#écu

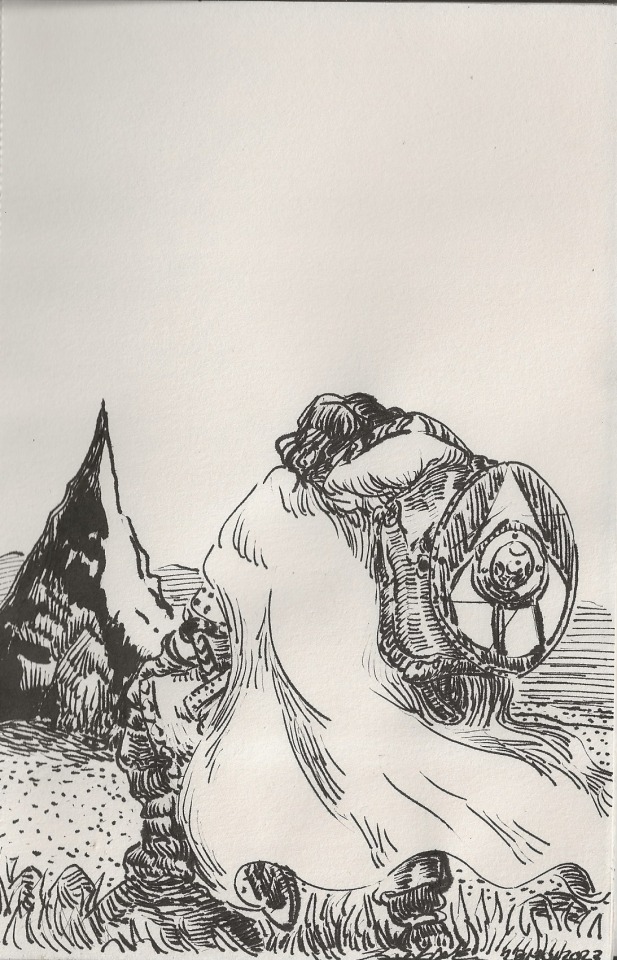

Text

Tales from Tennyson told by Nora Chesson

Source : archive.org

1900

Artist : Frances Brundage

The Lily Maid

#alfred lord tennyson#alfred tennyson#1800#the lily maid#lilies#lily#maid#arthurian legend#arthurian mythology#arthurian literature#children's literature#children's books#vintage illustration#old illustration#shield#bouclier#écu#lady#middle age#moyen âge#medieval#white flowers#flowers#lion#armoiries#crest#lis#lys#frances brundage

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fin août, je suis remonté vers le Nord en passant par l'Auvergne et Vichel.

Le Broc, ma balade de ce jour. Sur le plateau, alternées ici avec un Silène qui volète, de mystérieuses pierres gravées, représentant - dans l'ordre ici, un fauve, un gisant en robe, une tête de satyre moustachu et un blason portant un lion.

#le broc#auvergne#pierres sculptées#papillon#silène#entomologie#lépidoptère#fauve#lion#blason#écu#héraldique#gisant#satyre

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

im bilingual. i can sew. i will happily memorize historical facts and serve rabbit stew and vegetable soup to sweaty tourists every day. i might be 29 and employed but i can dream of having a fun summer job too

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frev Friendships — Saint-Just and Robespierre

You who supports the tottering fatherland against the torrent of despotism and intrigue, you whom I only know, like God, through his miracles; I speak to you, monsieur, to ask you to unite with me in order to save my sad fatherland. The city of Gouci has relocated (this rumour goes around here) the free markets from the town of Blérancourt. Why do the cities devour the privileges of the countryside? Will there remain no more of them to the latter than size and taxes? Support, please, with all your talent, an address that I make for the same letter, in which I request the reunion of my heritage with the national areas of the canton, so that one lets to my country a privilege without which it has to die of hunger. I do not know you, but you are a great man. You are not only the deputy of a province, you are one of humanity and of the Republic. Please, make it that my request be not despised. I have the honour to be, monsieur, your most humble, most obedient servant.

Saint-Just, constituent of the department of Aisne.

To Monsieur de Robespierre in the National Assembly in Paris.

Blérancourt, near Noyon, August 19, 1790.

Saint-Just’s first letter ever written to Robespierre, dated August 19 1790

Citizens, you are aware that, to dispel the errors with which Roland has covered the entire Republic, the Society has decided that it will have Robespierre's speech printed and distributed. We viewed it as an eternal lesson for the French people, as a sure way of unmasking the Brissotin faction and of opening the eyes of the French to the virtues too long unknown of the minority that sits with the Mountain. I remind you that a subscription office is open at the secretariat. It is enough for me to point it out to you to excite your patriotic zeal, and, by imitating the patriots who each deposited fifty écus to have Robespierre's excellent speech printed, you will have done well for the fatherland.

Saint-Just at the Jacobins, January 1 1793

Patriots with more or less talent […] Jacquier, Saint-Just’s brother-in-law.

Robespierre in a private list, written sometime during his time on the Committee of Public Safety

Saint-Just doesn’t have time to write to you. He gives you his compliments.

Lebas in a letter to Robespierre October 25 1793

Trust no longer has a price when we share it with corrupt men, then we do our duty out of love for our fatherland alone, and this feeling is purer. I embrace you, my friend.

Saint-Just.

To Robespierre the older.

Saint-Just in a post-scriptum note added to a letter written by Lebas to Robespierre, November 5 1793. Saint-Just uses tutoiement with Robespierre here, while Lebas used vouvoiement.

We have made too many laws and too few examples: you punish but the salient crimes, the hypocritical crimes go unpunished. Punish a slight abuse in each part, it is the way to frighten the wicked, and to make them see that the government has its eye on everything. No sooner do we turn our backs than the aristocracy rises in the tone of the day, and commits evils under the colors of liberty.

Engage the committee to give much pomp to the punishment of all faults in government. Before a month has passed you will have illuminated this maze in which counter-revolution and revolution march haphazardly. Call, my friend, the attention of the Jacobin Club to the strong maxims of the public good; let it concern itself with the great means of governing a free state. I invite you to take measures to find out if all the manufactures and factories of France are in activity, and to favor them, because our troops would within a year find themselves without clothes; manufacturers are not patriots, they do not want to work, they must be forced to do so, and not let down any useful establishment. We will do our best here. I embrace you and our mutual friends.

Saint-Just

To Robespierre the older.

Saint-Just in a letter to Robespierre, December 14 1793

Paris, 9 nivôse, year 2 of the Republic.

Friends.

I feared, in the midst of our successes, and on the eve of a decisive victory, the disastrous consequences of a misunderstanding or of a ridiculous intrigue. Your principles and your virtues reassured me. I have supported them as much as I could. The letter that the Committee of Public Safety sent you at the same time as mine will tell you the rest. I embrace you with all my soul.

Robespierre.

Robespierre in a letter to Saint-Just and Lebas, December 29 1793

Why should I not say that this (the dantonist purge) was a meditated assassination, prepared for a long time, when two days after this session where the crime was taking place, the representative Vadier told me that Saint-Just, through his stubbornness, had almost caused the downfall of the members of the two committees, because he had wanted that the accused to be present when he read the report at the National Convention; and such was his obstinacy that, seeing our formal opposition, he threw his hat into the fire in rage, and left us there. Robespierre was also of this opinion; he believed that by having these deputies arrested beforehand, this approach would sooner or later be reprehensible; but, as fear was an irresistible argument with him, I used this weapon to fight him: You can take the chance of being guillotined, if that is what you want; For my part, I want to avoid this danger by having them arrested immediately, because we must not have any illusions about the course we must take; everything is reduced to these bits: If we do not have them guillotined, we will be that ourselves.

À Maximilien Robespierre aux enfers (1794) by Taschereau de Fargues and Paul-Auguste-Jacques. Robespierre and Saint-Just had also worked out the dantonists’ indictment together.

…As far from the insensibility of your Saint-Just as from his base jealousies, [Camille] recoiled in front if the idea of accusing a college comrade, a companion in arms. […] Robespierre, can you really complete the fatal projects which the vile souls that surround you no doubt have inspired you to? […] Had I been Saint-Just’s wife I would tell him this: the sake of Camille is yours, it’s the sake of all the friends of Robespierre!

Lucile Desmoulins in an unsent letter to Robespierre, written somewhere between March 31 and April 4 1794. Lucile seems to have believed it was Saint-Just’s ”bad influence” in particular that got Robespierre to abandon Camille.

