#Audacity Audio Editor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Workflow for Podcast Audio in Audacity

For some time, I have been using this workflow for processing raw audio into clear, clean, production quality files for ebooks and podcasts.

These steps are for use in Audacity; you can adjust them as necessary for other editors.

Original Recording Quality & Format

First, make sure the original is recorded in as high a quality as possible. Follow the easy to find best practices: quiet location, quality microphone, wind screen and pop filter on the mic, etc.

Make it a high priority to capture the voice (or voices) at a moderate level, but never drive the recorder into clipping. Make sure there is as little hum as possible on the audio. If necessary, use battery power for the mic and recorder. If you have problems with power line hum, see the tutorial for reducing power mains hum in your audio chain

As to format, you cannot go wrong with 24 bit / 96 kHz sampling, if your equipment can do it. Otherwise, use 16 bits if you cannot record at 24 and 48 kHz sampling if you cannot run at 96 kHz.

I know some older, legacy artists may still use CD sampling at 16 bits / 44.1 kHz. Unless you are making CDs, don't bother with that. The future is sampling in multiples of 48 kHz.

1: Sync if Multiple Tracks

When I get the raw recordings, the first thing I do is open a new project in Audacity and - if there are multiple participants - get all of the tracks synced in time. Syncing isn't necessary if everyone's mic is recorded on one multitrack device.

Line up the tracks on some kind of identifiable sound as early as possible. Use a hand clap, count-in, or something you can see on an audio envelope or spectrogram.

If there are multiple recorders in use, you'll notice that the other tracks eventually drift out of sync. Make the best track the "main" or "master" and then stretch or shrink the other tracks to match.

All of the text below refers to one track, but should be done for all tracks it you are working on a podcast with multiple tracks.

Leave a few seconds of dead air / room tone, containing the ambient background sounds, before and after the program.

2: Normalize the Audio

Normalize the sound level of all of tracks to -3 dB relative to full scale (-3 dBFS).

3: Cut Out the Cruft

Cut out sections with extended silences. Make the same cut across all tracks, as it is essential to keep the whole project in sync.

If there are sneezes, coughs, or odd background noises on any track, replace them with silence.

4: Apply Noise Reduction

Apply noise reduction to tracks individually. Audacity is great for identifying and removing rhythmic sounds, such as fans, motors, or anything which whines or buzzes.

To get a profile for the noise, find a few seconds with none of the desired content - some dead air between sentences, for example. Highlight it and run the noise reduction "get profile" function.

After profiling the noise, highlight the whole track and apply noise reduction. Use the maximum number of frequency bands. Don't attack the noise too aggressively, as it makes the recording sound hollow and unnatural. Just apply 6 dB of noise reduction.

If the noise is still there, take a new profile then apply another 6 dB of noise reduction.

5: Re-Normalize the Levels

Normalize the sound level of all of tracks to -3 dB relative to full scale (-3 dBFS).

6: Apply the Noise Gate

The noise gate lowers the background level when there is no strong signal, as between sentences. Work with the settings. I like to set the attenuation to about - 20 dB, with only a few milliseconds (ms) of attack time, about a second (1000 ms) of hold time, and a half second (500 ms) of decay. But work with what you have and go with what sounds best for your situation.

7: Re-Normalize the Levels

Normalize the sound level of all of tracks to -3 dB relative to full scale (-3 dBFS).

8: Apply Amplitude Compression

To bring the peak and average voice levels closer, which is to make the sound more even, use the compressor. Depending on the plugins you have, there may be several choices available. There might be more settings or fewer settings to tweak. In a general sense, these settings work:

Look ahead time: 10 ms

Threshold: -26 dB

Knee: 3 dB

Ratio: between 3:1 and 5:1

Attack: 5 ms

Hang or Hold: 200 ms

Decay: 300 ms

Adjust the threshold, compression ratio, and timings as necessary for best sound of your content.

9: Apply Limiting to Catch the Strongest Peaks

The compressor will let some of the loudest peaks get through, although they will be moderated. Use the limiter to catch those peaks.

Look ahead: 2 ms

Threshold: Set to match level of other peaks.

Release: 30 ms

10: Re-Normalize the Levels

Normalize the sound level of all of tracks to -3 dB relative to full scale (-3 dBFS).

11: Amplify / Attenuate for Platform Compliance

Amplify the whole project + / - a few dB as necessary to meet the requirements of the distribution platform. Whether Spotify, YouTube, SoundCloud, or other platforms, there is some kind of standard for peak and average loudness levels. Also, there is often a requirement that noise be below a certain level.

12: Set the Pre and Post Empty Space

Trim off the dead air before and after the program content. I find that one second of room tone before the start and four seconds after the end is sufficient most of the time.

0 notes

Text

slowly and painfully dying of software

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

guess who figured out how to use the cry editor + audacity... take a listen to shadavise's cry

yeah. this guy

#pokemon#pokemon rse#pkmn#fakemon#pokemon cries#pokemon cry#audio editing#audacity#pokemon cry editor

1 note

·

View note

Note

Beepity boopity :3

#something something “doing this to you” something something#I didn't really have any reason to do this other than figuring out if I could make similar things#It didn't fare well against mp3 compression but it's still receivable. mostly.#I definitely did it differently than prev#I know there are online generators/receivers but I decided it'd be fun to mess around with actual desktop software#so I made this with QSSTV#which sucked because it doesn't have audio file IO#I had to use a pipewire graph editor to manually pipe audio from a media player in#and to save the output file I had to let QSSTV output to the speakers and I had to set ffmpeg to capture the ALSA output monitor#then I just trimmed the audio with audacity and made it an mp3 with ffmpeg#definitely a more roundabout way of doing things#but the most important thing is the friends we made along the way#officially friends with thasune now#sorry thanook. this robot is WAY cooler than you. /j

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Generative AI Policy (February 9, 2024)

As of February 9, 2024, we are updating our Terms of Service to prohibit the following content:

Images created through the use of generative AI programs such as Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, and Dall-E.

This post explains what that means for you. We know it’s impossible to remove all images created by Generative AI on Pillowfort. The goal of this new policy, however, is to send a clear message that we are against the normalization of commercializing and distributing images created by Generative AI. Pillowfort stands in full support of all creatives who make Pillowfort their home. Disclaimer: The following policy was shaped in collaboration with Pillowfort Staff and international university researchers. We are aware that Artificial Intelligence is a rapidly evolving environment. This policy may require revisions in the future to adapt to the changing landscape of Generative AI.

-

Why is Generative AI Banned on Pillowfort?

Our Terms of Service already prohibits copyright violations, which includes reposting other people’s artwork to Pillowfort without the artist’s permission; and because of how Generative AI draws on a database of images and text that were taken without consent from artists or writers, all Generative AI content can be considered in violation of this rule. We also had an overwhelming response from our user base urging us to take action on prohibiting Generative AI on our platform.

-

How does Pillowfort define Generative AI?

As of February 9, 2024 we define Generative AI as online tools for producing material based on large data collection that is often gathered without consent or notification from the original creators.

Generative AI tools do not require skill on behalf of the user and effectively replace them in the creative process (ie - little direction or decision making taken directly from the user). Tools that assist creativity don't replace the user. This means the user can still improve their skills and refine over time.

