#I admire the james baldwin quote I used just to be clear

Text

The real reason that nonviolence is considered to be a virtue in Negroes—I am not speaking now of its racial value, another matter altogether— is that white men do not want their lives, their self-image, or their property threatened. One wishes they would say so more often. At the end of a television program on which Malcom X and I both appeared, Malcolm was stopped by a white member of the audience who said, “I have a thousand dollars and an acre of land. What’s going to happen to me?” I admired the directness of the man’s question, but I didn’t hear Malcolm’s reply, because I was trying to explain to someone else that the situation of the Irish a hundred years ago and the situation of the Negro today cannot very usefully be compared. Negroes were brought here in chains long before the Irish ever thought of leaving Ireland; what manner of consolation is it to be told that emigrants arriving here—voluntarily—long after you did have risen far above you? In the hall, as I was waiting for the elevator, someone shook my hand and said, “Goodbye, Mr. James Baldwin. We'll soon be addressing you as Mr. James X.” And I thought, for an awful moment, My God, if this goes on much longer, you probably will.

James Baldwin - The Fire Next TIme

Man, man I followed a chain of links and found that paper, "Decolonization is not a metaphor" and I read like three quarters of the dang thing before I realized that we all already got mad at it because it is morally insane.

This is less about the idea of a literal mass expropriation of land, and therefore wealth, from the current owners in the US, which A) is not going to happen any time soon (Land acknowledgements are acknowledging that you ain't giving the damn land back to anybody); and B) if you tell me that the land I live in will be given to the local indigenous people my first question is,

"So will they be raising the rent as much as the previous owners did?"

What's morally insane is... Okay, no, I object to the idea that the question is irrelevent, although the authors of the paper do say fairly explicitly that it is wholly irrelevant.

What I find morally insane about the paper is not the idea that the authors wish to ignore my feelings on the matter, but the very strong suggestion that I should train myself not to have an opinion on the matter.

I linked the paper up there, I don't want to summarize too much, but essentially, it posits a triad of indiginous person/settler/slave, which in the US context maps more or less onto Native American/white/black.

Indigenous peoples are those who have creation stories, not

colonization stories, about how we/they came to be in a particular place - indeed how we/they came to be a place. Our/their relationships to land comprise our/their epistemologies, ontologies, and cosmologies. For the settlers, Indigenous peoples are in the way and, in the destruction of Indigenous peoples, Indigenous communities, and over time and through law and policy, Indigenous peoples’ claims to land under settler regimes, land is recast as property and as a resource.

Settler, in this paper, is not meant very literally. The settlement of the US involved not just the theft of land specifically, but the creation of certain narratives about who has rights to use land and in what way. My ancestors in this country go back hundreds of years but they are, to our best knowledge, legally white, and I am therefore a settler in the sense of having a certain relationship to certain racial and conceptual categories.

Don't get me wrong: the history of this country makes at least certain versions of that idea very plausible.

So what am I supposed to do with that?

If I take the authors of this paper morally seriously, (And once I took similar views very seriously, in some ways I still do) where does that put me?

Settlers in a country like the US do not and cannot have a creation story about how we came to be in a certain place. That I am a settler in the US very much does not make me somehow indigenous to Brittany where many of my ancestors come from; I do not have a story of how my people came to be in Brittany or Great Brittain any more than I have one for how we came to be in the USA.

What I can become, perhaps, is an immigrant:

Settlers are not immigrants. Immigrants are beholden to the Indigenous laws and epistemologies of the lands they migrate to.

Here's a question: How, as a settler, would I acquire the moral right to influence the laws and epistemologies of whichever land I should migrate to?

I don't have the legitimizing moral narratives that indigenous peoples do, am I doomed to simply occupy a subordinate place in a new hierarchy?

The authors, I should note, explicitly say no, but also explicitly say that they basically can't explain why not and so I just shouldn't worry about the question for now.

Honestly I think a tremendous amount of American history involves attempts to deal, psychologically, with the fact that the question of who has power and who doesn't has been decided in a way which is at odds with most of our country's moral pretensions. I think that shame has been one of the great psychological factors driving white attitudes in the US, both racist and anti-racist.

Think about what the "moves to innocence" that the authors delineate would mean if you took their moral position seriously. Those moves to innocence are attempts, I am quite sure, to find a way to act in the world for your own benefit without feeling shame. The indigenous person can ask for the control of the land they occupy without shame; for the settler, even to occupy the land is to make yourself part of a shameful process.

"Decolonization is not a metaphor" treats the desire to express oneself without feeling shame around it as essentially a distraction.

The settler is simultaneously morally obligated to exercise a tremendous amount of power and effort, because how could the non-metaphorical expropriation of all US land and the end of the USA as a functioning state take anything other than a tremendous amount of power and effort, but also to have no thought at all about what the ethical exercise of power from a settler would look like.

It is morally imperative that the settler begin to act and use his power in a moral way and at the same time the very question of how the settler would do so is understood as a frustrating distraction from more important questions.

The only possible response for a person who takes this seriously and conceives of themselves as a settler is to just fall back on an entirely incoherent self-image because the demands being made of them are fundamentally incoherent, to feel a kind of shame without shame.