In the beginning of floréal (somewhere between April 20 and 30) during an evening session (at the Committee of Public Safety), a brusque fight erupted between Saint-Just and Carnot, on the subject of the administration of portable weapons, of which it wasn’t Carnot, but Prieur de la Côte-d’Or, who was in charge. Saint-Just put big interest in the brother-in-law of Sijas, Luxembourg workshop accounting officer, that one thought had been oppressed and threatened with arbitrary arrest, because he had experienced some difficulties for the purpose of his service with the weapon administration. In this quarrel caused unexpectedly by Saint-Just, one saw clearly his goal, which was to attack the members of the committee who occupied themselves with arms, and to lose their cooperateurs. He also tried to include our collegue Prieur in the inculpation, by accusing him of wanting to lose and imprison this agent. But Prieur denied these malicious claims so well, that Saint-Just didn’t dare to insist on it more. Instead, he turned again towards Carnot, whom he attacked with cruelty; several members of the Committee of General Security assisted. Niou was present for this scandalous scene: dismayed, he retired and feared to accept a pouder mission, a mission that could become, he said, a subject of accusation, since the patriots were busy destroying themselves in this way. We undoubtedly complained about this indecent attack, but was it necessary, at a time when there was not a grain of powder manufactured in Paris, to proclaim a division within the Committee of Public Safety, rather than to make known this fatal secret? In the midst of the most vague indictments and the most atrocious expressions uttered by Saint-Just, Carnot was obliged to repel them by treating him and his friends as aspiring to dictatorship and successively attacking all patriots to remain alone and gain supreme power with his supporters. It was then that Saint-Just showed an excessive fury; he cried out that the Republic was lost if the men in charge of defending it were treated like dictators; that yesterday he saw the project to attack him but that he defended himself. ”It’s you,” he added, ”who is allied with the enemies of the patriots. And understand that I only need a few lines to write for an act of accusation and have you guillotined in two days.”

”I invite you, said Carnot with the firmness that only appartient to virtue: I provoke all your severity against me, I do not fear you, you are ridiculous dictators.” The other members of the Committee insisted in vain several times to extinguish this ferment of disorder in the committee, to remind Saint-Just of the fairer ideas of his colleague and of more decency in the committee; they wanted to call people back to public affairs, but everything was useless: Saint-Just went out as if enraged, flying into a rage and threatening his colleagues. Saint-Just probably had nothing more urgent than to go and warn Robespierre the next day of the scene that had just happened, because we saw them return together the next day to the committee, around one o'clock: barely had they entered when Saint-Just, taking Robespierre by the hand, addressed Carnot saying: ”Well, here you have my friends, here are the ones you attacked yesterday!” Robespierre tried to speak of the respective wrongs with a very hypocritical tone: Saint-Just wanted to speak again and excite his colleagues to take his side. The coldness which reigned in this session, disheartened them, and they left the committee very early and in a good mood.

Réponse des membres des deux anciens Comités de salut public et de sûreté générale (Barère, Collot, Billaud, Vadier), aux imputations renouvellées contre eux, par Laurent Lecointre et declarées calomnieuses par décret du 13 fructidor dernier; à la Convention Nationale (1795), page 103-105

My friends, the committee has taken all the measures within its control at this time to support your zeal. It has asked me to write to you to explain the reasons for some of its provisions. It believed that the main cause of the last failure was the shortage of skilled generals, it will send you all the patriotic and educated soldiers that can be found. It thought it necessary at this time to re-use Stetenhofen, whom it is sending to you, because he has military merit, and because the objections made against him seem at least to be balanced by proofs of loyalty. He also relies on your wisdom and your energy. Salut et amitié.

Paris, 15 floréal, year 2 of the Republic.

Robespierre.

Robespierre to Saint-Just and Lebas, May 4 1793

Dear collegue,

Liberty is exposed to new dangers; the factions arise with a character more alarming than ever. The lines to get butter are more numerous and more turbulent than ever when they have the least pretexts, an insurrection in the prisons which was to break out yesterday and the intrigues which manifested themselves in the time of Hébert are combined with assassination attemps on several occasions against members of the Committee of Public Safety; the remnants of the factions, or rather the factions still alive, are redoubled in audacity and perfidy. There is fear of an aristocratic uprising, fatal to liberty. The greatest peril that threatens it is in Paris. The Committee needs to bring together the lights and energy of all its members. Calculate whether the army of the North, which you have powerfully contributed to putting on the path to victory, can do without your presence for a few days. We will replace you, until you return, with a patriotic representative.

The members composing the Committee of Public Safety.

Robespierre, Prieur, Carnot, Billaud-Varennes, Barère.

Letter to Saint-Just from the CPS, May 25 1794, written by Robespierre. It was penned down just two days after the alleged attempt on Robespierre’s life by Cécile Renault.

Robespierre returned to the Committee a few days later to denounce new conspiracies in the Convention, saying that, within a short time, these conspirators who had lined up and frequently dined together would succeed in destroying public liberty, if their maneuvers were allowed to continue unpunished. The committee refused to take any further measures, citing the necessity of not weakening and attacking the Convention, which was the target of all the enemies of the Republic. Robespierre did not lose sight of his project: he only saw conspiracies and plots: he asked that Saint-Just returned from the Army of the North and that one write to him so that he may come and strengthen the committee. Having arrived, Saint-Just asked Robespierre one day the purpose of his return in the presence of the other members of the Committee; Robespierre told him that he was to make a report on the new factions which threatened to destroy the National Convention; Robespierre was the only speaker during this session. He was met by the deepest silence from the Committee, and he leaves with horrible anger. Soon after, Saint-Just returned to the Army of the North, since called Sambre-et-Mouse. Some time passes; Robespierre calls for Saint-Just to return in vain: finally, he returns, no doubt after his instigations; he returned at the moment when he was most needed by the army and when he was least expected: he returned the day after the battle of Fleurus. From that moment, it was no longer possible to get him to leave, although Gillet, representative of the people to the army, continued to ask for him.

Réponse de Barère, Billaud-Varennes, Collot d’Herbois et Vadier aux imputations de Laurent Lecointre (1795)

On 10 messidor (June 28) I was at the Committee of Public Safety. There, I witnessed those who one accuses today (Billaud-Varenne, Barère, Collot-d'Herbois, Vadier, Vouland, Amar and David) treat Robespierre like a dictator. Robespierre flew into an incredible fury. The other members of the Committee looked on with contempt. Saint-Just went out with him.

Levasseur at the Convention, August 30 1794. If this scene actually took place, it must have done so one day later, 11 messidor (June 29), considering Saint-Just was still away on a mission on the tenth.

Isn’t it around the same time (a few days before thermidor) that Saint-Just and Lebas would dine at your father’s house with Robespierre?

Lebas often dined there, having married one of my sisters. Saint-Just rarely there, but he frequently went to Robespierre’s and climbed the stairs to his office without speaking to anyone.

During the dinner which I’m talking about, did you hear Saint-Just propose to Robespierre to reconcile with some members of the Convention and Committees who appeared to be opposed to him?

No. I only know that they appeared to be very devided.

Do you have any ideas what these divisions were about?

I only learned about it through the discussions which took place on this subject at the Jacobins and through the altercation which was said to have taken place at the Committee of Public Safety between Robespierre older and Carnot.

Robespierre’s host’s son Jacques-Maurice Duplay in an interrogation held January 1 1795

Saint-Just then fell back on his report, and said that he would join the committee the next day (9 thermidor) and that if it did not approve it, he would not read it. Collot continued to unmask Saint-Just; but as he focused more on depicting the dangers praying on the fatherland than on attacking the perfesy of Saint-Just and his accomplices, he gradually reassured himself of his confusion; he listened with composure, returning to his honeyed and hypocritical tone. Some time later, he told Collot d'Herbois that he could be reproached for having made some remarks against Robespierre in a café, and establishing this assertion as a positive fact, he admitted that he had made it the basis of an indictment against Collot, in the speech he had prepared.

Réponse des membres des deux anciens Comités de salut public et de sûrété générale… (1795) page 107.

