Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Through The Fire

I look in your eyes and I can see

We've loved so dangerously

You're not trusting your heart to anyone

You tell me you're gonna play it smart

We're through before we start

But I believe that we've only just begun

When it's this good, there's no saying no

I want you so, I'm ready to go

Through the fire, to the limit, to the wall

For a chance to be with you

I'd gladly risk it all

Through the fire

Through whatever, come what may

For a chance at loving you

I'd take it all the way

Right down to the wire

Even through the fire

I know you're afraid of what you feel

You still need time to heal

And I can help if you'll only let me try

You touched me and something in me knew

What I could have with you

Now I'm not ready to kiss that dream goodbye

When it's this sweet, there's no saying no

I need you so, I'm ready to go

Through the fire, to the limit, to the wall

For a chance to be with you

I'd gladly risk it all

Through the fire

Through whatever, come what may

For a chance at loving you

I'd take it all the way

Right down to the wire

Even through the fire

♪

Through the test of time

Through the fire, to the limit, to the wall

For the chance to be with you

I'd gladly risk it all

Through the fire

Through whatever, come what may

For a chance at loving you

I'd take it all the way

Right down to the wire

Even through the fire

To the wire, to the limit (through the fire)

Through the fire, through whatever

Through the fire, to the limit

Through the fire, through whatever

Through the fire, to the limit

Through the fire, through whatever

Through the fire, to the limit

Through the fire, through whatever

Through the fire, to the limit

Through the fire, through whatever

Through the fire, to the limit

Through the fire, through whatever

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Dual-Function Aerator Faucet

0 notes

Photo

The Best Baguettes in Paris

0 notes

Photo

How Does The Room Sound Right Now

Thousands of books have been written attempting to point people to the difference between mindfulness and “paying attention” as we normally do. I’ve read a lot of these books, and even written a few.

There are simpler ways to get at the concept though.

If you want to grasp what is usually meant by the word mindfulness*, all you need to do is to find the answer to a simple question: how does the room sound right now?

By “the room” I really just mean wherever you are. You could be in a room, or outside, or in a stadium, in a cave, scuba diving among coral reefs, whatever. The point is there’s always something to hear, wherever you are.

If you wanted to know how the room sounds, how would you get the answer to that question?

Well, you’d listen to it.

Try it now. Find out how the room sounds. Take a good twenty seconds to inquire, by listening.

So how does it sound?

You might say, “Well I hear the laptop fan whirring, I hear a large vehicle rumbling around out there, maybe a garbage truck. There are some distant voices, and also some pigeons warbling out on the eavestrough. I can even hear my breath escaping my nose at times.”

That’s not really the answer to the question though. It’s a description of the answer. The answer was how the room sounded — what you heard when you listened. A description like this doesn’t convey any real knowledge of how the room sounds, just as a description of a sunset will never transfix a crowd of people, and a description of your housekey doesn’t let you into the house.

The answer to the question of how the room sounds can be always be found, immediately — and only — by listening. The room begins telling you how it sounds the moment you inquire.

As soon as you stop listening and start doing something else — putting descriptive words to your experience of listening, picturing garbage trucks, pondering the amount of birdshit on your shingles — you’re no longer inquiring into the “how it sounds” question. Instead you’re doing tangential tasks (interpreting, describing, etc) which do not deliver the answer.

This is not some Mister Miyagi spiritual mumbo jumbo. I am pointing you to a simple distinction here, between (a) how a room sounds, and (b) how you might describe or interpret those sounds.

Mindfulness is our innate capacity to inquire into question (a), and similar questions about direct experience.

You can access this ability at any moment of your life by finding the answer to “How does the room sound right now?”

Of course, you can apply this same sort of inquiry with the other senses, using different questions.

How does it look when I close my eyes right now?

How does my body feel right now?

What do I taste right now?

Again, complete answers are available just by inquiring. You already have the capacity. You don’t even need to verbalize the questions after a while, you can just start inquiring about the answer.

Note that whatever experiences you witness this way do not contain any words. You don’t taste the words “oak” or “dark fruit” in the wine. Direct experience comes in the form of ineffable sense phenomena, not verbal data. You can come up with some words later and refer to your experience with them — “the strawberry was tart and a bit fibrous,” but the taste itself is devoid of words.

By the time you’re mucking about with words you’re no longer inquiring. In that case, all you need to do is go back to inquiring.

You can inquire this way with any experience, great or small. You can get quite specific with your inquiry:

“How does it feel to rest my hand on my knee?”

“How does that droning noise in the background sound?”

Or you can get more general:

“What am I experiencing right now?”

Detail reveals itself gradually as you sustain your inquiry. What you might have regarded initially as “total darkness” behind your closed eyes, might come to seem more like “a field of shimmering pixely things making dark, mottled patterns.” Of course, this description isn’t the answer, the answer is the ineffable field of pixels itself.

As far as I can tell, everything is infinitely detailed like this. Look long enough, and even something simple like “darkness” is more complex than you thought. Sounds contain subtle waverings and oscillations, layers and undertones. The taste of chocolate contains, surprisingly, both pleasant and unpleasant qualities. Pain is not as solid or objectionable as you thought.

