#the american war of independence

Text

everytime i tell europeans my favorite cuisine is texmex & sonoran they are like “American bastardized Mexican food?” and i feel like im going insane. its not bastardized. its their fucking cuisine.

#never spoke to a tejano person in their life#im left to the task of explaining the mexican american war#as well as the texas independance#and how the border moved not the mexicans#and that their food with be shaped by a different geopolitical context#they get bored quickly#but i will defend the chimichanga

46K notes

·

View notes

Text

Who Wants a Non-Hessian German Troops of the American Revolution Uniform Identification Flow Chart?

Now you too can roleplay as a harried British staff officer trying to identify which troops are encamped where, or a devious rebel spy collecting intelligence.

As folks may or may not know, only roughly 50% of the German state troops who served the British Crown during the American Revolution were “Hessians” from Hesse-Cassel. There were six other states that provided “subsidy troops.” Here’s how to tell them apart at a glance.

Are their uniforms predominantly dark blue? If yes, go to the paragraph numbered 4. If no, go to the para numbered 2.

2. Are their uniforms predominantly white? If no, go to the para numbered 3. If yes, those are troops from Anhalt-Zerbst. The only German state involved in the war to take its uniform and organisational cues from Austria rather than Prussia, the single Anhalt-Zerbst line regiment deployed to America wore white regimental coats faced with red. Their grenadiers wore bearskins rather than metal-faced caps (the only other German state to do this was Waldeck). One battalion also, according to one shocked British officer, had one of the most outrageous-looking uniforms of the war, including hussar hats, red and yellow waist sashes and red cloaks - these may have been “pandour” irregulars from the edges of the Austrian empire.

3. The coats are neither white nor blue, so they must be red. In this case, the troops are Hanoverian. While still mostly following Prussian style, because they shared a ruler with Britain, Hanoverian troops wore red. Five Hanoverian regiments assisted Britain with vital Mediterranean defence during the American Revolution, before going on to fight in India. They were the only redcoat Germans fighting for the Crown outside the British Army.

4. Your Germans are wearing blue coats. Are the buttons on the coat lapels arranged 1-2-1, and do the cuffs have a “Swedish” style slit to them? If no, go to the para numbered 5. If yes, they’re from Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Brunswick provided the most soldiers after Hesse-Cassel, and arguably the most rounded force, with four line regiments, one dragoon regiment, one grenadier battalion and one light infantry battalion. But whether jäger, musketeers or grenadiers, they almost all had coat buttons in groups of 1-2-1 and the slit-style cuffs. Fun fact; the Brunswick crest of a racing white horse on a red field was the same as neighbouring Hanover’s.

5. Your Germans are wearing blue, but don’t have buttons in 1-2-1 and Swedish cuffs. Do they have yellow facings, and cuffs with buttons placed both horizontally and vertically? If no, go to the para numbered 6. If yes, they are from Waldeck. This German state usually provided troops for the Dutch, but raised a new unit, the 3rd English-Waldeck Regiment, for service in America. They mostly fought against the Spanish in the Deep South, where they were decimated by disease. If the unusual position of the buttons on the cuff isn’t enough, look for the belt plate bearing “FF” for “Fuerst Friedrich,” the state’s ruler.

6. Do your blue Germans have red facings, cocked hats and unusual lace on their coats, shaped like a figure-of-eight? If no, go to the para numbered 7. If yes, they’re from Hesse-Hanau. This state was closely related (in the sense of its ruler, literally) to Hesse-Cassel, yet remained independent. While it provided a small amount of artillery, jägers and freikorps light infantry, its main contribution was a single line regiment, Erbprinz. Their distinctive features were scalloped lace on their cocked hats and the figure-of-eight “Brandenburg” style lace. There was also a Hesse-Cassel Regiment Erbprinz (even sharing the same colonel-in-chief), but they were fusiliers with caps rather than the Hesse-Hanau musketeers with their cocked hats. Check the mistake made by this artwork - these are Hesse-Hanau soldiers from the Infanterie Regiment Erbprinz, but they’re wearing Cassel fusilier caps. Bonus fact; Hanau and Cassel’s crest both features a rampant lion with red and white stripes, but there are subtle differences - they face opposite directions, the style of stripes are slightly different, and the Hanau lion lacks the Cassel one’s crown, but does wield a sword.

