Link

A thoughtful, sad, and all-too-common account of dispronunciation of “non-Mayflower” names in American culture, by Anand Giridharadas:

“Consider that misinformation is information that merely happens to be false, whereas disinformation is false information purposely spread. Similarly, mispronunciation is people trying too feebly and in vain to say our names — and dispronunciation is people saying our names incorrectly on purpose, as if to remind us whose country this really is.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Staying alert at Canterbury Cathedral: A case study in post-Covid design of public spaces

Last week, I visited Canterbury Cathedral – my first trip to an indoor public site or museum since March. I was both impressed and fascinated by their coronavirus safety measures and messaging, which mimics the UK government’s ‘Stay alert, control the virus, save lives’ signage in several interesting ways.

Throughout the pandemic, I have been collecting and analyzing the countless internet memes that were created to mock and undermine ‘Stay alert, control the virus, save lives’ following PM Boris Johnson’s announcement of the new slogan (previously ‘Stay home, protect the NHS, save lives’).

The signs at Canterbury Cathedral do not mock the government, but rather make use of a design that is now recognizable across the UK as representative of Covid-19 messaging. I have observed similar signage at schools and shops in my local area, but the extensive and coherent implementation at Canterbury Cathedral is worthy of its own mini-case study, which prompted this post.

The necessary design and production of Covid-19 and public health messaging provides a unique opportunity to see how nations, cultures, cities, governments, etc. respond differently to the same threat. Hunter Schwarz’s Yello newsletter has an excellent compilation of coronavirus PSAs from around the world. Now that tourism is returning we will get to see how these differences in design translate to in-person, tactical experiences on an even more micro level.

Using color to ‘mean’ Covid

The most obvious way the Canterbury signage is connected to the ‘Stay Alert’ logo is through the use of color and graphic design. In the months since ‘Stay Alert’ first emerged, the general design of the logo has taken on the meaning of ‘Covid-19 safety message’ in the UK.

Inside the cathedral and around the grounds, any messaging related to virus health and safety precautions or a change from pre-Covid policy was printed on a bright yellow sign, surrounded by a border of green stripes. This included everything from signs for the gender-neutral toilets to reminders about social distancing and hand sanitizing.

The similarity to the government’s official signage was so striking that I asked a docent if the signs had been developed within the cathedral or sent by the government – she indicated they were an inside job. One element makes this clear: The cathedral’s own local branding twist. The Canterbury Cathedral insignia and logo was included at the bottom of all signs.

Respect, protect, enjoy: localizing institutional messaging

In addition to the appropriated signage design, Canterbury Cathedral also came up with their own three-part slogan, a localized version of ‘Stay alert, control the virus, save lives.’ The government’s use of the tricolon rhetorical device (think veni, vidi, vici) is part of what makes the messaging so memorable – and mockable.

The cathedral’s remix, proudly displayed on yellow-and-green signs, reads: ‘Respect the rules, protect each other, enjoy your visit.’

Notably, the words RESPECT, PROTECT, and ENJOY were printed in green, suggesting permissiveness (green means ‘go’) and making them more salient against the remaining black text (on the original logo, all the writing is in black). I personally think the cathedral’s slogan is more effective than the government’s – the line ‘Protect each other’ introduces a layer of morality and social responsibility that was lost when the government removed ‘Protect the NHS’ from its slogan. There are also clear rules to ‘respect’ a contrast to the vagueness of “Stay alert” that has been the focus of criticism in many memes targeting the government.

Environments designed with distance in mind

Changes to a space’s physical layout are an important element of Covid-era behavioural design that might be overlooked in other analyses, but were obvious in the context of Canterbury Cathedral. In the nave of the cathedral, seats for visitors were arranged in socially-distant clusters of varying numbers, to accommodate groups of up to five.

Throughout the cathedral, a one-way walking system was implemented. Tighter spaces like some chapels, where social distancing would not be possible, were blocked off from entry. These changes, and reminders of the 2-metre distancing rule, were, of course, described on green and yellow signs. Even the large arrows delineating the path were in the requisite green.

It’s important to remember that the ‘Stay Alert’ messaging and visual brand is, like other signs, culturally-specific. While most visitors to the cathedral are likely coming from elsewhere in the UK, what happens when international tourists start showing up? Will this signage still be effective?

