#My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary

Text

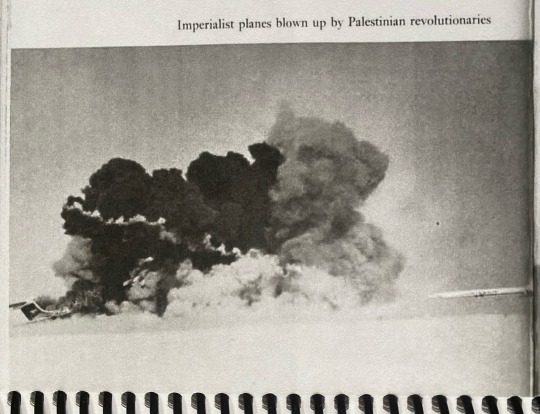

I do not see how my oppressor could sit in judgment on my response to his oppressive actions against me. He is in no position to render an impartial judgment or to accuse me of air piracy and hijacking when he has hijacked my home and hijacked me and my people out of our land. If the enemy defines morality and legality in his own terms and decides to apply his ethical and legal

doctrines against me because he has the power as well as the means of communications to justify his inhumanity, I am under no moral obligation to listen, let alone obey his dictates. Indeed, I am under a moral obligation to resist and to fight to death the enemy's moral corruption. My deed cannot be evaluated without examining the underlying causes. The revolutionary deed I carried out on August 29, 1969 was an assertion of my spurned humanity, a declaration of the humanity of Palestinians. It was an act of protest against the West for its pro-Zionist (therefore anti-Palestinian) posture. The list of the sins of the West is overwhelming.

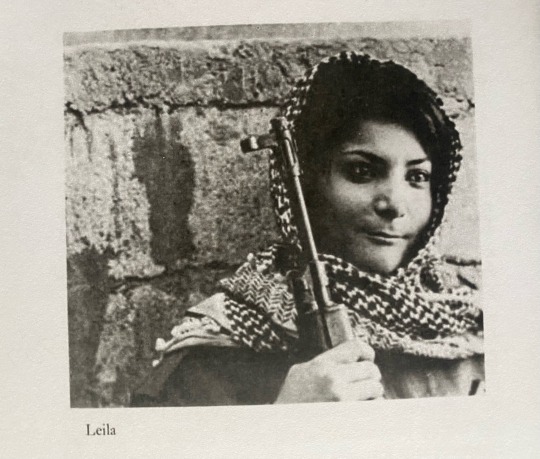

—Leila Khaled, My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary ed. George Hajjar

#august incident refers to her hijacking#leila khaled#my people shall live#My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary#george hajjar#palestine#mine#words#2024 reads

951 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day in 1944, Leila Khaled, Palestinian revolutionary, was born in Haifa.

If you have time today, you should read her autobiography from 1973: My People Shall Live. Here’s a free PDF.

