#text: moll flanders

Text

I finished Moll Flanders and I think I can make it relevant to my dissertation, but my favorite part isn't, really. It's this:

In short, I began to think, and to think is one real advance from hell to heaven. All that hellish, hardened state and temper of soul, which I have said so much of before, is but a deprivation of thought; he that is restored to his power of thinking, is restored to himself.

#isabel talks#text: moll flanders#artist: daniel defoe#eighteenth century chatter#academic chatter#british lit chatter: long eighteenth century#dissertation hell

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

F&B A Surfeit of Rulers

GRRM is playing loose with his inspirations here – this is very much 18th century, post-print revolution, not Medieval or even Renaissance. On the one hand, the history nerd in me is objecting that it doesn't make sense outside of the social and technological developments of that era (growth in the circulablity of texts, the increase of literacy, and the change in sexual mores and moral instruction). On the other hand, it's just too delicious not to include in your fantasy story. I mean, if real history is the raw material you're building your imaginary world from, not using things like Fanny Hill and Moll Flanders is inexcusably leaving the best ingredients on the table.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Defining the picaresque

[by J. Ardila, abridged]

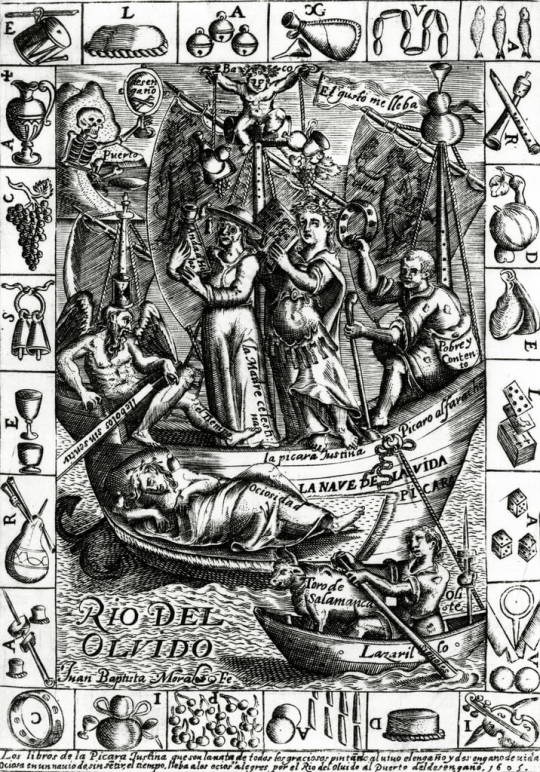

Cover of La pícara Justina (1605), featuring “The ship of picaresque life” sailing on the River of Oblivion. Aboard the vessels are the eponymous Justina, and three protagonists of earlier picaresque (or adjacent) novels (Celestina, Guzmán de Alfarache “poor and content”, and Lazarillo de Tormes), on the helm is Time, Idleness is sleeping below, and Death is waiting above.

Most critics within Spanish literary studies agree that a picaresque genre did indeed exist, that [it began with Lazarillo de Tormes in 1554 and was consolidated with Guzmán de Alfarache in 1599], and that it thrived in the first half of the seventeenth century. The vast majority of critics concur that the main features of the picaresque genre are:

its formal realism and hence structure [when each development in the plot is the logical corollary of events that precede it, as opposed to the and-then structure where episodes are in random order and interchangeable];

it is the fictitious autobiography of the main character, commonly narrated in the first person;

the text is addressed to either a narratee or an implicit reader;

the protagonist tells his or her life in order to explain how they came to find themselves in a particular situation;

it is highly satirical and often comical, and serves the author to express his own political views;

the narrator’s discourse is often ironic and so is the general message of the text;

its protagonist is a picaro,

a picaro being a literary type who

is born to a family of the underclass, normally new Christians [i.e. of Jewish or Moorish descent; when the genre appears, Spain has already expelled or forcibly converted all Jews and Muslims, and treats those who converted and stayed as second class citizens; many protagonists AND authors of the Spanish picaresque belonged in this minority], a condition that determines his future,

undergoes a progressive psychological change,

is a social outsider who tries his hand at several professions living by his or her wits,

normally engages in unlawful activities, and

is a cunning trickster who deceives others.

This set of characteristics is seldom found in picaresque narratives published in Spain after Guzmán. For instance, many picaresque novels were written in the form of second- and third-person narratives, and even as dialogues. Taking the study of the picaresque beyond Spain will also show that the life of some picaros is not conditioned by their parentage and, contrary to Spanish picaros, they climb the social ladder until they achieve a comfortable position, e.g. Moll Flanders, Colonel Jack and Ferdinand Count Fathom. The picaresque elements of any post-Guzmán picaresque fiction will inevitably adapt to the personal circumstances and the cultural context of its author, and it is imperative to account for these when assessing its relation to the picaresque genre.

These and other facts considered, the essential characteristics of the picaresque genre are three –

the narration of a life expounding the circumstances leading to a final situation;

the implicit satire of the novel that reflects the social bias of the author;

the picaro as protagonist.

Readers in Spain and abroad always appreciated the social realism of the picaresque novels. Yet although social criticism was overt in the picaresque, it took some time for critics to understand the genre’s social bias. Social bias was a common denominator in the first picaresque novels – most of the authors in the genre were amateur writers who belonged to a social minority and chose to write a picaresque tale because of the genre’s adaptability to social satire. The picaresque is hardly without a political message. It is a form of Bildungsroman that reflects on men’s place in society and how they came to understand and accept their status. This aim addresses issues of philosophical concern; the picaresque urge to understand the social meaning of life elaborated a complex existential philosophy.

Finally, the main character of a picaresque novel is a picaro, a literary type who encompasses all the characteristics explained above. The picaro was conceived as a parody of the heroes in the romances and also as a social outsider who rebels against the establishment. Not all antiheroic delinquents are picaros, however. According to Baudelaire, the delinquent is – alongside the artist and the prostitute – one of the three most frequently encountered characters in modern literature. Taking the delinquent as the main or sole element of the picaresque would inevitably and spuriously turn the genre into a catch-all category comprising texts some of which have little or nothing in common with it.

An excellent example of the confusion that pseudo-picaros may cause is to be found in Cervantes’s La ilustre fregona (The Illustrious Scullery Maid, 1613), which has often been classed as picaresque because of its two pseudo-picaro protagonists. However, don Diego and don Juan are not picaros. The narrator begins this novella declaring that they were ‘dos caballeros principales y ricos’ (two famous and rich gentlemen), that don Juan had an ‘inclinación picaresca’ (picaresque inclination) and succeeded in becoming a picaro to the extent ‘that he could give a lecture at the university to the famous picaro from Alfarache’. Cervantes, of course, is parodying the picaresque. A picarowas an outsider, born into the underclass, who endures poverty andbecomes a picaro because he has no choice, despite his determination to rise socially. Don Diego and don Juan are noblemen who decide to become picaros to enjoy the freedom of picaresque life. But picaros were far from considering themselves the beneficiaries of freedom – it was never their choice to become picaros; conversely, they always express very explicitly their strong desire for a respectable life.

The picaro type results from the new conditions of modern society. This new literary type features in the Spanish picaresque novels of the seventeenth century and in those published subsequently in other countries, especially in eighteenth-century England. Small differences and variations are the inevitable corollary of the usage of the picaresque mould in different cultural contexts.

— J. Ardila (2015). "Origins and definition of the picaresque genre." The Picaresque Novel in Western Literature, 1–23.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

How The Black Death Shaped Humanity

I have been reading some interesting stuff about how the Black Death shaped humanity. Plague has been with humankind at least 5, 000 years and has been one of our most efficient killers.

“Plague is an infectious disease caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, a zoonotic bacteria, usually found in small mammals and their fleas. It is transmitted between animals through fleas.”

- (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/plague#:~:text=Plagueisaninfectiousdisease,transmittedbetweenanimalsthroughfleas.)

Yersinia pestis is the official name of this malevolent bacteria, which has a predilection for human victims. It manifests in bubonic and pneumonic ways to spread death and disease. It has been found in ancient DNA by scientists and looks to have originated on the steppes of Eurasia.