The multimodal redesign of Canterbury Cathedral is just a peek at what’s to come as more public spaces re-open. I look forward to seeing how other cultural institutions adjust to a new normal – and whether they adopt or reject the messaging introduced by their governments.

#coronavirus#covid19#canterbury#covid travel#canterbury cathedral#tourism#graphic design#covid design#multimodality#social semiotics#stay alert#linguistics#visit uk

1 note

·

View note

Link

I have a post published today on the blog of the PanMeMic Collective, a group of researchers interested in how Covid-19 is changing interaction and communication. It’s a bit of an introduction to my aims and theoretical lens of my dissertation, though I am focusing specifically on memes about the UK government’s “Stay Alert” guidance.

The main takeaway: Memes are perfect tools for communicating about Covid-19, because they fill three social functions that are particularly relevant now:

Memes are expressions of intersubjectivity, and help answer questions about how we as individuals are experiencing a collective shift in lifestyle.

Memes make us laugh - a coping mechanism that is normal and important during times of crisis.

The pandemic is as political as it is medical - memes are an accessible entry point into political participation, and allow millions of different voices to be heard.

#linguistics#social semiotics#memes#internet meme#internet language#langblr#sociolinguistics#internet linguistics#meme culture#meme linguistics#coronavirus#covid-19#coronavirus memes#multimodality#panmemic#pandemic#humor

36 notes

·

View notes

Link

I learned a lot from this Slate piece by Julia Craven about the history and context of capitalizing Black, as well as the ongoing debate about whether to capitalize white.

With the recent protests following the murder of George Floyd, we’ve seen companies, universities, and sports teams make long overdue changes to racist branding and messaging. We keep hearing the refrain, “Language matters” - this is true, and it goes so much deeper than avoiding racial slurs: "An uppercase letter signals importance in the mind of a reader."

This explainer foregrounds the important context that Black publications have been capitalizing the B for decades. With that in mind, it is pretty disturbing that "mainstream" publications would choose not to for so long.

One thing I have always kept in mind when writing is the importance of referring to members of any marginalized group by how they wish to be identified. This is something I thought was obvious, but the opposite is so deeply institutionalized beyond what I understood.

Craven ends the piece with a line that sums up why I and many others have felt skeptical about actions from brands that seem well-meaning and progressive on their face, but may actually mask institutionalized racism within their operations: "If the language used to describe Black people is going to change, it must carry weight. Newsrooms can’t continue to uphold racist policies and practices."

0 notes

Link

“COVID-19 has underlined the urgent need for a coordinated national framework of interpreters and translation services for Australia’s Indigenous languages, say leading experts. Indigenous community members, academics and language researchers have raced to translate crucial COVID-19 health messaging into 29 Australian Indigenous languages with a further 50 to 100 languages still to go.

To help, the Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL) based at The Australian National University (ANU) has established a resource and information clearing house for translated materials. “

The resources are now online.

Visual Collection of resources in Indigenous languages: https://covid-19-indigenous-languages-translations.dropmark.com/793396

Visual Collection of resources in English aimed at Indigenous communities in remote areas: https://covid-19-indigenous-languages-translations.dropmark.com/793398

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading list: The language of COVID-19

Tired of armchair virologists coronasplaining the Miley Cyrus to you? Do the reading yourself – I’ve curated a list of the most interesting articles on language change in the time of coronavirus that I have enjoyed lately:

A general overview to kick off the list – Professor of Linguistics Kate Burridge and Lecturer in Linguistics Howard Manns (both Monash University) discuss the humor and creativity in new coinages (The Conversation)

Linguist Tony Thorne (King’s College) has been keeping a detailed list of COVID-19 neologisms on his Language and Innovation blog

Sociolinguistics professor Robert Lawson (Birmingham City University) takes a historical approach, looking at how new vocabulary has helped us adjust to major political, social, and health upheaval (The Conversation)

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Amy Haddad discusses the prevalent use of war metaphors to symbolize the virus

But it’s a different story in Germany, where war metaphors are taboo, as German Studies researcher Dagmar Paulus (UCL) explains (The Conversation UK, re-posted on the UCL Europe Blog)

A note from the OED about language change and how the dictionary of record is handling the sudden “exponential rise” in use of specialist and new terms...

