#Devonshire witchcraft

Text

This is my version of the three bees in a bag charm housed in the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic; Hung in the best room of the house, they will bring good fortune, happiness, health and sweet luck. This version includes a hag stone and allspice, and are held in a black bag for protective qualities. 🐝

#my post#folk magick#devonshire witchery#cornish witchcraft#charms#three bees in a bag charm#traditional witchcraft#paganism#bucca#the great god pan#bucca gwidder#bucca dhu#cecil williamson#museum of witchcraft and magic#boscastle

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

RESTOCKS!

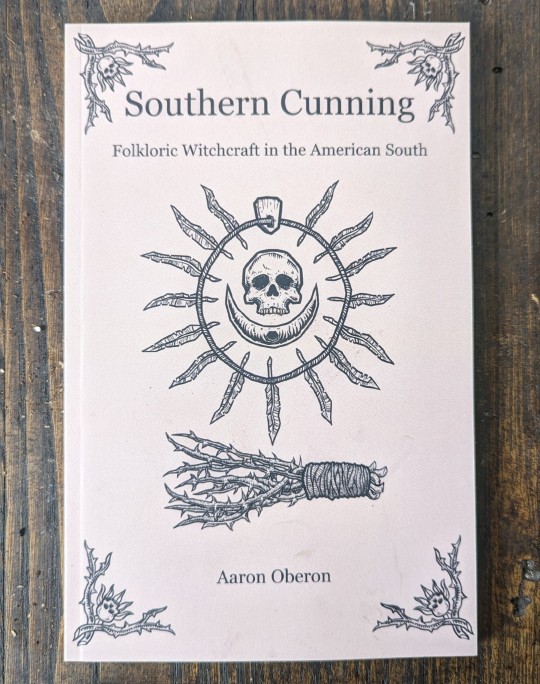

Southern Cunning: Folkloric Witchcraft in the American South by Aaron Oberon

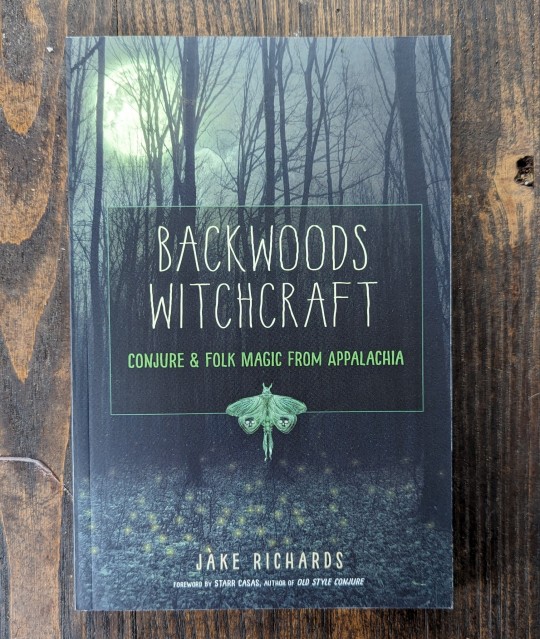

Backwoods Witchcraft: Conjure & Folklore from Appalachia by Jake Richards

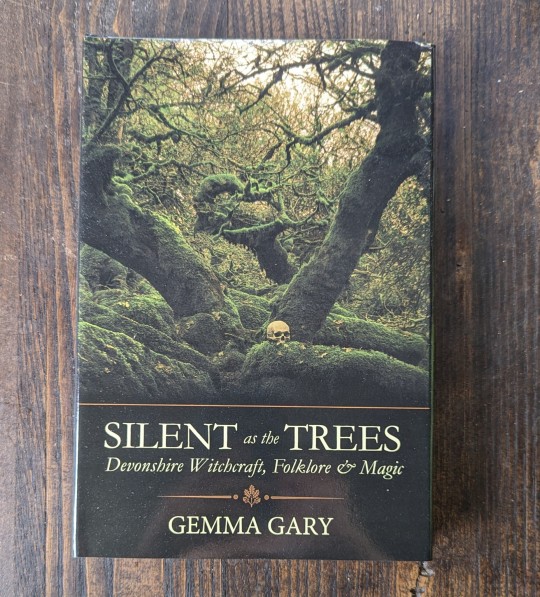

Silent as the Trees: Devonshire Witchcraft, Folklore & Magic by Gemma Gary

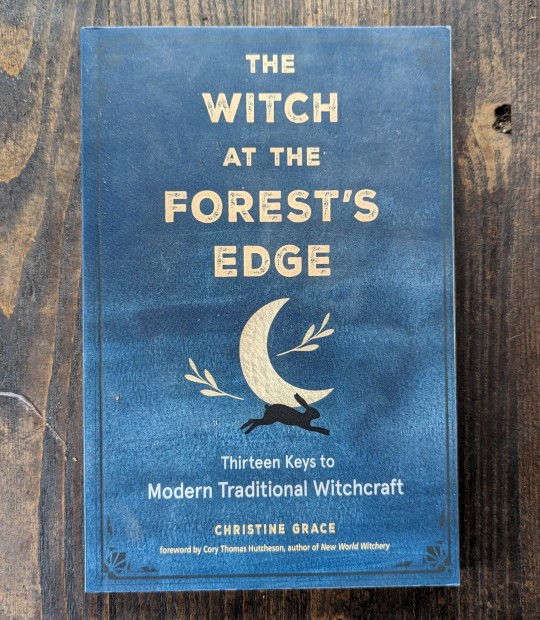

The Witch at the Forest's Edge: Thirteen Keys to Modern Traditional Witchcraft by Christine Grace