The Plague Effect On Human History

Plague spreads via human to human contact, once it has crossed over from its original animal/insect source. Our taste for travel and trade is what makes the devastation possible, as plague wreaks havoc through populations of people. Reading a first hand account of the Great Plague in Britain in the 17C by renowned author Daniel Defoe was eye opening. The similarities in public health policies with our own recent Coronavirus pandemic are startling. It is well worth a read.

“Defoe, Daniel. Journal of the Plague Year, Being Observations or Memorials, of the Most Remarkable occurrences, as Well Publick as Private, which Happened in London during the Last Great Visitation in 1665, Written by a Citizen who Continued All the While in London. Never Made Public Before. London, Printed for E. Nutt, J. Roberts, A. Dodd, and J. Graves, 1722.

SPC Rare xx PR 3404 .J4 1722

Daniel Defoe, 1660?–1731 was a London area based businessman, journalist, political pamphleteer, spy, and one of the early proponents of the novel as a genre of literature. Students still read his novels Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders. His Review was one of the earliest periodicals.”

- (https://lib.msu.edu/exhibits/defoe)

Religion, Black Death & Misunderstanding

Plague came around and impacted populations in cities and towns seemingly cyclically. Reading Defoe’s account one sensed the frustrating and fatalistic reactions within societies faced with a black hole of scientific ignorance at what caused this horrendous killer of human beings. Religion made everything worse on this score, as the superstitious and ungrounded beliefs of the age distracted minds away from the evidence before them. Christianity, like most Bronze Age religions, diminished the material/body and gave far more intellectual weight to the intangible concept of the soul. This hocus pocus hodge podge had prayers for divine intervention high up on the menu, which sadly rarely eventuated. Legions of priests and clergy were claimed by the plague, as they went about their duties during the worst of each outbreak. However, in London they did have all the cats and dogs put to death, as a preventative measure in the cities fight against the scourge of this infectious disease. This shows that there were some right thinking officials involved in public health policy initiatives even back then. Today, with our own scientific knowledge, it is hard to comprehend that so many did not understand the role of blood borne infectious agents in plague. I mean human beings must have been very aware of blood from time immemorial. Every time someone plunged a knife or sword into another there it was. Similarly, bed bugs and mosquitos have been biting us for countless millennia. The absence of an understanding of the microbial world is glaringly obvious with hindsight. Sadly, man’s invented God offered no insight in this key regard.

Plague’s Butcher’s Bill

The enormous mortality rate of plague everywhere it flourished, especially in large cities like London, was astounding. Defoe made lists of the weekly death rate from plague in various parts of London.

“The next week And to the 1st

- was thus: of Aug. thus:

Aldgate 14 34 65

Stepney 33 58 76

Whitechappel 21 48 79

St Katherine, Tower 2 4 4

Trinity, Minories 1 1 4

- —- —- —-

- 71 145 228

It was indeed coming on again, for the burials that same week were in the next adjoining parishes thus:—

- The next week

- prodigiously To the 1st of

- increased, as: Aug. thus:

St Leonard’s, Shoreditch 64 84 110

St Botolph’s, Bishopsgate 65 105 116

St Giles’s, Cripplegate 213 421 554

- —- —- —-

- 342 610 780”

- (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/376/376-h/376-h.htm)

The above excerpted figures were in the early phase of the outbreak of plague in London in the 17C. These numbers would rise exponentially, as the death carts and pits would take ever greater volumes of those carried off by the disease. Dealing with the dead was always done under the cover of darkness, so as not to alarm the citizenry.

- Of all of the

- Diseases. Plague

From August 8 to August 15 5319 3880

” ” 15 ” 22 5568 4237

” ” 22 ” 29 7496 6102

” ” 29 to September 5 8252 6988

” September 5 ” 12 7690 6544

” ” 12 ” 19 8297 7165

” ” 19 ” 26 6460 5533

” ” 26 to October 3 5720 4979

” October 3 ” 10 5068 4327

- ——- ——-

- 59,870 49,705

Tens of thousands of human beings dying in a matter of weeks would overwhelm many of us today, I would contend. Imagine being no wiser as to why this was occurring! Of course, we would invent some reason so as to put our distressed minds at some sort of, if not rest, temporary way station on the journey to resignation. Putting stuff down to the divine intervention of a cruel god or demon still appeals to some of us today.

“If I may be allowed to give my opinion, by what I saw with my eyes and heard from other people that were eye-witnesses, I do verily believe the same, viz., that there died at least 100,000 of the plague only, besides other distempers and besides those which died in the fields and highways and secret Places out of the compass of the communication, as it was called, and who were not put down in the bills though they really belonged to the body of the inhabitants. It was known to us all that abundance of poor despairing creatures who had the distemper upon them, and were grown stupid or melancholy by their misery, as many were, wandered away into the fields and Woods, and into secret uncouth places almost anywhere, to creep into a bush or hedge and die.”

- (Defoe, Daniel. Journal of the Plague Year)

The Economic Effects Of The Plague

In the current era, for most of us our gods are now economic in nature. Therefore, it is behoven upon me to focus on how the Black Death impacted upon communities in this manner. To consider how the economics stacked up when cities lost half or more of their entire populations. Well, topically in today’s zeitgeist it created inflation, as it drove up wages due to the scarcity of available labour. With all those folk dead employers had to pay more to get individuals to do the required jobs.

“The economy underwent abrupt and extreme inflation. Since it was so difficult (and dangerous) to procure goods through trade and to produce them, the prices of both goods produced locally and those imported from afar skyrocketed. Because of illness and death workers became exceedingly scarce, so even peasants felt the effects of the new rise in wages. The demand for people to work the land was so high that it threatened the manorial holdings. Serfs were no longer tied to one master; if one left the land, another lord would instantly hire them. The lords had to make changes in order to make the situation more profitable for the peasants and so keep them on their land. In general, wages outpaced prices and the standard of living was subsequently raised.”

(Ed: D.S.) Courie, Leonard W. The Black Death and Peasant's Revolt. New York: Wayland Publishers, 1972; Strayer, Joseph R., ed. Dictionary of the Middle Ages. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Vol. 2. pp. 257-267.

- (https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Italian_Studies/dweb/plague/effects/social.php)

The workers found a friend in the economic impact of plague upon their lives if they were fortunate enough to survive. They may have lost loved ones and family but their meagre pay packets benefitted somewhat from the shortage of human labour more generally. Inflation in the current clime is seen as a very bad thing, with our central banks putting economies into virtual recessions to get on top of rising inflation. However, not all economists are in agreement about all inflation being a bad thing. In this instance, it positively contributed to peasants getting a raise and breaking free of crippling serfdom arrangements which bound them to the land and their lords.

Black Death Plague’s Roll Call Through History

Plagues have been plaguing humanity for more than 5, 000 years and their death tolls have shaped our civilisation in many ways.

“During the fourteenth century, the bubonic plague or Black Death killed more than one third of Europe or 25 million people. Those afflicted died quickly and horribly from an unseen menace, spiking high fevers with suppurative buboes (swellings). Its causative agent is Yersinia pestis, creating recurrent plague cycles from the Bronze Age into modern-day California and Mongolia. Plague remains endemic in Madagascar, Congo, and Peru.”

- (Glatter KA, Finkelman P. History of the Plague: An Ancient Pandemic for the Age of COVID-19. Am J Med. 2021 Feb;134(2):176-181. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.08.019. Epub 2020 Sep 24. PMID: 32979306; PMCID: PMC7513766.)

Pestilence makes itself known within the pages of the Bible, that best selling fictional account of the roots of Christianity and Judaism purporting to be the history of the world. Even in Sunday school, I remember the colourful boasts made about a God smiting his more powerful enemies with 7 years of pestilence in Egypt and other places. The inflated claims from a paranoid exiled group of Judeans and Israelites reads like a mad manifesto that barely touches the ground of any factual reality. That this Old Testament thinking has infected the minds of Christian Nationalists in the US today is probably no surprise when you think about the fate of the South in the Civil War. Birds of a feather and all that.

Blaming The Black Death On The Jews

Unfortunately, for minorities in the Dark Ages, often the Jewish ghetto within Christian populations, they would cop it from those wishing to blame it on them during plague times. Their homes would be destroyed, places of worship desecrated, and their lives slaughtered and burnt alive. Blame it on the immigrant, those that were considered ‘other’ and outside of the accepted members of the community or township was a popular means of venting. This occurred with sickening regularity in places all over Europe. The Jews were historically blamed for killing Christ, despite the fact that it was the Romans who did the actual crucifying. Pogroms against the Jews and other minorities accompanied most periods of plague down through the ages.