...And the list of new word entries, released off-schedule in April

Some slang terms pulled from various languages and dialects, many having to do with the universal lockdown snacking habits (1843 Magazine)

Emoji are language, too: Emojipedia has some interesting graphics about what emoji were most commonly used in coronavirus-related discussion

The Emojipedia data is analyzed from the perspective of linguistics professor Vyvyan Evans (Bangor University) in this piece from The Conversation

And if after reading these you’re feeling lucky… Sports Book Review discusses Word of the Year 2020 Futures, which are, unsurprisingly, infected with COVID-19 terms.

Enjoy!

#covid19#coronavirus#linguistics#language#langblr#neologisms#the conversation#lexicon#lexicography#pandemic#all things linguistic

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tech talk and the self

Thinking about the way we talk about using technology has changed so much... The biggest shift seems to be moving from talking about the computer/the internet, even specific websites, as “places” or “objects” to be used, and now we use language that uses more physical verbs, and evokes embodiment of the digital devices and online spaces.

Some yet-to-be-fleshed-out ideas:

Old:

- I’m going to use/play on the computer

- I am going online, I’m logging on

- Going to use the internet, I was on the internet

- I’ll send her an email

New:

- I was scrolling Instagram

- I’m going to have some screen-time

- I’ll email her

_______________________________________

Just observing the way I/my friends and family talk, I think the digital is becoming much more embedded as part of ourselves, rather than something we “do.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

What’s in a name? Why Trump’s racist labeling of the coronavirus is more than a political move

When Donald Trump referred to the novel coronavirus as the “Chinese virus,” he was doing what he does best: Making an inflammatory statement guaranteed to offend many, occupy headlines, and derail the conversation from his handling of a sensitive situation.

But the US president’s statement (and subsequent defense) is not just offensive, it violates World Health Organization guidelines for naming diseases. These best practices, which WHO laid out in 2015, “aim to minimize unnecessary negative impact of disease names on trade, travel, tourism or animal welfare, and avoid causing offence to any cultural, social, national, regional, professional or ethnic groups.”

Naming viruses is a politically fraught task; the WHO document discourages the use of geographic labels, people’s names, animal species, and cultural or occupational references. Bird flu, Ebola, and Lyme disease then, are all in violation.

Looking to a historical example, you can see just how much sticking power even a misnomer can have. The name “Spanish Flu” emerged after Spanish newspapers, free from wartime censorship, were the first to report the disease, whose geographic origins are still unknown.

Disease names can also have detrimental effects on industry - the naming of H1N1 as “swine flu” resulted in a $1.1 billion hit to the pork industry. And though the use of such names in this instance is so far limited to a few US Republican lawmakers, there have been dozens of racist assaults reported in several countries since the outbreak began.

Despite Trump’s comment making headlines and contributing to a fracturing US-China relationship, most global leaders and media outlets are still following WHO’s guidance, which explains why using the official names of diseases is so important.

The organization itself acknowledges the confusion between the name for the virus, “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2),” and the disease it causes, “COVID-19.”

Communication from authorities about the virus and disease names are specifically designed to avoid unnecessary panic: “From a risk communications perspective, using the name SARS can have unintended consequences in terms of creating unnecessary fear for some populations, especially in Asia which was worst affected by the SARS outbreak in 2003,” according to WHO.

So if WHO has already officially named the disease, how much damage can Trump’s comment really do?

Trump’s use of language has had both lexical and real effects. His pervasive use of “fake news” led the phrase to a place of legitimacy as several lexicographic organizations’ “word of the year,” and coincided with a growing distrust of the American media.

Trump doesn’t have the power to rename the coronavirus to suit his political motivations unless the media and the public give it to him. As linguist and philosopher George Lakoff puts it, “when you repeat Trump, you help Trump” -- this seems unavoidable in any media or political commentary, which is why I’ve only quoted him once.

The president knows what he is doing in trying to reframe COVID-19, and his labeling of the virus is already starting to have the same effect as some of his past offensive comments - chiefly, distracting from his administration’s handling of the outbreak.