For example: If you ask a Generative AI tool to add a lighthouse to an image, the image of a lighthouse appears in a completed state. Whereas if you used an assistive drawing tool to add a lighthouse to an image, the user decides the tools used to contribute to the creation process and how to apply them.

Examples of Tools Not Allowed on Pillowfort: Adobe Firefly* Dall-E GPT-4 Jasper Chat Lensa Midjourney Stable Diffusion Synthesia

Example of Tools Still Allowed on Pillowfort:

AI Assistant Tools (ie: Google Translate, Grammarly) VTuber Tools (ie: Live3D, Restream, VRChat) Digital Audio Editors (ie: Audacity, Garage Band) Poser & Reference Tools (ie: Poser, Blender) Graphic & Image Editors (ie: Canva, Adobe Photoshop*, Procreate, Medibang, automatic filters from phone cameras)

*While Adobe software such as Adobe Photoshop is not considered Generative AI, Adobe Firefly is fully integrated in various Adobe software and falls under our definition of Generative AI. The use of Adobe Photoshop is allowed on Pillowfort. The creation of an image in Adobe Photoshop using Adobe Firefly would be prohibited on Pillowfort.

-

Can I use ethical generators?

Due to the evolving nature of Generative AI, ethical generators are not an exception.

-

Can I still talk about AI?

Yes! Posts, Comments, and User Communities discussing AI are still allowed on Pillowfort.

-

Can I link to or embed websites, articles, or social media posts containing Generative AI?

Yes. We do ask that you properly tag your post as “AI” and “Artificial Intelligence.”

-

Can I advertise the sale of digital or virtual goods containing Generative AI?

No. Offsite Advertising of the sale of goods (digital and physical) containing Generative AI on Pillowfort is prohibited.

-

How can I tell if a software I use contains Generative AI?

A general rule of thumb as a first step is you can try testing the software by turning off internet access and seeing if the tool still works. If the software says it needs to be online there’s a chance it’s using Generative AI and needs to be explored further.

You are also always welcome to contact us at [email protected] if you’re still unsure.

-

How will this policy be enforced/detected?

Our Team has decided we are NOT using AI-based automated detection tools due to how often they provide false positives and other issues. We are applying a suite of methods sourced from international universities responding to moderating material potentially sourced from Generative AI instead.

-

How do I report content containing Generative AI Material?

If you are concerned about post(s) featuring Generative AI material, please flag the post for our Site Moderation Team to conduct a thorough investigation. As a reminder, Pillowfort’s existing policy regarding callout posts applies here and harassment / brigading / etc will not be tolerated.

Any questions or clarifications regarding our Generative AI Policy can be sent to [email protected].

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's a list of Free tools and resources for your daily work!🎨

2D

• Libresprite Pixel art + animation • Krita digital painting + animation • Gimp image manipulation + painting • Ibispaint digital painting • MapEditor Level builder (orthogonal, isometric, hexagonal) • Terawell manipulate 3D mannequin as a figure drawing aid (the free version has everything) • Storyboarder Storyboard

3D

• Blender general 3D software (modeling, sculpting, painting, SFX , animation…). • BlockBench low-poly 3D + animation.

Sound Design

• Audacity Audio editor (recording, editing, mixing) • LMMS digital audio workstation (music production, composition, beat-making). • plugins4free audio plugins (work with both audacity and lmms) • Furnace chiptune/8-bit/16-bit music synthesizer

Video

• davinciresolve video editing (the free version has everything) • OBS Studio video recording + live streaming.

2D Animation

• Synfig Vector and puppet animation, frame by frame. Easy. • OpenToon Vector and puppet animation, frame by frame. Hard.

↳ You can import your own drawings.

For learning and inspiration

• models-resource 3D models from retro games (mostly) • spriters-resource 2D sprites (same) • textures-resource 2D textures (same) • TheCoverProject video game covers • Setteidreams archive of animation production materials • Livlily collection of animated lines

740 notes

·

View notes

Text

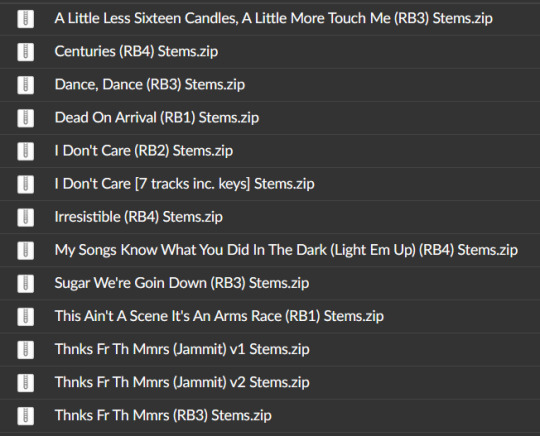

i uploaded the america's suitehearts stems fob released for their remix challenge way back when here!

there are also a few other song stems from the rockband games here - i guess those are compressed/mixed pretty differently and are def not studio stems BUT theyre still amazing for hearing some instrumentals/vocals only !!!!

import the tracks into an audio editor (i used audacity) and have fun!!

#playing the suitehearts tracks as is is fucking insane like no mixing everything at volume 10 so everything is just blasting. BLASTING#patrick's fat vocal stacks.. bassline and guitar parts also sound incredible#i have ZERO knowledge of audio editing so eye will not be doing anything w the stems except muting and unmuting things and going ''WOW'#fall out boy#patrick stump#time capsule#spin for you#asstems#couldnt find a good one for uma thurman and isnt lftos a rockband dlc as well??? hope somebody ... can rip those.... too.... someday..

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

YouTube Downloads through VLC: Step by Step

[EDIT: I've been receiving reports for some time now that this method no longer works. I suspect something about the switch to YouTube Music as a separate app, and/or YouTube's ongoing attempts to force Chrome use, broke the compatibility with the Github version of youtube.luac -- I haven't managed to look into whether there's an updated working version out there yet. Sorry!]

So this guide to easily downloading off YouTube is super helpful, but there's enough important information hidden in the reblogs that (with the permission of OP @queriesntheories ) I'm doing a more step-by-step version.

Please note: these downloads will be in YouTube quality. My test video download is coming through at 360p, even though the video I'm starting from is set to 720p. They're legible, but they won't look great on a TV. For high visual quality, you'll want to seek out other methods.

This guide is written for Windows 10, since that's what I can test on. It's been tested on Firefox, Chrome, and Edge (which is a Chromium browser, so the method should work in other Chromium browsers too). So far, I haven't tracked down a way to use this download method on mobile.

BASIC KNOWLEDGE:

I'll try to make this pretty beginner-friendly, but I am going to assume that you know how to right-click, double-click, navigate right-click menus, click-and-drag, use keyboard shortcuts that are given to you (for example, how to use Ctrl+A), and get the URL for any YouTube video you want to download.

You'll also need to download and install one or more programs off the internet using .exe files, if you don't have these programs already. Please make sure you know how to use your firewall and antivirus to keep your computer safe, and google any names you don't recognize before allowing permission for each file. You can also hover your mouse over each link in this post to make sure it goes where I'm saying it will go.

YOU WILL NEED:

A computer where you have admin permissions. This is usually a computer you own or have the main login on. Sadly, a shared computer like the ones at universities and libraries will not work for this.

Enough space on your computer to install the programs listed below, if you don't have them already, and some space to save your downloaded files to. The files are pretty small because of the low video quality.