7. Do your blue-coated Germans have a black eagle on their flags and grenadier cap plates? If no, they’re probably from Hesse-Cassel. If yes, they’re from Ansbach-Bayreuth. This German state consisted of two provinces, Ansbach and Bayreuth (funny that). Besides jägers and some battalion guns, their main contribution was two infantry regiments, one from each of the two provinces. Their ruler’s crest was a black eagle, similar to the Prussian one.

Of course these posts don’t account for the uniforms of the jäger corps, or musicians, or any artillery, but it can serve as a rough guide. For the proper detail, you’ll have to buy my forthcoming book on the topic!

Also would be pretty cool if someone made an actual flow chart out of this, just saying!

#hessian#hessians#german#germany#german army#german military#18th century#history#military history#american revolution#revwar#american war of independence

345 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHY ARE THERE LIKE NO SHOWS OR MOVIES ON THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION LIKE ALL WE GET IS TURN, 1776, HAMILTON AND LIBERTY'S KIDS???

#amrev#American revolution#revolutionary war#liberty's kids#hamilton#1776 musical#turn washington's spies#american revolutionary war#war of independence

324 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you know that John Laurens was a spy?????

I really didn’t til today. Greene appointed him as his personal spymaster and he did a damn good job as an intelligence officer! Really, that is such an interesting fact about this man nobody acknowledges.

“John Laurens returned to his home state after the capture of Cornwallis’s army and Gen. Greene made him his spymaster. Having chaired the legislative committee that wrote the Confiscation Act, Laurens was well poised to obtain exemptions for loyalist planters willing to spy for Congress.” (- Woody Holton, Liberty is Sweet)

#amrev#amrev fandom#the american revolution#American war of independence#John Laurens#spies#history#historian tumblr#the martyr speaks

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

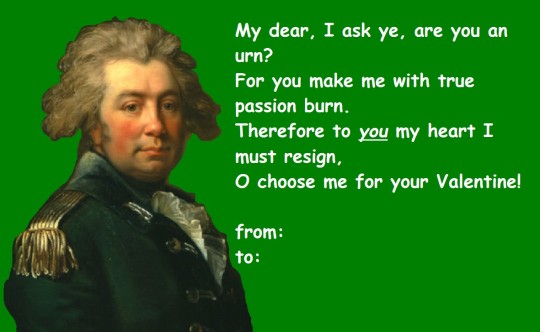

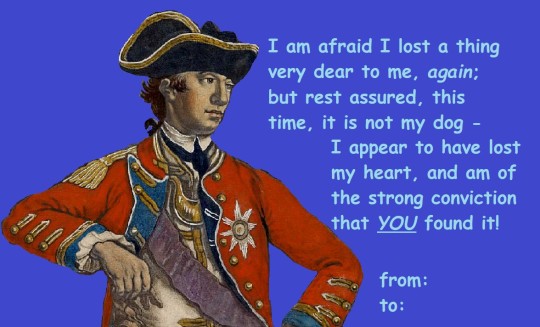

Comic Sans Valentines: British of the American Revolutionary War Edition

#there goes another round full of misappropriated quotes and deliberately terrible editing for the sake of comedic effect#american revolutionary war#18th century#history#history humour#utter nonsense#american revolution#amrev#american war of independence#benedict arnold#john andre#charles cornwallis#john graves simcoe#john burgoyne#henry clinton#william howe#comic sans valentines#valentines day

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Din: Happy Galatic Independance day!

Luke, deadpan: My dad died six years ago today.

Din: Now I feel stupid for getting you power converters to celebrate.