The WHO guidance places the responsibility on scientists, national authorities, and the media to issue an appropriate name when diseases are first reported. But it is up to political leaders to use that name, or else risk harm to people, industry, and understanding of the public health threat.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Terminology’ - How a museum reckons with language choice

“The names and terminology used to describe and categorise people played a vital role in the whole edifice of slavery. Certain words became the tools of racism and, regrettably, are still in use today.

We have tried to be careful in our use of language in this gallery. In particular we have tried to avoid using terms that strip individuals of their humanity -- since this was a tactic central to the imposition of slavery.

The world 'slave,' for example, implies a thing or commodity rather than a human being. We have used the term 'enslaved African' wherever possible.

In the main we have avoided using the terms 'Black' and 'White,' preferring 'African' or 'European.' But in the Legacies section of the gallery we engage with the word 'Black' as it is used to refer to the non-White post-war migrant settlers in Britain.”

While perusing the exhibits at the Museum of London Docklands last weekend, I was pleasantly surprised to come across this sign, which provides one of the most in-depth explanations I’ve ever seen of a museum’s linguistic choices.

The museum, a branch of the Museum of London, focuses primarily on the history of the docks and London as a site of trade, which of course is heavily intertwined with the UK’s long history of slavery.

Discussing painful historical events comes with many challenges, including how and when [not] to use certain words that carry historical baggage or offensive meanings. I applaud the Museum of London for acknowledging these challenges and facing them head-on by providing an explanation of why they use the language in the exhibit.

Other signage used an interesting tactic in profiling important historical figures. Instead of highlighting the individual’s name, the placards led with that person’s relevance to the context: “Slaveowner” or “Abolitionist,” followed by a textual explanation that included their name. This approach makes the information easier to digest (understanding a concept rather than trying to memorize names), and avoids reverential treatment of history’s villains.

I did not encounter the concept of using “enslaved person” instead of “slave” until I was well into my sociology coursework at university, and I regret that it did not come up earlier in my education. It is just one of countless examples of how the linguistic repertoire available to us shapes the way we think about our world, our history, and other people. Hopefully other museums, schools, and spaces of education are being similarly thoughtful about explaining their terminology choices.

#linguistics#language#lexical choice#sociolinguistics#sociology#history#slavery#museum of london#museums#terminology#raciolinguistics#words#lexicon

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Accommodating my accommodation anxiety

In a recent episode of the excellent podcast “Lingthusiasm,” linguist Gretchen McCulloch and Claire Gawne (who speak Canadian English and Australian English, respectively), discuss linguistic accommodation – the phenomenon by which one adjusts their linguistic tics while speaking with someone who uses a different accent or dialect – as an important tool of social connection.

Adjusting one’s speech, either through lexical or accent convergence, can help the speaker feel closer to the listener, in addition to the practical benefit of being easier to understand. For example, when I visit the UK, I’ll make the lexical change of saying “do the washing up” instead of “wash the dishes.”

On the flip side, speakers may also use linguistic divergence to emphasize key differences between the speaker and listener – for example, a teacher speaking to a group of students. In both linguistic convergence and divergence, language is used as a tool to strengthen one’s sense of self and identity.

But as with anything related to identity and how one presents oneself, there can come a sense of self-consciousness. Something I’ve noticed in myself is what I can only describe as “linguistic accommodation anxiety” – the fear of sounding like I’m “trying too hard,” or even pandering in my conversations with someone using a different dialect.

In “Lingthusiasm,” McCulloch indicates experiencing a variation of the same thing, saying that she doesn’t want to seem like she is “parodying” the accent of her conversation partner. Her experience with linguistic accommodation anxiety appears to be more about making the person she is talking to feel comfortable, while mine is more self-reflective – worrying about being seen as a fraud.

I saw my fears play out in real life when the American actress Meghan Markle married the UK’s Prince Harry. The now-Duchess was widely questioned and mocked on social media over a viral clip showing her with an apparent “British accent.” In a January 2019 video, Markle can be heard asking an admirer: “Did you make that for us?” using an intonation found often in British English.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by HELLO! US (@hellomagus) on Jan 14, 2019 at 6:27am PST

Linguists who analyzed Markle’s voice agreed that no, she did not suddenly develop an accent, but was instead displaying signs of linguistic accommodation. University of Toronto linguistics professor Dr. Marisa Brook told the BBC that Markle has likely developed an “English-aristocratic” style of speaking for her interactions with the public when representing the Royal Family.