#traditional witchcraft#modern traditional witchcraft#folkloric witchcraft#folk magic#folk witchcraft#witchblr#southern cunning#cunningfolk#silent as the trees#backwoods witchcraft#witch community#witchcraft#witchcraft books#pagan books#genna gary#jake richardson#aaron oberon

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

pj masks au

Greg Hathaway, Conner Mohan, Amaya Hawkins,and Luna Devonshire are four abused children, Greg and Conner suffer at the hands of their parents and get abused by a babysitter their parents knowingly leave them with and pay here good money, Conners a cat whisperer even though his parents hate them, and Greg loves reptiles and doesn't care if his stupid parents think they're icky

Amaya has a bratty little sister named Brittany that's Mommy and Daddy's little princess who can do no wrong. Meanwhile Amaya gets zero affection and can only do wrong. But Amaya has a way with birds

Luna's a rich girl with awful parents, they also get bullied at school by the ninja squad,wolfys,and the skull crushers. Luna does witchcraft when her parents have more important stuff to do than take care of their daughter, with moths as her familiars

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

1) Which religion/spiritual path do you identify with?

Thank you for sending me a question!!

Currently? I'm pagan and........ spiritual? I mean, i have three Deities I work with routinely and a spirit i work closely with...... and I also honor the energy of all things, and feel especially called by natural energies...... so possibly under the animist label as well?

XD

As a teen I did ID with Wicca... tho i know has too many rules and aspects i don't agree with or find in conflict with my own instincts and personal knowledge. It just happened to be the flavor of spirituality closest to what i felt that actually had books written on it that i could access!

Now i have a few more books and resources, some across the spectrum and some focusing on witchcraft from areas of England a large chunk of my ancestry is from. (Multiple lines of my family tree dead end in Devonshire, England according to the family tree my sis spent time building, even more lines of my family than those that lead to Poland.... which means mum accidentally lied to me and my sis about our dominant ancestry but oh well XD). I enjoy finding inspiration in my family history but i dont' feel beholden to it.

Sooooooooo........ to answer the question..... uhhhhhhhh....... I'm a witch..... and a magic worker...... and an energy worker..... i'm a bit of a spiritual witch as well? When i actually work magic it tends to be very representational and bringing the small action on the representation to the large or a charm with every piece chosen for correspondence of my own making...... SO... witch for sure, spiritual, pagan as fuck and maybe some other labels XD

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

—

Silent as the Trees:

Devonshire Witchcraft, Folklore & Magic

by Gemma Gary

#silent as the trees#Gemma Gary#traditional withcraft#witchcraft#magic#grimoire#devonshire magic#Devonshire witchcraft#Devonshire folklore

87 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yes! Yes! Yes!

New reading material that arrived in the post today 🖤💫🖤

#witchcraft#traditional witchcraft#gemma gary#silent as the trees#devon witchcraft#devonshire witchcraft#Folk Witchcraft

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

scent of the day: georgiana, duchess of devonshire (possets)

"starring the incomparable possets' lavender. this time it is paired with a fabulous sandalwood which would make a pasha swoon.”

i have... complicated feelings about this one. it smells like varnished woods, intensely so, with an acerbic yet fragrant character that is almost lemon-like. not much lavender is detectable at first, until i realised it’s present in a subtle way, like a transparent wash infused with a dry-herbal quality that makes me think of herbariums and tea cabinets carved in dark exotic wood and unsweetened lavender-lindenflower drinks.

georgiana smells like ‘very old, very expensive furniture you’re not really allowed to touch’ meets ‘high-end, impossibly elegant metaphysical shop’; an interesting and classy ambient smell, yet quite unusual for a perfume worn on skin. i think i’ll let this age a couple of months and i’ll come back to it with some further thoughts. for now, colour me intrigued.

#possets#scent of the day#scents#perfume oil#indie perfume#witchblr#witchcraft#perfume magic#perfume witchcraft#beauty magic#beauty witchcraft#scent magic#scent witchcraft#ką sako lapė#possets: georgiana duchess of devonshire

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silent as the Trees

"Silent as the Trees"

Gemma Gary

The West Country of the UK, an area that stretches across the historic counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Wiltshire and Gloucestershire is a magical region filled with localized customs, dialects and folk beliefs.

For centuries the tales of its local people have filtered out into the world in verse and song. The black dog, the fisherman's wife, tales of haunted coves and wood, Gabriel's Hounds barking the Wild Hunt in hot pursuit through Wistman's Wood. The mists of the moors like a shroud separating the worlds.

From the late 18th century onward the particulars of Devonshire and Cornish folklore have been a popular subject of antiquary and folklorist, consumed by the general public in quantity. Throughout the 19th century the number of volumes, covering much of the same material, published as collections of folklore, superstition and custom runs into the thousands of titles.Yet these folk traditions are living traditions even today. They have continued down the centuries to be practiced, seasonally, both privately and publicly.

