#Jakob von Uexküll

Text

«Sul finire del Sedicesimo secolo la volta celeste si alzava, come la vediamo noi ancora oggi, non di venti metri come nel planetario, ma circa a non più di trenta chilometri sopra di noi, come un’inflessibile costruzione. Sopra questa fortezza celesta troneggiava il malefico Dio, la cui vista penetrava in tutti gli errori degli uomini, che puniva senza pietà con la guerra, la peste, gli incendi. La volta celeste, che sosteneva i palazzi e i giardini di Dio, cingeva come un guscio d’uovo la Terra liberamente sospesa nel vuoto.

«A questo punto entrò in scena Giordano Bruno e ruppe il guscio dell’uovo cosmico aprendo lo sguardo meravigliato e felice dell’umanità sull’infinità dello spazio. Le stelle fisse non erano più i bottoni dorati inchiodati all’immobile parete celeste, ma divennero barche dorate che si muovevano liberamente nell’etere a grande distanza le une dalle altre. Tutta la magnificenza dei palazzi divini si era volatilizzata. Se fossi un grande artista come lei», disse lo zoologo volgendosi ora al pittore, «progetterei un affresco imponente che, come contraltare del Giudizio Universale di Michelangelo, raffiguri Giordano Bruno sul rogo. Ma le fiamme, che devono bruciarlo, salgono verso il cielo e incendiano la volta celeste come fosse una misera quinta teatrale. Si vedrebbero quindi la città di Dio con i suoi opulenti palazzi crollare, dissolvendosi nel fumo e nella cenere, e insieme ad essi cadrebbero vittime dell’eterna distruzione angeli e santi. In lontananza, le stelle dell’Orsa Maggiore, come sfere luminose, apparirebbero in segno di vittoria.»

Jakob von Uexküll, L'immortale spirito nella natura, traduzione dal tedesco di Nicola Zippel, Castelvecchi (collana I Timoni), 2014. [Libro elettronico]

[Edizione originale: Der unsterbliche Geist in der Natur, Christian Wegner Verlag, Hamburg; testo pubblicato in tre parti fra il 1938 ed il 1947]

#libri#letture#leggere#saggi#saggistica#Giordano Bruno#Jakob von Uexküll#scienza#scienze#conoscienza#biologia#libertà di pensiero#Nicola Zippel#astronomia#teologia#atei#libero pensiero#ateismo#etologia#ecologia#agnosticismo#libertà di parola#agnostici#umwelt#ambiente#percezione#filosofi#filosofia#fenomenologia#semiotica

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

May you have a perfect [blank]. Not omnipotent, but rather founded on the correct use of all available means.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Animals in the Mirror of Ethology" by Jakob von Uexküll

“Animals in the Mirror of Ethology” by Jakob von Uexküll

“Animals in the Mirror of Ethology” by Jakob von Uexküll is a renowned and seminal book in the field of ethology. Originally published in 1934, this book remains a classic in scientific literature to this day.

In this work, Jakob von Uexküll presents a new approach for understanding animal behavior, based on the idea that each species has its own perceived world, which he calls “Umwelt”.…

View On WordPress

#animal behavior#animal cognition#animal interaction#behavioral science#cornerstone work#environment#ethology#Jakob von Uexküll#perception#scientific literature#Umwelt