"These are the situations where people might be judging her in public instantly, where it really benefits her to sound British and aristocratic,” Brook said.

On this side of the Atlantic, progressive firebrand Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) was recently criticized by conservatives who accused her of using “verbal blackface” when speaking to an audience at the National Action Network. Ocasio-Cortez, or “AOC” as she is known colloquially, is a Latina woman who was raised in and represents one of New York’s most multicultural areas. She defended herself emphatically from the criticism, tweeting: “I am from the Bronx. I act & talk like it.”

Author and Columbia University linguistics professor Dr. John McWhorter wrote a thorough defense of AOC’s code-switching for The Atlantic, and also pointed out the breadth of traditionally-black linguistic features in other US dialects.

“Ocasio-Cortez, as a Latina, was not using a dialect foreign to her experience. She grew up around it; it would be surprising if she did not have it in her repertoire to some extent,” McWhorter writes. “Anyone who would riposte that she isn’t from the black Bronx in particular would miss that Black English stopped being a black-exclusive dialect in the Bronx decades ago.”

Between the controversy over Markle and AOC’s “accents” and the knowledge that my friends would likely tease me (without malice, but embarrassing all the same) if I came home from a few months in the UK speaking with any sign of a British lilt, I often feel hyper-conscious of what is a socially acceptable level of linguistic accommodation.

This fear of being seen as a fraud is so strong that I hear myself compensating in the other direction, and consciously or subconsciously emphasizing my Wisconsin accent: drawing out my vowels, using a notably hard “R,” and even over-using phrases that normally come out only sparingly.

While I’m less self-conscious about lexical accommodation through the use of British English phrases, I am aware of myself trying harder to steer clear of accent changes. And is this, in itself, a type of linguistic accommodation that happens to be more self-serving?

Dr. Marisa Brook’s comments on Meghan Markle to the BBC provide some reassurance: "If it's conscious, I don't think it makes her manipulative, or a poser or anything," she says of Markle. “She's someone who's very off-beat from those who usually join the Royal Family - it makes a lot of sense. It's not that she is changing who she is. It's like she's changing how she dresses - it's like an extremely fancy outfit.”

As I prepare to move to the UK for graduate school and to possibly “settle down,” many friends have asked if I’m going to “have a British accent” in a couple of years. I do notice myself picking up words and idioms here and there (the American English equivalent for “a spanner in the works” is wholly inadequate, and “quite” is quite a helpful qualifier), but I wonder if my “accommodation anxiety” will slowly dissipate, or if it is a permanent hurdle for truly fitting in to life in London.

#linguistics#sociolinguistics#allthingslinguistic#lingthusiasm#linguistic accommodation#anxiety#british english#american english#accent#langblr

1 note

·

View note

Photo

First reaction to this headline: Why would you name a trash can?

0 notes

Link

Big news in the media world: The AP Stylebook is now officially discouraging publications from using euphemisms like “racially charged” and “racially tinged” in place of “racist.” The change follows repeated backlash against The New York Times, Washington Post and others for using the terms.

The AP notes: “If racist is not the appropriate term, give careful thought to how best to describe the situation. Alternatives include racially divisive, racially sensitive, or in some cases, simply racial.”

It will be interesting to see how quickly publications make changes, and where they still opt to use a less “divisive” word.

0 notes

Text

You wanted to speak to the manager, Denise....

Say “Bye, Felicia” to “Bye, Felicia.” The internet’s new favorite clapback comes from an unexpected source: Meghan McCain, co-host of “The View” and daughter of the late Republican Sen. John McCain.

In what she herself has since dubbed “everyone’s clap back [sic] to everyone” McCain this week fired off an iconic tweet in response to criticism of her show from a conservative commentator:

“You were at my wedding, Denise.…”

Twitter didn’t miss a beat – within hours, feeds everywhere were clogged with gifs, quote-tweets and screenshots all illustrating the epic clapback. McCain herself acknowledged the viral moment, calling it her “gift to the internet.”

