Writing advice blog The Ghosts of Glass Lake I write stuff, click me don't click me 616 291 8519

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

reading gilgamesh for the first time and am surprised to see people were REALLY fucking with himbos like 3,000 years ago

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

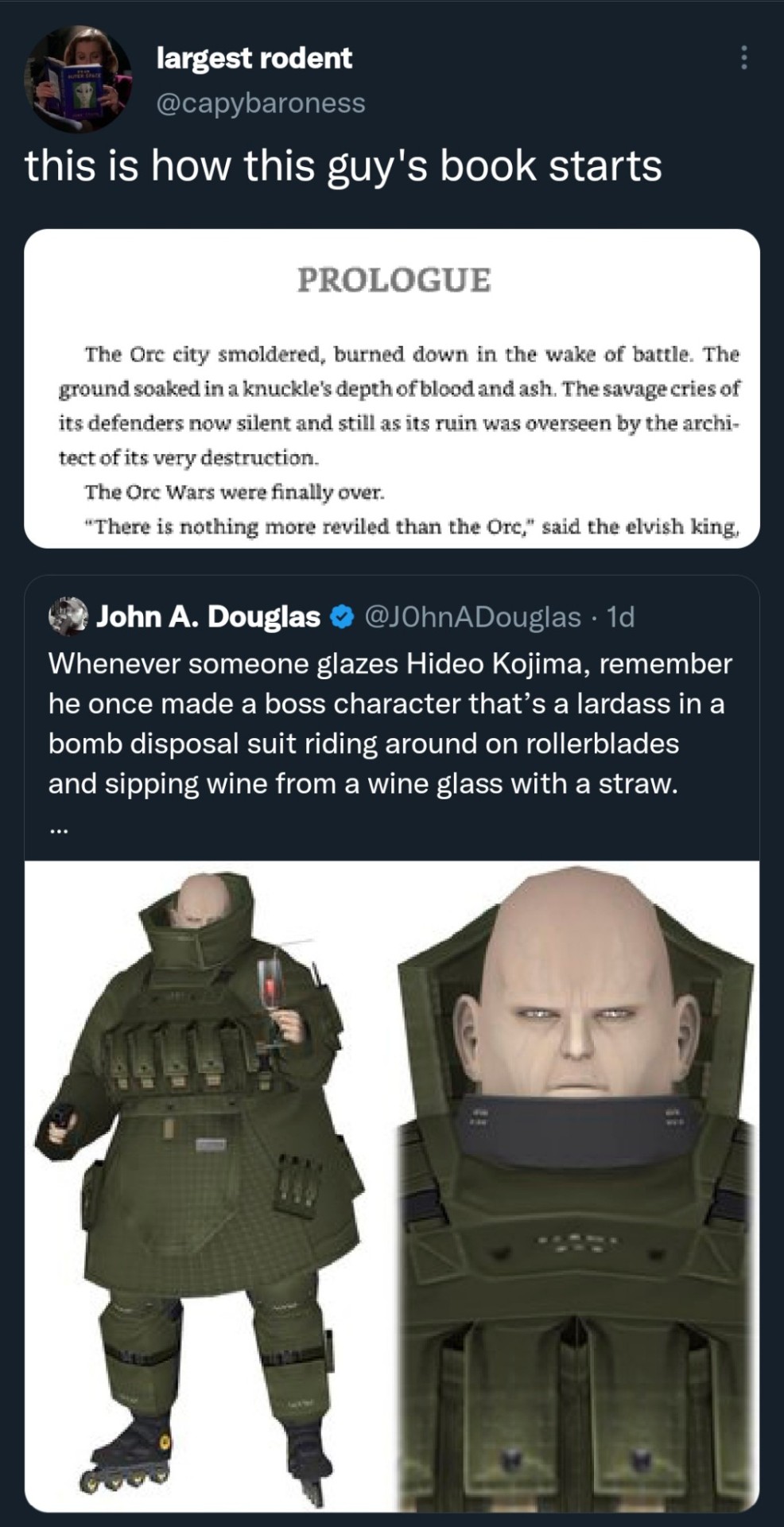

The thing about orc city is that the city is not named "orc city". The book refers to it as "the orc city". That combined with the elf king's "there's nothing more reviled than the orc" could actually work for a book that wanted to explore the dehumanisation of the enemy. But considering the author was unable to link Fat man to the nuke dropped on Nagasaki I don't think thats what's happening here

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

wait what i did not know that was lingo people used already, my b my b

I love the orc city meme because it's genuinely a great meta commentary on how many fantasy writers nowadays write D&D campaign templates, not books.