0 notes

Text

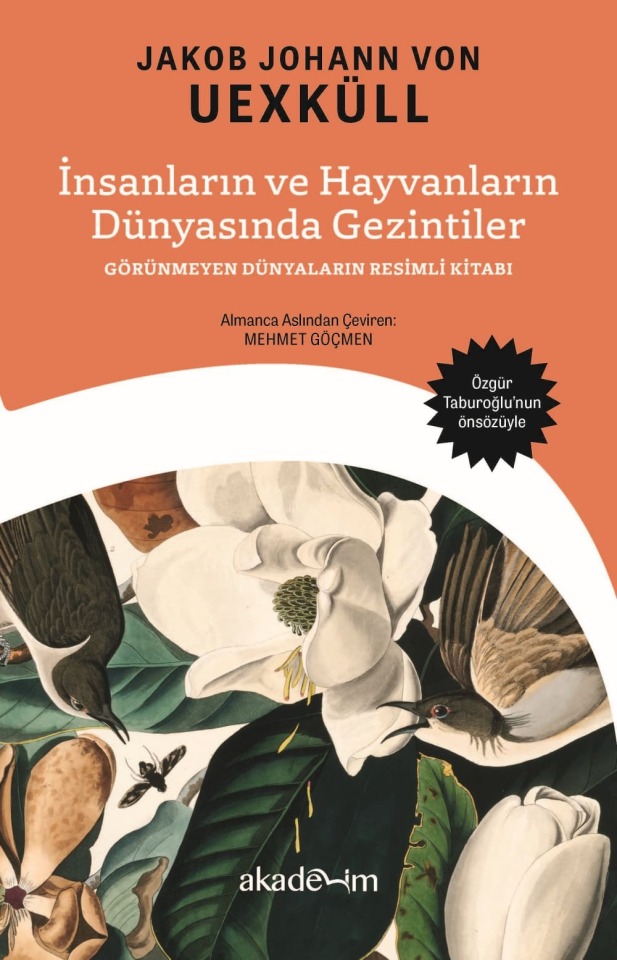

Jakob Johann von Uexküll – İnsanların ve Hayvanların Dünyasında Gezintiler (2023)

Biyosemiyotiğin öncüsü Jakob Johann von Uexküll, ekolojik düşüncenin bu kurucu metninde her canlının yalnızca kendisine, onun deyimiyle, Umwelt’ine ait bir mekânı ve buna karşılık gelen bir zamanı olduğu fikrini dile getiriyor.

Bunun sonucunda Agamben’in ifadesiyle, insanmerkezci bakış açısının terk edilmesi ve doğa imgesinin insan ölçütünden arındırılmasının önü açılmış; Deleuze ve Guattari’nin…

View On WordPress

#2023#Akademim Yayıncılık#Görünmeyen Dünyaların Resimli Kitabı#Georg Kriszat#Jakob Johann von Uexküll#Mehmet Göçmen#İnsanların ve Hayvanların Dünyasında Gezintiler

0 notes

Note

Do you believe it’s helpful to compare non-human animal intelligence to human intelligence?

I think that it can be helpful as a way of trying to understand the cognitive capacities of non-human animals, so long as we recognise the limits of any such comparison. Intelligence is an inherently human concept; we base intelligence on what we can do. That isn’t necessarily bad, we need a reference point after all, but we’ve made the mistake of judging our own kind of intelligence as the only kind there is.

We are really just scratching the surface when it comes to animal intelligence and perception. We can measure how they perform tasks that we invented to measure intelligence as we define it, but we can never really know what it is ‘like’ to be a dog, or a bat, or a fish. Many behaviours we think of as ‘intelligent’ have no benefit for many animals, so how ‘intelligent’ would it be for them to develop it?

Likewise, there are realms of perception that we just can’t touch. We consistently underestimate how radically different every creature’s inner and outer world is to our own. It is what the biologist Jakob von Uexküll calls an animal’s ‘Umwelt,’ their own unique sensory world. We can’t even do this with animals we know well, never mind with animals radically different to us.

Just look at dogs. Most of the intelligence experiments involve getting dogs to perform a specific task, and most of it is based on sighted intelligence, because that is at the centre of our Umwelt. But the primary sensory modality of a dog is not sight, it is smell. How often do we think a dog isn’t performing a set task because they can’t remember that the first button produces food and the second button doesn’t, when they’re actually responding to perceptual clues we can’t even perceive?

There is just so much about animal behaviour that we don’t understand. Why do cephalopods like octopus, squid, and cuttlefish put on elaborate colour shows when alone, when their eyes appear to only see in grayscale? What are they perceiving and what are they responding to? How do we measure animal intelligence for an animal that has sonar? Or an animal that can see ultraviolet light? Or can sense minor vibrations from miles away?

Intelligence is just such a distinctly human concept that it is hard to apply to minds that are so different to our own. We sort of assume intelligence is a scale with us at the top, and we measure how close other animals are to us on that same scale. But non-humans need a different scale entirely. That is the biggest problem with the study of animal intelligence in general, we too often assume we’re studying lesser minds, rather than just other minds.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Umwelt: What Matters Most in the World

(Originally posted at my blog at https://rebeccalexa.com/umwelt-what-matters-most-in-the-world/)

I will be the first to admit that a lot of philosophy tends to bend my brain in ways that I’m really not prepared for. I’m a very earthy creature, and I am more comfortable in physical, solid spaces than in abstract conceptualizations. Even the modalities of psychology I gravitated toward in grad school tended to be based in our interactions with physical nature, and measurable effects thereof. But it was a casual discussion on philosophy with regards to the awareness of animals that introduced me to the concept of umwelt.

