#LATE ARCHAIC TO EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD

Text

A GREEK BRONZE CORINTHIAN HELMET

LATE ARCHAIC TO EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD, CIRCA 525-475 B.C.

#A GREEK BRONZE CORINTHIAN HELMET#LATE ARCHAIC TO EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD#CIRCA 525-475 B.C.#bronze#bronze helmet#military equipment#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history

211 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you make a post about the evolution of Greek art from the ancient times until now in modern age?

Because we often talk about the evolution of art but unfortunately we don't appreciate after ancient times the other art movements Greece went through the centuries.

That’s true! I am sorry for taking ages to answer this but I don't know how it could take me less anyway hahaha I made this post with summaries about all artistic eras in Greek history. I have most of it under a cut because with the addition of pictures it got super long, but if you are interested in the history of art I recommend giving it a try! I took advantage of all 30 pictures that can be possibly attached in a tumblr post and I tried to cover as many eras and art styles as possible, nearly dying in the process ngl XD I dedicated a few more pictures in modern art, a) because that was the ask and b) because there is more diversity in the styles that are used and the works that are available to us in great condition in modern times.

History of Greek Art

Greek Neolithic Art (c. 7000 - 3200 BC)

Obviously, with this term we don’t mean there were people identifying as Greeks in Neolithic times, but it defines the Neolithic art corresponding to the Greek territory. Art in this era is mostly functional, there are progressively more and more defined designs on clay pots, tools and other utility items. Clay and obsidian are the most used materials.

Clay vase with polychrome decoration, Dimini, Magnesia, Late or Final Neolithic (5300-3300 BC).

Cycladic Art (3300 - 1100 BC)

The art of the Cycladic civilisation of the Aegean Islands is characterized by the use of local marble for the creation of sculptures, idols and figurines which were often associated to womanhood and female deities. Cycladic art has a unique way of incidentally feeling very relevant, as it resembles modern minimalism.

Early Cycladic II (Keros-Syros culture, 2800–2300 BC)

Minoan Art (3000-1100 BC)

The advanced Minoan civilisation of Crete island was projecting its confidence and its vibrancy through its various arts. Minoan art was influenced by the earlier Egyptian and Near East cultures nearby and at its peak it overshadowed the rest of the contemporary cultures and their artistic movements in Greece. Colourful, with numerous scenes of everyday life and island life next to the sea, it was telling of the society’s prosperity.

The Bull-leaping fresco from Knossos, 1450 BC.

Mycenaean Art (c. 1750 - 1050 BC)

Mycenaean Art was very influenced by Minoan Art. Mycenaean art diverged and distinguished itself more in warcraft, metalwork, pottery and the use of gold. Even when similar, you can tell them apart from their themes, as Mycenaean art was significantly more war-centric.

The Mask of Agamemnon in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. The mask likely was crafted around 1550 BC so it predates the time Agamemnon perhaps lived.

Geometric Art (1100 - 700 BC)

Corresponding to a period we have comparatively too little data about, the Geometric Period or the Homeric Age or the Greek Dark Ages, geometric art was characterized by the extensive use of geometric motifs in ceramics and vessels. During the late period, the art becomes narrative and starts featuring humans, animals and scenes meant to be interpreted by the viewer.

Detail from Geometric Krater from Dipylon Cemetery, Athens c. 750 BC Height 4 feet (Metropolitan Museum, New York)

Archaic Art (c. 800 - 480 BC)

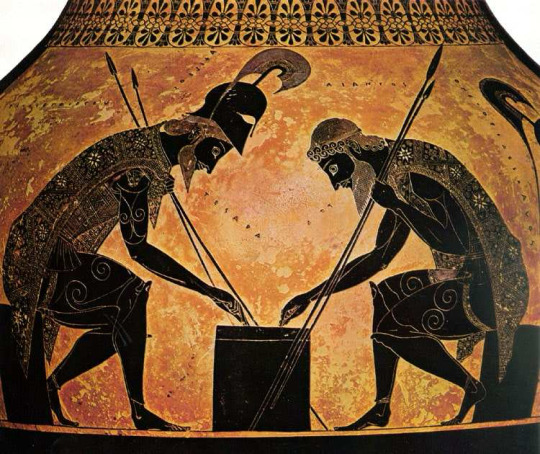

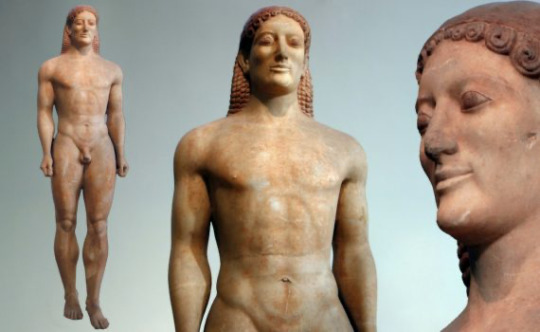

The art of the archaic period became more naturalistic and representational. With eastern influences, it diverged from the geometric patterns and started developing more the black-figure technique and later the red-figure technique. This is also the earliest era of monumental sculpture.

Achilles and Ajax Playing a Board Game by Exekias, black-figure, ca. 540 B.C.

Kroisos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.

Classical Art (c. 480 - 323 BC)

Art in this era obtained a vitality and a sense of harmony. There is tremendous progress in portraying the human body. Red-figure technique definitively overshadows the use of the black-figure technique. Sculptures are notable for their naturalistic design and their grandeur.

The Diskobolos or Discus Thrower, Roman copy of a 450-440 BCE Greek bronze by Myron recovered from Emperor Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli, Italy. (British Museum, London). Photo by Mary Harrsch.

Terracotta bell-krater, Orpheus among the Thracians, ca. 440 BCE, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Hellenistic Art (323 - 30 BCE)

Hellenistic art perfects classical art and adds more diversity and nuance to it, something that can be explained by the rapid geographical expansion of Greek influence through Alexander’s conquests. Sculpture, painting and architecture thrived whereas there is a decrease in vase painting. The Corinthian style starts getting popular. Sculpture becomes even more naturalistic and expresses emotion, suffering, old age and various other states of the human condition. Statues become more complex and extravagant. Everyday people start getting portrayed in art and sculpture without extreme beauty standards imposed. We know there was a huge rise in wall painting, landscape art, panel painting and mosaics.

Mosaic from Thmuis, Egypt, created by the Ancient Greek artist Sophilos (signature) in about 200 BC, now in the Greco-Roman Museum in Alexandria, Egypt. The woman depicted in the mosaic is the Ptolemaic Queen Berenike II (who ruled jointly with her husband Ptolemy III) as the personification of Alexandria.

Agesander, Athenodore and Polydore: Laocoön and His Sons, 1st century BC

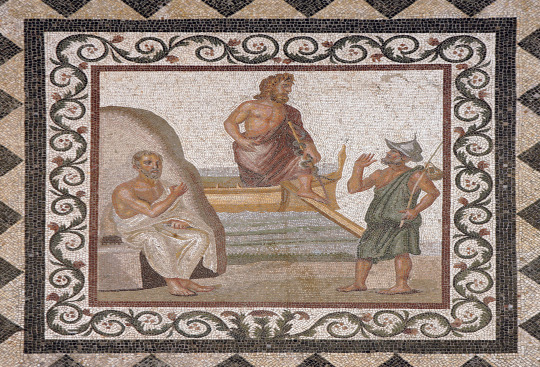

Greco-Roman Art (30 BC - 330 AD)

This period is characterized by the almost entire and mutually influential merging of Greek and Roman artistic expression, in light of the Roman conquest of the Hellenistic world. For this era, it is hard to find sources exclusively for Greek art, as often even art crafted by Greeks of the Roman Empire is described as Roman. In general, Greco-Roman art reinforces the new elements of Hellenistic art, however towards the end of the era, with the rise of early Christianity in the Eastern aka the Greek-influenced part of the empire, there are some gradual shifts in the art style towards modesty and spirituality that will in time lead to the Byzantine art. During this era mosaics become more loved than ever.

A mosaic from the island of Kos (the birthplace of Hippocrates) depicting Hippocrates (seated) and a fisherman greeting the god Asklepios (center) as he either arrives or disembarks from the island. Second or third century CE.

