#tftbn

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

alright guys in order to transcend mortality we’re gonna have to put on the best damn talent show entropy has ever seen

#tftbn#alright guys to save the exemplary acolytes class from disbanding we’ve got to put on the best damn tal

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got caught up on The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere, a sprawling Umineko-esque post-postmodern murder mystery, a couple days ago. Highly recommend.

I've been working on an essay comparing it and Umineko, and delving into post-postmodernism and what differentiates it from postmodernism, and how popular culture is increasingly becoming the avant garde as so-called "high" culture retreats into a sort of literary white flight that is increasingly inward-facing and myopic, and how all of this dovetails into the themes of identity that are central to Umineko and Flower and perhaps the mystery genre as a whole, but it's all coming out quite expansive and confused at the moment. It might just wind up that way.

Anyway, read Flower, it bangs

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

#god.#tftbn#tftbn spoilers#this is a major spoiler but also completely nonsensical if u havent read most of flower

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time Running Out

#the flower that bloomed nowhere#utsushikome of fusai#tftbn#my art#og post#tftbn spoilers#the lady tftbn#uli tftbn#read flower. btw. really good novel

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

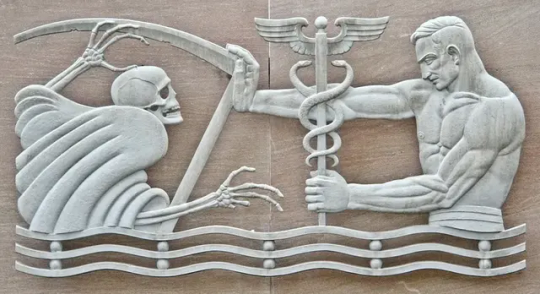

The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere, 000-012

Or, what if that mural was the heart of a web serial.

I'm reading The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere, thanks largely to the enthusiasm of @azdoine and @lukore on my dash over the last few months.

This is absolutely not gonna be a liveblog in the level of detail of the great Umineko liveblog project. Rather I'm gonna be aiming at something like the comics comints series or those occasional posts on anime. Or indeed what I wrote about Worth The Candle last year. I must create a robot whose purpose is to watch to see if I start writing detailed plot summaries and hit me with a stick labelled 'remember you have a job now'.

That outta the way, let's talk flower!

youtube

No, not that flower!

I will start with an anecdote. When I was at university, I ended up attending a talk by court alchemist senescence researcher Aubrey de Grey, who at that time did not yet have a 'sexual harassment allegations' section on his Wikipedia page. The main thing that struck me at the time was his rather spectacularly long beard. But I did listen to his talk about ending aging.

de Grey's schtick is that he, like many people in the transhumanist milieu, believes that medical technology is on the cusp of being able to prevent aging sufficiently well to prolong human lifespans more or less indefinitely. He believes that the different processes of aging can be understood in terms of various forms of accumulating cellular 'damage', and that these will begin to be addressed within present human lifespans, buying time for further advancements - so that (paraphrasing from memory) 'the first immortals have already been born'. He has some pretty graphs to demonstrate this point.

At that talk, one of the audience members asked de Grey the (in my view) very obvious question about whether access to this technology would be distributed unevenly, creating in effect an immortal ruling class. de Grey scoffed at this, saying he always gets this question, and basically he didn't think it would be a big deal. I forget his exact words, but he seemed to assume the tech would trickle down sooner or later, and this was no reason not to pursue it.

I'm sure de Grey is just as tired of being reminded of how unbalanced access to medical technology is in our current world, or the differences in average life expectancy between countries.

So, I was very strongly reminded of de Grey as The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere laid out its major thematic concerns and characters. I was also put in mind of many online arguments in the transhumanist milieu about whether it would be a good thing, in principle, to end death.

In particular, of course, comes to mind transhumanist Nick Bostrom's short story The Fable of the Dragon-Tyrant, in which death is likened to a huge dragon that demands to be fed trains full of humans every day. In the story, humanity's scientists secretly build a giant gun to kill the dragon. Naturally, despite all the doubters and naysayers who foolishly feel obliged to justify the existence of the dragon, the gun works. Bostrom's imagery is incredibly heavy-handed (particularly the trains à la Auschwitz), but just in case you didn't get it, he also spells out the moral explicit at the end: basically, every day not spent putting resources to abolishing death is adding up more and more bodies to the pile of people who don't get to be immortal.

So far, Flower seems to be shaping up to be a critical intervention into that milieu, with a much more grounded view of death and a much stronger model of society - admittedly not a high bar but it's going good so far!

At the time of writing this commentary, I have read the prologue and first two six-chapter arcs, namely Mankind's Shining Future (1-6) and Pilgrimage to the Deep (7-12).

the general shape of things

We are introduced - from the perspective of sardonic, introverted Su, who is going to be the protagonist of our time loop - to a group of brilliant young medical wizards, who have just been invited to visit the headquarters of a secret society whose mission is precisely to abolish death. Su's grandfather was some kind of controversial luminary who was expelled this organisation, and he also did something to her, which is giving her some kind of ulterior motive to find her way into this society.

We know pretty much from the outset that this is a time loop scenario: Su has been explicitly given the opportunity to replay the scenario in the hopes of find an alternative outcome, by some kind of presently mysterious parties. This first part is the 'control' loop, i.e. probably more or less how things went down 'originally'.

I believe Umineko is an explicit inspiration for this story, and the influence is pretty evident. But parallels with the Locked Tomb series, especially Gideon the Ninth, are also quite noticeable. @lukore spoke of it as the STEM to Locked Tomb's humanities, and I can already kinda see it, although we haven't got into the real meat of the scenario yet. This story began serialisation four years ago, making the two works roughly contemporary. The latest chapter was published in the last couple of weeks - no idea if I've arrived just in time for the ending!

Stylistically, it's generally pretty heavy on dialogue and long asides. The characters are a bunch of mega nerds who love to have big philosophical and political discussions, but their dynamics are well enough realised and their dynamics clear enough that it can double up as naturalistic characterisation. So far, the discussions have been interesting to read.

Below I'm going to make some notes and comments on various elements of the setting and story. In a followup post (because it got too long) I'm going to talk a lot about entropy. Perhaps you will find this interesting!

the world

The first few chapters are dedicated pretty hard to exposition. We find ourselves in a distant-future setting - one in which it seems reality has totally collapsed and then been rebuilt using magic, creating a somewhat oddball universe which lacks things like the element iron, and also electromagnetism. This seems like it would have pretty severe implications for just about everything!

However, the 'ironworkers' have, after producing a series of trial and error 'lower planes' that didn't quite get it right, landed on a fairly close approximation of how things used to be on the old world. Though by 'fairly close approximation' I mean like... it's a bowl-shaped world and the sun and stars are artificial lanterns. But still, there are humans, and they seem to work more or less like we're used to humans working, apart from the whole 'magic' thing.

So, an alt-physics setting. Praise Aealacreatrananda, I love that shit.

While electromagnetism might be out, the more abstract physical principles like thermodynamics still apply, and the humans of this universe have managed to find analogues to a number of things in our world. Instead of computers, they have 'logic engines' which run on magic. Horses seem to have made it in, so we get delightful blends of historical and futuristic concepts like a self-driving computer-controlled horse-drawn carriage taxi.

The biggest difference is of course that in this setting, magic - more on that in a bit - has solved most medical problems and humans routinely live to around 500. The setting is ostensibly a semi-post-scarcity one, although a form of money exists in 'luxury debt', which can be exchanged for things like taxi rides, café food and trips on the space elevator.

Politically, we are told that the world has enjoyed a few hundred years of general peace, broken in living memory by a revolution which put an end to a regime of magical secrecy. There are lots of countries, and an alliance overseeing them.

