#Alice Te Punga Somerville

Text

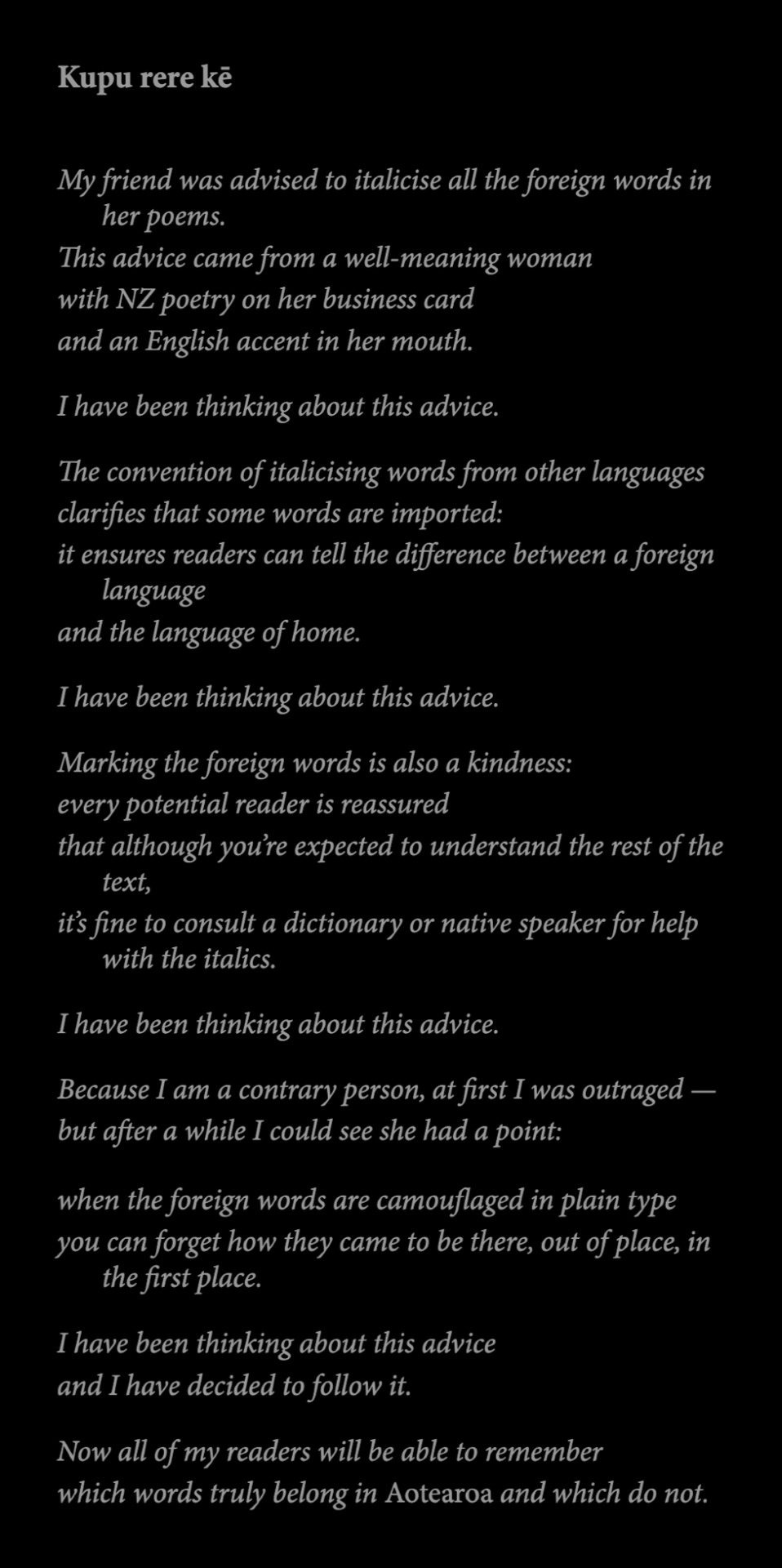

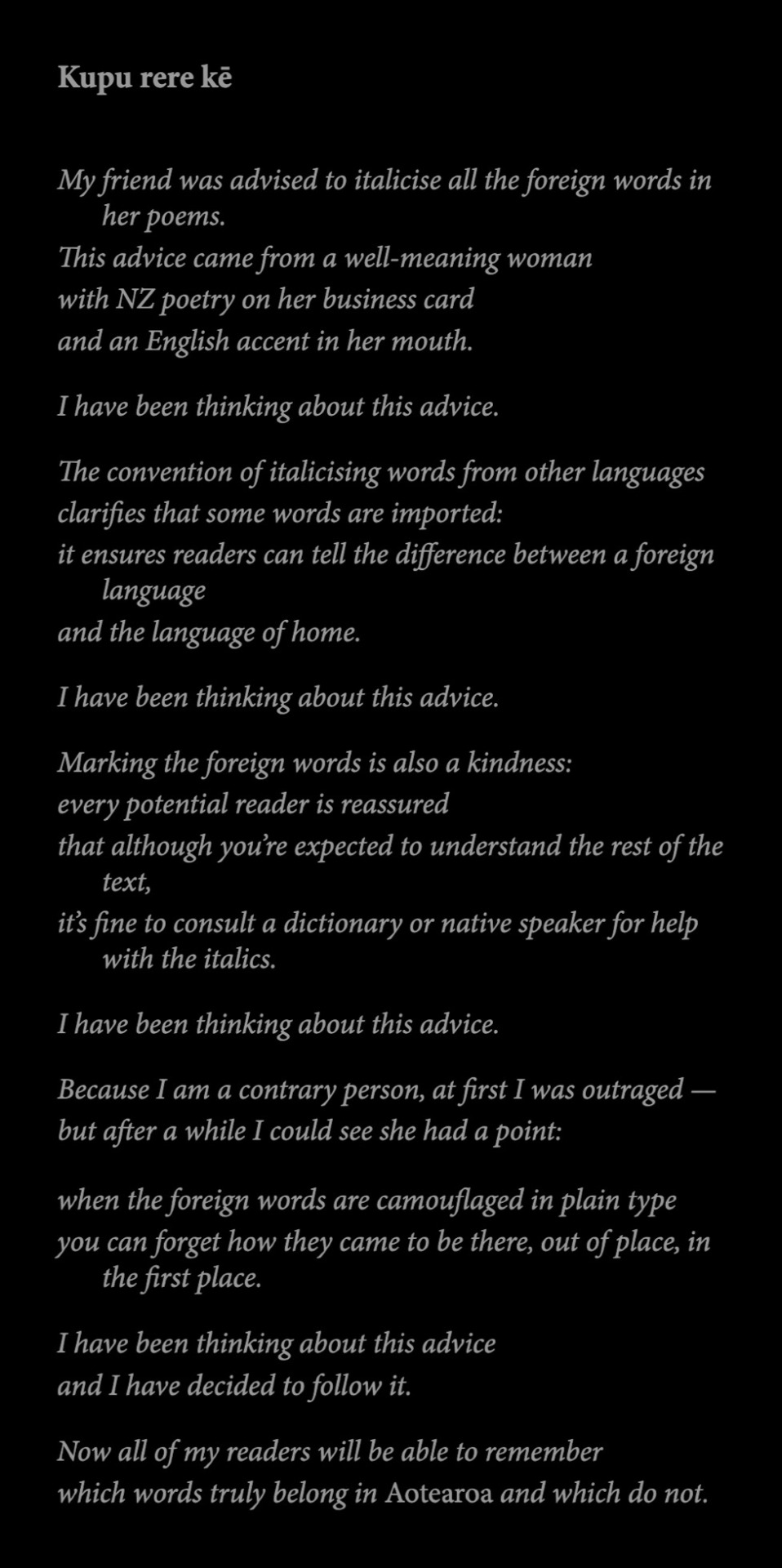

Alice Te Punga Somerville, Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised - Kupu rere kē

[ID: A poem titled: Kupu rere kē. [in italics] My friend was advised to italicise all the foreign words in her poems. This advice came from a well-meaning woman with NZ poetry on her business card and an English accent in her mouth. I have been thinking about this advice. The convention of italicising words from other languages clarifies that some words are imported: it ensures readers can tell the difference between a foreign language and the language of home. I have been thinking about this advice. Marking the foreign words is also a kindness: every potential reader is reassured that although you're expected to understand the rest of the text, it's fine to consult a dictionary or native speaker for help with the italics. I have been thinking about this advice. Because I am a contrary person, at first I was outraged — but after a while I could see she had a point: when the foreign words are camouflaged in plain type you can forget how they came to be there, out of place, in the first place. I have been thinking about this advice and I have decided to follow it. Now all of my readers will be able to remember which words truly belong in -[end italics]- Aotearoa -[italics]- and which do not.