A simple text editing program. Notepad is the one that usually comes with Windows. If it lets you change fonts, it's too fancy. A notepad designed specifically to edit program code without messing it up is Notepad++, which you can download here.

A web browser. I use Firefox, which you can get here. Chrome or other Chrome-based browsers should also work. I haven't tested in Safari.

An Internet connection fast enough to load YouTube. A little buffering is fine. The downloads will happen much faster than streaming the entire video, unless your internet is very slow.

VLC Media Player, which you can get here. It's a free player for music and videos, available on Windows, Android, and iOS, and it can play almost any format of video or audio file that exists. We'll be using it for one of the central steps in this process.

If you want just the audio from a YouTube video, you'll need to download the video and then use a different program to copy the audio into its own file. At the end of this post, I'll have instructions for that, using a free sound editor called Audacity.

SETUP TO DOWNLOAD:

The first time you do this, you'll need to set VLC up so it can do what you want. This is where we need Notepad and admin permissions. You shouldn't need to repeat this process unless you're reinstalling VLC.

If VLC is open, close it.

In your computer's file system (File Explorer on Windows), go to C:\Program Files\VideoLAN\VLC\lua\playlist

If you're not familiar with File Explorer, you'll start by clicking where the left side shows (C:). Then in the big main window, you'll double-click each folder that you see in the file path, in order - so in this case, when you're in C: you need to look for Program Files. (There will be two of them. You want the one without the x86 at the end.) Then inside Program Files you're looking for VideoLAN, and so forth through the whole path.

Once you're inside the "playlist" folder, you'll see a lot of files ending in .luac - they're in alphabetical order. The one you want to edit is youtube.luac which is probably at the bottom.

You can't edit youtube.luac while it's in this folder. Click and drag it out of the playlist folder to somewhere else you can find it - your desktop, for instance. Your computer will ask for admin permission to move the file. Click the "Continue" button with the blue and yellow shield.

Now that the file is moved, double-click on it. The Microsoft Store will want you to search for a program to open the .luac file type with. Don't go to the Microsoft Store, just click on the blue "More apps" below that option, and you'll get a list that should include your notepad program. Click on it and click OK.

The file that opens up will be absolutely full of gibberish-looking code. That's fine. Use Ctrl+A to select everything inside the file, then Backspace or Delete to delete it. Don't close the file yet.

In your web browser, go to https://github.com/videolan/vlc/blob/master/share/lua/playlist/youtube.lua

Click in the part of the Github page that has a bunch of mostly blue code in it. Use Ctrl+A to select all of that code, Ctrl+C to copy it, then come back into your empty youtube.luac file and use Ctrl+P to paste the whole chunk of code into the file.

Save the youtube.luac file (Ctrl+S or File > Save in the upper left corner of the notepad program), then close the notepad program.

Drag youtube.luac back into the folder it came from. The computer will ask for admin permission again. Give it permission.

Now you can close Github and Notepad. You're ready to start downloading!

HOW TO DOWNLOAD:

First, get your YouTube link. It should look something like this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=abc123DEF45 If it's longer, you can delete any extra stuff after that first set of letters and numbers, but you don't have to.

Now open VLC. Go to Media > Open Network Stream and paste your YouTube link into the box that comes up. Click Play. Wait until the video starts to play, then you can pause it if you want so it's not distracting you during the next part.

(If nothing happens, you probably forgot to put youtube.luac back. coughs)

In VLC, go to Tools > Codec Information. At the bottom of the pop-up box you'll see a long string of gibberish in a box labeled Location. Click in the Location box. It won't look like it clicked properly, but when you press Ctrl+A, it should select all. Use Ctrl+C to copy it.

In your web browser, paste the entire string of gibberish and hit Enter. Your same YouTube video should come up, but without any of the YouTube interface around it. This is where the video actually lives on YouTube's servers. YouTube really, really doesn't like to show this address to humans, which is why we needed VLC to be like "hi I'm just a little video player" and get it for us.

Because, if you're looking at the place where the video actually lives, you can just right-click-download it, and YouTube can't stop you.

Right-click on your video. Choose "Save Video As". Choose where to save it to - I use my computer's built-in Music or Videos folders.

Give it a name other than "videoplayback" so you can tell it apart from your other downloads.

The "Save As Type" dropdown under the Name field will probably default to MP4. This is a good versatile video format that most video players can read. If you need a different format, you can convert the download later. (That's a whole other post topic.)

Click Save, and your video will start downloading! It may take a few minutes to fully download, depending on your video length and internet speed. Once the download finishes, congratulations! You have successfully downloaded a YouTube video!

If you'd like to convert your video into a (usually smaller) audio file, so you can put it on a music player, it's time to install and set up Audacity.

INSTALLING AUDACITY (first time setup for audio file conversion):

You can get Audacity here. If you're following along on Windows 10, choose the "64-bit installer (recommended)". Run the installer, but don't open Audacity at the end, or if it does open, close it again.

On that same Audacity download page, scroll down past the installers to the "Additional resources". You'll see a box with a "Link to FFmpeg library". This is where you'll get the add-on program that will let Audacity open your downloaded YouTube video, so you can tell it to make an audio-only file. The link will take you to this page on the Audacity support wiki, which will always have the most up-to-date information on how to install the file you need here.

From that wiki page, follow the link to the actual FFmpeg library. If you're not using an adblocker, be careful not to click on any of the ads showing you download buttons. The link you want is bold blue text under "FFmpeg Installer for Audacity 3.2 and later", and looks something like this: "FFmpeg_5.0.0_for_Audacity_on_Windows_x86.exe". Download and install it. Without this, Audacity won't be able to open MP4 files downloaded from YouTube.

CONVERTING TO AUDIO:

Make sure you know where to find your downloaded MP4 video file. This file won't go away when you "convert" it - you'll just be copying the audio into a different file.

Open up Audacity.

Go to File > Open and choose your video file.

You'll get one of those soundwave file displays you see in recording booths and so forth. Audacity is a good solid choice if you want to teach yourself to edit soundwave files, but that's not what we're here for right now.

Go to File > Export Audio. The File Name will populate to match the video's filename, but you can edit it if you want.

Click the Browse button next to the Folder box, and choose where to save your new audio file to. I use my computer's Music folder.

You can click on the Format dropdown and choose an audio file type. If you're not sure which one you want, MP3 is the most common and versatile.

If you'd like your music player to know the artist, album, and so forth for your audio track, you can edit that later in File Manager, or you can put the information in with the Edit Metadata button here. You can leave any of the slots blank, for instance if you don't have a track number because it's a YouTube video.

Once everything is set up, click Export, and your new audio file will be created. Go forth and listen!

#reference#vlc media player#youtube downloader#youtube#uh what other tags should i use idk#how to internet#long post

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

I spent SO long making a badass Caitlyn edit to a song I think she totally embodies, only for tiktok to tell me that I can only post 1 minute of it otherwise they will mute the audio. The audacity!! I could only post the first half of it 😭. And I posted it on my spam account, which is my old Marvel one that I haven’t used in two years LOL. Those followers will be in for a real treat. I can’t let my IRL followers on my main know how much of a nerd I am 🙈. Maybe I’ll post the full vid here. I’m not an editor, but the song was too good to not do something with!

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music Theory Notes (for science bitches) 1: chords & such

This is one of these series where I use my blog as a kind of study blog type thing. If you're knowledgeable about music theory, it will be very basic. But that's kind of the problem, I've really struggled to absorb those basics!