Via @ayaghanameh

802 notes

·

View notes

Text

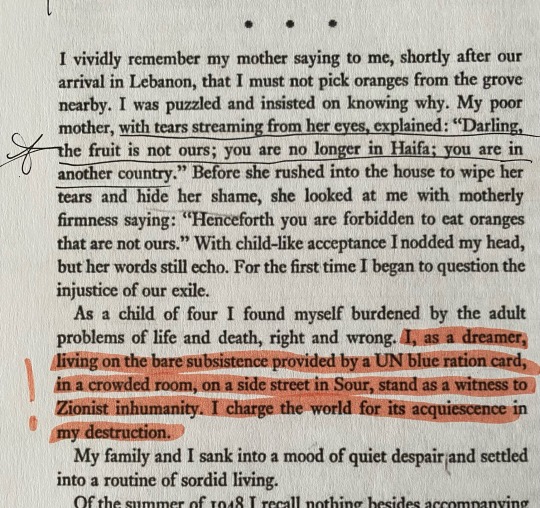

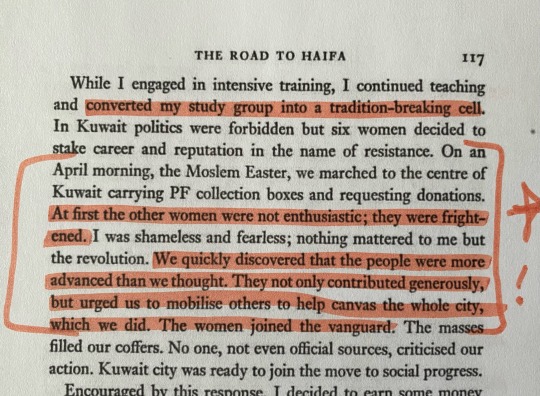

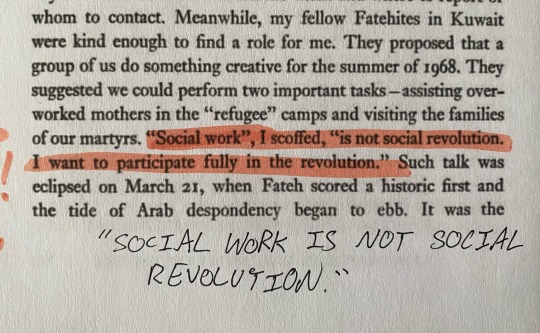

just finished reading My People Shall Live, the autobiography of Palestinian revolutionary Leila Khaled. here are some scenes,,

#free palestine#leila khaled#autobiography#books and reading#revolution#anti colonialism#anti zionisim#read in 2022#communism

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Podcast reading w/ free PDF📚: My People Shall Be Free~An Autobiography of A Revolutionary by Leila Khaled

My People Shall Live~An Autobiography of A Revolutionary:

A profound journey into the heart of Palestinian resistance, through the words of an icon who has lived it. In this distinguished episode of *Echoes of Revolution*, we delve into the autobiography "My People Shall Live~An Autobiography of A Revolutionary" by Leila Khaled, a name synonymous with resilience, defiance, and the relentless quest for freedom.

Leila Khaled's narrative is not just a personal recounting; it's a mosaic of struggle, hope, and the unyielding spirit of a people yearning for their rightful place in the world. Her story, penned with raw honesty and unwavering conviction, brings to light the intricacies of the Palestinian struggle for liberation, seen through the eyes of a woman who became an emblem of revolutionary fervor.

As we navigate through the chapters, our podcast aims to encapsulate the essence of Khaled's journey—from her early years in a Palestine under the shadow of displacement to her evolution into a key figure in the global struggle against oppression. Her acts of defiance, notably as the first woman to hijack an airplane, are not merely recounted as historical events but analyzed for their symbolic significance in the broader narrative of resistance.

Read PDF:

Here🔗

Listen:

Spotify🔗

YouTube🔗

Follow Hosts on Twitter:

@shesunruly

@the_penandpaper

Read, Listen, Like and Share!!

#Pan african#palenstine#pflp#leila khaled#revolutionary#imperialism#colonialism#genocide#revolution#resistance#resistance fighters#pdf#books#podcast#spotify#youtube#twitter

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE BOOKS I READ IN 2023

*I read it before

**I read it more than once this year

Aaron Caycedo-Kimura, Common Grace

Adania Shibli, Minor Detail, translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette

Ahmad Almallah, Bitter English

Alison Lubar, It Skips a Generation

Atef Abu Saif, The Drone Eats With Me: A Gaza Diary

Brynn Saito, Under a Future Sky

Camonghne Felix, Dyscalculia: A Love Story of Epic Miscalculation

*Carolina Ebeid, You Ask Me to Talk About the Interior

Chanté L. Reid, Thot

*Christina Sharpe, Ordinary Notes

Christine Shan Shan Hou & Vi Khi Nao, Evolution of the Bullet

Christopher Okigbo, Labyrinths (with Paths of Thunder)

Cristina Rivera Garza, Liliana’s Invincible Summer

Dionne Brand, Chronicles of the Hostile Sun

*Dionne Brand, No Language is Neutral

Dionne Brand, Primitive Offensive

Édouard Louis, Who Killed My Father, translated from the French by Lorin Stein

**Emily Lee Luan, 回 / Return

Erin Marie Lynch, Removal Acts

Fady Joudah, Footnotes in the Order of Disappearance

Farid Tali, Prosopopoeia, translated from the French by Aditi Machado

Gabriel Palacios, A Ten Peso Burial For Which Truth Is Sign (coming out 2024)

Ghayath Almadhoun, Adrenalin, translated from the Arabic by Catherine Cobham

Hauntie, To Whitey & The Cracker Jack

Hervé Guibert, To the friend who did not save my life, translated from the French by Linda Coverdale