I have probably over-explained this and yet not quite gotten to the central problem. I really disagree with this paper, and I think it is fundamentally unserious and fundamentally poisonous.

Not because the authors propose a massive reorganization of land but because they are utterly unwilling to think about what that would mean on any level whatsoever.

#politics#discourse#Yes I still am very angry at this stuff#I admire the james baldwin quote I used just to be clear

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photo: “NO TITLE EXISTS” - photoshoot with photographer Dean Martin

Day 178: “The Artists Struggle for Integrity”

Date:

4-17-19

Mood:

Poet

Actor:

Sent for jobs, recorded voiceovers, kept on the up and steady. Yeah I’ve been thinking more and more about the “change” I’m gonna make. Too many middle men between me and what’s right.

Filmmaker:

Clay! Oh my good god Clay! I’m tellin you. I’m in the zone. It feels so damn good. I really step into that story. I’m with those characters. I actually started nailing down specifics today, small details in story and in character.. you know, I sometimes don’t even know where the story is gonna take me. I try outlining, and I do to a certain degree. But even with that I’m letting the story speak to me. It’s so much pressure off of myself. I’m in the 3rd Act writing as we speak. And I really think I landed my ending for the film. I mean, it’s been there but not clear. Today. It became clear. Like a damn breaking. I wrote for HOURS upon HOURS today because it was flowing. There was music there was rhythm there was movie. Now tomorrow I give clay a break and focus on some short films..

Speaking of I dabbled with that today too. Not much just touched on a “Time Travel”🧭 🧳Idea that hit me while I was in the middle of working out this past week. I elaborated a bit on the idea. I’m tellin you. If I can do these ideas justice. I’m gonna have pieces of art I can be very proud of. Got some exciting ideas planned. 😆

Final Thoughts:

James Baldwin. He is rapidly becoming one of my favorite novelist. I began my writing today listening to one of his many lectures. That’s how I started my writing ✍🏽. No words on the page. No music in the background. Just listening to a profound professional speak clearly and honestly about the necessity of Artist in our lives..

Here are a few quotes of his that I’d like to share..

“The Artist is no other than he who unlearns what he has learned, in order to know himself.”

“The poets (by which I mean all artists) are finally the only people who know the truth about us. Soldiers don’t. Statesmen don’t. Priests don’t. Union leaders don’t... Only poets.”

..I truly can’t do the man enough justice. He inspired me a lot today from a lecture he gave as writer and an African American man in 1962. ✊🏿

Today was filled with knowledge. Quentin Tarantino interview on writing and story, Nils Frahm as my composer for the evening, watching Ricky Gervais in his new Show “After Life”, a 10 Minute Freestyle from Black Thought that was genuinely the greatest freestyle known to man, Creating shots with my camera prepping for my short films.. really soaking up so much knowledge from people I respect and admire. And coming up with an ending for my feature that had me in tears. I actually was so filled with emotion today I broke down myself.. It was just a really great day. And I’m so grateful for it.

Thank you today. Let’s do this shit again real soon.

#joshmcclenney#artist#poet#poetry#james baldwin#actor#writer#filmmaker#director#acting#actors#actorslife#artists on tumblr#commercials#directing#film#filmfestival#films#art#filmmakers#film photograhers#voice over#voice acting#movie#movies#hollywood#write#writeblr#writers#writing

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

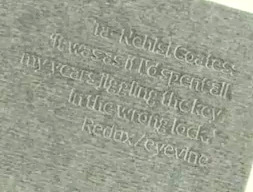

I rotated and adjusted the lighting on that quote from the bottom left, to find what article it was referring to, since it’s the cover page of a newspaper section.

It reads:

Ta-Nehisi Coates: “It was as if I’d spent all my years jiggling the key in the wrong lock.”

The editor who put that quote on the cover page seems to have misquoted the article though, because the actual quote from the article is, “It was as if I had spent my years jiggling a key into the wrong lock.”

Married with a young child, he possessed intellectual curiosity and the gift of a wordsmith. He produced an essay about Bill Cosby that caught attention and led to a relationship with the Atlantic magazine, where he is now a national correspondent. His ascent coincided with Obama’s and a new world of possibilities. “It was as if I had spent my years jiggling a key into the wrong lock. The lock was changed. The doors swung open, and we did not know how to act.”

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/oct/08/ta-nehisi-coates-our-story-is-a-tragedy-but-doesnt-depress-me-we-were-eight-years-in-power-interview

Below is a cut and paste of the article in case you can’t access that link.

Ta-Nehisi Coates

The Observer

Ta-Nehisi Coates: the laureate of black lives

Coates’s eloquent polemics on the black experience in America brought him fame and the admiration of Barack Obama. Here he talks about the rise of white supremacy – and why Trump was a logical conclusion

Ta-Nehisi Coates is short on sleep. He did five interviews yesterday to promote his new book, We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy. Today there was another at 7am, then surgery “to get a little thing removed” from his neck. As his tall frame appears in the doorway of an office at his New York publisher, a bandage is visible above the collar of his blue suit jacket.