When I was a teenager I learned to play violin and played in orchestras. I could read music, and play decently enough, but I didn't really understand music. I just read what was on the page, and played the scales I had to play for exams.

Lately I've been trying to learn music again. This time my instruments are zhonghu, voice, and DAWs. At some point I might get my violin back too. But really, I'm a total beginner again, and this time I want to do it properly.

For a long time when I tried to learn about music I would get overwhelmed with terminology and jargon and conventions. I might watch videos on composition and they'd be interesting but a lot of it would just fly over my head, I'd just have to nod along because I had no idea what all the different types of chord and such were. I tried to learn from sites like musictheory.net, but I found it hard to figure out the logical structure to fit it all into.

I feel like I'm finally making a bit of headway, so it's time to take some notes. The idea here is not just to answer the what, but also to give some sense of why, a motivation. So in a sense this is a first attempt at writing the introduction to music theory I wish I'd had. This is going to assume you know a little bit about physics, but basically nothing about music.

What is music? From first principles.

This is impossible to answer in full generality, especially since as certain people would be quick to remind me, there's a whole corner of avant-garde composers who will cook up counterexamples to whatever claim you make. So let's narrow our focus: I'm talking about the 'most common' type of music in the society I inhabit, which is called 'tonal music'. (However some observations may be relevant to other types of music such as noise or purely rhythmic music.)

Music is generally an art form involving arranging sound waves in time into patterns (in the sense that illustration is about creating patterns on a 2D surface with light, animation is arranging illustrations in time, etc.).

Physically, sound is a pressure wave propagating through a medium, primarily air. As sound waves propagate, they will reflect off surfaces and go into superposition, and depending on the materials around, certain frequencies might be attenuated or amplified. So the way sound waves propagate in a space is very complicated!

But in general we've found we can pretty decently approximate the experience of listening to something using one or two 'audio tracks', which are played back at just one or two points. So for the sake of making headway, we will make an approximation: rather than worry about the entire sound field, we're going to talk about a one-dimensional function of time, namely the pressure at the idealised audio source. This is what gets displayed inside an audio editor. For example, here's me playing the zhonghu, recorded on a mic, as seen inside Audacity.

A wrinkle that is not relevant for this discussion: The idealised 'pressure wave' is a continuous real function of the reals (time to pressure). By contrast, computer audio is quantised in both the pressure level and time, and this is used to reconstruct a continuous pressure wave by convolution at playback time. (Just like a pixel is not a little square, an audio sample is not a constant pressure!) But I'm going to talk about real numbers until quantisation becomes relevant.

When the human eye receives light, the cone cells in the eye respond to the frequencies of EM radiation, creating just three different neural signals, but with incredibly high sensitivity to direction. By contrast, when the human ear receives sound, it is directed into an organ called the cochlea which is kind of like a cone rolled up into a spiral...

Inside this organ, the sound wave moves around the spiral, which has a fascinatingly complex structure that means different frequencies of wave will excite tiny hairs at different points along the tube. In effect, the cochlea performs a short-time Fourier transform of the incoming sound wave. Information about the direction of the incoming wave is given by the way it reflects off the shape of the ear, the difference between ears, and the movement of our head.

So! In contrast to light, where the brain receives a huge amount of information about directions of incoming light but only limited information of the frequency spectrum, with sound we receive a huge amount of information about the frequency spectrum but only quite limited information about its direction.

Music thus generally involves creating patterns with vibration frequencies in the sound wave. More than this, it's also generally about creating repeating patterns on a longer timescale, which is known as rhythm. This has something to do with the way neurons respond to signals but that's something I'm not well-versed in, and in any case it is heavily culturally mediated.

All right, so, this is the medium we have to play with. When we analyse an audio signal that represents music, we chop it up into small windows, and use a Fourier transform to find out the 'frequencies that are present in the signal'.

Most musical instruments are designed to make sounds that are combinations of certain frequencies at integer ratios. For example here is a plot of the [discrete] Fourier transform of a note played on the zhonghu:

The intensity of the signal is written in decibels, so it's actually a logarithmic scale despite looking linear. The frequency of the wave is written in Hertz, and plotted logarithmically as well. A pure sine wave would look like a thin vertical line; a slightly wider spike means it's a combination of a bunch of sine waves of very close frequencies.

The signal consists of one strong peak at 397Hz and nearby frequencies, and a series of peaks at (roughly) integer multiples of this frequency. In this case the second and third peaks are measured at 786Hz, and 1176Hz. Exact integer ratios would give us 794Hz and 1191Hz, but because the first peak is quite wide we'd expect there to be some error.

Some terminology: The first peak is called the fundamental, and the remaining peaks are known as overtones. The frequency of the fundamental is what defines this signal as a particular musical note, and the intensities of the overtone and widths of the peaks define the quality of the note - the thing that makes a flute and a violin playing the same fundamental frequency sound different when we listen to them. If you played two different notes at the same time, you'd get the spectrums of both notes added together - each note has its own fundamental and overtones.

OK, so far that's just basic audio analysis, nothing is specific to music. To go further we need to start imposing some kind of logical structure on the sound, defining relationships between the different notes.

The twelve-tone music system

There are many ways to do this, but in the West, one specific system has evolved as a kind of 'common language' that the vast majority of music is written in. As a language, it gives names to the notes, and defines a space of emotional connotations. We unconsciously learn this language as we go through the process of socialisation, just as we learn to interpret pictures, watch films, etc.

The system I'm about to outline is known as 12-tone equal temperament or "12TET". It was first cooked up in the 16th century almost simultaneously in China and Europe, but it truly became the standard tuning in the West around the 18th century, distilled from a hodgepodge of musical systems in use previously. In the 20th century, classical composers became rather bored of it and started experimenting with other systems of tonality. Nevertheless, it's the system used for the vast majority of popular music, film and game soundtracks, etc.

Other systems exist, just as complex. Western music tends to create scales of seven notes in an octave, but there are variants that use other amounts, like 6. And for example classical Indian music uses its own variant of a seven-note scale; there are also nuances within Western music such as 'just intonation' which we'll discuss in a bit; really, everything in music is really fucking complicated!

I'll be primarily discussing 12TET because 1. it's hard enough to understand just one system and this one is the most accessible; 2. this has a very nice mathematical structure which tickles my autismbrain. However, along the way we'll visit some variants, such as 'Pythagorean intervals'.

The goal is to try and not just say 'this is what the notation means' but explain why we might construct music this way. Since a lot of musical stuff is kept around for historical reasons, that will require some detours into history.

Octaves

So, what's the big idea here? Well, let's start with the idea of an octave. If you have two notes, let's call then M and N, and the frequency of N is twice the frequency of M... well, to the human ear, they sound very very closely related. In fact N is the first overtone of M - if you play M on almost any instrument, you're also hearing N.

Harmony, which we'll talk about in a minute, is the idea that two notes sound especially pleasant together - but this goes even further. So in many many music systems around the world, these two notes with frequency ratio of 2 are actually identified - they are in some sense 'the same note', and they're given the same name. This also means that further powers of 2, of e.g. 4, 8, 16, and so on, are also 'the same note'. We call the relationship between M and N an octave - we say if two notes are 'an octave apart', one has twice the frequency of the other.