Hiromi Ito, Tree Spirits Grass Spirits, translated from the Japanese by Jon L. Pitt

*James Baldwin, No Name in the Street

*James Baldwin, Nobody Knows My Name

*James Baldwin, The Devil Finds Work

James Fujinami Moore, Indecent Hours

Jami Nakamura Lin, The Night Parade

Jawdat Fakhreddine, Lighthouse for the Drowning, translated from the Arabic by Huda Fakhreddine and Jayson Iwen

Jed Munson, Commentary on the Birds

Jennifer Hayashida, A Machine Wrote This Song

Jenny Odell, Inhabiting The Negative Space

Jenny Xie, The Rupture Tense

*Joy Kogawa, A Choice of Dreams

Joy Kogawa, A Garden of Anchors: Selected Poems

**Joy Kogawa, From the Lost and Found Department: New and Selected Poems

Joy Kogawa, Gently to Nagasaki

*Joy Kogawa, Jericho Road

*Joy Kogawa, Obasan

Joy Kogawa, The Rain Ascends

Joy Kogawa, The Splintered Moon

*Joy Kogawa, Woman in the Woods

Juan Felipe Herrera, Akrílica, eds. Farid Matuk, Carmen Giménez, Anthony Cody

Kamo-no-Chomei, Hojoki: Visions of a Torn World, translated from the Japanese by Yasuhiko Moriguchi and David Jenkins

Keorapetse Kgositsile, Collected Poems, 1969-2018

*Kiku Hughes, Displacement

Kōno Taeko, Toddler-Hunting, translated from the Japanese by Lucy North

Leila Khaled, My People Shall Live: Autobiography of a Revolutionary, as told to George Hajjar

Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, Kaan and Her Sisters

**Lindsey Webb, Plat (coming out in 2024)

Lisa Hsiao Chen, Activities of Daily Living

Liyana Badr, A Balcony over the Fakihani, translated from the Arabic by Peter Clark with Christopher Tingley

Lucille Clifton, An Ordinary Woman

*Lucille Clifton, Blessing the Boats

Lucille Clifton, Good News About the Earth

Lucille Clifton, Good Times

Lucille Clifton, Two-Headed Woman

Mahmoud Darwish, The Butterfly’s Burden, translated from the Arabic by Fady Joudah

Mahmoud Darwish, If I Were Another, translated from the Arabic by Fady Joudah

Mahmoud Darwish, Palestine as Metaphor, translated from the Arabic by Amira El-Zein and Carolyn Forché

Maya Abu Al-Hayyat, You Can Be The Last Leaf, translated from the Arabic by Fady Joudah

Maya Marshall, All the Blood Involved in Love

Michael Prior, Model Disciple

*Mitsuye Yamada, Camp Notes and Other Poems

Mitsuye Yamada, Full Circle: New and Selected Poems

Mohammed El-Kurd, RIFQA

**Mosab Abu Toha, Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear

Mourid Barghouti, I Saw Ramallah, translated from the Arabic by Ahdaf Soueif

Mourid Barghouti, I Was Born There, I Was Born Here, translated from the Arabic by Humphrey Davies

Mourid Barghouti, Midnight, translated from the Arabic by Radwa Ashour

Na Mira, The Book of Na

Najwan Darwish, Nothing More to Lose, translated from the Arabic by Kareem James Abu-Zeid

Natsume Sōseki, Kokoro, translated from the Japanese by Edwin McClellan

Nona Fernández, Voyager: Constellations of Memory, translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer

Noor Hindi, DEAR GOD. DEAR BONES. DEAR YELLOW.