Originally coined by biologist Jakob Johann Freiherr von Uexküll, umwelt describes the unique way in which a given animal experiences the world around it. Uexküll looked at how various beings take in information through their senses; the way that a blind, deaf worm engages with their environment through taste and touch is very different from how we with our hearing and color vision connect with our world. Even when I am walking with my dog out in the woods, her interpretation of what’s going on around us is going to be much more heavily influenced by hearing, and especially smell, than my sight-heavy approach. (And when we engage with each other, our respective umwelten create a semiosphere!)

So umwelt is essentially the sum total of all the ways in which an animal takes in that sensory information and attaches meaning to each fragment thereof. It’s how they tell the story of the world around them, and understand their place in it. And they rank the signs according to importance; umwelt is more strongly formed by things that are of particular interest to the animal.

That means that umwelt, rather than being constant throughout life, is always shifting according to new sensory input, or changes in how the senses work; as my dog gets older, her hearing and vision may not be as good as they were, but if her nose stays sharp then smells may become an even more important part of how she navigates her world.

Or look at a Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana), which is born as a blind, deaf little hairless being with two front legs that they use to crawl to the mother’s abdominal pouch. At that time their umwelt centers on seeking and retaining the warmth of their mother’s pouch, and the sensation of the constant flow of warm, nourishing milk. After about ten weeks they leave the pouch as a miniature furry little possum and travel on their mother’s back while learning to walk; their umwelt has expanded quite a bit to include the sight and smell of their mother, the visual and scent cues that tell them how close they are to known food sources, and visual, sound, and audio information warning of various dangers. At around five months, the opossum becomes independent, and their mother fades from their umwelt while being replaced by an even larger network of food, danger, and perhaps even potential mates. Over a lifetime, as the opossum’s senses develop (and, with age, decline) and their priorities shift, so does their umwelt evolve with them.

This then led me into a bit of a rabbit hole with biosemiotics. Semiotics is the study of symbols and the communication of meaning, to include communication with the self. Biosemiotics, then, is how non-human beings assign meaning to various things in their lives, and interpret the world they live in. Zoosemiotics specifically refers to the semiotics of animals, like the examples I’ve given so far, while endosemiotics (aka phytosemiotics or vegetative semiotics) is semiotics at a cellular or even molecular level.

One example of endosemiotics can be found in our immune systems. A B lymphocyte can recognize an invader such as a virus or bacteria, and it sends out a signal (an antigen) to T lymphocytes that then attack the invader. The B lymphocyte’s umwelt consists of information received through surface receptors that can detect certain proteins and other molecules, and the response it’s programmed to have as a result of detecting an invader. The T lymphocyte’s umwelt, on the other hand, centers on the B lymphocyte’s antigen signal, as well as the invader itself.

Biosemiotics is important because it moves meaning-making beyond humans, demonstrating that we are not the only beings who assign more importance to one part of our world than another. It promotes the idea that human language is not necessary for an organism to be able to find meaning in their environment. I’m cautious about anthropomorphization–assigning human traits to non-human beings–but biosemiotics allows each being to be its own unique self, rather than being gauged by human standards.

It’s all too easy for me to get overwhelmed by just how technical some of the discussion over biosemiotics can get (especially when delving into the “semotics” part of it!) But my takeaway is that it’s nice to have a term–umwelt–that encapsulates the unique experience that every animal, plant, fungus, slime mold, and other being has, no matter how large or small its world may be.

I can envision millions upon millions of overlapping umwelten in every ecosystem, becoming semiospheres whenever two or more of those umwelten nudge, slide, or crash into each other. I’m already delighted by knowing that I myself contain several ecosystems, with microbiomes in my organs and on my skin and more. But I can now also consider the umwelten and semiospheres of the lymphocytes in my immune system, along with all the other cells that are carrying on their existences within my various tissues, fluids, and so forth.

Of course, this gets into discussions of whether umwelt requires some level of consciousness, the nature of consciousness, sentience vs. sapience, etc., etc., all of which are the sort of headache-inducing philosophical discussions that I try to avoid at this stage of my life. So I can understand that this whole umwelt-biosemiotics thing is still being hammered out and explored and critiqued, but also use it to augment my own personal model of my world, internal and external (my innenwelt!) And for now, umwelt is a perfectly good shorthand for “the unique way in which an organism experiences its environment.”

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#umwelt#nature#vocabulary#vocab#natural history#natural philosophy#philosophy#psychology#ecopsychology#consciousness#semiotics#biosemiotics#symbols#wildlife#ecology#biology#science#scicomm#science communication#long post

77 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you read any of Jakob von Uexküll’s writings on invertebrate consciousness? One of the reasons I’m not a panpsychist is that I think a central nervous system (or something functionally analogous) is a condition for even rudimentary consciousness. Uexküll has what I thought were pretty plausible analyses of animal consciousness—famously that of ticks, and of bees—based on their sensory and operational capacities. The general idea is that, to have consciousness, an organism must have behaviour that it enacts in a discriminatory way based on sensory input from the environment. But I don’t think his approach would support an analysis of any phenomenon without a CNS.

