#Napoleon biography

Text

Descriptions of Napoleon’s personality by Adam Zamoyski

“He was kind by nature, quick to assist and reward. He found comfortable jobs and granted generous pensions to former colleagues, teachers, and servants, even to a guard who had shown sympathy during his incarceration after the fall of Robespierre. He was generous to the son of Marbeuf, promoted his former commander at TouIon Dugommier and looked after his family when he died, did the same for La Poype and du Teil, and even found the useless Carteaux a post with a generous pension. Whenever he encountered hardship or poverty, he disbursed lavishly. He could be sensitive, and there are countless verifiable acts of solicitude and kindness that testify to his genuinely wishing to make people happy.”

“He was most at his ease with children, soldiers, servants, and those close to him, in whom he took a personal interest, asking them about their health, their families, and their troubles. He would treat them with a joshing familiarity, teasing them, calling them scoundrels or nincompoops; whenever he saw his physician, Dr. Jean-Nicolas Corvisart, he would ask him how many people he had killed that day.”

“He possessed considerable charm and only needed to smile for people to melt. He could be a delightful companion when he adopted an attitude of bonhomie. He was a good raconteur, and people loved listening to him speak on some subject that interested him, or tell his ghost stories, for which he would sometimes blow out the candles. He could grow passionate when discussing literature or, more rarely, his feelings.”

#source:#Napoleon: A Life by Adam Zamoyski#napoleon#Adam zamoyski#zamoyski#napoleonic era#napoleonic#Napoleon biography#bio#napoleon bonaparte#Dugommier#du Teil#La Poype#corvisart#Marbeuf#french revolution#frev#la révolution française#révolution française#first french empire#french empire#France#french history#history#19th century

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

there are other ways this sentence could have been written but this is by far the funniest version

#thank you bell#napoleon: a concise biography by david a. bell#napoleonposting#napoleon bonaparte#louis xviii#certifiedhistoryaddict

388 notes

·

View notes

Text

VANESSA KIRBY as EMPRESS JOSEPHINE

Napoleon (2023) dir. Ridley Scott

#napoleon#biography#action#2020s#*#by courtney#filmgifs#moviegifs#filmtv#tvandfilm#tvfilmsource#filmtvdaily#dailytvfilmgifs#cinemapix#cinematv#ladiesofcinema#femaledaily#chewieblog#userbbelcher#userstream

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon (2023) dir. Ridley Scott

#filmedit#perioddramaedit#periodedit#napoleonedit#napoleon#napoleon 2023#gif#liz#2020s#action#adventure#biography

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

A look at three Fouché biographies

Over the past few months I've read three English-language biographies on Fouché: Joseph Fouché: Portrait of a Politician, by Stefan Zweig; Fouché: Unprincipled Patriot, by Hubert Cole; and Medusa's Head: The Rise and Survival of Joseph Fouché, Inventor of the Modern Police State, by Rand Mirante. These are a great example of how dramatically interpretations of a historical figure can vary from one historian to another (see also the difference between Alan Schom's interpretation of Napoleon vs. that of Andrew Roberts). And also a great example of why it’s a good idea to read multiple biographies on the same figure, to gain a more well-rounded perspective, instead of simply accepting/adopting that of the first biographer you read.

Zweig is a colorful writer and his biography is highly entertaining—he actually had me laughing out loud a few times—but his depictions of Fouché are so hilariously sinister and malignant throughout that at times it almost feels like a caricature. Zweig also utilizes the least amount of primary source material out of the three biographers--hardly any, actually--and so much of what he writes in regard to Fouché's motivations and thoughts come across as pure speculation or projection, but are always stated very matter-of-factly. Zweig presents a Fouché who chafes at the smallness of the roles he is given, driven by "unflinching selfishness." "When in power," Zweig writes, "he does not work for the State, does not work for the Directory or for Napoleon, but for himself." Aside from raw ambition, Zweig attributes most of Fouché’s actions to his sheer delight in engaging in intrigue for the sake of intrigue, an interpretation that seems to come straight out of Napoleon’s venting on St. Helena: “Intrigue was to Fouché a necessary of life. He intrigued at all times, in all places, in all ways, and with all persons. Nothing ever came to light, but he was found to have had a hand in it. He made it his sole business to look out for something that he might be meddling with. His mania was to wish to be concerned with everything.” Overall, Zweig’s book is worth reading, but out of the three English-language Fouché biographies, it’d be ranked third on my list.