Coates is friendly but fatigued and yawns several times during the course of our conversation. Some questions animate him and he digs deep with evident passion; others elicit a brief “I don’t know”. The interview doesn’t always flow. But even on an off-day, Coates, 42, is more compelling than almost any other public voice about the state we’re in. The New York Times described him as “the pre-eminent black public intellectual of his generation”. The novelist Toni Morrison compared him to James Baldwin. He emerged as the equivalent of poet laureate during Barack Obama’s presidency, chronicling the spirit of the age. If anything, the advent of Trump has pushed his stock higher. Coates admits it is “tremendously irritating” to be in constant demand by the media, as if he is sole spokesman for African American affairs.

But he does have much to say about Trump and the divided states of America. His book is a collection of eight essays he published during Obama’s eight years in office plus new material, including an epilogue entitled “The First White President”, in which he contends that Trump’s ability to tap the ancient well of racism was not incidental but fundamental to his election win. Many people have called Trump a racist or white supremacist, but Coates has the rare ability to express it in clear prose that combines historical scholarship with personal experience of being black in today’s America.

Halifu Osumare, director of African American and African Studies at the University of California, says: “Ta-Nehisi Coates has done his homework, including much self-reflection. He clearly knows his literary forerunners – [Richard] Wright, Baldwin and Morrison, yet he speaks as a 21st-century writer. He eloquently conflates the personal, political and the existential, while telling it like it is.”

Certainly, in contrast with other commentators, Coates has no qualms about stating that the White House is occupied by a white supremacist (a term he does not apply to other Republicans, such as George HW Bush or George W Bush). He lays out evidence that Trump, despite his upbringing in liberal New York, has a long history of racial discrimination. There was the 1973 federal lawsuit against him and his father for alleged bias against black people seeking to rent at Trump housing developments in New York. Trump took out ads in four daily newspapers calling for the reintroduction of the death penalty in 1989 after five African American and Latino teenagers were accused of assaulting and raping a white woman in Central Park. Even after the five were cleared by DNA evidence, he continued to insist: “They admitted they were guilty.”

He was once quoted as saying: “Black guys counting my money! I hate it. The only kind of people I want counting my money are short guys that wear yarmulkes every day.” More recently, Trump was a leading proponent of the “birther” movement, pushing the conspiracy theory that Obama was not born in the US and therefore an illegitimate president. While running for president, he said that a judge of Mexican heritage would be unfair to him in a court case because he was a “hater” and a “Mexican”. In one interview, Trump refused to condemn the Ku Klux Klan (he subsequently blamed a faulty earpiece).

In his epilogue, Coates writes: “To Trump, whiteness is neither notional nor symbolic, but the very core of his power. In this, Trump is not singular. But whereas his forebears carried whiteness like an ancestral talisman, Trump cracked the glowing amulet open, releasing its eldritch energies.”

Since then, there has been a white supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia, in which a civil rights protester was killed, prompting Trump’s comment that there were “very fine people on both sides”. Today, Coates adds the president’s visit to hurricane-hit Puerto Rico to Trump’s charge sheet: “Just yesterday, he goes to a part of the United States that’s been devastated by a natural disaster and throws toilet paper out to the crowd like they’re peasants or something. There are people in this country who will not be happy until Donald Trump is literally executing a lynching before they’ll use that term [white supremacist]. I’m not going to play around; let’s call things what they are.”

Last month Trump was at it again, condemning American football players who “take the knee” during the national anthem to make a statement against racial injustice. Throwing red meat to his base at a rally in Alabama, he called on team owners to fire them and to say: “Get that son of a bitch off the field right now.” The protest was started last year by Colin Kaepernick of San Francisco 49ers. Coates reflects: “Kaepernick’s protest has been very successful. I really appreciate the fact that he’s been giving away money to organisations; he pledged to give away a million dollars and he’s been doing it.”

But Trump used his familiar tactics to divert and distract, kicking up bitter divisions around the anthem, the military, how much sportsmen earn, the meaning of patriotism and, of course, himself. Amid the media storm, it was easy to forget what the original protest was about. “The police brutality element has been lost, but I think that is a danger that all protests face,” Coates says. “At some point, you’re always co-opted, successful protests especially. It happened in the civil rights movement. People forget that the 1963 march [on Washington] was for jobs: that somehow got lost, and it became this warm, fuzzy thing [now best known for Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech].”

The notion that all these issues would be resolved by Obama was always fanciful. Even so, Coates was swept up in the euphoria with millions of others in 2008 when the US elected its first black president. Had the nation – whose founding fathers were slave owners, and where today African Americans are incarcerated at more than five times the rate of whites – truly changed? Coates admits he took his eye off the ball. The racial backlash was coming.

“The symbolic power of Barack Obama’s presidency – that whiteness was no longer strong enough to prevent peons taking up residence in the castle – assaulted the most deeply rooted notions of white supremacy and instilled fear in its adherents and beneficiaries,” he writes. “And it was that fear that gave the symbols Donald Trump deployed – the symbols of racism – enough potency to make him president, and thus put him in position to injure the world.”

