already; and as for Mr. Tilney—but that is a settled thing—even your modesty cannot doubt his attachment now; his coming back to Bath makes it too plain.

Oh great, Thorpe is in love with Catherine. I also love how Mr. Tilney returning to Bath is absolute proof of his love. We will learn quite soon that it had nothing to do with Catherine at all, Henry went ahead to book lodgings.

Isabella "discovers" that she and James have exactly the same tastes, which I suspect was found in exactly the same way that Willoughby "discovered" that Marianne shared all of his:

We soon found out that our tastes were exactly alike in preferring the country to every other place; really, our opinions were so exactly the same, it was quite ridiculous!

Their taste was strikingly alike. The same books, the same passages were idolized by each—or if any difference appeared, any objection arose, it lasted no longer than till the force of her arguments and the brightness of her eyes could be displayed. He acquiesced in all her decisions, caught all her enthusiasm; and long before his visit concluded, they conversed with the familiarity of a long-established acquaintance. Sense & Sensibility, Ch 10

This also seems to be how Lucy Steele won over Robert Ferrars and how Caroline Bingley is attempting to secure Darcy. James is certainly falling for it, so it must work some of the time. There you go, A+ dating advice, just like everything they like!

Isabella claiming that, "I know you better than you know yourself" to Catherine seems to be grating our heroine a little. Of course, despite massive hints Catherine still doesn't seem to get that Isabella is gunning for James, but Catherine also dislikes being assumed to be improper. We see that Catherine does try very hard to do the right thing, though Mrs. Allen isn't the best source of guidance.

Catherine becomes a third wheel:

They were always engaged in some sentimental discussion or lively dispute, but their sentiment was conveyed in such whispering voices, and their vivacity attended with so much laughter, that though Catherine’s supporting opinion was not unfrequently called for by one or the other, she was never able to give any, from not having heard a word of the subject.

before running off to speak to Miss Tilney.

“How well your brother dances!” was an artless exclamation of Catherine’s towards the close of their conversation, which at once surprised and amused her companion.

"Artless" comes up a lot in Austen's works, and it's generally a good thing. It's like the opposite of conniving. Here are some examples:

The next morning brought another short note from Marianne—still affectionate, open, artless, confiding—everything that could make my conduct most hateful. - Willoughby, Sense & Sensibility

Fanny’s feelings on the occasion were such as she believed herself incapable of expressing; but her countenance and a few artless words fully conveyed all their gratitude and delight, and her cousin began to find her an interesting object.

Mrs. Price’s manners were also at their best. Warmed by the sight of such a friend to her son, and regulated by the wish of appearing to advantage before him, she was overflowing with gratitude—artless, maternal gratitude—which could not be unpleasing. -Mansfield Park

She was not struck by any thing remarkably clever in Miss Smith’s conversation, but she found her altogether very engaging—not inconveniently shy, not unwilling to talk—and yet so far from pushing, shewing so proper and becoming a deference, seeming so pleasantly grateful for being admitted to Hartfield, and so artlessly impressed by the appearance of every thing in so superior a style to what she had been used to, that she must have good sense, and deserve encouragement. An unpretending, single-minded, artless girl—infinitely to be preferred by any man of sense and taste to such a woman as Mrs. Elton. -Emma

(There are several more quotations noting that Harriet is artless, from both Emma and Mr. Knightley)

Artless means without guile or deception, and it seems like Miss Tilney picks that up about Catherine right away. We readers of course know that Catherine is extremely honest, almost to a fault. Because not only does she shy away from lying, she also wants the truth to be known, which is why she is so quick to explain why she had to turn down Mr. Tilney for a dance. This will come up later...

This civility was duly returned; and they parted—on Miss Tilney’s side with some knowledge of her new acquaintance’s feelings, and on Catherine’s, without the smallest consciousness of having explained them.

Awww, Eleanor already knows that Catherine is crushing hard!

A great quote:

Woman is fine for her own satisfaction alone.

I love that Catherine's old aunt read her a lecture on how she shouldn't be vain about her clothes. It is funny though, Henry Tilney may be the rare type of man you could impress with a good muslin.

Catherine then tries very hard to avoid John Thorpe and hopes that Henry Tilney will again ask her to dance:

Every young lady may feel for my heroine in this critical moment, for every young lady has at some time or other known the same agitation. All have been, or at least all have believed themselves to be, in danger from the pursuit of someone whom they wished to avoid; and all have been anxious for the attentions of someone whom they wished to please.

Then when Henry does ask her, "With what sparkling eyes and ready motion she granted his request, and with how pleasing a flutter of heart she went with him to the set, may be easily imagined" It can be easily imagined! Catherine is just so cute and uncomplicated in her love.