#star wars incorrect quotes#inncorrect quotes#the mandolorian incorrect quotes#din darjin#dinluke#luke skywalker#happy 4th of july to the americans#I think they would have an independance day#i am not american#I just love hamilton

272 notes

·

View notes

Note

petition for that long rant on revolutions here, i really enjoyed the way you laid out your facts and explained the first rant and am not too good at reading theory myself (i am still trying tho) thanks!!

Okay okay so the problem with revolutions is they get messy. Real messy. You get counter-revolutionaries, moderates, extremists, loyalists, and everything in between. One revolution turns into 5, and even if your side wins, its almost guaranteed to have been tainted some way or another along the way.

Take the first french revolution. It started as civil unrest, the estates general initially called for reform of the french state into a constitutional monarchy similar to Britain. Even king louis XVI was in support of this. But extremists wanting a republic and counter-revolutionaries wanting absolute monarchy clashed and things became more and more chaotic and violent. Eventually the extremists won, the jacobin reign of terror ensued, and 10s of thousands of people were executed. Now don't get me wrong, i am all for executing monarchs and feudal lords, but look what happened a few years later; Napoleon used the political instability to declare himself emperor, a few more years later his empire had crumbled, and the monarchy was back with Louis XVIII.

Or take the 1979 iranian revolution. It started as protests against pahlavi, who was an authoritarian head of state and an American pawn. As the protests turned into civil resistance and guerilla warfare it took on many different forms. There were secularists vs islamic extremists. There were democrats vs theocrats vs monarchists. Etc. Through all the chaos, Khomeini seized power, held a fake referendum, and declared himself supreme leader and enforced many strict laws, particularly on women who previously had close to equal rights. Many of the millions of women involved in the revolution later said they felt bettayed by the end result.

Or the Russian Revolution. It started as protests, military strikes, and civil unrest during WW1 directed at the tsar. He stepped down in 1917 and handed power over to the Duma, the russian parliament. This new provisionary government initially had the support of soviet councils, including socialist groups like the menshiviks. But they made the major mistake of deciding to continue the war. Lenins bolsheviks were originally a very tiny group on the fringes of russian politics, but they were the loudest supporters of peace, so they gained support and organised militias into an army and thus began the russian civil war. Lenin won and followed through on his promise to end the war against germany, but its a bit ironic that they fought a civil war, that killed about 10 million people, just to end another war.

Im not saying any of these results were either bad or good. They all have nuance and its all subjective. But the point i am trying to make is that they get messy. The initial goals will always be twisted.

France wanted a constitutional monarchy, they got an autocratic emporer.

Iran wanted democracy and an end to American influence, and well they ended american influence alright but also got a totalitarian theocrat.

Russia wanted an end to world war 1 and got one of the bloodiest civil wars in history.

I cant think of a single revolution in history that achieved the goals it set out to achieve.

But again, im not saying this is necessarily a bad thing, just a warning against revolutionary rhetoric and criticisms of reformism. Sometimes revolution is the only option, when you're faced with an authoritarian government diametrically opposed to change, then a revolution may be worth the risk. But it is a risk.

But if you live in a democracy, claiming revolution is the only way is actively choosing both bloodshed and the risk of things going horribly wrong over the choice of peaceful reform.

So when i go online in some leftist spaces and see people claiming revolution in America or UK or wherever is the only way out of capitalism I cant help but feel angry.

I know our democracy is flawed, and reform is slow and can even go backwards, but we owe it to all the people who would die in a revolution to try reform first.

I know socialist reform is especially hard in our flawed democracy where capitalists own the media, but if we can't convince enough people to vote for socialist reform what hope do we have of convincing enough people to join a socialist revolution. Socialism is supposed to be for the people, but how can you claim your revolution is for the people if you can't even get the support of the people?

So what I'm trying to say is; if youre one of those leftists that are sitting around waiting for the glorious revolution, doing nothing but posting rhetoric online - at least try doing something else while you wait. Join your labour union, recruit your coworkers, get involved in your local socialist parties, call your local representatives (city council, senator, governor, member of parliament, whatever) and make your opinions known, push them further left, and keep pushing.