If you play around with this sort of direct inquiry, you’ll quickly notice that the answer to question (a), whichever one you ask, is never quite what you expect. You sort of know how the office is going to sound when you listen, but it never quite matches your expectations when you do. There’s always some surprising element.

So if mindfulness is this simple thing we can all do already, why do people meditate for hours and weeks and years?

The short answer is that you can stabilize and refine this ability to inquire to profound degrees, and that takes a lot of inquiring time. You can get very good at staying with the direct experience of a thing (i.e. the answer to question (a)) and get less distracted by your natural reflex to dive into question (b) in its many forms. You can learn all sorts of tricks for inquiring into experiences you didn’t even notice you were having.

If you do a lot of inquiry, there are also a lot of downstream implications to sort through, from all the extra detail that’s revealed. For example, you notice sooner or later that there’s really nothing that cannot be inquired into in this way. In other words, there’s nothing you can detect about yourself aside from your experiences. So who’s doing the inquiring, anyway?

Also, what is this experience of wanting a thing? How does it actually feel? What do you notice about the moment when a given instance of “wanting” appears? When you get the thing you want, what happens to the wanting?

What about when something feels really bad — what happens when you inquire into the the “badness” itself? What would happen you got more interested in what that bad feeling is like than in making it go away?

You can untangle a lot of personal problems through inquiry, by looking right at the experiences that make them up. Oh — embarrassment is just this passing gross feeling in my chest that makes me want to indulge in rehashing other embarrassing moments? Maybe I don’t need to avoid it like death.

Fascinating stuff, for some people. If this stuff sounds esoteric or boring to you, don’t worry about it. Just try asking and answering the basic (a) question, starting with how the room sounds. Then try it for other things. How does it feel to hold this cup? How does this coffee taste?

Inquire into the real answers to those questions, for ten or twenty seconds here and there throughout the day. You will definitely discover something unexpected.

#how does the room sound right now#sound#mindfulness#meditation#david at raptitude#listening#hearing

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Book of Cocktail Ratios | Michael Ruhlman

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Abstraction White Rose, 1927 | Georgia O’Keeffe

When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world for the moment.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In the spirit of keeping the beauty brought into the world by those we loved...

Rosa’s Mud Cake

Rosa Ewing Goldman, the mother of my dearest friend from childhood, passed away last week. I’ve written about her a lot over the years because Rosa was the first great cook I ever knew. She was the first person I ever knew who took pride in ambitious home-cooked food, making special trips to the Bronx’s Arthur Avenue from our sleepy suburb to get just the right bread or homemade pastas and mozzarella. She had a large well-worn wooden recipe box on her kitchen counter that was overstuffed with yellowed handwritten recipe cards and clippings from The New York Times. And I was the lucky beneficiary of so many of those recipes: Her creamy spaghetti with prosciutto and peas, her Shepherd’s pie which was always a leftovers score, a lentil salad made with tarragon vinegar, a garlic and gruyere dip that she always served in a little glass jar. Loyal readers, though, most likely know her as Rosa behind Rosa’s Mud Cake, a recipe she used to make for Jeni’s birthday (her daughter, my friend) and a dessert that I make for almost every celebratory occasion, toasting Rosa always with my first forkful. It was the first recipe I knew I wanted to include in How to Celebrate Everything and it always makes me so happy to hear when people out there who don’t even know her are thinking of her — however peripherally — when they bake that cake. If you have an occasion that calls for a rich, chocolatey super easy treat this week (or whenever!), please do yourself a favor and bake this cake. And please think of Rosa when you do so. Thank you.

Rosa’s Mud Cake

Don’t be concerned about the cup of coffee. It gives it a deep rich color and flavor, but it does not make the cake taste like mocha. Makes one 9×13 sheet cake or two 9-inch layers.

1 1/4 cups flour 2 cups sugar 3/4 cups cocoa 2 teaspoons baking soda 1 teaspoon baking powder 2 large eggs 1 cup strong black coffee (brewed, not grinds) 1 cup buttermilk 1/2 cup canola or vegetable oil 1 tsp vanilla extract

Mix all the ingredients in a bowl, mix, and pour the batter into two 9-inch round baking pans (or a sheet pan) that have been buttered and lightly floured. (The lightly floured is important!) Bake at 350°F for 30-33 minutes or until a toothpick inserted into the middle comes out clean. Let pans cool on a rack for 20 minutes, then gently run a serrated knife along the edges to loosen it. Invert each cake very carefully (it’s a delicate cake) onto a plate or another rack. Frost, if desired, though it’s just as delicious plain with a scoop of vanilla ice cream.

Also Very Easy Classic Chocolate Frosting (makes 1 1/4 cups) (This is not Rosa’s recipe.)