There's a few other oddities in this world. Something called a 'prosognostic event' can happen if you see someone who has the same face as you, and whatever this is, it's bad enough news that everyone is constantly reminded to veil their faces in public and there's some kind of infant 'distinction treatment' to mitigate the risk. Given that, in the regular world, nothing particularly bad would happen if you ran into a long-lost identical twin, it suggest there is probably something a little fucky about how humans work in this world!

There's evidently a fair bit of effort put into the worldbuilding of fictional countries and historical periods. The important elements seem to be roughly along the lines of:

our world is currently in what they call the 'old kingdoms' period, which is poorly remembered;

next up comes an 'imperial' period of high transhumanist shenanigans in which society was ruled by 'gerontocrats' who got exclusive access to the longevity treatment, but this all somehow led to a huge disaster which destroyed og earth;

the survivors built the Mimikos where humanity currently lives using magic and created some kind of huge iron spike that holds the universe together; there was subsequently a 'fundamentalist' period in which a strict cutoff point was put on human lifespans and a lot of the wackier magic was banned;

now we're onto a new era of openness following a small revolution, while the major political structures remain largely intact.

Writing a far-future setting is hard, because trying to deal with the weight of history without the story getting bogged down with worldbuilding details is a fiddly line to walk. The Dying Earth series of Jack Vance might be a relevant point of comparison. Vance leaves the historical details vague - there are endless old kingdoms and strange artefacts and micro-societies for Cugel and co. to stumble on. Far more important than the specifics of history is establishing the vibe of a world that's seen an unimaginable amount of events layered on top of each other and is honestly a bit tired.

Flower makes things a bit more concrete and generally manages to make this work decently well. I do appreciate the asides where Su talks about, for example, the different architectural styles that layer up to make a place, or the way a technique has been refined. It establishes both that Su is the kind of person to notice this sort of thing, and also helps the world feel lived-in.

the names

The story doesn't do a lot with language. The story is written in English, and the narration will occasionally make reference to how things are phrased (e.g. how divination predates the suffix -mancy). We can probably make the standard assumption that this is all translated from $future_language, with the notional translator making a suitable substitution of whatever linguistic forms exist in that language.

The characters are named in a variety of languages. Our main character's full name is Utsushikome of Fusai. We're told that this is "an old name from Kutuy, and means something like 'mysterious child'" - so Kutuyan is one of the languages spoken in this world. It's blatantly got the same phonotactics as Japanese, and indeed if I search up 'Utsushikome', I find an obscure historical figure called Utsushikome-no-Mikoto, wife of the Emperor Kōgen; she has no article on English Wikipedia, but she does have a brief one on Japanese wiki. Just as Su says about Kutuyan, 'Utsushikome' is written 欝色謎 in Japanese, but it relies on archaic readings of those characters and wouldn't read that way in modern Japanese. We could perhaps assume a good old translation convention is in effect where Kutuyan is replaced with Japanese.

A lot of characters have Greek names, as do various setting elements. One exception is Kamrusepa, or Kam, who is named for an ancient goddess of medicine worshipped by the Hittites and Luwians. I know basically fuck all about Hittites and Luwians but it's a cool little nod to mythology, and it won't be the only one!

I'll run down a list of characters and my comments about them in a bit. But many are named after gods or other mythological figures.

the magic

Most of the divergences come from magic existing. Certain humans are 'arcanists', who are able to use the 'Power', which is a magic system with a highly computational flavour. Thanks to Su's expositional asides, we know that an incantation is something like a short program written in cuneiform with the ability to gather information, perform maths, and manipulate particles. An example we are given is a spell called "entropy-denying", which is the following string of cuneiform:

"…(𒌍𒌷𒀭)(𒌍𒁁𒀭)𒅥𒌈𒆜𒈣𒂠, 𒋢𒀀𒅆𒌫𒃶,𒈬𒊹."

We're told that spells always start with phrases ending in 𒀭, and end in 𒊹. Beyond that, I'm not sure how far the author has actually worked out the syntax of this magic system - probably not in too much detail! Seems like the kind of thing it's better to leave vague, but also she seems like kind of nerd who would (positive). It's conceptually a reasonable magic system for a world where more or less realistic physics applies.

The use of unusual scripts for a magic system isn't that unusual - the old European occultists who wrote the [Lesser] Key of Solomon loved to write on their magic circles in Hebrew, and in modern times we could mention Yoko Taro's signature use of the Celestial Alphabet for example - but the specific use of cuneiform here seems like it might be a little more significant, because a little later in the story the characters encounter a mural depicting The Epic of Gilgamesh, which of course was recorded on cuneiform tablets. Remains to be seen exactly what these allusions will mean!

The magic system is divided into various disciplines defined by the different ways they approach doing magic, with the disciplines breaking down broadly along the same lines as the modern scientific disciplines. For example, our protagonist is a thanatomancer ("necromancer" having become unfashionable), which is the discipline dealing with death; she's specifically an entropic thanatomancer, distinguished by their framework viewing death as the cessation of processes.

Magic relies on an energy that they refer to as 'eris' (unknown relation to the Greek goddess of strife and discord). We are told that eris must be carefully apportioned across the elements of a spell or shit blows up, that it can be stored, and it accumulates gradually enough that you don't want to be wasteful with it, but so far given little information about where it comes from.

Magic in this story generally seems to act as a kind of 'sufficiently advanced technology'. It's very rules-based, and used for a lot of mundane ends like operating computers or transport. Advancement in magic is something like a combination of basic research and software development. But the thing that makes it a magic system and not merely alt-physics is that it's at least a little bit personal: it must be invoked by an individual, and only certain people can operate the magic. We're told a little about how wizards are privileged in some societies, indoctrinated in social utility in others, and expected to be inconspicuous in the present setting. It's not clear yet if you need some kind of special innate capacity to do the magic, or if it's just a matter of skill issue.

With one exception, our main characters are a gaggle of wizards, and exceptionally skilled students at that. They're at an elite institution, carrying high expectations, even if they are themselves fairly dismissive of the pomp and ceremony. They have grandiose plans: Kamrusepa in particular is the main voice of the 'death should be abolished' current.

the cast

We're entering a cloistered environment with high political stakes hanging off of it. Even if I hadn't already heard it described as a murder mystery, it would feel like someone will probably be murdered at some point, so lets round up our future suspects.

Su (Utsushikome) is our protagonist and first-person POV. She's telling this story in the first past tense, with a style calling to mind verbal narration; she'll occasionally allude to future events so we know for sure narrator!Su knows more than present!Su. She's got a sardonic streak and she likes long depressing antijokes, especially if the punchline is suicide. She will happily tell us she's a liar - so maybe her narration isn't entirely reliable, huh.

Su is more than a little judgemental; she doesn't particularly like a lot of her classmates, or people in general, and generally the first thing she'll tell you about a character is how well she gets on with them. She introduces the theme of 'wow death sucks' in the first paragraph, but she is, at least at this point, pessimistic that anyone will manage to do anything about it for good.

Her magical specialisation is entropic thanatomancy, roughly making processes go again after they working coherently.

Her name is a reference to an obscure Japanese empress, as discussed above.

Ran is Su's bestie from the same home country. She is generally pretty on the level. She likes romance novels and she is pretty sharp at analysing them. She will cheerfully team up with Su to do a bit or bait someone else when an argument gets going.

Her magical specialisation is Divination, which is sort of a more fundamental layer of magic, about gathering information by any means. In medicine it's super advanced diagnostics.

Her name is too short to pin down to a specific allusion. Could be one of a couple of disciple of Confucius such as Ran Geng, or a Norse goddess of the sea.

Kam (Kamrusepa) is the de facto class prez and spotlight lover. She's hardcore ideological, the story's main voice of the de Grey/Bostrom death-abolishing concept so far - I think she straight up calls someone a 'deathist' at some point. She loves to tell everyone what she thinks about everything, and getting the last word.

Her magical specialisation is Chronomancy, so time magic. It's described as secretive and byzantine, but also it can do stuff like (locally?) rewind time for about five minutes. No doubt it has something to do with the time loop.