Culling Creatures & Plague

The main thrust of this is that plagues have been culling humanity with regularity for 5 millennia. This means that Yersinia pestis has been our hand maiden of death for a very long time. We, as human beings, like to think of ourselves as above all other creatures on earth. In actual fact, we are just another species of animal making our way with all the attendant connections to everything else. We do not stand outside of the holistic totality of mother earth. We Homo sapiens cull other creatures within our environments when we consider there to be too many of them. In Australia, we regularly cull kangaroos in various locations in response to calls for their management. Livestock is culled for breeding purposes and stock management levels. Wild animals are culled when their numbers are considered to be excessive to their environment and habitats. Yersinia pestis has been our culling agent over the last 5 thousand years. Theists may see it as God deeming there to be too many of us running about the place, thinking and doing sinful things and causing havoc. Those of us with a bit of a green thumb know that pruning can generate more vigorous growth in our plants. Perhaps, plague has played this role for humanity over the millennia?

Plague Presence In History

“The plague has afflicted humanity for thousands of years. Molecular studies identified the presence of the Y. pestis plague DNA genome in 2 Bronze Age skeletons dated at roughly 3800 years old. In the biblical book 1 Samuel from approximately 1000 BCE, the Philistines experience an outbreak of tumors associated with rodents, which might have been bubonic plague. Scholars identify 3 plague pandemics. The first pandemic or Justinian plague probably came from India and reached Constantinople in 541-542 CE. At least 18 waves of plague spread across the Mediterranean basin into distant areas like Persia and Ireland from 541 to 750 CE.”

- (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7513766/)

The evidence suggests that there were people who knew or strongly suspected the culprits carrying the infectious agents at the time. However, those writing the histories which have survived are most often religious scribes attributing most everything to a divine source fitting their theistic world view. Thus, we get a very skewed vision of the past not only in relation to plague but most everything else too. If all you have is an imaginary hammer then everything looks like an imaginary nail. The stories we believe dominate our thinking and how we see the world. Even when, our loved ones are dying a terrible death with bursting blood filled buboes, we seek soul filled answers to these ‘in your face’ calamities. Few of us can remain with the material facts of the matter without seeking solace in imaginary realms.

Travelling The Black Death Express

Modern human beings like to travel, even when there is no demanding reason to do so for their livelihood. We saw the much ado about this when Covid-19 shut down the world’s airports for all but essential services. Plague and pandemics are spread via this travel over vast distances very quickly. Our love of recreational travel is a major reason why infectious diseases will be capable of becoming global pandemics for the foreseeable future. For some of us the very idea that we can jump on a plane and fly somewhere far away is a part of being human in the 21C. Cruise ships became floating citadels of infection during Covid and still folk are keen to jump back aboard them today. Short memory my friend!

Cargo and freight are other means for plague causing agents to spread their deadly disease around the world. In previous millennia, it was the great sailing ships that carried the rats and their fleas from port to port over the seas. These hardy maritime travellers were decidedly effective in spreading the Black Death throughout the Mediterranean and beyond. Fabric could be a host for flea pupae which can survive for up to 5 months. Animals being shipped can play host to infected adult fleas and provide them with blood to live off during their journey. Travel and trade are the best friends of plague and pandemics.

Human Immunity & The Black Death

When thinking about how the Black Death shaped humanity over the millennia it reminds us all that we are only a part of something much larger than ourselves. Our fate, as a species of primates, is inextricably linked to the pathogens which affect us. They have impacted upon our survival as individuals and as societies and populations. Yersinia pestis has feasted upon us and changed the way we live our lives at various stages of our development in a variety of locales. It has brought great tragedy upon the lives of individuals and families, often cutting short lifespans. This disease generating bacterium has culled the populations of our cities and towns over the millennia. Indeed, the Black Death has affected our immunity over the many centuries.

“results suggest that the Black Death influenced the evolution of the human immune system. “When a pandemic of this nature—killing 30 to 50% of the population—occurs, there is bound to be selection for protective alleles in humans,” Poinar says. “Even a slight advantage means the difference between surviving or passing. Of course, those survivors who are of breeding age will pass on their genes.”

However,

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen

When we experience something that changes our lives, many of us can recall every detail. We remember where we were at that precise moment, what we were wearing, exactly how we felt. We may remember small details, like what the weather was doing, or what we ate on that day. Many of my most prominent memories stand out to me because I remember every detail about them. I remember where I was the first time I heard Madonna’s Ray of Light album (sitting on the floor of my parent’s house, in my pyjamas). I remember what I was wearing on the night I first met my husband (a black jumper and jeans). I remember what I was doing and what time of day it was when I received the news that my Nan had died (getting ready for work at about 6:45 in the morning, on a dreary, cold day in December). I remember looking out of the window just after learning that my Uncle had passed away, and thinking how dark it suddenly seemed outside, as if all the lights had been switched off . I remember the feeling of lightness that came over me when I finally found the courage to leave a job that was so stressful it nearly ended my life. I remember the flash of terror that coursed through my body when I was called into a small room for the result of my first mammogram in 2020.

I also remember the first time I discovered Northanger Abbey.

It was an ordinary day, not long after I moved to Newcastle upon Tyne to study a degree in English Literature. An item was missing from the inventory of our newly rented flat, and the university authorities accused me of stealing it. I had spent much of the day defending myself against these allegations, since a) I am not a thief, and b) I had never seen the offending item, much less stolen it. So it is safe to say that I was not in a good mood. In the late afternoon, I decided to cheer myself up by studying the syllabus of my course. And there it was – a little book called Northanger Abbey.

I have delayed writing about Jane Austen until now. Austen is without a doubt my favourite writer of all time, and probably the writer who has had the biggest influence on my life. I wasn’t certain that I could do her justice, and in addition I was keen not to turn this series into another “I love Jane Austen” piece. I find it very difficult to articulate just how big an influence Jane Austen’s work has had on my life. As a teenager, I dabbled in Austen the way some teenagers dabble in cigarettes or weed (I could not have been less interested in either). The first time I read an Austen novel in full was shortly after that dreary Tyneside afternoon, studying my degree syllabus. It read like a run-through of the greatest works of literature ever published: Moll Flanders, Jane Eyre, TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, Beloved by Toni Morrison. And Northanger Abbey.

In all honesty, next to the likes of Beloved, Northanger Abbey didn’t sound like the most exciting read. A coming-of-age tale about a 17 year old girl away from home for the first time, Northanger Abbey follows the life and loves of Catherine Morland, who navigates the world through friendships, romance and her love of Gothic literature. A parody of the Gothic novels that were popular during Austen’s day, it sounded to me a bit Mills and Boon, a flimsy romance novel that I would probably read quickly and forget just as quickly.

What I failed to realise at 18 years old was that the text was included on the degree syllabus for a reason. It was inserted into my life with an almost comic deliberateness. At 18, I too was experiencing the world for the first time on my own terms. As it turns out, I identified with Catherine Morland in many ways. I knew very little about the world. I felt a sense of responsibility to make a success of my new life. And, like Catherine in the novel, I may have been very good at reading books, but when it came to reading people, I was distinctly inexperienced. I viewed the world through a very different lens to the one I use today. Like Catherine, I placed great importance on wanting to be liked, and wanting to be seen as a good person by those around me.

Of Jane Austen’s heroines, Catherine Morland is the youngest, and the most naïve. She experiences situations common to many young adults: peer pressure, to join her friends Isabella, James, and John on their carriage rides, and bullying, in the form of her odious suitor John Thorpe. She becomes sulky and irritable on returning home to her parents (understandable, since her mother really is the most dreadful nag). She wants to be liked by her friends (particularly the vivacious Isabella Thorpe) but is not keen to be seen as a flirt, or risk situations that may lead to her disgrace. She wants to be respected by her friend, the 26-year-old parson Henry Tilney, but on a visit to the Tilney’s family home (the Northanger Abbey of the title) her overactive imagination leads her to fear that something terrible may have happened there. She must ultimately learn to separate life from fiction, and live her life in the real world, not as in a Gothic novel.