Trump did not come out of nowhere; he was the logical conclusion of years of racial dog whistles from the Republican party, which has sought to suppress the black vote through spurious claims of cracking down on fraud. Coates recounts: “Throughout his eight years in office, Barack Obama endured a campaign of illegitimacy waged either by pluralities or majorities of the Republican party. Donald Trump rooted his candidacy in that campaign. It’s fairly obvious.

“His first real foray out again as a political candidate was into birthism [Trump began questioning Obama’s birthplace in TV interviews in 2011], and a lot of people dismissed birthism as just something cranks do and we don’t have to deal with. That was a huge mistake: it underrated the long tradition of denying black people their citizenship and basic rights. That was what this was piggybacking off of, so it’s not a mistake that he started there and then became president at all.”

Coates does not make the claim that all 63 million people who voted for Trump are white supremacists; but they were, he points out, willing to hand the government over to one. It was an astonishingly reckless act. Coates’s book is a wake-up call to white America, a holding to account. “So this question, is everyone who voted for Trump a racist? This misses the point. Did everyone in Nazi Germany believe all the stereotypes about Jews? Of course not. It’s beside the point.

“When France deported its Jews, did everyone in France believe all this stuff? No, but that’s beside the point. Looking the other way has consequences and you might not be a racist or a white supremacist or a bigot, but if you voted for Trump, you looked the other way, you said it’s fine to have that in the White House, and a substantial number of Americans felt that way. That’s a statement.”

Coates also takes issue with the media’s obsession with the white working class as a bloc that turned its back on Democrats and defected to Trump. His book challenges politicians and journalists who make earnest defences of Trump-voting communities as “good people” not motivated by bigotry. Countless articles and books such as Hillbilly Elegy by JD Vance, a memoir about growing up in the white underclass, have been studied as key to understanding the despair of small towns left behind by globalisation. Are they missing the point? Is class secondary to race?

“It’s not like most working-class people voted for Donald Trump; they did not,” Coates says. “Most white working-class people voted for Donald Trump and the through line that you find is whiteness, not class and not gender. It’s not like he only got men; he got a majority of white women too. So if you look at categories of white people you find Trump being dominant among them, in part because of the appeal he made, but also in part because the Republican party has effectively become in this country the party of white people.

“What’s happening is the white working class is being used as a kind of signpost tool… There is some effort not just to absolve white working people, but to absolve whiteness because here’s the deal: ‘Oh, it’s fine that white working-class people and white poor people voted for Donald Trump because over the past 30 years they’ve had unmet expectations. And it’s also fine that rich white people voted for Donald Trump because of tax cuts.’ Come on: everybody gets off the hook.”

And yet many senators, including Bernie Sanders, whom Coates supported in the Democratic primary, Al Franken and Elizabeth Warren have argued that a generation of economic stagnation is real, fuelling anger that led some voters to throw a grenade at the Washington establishment. Middle- and working-class parents are frustrated that their children will not have the same opportunities they did. Trump’s defeated opponent Hillary Clinton writes in her new memoir: “After studying the French Revolution, De Tocqueville wrote that revolts tend to start not in places where conditions are worst, but in places where expectations are most unmet.”

To that, Coates responds: “Those expectations are built on being white. People say that as though it’s indivisible from the idea of race. You want to talk about unmet expectations? Black folks have been dealing with that since we got here, so the notion that, ‘My child isn’t going to have it as good as me, so that therefore gives me the right to vote for someone who conducts diplomacy with a rogue nuclear state via Twitter’ – that don’t work. Bottom line is, a significant number of people in this country have tolerance for bigotry. No one, I don’t think, can act like they didn’t know. You know I think [Trump’s racist] comments were well reported and America just decided it was OK.”

When white voters make bad decisions, Coates argues, excuses are made; when black voters do it, they get the blame. Coates recalls how the election of Marion Barry as mayor of the District of Columbia [later to be caught on camera smoking crack cocaine] prompted articles suggesting people in the district should lose the right to vote. “So there’s all this kind of rope that’s given, all these excuses allowed when you’re white in this country. But if black people acted that civically irresponsibly, that rope would not be awarded.

“Like you take the opioid crisis and all of the compassion that’s doled out in the rhetoric? Where was that during the crack epidemic in the 1980s? I remember it well. I was in a city where that was going on. Where was all that compassion? Black people aren’t worthy of that. That’s a story that can be created for white people because they’re white, but we don’t get that sort of compassion.”

Democrats are said to be torn between an emphasis on economic justice that aims to win back Trump voters and an emphasis on racial justice that will energise its liberal base. Asked about the future direction of the party, Coates is hesitant: “I don’t know. I shouldn’t answer that.” But after a pause, he weighs in: “Here’s one thing. I don’t think they can get away from talking about race because of the way things are aligned. You’ve got to get to a state like South Carolina or Georgia: these states have large numbers of black and brown voters.”

Coates grew up in Baltimore, where Francis Scott Key wrote The Star Spangled Banner and the first residential racial segregation law in any US city was enacted. More recently, it was famous for David Simon’s crime drama The Wire. “I had very little interaction with white people as a kid,” Coates recalls. “I think about what my world looked like as a child, a place that felt fearful, violent, then I’d put on the TV and I’d see that that was not the country at least as it advertised itself. That struck me and I always wanted to know why, what was the difference, why was my house not like Family Ties? That motivated a great deal of my work from the time I was young.”