As an unabashed genre fantasy writer I know this is rich from me but like. Come on folks. We can do better than this

711 notes

·

View notes

Text

In light of the desecration of Orc City, let's talk about what actually went wrong. I see a lot of people dogging on this brief introduction, and rightfully so, but we can also learn a thing or two from good-faith critique. Here are my general notes, starting with a few things I think went right:

+ Keeping the Orc city in question unnamed is a smart choice. It signals that the perspective the story is told from is dismissive of the Orcs and lends an off-putting sense of importance to the city in question. It's a little like the "not sane" bit in the opening of The Haunting of Hill House: "No live organism can continue for long to exist under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within." Shirley Jackson obviously does much more to achieve her effects with this opening, but I thought this bit of the Orc city was fine.

+ "Orc city smoldered" is sonically appealing.

+ Unsure if this was intentional or an accident, but Orc being capitalized while elvish isn't may imply a level of actual, subversive authority to the Orcs that the elves lack, akin to the power underground writers and artists have against oppressive regimes. Or is it common fantasy spelling to lowercase races when they're adjectives and to capitalize when nouns?

That's about it for the positives. Now the negatives:

-In his book On Becoming a Novelist, John Gardner talks about his idea of "authority," by which he more or less means "the voice and techniques of the author that make the reader believe the person writing is in fact a 'real writer.'" (I don't have the book on me to find exact quotations--kill me. But read the book if you can. It's excellent.) This opening has none of that authority, chiefly because it overexplains. The Orc city "smoldered," and it was "burned down." Not only that, but the ground is covered in blood and ash. And in case you were wondering, yes, those screams of war are also gone now, because the city is gone. And someone is standing over the city, someone the reader assumes played a part in the city's destruction even before the reader is told that he was "the architect of its very destruction." You get the sense that the author is fawning over the reader like a helicopter parent, making sure they understand exactly how to view the events of the story without making room for any sort of analysis on the reader's part. The author doesn't trust his reader enough to have fun in his story, so he tries to make it sound cool without it being all that cool.

-On that note, the author tries to make this opening sound cool largely from the gratuitousness of detail, but it just comes off as edgy and inchoate. We get it, a battle happened--but why should the reader care? Tell me about a specific Orc character or Elf character before you tell me about the blood, ash, savage cries, etc. This isn't to say that an author can't start a book with this sort of panoramic summary (see the Hill House example above), just that you can't be sweaty about it. All these details make it sound like the author is trying too hard to be appealing.

-The panoramic summary style of narration is its own miss here, I think, but this is partly a stylistic concern. The danger in going with this opening is that you miss a lot of great potential narrative work: who are some of the Orcs who lived in this city, and what was their life like before the war? What are their relationships with the Elves like? Imagine a similar story told from the perspective of an Orc in a region the Elves have been sacking (maybe drawing from All the Light We Cannot See or other WWII narratives?). The reader could follow the embodied narrative of a handful of Orcs making their way through the world, which would make the emotional import of the razing much stronger. (NOTE: going too far down this train of thought leads to a strict adherence to the "show don't tell" dogma that I don't agree with. "Showing" is preferred in narrative, I think, but "telling" summaries like this can work. Again, the biggest issue here is that the author very clearly wants the reader to care about this summary on an emotional level when the novel hasn't done enough work yet to make the reader care on that level. One of my MFA professors always tells us that "a good novel teaches its reader how to read it." Since this is the opening of the book, I haven't been taught anything about the writer's style, so this falls flat.)

With those more existential critics about the opening, here are some technical issues that are easily fixed but also not easily missed if the piece is run through with a fine-toothed comb:

-Redundancy in "smoldered" and "burned down." Could just write "The Orc city smoldered in the wake of battle."

