#women in ancient Greece

Note

Hello! Dropping by to say that I’ve been loving how much attention DwtL has been getting and I’m devouring the new Cambridge Companion edition on ATG lol. Super interesting stuff, and it’s explained in a way that makes sense to someone like me who has no official humanities research background—and thank you for always entertaining our questions :)

A little unrelated to ATG, and more so an overall question. Something that has always intrigued me was the dichotomy between revered goddesses in Ancient Greek religious practices, and the way the society treated its own women. (Athena = goddess of intelligence, among others = super derogatory attitudes toward women’s intellectual capacity?) Not limited to Greece only, of course: so many ancient cultures worshipped female deities, but suppressed their own women. I’m wondering if you had any theories for why this phenomenon persisted, because it’s been something I was mystified by for a while now.

First, thanks. I'm glad that more people seem to be discovering the novels, and apparently liking them well enough. And YES, the Companion is a great new addition. I'm especially pleased that Cambridge decided to price it such that more people can actually afford to buy it, besides academic libraries. That was one big problem with the prior one (2003) from Brill.

Down the decades (centuries) a lot of folks have asked your question! It’s one reason I point out that the status of goddesses (and heroines) shouldn’t be taken as indicative of the actual power or even agency of women in ancient Greece—although that also varied from place to place.

Time for my periodic reminder: ancient Greece wasn’t a single country. It was a series of independent city-states. Each of those belonged to one of three major (and a couple minor) linguistic dialects with their own unique social and religious traditions.

E.g., there’s not really such a thing as “ancient Greece.” That was a post-Persian War construct that owed more to propaganda than reality.* “The Greeks” fought each other more than they fought anybody else until quite late.

It’s very easy, especially at an intro-level, to accidentally conflate Athens with ancient Greece. Partly, it’s an evidence problem. Most of our evidence about ancient Greece comes from ancient Athens.

When it comes to women, this results in a particularly negative picture of female agency in pre-Hellenistic/pre-Roman Greece. Women in Athens were particularly disempowered, both (te) legally and (kai) actually. Let me explain that last.

Legal power = what a society ostensibly allows

Agency = what actually prevails, positively or negatively, in contrast to actual power

It’s important to recognize this distinction. Down the millennia, women have got rather good at circumventing legal restrictions via “subversive” power. We all know this. It’s why someone like Olympias got slammed by the likes of Plutarch. She didn’t “know her place.” Never mind that her legal “place” in Epiros versus Macedon versus various southern Greek city-states varied. Women in ancient Greece often found ways to exercise power outside legal bounds. Rather than “illegal,” we should refer to this as “alegal.”

Yet supposed legal power can be deceptive the other way too: it my imply more power than women actually have…just ask any rape survivor who has to testify in court in the face her reputation being smeared by the defense.

So, all that laid out as a basis, let’s look at mortal women vs. immortals.

Next point of definition: immortals are immortals not because they’re “good” or should be imitated but because 1) they don’t die (although some can be killed), and 2) they’re more powerful than mortals. They don’t play by the same rules and aren’t held to the same standards of “proper” behavior. Afterall, Zeus married two of his own sisters (Demeter, then Hera).

Religious festivals were also known for allowing “transgressive” behavior normally restricted in regular/normal/profane time. So, for instance, during the annual Thesmophoria, married women left their families to camp out together and form their own “city-state,” even electing temporary magistrates to run this 3-day city-of-women within the larger polis. Young girls on the cusp of their periods in Attika went camping to play the bear for Artemis at Brauron (and apparently other places). Etc.

Religious festival served an important function in ancient Greece, providing much-needed interruptions to the drudgery of daily life. In antiquity, relatively few cultures had regular “breaks” like weekends. Rather, religious festivals provided this function; these might range from a half-day break to something a week long or more. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that divine behavior was considered exceptional. The sacred (numinous) was sharply divided from the profane (normal).

Additionally, it’s no surprise if farming societies, or any society with a strong connection to the earth, should develop powerful goddesses. There are, of course, male fertility deities, but Mother Nature/Mother Earth is nearly universal. The only religion I can think of where the earth is male and the sky is female is ancient Egypt. (Recall Isis’s starry robe!) There are probably more, but it’s not exactly typical.

I’m not getting into the much-fraught debate about why women’s power in most historical societies has been less than men’s. Theories breed like hydra heads. But it is pretty well recognized that in societies where women had some control over their fertility (when to have babies, and how many), as well as independent control over their finances, their social status was higher. Beyond that, the best we can say is that which societies developed higher status for women depended on a constellation of factors.

Ironically—and perhaps counterintuitively—these factors didn’t involve the relative importance of female deities. Perhaps for reasons outlined above. Not all societies saw their divinities as living in ways mortals should imitate.