His father, Paul Coates, was a Vietnam war veteran, Black Panther and voracious collector of books about the history of black struggle. Paul Coates had seven children by four women and was an intellectually inspiring father who also administered beatings. Coates has described him with affection as “a practising fascist, mandating books and banning religion”. The religion ban worked – Coates is an atheist – and so did the books, eventually. In February 2007, Coates, then 31, had just lost his third job in seven years and was trying to stay off welfare. He writes: “I’d felt like a failure all my life – stumbling out of middle school, kicked out of high school, dropping out of college... ‘College dropout’ means something different when you’re black. College is often thought of as the line between the power to secure yourself and your family, and the power of someone else securing you in a prison or grave.”

Married with a young child, he possessed intellectual curiosity and the gift of a wordsmith. He produced an essay about Bill Cosby that caught attention and led to a relationship with the Atlantic magazine, where he is now a national correspondent. His ascent coincided with Obama’s and a new world of possibilities. “It was as if I had spent my years jiggling a key into the wrong lock. The lock was changed. The doors swung open, and we did not know how to act.”

Coates made a splash with a 2014 article for the Atlantic arguing that the US should pay African Americans reparations for slavery. Then, a year later, came Between the World and Me, a rumination on black life and white supremacy, addressed to his teenage son in a letter form that evoked Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. It argued that the “destruction of black bodies” is not simply a recurring theme of American history but its central premise. It won the National Book Award in nonfiction, sold 1.5m copies around the world and has been translated into 19 languages.

As his star rose, Coates was invited to the White House. He got to spend time with Obama, whose fundamental optimism in America had convinced him that Trump could not win. He says: “He was tremendously intelligent, one of the smartest people I’d ever talked to, and he was smart in many ways. I met him a few times: one was with a bunch of journalists and he had the ability to address each journalist in their specific area in a very learned way. I thought he was brilliant.”

He reckons “in the main” Obama lived up to the impossibly high expectations of his presidency. “He had an incredible tightrope to walk and it’s difficult, man. You’re the first black president and you’ve got to represent a community, then speak to a larger country at the same time. If he was more radical he wouldn’t have been president. That’s what I’ve come around to: who he was was what the country wanted at that time. He can’t be me; not that he should want to be. But it’s a very different calling.”

Indeed, Coates sees himself as a writer – including of a comic-book series starring superhero the Black Panther – rather than an activist or potential politician. “That’s what I’m supposed to be doing because it’s what calls to me and it’s what I’m good at, what I excel at. I don’t really excel at this other stuff. I’m not a person who’s going to say whatever I have to say to get a coalition together, which is what you have to do in politics. I’m a writer.”

Towards the end of the interview, the questions become longer and Coates’s answers become shorter. He is probably relieved when it’s over, though he is too polite to say so.

Later he is busy tweeting links to articles about gun violence, nuclear war and earthquakes, jokingly chiding their authors for offering no hope. It is a charge with which he is all too familiar. “Our story is a tragedy,” he writes in We Were Eight Years in Power. “I know it sounds odd, but that belief does not depress me. It focuses me. After all, I am an atheist and thus do not believe anything, even a strongly held belief, is destiny... The worst really is possible. My aim is never to be caught, as the rappers say, acting like it can’t happen. And my ambition is to write both in defiance of tragedy and in blindness of its possibility, to keep screaming into the waves – just as my ancestors did.”

• We Were Eight Years in Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates is published by Hamish Hamilton (£16.99). To order a copy for £14.44 go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New York Times, more sinned against than sinning. Or not.

The New York Times has caught a lot of grief for its “1619 Project”, which claims to explain all of American history in terms of slavery. And much of it is justified. Damon Linker, writing in The Week, gives a reasonable overview: “The New York Times surrenders to the left on race”, Damon offers praise where praise is due:

Now, there is a lot to admire in the paper's presentation of the 1619 Project — searing photographs, illuminating quotations from archival material, samples of poetry and fiction giving powerful voice to the black experience, and gripping journalistic summaries of scholarly histories. Much of it is wrenching, moving, and infuriating. The country's treatment of the slaves and their descendants through the century following emancipation and, in some respects, on down to the present was and is appalling — and the story of how it happened, and keeps happening, is extremely important for understanding the United States. Bringing this story to a wide audience is a worthwhile public service.

But there is a whopping downside as well:

Throughout the issue of the NYTM, headlines make, with just slight variations, the same rhetorical move over and over again: "Here is something unpleasant, unjust, or even downright evil about life in the present-day United States. Bet you didn't realize that slavery is ultimately to blame." Lack of universal access to health care? High rates of sugar consumption? Callous treatment of incarcerated prisoners? White recording artists "stealing" black music? Harsh labor practices? That's right — all of it, and far more, follows from slavery.

In fact, I found the packaging so off-putting—so portentous, condescending, and cheesy—“Everything you learned about slavery in school is wrong!”—as if we were all a nation of Homer Simpsons stretched out in our lazee-boys before our beloved wide screens shoveling honey-glazed pork rinds into our gaping Caucasian maws with both hands for fourteen hours a day—all of us who don’t work for the New York Times, that is—that at first I skipped the whole goddamn thing, only to go back and discover the same mixed bag that Damon described.