A fiery response is nothing new for McCain – she has become known for her sassy responses to President Trump’s criticism of her father. But while those comments make it into the news cycle, they don’t dominate Twitter or become memes.

So what is it about *this* response that allowed it to take off in such a way? It’s not the Meghan effect… could it be Denise?

The Denise in question here is D.C. McAllister, a conservative political commentator and contributor to “The Federalist,” the conservative website owned by McCain’s husband. One particularly cutting element of McCain’s tweet was her use of McAllister’s given name. By steering away from the gender-neutral (and frankly, more badass) implications of “D.C.,” McCain asserts her power and appears to be giving ol’ Denise a dressing-down. It comes off as a twisted version of the way a parent might use their child’s full name to signify that they are in trouble.

But there is something about the name “Denise” in particular that just checks all the boxes. Brief experimentation shows that the remark just doesn’t really work with other names:

you were at my wedding, Rachel…

you were at my wedding, Carmen…

you were at my wedding, Melania…

you were at my wedding, Eileen…

It also doesn’t have the same effect using a traditionally male name:

you were at my wedding, Kyle…

you were at my wedding, Tom…

you were at my wedding, Marcus…

Between the tone of McCain’s comment, the second syllable stress and its inherent whiteness, “Denise” conjures up a certain image that many of us, online or not, are familiar with: The “Can I speak to the Manager?” lady.

She sports a short, spiky haircut with streaky highlights, drives a minivan, and wears bermuda shorts. She can be found at a Starbucks, Target, or Apple Store loudly complaining to a cashier about the poor service she has allegedly received. She is named “Kim” or “Karen” (or Denise). And she is definitely white.

As Rob Dozier wrote in Slate in 2018, the “Can I speak to the manager” lady is “a digital caricature illustrating a particular kind of white person—one who would see no problem asking to speak to the manager over a minor inconvenience or for receiving service that doesn’t meet her standards.”

When I first spotted McCain’s tweet, I couldn’t help but imagine Denise as Ms. “Can I speak to the manager” herself. In the diegetic world of the meme, “Can I speak to the manager” woman is also likely to be criticizing “The View” on Twitter, and maybe even attending the wedding of a B-list conservative celebrity.

In this scenario, McCain’s “you were at my wedding” response carries a similar tone of “I’m putting you in your place” condescension. The entire exchange is two privileged, petty, white women, each demanding to speak to the manager at increasing volume until one explodes in a *poof* of Bath & Body Works fragrance.

In Slate, Dozier describes the “Can I speak to the manager” meme as a “shorthand for the excesses of privileged whiteness,” tying it to the more serious trend of white people calling the cops on black people for holding barbecues, selling water, or otherwise simply living their lives.

The #LivingWhiteBlack hashtag took off last summer, introducing the world to “BBQ Becky,” “Gas Station Gail,” and “Permit Patty,” just to name a few. Like the “Can I speak to the manager” lady, the aforementioned women leaned into their white privilege to police and judge the behavior of people around them who they deemed “less-than.”

Those nicknames were not the actual names of the white perpetrators in the news stories, but were effective in spreading awareness of the incidents on social media because of their alliteration and comical pointedness. The whiteness and tone of the name “Denise,” especially now that it is the key character in a viral meme, make it perfect for this kind of mockery: Can’t you just imagine a “Dairy Queen Denise?”

This post is in no way meant to be a dig at anyone named Denise – a lovely name that of course does not inherently mean its bearer is racist, demanding, or any other quality listed above.

But at least in my mind, there is a natural link between “Denise” and “can I speak to the manager” lady that contributes to the internet sticking power of McCain’s clapback.

#names#you were at my wedding denise#denise#meghan mccain#can i speak to the manager#bbq becky#living while black#meme#memes#meme linguistics#linguistics#language#internet#internet language#internet culture#meme culture#twitter

0 notes

Text

W(h)acky Musings

Newsrooms across the country were split this week over what I firmly believe to be an errant “H.”

President Trump, in the midst of a bitter online feud with the husband of one of his closest advisers, delivered a vocal blow while speaking to reporters. Moments before traveling to Ohio, the president called Kellyanne Conway’s husband, George, a “wack job.” Or perhaps a “whack job.”