1/2 cup (1 stick) unsalted butter, at room temperature 1 1/2 cups powdered sugar 2 ounces unsweetened chocolate, melted and cooled 1 tablespoon whole milk 1/2 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, beat together the butter and powdered sugar on medium speed until light and fluffy, 2 to 3 minutes. Reduce the speed to low and beat in the chocolate, milk, and vanilla until the mixture reaches a spreadable consistency, about 1 to 2 minutes.

#jenny rosenstrach#rosa#food#friendship#mother#generosity#sharing#childhood#jeni#Rosa Ewing Goldman#loss#love#mom#doris#dede

1 note

·

View note

Photo

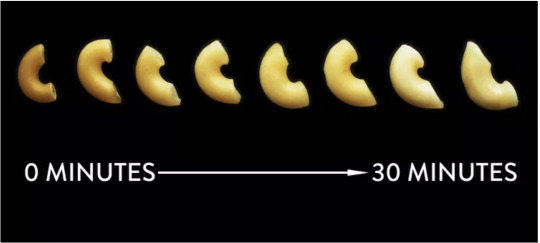

Pre-Soaking Pasta

If you leave uncooked pasta in lukewarm water for long enough, it'll absorb just as much water as boiled pasta.

After about 30 minutes, it had taken in just as much water as a piece of cooked boiled macaroni, all while remaining completely raw!

While the ability to cook presoaked pasta in just 60 seconds in itself is not all that exciting for a home cook (all it does is convert an eight-minute cooking process into a 30-minute soak plus one-minute cooking process—hardly a time-saver), it's a very interesting application for restaurant cooks, who can have soaked pasta ready to be cooked in no time.

But what it does mean for a home cook is this: Any time you are planning on baking pasta in a casserole, there is no need to precook it. All you have to do is soak it while you make your sauce, then combine the two and bake. Since the pasta's already hydrated, it won't rob your sauce of liquid, and the heat from the oven is more than enough to cook it while the casserole bakes. If you taste them side by side, you can't tell the difference between precooked pasta and simply soaked pasta. Think of what this means for lasagna! I know of at least six different common dental procedures that I'd rather have performed than to have to par-cook lasagna noodles.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

See’s Chocolate Caramel Lollypops

Auntie would have me ordering cases of these.....feeling her presence still.

Apparently Auntie is still hanging with Ronna and Mike. En route JFK to p/u Lucie (same day) WFUV plays “Diamonds on the Soles of her Shoes,” and then before bed, the NYT crossword clue is “__________________ retriever.” What are the chances.....

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

BirdSong

Birds are a way to connect with nature, which is associated with better body and brain health, research shows

Looking to improve your mental health? Pay attention to birds.

Two studies published last year in Scientific Reports said that seeing or hearing birds could be good for our mental well-being.

0 notes

Photo

Moms | Thoughts on Grace

Only as the Day Is Long

Soon she will be no more than a passing thought, a pang, a timpani of wind in the chimes, bent spoons hung from the eaves on a first night in a new house on a street where no dog sings, no cat visits a neighbor cat in the middle of the street, winding and rubbing fur against fur, throwing sparks. Her atoms are out there, circling the earth, minus her happiness, minus her grief, only her body’s water atoms, her hair and bone and teeth atoms, her fleshy atoms, her boozy atoms, her saltines and cheese and tea, but not her piano concerto atoms, her atoms of laughter and cruelty, her atoms of lies and lilies along the driveway and her slippers, Lord her slippers, where are they now? from Only as the Day Is Long (Norton, 2019)

I started writing a separate essay a day or so ago (on a poem from Hannah Emerson’s The Kissing of Kissing, which I can’t wait to share with you next week), but then the book today’s poem is from — Dorianne Laux’s Only as the Day Is Long — was sitting atop the tall pile of books that do not fit on the tiny bookshelf I keep filled with poetry next to my chair, and I flipped through the many dog-eared pages that mark this collection, because I dog-ear many pages that I love, and because I love many poems by Dorianne Laux, and I stopped to read this one, and I remembered reading its last line — Lord her slippers, where are they now? — a long time ago, and how it made me think of a story about my own mother that I will tell you later, and now I am writing about this poem today, because I love this poem, and because it grieves the loss of a mother, and because it makes me think of a mother-figure I have lost, and it makes me think of my own mother, who is alive and beautiful.

Many of the poems in the final section of Laux’s book speak toward the death of Laux’s mother, who was a figure, one can glean, of deep complexity, full not just of — as Laux’s poem “Death of the Mother” attests — a “lust for order” or “tyrannies / of despair,” but also of a “cavernous heart.” That poem ends with these lines:

You taught us how to glean the good from anything, pardon anyone, even you, awash as we are in your blood.