Northanger Abbey was an important novel in my life because its themes subconsciously appealed to me, in terms of where I was at in my life. Having re-read it several times since, I can see that in many ways it is as relevant today as it would have been in 1817. It is essentially a novel about young adults, and the journey to adulthood. Young people and their feelings are a central theme of Northanger Abbey, as is the path from innocence to experience. This is something that absolutely took place for me, in the 3 and a half years I lived in Newcastle upon Tyne.

There is a certain school of thought that all of Jane Austen’s novels are the same. They explore similar themes, they are similarly paced and all follow a similar plot trajectory (the heroine desires love and acceptance, she meets a man who turns out to be unsuitable, and eventually marries the man whom she dislikes or who acts as a confidant throughout the novel). Her heroines are similar in tone and in terms of their relationships with others. There are no really villainous characters in Austen’s novels – there is no one like Heathcliff or Mr. Rochester (although Mr Darcy gives them a run for their money). Characters commit sins against decency and propriety, but rarely deliberately hurt others. The heroine does not fall passionately, violently in love. Love is a gradual feeling; courtships are polite and almost imperceptible to those outside of the relationship. The heroine ultimately marries a man who is essentially a friend or confidant first and a lover second.

Austen’s novels also have a reputation for being difficult to read. I personally don’t find this to be the case. I think about the first time I read Northanger Abbey and find similarities to when I fell in love with my husband. It was easy. It was effortless. The simplicity of it was quite disconcerting! I couldn’t help feeling that he, like Jane Austen, had been a part of my life forever.

It is worth noting that parts one and two of the novel are very different. Part One tells the story of Catherine’s time in Bath with Isabella Thorpe and their friends, and Part Two depicts her time at Northanger Abbey with Henry Tilney and his sister. I’ve heard Northanger Abbey described a long time ago as a “blast”, and that’s exactly what it is. It doesn’t try to be high-brow or ruminate too deeply on the issues of the time. Instead, it is fun. I was right there with Catherine as Northanger Abbey and its locked rooms, mysterious chests and secret history intrigued and frightened her in equal measure. I couldn’t help but wonder if the novel was heading towards a very different ending, as Catherine wonders if the elderly Mr Tilney was responsible for his wife’s death. I rooted for her and hoped that she would marry Henry Tilney at the end (spoiler alert – she does). I hoped that they would live a happy life together in his parsonage.

Jane Austen is without a doubt the author of my life. We shall be exploring her other works in due course, including a modern biography. I have researched her to great extent, and paid many visits to Hampshire and Bath, which both have great significance to her life and novels. Her mysteriousness fascinates me. As other Austen fans may be aware, there is a lot we don’t know about Jane Austen. Her sister Cassandra sadly destroyed most of their correspondence, robbing the world of a valuable legacy and insight into their life together. I would loved to have met her. I would like to find out what made her tick, how she could write so beautifully about love and its complexities without ever having married or found love herself. Perhaps she did find love and lost it? Perhaps, like her heroines, she refused to marry a man she did not love? What would she have made of the impact her work has had on modern literature?

There is much more that I can say on Jane Austen – revealing my full thoughts and feelings, and a more detailed exploration of her influence on my life would probably lead to a much longer piece.

I will close by saying that if you have never read Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey is a good place to start. It lacks the gravitas and heavier themes of Pride and Prejudice, or the memorable characters of Emma, but it is light, (mostly) cheerful, and most importantly, it will make you laugh.

And that is as good a place to start as any.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I wish I had a needle and thread

Fine as I could sew

I'd sew that pretty boy to my side

And down the road I'd go

- Shady Grove, Among the Oak & Ash

Fished a sketch of Moll Flanders out of my drafts folder for today. I didn’t expect to finish it so soon but I’m very pleased nevertheless. It was good fun!

Support me here!

#Moll Flanders#the fortunes and misfortunes of moll flanders#alex kingston#Daniel defoe#meluisart#IRONICALLY THE TEXT FOR MY SIGNATURE IS THE SAME FONT AS MY TATTOO ASDFGHJKL#I didn't realise until just now#oh well

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading moll flanders is an experience because the language is like definitely 17th century but it’s weirdly capitalised like a tumblr shitpost

#it’s a lil trippy is all i’m saying#moll flanders#classic lit#daniel defoe#shut up georgia#dark academia#text

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

for my purposes, the referenced texts E.M. Forster made in his book, The Aspects of the Novel.

William George Clark. Gazpacho: Or Summer Months in Spain.

—. Peloponnesus: Notes of Study and Travel.

—. The Works of William Shakespeare - Cambridge Edition.

—. The Present Dangers of the Church of England.

John Bunyan. The Pilgrim's Progress.

Walter Pater. Marius the Epicurean.

Edward John Trelawny. Adventures of a Younger Son.

Daniel Defoe. A Journal of the Plague Year.

—. Robinson Crusoe.

—. Moll Flanders.

Max Beerbohm. Zuleika Dobson.

Samuel Johnson. The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia.

James Joyce. Ulysses.

—. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

William Henry Hudson. Green Mansions.

Herman Melville. Moby Dick.

—. "Billy Budd".

Elizabeth Gaskell. Cranford (followed by My Lady Ludlow, and Mr. Harrison's Confessions).

Charlotte Brontë. Jane Eyre.

—. Shirley.

—. Villette.

Sir Walter Scott. The Heart of Midlothian (part of the Waverley Novels).

—. The Antiquary (part of the Waverley Novels).

—. The Bride of Lammermoor (part of the Waverley Novels).

George Meredith. The Ordeal of Richard Feverel.

—. The Egoist.

—. Evan Harrington.

—. The Adventures of Harry Richmond.

—. Beauchamp's Career.

Leo Tolstoy. War and Peace.

Fyodor Dostoevsky. The Brothers Karamazov.

William Shakespeare. King Lear.

Henry Fielding. The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling.

—. Joseph Andrews.

Henry De Vere Stacpoole. The Blue Lagoon (part of a trilogy; followed by The Garden of God and The Gates of Morning).

Clayton Meeker Hamilton. Materials and Methods of Fiction.

George Eliot. The Mill on the Floss.

—. Adam Bede.

Robert Louis Stevenson. The Master of Ballantrae.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton. The Last Days of Pompeii.

Charles Dickens. Great Expectations.

—. Our Mutual Friend.

—. Bleak House.

Laurence Stern. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman.

Virginia Woolf. To the Lighthouse.

T. S. Eliot. The Sacred Wood.

One Thousand and One Nights.

Emily Brontë. Wuthering Heights.

Charles Percy Sanger. The Structure of Wuthering Heights.

Johan David Wyss. The Swiss Family Robinson.

D. H. Lawrence. Women in Love.

Arnold Bennett. The Old Wives' Tale.

Anthony Trollope. The Last Chronicle of Barset.

Jane Austen. Emma.

—. Mansfield Park.

—. Persuasion.

H. G. Wells. Tono-Bungay.

—. Boon.

Gustave Flaubert. Madame Bovary.

Percy Lubbock. The Craft of Fiction.

—. Roman Pictures.

André Gide. The Counterfeiters.

Homer. Odyssey.

Thomas Hardy. The Return of the Native.

—. The Dynasts.

—. Jude the Obscure.

Anton Chekhov. The Cherry Orchard.

Oliver Goldsmith. The Vicar of Wakefield.

David Garnett. Lady Into Fox.

Alexander Pope. The Rape of the Lock.

Norman Matson. Flecker's Magic.

Samuel Richardson. Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded.

Anatole France. Thaïs.

Henry James. The Ambassadors.

—. The Spoils of Poynton.

—. Portrait of a Lady.

—. What Maisie Knew.

—. The Wings of the Dove.

Jean Racine. Plays.

I. A. Richards.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moll Flanders and the Gatekeeping of Female Liberation.