John Thorpe is hilarious, having seen that he has lost Catherine for the dance, he tries to sell Henry Tilney a horse (!?!?). The man has way too many schemes to keep track of.

Now we get into the similarities between marriage and a country dance, wherein Catherine is largely lost but she ends up giving the right response in the end. We can see both the success of Catherine and the ultimate failure of Isabella described here:

You will allow, that in both, man has the advantage of choice, woman only the power of refusal; that in both, it is an engagement between man and woman, formed for the advantage of each; and that when once entered into, they belong exclusively to each other till the moment of its dissolution; that it is their duty, each to endeavour to give the other no cause for wishing that he or she had bestowed themselves elsewhere, and their best interest to keep their own imaginations from wandering towards the perfections of their neighbours, or fancying that they should have been better off with anyone else.

James will uphold this contract, but Isabella absolutely fails. She is the one seeking but not giving advantage, she is not exclusive, she gives James the wish of bestowing himself elsewhere, she lets her imagination wander and does fancy herself better off with someone else... How very predictive! Catherine, however, only has eyes for Mr. Tilney and she gives him, "a security worth having" by artlessly saying so.

Henry gets very close to mean here: “Only go and call on Mrs. Allen!” he repeated. “What a picture of intellectual poverty!" but I love how Catherine doesn't pick up on any hints to show herself in a good light. Henry is like, "Oh you spend your time more studiously in the country?" and she's all, "No, I'm generally looking for fun, I just can't find it." Isabella would be all over proving how rational she is in the country.

So many people ask what Henry sees in Catherine (people who tend to see Catherine as an idiot), but I think we do see her good qualities in this chapter. She's honest, she's loyal, and she's happy! "Not those who bring such fresh feelings of every sort to it as you do," Catherine doesn't try to be cooler than her surroundings, she just enjoys them. And her only wish is that her family was there to enjoy it with her too. How can you not love someone like that? Someone who loves and enjoys life is a joy to be around! "her spirits danced within her, as she danced in her chair all the way home."

We end with a planned country walk and Catherine being fairly excited to learn that Henry's family is all good-looking.

Also, the term "bloom" is talked about a lot with Anne Elliot in Persuasion. I haven't seen a lot of exact explanations of what that word means, but I think we can all agree, it isn't just a term for girls: "He was a very handsome man, of a commanding aspect, past the bloom, but not past the vigour of life." It's odd that people think it's a sexist term because even in Persuasion:

Sir Walter might be excused, therefore, in forgetting her age, or, at least, be deemed only half a fool, for thinking himself and Elizabeth as blooming as ever, amidst the wreck of the good looks of everybody else

I should do a full post about that someday. Mysterious word.

Wow, that was a long chapter, but so much good stuff going on. Glad the Tilneys are back because just having the Thorpes is misery.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Threads research (chapter 13)

As I work on Threads of Fate (think historical romance novel meets Ghost fanfic, set 1312-1318), I'm publishing the research I do for each chapter here

Caveat: I am not a historian, just a nerd.

Spoilers for Chapter 13 below the cut

The like Real History bits

While Isabel, Secondo, and the whole Ministry is obviously very made up, many of the events causing them to go to Varberg were very real.

Queen Isabel was the sister of Robert the Bruce who married a king of Norway. They did have a daughter together named Ingeborg. After Queen Isabel's husband died, the throne of Norway passed to his brother. This king also had a daughter named Ingeborg (named after the former, her cousin). These two Ingeborgs married the two brothers of the Swedish king.

In December of 1317 the king of Sweden invited his brothers to a banquet where he captured and imprisoned them. Eventually they starved to death. Sweden (I've struggled a bit to figure out exactly who was involved, but think more nobles than peasants) was not a fan of this and the king was ousted later in 1318. This caused the younger Ingeborg's son, Magnus (aged ~3), to become king, though his mother and aunt remained part of his regency government.

Varberg

So, from what I can tell, we do not actually have historical evidence for the Duchesses Ingeborg gathering at Varberg in March of 1318. We have evidence for them both being in Kalmar on April 16th to sign a treaty, but I couldn't find evidence for their locations before that. Thus ~artistic license~ says that they met up at Varberg.

Varberg is located in a strategic spot between Sweden, Denmark, and Norway. Indeed, it changed hands between the 3 kingdoms several times in the early 14th century. I did see mentions of Ingeborg, Duchess of Södermanland residing there (though again, whether that was before or after (or both) the meeting at Kalmar I'm uncertain)

As the fortress was heavily modified throughout the centuries, it's hard to fully understand the medieval layout. Below is a interpretation of what it may have looked like around the time that Threads is set. It's largely what I'm basing it on as I write.