In her groundbreaking Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves—one of the first books to really look at the role of women in ancient Greece—Sarah Pomeroy herself noted the problem with the status of goddesses versus the status of flesh-and-blood women. Discussion of women in ancient Greece has grown more nuanced since. For a great little overview, let me recommend Lin Foxhall’s Studying Gender in Classical Antiquity (2013). I love this book because it looks at more than just texts (which is Pomeroy’s more traditional, Classical approach). Foxhall uses a lot of archaeology, which, when it comes to women (and slaves, for that matter) really fleshes out our perspectives. There’s also the more recent Exploring Gender Diversity in the Ancient World (Allison Surtees, Jennifer Dyer eds., 2020). It’s one of those great “collections” where you get the advantage of multiple voices contributing. It’s more about gender variance than women, but I quite like it. Last, let me also recommend Helen Morales’ Antigone Rising, which looks at Classical myth today, or reception studies. Morales is one of those Classicists who (like me) thinks it important to engage with the wider public, but she’s rather more prominent and respected. 😉

So, there’s some good, reliable literature to get you off the ground too, most intended for a non-specialist audience. (I’d tackle the first two and last before trying the collection, which is more specialized with some linguistic discussions, etc.)

——-

* Even in the Greco-Persian Wars, more Greek city-states didn’t fight the Persians than did!

#asks#Greek women vs Greek goddesses#women in ancient Greece#why is the status of Greek women so low when they also worshiped goddesses?#ancient Greece#Classics#religion and the status of women

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

There's a mention of a ancient Greek couple who were both philosophers and the man was actually very supportive of his wife, but society back then condemned such actions because women had to stay at the house etc. So a man ripped her clothes and she was so unfaced by that she actually made a good comment about it to shut him off, but i don't remember her name.

I’d swear I had answered an ask about her but I can’t find it. Anyway, I believe you are talking about Hipparchia of Maroneia, wife of Krates. They were a couple of cynics, who lived in the late 4th century BC. Hipparchia had eagerly adopted a very masculine lifestyle. They lived on the streets, she wore a man’s clothes. And she was reportedly crazy for unattractive Krates, to the point of baffling everyone including her parents and Krates himself. Hipparchia threatened her parents she would kill herself if they did not marry her to Krates, so the parents asked Krates to talk some sense to her. Krates removed his clothes and said “that’s all the bridegroom can give you” but apparently that was enough for Hipparchia. They got married and were inseparable ever since.

Hipparchia had a long beef with the philosopher Theodorus the Atheist, and once she teased him with some mocking sophisms like “if it’s okay for Theodorus to beat himself up, then it’s okay for Hipparchia to beat Theodorus!”. Theodorus then pulled up her garments and asked what was her business away from the loom. Hipparchia was not phased one bit and said something across the lines of “Isn’t it very reasonable for one to prefer philosophy over the loom?”.

#greece#Ancient Greece#Hipparchia of Maroneia#ancient Greek philosophers#women in Ancient Greece#Ancient Greek women#greek history#anon#mail

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#history#historyblr#history notes#world history#world history notes#western civ#western civ notes#western civilization#western civilization notes#western civ 1#western civilization 1#western civ 1 notes#western civilization 1 notes#greek#greece#ancient greece#ancient greek society#greek society#women in greek society#women in ancient greece

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Attic black-figure hydria from ca. 520 BC, depicting women filling their hydriai with water collected at a fountain house.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

in hills made of coarse earth and honey🏺

✦ find me on instagram @the.flightless.artist ✦

#art#illustration#digital art#drawing#digital illustration#procreate app#digital drawing#digital artist#procreate art#ipad pro#ancient greece#ancient greek art#historical illustration#historical aesthetic#historic fiction#greek aesthetic#oh to be them#greek women#women in art#female friendship

655 notes

·

View notes

Text

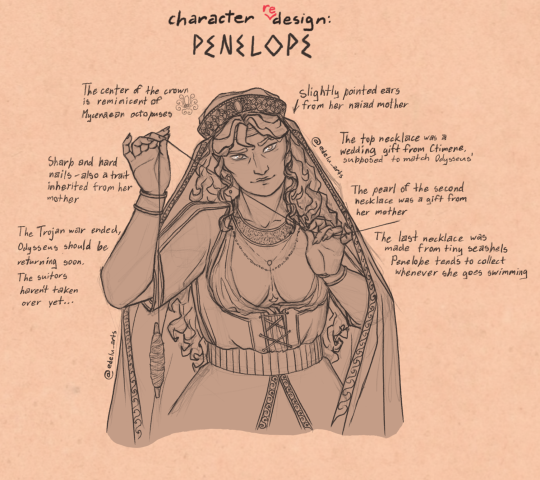

Really happy with how she turned out! I decided to give her some naiad features, inspired by this post and it was really fun! I hc that she can breathe underwater (even though she doesn't have gills. Do naiads have gills?), although I am not sure if she can do it freely or for a limited amount of time 🤔

