Fascinated by narrative in all forms, I write reviews for film and occasionally other media, as well as analytical articles on storytelling. I have degrees in English Literature, Film Studies, and a PhD in studying stop-motion animation. I co-host Through The Wind Door, a book club podcast where we discuss the New Century book / audiodrama series, among other media.I hope to grow and love, and I believe art and storytelling helps nurture both those things.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

A Return

Well, it's nice to see this whole thing is still here underneath all this dust. How are you guys? I hope life has been kind, and that you are all as creative, positive, and driven as I remember.

It has been years since I posted on here, so all of this will take some getting used to. But I miss the process and the catharsis of having a space where I could express myself and push myself to make articles I could be proud of, even if it was only ever me reading them. I've been lucky enough to have had other venues and accomplishments in the intervening years that have been fulfilling in their own way. But sometimes, you just want a humble blog to call your own, you know?

Special thanks to the School of Movies community, who I have been talking films and other media with online for years. You're all wonderful people, and maybe with my own space here I can stop flooding some of the Discord channels with paragraphs of text on this or that movie and tv show, eh?

Anyway, this will all be a bumpy return where not everything falls into place all at once. So if you're still here, bear with me as I tidy the place up a bit and get back into the swing of all this. And if I'm just talking to myself, then even better!

I'll be back soon with two best of 2023 posts to get us started, as well as some completely out of context episode write-ups for The Zeta Project, an obscure show that I have been watching and putting together writeups on-and-off on the School of Movies community discord. That's just to tidy up and settle some old business. From there... who knows? But I can't wait to find out.

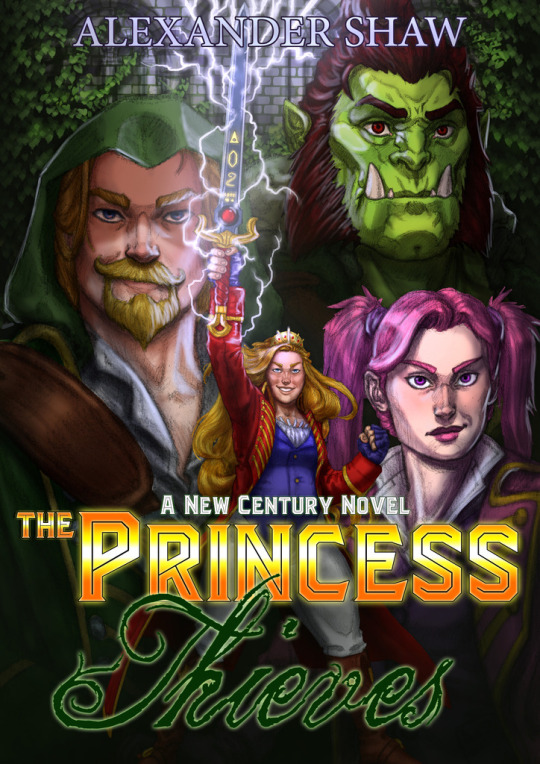

In the meantime, you can catch up on what I've been up to over at Through the Wind Door, a podcast I started with a friend of mine to talk about New Century. You remember, that book series I kept gushing about and told you all to check out? Well, it's still good. Better, even, and there's been a whole bunch more since we last talked. The latest one is called Castle of the Moon, and it has a lady Dracula and terrific Gothic Sex Appeal, a term I coined once when discussing the Castlevania Netflix show.

Wait, did you guys watch that show? I feel like that's one tumblr would have gone nuts over. Really need to check out Nocturne soon...

Anyway, I've been on this podcast since 2020, my co-host and editor talk through each chapter of each book (just like my episode / chapter write-ups I used to do back here in the day). We have interviews with the author and his cast of voice actors, and they are all not only lovely people, but talented as all heck. We also have tangent episodes where we talk about other media that captures our attention, like introducing my co-host to 10 classic horror movies, or Insomniac's Spider-Man 2. Actually, here, let me show you the first part of our multiple episode recording session on that one, that's a pretty good place to start.

Well, here we go again and all that. See you again soon!

0 notes

Text

SteamHeart Episode 20 Reactions

Chapter Twenty: Off-Road Warriors

You can listen to the full episode here.

Well damn, that was an intense dose of adrenaline via audio, wasn’t it?

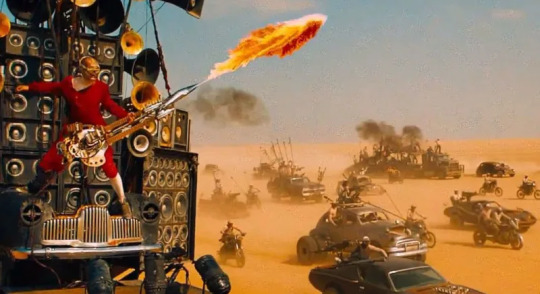

Raven immediately sets the foreboding tone, a notable change from the sweet tranquillity of the previous chapter’s closing moments. His grave description of the convoy of Mad Max-looking scary-crazy-bastards (and yes, this is about to be a Steampunk Fury Road episode, and you should have no objections to that) coming over the horizon sells the real danger that these men represent. The language paints a captivating yet frightening picture of demented vehicles, using harsh consonants to convey the sturdiness of these reinforced crafts, and hissing adjectives to emphasise the sharp, hostile shapes of these clawed, pointed carriages. Best line of the section is certainly “nothing was uniform save for the manifestly apparent expulsion of normality”. It instantly cements the chaotic, violent mindset of the men approaching the mine.

These men call themselves the Southern Cross. Among their number is a man who’s fashioned himself into a bear (the talons fixed to his limbs make me think of a twisted, older and more cruel version of Miguel and his mongoose claw), and, as the band blows their own war trumpets in an act that is as aggressive as it is indicative of their own inflated self-importance over others, the ensuing danger becomes intensified, and chillingly unavoidable. We get the first glimpse of their leader, who wears a horse’s skull and appears to fancy himself a pale rider of death with the white, bone-like motif of his carriage and horses (I’m picturing Overwatch’s Reaper in both appearance and edgy lack of self-awareness). A lieutenant riding ahead of the pack addresses Raven. While Raven is the one who embodies the more dignified aspects of the bird with whom he shares his name, this lieutenant is the one who resembles a squawking, shrill parrot, wearing a beaked plague doctor’s mask and shrieking demands at Raven. He claims that “the Lord of Brimstone” has arrived. Oh this is going to go well.

Raven dashes inside, hurriedly relaying the situation to the others. Within minutes, the few remaining mine workers and the team have brought Tabitha, who, lest we forget, is still going through labour (but still exhibiting her leadership skills even now by issuing orders, reinforcing that whole theme I talked about last time about motherhood / pregnancy not getting in the way of authoritative women being damn good at their jobs), inside SteamHeart. They don’t have enough soldiers to defend this post, and help isn’t coming, so things are looking grim. Even so, Annie assures us that “we’re not dying here like rats in a trap. Hell, that’s like, my one rule.”, and Laureta Sela’s delivery of that second part alleviates some of the tension by getting a chuckle out of me with that great line. As the group approach the gates, however, the pressure of the situation is once again felt as Harry informs the team that, even with SteamHeart’s technological superiority, it will take some serious damage if it charges headfirst into the enemy through the gate, and likely won’t be able to break free of them if it does so.

Annie starts a dialogue with them through the loudspeaker. Abigail wanted to try, demonstrating her continuing desire to work on being a better figure of authority after giving the speech to the theatre a few chapters back, but Annie bluntly shoots that down as she knows they’ll have a better chance if she takes charge of this. Even so, it goes about as well as you’d expect – they don’t heed Annie’s firm warnings, and spout off rhetoric that, in addition to being violently psychotic, is grossly suggestive. Both the birdman and horse leader demand they “open wiiiide, each and every one of you; we are coming in!” Eeurggh… fuck these guys.