As mentioned above, she's named after a fairly obscure ancient deity of healing and magic.

Theo (Theodoros) is a fairly minor character. He's scatterbrained and easily flustered, he has a similar background to our protagonist, and he's not great with people. His name is shared with a number of ancient Greek figures, so it's hard to narrow it down to one allusion. I don't think his magic school has been mentioned.

Ptolema is a cheery outgoing one, someone who Su dismisses as an airhead. And she is at least easy to bait into saying something ill-considered. Her specialisation is applying magic to surgery. As a character, she tends to act as a bit of a foil to the others. Bit of a valley girl thing going on.

'Ptolema' is presumably a feminised version of the renowned Greek philosopher Ptolemy.

Seth is the jock to Ptolema's prep, and our goth protag Su doesn't particularly like him either. ...lol maybe that's too flippant, I may be misapplying these US high school stereotypes. To be a little more precise then, he's pretty casual in demeanour, flirty, likes to play the clown. He specialises in Assistive Biomancy, which revolves around accelerating natural healing processes.

Seth is named for either the Egyptian god (domain: deserts, violence and foreigners) or an Abrahamic figure, the third son of Adam and Eve granted by God after the whole Caim killing Abel thing.

Ophelia is someone Su describes as 'traditionally feminine' - soft-spoken, demure etc. (Gender in this world appears to be constructed along broadly similar lines to ours). Indeed we get a fairly extended description of her appearance. Her specialisation is Alienist Biomancy, which means introducing foreign elements to healing (not entirely sure how that differs from the Golemancy mentioned later).

Ophelia is of course a major character in Shakespeare's Hamlet, best known for going mad and dying in a river.

Fang is the only nonbinary member of the class, noted as the most academically successful. They're not on the expedition, but the characters discuss them a little in their absence, so maybe they'll show up later. It seems like they have a bit of a rebellious streak. Their magical specialisation is not mentioned.

Fang is a regular ol' English word, but I gave it a search all the same and found there's an ancient Chinese alchemist of that name. She is the oldest recorded woman to do an alchemy in China, said to know how to turn mercury into silver.

Lilith is the teenaged prodigy in computers logic engines, and Mehit is her mother who accompanies her on the trip. They've got a big Maria and Rosa (of Umineko) dynamic going on, with Mehit constantly scolding Lilith and trying to get her to obey social norms, though in contrast to Maria, Lilith is a lot more standoffish and condescending to the rest of the gang. Lilith specialises in 'Golemancy', which means basically medical robotics - prosthetic limbs and such. She spends most of her time fiddling with her phone logic engine, and will generally tell anyone who talks to her that they're an idiot. Sort of a zoomer stereotype.

Lilith is named for the Abrahamic figure, the disobedient first wife of Adam who was banished and, according to some Jewish traditions, subsequently became a demon who attacks women at night. There may be some connection between Lilith and the lioness-headed Mesopotamian chimeric monster Lamashtu, which I mention because Mehit is an Egyptian and Nubian lion goddess.

'Golemancy' is probably playing on the popular fantasy idea of a 'golem' as a kind of magic robot, but given the Jewish allusion in Lilith's name here, I do wonder a little bit if it's going to touch on the Jewish stories of the Golem which inspired it - a protective figure with a specific religious dimension.

There are some other characters but they're not part of the main party on their way to the function, so I won't say much about them just yet. Also it's entirely possible I went and forgot an entire classmate or something, big whoops if so.

the events

In true Umineko tradition, the beginning of the story narrates in great detail how the protagonists make their way to the place where the plot is going to happen.

To be fair, there's a lot of groundwork to be laid here, and the characters' discussions do a lot to lay out the concerns of the story and sketch out the setting, not to mention establish the major character relations. A murder mystery takes a certain amount of setup after all! There's plenty of sci-fi colour to be had in the 'aetherbridge', which is a kind of space elevator that lifts you up to a high altitude teleporter network. (It's technically not teleportation but 'transposition', since teleportation magic also exists in the story, with different restrictions! But close enough for government work.)

They go to a huge space citadel, which is kind of a transport hub; some cloak and dagger shit happens to hide the route they must take to the mysterious secret organisation. They find a strange room with a missing floor and a mural of the Epic of Gilgamesh, albeit modified to render it cyclic. What does it meeaaaan?

The idea of a secret society of rationalists is one that dates back to the dawn of ratfic, in HPMOR. It was kinda dumb then, but it works a lot better here, where we're approaching the wizard circle from outside. The phrase 'Great Work' has already been dropped. I love that kind of alchemical shit so I'm well into finding out what these wizards are plotting.

the dying

A lot of the discussions revolve around the mechanics of death. Essentially the big problem for living forever is information decay. Simple cancers can be thwarted fairly easily with the magic techniques available, but more subtle genetic slippages start to emerge after the first few hundred years; later, after roughly the 500 year mark, a form of dementia becomes inevitable. It's this dementia in particular that the characters set their sights on curing.

One thing that is interesting to me is that, contra a lot of fantasy that deals with necromancy (notably the Locked Tomb series), there appears to be no notion of a soul in this world whatsoever. The body is all that there is. Indeed, despite all the occult allusions in the character names, there is very little in the way of religion for that matter. Even the 'fundamentalism' is about an idea of human biological continuity that shouldn't be messed with too much.

Su distinguishes three schools of thought on death, namely 'traditional', 'transformative' and 'entropic'. The 'traditional' form attempts to restore limited function - classic skeleton shit. 'Transformative' sees death as a process and uses dead tissues together with living in healing. Su's 'entropic' school broadens this 'process' view to consider death as any kind of loss of order - a flame going out as much as an organism dying. At the outset of the story, Su has discovered a 'negentropic' means to restore life to an organism, which she considers promising, even if for now it only works for fifteen minutes.

This is an interesting perspective, but the devil is in the details. Because processes such as life or flames, necessarily, result in a continuous increase in the thermodynamic entropy of the universe. And yet this idea of death-as-loss-of-order does make a kind of sense, at a certain level of abstraction.

Elaborating on this got rather too long for this post, and I think it can stand alone, so I'm going to extract it to a followup post.

the comments

As is probably evident by the length of this post, I am very intrigued by The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere. The setting is compelling, and it seems like it's got the willingness to bite at the chewy questions it raises instead of acting like it has all the answers, which is I think one of the most crucial elements for this kind of scifi. I like how unabashed it is at having its characters straight-up debate shit.

Of course, this all depends where they go with it. There's so many ways it could be headed at this point. I hear where it's going is 'dark yuri' and 'Umineko-inspired murder mystery', so that should be really juicy fun, but I do end up wondering what space that will leave to address the core theme it's laid out in these first few chapters.

Overall, if this and Worth the Candle are what modern ratfic is like, the genre is honestly in pretty good shape! Of course, I am reading very selectively. But this is scratching the itch of 'the thing I want out of science fiction', so I'm excited to see where the next 133 chapters will take me.

Though all that said, I ended up writing this post all day instead of reading any other chapters or working, so I may need to rein it in a bit.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toxic Yuri Bracket Round 8

#poll#tournament poll#toxic yuri#yuri#killing eve#eve polastri#villanelle#villaneve#the flower that bloomed nowhere#ransu#tftbn

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

idk if this was obvious to others but i only realized recently on my flower reread that su probably experienced some sort of sexual coercion from her grandfather. the most operative quote imo is this one from chapter 128:

So, how did I cope with this cognitive dissonance? Well, I decided to lose myself in her grandfather's fantasy, too. I let myself believe that this really was all some kind of fairy tale. That I was this girl he loved reborn. I listened enthusiastically to his stories on the good days, and tried my best to care for him on the bad. I let him cry on my shoulder. When he bemoaned about the order or that his 'Great Work' had all come to nothing, I soothed him and told him that he'd done his best, despite having no idea what the fuck he was talking about. Then some unpleasant things happened. After that, I didn't want to think about him at all. I wished he would just hurry up and die so I could stop and move on with my life. Then, about a month later, he did.