Osamu Dazai, No Longer Human, translated from the Japanese by Donald Keene

Osamu Dazai, The Flowers of Buffoonery, translated from the Japanese by Sam Bett

The Palestinian Wedding: A Bilingual Anthology of Contemporary Palestinian Resistance Poetry, edited and translated from the Arabic by A.M. Elmessiri

R.F. Kuang, Yellowface

Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Kappa, translated from Japanese by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda and Allison Markin Powell

Salim Barakat, Come, Take a Gentle Stab: Selected Poems, translated from the Arabic by Huda J. Fakhreddine and Jayson Iwen

Samih Al-Qasim, All Faces But Mine, translated from the Arabic by Abdulwahid Lu’lu’a

Samih al-Qasim, Sadder Than Water: New & Selected Poems, translated from the Arabic by Nazih Kassis

*Saretta Morgan, Alt-Nature (coming out in 2024)

Satsuki Ina, The Poet and the Silk Girl (coming out in 2024)

Sawako Ariyoshi, The Twilight Years, translated from the Japanese by Mildred Tahara

Shailja Patel, Migritude

Sham-e-Ali Nayeem, City of Pearls

Sharon Yamato, Moving Walls

Shivanee Ramlochan, Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting

**shō yamagushiku, shima (coming out in 2014)

Shuri Kido, Names and Rivers, translated from the Japanese by Tomoyuki Endo and Forrest Gander

*Solmaz Sharif, Customs

Stella Corso, Green Knife

*Taha Muhammad Ali, Never Mind: Twenty Poems and a Story, translated from the Arabic by Peter Cole, Yahya Hijazi, Gabriel Levin

Terry Watada, The Game of 100 Ghosts (Hyaku Monogatari Kwaidan-kai)

Victoria Chang, Obit

*Wong May, Superstitions

THE BOOKS I'M CURRENTLY READING, THAT I HAVEN'T FINISHED YET

Chi Rainer Bornfree and Ragini Tharoor Srinivasan, The Portal (not yet published)

Elaine Castillo, How to Read Now

Eqbal Ahmad, The Selected Writings

Essays, ed. Dorothea Lasky

Fadwa Tuqan, A Mountainous Journey: A Poet's Autobiography, translated from the Arabic by Olive Kenny

James Welch, Winter in the Blood

Lan P. Duong, Nothing Follows

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, Touching the Art

Preti Taneja, Aftermath

Wanda Coleman, Wicked Enchantment

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

From Netflix to Hitler, protesters are tapping pop culture and history as they vent their anger against Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s new citizenship law — and with deft use of India’s beloved acronyms.

The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) eases naturalisation for persecuted religious minorities from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, but not if they are Muslim.

Critics fear it is the precursor to a National Register of Citizens (NRC) that many among India’s often undocumented 200 million Muslims is aimed primarily of making them stateless.

Modi’s government denies this and says the law is a humanitarian move, but it has sparked two weeks of protests that at times have been violent. At least 27 people have been killed.

“NRC is Coming” reads one placard, co-opting the “Winter is Coming” slogan of the smash-hit fantasy series “Game of Thrones”, with Modi’s black and white mugshot in the background.

Also Read: ‘A clear plan for a Muslim genocide in India’

Others inspired by the same fantasy series include ��Winter is coming for Modi and Shah”, referring to Home Minister Amit Shah, and “Modi – you are making Cersei look good”, a nod to a “Game of Thrones” villain.

“Netflix and raise hell”, says another, in a spin on the expression “Netflix and chill”.

“Stop trying to make NRC happen!” meanwhile rips off a popular line in Lindsay Lohan movie “Mean Girls”.

– ‘Die like Hitler’ –

Anjali Singh, clutching an “Error 404, Hindu nation not found” placard, said that Modi and his government had become more aggressive in moving forward with their Hindu agenda.

“So our messaging has also got more explicit and direct,” Singh told AFP.

Slogans like “Long Live the Revolution”, a popular chant of India’s independence struggle against British, echo at many demos, with a rhyming chant of “If you act like Hitler, you will die like Hitler”.

Caricatures of Modi and Shah wearing Nazi uniform and posters of Hitler holding a baby-sized Modi aloft have become a staple as videos and pictures that are viral on social media, as well as of graffiti.

“Everything that happens offline ends up online and we have to have a global appeal in our messaging,” Kiran Malhotra, a student protester in New Delhi, explained to AFP.

Also Read: ‘Wake up before RSS commits genocide of Muslims,’ PM Imran forewarns

“Someone sitting in the US or Europe will not understand the change in India’s citizenship law but comparing Modi with Hitler simplifies it,” Malhotra said, her placard depicting a cartoon Modi with a swastika armband.

Many protesters are also rehashing Indian TV jingles from the 1980s to give a nostalgic touch to the protests, while others are using tambourine beats to sing “Down with Modi” or recite the preamble of India’s constitution.