Introduction to Byzantine Art

Byzantine art originated and evolved from the now Christian Greek culture of the Eastern Roman Empire. Although the art produced in the Byzantine Empire was marked by periodic revivals of a classical aesthetic, it was above all marked by the development of a new aesthetic defined by its salient "abstract", or anti-naturalistic character. If classical art was marked by the attempt to create representations that mimicked reality as closely as possible, Byzantine art seems to have abandoned this attempt in favor of a more symbolic approach. The subject matter of monumental Byzantine art was primarily religious and imperial: the two themes are often combined.

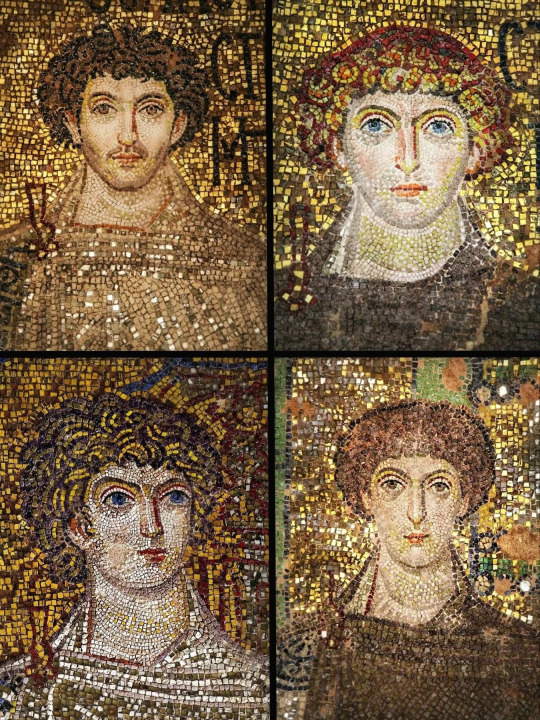

Early Byzantine Art (330 - 842 AD)

The establishment of the Christian religion results in a new artistic movement, centered around the faith. However, ancient statuary remains appreciated. Most fundamental changes happen in monumental architecture, the illustration of manuscripts, ivory carving and silverwork. Exceptional mosaics become integral in artistic expression. The last 100 years of this period are defined by the Iconoclasm, which temporarily restricts entirely the previously thriving figural religious art.

Mosaics in the Rotunda of Thessaloniki, 4th - 6th century AD.

Macedonian Art & Komnenian Age (843 - 1204 AD)

These artistic periods correspond to the middle Byzantine period. After the end of the Iconoclasm, there is a revival in the arts. The art of this period is frequently called Macedonian art, because it occurred during the Macedonian imperial dynasty which generally brought a lot of prosperity in the empire. There was a revival of interest in the depiction of subjects from classical Greek mythology and in the use of Hellenistic styles to depict religious subjects. The Macedonian period also saw a revival of the late antique technique of ivory carving. The following Komnenian dynasty were great patrons of the arts, and with their support Byzantine artists continued to move in the direction of greater humanism and emotion. Ivory sculpture and other expensive mediums of art gradually gave way to frescoes and icons, which for the first time gained widespread popularity across the Empire. Apart from painted icons, there were other varieties - notably the mosaic and ceramic ones.

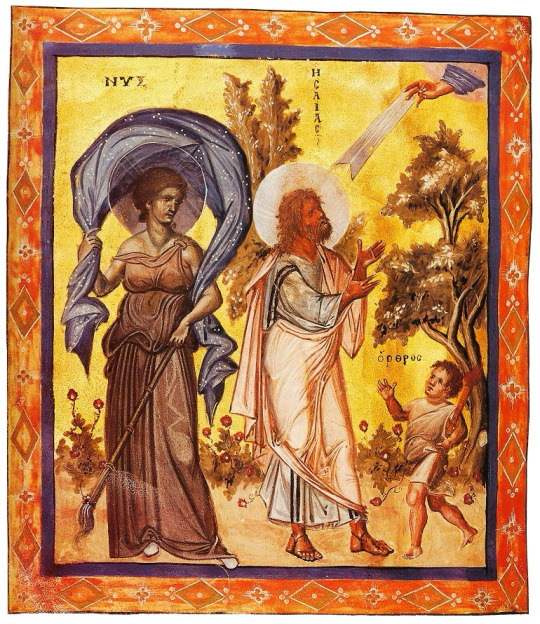

Paris Psalter, 10th century AD. Prophet Isaiah from the Old Testament in the company of the symbolisms for night (clear inspiration drawn from the ancient deity Nyx) and morning (Orthros, not to be confused with the mythological creature).

Palaeologan Renaissance (1261 - 1453)

The Palaeologan Renaissance is the final period in the development of Byzantine art. Coinciding with the reign of the Palaeologi, the last dynasty to rule the Byzantine Empire (1261–1453), it was an attempt to restore Byzantine self-confidence and cultural prestige after the empire had endured a long period of foreign occupation. The legacy of this era is observable both in Greek culture after the empire's fall and in the Italian Renaissance. Contemporary trends in church painting favored intricate narrative cycles, both in fresco and in sequences of icons. The word "icon" became increasingly associated with wooden panel painting, which became more frequent and diverse than fresco and mosaics. Small icons were also made in quantity, most often as private devotional objects.

Detail of Anástasis (Resurrection) fresco, c. 1316–1321, Chora church, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist).

Cretan School (15th - 17th century)

Cretan School describes an important school of icon painting, under the umbrella of post-Byzantine art, which flourished while Crete was under Venetian rule during the Late Middle Ages, reaching its climax after the Fall of Constantinople, becoming the central force in Greek painting during the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. By the late 15th century, Cretan artists had established a distinct icon-painting style, distinguished by "the precise outlines, the modelling of the flesh with dark brown underpaint, the bright colours in the garments, the geometrical treatment of the drapery and, finally, the balanced articulation of the composition". Contemporary documents refer to two styles in painting: the maniera greca (in line with the Byzantine idiom) and the maniera latina (in accordance with Western techniques), which artists knew and utilized according to the circumstances. Sometimes both styles could be found in the same icon. The most famous product of the school was the painter Domenikos Theotokopoulos, internationally known as El Greco, whose art evolved and diverged significantly in his later years when he moved in Spain and was involved in the Spanish Renaissance, and though it often alienated his western contemporary artists, nowadays it is viewed as an incidental early birth of Impressionism in the mid of the Renaissance’s peak.

Icon by Andreas Pavias (1440-1510), Cretan School, from Candia (Venetian Kingdom of Crete). The Latin inscription suggests the icon was meant for commercial purposes in Western Europe. National Museum, Athens. (Source: https://russianicons.wordpress.com/tag/cretan-school/)

Crucifixion (detail), El Greco (Doménikos Theotokópoulos), ca. 1604 - 1614.

Heptanesian School (17th - 19th century)

The Heptanesian school succeeded the Cretan School as the leading school of Greek post-Byzantine painting after Crete fell to the Ottomans in 1669. Like the Cretan school, it combined Byzantine traditions with an increasing Western European artistic influence and also saw the first significant depiction of secular subjects. The center of Greek art migrated urgently to the Heptanese (Ionian) islands but countless Greek artists were influenced by the school including the ones living throughout the Greek communities in the Ottoman Empire and elsewhere in the world. Greek art was no longer limited to the traditional maniera greca dominant in the Cretan School. Furthermore, the Heptanesian school was the basis for the emergence of new artistic movements such as the Greek Rocco and Greek Neoclassicism. The movement featured a mixture of brilliant artists.

Archangel Michael, Panagiotis Doxaras, 18th century.

Greek Romanticism (19th century)

Modern Greek art, after the establishment of the Greek Kingdom, began to be developed around the time of Romanticism. Greek artists absorbed many elements from their European colleagues, resulting in the culmination of the distinctive style of Greek Romantic art, inspired by revolutionary ideals as well as the country's geography and history.

Vryzakis Theodoros, The Exodus from Missolonghi, 1853. National Gallery, Athens.