For example, a note whose fundamental frequency is 261.626Hz is known as 'C' in the convention of 'concert pitch'. This implies an infinite series of other Cs, but since the human ear has a limited range of frequencies, in practice you have Cs from 8.176Hz up through 16744.036. These are given a series of numbers by convention, so 261.626Hz is called C4, often 'middle C'. 523.251Hz is C5, 1046.502Hz is C6, and so on. However, a lot of the time it doesn't matter which C you're talking about, so you just say 'C'.

But the identification of "C" with 261.626Hz * 2^N is just a convention (known as 'concert pitch'). Nothing is stopping you tuning to any other frequency: to build up the rest of the structure you just need some note to start with, and the rest unfolds using ratios.

Harmony and intervals

Music is less about individual notes, and more about the relationship between notes - either notes played at the same time, or in succession.

Between any two notes we have something called an interval determined by the ratio of their fundamental frequencies. We've already seen one interval: the octave, which has ratio 2.

The next interval to bring up is the 'fifth'. There are a few different variants of this idea, but generally speaking if two notes have a ratio of 1.5, they sound really really nice together. Why is this called a 'fifth'? Historical reasons, there is no way to shake this terminology, we're stuck with it. Just bear with me here, it will become semi-clear in a minute.

In the same vein, other ratios of small integers tend to sound 'harmonious'. They're satisfying to hear together. Ratios of larger integers, by contrast, feel unsatisfying. But this creates an idea of 'tension' and 'resolution'. If you play two notes together that don't harmonise as nicely, you create a feeling of expectation and tension; when you you play some notes that harmonise really well, that 'resolves' the tension and creates a sense of relief.

Building a scale - just intonation

The exact 3:2 integer ratio used in two tuning systems called 'Pythagorean tuning' and 'just intonation'. Using these kinds of integer ratios, you can unfold out a whole series of other notes, and that's how the Europeans generally did things before 12TET came along. For example, in 'just intonation', you might start with some frequency, and then procede in the ratios 9/8, 5/4, 4/3, 3/2, 5/3, 15/8, and at last 2 (the octave). These would be given a series of letters, creating a 'scale'.

What is a scale? A scale is something like the 'colour palette' for a piece of music. It's a set of notes you use. You might use notes from outside the scale but only very occasionally. Different scales are associated with different feelings - for example, the 'major scale' generally feels happy and triumphant, while a 'minor scale' tends to feel sad and forlorn. We'll talk a lot more about scales soon.

In the European musical tradition, a 'scale' consists of seven notes in each octave, so the notes are named by the first seven notes of the alphabet, i.e. A B C D E F G. A scale has a 'base note', and then you'd unfold the other frequencies using the ratios. An instrument such as a piano would be tuned to play a particular scale. The ratios above are one definition of a 'major scale', and starting with C as the base note, the resulting set of notes is called 'C Major'.

All these nice small-number ratios tend to sound really good together. But it becomes rather tricky if you want to play multiple scales on the same instrument. For example, say your piano is tuned in just intonation to C Major. This means, assuming you have a starting frequency we'll call C, you have the following notes available in a given octave:

C, D=(9/8)C, E=(5/4)C, F=(4/3)C, G=(3/2)C [the fifth!], A=(5/3)C, B=(15/8)C, and 2C [the start of the next octave].

Note: the interval we named the 'fifth' is the fifth note in this scale. It's actually the fifth note in the various minor scales too.

But now suppose you want to play with some different notes - let's say a scale we'll call 'A major', which has the same frequency ratios starting on the note we previously called A. Does our piano have the right keys to play this scale?

Well, the next note up from A would be (9/8)A, which would be (9/8)(5/3)C=(15/8)C - that's our B key, so far so good. Then (5/4)A=(5/4)(5/3)C=(25/12)C and... uh oh! We don't have a (25/12)C key, we have 2C, so if we start at A and go up two keys, we have a note that is slightly lower frequency than the one we're looking for.

What this means is that, depending on your tuning, you could only approximate the pretty integer ratios for any scale besides C major. (25/12) is pretty close to 2, so that might not seem so bad, but sometimes we'd land right in between two notes. We can approximate these notes by adding some more 'in between' piano keys. How should we work out what 'extra' keys to include? Well, there were multiple conventions, but we'll see there is some logic to it...

[You might ask, why are you spending so long on this historical system that is now considered obsolete? Well, intervals and their harmonious qualities are still really important in modern music, and it makes most sense to introduce them with the idea of 'small-integer ratios'.]

The semitone

We've seen if we build the 'major scale' using a bunch of 'nice' ratios, we have trouble playing other scales. The gap above may look rather haphazard and arbitrary, but hold on, we're working in exponential space here - shouldn't we be using a logarithmic scale? If I switch to a logarithmic x-axis, we suddenly get a rather appealing pattern...

All the gaps between successive notes are about the same size, except for the gap between E and F, and B and C, which are about half that size. If you try to work that out exactly, you run into the problems we saw above, where C to D is 9/8 or 1.125, but D to E is 10/9 or 1.11111... Even so, you can imagine how people who were playing around with sounds might notice, damn, these are nice even steps we have here. Though you might also notice places where, in this scheme, it's not completely even - for example G to A (ratio 10/9) is noticeably smaller than A to B (ratio 9/8).

We've obliquely approached the idea of dividing the octave up into 12 steps, where each step is about the size of the gap between E and F or B and C. We call each of these steps a 'semitone'. Two semitones make a 'whole tone'. We might fill in all the missing semitones in our scale here using whole-number ratios, which gives you the black keys on the piano. There are multiple schemes for doing this, and the ratios tend to get a bit uglier. In the system we've outlined so far, a 'semitone' is not a fixed ratio, even though it's always somewhere around 1.06.

The set of 12 semitones is called the 'chromatic scale'. It is something like the 'colour space' for Western music. When you compose a piece, you select some subset of the 12 semitones as your 'palette' - the 'scale of' a piece of music.

But we still have a problem here, which is the unevenness of the gaps we discussed above. This could be considered a feature, not a bug, since each scale would have its own 'character' - it's defined by a slightly different set of ratios. But it does add a lot of complication when moving between scales.

So let's say we take all this irregularity as a bug, and try to fix it. The solution is 'equal temperament', which is the idea that the semitone should always be the exact same ratio, allowing the instrument to play any scale you please without difficulty.

Posed like this, it's easy to work out what that ratio should be: if you want 12 equal steps to be an octave, each step must be the 12th root of 2. Which is an irrational number that is about 1.05946...

At this point you say, wait, Bryn, didn't you just start this all off by saying that the human ear likes to hear nice simple integer ratios of frequencies? And now you're telling me that we should actually use an irrational number, which can't be represented by any integer ratio? What gives? But it turns out the human ear isn't quite that picky. If you have a ratio of 7 semitones, or a ratio of 2^(7/12)=1.4983..., that's close enough to 1.5 to feel almost as good. And this brings a lot of huge advantages: you can easily move ('transpose') between different scales of the same type, and trust that all the relevant ratios will be the same.

Equal temperament was the eventual standard, but there was a gradual process of approaching it called stuff like 'well-tempered' or 'good temperament'. One of the major steps along the way was Bach's collection 'the well-tempered klavier', showing how a keyboard instrument with a suitable tuning could play music in every single established scale. Here's one of those pieces:

youtube

Although we're using these irrational numbers, inside the scale are certain intervals that are considered to have certain meanings - some that are 'consonant' and some that are 'dissonant'. We've already mentioned the 'fifth', which is the 'most consonant' ratio. The fifth consists of 7 semitones and it's roughly a 1.5 ratio in equal temperament. Its close cousin is the 'fourth', which consists of 5 semitones. Because it's so nice, the fifth is kind of 'neutral' - it's just there but it doesn't mean a lot on its own.