Many of the articles were good, but, shockingly—so shocking, in fact, that Timesfolk may not even believe me—I knew a lot of it already. When I was a boy, which was waaayyy back in the fifties, I read Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery, a book about slavery written by someone who’d actually been a slave, inspired to do so after first reading a “Classic Comic Book” version of Washington’s story. Later, in the tenth grade, I stumbled across Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, just sitting there on the library shelf, where any dumb ass could pick it up. (I thought it might be like H. G. Wells. As it turned out, it was even better!)

And what about James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time”? How about The Autobiography of Malcolm X? Or Soul on Ice? These were all works that received immense publicity decades ago—before, I suspect, many Timesfolk were even born. And what about “today”? I remember several decades ago a black woman telling me she thought interracial couples were crazy to expose themselves to the sort of hatred they received from both blacks and whites. Today, interracial marriage is (almost) passé. Recently, the Times own Thomas Edsall published a long piece examining the impressive gains in both education and income levels for some (but not all) blacks. But the 1619 Project isn’t interested in “good news.” Over a century ago, House Speaker Thomas Reed congratulated Theodore Roosevelt on this “original discovery of the Ten Commandments.” One could offer similar praise to the New York Times.

I was intrigued in particular by the “Everything you learned about slavery in school is wrong!” pitch. Well, if so, New York Times, tell me, what are our kids learning, not 60 years ago, when I went to school, but today? Nikita Stewart fills us in: ‘We are committing educational malpractice’: Why slavery is mistaught — and worse — in American schools.

Nikita begins her piece by quoting a text book written in 1863 (not a misprint) in the South. Guess what? It’s totally racist! Totally! Who could have imagined? Also guess what? Things haven’t changed that much! How do we know? Nikita tells us so.

Stewart follows the pattern used in many of the pieces, taking an egregious example from the past and then “explaining” that things haven’t changed much. For the meat of her article, she relies almost entirely on a study by the Southern Poverty Law Center, an organization that has done good work in the past but now is largely a solution (and a very well funded one, at that) in search of a problem. Of course the SPLC is going to find that America’s school books don’t adequately teach the role of slavery in American history. How could they not?

Part of the problem, Stewart says, is this: “Unlike math and reading, states are not required to meet academic content standards for teaching social studies and United States history.” She’s presumably referring to the “Common Core” standards, but states are not “required” to meet them, and in fact the whole “standards” movement, pushed by the Obama administration back in the day, has since fallen into considerable confusion, in conjunction with the entire Trumpian revolt against “experts”.

Speaking of her own schooling, Stewart tells us, “I was lucky; my Advanced Placement United States history teacher regularly engaged my nearly all-white class in debate, and there was a clear focus on learning about slavery beyond [Harriet] Tubman, Phillis Wheatley and Frederick Douglass, the people I saw hanging on the bulletin board during Black History Month.” How does she know she was “lucky”? Doesn’t she “mean” “My own experience was contrary to my thesis and therefore it must be exceptional”?

Instead of selectively quoting a handful of “experts” she chose to tell her what she wanted to hear, why didn’t Stewart do some actual leg work, or chair work, by reviewing the textbooks used in, say, California, Texas, New York, and Florida, the four largest states, containing about one third of the entire U.S. population, and including two states from the Confederacy? Isn’t that what the “1619 Project” is supposed to be about?

Because we most definitely need to examine the way the history of slavery and the Civil War is taught and understood in today’s USA. Nothing is more obvious than that leading figures, or “would be” figures, in the Trump Administration, starting most obviously with Donald Trump himself, and including former chief of staff/four-star Marine General John Kelly and dumped (dumped and disgraced) putative Federal Reserve Board appointee Stephen Moore, all cling to the absurd and disgusting notion that the North was the “bad guy” in the Civil War. As Moore “explained”, “The Civil War was about the South having its own rights”—you know, the right to enslave and oppress millions of human beings.

But it isn’t only the Trumpians who still maintain a soft spot—and a grossly meretricious soft spot it is—for the “Lost Cause”. Poor David French, who gets it from both the left (for being a conservative and, worse, an evangelical Christian) and the right (for being insufficiently bad ass), is going to get a little for me. There’s good Dave, as in this excellent article in which he both describes his laudable efforts to prevent the muzzling of “wicked” Christian groups on campus and denounces proposals on the right to restrict the First Amendment rights of those on the left (largely “the media” and “Big Tech”):

Never in my life have I seen such victimhood on the right. Never in my life have I seen conservatives more eager to rationalize passivity and seek the aid of politicians to make their lives easier. They look to politicians — even incompetent, depraved politicians — and cry out, “Protect us!”

Admirable words. But here are some not so admirable, in an unfortunate piece with the unfortunate title “Don’t Tear Down the Confederate Battle Flag”.1 After launching into a scarcely objective account of the South’s motivation for succession—scarcely better than Moore’s—French falls into total small-boy, flag-waving, saber-waving mode:

Those men [the southern armies] fought against a larger, better-supplied force, yet — under some of history’s more brilliant military commanders — were arguably a few better-timed attacks away from prevailing in America’s deadliest conflict.