Gemma Gary is an author, witch, and folklorist whose practice as a Cornish traditional witch is outlined in her previous works; "The Black Toad", "The Charmer’s Psalter", "Wisht Waters", and "The Devil’s Dozen". Her recent collection of Devonshire folklore and witchcraft "Silent as the Trees: Devonshire Witchcraft, Folklore & Magic" is a welcome addition to the literature of Devonshire folk practices.

"Silent as the Trees" is a wide ranging volume that lingers at the border between the genre of folklore and practical witch history. What makes Gary's work special is that in retelling these old tales she dissects them with commentary, illustrating the important variables that relate to practical witchcraft.

A chapter on Cecil Williamson, founder of the Museum of Witchcraft, is a long overdue addition to the history of folklore in the UK. Williamson's contribution to the study of folk tradition and craft practice are too often overlooked in the narrative of craft history.

The final portion of the book, 50 or so pages, is "A Black Book of Devonshire Magic" and outlines dozens of spells, charms, and rituals from a practical viewpoint derived from Devonshire folkwitch traditions. As with all books from publisher Troy Books the binding is beautifully done, with a copper metallic lettering on green cloth boards. The layout is well presented, with beautiful illustrations by Gary and wonderful black and white photography by Jane Cox. It's a handsome volume that glints on my bookstack in the evening light everyday.

In "Silent as the Trees" Gary has captured the form of the folklore collection, and yet has managed to make it feel contemporary as well as practical. A perfect edition for fans of folklore, traditional witchcraft, and Devonshire history.

Get your copy at Troy Books here:

"Silent as the Trees"

Gemma Gary

#skeptical occultist#occult books#grimoires#grimoire#witch#witchcraft#traditional witchcraft#gemma gary#troy books#cornish witchcraft#devonshire#folklore#folkwitch#cunning craft#folkmagic#sidhe#moors#black dog#spirit#conjuration#warding#blasting#curse#magic#alchemy#necromancy#lhp#ghost#blackbook

483 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Recommendations

1. Traditional Witchcraft: A Cornish Book of Ways by Gemma Gary

2. The Black Toad: West Country Witchcraft and Magic by Gemma Gary

3. Silent As the Trees: Devonshire Witchcraft, Folklore & Magic by Gemma Gary

4. The Crooked Path: An Introduction to Traditional Witchcraft by Kelden

5. Honoring Your Ancestors: A Guide to Ancestral Veneration by Mallorie Vaudoise

6. Seven Spheres by Rufus Opus

7. Secrets of Planetary Magic by Christopher Warnock

8. Magic Simplified by Draja Mickaharic

9. Traditional Magic Spells for Protection and Healing by Claude Lecouteux

10. The Complete Lenormand Oracle Handbook by Caitlin Matthews

11. A Deed Without a Name by Lee Morgan

12. Pow-Wows; or, Long Lost Friend by John George Hohman

13. The Witch's Shield by Christopher Penczak

14. The Flame in the Cauldron: A Book of Old-Style Witchery by Orion Foxwood.

15. Carmina Gadelica by Alexander Carmichael

16. Magika Hiera: Ancient Greek Magic and Religion by Christopher A. Faraone and Dirk Obbink

17. Dictionary of Ancient Magical Words and Spells by Claude Lecouteux

18. Folk Witchcraft by Roger J Horne

19. Magic in the Ancient Greek World by Derek Collins

20. Orphic Hymns Grimoire by Sara Mastros

21. Protection and Reversal Magick by Jason Miller

22. Dionysus: Myth and Cult by Walter F. Otto

23. The Elements of Spellcrafting by Jason Miller

24. Viridarium Umbris: The Pleasure-Garden of Shadow by Daniel A. Schulke

25. Restless Dead: Encounters between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece by Sarah Iles Johnston

412 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gemma Gary. Silent as the Trees: Devonshire Witchcraft & Popular Magic. Troy Books, 2020. Black Edition. 222 pages. Limited to 125 hand-numbered copies (#72/125).

https://www.ebay.com/usr/arcane-offerings

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In this debate, parties were blamed for encouraging a form of herd mentality in politics. George Savile, 1st Marquess of Halifax, likened parties to “an Inquisition, where Men are under such a Discipline in carrying on the common Cause, as leaves no Liberty of private Opinion.” More fundamental was the concern that parties exacerbated division and turned neighbors into enemies. As Joseph Addison wrote in the Spectator, “I am sometimes afraid that I discover the seeds of civil war in these our divisions.” What made things worse was that partisanship often seemed random. “There is a sort of Witchcraft in Party, and in Party Cries, strangely wild and irresistible,” wrote Thomas Gordon, co-author of Cato’s Letters. “One Name charms and composes; another Name, not better nor worse, fires and alarms.”

Most astute political commentators, however, realized that parties were not going away. They were a price worth paying for parliamentary politics and ultimately a sacrifice for political freedom. A state without parties was a state without liberty, as Montesquieu put it in his history of the Roman republic. A government without parties is an absolute government, since rulers without opposition are autocrats. Opposition, to be effective in a parliamentary system or in any system with an assembly, must be organized.