(all emphasis in quotes is mine). . . this could be anything by itself however this in combination with a variety of details from other chapters is pretty damning. starting with this one from chapter 109:

And as for the person he'd wanted to replace Shiko with... Well, they certainly weren't his daughter, that was certain.

i have compiled the other quotes leading to this conclusion under the cut, followed by some thematic discussion.

a lot of the evidence is in the chapters where samium and the grandfather discuss their original plot to have wen be reborn into utsu. from 119:

"Look at what we're doing, Sam," Shiko's grandfather said, laughing with pitiful resignation as he rubbed his eyes. "We're plotting to abduct an innocent teenage girl, a girl who's supposed to be my granddaughter--"

Samium then argues that she actually isn't his granddaughter due to lack of genetic relation because of the nature of reproduction in the remaining world. they get quite technical about whether or not utsu is his granddaughter. it could just be because bodysnatching people is generally a bad thing to do, but i'm postulating its also because it is particularly twisted to bodysnatch your granddaughter to replace her with a woman you have a romantic connection to.

"You do understand, Sam," Shiko's grandfather said. "You're just pretending that you don't, because I've all but trained you to do so at this point." His brow wrinkled. "I... fear I've let myself be carried away by my own depraved desires, these last few years. And I've swept you along with me."

Also from 119, noting specifically the "depraved" desires. In chapter 120 Su specifically describes the situation as "romantic"

From what they'd said, it sounded like there was some technique they'd planned to use to have her memory be suppressed - since she'd be, well, a literal baby - but come back to her as she'd grown up. It sounded... I didn't know the right word for it. Some kind of cross between romantic and fucking bizarre.

In the same chapter, he also brings up the idea of a safety concern if he forgets about what happened with the bodyswap as his dementia progresses and doesn't "keep his distance":

"It would have ended in a wash anyway, or an outright disaster," Shiko's grandfather continued, after Samium didn't say anything for a while. "My condition is getting worse by the month at this point-- On the bad days, I sometimes even forget where I live. Slim chance I'd have the sense to keep my distance, if I even remembered who she was at all." "Would that have been so terrible?" Samium said, now seeming resigned. "It would have," Shiko's grandfather spoke confidently. "Not just for her own safety, but... Well, the last I'd ever want would be for her to see me as I am now. Distorted..." He hesitated, cutting himself off. "It's for the best."

Finally, in chapter 125 there's this description of what Samium tells Su about the girl she's supposed to be impersonating, followed by this note:

What he didn't talk about, rather conspicuously, was her relationship to whoever her grandfather had been in the old world. He said it was irrelevant, because he'd never wanted her - as Utsushikome - to realize who he was anyway-- That it would only bring him shame and embarrassment. He said that I ought to just follow his lead, and let him wanting to believe do the rest. He also told me very little about the old world itself, again stating that it didn't matter. ...which was a little peculiar, in retrospect.

Implying/foreshadowing that there was something notable about the relationship between Wen and the grandfather that Su didn't know at this point.

Putting together the pieces, it's pretty clear that the grandfather was trying to bring back his dead lover. Occam's razor combining that information, the grandfather's escalating dementia possibly leading him to forget that it is not his actual lover in front of him, the "unpleasant things" that happened that caused Su to no longer want to think about him and even want him to die, and Su's behavior and discomfort about the topic of the grandfather after the fact to the point of always mentally censoring his name, a situation where he came on to her seems to be the obvious explanation.

I described this as "sexual coercion" earlier but interestingly I don't think it would be the grandfather himself at the time of making an advance who would refuse to stop. . . it's more that in Su's situation given her previous background and having undergone an extremely illegal and secret process to "become" Shiko it is unlikely that she would feel empowered to say no to him. Especially if she is taken by surprise due to not understanding the situation.

Not to say that the grandfather is not culpable--he is culpable for having made the decision to try to grow someone who was supposed to be his granddaughter into his lover in the first place and continuing on with the attempt for many years even after she was her own person with her own personality who would have to be killed to become the person he wanted. And of course Samium bears even more culpability for actually going through with killing two teen girls in order to please the grandfather and then not explaining anything to Su leaving her open to sexual exploitation. I think this ties clearly into Flower's themes of class exploitation to have the wealth and power of the grandfather enable this interpersonal violence.

Relatedly, I find it pretty thematically interesting to consider the Order's response to this. . . they don't know the details but obviously they have some understanding of the grandfather's obsession with Wen and that he had some sort of plan concerning Su especially because they were involved with some of the research and Wen's image is in the grandfather's box. They know enough to be apologetic towards Su and expect her to have some conflicting feelings about her grandfather. . . but ultimately of course they did nothing but enable him. His ultimate expulsion was totally unrelated.

I think this is very fitting for an organization that is exemplifies the decadence and violence of an elite group within a society with unparalleled wealth disparity. . . like of course the Order harbors and protects abusers. The obvious parallels to Su's subsequent relationship with Neferauten also paint that in an even more dire light.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

utsushikome on the shores of itan

#happy birthday my darling princess angel precious babygirl#the flower that bloomed nowhere#tftbn#utsushikome of fusai#the telltale arts#flower

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

join us!!! we have:

TOXIC CODEPENDENT YURI

NECROMANCY

CLASSICAL STUDIES

THE PERMEABILITY OF THE SOUL

WIZARD MURDER MYSTERIES

and THE HORRORS OF LOVE

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm reading The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere and I don't know if there's a name for this style of prose, but I love it. You have this winding explanation about the sun's creation, why the sun was important to humans, how in this new world humans recreated the sun in both form and function, and how this lamplight is sometimes rejected by a person's body. Each paragraph's content is distinct, but its purpose seems fully expository until you reach the succinct end--our main character has rationalized that they prefer rainy weather because of this lamp-rejection phenomena and, returning to the present-story, is walking pleasantly in it. Su even humorously muses that she may simply prefer the rain because she's gloomy, rendering the entire explanation irrelevant.

It reminds me of those meandering stories you only realize are jokes once the teller reaches the snappy punchline, but with more crafty worldbuilding.

Text of the passage is under the readmore

Once, before the final days of the Iron Epoch and the collapse that followed, the old world had orbited a local star referred to as the 'Sun'. A massive ball of plasma fueled by the hydrogen fusion process spat out of a molecular cloud at some point in the foggy distant past of the universe, it had been a major part of the cosmological miracle that had given birth to life, and, later, the cosmological disaster called the human race.

Like the majority of land-based life, mankind had evolved to depend upon the sun in a variety of ways, both as a mechanism to regulate behavior - sleep patterns - and as an agent to actively assist in biological processes, most notably the conversion of cholesterol into secosteroids via 'cooking' them on the skin with ultraviolet radiation. As a result, relishing in sunlight became, to an extent, a desirable trait in the psyche, becoming deeply embedded in the reptilian parts of the mind.

The Great Lamp, created by the last of the Ironworkers during the construction of the Mimikos - the highest plane of the Remaining World, and the primary home of humanity - had thusly been built to emulate the sun in not only function, but aesthetics and perceived behavior. It crossed the firmament over the course of the day, traveling from the east into the west. The pathway it took even changed with the seasons, as it had in the old world based on the axial tilt of the planet.

But the human brain is a observant and fussy thing, and some brains are even more observant and fussy than others. Inevitably, in some individuals, a small part of them remained aware that it wasn't quite right, producing an uncomfortable dissonance that had at this point become a widely-recognized phenomenon. I understood there were even groups to help treat it; you'd go out on nice trips to parks and to the seaside in broad daylight during summertime, to help you form happy memories associated with the lamplight. (This was a concept that seemed nightmarishly saccharine and dystopian to me, but that's neither here nor there.)