The team devise a plan of escape after Jae-Hyun proposes he opens the gate to give the rest of them a chance, acknowledging the certainty that this will result in his own death. His brushing of Tabitha’s cheek indicates the loyalty and love he has for his leader who he will lay down his own life for. He steps out of SteamHeart to meet his fate, adjusting his hat as he does so; if clothes maketh the man, then this act highlights the dignity of this man in the face of these monstrously dressed, hollow creatures who call themselves men. The Southern Cross enter the mine after Hyun opens the gates, and the plague doctor spouts more inane speeches about surrender being the sensible choice in the face of such a rapturous occasion (resembling a combination of Loki in the first Avengers saying “isn’t this so much easier?!”, and a Jim Sterling character). In an instant, Harry springs SteamHeart into action, shooting forward and knocking horses and riders aside as it does so. The episode has been building anticipation to this moment – things are going to kick off hard.

Jae-Hyun pulls the squawking doctor off his horse, and the response of arrows shot in his direction kills both men, though only the doctor meets his death with a scream. I’m torn on Jae-Hyun’s death, as it feels as if we were barely just starting to get to know this coolly tempered character, and the stern composure with which he met his death makes him someone I wish we got to spend more time with. However, I also think a character like this really helps heighten the stakes of the ensuing sequence, as well as hammers home the point that the victory of our heroes doesn’t come without sacrifice. The resilience Jae-Hyun showed as he met his death in order to save the lives of others, while still demonstrating a fighting spirit that showed he was a man who wouldn’t let monsters like these do what they wanted without retribution, makes the most of the small amount of time we spend with him. If we were to have a character with such a journey within SteamHeart, and I think that both the sequence and the story as a whole are stronger for it, I’m also glad that a specific effort is made to make this character not just a generic white guy. Instead, it’s a character of Asian descent who clearly has a defined look, style, and personality outside of what we see of him here in this book. It gives the world and the people in it a little more dimension, and reminds us that the way forward toward a more heroic and noble world is through unity and collaboration between all of us. That’s how we get to see the best of humanity. But for the worst of humanity, like the racist, murderous Southern Cross, it’s pretty satisfying to see someone of a different ethnicity literally pull them off their horse and, when it comes down to it, show that they are the better man when they each meet their deaths.

Anyway, back to the action – I’ll do my best to make my writing engaging and analytical, but to be frank, it’s so easy to lose myself in the flow of this sequence. It’s tense as hell, compelling, features detailed description of well-choreographed action, the voice actors are all delivering their lines with pitch-perfect urgency and intensity, and all of this is packaged together (in this audio version of the book) with some truly immersive editing and sound effect choices. It’s the best action sequence of New Century to date.

As SteamHeart breaks away, the Southern Cross give chase, abandoning their initial goal of the mine as they now want the technology of their craft, as well as to take out their frothing anger on the crew. The grassland beneath them is uneven, which isn’t good for Tabitha during all of this, so James urges Harry to seek the smoothest route. Individual horse riders catch up and start flinging projectiles at SteamHeart’s glowing cables, which you have to imagine is a weak point of the craft (kind of like those glowing spots on a videogame boss). Annie and Butler take position in SteamHeart’s sniping openings. Abigail and Jeremy are handing out ammo and hammering out any projectiles which pierce the hull of the craft, showing that this thing isn’t impervious to damage, and will fall if it takes too much. Harry is doing a mixture of evasive and ramming manoeuvres, resulting in some awesome displays of destruction as enemy carriages splinter, flip, and crash. God, this is good stuff to listen to.

James takes over narration from Raven (incidentally, Raven was a good choice for this first part, as his journalistic ability to report the specifics of events puts you right in the action of this sequence). He recruits Jeremy, instructing him to sterilise some linens using steam from the craft’s internal pipes. Tabitha grips James�� hands as she fights the pain, and the two “breathe together”, something Harry and Tabitha did at the end of the last episode – there’s a lot of power in matching and sharing the breathing of someone else as they go through something hard that pushes them to the edge. James hides nothing from Tabitha when she asks him if he’s delivered many babies before; he’s assisted on several occasions, but this is the first time he’s delivered one himself. But even as weapons hammer the hull next to them, James assures with compassionate determination that they’re going to do this right, and that there will be another “little person in the world” in a short while, which is how they’re going to survive. It’s an exchange of nervous fear as everything happens around them, mixed with hopeful resilience.

We switch to Annie. An approaching enemy vehicle has attached lassos to SteamHeart. Abigail, Harry, and Annie take this in, realise how they need to counter this, and brace themselves; SteamHeart builds energy in a roaring moment of anticipation before Harry jams the wheel and hammers the breaks, making the back of SteamHeart swing like an almighty pendulum, smashing the enemy vehicle in a spectacular moment of destruction.

Now the Bear (whose cries make him sound like Tom Hardy’s Bane) and his vehicle are coming down on them. One of the Southern Cross leaps onto the windshield and embeds his tomahawk in the window and narrowly misses Harry. The proud mechanic indignantly cries out that these fuckers are “tearing my baby apart!”, and Abigail steps out the hatch to punish the window assailant by shooting him point blank in the elbow. If I recall correctly, her weapon of choice right now is a sawn-off shotgun, making the impact of this even meatier and wince-inducing [Editor’s Correction: I’ve been informed that Abigail’s weapon is a shotgun, but not a sawn-off. It’s a lever-action, short-barrel, short-stock shotgun, made for her by Harry, John Browning and William Winchester. Think Arnie during the truck chase scene in Terminator 2]. Annie asks her what the hell she thinks she’s doing, before Abby swings across to the Bear’s carriage using one of the lassos. Annie’s concern is understandable; Abigail is her charge, a possessor of the Endowment (and one who very recently demonstrated can actually put it to good use by closing these portals), and this chaotic and dangerous situation might force Annie to do what Arlington asked of her and shoot Abigail before the Endowment can be lost, which is the last thing she wants to do. We see these frantic thoughts race through her mind as she trains her rifle over the Bear and Abigail’s fight. The Bear seems to be enjoying the duel, demanding his comrades leave her alone and that he be the one to take her down. Abigail catches herself on his armour, but she spits blood in his eye, dodges his club, and, with one guided megaton hit of a punch that slows the world down to a crawl, destroys his balls.

Brutal. Awesome.

As he reels, Abigail ropes the Bear and kicks the driver, snaring him and launching the Bear into the air as Annie tags in with a shot that severs the rope and sends him flying and crashing. A feathered carriage comes in from the side, putting Abigail in danger. Annie calls out for a bottle of bourbon, and Raven assists by giving her his whisky, though he lets her know that she owes him a drink. This, and a lot of other little asides and exchanges during this sequence is what communicates the character of the people engaged in this fight, which makes it all the more exciting and thrilling. It’s people we know and care about who are participating in this and fighting for their lives, not just nameless faces. For that same reason, it’s also what makes it tense and frightening; I really don’t want to lose anyone in this group. But, for the time being, Raven tears a piece of fabric from his shirt and jams it into the bottle, showing he understands exactly what Annie had in mind. He lights it with his cigarette (another indication of his personality – it’s amusing to see that even in this life-or-death situation, Raven prioritises having a lit cigarette in his mouth), and Annie passes the Molotov to Abigail after she realised what the two were planning and came up to them. The synthesis of this teamwork and co-operation between multiple members of the party is really satisfying to watch. Annie lays down covering fire at the feathered carriage to distract them as Abigail slings the bottle, and Annie, like John Marston activating Dead Eye, focuses her attention as time slows down and hits the bottle with one last bullet. Wild fire ignites the carriage. Annie lets out a guttural and sorely earned “YYYYESSS!”

The last carriage is the Lord of Brimstone with his skeleton crew and his bone-white ride. They have dynamite – oh dear. Abigail extends a hand out to Annie, emphasising her support and belief in her that she can make this shot. She pulls Annie onto the roof, and as Annie is pulled into the open air before she lands next to Abby, she sees everything clearly, and identifies her target. She takes her shot immediately, and it lands, hitting the guy behind Brimstone, who was holding a stick of dynamite, which he drops inside the carriage – right next to all the other dynamite. The explosion destroys the carriage, and the leader is shot out like a comical firework, engulfed in fire, ash, and bone. Hey, he was the one who called himself “Brimstone” and obsessed over his boney white aesthetic – I’d say he got exactly what he always wanted.