Maybe this is why I love Laux’s poetry so much. It is full of grace. It understands, I think, the bound-ness of this life, the fact of our frailty, and how our frailty begs for us to be loved whole, to be forgiven as often as we can for our failings and our inconsistencies — these, too, being facts of our frailty. Her poetry reaches almost always through complexity toward goodness, and sings a music out of the deep, unending sorrow that makes itself known alongside such goodness. Laux’s poem, “Cello” — one of my favorite poems ever written — illustrates this sense of compassionate dependence perfectly:

When a dead tree falls in a forest it often falls into the arms of a living tree. The dead, thus embraced, rasp in wind, slowly carving a niche in the living branch, sheering away the rough outer flesh, revealing the pinkish, yellowish, feverish inner bark. For years the dead tree rubs its fallen body against the living, building its dead music, making its raw mark, wearing the tough bough down, moaning in wind, the deep rosined bow sound of the living shouldering the dead.

There it is, in those final lines — perhaps the most apt depiction of the rough music and magic of life: the deep / rosined bow sound of the living / shouldering the dead.

Laux does this magical work again in the first line-spanning sentence of her poem, “Mother’s Day,” a sentence that — in one single, elongated, musical moment — spans an entire life and fills it with images at once near-divine and ordinary:

I passed through the narrow hills of my mother's hips one cold morning and never looked back, until now, clipping her tough toenails, sitting on the bed's edge combing out the tuft of hair at the crown where it ratted up while she slept, her thumbs locked into her fists, a gesture as old as she is, her blanched knees fallen together beneath a blue nightgown.

Here one can both see and feel a human enactment of the image of the two trees from Laux’s “Cello.” The aging mother falling into the arms of her daughter, who has not just returned from some long journey to take care of her mother, but who — because of love — also in some ways never left.

And so yes, it is true, I am thinking of mothers today. I am thinking of mothers and mothering. I am thinking of the word mother as both verb and noun. I am thinking of my own mother, and I am thinking of those who have mothered me who are not my mother, and I am thinking of the deep complexity of the very idea of motherhood, the bright glossy paint it is often covered with by our culture, this brightness that hides the pain and loss and near-constant-carrying that must be part of its heart.

Laux’s story illustrates that carrying. In a long-ago-published portfolio of poems, part of her bio reads:

Between the ages of 18 and 30 [Laux] worked as a gas station manager, sanatorium cook, maid, and donut holer. A single mother, she took occasional classes and poetry workshops at the local junior college, writing poems during shift breaks. In 1983 she moved to Berkeley, California where she began writing in earnest. Supported by scholarships and grants, she returned to school when her daughter Tristem was 9, and was graduated with honors from Mills College in the Spring of 1988 with a B.A. Degree in English.

It goes without saying that Laux lived a life so much more difficult than it ever had to be because of the simple fact that she was a mother — that, given her choice to care, she was made to work. And it goes without saying that our current culture makes it hard either to be a mother or to choose not to be one. I think of how marriage has been, for me, a gateway to questions of subsequent parenting. For my wife, I know, the questions are all the more numerous. Motherhood seems so often like a light-filled, airy expectation that, once chosen, can then become unsupported. If it isn’t chosen, there seems so often to be so little understanding of why someone might make such a choice. Either way, a supreme loneliness must ensue. This is a tragic thing.

I am thinking of a moment in Mike Mills’s film C’mon C’mon when Johnny, lingering at his sister’s desk, — his sister, who is at once a mother, and a sister, and a daughter, and a wife — picks up a book by Jacqueline Rose, and we hear aloud these lines:

Motherhood is the place in our culture where we lodge, or rather bury, the reality of our own conflicts, of what it means to be fully human…What are we doing to mothers when we expect them to carry the burden of everything that is hardest to contemplate about our society and ourselves? Mothers cannot help but be in touch with the most difficult aspects of any fully lived life.

The film not only illustrates the beauty (and sometimes messy though well-intentioned inconsistency) that can arise when compassionate care is shouldered from mothers, but it also illustrates how hard such a task is and how much there is to communicate. It wonders aloud how much care people are actually capable of caring, but, in doing so, it portrays an extended, at times gorgeous moment when care is reimagined and shared. I love this film dearly. Just looking at these stills moves me almost to tears.

And so, when I read Laux’s poem today, I feel her enacting the attempt to capture the so-much-ness of her mother’s presence — which was, as mentioned before, a complex presence, a presence of both “laughter and cruelty” — and how, in moments such as these, when faced with the largeness of mystery, we linger on litanies of the ordinary: the “bent spoons,” a “timpani of wind,” the no-longer-sound of a “piano concerto,” and yes, too, the “slippers.”

I read this focus on the ordinary as a mark of Laux’s care for mystery as a poet. I feel in Laux’s poem a recognition of her mother’s indescribability, of the fact that the real atoms of Laux’s pen-or-key-strokes are not enough to bring back the fullness of her mother, the grief and happiness and love and cruelty and care that makes up a soul that must bear so much. The final, stunning question — Lord her slippers, where are they now? — moves me so deeply, because it captures the reality of loss when the person who has been lost is incapable of being even remotely reimagined as living again — so fully and so deeply had they been alive.