For the other important intervals we've got to introduce different types of scale.

The scale zoo

So, up above we introduced the 'major' scale. In semitones, the major scale is intervals of 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 1. This is also called a 'mode', specifically the 'Ionian mode'. There are seven different 'modes', representing different permutations of these intervals, which all have funky Greek names.

The major scale generally connotes "upbeat, happy, triumphant". There are 12 different major scales, taking the 12 different notes of the chromatic scale as the starting point for each one.

Next is the minor scale, which tends to feel more sad or mysterious. Actually there are a few different minor scales. The 'natural minor' goes 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2. You might notice this is a cyclic permutation of the major scale! So in fact a natural minor scale is the same set of notes as a major scale. What makes it different?

Well, remember when we talked about tension and resolution? It's about how the notes are organised. Our starting note is the 'root' note of the scale, usually established early on in the piece of music - quite often the very first note of the piece. The way you move around that root note determines whether the piece 'feels' major or minor. So every major scale has a companion natural minor scale, and vice versa. The set of notes in a piece is enough to narrow it down to one minor and one major, but you have to look closer to figure out which one is most relevant.

The 'harmonic minor' is almost the same, but it raises the second-last note (the 7th) a semitone. So its semitone intervals are 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 3, 1.

The 'melodic minor' raises both the 6th and 7th by one semitone, (edit: but usually only on the way up). So its semitone intervals are 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 1. (edit: When you come back down you tend to use the natural minor.)

If you talk about a 'minor scale' unqualified, you mean the natural minor. It's also the 'Aeolian mode' in that system of funky Greek names I mentioned earlier.

So that leads to a set of 24 scales, a major and minor scale for every semitone. These are the most common scale types that almost all Western tonal music is written in.

But we ain't done. Because remember I said there were all those other "modes"? These are actually just cyclic permutations of the major scale. There's a really nerdy Youtube channel called '8-bit music theory' that has a bunch of videos analysing them in the context of videogame music which I'm going to watch at some point now I finally have enough background to understand wtf he's talking about.

youtube

And of top of that you have all sorts of other variants that come from shifting a note up or down a semitone.

The cast of intervals

OK, so we've established the idea of scales. Now let's talk intervals. As you might guess from the 'fifth', the intervals are named after their position in the scale.

Let me repeat the two most common scale modes, in terms of number of semitones relative to the root note:

position: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 major: 0, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12 minor: 0, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12

So you can see the fourth and fifth are the same in both. But there's a difference in three places: the third, the sixth, and the seventh. In each case, the minor is down a semitone from the major.

The interval names are... not quite as simple as 'place in the scale', but that's mostly how it works. e.g. the 'major third' is four semitones and the 'minor third' is three.

The fourth and fifth, which are dual to each other (meaning going up a fifth takes you to the same note as going down a fourth, and vice versa) are called 'perfect'. The note right in between them, an interval of 6 semitones, is called the 'tritone'.

(You can also refer to these intervals as 'augmented' or 'diminished' versions of adjacent intervals. Just in case there wasn't enough terminology in the air. See the table for the names of every interval.)

So, with these names, what's the significance of each one? The thirds, sixths and sevenths are important, because they tell us whether we're in minor or major land when we're building chords. (More on that soon.)

The fifth and the octave are super consonant, as we've said. But the notes that are close to them, like the seventh, the second and even more so the tritone, are quite dissonant - they're near to a nice thing and ironically that leads to awkward ratios which feel uncomfy to our ears. So generally speaking, you use them to build tension and anticipation and set up for a resolution later. (Or don't, and deliberately leave them hanging.)

Of course all of these positions in the scale also have funky Latin names that describe their function.

There's a lot more complicated nuances that make the meaning of a particular interval very contextual, and I certainly couldn't claim to really understand in much depth, but that's basically what I understand about intervals so far.

Our goofy-ass musical notation system

So if semitones are the building block of everything, naturally the musical notation system we use in the modern 12TET era spaces everything out neatly in terms of semitones, right?

Right...?

Lmao no. Actually sheet music is written so that each row of the stave (or staff, the five lines you write notes on) represents a note of the C major scale. All the notes that aren't on the C major scale are represented with special symbols, namely ♯ (read 'sharp') which means 'go up a semitone', and ♭ (read 'flat') which means 'go down a semitone'. That means the same note can be notated in two different ways: A♯ and B♭ are the same note.

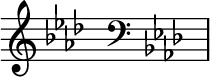

The above image shows the chromatic scale, notated in two different ways. Every step is exactly one semitone.

Since a given scale might end up using one of these 'in between' notes that has to be marked sharp or flat, and you don't want to do that for every single time that note appears. Luckily, it turns out that each major/minor scale pair ends up defining a unique set of notes to be adjusted up or down a semitone, called the 'key signature'. So you can write the key signature at the beginning of the piece, and it lasts until you change key signature. For example, the key of 'A♭ major' ends up having four sharps:

There is a formula you can use to work out the set of sharps or flats to write for a given key. (That's about the point I checked out on musictheory.net.)

There is some advantage to this system, which is that it very clearly tells you when the composer intends to shift into a different scale, and it saves space since with the usual scales there are no wasted lines. But it's also annoyingly arbitrary. You just have to remember that B to C is only a semitone, and the same for E to F.

What are those weird squiggly symbols? Those are 'clefs'. Each one assigns notes to specific lines. The first one 𝄞 is the 'treble clef', the second one 𝄢 is the 'bass clef'. Well, actually these are the 'G-clef' and the 'F-clef', and where they go on the stave determines note assignment, but thankfully this has been standardised and you will only ever see them in one place. The treble clef declares the lines to be E G B D F and the bass clef G B D F A.

There is also a rarer 'C-clef' which looks like 𝄡. This is usually used as the 'Alto clef' which means F A C E G.

This notation system seems needlessly convoluted, but we're rather stuck with it, because most of the music has been written in it already. It's not uncommon for people to come up with alternative notations, though, such as 'tabs' for a stringed instrument which indicate which position should be played on each string. Nowadays on computers, a lot of DAWs will instead use a 'piano roll' presentation which is organised by semitone.

And then there's chords.

Chords! And arpeggios!

A chord is when you play 3 or more notes at the same time.

Simple enough right? But if you wanna talk about it, you gotta have a way to give them names. And that's where things get fucking nuts.

But the basic chord type is a 'triad', consisting of three notes, separated by certain intervals. There are two standard types, which you basically assemble by taking every other note of a scale. In terms of semitones, these are:

Major triad: 0 - 4 - 7 Minor triad: 0 - 3 - 7

Then there's a bunch of variations, for example:

Augmented: 0 - 4 - 8 Diminished: 0 - 3 - 6 Suspended: 0 - 2 - 7 (sus2) or 0 - 5 - 7 (sus4) Dominant seventh: 0 - 4 - 7 - 10 Power: 0 - 7

There is a notation scheme for chords in pop, jazz, rock, etc., which starts with a root note and then adds a bunch of superscripts to tell you about any special features of a chord. So 'C' means the C Major triad (namely C,E,G) and 'Cm' or 'c' means the C Minor triad (namely C,E♭,G).