Hi hi hi. This is such a good ask. Thank you <3.

I haven’t read Uexküll but I would be interested to. Most of my current read on invertebrate consciousness comes from Godfrey-Smith, Carls-Diamante and Woerkum. (And wrt consciousness more generally the usual suspects of Nagel, Chalmers and Dennett etc.).

I think it’s an unambiguously difficult question. I think there’s a lot of confabulation around the meanings of general terms in this field in particular. I’m wary of conflating ‘having a point of view’ with ‘experiencing consciousness’. And to make that point clearer it's quasi-autological. But it's easy to miss the redundancy (what i'm claiming is that implies an inexplicit confabulation) there right? Compare: 'experiencing' and 'experiencing consciousness'.

Octopuses are my favourite go-to invertebrate to investigate vis-a-vis consciousness, though your caveat of “or something functionally analogous” to a CNS makes it tricky here. Octopuses don’t have a CNS, their nervous system is distributed with 1/3rd of their neurons in their heads and 2/3rds in their arms. Their central brain doesn’t receive proprioceptive information about the arms (the arms process their own sensorimotor information) but the central brain *can* seemingly determine the arms' general location. (And a severed arm will try to put food where the mouth *was* at time of severing (i.e. there is communication across this distributed network).

So what’s it like to be an octopus (if it is like anything)? Is it like being an organism with 8 arm-tulpas living in your head? Or is it more atomic and each arm is its own creature, sharing control over its internal environment according to the whims of 8 other creatures (7 arms, 1 head)? Well, nobody knows, but I don’t think either of these are very likely, I'm currently of the position that agnosticism is the right approach here and I'd like to hear more from the disunified conceptions of conscious experience crowd before coming to any firm judgement. I *do* think octopuses are having some kind of phenomenal experience and I think that intuition is in no small part due to their integrated behaviours in response to their environments. So I guess to that extent my intuition is already slightly aligned with Uexküll here, though I'd be cautious about formalising it into necessary and sufficient conditions for conscious experience. I don't think those kinds of generalisations are warranted.

The nature of a particular conscious experience and the structure of the brain definitely correlate. That much is pretty much inarguable. I would go further and say that a discriminatory sensorimotor relationship with external objects is fundamental to the types of consciousness *of which we're most familiar*. But I'm stepping short of claiming that they're necessary and I also don't yet buy that even those unfamiliar types of consciousnesses found in distributed nervous systems don't do this.

I'm cautious of claims about consciousness that are about static states. I think all the expereinces of consciousness that I, at least, have access to are dymanic, ongoing, shifting spectral phenomena.

#so in conclusion... no i haven't read him. but i would like to#sorry - this kind of got away from me and i went on a ramble#and not a particularly focused one... didn't stay on the topic of panpyschism at alll >.<#anyway I had fun. thanks for the ask <3#i will continue to think it out and ponder... ruminate perhaps... like some kind of human... or crow...#(octopodes do not particularly display ruminative intelligence but crows do! that's like humans. good ape!)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

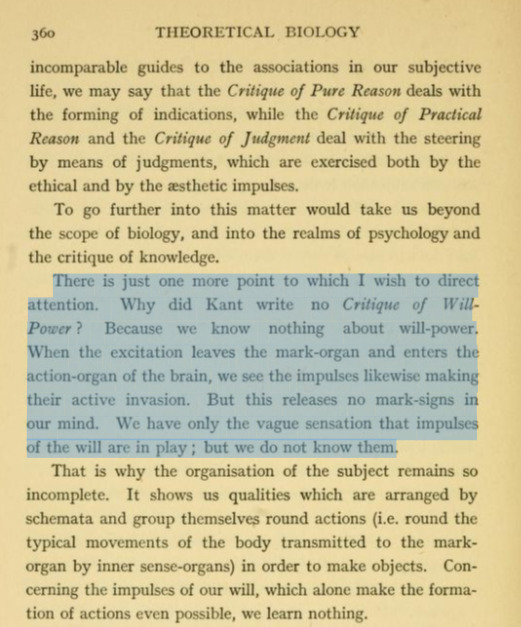

Theoretical biology, 1926

by Uexküll, Jakob von, 1864-1944; Mackinnon, Doris L. (Doris Livingston)

0 notes

Text

.