Next image is the futurama meme: to shreds you say...]

(Image ID by @bisexualshakespeare)

#powerful right off the bat#Alice Te Punga Somerville#Always Italicise#Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised#new zealand poem#Always Italicise How to Write While Colonised#Kupu rere kē#aotearoa#quote#quotes#poem#poetry#Māori poetry#Māori#colonization#colonisation#Decolonisation#Te reo māori#Decolonization#new zealand#new zealand poetry

76K notes

·

View notes

Text

"Kupu rere kē" by Alice Te Punga Somerville

from Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised

#poetry#Alice Te Punga Somerville#sorry to repost someone's repost of this but i wanted a version to rb without like. a reaction gif#permanently attached to it

269 notes

·

View notes

Text

"My friend was advised to italicise all the foreign words in her poems."

Read it here | Reblog for a larger sample size!

#closed polls#polls#poetry#poems#poetry polls#poets and writing#tumblr poetry#have you read this#kupu rere kē#alice te punga somerville#māori poetry#te reo māori#admin faves

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

#powerful right off the bat#Alice Te Punga Somerville#Always Italicise#Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised#new zealand poem#Always Italicise How to Write While Colonised#Kupu rere kē#aotearoa#quote#quotes#poem#poetry#Māori poetry#Māori#colonization#colonisation#Decolonisation#Te reo māori#Decolonization#new zealand#new zealand poetry

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kupu here kē

My friend was advised to italicise all the foreign words in her poems.

This advice came from a well-meaning woman

with NZ poetry on her business card

and an English accent in her mouth.

I have been thinking about this advice.

The convention of italicising words from other languages

clarifies that some words are imported:

it ensures readers can tell the difference between a foreign language

and the language of home.

I have been thinking about this advice.

Marking the foreign words is also a kindness:

every potential reader is reassured

that although you're expected to understand the rest of the text,

it's fine to consult a dictionary or native speaker for help with the italics.

I have been thinking about this advice.

Because I am a contrary person, at first I was outraged --

but after a while I could see she had a point:

when the foreign words are camouflagued in plain type

you can forget how they came to be there, out of place, in the first place.

I have been thinking about this advice

and I have decided to follow it.

Now all of my readers will be able to remember

which words truly belong in Aotearoa and which do not.

Alice Te Punga Somerville (Te Āti Awa, Taranaki)

Always Italicise: how to write while colonised

Auckland University Press 2022; purchase link in comments

#poetry#new zealand#aotearoa#alice te punga somerville#māori poetry#linguistics#language#i love this poem#break the lines

1 note

·

View note

Text

#percy jackson#percy jackon and the olympians#bg3#star wars rebels#miraculous ladybug#pokemon#AUSPOL#new zealand#Alice Te Punga Somerville

0 notes

Note

1 4 11?

1. favourite place in your country?

I haven't been to a lot of places in my country. But I love the beaches!!

Paraparaumu and Waikanae are pretty nice, probably because of the beaches. I've got to Paraparaumu beach a few times and a couple of years ago I went to this camp at Waikanae- it happened twice and both times on that camp we took a late night walk down to the beach. Sure, maybe we had to climb over some fences by torchlight but it was fun.

Manakau is nostalgic (not to be confused with Manukau), I used to visit a lot as a kid.

4. favourite dish specific for your country?

I love a good pavlova

11. favourite native writer/poet?

Oh oh oh oh oh I have so many writers and poets I love from Aotearoa I would gladly give recommendations. I've made a post on it before and, understandably, it didn't get any attention. (I'm going to find and reblog it)

I love Chris Tse (current poet laureate, I believe), Tayi Tibble, and essa may ranapiri

I haven't read a lot of fiction by kiwi authors. I. S. Belle is on my radar (Zombabe was I think her first novel? And I recently bought Honeyblood which is sapphic vampires so).