(…)

Rapin argued that the two parties in Britain, the Whigs and Tories, represented the two pillars of the mixed and balanced constitution – parliament on the one hand, and monarchy on the other – and that both parties were necessary for the equilibrium between them. They were likewise necessary for balance in the religious sphere, which was as important as secular matters in public life at the time. The Tories favored the Church of England, the Whigs toleration for Protestant Dissenters, and the only way to achieve a sustainable equilibrium between the two extreme positions was competition and mutual checking and balancing between the parties. These parties would alternate in government and take turns to hold each other to account when out of power.

The Scottish Enlightenment thinker David Hume (1711-76), who read Rapin at an early age, wrote at length about party in general and in its British guise in a series of essays published as Essays, Moral and Political in different instalments starting in 1741. Hume believed that parties – or “factions,” terms he used interchangeably – based on “principles” were particularly pernicious and unaccountable. Religious principles had the potential of making people fanatical and ready to both proselytize and persecute dissidents. Because they were more transparent and less extreme, parties based on “interests,” meaning different economic interests, were more tolerable. His early essays on party, “Of Parties in General” and “Of the Parties of Great Britain” (both 1741) treated the phenomenon as inevitable since the British parliamentary system produced to Court and Country parties, or parties of government and opposition.

In later writings, Hume suggested that party politics could be necessary and possibly salutary for political societies. In “Of a Coalition of Parties” (1758), Hume opened by arguing that it may be neither possible nor desirable to abolish parties. This essay was an apologia for his own History of England (1754-61). In this earlier work, Hume had written that “while [the Court and Country parties] oft threaten the total dissolution of the government, [they] are the real causes of its permanent life and vigour.”

(…)

In the pages of the Craftsman, Bolingbroke justified the existence of an oppositional “Country party.” In Bolingbroke’s formulation, it would function as a constitutional party, and he argued that the government of the day (Walpole’s Whigs) had betrayed the core principles of the constitution by corrupting parliament and making the legislature dependent on the executive. In A Dissertation upon Parties (1733-4), Bolingbroke separated the political landscape into three camps: 1) enemies of the government but friends of the constitution, referring to his own Country party; 2) enemies of both, meaning the Jacobites; and 3) friends of the government but enemies of the constitution, that is, the Court Whigs. Only the first category was a legitimate party, whereas the other two were factions, according to Bolingbroke. To save the nation, he argued, the enemies of the constitution had to be opposed, and opposition must be systematic and concerted.

Burke, a Whig later in the century, was not favorable towards Bolingbroke’s Country Tory politics and even less so towards his Deistic and anti-clerical religious writings. Burke continued, however, to distinguish between party and faction in even more forceful terms than Bolingbroke, as he sought to justify his party connection, the Rockingham Whigs, in the 1760s and onwards. To defeat what he viewed as the Court cabal and the abuse of the royal prerogative in the reign of George III, Burke believed that party connection was essential to restore Britain’s mixed and balanced constitution. “When bad men combine, the good must associate,” Burke wrote in Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents (1770), “else they will fall, one by one.” Politics was not about having a clean conscience but about making a difference, and party was a necessary instrument that could unite power and principle. As he famously defined party: “Party is a body of men united, for promoting by their joint endeavours the national interest, upon some particular principle in which they are all agreed.” At the heart of this definition is a distinction between party and faction. Parties for Burke are devoted to promoting an understanding of the national interest, and they are united by principle, and not exclusively by interest, although that can be a supporting principle.

The core of Burke’s party was made up of major Whig aristocratic families such as Cavendish and Devonshire. In the Present Discontents, however, Burke stated that he was “no friend to aristocracy,” in the sense at least in which that word is usually understood, that is to say, as “austere and insolent domination.” What the Whig aristocrats possessed was property, rank, and quality which gave them a degree of independence, and this enabled them to stand up to both the Court and the populace. In this sense, Burke’s conception of party was indeed aristocratic, but it was not aristocracy for its own benefit but for the sake of the whole, and part of his defence of Britain’s mixed and balanced constitution.

The British party debate left an ambivalent legacy among early American political actors and thinkers. The most famous discussion of party and faction in the early American republic is found in James Madison’s Tenth Federalist. In this canonical essay, Madison argued that differences and “mutual animosities” could not be extinguished in free governments. He further agreed with Hume that parties of interest were generally more peaceful and governable than parties united and actuated by passion. His solution to party violence resembled Hume’s argument from “Of a Perfect Commonwealth” (1752): the effects of faction can be better controlled in larger states and federations than in city states. Thanks to the greater size and the scope of the United States, the impact of each faction would be mitigated.

A less philosophical but comparably historically significant party argument surfaced in the 1790s. After Madison and Alexander Hamilton had co-operated as Publius in the Federalist Papers, they became rivals as the early American republic split into two political parties: Republicans and Federalists. Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation in 1793 led to a sharp disagreement between the two on the question of executive power in the constitutional order. In short, Madison associated with his old friend and fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of State, to oppose Treasury Secretary Hamilton’s centralizing ambitions. In this political environment, a party argument emerged which had more in common with Bolingbroke, and to an extent Burke, than it did with Hume. This was the idea of partisan opposition. The ideal for Jefferson and other opponents of the Federalists was national unity. However, because of what they perceived as the corruption of Federalists such as Hamilton, an opposition party in the shape of the Republican Party was necessary to defeat the enemies within. Jefferson believed that the Hamiltonians and the Federalists were monarchists, and he viewed the 1790s as an ideological battle between liberty and tyranny. In this struggle, partisanship became a necessary evil.