Other favourites include a Hindi version of US civil rights anthem “We shall overcome”, as well as revolutionary Urdu poems.

“The messaging has to be more explicit and direct now,” Ira Sen, a protester told AFP.

Her poster features independence icon Mahatma Gandhi holding his “My experiments with Truth” autobiography alongside Modi cradling what the drawing depicts as his version, “My experiments with lies”.

– Homs to Hyderabad –

Many people are demonstrating for the first time, drawing inspiration from protests in Hong Kong, Chile, the Arab Spring and against US President Donald Trump’s travel ban on people from six Muslim-majority countries.

“People power can bring change. Democracy and constitution will win, despots will be thrown out,” Meenkshi Roy, an interior designer told AFP, holding a placard “Caesar will go… Rome stays”.

Other placards are topical (“PM 2.0 is worse than PM2.5”, a reference to a measure of pollution in India‘s smog-choked cities) and witty (“I have seen smarter cabinets at IKEA”).

“There is more youthful but aggressive language in slogans and placards. Some of the placards are downright offensive, some mocking and many other are sarcastic,” Steve Rocha, an activist, told AFP.

“This protest has everything –- graphics, words, music, poetry and rage.”

The post Graphics, music, and poetry: protesting Indians get creative to vent anger against Modi appeared first on ARY NEWS.

https://ift.tt/2Qmh9El

0 notes

Text

Frederick Douglass Narratives

I am finding difficult to organize my thoughts and write an adequate response to the narrative of Frederick Douglass. I believe this may be the case because Frederick Douglass wrote on a great number of subjects during the course of his autobiography, which included the mistreatment of both his person and his fellow slaves, as well as the plight of the African-American people during Pre-Civil War America. Given the amount of detail that is awarded to different portions of his life, as well as different ideas, I am finding it hard to determine what would be best for me address during the course of this post.

With that being said, I feel as though I should address a few of the reasons why Frederick Douglass remains a “representative” of the African-American individuals who lived during his lifetime. The initial reason I shall provide surrounds the fact that Frederick Douglass dispelled the wide-held beliefs of several ignorant, (mostly white), Americans who thought that the treatment of slaves at the hands of their masters was not as harsh, severe, and unpleasant as it actually was. These ignorant individuals most likely held their incorrect beliefs on account of what they had heard from several forms of propaganda created by the American political system as well as the individuals who were wealthy enough to own slaves. Furthermore, with the same broad stroke, Douglass manages to paint several vivid scenes, which describe the hardships endured by the African-American people during the period of their enslavement. In a way, he manages to speak for all of those individuals who have no voices, either because they were silenced by their oppressors, or kept from learning how to read and write, and thus, from learning how to express themselves and their innermost thoughts in an enduring way. (The spoken word may only survive as long as it is accurately and repeatedly told, while the written word might be copied several times over, passed amongst several different people, and shared over great distances).

Although Douglass himself relates several times during the course of his biography that he was one of the lucky slaves who lived in more “ideal” situations during several periods of his oppression, he also describes how he was one of the more “typical,” unlucky slaves who was forced to endure several hardships, and bear witness to endless degradation. Douglass describes how for a time, he was taught how to read and write, and how he later, had to finish his education by being resourceful. He also relates how most black individuals were not allowed to read and write, which caused widespread illiteracy amongst their ranks. Furthermore, he relates how many slaves were underfed, which led to both emaciation and malnourishment, how several women were raped so that they might produce additional slaves, and how many slaves were beaten so severely that they scarred and bled profusely. In addition, he described how they might have been flogged for even minor infractions- such as walking too slowly, or not picking grain or another crop swiftly enough for their masters.

By relating all of these horrid details of not only his own life, but that of most slaves, Douglass manages to express the many liberties that whites could exact from the African-American community, and how many freedoms were taken away from the African-American community during this time period. He expresses how the [white] people of his own time, as well as future generations, take simple things, such as the ability to walk where they will, for granted. Furthermore, by chronicling the occurrences of his life, Douglass demonstrates how slavery “distorts the soul,” in much the same way that Martin Luther King Jr. claimed that segregation did in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” and how slavery undermines both natural law and virtue ethics.