Then there's Thorn Boy/Ship of Horrors/Playful Anarchy/The Cure for Gravity/Scathing/Starborough which are anthologies written by my friends plus Spores is published in Ship of Horrors but that is completely biased for me to say

I'm still going slightly off topic but Out Here: an anthology of Takatāpui and LGBTQIA+ writers from Aotearoa is one of my favourite anthologies, and Overcom/Overcommunicate and Bad Apple are my favourite magazines.

Also, me /j

#lohst.txt#ask tag#theabyssgazesalsointoyou#Maybe I'll just remake my post on Aotearoa writers...#some poetry collections i didnt mention in this post:#hera lindsay bird#meat lovers by rebecca hawkes#biter by claudia jardine#killer rack by sylvan spring#always italicise how to write while colonised by alice te punga somerville#transposium by dani yourukova

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm begging you, please stop italicising te reo Māori words in your fics.

There's a really excellent article by Khairani Barokka on why italicising non-English words in general is not a great idea. (tl;dr: it's very othering)

For te reo there's an additional reason, which is that most of us in Aotearoa stopped italicising te reo decades ago and now when we see it it looks fucking weird. It feels like you're holding the word with tongs; like you're saying "hey I found this weird foreign word and I don't really know what to do with it!"

Which is a pity, because there's some really good fics out there exploring Ed's Māori identity, and the italicising makes them look less good than they are. (I'm planning a specific recs post, but want it to be 100% positive, also there's stuff I haven't read yet.)

I don't want this to be a call out post, because I hate that shit, and I know that everyone's coming from a good place. If you've been italicising te reo words, you're probably doing what you were taught was the right thing, and I genuinely don't want you to feel bad about it. This is just a learning experience; go forth and use italics as they should be used in fan fiction:

"Oh. Oh."

PS I can't write about italicisation and te reo without mentioning the brilliant Alice Te Punga Somerville and the especially her poem Kupu rere kē.

544 notes

·

View notes

Text

kupu rere kē by alice te punga somerville

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

Happy sleepover Friday! 🥳 I guess this falls under advice…what are five books you wish everyone would read?

Oooooooh what a THINKER of a question!

In no particular order, and a very small selection of a much longer list...

Bisexual Men Exist by Vaneet Mehta is an absolutely vital read for everyone, and I do mean everyone.

Queer: A Collection of LGBTQ Writing from Ancient Times to Yesterday edited by Frank Wynne is a stunning collection of queer writing. We're here, we've always been here, and this is such a wonderful collation.

Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised by Alice Te Punga Somerville is hands down my favourite poetry collection; it's incredibly thought-provoking as well as being beautiful writing.

The Pairing by Casey McQuiston -- I was lucky enough to get my hands on an ARC and y'all. Y'ALL. Casey has outdone themself for SURE. Tattoo some of the lines from this book on my heart, honestly.

Sins of the Father: The Long Shadow of a Religious Cult by Fleur Beale. A lot of kiwi have read Fleur Beale's YA novel about a religious cult I Am Not Esther and its sequels (which I also recommend!), but this is a non-fiction account of the children of the leader of Gloriavale here in Aotearoa. It's incredibly eye-opening and I've recommended it to a few people whose position on Gloriavale had previously been 'oh well if that's how they want to live, let them'.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023 poetry rec list

technically a day late but who cares! i don't. it's gonna be a long one this year too despite not having read or written as much poetry as of late; i'm putting my overall fifteen favorite + poetry book recs up here and the rest below a cut to spare your dashboards :)

2022

2021

books:

calling a wolf a wolf (kaveh akbar)

cinema of the present (lisa robertson)

dictee (theresa hak kyung cha)

pilgrim bell (kaveh akbar)

prelude to bruise (saeed jones)

the crown ain't worth much (hanif abdurraqib)

top 15:

abecedarian requiring further examination of anglikan seraphym subjugation of a wild indian reservation (natalie diaz)

about eight minutes of light (robert king)

at luca signorelli's resurrection of the body (jorie graham)

ginen the micronesian kingfisher [i sihek] (craig santos perez)

gods, gods, powers, lord, universe-- (chen chen)

kupu rere kē (alice te punga somerville)

look (solmaz sharif)

ode to the 9,000 year old woman (@/goodbyevitamin)

one art (elizabeth bishop)

petitioning the patron saint of childbirth (danielle boodoo-fortuné)

so mexicans are taking jobs from americans (jimmy santiago baca)

the death loop (jon lovett)

the difficult miracle of black poetry in america: something like a sonnet for phillis wheatley (june jordan)

the madwoman as rasta medusa (shara mccallum)

vocabulary (safia elhillo)