With a crash, the world goes quiet. We hear a heartbeat slow down, providing a fantastic transition that takes us from the adrenaline of this sequence back down to a place where we can catch our breath. But we’re soon reminded that, while all of this is going on, Tabitha is still facing her own fight as she’s in the middle of giving birth to her baby. As James guides the baby out, provides support to Tabitha, and things escalate to their peak, the explosion echoes out behind them as Tabitha experiences her own release as the baby boy comes out, safe. The music instantly adapts to the sweet innocence of the moment. The crew re-centre themselves, Harry slows down SteamHeart, and now that everything is okay and everyone is safe… Annie punches Abigail in the side, in an act of frustration that ends up hurting her more than Abigail (Annie is after all not quite as used to throwing punches as Abigail is, as we remember from that brawl in Secret Rooms which Abby and James adapted to but which took Annie by surprise and disorientated her). Abigail responds that, while she may have taken a risky move, they all survived and made it through this. The tone is quietly triumphant, intimate, and optimistic. Our heroes have made it through this.

James shares Abby’s gratitude for the moment, and as Butler tells him he’s done a good thing here as Tabitha holds her child close to her, he experiences a sense of tranquil acceptance. James has been experiencing doubts about himself and his usefulness ever since he acquired the Endowment. At the end of Secret Rooms, he even wondered if he would be any good as a doctor after effectively losing one half of his eyes. But by helping another, by bringing this new life into the world, James has realised he can make enough of a difference to be at peace with himself, if only for now. It’s a revelation that endears me to James, as I’ve often found that, at times where I doubt my own self-worth, the best thing I can do is to seek out ways I can help other people, whether it’s in big ways or little ways. If I can make someone else’s day a little easier, then that alone makes me feel like I’m doing alright. And that’s a sentiment I love to see in fiction like this.

So yeah, this episode was a fantastic ride, and a complete triumph.

#The Inquisitive J#fiction#new century#new century multiverse#the new century multiverse#steampunk#alternate history#alternate universe#alternate history fiction#audio drama#fictional podcast#steamheart#the inquisitive j reviews

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SteamHeart Episode 19 Reactions

Chapter 19: The Woman on the Zinc Mine

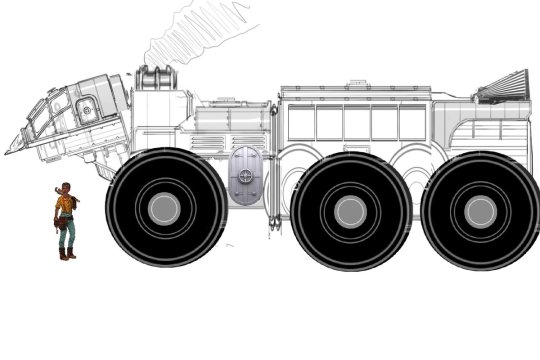

The final cover of SteamHeart is really something else - and yes, I’m going to be using it more for these posts as I go on.

You can listen to the full episode here.

Having arrived in Missouri, the party make their way to the zinc mines where “Agent Z” resides. Abigail is uneasy as she assesses the fortifications, reminding herself of her time at Weirwood where, due to her position as one of Katherine’s most trusted seconds, protection and fortification of a small-scale settlement and its population was a daily concern that she became heavily involved with. Abigail knows what’s needed to keep a residence safe from those who would take advantage of isolated settlements cut off from the protection of densely inhabited civilisation, and the appearance of the yard in front of them doesn’t reassure her. They’re shown in by Jae-Hyun, a stoic gentleman who cuts a striking figure in his bowler hat. As he asks them not to get his boss too excited before introducing her, we see the bone-collecting, piano-playing, enterprising Tabitha for the first time in a long, long while. We see why Jae-Hyun said what he did when she steps out in the late stages of pregnancy, telling us that while Jae-Hyun may be rather serious and stern in character, he is nevertheless deeply caring and protective of the woman he works for.

Abigail once again demonstrates her open affection for the people she forms connections with, being the first to greet Tabitha, immediately stepping forward to excitedly, but tenderly hug her friend who she hasn’t seen in ages. Tabitha tells her and the group that, while there are other mines here and there, she’s proud to say that hers is the source of most of the zinc that gets sent to the government. Hearing this and the way she discusses the state of things at this site she has taken responsibility for is impressive as hell, and another fine example of New Century continuously providing us with examples of inspiring women in positions of power who have a real aptitude for it. It’s also especially encouraging to learn that Tabitha has achieved all of this during her pregnancy. First, that’s an impressively short timescale for her to have set all this up. And second, I appreciate this story showing us a female character whose agency isn’t suddenly taken away once she’s pregnant. Tabitha had a goal in mind, and she was highly motivated to make it a reality; her pregnancy is obviously a big deal, and it will undoubtedly affect things moving forward, but it doesn’t change her drive or her capability, and that’s really cool to see.

We get set up with something akin to a sidequest, though it’s a sidequest that aligns with the group’s main journey as they set out for Wind Doors to study and interact with. Tabitha’s running low on people to secure this place, and the supply line has been interfered with by groups who either want to profit off the zinc, or otherwise just cause trouble and have their way. She’s called for help multiple times, but nothing’s come of it. Tabitha suggests she show the group the local Wind Door, and then they can move on to Jefferson to request a garrison for backup. The problem, however, is that while Tabitha and her group have held out up till now, she’s weeks, possibly even days away from giving birth, and the crew of SteamHeart aren’t planning on leaving her, particularly James, as the only doctor at hand. What with this being fiction, I’m inclined to agree that odds are Tabitha will go into labour right as the group comes under attack.

We move on to a section narrated by Jeremy; the group’s first encounter with a Wind Door. The journey of this sequence is powerful and compelling. Jeremy’s anticipation as he approaches a portal to another world, the manifestation of everything that drives him, is intensely felt as he describes the scene as if he were looking at the most beautiful painting. You get the impression that, even if he wasn’t recording his thoughts like this, this majestic scene of something singular and otherworldly being hidden in this obscure corner of the world would nevertheless be burned into his memory forever. The conversation about finding/making a ladder tall enough for someone to reach the portal makes it plain, however, that even if what would happen next did not occur, his dream of throwing himself at the portal and seeing what happens next was an impossibility. Jeremy chides himself for not thinking of bringing a ladder, but the truth is it would be unlikely for a 30 foot step-ladder to exist, making one would take time they don’t have, and, even if they did manage all of that, they still wouldn’t be able to chance someone inadvertently falling through the other side, presumably to their death, considering the height of the Wind Door. There’s too many factors at play which make the tantalising idea of touching this door to another world an impossibility. When Abigail begins to close the portal (looking absolutely striking as she does so with her billowing green coat and red hair as she channels her dormant powers, in an act that’s very akin to the most memorable Jean Grey moments), it pains Jeremy and the curious reader. The music combines with his narration to create a sense of something amazing happening, but at the cost of another amazing thing being taken out of this world forever. My favourite line is a simple one; as Abigail exclaims “I’m doing it!” with a great effort as she closes the portal, Matt Wardle’s delivery of Jeremy’s comment “And she really was” conveys the character’s recognition of his teammate’s achievement, and that, despite his disappointment at coming so close but falling short of his own goal, he is compassionate towards others and genuinely acknowledges what a feat Abigail is managing. The story near the beginning of SteamHeart in which the young Jeremy turns back home midway through his journey to a potentially wondrous sight for the sake of his friend told us that, for as much as Jeremy is intensely driven by his desire to see the magical and the indescribable, he does not put the safety and happiness of others before his own ambition. He demonstrates that again here, acknowledging the success that Abigail has achieved. Though it is hard not to feel some of his regret as he looks back at the site as they leave to get Tabitha back home, remembering the beautiful picture that was there a few moments ago, and now only seeing a place like any other. Its “out of date flag” shows just how forgotten by the world this place is, and how the Wind Door it once housed now has that same status of being a thing of the past.