#thank you anon this waa fun#also when i say i cant think of any revolution in history that achieved its goals#im not counting wars of independence#i know americans call the american war of independence the revolutionary war but its not a revolution l#(for reference - the first rant that anon mentions is a reblog a couple days ago about the communist manifesto)

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

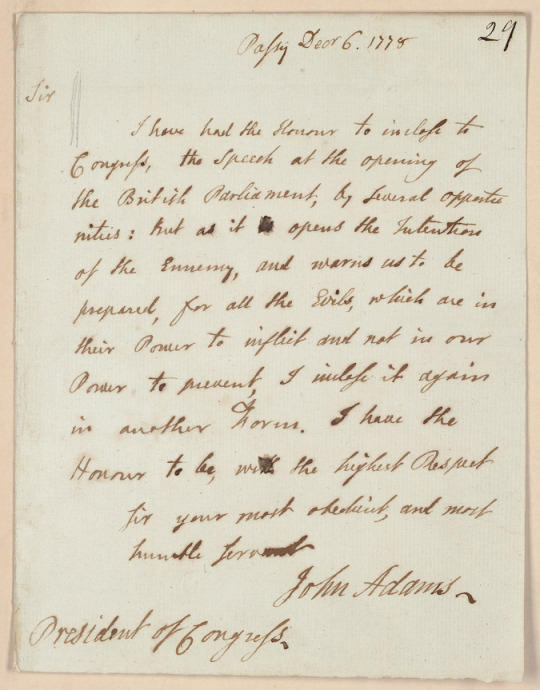

Letter from John Adams to the President of Congress

Record Group 360: Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional ConventionSeries: Papers of the Continental CongressFile Unit: Letters from John Adams

Passy Decr 6. 1778 [29 in upper right corner] Sir I have had the Honour to inclose to Congress, the speech at the opening of the British Parliament, by several opportunities: But as it opens the Intentions of the Ennemy, and warns us to be prepared, for all the Evils, which are in their Power to inflict and not in our Power to prevent, I inclose it again in another form. I have the Honour to be, with the highest Respect Sir your most obedient, and most humble servant [signed] John Adams. President of Congress.

#archivesgov#December 6#1778#american revolution#war of independence#continental congress#john adams#18th century

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

History memes #48

#funny humor#history memes#funny memes#history#funny#humor#meme humor#dark humor#american civil war#america#russian empire#russian history#russia#russian civil war#ukraine#Ukrainian independence#poland#polish independence#ww1 memes#ww1#ww1 history

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in Irish History | 28 April:

1714 – Sir Wentworth Harman, MP for Lanesborough, ‘coming in a dark night from Chapel-Izod, his coach overturning, tumbled down a precipice, and he dies in consequence of the wounds and bruises he received’.

1794 – The Reverend William Jackson was arrested in Dublin on this day in 1794. Jackson was born in Newtownards, Co Down, but spent much of his early life in England. He was a French spy…

View On WordPress

#EasterRising#irelandinspires#irishhistory#OTD#1916 Easter Rising#28 April#American Civil War#Dáil Eireann#Dublin#Dublin Castle#Eamonn De Valera#England#History#History of Ireland#Ireland#Irish Brigade#Irish History#Irish War of Independence#Thomas Francis Meagher#Today in Irish History

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surrender of Gen. Burgoyne, John Trumbull, 1821

#4th of July#Fourth of July#Independence Day#American Independence Day#art#art history#John Trumbull#historical painting#military history#American history#Revolutionary War#American Revolution#Battle of Saratoga#American art#19th century art#oil on canvas#United States Capitol#Capitol Rotunda

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

France every time an American talks about how a bunch of farmers beat the British Empire in the American Revolution:

#american revolution#france#revolutionary war#american history#best frenemies for life#american war of independence

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The newest kit - including the new sporran - for the recreated 71st Regiment (Fraser’s Highlanders) during the American Revolution! Pics (and more details) on their Facebook page, “71st Regiment of Foot - Fraser’s Highlanders, Captain Sutherland’s Company.”