KOKOROBAE

.

2015

Mots et pierres contiennent un langage qui suit une syntaxe de failles et de ruptures. La biotite se détache en lambeaux de feuillets de Biot. Les oligloclases demandent un peu de casse. Et le zircon, un silicate de jargon. Autant de minerai pour un centon sédimentaire : ce langage déstabilisant de la fragmentation n’offre pas de solution globale évidente. Les certitudes du discours didactique sont rabattues sur l’érosion du principe poétique.

KOKOROBAE

(extension du coeur)

— Beatriz, Beatriz Elena, Beatriz Elena Viterbo, Beatriz chérie, Beatriz à jamais perdue.

Les choses concernent notre existence. C’est ce concernement qui est source d’émotion. Il y a quelque part une charnière, un seuil ou une phase, une limite en deçà ou au delà. Tout — le soleil, les vagues — a une volonté propre rudimentaire. Bientôt les choses de la nature deviennent un Tu auquel je peux m’adresser. Un retour du refoulé prend place, et le paysage se remplit de ses dieux à nouveaux. Sachez. Toute chose est à son lieu, et elle le distribue autour d’elle. À main droite du poteau routinier (En venant, bien sûr, du Nord Nord-Ouest). Un squelette s’ennuie. — Couleur ? Blanc céleste — qui donne

à l’enclos aux brebis allure d’ossuaire.

Il existe une distinction fondamentale entre d’une part, l’environnement brut et d’autre part le milieu tel qu’il s’est élaboré dans sa relation évolutionnaire et historique avec le sujet. Il faut rejeter en puissance un anthropocentrisme radical : celui-ci vide la nature de tout sens, et de toute valeur.

Quelques centaines de milliers de petits visiteurs venus de l’espace interstellaire débarquent sur Terre toutes les vingt-quatre heures. Il faut les protocoles de la science pour en faire des abstractions : de purs objets, autant que possible.

Aragonite, gypsum, halite, pyrite, olivenite, dolomite.

Mais la réalité concrète, c’est autre chose. Il chante les phénomènes du monde. Quiconque veut s’en tenir à la conviction que les êtres vivants ne sont que des machines, abandonne l’espoir de ne jamais entrevoir leurs milieux.

— Maintenant tu vois : je me rappelle mieux que ce que j’ai senti, l’autre jour, au bord de la mer, quand je tenais ce galet. C’était une espèce d’écœurement douçâtre. Que c’était désagréable ! Et cela venait du galet dans mes mains. Oui, c’est cela, c’est bien cela : une sorte de nausée dans les mains.

Lever de soleil sur maquette. L’eau scintille, paillettes sur maquette. Comme si une couche de magnésie se détachait en surface. J’écoute l’eau qui tombe en mouvement perpétuel. Et dans ce rythme infini, tout est figé dans l’absolu. Le processus est théoriquement infini, et il serait virtuellement possible qu’un seul atome produise des clones de lui-même en nombre infini, et qu’ainsi il remplisse l’univers entier, d’où simultanément tout le temps se sera écoulé en un ultime retour au zéro macroscopique.

— L’univers changera mais pas toi Béatriz. Mélancolique vanité ; en de certaines occasions, je le sais, ma vaine passion l’avait exaspérée ; morte, je pouvais me consacrer à sa mémoire, sans espoir mais aussi sans humiliation. Chair imaginée entre vernis et plâtre dans des salles de musées obscures, je regarde le passé.

J’observe les fruits de l’évolution imperceptible que rien ne semble perturber. Des mesures vertigineuses, des témoins, des indices.

Quand j’ouvris les yeux je vis le lieu où se trouvent, sans se confondre, tous les lieux de l’Univers, vus de tous les angles.

Note :

Ce senton sédimentaire a été composé d'après les oeuvres suivantes : La Nausée de Jean-Paul Sartre, L'Aleph de Jorge Luis Borges, Mondes animaux et monde humain suivi de La théorie de la signification de Jakob von Uexküll, The sea and its wonders de Cyril Hall, Poétique de la Terre et Mésologie d'Augustin Berque, Dépositions smithsoniennes & Sujet à un film de Clark Coolidge

0 notes

Text

The World Through the Eyes of an Iskolar

Umwelt (n.) a concept introduced by Jakob von Uexküll in the early 20th century that studies the relationships between living organisms and their environments through the lens of communication and meaning.

Subjective and individualized, it may seem, but it is a collective experience I share with fellow Iskolars. This is how I describe my umwelt as I coexist with every student and every sector. Ironically so, I am only unique because of my similarity with the community.