I attest that Robespierre declared himself a firm supporter of the Convention and never spoke but gently in the Committee so as not to undermine any of its members. […] Billaud-Varenne said to Robespierre, “We are your friends, we have always walked together.” This dishonesty made my heart shudder. The next day, he called him Peisistratos and had written his act of accusation. […] If you reflect carefully on what happened during your last session, you will find the application of everything I said: a man alienated from the Committee due to the bitterest treatments, when this Committee was, in fact, no longer made up of more than the two or three members present, justified himself before you; he did not explain himself clearly enough, to tell the truth, but his alienation and the bitterness in his soul can excuse him somewhat: he does not know why he is being persecuted, he knows nothing except his misfortune. He has been called a tyrant of opinion: here I must explain myself and shine light on a sophism that tends to proscribe merit. And what exclusive right do you have to opinion, you who find that it is a crime to touch souls? Do you find it wrong that a man should be tenderhearted? Are you thus from the court of Philip, you who make war on eloquence? A tyrant of opinion? Who is stopping you from competing for the esteem of the fatherland, you who find it so wrong that someone should captivate it? There is no despot in the world, save Richelieu, who would be insulted by the fame of a writer. Is it a more disinterested triumph? Cato is said to have chased from Rome the bad citizen who had called eloquence at the tribune of harangues, the tyrant of opinion. No one has the right to claim that; it gives itself to reason and its empire is not the in the power of governments. […] The member who spoke for a long time yesterday at this tribune did not seem to have distinguished clearly enough who he was accusing. He had no complaints and has not complained either about the Committees; because the Committees still seem to me to be dignified of your estime, and the misfortunes that I have spoken to you of were born of isolation and the extreme authority of several members left alone.

Saint-Just defending Robespierre in his last, undelivered speech, July 27 1794

One brings St. Just, Dumas and Payan, all of them shackled, they are escorted by policemen. They stay a good quarter of an hour standing in front of the door of the Committee’s room; one makes them sit down onto a windowsill; they have still not uttered a single word, pleasant people make the persons who surround these three men step aside, and say move back, let these gentlemen see their King sleep on a table, just like a man. Saint-Just moves his head in order to see Robespierre. Saint-Just’s figure appeared dejected and humiliated, his swollen eyes expressed chagrin.

Faits recueillis aux derniers instants de Robespierre et de sa saction, du 9 au 10 thermidor (1794) by anonymous.

The Committee of General Security was being spied on by Héron, D…, Lebas: Robespierre knew, through them, word for word, everything that was happening at said committee. This espionage gave rise to more intimate connections between Couthon, Saint-Just and Robespierre. The fierce and ambitious character of the latter gave him the idea of establishing the general police bureau, which, barely conceived, was immediately decreed.

Révélations puisées dans les cartons des comités de Salut public et de Sûreté générale ou mémoires (inédits) (1824) by Gabriel Jérôme Sénart.

Intimately linked with Robespierre, [Saint-Just] had become necessary to him, and he had made himself feared perhaps even more than he had desired to be loved. One never saw them divided in opinion, and if the personal ideas of one had to bow to those of the other, it is certain that Saint-Just never gave in. Robespierre had a bit of that vanity which comes from selfishness; Saint-Just was full of the pride that springs from well-established beliefs; without physical courage, and weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets, he had the courage of reflection which makes one wait for certain death, so as not to sacrifice an idea.

Memoirs of René Levasseur (1829) volume 2, page 324-325.

Often [Robespierre] said to me that Camille was perhaps the one among all the key revolutionaries whom he liked best, after our younger brother and Saint-Just.

Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834) page 139.

After the month of March, 1794, Robespierre's conduct appeared to me to change. Saint-Just was to a great degree the cause of this, and this leader was too youthful ; he urged him into the vain and dangerous path of dictatorship which he haughtily proclaimed. From that time all confidences in the two committees were at an end, and the misfortunes that followed the division in the government became inevitable. […] We did not hide from [Robespierre] that Saint-Just, who was formed of more dictatorial stuff, would have ended by overturning him and occupying his place ; we knew too that he would have us guillotined because of our opposition to his plans; so we overthrew him.

Memoirs of Bertrand Barère (1896), volume 1, page 103-104.

About this time Robespierre felt his ambition growing, and he thought that the moment had come to employ his influence and take part in the government. He took steps with certain members of the committee and the Convention, asking them to show a desire that he, Robespierre, should become a member of the Committee of Public Safety. He told the Jacobins it would be useful to observe the work and conduct of the members of the committee, and he told the members of the Convention that there would be more harmony between the Convention and the committee if he entered it. Several deputies spoke to me about it, and the proposal was made to the committee by Couthon and Saint-Just. To ask was to obtain, for a refusal would have been a sort of accusation, and it was necessary to avoid any split during that winter which was inaugurated in such a sinister manner. The committee agreed to his admission, and Robespierre was proposed.

Ibid, volume 2, page 96-97

The continued victories of our fourteen armies were as a cloud of glory over our frontiers, hiding from allied Europe our internecine struggles, and that unhappy side of our national character which acts and reacts so deplorably as much on the whole population as on our nghts and our manners. The enthusiasm with which I announced these victories from the tnbune was so easily seen that Saint- Just and Robespierre, being in the committee at three in the morning, and learning of the taking of Namur and some other Belgian towns, insisted for the future that the letters alone of the generals should be read, without any comments which might exaggerate their contents. I saw at once at whom this reproach was directed, and I took up the gauntlet with the deasion of a man willing to once more merit the hatred of the enemies of our national glory, and the bravery of our armies. Then Samt-Just cried, “ I beg to move that Barère be no longer allowed to add froth to our victories.” […] While Saint-Just was reproving me, Robespierre supported the longsightedness of his friend… […] The next day my report on the taking of Namur was somewhat more carefully drawn up, and I alluded to the observation of my critics, who were envious of the power of public opinion in favour of our troops, then busied in saving the country. This phrase in my report was much commented on, although its meaning was only clear to those who had heard the debate in the committee on the previous evening “Sad are the tunes, sad is the period, when the recital of the triumphs and glories of the armies of the Repubhc is coldly hastened to in this place! Henceforth liberty will be no longer defended by the country, it will be handed over to its enemies!”This pronouncement was not of a nature to be forgiven by Saint-Just and Robespierre, so they determined to supplant me with regard to these reports. They forced that idiot Couthon to attend the Committee of Public Safety at eleven in the morning, before I got there Couthon asked for the letters of the generals that had come in during the night, and took his usual seat at the back of the hall, waiting until the assembly was sufficiently full for him to announce the victones. About one, Couthon, being paralysed and unable to stand up in the tribune, coldly read the news from the armies from his place. This time, no effect was produced in the Assembly, or upon the public. This attempt, authorised by Robespierre and Saint-Just, having missed fire completely, the committee signified its dissatisfaction at the innovation.

Ibid, volume 2, page 123-125

After his return from Fleurus, Saint-Just remained some time in Paris, although his mission as representative to the armies of the Sambre and Meuse and the Rhine and Moselle was unfinished. The campaign was only beginning, but he had several projects in hand, and he stayed in committee, or rather his office, where he was always absorbed and thoughtful. Robespierre, in speaking of him at the committee, said familiarly, as if speaking of an intimate friend: ”Saint-Just is silent and observant, but I have noticed, in his personality, he has a great likeness to Charles IX.” This did not flatter Saint-Just, who was a deeper and cleverer revolutionist than Robespierre. One day, when the former was angry about several legislative propositions or decrees that did not please him, Saint-Just said to him, “Be calm, it is the phlegmatic who govern.”

Ibid, volume 2, page 139

This tyrannical law was the work of Saint-Just Consult the Momteuv of the 22nd of Germinal, where it is reported with the explanation of his motives, and you will see that, if there had been no committee, SamtJust would have used his power with as much dictatorial fanaticism as did Manus, that great enemy of the Roman anstocracy. Robespierre’s fnend never forgave me for having dimmished the force of this blow. Whilst I was at the tnbune of the Convention, he came, with someone unknown, and perused my register of requisitions. He took down certain names, and some days after, towards midnight, Robespierre and Saint-Just entered the committee, where they did not usually come (for they worked in a private office, under pretext that their duties were completely private) A few moments after their entry Saint-Just complained of the abuse I had made of the requisitions, which had been granted, said he, in such profusion that the law of the 21st of Germinal had become null and void.

Ibid, volume 2, page 146

Robespierre, Saint-Just and Couthon were inseparable. The first two had a dark and duplicitous character; they pushed away with a kind of disdainful pride any familiarity or affectionate relationship with their colleagues. The third, a legless man with a pale appearance, affected good-nature, but was no less perfidious than the other two. All three of them had a cold heart, without pity, they interacted only with each other, holding mysterious meetings outside, having a large number of protégés and agents, impenetrable in their designs.

Révélations sur le Comité de salut public by Prieur-Duvernois

Robespierre, who had great confidence in Le Bas because he knew his wise and prudent character well, had chosen him to accompany Saint-Just, whose burning love of the fatherland sometimes led to too much severity, and who had a tendency to get carried away. […] [Saint-Just] also had friendship for me and came often enough to our house. […] Finally our providence, our good friend Robespierre, spoke to Saint-Just to engage him to let me depart with them, along with my sister-in-law Henriette. He consented, but with some conditions.

Memoirs of Élisabeth Lebas (1901)

Volume 8 — page 153. ”Saint-Just, his (Robespierre’s) only confident.” His only confident?