The Munich School (19th century Academic Realism)

After centuries of Ottoman rule, few opportunities for an education in the arts existed in the newly independent Greece, so studying abroad was imperative for artists. The most important artistic movement of Greek art in the 19th century was academic realism, often called in Greece "the Munich School" because of the strong influence from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Munich where many Greek artists trained. In academic realism the imperative is the ethography, the representation of urban and/or rural life with a special attention in the depiction of architectural elements, the traditional cloth and the various objects. Munich School painters were specialized on portraiture, landscape painting and still life. The Munich school is characterized by a naturalistic style and dark chiaroscuro. Meanwhile, at the time we observe the emergence of Greek neoclassicism and naturalism in sculpture.

Nikolaos Gyzis, Learning by heart, 1883.

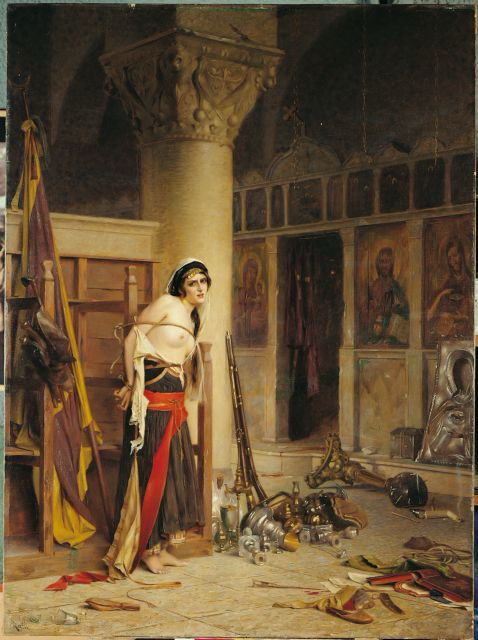

Rallis Theodoros, The Booty, before 1906.

20th Century Modern & Contemporary Greek Art

At the beginning of the 20th century the interest of painters turned toward the study of light and color. Gradually the impressionists and other modern schools increased their influence. The interest of Greek painters, artists changes from historical representations to Greek landscapes with an emphasis on light and colours so abundant in Greece. Representatives of this artistic change introduce historical, religious and mythological elements that allow the classification of Greek painting into modern art. The era of the 1930s was a landmark for the Greek painters. The second half of the 20th century has seen a range of acclaimed Greek artists too serving the movements of surrealism, metaphysical art, kinetic art, Arte Povera, abstract excessionism and kinetic sculpture.

Yiannis Moralis, Two friends, 1946.

Art by Giannis Gaitis (1923-1984), famous for his uniformed little men.

By Yorghos Stathopoulos (1944 - )

Art (detail) by Nikos Engonopoulos (1907 - 1985)

Folk, Modern Ecclesiastical and Secular Post-Byzantine Art

Ecclesiastical art, church architecture, holy painting and hymnology follow the order of Greek Byzantine tradition intact. Byzantine influence also remained pivotal in folk and secular art and it currently seems to enjoy a rise in national and international interest about it.

A modern depiction of the legendary hero Digenes Akritas depicted in the style of a Byzantine icon by Greek artist Dimitrios Skourtelis. Credit: Dimitrios Skourtelis / Reddit

Erotokritos and Aretousa by folk artist Theophilos (1870-1934)

Example of Modern Greek Orthodox murals, Church of St. Nicholas.

Ancient Greek philosophers depicted in iconographic fashion in one of Meteora’s monasteries. Each is holding a quote from his work that seems to foreshadow Christ. Shown from left to right are: Homer, Thucydides, Aristotle, Plato and Plutarch. This is not as weird as it may initially seem: it was a recurrent belief throughout the history of Christian Greek Orthodoxy that the great philosophers of the world heralded Jesus' birth in their writings - it was part of the eras of biggest reconciliation between Greek Byzantinism and Classicism.

Prophet Elijah icon with Chariot of Fire, Handmade Greek Orthodox icon, unknown iconographer. Source

If you see this, thanks very much for reading this post. Hope you enjoyed!

#greece#art#europe#history#culture#greek art#artists#greek culture#history of art#classical art#ancient greek art#byzantine greek art#christian art#orthodox art#modern art#modern greek art#anon#ask

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medusa having a good time :D

Design breakdown + Explaination below the cut

Reblog, do not repost. Comissions are open!

So, I recently had a late-night class on Medusa and her various depictions across time, and I felt very inspired by my prof’s descriptions of her and also intensely frustrated by the mythos as a whole, because unless you buy into one of the dozens of - fun but not historically backed - feminist retellings of her story, there really is nothing satisfying to Medusa, her fate or her death.

But i also felt like the victim part of her life had been more than explored and I honestly just thought her monstrous energy was sick as fuck, so I wanted to show her indulging in a heart and some intestine >:D

Here are some of the sources I used for the design, since she isn't often depicted with wings anymore:

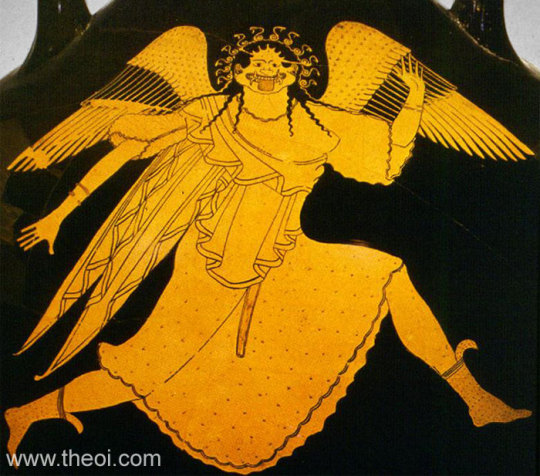

This Vase should be around 600 BC and shows Medusa as a monster with clear inhuman/non feminine features: I borrowed the most from this depiction, since that is what i wanted to embrace. The loincloth is dotted in the style of the depicted fabric, the face has prominent tusks and the large wings turned upwards are also from here.

This is another depiction from a similar timeframe, late archaic/early classical period. This one was mostly an inspiration for the facial features and the way the hair is laid over the head in a way that looks sorta like cornrows, I thought it looked pretty cool!

Lastly, this bust is a roman replica, and is fairly controversial, but I had to include it because the "wing ears" are just awesome and i wanted desperately to include them, even if this bust is significantly younger and removed from the other sources.

All in all, I wanted to make an image of Medusa as a "fun" monstrous lady who is living her best life, and not a seductress (ew. looking at you, giuanni versache) or a tragic figure. She most definitely deserved better, but I like to think she enjoyed herself, too. Thanks for reading, if you made it this far! I oversimplified some things for the sake of making this rant short, but I am also only a first year classicism student, and I didn't take notes during the class, so I may have made some mistakes.

#also the pose and general vibe (and the nakedness) is heavily inspired by my gf?#in the least weird way possible#gorgon#mythical creatures#ancient greek#greek mythology#illustration#digital art#digital artist#junos artwork#ancient greece#roman history#mythology#roman mythology#medusa#tw blood#tw gore#i guess?#art#art and sketches

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

It's so funny (and annoying) seeing people associate Artemis with the moon and Apollo with the sun. Like, people? That's Roman gods Diana and Apollo.

As far as I know Apollo was associated only with the light in Greek mythology but not with the sun, right? That was Helios. And of course Artemis had nothing to do with the moon.

I can see what you mean. It is particularly annoying when "god of the sun/goddess of the moon" are used as their primary identifications, and one of my biggest pet peeves in Trojan War retellings is the characters calling the sun Apollo. It's so anachronistic please stop.

That said, while this idea doesn't really seem to be attested in the Archaic period, the association between these two gods and the sun and moon apparently existed in Classical Greece. To quote Timothy Gantz's Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources:

„Whatever his other early interests, no source prior to the fifth century ever calls (Apollo) the sun (the latter is always Helios or Hyperion). Parmenides and Empedokles may have done so, if a late source can be trusted, but seemingly in the context of philosophic structures that found physical equivalents for many of the gods. Eventually, and for perhaps the same reasons, the idea also surfaces in Orphic texts. But the first sure literary identification of Apollo with the sun occurs no earlier than Euripides, in a fragment of his lost Phaethon (fr 781.10-12 N2), and we cannot tell from the text whether the innovation is his or something previously in circulation. Earlier in the century there are admittedly some suspect moments in Aischylos on this point: we have seen that the playwright probably does link the moon with Artemis (fr 170 R), and his Hiketides (212–14) has been thought by some to call the rays of the sun Apollo. In addition, the same poet's lost Bassarides may have contained a reference to the dismemberment of Orpheus by those women, who we are told were sent by Dionysos because Orpheus ignored him and worshipped only Helios, whom he called Apollo (p. 138 R).