#history#british army#military history#18th century#american revolution#redcoat#american war of independence#revwar#redcoats#scotland#clan Fraser#Fraser’s highlanders#71st foot#highlander#highlanders

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Basics Of American Revolutionary War Uniforms:

Basic descriptions I wrote of each layer of a Continental Army soldier's uniform in order of what you'd put on first to what you'd put on last, starting with:

Shirts:

In the 18th century, a man with a shirt was considered naked, so the shirt was a part of every outfit (although it was often covered in other layers of clothing). The shirts worn by the soldiers in the revolution were designed to be as comfortable as humanly possible, so they were very long, often stopping mid-thigh or just below the knee, loose and flowy, and had lots of ruffles at the top. Shirts also had long, puffy sleeves. The shirts were so comfortable that they would function as nightgowns too. All a man had to do to get ready for bed was take off all of the other layers of his uniform. The shirts were plain white or a yellowish colour, depending on how many times they'd been worn. Collars were high but not as high as collars in the 1790s, and sleeve cuffs were either closed by cuff links (little button things) or they'd just have cute lace at the end. Contrary to some ridiculous but funny assumptions I've heard from people who don't study historical fashion, shirts were not hard to put on, and they were simply pulled over the wearer's head like you would put on any other shirt. Shirts were closed together using buttons (a favourite of mine), linen, thread ties, or different combinations of the forementioned. Buttons tended to be small and made out of either thread, horn, leather, or even leather. Because the shirts were made out of soft, thin materials such as linen, cotton, and light flannel and were worn all the time, they were usually the first clothing items to wear out and break. Due to supply problems, there were periods of time during the revolution where men had to wear their breaking shirts and couldn't replace them. Another thing about shirts that I read somewhere (can not find the source for the life of me) is that Washington told his soldiers to wear hunting shirts because he felt that they were practical in every kind of weather. However, the site did say that they only wore them towards the start of the war and in certain regiments.

Neck accessories (for lack of a better term):

Like I briefly mentioned with the shirts, people in the 18th century had a really weird idea of what counts as naked, and they believed that a man without any kind of neck covering over his shirt was still naked. Cravats and neck stocks were two commonly worn neck garments during the revolution. Cravats were made out of silk, linen, or cotton and could be put on in a range of different ways. When they were untied, they were simply long strips of fabric. There are many ways to tie a cravat. I'm not very good at explaining things, so if you need to figure out how to tie an 18th-century cravat, I recommend looking up a YouTube tutorial. Cravats could also be accessorised with cute brooches and such. There were two different, commonly worn in the continental army, types of neckstock in the 18th century. Number 1 was made of the same materials and had the same colour as a cravat, but number 2 was dark in colour and made of leather. The biggest difference between neckstocks and cravats is how you put them on. Neckstocks aren't meant to be tied like cravats; they have a buckle on one end, so they're meant to be put on more like a belt. Oh, and in case you're wondering, the buckle always goes at the back.

Stockings:

Oh my god, I could talk about revolutionary war stockings forever. They're actually so adorable and cutesy, and I just love them. So the stockings are the pretty little white tights that the 18th century seems to be known for, and they were mainly made via knitting and were made out of either wool, cotton, linen, silk, or a fabric blend of any of the aforementioned. Stockings were usually made using knitting machines, but there were still plenty of people who made them by hand. Stockings in the 18th century were not at all short either; they went above the knee (so basically thigh highs). One of my favourite parts about 18th-century stockings is the garters that secure them into place. The garters were belt things that would wrap around their legs to make sure the stockings wouldn't fall down, and they were usually made out of leather, cloth, lace, or a ribbon tied into a bow. I physically cannot speak of these things without saying aww in my mind.