Throughout the literary production of the eighteenth century, one can find a very constricted representation of female characters which are shaped as either one of two: "women as angels and women as whores,... women as the embodiment of moral value and women as the source of moral disorder" (Jones 57). However, these categories, explains Vivien Jones in her book Women in the eighteenth Century: Constructions of Femininity, are "actually ideologically inseparable" (57). This is because femininity and its different extremes exist as prouduct contained within masculine parameters as Margarita Pisano suggests, "la feminidad no es un espacio aparte con posibilidades de igualdad o de autogestión, es una construcción simbólica, valórica, diseñada por la masculinidad” (28). For this reason, texts of the period that may appear transgressive at first glance due to a female character choosing to embrace one of these two extremes are not really portraying liberation from the boundaries established by patriarchal structures but are actually promoting the compliance to them. This is the case of Moll Flanders (1722) by Daniel Defoe in which he presents a repented female narrator that recalls the mistakes she made in her past that led her to a path of crime and, ultimately, repentance and happiness. In this way, I argue that the subversive aspect of the novel acts more as a resource for Defoe to emphasize his moralistic views regarding the role of women.

In Moll Flanders, Defoe touches on moral issues that involve men and women equally, making it sound subversive from a female narrator, such as when she comments on her having to marry her lover's brother, "so certainly does interest banish all manner of affection, and so naturally do men give up honour and justice, humanity, and even Christianity, to secure themselves" (Defoe 88). Although it is evident that men are being judged under the same moralistic parameters, the novel centers on mantaining the status quo for women as the protagonist and narrator is Moll. In that way, Defoe lays out the duty of marriage and the birth of children —as the amount of times she married and had children shows. This view Defoe portrays on the role of women is also laid clear in his text Considerations upon Street-Walkers with A Proposal for lessening the present Number of them, where he "defends marriage by defining ‘the great Use of Women in a Community’ as being to ‘supply it with Members that may be serviceable’, and makes the startlingly utilitarian suggestion that women over child-bearing age should not be allowed to marry since that ‘loses to the World the Produce of one Man’ (Jones 58). In this way, the novel can be contradictory and complex because of what it shows and what it is trying to convey; thus, the first-person narrator and the sympathy it produces "complicates any simple moral conclusion and disrupts his functional objectification of women" (Jones 60). This contradiction is, then, a result of Defoe's didactic approach to writing, doing it from a Christian point of view in which forgiveness can always be attained through repenting. Moll's character is constructed in a manner that makes it open to interpretation, since it is necessary for the reader to go through the same process and realize on its own account the importance of repentance. It can be said that Defoe's writing is exemplary of how one can reach "the masses", as he probably knew the growing popularity of criminal biographies at the time.

Finally, just as Moll enters a world of crime and is actually out of the limits that constrain women, that is, she is not married nor a prostitute, she is imprisoned and shows herself in a mindset that does not trap her in the limits of femininity. While being imprisoned, she was free of any expectations that may have restrained her in the past as she expresses,

“a certain strange Lethargy of Soul possess’d me, I had no Trouble, no Apprehensions, no Sorrow about me, the first Surprize was gone; I was, I may well say, I know not how; my Senses, my Reason, nay, my Conscience were all a-sleep; my Course of Life for forty Years had been a horrid Complication of Wickedness; Whoredom, Adultery, Incest, Lying,Theft ... and now I was ingulph’d in the misery of Punishment, and had an infamous Death just at the Door, and yet I had no Sense of my Condition, no Thought of Heaven or Hell at least" (Defoe 280)

"I was cover’d with Shame and Tears for things past, and yet had at the same time a secret surprizing Joy at the Prospect of being a true Penitent, and obtaining the Comfort of a Penitent, I mean the hope of being forgiven; and so swift did Thoughts circulate, and so high did the impressions they had made upon me run, that I thought I cou’d freely have gone out that Minute to Execution, without any uneasiness at all, casting my Soul entirely into the Arms of infinite Mercy as a Penitent..." (Defoe 289).

However, as it should be expected, having into account Defoe's interests, Moll has an encounter with one of her past lovers and chooses to repent in order to be with him. After not having any burdens on her as she knew her death was near, she feels the weight of her sins once again when she knows she would marry again and would have to go back to society and comply to the norms. Therefore, she proudly becomes a penitent,

Moll Flanders is a complex novel precisely because of this openness of interpretation that Defoe plays with and can be read as disruptive to a certain point. However, in the end, a female character recognizing its difficulties and differences in comparison to men is hardly empowering when the ending of the novel presents a married Moll who acknowledges that her past was sinful so she happily repented. A female character acting independently outside the boundaries of what is permitted (that is, being a thief and not married) is hardly liberating when the author makes her comply in the end by her own accord, portraying a pseudo freedom that does not break any boundaries whatsoever. This shows how those that are in power control the narratives. and how they are only interested in maintaining the order.

In the end, not only does she embraces femininity but also Christianity, showing the power structures of the time.

Works cited:

Defoe, Daniel, and Paul A. Scanlon. Moll Flanders. Broadview Press, 2005.

Jones, Vivien. Women in the Eighteenth Century: Constructions of Femininity. Routledge, 2016.

Pisano, Margarita.El triunfo de la masculinidad 2004

Richetti, John. The Life of Daniel Defoe: a Critical Biography. John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Your Books Will Get Banned (Old Nanowrimo Post)

I used to post this game on Nanowrimo. I saved the text before Nanowrimo declared that the N-word spelled out was OK and this wasn’t a democracy (2010, in the archives, at the bottom). I figure it’s OK to post that unless they didn’t change their policy since then, because they want prejudice (though that wasn’t the worst of what they wouldn’t mod). Writing forums need to be run at the top by diverse people, and not just white women. Separate post though. BTW, I have witnesses who still remember this incident, so it isn’t slander. I was working on diversity in the writing forums before WeNeedDiverseBooks was a thing and squandered the opportunity by making it only YA. And I’ll still call them out for that.

It got challenged, this thread once, much to the laughter of everyone. (for being anti-Christian lol) If the writer is out there that challenged the thread and somehow got published. Thumbs up, good for you. Maybe you revised since then?

The thing I didn’t post with this post every year from 2005-2010 I did this post was I posted it because I wanted people to think hard on Free Speech and what it meant. So I’ll hardball it this time. As you read the list, think hard on who is gate keeping. And who has the right to gate keep. Is gate keeping a tool to oppress and do the power minorities have a right to use the same tool back? How many books don’t even get a chance to be published? I’d also add that chasing after individual authors for the last 10 years has done nothing to change the system. The percentages are the exact same. And how that affects what people in the future will think of us now. Can you write a book that won’t be challenged on these fronts at all? And if you’re going to say, “You’re anti-cancel culture” This was posted before “cancel culture” was a thing. This is more like an examination of the system of censorship itself. (Because look, I like examining systems.)

If you want to take this list, BTW, this is years and years of my work reading through ALA who never compiled this list. I’d been following the list since High School when I did a banned book class (which was a fad of the time, I think). So... maybe, give me credit? I feel sad I have to say that.

And thanks to Jakob Nielsen and my Typography prof for teaching me the way to format text.

This thread was originally started in honor of ALA Banned Book Week. I've started this several years in a row.

Disclaimers for this thread: ('cause I've done this for a few years)

1. We do not support the idea of banning/challenging books.

2. We are doing this for fun and it should not be taken seriously.

3. If you are seriously offended by the fact that we would write these scenes into books please consider the following:

a. It is out of context.

b. You probably unwittingly own a banned book without knowing it. Please check the list: <a href="http://www.ala.org/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks">http://www.ala.org/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks</a>

c. We are not popular enough to get our books banned, and by hoping in a weird way that they will get banned, you are helping our egos. ^.~

d. If you are religious, the Qu'ran, the (I think Ramayana), the Torah, the Bible all have been challenged or banned. (KJV of the Bible if you plan to be snooty, by even more ironically Jews once, and Atheists the second time). (The Art of War, I also believe was challenged/banned.) (And also, the Bible probably contains more than half of the issues that Christians ban other books for. Christians banned Moll Flanders. All the issues the banned Moll Flanders for is in the Old Testament. Particularly Genesis)

4. This is not a thread for hot debate on the moralities of book banning. It is for listing why you think your book will get banned. If you would like to do so--please start a separate thread. You don't have to stick to Nanowrimo for this thread either.

General Notes: ('cause I like to point out the humor)

- This thread was challenged and asked to be banned before. (Because someone was offended by the contents.) The challenge failed, BTW, just in case you'd like to challenge it again.

- You probably have to write Young Adult and under to get banned *most* of the time.