I must confess that I am skeptical of most of this evidence: the tale of Orpheus comes from Ps-Eratosthenes, who cites Aischylos for one brief point near the end of the story, suggesting that the rest of the account (including Helios/Apollo) derives from other sources (Katast 24). 37 As for the Hiketides, the link between Apollo and the sun there is achieved largely by emendation of an (admittedly corrupt) text that originally implied just the opposite. 38 And while different plays are entitled to different views, we should note that in the Choephoroi Helios is addressed by Orestes in a way that emphasizes his separation from Apollo (Cho 984-86). Still, there is the reference to Artemis as the moon, if we have read the fragment correctly. Whenever the connection between god and sun was made, it was surely fostered by Apollo's title of Phoibos, used so often by Homer and the Hymn to Apollo (with or without Apollo added), and meaning (or thought to mean) "shining." But on balance we should probably conclude that the myths of the Archaic period (virtually) always made Helios and Apollo two separate figures; they are never confused in early art.”

In the Iliad scholia, the Theomachy from Books 20-21 is interpreted allegorically and Artemis is said to represent the moon (Hera the air, Hermes reason, etc, and possibly Theagenes of Rhegium (6th century BCE) is responsible for this idea. I can't confirm though whether or not he was cited as a source in the scholia, I'll need to look more into this. Artemis is clearly associated with the moon by Greek authors dating from the Roman period (ex. Plutarch), but her identification with the moon goddess Diana most probably explains why.

Personally I don't refer to Artemis as the goddess of the moon or Apollo the god of the sun, let alone as the actual moon or sun.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

goncharov and the homeric epics

as a classics student I honestly consider this whole goncharov thing to be a kind of breakthrough. for DECADES even CENTURIES people have been debating how the homeric epics were composed orally and I can't help but think that this is it? a community of people encounter a single piece of inspiration, in the case of goncharov a knock off label and in case of homeric society memories of a far-off war, and from it they build something beyond the imagination of any single person. with too much plot to ever fit into a 2 hour movie or two printed books, all communicated by bursts of words, art, and music.

naturally there is the issue that tumblr and the internet as a whole is far more permanent and far-reaching than forms of communication in archaic greece, but I still think that this provides us a feasible answer to the homeric question (that is, who is homer? a single man who composed two epics? a group of people? or is it an abstract term used to help us comprehend a societal phenomenon wherein oral communication and performance has permitted such epics to come into existence? (in case u can't tell I think it's the last one)). tumblr was able to creat goncharov within a matter of days because of the speed and reach if online communication. the odyssey and the iliad, however, we have no specific start and end date for. rather, the period in which they may have been composed stretches from the late 8th to early 7th centuries BCE (Before Common/Current Era) - what's to say it wasn't in the process of composition that entire time? slowly, very slowly, word would have spread from person to person, each adding their own ideas, characters, and themes, until a plot began to emerge, over the course of many, many years. then came the bards, the performers, who pieces together these floating ideas until they had something cohesive, which they then performed at festivals or privately or wherever, and then their audience would add their own ideas - to put in into modern terms, "fanfiction" and "headcanons" would make excellent equivalents.

or maybe the artwork came first. vase paintings, graffiti; anything to act as an outlet to preserve just a few of these ideas that otherwise would disappear as human memory fades. goncharov has an advantage in that way, as posts online are more accessible and, to an extent, immortal, while the spoken word is quick to dissipate and material items are perishable. for as long as tumblr survives (which it's proven itself to be very good at), those fanarts and posts will remain preserved in their original condition.

I'm no expert on all things goncharov but I checked out the masterdoc for the basic plot and one thing that stood out to me was the "debated scenes" section, because that's some thing that always bothered me about the epics. what is translated of homer is mostly drawn from manuscripts dated to around the medieval period, many many years after the epics were supposedly composed - meaning that, as oral tradition began to lose its popularity, the epics were recorded physically, and in doing so lost their flexibility. I have no doubt that there are hundreds, even thousands of different versions of the homeric epics, whether those are complete narratives - like goncharov, with it's "directors cut" and "private screening" versions - or individual scenes and stories that slot into the (arguably shaky) narrative we currently have, just like goncharov. I truly hope that, unlike this, no one tries to permanently tie goncharov down into one "correct" narrative, because what makes this phenomena so great, and what makes the oral tradition so great, is precisely it's flexibility.

there is a beauty in ambiguity, that is only emphasised by our yearning to find the "truth". for homer's epics, that ambiguity has somewhat (not entirely!) been lost as people settled with the narrative we have been given as the "true" version, but for goncharov, which has essentially been plucked from the air rather than dug up from under thousands of years of history, ambiguity is its main allure and the reason it has gained so much popularity - people saw the potential in its ambiguity, picked it up and ran with it. and, all those thousands of years ago, an ancient people very well may have done the same.

I could go on to talk about thematic similarities because it makes me laugh how society continues it's tendency towards homoeroticism to the point that, when a microcosm of a global (though primarily english-speaking) community is given the chance to create an entirely new piece of media with so little prerequisite they immediately saturate it with homoerotic subtext and, in some of the "debated scenes" they just make it fully homosexual which I respect so much you people are geniuses and the ancient greeks would be proud (also the parallels between goncharov and andery and achilles and patroclus are THERE and you bet I'm going to talk about them. just not right now lol). but unfortunately I have many essays to write on this very topic that I have been ignoring! so enjoy this rant I hope it's not entirely unintelligible!!

#goncharov#gonchandrey#classics#homer's iliad#homer's odyssey#epic poetry#patrochilles#i discovered goncharov (1973) two days ago and if anything happened to it I'd kill everything in this room and then myself#literary analysis#i guess#excuse the messy tags im primarily a twitter user but i have many words and twitter dies not have enough characters#kinda wanna show this to my greek and roman narrative lecturer i think she'd like it#came back to tumblr specifically to talk about this im now going to disappear for another couple years

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Pomegranates, with their many jellied seeds, their delicious refreshing taste, and their applelike appearance, were natural votives to fertility deities. They have been found in the area of Sumer and Akkad from the third millennium and became popular at Mycenae in the late Bronze Age and in Cyprus and Ionia by 900 B.C.46 No other Greek site of the early Archaic period was as rich in clay pomegranate votives as the Samian Heraion, and this fruit retained its association with Hera throughout antiquity among her votives at Argos, Delos, and Italiote Paestum. Both Hera figurines at Archaic Paestum and her Classical cult statue by Polykleitos at the Argive Heraion held pomegranates in their hands. As late as the second century A.D., the pomegranate was known as Hera's tree.”

(Philostratus Vita Apollonti 428).

- The Transformation of Hera: A Study of Ritual, Hero, and the Goddess in the Iliad

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roman Republic Reading List

@hortensius : Hope this is helpful!

Comprehensive Exam, Major Field: Roman History, c. 400-100

Preliminary Reading List--Updated

General

Rosenstein, Rome and the Mediterranean (2012) [general survey]

Steel, End of the Roman Republic (2012) [general survey]

Flower, Roman Republics (2010)

Lomas, Roman Italy 338 BC-AD 200 (this is a sourcebook with introductory discussions)

Farney/Bradley, Peoples of Ancient Italy (2017) (a reference handbook)

Early Republic

Cornell, Beginnings of Rome (1996)

Forsythe, A Critical History of Early Rome (2006)

Armstrong, War and Society in Early Rome (2016)

Lomas, Rise of Rome (2018)

Smith, The Roman Clan (2009)

Armstrong, War and Society in Early Rome: From Warlords to Generals (2016)

Raaflaub (ed), Social Struggle in Archaic Rome, 2nd ed. (2008)* [edited volume with a lot of good chapters, especially Raaflaub, Cornell, Richard, Mitchell, Lindferski]

Terrenato, The early Roman expansion into Italy. Elite negotiation and family agendas (2019)

Middle Republic: Imperialism

Earlier period

Hölkeskamp, “Conquest, competition and consensus: Roman expansion in Italy and the rise of the nobilitas,” Historia 42 (1993) 12-39

Raaflaub, "Born to be Wolves? Origins of Roman Imperialism," in E. Harris & R. W. Wallace (eds.), Transitions to Empire in the Graeco-Roman World, 360-146 B.C. (1996) 273-314.