Fashion

I've been finding the early 1300s a real challenge to research in regards to fashion. Most sources seem to hold that "fashion" itself started around 1330 or more towards the middle of the century. And, of course, there were many styles that people chose to wear. So while veils and other cloth head coverings were a thing, some of the fun medieval hats were starting to emerge.

Crispinette this fantastic post, and this were my sources. Which, if they are to be believed and the fashion reached England with Queen Isabella, she married Edward in 1308. So, by 1318 we can assume that it might have reached Scotland and Mary could be wearing it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

OCTOBER 25 2023 RELEASE

All my masters can be found here, full release under the read more!I am also offering the two A Strange Loop videos as a bundle for 20 USD! If interested, please contact me at [email protected]!

The haul today is: Company (tour), A Gentleman's Guide to Love and Murder, Peter Pan Goes Wrong, A Strange Loop (London)

COMPANY October 19, 2023 | Third National Tour (Detroit, MI) | 4K MP4 (10.54GB) | bikinibottomday’s master Cast: Britney Coleman (Bobbie), Judy McLane (Joanne), Kathryn Allison (Sarah), Matthew Christian (u/s David), Ali Louis Bourzgui (Paul), Derrick Davis (Larry), Javier Ignacio (Peter), James Earl Jones II (Harry), Marina Kondo (Susan), Matt Rodin (Jamie), Emma Stratton (Jenny), Jacob Dickey (Andy), Tyler Hardwick (PJ), David Socolar (Theo) Notes: Excellent 4K capture of the new revival tour! Some wandering / readjustment and unfocusing throughout. Act Two has a visible head, but it doesn’t block off anything until the very last scene (where it is mostly worked around well). Includes curtain call, audio is fed from external source. https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjAZe9n | ASKING $20 USD NOT FOR TRADING / SHARING EXCEPT THROUGH ME UNTIL APRIL 17, 2024

A GENTLEMAN’S GUIDE TO LOVE AND MURDER October, 2022 (M) | Regional (Farmers Alley Theatre) | 4K MP4 (10.48GB) | bikinibottomday’s master Cast: Elliot Lithland (Monty Navarro), Jeremy Koch (The D'Ysquith Family), Becca Andrews (Sibella Hallward), Natalie Duncan (Phoebe D'Ysquith), Lori Moore (Miss Shingle & Others), Isabella Andrews (Miss Barley & Others), Steve Brubaker (Tom Copley & Others), Mick Jutila (Magistrate & Others), Meredith Mancuso (Lady Eugenia & Others), Michael Morrison (Inspector & Others) Notes: Nice 4K capture of this regional production! There is obstruction on the right and very left sides of the stage so some scenes are blocked, but the majority of the action is captured. There are moments of wandering and unfocusing. Due to the angle of the seat facing a thrust stage, not all actors can be seen at all times. The first six minutes of the show are a blind wideshot only, but still show the action well. Includes curtain call, audio is fed from external source. https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjAaDiq | ASKING $15 USD NOT FOR TRADING / SHARING EXCEPT THROUGH ME UNTIL APRIL 17, 2024

PETER PAN GOES WRONG May 14, 2023 (E) | Broadway | 4K MP4 (7.65GB) | bikinibottomday’s master Cast: Chris Leask (Trevor Watson), Henry Shields (Chris Bean/George Darling/Captain Hook), Stephen James Anthony (s/b Robert Grove/Nana the Dog/Starkey), Matthew Cavendish (Max Bennett/Michael Darling/the Crocodile), Harry Kershaw (Francis Beaumont/Cecco), Charlie Russell (Sandra Wilkinson/Wendy Darling), Jonathan Sayer (Dennis Tyde/John Darling/Mr Smee), Bianca Horn (u/s Annie Twilloil/Mary Darling/Lisa/Tinker Bell/Curly), Brennan Stacker (s/w Gill), Greg Tannahill (Jonathan Harris/Peter Pan), Ellie Morris (Lucy Grove/Tootles) Notes: Excellent 4K capture of a neat set of understudies! Minor head obstruction on the left and bottom in the first act only. Second act is unobstructed. Increased wandering and unfocusing throughout. Includes curtain call, audio is fed from external source. https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjADKks | ASKING $20 USD NOT FOR TRADING / SHARING EXCEPT THROUGH ME UNTIL APRIL 17, 2024