-Can trim the preposition from "burned down" to improve the flow. "The Orc city burned in the wake of battle."

-"Wake of battle" is a little cliche, could easily find some more interesting language to describe a Sodom-and-Gomorrah-esque razing.

-"A knuckle's depth of blood and ash" has some merit, but the weaker quality of the surrounding prose makes this stick out like a photograph in bad lighting. The phrase itself could also be tinkered with to clean out some unnecessary words. Maybe something like "ash covered the ground up to the knuckle"? I think that "depth" word is my issue. It feels just a little too formal.

-Can combine "savage cries" into a stronger noun that doesn't need the "savage" rider. Or could just cut the "savage" altogether--the reader understands the worldview of the Elves vis-a-vis the Orcs lmao.

-"Silent and still" is redundant, just cut one.

-"The architect of its very destruction" is a crazy leap in verbiage. Tone this down, and chop that "very" off while we're at it. Maybe something like "as the elvish king scouted the ruins of the Orc city." Even something that simple works much better (and is much cleaner!)

-That second sentence isn't actually a complete sentence, either. There's no main verb. "The savage cries of its defenders [noun group] now silent and still [adj. group] as its ruin was overseen by the architect of its very destruction [adv. group]." It looks like the "as" in "as its ruin was overseen" is supposed to be the main verb, but since there is no other main verb earlier in the sentence, this reads as just part of the descriptive clause. I think the author is looking for "The savage cries of its defenders WERE now silent and still as its ruin was overseen..."

-Why is the elvish king saying "There is nothing more reviled than the Orc"? Surely the other characters around him understand this already, so it feels like the elvish king is looking directly into the camera and telling the audience this. But the audience also easily intuits this from, y'know *gestures at the blood and ash.* This dialogue is dead weight, and this first bit of dialogue right after the razing could be used to say something really poignant about the story.

-Maybe more of a personal stylistic choice, but I think "reviled" is too fancy a word to use here. It reads like when someone writes in faux-Medieval English to try to match a "ye olde fantasy" mood. I think the real issue here is that "reviled" stands alone in this sentence as being overly purple. If its surrounding words also got across the faux-Medieval tone (i.e. if the novel taught us how to read it), then it would work. But as it is, it sticks out as in in bad lighting.

There's probably more to add, but I started writing this at like 8am and am sleepy at work. Long live Orc city.

the orc city

#orc city#writing#writing advice#writeblr#orcs#i have other posts on writing advice and all that too if you want#you'll have to sift through some shitposts and mcdonalds roleplay#but hey you're on this website for a reason

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been starting to call this kind of writing "dollposting," because the writer really just wants to move dolls (their characters) around in a dollhouse (their fun setting). This definitely isn't exclusive to fantasy/sci-fi, but since a lot of young writers don't read much outside that sphere, dollposting happens most there

I love the orc city meme because it's genuinely a great meta commentary on how many fantasy writers nowadays write D&D campaign templates, not books.

As an unabashed genre fantasy writer I know this is rich from me but like. Come on folks. We can do better than this

711 notes

·

View notes

Photo

type of shit i'm on

low-poly pixel GameCube!

16K notes

·

View notes

Note

I recommend "The Book of Margery Kempe" and "Nibelungenlied" if you can find a reliable translated version (I'm fluent in German so reading Nibelungenlied isn't a big problem for me)

I've been looking for a Nibelungenlied copy!! I'll shift that up to the top of my books-to-find list. I've read Beowulf and the Volsunga saga, which I've heard are like the Anglo and Norse variants of some similar story. Will definitely add Margery Kempe to the list too, I looooove Medieval Christian shit

1 note

·

View note

Text

Does anyone have Medieval book recs?? That time period on my book shelf is kind of only supplied by Chaucer, Sir Gawain, and some Norse sagas. What other big or lesser-known names came out of that long time period?

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

I woke up this morning and immediately thought of this, but instead of Steven Universe, I thought "sexual uh-ssault," which gets the incorrect buzzer

stfu = shut the fuck up

tf = the fuck

su = ...steven universe?

the english language is beautiful

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

stfu = shut the fuck up

tf = the fuck

su = ...steven universe?

the english language is beautiful

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I managed to wrangle my brain enough to read ONE (1) book, wrow!