Culottes:

Also known as knee-breeches, but lets be honest, culottes sound cooler. The culottes worn by 18th-century soldiers were a bit different; instead of having a line of visible buttons at the crotch area to put the culottes on like jeans, they had fewer buttons—usually about 1 or 2—at the top of the culottes, and those buttons would be hidden by the waistcoat. Culottes in the Revolutionary War had a much higher waistband; most culottes in the 18th century had a low waistband, but culottes of the Continental Army had a waistband that went just above the soldiers actual waist. And culottes never stopped lower than the shinbone (to show off the stockings). Culottes were white or off white and were made of either buckskin, elk, sheepskin, wool, linen, velvet, silk, or fabric blends of any of the aforementioned. Culottes were very tight because they were worn so that when the soldiers were riding their horses, which they did a lot, the horse needed to feel every movement of the leg so that it could understand what the rider wanted it to do, and that was much harder if the rider was wearing super loose, flowy pants. Culottes were closed at the side of the knee with more small buttons or ties. Buttons on culottes were usually made of either metal, leather, or horn and covered in cloth or wrapped in thread.

Waistcoats:

Although waistcoats with sleeves did exist in the 18th century, they weren't as popular as waistcoats without sleeves. Going back to the weird 18th century undestanding of what is nude, a man wearing breeches, a shirt, a cravat or neckstock, and an unsleeved waistcoat would still be counted as naked. This is one of the things I see a lot of period dramas get wrong. I understand the overcoat-less look looks cool and attractive, but in the 18th century, that would be like a man going outside wearing no clothes. Oh, and another thing that a lot of period dramas mess up on is that men did not show their shirt sleeves in public; that was considered crude and abnormal; it wasn't illegal, just something you'd get judged for. There were two sub-types of waistcoats: double-breasted and single-breasted. These sub-types actually have nothing to do with breasts at all. In fact, the sub-types are about buttons. Double-breasted means a waistcoat with two rows of buttons, and single-breasted means a waistcoat with one row of buttons. Back to the uniform of the continental army, at the start of the revolution, soldiers wore single-breasted waistcoats in the most popular style of the 1750s and 1760s, but by the end of the revolution, they'd switched to wearing the 1770s style waistcoat, just going by a general pattern I've seen in changes to parts of the uniform. I'm assuming that the switch would have happened in 1779. In case you're wondering, the difference between the 1750s–1760s style and the 1770s style is their length; the former stopped mid-thigh, the latter stopped just below the hip. Waistcoats were usually made of linen, wool, velvet, silk, or a fabric blend of any of the aforementioned. They were made with all different colours and patterns, but in the continental army, they wore beige and off-white waistcoats. The waistcoat buttons were made of horn, metal, or leather and were sometimes wrapped in thread or fabric to make them the same colour as the waistcoat.

Sashes:

Sashes are a detail of the continental army uniform that I see a lot of people (and sites explaining the layers of the uniform) skip over. Continental army sashes were very important because they showed the wearer's position in the army. Green means the wearer is an aide-de-camp or brigade major; pink means the wearer is a brigadier general or a major general; and finally, blue means the wearer is a commander-in-chief. This system was made by Washington in 1775 and was used by the army throughout the war. The sashes were likely made using silk or wool. There was another, separate system with sashes; colonels, lieutenant colonels, majors, captains, sub-alterns, serjeants, and corporals could wear a red sash around their waist. However, this system was likely an optional thing because I've seen many portraits of men in those ranks from 1775–1779—they ditched the system in 1779—and I've seen only one of them where the person is wearing one of the red waist sashes.

Overcoats:

At this point, you are no longer considered naked; congratulations. So there were two kinds of overcoats in the 18th century: frock coats and dress coats. Dress coats were for super-rich people, and frock coats were for everyone else. Dress coats didn't have functional pockets, and the only reason why people thought that they were better than a frock coat was that they were expensive and sometimes prettier. Frock coats had a double-breasted front (same definition as with the waistcoats), functional pockets, and a high, round neckline. You can probably guess what kind of coat the soldiers of the Continental Army wore. They wore blue wool and linen frock coats with large gold or silver metal buttons on the cuffs and facings. George Washington and his officers wore buff-coloured facings with thick buff-coloured cuffs, and most other officers wore red facings with red cuffs. The coats had coattails and stopped midthigh, but the whole button and facing thing stopped just below the hip. The overcoats had this interesting triangle coat tail design thing at the back that I tried to figure out how to describe, but I couldn't. Here's a picture of what I mean by the two different kinds of frock coats worn by the soldiers that I mentioned in this paragraph: the one on the left is the one worn by Washington and his officers, and the one on the right is the other one:

[image credit, Samson Historical and Common Threads: Army]

I have just been told the name of the triangle things, they're called vents and they're to make sure the soldiers could ride horses without messing up their uniform. :)

Epaulettes:

The epaulettes serve the same purpose as the sashes: to declare the wearers rank; however, epaulettes are much more confusing because the epaulette system changed halfway through the war. So, the epaulette system for 1776–1779 goes like this: commanders, major-generals, brigadier generals, colonels, lieutenant-colonels, and majors wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder; captains wore a single gold epaulette on their right shoulder; sub-alterns wore a single gold epaulette on their left shoulder; serjeants wore a red epaulette made of cloth on their right shoulder; and corporals wore a green epaulette made of cloth on their left shoulder. The system from 1779-1784 goes like this, commanders wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder with 3 silver stars, major-generals wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder with 2 silver stars, brigadier-generals wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder with 1 silver star, colonels, lieutenant colonels and majors wore a gold epaulette with no stars on each shoulder, captains wore a gold epaulette on their right shoulder, sub-alterns wore an epaulette on their left shoulder, senior non-commisioned officers wore a red epaulette made of cloth and adorned with a crescent moon shape made of brass on each shoulder, sergeants wore a red epaulette made of cloth on the right shoulder, corporals wore a green epaulette made of cloth on their right shoulder and lastly, privates wore no epaulettes.

Hats:

Tricorn, bicorn and round were a must. Round hats were hats that were cocked on one side, bicorn hats were hats that were cocked on two sides and tricorn hats were hats that were cocked on three sides. Most of the time Continental army soldiers pinned them and folded them on the sides. Soldiers carrying muskets wore the hat in a different way to normal civillians, civillians would have the hat the normal way, center point forward but when carrying a musket over their shoulder, soldiers would turn their hat so that the left part was facing forward. In this position, the two sides of the hat would be almost flat so they could sling their muskets over their shoulders without having to worry about knocking their hat off. The hats white edges were made using worsted wool braid and the hat itself if expensive was made of beaver felt or camel's down painted black and if it was cheap it was just made of black wool felt. Hats were not always worn, I'd say they were more of a formality because I have seen very few portraits of soldiers wearing them.

Hat Cockades:

Hat cockades were made of ribbon or wool and were a sort of decoration to be pinned to the wearer's hat. They were like sashes and epaulettes; they indicated the wearer's rank in the continental army. And the system changed in 1779. So the system before 1779 worked like this: subalterns wore a green hat cockade, captains wore a yellow hat cockade, majors and brigade majors wore a red hat cockade, colonels wore a pink hat cockade, and lieutenant colonels wore a green hat cockade. In 1779, they changed it to honour and celebrate America's military alliance with France, so the colourful insignia were removed, and instead every soldier, regardless of rank, wore a plain black and white hat cockade. French soldiers had a cockade with black in the middle, surrounded by white, and American soldiers had a cockade with white in the middle, surrounded by black. Later on, in 1783, the black and white cockades were named the union cockades and were to be worn on the left breast, close to the heart.

Shoes:

There were actually a few periods of time during the war where some of the soldiers didn't have shoes, such as during the Christmas Day crossing and the winter of 1777–1778. But when they were supplied with shoes (most of the time they were), they wore one of two styles. The classic 'little lad' shoes, as I call them, and riding boots 'Little lad' shoes were shoes made with black leather and secured with a buckle. Little lad shoes had a small heel bit at the bottom, likely meant to make the wearer look taller because, despite tall people being considered the most attractive, most people in the 18th century were very short. Riding boots had an even higher heel and a part at the top of the boots that could be rolled down to fit the wearer. When rolled down, they just look like normal riding boots but with brown cuffs at the top. Interesting shoe-related fact that I thought would be cool to put here: in the 18th century, they didn't make right or left shoes; they made what they called straights, and you were meant to switch which foot you wore them on every day to 'wear them off evenly'. Riding boots were made with leather and were black on the outside and brown on the inside. Riding boots were very tall (they went under soldiers' kneecaps) and worn for the same reason as culottes, to make horse riding easier. It's meant to prevent saddle pinching, have a sturdy toe to protect feet while on the ground, and have a big heel to prevent slipping through stirrups.