That question makes me think of my own mother. It makes me remember my grandmother’s funeral from almost ten years ago, and how my mother, divorced from my father and having long since seen her mother-in-law, arrived at the funeral home just after they had closed my grandmother’s coffin. She asked the funeral directors if she could pay her respects, and they let her. They opened the coffin and let her see my grandmother. Telling me the story later, my mother told me how glad she was that my grandmother — a tiny woman in death, maybe just over four and a half feet tall — was wearing a sweater, though she lamented the thinness of it. I wanted to cry, hearing my mother’s story, thinking of what kind of care inspires someone to journey to the funeral of someone they had not seen in years upon years, and to notice — out of some kind of deep compassion — the thinness of a sweater. I wrote about this moment in a later poem. The care at the heart of my mother: to not want someone, in death, to ever be cold.

It has taken me years to sift through the sometimes ordinary, sometimes extraordinary moments of my past and see in such moments the careful noticing on the part of my mother — the journals and books she sent to me, the little library stickers she pasted on the inside covers of each, this forever-reassurance, this reminder she gave me that there might be something in me worth writing about, or writing toward. I do not think I would be writing poems — or anything else for that matter — if it were not for her. Once, when I visited her while she was sick, my mother gave me a drawing of the two of us outside of Robert Frost’s house. And though we’ve never gone, at least not yet, it’s fine. We have the present moment and it is beautiful and it is large and it is full of us. But that drawing, I sometimes think to myself — I wish I kept it. I feel it the way Laux’s speaker feels the loss of the slippers at the end of today’s poem. I want to gather up every object that might be filled with light and hold each one close.

The first line of today’s poem is equally as moving as the last:

Soon she will be no more than a passing thought

I think of the great sorrow that is the ineffable and inevitable nature of our fleetingness. How indescribable it is that people — especially those who mother us in any form — can just as quickly fill a room with light as they can leave it. Yes, in her poem “Urn,” Laux writes:

As a child I didn’t know where the light went when she flipped the switch

It’s hard not to think of death this way. For years, I felt mothered by my friend’s mother, Nancy. She was beautiful, radiant. She saw you as someone worth seeing immediately. I think of her with her camera, running alongside the trails of Van Cortlandt Park as my friends and I — she called us her boys — raced in college. I think of the golden-wheat quality of her hair behind the lens, how bright it seemed when the light caught it. And I think of the table where we sat in her house, her husband Michael cracking jokes after one glass of wine and then another. I think of how I never wanted to leave.

Not long after she died, I came over to the house and sat with Michael at that table. We read poems from Mary Oliver’s Selected and listened to songs that might play at her funeral. She would have loved this, Michael kept saying, and I kept thinking that Nancy might be around the corner somewhere, in another room filled with light still inside the house. But she wasn’t. I had never felt loss so big before. I thought there had to be somewhere where the brightness went, that it couldn’t just be gone.

Years after, I wrote an essay — “What I Want to Know of Kindness” — where I tried to pinpoint what it was exactly that Nancy had taught me through her mothering. It had something to do with grace, and masculinity, and compassion. In that essay, I wrote:

When Nancy was diagnosed with cancer, too young, and then beat it, and then was diagnosed again, and then again — well, it taught me something. It mostly taught me something about the deep inner strength that can exist inside a person, the grace that encapsulates such strength, and how strength itself should be divorced from any mention of stereotypical masculinity, should be redefined as moving through the reality of suffering with a compassion for the world.

…

This is why I hold my memory of Nancy so close, because to fail to realize what she taught me about being a man is to fail her memory. I think of her every time I receive a small kindness. I say to myself: it is alright to be loved. I think: to receive kindness is an act of kindness in itself.

I think I am so lucky to have been mothered by so many. It is a thing I will never know fully — the grace that has been offered me. What luck, that such grace has been so large that it is almost unknowable. I am holding the fact of this so close today.

I am holding close, too, the memories of kitchen tables and long nights and the small pieces of what I wish I could remember more. I am holding close the image at the end of Laux’s “Cello,” of the one tree holding the other. I am holding close the act of holding, and I am holding close the people who have taught me something about grace — that we are, as Laux writes, full of “lies and lillies,” and that it is this fullness that makes us who we are, that it cannot simply be one aspect of that fullness. And I am holding close the beauty of my own mother, and how, even though it took me years to realize such a thing, I know that she, too, taught me about fullness, and grace, and how much more beautiful the world can be if you take care to notice the thinnest sweater even in the midst of such great loss. We cannot hold everything, but I will hold the knowledge that each one of us is holding some small and ordinary bundle of light. All of that light must add up. It is the song our bearing makes. It must be some answer to the question of where the light goes when it seems to disappear.