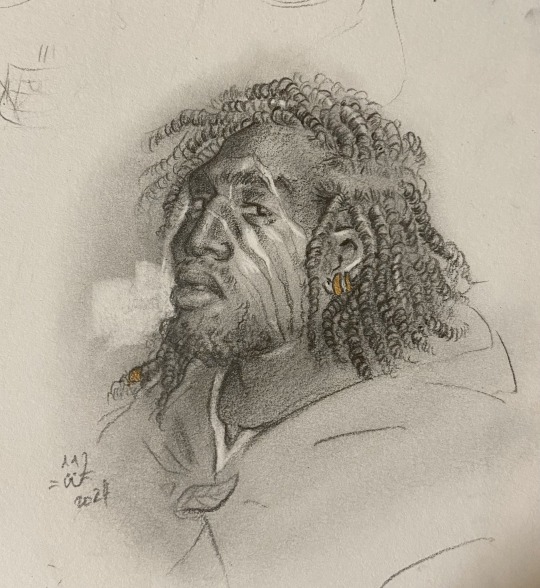

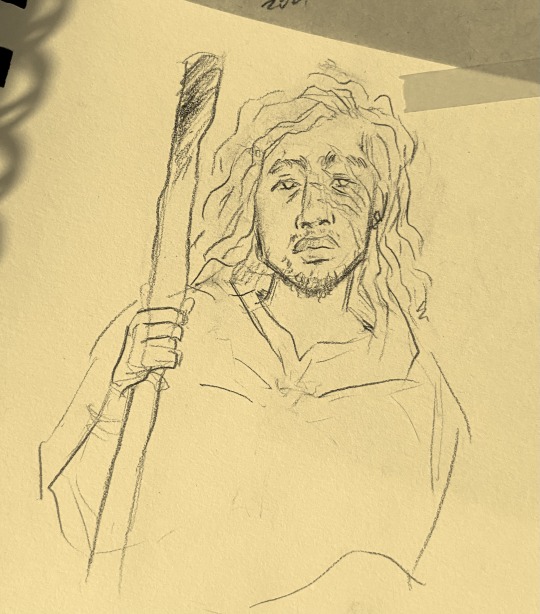

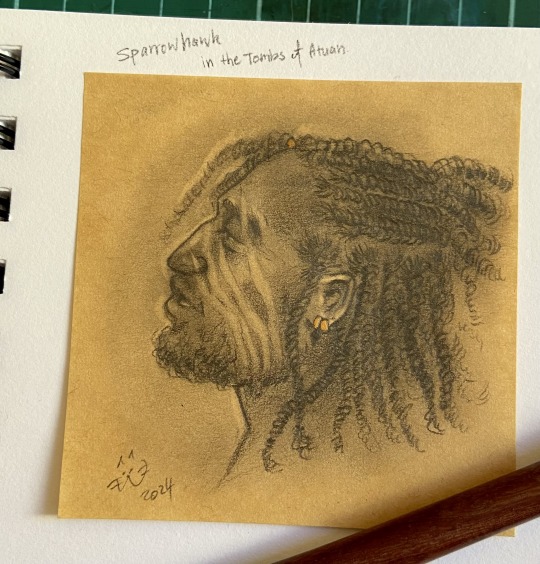

Anyway, here are some attempts of drawing The Tombs of Atuan era Sparrowhawk from Earthsea.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm curious why I see so many writing posts here talking in terms of genres, character labels ("villain," "hero," idk "whump"?), and specific tropes (all the "character A and character B" stuff, shipping dynamics--you know). I feel like putting a story and its elements under labels like this probably just restricts where your story really wants to go and ends up being more or less derivative. I think writing is similar to comedy in that if you dissect the art too much, you end up killing it by writing something sorta fun and floofy and railroaded.

Not that writing has to be some grandiose "deeper" thing, just that writing discussions centering around that stuff here feels weird. Genuinely wondering--can anyone weigh in?

As Lear said (probably), "anatomize [your story], so you can put it into little boxes"

8 notes

·

View notes