So yeah, no time to celebrate the portal being closed and thereby proving that this mission is doable and their struggles aren’t all for nought – Tabitha’s gone into labour! Luckily a doctor is at hand with James present, which very nearly wasn’t the case before the team showed up. So, with any luck, this should all go relatively smoothly and without any interruption, right?

…anyway, the team return to the mine and set Tabitha up in her bedroom. Hours pass, and gradually the room is reduced to just Tabitha and James as they head into a long night together. Harry enters, and asks to speak with Tabitha alone. Before James leaves, however, she intercepts him to ask a question which catches him off-guard; will he and Abigail get married one day? I mean, it’s definitely a question that’s been on shippers, er, I mean readers and listeners’ minds, so I’m just glad someone came out and asked it straight out. This scene is relayed via James’ narration, and in addition to the answer he gives Harry, we also get a glimpse of what’s been on his mind – how Abigail closed the portal on her own while he could do nothing, reinforcing the impression James has of him being “surplus to requirement” next to Abigail when it comes to their shared endowment. The pragmatic James is finding it difficult to come to terms with his inability to contribute in any way to a task of such great importance, and the good doctor seems to feel so much responsibility, whether it’s for lives that could’ve been saved if he had made different decisions, or for his patients, or for the condition he has been given. What good is this ability if it does nothing but hinder his skills as a doctor? All of these thoughts make a prospective relationship with Abigail difficult for James to envision, so he tells Harry no, thinking that his response has disappointed her. But…hmm. I’m not so sure.

James leaves, and the role of narrator passes to Tabitha. She doesn’t have much of an idea what Harry would want with her, focusing on trying not to lash out when her next contraction comes around. Harry works her way to what she really wants to ask Tabitha, commenting on how she’s having this baby without a man around, how that’s not wrong and in fact really freaking brave, and finally tries to confirm her suspicions by asking Tabitha if she likes men, anticipating the answer to be no. The conversation that follows is sweet, wholesome, and just very healthy to hear. Tabitha plays the role of a really helpful schoolteacher – like, the kind of schoolteacher who should exist and should be teaching young people everywhere about the range of sexual orientations that exist and makes young developing people feel less awkward and less alone for feeling differently to heteronormative peers. Tabitha gently asks Harry if she’s feeling conflicted, not pushing her in any direction, but giving her the chance to air what’s been on her mind and in her heart.

We listen to Harry as she reasons out what she’s been feeling, thinking that she’s expected to land a husband, and, if that was to be the case, then James fit the bill pretty well as someone she respects and who exhibits many of the qualities she likes in people, such as kindness, intelligence, and politeness. But even with all that on paper, the key ingredient of buzzing attraction isn’t there for her, unlike how it is with… well, when the conversation turns towards Abigail, and her pre-existing relationship with Tabitha, it becomes clear who Harry really has a thing for. Tabitha confesses that she and Abigail “spent a little time together” when they last saw each other, which, okay, is a surprise! Not that they would get together for a bit, as the way Abigail talked with Tabitha and thought about her, you could certainly see an attraction there. I guess I just never put two and two together and figured out that they might already have hooked up (and that explains Abigail’s hushed comments earlier on in the episode when she says that if she’d had known Tabitha was pregnant when they met, she would have done…something, differently).

Anyway, Harry’s excited to hear Abigail likes boys and girls, and now says that yes, she really does have a crush on Abigail. Have I mentioned before that shipping can be so much fun in your favourite ongoing storylines with casts of lovable, fully formed characters? Well it is, and this is great, I love it. What I don’t love is the sad fact they go over next – that America’s current laws state that women aren’t allowed to marry other women. That, and the moment of tearful resignation Harry shows as she believes she can’t marry who she wants and must instead marry a man, are both heart-breaking. But fortunately, Tabitha is there to tell her that that’s not at all the case. In fact, there are other things she can do, either with herself or together with other women. Harry’s inquiring mind and aptitude for breaking difficult concepts down and understanding them as a series of mechanics drives her to ask Tabitha for guidance on being intimate with another person. A contraction comes at this moment, as Tabitha had expected, but instead of this making her hostile to Harry as she had feared it would, Harry holds her to support her through it, and when given an out when James comes back in to ask if she needs help, she reassures him and tells him to leave them alone for a little while longer. The music is calming as these two women talk, and we depart this scene, leaving the rest of the conversation to them as Tabitha continues to help Harry grow more comfortable with who she is and who she wants.

#The Inquisitive J#fiction#the new century multiverse#new century#new century multiverse#steampunk#alternate history#alternate universe#alternate history fiction#audio drama#fictional podcast#steamheart#the inquisitive j reviews

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

SteamHeart Episode 18 Reactions

Chapter Eighteen: Where Will You Be?

The full episode can be listened to here.

An episode of quiet introspection and softly spoken declarations of resolve.

After Abigail made her speech in the theatre to the people of Indianapolis, she spends part of her evening on top of SteamHeart, finding Annie had the same idea. The chapter more or less focuses entirely on this scene, taking the opportunity to delve into some of Annie’s thoughts on recent matters, and Abigail’s questions about the future. The action of Abigail sitting down so that they “tentatively rested our backs against each other” sets the tone. It makes this an intimate moment where the two may not necessarily see each other (suggesting that they don’t have as much of an understanding of one another as they will by the end of this conversation), but they nevertheless share enough trust that they can each have their back to the other person and let their guard down, despite their tentativeness indicating that this doesn’t come easily.

Annie initiates the conversation, commending Abigail on how she handled herself in front of the crowd. She notes the impression of humbleness Abigail gave off, as this is unusual for her. Abigail chalks it up to the stage enabling the performer in her, but Annie follows up on this remark by asking if that means she wasn’t really feeling humble as she said those things. This is the first of multiple points in the conversation where the two characters ask a searching question of the other, hoping to incite honest responses as the interviewee looks deep within herself. On this particular matter, however, Abigail, changes the subject, enquiring whether they’ll be departing Indianapolis tomorrow. Annie answers yes, as she believes the team is ready. Abigail takes her turn at a probing question as she asks if Annie feels she is ready. Like Abigail, Annie hesitates, not giving a definitive answer. It seems neither character has all the answers about how they feel.

Annie apologises for not being a better leader, which, you know, it’s been a little while, so it might be clearer to me where this is coming from on the re-listen, but I felt Annie was being a little hard on herself with this remark, though I do understand why she would hold herself up to high standards. Abigail however responds half-jokingly that she was ready to take the sheriff badge off of Annie herself. Annie starts to share, telling Abigail that the death of the Arlingtons brought into focus how responsible she is for all this. Suddenly the feeling of there always being someone back at high command is pulled out from under her, and it seems like, in practice, her word is where all the important decisions get made. That’s definitely a lot to take in for a mission this important, even for an officer with as much experience as Annie.

Abigail points out that the group and the country still has Truth and Katherine looking out for them. Even after conceding that, Annie worries about what will befall them if they lose Harry. She defies estimation – what Harry can create and invent is so valuable and beyond what other people can either imagine or bring into being, and that’s how Annie saw Thomas and Sarah. They both envisioned a future where humanity could survive into the new century and worked tirelessly to make that happen. Without people like that, people who weren’t just visionaries but actually had a decent idea how to make those visions into reality, Annie doesn’t have high hopes. Abigail argues that, while folks like Katherine aren’t “beyond genius”, that doesn’t stop them from being able to make a difference and contribute to that optimistic future coming to pass. She’s finally able to give Annie an answer and say that she meant what she said during the speech, or at the very least said “what I hope is true”. That’s enough to give Abigail fuel to keep trying to manage the hand she and the rest of the world have been dealt. And whether it’s from her own internal strength, talking this over with Abigail and hearing her words, or a combination of both, Annie resolves to focus not on whether the new higher ups can match up to the old, and instead look to her own status as a figure of authority and work on being a better leader.