#mom#dede#grace#thoughts#devin kelly#only as the day is long#poetry#family#love#mothers#reflection#beauty#dorianne laux#slippers#sweater#grief#loss#strength#inner strength#kindness#small kindness#light#memories#fullness#who we are

0 notes

Photo

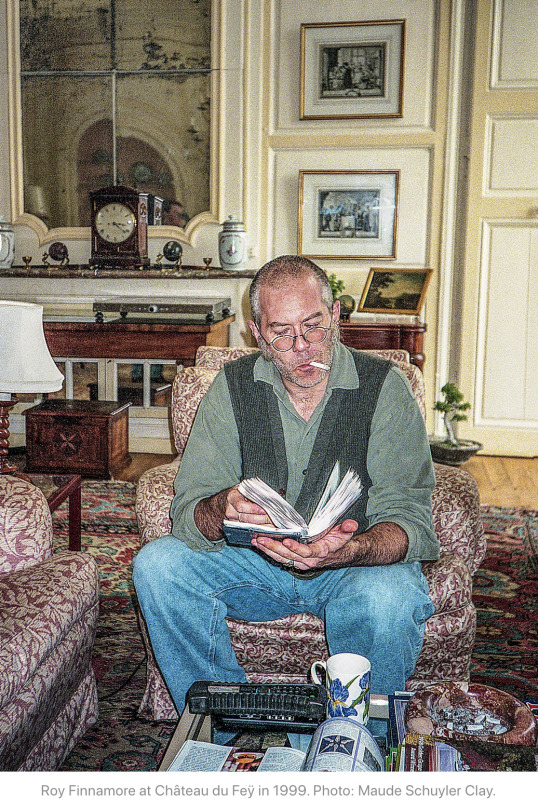

Roy Finamore

https://www.stainedpagenews.com/p/remembering-editor-and-author-roy

Howdy cookbook fans!

Earlier this month, cookbook editor, author, co-author, and food and prop stylist Roy Finamore died at the age of 70. Finamore was prolific and accomplished: the list of cookbook authors he worked with includes Martha Stewart, Diana Kennedy, Jean Anderson, Anne Willan, Lee Bailey, Carole Walter, Tom Colicchio, Bobby Flay, Gale Gand, Jacques Pépin, Marcus Samuelsson, and Rick Moonen. He was responsible for acquiring Ina Garten’s first cookbook, The Barefoot Contessa, a book that changed cookbook publishing forever. He also authored several books of his own, including 2006’s James Beard Award-winning Tasty: Get Great Food on the Table Every Day.

Last week, cookbook author and Finamore collaborator Molly Stevens (All About Braising) reached out to make sure I had heard the news. When I offered to run a few remembrances from his friends, little did I know I’d soon have an inbox full of memories a few days later! I am running them below; if you knew Roy and would like to share some memories, I’m opening up comments to everyone on this post.

Roy was, without exception, one of the most creative and brilliant individuals I’ve ever worked with, much less had the good fortune to call a friend. Beyond his massive intellect, Roy was a gifted and intuitive cook with boundless curiosity around ingredients, flavors, and techniques. I believe he was happiest in the kitchen, especially cooking for those he loved. Over the past 25 years, Roy and I spent untold hours cooking together, and in between those times, we’d call, text, and email to scheme and laugh about cooking, work, and life. Roy was my favorite kitchen companion and always the first person I turned to for advice.

—Molly Stevens, cookbook author.

I don’t know how long Roy worked at Clarkson Potter but I first worked for him on a book by Lee Bailey with Ella Brennan called New Orleans in about 1991.

Lee Bailey, Lee Klein and I comprised a team that would invade various grand Garden District homes for a day. It was real location shooting, using the homeowner’s china and flatware. While the Lees set up their tablescapes, I photographed discreet snippets and interior details. The intention was to convey a hint of some longed-for mysterious South without revealing whole rooms. We were careful not to create a catalog wish list of art and furniture for those with thieving in mind.

At lunchtime food would arrive from one of three Brennan restaurants: Commander’s Palace, Mr. B’s, or The Palace Cafe. Then it became all hands on deck, as nothing would work right in a cookbook if the food didn’t. It was a good system made pleasant with competent people.

Publishers find it risky to hand out money in lump sums and photographers need it when they need it so I do recall a prickly phone call or two to Roy about these matters. Never about editing or cropping or any other visual nuts and bolts that you might expect. Through all of it Roy and I still had not met.

That book was successful enough that a year or so later we embarked on a second project called Long Weekends. Our locations were all over the country from Dorset, Vermont to Orcas Island, Washington. It was the same M.O., but this time we added chef James Lartin as chief cook and bottle washer. Still the un-met Roy was left pulling puppet strings from his office in New York.

Lee Bailey went on to do other books with other teams. I didn’t think of myself as exclusively a food photographer. I’d done books on Monticello and Colonial Williamsburg that were more architecture and interiors. I was working a lot for House & Garden doing fine gardens. If you work for “shelter” magazines you end up photographing whatever they put in front of you. But to stay in the swim you need to schmooze with editors. I’d been in Mississippi for ten years and it was time for some visits.

In 1997 I got myself a decent suit and did some rounds. Roy was one of the first I saw. Office buildings in New York can be a bit mind numbing (to the freelancer) and Clarkson Potter was no exception. Traveling the hall, most glass cage offices had the photos of kids and grandkids that you would expect, but then you’re at Roy’s door and in a different world. My memory is telling me there were even voodoo dolls with pins in them. It was all very civil but he didn’t have anything going on and I’m sure he was wondering who this guy in a suit across from him really was.