- Asterisks indicate new ones for the year. (BTW, most of it is about Islam, this year... sex and violence of course)

Want to avoid getting banned/challenged? (Categorized by how the banners see it for maximum head desk based on real book challenges and bannings.)

RELIGION

You can't talk about religion.

-- No taking the Lord's name in vain.

-- You can't have anyone question the will of God or curse them when they lose faith after losing their best friend. (Bridge to Terabithia)

-- Anything from Islam

--- Cannot include Islam, even as a text book, because it will "indoctrinate the students into the Islamic religion." even if you are only covering it as a chapter. * (World History by Ellis, Elisabeth Gaynor and Anthony Esler.) *

-- Anything (fill in your religion here.) because some people are (fill in your exclusionary term here)

-- Atheism (though not a religion, still argued by the theists as one. =P)

-- You can't swear, including the word "damn."

-- A boy and a girl can't live together if not related, because it's obviously living in sin.

-- Can't be detrimental to Christian values.* (The Handmaids Tale, which is BTW, based on a Biblical story...)

(The Bible, Torah, Qu'ran and many other religious books have been banned. Yes, if you have a religious book, it has most likely been banned or challenged.)

SOCIAL INEQUALITY

You can't talk about class or classism.

You can't talk about race.

-- You can't use racial slurs.

-- You can't talk about racism.

-- You can't have a black bunny marry a white bunny because that's supporting interracial marriage. (The Rabbit's Wedding, though Once Upon a Time in Wonderland also does this explicitly... must have enraged the challenger.)

-- The book can't be deemed racist in any fashion.

-- You can't talk about Mexican-American issues or history. (Apparently it's a lie that Mexican Americans get racism. *cough*) (Arizona Governor, though it was overturned later).

-- You cannot have a Person of Color explicitly on the cover of the book. (Barnes and Nobles pulled that off with Cindy Pon's Silver Pheonix--not to mention all the other publishers.)

No talking about over eating, bad eating habits.

No talking about disabilities including cerebral palsy.

Can't be sympathetic to Armenians or for portraying Azerbaijans as "savages" [book burner's words] (because apparently you will get a $12,700 price on your head to *cut your ear off* for being historically accurate.) (Stone dreams by Aylisli) *

QUILTBAG Issues:

-- You can't talk about sexuality. (As in the willingness to have sex).

-- You can't talk about sexual orientation. (As in Straight LGB)

-- You can't talk about gender identity issues unless it is cis and not crime investigation kind either.

- Main character cannot have two fathers. (The Popularity Papers by Amy Ignatow)

Magic Issues:

You can't have talking animals. (Peter Rabbit.)

Oh, no magic, no mention of witches, and no fantasy (That promotes Satanism and teaches them to do evil satanic spells). (Harry Potter)

VIOLENCE

Children can't do violence, especially to adults or to each other. Especially school violence.

You can't have kids doing stunts or possibly hurting themselves.

No realistic depictions of the Vietnam War.

Can't be Graphic.* (The House of the Spirits)

- Cannot have violent illustrations.* (The Librarian of Basra by Jeanette Winter and Nasteen's Secret School by Jeaenette Winter)

No dysfunctional families.

-- You can't talk about child abuse.

No characters may ever die.

-- No dead parents.

-- No dead siblings.

-- No dead best friends (Even if you are a Christian author, other Christians will come after you). (Bridge to Terabithia)

-- No dying adults.

-- You may not mention anyone dead (already) or dying (currently).

-- No young infants dying.

-- No talk of euthanasia.

You can't have any mention of cannibalism. (Alive, etc)

DRUGS

You can't mention any drugs, including alcohol, especially with teenagers drinking it. (The Perks of Being a Wallflower--though there are many others)

--- Children can't carry alcoholic beverages.

GENERAL MORAL OBJECTIONS

You can't have it be morally corrupt.

-- You can't have monsters of any kind. (Where the Wild Things Are)

It can't be a "Downer" (Anne Frank)

And by all means it can't be "icky." "gross" or "scary" (Goosebumps)

Can't be perceived as Anti-feminist.*

You can't be a PoC and write something negative about being a PoC.* (The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian)

- Cannot have "inappropriate content" (Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman [Welcome to the banned books club, Mr. Gaiman.])*

- You cannot have a single mother. (The popularity papers by Amy Ignatow.)*

- Cannot be a "Bad book" that "one shouldn't be associated with."* (Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison)

- Cannot have "an underlying socialist-communist agenda."*(Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison--note it was challenged in her own home state for this....)

- Cannot have a book that goes on about "developmental preparedness" (i.e about children developing?) and "student readiness." (The Story of a Childhood by Marjane Satrapi)*

No children defying authority figures.

-- No cursing at parents.

-- No disobeying parents.

-- You can't have kids breaking dishes (especially to avoid washing them). (A Light in the Attic)

No toilet humor.

You can't have characters eating worms, because that's unsanitary. (How to Eat Fried Worms)

SEX

Your book can't mention any private parts.

You can't mention body parts (this was how it was phrased. --;;)

-- Even if you have drawings of lots of people on the beach, not even one of them, even when drawn at 2cm x 2cm can be topless, even as a joke. (Where is Waldo)

-- No talk or showing of nudity. (even when private parts aren't shown)

-- You cannot teach sexual issues in your book to middle school students. * (The Middle School Survival Guide)

You can't have masturbation or any mention of sex.

-- No beastiality

-- No showing of safe sex. (Apparently Teen pregnancy is still A-OK, but safe sex isn't! --;;)

-- And you can't use any words with "tit" in them. (Title will now be called tidle just not to offend anyone.) (Harry Potter)

Rape may be seen by banners as a type of porn. (I see it as violence, but the banner saw it as titilating sex. --;; *gags*) (Speak)

AUTHOR CAN'T BE...

-- LGBT (Asexuality, apparently, is still safe.)

-- You can't have the same name as anyone connected to "Socialism" or "Marxism." (Texas School board)

Good luck getting it published.

So yes, this was started as satire. If you have any further questions about said history of said thread, you are welcome to PM me. Do not start it in the thread.

And please reply using the "reply" button at the bottom of the page, not this post.

Banned books for this year PDF: http://www.ila.org/BannedBooks/ALA016%20Short%20List%20L3c_low%20%281%29.pdf

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Revelations

Summary: You had been friends with Yugyeom just as long as his older sister had been your best friend. What you weren’t aware of was Yugyeom didn’t just see you as his friend.

Pairing: Kim Yugyeom x noona/older reader

Genre: friends to lovers au / fluff

Anonymous said:

Hi!! was wondering if you could write something with yugyeom having a crush on his older sisters best friend?? i need more yugyeom x noona content 😂😂 (ps i am obsessed with everything you write and find myself coming back to read them over and over)

Word count: 2329

You laughed when Yugyeom came into the living room and slumped down on the sofa you were sat upon dramatically. Poking him with your foot playfully, you smirked. “What’s wrong with you?”

“What else? School.”

“Well if you spent more time awake in classes, I’m sure you’d actually grasp what you’re being taught, Gyeom.” You scooted closer to him. “Which subject is it this time?”

“Don’t humour him, Y/N,” his sister and your best friend instructed upon re-entering the living space, shaking her head firmly. “He has to learn to do it himself.”

“So it was alright for you to get help with your schoolwork from friends, but not me?” the youngest of the three scoffed and you tried to hide your smile. You failed and patted his knee gently.

“Don’t worry, I’ll help you. But only this time.”

“That’s what you said last time, Y/N,” Yubin reminded sourly and let out a groan. “Stop hogging my best friend. She’s not your friend, Yugyeom!”

“Who gets to decide who’s friend she is, huh? Noona has always been my friend too!”

You held up your hands at the siblings and laughed lightly. “Hey, there’s no need to fight over me. There’s plenty to go around.”

Yugyeom smiled smugly at his older sister, who poked her tongue at him immaturely. You sighed, though you continued to smile. It had always been like this. Growing up together, it meant you had been in Yugyeom’s life for just as long as you had been in Yubin’s. Their family was loud and dramatic, unlike yours, and you naturally gravitated towards spending your afternoons and weekends at their house. You liked the bustle within their home and even now as you were wrapping up on your university degree, you still found yourself de-stressing whenever you were here. It was why you had suggested the movie marathon in the first place tonight. You were exhausted from cramming for mid-terms and needed to relax within good company. Despite their banter, Yugyeom and Yubin were close. You had always been jealous of their bond, not being as close to your own siblings. Perhaps it was because they were much too quiet compared.