Terrenato, Early Roman Expansion into Italy (2019)

Fronda, Between Rome and Carthage (2011)

Motives, nature of Roman Expansion (the “Harris debate”)

Harris, War and Imperialism in Republican Rome (1979)

North, Development of Roman Imperialism (review of Harris), JRS 71 (1981) 1-9

Sherwin-White, Rome the Aggressor? (review of Harris), JRS 70 (1980) 177-181

Rich, Fear Greed and Glory: the Causes of Roman War Making in the Middle Republic, in Rich/Shipley, War and Society in the Roman World (1995) 38-68

Eckstein, Senate and General (1987)

Eckstein, Mediterranean Anarchy, Interstate War, and the Rise of Rome (2007)

Griffin, “Iure Plectimur. The Roman Critique of Roman Imperialism.” In Brennan and Flower (eds) East & West. Papers in Ancient History Presented to Glenn W. Bowersock (2008) [gives insight into why Roman historians give speeches to enemies of Rome, which could tie into presentation of captives]

Riggsby, Caesar in Gaul and Rome: War of Words (2021)

Provincialization, also response to Harris

Richardson, Hispaniae (1989)

Gruen, Hellenistic World and Coming of Rome (1986)

Kallett-Marx, Hegemony to Empire (1996)

Diaz Fernandez, Provinces and Provincial Command in republican Rome (2021)

Roman Political Culture (middle and late RP, and the democracy question)

Feig Vishnia, State, Society, and Popular Leaders in Mid-Republican Rome (2011) [possibly get rid of one of the older Gracchi treatments]

Hölkeskamp, Reconstructing the Roman Republic (2010)

Hölkeskamp, “The Roman Republic : government of the people, by the people, for the people ?,” Scripta Classical Israeilica 19 (2000) 203-223

Munzer, Roman Aristocratic Parties and Families (trans. 1999, orig. 1920)

Hopkins, Death and Renewal (1985) pp. 31-119

Lintott, Democracy in the Middle Republic

North, “Democratic Politics in Republican Rome,” Past & Present 126 (1990) 3-21

Millar, Crowd in Republican Rome (2002)

Millar, Political Character of the Classical Roman Republic, JRS 74 (1984) 1-19

Morstein-Marx, Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republican (2007)

North, Politics and Aristocracy in the Roman Republic, Classical Philology 85 (1990) 277-287

Lintott, Violence in Republican Rome (1999)

Wiseman, New Men in the Roman Senate (1972)

Archaeology/Topography and politics:

Davies, Architecture and Politics in Republican Rome (2017)

Russell, The Politics of Public Space in Republican Rome (2015)

Roman magistracies

Brennan Praetorship in the Republic (2000)

Beck, Duplá, jehnem Pina Polo (eds), Consuls and Res Publica: Holding High Office in the Roman Republic (2011)

Pina Polo, Quaestorship, Quaesorship in the Roman Republic (2019)

Wilson, Dictator: Evolutionof the Roman Dictatorship (2021)

Roman Religion/Religion and Politics

Beard, North and Price, Religions of Rome v. 1 and v. 2

Orlin, Temples, Religion and Politics

Rosenstein, Imperatores Victi

Gruen, Studies in Greek Culture and Roman Policy (various chapters on Magna Mater an Bacchanalia)

Stek, Cult Places and Cultural Change in Republican Italy

Beard, Roman Triumph (??)

Pedilla Peralta, Divine Institutions: Religions and Community in the Middle Republic (2020)

J. Mackay, Belief and Cult: Rethinking Roman Religion (2022)

Glinister, “Reconsidering ‘Religious Romanization’” YClS 33 (2006) 10-33

Diluzio, A Place at the Altar (2017) [on priestesses]

Middle Republic: Second Century/Lead-up to the Gracchi

Hopkins, Conquerors and Slaves (1981), esp. pp. 1-95

Rosenstein, Rome at War (2004)

Cornell, Hannibal’s Legacy: the effect of the Hannibal War on Italy, in Cornell/Rankov/Sabin, Second Punic War: a Reappraisal (1996)

Stockton, the Gracchi (1979) [older, “standard” treatment]

Earl, Tiberius Gracchus a Study in Politics (1963) [another old one; consult some of the reviews, e.g Brunt in Gnomon, Scullard in JRS, Crake in Phoenix)

Toynbee, Hannibal’s Legacy: the Hannibalic War’s Effects of Roman Life (1965) [very long; minimally understand the arguments and read reviews]

Brunt, Roman Manpower 225BC-AD14 (1971, republ. 1987) [very long]

There is a fair amount of archaeological work on second-century BC Italy.

Roman Italy, Romanization, Roman conquest of Italy:

Keay/Terrenato, Italy and the West (2001), just part 1 on the republic

Dench, From barbarians to new men: Greek, Roman, and modern perceptions of peoples from the central Apennines (1995)

Lomas, Rome and the Western Greeks (1993)

Bradley, Ancient Umbria: Stated Culture and Identity (2001)

Terrenato, Romanization of Italy: Global Acculturation or Cultural Bricolage, in Theoretical Roman Archaeology (1997) 20-27

Terrenato, Tam Firmum Municipium: the Romanization of Volaterrae and its Cultural Implications, JRS 88 (1998) 94-114

Terrenato, Early Roman Expansion into Italy (2019) [listed above]

Fronda, Between Rome and Carthage (2010) (intro section only)

Roselaar (ed), Processes of Integration and Identity Formation in the Roman Republic (2012) [lots of great chapters, especially by Roth, Rosenstein, Roselaar, Lomas, Patterson]

De Giorgi, Cosa and the Colonial Landscape of Colonial Italy (2019)

David, La Romanisation de l’Italie (1994) [= The Roman Conquest of Italy (1996)]

Glinister, “Reconsidering ‘Religious Romanization’” YClS 33 (2006) 10-33

Roth, Styling Romanization (2007)

Salmon, The Making of Roman Italy (1982)

Roman-Italian elite connections

Patterson, “Contact, Cooperation and Conflict in Pre-Social War Italy,” in Roselaar, 215-226

Patterson, “The Relationship of the Italian ruling Classes with Rome,” in Jehne/Pfeilschifter, Herrschaft und Integration? Rom und Italien in republikanischer Zeit (2006) 139-153.

Terrenato, "Tam firmum municipium: the Romanization of Volaterrae and its cultural implication" JRS 99 (1998) 94-114.

Wiseman, New Men in the Roman Senate

Late Republic: the Italian Question and the Social War

Brunt, “Italian Aims at the Time of the Social War,” JRS 55 (1965) 90-109

Dart, The 'Italian Constitution' in the Social War: A Reassessment (91 to 88 BCE) Historia 58 (2009), 215-224

Pobjoy, “The First Italia,” in Herring and Lomas, The Emergence of State Identities in Italy 187-211

Mouritsen, Italian Unification (1998)

Keaveney, Rome and the Unification of Italy, 2nd ed. (2005)

Howarth, Rome, the Italians, and the Land, Historia 48 (1999) 282-300

Nagle, “An Allied View of the Social War,” AJA 77 (1973) 367-78

Dart, The Social War, 91 to 88 BCE: A History of the Italian Insurgency against the Roman Republic (2014)

Late Republic: From Sulla to the Fall of Republic

Gruen, Last Generation of the Roman Republic, revised (1995) plus read reviews since this was not well received.