Élisabeth Lebas corrects a passage in Alphonse de Lamartine’s Histoire des Girondins (1847)

The Lamenths and Péthion in the early days, quite rarely Legendre, Merlin de Thionville and Fouché, often Taschereau, Desmoulins and Teault, always Lebas, Saint-Just, David, Couthon and Buonarotti.

Élisabeth Lebas regarding visitors to the Duplay’s during the revolution

—

When arriving in Paris in September 1792, Saint-Just first lived on No. 7 rue de Gaillon up until March 1794, and then on No. 3 rue de Caumartin (today’s No. 5) up until his death. Both those places were within a ten minute walking distance from Robespierre’s home on 398 Rue Saint-Honoré.

Saint-Just was away from Paris (and therefore Robespierre) on missions between March 9 to March 31, October 17 to December 4, December 10 to December 30 (1793), January 22 to February 13, April 30 to May 31 and June 10 to June 29 (1794).

#sj and max holding hands 🤗💓#robespierre#saint-just#maximilien robespierre#louis antoine de saint just#barère#élisabeth lebas#philippe lebas#frev#frev friendships#long post#saintspierre

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roi (Thorin Écu-de-Chêne, roi du Peuple de Durin et roi sous la Montagne) / King (Thorin Oakenshield, king of Durin's Folk and king under the Moutain) (Tolktober, 28), 2023, encre de Chine sur papier, 21,5 x 14 cm

#art#Tolktober#Tolktober 2023#dessin#drawing#encre#ink#encre de Chine#indian ink#Tolkien#Bilbo le Hobbit#The Hobbit#roi#king#Thorin Oakenshield#Erebor#dwarf#nain#ce Tolktober manquait de nains

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marat's critique on scientific academies

"Even though the following letter does not come from the same quill, I felt obliged to include it here anyway, because it reveals some piquant facts that are perfect to show the uselessness of scientific societies and to reveal the shameless charlatanism of their members."

Letter XII

"It is not true, Monsieur, that the academies have never made some discoveries, although their members have often stolen those of others. On the subject, I could mention one hundred traits of infidelity of Messrs. the academicians of Paris; one hundred cases of misuse of funds; one hundred inventions publicly claimed by their authors, and what is even stranger, one hundred mémoirs that have been made to disappear and then carelessly published again under the names of these shameful plagiarists, but I do not want to demoralise you. Thus, I will limit myself to clear your doubts with two anecdotes that you will find amusing and of which you can find proof easily, since they happened before our very eyes.

You remember the enthusiasm about the rise of the first aerostatic globe and the craze of the public for this kind of exhibition. You remember the wonderful discoveries, of which this new experience was the source; you also remember the multiple as well as vain attempts done to steer the balloons. Well? Some fools, who believe that genius resides in the Academy of Science, gave it twelve thousand livres to figure out a way to control [the balloons]. What happened to that money? Do you think it reached its destination? Do not fool yourself. Do you think it was used for some useful research? How naive you are. Just know that our savants shared it among themselves and that it was all squandered at the Rapée, at the Opera and with women. You blush for them, but this is just a small thing, listen to this other bolder courtesy of theirs.

Some months ago, a deputy, prompted by the work of an author, proposed in the National Assembly to proclaim the equality of weights and measures through all the reign. The proposal was well received and sent to the Academy of Science in order to decide how to proceed. It only took them the time to puff themselves up, to put their scribes to work and to rush to the senate that Messrs. the scientists were ready to announce that the Academy had found the best method to fulfil the expectations of the Assembly. It was to derive all the measures from the one of the circumference of the terrestrial globe; a method that some venal quills have immediately presented as a superb discovery by our doctors. But where do you think that this sublime method comes from? From the Egyptians. It was to pass it on to future centuries that the famous pyramids were built, which many clueless travellers took for eternal monuments of the greatness of these people. Eh! And where do you think that our academicians took this magnificent system from? They took it word for word from the treatise on weights and measures of the Ancients, published by Romé de l’Îsle, a distinguished savant, whose name they have taken care to overshadow since his death, in order to steal from him, after having persecuted him his whole life. But the best is yet to come. Under the pretext to measure a degree of the meridian arc - already well determined by the ancients and of which it would be impossible today to alter the measure without overthrowing this admirable system - they have been granted by the minister one hundred thousand écus for the expenses of the operation; a gâteau that they will share among their associates.

Judge for yourself the usefulness of the academies and the virtue of their members. The academies of the capital, which have never done anything for the progress of human knowledge other than persecute true men of genius; those will be preserved by conscript fathers, for the fact that the nation is in charge of [the academies] and that they consist of vile supporters of the despot, pavid advocates of despotism."

—from Jean-Paul Marat's "Les charlatans modernes ou lettres sur le charlatanisme académique", letter n° 12, p. 40

Highlights in italics are mine. I thank @pleasecallmealsip for helping me with a couple of words I didn't know how to translate.

#spoiler: the “prompting” plagiarist author is Talleyrand#marat#jean paul marat#frev#french revolution#metric system#history of science#rome de l'isle#my translations

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ph. La bouquiniste

Paroles à la lune

La lune, dites-nous si c'est votre plaisir,

Ô lune cajoleuse !

Que les hommes se plient au gré de vos désirs

Comme la mer houleuse,

Est-ce votre vouloir que ceux qui tout le jour

Furent doux et tranquilles,

Succombent dans le soir au péché de l'amour

Par les champs et les villes ?

Les baisers montent-ils vers vous comme de l'eau

Qui se volatilise,

Pour faire, à votre front vaniteux, ce halo

Dont sa pâleur s'irise ?

Est-ce pour vous séduire ou vous désennuyer,

Quand vous faites la moue,

Que les hommes s'en vont se pendre ou se noyer,

La lune aux belles joues ?

Brillez-vous pour que ceux qui marchent sans souliers,

Sans joie et sans pécune,

Aient, sur les durs chemins, des rayons à leurs pieds

Pendant vos clairs de lune ?

Dans les coeurs délaissés, dans les coeurs indigents

Qui battent par le monde,

Vous laissez-vous tomber comme un écu d'argent,

Parfois, ô lune ronde ?

Ô lune qui le soir venez boire aux étangs

Et vous coucher dans l'herbe,

Quel mal a pu troubler, d'un désir haletant,

Votre langueur superbe ?

C'est d'avoir vu le bouc irrévérencieux

Et la chèvre amoureuse

S'unir dans la nuit claire, et réveiller les cieux

De leur clameur heureuse ;

C'est d'avoir vu Daphnis s'approcher sans détour

De Chloé favorable…

C'est de sentir monter cette odeur de l'amour,

Ô lune inviolable !

Anna de Noailles

Pleine lune dans le capricorne cette nuit justement on en profite pour y voir clair... ;-) *

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soult enlists in the army

This now is for @flowwochair: another rather long passage translated from A. Combes, "Histoire anecdotique de Jean de dieu Soult". Combes tells the story of how Soult came to join the army, and that of the friend he enlisted with. We start off at the point when Soult's first tutor had just sent his rebellious apprentice home.

Mme Soult did not want to settle for this initial attempt. She attributed its failure to various causes: she suspected the bad influences of a larger, richer, more pleasure-loving locality than the sad village of Saint-Amans; she perhaps blamed her son's relations with new friends who were dissipated or lazy; and, looking for a remedy for these inconveniences, she hoped to find it by forcing the apprentice to continue his studies with a businessman in Saint-Baudille. Of course, there was never a better place to protect someone from overly stimulating acquaintances or overly exaggerated distractions. This small hamlet, wretched in appearance, wretched in production, with no large population, the central point of a very poor parish, was an almost isolated residence. There was certainly nothing better than this place for learning to stay at home, for distracting oneself by copying documents, for learning to overcome boredom through work.

Jean-de-Dieu Soult tried this last method for a few months. His boss did not give him any credit. He was a hard, stern man, as rough as the country he lived in, demanding and taciturn. Often he would simply point to the work to be done, tearing it apart brutally when something was found lacking. He never gave him the slightest encouragement, and all he got as payment was food that was crude, poorly prepared and not very plentiful. Thus passed the first months of the winter, not without a few heated altercations between master and pupil. But one day in February, the latter having been locked up, with notebooks to transcribe, in a small room with no fire, poor lighting, with no furniture other than a bench and a table, next to a window with no frame from which the slope of the Saint-Amans mountain could be seen in the distance, a moment of despair seized him. Rising with rage, he climbed through the small opening onto a snow-covered roof; he jumped down, running as fast as he could towards his mother's house, where he arrived freezing cold and famished.