Yubin suddenly sat up and looked at her brother pointedly. “Wait, why are you here? This was a movie marathon for us. Don’t you have other people to hang out with on a Saturday night?”

Yugyeom rolled his eyes, uncaring of the whine from his sister as he reached for some of the popcorn on the table. “In case you’ve forgotten, big sis, I live here too. I don’t have any plans for the night.”

“It’s a public domain of the house as well,” you mentioned and Yubin turned to look at you suspiciously. “What, you’re always on his case!”

“You’re too soft towards him, don’t encourage him.” Yubin then pulled her phone out of her lap and answered it, leaving the room as her voice grew sweeter, indicating it was her boyfriend on the other end.

Yugyeom scrunched his nose up. “Why is she so two-faced? I hate that voice she puts on for Mark-hyung.”

“I’m sure when you date someone, you naturally treat them affectionately.” Yugyeom glanced at you, his cheeks flushing lightly. You laughed and nodded. “See, you are aware of it.”

“No, I don’t do anything differently than how I am with you.”

“Well you treat me nicely, so I wouldn’t complain if I was your girlfriend,” you stated with a smile, looking back at the movie. You felt his eyes still attached to the side of your head and glanced towards him again. “Yugyeom, you okay?”

“Huh?” He blinked slowly and then seemed to come out of his stupor, rubbing the back of his neck awkwardly. “Right, just as if you were my girlfriend.”

“Who’s girlfriend?” Yubin asked when she entered the room and when Yugyeom wasn’t immediately forthcoming with an answer, she shrugged and looked over at you pleadingly. “So Mark’s been injured at work tonight and I need to go meet up with him, is that okay?”

“Of course, go!”

She glanced at you both; seeming satisfied you still had company. “Looks like your lack of plans worked out well. Don’t harass Y/N too much and get her whatever she wants to eat.”

“I have my own hands and know the way into the kitchen,” you replied with a laugh, Yugyeom still not responding to either of you. His change in mood was lost on his older sister who waved in farewell, the front door closing soon after she disappeared. You nudged Yugyeom. “Are you not in the mood for the movie anymore? We don’t have to watch it. We could do something else.”

“Oh, uh-”

“Didn’t you say you needed help with your school work? Let’s do that instead. We’re both kind of distracted from the movie now.”

Yugyeom stared at you again and right before you went to ask if he was okay, he seemed to relax, grinning over at you. “Would you? That would be such a big help.”

An hour later, you were deep into the throes of explaining Moll Flanders to Yugyeom. You stopped when you noticed that he wasn’t paying attention, a playful smile crossing your lips. “And then a unicorn appeared and had a disco party.”

“Yeah,” he said with a slight nod, frowning soon after. “Wait, what?!”

“So you are paying attention after all,” you mused and Yugyeom rolled his eyes. “I thought you were going to fall asleep.”

“Well, it’s not exactly comfortable studying here at the dining table.”

You nodded. “Do you want to go somewhere else? You’ve got a lot of texts up in your room, right? We can go up there and-”

“No!” he cut in, his cheeks flushing. You poked him again with a laugh.

“Why are you being so cute and shy tonight with me? You know I’ve seen your room multiple times when we’ve studied in there before. Heck, I still remember that time when we were teens and I walked in on you-”

“You promised you would never bring that up ever again!” he hissed vehemently and you laughed loudly. Yugyeom shook his head, insulted. “Noona, you’re not playing fair with me!”

“Why should I? Having dirt on you could benefit me in some way one day.”

He let out a dry laugh. “Have you forgotten I’ve got equal amounts of knowledge of what you’ve done over the years?”

“Oh yeah? Like what?” you challenged and Yugyeom’s previous boredom was soon erased. His eyes glistened with mischief and you eyed him carefully.

“Like that time one summer where your bikini top came undone and you had to hide behind the bushes for an hour whilst Yubin and Mark-hyung played in the pool because you couldn’t grab your top in time and got frightened. Had I not come to your rescue, what would you have done, huh?”

You instinctively clutched at your chest with the memory resurfacing and shuddered. “I paid you back by pretending to be your girlfriend last year when that girl wouldn’t stop stalking you.”

“She still thinks we’re dating,” he mentioned softly and you grinned. “Doesn’t that bother you?”

“As long as she’s not harassing you, I’m fine about it.”

“You know that Jinyoung-hyung wanted to ask you out but heard about us so he hasn’t, right? You could be potentially missing out on a boyfriend right now.”

“Wait, what?!”

Yugyeom smirked. “He really liked you too. A shame he’s moved on now with Jem, right?”

“Why didn’t you tell him the truth?!” you asked and the tall boy shrugged. “Yugyeom!”

“What are you going to do about it?”

“You need to tell all your friends I’m single! Right now!”

“It’s nearing midnight, Noona. I’m not going to message anyone.”

“Where’s your phone, I’ll do it!” Your eyes searched the spread before you on the table and then looked at Yugyeom. His gaze gave him away by looking to his sweats and you jumped up from your chair, rounding the table in haste. He was just as quick, however, shifting back with a chuckle.

“What are you going to do, fish it out of my pocket?”

You nodded adamantly. “That’s exactly what I’m going to do, so come here!”

Yugyeom instead took off around the house and you followed in pursuit, screaming at him to give you his phone. You thumped upstairs and through his open bedroom door, grinning when he cornered himself. Yugyeom darted his focus to the door and went to dash for it. You leapt up onto the bed and reached out for him, yanking him back with the help of his t-shirt.

Breathlessly, you laughed in triumph. “Going somewhere?”

“You have to get it off me first,” he answered, breathing just as heavy as you.

“I’ll use any tactic necessary,” you grunted, trying to avoid his hands grabbing at yours with every chance you tried to take to get into his pocket.

Eventually, your arms became tangled and Yugyeom let them go, instead holding you to his chest. You smirked. “Bad move, my hand is free to reach down.”

“Can’t you just let everyone still think we’re dating?” he asked, his tone serious. You paused in your efforts, frowning when you couldn’t find a trace of humour in his face. Yugyeom let out a heavy breath. “We’ve known each other for years and yet you’re still blind to the crush I have had on you forever, right?”

“Wait… crush?” you echoed and Yugyeom shook his head incredulously. You attempted to laugh. “Hey, if this is your way of preventing me from-”

“Can’t we make it go from fake dating to something real between us?” he continued and you stopped talking altogether. “Do you really just see me as some kid that’s followed you and my sister around all these years?”

“You’re not a kid,” you countered but you diverted your gaze at the same time. You were becoming acutely aware of how much he had transformed from the boy you’d known all your life. His chest was too firm, and his arms strong. You gulped and tried to push away from him. Yugyeom let you with a sigh but your force sent you into a seated position on his bed, stunned.

“But I’m not a man, right?”

“I don’t know what you are to me,” you admitted and then glanced up at him. “Are you sure you’re not confused with how much of a show we had to put on last year? I mean, I even kissed you that one time.”

Yugyeom smiled weakly as he sat down beside you. “It’s been over five years now.”

“T-that long?!” you squeaked out, your eyes widening with his announcement. How had you been blind to it? You racked your brain for any tell-tale signs and apart from the blushes he would now and then succumb to, he just seemed like regular Yugyeom to you. Looking into his warm brown eyes, you tried looking for signs there instead. And it was as you stared deeply at him that you realised all the little things you loved about him. His face was gentle and welcoming, and the small smile on his lips made you smile too. Yugyeom reached out for you slowly, linking his hand with yours.

“Are you realising it yet?”

“Your sister would kill you for having a crush on me.”

“Yubin is all talk. She loves me as much as she does you. Who better to look after and protect you than me, huh?”

“You can protect me? From what?”

Yugyeom grinned cheekily. “From the likes of Park Jinyoung.”

You rolled your eyes. “That’s immature!”

“So, you still like it,” he mentioned and you nodded before you realised it. His smile grew wider. “You like me.”