Abigail echoes my sentiments from earlier and says that Annie shouldn’t hold herself to “beyond genius” levels of acumen. When Annie deflects this by asking what the consequences will be if she doesn’t shape up, Abigail tries a different approach by running the title question of the episode – where will you be? Specifically, when, or if they are successful in this mission and they survive into the next century, where does Annie want to be? Essentially, Abigail wants to know what Annie’s best case outcome of all of this is, and, more importantly, she wants Annie to know as well, because she suspects Annie hasn’t allowed herself to entertain the thought, and having it might just give her something to work towards.

The first thing she knows is that she wants to live in a future where she’s done killing people, and she holsters the gun which she had out, indicating her vigilance against the threat she’s constantly thinking about. After that, she has fun thinking about the possibility of pursuing her sewing, something which Abigail definitively says she won’t take part in due to her distaste for dresses (which she demonstrated in the run-up to the ball earlier on in SteamHeart). As for Butler, Annie wants him to be safe and done with the army as well, but she shares her worries that it might be difficult for him to give that up after being so adept at it for so long, something which Annie understands and seems to share. It’s not that they enjoy killing, but the pride they take in seeing through the many dangerous missions they’ve taken part in is compelling. Even after knowing each other so well, we see that there are some situations Annie and Butler can’t say with certainty they’d know how the other would act.

When Annie asks Abigail where she wants to be, she’s able to say with relative ease what she’d envision James wanting to do – take on Thomas’ position. However, she admits to having no idea what she wants, as this topic was a means to helping Annie be optimistic about the future. Abigail’s certainty in what the other half of her pairing would want to do and lack of certainty for herself is a contrast to Annie, who has more ease in saying where she’d like to be than she does with giving an answer on behalf of Butler, her partner. Duos and partners with singular bonds are a recurring theme in New Century, but moments like this demonstrate how different each pairing is. The suggestion of following Commander Wilson’s path and becoming an explorer holds some appeal, leading to Abigail listing off his numerous roles, including a spy, diplomat, geographer, and even translating the Karma Sutra, which, even in an alternate America that’s lived with the Wendigo for more than a decade, is causing quite the stir. But that kind of life is not quite what Abigail wants, and, speaking honestly, she admits that the future terrifies her. That’s something I’ve experienced at different points in my life – I vividly remember facing feelings of existential anxiety as a kid when I thought about the future as a concrete thing that I’d have to face one day. I’ve improved and more or less got over myself, but I’d be lying if I said those fears have entirely gone away.

Going back to Abigail, she brings up her desire to find her parents, the one vision of the future she still holds onto, even after so much time having passed since Secret Rooms. This prompts a conversation about whether this is for the best, as Annie argues that she’s chasing the past, fighting against a decision her parents made to safeguard her future. Abigail counters by voicing her own displeasure at having her life be decided for her, a part of her character which the Definitive Edition of Secret Rooms brought into focus. This hurts Annie, as Abigail is inadvertently suggesting that she wishes she led a life where she wouldn’t have met her or the rest of Team Steam. She doesn’t mean to imply she feels that way, but it’s understandably still upsetting to hear. Abigail states she’s “a painfully honest son of a bitch”, pointing out how the openness of conversations like this can be a positive experience with the potential to sooth recent sadness and provide a rekindled sense of optimism for the future, but it can also lead to feelings coming out in the open which hurt to hear, even if the person feeling them doesn’t intend them to. That isn’t necessarily a terrible thing, and can be part of the process of being more honest with one another, but it is something to be conscious of in heart-to-heart conversations like this. In this instance, it leads to the slightly inflamed (but admittedly kind of amusing) exchange of Annie calling Abigail a “stubborn red headed mule” and Abby calling her a “stuck-up murderous pixie” (which, upon reflection, is a harsh jab against a person who’s just shared her regret at leading a lifestyle where she has to kill people). Even so, the two can agree to Abigail wanting to take control by getting to the Wind Doors and hopefully make a difference, and Annie doing her best to help her get there. They get up as the conversation draws to a close, and as they head down below, Annie asks if she can borrow Abigail’s “Indian sex manual”, to which Abigail responds “I left my copy back in Washington” with an audible smirk on her face. It’s a funny, but oddly sweet way to end the exchange, as it’s both a moment of down-to-earth levity after a deep conversation, and one last piece of honesty shared between the two where Annie expresses an interest in the book, and Abigail admits to owning a copy.

Before we reach the credits, we hear Harry’s brief letter to Truth, which was sent from the Indianapolis Outpost, meaning she sent it before they would leave the next morning. Harry misses her sister and appreciates her kindness, but she doesn’t “need” to return home. Instead, she asserts that they are traveling on the road again today. This resuming of the journey has that much more weight behind it as a result of Harry deciding its time to move forward as SteamHeart’s mechanic and driver. And she does this “for mum and dad”. A short but powerful and emotional close to the episode.

The performances of Laureta Sela and Sharon Shaw are spot on in this episode. The chapter hinges entirely on Abigail and Annie’s conversation, and each voice actress conveys the earnestness and emotional weight of what’s being said. It’s not a moment of the story where emotions are exploding out in a climactic fashion, but are instead being softly explored in a quiet setting where each character assesses where they are and where they’re heading, and their performances make that compelling from beginning to end.

#The Inquisitive J#the new century multiverse#new century#new century multiverse#steamheart#fictional podcast#Alternate History fiction#Alternate History#steampunk#the inquisitive j reviews

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

SteamHeart Episode 17 Reactions

Chapter Seventeen: Winds of Virginia

There’s something quite affecting about this being the first chapter I tackle after an extended period away; I’ll try my best to explain why as we come to the chapter’s concluding moments and my closing thoughts, but for now, let’s go over the beats and discuss what stands out in this chapter.

The crew arrive at Indianapolis, still recovering after the news of the Arlingtons’ deaths. Butler reflects on the state of the city, providing some insight into how settlements like this leave vast portions of the city uninhabited due to the significantly diminished population, which is a contrast to how crowded Washington has become after the government re-established itself and civilians began flocking to the city. For those looking for a sense of security which the largest population and a seat of government can provide, it’s an attractive place to live in, but for those who can’t help but feel uneasy around people, particularly large crowds, it holds little appeal. The comparison between Indianapolis and Washington, as well as the discussion of the different attitudes people have towards the capital reinforce the impression that the Reunified States aren’t necessarily so unified; different pockets of civilisation showcase different attitudes towards the best means of survival, as well as different outlooks on the sort of life people want to live for as long as they are alive. It’s worldbuilding, and it’s worldbuilding that draws upon the very relatable idea of different people simply placing different value on human contact; some will need a lot of people around to feel safe, while others only feel safe when they are away from people.

So, Abigail (looking for any excuse to get out of SteamHeart for a bit and eager to do anything which will help take their minds off of things) suggests taking in a local show, and the rest of the team agrees. It’s not long after the play starts that they realise that it’s a dramatisation of the life of Katherine Holloway, James and Abigail’s former guardian and the newly appointed Director of the National Intelligence Agency. Specifically, this is retelling the parts of her life that she shared in her segment of The Cartographer’s Handbook. It’s set up to be accessible entertainment to appeal to the general crowds with two-dimensional and stereotyped depictions of James and Abigail (though “I like punching!” gets a laugh out of me each time I revisit the chapter) and clichéd lines like “Ms. Holloway, I’m supposed to ask YOU that! Ha!” *pause for laughter from the theatre audience*. It’s also clearly meant to be propaganda, espousing “the New American work ethic”, as well as the virtues exhibited in Katherine’s actions throughout this story which they wish to encourage in the people of America, such as her dedication, resistance against those who would take advantage of flourishing settlements, and her determination to keep fighting. By the end, all the parts which would make those who actually were there roll their eyes aren’t enough to put Team Steam off the play, as even the most cynical of their number concede they got something out of it. It’s fun to have a tongue-in-cheek riff of some of the events up to this point (and yes, there is a clear comparison to be made to a particular episode of a terrific TV show, as acknowledged in this chapter’s epilogue), but I find it especially refreshing that one of these joking looks at a piece of propaganda in a fictional setting comes away from it without being entirely dismissive. It’s important to be critical of over-dramatic entertainment with an agenda, but what is sometimes lost in these discussions, both in and out of fiction, is the ability for media, any media, to have genuinely positive and profound influence over people. Examine and consider the stories you engage with, but don’t disparage the people who take away commendable messages from them which don’t cause harm to others, or who find something legitimately meaningful to them, or those who just needed something to take them out of a dark place long enough that they could take their first steps back into normality.