A STRANGE LOOP August 4, 2023 | Off West End | 4K MP4 (7.9GB) | bikinibottomday’s master Cast: Kyle Ramar Freeman (Usher), Sharlene Hector (Thought 1), Nathan Armarkwei-Laryea (Thought 2), Yeykayi Ushe (Thought 3), Tendai Humphrey Sitima (Thought 4), Danny Bailey (Thought 5), Jean-Luke Worrell (u/s Thought 6) Notes: Great 4K capture of Jean-Luke’s debut as Thought 6! There is about two minutes of blackout in total, mostly in the first 30 minutes in between scenes, which causes some missed action. Some wandering / readjustment and unfocusing throughout. A bar obstruction is visible but is mostly unobtrusive. Includes curtain call, audio fed from external source. https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjAPVyo | ASKING $15 USD NOT FOR TRADING / SHARING EXCEPT THROUGH ME UNTIL APRIL 17, 2024

A STRANGE LOOP August 10, 2023 (M) | Off West End | 4K MP4 (7.84GB) | bikinibottomday’s master Cast: Kyle Birch (alt Usher), Sharlene Hector (Thought 1), Nathan Armarkwei-Laryea (Thought 2), Yeukayi Ushe (Thought 3), Tendai Humphrey Sitima (Thought 4), Danny Bailey (Thought 5), Eddie Elliott (Thought 6) Notes: Excellent 4K capture of Kyle Birch as Usher! There is a railing obstruction at the bottom which doesn’t block off much, though it varies throughout the show. A few brief blackouts throughout. Inwood Daddy was blindshot and therefore not very easy to see action. Increased wandering / readjustment and unfocusing throughout. Includes curtain call, audio is fed from external source. https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjAQAws | ASKING $15 USD NOT FOR TRADING / SHARING EXCEPT THROUGH ME UNTIL APRIL 17, 2024

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram story: Aug 11, 2023

#cats korea tour 2022#cats taiwan extension 2023#source: katie hutton#katie hutton#rumpelteazer#isabella roberts#victoria (cats)#victoria the white cat#lucy rice#bombalurina#meghan peploe williams#cassandra (cats)#saverio pescucci#alonzo (cats)#johnny randall#mr mistoffelees#mistoffelees#jack danson#chorus tugger#backstage cats#closing cats countdowns skip the queue because i'm sad#please stop counting down shows you make me sad

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Virtual Sketchbook #3

The Triumph of Divine Love by Peter Paul Rubens, 1625. Accessed 03/26/2024 https://ringlingdocents.org/divine.htm.

Describe Visual Qualities:

The Triumph of Divine Love by Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens is a oil on canvas painting. The massive size is very eye-catching with a height of 17ft (518.2cm) and width of 12.6ft (386.1 cm). At first glance the painting consists of cheery and bright colors that create a joyful feeling. The main subject is Charity at the center, holding one of her children, highlighted with the lightest part of the painting. Two more of her children stand next to her as they ride a chariot pulled by two lions, which show contrasting shadows at the bottom of the piece. The borders also show contrasting shadows that work to pull viewers’ attention towards the center. The artwork possesses a variety of subjects such as Charity (who resembles Mother Mary), twelve putti flying in the air (winged children, Cupids), three more grounded putti one of whom is riding a lion holding an arrow, two lions, a pelican piercing its own breast to feed its young, and two intertwined snakes. The varying subjects do not create a chaotic effect, instead a sense of unity is felt through the placement of light and dark areas as well as the central focal point.

How does work make you feel:

During my visit to the Ringling Museum of Art, The Triumph of Divine Love piqued my interest the most. Its size and complexity first caught my attention. I’ll admit I am not the biggest fan of old religious art pieces, but the beauty of this painting cannot be denied. The central focal point of the female figure cradling her baby with a look of fondness and joy reminded of my maternal feelings of love for my own baby. Viewing the piece inspires feelings of happiness and contentment. I also felt a sense of happiness while viewing the work.

The upbeat tone versus other more graphic sad scene of most paintings of this era is what made me admire it.

Research:

Peter Paul Rubens created The Triumph of Divine Love in the 17th century. Rubens was one of the most well-known Baroque artists of that time. Rubens was commissioned by Archduchess Isabella, “to design the 20 cartoons for the tapestry series of the Triumph of the Eucharist for the convent of the Descalzas Reales in Madrid” (Vlieghe).

The Triumph of Divine Love was one of this series. As a devote Catholic, Ruben incorporated allegory of religious event into many of his works. “Europeans had so linked the body of Christ with the body social and political that the Eucharist became "the emblematic focus of the struggle" between Catholics and Protestants…” (Harrie). In the Eucharist cycle, the artist focused on portraying victory of good over evil. Specifically in The Triumph of Divine Love, Rubenscreates a scene of celebration after, “the defeat of evil in the world by religious or divine love” (Anderson).