Now, here's what was happening in this house. For three days it had been occupied by garrisoners, who had come to collect the tax, which the harshness of the season, following a poor harvest, made it impossible to pay. No sooner had Jean-de-Dieu Soult been made aware of this disastrous situation than his mind was made up. He embraced his mother without saying a word, left the house, went to the village, took with him one of his comrades, whose inclinations he knew, and, making his way along the usually impassable paths, at that moment clogged with snow, he went with him to the Château de Larembergue. There was a young captain of the Royal Infantry regiment, responsible for recruiting volunteers.

The conditions were soon established; they were carried out immediately, on the one hand, by the signature of Jean-de-Dieu Soult (the comrade could not write) affixed to the bottom of a sheet of paper; on the other hand, by the delivery into his hands of ten écus. He hurried back to St-Amans to give the money in full to his mother. It was used to relieve her of the seizure of her furniture and to dismiss the guards. […]

He left, taking with him this comrade whose vocation, even more than his own, had been determined by need. They both joined the Royal Infantry, which was then at Saint-Jean-d'Angely. They spent two years there. Jean-de-Dieu Soult was successively made corporal and sergeant. How did he reach these ranks? The story of the comrade will tell us; it is curious enough, although very short, to serve as an episode in that of the Marshal.

Around 1820, after his exile, the latter had returned to Saint-Amans. He tried to make himself forgotten; he wrote or dictated his memoirs; that was all the part he played in public life. However, during the long winter evenings, sitting in his living room, surrounded by several relatives, looking for his old friends, he loved to reminisce about the early years of his life. He was very happy to let himself be told trivial things or personal facts about the inhabitants of Saint-Amans and the surrounding area. He asked a lot of questions, but didn't always answer; but he seemed to take a particular interest in the changes that had taken place in people and things in his country.

One day while he was engaged in this kind of investigation, the conversation turned to the fate of a poor devil for whom the assistance of Mlle Soult, his sister, was being sought.

This man was alone in the world; he struggled to make a living by farming, which he always did rather badly due to lack of habit. The Marshal asked for information on the matter. He had fought as a soldier in all the campaigns of the Republic and the Empire; he had returned to his home (what a derisory word!) after the events of 1814; since then he had lived on alms.

He was summoned, questioned, assisted and finally placed in charge of cleaning the paths in the garden of the Hôtel du Maréchal, rue de l'Université, in Paris. A few years later, the Mayor of Saint-Amans found him there, and they had the following conversation:

- There you are, Laporte.... That was his surname, but he didn't seem to know it; he was more naturally responding to a nickname in the local dialect that he had brought back from Saint-Amans.

- Oui, Monsieur.

- So you don't know me?

- Well, no.

- I'm the Mayor of your village, Monsieur Calvet.

- The Mayor! Monsieur Calvet! That may well be.

- And the Marshal; are you happy with him?

- The Corporal you mean; oh, I can't complain about that; 20 sous a day, the bed, the table.... I don't ask for more.

- And do you remember when you were soldiers together?

- Oh yes! He really got on my nerves then too.

- Why should that be?

- He was, you see, serving quite badly; always in bed with books; sometimes writing on his knees with a pen or pencil; often walking and talking alone; never failing to go and see the smallest review, even that of the other regiments.... And, all the while, I was his roommate, obliged, for a few pennies he gave me, to shine his shoes, brush his clothes, make his queue (we wore it in those days) and clean his rifle.... You can believe it, he was a very bad soldier.

- But today?

- Oh, today the corporal is very kind; he never comes here without saying to me: Have you got any tobacco? I always answer: No. - Here's twenty sous to buy some.

- So you're happy?

- I am! but if we were still fighting, I'd soon have left these bad tools here and gone back to the old ones....

That's Laporte's story in a nutshell: he had left as a soldier, he had returned as a soldier; he had fought for thirty years and he hadn't died; he was one of those who had shaken the old monarchies, and now he was raking alleys.

And without his former "corporal", he would not even have that ... On first reading, I was quite disappointed that Soult was not doing more for this very first comrade of his. But I guess he stubbornly adhered to the principle that you have to work for your place in life. Soult had put in that extra work, as much as he could, by reading those books in bed and studying what he needed to know for a promotion.

Considering that the intellectual capacities of this man seem to be rather limited, this job also may have just been best for Monsieur Laporte?

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fairytale #2 - Donkey skin

Once upon a time, there was a King, so great, so beloved by his people, and so respected by all his neighbours and allies that one might almost say he was the happiest monarch alive. His good fortune was made even greater by the choice he had made for wife of a Princess as beautiful as she was virtuous, with whom he lived in perfect happiness. Now, of this chaste marriage was born a daughter endowed with so many gifts that they had no regret because other children were not given to them.

Il était une fois un roi si grand, si aimé de ses peuples, si respecté de tous ses voisins et de ses alliés, qu'on pouvait dire qu'il était le plus heureux de tous les monarques. Son bonheur était encore confirmé par le choix qu'il avait fait d'une princesse aussi belle que vertueuse; et ces heureux époux vivaient dans une union parfaite. De leur chaste hymen était née une fille, douée de tant de grâces et de charmes, qu'ils ne regrettaient pas de n'avoir pas une plus ample lignée.

Magnificence, taste and abundance reigned in his palace; the ministers were wise and skilful; the courtiers, virtuous and attached; the servants, faithful and industrious; the stables, vast and filled with the most beautiful horses in the world, covered with rich caparison: but what astonished the foreigners who came to admire these beautiful stables, was that in the most apparent place a master donkey displayed long and large ears.

It was not by fancy, but with reason, that the king had given him a special and distinguished place. The virtues of this rare animal deserved this distinction, since nature had formed him so extraordinary, that his litter, instead of being unclean, was covered, every morning, with profusion, with beautiful gold coins in the sun, and with golden louis of all kinds, which one would collect when he woke up.

La magnificence, le goût et l'abondance régnaient dans son palais; les ministres étaient sages et habiles; les courtisans, vertueux et attachés; les domestiques, fidèles et laborieux; les écuries, vastes et remplies des plus beaux chevaux du monde, couverts de riches caparaçons : mais ce qui étonnait les étrangers qui venaient admirer ces belles écuries, c'est qu'au lieu le plus apparent un maître âne étalait de longues et grandes oreilles.

Ce n'était pas par fantaisie, mais avec raison, que le roi lui avait donné une place particulière et distinguée. Les vertus de ce rare animal méritaient cette distinction, puisque la nature l'avait formé si extraordinaire, que sa litière, au lieu d'être malpropre, était couverte, tous les matins, avec profusion, de beaux écus au soleil, et de louis d'or de toute espèce, qu'on allait recueillir à son réveil.

Now, as the vicissitudes of life extend to kings as well as to subjects, and as good things are always mixed with some ills, heaven allowed that the queen was suddenly attacked by a bitter illness, for which, in spite of the science and skill of the physicians, no help could be found. The desolation was general. The king, sensitive and in love, in spite of the famous proverb which says that the hymen is the tomb of love, afflicted himself without moderation, made ardent vows to all the temples of his kingdom, offered his life for that of so dear a wife; but the gods and the fairies were invoked in vain. The queen, feeling that her last hour was approaching, said to her husband, who was bursting into tears: "Find it good, before I die, that I demand one thing of you: that if you should have the desire to remarry…"

Or, comme les vicissitudes de la vie s'étendent aussi bien sur les rois que sur les sujets, et que toujours les biens sont mêlés de quelques maux, le ciel permit que la reine fût tout à coup attaquée d'une âpre maladie, pour laquelle, malgré la science et l'habileté des médecins, on ne put trouver aucun secours. La désolation fut générale. Le roi, sensible et amoureux, malgré le proverbe fameux qui dit que l'hymen est le tombeau de l'amour, s'affligeait sans modération, faisait des voeux ardents à tous les temples de son royaume, offrait sa vie pour celle d'une épouse si chère; mais les dieux et les fées étaient invoqués en vain. La reine, sentant sa dernière heure approcher, dit à son époux qui fondait en larmes : « Trouvez bon, avant que je meure, que j'exige une chose de vous : c'est que s'il vous prenait envie de vous remarier... »

At these words the king gave a pitiful cry, took his wife's hands, bathed them in tears, and, assuring her that it was superfluous to speak to her of a second hymenae: "No, no," he said at last, "my dear queen, speak to me rather of following you;" "The State," resumed the queen, with a firmness which increased the regrets of this prince, "the State must demand successors, and, as I have only given you a daughter, press you to have sons like yourself: But I urge you, by all the love you have had for me, not to yield to the eagerness of your people until you have found a princess more beautiful and better made than I; I want your oath, and then I shall die content. "

À ces mots, le roi fit des cris pitoyables, prit les mains de sa femme, les baigna de pleurs, et, l'assurant qu'il était superflu de lui parler d'un second hyménée : « Non, non, dit-il enfin, ma chère reine, parlez-moi plutôt de vous suivre; - L'État, reprit la reine avec une fermeté qui augmentait les regrets de ce prince, l'État, doit exiger des successeurs, et, comme je ne vous ai donné qu'une fille, vous presser d'avoir des fils qui vous ressemblent : mais je vous demande instamment, par tout l'amour que vous avez eu pour moi, de ne céder à l'empressement de vos peuples que lorsque vous aurez trouvé une princesse plus belle et mieux faite que moi; j'en veux votre serment, et alors je mourrai contente. »

It is presumed that the queen, who was not lacking in self-respect, had demanded this oath, not believing that there was anyone in the world who could match her, thinking that it was to ensure that the king would never remarry. Finally she died. No husband ever made so much fuss: weeping, sobbing day and night, the small rights of widowhood, were her only occupation.