In musical composition, you usually tend to surround the melody (single voice) with a 'chord progression' that both harmonises and creates a sense of 'movement' from one chord to another. Some instruments like guitar and piano are really good at playing chords. On instruments that can't play chords, they can still play 'arpeggios', which is what happens if you take a chord and unroll it into a sequence of notes. Or you play in an ensemble and harmonise with the other players to create a chord together. Awww.

Given a scale, you can construct a series of seven triad chords, starting from each note of the scale. These are generally given scale-specific Roman numerals corresponding to the position in the scale, and they're used to analyse the progression of chords in a song. I pretty much learned about this today while writing this post, so I can't tell you much more than that.

Right now, that's about as far as I've gotten with chords. On a violin, you can play just two strings at the same time after all - I never had much need to learn about them so it remains a huge hole in my understanding of music. I can't recognise chords by ear at all. So I gotta learn more about them.

As much as I wrote this for my own benefit... if you found this post interesting, let me know. I might write more if people find this style of presentation appealing. ^^'

285 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phares' Lost Lines!

Long story short, after much much much toil of trying to surf through computer- and audio-nerds' jargon and decidedly untrustworthy-named websites, I was finally able to crack the .acb and .awb audio files that people were able to preserve of the Dragalia voice cast! (If you've never heard of those audio files, well then, now you know where I was starting at, too... Let's just put it this way - it's an audio file that even audio players/editors like Audacity aren't equip to handle, at least ordinarily.)

And as you might suspect from the title, Phares had three voice lines that go unaccounted for in his actual unit anywhere in the game. Strangely, all three I'm guessing seem to hail from The Blood That Binds event, which makes it doubly strange since, well, we didn't get voiced events here.

Transcripts in order (and hopefully the actual voicelines, if you want to take a listen!):

"We have our belief in possibility to thank for our retaking the Halidom."

"It's been so long since we were all together, and yet fate prevents us from enjoying it."

"A summons from Leonidas? I have a bad feeling about this..."

Also not sure this one is truly lost per se but it's certainly a line not recorded in the wiki despite being 'accessible' (for however a very short window in-game) in the form of his summon quote, which is: "Let us begin our inquiry into truth!"

Hm, actually, before I post, I think I might take a guess that these are instead lines for him on the homescreen while the event was active, which might make them not 'unknown' per se but certainly inaccessible now, since I highly doubt anyone caught ordinary gameplay of all of them occurring.

Still, they're pretty darn niche and hard to get to in the game, even on the servers, so maybe someone finds it interesting regardless!

#dragalia lost#dragalia#dragalia lore#lost audio#Hopefully someone enjoys!#The big reason that I went to all this trouble was trying to see if they were able to get the voice recording of Leo saying Euden's name#But so far it appears the answer to that question is 'no' alas. Sigh. I know I'm not dreaming!!!!!#I still might do some sifting to see if there are more lost lines I can find...#Also random but Xenos is pronounced “Zen - ohs” not “Zee - nohs”. The more you know!

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, hope you are doing well. I've always wondered, for those fanvids that overlap music with dialogue (and just in general) how do you remove the show's original soundtrack or music?

Hi there, this is a great question! I’m not that familiar with removing background audio so I went to the vidding discord to ask for help. Here are the recommendations I’ve found for you.

Audio Editing Tips and Resources

@bingeling used Adobe Premiere’s built-in audio filters and found decent success with the majority of the clips where they needed to edit audio. @eruthros pointed out that if the original video file is in 5.1 surround sound you can actually just mute the individual tracks in your video editor. Audacity has a lot of audio editing features and they’ve also introduced some AI tools to isolate and separate vocals. Audacity has long been a go-to for fanvidders for audio editing and something I used early on in my viddding experience, too. (edited to add: thank you to searchingweasel for this suggestion too!) Spleeter has been recommended by @sandalwoodbox and @Januarium. Lalal.ai is recommended by @Januarium, they used it in their fanvids and thought it worked well. Adobe Enhance comes recommended by by @vielmouse. If you have questions about any of these tools or other questions about fanvidding, gathering source, music resources, exporting help, you’re welcome to join the vidding discord. There’s also channels for sharing wips, recs and lots more. Hope this helps! Thank you for the ask! And thank you to the vidding discord for sharing your knowledge with us!

#viddingdora#vidding#the vidding process#answerdora#askdora#textpost#vidding resource#fandom resource#cool resource#fan edit

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whiny bitching

I have absolutely no fucking clue why this keeps happening, but the youtube playlists I've made for magical girl stories keeps fucking reordering itself. None of the other channels I've worked on have ever done this. It's never been a damn issue before.

Like what the fuck. I check once every few days and sure enough several of these stupid playlists needs to be reorganized. It pisses me off so much.

The good news is that once episode is fully recorded, I delete the playlist + old videos and upload a full version so this problem will sort itself out in time.

But man, maintaining an archive this time around isn't very fun. Between this and recording two versions of each video and then feeling like a pest when I badger other kind fans for help (AND NOT BEING ABLE TO RECORD ALL THE STUPID VIDEOS ON MY OWN WHAT THE FUCK THIS IS THE DUMBEST METHOD FOR STORY TELLING I HATE IT)-- all of that makes this a real pain in the ass and I kind of want to quit lmao.

And like-- as long as I'm bitching about shit that doesn't matter. It feels bad to work on crappy youtube videos that don't have full audio and make you wonder "will anyone actually watch this shitty version" but also the google drive is like "will anyone actually watch the stuff on the google drive"? I have no idea if people actually use the drive or not. So I gotta be real, I've put the bare minimum into recording + editing the last couple of weeks. Well, that and real life stuff.

I still haven't finished recording the magia record main story for the youtube channel or even the madoka magica main story for the drive...

No this isn't me begging for comfort/appreciation, I'm just raging like a little baby right now. I admit it.

Anyways, if you've wondered why the progress on the archive is so slow, it's because it's demotivating as hell.

I really regret linking the muffin exedra account to my main account because I'm not sure if I'd be able to share it/give it away to someone else if it came to that. I was just full of audacity and thought this would be like how it was before...

ALSO WHILE I'M AT IT

I FUCKING HATE HOW THIS STUPID ASS GAME DOES THE STORY ARCHIVE SHIT

Go to your archive and play a story. Every single one, except for Name, will play this stupidly loud shiney sound and background music INTO the fucking story. I am not an editor, I only just realized how to edit it out (poorly) and it pisses me off.

"oh but muffin just leave it in it's fine" NO IT'S NOT IT'S SO FUCKING LOUD AND SCREETCHY AND IT SOUNDS TERRIBLE AND I HATE IT

AUGH

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I have seen three pictures of the man".

Picture_01

The boy stood still, staring at the camera, his gaze fixed, unyielding. A absent smirk, just the stark, unadorned plane of his face. It was a face that already knew the weight of scrutiny, the silent judgment that settled like dust. No empathy, but a rigid mask, the skin stretched taut over the bones, revealing nothing.

"What a dreadful child!", a silent testament to the cruelty of first impressions. "What a hideous little boy! A monkey! That's why he looks so miserable and nobody wishes to play with him.". Parents would quietly whisper to each other upon seeing him arriving at the playground, shamelessly blessing God for having not so ugly sons.