Because I'm the type of person who likes to rationalize and pathologize everything, I'd always assumed this was the reason I preferred night time and rainy days to clear daylight, although it might just have been because I'm naturally a gloomy person. Either way, as Ran and I walked down the high street outside the university, I found myself feeling surprisingly calm and light-hearted.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok one more flower that bloomed nowhere propaganda piece to share. i don’t really like making these comparisons in a serious capacity because they’re reductive and are usually employed in a way that reduces characters to tropes but hear me out for just one second. su is like kim dokja if he was a woman. and way worse.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death and Identity in Post-postmodern Mystery

This essay contains spoilers for the entirety of Umineko When They Cry and spoilers for up to Chapter 140 of The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere.

Near the end of the first half of Umineko When They Cry, a bizarre curveball is tossed into the logic duel between Battler and Beatrice. Beatrice claims that Battler is somehow not actually Battler, but rather an imposter, a body double brought to the island as part of a plot to seize the inheritance. Thus, Battler is unqualified to be her opponent, meaning he must be expelled from the metafictional realm where the game takes place, and the game itself must be cancelled.

Battler, stumped by her logic, cannot form a rebuttal. He disappears, his very existence denied. "Without the one pillar that established his soul," the story reads, "he had fallen into the very depths of darkness, and had been drifting about all this time."

In The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere, a parallel moment occurs at the climax of the story's first half. The protagonist, Utsushikome of Fusai, confronts the person she believes to be the murderer, someone she knew when she was young. Cornered, he attempts to appeal to their childhood friendship, indicating he had even been in love with her. Utsushikome of Fusai cuts him off coldly, saying:

"I'm not Utsushikome of Fusai."

She then bludgeons him to death with a blunt instrument, committing a murder for which the reader immediately and unambiguously knows the culprit.

Identity is the fundamental question of even the most basic mystery novel. What is the identity of the culprit? Which character, seemingly a functional member of society, is actually a murderous villain?

As the genre has developed in complexity, this question has only become more prominent. Red herrings designed to throw off genre-savvy readers necessitate many non-culprits to also lead double lives or conceal key components of their identities. Inverted mysteries, where the culprit is revealed to the reader right away, emphasize the duality of the culprit's public persona and their murderous secret: Columbo's villains are exclusively elite, wealthy, and cultured, and Light Yagami is the seeming portrait of a model Japanese youth. Even House MD, a mystery story where "diseases are the suspects," predicates its drama on the fact that the diseased victim is concealing a double identity; in House's words, "Everyone lies."

Meanwhile, the mystery genre blurs the line between art and game. A proper mystery, as genre purists will tell you, must be solvable, must be fair, must follow certain "rules." If the culprit turns out to be a character who had not appeared in the story prior to their reveal, then the parameters of the game were broken, the reader had no chance. Ditto for the implementation of fanciful poisons or contraptions, secret twins, hidden passages, and so forth. These rules are in service of preserving the phenomenological experience of reading a mystery; like a game, the value of the work is expressed through the reader's attempts to interpret it, rather than its existence as a static artistic monument.

Yet, the genre has long been entangled with literary art. Mystery's foundation lies with authors like Edgar Allan Poe and Wilkie Collins, placing it as an outgrowth of the romantic and realist literary epochs. But between 1880 and 1930—the peak of literature as mass market entertainment, before film slowly usurped it—from when Sherlock Holmes popularized the genre until the so-called Golden Age of Detective Fiction, mystery became its "own thing," and in being its "own thing" suddenly resisted the artistic spirit of its time, whatever that time might be. The Golden Age coincides temporally with the height of modernist fiction, and yet none of the stream of consciousness or abstraction that defines the latter seeps into the former whatsoever. In the post-WWII postmodern era, when literature increasingly rejected the concept of objective truth altogether, detective fiction (both in literature and in new, televised forms) continued to doggedly assert the objective truth of the culprit's identity, the objective solvability of the crime.

A lot of this discrepancy has to do with the general schism between "art" and "entertainment" that arose in literature between the late 1800s and early 1900s. As the modernists ventured in more experimental directions, a newly literate and growing middle class continued to clamor for works that were more relatable to their pragmatic, dollars-and-cents sensibilities. (I often talk about "modernism" and "postmodernism" as these all-encompassing artistic zeitgeists, but the truth is that literary realism has never fallen out of vogue with mass audiences, and even in the 1920s a realist social satirist like Sinclair Lewis—not to mention twenty names you've never heard of writing at a similar bent—sold more than Hemingway and Faulkner combined.)

By entrenching itself within the "entertainment" sphere, and by continually defining itself against itself (the process by which "genre" is created), mystery fiction was able to develop independently of the overall artistic milieu and maintain a faith in objective reality even as that became an increasingly untenable position elsewhere. And it's what makes post-postmodern mystery fiction like Umineko and The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere so fascinating to me.

Umineko didn't emerge in a vacuum. It extends from Japan's dedicated mystery subculture, and I've heard that it shares many similarities with The Decagon House Murders, a 1987 novel by Yukito Ayatsuji. Japan has its own unique relationship with postmodernism as a literary movement, with it being more of a clearly-defined artistic fad that reached prominence in the 1980s specifically, compared to the West where postmodernism seems to be the nightmare of a post-WWII world from which we cannot awaken. I wish I had more familiarity with the Japanese mystery subculture to more authoritatively speak on this subject, but I do know that it, like the West, still believes strongly in the solvability of its mysteries. I described Japan as having a "postmodern" mystery scene, but that's not what Japan calls it. In Japan, the term for a solvable, "fair play" mystery is honkaku, meaning "orthodox"—or, roughly equivalent, "classical." And beginning with The Decagon House Murders, Japanese mystery entered a new era, shin-honkaku—neoclassical.

These terms are a perfect fit. In the West, the classical is associated with the Renaissance, and indicates a focus on mathematical precision in service of the objective truth associated with God. (The golden ratio, after all, is called divina proportione in Italian—divine proportion.) The precise, solvable logic of a classical murder mystery fits within this framework, and the neoclassical mystery retains its core beliefs, much as how Napoleon Bonaparte wielded neoclassicism to lend divine legitimacy to his rule. Despite the increased complexity and metatextuality of shin-honkaku mysteries, there remains that belief in objective truth.

Umineko does not believe in objective truth.

Umineko, as a mystery, is fucking bullshit. Solving it relies on so many unspoken metafictional conceits, and even if you do "solve" it, it turns out that the culprit of the first half of the story isn't even the """real""" culprit, because the first half of the story was actually just in-universe murdersona fanfic and the actual """""truth""""" of what happened on the island is completely irrelevant to most of the mysteries with which the reader is presented.

And that's under the assumption that Umineko actually tells you who the """""""real""""""" culprit is, because it doesn't, unless you read the manga, where it was thrown in as a bone to an absolutely incensed fanbase. Umineko was not popular with the Japanese mystery crowd, which makes sense, because they get pretty directly and brutally lampooned. This is a story where a detective quoting Hercule Poirot gets introduced halfway into the story and is an unequivocal villain (she calls herself an "intellectual rapist"), with the heroes fighting to conceal the truth from her.

No, Umineko does not believe in objective truth. It might believe it exists, in some abstract way, but it does not believe it matters, compared to the magic of subjective reality. About 90 percent of Umineko (honestly a lowball estimate) depicts stuff that didn't really happen. Sometimes it depicts stuff that didn't really happen within the subjective reality of a fanfic that itself didn't really happen. Even most flashbacks set before the mystery or flash forwards set after are mired in unreality.

No, what Umineko believes in is emotional truth, subjective truth. The story's key phrase is "Without love it cannot be seen," referring to how biases (love) influence one's understanding of reality. The "Red Truth," objectively correct statements, are depicted as painful and punishing, or spiderwebs that ensnare helpless victims. It is in the space between what is known objectively where magic is allowed to exist, where interpretation can supersede fact, and where true emotional catharsis can be reached.