Harry speaks for what seems to be the first time in ages, and she commends the Blushing Pilgrims for giving these people something which uplifts them. Her assessment that “The Cartographer’s Handbook… this new story… people like them” is a correct one, and I’m not just talking about within the narrative either. Harry tells us that this doesn’t mean she’s suddenly alright, but she’s nevertheless glad she saw this, continuing New Century’s trend of presenting well-observed depictions of grief and depression, and the steps we take to cope with them.

Harry asks if they can see it again the next night, and while tickets are selling out, Annie makes a point of telling the theatre staff that the real James Penrose and Abigail Grey will be in attendance, which makes getting tickets a lot easier. As a result, Abigail is asked to give a speech – a test of her developing skills as a high-ranking officer, Cartographer, and, now, highly visible public figure, all three of which demand the ability to inspire. As she speaks, Annie keeps a watchful eye out for potential threats, ruminating on the deaths of Hayes and the Arlingtons and resolving not to let the same thing come to pass with her most recent charge. Annie and Butler are some of the most capable soldiers and fighters in all of New Century, but witnessing these moments of redoubled determination and seeing that they are motivated by regret and self-doubt over whether they really did enough to prevent past losses shows their human vulnerability. It also stresses that the admirable qualities of these two characters aren’t a result of them always winning, but of how they find it in themselves to take their regret and shape it into something which helps their drive to succeed in the future. Annie doesn’t have it all figured out, but her approach to figuring it out is to identify what she can do and still has control over and focus her energy on that.

Back to Abigail’s speech – she discusses the assassination of the Arlingtons and the instructions of their replacement, Katherine Holloway. She reads out Katherine’s letter to the audience, showing some of the real-life strength of character of the woman who inspired this play as she acknowledges what has been lost, and affirms her intentions to work with Truth to ensure that what the Arlingtons were working towards will come to pass. After Abigail finishes relaying the words of her mentor figure, she starts to say her own thoughts as she speaks to the crowd. She makes a point of commending what these people are doing, and after the parts of the episode where she rolled her eyes at the blunt depiction of her character, the sincerity of her words illustrates the perspective and thoughtfulness she has developed over time. Her speech is positively received by the crowd, but, more importantly, it stirs something in Harry. It’s a testament to how much of a chord Abigail struck with the crowd and the person who most needed to hear those words, and it indicates that the fires of Harry’s spirit and creativity have been rekindled by the note of hope and resilience in Abigail’s speech.

We reach the chapter’s concluding moments as we transition to a few days later, and Harry is back in the driver’s seat. Seeing her return to her work and to the upkeep of SteamHeart is heartening, and hearing this wonderful mechanic’s process of returning to a kind of stable normality be described as attending to “much needed repairs” is a beautifully fitting phrase. As Annie watches Harry’s focus, she says the words which surprised me by how much they affected me; “[I] pondered my own return from inactivity. Was I moving now to meet one frightening scenario, or to get away from another?” At the time of writing this, I am coming back to writing on this blog of mine after my own period of “inactivity”. This year has not been without progress and personal accomplishments, but what has loomed over me for far too many months is an ineffable sense of uncertainty, inadequacy, and, at the worst of times, despair. I’ve felt out of balance. But little by little, I’ve tried to right myself, take back control, and regain a sense of who I am and what I want to be. As I consider the practical and mental challenges ahead of me, I can certainly say that there are frightening scenarios ahead of me. But like Annie, I can’t help but look at the last few months and feel as if I’m taking some steps away from the frightening scenario I so desperately wanted out of.

And that’s why this chapter meant as much as it did to me right now.

#The Inquisitive J#the new century multiverse#new century#new century multiverse#steamheart#fictional podcast#Alternate History fiction#steampunk#the inquisitive j reviews

0 notes

Text

Ray Harryhausen’s Sympathetic Portrayal of the Stop-motion Creature: The Clash of Stop-motion Fantasy Against Live-action Reality

The following was adapted from a presentation I gave at 2019 Doctoral College Conference held by the University of Surrey. It is part of a broader project on the history of US stop-motion and acts as a brief window into a chapter in progress on Ray Harryhausen and his films. The presentation was 10 minutes long with questions, and was intended for audiences who would be interested in the subject matter, but not necessarily be experts in the field of stop-motion, special effects, or even animation or film studies. This is a deviation from the film reviews and articles I do on this blog, but adapting parts of my academic research into smaller, digestible pieces like this is something I’d like to do more of in the future. So read, enjoy, and, by all means, provide feedback!

The man you see in the image above is Ray Harryhausen. I expect that name will be familiar to at least some of you if you are fans of classic US fantasy adventure films like Jason and the Argonauts or Clash of the Titans, as Ray Harryhausen was the animator who provided the special effects for not only these films, but thirteen other fantasy and sci-fi films ranging from the 1950s to the early 1980s. The action sequences of these features showcased live-action actors interacting with beasts, statuesque golems, and an assortment of supernatural creatures which Harryhausen would render through the medium of stop-motion. This method of animation involves a physical model being photographed one frame at a time as the animator manipulates the model to create incremental movements which come together to form coherent movement when projected on screen, with a contemporary example being Wallace & Gromit. Harryhausen would intersplice his stop-motion animation with live-action footage using a ‘split-screen rear-projection process’. The live-action component of the sequence would be filmed first, then projected onto a rear screen and the stop-motion animation would be shot in front of this screen. Harryhausen’s legacy of stop-motion animation makes him a key figure in any study of the history of both special effects and stop-motion, but his reputation extends not only to practitioners of these disciplines, but to the filmgoing public and to directors like Peter Jackson, James Cameron, and Guillermo del Toro.

Part of this can be attributed to the marketing of these films, which can be observed in these stills taken from the original trailer for the 1958 film The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. The trailer showcases sequences from the film which feature Harryhausen’s effects, repeatedly proclaiming ‘This is Dynamation!’, a term devised to distinguish Harryhausen’s stop-motion from more traditional forms of animation. The perception of these effects was important in the marketing for these films as features like this trailer indicate that this process of Dynamation wasn’t just implemented as a piece of technical trickery to be kept secret behind the curtain, but was proudly displayed as a means of drawing viewers in to watch these films. The Dynamation for these key action sequences is embedded in the perceived identity of these films. But if that is the case, what can be said about the identity of the stop-motion characters who are front and centre in these memorable sequences, Harryhausen’s assortment of Dynamation creatures? Having established how Harryhausen and his effects became so widely known, I propose that the status of these animated creatures as the main visual attraction for these films makes them not simply dangerous and repulsive monsters we want to see the heroes vanquish along their journeys, but rather presents them as fantastical creatures who audiences are encouraged to revel in the act of witnessing them; they are not repulsive, but attractive for viewers. Therefore, I’m going to suggest in my talk today that, for as dangerous as these creatures may be in the context of the narrative, there is an element at play in these films which allows for the possibility for audiences to become enamoured with these monsters, and even lament their passing when they are eventually defeated.

An element of this tragic component can be traced back to one of the most important influences on Harryhausen’s career as a stop-motion animator – Willis O’Brien, the special effects artist for such films as 1925’s The Lost World, and, most famously the original 1933 King Kong, which Harryhausen has repeatedly cited as the film that sparked his interest in stop-motion, eventually leading to him working under Willis O’Brien as an assistant animator on Mighty Joe Young in 1949. Harryhausen would evoke particularly iconic moments from King Kong, the film that had such an effect on him, in his own work.