Personal Critique:

After my research I view Ruben The Triumph of Divine Love in a much different way. The symbolism shown throughout tells a story of, as the title refers, triumph. The putti are a way to show profane love. The snakes intertwined at the bottom represent evil with the flaming heart above as the “Sacred Heart” referring to Jesus’s love for humanity. The positioning of these symbols infers the defeat of evil with faith. Prior to this project, I lacked knowledge to identify the meaning behind the subjects. The painting is a clear representation of the cultural ideals of that time, and I have learned a great deal from looking into the purpose of its creation. The skill needed to execute this timeless piece of art shows the mastery Rubens possessed and why he was one of the best artists of the 17th century. I can only imagine the effect of seeing all of Rubens’ Eucharist series together.

Selfie of my in the beautiful Ringling Courtyard.

Cites Sources:

Anderson, Robert. The Triumph of Divine Love, 2000, accessed 29 March 2024, https://ringlingdocents.org/divine.htm.

Harris Jeanne. Discussion of Léonard Limosin's enamel Triumph of the Eucharist and of the Catholic Faith, Sixteenth Century Journal; Spring2006, Vol. 37 Issue 1, p43-57, 15p, accessed 29 March 2024, https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=5&sid=657838c2-4aef-4ee5-9605-b9bffb78a770%40redis&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPXNoaWImc2l0ZT1laG9zdC1saXZl#AN=509859203&db=hus.

Vlieghe, Hans. "Rubens, Peter Paul." Grove Art Online. 2003. Oxford University Press. Date of access 29 Mar. 2024, https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/display/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000074324?rskey=4WqXlf&result=1.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toonami Weekly Recap 06/07/2025

Bleach: Thousand-Year Blood War Part 1: The Blood Warfare EP#04 (370) - Kill the Shadow: Over 1,000 Soul Reapers die within seven minutes of the Quincy's invasion. 3rd Division captain R?j?r? "Rose" ?toribashi meets Stern Ritter "U" NaNaNa Najahkoop, 6th Division captain Byakuya Kuchiki and lieutenant Renji Abarai face off against Stern Ritter "F" Äs Nödt and Stern Ritter "S" Mask De Masculine, and 7th Division captain Sajin Komamura on Stern Ritter "E" Bambietta Basterbine. The other Soul Society captains confront unnamed Stern Ritters. As the fighting reaches a stalemate, the 2nd Division captain Soi-Fon, Byakuya, Komamura, and 10th Division captain Toshiro Hitsugaya release their Bankais, but they are stolen by their opponent Stern Ritters using absorbing medallions. The captains are shocked by the news that the Stern Ritters' trump card is to steal Bankais, as it is communicated to the rest of the Soul Society. 8th Division captain, Shunsui Kyoraku is blinded in his right eye by Stern Ritter "N" Robert Accutrone. While Quilge fights against Ichigo, Urahara observes that the Stern Ritters failed to steal Ichigo's Bankai. Urahara opens the portal for Ichigo to enter there and join the fight. However, Quilge attacks Urahara, Orihime, and Chad, and uses his Stern Ritter ability, "The Jail", to trap Ichigo in the Garganta, preventing him from reaching the Soul Society.

Blue Exorcist: Kyoto Saga EP#29 (04) - Act of Treachery: Ryuji secretly tails Juzo to the Deep Keep, discovering incapacitated Exorcists along the way. Meanwhile, Rin finally manages to intentionally light two candles with his flames. Shura reminds him that this is only the beginning of his training and Rin reflects on Mephisto's wager with the Vatican. Back in the Keep, Juzo confronts Mamushi. She explains her betrayal was meant to expose the corruption within Myoda, based on claims from Todo that the Left Eye was being kept in secret by Mephisto. Citing the Vatican's hearing from the previous week where Mephisto was revealed to be protecting Satan's spawn, she believes aligning with Todo is for the greater good. Unbeknownst to them, Tatsuma, Yaozo, and Uwabami are observing through hidden security cameras. When Juzo and Mamushi clash, Ryuji intervenes. Suddenly, tremors shake the Keep, while Shura and Rin run towards the source of the disturbance. The ceiling over the Keep rots away as Todo appears. Despite warnings from Juzo, Mamushi removes the Left Eye and vanishes with Todo. Ryuji then confronts his father over the accusations that Mamushi made. Tatsuma refuses to explain, claiming the matter is top secret. Ryuji angrily disowns him in front of everyone in response. Rin recalls his final words with his own father and, overcome with emotion, begs Ryuji to apologize to his father. His blue flames suddenly burst out, alarming the Myoda followers that are present. Juzo strikes Rin, and Shura subdues him to prevent further escalation. Yaozo demands an explanation from Shura later.