On présume que la reine, qui ne manquait pas d'amour-propre, avait exigé ce serment, ne croyant pas qu'il fût au monde personne qui pût l'égaler, pensant bien que c'était s'assurer que le roi ne se remarierait jamais. Enfin elle mourut. Jamais mari ne fit tant de vacarme : pleurer, sangloter jour et nuit, menus droits du veuvage, furent son unique occupation.

The great pains did not last. Moreover, the great men of the State assembled, and came in body to beg the king to remarry. This first proposal seemed harsh to him, and made him shed new tears. He alleged the oath he had made to the queen, challenging all his advisers to find a princess more beautiful and better made than his late wife, thinking it impossible. But the council treated such a promise as mere bauble, and said that it did not matter how beautiful she was, so long as a queen was virtuous and not barren; that the state required princes for its rest and tranquillity; that indeed the infanta had all the qualities required to make a great queen, but that a stranger should be chosen for her husband; and that either this stranger would take her home with him, or that, if he reigned with her, her children would no longer be reputed to be of the same blood; and that, as there was no prince of her name, the neighbouring peoples might raise wars against them which would lead to the ruin of the kingdom.

Les grandes douleurs ne durent pas. D'ailleurs, les grands de l'État s'assemblèrent, et vinrent en corps prier le roi de se remarier. Cette première proposition lui parut dure, et lui fit répandre de nouvelles larmes. Il allégua le serment qu'il avait fait à la reine, défiant tous ses conseillers de pouvoir trouver une princesse plus belle et mieux faite que feu sa femme, pensant que cela était impossible. Mais le conseil traita de babiole une telle promesse, et dit qu'il importait peu de la beauté, pourvu qu'une reine fût vertueuse et point stérile; que l'État demandait des princes pour son repos et sa tranquillité; qu'à la vérité l'infante avait toutes les qualités requises pour faire une grande reine, mais qu'il fallait lui choisir un étranger pour époux; et qu'alors, ou cet étranger l'emmènerait chez lui, ou que, s'il régnait avec elle, ses enfants ne seraient plus réputés du même sang; et que, n'y ayant point de prince de son nom, les peuples voisins pourraient leur susciter des guerres qui entraîneraient la ruine du royaume.

The king, struck by these considerations, promised that he would think of satisfying them. Indeed, he looked for a suitable bride among the princesses to be married. Every day charming portraits were brought to him, but none of them had the graces of the late queen: so he did not make up his mind. Unfortunately, he found that the infanta, his daughter, was not only beautiful and well-made, but that she far surpassed the queen her mother in spirit and amenities. Her youth and the pleasant freshness of her beautiful complexion inflamed the king with such a violent fire that he could not hide it from the infanta, and he told her that he had resolved to marry her, since she alone could release him from his oath.

Le roi, frappé de ces considérations, promit qu'il songerait à les contenter. Effectivement il chercha, parmi les princesses à marier, que serait celle qui pourrait lui convenir. Chaque jour on lui apportait des portraits charmants, mais aucun n'avait les grâces de la feue reine : ainsi il ne se déterminait point. Malheureusement, il s'avisa de trouver que l'infante, sa fille, était non seulement belle et bien faite à ravir, mais qu'elle surpassait encore de beaucoup la reine sa mère en esprit et en agréments. Sa jeunesse, l'agréable fraîcheur de son beau teint enflamma le roi d'un feu si violent, qu'il ne put le cacher à l'infante, et il lui dit qu'il avait résolu de l'épouser, puisqu'elle seule pouvait le dégager de son serment.

The young princess, full of virtue and modesty, thought she would faint at this horrible proposal. She threw herself at the feet of her father the king, and begged him, with all the strength she could muster in her mind, not to force her to commit such a crime.

La jeune princesse, remplie de vertu et de pudeur, pensa s'évanouir à cette horrible proposition. Elle se jeta aux pieds du roi son père, et le conjura, avec toute la force qu'elle put trouver dans son esprit, de ne la pas contraindre à commettre un tel crime.

The king, who had set himself this strange project in mind, had consulted an old druid to put the princess' conscience at rest. This druid, who was not so much religious as ambitious, sacrificed the interests of innocence and virtue to the honour of being a confidant of a great king, and so skilfully insinuated himself into the king's mind, so softened the crime he was about to commit, that he even persuaded him that it was a pious act to marry his daughter. The prince, flattered by the speeches of this scoundrel, embraced him, and returned from him more stubborn than ever in his project: he, therefore, ordered the infanta to prepare herself to obey him.

Le roi, qui s'était mis en tête ce bizarre projet, avait consulté un vieux druide pour mettre la conscience de la princesse en repos. Ce druide, moins religieux qu'ambitieux, sacrifia, à l'honneur d'être confident d'un grand roi, l'intérêt de l'innocence et de la vertu, et s'insinua avec tant d'adresse dans l'esprit du roi, lui adoucit tellement le crime qu'il allait commettre, qu'il lui persuada même que c'était une oeuvre pie que d'épouser sa fille. Ce prince, flatté par les discours de ce scélérat, l'embrassa, et revint d'avec lui plus entêté que jamais dans son projet : il fit donc ordonner à l'infante de se préparer à lui obéir.

The young princess, outraged by the pain, thought of nothing else but to go and find the Lilac Fairy, her godmother. For this purpose, she set off that same night in a pretty cabriolet harnessed to a big sheep that knew all the roads. She arrived happily. The fairy, who loved the infanta, told her that she knew everything she had come to tell her, but that she had no worries, as nothing could harm her if she faithfully carried out what she was going to tell her. "For, my dear child," she said to her, "it would be a great fault to marry your father; but, without contradicting him, you can avoid it: tell him that, to fulfil a fancy you have, he must give you a dress of the colour of the time; never, with all his love and power, can he succeed."

La jeune princesse, outrée d'une vive douleur, n'imagina rien autre chose que d'aller trouver la fée des Lilas, sa marraine. Pour cet effet elle partit la même nuit dans un joli cabriolet attelé d'un gros mouton qui savait tous les chemins. Elle y arriva heureusement. La fée, qui aimait l'infante, lui dit qu'elle savait tout ce qu'elle venait lui dire, mais qu'elle n'eût aucun souci, rien ne pouvant lui nuire si elle exécutait fidèlement ce qu'elle allait lui prescrire. « Car, ma chère enfant, lui dit-elle, ce serait une grande faute que d'épouser votre père; mais, sans le contredire, vous pouvez l'éviter : dites-lui que, pour remplir une fantaisie que vous avez, il faut qu'il vous donne une robe de la couleur du temps; jamais, avec tout son amour et son pouvoir, il ne pourra y parvenir. »

The princess thanked her godmother well; and the next morning she told the king her father what the fairy had advised her to do, and protested that no confession would be made of her unless she had a dress the colour of the time. The king, delighted with the hope she gave him, assembled the most famous workmen and ordered them to make the dress, on condition that if they failed to do so, he would have them all hanged. He did not have the sorrow to come to this extremity; from the second day, they brought the dress so desired. The empyrean is no more beautiful blue when it is girded with golden clouds than this beautiful dress when it was laid out. The infanta was very upset by this, and did not know how to get out of her predicament. The king was pressing for a conclusion. The godmother had to be called in again and, astonished that her secret had not succeeded, told her to try to ask for one the colour of the moon. The king, who could refuse her nothing, sent for the most skilful workmen, and so expressly ordered them to make a dress the colour of the moon, that there were not twenty-four hours between the order and its delivery…

La princesse remercia bien sa marraine; et dès le lendemain matin elle dit au roi son père ce que la fée lui avait conseillé, et protesta qu'on ne tirerait d'elle aucun aveu qu'elle n'eût une robe couleur du temps. Le roi, ravi de l'espérance qu'elle lui donnait, assembla les plus fameux ouvriers, et leur commanda cette robe, sous la condition que, s'ils ne pouvaient réussir, il les ferait tous pendre. Il n'eut pas le chagrin d'en venir à cette extrémité; dès le second jour ils apportèrent la robe si désirée. L'empyrée n'est pas d'un plus beau bleu lorsqu'il est ceint de nuages d'or, que cette belle robe lorsqu'elle fut étalée. L'infante en fut toute contristée, et ne savait comment se tirer d'embarras. Le roi pressait la conclusion. Il fallut recourir encore à la marraine, qui, étonnée de ce que son secret n'avait pas réussi, lui dit d'essayer d'en demander une de la couleur de la lune. Le roi, qui ne pouvait lui rien refuser, envoya chercher les plus habiles ouvriers, et leur commanda si expressément une robe couleur de la lune, qu'entre ordonner et l'apporter il n'y eut pas vingt-quatre heures...