The fabric piece covering her chest was loosely inspired by 18th century neckerchiefs, because I wasn't sure how the Mycenaean open chest fashion would fly with the censorship here or on other platforms ¯\_(• ▽ •;)_/¯

#I can leave comments and reblog posts again#yay#the odyssey#tagamemnon#penelope#character design#my art tag#I hc that she took over Odysseus' duties while he was away and got to be a reigning queen for about 10-13 years#until the suitors took over. It's a pretty long rant and I can't fit it into tags#this is her design before that#her being a ruler wouldn't really have been possible by Homer's time because of how the ancient Greece treated women#but since the story was set in Mycenaean Greece... maybe? Just maybe she could have enough authority for the assembly to take her seriously#epic the musical#epic the musical fanart#greek mythology#maybe this hc would change as I learn more things about history#but for now it's here ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

428 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women in History Month (insp) | Week 4: Dynastic Daughters

#historyedit#perioddramaedit#women in history#women in history month challenge#my edits#mine#marie anne de bourbon-conti#princess hexiao#hanzade sultan#caroline bonaparte#marie-thérèse-charlotte de france#princess fukang#gorgô of sparta#french history#chinese history#ancient greece#17th century#18th century#19th century#11th century#6th century bc#5th century bc

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dancing through the eras ✨👭🏺

Happy #WomensEqualityDay everyone!🧡 Today I'm thinking of all the women of the Ancient Mediterranean, whose lives and dreams we still continue to learn about today with every discovery✨

#womens equality day#magna grecia#tagamemnon#flaroh illustration#ancient history#art history#ancient greece#greek mythology#ancient mediterranean#tomb of the dancers

444 notes

·

View notes

Text

Battle Scene by Lionel Royer

#lionel noël royer#lionel royer#art#battle#ancient#antiquity#classical#classical antiquity#neoclassical#neoclassicism#ancient world#europe#european#war#history#cavalry#soldiers#ancient greece#ancient greek#ancient rome#ancient roman#goddess#noblewoman#women#woman#fortress#battlefield#ships#horses

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

During the second or first century BCE, a woman pretended to be able to control the moon. This was Aglaonice, who is regarded by some as the first known female astronomer.

She’s mentioned in the writings of Plutarch and the scholia to Apollonius of Rhodes and lived in Thessaly, Greece. Being “skilled in astronomy”, Aglaonice used her knowledge to predict eclipses and make people believe she caused the moon to disappear.

According to Plutarch:

“Thoroughly acquainted with the periods of the full moon and when it is subject to eclipse, and, knowing beforehand the time when the moon was due to be overtaken by the earth’s shadow, imposed upon the women, and made all believe she was drawing the moon down.”

The scholia adds that Aglaonice lost a close relation as a punishment for having angered the moon goddess.

Interestingly, Thessaly is associated with women skilled in astronomy and occult practices. Several female astrologers from the third to first centuries BCE were for instance known as “The Witches of Thessaly”. These women were said to study the movements of the moon and trick people into believing that they caused lunar eclipses.

In Plato's Gorgias, Socrates mentions the "Thessalian enchantresses who, as they say, bring down the moon from heaven at the risk of their own destruction."

Today, a crater on Venus bears Aglaonice’s name.

Feel free to check out my Ko-Fi if you like what I do! Your support would be greatly appreciated.

Further reading:

Bicknell Peter, "The witch Aglaonice and dark lunar eclipses in the second and first centuries BC."

Chrystal Paul, Women in Ancient Greece

Plutarch, On the failure of oracles

Plutarch, Conjugalia Praecepta

Reser Anna, McNeil Leila, Forces of Nature: the women who changed science

#aglaonice#history#women in history#women's history#women in science#herstory#greece#ancient greece#antiquity#scientists#astronomy#historyedits#1st century BCE#ancient world#historical figures

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

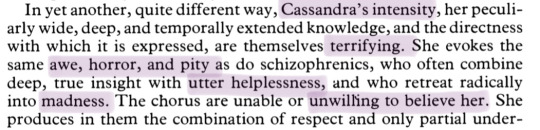

— On Cassandra of Troy

"Cassandra" by Florence and the Machine // "Cassandra" by Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys // "A Thousand Ships" by Natalie Haynes // "The Cassandra Scene in Aeschylus' Agamemnon" by Seth L. Shein // "Ajax and Cassandra" by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein // "Elektra" by Jennifer Saint // "Cassandra of Troy" by Jan Drenovec // "mad, mad, mad" by @diradea // "mad woman" by Taylor Swift // "Helen and Cassandra" by Al Stewart // "Cassandra of Troy" by Evelyn de Morgan // "The Daughters of Troy" by Euripides