As such, it is the antithesis to the mystery genre.

It's also the antithesis of postmodernism. Not rejecting it, in an impossible attempt to return to some pre-modern understanding of the world; no, Umineko agrees with postmodern thought on the subjectivity of our reality. Where it diverges is in the interpretation of that subjectivity, seeing in it not the cynical nihilism postmodernism quickly (perhaps from the onset) devolved into, but a new method of reaching emotional and intellectual fulfillment.

This, to me, is what the post-postmodern artistic zeitgeist has increasingly turned toward. Works that recognize the information-dense, ungraspable reality of the post-internet age, but seek and ultimately find emotional catharsis within it. Everything Everywhere All at Once, Spider-verse and unlimited lesser multiverse stories, Homestuck, even the origin point of the literary mode Infinite Jest all operate within this theme.

Where Umineko seeks its catharsis is in identity. While the central "game" of the mystery, sometimes literalized as a chess match between Battler and Beatrice, initially appears to be Battler's attempt to discern the true culprit in classical mystery fashion, from Beatrice's perspective the game is an attempt to assert and confirm the existence of her identity altogether.

In "reality," Beatrice the Golden Witch "does not exist." There is no magical being haunting the island. Beatrice is an identity invented by another character in an attempt to generate meaning for their life. And that meaning is, fundamentally, important, perhaps more important than the objective facts that deny her existence. Which is why, as the story continues, Battler switches to Beatrice's side and defends her existence from a slate of cackling ghouls dredged out of the annals of classical mystery, who sling the "rules" of classical mystery about like weapons to maim and kill. Objectivity is the enemy, the Red Truth is a prison, but it cannot cover everything and in the mercy of subjective reality, a different sort of "truth" can be allowed to live. As the story goes on, it becomes increasingly clear that this "truth" is everything. Umineko never explicitly reveals the true killer on Rokkenjima, though mostly only through technicality. That's fine. Even by technicality, subjectivity can be allowed to live. Beatrice's identity remains.

Return to that moment I described at the start of this essay, where Beatrice briefly denies Battler's identity. In the overall narrative of Umineko, it winds up being an almost entirely inconsequential scene. Shortly after Battler disappears, his sister Ange asserts that even if Battler was not born to Asumu, he is still Kinzo's grandson, meaning he is a true heir to the Ushiromiya family and thus qualified to be Beatrice's opponent. Battler returns and the status quo is swiftly reestablished.

What is the purpose of this scene, then? In character, it makes sense as a play for Beatrice to make. Her own identity has been constantly under assault from Battler, most recently—and most painfully, for her—when Battler forgot an important promise he once made to her. She is giving him his own medicine as revenge. But it's a very dramatic and extreme turn for something so petty. The scene does establish that Battler was not actually born to the woman he believed to be his mother (Asumu), but what does this mean for the story itself?

Beatrice's claim stems from a convoluted baby swapping plot that is revealed much later in Umineko. It turns out that Rudolf had a child with both Asumu and his mistress Kyrie at the same time, and Asumu's child, the "real" Battler, died immediately, so Kyrie's child was renamed Battler and substituted for the real thing. Both children were Rudolf's son, and thus Kinzo's grandson, and all of this really has nothing to do with anything else going on in Umineko's mystery, and is kind of pointless. (It does suggest Battler as a red herring identity for the mysterious baby Kinzo tries to foist onto Natsuhi in Umineko's fifth episode, but as far as red herrings go, it's a lot of legwork for not much deception.)

I've always been fascinated, though, by what it would mean if Beatrice's claim were true. Not just that Battler wasn't Asumu's son, but that he was not related to the Ushiromiya family at all. There's some fairly compelling evidence in its favor. It's stated early on that Battler, at age 12, became angry when his father married Kyrie shortly after Asumu's death, and estranged himself from the family for six years. His appearance at the family conference where most of Umineko takes place is the first time anyone in the family has seen him since, and almost everyone is surprised by the physical transformation Battler has undergone, particularly remarking on how incredibly tall he is. Near the end of Umineko, when it is suggested that Rudolf and Kyrie are the mystery's "true" culprits, the idea that they brought in some yakuza thug to pose as Battler and help them murder everyone becomes compelling.

But that's just the practical aspect of the mystery. What about the story itself? What would it mean for the ultimate moment of emotional catharsis at the end of the narrative, when Ange—dying of cancer—finally reunites with her long lost brother, only to discover he isn't actually her brother at all?

Well, that's actually what happens at the end of Umineko. Not because Battler is a yakuza thug, though. It's because of yet another oddly-inserted plot element where Battler receives brain damage escaping the island and develops a dissociative identity disorder that causes him to view himself as Tohya Hachijo, an amnesiac author.

Though somewhat farfetched, this last-second development makes sense within Umineko's thematic framework, where identity—and the capacity for people to inhabit multiple identities at once, either literally or through the subjective interpretations of the people around them—is one of the key drivers of the story's emotional core. For Ange, her brother is lost, and yet meeting Tohya is a moment of intense catharsis, because she is willing to believe in the redemptive magic of love and "see" a subjective truth more powerful than objective reality. After all, this meeting occurs in the "Treat" ending, and is placed in contrast to the "Trick" ending, where Ange instead embraces objective rationalism and deals with uncertainty by gunning down anyone who might possibly be a threat to her. (Which turns out to be every character in her immediate vicinity.)

I wonder how that Treat ending catharsis would read, though, if instead of the author Tohya Hachijo, who deals with his identity disorder by writing fictional accounts of the Rokkenjima massacre that, while not the literal truth, reach for a subjective or emotional truth, the version of her brother Ange met was Battler the yakuza thug, who was never her brother but a cheap imposter. It would probably undermine Umineko's entire message. It would at the very least make the Treat ending seem like a nasty trick in its own right. Or would Ange still be able to "see" an emotional truth even in this? Where does the line between subjective reality and pathetic delusion lie? What, exactly, would be the identity of the brain-damaged man she reunites with? What is the identity of the story's protagonist?

That's where The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere comes in. When its central mystery starts, a metafictional interlude occurs in which rules for solving the murder(s) are established. The first rule reads:

1. THE PERSPECTIVE OF THE PROTAGONIST IS ALWAYS TRUTHFUL

This rule, like many of the subsequent rules, is highly questionable. The story has already thrown into doubt who exactly the "protagonist" is. That seems like an odd thing to say, because the very first chapter, numbered 000, appears to make it explicitly clear:

"Understand this: Your role in the scenario has been elevated from that of bystander to that of the heroine, and your victory condition is thus," she continued. "You must ascertain the identity of your opponent, the cause of the bloodshed to follow, and prevent it before it comes to pass. In order to accomplish this goal, you must pay close heed to all which transpires, and use deduction, alongside your skills and past experience of the events to follow. Do you understand your role?" "Yes," I said, muted.

The issue is that whoever the perspective character is in 000, they are not the same person as the perspective character for the rest of the story. It eventually becomes clear that they share the same body, that they are both called Utsushikome of Fusai. Nonetheless, they are distinct identities. They have different memories, different motives, and different personalities. Much later, they even hold a conversation with one another in the same metafictional realm where the mystery's rules were outlined, a metafictional realm that turns out to not be metafictional at all.

Of course, neither of these Utsushikome of Fusais are actually Utsushikome of Fusai. They are gestalt personalities that combine the memories and personality of an original Utsushikome of Fusai with the memories and personality of an entirely different girl named Kuroka, and then after the two Utsushikome of Fusais diverged from one another for reasons that are, as of writing, not fully clear but potentially due to the accumulation of memory over a centuries-long time loop. This labyrinth of identity defines the story as much as its core mystery. As said mystery hurtles toward its climax, scenes in the present are intercut with flashbacks detailing how the current identity of Utsushikome of Fusai came to be. In the present mystery, there is no ultimate reveal of the culprit (one is proposed, but in fairly faulty fashion). In the past, though, the reveal of the truth of Utsushikome's identity is laid bare, brutally and explicitly, to the point that it consumes the main narrative, and culminates in the scene I described at the beginning of this essay, where the gestalt entity inhabiting Utsushikome's body discards her identity as Utsushikome and performs a brutal on-screen murder.