So yay Team Dixie, right? If only “we” had won. Then slavery forever! Is that what French dreams of? That southerners could continue to exercise their “right” to whip millions of black men, rape millions of black women, and sell their children for profit? If only those few attacks had been better timed! Damn it!

Couldn’t the Germans say the same thing about World War II? If only we had won. Then the Master Race forever!

These “brave men” at whose shrine French worships, wantonly murdered all black Union troops they captured, in utter violation of the most basic “laws” of war. When Robert E. Lee (French’s “gallant” hero, of course) marched into Maryland and Pennsylvania, he captured black American citizens and impressed them into slavery, sent them south to labor in defense of their own oppression. Mr. French fancies himself a Christian. But sometimes, it seems, Christians forget.

Afterwords

It’s “interesting” that both Chief Justice of the United States William Rehnquist and Supreme Court Justice Antonine Scalia felt somehow compelled to parade their opposition to Brown v. Board of Education, Scalia “explaining” that liking the sort of judicial thinking that produced Brown because it produced Brown was like liking Hitler because he developed the Volkswagen—which by the way is entirely untrue,2 but whatever, Brown equals Hitler, got it?

French says “battle flag” because as a true southerner he knows that the familiar “stars and bars” was not the flag of the Confederacy. ↩︎

The Volkswagen was largely designed by an Austro-Hungarian designer named Béla Barényi in the mid-twenties and then “modified”, sans credit to Barényi, by Ferdinand Porsche a few years later. Hitler planned to put the car into production as a "people's car" but, unsurprisingly, the cars that were built were all for military use. After the war, an enterprising British major thought the bombed out VW factory could be repaired and used to create jobs for workers in a shattered Germany. ↩︎

0 notes

Text

Heather Hart, Readings, Videos, and 20x20.

Heather Hart, an African American artist born May 3, 1975 dove right into her lecture by sharing pictures of her artworks. She was born and raised in Seattle. Hart is highly educated as could be seen from her achieving a BFA from Cornish College of Arts, attending the Center for African American Studies at Princeton University, and obtaining a MFA from Rutgers University.

Heather Hart reminds me of Taiye Selasi, the woman who was on the TED talk video: “Don’t ask me where I am from, ask me where I am local”. Her quote in the talk really resonated with me “How can a human being come from a concept? It's a question that had been bothering me” because I too am not just from one place. Born and raised in Los Angeles, I ended moving to Hong Kong where I went to a British International School there. So I have been a part of many places, been accustomed to many different cultures, traditions, language and people. I’m just like Heather Hart and Taiye Selasi, no matter where we are “from”, we are not bounded by it, we are more than it. Taiye Selasi went on more to explaining how it doesn’t seem right to say that she’s from the United States when she’s only had a relationship with Brookline, New York City and Lawrenceville, and not every single state and city in the US. I can agree completely with her. It does seem ridiculous now to say you’re from a place where you haven’t even the least lived or explored or been familiar to most of things accustomed to the United States. Whenever I address where I seem to come from, people would just automatically answer the question for me with their opinion: It doesn’t matter where you were born, it doesn’t matter where you have lived or stayed the longer, you’re family is Chinese so you’re automatically Chinese. I find this rude, because it seems people base their labels off appearances. I may look Chinese and know how to speak the language, but I do not know most of the things to being a Chinese. I don’t know how to read or write Chinese, nor do I know the area. If I was placed in China right now, I would be completely lost. I don’t follow most of their traditional cultures as well, the only holiday I celebrate is Chinese New Year with my family. How is it safe to say that I am truly only Chinese when I am more than just one label? This is based on Selasi’s three step test called the Three R’s: Rituals, Relationships, and Restrictions. The Rituals I share would be like I said holidays and festivities that I care about such as Chinese New Year, which pronounces my Chinese, and western holidays like Christmas, Thanksgiving and Halloween which signifies my western side. My relationships are with my parents who are Chinese, my American childhood friends, my high school British and Hong Kong friends and my current international and American college friends. Like Selasi mentioned the 3 R’s have proved that I am not just a part of one label, I am everything that I have been accustomed to.

Many factors played an influence on Hart’s artistic practice and career. A big factor would be her family. Her dad was a carpenter and starting from a young age, he taught her carpentry. This allowed her to have taken on an interest in sculpture influenced by his father. She also researched her family tree which brought her to to discover this essay written for her great great great great grandfather (4 generations before her) by a student where he mentions the tribes from Africa that he has found and she discovers many other histories about it. Her favorite movies and movie actors who were negro played a big part in influencing her artworks e.g. her sculpture piece of “The New Numinous Negro” was based upon it.

Her artistic practice consists of many traditional mediums such as watercolor, collage, printmaking, and drawings. But what makes her unique is that she likes to combine these mediums together than use them individually. She goes back and forth with these mediums, she is always constantly exploring with them. She describes herself as a research based person instead of being into experimenting with materials and thinking about formal reasons in her art.