Piacentin, Financial Penalties in the Roman Republic (2022)

Taylor, Party Politics in the Age of Caesar (outdated: find reviews to understand the main arguments)

Morstein-Marx, Mass Oratory and Political power in the Late Republic (2008)

Rosillo Lopez, Political conversations in Late Republican Rome (2021)

Rosenblitt, Rome after Sulla (2019)

Pina Polo, The triumviral period: civil war, political crisis and socioeconomic transformations (2020)

Lintott, Violence in Republican Rome (1999)

Kelly, A History of Exile in the Roman Republic (2006)

Riggsby, Crime and Community in Ciceronian Rome (1999)

Augustus’ ‘Revolution’

Syme, Roman Revolution (1939) (a classic)

Raflaub/Toher (eds), Between Republic and Empire (1993)* [edited volume, excellent introductory chapter by Galsterer, plus other good historical chapters: Meier, Eder, Luce, Gruen]

Zanker, Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (1990)* (another classic)

Roman Military

Pfeilschifter, “The allies in the Republican army and the Romanization of Italy,” in Roth and Keller, Roman by Integration: Dimensions of Group Identity in Material Culture and Text (2007) 27-42

Jessica Clark. Triumph in Defeat: Military Loss and the Roman Republic. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2014

Rosenstein, Imperatores Victi: Military Defeat and Aristocratic Competition in the Middle and Late Republic (1990)

Keppie, Making of the Roman Army: from Republic to Empire (1998) [survey introduction]

Goldsworthy, Roman Army at War 100BC-AD 200 (1998)

Armstrong and Fronda (eds), Romans at War: Soldiers, Citizens and Society in Republican Rome (2020)

Daly, Cannae: Experience of battle in the Second Punic War (2003)

Slavery and Captives (starter bibliography)

Hopkins, Conquerers and Slaves (1981)

S. Joshel, Slavery in the Roman World (2010)

K. Bradley, Slavery and Rebellion in the Roman World, 140-70BC (1989)

K. Bradley, Slaves and masters in the Roman empire. A study in social control (1989)

K. Bradley, Slavery and society at Rome (1994)

K. Huemoeller, “Captivity for all ?: slave status and prisoners of war in the Roman Republic,” TAPA 115 (2021)

Henige, “He came, He Saw, We counted: the Historiography and Demography of Caesar's Gallic Numbers,” Annales de démographie historique (1998)

Lowe, "Prisoners, Guards, and Chains in Plautus, Captivi" AJP (1991)

Marshall, The Stagecraft and Performance of Roman Comedy (2006)

Richlin, Slave Theater in the Roman Republic (2017)

Scheidel, "Human Mobility in Roman Italy II: the Slave Population,” JRS (2005)

Scheidel and Harper, "Roman Slavery and the Idea of Slave Society" in Lenski/Cameron (eds) What Is a Slave Society (2018)

Scheidel, "The Roman Slave Supply" in Bradley/Cartledge (eds) Cambridge World History of Slavery (2011)

Thalmann, "Versions of Slavery in the Captivi of Plautus" Ramus (1996)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

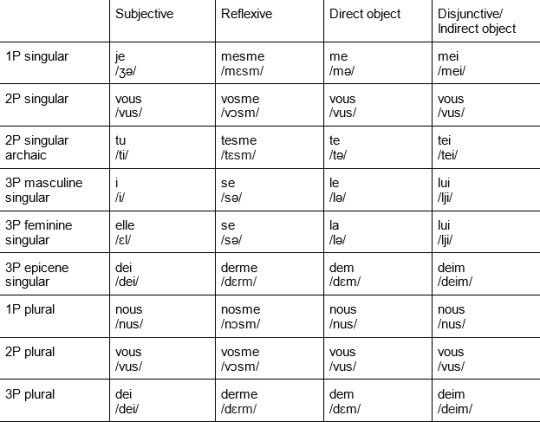

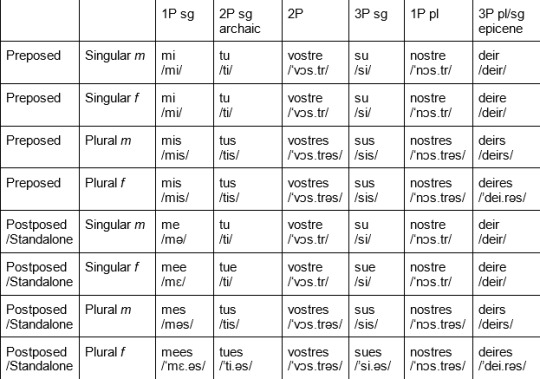

PRONOUNS............

yeah today we'll go over personal pronouns and also possessives

ill just go over whats noteworthy about this

je is the first person singular subjective pronoun; basically english "I". it derives from vulgar latin *eo, from classical latin ego, and is cognate to french je, spanish yo, and italian io

vous is the second person subjective, objective, and disjunctive pronoun. it derives from vōs in latin, but at that time was only a second person plural pronoun, but as in french it also came to be used as a second person singular formal pronoun, and later in angleis's development (late middle angleis, early modern angleis) it became the default second person pronoun, mostly supplanting the now archaic tu

dei is the third person epicene singular and third person plural pronoun, and it was borrowed from old norse þeir during the old angleis period, and it came to supplant the old angleis forms of ils or is and elles

all of the reflexive pronouns other than se are derived from a possessive + mesme, which itself derives from vulgar latin *metipsimus, which ITSELF derives from -met + ipsimus, with mesme meaning "self"

anyways tomorrow i might go over interrogatives or something but i gotta get to sleep for i am employed

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

: • ARTEMIS Braschi: Roman, Imperial Period, Mid-1st c. AD. "The 'Artemis Braschi'... is not a reliable copy but is a new work which borrows from a number of Greek originals... The Roman sculptor cited here the styles of different periods of Greek art and thus consciously produced an antiquated impression: The decoration of the head and the upright body posture with the straight knees are reminiscent of Archaic art of the 6th c. BC. The hair style with the stiff curls falling to the chest recall works of the late Archaic - early Classical period. The head itself with its slight incline to the right is similar to depictions of the 5th c. BC. Similar motifs of light robes with many folds flowing in the wind and simultaneously pressed on the body by a gust are to be found in Classical sculptures of about 400 BC. They suggest that the goddess is floating down from on high." [©AGM] . Antikensammlungen Glyptothek Munich | AGM Room of Apollo www.antike-am-koenigsplatz.mwn.de/index.php/en @antikensammlungenglyptothek . AGM | Phs©MSP 08|22 6200X4100 600 The photographed object is the property of AGM and subject to the Museum copyright. All labels & descriptions txt ©AGM. [no commercial use | sorry for the watermarks] . • Part of the "Reliefs-Friezes-Slabs-Sculpture" MSP Online Gallery: . • D-ART: https://www.deviantart.com/svetbird1234/gallery/72510770/reliefs-friezes-slabs-sculpture . . #munich #antikensammlungenmünchen #glyptothek #archaeologicalmuseum #artmuseum #ancientart #ancientsculpture #arthistory #antiquity #archaeology #museology #mythology #greekmythology #ancient #roman #sculpture #statue #artemis #άρτεμις #artemide #artemida #braschi #goddess #greekgoddess #archaeologyart #museum #sculpturephotography #museumphotography #archaeologyphotography #michaelsvetbird AGM @antikensammlungenglyptothek 08|22 ©msp @michael_svetbird (at Staatliche Antikensammlungen) https://www.instagram.com/p/CnMOerMIPvH/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#munich#antikensammlungenmünchen#glyptothek#archaeologicalmuseum#artmuseum#ancientart#ancientsculpture#arthistory#antiquity#archaeology#museology#mythology#greekmythology#ancient#roman#sculpture#statue#artemis#άρτεμις#artemide#artemida#braschi#goddess#greekgoddess#archaeologyart#museum#sculpturephotography#museumphotography#archaeologyphotography#michaelsvetbird

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greek mythology part 1

Ancient Greece was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (c. 600 AD), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically related city-states and other territories. Most of these regions were officially unified only once, for 13 years, under Alexander the Great's empire from 336 to 323 BC. In Western history, the era of classical antiquity was immediately followed by the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine period.

Classical Greek culture, especially philosophy, had a powerful influence on ancient Rome, which carried a version of it throughout the Mediterranean and much of Europe. For this reason, Classical Greece is generally considered the cradle of Western civilization, the seminal culture from which the modern West derives many of its founding archetypes and ideas in politics, philosophy, science, and art.