Lazarus EP#10 - I Can't Tell You Why: Hospitals begin reporting surges in patients suffering from high fevers, prompting government warnings to stay indoors. At Lazarus headquarters, Chris' earlier discovery, a pill found at Skinner's residence, is identified as medication for artificial heart recipients. The team suspects Skinner may have had such a transplant. However, Eleina finds no medical record on it. Hersch recalls rumors of a private clinic conducting confidential surgeries. Leland offers his assistance and takes Axel and Doug to his estranged family's mansion. There, his sister Isabella agrees to grant clinic access if Leland spends the weekend with her. The trio later arrive at the clinic where Millie, Leland's late father's physician, confirms Skinner received an artificial heart, though its telemetry was immediately encrypted post-operation. She provides them with a flash drive containing the device's firmware. Meanwhile, Abel shows Hersch leaked footage of the Schiphol Airport incident, where Skinner accidentally released a gaseous Hapna prototype after Delta Force and airport police shot through his briefcase during a standoff. Abel links the same prototype to an Arizona prison where it was being trialed on inmates. Axel, having been there during the trials and being the apparent sole survivor, is sent to find the prison's doctor. Eleina discovers the artificial heart is being monitored from Pakistan where Popcown Wizard is located, and Doug agrees to travel with her there. Meanwhile, Axel's search for the prison doctor is interrupted by a grenade explosion and a traffic jam. As he brakes, Soryu ominously approaches.

6 Days Left...

Naruto (Chunin Exams Arc) EP#21 - Identify Yourself: Powerful New Rivals: Encountering the Sand Siblings, Team 7 learns that the three are ninja who have come from the Hidden Sand Village to participate in the Chunin Exams to be promoted to Chunin-level ninja. Elsewhere, meeting with Hiruzen on the matter, Kakashi, the Third Hokage's son Asuma, and Kurenai Yuhi all nominate their students for the Chunin Exams to Iruka's disbelief. Iruka challenges their decision as he believes Naruto and the others are not ready for the exam, but Kakashi explains to Iruka that they are no longer his students. The next day, Kakashi gives Team 7 the application forms for the Chunin Exams with Sasuke and Naruto more than willing, while Sakura is uncertain. Later, each member of Team 7 is attacked by a mysterious ninja that they defeated in a one-on-one fight. The figure is revealed to be Iruka, who reports to Kakashi of approving his choice. Later, while making their way to site of the Chunin Exam, Team 7 meets Rock Lee, Neji Hyuga, and Tenten. Though they leave to make their way to where the exams are, Team 7 discovers Lee challenging Sasuke.

Slightly Damned Page 1157: https://www.sdamned.com/comic/1157

youtube

#Toonami#Toonami Weekly Recap#New Toonami Show Promo#Bleach#Bleach: Thousand Year Blood War#The Blood Warfare Arc#Blue Exorcist#Blue Exorcist: Kyoto Saga#Lazarus#Naruto#Chunin Exams Arc#slightly damned#Dragon Ball#Dragon Ball Daima#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

China: Where the Extremes Meet by André Barbieri provides key elements for the discussion about what China is today and the revolutionary potential of the Chinese working class. The publication of a serious and in-depth study of contemporary China is always a welcome event. Understanding the transformations of the Asian giant over the past few decades, and their impact on international relations as a whole is essential for questioning where the global system is headed. This year, Iskra Books published André Barbieri’s China: Where Extremes Meet. Trotsky, Permanent Revolution and a Critique of Capital’s Multilateralism in the Xi Jinping Era, which fully meets these requirements of seriousness and depth. The book is organized into three parts. The first discusses the role China can play in an increasingly disordered world order. To do so, it investigates the profound transformations that Chinese society has undergone in recent decades. The second part reviews the strategies implemented in China since the first revolutionary uprisings of the 20th century, highlighting the consequences of the Maoist leadership’s seizure of power, which, from the formation of the People’s Republic, blocked any socialist transition. Finally, the third part describes the processes of struggle that have been developing throughout China, the regime’s responses to them, and the enormous revolutionary possibilities that could arise if revolutionary parties capable of harnessing those phenomena were to develop. The Development of Capitalism in China Barbieri has drawn upon a comprehensive study of sources that have allowed him, and also allows those of us who read his book, to gain insight into the complexity of China’s socio-economic configuration. He offers good grounds for why we should understand China as a capitalist social formation, despite all the hybrid aspects — the “characteristics” of so-called “Chinese socialism,” as it were — that mark its socio-economic system. A very valuable aspect of this study is the broad range of authors with whom Barbieri polemicizes with. We find some classic discussions, in the field of the Marxist Left and related fields, such as Perry Anderson’s article “Two Revolutions” and Giovanni Arrighi’s Adam Smith in Beijing. But he also engages with some of the most recent discussions of China, such as Isabella Weber’s study on how China escaped the shock therapy applied in Russia and Eastern Europe. Domenico Losurdo, Michael Roberts, and Elias Jabour are some of the other authors with whom Barbieri also develops counterpoints. The critique that Barbieri offers of these thinkers is very productive, as it reveals the weaknesses of perspectives that seek to question or relativize China’s capitalist transformation.