Slavery, as Frederick Douglass expresses in his narrative, manages to accomplish these numerous feats in several ways. The act of enslaving other individuals who are deemed “less than” oneself lies in direct conflict with virtue ethics, (in which an individual is meant to strive to act within the mean, or upon the good habits known as virtues, in order to be the best person possible). This is due to the fact that slavery often involves beating one’s slaves, in order to teach them lessons, or scare them into being more compliant. Such an act is certainly far from virtuous. Furthermore, racism in and of itself, in which one race views their own as superior to others is not at all virtuous. Nor, as Aristotle described, is being disloyal or untrustworthy a virtue. Traits, which are evidenced repeatedly within the characters of Douglass’ owners, when he describes how Mr. Covey would pretend to leave the plantation and then hide himself in the bushes or behind a tree in order to see if his slaves would act out while his away, etc.

The descriptions made by Douglass in regards to slavery in his narrative also defy natural law. Douglass describes the peculiarity of one man owning another; especially when they are so similar to one another in both appearance and manner. Douglass writes, “he… must stand by and see one white son tie up his brother, of but few shades darker complexion than himself,” (Douglass 208). The thought of owning another individual is rendered all the more unnatural if one were only to consider the occurrences of the wild. In the wild live “untamed beasts,” which are often considered to be “less than” man, and of the basest disposition. Yet, these animals do not own one another; instead, they live amongst one another, in relative harmony by the grace of endless symbiotic relationships.

Although he fails to do so outright, Frederick Douglass describes how unnatural slavery is, while also explicitly stating how cruel the act of slavery is, and how many men and women are reduced to lives worse than the impoverished. He describes maltreatment, malnourishment, and the endless sorrow, which spurs many slaves to try and escape their masters, and seek a life of freedom in the Northern states.

As Douglass himself said, “I have only one life to lose,” (Douglass 224). His words reminded me of Nathan Hale who is most noted for saying, “I regret that I have but only one life to give for my country,” after being captured during the American Revolutionary War. Douglass’ words made me think of Hale, because they clearly expressed how the lives of the majority of slaves were made so poor and so miserable that they would rather die trying to escape their captors, than live under their rule. This is due to the fact that the life of a slave was simply no life at all, and they felt as though they weren’t really losing anything by risking their “lives.” In much the same way, those who partook in the American Revolution felt that their lack of freedom made their lives insufferable, and like many of the slaves later would; they became willing to die for their right to freedom and their own ideas.

A sentiment, which Douglass’ friend Henry shared as he screamed, “shoot me,” (Douglass 241), at his captors, for he simply could not endure the unnatural state of his life any longer.

Outside References:

King, Martin Luther, Jr. “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” Natural Law, Natural Rights, and

American Constitutionalism. The Witherspoon Institute, 2016. Web. 23 May 2016.

Mackinnon, Barbara, and Andrew Fiala. Ethics: Theory and Contemporary Issues. 8th ed.

Stamford: Cengage Learning, 2015. Print.

“The Execution of Nathan Hale, 1776.” EyeWitness to History. Ibis Communications, Inc., n.d.

Web. 23 May 2016.

#frederick douglass#douglass#narrative#literature#memories#african american literature#slavery#mistreatment#hardship#slaves#black#african american#america#civil war#feelings#memory

0 notes

Text

Does anybody know where I can buy the autobiography of Leila Khaled? I tried Google, but I only found it sold out on Amazon

#pls i'm desperate#leila khaled#book#books#My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I come from the city of Haifa, but I remember little of my birthplace. I can see the area where I played as a small child, but of our house, I only remember the staircase. I was taken away when I was four, not to see Haifa again for many years. Finally I saw my city twenty-one years later, on August 29, 1969, when Comrade Salim Issawi and I expropriated an imperialist plane and returned to Palestine to pay homage to our occupied country and to show that we had not abandoned our homeland. Ironically, the Israeli enemy, powerless, escorted us with his French and American planes.

What I knew about Haifa had come from my parents and friends and from books. Now I saw Haifa from the air and formed my own cherished image of my home. Haifa is caressed by the sea, hugged by the mountain, inspired by the open plain. Haifa is a safe anchor for the wayfarer, a beach in the sun. Yet, I, as a citizen of Haifa, am not allowed to bask in its sun, breathe its clear air, live there with my people. European Zionists and their followers are living in Palestine by right of arms and they have expelled us from our homeland. They live where we should be living while we float about, exiled. They live in my city because they are Jews and they have power. My people and I live outside because we are Palestinian Arabs without power. But we, the graduates of the desert inns, we shall have power and we shall recover Palestine and make it a human paradise for Arabs and

Jews and lovers of freedom.