Many eighteenth-century thinkers contended that constitutional party politics were sometimes necessary to save liberty from authoritarianism and corruption. Indeed, party politics itself was a sign of liberty, since it enabled isolated individuals to participate, and thus gave life and vigor to politics. Such politics could generate “harmonious discord” and be as close an approximation of the common good as the imperfections and diversity of human society permit. But for this to materialize, the political debate must retain a degree of civility. Admittedly, most eighteenth-century partisans fell as short as we moderns in this regard. This is the reason why Hume sought to persuade partisans “not to contend, as if they were fighting pro aris & focis,” literally for altars and hearths, or for God and country.

For Hume, it was also crucial that parties were “constitutional.” According to him, “[t]he only dangerous parties are such as entertain opposite views with regard to the essentials of government,” be it the succession to the throne as in the case of the Jacobites, or “the more considerable privileges belonging to the several members of the constitution,” as with the great parties of the seventeenth century. On such questions there should be no compromise or accommodation since that type of party strife could turn into armed conflict. Eighteenth-century politics retained a civil-war edge on both sides of the Atlantic. Recent events, and indeed the nature of party politics itself, have shown that this is a history and a debate we forget at our peril.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Beltane Series: Walpurgisnacht

Walpurgisnacht or Hexennacht is celebrated from the eve of April 30th to May 1st. This is a traditional Germanic festival associated with witches. “Hexe” is the German word for “witch”, and “nacht” is the German word for “night”. So, the name translated to “witches night”. It’s more common name, Walpurgisnacht, is associated with the Christian feast of Saint Walpurga. This is a night that has striking similarities to the modern Halloween. On the Wheel of the Year, it falls exactly opposite of Samhain, making it the perfect time to feel the thinning of the veil and celebrate traditions of this time. In this essay, I will be covering both traditions.

It is common knowledge that the early European peoples celebrated the coming of spring. It meant the long winter was over, and abundance and warm weather were soon coming. In German folklore, it is said that witches and warlocks also welcomed the coming of spring by flying around Germany on broomsticks. On the eve of April 30th, they met on the highest peak in the Harz Mountain where bonfires would be lit and a ceremony took place to welcome in the spring. This peak is called Blocksberg Mountain, and has long been associated with witches in Germany. It is more than likely that these “witches” were simply pagans looking for a secluded place to practice their religion in peace, away from the prying eyes of the people and the church.

Over time, these traditions shifted. What once was a ritual to welcome spring, became a ritual to chase away evil spirits. You see, the villagers were afraid of the witches up in the mountains. They believed that witches and evil spirits travelled through the land on this night with ill intent. This is the parallel to the thinning of the veil at Beltane, exactly 6 months away from Samhain when the veil between worlds is the thinnest. In order to chase away these witches and bad spirits, the men of the village would make as much noise as they could to scare them away. This involved shooting shotguns, banging pots and pans together, and any other number of noisy activities. They also lit bonfires to light up the night, and discourage spirits who were sensitive to light from entering their village. Sprigs of foliage were blessed and hung above doorways to block the evil spirits from entering, and traditional bread and honey was left at the edges of town as offerings to the hellhounds.

So why was April 30th such an important night? Well, Pagan and Christian customs seem to have been tangled together. In medieval times, April 30th was an important half-way point that marked exactly 6 months until All Saint’s Day, which is the Christianized version of the pagan sabbat Samhain. This was an extremely important date for pagans, and was called the festival of Beltane. This was not to last, and the Christian church imposed a new holiday over Beltane, which was supposed to help the pagans convert to Christianity. Instead of the ancient Beltane, they honored Saint Walpurga, and called in Walpurgisnacht.

So who was Saint Walpurga, and why was she so important? She was born in Devonshire, England in 770AD. When she was young, she was sent to Germany as a missionary, and quickly became the abbess of the convent in Heidenheim. During her time here, she baptized many pagans into the Christian church. After her death, it is said that a healing oil began seeping between the stones of her tomb. This was the miracle that transformed her into a saint, and her body was subsequently split into many pieces and sent throughout Europe as relics. Because she died on May 1st, this is the day that became her holy day, and the eve of May 1st is when her feast was celebrated. She is known as the patron saint of coughs, sailors, hydrophobia, and storms. Many Christians in the Middle Ages also prayed to her to shield them against witchcraft, which was especially associated with her feast and the traditions of the day.

It is interesting to look at the similarities between Saint Walpurga and pagan traditions as well. Saint Walpurga’s symbols are grain, dogs, and the spindle. These same symbols are found in pagan tradition. Grain is a traditional symbol of the harvest, dogs are considered traditional familiars for Germanic Goddesses, and the spindle is associated with Frau Holda from the famous fairy tale. This made it easy for pagans unwilling to convert to say they were honoring Saint Walpurga, when instead they were honoring the old Germanic Gods. Though the Christian Feast of Saint Walpurga had different beliefs than the pagan traditions, there were other striking similarities. For one, the tradition of hanging sprigs of foliage over doorways was observed by Christians as well as pagans. Though some traditions remained the same, most of the Christian ones were different. People often made pilgrimages to her tomb in Eichstätt, where they would purchase vials of Saint Walpurga’s oil.