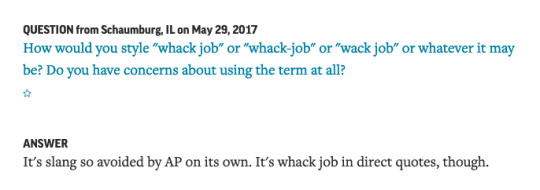

Publications couldn’t seem to agree on the spelling of the insult, which, while spoken colloquially often enough, is rarely printed in the pages of the New York Times and the like. So rarely, in fact, that the AP Stylebook–the Holy Bible of newspaper grammar–does not have an entry for the word.

The guide’s only reference to the term appears to be an answer to a May 2017 question from a reader: “It’s slang so avoided by AP on its own. It’s whack job in direct quotes, though.”

As a J-school trained reporter, I usually defer to the prescriptivism of the Stylebook as the reigning authority. But this is a rare case where I think the book is wrong, and it’s a hill (with an H) that I’m willing to die on.

My reasoning: The dig “wack job” itself stems from the other, slightly less offensive, insult of “wacky.” Someone who is so wacky that the word doesn’t do it justice could, logically, be referred to as a “wack job.” Merriam-Webster’s entry for “wacky” notes that “whacky” is a less common spelling of the word, while the Cambridge English Dictionary lists it only as “whack job.”

While language and spelling are of course ever-fluid and evolving, “whack” here is not a viable alternate simply because it means something else. In my own newsroom, several people correctly observed that “whack” means to hit or wallop, and therefore “whack job” sounds like something from a mafia movie. One brave soul noted on the company-wide email chain that “whack job” could be perceived to have sexual connotations.

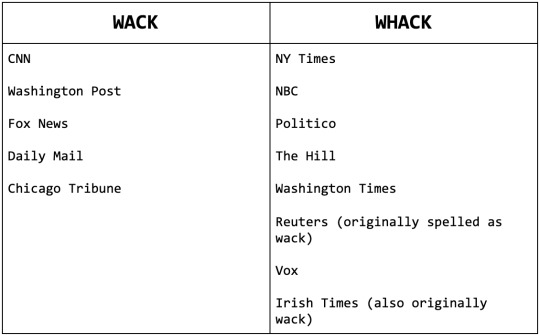

Which is why I was so shocked to see so many publications, including my own, go with the H. The schism was widespread, with newspapers leaning more in favor of “whack,” and some even starting the day sans-H and adding it later on.

CNN senior editor Amanda Katz tweeted that after much debate, the outlet’s fact-checking team ultimately went with “wack job,” adding that “a hit man performs a ‘whack job.’”

Political journalists and copy editors were whacked in the face with the word on Wednesday, but it is by no means the first time the debate has come up.

Grammarist identifies the phrase as “wack-job,” but notes that it is usually spelled “whack-job.” The blog raised the fair point that including the H implies a figurative brain injury resulting in said wackiness: “Perhaps we are to infer that a whack-job is someone who has been whacked in the head, figuratively or otherwise.”

Gawker took a strong stance in favor of “wack” in 2013 in a response to a post from esteemed writer and cultural commentator Ta-Nehisi Coates under the headline “My President Is Whack.”

“The word meaning ‘bad, messed up, stupid, boring, dumb, uninteresting, unenjoyable, or otherwise not good’ is spelled ‘wack.’ The letter ‘H’ is not involved.”

Like the AP Stylebook, Gawker makes the important point that “wack” and “wack job,” no matter the spelling, are spoken slang, so “when you ask how it's spelled, you're just asking someone to make up a spelling on the spot.”

“Slang words are inherently flexible and ever-changing and and slang is whatever we make it,” the post reads. “There is no appeal to authority that can settle this argument once and for all.”

Still, I think Gawker’s final verdict stands: “It's wack. It's not ‘whack.’ That shit looks ridiculous.”

And until the day I use ���whack job” in a piece about a particularly violent sexual act (entirely plausible in the modern news landscape), the AP Stylebook can keep its H’s. And don’t even get me started on the hyphen.