In King Kong, there is a sequence in which the female lead, Ann, is captured by the native people of Skull Island and offered up to Kong as a sacrifice. Scenes with similar set-ups can be observed in Clash of the Titans and Sinbad and the Golden Voyage, in which the people of Joppa offer princess Andromeda to the Kraken and Margiana is presented as a sacrifice to the One-Eyed Centaur respectively. These scenes call to mind the recognisable imagery of the iconic first appearance of Kong in his original film, creating parallels between these creatures and Kong as each monster towers over a woman being offered to them as a sacrifice. This paints these monsters as imposing threats, but it also frames them as creatures who are revered within the narrative, encouraging the audience to also be taken aback by these creatures as they make their grand entrances.

With these associations with Kong being made, each film builds on this connection with King Kong by having these creatures share Kong’s fate. At the end of King Kong, the ape meets a tragic end as the planes shoot him down from the Empire State Building. It’s a memorably tragic conclusion to Kong’s tale as humans bring him out of his natural environment and place him in a man-made city in which he is so incompatible that it results in the death of this unique creature. In Clash of the Titans, Perseus arrives on the scene of Andromeda’s sacrifice and presents the Kraken with the head of the Medusa, turning it to stone whereupon the Kraken collapses under its own weight. The Kraken may not be visibly conflicted over inflicting harm on human characters (as opposed to Kong and his protectiveness over Ann), but much like how Kong was brought to New York in chains, the film twice shows the audience that the Kraken is kept in a cage by the Gods of Olympus, let loose only when it suits their purposes. The Kraken, a Titan who once ruled over the Earth before the Gods took over, is reduced to a prisoner, just as Kong was a king on Skull Island, but is brought to New York to entertain crowds. The Kraken is framed as being much less than he once was, before he is destroyed by the live-action human characters in the film.

After the Centaur carries Margiana away in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, he appears in the film’s climax assisting the film’s villain before being brought down by Sinbad as he repeatedly stabs him in the back. Despite being explicitly labelled as a ‘Guardian of Evil’ by the film’s dialogue, the Centaur does not harm Margiana, just as Kong does not harm Ann. Additionally, the animation of the Centaur’s death throes continue for some time, lingering on the creature’s pain as it gasps for air and unsuccessfully struggles to remove Sinbad’s dagger from the back of his shoulder before finally dying. Through Harryhausen establishing parallels between these creatures and Kong’s status as a revered and imposing beast, these similarly violent ends at the hands of the human characters has the potential to be read as the loss of something unique, and perhaps even a creature that has been mistreated and misused by the sentient humans and human-like Gods around them.

While the deaths of Harryhausen’s creatures should logically represent a victory for the live-action heroes of these films, there is nevertheless a heavy weight to the moment when these creatures cease to move, which encourages viewers to consider what has been lost. Now that I’ve established the connection between some of Harryhausen’s creatures and King Kong’s story, I’m going to examine how stop-motion contributes to the sense of loss in these scenes. The movement of stop-motion carries an inherent connection to the uncanny, a psychological phenomenon which is associated with that momentary unease we experience when we’re uncertain whether to register an object, person, or scenario as either familiar or unfamiliar, alive or dead. The physicality of stop-motion models gives them the appearance of puppets and dolls, and, as Paul Wells says, ‘the puppet is the embodiment of some degree of living spirit and energy but also inhuman and remote’. While the uncanny nature of stop-motion is an indication of a viewer being somewhat conscious of the puppet’s lifeless quality as an inanimate object in the real world, it simultaneously indicates the audience’s recognition of the life-like qualities of the puppet’s performance. However, in these moments where Harryhausen’s creatures cease to move, that tension between life and the absence of life ceases to be, marking a clear distinction from when the creature appeared to be active, albeit in an uncanny fashion, and its deathly inertness. Once they stop moving, the uncanniness dissipates, making the shift in how we perceive the character or creature being rendered in stop-motion that much more pronounced. The death scenes for each of Harryhausen’s creatures carry that much more impact because the uncanniness of stop-motion makes us aware of what life is being instilled in these physical models while they are alive in the context of the narrative.

The final shot of 1953’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms focuses not on the human characters, but on the death of the Rhedosaurus. As the silhouette of its body is cast against the flames, the film calls to mind the destruction caused by this creature, and yet its motionless body contrasts against the flickering flames, emphasising its lifelessness even further. Earlier in the film, a professor expresses wonder at seeing the Rhedosaurus. Even though his fascination with the creature results in his death, the acknowledgement of this perspective that the Rhedosaurus is a source of amazement recognises the fantastic spectacle of this creature – that the camera’s gaze in the film’s final moments rests not on the human characters but on the Rhedosaurus is an indication of how invested the audience is expected to be in this creature’s ultimate fate. The lingering shot of its inert body invites the possibility that its death is indeed lamentable.

Harryhausen’s Dynamation creatures are embedded in the history of US special effects cinema, and yet in the discussion of the relationship between narrative and US stop-motion, they occupy a curious space. It could be argued that they merely serve as a vehicle for the action sequences for these films, and that they aren’t meaningfully characterised. But I hope I have successfully presented the possibility today that, as the main source of attraction and the most enduring element of these films, the Harryhausen creatures engender a sense of fantastical wonder to them which, when paired with allusions to the imposing and tragic qualities of King Kong’s character and story, as well as the impact of seeing a stop-motion model suddenly become inert and entirely lifeless, has the capacity to instil feelings of regret at the lamentable loss of these unique creatures in the world of these narratives.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spiderman: Far From Home – A Movie Review

After an animated masterpiece gave us what many consider to be the new best Spider-Man film, and after a monumental finale to a developing narrative that was twenty-two movies in the making, what hope does a sequel to Spider-Man: Homecoming, a movie praised by many but seen by others as not much more than just middle-of-the-road, have of satisfying an audience who have been especially well catered for when it comes to superhero movies connected to the man who does whatever a spider can?

Well, it turns out it’s got a pretty good shot, because I got a lot more out of Spider-Man: Far from Home than I ever expected I would.

Jon Watts returns from Spider-Man: Homecoming as the director for its sequel, and with that comes a cemented sense of identity, as Far from Home takes the praiseworthy parts of Homecoming’s personality and places even more emphasis on those elements. The aesthetic for the Home series isn’t as palpably noticeable as something like Guardians of the Galaxy or Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarok, but it nevertheless maintains a consistent tone with the previous film which makes this particular perspective of the MCU feel lived in. There’s a charmingly grounded feel to how characters will engage in idle conversation about certain major events from other MCU films in a way that jokingly downplays moments or story beats that were presented with heart-wrenching gravitas in other films. It’s amusing for invested audience members, but it’s also an effective method of reminding you that this world is inhabited by a population who are routinely affected by world-spanning comic book shenanigans, but don’t have the advantage of hearing first hand what the hell is going on. As such, developments like Captain America going on the run become background news that gym teachers are only semi-aware of in the previous film, and, in Far From Home, the “blip” that erased half the population then brought them back 5 years later is just another thing that people have grown to live with. The film even feels comfortable enough to use it for comedic effect when one of the characters uses the blip to put Flash in his place when he’s being insufferable, and that is so endearing. As a result, while the visual aesthetics of these MCU Spider-Man films may not be as immediately striking or distinctive as other branches of this franchise, they provide a consistent tone of down-to-earth sincerity and people just getting on with their lives that makes them really pleasant experiences.

And while last year’s Ant-Man and the Wasp was an enjoyably sprightly heist movie which nevertheless felt out of place and too rushed out after we were still reeling from the weighty punch of Infinity War, Far from Home not only improves on its namesake predecessor, but also acts as a remarkably suitable follow-up to Endgame. The sombreness of Endgame’s first half and the epic scale of its second half are contrasted by the everyday levity and more personal stakes shown in this film. The action is inventive and varied enough that you’re interested to see how Spider-Man deals with foes we’re not used to seeing cinematic depictions of him fight against (elemental and… other, more spoiler-y threats), in environments that are labelled as ‘far from home’, outside of his typical comfort zone of New York. The comedy works because of a comforting sense of cohesion to the characters which make them work well together, and yet the dialogue is natural and flexible enough that you always see the individual traits of each character shine through. With a diverse cast of commendable talents like this, that’s a treat.