Now let’s talk about some of the customs of Walpurgisnacht. These traditions are very similar to those of Beltane. After the long, cold winter, it is only natural that the coming of spring should be celebrated. This was especially important to early Germanic peoples who lived in a cold place in the world, where winter carried with it a serious risk of death. To welcome back the warmer part of the year, they built great bonfires, and partook in a lot of song and dance reminiscent of that around the maypole for May Day. There are however, a few traditions not reflected in those of Beltane. These are the ones I find to be the most interesting! Remember when I said that this was also considered a witches night? Well, it was tradition to ride broomsticks between balefires or jump over them. It was also a time to burn old brooms in the fire. This is possibly the origin of the myth that witches fly on broomsticks. Anything old or broken was also burned in these fires, symbolically and physically cleaning the old energy from the house. Straw likenesses were created and adorned with illness and other bad things and symbolically burned in the fires as well, ridding the person of these bad things in their lives.

Though these were the traditional Walpurgisnacht traditions, they have changed once again with the times, and modern celebrations look different than they once did. The major difference between this celebration and the Christian celebration is that it is secular, and no longer associated with the Catholic Saint Walpurga. The fear of witches has been largely dispersed in modern times. More and more people are embracing witchcraft either through practice, media, or any number of different ways. With this new view, Germany’s celebration of Walpurgisnacht has turned into a sort of second Halloween in Germany. People come to the Harz Mountains dressed as witches, warlocks, or other magick wielders. Here, they dance and celebrate alongside others and large bonfires. The largest celebration is held in the Hexentanzplatz, which is a plateau near the town of Thale. Though this is the largest celebration, Walpurgisnacht is celebrated across Saxony.

Southern Germany sees Walpurgisnacht a little differently. Here it is seen as a night of pranks, kind of like April Fool’s Day in America. In Finland, Walpurgisnacht is called Vappu, and is one of the country’s most important holidays. It was originally celebrated here only by the upper class, but quickly trickled down and became especially popular with university students. In Berlin, Walpurgisnacht is a traditional night to start riots and protests, as it is closely associated with the German Labor Day. These protests usually begin in the Mauerpark where the remains of the Berlin Wall sit on display as a reminder. This is a new association with Walpurgisnacht, but an important cultural association to the German people.

Unfortunately, the negative connotations of Walpurgisnacht are still present in some cases. In the Czech Republic, this night is known as “Paleni Carodejnic”, which translated to “Burning of the Witches”. Though there is no actual burning of witches, the negative connotation remains. It is tradition here to build bonfires as well and burn images of witches throughout the night.

Walpurgisnacht appears many times in famous literature. The first instance introduced the myth of the witches, and was called “The Blocksberg Performance” by Johannes Präetorius. After this first introduction into mainstream entertainment, Walpurgisnacht found its way into other literature and music. The most well known reference is Goethe’s play “Faust”. Walpurgisnacht is the name of a scene in part one of Faust and part two. Other famous examples of Walpurgisnacht in literature include “The Magic Mountain” by Thomas Mann, “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” by Edward Albee, and “Dracula’s Guest” by Bram Stoker.

Obviously, there are many traditions associated with Walpurgisnacht. It is especially pertinent to those of us who practice witchcraft due to the rich history of pagan and witch traditions on this night. This is just another way to further celebrate Beltane and the welcoming of spring. Modern witches can use this night to feel more witchy and to connect to their pagan and witch ancestors.

Works Cited:

Melanie Marquis (2018), Beltane: Rituals, Recipes, and Lore for May Day, Llewellyn, Fourth Edition, Print, Pages 39

Raven Grimassi (2001), Beltane: Springtime Rituals, Lore & Celebration, Llewellyn, Print

Various (Various), Walpurgis Night, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walpurgis_Night

Karen Anne (April 28th 2017), What is Walpurgisnacht? And How Did an English Nun Become Associated with Witches?, German Girl in America, https://germangirlinamerica.com/what-is-walpurgisnacht/

DHWTY (November 9th 2018), Walpurgis Night: A Saint, Witches, and Pagan Beliefs in Springtime Halloween for Scandinavia, Ancient Origins, https://www.ancient-origins.net/history ... ht-0010965

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week we got lots of things back in stock at the PBW Witch Shop! Also, if you were wondering where we get our ribbon and yarn we use to secure items inside packages, I just got a giant back of yarn from a thrift store yesterday. Some if it is super fun stuff!

Back in stock!

Weird Walk Number Two & Number 3

54 Devils by Cory Thomas Hutcheson

Folk witchcraft by Roger J Horne

Memento Mori: A Collection of Magickal and Mythological Perspectives on Death, Dying, Mortality, and Beyond

Crooked Path: An Introduction to Traditional Witchcraft by Keldon

A bunch of Troy Books back in stock!