continue reading

0 notes

Text

On August 25th in the year 1330 Scotland lost one of it’s greatest warriors when The Good Sir James Douglas fell at Teba in what is modern day Spain.

James was called “The Black Douglas” by the English for his dark deeds in their eyes, becoming the Bogeyman of a Northern English lullaby “Hush ye, hush ye, little pet ye. Hush ye, hush ye, do not fret ye. The Black Douglas shall not get ye.”

There are also unsubstantiated theories that this was because of his colouring and complexion, this is tenuous, Douglas only appears in English record as “The Black”, in Scots’ chronicles he is almost always referred to as “The Guid” or “The Good”. Later Douglas Lords took the moniker of their revered forebear in the same way that they attached Bruce’s Heart to their Coat of Arms, to strike fear into the hearts of their enemies and exhibit the prowess of their race.

Robert the Bruce had requested that Douglas, latterly his most esteemed companion in arms, should carry his heart to the Holy Land, as atonement for the murder of John Comyn, and the fact that his excommunication meant he was unable to go on a Crusade himself.

Douglas and his knights had been invited to join the forces of Alfonso XI of Castile, Edward of England’s cousin by Queen Isabella, mother of King Edward III of England to fight a Crusade against the Moors in 1330 at the Castle of the Stars at Teba, he was killed as he led a cavalry charge against the enemy while outnumbered and cut off from the main Christian force. He is said to have through Bruce’s heart forward as he was about to be slain, although another source states it was still tied around his neck,

Remarkably the casket survived to this day and was returned to Scotland, to be interred at Melrose Abbey. Douglas’ bones were boiled and returned to Scotland. His remains were laid to rest at St Bride’s Church, Douglas, which houses the monumental tombs of Black Douglas earls.

You may see artist impressions of the Guid Sir James with the Douglas Shield and it’s red heart, this is an inaccurate depiction it wasn’t until 1333 the ‘bloody heart’ was incorporated in the arms of Sir James’ son, William, Lord of Douglas. It subsequently appeared, sometimes with a royal crown, in every branch of the Douglas family.

The village of Teba, in the Guadalhorce-Guadalteba region, still remembers The Good Sir James by holding the two day Jornadas Escocesas (Scottish Festival) every year, also called Scottish Days or Douglas Days Teba. There are numerous people and associations that collaborate in the organization of these days. Some of them, such as the Saint Andrew's Society of Gibraltar, the Order of Knights Templar of Saint Michael or The Strathleven Artizans, expressly travel from Scotland to participate in the event.

The Village of Teba, is twinned with Melrose in the Scottish Borders.

More on all this on their web page here https://www.douglasdaysteba.com/

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

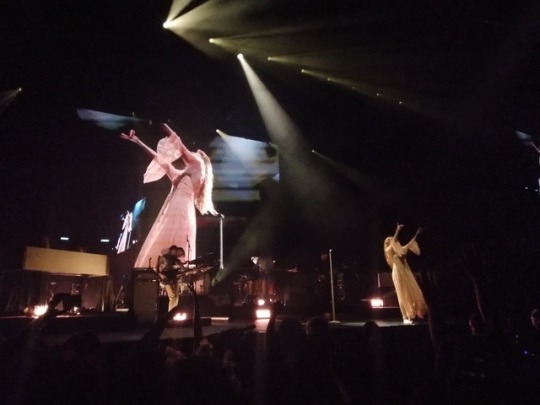

Some photos I took last night from their concert in Mexico City ✨

#florence and the machine#florence + the machine#florence welch#florence & the machine#f+tm source#florence#how big how blue how beautiful#isa machine#isabella summers#fatm#rob ackroyd#ceremonials#lungs#isamachine#f+tm#tom moth#between two lungs#hbhbhb#robert ackroyd#delilah#ship to wreck#fatm source#isabella machine#queen of peace#what kind of man#live#mexico#mexico city#palacio de los deportes#sport palace

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

FEBRUARY 10 2023 RELEASE

All my masters can be found here, full release under the read more!