“Are you stalling on kissing me by talking so much or should I figure this out by making the first move?” you wondered impatiently and with a chuckle, Yugyeom lowered his head before capturing your lips in a soft, lingering embrace. You remembered how you had kissed him last year, albeit that kiss was quick and purposeful. And whilst there was purpose to the reason for kissing Yugyeom now, it was vastly different from your memory of the previous one. Everything inside of you felt as if it was burning hot, and as the kiss grew passionate, you realised that deep down there didn’t need to be any sign to show you how much you liked Yugyeom. You had always liked him. He was your friend, your shadow at times, and your confidante. You would never admit to Yubin just how many secrets you hadn’t told her but her brother instead.

Though you would need to tell her about this, given the fact that you were pretty sure you couldn’t stop kissing Yugyeom now that you had started. When he finally pulled away, you were somehow underneath him on his bed, his hand ghosting the thin strip of skin that was showing from your top riding up getting into this position. You reached out to cup his cheek in your hand and smiled. “Anything else you want to tell me tonight? Or was the crush the only thing I need to worry about?”

Yugyeom chuckled, turning to kiss your palm gently before grinning at you. “About that homework, I already submitted my Moll Flanders essay three days ago.”

You let out a short laugh, shaking your head softly. “You faked needing help?”

“All these years,” he confirmed cheekily and you feigned annoyance. “Should I ask for forgiveness?”

“I could think of a few ways to punish you,” you mentioned airily and his eyes widened. Then you groaned. “However, after kissing you like that, I don’t want to hold back because then it’ll be me who suffers too.”

Yugyeom moved to kiss you again. “Well, I don’t want you to suffer; it’s been far too long waiting for this moment to arrive.”

_________________

All rights reserved © prettywordsyouleft

[GOT7 Masterlist] | [Main Masterlist] | [Request Guidelines]

#kim yugyeom#yugyeom#got7#got7creators#kwritersworldnet#got7 imagines#got7 scenarios#got7 fiction#got7 fanfic#got7 friends to lovers#got7 fluff#yugyeom imagines#yugyeom scenarios#yugyeom fiction#yugyeom fanfic#yugyeom fluff#got7 au#yugyeom au#kpop imagines#kpop scenarios#kpop fiction#kpop fanfic#kpop fluff#prettywordsyouleft requested#prettywordsyouleft writes

423 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was checking my copy of Moll Flanders against the Project Gutenberg version, and my initial search produced:

lol

#this is always a pretty inane approach to literature but...uh.......#i study early modern & 18th century literature because the intersection of those eras' domestic life w/ absolutely unhinged shit is great#(other reasons but that's the lizard brain reason)#so the whole ... bringing the moralizing knife to the gun fight approach seems very strange!#isabel talks#text: moll flanders#artist: daniel defoe#academic chatter#british lit chatter: long eighteenth century

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eamonn Carrabine, Imagining Prison: Culture, History and Space1, Prison Serv J 15 (2010)

In this article I explore the diverse ways in which stories of prison and punishment have been told in the literary and visual arts. Stories of crime and punishment are central to every society as they address the universal problem of human identity. Every culture generates founding myths to account for society’s origins, typically situated in some dreadful primordial event. The imaginary origins of Western civilization are to be found in tales of banishment, confinement, exile, torture and suffering. The theme of exclusion is symbolically rich and spaces of confinement — both real and imagined — have provided stark reminders of human cruelty and reveal just how thin the veneer of civilization can be. This article examines how prison space has been represented in the literary and visual arts so as to grasp the complex cultural landscapes of punishment.

Old Prisons

Before the eighteenth century imprisonment was only one, and by no means the most important, form of punishment. The old prisons were very different places from the new penitentiaries replacing them later in the century. Until then hanging was the principal penalty, with transportation abroad the main alternative, while whipping remained a common punishment for petty offences. The defining features of the old prisons are summarized2 as follows:

At mid-century in England, petty offenders were hanged or transported for any simple larceny of more than twelve pence or for any robbery that put a person in fear. The typical residents of eighteenth-century prisons were debtors and people awaiting trial, often joined by their families ... Most prisons were not built purposely for confinement, but all were domestically organized and the few specially constructed ones resembled grand houses in appearance (e.g. York Prison, c. 1705). Prisons were temporary lodgings for all but a few, and the jailer collected fees for prisoners for room, board, and services like a lord of the manor collecting rents from tenants.

A number of points are emphasized here. First, over two hundred crimes (ranging from petty theft to murder) were punishable by death, under the ‘Bloody Code’ of capital statutes, as the political order sought to maintain power through the terror of the gallows. Second, prisons were often makeshift structures and many were no more than a gatehouse, room or cellar and rarely confined prisoners for any great length of time. The largest prisons were in London, where Newgate was the most significant, but others like the Fleet and Marshalsea were reserved almost exclusively for debtors. Third, the prisons were run as private institutions and ran largely for profit: prisoners were required to pay for the cost of their detention. The jailer had almost no staff and so prisoners were chained up in irons to keep control, while those who could afford it could buy relative freedom and even comfort — all at a price.

Whatever the conditions were actually like inside the old prisons, we see them persistently spoken of as places of evil, where profane pleasures, abject misery and infectious diseases all mingled in what seemed like a grotesque distillation of the world outside. In fact, many literary and visual sources drew attention to the failings of the legal system and mocked the rituals of punishment. An excellent example exposing the absurdities of the execution ceremonies is Jonathan Swift’s (1726/7) poem ‘Clever Tom Clinch Going to be Hanged’ that delights in the comic spectacle of the drunken Clinch making his ‘stately’ procession to the gallows and ultimately pointless defiance as ‘he hung like a hero, and never would flinch’. Although Swift was a Tory, he was a radical Anglo-Irish one, ambiguously caught between the colonizer and colonized, his satire mercilessly exposing the gulf separating the noble ideal from grim reality. The most damning example is his A Modest Proposal (1729), a pamphlet calmly advocating that the Irish poor should eat their children in order to solve Ireland’s economic troubles.

Early modern authors were drawing on, and occasionally, transcending already existing literary forms. Daniel Defoe is the archetype. Indeed, he was imprisoned many times, mostly for debt but occasionally over his political writings, including a five- month stretch in Newgate following the 1702 publication of his The Shortest Way with the Dissenters, a pamphlet mocking High Church extremism. Although this punishment was severe, more degrading to Defoe were the three visits to the pillory he endured as part of the sentence. By the 1720s he was successfully writing feigned autobiographies, including Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders, Colonel Jack, and Roxanna, which have become well known as amongst the first English novels. Moll Flanders takes the form of a gallows confessional and includes a spiritual rebirth in Newgate prison at the depths of Moll’s misfortune. In the book the prison is cast as a macabre gateway, yet in Moll’s case it does not lead to the gallows, but to a new life in the New World. Her crimes make her rich, and her penitence enables her to enjoy a prosperous life in Virginia. It is this heavily ironic structure that enlivens the text, but behind all the adventures lays the looming presence of Newgate, where Moll was born to a woman sentenced to death for shoplifting and to where sh inevitably returns. Like that other great picaresque novel from the eighteenth century, Tom Jones3 who was ‘born to be hanged’, the shadow of the gallows hangs over the central protagonist and the prison occupies a pivotal place in the narrative. The dramatic crisis is reached when the reckless but good natured hero ends up in the Gatehouse, following a series of amorous encounters and comic adventures, as a result of his half-brother Blifil’s treachery (who has Tom framed for robbery and sentenced to death). It is just at the darkest hour, when all seems lost, that Tom’s true parentage is revealed and the natural order is restored, enabling him to marry his childhood sweetheart.

Fielding’s fiction is much more tightly plotted than Defoe’s, and in doing so he exposes the distance between how things really are and how they ought to be. One suggestion is that in the real world Tom would have ended up hanged and the villainous Blifil may well have become prime minister4. An irony Fielding had earlier explored in his Mr. Jonathan Wild the Great (1743), where the notorious thief-taker becomes synonymous with Walpole’s leadership of Parliament — satirically drawing the barbed comparison between Wild’s criminal organization and Walpole’s manipulative control of government. There is a crucial tension between what actually happens in a Fielding novel, suggesting that the world is a bleak place, and the formal structuring of those events, implying pleasant symmetries, poetic justice and harmonic resolution. It is as if his earlier career as a successful comic playwright and later years spent as a harsh London magistrate combine to produce work obsessed with preserving traditional forms of authority, yet fascinated by the disruptive energy of the outcast.

Prisons of Invention