Hair:

Originally I planned on not mentioning it on this list because it's not something that you can wear but there were uniform rules about hair in the continental army so I guess it is technically part of the uniform. In the 18th century they viewed men with facial hair was considered wrong and unusual in normal day-to-day life so if course it wasn't acceptable in a military setting. In the continental army they had a rule that men needed to shave every three days. They went against this rule a few times but only when they were desperate. Now on the topic of hair as in, not facial hair, the hair on their head was usually tied into a low ponytail with a blue ribbon or - for some men - cut short. 18th century men LOVED their long hair and did not want to cut their hair short even though they were told it should prevent lice. Wigs and hair powder were fashionable in the 18th century but not many men could afford wigs and it's not like they had a ridiculous supply of hair powder so most of the time they had their natural hair colour showing.

It's important to note that this is just the standard uniform that most men wore; each regiment had its own unique uniform, so if your project has anything to do with a specific regiment, either do your own research or ask me about it in the comments or my asks. This is also post-1775 because 1775 had no uniform. If I have gotten anything wrong, please do not feel afraid to correct me in the comments, and I'll edit the post.

Sources:

https://historyofmassachusetts.org/uniforms-revolutionary-war-soldiers/

https://www.srcalifornia.com/flags/revuniforms1.htm

https://www.bostonteapartyship.com/uniforms-of-the-american-revolution

https://ufpro.com/blog/american-revolutionary-war-study-military-uniforms-across-battlefield

https://www.washingtoncrossingpark.org/continental-army-clothing/#:~:text=Over%20their%20shirts%2C%20soldiers%20would,unit%20a%20soldier%20belonged%20to.

https://www.crazycrow.com/site/tricorn-hat-history/

https://www.si.edu/object/george-washingtons-uniform%3Anmah_434863#:~:text=This%20blue%20wool%20coat%20is,buff%20wool%2C%20with%20gilt%20buttons.

http://www.colonialuniforms.com/revolutionary-war-coats.html

https://www.berkleyhistorical.org/revolutionary-war-uniform

https://www.samsonhistorical.com/en-ca/products/mens-riding-boots

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riding_boot

#american revolution#american revolutionary war#amrev#american history#revolutionary war#history#historical fashion#fashion history#18th century#18th century fashion#continental army#military history#military uniforms#war history#war of independence#On-partiality's rambles

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Gray! What are you doing here without your uniform?"

by Norman Mills Price

Illustration for "Love and the Lieutenant" by Robert W. Chambers

#great britain#england#britain#british#america#north america#revolutionary#romance#novel#history#art#british america#revolution#american revolution#horses#woods#forest#love and the lieutenant#american#american war of independence#robert william chambers#robert w chambers#norman price#norman mills price#american revolutionary war

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

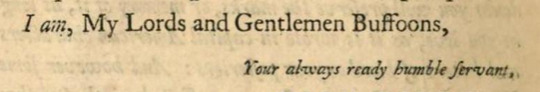

Oh, the subtlety of 18th century satirical plays. Almost lends itself to a tag game.

The dedication even has a more violent interpretation of what we today might call an 18th century second cousin of the booty shorts meme!

And I think I will steal this closing line for my own correspondence. ;)

The play is The Fall of British tyranny: or, American Liberty Triumphant, a Tragi-Comedy, by John Leacock (1776), a relation of Benjamin Franklin's.

#18th century#satire#john leacock#american revolutionary war#american war of independence#amrev#1776#the fall of british tyranny#or ameriican liberty triumphant a tragi-comedy

30 notes

·

View notes