Traditional Witchcraft: A Cornish Book of Ways by Gemma Gary

Silent as the Trees: Devonshire Witchcraft Folklore and Magic by Gemma Gary

The Black Toad: West Country Witchcraft and Magic by Gemma Gary

The Devil's Dozen: Thirteen Craft Rights of the Old One by Gemma Gary

Treading the Mill:Workings in Traditional Witchcraft by Nigel Pearson

#traditional witchcraft#folk magic#folk witchcraft#witchcraft#gemma gary#divination#weird walk#memeto mori#witchcraft books#the black toad#crooked path#witchy books#pagan books#mauro pagani

85 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Vixen Tor is an eerie and towering mass of granite on Dartmoor. Legend tells that this desolate spot was once inhabited by an evil witch named Vixiana, who dwelt within a cave beneath the tor. It would seem that her powers as a witch were derived from the Devil, and that to maintain these she was keen to give regular human sacrifices unto her dark master. To do this, Vixiana would climb to the top of the rocky prominence, and there sit and cast her eye intently about the moor, looking out for any travelers.

When a traveler was unfortunate enough to be spotted by Vixiana, she would conjure forth a thick and swirling mist to descend, leaving the traveler confused and unable to find their way. Then, Vixiana would call out to them, as though she were guiding them to safety, however, she was instead drawing them towards a treacherous boggy area where man had lost their lives. Once caught, there was nothing the poor soul could do to escape, and Vixiana would delight in their desperate cries for help as they slowly sunk beneath the deep and sucking bog.

One day, however, the witch spied a potential victim who turned out to be no ordinary moorman, but a cunning man well versed in the magical artes. He had heard tell of the evil witch, and the many lost souls she had lured to their deaths, and so he set out that day intent on putting an end to her wicked ways. As usual, the diabolical mist was conjured down and surrounded the cunning man, who took out of his pocket a magical ring and placed it upon his finger, whereby he became invisible.

Vixiana began her deceitful calls to safety, hoping as usual to draw the man forward towards the tor and into the bog. However, the cunning man deviated, until he found his way out of the mist, and headed on round to the other side of the tor and began to climb. When he reached the top, he found the witch desperately straining to hear any sign that her trap had caught its victim. She sat there both infuriated and puzzled as to why she could not yet hear any hopeless cries for help, when the invisible cunning man rushed forward and pushed the evil creature from her perch to fall to her death below. Travelers could at last pass the tor in safety, however, to this day Vixiana's furious and tormented ghost is said to be heard shrieking and wailing around that foreboding tower of rock.

Gemma Gary - Silent as the Trees: Devonshire Witchcraft, Folklore & Magic

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Channeling her chaotic energy this year.

From Gemma Gary's "Silent as Trees. Devonshire Witchcraft, Folklore & Magic"

#come to me#what an inspiration#plucky maids summoning chicken demons is a 2020 mood#gemma gary#devonshire folklore#this is more of a ghibli adventurousness vibe#chicken keeping

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Sir Francis Drake:

The Elizabethan sea captain, privateer and navigator, temains of course a figure of global fame, particularly in connection with the 1588 defeat of the Spanish Armada His connection with Devon is also well known, but less well known is his legendary status as a powerful magician, witch, and leader of Devonshire covens.

In c. 1540, Sir Francis Drake was born in the west Devon town of Tavistock. In 1580 he purchased Buckland Abbey, a seven hundred near Yelverton on the south-western edge of Dartmoor. Anyone who was seen to have made great achievements and remarkable feats, in the days when witchcraft was widely believed in, was likely to have their successes put down to magic, and some form of pact with spirits. Such was certainly the case with Drake, who was said to have sold his soul to the Devil in exchange for victory and success, and there are numerous tales and traditions of his magical powers and his working relationship with the spirit world. One such tale concerns his alterations to Buckland Abbey.

During the building work, the workmen would down their tools at the end of the day, only to return in the morning to find the previous day's work undone and interference from the spirit world was suspected. Drake decided to find out for himself what was happening and that he would spy on the culprits. As night fell, he climbed a great old tree overlooking the house, and waited. When midnight came, out of the darkness emerged a horde of marauding demons, gleefully clambering about over the house and dismantling all the stonework put up during year old manor house the day.

Loudly, Drake called out 'Cock-a-doodle-do!" in the manner of a cockerel, crowing in the dawn. The mischievous spirits suddenly stopped their shenanigans in confusion, and Drake lit up his smoking pipe. As they spotted the glowing light in the tree, the spirits believed the sun was coming up and departed back into the shadows from whence they came. Presumably, they were so embarrassed at having been so easily fooled that they never returned, and the building work continued unhindered.

Traditionally housed in Buckland Abbey, is Drake's legendary drum. Beautifully painted and decorated with ornate stud-work, the drum is popularly said to have accompanied sir Francis Drake on his voyages around the world. As he lay on his deathbed on his final voyage, it is said Drake ordered that his drum be returned to England and kept at Buckland Abbey, his home. Here, the drum should be beaten in times of national threat, and it will call forth his spirit to aid the country. Indeed, there have been numerous occasions when people have claimed to have heard Drake's drum beating, including during the English Civil War and the outbreak of the Frist World War.

In 1918, a celebratory drum roll was reported to have been heard aboard the HMS Royal Oak following the surrender of the Imperial German Navy. An investigation was carried out with the ship being thoroughly searched twice by officers and again by the captain. As neither a drum nor a drummer could be found, the matter was put down to Drake's legendary drum.