This subjective perception is rooted in my idea of the social construction of reality — one that can be built and changed over time. Thus, I believe that my umwelt is a collection of sensory experiences and interpretations of the environment that I want to share with others.

Throughout my trips to other University of the Philippines (UP) campuses, I found that my experiences in my campus unit are closely intertwined with the issues of Iskolars across the nation. In Southern Tagalog, I saw how fascism takes its form through trumped-up charges much like how it did with Cebuano activists. In Mindanao, I witnessed the bravery of the youth in the face of intimidation and threat in the same way that the multi-sect of Cebu faced numerous cases of attacks.

In every sense of the word, my umwelt is the struggle that I am part of no matter what part of the Philippines I may reach.

1 note

·

View note

Text

On Point of View

Today, we learned the concept of the "Umwelt", a term coined by biologist Jakob von Uexküll to mean one's environment or surrounding world. It revolves around the idea that every organism experiences its surroundings uniquely, with its point of view dictating the type of sensory and perceptual interactions it has with the world. It shows how reality is subjectively constructed, as each organism has a distinct way of interpreting its environment.

An example of a bee's Umwelt (as illustrated by von Uexkül, 1934):

Scrolling through my photos, I realized how I take random pictures at different times of the day to show what I am doing or going through. These photos then serve as a representation of my Umwelt— a concrete rendering that can make others see how I perceive my surroundings. In this case, digital means enable us to view the world through the eyes of other individuals.

POV: You're Airam going about her day

0 notes

Text

When zoologist Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919) coined the word ecology in 1866 he defined it as “the relation of the animal to its organic and inorganic environment.” But did he coin it? Aristotle, arguably the world’s first zoologist, gave a tantalizing preview of the idea in Parts of Animals, written around 350 BCE. Aristotle urges us to study animals closely for what they reveal about the larger world around us, including ourselves, for, as he puts it, “Nature does nothing in vain,” and “in all of Nature there is something wonderful.” His insistence that scientific investigation should always be concerned with systemic wholes is particularly inspired:

Someone who discusses individual parts and their arrangements is not describing their material composition for its own sake but is concerned rather with the conformation of a whole. The same is true of a house—it’s the whole structure that matters, not the bricks, mortar, and timber. Likewise, too, in Nature: the objective is to describe the synthetic whole, not the individual parts that do not occur separately apart from their combination as an entity.

The use of the image of a house (oikos) to describe our domestic arrangement with the biosphere lies, of course, at the etymological and conceptual heart of “ecology”—and “ecosystem” for that matter, a related word, coined in 1935. It is no dead metaphor, and far older than Haeckel or the nineteenth century. The Earth is home to organisms of all sorts.

Biologist Jakob von Uexküll (1864–1944)—pronounced “oox-cool”—elaborated on this idea, dubbing an organism’s environs its Umwelt, a bubble in which both space and time are wholly relative, experienced and navigated uniquely by each species depending on its morphology and sensory receptors. Umwelt, which simply means “environment” in German, is a crucial concept for modern ecology, and a necessary corrective to anthropic bias in human inquiry generally.

The poster child for Uexküll’s thesis is a tiny creature that Nature lovers are bound to encounter on any walk in the woods or gambol through the grass—the ubiquitous tick. The tick has no eyes, cannot hear sounds, and has no sense of taste. It spends most of its time perched at the tip of a blade of grass or under the leaf of a shrub. Astonishingly, a tick can go for eighteen years without eating. It is stimulated to feed only by detecting the presence of butyric acid, which emanates from the skin glands of mammals. The butyric acid provides a chemical signal for the tick to drop from its perch and scurry onto whatever unsuspecting passer-by is unlucky enough have brushed up against or near where it’s lurking. But that sets just the first stage of attack in motion. Contact with the hair of the animal stimulates the tick to crawl around in search of a hairless spot on the skin. Whereupon it is the sensation of warmth from the host’s body—not sight or taste, for the tick lacks the requisite organs, and the butyric acid only impels it to initiate action—that triggers it to bite and feed. Once the tick has gorged itself with the blood of its victim, all that’s left for it to do is to detach from its host, lay its eggs on the ground and die, which it soon does.

What so impressed Uexküll, and should catch our attention as well, is that out of the hundreds of stimuli radiating from any mammal’s body, only three serve as cues for the sensory receptors available to the tick: a chemical stimulus of butyric acid sets the process in motion; a tactile stimulus from the animal’s coat directs it to scour around until it finds a bald patch; and heat, which induces it to bore into the skin. Remarkably, each stimulus works in a definite sequence. What is more, the mammalian host is not really a passive victim at all, but an active participant in a reciprocal scheme: it generates the stimuli in the first place, by virtue of its own chemical and physical characteristics.