The infanta, more enchanted by this superb dress than by the care of the king her father, became immoderately distressed when she was with her wives and nurse. The Lilac Fairy, who knew everything, came to the aid of the afflicted princess, and said to her: "Either I am very much mistaken, or I believe that, if you ask for a dress the colour of the sun, we shall either succeed in disgusting the king your father, for it will never be possible to make such a dress, or we shall at least gain time.

L'infante, plus charmée de cette superbe robe que des soins du roi son père, s'affligea immodérément lorsqu'elle fut avec ses femmes et sa nourrice. La fée des Lilas, qui savait tout, vint au secours de l'affligée princesse, et lui dit : « Ou je me trompe fort, ou je crois que, si vous demandez une robe couleur du soleil, ou nous viendrons à bout de dégoûter le roi votre père, car jamais on ne pourra parvenir à faire une pareille robe, ou nous gagnerons au moins du temps. »

The infanta agreed, asked for the dress, and the loving king gave, without regret, all the diamonds and rubies in his crown to help with this superb work, with orders to spare nothing to make this dress equal to the sun. And so, as soon as it appeared, all those who saw it unfurled were forced to close their eyes, so dazzled were they. It was from this time that green glasses and black lenses were introduced. What happened to the infanta at this sight? Never had anyone seen anything so beautiful and so artistically worked. She was confounded; and under the pretext of having a sore eye, she retired to her room, where the fairy was waiting for her, more ashamed than one can say. It was much worse: for, on seeing the sun's dress, she turned red with anger. Oh, now, my daughter," she said to the infanta, "we shall put your father's unworthy love to a terrible test. I think he is very stubborn about this marriage which he believes to be so near, but I think he will be a little dizzy at the request I advise you to make to him: it is the skin of that donkey which he loves so passionately, and which provides for all his expenses with such profusion; go, and do not fail to tell him that you desire this skin.

L'infante en convint, demanda la robe, et l'amoureux roi donna, sans regret, tous les diamants et les rubis de sa couronne pour aider à ce superbe ouvrage, avec ordre de ne rien épargner pour rendre cette robe égale au soleil. Aussi, dès qu'elle parut, tous ceux qui la virent déployée furent obligés de fermer les yeux, tant ils furent éblouis. C'est de ce temps que date les lunettes vertes et les verres noirs. Que devint l'infante à cette vue ? Jamais on n'avait rien vu de si beau et de si artistement ouvré. Elle était confondue; et sous prétexte d'avoir mal aux yeux, elle se retira dans sa chambre, où la fée l'attendait, plus honteuse qu'on ne peut dire. Ce fut bien pis : car, en voyant la robe du soleil, elle devint rouge de colère. « Oh ! pour le coup, ma fille, dit-elle à l'infante, nous allons mettre l'indigne amour de votre père à une terrible épreuve. Je le crois bien entêté de ce mariage qu'il croit si prochain, mais je pense qu'il sera un peu étourdi de la demande que je vous conseille de lui faire : c'est la peau de cet âne qu'il aime si passionnément, et qui fournit à toutes ses dépenses avec tant de profusion; allez, et ne manquez pas de lui dire que vous désirez cette peau. »

The infanta, delighted to find yet another way of evading a marriage she hated, and who thought at the same time that her father could never bring himself to sacrifice his donkey, came to him and explained her desire for the skin of this beautiful animal. Although the king was astonished at this fantasy, he did not hesitate to satisfy it. The poor donkey was sacrificed, and the skin gallantly brought to the infanta, who, seeing no way of evading her misfortune, was about to despair, when her godmother came running. What are you doing, my daughter?" she said, seeing the princess tearing her hair and bruising her beautiful cheeks; "this is the happiest moment of your life. Wrap yourself in this skin; leave this palace, and go as far as the earth will carry you: when one sacrifices everything to virtue, the gods know how to reward it. Go, I will take care that your toilet follows you everywhere; wherever you stop, your cassette, where your clothes and jewels will be, will follow your steps under the ground; and here is my wand which I give you: by striking the ground, when you need this cassette, it will appear to your eyes; but make haste to leave; and do not delay.

L'infante, ravie de trouver encore un moyen d'éluder un mariage qu'elle détestait, et qui pensait en même temps que son père ne pourrait jamais se résoudre à sacrifier son âne, vint le trouver, et lui exposa son désir pour la peau de ce bel animal. Quoique le roi fût étonné de cette fantaisie, il ne balança pas à la satisfaire. Le pauvre âne fut sacrifié, et la peau galamment apportée à l'infante, qui, ne voyant plus aucun moyen d'éluder son malheur, s'allait désespérer, lorsque sa marraine accourut. « Que faites-vous, ma fille ? dit-elle, voyant la princesse déchirant ses cheveux et meurtrissant ses belles joues; voici le moment le plus heureux de votre vie. Enveloppez-vous de cette peau; sortez de ce palais, et allez tant que terre pourra vous porter : lorsqu'on sacrifie tout à la vertu, les dieux savent en récompenser. Allez, j'aurai soin que votre toilette vous suive partout; en quelque lieu que vous vous arrêtiez, votre cassette, où seront vos habits et vos bijoux, suivra vos pas sous terre; et voici ma baguette que je vous donne : en frappant la terre, quand vous aurez besoin de cette cassette, elle paraîtra à vos yeux; mais hâtez-vous de partir; et ne tardez pas. »

The infanta kissed her godmother a thousand times, begged her not to abandon her, put on that ugly skin, after smearing herself with chimney soot, and left the rich palace without being recognised by anyone.

The absence of the infanta caused a great rumour. The king, in despair, who had had a magnificent party prepared, was inconsolable. He sent out more than a hundred gendarmes and more than a thousand musketeers to search for his daughter; but the fairy, who protected her, made her invisible to the most skilful searchers: so it was necessary to console himself.

L'infante embrassa mille fois sa marraine, la pria de ne pas l'abandonner, s'affubla de cette vilaine peau, après s'être barbouillée de suie de cheminée, et sortit de ce riche palais sans être reconnue de personne.

L'absence de l'infante causa une grande rumeur. Le roi, au désespoir, qui avait fait préparer une fête magnifique, était inconsolable. Il fit partir plus de cent gendarmes et plus de mille mousquetaires pour aller à la quête de sa fille; mais la fée, qui la protégeait, la rendait invisible aux plus habiles recherches : ainsi il fallut bien s'en consoler.

In the meantime, the infanta was on her way. She went far, far, farther, and looked everywhere for a place to stay; but although they gave her food out of charity, they found her so filthy that no one wanted her. However, she entered a beautiful town, at the gate of which was a farmhouse, whose farmer needed a sloven to wash the dishcloths, clean the turkeys and the pigs' trough. This woman, seeing this traveller so dirty, offered to let her into her house; which the infanta accepted with a great deal of pleasure, so tired was she of having walked so much. They put her in a back corner of the kitchen, where for the first few days she was the butt of the coarse jokes of the flunkeys, so dirty and disgusting was her donkey skin. At last, they got used to her; besides, she was so careful to fulfil her duties that the farmer took her under her protection. She drove the sheep and had them parked when they needed to be; she led the turkeys to graze with such intelligence that it seemed as if she had never done anything else: everything bore fruit under her beautiful hands.