In doing so, the traditional climax of the mystery novel—the unmasking of the culprit—is reframed. It is the protagonist, not the culprit, who is "unmasked." Flower is, ostensibly, a time loop murder mystery (though only one loop is shown), and shortly after committing this murder, Utsushikome meets another character, who tells her that in 90 percent of loops, Utsushikome herself is the murderer. It's a claim that seems unbelievable, despite what just happened, based on the reader's knowledge of Utsushikome as a bumbling and indecisive girl who needed the most extreme circumstances to rouse herself to violence (an "anxious waif," as the author, Lurina, described her to me). It's a claim even Utsushikome meets with doubt. At the same time, how much does the reader really know about this character? How much does she know about herself? Throughout the story, her name is split into various nicknames: Utsu, Su, Shiko, each tied to a different part of her existence. The fragmentation of her name symbolizes the fragmentation of her psyche, and the version of her the reader follows—the ostensible "protagonist"—is Su, the smallest and most fragmentary scrap of her, the one most divorced from knowledge and understanding.

If Umineko exhibited faith in the magic of subjective interpretation, Flower provides a cynical counterpoint. Forget comprehending other people, or the confusion of your increasingly complex world. What if you cannot even comprehend yourself? What if, rather than the redemptive turn of Umineko's Treat ending, one looked inward and saw only greater incomprehensibility? In Beatrice, Umineko has its own character whose psyche fragmented into various constituent personalities, each with their own name and appearance. Yet Umineko posits a beauty in these personalities, and its protagonists fight for their right to exist in the face of crushing objective reality. For Utsushikome, her fragmented selves are base, ominous, potentially murderers, or indeed actually murderers—as even Su considers herself the murderer of the original Utsushikome. Her primary goal, more important to her than solving the mystery, is finding a way to undo the gestalt fusion that underlies her personality and restoring the original Utsushikome. Beatrice fights to justify her existence; Su fights to destroy it.

Postmodernism's focus on the subjectivity of individual experience quickly turned it toward cynicism, even nihilism, and the all-pervading "irony" that David Foster Wallace made his personal bugbear. One can only know their own experience of the world, not anyone else's, and the outside world is becoming increasingly complex, increasingly unfathomable, increasingly disorderly. Post-postmodernism was, from its inception, a deliberate turn away from that cynicism. A way of finding emotional catharsis even after logic dissolved. Umineko operates within this framework, while Flower goes in the opposite direction. The postmodernists were too optimistic. They at least believed in subjective truth. In the world of The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere, even that strip of reality is shredded.

Entropy features big in the postmodern landscape, brought to literary prominence by Thomas Pynchon, who studied engineering physics and often used mathematical motifs as analogies for social concepts. Flower, too, engages with the concept of entropy, or rather revolves around it. The central murder mystery is set at the sanctuary of an order of scientists dedicated to curing death, and the way they have sought to do so involves stealing a piece of an entropic god-entity and incarnating it in human form.

As such, Flower strongly ties the concept of death to the concept of entropy. I said before that identity is the fundamental question of even the most basic mystery novel, but the same could be said for death; you'd have to go back to The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins, or maybe mystery stories made for children, to find a mystery without murder. Van Dine's rules for mystery put it emphatically:

There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel, and the deader the corpse the better. No lesser crime than murder will suffice. Three hundred pages is far too much pother for a crime other than murder. After all, the reader's trouble and expenditure of energy must be rewarded.

I love this because it's such a cavalier treatment of death in narrative, as though death, rather than a tragedy, was simply a way to kickstart a plot—or a "reward" for the "expenditure of energy" (as though a reader's energy is finite, and always being entropically lost). Indeed, many of the Golden Age detectives who found themselves amid a new murder a month seemed to take a similarly detached tack toward the whole affair. Umineko lampoons this as well; its Hercule Poirot parody, when faced with a group of people playing dead, goes on a six-man mass decapitation spree just to ensure there really is a mystery to solve.

Flower philosophically confronts the question of death as early as Chapter 002, when fan favorite smarmy bitch Kamrusepa goads Su into an argument over the moral implications of curing death. Kamrusepa takes a rationalist, "anti-deathist" perspective, stating that not only is curing death a fundamentally good thing to do, but the most good thing that can be done; that curing death would not only be valuable in and of itself, but would also lead to the alleviation of every other social ill. Su is less sure. Certainly, a deathless world wouldn't be free of social strife. But there's also another argument she flirts with: Perhaps people, like Van Dine's readership, somehow need death to orient the meaning of their lives around.

Her thought process mirrors that of the mystery genre. If the genre has absolute faith in objective truth, it also has absolute faith in utter destruction. Crimes less than the complete annihilation of a thinking being will not suffice. In such a way, even the most orthodox or classical mysteries themselves have a drop of the postmodern in them, a faith in the incontrovertible necessity of entropic dissolution, though in the form of the human body rather than society or information. It's notable to me that, in contrast, Umineko posits a sort of immortality for its victims, alive in the "Golden Land" within the Treat ending despite the objective reality of their tragic deaths, or even alive within the metafictional conceit of the Rokkenjima game board, where if the players desire they can always open up the box, set the pieces aright, a play with these characters once more. Through its use of the time loop, Flower rejects this proposal; its characters are trapped in a game without end, and ultimately conspire to escape this hellish immortality they've wrought for themselves. (Remember also that Utsushikome's role as protagonist, explicated in 000, was not to solve a murder, but to prevent it, which she fails at utterly and quickly.)

The Flower That Blooms Nowhere is still ongoing, and many of its mysteries remain unresolved simply due to that fact. I've spoken extensively to the author, Lurina, and she assures me she is committed to the solvability of the mystery, which suggests that she intends to ultimately reveal the truths behind the murders and everything else. This essay isn't intended to be predictive of the story's future (which, as of the latest updates, is heading into some of the most exciting territory yet, with many meditations on death and identity that I would love to talk about in this essay but withheld because I know many readers aren't caught up), but rather an assessment of what currently stands. What I find most fascinating about Flower is how it rejects so many of the redemptive post-postmodern precepts that imbue Umineko, despite borrowing so much of its metatextual complexity, and without retreating into the classical or even postmodern, as would seem to be the only alternative. Instead, Flower's vivisection of identity and death within post-postmodern concepts strike me as a wholly new and unique artistic direction, and once more makes me excited for the growing avant garde to be found within web fiction.

#umineko#the flower that bloomed nowhere#tftbn#umineko no naku koro ni#umineko when they cry#mystery#postmodernism#post-postmodernism

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

My dealer: got some straight gas 🔥😛 this strain is called “The Sanctuary of Apsu” 😳 you’ll be zonked out of your gourd 💯

Me: yeah whatever. I don’t feel shit.

5 minutes later: dude I swear I just saw a cross between a bird and a spider

My buddy Kamrusepa pacing: the order is lying to us

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of those things i love about tftbn is the things i only see now on my reread. Like, there's a bunch of small hints toward obvious mystery hooks like they bring up agefaking r early, they mention "people" having been thrown out of the order for not giving up what they promised to give up on their initiation which immediately transitions into □□□□□ having given up his obsession with Wen but obviously still pursued it (actually, this doesn't really sit well with Neferuatens explanation of his expulsion...), the sactuary on the Atelikos being handbuilt (according to Bardiya) which would take a long time, but was supposedly bulit in the "aftermath of the g interplanar war" but before the treaty that ended it, aso I never even thought of these things on my first readthrough, even though i knew it was going to be a mystery, but with later context they really jump out at you... Is this what people call rereadability?