Chronology

For a chronological guide, see Timeline of ancient Greece.

Classical antiquity in the Mediterranean region is commonly considered to have begun in the 8th century BC (around the time of the earliest recorded poetry of Homer) and ended in the 6th century AD.

Classical antiquity in Greece was preceded by the Greek Dark Ages (c. 1200 – c. 800 BC), archaeologically characterised by the protogeometric and geometric styles of designs on pottery. Following the Dark Ages was the Archaic Period, beginning around the 8th century BC, which saw early developments in Greek culture and society leading to the Classical Period from the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC until the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC.

Following the Classical period was the Hellenistic period (323–146 BC), during which Greek culture and power expanded into the Near and Middle East from the death of Alexander until the Roman conquest. Roman Greece is usually counted from the Roman victory over the Corinthians at the Battle of Corinth in 146 BC to the establishment of Byzantium by Constantine as the capital of the Roman Empire in 330 AD. Finally, Late Antiquity refers to the period of Christianization during the later 4th to early 6th centuries AD, consummated by the closure of the Academy of Athens by Justinian I in 529.

Classical Greece

In 499 BC, the Ionian city states under Persian rule rebelled against their Persian-supported tyrant rulers. Supported by troops sent from Athens and Eretria, they advanced as far as Sardis and burnt the city before being driven back by a Persian counterattack. The revolt continued until 494, when the rebelling Ionians were defeated. Darius did not forget that Athens had assisted the Ionian revolt, and in 490 he assembled an armada to retaliate. Though heavily outnumbered, the Athenians—supported by their Plataean allies—defeated the Persian hordes at the Battle of Marathon, and the Persian fleet turned tail.

As the Athenian fight against the Persian empire waned, conflict grew between Athens and Sparta. Suspicious of the increasing Athenian power funded by the Delian League, Sparta offered aid to reluctant members of the League to rebel against Athenian domination. These tensions were exacerbated in 462 BC when Athens sent a force to aid Sparta in overcoming a helot revolt, but this aid was rejected by the Spartans. In the 450s, Athens took control of Boeotia, and won victories over Aegina and Corinth. However, Athens failed to win a decisive victory, and in 447 lost Boeotia again. Athens and Sparta signed the Thirty Years' Peace in the winter of 446/5, ending the conflict.

The first half of the fourth century saw the major Greek states attempt to dominate the mainland; none were successful, and their resulting weakness led to a power vacuum which would eventually be filled by Macedon under Philip II and then Alexander the Great. In the immediate aftermath of the Peloponnesian war, Sparta attempted to extend their own power, leading Argos, Athens, Corinth, and Thebes to join against them. Aiming to prevent any single Greek state gaining the dominance that would allow it to challenge Persia, the Persian king initially joined the alliance against Sparta, before imposing the Peace of Antalcidas ("King's Peace") which restored Persia's control over the Anatolian Greeks.

The power vacuum in Greece after the Battle of Mantinea was filled by Macedon, under Philip II. In 338 BC, he defeated a Greek alliance at the Battle of Chaeronea, and subsequently formed the League of Corinth. Philip planned to lead the League to invade Persia, but was murdered in 336 BC. His son Alexander the Great was left to fulfil his father's ambitions. After campaigns against Macedon's western and northern enemies, and those Greek states that had broken from the League of Corinth following the death of Philip, Alexander began his campaign against Persia in 334 BC. He conquered Persia, defeating Darius III at the Battle of Issus in 333 BC, and after the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC proclaimed himself king of Asia. From 329 BC he led expeditions to Bactria and then India; further plans to invade Arabia and North Africa were halted by his death in 323 BC.

0 notes

Text

Character Research: Medusa in History

To help me get an in depth understanding of Medusa as a historical character, I found this article which has been really helpful in giving me the key parts of her appearance and character. What I found the most interesting is how the portrayal of Medusa changes from the Archaic to the Classical period in Greece. The image below on the left is from 570 BCE and show Medusa as monster with some human features whilst the image on the right is from the late 4th - early 3rd BCE and is much more human like and aesthetically pleasing. I think it would be interesting to combine these two portrayals by taking the elements I like the most out of both. This would be the fangs and big eyes from the early depiction and the wings and more defined hair from the later depiction.

0 notes

Photo

A GREEK BRONZE ILLYRIAN HELMET

LATE ARCHAIC PERIOD TO EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD, CIRCA 500-420 B.C.

10 3⁄4 in. (27.3 cm.) high.

#A GREEK BRONZE ILLYRIAN HELMET#LATE ARCHAIC PERIOD TO EARLY CLASSICAL PERIOD CIRCA 500-420 B.C.#archeology#archeolgst#bronze#ancient bring helmet#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#greek war lords

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Aegean - Art History Notes

Original post link / Original post date: October 2 2023

Timeline:

3000-2000 BCE – [Aegean] – Early Cycladic Art

2000-1700 BCE – [Aegean] – Old Palace Period (Crete)

1700-1400 BCE – [Aegean] – New Palace Period (Crete)

1400-1200 BCE – [Aegean] – Mycenaean occupation of Crete

900-600 BCE – [Greece] – Geometric & Orientalizing

600-480 BCE – [Greece] – Archaic

480-400 BCE – [Greece] – Early & High Classical

400-323 BCE – [Greece] – Late Classical

323-30 BCE – [Greece] – Hellenistic

Vocabulary:

Cycladic – of the islands of the Aegean Sea, including Syros, Paros, Delos, Naxos, Keros, Melos, and Thera. This excludes Crete.

Minoan – art of the island of Crete.

Helladic – of the mainland of Greek.

Early Cycladic Art – 2600-2300 BCE

Cycladic Art is titled as such for the Cyclades in the Aegean Sea, which includes Syros, Paros, Delos, Naxos, Keros, Melos, and Thera, among other islands. They are named the Cyclades as the other islands seem to circle around Delos. This excludes Crete. Marble was found in the Aegean islands, which gave way to the beginnings of marble statues in Ancient Greece. The Cycladic art that we still have now consists of marble statuettes, which have a distinctive abstract style to them. Two of these art pieces are the Syros Woman and Keros Musician, both of which follow a similar style of great abstraction of the human form.

Minoan Art – Crete – 1700-1500 BCE

In this period, Cretan art is referred to as Minoan Art. There are two periods of Minoan art: Old Palace and New Palace. The “Palace” in question were large structures, of multiple rooms, on the island of Crete. These were most likely centers for religion, administration, and commercial works as opposed to residents for royalty- though, we are not sure. In cases like this, we have more evidence for one idea than another, so the one with more evidence is used more. The Old Palace period ended abruptly at 1700 BCE, most likely from an earthquake, which lead into the New Palace period as reconstruction immediately began. The largest palace complexes were at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, Kato Zakro, and Khania. These were where Minoan life took place.

The largest of these palaces was at Knossos, where it was named to be the home of King Minos, labeling this palace as the home of the labyrinth of the Minotaur. It should be noted that this was given to the palace as a story as opposed to this myth happening. The English word labyrinth, however, comes from this type of floor plan used in this palace, with the intricate planning and scores of rooms. This layout, a “double ax” labrys, is reoccurring in Minoan architecture and art, representing a sacrificial slaughter. Many Greek myths were taken down generations orally and many of these stories pointed to the glory days of the times evermore ancient to the ancient Greeks; this myth is probably connected to the Minoans and their palaces while remaining a myth.

These palaces were constructed very well, made of sturdy stones embedded in clay, while sporting multiple stories. As true with most Mediterranean areas surrounded by water, Crete is mountainous and rocky, so these palaces accommodated building on top of this with multiple stories that made up for the depth of the slope. Meaning, there were parts of these palaces that were four-to-five stories tall. These palaces hosted drain systems for rain water, ventilation areas to fresh air, columns to hold the weight of the structure, and light wells to bring in natural light. Their columns were notably different than Greek or Egyptian columns of the time as they tapered from top to bottom, wide to narrower. The top was wide while the base was narrower.