#cassandra of troy#tagamemnon#web weave#web weaving#mental illness#the iliad#trojan war#classics#ancient greece#mad woman#art history#apollo#euripides#elektra#greek retelling#greek women#light academia#psychic#dark academia

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Putting my text post hands to classical use

✨main characters in my working thesis on Greek tragedy: there’s a murder in the oikos✨

(pt2)

#tagamemnon#guess my special interest#Greek tragedy#classics#Medea#deianira#clytemnestra#cassandra#dionysus#pentheus#the bacchae#libation bearers#women of trachis#agamemnon#maenads#herakles#hercules#greek mythology#ancient greece#klytaemnestra#medeia#bakkhai#trakhiniai

99 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In ancient Greece, women were forbidden to study medicine for several years until someone broke the law. Born in 300 BCE, Agnodice cut her hair and entered Alexandria medical school dressed as a man. While walking the streets of Athens after completing her medical education, she heard the cries of a woman in labour. However, the woman did not want Agnodice to touch her although she was in severe pain, because she thought Agnodice was a man. Agnodice proved that she was a woman by removing her clothes without anyone seeing and helped the woman deliver her baby.

The story would soon spread among the women and all the women who were sick began to go to Agnodice. The male doctors grew envious and accused Agnodice, whom they thought was male, of seducing female patients. At her trial, Agnodice, stood before the court and proved that she was a woman but this time, she was sentenced to death for studying medicine and practicing medicine as a woman.

Women revolted at the sentence, especially the wives of the judges who had given the death penalty. Some said that if Agnodice was killed, they would go to their deaths with her. Unable to withstand the pressures of their wives and other women, the judges lifted Agnodice's sentence, and from then on, women were allowed to practice medicine, provided they only looked after women.

Thus, Agnodice made her mark in history as the first female doctor, physician and gynecologist. This plaque depicting Agnodice at work was excavated at Ostia, Italy and is now on display at the British Museum.

[Scott Horton]

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Woman playing kottabos. Painting attributed to the Bryn Mawr Painter, c. 480 BC

Source: https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/287713

The Bryn Mawr Painter is the name given to an Attic Greek red-figure vase painter active in the late Archaic period (c. 500 – 480 BCE).

The Bryn Mawr Painter was named by Sir John Beazley for a plate in the Bryn Mawr College Art and Artifact Collections (the Bryn Mawr Painter's namepiece).

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bryn_Mawr_Painter

0 notes

Text

I was investigating old Mycenaean frescoes when suddenly something caught my eye.

Is that

Is it me or does her necklace look like it has tiny ducks? Or am I just seeing things?

#it would be so cool to think ancient women were wearing cute duck necklaces#even if I am seeing things I’m going to pretend it’s absolutely true#mycenaean#Bronze Age Greece#greek mythology#because I’m going to imagine helen of Troy/Sparta wearing this#the Iliad

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

"the vast majority of legal persecution against early queers was focused on men" ARE YOU INSANE

#rot.txt#DO YOU KNOW HOW LONG WOMEN WERE FORCED TO MARRY MEN OR DIE. HUH. WHERE AM I#this is from the section in the new hbomberguy video where he talks about james somertons misogyny and lesbophobia btw#SOMEONES BITTER THAT WOMEN KISS IN CARTOONS SOMETIMES!!!#AS IF THAT ERASES THOUSANDS OF YEARS OF MISOGYNY IN SO MANY CULTURES!!!!!!! GOOD GOD#sorry somerton is just so insanely stupid i cant get over it. why is he like that#like i dont know maybe this isnt important but i remember being asked as a kid to pick a greek city state to live in#but i was a girl. so none of them were good choices because apparently i would be forced to have children no matter which one i picked#and i guess it just stuck with me. if the boys liked to fight they got to pick sparta and if they liked to read then it was athens#but what did the girls get. a little more freedom in certain places but ultimately the same expectation. have babies or die#in hindsight there were definitely options in ancient greece#but my teacher didnt tell us that. we just had to write about whether we would like to have slightly more rights or not#OBVIOUSLY gay men have historically faced discrimination but saying that it wasnt as focused on women is just unbelievably stupid#sorry i dont know if any of this made sense#lesbophobia tw#misogyny tw

75 notes

·

View notes