#tftbn#the flower that bloomed nowhere#I am also jumping to ridicolous conclusions though#like that one line seeming to imply □□□□□ came in to Apsu via the Gynakeian Entrance#Transfem □□□□□??? Or was he going that way with someone#on their behalf???#(i guess Kuroka-Shiko might be a thematic echo of the □□□□□-Wen relationship) I am definately reading to much into a vague implication...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere: 013-032

Previously: 000-012, spinoff post about entropy [all Flower posts]

Time for more flower...

youtube

...no, not that flower!

Unless...?

Welcome back to my liveblog of sorts for web novel The Flower That Bloomed Nowhere by @lurinatftbn! Shout out to the Flower discord for giving me such a kind welcome. You're making me want to go all out on this liveblog, but, I musn't...! So I'm going to try to just comment on things that jumped out as especially noteworthy rather than write down everything that went down.

Especially since... a lot happened in these chapters. We have a perfect androgyne tree thing! Magical duels! Questionable student/teacher relationships! Steamed hams! Intense political arguments at dinner! Metafictional assurance of fair play! Prosognostic events! Transgender AIs! And of course........

a murder!!!!!

...ok that one was kinda obvious. But the first body has hit the floor! I don't feel like I have nearly enough information yet to start speculating about who might have dunnit.

That's a lie. It was definitely Kinzo Ushiromiya. That bastard.

So, from the top!

We're introduced to a few of the members of the Order, with by far the most screen time going to Su's mentor and ah, kinda-girlfriend? Neferuaten. And like, damn, lot going on there!

Before I get into the meat of that - first the bit where I search a character's name on Wikipedia. Neferuaten's name is most likely a reference to an Egyptian female king/pharaoh (a rank that's apparently distinct, conceptually, from a queen) variously called Ankhkheperure-Merit-Neferkheperure, Waenre, and Aten Neferneferuaten. Most often shortened to just Neferneferuaten.

Her exact historical identity seems to be a little unclear - she may or may not be the same person as Nefertiti for example. Whoever she was, she apparently reigned for a couple of years around 1334–1332 BCE, and was then succeeded by the famous child king Tutankhamun. Or maybe Smenkhkare came in between them? Seems to be a matter of some debate. Girl really needed to leave a few more vast and trunkless legs of stone so we can figure this stuff out.

In any case, this version of Neferuaten goes way back with Su. Her introduction is to launch a magical attack on our poor girl while she's contemplating the 'everblossom'. One of those classic 'master surprise attacks the student to see how much they've learned' deals. This servers as a fine exposition for the exact mechanics of magical duels.

Zettai! Ummei! Mokushiroku!

Let's briefly note how magical duels and magic works here, since it seems like it will be very relevant later.

The more we learn about magic, the more explicit is that this system is not some natural property of the universe, but something that's designed by the mysterious Ironworkers. It seems like it's kind of an API to the Ironworker admin console. The Ironworkers wanted to make it difficult to do magic on human bodies, and therefore they designed a system for detecting what is 'human', based on three heuristics - anatomical, motion and neurological.

Humans, being the freaky little hackers that we are, of course set about figuring out how to bypass this system, and created standardised means, consisting of three spells, termed [x]-beguiling arcana. In a sense the three criteria are something like three 'hitpoints': the primary way to win a duel is to get all three spells off, thus making your opponent vulnerable to magic.

To achieve this, you can either speak the words of a spell or sign them by drawing them with your fingers - i.e. one way or the other express the appropriate string of symbols. This is risky because if you're interrupted at the wrong time, your spell can backfire and blow up, and getting a spell right requires precise pronunciation and also rapid mental maths. So the general 'gameplay' of magical duels involves attempting to disrupt the opponent's focus and aim, while fast-casting the spells that are most familiar to you.

We're introduced to a few spells that could be useful in battle, such as

Matter-Shifting (telekinesis spell with a geometric bent, used to move a cube of dirt to act as a smokescreen),

Matter-Annihilating (deletes stuff),

Entropy-Denying (essentially a shield that freezes objects and fluids in relative motion),

Air-Thrusting (creates a shockwave air blast),

Light-Warping (fucks up the light for visual cover),

World-Deafening (mutes all sound, which can interrupt casts)

Entropy-Accelerating (disrupts coherency, causing rapid aging-like effects - can be used on a 'higher plane' to disrupt all magic in an area)

Entropy-Reversing (rewinds matter along its path of motion - reference to entropy here seems a tad dubious but w/e)

It's clearly a pretty carefully thought out system - I appreciate that it's approached from the point of view of someone trying to exploit the shit out of the system and figure out what the real meta would be. It does kinda seem like if you got the drop on a wizard and shot them with a sniper rifle they'd be toast, but we'll see later that much more powerful weapons than mere chemical firearms exist in this world, and presumably in a combat situation everyone would have entropy-denying (or equivalent) shields up, so maybe that's a moot point.

Anyway, we are later informed by the closest thing to authorial voice that everything we're told here about magic can be assumed to be axiomatically true, similar to the red text in Umineko. Which pretty heavily foreshadows that this is going to be on the test, if you like!

the magical metaphysics

With apologies to Neferuaten, who will get more detailed comments shortly, there are some other big revelations about magic and the nature of this world that I should talk about while we're on the subject of magic!

In the last post I wondered whether casting magic is an innate quality or a 'skill issue' situation. It turns out the answer is sorta 'neither'. In fact, it's something that has to be unlocked, using special equipment and a particular ritual. The cost of this ritual is not yet entirely spelled out, but we definitely get an inkling. It's rather ominously implied by this exchange in chapter 22:

"We're supposed to want to save people, to make the world better. To defend a bunch of people who practically committed murder--" "You're a murderer too, dour girl." I stopped, and blinked. It took me some moments to process the words. They'd come from Lilith, who now seemed to have finished with her dessert. Now she was just slowly swirling her spoon around in the last remnants of the chocolate sludge on the plate and, occasionally, dipping a finger into her cream bowl and licking little bits of it up. Her expression was irritated, but disconnected. "All arcanists are," she said. "It's how it happens. So having fights over moral high ground like this is very stupid and annoying. Please stop."

In the same chapter, Su uses something called an 'acclimation log', in which she records her 'association' with a series of diary entries from her childhood self. It all suggests that Su's present consciousness has somehow taken over the body of another character, who we could maybe call original!Su.

A few chapters later, we find out what's the deal with prosognostic events. In fact we get a pretty extensive exposition. It turns out that iron is magical in this universe, providing access to higher dimensions, FTL and all sorts of shit. However, because the Mimikos and other worlds are running on a 'substrate' of iron - sort of like a simulation - we are told this is why they can't recursively include iron within. And since the human body includes a certain amount of iron (most notably, in the haemoglobin protein in red blood cells), it is not possible to fully realise the human body inside these artificial worlds.

a self-referential quibble

Here's how Su puts it:

A substrate cannot exist within itself. That sounds awkward when I put it so directly, but it's not too hard to understand if you think about it in abstract-- A foundation obviously can't support another foundation of equal weight and nature, because… Well, it would make nonsense of the whole premise. A book is a device for storing information, but it cannot contain within its letters everything about itself and what it contains, because that is already more than it contains. A box cannot hold another box of equal size, unless it is bent or otherwise changed. A mind cannot hold another mind…

On the face of it, this seems on the face of it... not entirely true, at least in some domains? You can run a virtual machine program on a computer, representing any particular combination of hardware and software, which is from the perspective of software 'on the inside', essentially indistinguishable from a computer running on 'bare metal' hardware. The only real difference is that operating the virtual machine has some computational overhead, so it will be slower. The more virtual machines you nest, the slower it gets.

But 'from the inside', the only way to tell which layer of virtual machine you're on would be to refer to some kind of external clock signal (which can trivially be spoofed) and notice that it's running slower than it should!

We could also mention here the subject of quines, which are programs which print their own source code.