& the gun echoed for centuries; interlude with drug of course; & the light devours us all (yasmin belkhyr)

a brother named gethsemane (natalie diaz)

a map to the next world (joy harjo)

between autumn equinox and winter solstice, today (emily jungmin yoon)

cherish this ecstasy (david james duncan)

coffins (derick thomson)

conflict resolution for holy beings (joy harjo)

failing and flying (jack gilbert)

ginen tidelands [latte stone park] [hagåtña, guåhan] (craig santos perez)

how to be a dog (andrew kane)

i love you to the moon & (chen chen)

i'm sorry birds (@/quezify)

insomnia and the seven steps to grace (joy harjo)

i was sleeping where the black oaks move (louise erdrich)

i watch her eat the apple (natalie diaz)

moth wings and other things (@/grendel-menz)

my father (ollie schminkey)

my soldier, my stranger (scherezade siobhan)

new year's day (joan tierney)

october (louise glück)

praise song for oceania (craig santos perez)

praise the rain (joy harjo)

real estate (richard siken)

sharing a cigarette with joan of arc (dante emile)

song of the anti-sisyphus (chen chen)

table (edip cansever, transl. richard tillinghast)

tear it down (jack gilbert)

temporary job (minnie bruce pratt)

the blue dress (saeed jones)

the lesson of the moth (don marquis)

the universe, as in one last song for the lonely hearts (michelle hulan)

throwing children (ross gay)

untitled (joan tierney)

voices (naomi shihab nye)

when i die i want your hands on my eyes (pablo neruda)

why i am not coming in to work today (jess zimmerman)

wolf moon (nina maclaughlin)

yes, it was the mountain echo (william wordsworth)

#2023#last post of the 2023 tag :)#here's to another year of gay poetry#to be is to be backlit#poems#poetry#croidhe#poetry recs#poetry rec list#writing

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kupu rere kē

My friend was advised to italicise all the foreign words in her poems.

This advice came from a well-meaning woman

with NZ poetry on her business card

and an English accent in her mouth.

I have been thinking about this advice.

The convention of italicising words from other languages

clarifies that some words are imported:

it ensures readers can tell the difference between a foreign language

and the language of home.

I have been thinking about this advice.

Marking the foreign words is also a kindness:

every potential reader is reassured

that although you’re expected to understand the rest of the text,

it’s fine to consult a dictionary or native speaker for help with the italics.

I have been thinking about this advice.

Because I am a contrary person, at first I was outraged —

but after a while I could see she had a point:

when the foreign words are camouflaged in plain type

you can forget how they came to be there, out of place, in the first place.

I have been thinking about this advice

and I have decided to follow it.

Now all of my readers will be able to remember

which words truly belong in Aotearoa and which do not.

Alice Te Punga Somerville, Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised - Kupu rere kē

#Alice Te Punga Somerville#A few people mentioned wanting a text version for accessibility...#powerful right off the bat#Always Italicise#Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised#Always Italicise How to Write While Colonised#Kupu rere kē#aotearoa#colonization#colonisation#Decolonisation#Te reo māori#Decolonization#quote#quotes#poem#poetry#Māori poetry#Māori#new zealand#new zealand poetry#new zealand poem

582 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 in 2024

I meant to do this in January, but life keeps marching on despite my efforts. I stole this from @aliteraryprincess because it just looks fun!! This is 24 books I want to read in 2024 (not including ones I've already read or am currently reading.) These are in no particular order.