The Umwelten of all organisms tell a similar tale. The tick instantiates Uexküll’s arresting conclusion that every creature in Nature “lives in a world composed of subjective realities alone, and that even the Umwelten themselves represent only subjective realities.” This affirmation, based on empirical research on thousands of organisms, speaks volumes about agency in Nature. “Without a living subject,” Uexküll writes, “there can be neither space nor time.” Given the diversity and multiplicity of organisms on the planet, each with its own unique Umwelt, to say that there are many worlds and hidden realms around us is not a figurative expression, or an exaggeration.

Umwelt research corroborates Aristotle’s view that Nature does nothing in vain. On this point Uexküll himself was careful to distinguish between what he calls a goal and a plan. Actions and reactions in an organism’s Umwelt are not purposeful, he suggests, meaning they are not the result of a goal the subject has in view. They are attributable rather to Nature’s plan, which is the result of long co-evolutionary processes. It used to be thought, and is still commonly said, that non-human creatures do what they do by instinct. But instinct doesn’t get us very far. It is a vacuous term, tantamount to saying that we don’t know exactly how or why organisms do what they do. Ethology and even everyday observations of animals, however, give us a better inkling of what’s going on than simply chalking things up to instinct and illustrate likewise the difference between a subject’s goal and Nature’s plan.

Here are two examples.

If you tie a chick’s leg to a ground stake with a string, and I’m not suggesting that you try this at home, it will flail about trying to get away and peep vigorously. The mother hen takes the chick’s peeping as an auditory cue that an intruder is nearby and will thrust out her beak and peck about energetically in the air around the chick, like a shadow boxer, even though there is no predator in sight. If you put that peeping chick under glass so that it is still visible but makes no sound, however, still struggling to escape its tether and in distress though it be, the hen is unfazed and goes about her business as usual, because the perceptual cue of the chick’s peeping, which induces her to peck defensively, is absent. It’s not her goal, in other words, to look out for her chick, come what may. She doesn’t and cannot see the problem is that the chick has its leg tied to a stake. She can only act on the specific stimuli she has evolved to respond to.

Sheep behave similarly. (This my wife and I have tried at home, too many times.) A mother ewe recognizes her lambs by smell and sound, not sight. To entice a new mother into the barn after she’s given birth you need to hold the lamb to her nose and walk slowly, incrementally, to get her to follow. If the lamb is baaing, all the better. Were you to just scoop the lamb up, turn your back, and clamber off, the ewe would run about frantically, sniffing all the other lambs in the barnyard, baaing vociferously, searching for hers. The primacy of the olfactory receptor in ewes is also why the old shepherd’s trick of “grafting” an orphaned or rejected lamb onto a mother who has lost one of her own by flaying her dead lamb and pulling its skin like a sweater over the orphan lamb works so remarkably well. Sheep are not stupid. They’re just keen-scented.

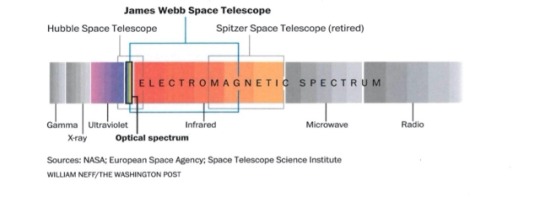

We see that the Webb Telescope is an improvement of considerable magnitude on the Hubble, which it replaces. It can capture much more of the infrared spectrum. Yet the mere sliver of the universe’s electromagnetic radiation that falls within human beings’ optical window, as illustrated above, should give us pause. Most of what exists is invisible. Impressively, we have developed instruments to measure gamma, x-ray, ultraviolet, infrared, microwave, and radio frequencies. But we cannot see them. The images of planets, stars, and distant galaxies that we pore over in glossy magazines and that so inspire us are produced using false-color imaging. That is, colors within the optical spectrum are assigned to wavelengths that we cannot see to bring into view physical features that are not otherwise discernible. Slow-motion and time-lapse photography perform a similar trick to compensate for the limitations we face in processing time. The recent David Attenborough documentary The Green Planet (2022) utilizes new photographic techniques that can capture the growth patterns and dynamic behaviours of trees, flowers, vines, and other vegetation over time in stunning detail, revealing that plants, too, respond to stimuli in ways analogous to organisms. They, too, have their own Umwelten.