Frescos were used to decorate these palaces, featuring nature paintings and aspects of Minoan life. These were achieved differently than Egyptian frescos, which was fresco secco, as the Minoan frescos were the first true buon fresco. To achieve this, they covered the rougher walls in white, fine lime plaster and painted onto the plaster as it was still wet. This means that the painting became a part of the wall, but the painters had a shorter amount of time to achieve the paintings. These paintings do not follow a strict canon, as the Egyptians did, but instead featured a very lively depiction of Minoan life with a freshness in the artworks.

Cycladic Art – 1600 BCE

Other frescos have been discovered, notably on the island of Thera, in Akrotiri, in the Cyclades. These were preserved by a volcanic eruption, with the area being buried in volcanic ash and pumice, similarly to how Pompeii was preserved. These frescos, as opposed to a palace/complex, decorated the walls of shrines and houses, making their number greater. These give us a better insight to how they once could have looked and their full compositions.

Minoan Art – 1800-1500 BCE

Minoan art also featured pottery which depicted nature, particularly the sea and its creatures. These pottery pieces were the first breaths of the style that the Greeks would adopt, morphing into red-figure and black-figure pottery. The Minoans did not have life-size statues or depictions of people or pieces of mythos, having a few smaller pieces remaining. We do not know of any mythos before the Ancient Greeks. A notable art piece is the Harvesters Vase, featuring relief sculptures, while being one of the first evidences of this area of the Mediterranean having an interest in the human body and further anatomy. It’s not well known when the full decline happened of the Minoan society, but we do know that the palaces were destroyed around 1200 BCE, with the Mycenaeans occupying the area before then. The cultural significance of these palaces faded around 1400 BCE.

Mycenaeans – 1600-1200 BCE

The Mycenaeans came to the Greek mainland at about 2000 BCE, being known as warriors who might have brought their wealth from the spoils of their victories. After Cretan palaces were destroyed, the Mycenaeans were left being the surviving Greek civilization. Mycenaean is the label placed on these people, but their fortifications were found at Mycenae, Tiryns, Orchomenos, Pylos, and other areas of Greece. These people became the silent subject of Greek mythos, as their fortifications were explained by later Greeks as being made by giants. The elite in this society were buried in bee-hive shaped tombs. The burial chamber, known as a tholos, consisted of a serious of stone, corbeled courses, laid on a circular base to form a dome. They created masks and daggers for their burials. They also produced one of the only life-size sculptures of this time on the Greek mainland. They had a distinctive illustration style on their pottery, separated from the Minoans.

———

This was a way to force me to write down notes about the greater ancient Greek world. So hopefully this was a nice little overview of the world before the Greeks.

I hope you enjoyed this little overview; make sure to make time for yourself today and drink some water-

Happy travels – Annie, the crosseyed cricket.

#art#art history#greek art#aegean art#ancient greece#ancient greek art#ancient aegean art#art education#art academia#academia#dark academia#greek

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

“While some traces of evidence suggesting Aphrodite’s link with militarism do indeed surface in her ancient Greek cultic, artistic and literary appearances, needless to say, these clues tend to be ambiguous and even contradictory, and thus prone to academic speculation, debate and controversy. Questions regarding her martial character focus on whether Aphrodite herself is portrayed as a warrior engaged in active combat or whether she serves as an inspiration for other fighters or possibly leads them into battle; also, it is a challenge to identify the probable origins or underlying source for these warlike aspects in her divine character. Some scholars believe that Aphrodite’s martial persona, if indeed she has one, is most likely a remnant of the early or lingering influence on her origins of the Near Eastern goddesses associated with both sexuality and warfare, such as Ishtar (Flemberg 1991); later, according to these scholars, Aphrodite was “stripped” of this militaristic component and became solely a goddess of love. Still other scholars argue that Aphrodite’s associations with militarism emerge directly out of her developed Greek persona as the goddess of violent sexuality who presides over the clashing together of bodies in erotic mixis (Pironti 2007). Thus, just as problems abound in determining Aphrodite’s geographic, ethnic and chronological origins, it is no easy task to establish an ultimate derivation for any martial attributes apparent in her character.

Some evidence points to possible militaristic elements in Aphrodite’s cults and shrines, though most of these attestations are rather late (most recently, with thorough survey of data and scholarship: Budin 2009). For example, the travel writer Pausanias, working in the second century ad, mentions three times the existence of “armed” (hoplismene¯) Aphrodite statues in Greece: at Cythera (Description of Greece 3.23.1), Corinth (2.5.1) and Sparta (3.15.10). While Pausanias follows Herodotus (The Histories 1.105) in asserting that Cythera was a major center for the worship of Aphrodite from very early antiquity, he doesn’t provide any more detailed information about the cult statue he simply describes as an armed xoanon or wooden statue of the goddess. At Corinth, which was completely razed by the Romans in 146 bc and rebuilt by Julius Caesar in 44 bc, what Pausanias likely saw was a statue of the Roman goddess and Caesar’s divine forebear, Venus Victrix, “She who Conquers,” rather than an image of the Greek Aphrodite.

Of all her early cults, it is most probable that Aphrodite may have manifested a military persona in archaic and classical Sparta. In addition to Pausanias’ report of a xoanon of Aphrodite Hoplismene¯ housed in an ancient temple there (3.15.10), a few Hellenistic epigrams from the third century bc (and later) depict the specifically martial aspect of the Spartan Aphrodite (e.g. Greek Anthology 9.320, 16.176). Even more interesting is Pausanias’ description of another temple in Sparta dedicated to Aphrodite Areia (3.17.5). This cult, supported by independent epigraphical data from the late Archaic period, suggests Aphrodite was worshipped at Sparta as a female Ares, “Areia.” But it is not clear whether Aphrodite Areia herself bore arms as a warrior or was revered in a joint cult with her more warlike paramour, Ares. Such joint cults of Aphrodite and Ares are found elsewhere in Greece and Crete, yet nowhere in these cults does Aphrodite display a distinctly martial aspect. Indeed, scholars note that the joint cults of Aphrodite and Ares most likely celebrate the gods as conflicting yet connected forces, love and war, linked by the notion of mixis, the intensely physical merging of bodies (Pirenne-Delforge 1994; Pironti 2007). Aphrodite engages in war to the extent that the divine lovers perform mixis in their mythological and cultic appearances.

Thus, a handful of evidence suggests Aphrodite may have had some militaristic aspects to her persona at a few early sites in Greece: for example, the description of her sacred statues as “armed” or her cult at Sparta as “Areia.” And while we grant that some ancient Greeks may have recognized warlike elements in Aphrodite’s divine nature, it seems that her military attributes, if any, were eventually downplayed when she emerged as a fully developed Olympian goddess. In book 5 of the Iliad, Zeus tells her “war isn’t your specialty,” but we have also seen that Aphrodite doesn’t avoid the battlefield. Yet whatever hints of the warrior Aphrodite may surface in the ancient archaeological and literary records, most scholars agree that the image of a militaristic Aphrodite does not represent the prevailing or traditional Greek portrayal of the great goddess of love and sexuality.”

- Monica S. Cyrino, Aphrodite

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

happy valentine's day! have a classical lit guide chapter on sappho.

sappho was a lyric poet of the archaic period (late seventh to early sixth centuries bce), whose poetry survives almost exclusively as fragments. many of these poems feature descriptions of love for women; her name and the name of the island from which she came are the source of the modern terms "sapphic" and "lesbian" respectively.

this chapter's themes are love, gender, and loss. the passages are the ode to aphrodite (fr. 1), a fragment abt triangular desire (fr. 31), and one featuring violets, my fav recurring image in sappho (fr. 94).

i prob don’t have to work too hard to promote sappho (tbh i felt a little weird even trying to introduce her), so instead i’ll mention that i come off as an insane anne carson fangirl in this chapter (and i mean, i am, but i usually try to seem more chill abt it).

(previous chapters: homer’s iliad | aeschylus’ agamemnon | vergil’s aeneid | cicero’s against catiline | seneca’s apocolocyntosis | ovid's heroides)

#this thing is nearly 30k words now which is wild#that's like. more than twice as long as my thesis.#classics#greek#classical lit for fandom purposes#mea res

0 notes