#grammar#spelling#linguistics#langblr#journalism#writing#grammar nerd#politics#political news#trump#media#media criticism#internet linguistics#ap stylebook#ap style#journalist#wack job#whack job#wacky

1 note

·

View note

Link

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

What’s new with the State of the Union? 14 words, to be exact.

No matter the political party, a president’s State of the Union speech carries a certain amount of historical weight. Whether the person delivering it is inspiring or enraging a nation, the pomp and circumstance surrounding the time-to-time address prompts Americans’ ears to perk up.

And while even the most engaged of political wonks may forget the overarching message, the substance of the speech is worth taking a closer look at.

The nature of the changing world, social trends and news cycle naturally means that every speech will contain some words that have never before been used. Those words represent some interesting lexical trends, as far as politics are concerned. By looking at just the “new words” introduced when the leader of the country addresses Congress, we learn a lot about the way the nation behaves and communicates at a certain point in time.

A Washington Post analysis of SOTU speeches in recent years found that in 2019, President Trump used over a dozen words that made their first State of the Union appearance, including “bloodthirsty,” “kissing,” “SWAT” and “venomous.”

Out of the 14 words that Trump introduced to the State of the Union this month, the most striking is his naming of “fentanyl,” the synthetic opioid that was recently named the deadliest drug in the U.S. Trump was also the first president to say “opioid,” in his 2018 speech.

Though the opioid crisis has been affecting communities since the late 1990s, the fact that the name of a specific drug is now so recognizable on a national level is indicative that we have reached a new phase in how we treat addiction in the public lexicon.

On the flip side, the most controversial word (and indicative of the political climate) used by Trump this year was “womb, He used this word in criticizing legislation protecting women’s reproductive freedoms, saying: “Lawmakers in New York cheered with delight upon the passage of legislation that would allow a baby to be ripped from the mother’s womb moments before birth.”

“Womb” is not a scientific word, and is often used by anti-abortion (pro-life) activists in place of “uterus” to convey a message of coziness and warmth.

Former President Barack Obama’s State of the Union speeches, by contrast, introduced a number of words that, at the time, would have been considered socially progressive. In 2015, he became the first president to say “bisexual,” “lesbian,” and “transgender” in a State of the Union.

Looking back, it’s almost shocking that those words made their first State of the Union appearance only four years ago – “Gay” was uttered for the first time 15 years earlier, by then-President Bill Clinton in his final address, while mentioning the brutal 1998 beating and murder of Matthew Shepard, one of the first nationally-discussed anti-gay hate crimes.

By revisiting the context of these first utterances, we can really get a sense for how quickly once-“controversial” words can become commonplace. A president choosing to use such words in their State of the Union speech can accelerate that process.

Some other notable themes that emerged in the Washington Post analysis include the following:

Obama’s naming of tech companies: He was the first president to say “Facebook,” “Google,” (both 2011), “Verizon” (2014) and “Tesla” (2015). Clinton was the first to use “Internet” in 1997.

President George W. Bush, who presided over wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, was the first to use the names of terrorist groups like Hamas, Hezbollah, (both 2002) and the Taliban (2004). In his 2002 address, while the U.S. was still in the early stages of 9/11 recovery, he introduced “firefighter” and “firefighters” to the State of the Union lexicon.

Bush also used “Muslim” and “mosque” for the first time in his 2007 speech.

Like many presidential traditions, the State of the Union speech can feel stuffy, formulaic, and frankly, uneventful. So next year, listen closely for what you haven’t heard before–those are the words that shape history.

#state of the union#sotu#trump#president trump#president obama#president bush#president clinton#bush#obama#clinton#politics#language#linguistics#langblr#lexicon#words#sociolinguistics#history#lingthusiasm

1 note

·

View note

Link

I’ve had many interesting conversations with visually impaired friends about the difficulties of communicating with emoji – often the description of an emoji picked up by screen-reading software doesn’t match the meaning that the sender intended.

This lost-in-translation aspect happens even with two sighted users, is exacerbated by communicators using different devices (iPhones vs. Androids), and is even more prominent when one user is relying on screen-reading technology.

Glad to see both that Unicode approved this wide range of representative emoji, and that the descriptions are straightforward!

38 notes

·

View notes