But it gets worse, or better, depending on your view of humanity’s right and proper place in the cosmos. American philosopher Thomas Nagel, with nary a word about Uexküll or Umwelt, argued for a similar outlook in his classic essay from 1974 “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” The paper, one should be quick to note, is not really about bats at all. Rather, it’s a critique of reductionism in science and a demonstration of the limits of physicalism as an explanatory criterion. We cannot know subjectively, experientially, what it’s like to be a bat, Nagel shows. The morphologies and sensory receptors of humans and bats are too alien from one another for that to be possible. Even imagining what it’s like to be a bat inevitably projects human sensibilities onto the would-be experience. We get Batman, not a bat. Yet we can infer beyond much doubt that bats themselves must be capable of experiencing what it’s like to be one. Nagel’s verdict cuts to the chase about the significance of the issue: “Reflection on what it is like to be a bat seems to lead us, therefore, to the conclusion that there are facts that do not consist in the truth of propositions expressible in human language.” And yet, he concedes, “strangely enough, we may have evidence for the truth of something we cannot fully understand.” Uexküll, for one, provides such evidence with his Umwelt thesis. That bats possess subjective experience of what it’s like to be a bat, which is beyond our own experiential reach, is proof of the existence of facts about the world that we may never apprehend.

To study animals, Aristotle suggests, is to hold up a mirror to ourselves. Even small or repellent creatures—leeches, say, or maggots—should compel our attention, as the causes and purposes of their morphology and behavior contribute to a better understanding of our place in the world. People, after all, are animals, too. One can only imagine the field day Aristotle would have had with DNA. As is well known now, but wholly unknown then, 99% of our genetic information is shared with chimpanzees. We have about 90% in common with mice; 65% with chickens, which are not even mammals; 60% with bananas, which are not even animals. It is hardly trite or a truism to insist that all living things are connected.

Visionary designer and craftsman William Morris (1834–1896) once famously declared “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or think to be beautiful.” Aristotle says that such is already the case in Nature: whatever pertains to ecology also possesses beauty. This is so, he says, because purpose, not chance, characterizes the arrangement of parts in this world. It falls to us to understand and act on those arrangements. There is much we don’t know, or perhaps cannot know. What is, however, outstandingly clear, and what animals teach us time and again, is that in all of Nature there is something wonderful.

M. D. Usher is the Lyman-Roberts Professor of Classical Languages and Literature and a member of the Department of Geography and Geosciences at the University of Vermont. With his wife, he also built, owns, and operates Works & Days Farm, which produces lamb, eggs, and maple syrup in Shoreham, Vermont. His books include How to Be a Farmer: An Ancient Guide to Life on the Land and How to Say No: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Cynicism (both Princeton).

0 notes

Text

1015.

Finished reading A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men, by Jakob von Uexküll. Very interesting little book. Some ideas are clearly outdated, and this is evident even for someone without any background in biology such as me. Still, the ideas presented are very valuable, and I'm glad that I read it. I will be using some of its ideas to develop my own arguments about Umwelten and why it's important to think of animals taking this concept into account.

0 notes

Quote

What could an entity that constructs billions or trillions of inferences, networks of inferences, and networks of networks, learn about human languages, cultures, and social relations from ingesting billions of human-authored texts, in the absence of any real-world experience? My answer is, quite a lot. There would of course be what I call a systemic fragility of reference, in which the lack of grounding in real world experience leads to errors of interpretation and fact. LLMs are like the figure, beloved by philosophers, of a brain in a vat; they construct models not of the world, but only models of language. Nevertheless, embedded in the immense repertoire of human-authored texts on which LLMs are trained are any number of implications about the human world of meanings. These are understood in the contexts of what LLMs can and do apprehend, that is, in relation to their world-horizons, or in a phrase that Jakob von Uexküll usefully designated for biological world-horizons, their umwelten.[2] Just as von Uexküll used the term umwelt to emphasize that all biological creatures have species-specific ways of perceiving the world, so LLMs also have distinctive ways of apprehending the world.

Afterword: Learning to Read AI Texts | In the Moment

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

"Thus, these two components—perception and action—largely define and circumscribe the world for every living thing. All animals have their own umwelten—their own subjective realities, what von Uexküll thought of as 'soap bubbles' with them forever caught in the middle." Alexandra Horowitz from Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know

#quotes#alexandra horowitz#inside of a dog#dogs#have a field for watching scenery#house wolf#domestication syndrome#jakob von uexküll#umwelten#wittgenstein’s theory of experiential epistomology#bubbly thoughts#when in doubt#enjoy a dogs snout#dog life

2 notes

·

View notes