One of her pieces that resonated with the most is The Black Lunch Table. Heather Hart is the co founder of this collaborative masterpiece. The aim of this piece is to take literal or metaphorical lunch tables filled by the artistic community or the larger community of neighbors and visitors and transform them into a discursive site, the perfect space to be able to discuss critical issues to clarify and support shared concerns. In my opinion, I think this is a genius masterpiece because it is such a clever way to have people who identify as an African American to be able to join in on conversations and feel as if they’re a community. Last week’s readings especially the video: “The Problem with Wokeness” and the New York Times article: “I’m a Black Feminist. I think Call-Out Culture is Toxic.” has a connection to this piece. Both the video and the article strives for a community where we finally understand each other instead of turning our backs from each other and continue to be separated by our differences and labels. The Lunch allows us ignore them and be able to come together by our similarities and finally be able to look past our labels.

Her art practice relates to the core issues addressed in the talk, because it is the core issues she has that influenced her art practice. Her work explores changed symbols and traditions, the nostalgic future. She wants her works to be able to engage with the audience by activating and programing the public. A major issue she has is depicting the personal reclamation.

Throughout the presentation, I felt quite lost. Hart would not have a clear method of explaining her artworks, its process and meaning. She would constantly jump from one thing to the next without elaborating into it properly. Sometimes during the lecture she would be explaining something and she would even lose herself during the process. Where she would end whatever she was trying to say by repeating “I don’t know” because she had confused herself as well. This has me questioning her intentions in her artworks. She doesn’t seem to know what she is really doing sometimes. For an artist to be able to create their artworks based on a theme, they would have to know the theme well because it is their motivator.

In terms of the bigger picture, although I had a criticism about Hart, but I do admire her artworks and the meanings behind it, at least the ones she has managed to explain in deeper detail. She bases her artworks on her identity as a black woman. She tries to

Several readings and videos that has interested me the most for this week is Taiye Selasi TED TALK “Don’t ask me where I am from, ask me where I am local” (which I have already mentioned earlier on), Setting The Historical Stage passage, and the BBC Ideas Video: “Gender identity: 'What quantum physics taught me about my queer identity’”.

“The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.”- James Baldwin. This is a quote taken from Setting The Historical Stage passage which made me think of how much of an affect our histories have on our present and potentially our futures. In the passage, when the Spanish conquistador Balboa discovered Panama, he also discovered very open sexual and queer behaviors from the Indigenous people of Quaraca. He was disgusted by these actions that he ordered brutal punishments then deaths to them. This past has reflected on our present and future in many ways. Although many people are striving for the acceptance of the LGBTQ community, there are also many people who continue to share the disgust and hatred towards it like Balboa. Furthermore, many places like the United States still conduct punishment and policing for these actions. The author of this passage even quotes the US as a “the current criminal legal system.” In my opinion, the people who still do not accept specific groups of people like the LGBTQ community is mostly because they still share these old traditional views that were brought upon them because of our history. If people with enormous power like Balboa was accepting then, we wouldn’t have this problem now.

This also reminds me of the BBC Ideas Video: “Gender identity: 'What quantum physics taught me about my queer identity’. Amrou Al-Kadhi the narrator of the video gave an interesting perspective on how we should view gender identity, which is quantum physics. He explains: “Quantum physics reveals that there is no fixed reality and it’s full of beautiful contradictions” Al-Kadhi explains this by using a sub-atomic particle which can be in many places at the same time and multiple versions of the same event can be able to occur all at the same time. This reminds me of Heather Hart, Taiye Selasi and my shared issue. We are like these sub-atomic particles which has acted as a metaphor for where we belong. We don’t belong in one label, we can be more than one at the same time, just like the particles.

A 20x20 presentation that has interested me the most, was the one on Cian Dayrit. Dayrit, an artist born in Manila, Philippines in 1989 who is currently based in Brazil, is an intermedia artist working with sculpture, painting, and installation and considers himself as a researcher. His working themes are about origins, history, heritage, nationalism, nation-building, and critical problems in the Philippines. Just like Heather Hart, he creates his artworks also based on his identity. He also looks into a character and their political life and material legacy, which is the things in history that passed on. He also takes interest in how one navigates his or her life through suppose guilt and entitlement but also reluctance of control. During his time in London, he hunted for colonial images that represent power, he used these images as a tool to critique a rather privileged perspective that challenges the traditional concept of mapping since he believes it is a very politically manipulated creation. His love for mapping has grown that he even gave out workshops on mapping. His workshops with the underrepresented population guides them to create individual maps to establish a self identity that they have control over rather than the political powers. A word he believes revolves around mapping a lot is hegemony: leadership by one country over another. One of his artworks that I am quite fond of is the Monuments of Great Divide. The work is done in collaboration with the artist Felman Bagalso. It is a multimedia work of wood sculpture with acrylic and digital print on paper. He creates these wood sculptures of walls that feature chicken wires and spikes that show the dangers of crawling over. How I have interpreted this piece is that these walls suggest the different levels of restrictions at different borders and the difficulty of passing through them. The drawings feature the boundary divisions that are artificial which were come up by political powers. I believe it is criticizing how the way the territory are divided may not be fair or even artificial.

0 notes