—Leila Khaled, My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary ed. George Hajjar

#leila khaled#My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary#george hajjar#palestine#words#2023 reads#mine#ok so the thing is i got this from someones drive and this feels v much like it was formatted by someone else not the publisher so idk if#the spelling + punctuation mistakes are intentional or not 😭

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Arab people are frequently accused by their opponents and sometimes by their friends of being too emotional. I, as a Palestine Arab woman, have something to be legitimately emotional about: the loss of my home and community and the denial of my present and future. But I am not going to succumb to emotionalism and allow my feelings to blind my reason and undermine my confidence in the capacity of my people to liberate their land. In spite of the power of the enemy, I intend to rely on revolutionary ideology and strategy and mass mobilisation

to achieve our objectives. In my work I have chosen to be the ally of reason, not passion, and my party, the Popular Front, also analyses and reasons before acting.

We do not embark haphazardly on adventurous and romantic individualistic projects to fulfill "individual needs" or "act out of frustrations and hostilities" as Western "scientific" psychologists hypothesise. We act collectively in a planned manner either to neutralise a prospective friend of the enemy or to expose a vital nerve of the enemy and, above all, to dramatise our own plight and to express our resolute determination to alter "the new realities" that Mr. Moshe Dayan's armies have created. Generally, we act not with a view to crippling the enemy because we lack the power to do so-but with a view to disseminating revolutionary propaganda, sowing terror in the heart of the enemy, mobilising our masses, making our cause international, rallying the forces of progress on our side, and underscoring our grievances, before an unresponsive Zionist inspired and Zionistinformed Western public opinion. As a comrade has said: We act heroically in a cowardly world to prove that the enemy is not invincible. We act "violently" in order to blow the wax out of the ears of the deaf Western liberals and to remove the straws that block their vision. We act as revolutionaries to inspire the masses and to trigger off the revolutionary upheaval in an era of counter-revolution. Dr. Habash, the Secretary General of the PFLP, has stated our human dilemma and our ethical view thus:

After 22 years of injustice and inhuman living in camps with nobody caring for us, we feel that we have the very full right to protect our revolution, we have all the right to protect our revolution. Our Code of Morals is Our Revolution. What serves our revolution, what helps our revolution, what protects our revolution is right, is very right and honourable and very noble and very beautiful, because our revolution means justice, means having our homes back, having back our country, which is a very just and noble aim.

—Leila Khaled, My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary ed. George Hajjar

#leila khaled#my people shall live#my people shall live: the autobiography of a revolutionary#george hajjar#palestine#words#mine#2024 reads

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

For fifteen years my family had been exiled from our beloved homeland. Since a state of war existed between the Arab states and Israel, we had not seen a single relative from Haifa or Majdel El Karoum. Travel restrictions were too severe; bureaucratic red tape was overwhelming, and financial considerations were difficult to overcome. However, after prolonged and careful preparations, my father went to see his family in Jerusalem at the Mendelbaum gate. He waited for three days but no one showed up. A few weeks later, a meeting was again arranged, but this time my father was paralyzed and not able to go.

Mother went without him. The meeting was a nightmare of barbed-wire. When grandmother saw mother, she presumed her son must have died and she collapsed. My aunts, my cousins, and mother carried on a teary dialogue for about an hour. Little or nothing was said beyond conveying greetings and fleeting reminiscences. We were all drenched with tears. We looked at each other wondering whether reunion would ever be possible; no one could utter a coherent sentence; we parted infuriated at the Zionist overlord.

As mother said adieu to grandmother, granny placed her necklace around mother's neck and kissed her. An Israeli guard looked on and instantly pounced on mother and snatched the necklace from her chest. Mother fought back but the man with the gun prevailed. She returned home upset by Arab inability to protect her and shocked by Zionist brutality. Such events kept my family and most Palestinians away from the Zionists. Since then, we have not seen our relatives, and father died without having seen his mother and sisters for eighteen years.

—Leila Khaled, My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary ed. George Hajjar

#leila khaled#my people shall live#My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary#george hajjar#palestine#words#2023 reads#mine

38 notes

·

View notes