During World War II, much weight was added to the drum's legendary protective influence, particularly over the city of Plymouth which, it was said, would fall if the drum was ever removed from its home at the Abbey. When fire broke out at Buckland Abbey in 1938, the drum was removed to the safety of Buckfast Abbey.

Bombs first fell on Plymouth 1940, and again in 1941 in five raids which reduced much of the city to rubble. In 1172 civilians lost their lives in the 'Plymouth Blitz’. Drake's drum was returned to Buckland Abbey, and the City remained safe for the remainder of the war.

Like many reputed witches and magicians, Sir Francis Drake was said to possess a familiar spirit to aid him in his work. The presence and influence of this spirit turns up in the stories surrounding his marriage in Like 1585 to Elizabeth Sydenham, daughter of Sir George Sydenham the Sheriff of Somerset. Some sources that Elizabeth's parents we disapproving of the union due to Drake's reputed involvement in the black artes and that the marriage took place shortly before he departed for a long voyage. After no news had been heard from Drake for a number of years, Elizabeth's parents took the opportunity to persuade her to declare herself a widow. Another account states that Drake's departure for his voyage took place before the wedding. In both versions however, The Sydenhams arranged for their only child to be married instead to a wealthy son of the Wyndham family.

It is said that Drake had left his familiar spirit to keep watch over his beloved while he was away, and that the spirit made him aware of her planned wedding to another man. On the day of the wedding, there was a loud clap of thunder, and a meteorite came crashing through the roof of the church. Some said that this had been a cannonball shot from Drake's ship to halt the wedding. In any case, it was taken as a bad omen against the wedding between Elizabeth Sydenham and the son of the Wyndham family.

The meteorite itself, known as ‘Drake's Cannonball' has been housed at Combe Sydenham ever since.

Another popular legend featuring Drake's reputed and remarkable magical abilities concerns the creation of the Plymouth Leat. As Plymouth had suffered problematic water shortages through dry summer months, it is said that Drake took his horse and rode out onto Dartmoor to search for a water source. Upon finding a small spring, he uttered a magical charm over it and it burst forth from the rocks as a flowing stream. Drake galloped o on his steed, commanding the flowing waters has he die so to follow him back to the city. Today, the Plymouth Leat has its beginning at Sheepstor on the western side of Dartmoor and ends in a reservoir just outside the city.

There are, of course, a number of traditions of magic and witchery surrounding Sir Francis Drake's defeat of the Spanish Armada. He is said to have presided as Man in Black' over a number of covens, and that during the threat of invasion, he and his covens assembled on the cliffs at Devil's Point to the south west of Plymouth. There they performed magical operations to conjure forth a terrible storm to destroy many of the Spanish ships. It is said that to this day that Devil's Point is haunted by Drake and his witches, still convening there in spirit form.

Another, more famous legend, tells of Sir Francis Drake playing a game of bowls on Plymouth Hoe when news was brought to him of the approach of the Spanish fleet. In one version he is said to have casually continued his game to its conclusion which, it has been suggested was a magical spell; with the bowls he was scattering with his drives representing the invading fleet. In another version, he stops his game to order a hatchet and a great log to be brought to the Hoe. He then proceeded to chop the wood into small wedges whilst uttering a magical charm over them as each one was thrown into the sea, and as each one hit the water they transformed into great fire ships; sailing out to burn the Armada.

The folklore surrounding Sir Francis Drake also includes his deep association with the Wild Hunt. Sometimes he is seen as leading the ghostly pack of Wisht Hounds', and at others he is the riding companion of the Hunt's more traditional leader; the Devil. In some Stories Drake rides in a spectral black coach, drawn by black, headless horses and followed by a great pack of black, otherworldly hounds with eyes burning red in the night. Sometimes his coach horses are seen with their heads, and have eyes blazing like hot coals.

One such story tells of a young maid, running desperately across the moors to escape an evil man on horseback she is being forced by her adoptive family to marry. Upon reaching a remote crossroads, and collapsing there in exhaustion, the ghostly pack of hounds and horse drawn coach approach from the darkness. Stopping at the crossroads, a man steps out of the coach, and the young woman recognises him to be the ghost of Sir Francis Drake.

He enquired of the young woman, why she was out on the moor alone and in a state of desperation and exhaustion, and she told him of her plight. Drake pulled from beneath his cloak a box and a cloth, and gave these to the young woman telling her to continue gently on her way, and not, under any circumstance, to look back.

The maid did as she was instructed, and when her pursuer reached the crossroads, he asked of the dark figure in the coach if he had seen a young maid passing by. Drake asked the man to step into his coach, and as he did, its door shut fast and the coach and hounds disappeared back into the darkness. The man was never to be seen again, and it is said that when morning came, his horse was found at the remote crossroads and had apparently died of fright.

According to research by the Devonshire cunning man Jack Daw, there is said to be a family line of Pellars, descended from the girl who encountered the spirit of Sir Francis Drake on the Moor. Their powers, it is claimed, are derived from the gift of the box and cloth he had given to her on that night.”

—

Silent as the Trees:

Devonshire Witchcract, Folklore & Magic

by Gemma Gary

#sir Francis drake#Gemma Gary#silent as the trees#Devonshire witchcraft#Devonshire magic#traditional withcraft#witchcraft#magic#quote

68 notes

·

View notes