A year later Roy called and he had a book to do with Anne Willan at Château du Feÿ in Burgundy where she lived and ran a cooking school called La Varenne. The warren—as in rabbits. It had to start in 2 weeks on July 14th with the celebration of Bastille day. Would I be interested?

Thus began nearly two years of shuttling back and forth to Burgundy and the little estate surrounding the 17th century Chateau du Fey. Anne’s book From My Château Kitchen was as much a personal memoir as a cookbook. An Englishwoman’s transformation to being head of her own French cooking school in Paris to moving down the line into Dukes of Burgundy slow food territory. Right to the agrarian source of the food itself and along with it some of the more fanciful aspects of country life.

The château was set up with the center hall as communal (living, dining, and small kitchen), with the right wing as the school with industrial kitchen—with lots of rooms upstairs, and the left wing as Anne and her husband Mark’s quarters, a business office area, a phenomenal culinary library and more bedrooms. The surrounding courtyards and walled vegetable and fruit gardens and pigeonniers were functioning more or less as when built in about 1620. It was in many ways ideal for an extended house party, and that’s what we turned it into.

Roy was there for most of it, and he was very hands on this time. It was his baby and he had done his homework and was not just there for a mini vacation. He and Anne more or less invented the book as we were shooting over several seasons. Molly Stevens, then jack of all food trades—now well-established cookbook author and jill of all food trades—was there as Anne ’s right hand in all that you need a main droite for. Roy’s friend Marian Young, who had her own literary agency, came from New York and charmed us all. Randall Price, chef, writer, actor in PBS style travelogues kept the school in shape when not in session; regaled with his not always tall tales. Even my father George came one evening from Paris on the train and fit right in. There were numbers of interns who rotated in and out and participated in the work and the play.

We worked all day shooting dishes with the chateau as a backdrop or out into Burgundy proper at a Chablis winery, at the cornichon man’s farm, at a jam maker’s up in the Morvan, in a catacomb root cellar under a 13th century cathedral, or at an artisanal cheesemakers sterilized “lab” with the curds and the herds.

Supper time started with some libation and then we usually ate what had been photographed during the day or something being tested for the next day. Any given meal found 10 or 12 of us in lively conversation. Mark was an economist so he filled us in on the EU and the euro which were about to happen. How would I know which king was which without seeing them on banknotes, I wondered. There was internet but no twitter or smart phones so we were not buried in our devices. We pretty much enjoyed each other and everyone pitched in for dishes and cleanup. You were given your own napkin and ring for the duration. If du Feÿ was Showboat then we were one big happy family.

In the early 2000’s a woman from Memphis named Ellen Rolfes, whom I had only known socially, contacted me about a cookbook called Occasions to Savor for the Delta Sigma Theta sorority. Delta Sigma Theta was formed in 1913 at Howard University and currently has over 350,000 initiated members. Tempted by this (and spurred on by having 3 kids in private school), I called Roy. His tenure at Clarkson Potter was over so he was available. We needed to do it in sorority members houses around Washington, DC. so he found a local chef and we all met at Union Station for the first time.

I stayed in the attic room of photographer/sculptor Bill and Sandy Christenbury’s house on McComb Street. Roy stayed on a friend’s couch. Roy, a city kid, didn’t or wouldn’t drive so every day I had to go pick him up in my van. The van had a faulty sensor in the automatic transmission that prevented moving from third to fourth gear every third try. Not the best for Beltway driving, but it held lots of trays of food. It all started as a bit of a comedy of errors with two crazy white boys helming a cookbook for the most serious of black sororities which claim as one of several nicknames “Devastating Divas”.

In the end not so devastating once our team cohered and the mission became clear. Any pro will tell you that if you sign on, you do your damnedest to make it work. Everybody brings something. Despite his iconoclasm Roy was always serious about work.

A coda to my working life with Roy came on a one day project—again produced by avowed Elvis nut Ellen Rolfes in Memphis: Graceland’s Table. It was a book of recipes from Elvis fans—end of story. As ideas for a book go, it was nothing if not commercial. One featured dish was a coconut-encrusted chicken submitted by a thirteen year old. Graceland is a justly famous but oddly un-grand, suburban colonial with Southern columns slapped on as a porte-cochere. It is open every day of the year but for Tuesdays in January. Nevertheless, I tapped Roy, who corralled Molly Stevens, and we picked a day and went. And did it. In one day.

The Rendezvous BBQ where we repaired to lick our wounds at the end of that day was the last place I saw Roy until he debuted his own cookbook, Tasty, in 2006 at L&M restaurant in Oxford, Mississippi, an hour plus from me in Sumner. It was a big splash made more fun for knowing most of the guests. Roy was all over signing and schmoozing. He was having whirling dervish kind of fun.

Then this winter some of our same friends at that event told me of Roy in hospice in Brooklyn. I had to go to New York to photograph my third version of the 42nd street panorama. With that project in the can we traipsed out to say goodbye. His room reminded me of his office back at Clarkson Potter. He owned the place— with games and newspapers and magazines strewn about, but of course also now the tubes and wires. We talked a bit of old times but you can’t get too deep in 15 minutes. We traded Instagram pics of our grandchild and his grandnephews and grandnieces, who will never know him.