BEETLEJUICE February 5, 2023 (M) | First US Tour (Detroit, MI) | 4K MP4 (10.07GB) | bikinibottomday’s master Cast: Justin Collette (Beetlejuice), Isabella Esler (Lydia Deetz), Britney Coleman (Barbara Maitland), Will Burton (Adam Maitland), Jesse Sharp (Charles Deetz), Kate Marilley (Delia Deetz), Danielle Marie Gonzalez (Miss Argentina), Graham Stevens (e/c Otho), Brian Vaughn (Maxie Dean), Karmine Alers (Maxine Dean/Juno), Jackera Davis (Girl Scout) Notes: Excellent 4K capture of Graham Stevens’ final performance! Some wandering and unfocusing throughout. Audio in the second act is a bit muffled but still very audible. Includes curtain call, audio is fed from external source. https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjAr4YS | ASKING $20 USD NOT FOR TRADING / SHARING UNTIL JUNE 17, 2023

BEETLEJUICE February 7, 2023 (M) | First US Tour (Detroit, MI) | 4K MP4 (10.12GB) | bikinibottomday’s master Cast: Justin Collette (Beetlejuice), Isabella Esler (Lydia Deetz), Britney Coleman (Barbara Maitland), Will Burton (Adam Maitland), Jesse Sharp (Charles Deetz), Kate Marilley (Delia Deetz), Danielle Marie Gonzalez (Miss Argentina), Matthew Michael Janisse (u/s Otho), Brian Vaughn (Maxie Dean), Karmine Alers (Maxine Dean/Juno), Jackera Davis (Girl Scout) Notes: Great 4K fancam of the Maitlands! This video follows Britney and Will and focuses on them in scenes where they are the background. When they aren’t on stage, it’s a normal video. Not recommended for first time viewers. Mild obstruction on the left side of the stage that doesn’t really block anything. Some wandering and unfocusing throughout. Includes curtain call, audio is fed from external source. https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjArpNX | ASKING $16 USD NOT FOR TRADING / SHARING UNTIL JUNE 17, 2023

NOTRE DAME DE PARIS July 23, 2022 (M) | Lincoln Center | 4K MP4 (19.36GB) | bikinibottomday’s master Cast: Angelo Del Vecchio (Quasimodo), Hiba Tawaji (Esmeralda), Robert Marien (alt Frollo), John Eyzen (alt Gringoire), Emma Lepine (Fleur-De-Lys), Yvan Pedneault (Phoebus), Jay (Clopin) Acrobats: Morgan Fasulo, Jonathan Gajdane, Nathan Jones, Matthieu Jordan, Andrea Neyroz Breakers: Alex Besnier, Jaeburn Lee Dancers: Lorenzo Arnouts, Domenico Ausilio, Antonio Belsamo, Giulia Barbone, Maria Barbone, Alessandra Berti, Rodolphe Duquesne, Giuseppe Marino, Gabriel Nabo, Serena Origgi, Alessia Papale, Valentin Piers, Laurisse Sulty, Ivan Trimarchi, Vaia Veneti, Roberta Zegretti Notes: Excellent 4K capture of this world-renowned musical’s New York premiere. The captions screens at this performance weren’t working, but English subtitles are included in the folder. One small obstruction is visible on the bottom of the frame in Act One, but doesn’t block any action. Spotlight washout is visible on some wideshots, and there are moments of wandering and unfocusing. https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjA1cg8 | ASKING $20 USD NOT FOR TRADING / SHARING UNTIL JUNE 17, 2023

TOPDOG / UNDERDOG December 17, 2022 (M) | Broadway | 4K MP4 (9.53GB) | bikinibottomday’s master Cast: Corey Hawkins (Lincoln), Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Booth) Notes: Excellent 4K capture of this hilariously dark revival. Some minor wandering and unfocusing throughout. Includes curtain call, audio is fed from external source. https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjAjFNo | ASKING $20 USD NOT FOR TRADING / SHARING UNTIL JUNE 17, 2023

I am also offering the two Beetlejuice tour videos as a bundle for 30 USD total! If interested, please contact me at [email protected]!

#beetlejuice the musical#isabella esler#justin collette#notre dame de paris#topdog underdog#britney coleman#will burton#bikinibottomday releases

57 notes

·

View notes