Even in childhood, the contours of our features are being etched into a narrative not of our making. A single, unyielding look, and the world begins to define us: dreadful, wizened, hideous. Labels whispered and solidified, a prison built of glances. How swiftly the gaze of society could strip innocence, how easily a child could become a stigma, a grotesque caricature, simply for the way he appears, and becomes no longer human.

#GlitchArt + #AIportrait + Text inspired by a paragraph from No Longer Human by #OsamuDazai.

Childhood and Body Shaming.

Society's judgmental and pitiful gaze.

Physical appearance and discrimination.

Art inspiration and creative process.

Experimental Art and New Media.

Body Horror and Body Positivity.

How was the video made?

Initial AI Image Generation and Glitching:

Eight AI-generated portraits were compiled into a PDF (JPG compression).

The PDF's raw data was manipulated using a text editor (Notepad++) by replacing hexadecimal characters, creating initial glitches.

The glitched PDF was viewed in SumatraPDF.

Each glitched image was copied and pasted into a single Photoshop file as separate layers (PSD).

The PSD file's raw data was again manipulated in Notepad++, further glitching the image layers.

The glitched layers were then adjusted in Photoshop using Hue and Saturation adjustments.

All layers were blended into a final PNG image.

Image Sorting and Animation:

The PNG image was processed using the "UltimateSort" script by GenerateMe, creating a series of sorted frames.

A selection of these frames was exported.

The frames were compiled into an animated GIF.

The GIF was encoded into an MP4 video.

The GIF's raw data was databended in Note++

The glitched GIF was played in IrfanView and screen recorded via ShareX.

The two MP4 video files that were made from the GIF were edited together in Adobe Premiere.

Video Glitching and Audio Integration:

The edited video track was exported as an MP4.

The MP4 was converted to an AVI file using the ASV1 codec.

The AVI video's raw data was imported into Audacity as a RAW file, glitched, and saved.

The glitched AVI was converted back into an MP4 video using FFmpeg.

The glitched video was imported into Adobe Premiere.

Audio was added: a Mubert-generated musical track and a voiceover.

The voiceover was created using TTSMaker, based on text generated by Gemini 2.0, which drew inspiration from a paragraph in No Longer Human.

#digital art#new media art#artificial intelligence#glitch art#glitch#art#artists on tumblr#databending#dark art#macabre#dark aesthetic#dark artwork#glitchart#glitch aesthetic#glitchartistscollective#glitch artists collective

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Since you don't see many edits here, and i am a dumbass in editing, could you make a tutorial on it? Like: what apps should we use, what should or shouldn't do, devices, etc. Since i personally worship your editing prowess, i couldn't help myself but ask for your guidance sensei. 🙇♀️

I don't use a "special device" to make my edits, just a computer which can run a videoediting software and Wallpaper Engine correctly (in my case it's an Apple Mac Pro 4,1 from 2009 with upgraded RAM and GPU, and also with Windows 10 installed on it, but that's not important). My server pc build out of my spare parts, and it's serves as a network bridge, and a file storge (like a NAS, or something) to store my personal files, like the assets for the edits on HPP. The way I make my edits, is a different story. I like to put the charaters in different scenarios to make the edit more enjoyable. I usually chose one image from my pre-granarated ones, or I use (if i see a, as i call an edit "suspicious" image here on Tumblr or X) an image from my "Likes", or if I can't find any which is good for the scanario in my head I generate one using PixAI's Ebora Pony XL AI model. Than if I have an image, I put together a static version of the edit in Paint.NET (PaintdotNET). Here I cut down the unnecessary and the broken (weirdly generated hands, .etc) parts of the image, and I remove the background if I'd like to use a different one. Than I chose a stethoscope png what are suitable for the edit, but I recently using the hand with stethoscope one which you can see in my recent edits. I also make some barely visble changes to the main image and the stething image. If it's done, and looks good I save them (the base image, the background, and the steting png separately) in a folder. After that it's time to "animate" the edit, which is just using the Wallpaper Engine's built in Shake effect, if that part is done, I record the animated soundless edit using OBS, which is usually a 5-6 minutes raw mp4 file. Than I put the raw recording into the video editor which is my case is the Wondershare Filmora X. I chose one of the heartbeat and bearthing audios from my server (if it's needed I modify it a bit in Audacity), and speed them up to mach with the animation. I make the breathing way quieter to have the heartbeat in focus, also i duplicate the hb sound to make a stereo effect, which means the I make the left side a bit louder and add more bass to it than the right side, which make a really good heart pulse effect (ROLL CREDITS). Also in here I add some video effects, cut down the unnecessary parts, I cut down the video to 2 minutes to become uploadable for X, than it's time to export it. After I exported the final edit, i check it for mistakes and I fix them if i find any, and the fixed version gonna be uploaded to Tumblr and X. This whole process is 2+ hours usually, but it's could be more for longer and more complex edits. But you doesn't need to follow my way to make edits, if you ever used a photo editor and a video editor before, and you know how put a transparent png on an image, and a greenscreen video on another one, you good to go. There is a lot of ways you can make an edit, so you can chose one which are suitable for you. If you still need help, you can join the Cardio Editor's Hub, there are lot of other people who gladly gives you some tips and tricks. Good luck, have fun! :D

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

how are you getting the vocals by themselves if you don’t mind me asking? :]

-@circles-n-spirals-alike

you need the flac files for both the normal version of the song you want the vocals of and it's instrumental, which you can get via Chonny's bandcamp

then you just input them into your audio editor of choice (I use Audacity because it's free and easy to use) (make sure to get it from here)

I set it up like this. then all you need to do is select only the instrumental track at the bottom, and go to effect > invert

this inverts the instrumental, which in turn sort of 'cancels out' the instrumental playing from the normal track. if you play both at the same time, you'll only hear the vocals

now you can select both tracks and go to tracks > mix > mix and render. this will mix both tracks into one only-vocals track (or you can just export as an mp3 or any other file. it'll essentially do the same thing)

now you too can listen to Soul's gay little laugh in TSE! (it's at minute 2:00)

two things that I think are really important to mention:

I'm not entirely sure how okay Chonny is with anyone doing this at all, and/or redistributing these vocals-only files without his permission, hence why I'm refraining to do so. I'm personally only using these to analyze little nuances in the vocal performances that are otherwise lost to the instrumental, and I'm limiting myself to sharing only little sections that I think are amusing and/or funny. like Soul's laugh in TSE or Heart's beatboxing in The Bidding. I haven't seen anything about Chonny being *not* okay with it, but it's best to tread carefully here. if I find out he's in fact not okay with anyone doing this, I'll take both posts (along with this one) down.

2. this is in no way a replacement for actual acapella files given by Chonny himself - the tracks are semi-clean at the most, and a lot of the times you'll still hear little bits of the instrumental here and there, especially when the vocals have any sort of distortion or echo effect on them. I've also noticed you'll hear more of the instrumental on older songs of CCCC (the difference becomes really clear when you listen to Spring and a Storm & Storm and a Spring together. in SaaS you'll still hear some of the instrumental in the background, while StaaS is a lot 'cleaner' in comparison.) my guess is this is because of a difference in mixing, but I don't know enough about music engineering to have a better guess than that :P

I hope this helps!

#answers#also I lied I don't use Audacity I use DarkAudacity but it's literally the exact same thing but dark mode so it doesn't matter

24 notes

·

View notes