He was so proud of his new blue hair, saying: “At last I’m an old blue-haired lady”. I had to fight like hell with myself not to take a picture.

—Langdon Clay, photographer.

Roy was one of the best editors I ever worked with, and that is saying a great deal.

—Anne Willan, cookbook author and cooking instructor.

Among the great cookbook editors of our time, Roy Finamore was unique. A James Beard Award-winning author in this own right, he was also a versatile collaborator who captured the voices of chefs as diverse as seafood expert Rick Moonen, Harlem restaurateur Marcus Samuelsson, and pastry chef Johnny Iuzzini, cooking alongside them and then streamlining their recipes to make them friendly to the home cook. As if that wasn’t enough, he was a talented prop stylist who made the food of Jacques Pépin, pastry chef Gale Gand, and even Elvis Presley look timelessly beautiful. In all these roles, Roy had a consistent approach. He was first and foremost an artist.

So it was fitting that in the pandemic lockdown, he taught himself weaving and turned out artisan napkins and placemats. He was still working his loom from his hospice bed a few days before he died.

A long-time editor at Clarkson Potter, Roy brought his visual talents to the books of Lee Bailey, Martha Stewart, and Anne Willan. He had a nose for talent. His most notable find: he acquired and launched a book by a then little-known Long Island caterer. The Barefoot Contessa began with a tiny print run and went on to become a runaway New York Times bestseller, a perennial classic with millions of copies in print. Ina Garten remains the top-selling cookbook author in the country.

Roy became the impresario of every photo shoot he worked on because he understood all aspects of food and cookbooks. He could size up in an instant exactly how long a recipe would take, which dishes would wilt when they sat and which could hold, and how long it would take to get the photo right, from which he could calculate the order that the dishes should be made.

When we discussed the photography for his book One Potato, Two Potato (coauthored with Molly Stevens), for which he chose both the designer and the photographer, he told me he planned to put the vichyssoise in a white bowl against a creamy background

Wouldn’t it look better against something more colorful? It would not, he informed me derisively. The photo, still surpassingly elegant twenty-two years after it was published, became the cover.

His culinary apprenticeship took place beside his Italian grandmother, an exacting cook, beginning when he was about four. From her, he inherited an approach summed up in the introduction to Tasty: “Good, simple food is meant to be shared and enjoyed. Cook often.” That outlook, and the memorable dishes within, earned him a James Beard Award in General Cookbooks, the most competitive category, where Tasty triumphed over hundreds of other titles.

He was a craftsman in the kitchen, neatly squaring pastry off with his hands before rolling it out, nimbly pleating Chinese dumplings, jury-rigging a steamer for crabs from what we had on hand. He would arrive at Christmas bearing all manner of jarred and bottled treats he had made over the summer: sour cherries in rum, silky tomato passata, a phenomenal Worcestershire sauce. Then he would inhabit the kitchen for the next week, turning out three superb yet simple meals a day. Nothing made him happier than when people loved his food.

As a writer, he had a light touch on the page and a direct, knowing voice. Reading his recipes, you feel him looking over your shoulder, issuing injunctions, cajoling, correcting. He didn’t suffer fools. An editorial query reflecting inattention and a lack of rigor would be met with a stinging rebuke.

When he sent me the manuscript for Tasty, he enclosed a note. “I wrote a book. I hope you like it.”

I did.

—Rux Martin, cookbook editor.

#roy finamore#cookbooks#editor#ground-breaking#james beard#cook#pioneer#stained page news#molly stevens#langdon clay#anne willan#tasty#rux martin

0 notes

Photo

I wondered what it would be like to honor my mother in the same way: to honor her with the kind of absolution we usually reserve for the dead. To mourn not who she had become but who she had once been — and not worry whether it was a grace she deserved.

Like love, there is not much to say about death that hasn’t been said before. It is often a lot of waiting around. I gathered with aunts and uncles and siblings as my mother lay in hospice. We discussed whether we liked the eggplant curry we had ordered better than the chicken. We played board games and listened to my mother’s breathing, quieting to hear it slow. Ultimately, we lost her too.

In my best moments, though, I am learning to use these questions to continue the work I started, which is to say: I use them to talk about my mother. I attempt past tense. She was beautiful and successful and sparkly. She took her chardonnay with ice.

At the end of each day, on the phone with my girlfriend 14 hours in the future, I ask her questions.

“Did you know — ?” I ask with urgency, about the smell of death, about old voice mail messages, about all matters of grief.

“Yes, I know,” she always says.

She says she likes the idea that someone only dies the last day someone says their name. I like this truism best of all.

She promises me that we have forever to master talking about it. I think we must spend forever trying.

#my mother the stranger#parents#imperfection#love#sickness#grief#loss#nyt#modern love#mother's day#alcoholism#addiction#forgiveness#grace

2 notes

·

View notes