Bronze Drum, Phong Nguyen (fiction) (already own, just unread)

Lady Chatterley's Lover, D.H. Lawrence (classic)

Edward IV: A Source Book, Keith Dockray (nonfiction) (already own, just unread)

Lavinia, Ursula K. Le Guin (fiction) (already own, just unread)

Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of Our Nation, Linda Villarosa (nonfiction)

Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives, Michael Strmiska (nonfiction) (already own, just unread)

She Would Be King, Wayétu Moore (fiction) (already own, just unread)

The Peacekeeper, B.L. Blanchard (fiction) (already own, just unread)

Tress of the Emerald Sea, Brandon Sanderson (fiction)

Medieval York, D.M. Palliser (nonfiction)

She Had Some Horses, Joy Harjo (poetry) (already own, just unread)

The Mysteries of Udolpho, Ann Radcliffe (classic) (already own, just unread)

Object Lessons: The Life of the Woman and the Poet in Our Time, Eavan Boland (essays?) (already own, just unread)

Noblewomen, Aristocracy and Power in the Twelfth-Century Anglo-Norman Realm, Susan M. Johns (nonfiction) (already own, just unread)

Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women That a Movement Forgot, Mikki Kendall (nonfiction)

Katherine Parr: Complete Works and Correspondence, Katherine Parr (essays/letters) (already own, just unread)

Daughter of the Moon Goddess, Sue Lynn Tan (fiction) (already own, just unread)

Blood and Roses: One Family's Struggle and Triumph During the Tumultous Wars of the Roses, Helen Castor (nonfiction) (already own, just unread)

If I Were Another: Poems, Mahmoud Darwish (poetry)

Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised, Alice Te Punga Somerville (poetry)

Black Swim, Nicholas Goodly (poetry)

Sight Lines, Arthur Sze (poetry)

Real Queer America: LGBT Stories From Red States, Samantha Allen (nonfiction) (already own, just unread)

Within the Fairy Castle: Colleen Moore's Doll House, Terry Ann R. Neff (idk how to label this, this is my last pick just for fun) (already own, just unread)

If you want to do this, steal it from me and tag me!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kupu rere kē

My friend was advised to italicise all the foreign words in her poems.

This advice came from a well-meaning woman

with NZ poetry on her business card

and an English accent in her mouth.

I have been thinking about this advice.

The publishing convention of italicising words from other languages

clarifies that some words are imported:

it ensures readers can tell the difference between a foreign language

and the language of home.

I have been thinking about this advice.

Marking the foreign words is also a kindness:

Every potential reader is reassured

that although obviously you’re expected to understand the rest of the text,

it’s fine to consult a dictionary or native speaker for help with the italics.

I have been thinking about this advice.

Because I am a contrary person, at first I was outraged –

but after a while I could see she had a point:

When the foreign words are camouflaged in plain type

you can forget how they came to be there, out of place, in the first place.

I have been thinking about this advice and I have decided to follow it.

Now all of my readers will be able to remember which words truly belong in Aotearoa and which do not.

Alice Te Punga Somerville, Always Italicise: how to write while colonised

I saw this posted as an image with a reaction gif. (Credit: @words-and-coffee, without whom I would never have heard of this poem.)

But: it needs to be accessible.

It doesn't need a reaction gif.

It's powerful enough on its own.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

#powerful right off the bat#Alice Te Punga Somerville#Always Italicise#Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised#new zealand poem#Always Italicise How to Write While Colonised#Kupu rere kē#aotearoa#quote#quotes#poem#poetry#Māori poetry#Māori#colonization#colonisation#Decolonisation#Te reo māori#Decolonization#new zealand#new zealand poetry

1 note

·

View note

Text

TBR | January 2024

2024 is here, Happy New Year!

To celebrate, let's set some goals: I want to read 50 books in 2024, and get to at least 60% of my current TBR (this means 43 books). These are both suuuuuuper lowkey goals that I think will be easily accomplishable, but I think it's about time I don't stress myself out with plans. 2024 is shaping up to be a very full year in terms of professional and personal matters, so I want my reading to be relaxing.

However, in the spirit of tackling my TBR, I'm going to try and set a list of books I want to get to this month in the hopes of actually sticking to it...

The Lost Pianos of Siberia - Sophy Roberts

El Zorro: comienza la leyenda - Isabel Allende

Always Italicise: How to Write While Colonised - Alice Te Punga Somerville

Nagori: La nostalgie de la saison qui vient de nous quitter - Ryoko Sekiguchi

Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube: Chasing Fear and Finding Home in the Great White - Blair Braverman

Marx in the Anthropocene - Kōhei Saitō

Poets and Dreamers: Studies and Translations from the Irish - Lady Gregory

I think this is a good mix of non-fiction, fiction, and poetry, with radically different topics, genres, and even languages, so I don't get bored. There's something for every mood and I'm really looking forward to all of them.

What are you reading this year?

7 notes

·

View notes