But while the film is a remarkably appreciated light-hearted palate cleanser, that doesn’t mean it’s pulling its punches with its heavier dramatic moments. This film deals with a teenager who watched someone he looked up to die in front of his eyes, and is now confronted with a world filled with iconography and heated discussion about that idol, and some of that fervent conversation is even directed at him as everyone asks if he will be the person to step up and take the place of his hero. It’s an emotional state that makes you feel so much for Peter, especially as Tom Holland has gone from strength to strength and solidifies himself as the definitive version of a young Peter Parker in my eyes. He’s killing it in this, selling the subtle balance between Peter having some newfound confidence to be able to stand up for himself and make his own decisions about what he wants and who he is, while also being racked with guilt, expressing uncertainty of the world of large-scale superheroics that he’s had a taste of but isn’t sure he wants to go back to, and retrospectively questions his own actions. A subtle detail in the film that does a lot to convey Peter’s current state of mind is his spidey-sense (Peter-tingle) not being quite as sharp as we might expect it to be – Peter is having trouble trusting his instincts. This, and his general anxiety over where he’s heading and his fears of the past are masterfully represented in one reality-bending sequence which shows some of the darkest imagery Marvel has ever put in their films as it puts all of Peter’s inner turmoil and doubts up onto the screen.

SPOILERS IN NEXT PARAGRAPH

But what works especially well in this film for me is how it creates these brilliant parallels to the first Iron Man to commendable effect. Both films feature ceremonies near their opening in which the hero is expected to attend and someone close to them criticises them for not quite presenting themselves correctly (if at all), as well as protagonists who question how the legacy that’s been left to them should be best used, villains who seek to use that legacy and the technology of Tony Stark for their own selfish ends (and both villains use the distraction of a more immediate seeming threat to disguise their manipulations behind the scenes), before concluding with the heroes having their secret identity revealed to the world. And of course, both feature tech-savvy geniuses working on their superhero suit in a holographic workshop while ACDC music plays, and the only thing I love more than that unspoken “this kid has everything in him that made Tony Stark great without him realising it” moment is Peter saying “Oh I love Led Zeppelin”. These parallels allow for a neat bookend of this whole arc of the MCU with Iron Man starting us off while Far from Home brings it, well, home. But they also reinforce the main theme of Peter’s emotional journey as he asks himself if he can, or should be the next Iron Man. The answer, as Happy tells us, is that no one could live up to Tony Stark, not even Tony. Peter doesn’t need to worry about being the next version of someone else, but the first version of himself. The film uses these connections between his character and Tony’s, between Far from Home and Iron Man to show us that we can move forward with confidence as we establish our own identity and take the parts of the people who inspire us along with us. Far from Home echoes a lot of the characteristics of Iron Man but ends up being something new, and it is exactly in that way that Peter ends up honouring Tony’s memory while still moving forward by the end of the film.

There’s a lot at play which could have stacked the deck against this film being a critical success; between the explosion of artistic creativity on display in last year’s singular Into the Spider-Verse, and Endgame’s entanglement with gargantuan levels of audience investment allowing for once-in-a-lifetime emotional payoff, I expected for a long time that Far From Home would be unfavourably compared to these two relatively recent blockbuster triumphs. But it was exactly the film I needed for this series after Endgame, and full kudos to the showrunners, I wasn’t anticipating that. It’s packed with youthful sincerity, delivers an adventure with scaled back yet more personal stakes which makes the whole thing feel that much more meaningful, and while I enjoyed seeing the kids in their own environment in the school in the last one, the trip through Europe makes it an enjoyable journey. The more time passes, the more I appreciate about what it achieves under the surface with its character development, inspired connection with other films in the series, and its ability to capture the experience of trying to find your way.

Final Ranking: Silver.

When all the threads of the MCU have been tied up by Endgame, who better than a spider to start weaving the first strands of the next web.

#The Inquisitive J#film#movies#film reviews#movie reviews#critic#criticism#film critic#marvel#mcu#spider-man#spider-man far from home#spider-man far from home review#far from home#far from home review#the inquisitive j reviews

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Avengers: Endgame’ – A Movie Review, and a Reflection on Endings

Endings are rarely the definitive final word.

A person’s story can come to an end, but the stories of the people around them and the world they live in carry on, even if that one person isn’t there anymore. That realisation conjures up a whole tangled mess of emotions, but it is the natural way of things. It’s not right to want everything to end with you. In life, we make the most of the time and energy we’re given, and if you make enough right decisions, get lucky, and dedicate enough of yourself, you’ll hopefully get to go with the sense that you did okay, and that those you leave behind are going to be alright. Endings in fiction are as infinitely variable as any other feature of artistic expression, but in narratives with expansive casts or fleshed out worlds, they often leave us with the feeling that we’d only have to stay a little longer and there would be more stories to explore. Just as the real world is bigger than any one lifetime, successfully-established fictional worlds feel much larger than any one set of characters and their narrative.

For the last eleven years, audiences have enjoyed a series of blockbusters featuring an impressively varied range of stylistic approaches. At their best, these films are deeply satisfying and affecting, delivering poignant moments about characters coming to terms with their own flaws and trying their best to do the right thing. But when considered together, these films have never entirely felt resolved, with each one going out on a lingering note of “just wait for what comes next”. The story was never over for the Marvel Cinematic Universe, because another film was never far away. And now that the grand conclusion has finally come and $2.5 billion worth of us have watched and re-watched it, things are just the same as ever, and yet we’re at a moment that we’ve never seen before and are unlikely to see again for a long time. We’ve reached an ending of the story that begun with Tony Stark and his box of scraps in that cave in 2008. The story is over. But there are more stories to come.

Yes, there will be spoilers ahead. But I say again: this film has crossed over the two and a half billion dollar mark. I’m pretty sure if you’re reading this, you’ll have contributed your drop or two to Marvel’s bucket. So let’s talk about the movie.

I appreciate the efforts of Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely as screenwriters, Joe and Anthony Russo as directors, and the input of every person involved in deciding the final shape of Endgame’s story to make its structure noticeably different to that of Infinity War. The previous Avengers film is a constant juggling act, relying on the viewer taking to Thanos as a central thread around which the rest of the film is hung. We’re either seeing the various steps Thanos is taking along his journey, hearing about what kind of man he is and what he intends to do, or seeing characters who are consistently on the back foot as they frantically scramble to strategically and mentally prepare for an opponent they’re not ready for. By this point in the series, we’ve been conditioned to expect to see things primarily from the point of view of the dozens of characters aligned with the Avengers, but Infinity War is messy and fractured when you look at it from the perspective of the heroes. And that’s the point – our heroes are fractured, and so there’s no unified effort against the villain as he single-mindedly pursues his goal with continuous success. The Avengers are a mess, and they lose. Thanos is the one who seizes control of the narrative, undoing the decisions and sacrifices made by the heroes as he dictates what his ambitions are and why they are so noble… and because viewers are susceptible to sympathising with the person who names themselves the hero and takes the reins of the narrative, far too many people bought Thanos’ rhetoric. For a year there, we really were seeing think-pieces that said “maybe the genocidal zealot who emotionally manipulates people is right”!

But Endgame’s structure deliberately contrasts against Infinity War’s. Whereas Infinity War is about heroes being separated and the catastrophe that follows in the wake of this disunity, Endgame presents its heroes as a group of grieving people who are unified through their shared regrets and resolve to overcome their despair together and work towards a singular objective to try and fix everything. The Avengers are disassembled in Infinity War and reassembled in Endgame. As a result, the structure is comparatively more uniform. You can clearly differentiate the film into three distinct thirds – the five-year time skip that shows life on a mournful Earth still coming to terms with half of life being eradicated, the Back to the Future Part II time-travel mission as characters revisit scenarios from previous films, and the big blowout battle where every surviving main superpowered character in the entire franchise is dumped into one battle for your viewing pleasure. Each third offers something different, meaning you cover all of the ground that you’d want to in a dramatic, energetic, and emotional close to a blockbuster saga with literally dozens of characters who are all key players. Each third is impressively balanced, and they all act as strong supporting columns for the film as a result.