Pendant ce temps l'infante cheminait. Elle alla bien loin, bien loin, encore plus loin, et cherchait partout une place; mais quoique par charité on lui donnât à manger, on la trouvait si crasseuse que personne n'en voulait. Cependant elle entra dans une belle ville, à la porte de laquelle était une métairie, dont la fermière avait besoin d'une souillon pour laver les torchons, nettoyer les dindons et l'auge des cochons. Cette femme, voyant cette voyageuse si malpropre, lui proposa d'entrer chez elle; ce que l'infante accepta de grand coeur, tant elle était lasse d'avoir tant marché. On la mit dans un coin recule de la cuisine, où elle fut, les premiers jours, en butte aux plaisanteries grossières de la valetaille, tant sa peau d'âne la rendait sale et dégoûtante. Enfin on s'y accoutuma; d'ailleurs elle était si soigneuse de remplir ses devoirs que la fermière la prit sous sa protection. Elle conduisait les moutons, les faisait parquer au temps où il le fallait; elle menait les dindons paître avec une telle intelligence, qu'il semblait qu'elle n'eût jamais fait autre chose : aussi tout fructifiait sous ses belles mains.

One day, sitting by a clear fountain, where she often deplored her sad condition, she thought of taking a look at herself, but the appalling donkey skin which made up her hair and clothing appalled her. Ashamed of this adjustment, she cleaned her face and hands, which became whiter than ivory, and her beautiful complexion regained its natural freshness. The joy of finding herself so beautiful made her want to bathe in it, which she did: but she had to put on her unworthy skin to return to the farm. Fortunately, the next day was a feast day; so she had time to draw out her cassette, to arrange her toilet, to powder her beautiful hair, and to put on her beautiful dress the colour of the time. Her room was so small that the tail of this beautiful dress could not stretch. The beautiful princess wondered and admired herself with good reason, so that she resolved, in order to relieve herself, to put on her beautiful dresses in turn, on festivals and Sundays; which she punctually executed. She mixed flowers and diamonds in her beautiful hair with admirable art; and often she sighed to have for witnesses of her beauty only her sheep and turkeys, who loved her as much with her horrible donkey skin, whose name was given to her on that farm.

Un jour qu'assise près d'une claire fontaine, où elle déplorait souvent sa triste condition, elle s'avisa de s'y mirer, l'effroyable peau d'âne, qui faisait sa coiffure et son habillement, l'épouvanta. Honteuse de cet ajustement, elle se décrassa le visage et les mains, qui devinrent plus blanches que l'ivoire, et son beau teint reprit sa fraîcheur naturelle. La joie de se trouver si belle lui donna envie de s'y baigner. ce qu'elle exécuta : mais il lui fallut remettre son indigne peau pour retourner à la métairie. Heureusement le lendemain était un jour de fête; ainsi elle eut le loisir de tirer sa cassette, d'arranger sa toilette, de poudrer ses beaux cheveux, et de mettre sa belle robe couleur du temps. Sa chambre était si petite, que la queue de cette belle robe ne pouvait pas s'étendre. La belle princesse se mira et s'admira elle-même avec raison, si bien qu'elle résolut, pour se désennuyer, de mettre tour à tour ses belles robes, les fêtes et les dimanches; ce qu'elle exécuta ponctuellement. Elle mêlait des fleurs et des diamants dans ses beaux cheveux, avec un art admirable; et souvent elle soupirait de n'avoir pour témoins de sa beauté que ses moutons et ses dindons, qui l'aimaient autant avec son horrible peau d'âne, dont on lui avait donné le nom dans cette ferme.

One day of festival, when Peau-d'Ane had put on the dress colour of the sun, the son of the king, to whom this farm belonged, came down there to rest, while returning from the hunt. This prince was young, handsome and beautifully made, the love of his father and the queen his mother, adored by the people. The young prince was offered a country snack, which he accepted: then he set out to explore the farmyards and all their corners. Running from place to place, he came to a dark alley, at the end of which he saw a closed door. Curiosity made him look at the lock; but what became of him, when he saw the princess so beautiful and so richly dressed, that from her noble and modest air, he took her for a divinity! The impetuosity of feeling which he felt at that moment would have led him to break down the door, had it not been for the respect that this ravishing person inspired in him.

Un jour de fête, que Peau-d'Ane avait mis la robe couleur du soleil, le fils du roi, a qui cette ferme appartenait, vint y descendre pour se reposer, en revenant de la chasse. Ce prince était jeune, beau et admirablement bien fait, l'amour de son père et de la reine sa mère, adoré des peuples. On offrit à ce jeune prince une collation champêtre, qu'il accepta : puis il se mit à parcourir les basses-cours et tous leurs recoins. En courant ainsi de lieu en lieu, il entra dans une sombre allée, au bout de laquelle il vit une porte fermée. La curiosité lui fit mettre l'oeil à la serrure; mais que devint-il, en apercevant la princesse si belle et si richement vêtue, qu'à son air noble et modeste il la prit pour une divinité ! L'impétuosité du sentiment qu'il éprouva dans ce moment l'aurait porté à enfoncer la porte, sans le respect que lui inspira cette ravissante personne.

He came out of this dark and obscure alley with difficulty, but it was to inquire who was the person who lived in this little room. He was told that she was a slattern, who was called Donkey-skin, because of the skin she wore; and that she was so dirty and filthy that no one looked at her, nor spoke to her; and that she had been taken only out of pity, to look after the sheep and turkeys.

Il sortit avec peine de cette allée sombre et obscure, mais ce fut pour s'informer qui était la personne qui demeurait dans cette petite chambre. On lui répondit que c'était une souillon, qu'on nommait Peau-d'Ane, à cause de la peau dont elle s'habillait; et qu'elle était si sale et si crasseuse, que personne ne la regardait, ni ne lui parlait; et qu'on ne l'avait prise que par pitié, pour garder les moutons et les dindons.

The prince, not very satisfied with this clarification, saw that these rude people knew no more, and that it was useless to question them. He returned to the palace of the king his father, more in love than can be said, having continually before his eyes the beautiful image of this divinity which he had seen through the keyhole. He repented of not knocking at the door, and promised himself that he would not fail to do so another time. But the agitation of his blood, caused by the ardour of his love, gave him, in the same night, a fever so terrible that he was soon reduced to extremity. The queen his mother, who had only him as a child, despaired that all remedies were useless. She promised in vain the greatest rewards to the doctors; they used all their art, but nothing cured the prince.

Le prince, peu satisfait de cet éclaircissement, vit bien que ces gens grossiers n'en savaient pas davantage, et qu'il était inutile de les questionner. Il revint au palais du roi son père, plus amoureux qu'on ne peut dire, ayant continuellement devant les yeux la belle image de cette divinité qu'il avait vue par le trou de la serrure. Il se repentit de n'avoir pas heurté à la porte, et se promit bien de n'y pas manquer une autre fois. Mais l'agitation de son sang, causée par l'ardeur de son amour, lui donna, dans la même nuit, une fièvre si terrible, que bientôt il fut réduit à l'extrémité. La reine sa mère, qui n'avait que lui d'enfant, se désespérait de ce que tous les remèdes étaient inutiles. Elle promettait en vain les plus grandes récompenses aux médecins; ils y employaient tout leur art, mais rien ne guérissait le prince.

At last, they guessed that a deadly grief was causing all this havoc; they warned the queen, who, full of tenderness for her son, came to beseech him to tell the cause of his affliction; and that, when it came to giving up the crown to him, the king his father would come down from his throne without regret, to bring him up; That if he desired any princess, even if they were at war with the king his father, and had just subjects to complain of, they would sacrifice everything to obtain what he desired; but that she begged him not to let himself die, since their lives depended on his.

Enfin ils devinèrent qu'un mortel chagrin causait tout ce ravage; ils en avertirent la reine, qui, toute pleine de tendresse pour son fils, vint le conjurer de dire la cause de son mal; et que, quand il s'agirait de lui céder la couronne, le roi son père descendrait de son trône sans regret, pour l'y faire monter; que s'il désirait quelque princesse, quand même on serait en guerre avec le roi son père, et qu'on eût de justes sujets pour s'en plaindre, on sacrifierait tout pour obtenir ce qu'il désirait; mais qu'elle le conjurait de ne pas se laisser mourir, puisque de sa vie dépendait la leur.

The queen did not finish this touching speech without wetting the prince's face with a flood of tears. Madam," said the prince at last, in a very weak voice, "I am not so unnatural as to desire my father's crown; may heaven grant that he may live many years, and that he may wish me to be for a long time the most faithful and most respectful of his subjects! As for the princesses you offer me, I have not yet thought of marrying; and you can be sure that, submissive as I am to your wishes, I will always obey you, whatever the cost. - Ah, my son," said the queen, "nothing will cost me to save your life; but, my dear son, save mine and that of the king your father, by declaring to me what you desire, and be assured that it will be granted. Well, madam," he said, "since I must tell you what I think, I will obey you; it would be a crime for me to put in danger two people who are so dear to me. I want Donkey-skin to make me a cake, and as soon as it is made, to bring it to me.