Hubert Cole’s interpretation of Fouché is as different from Zweig’s as night is from day. The key word in Cole’s title is “Patriot,” and Cole’s central point is that Fouché, at each point in his career, was doing what he believed was in the best interests of France, even if that meant negotiating for peace with Britain behind Napoleon’s back, or pushing Napoleon towards a divorce and remarriage for the sake of shoring up the Bonaparte dynasty, or even (repeatedly) abandoning one master to serve another. This is the second one of Cole’s biographies I’ve read, and as most of you following me already know, I loved his dual biography on Joachim and Caroline Murat, the deceptively named The Betrayers, which is actually a very sympathetic look at the Murat couple. Cole is no fan of Napoleon and doesn’t really attempt to hide it, and maybe it’s because of this that he feels inclined to look deeper at the motivations and actions of those who ended up in opposition to Napoleon at various points (and who have therefore been demonized in history books accordingly). Cole draws heavily on primary sources, from letters and memoirs of Fouché’s contemporaries, to Fouché’s police bulletins (quoted at length throughout) to argue that “It is possible… that he was a sincere and moderately successful patriot. It is not uncommon in France for egoists to be hailed as patriots, and patriots condemned as traitors.” Far from the sinister, cold-blooded figure that haunts Zweig’s biography, or the “universally distrusted, feared, and hated” social pariah of Mirante’s, Cole's Fouché is charming, a welcome figure in the drawing rooms of Paris society, with a preference for making friends rather than enemies; nevertheless Cole does not deny that Fouché could also be ruthless, ambitious, and cunning. Cole also uses numerous accounts regarding Fouché by British, German, and Russian contemporaries, “in the belief that their prejudices, if national, are less personal.” Out of these three biographies, this one was my personal favorite, as I think it provides a more well-rounded picture of Fouché as a human being.

The primary focus of Mirante’s book is Fouché’s administration of the Ministry of Police, and the biography goes into great detail about the operations of the police in Napoleonic France, its vast network of informants, subversion of the press, surveillance of emigrés, and steady stream of information flowing in from all quarters. Fouché emphasized to his subordinates how one small detail or event could be “of great interest in the general order of things by its connections with related matters of which you are scarcely aware.” Like Cole, Mirante quotes frequently from Fouché’s police bulletins, as well as from memoirs of the era (though most of the excerpts are those hostile to Fouché). Unlike Cole, Mirante’s Fouché is driven not by any higher patriotism, but—especially after his humiliating flight from France in 1810—by a deep and abiding hatred of Napoleon, towards whose final destruction Fouché is willing to go to any length. Mirante provides more detail on Fouché’s exile and final years than either Zweig or Cole, one interesting aspect of which is the warm welcome Fouché received in Trieste from Elisa Bonaparte, who had been driven from power in Tuscany largely through Fouché’s machinations with Murat in 1814. Mirante ends the book with a critical look at Fouché’s dubious, ghostwritten “memoirs,” the credibility of which he is far more suspicious than Cole, who accepts the argument of French historian Louis Madelin that they are “largely authentic and accurate.” Mirante, on the other hand, is not convinced, and concludes that the memoirs are “highly assailable, at least quasi-spurious, and shrouded in controversy and deceit.” Mirante ends by drawing parallels between Fouché’s policing methods and those of the Gestapo and NKVD in the 20th century.

Overall I enjoyed all three of these for different reasons, and taken together they offer a more complete picture of Fouché. I haven’t gotten around to reading any French-language biographies on Fouché yet, but I do have a couple works on him by Emmanuel de Waresquiel that are definitely on my to-read list.

#Joseph Fouché#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#Napoleonic#history#19th century#books#biographies#French Revolution

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Napoleon#Napoleon movie#Napoleon 2023#Ridley Scott#Sir Ridley Scott#director#filmmaker#Joaquin Phoenix#biography#war#history#drama#movie#behind the scenes#scene#Making Of#cinema

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

There’s some old posts from deactivated blogs from years ago in the 26 eight year old men/Marshalate fandom talking about how the most popular marshals are the Lannes/Ney/Murat Trio and it’s rare to see the others

I’d say that Soult, Bessieres and Davout are getting in on the action these days - I do mentally rotate Soult a lot, and these six pretty much line up with my main favourites (though I am open to being convinced to love more - Victor has some very nice drama going on, Owl Man is a hoot, I need more Masséna and Augereau the dnd characters)

But also if we think of Lannes/Ney/Murat as the feckless reckless brave idiot trio

Soult/Bessieres/Davout are like. The Seemingly calmer and measured trio

but they can hold a lot of Drama too

also if we post three more lannap fanfics we can temporarily overtake the napoleon/Alexander shippers on ao3 /im kidding i appreciate all the fanfics and don’t actually mean any ship war seriousness

#cadmus rambles#cad rambles about dead Frenchmen on main#Junot is like an honorary marshal#the Davout biography better not fall in the ocean again#marshalate fandom#napoleonic fandom

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

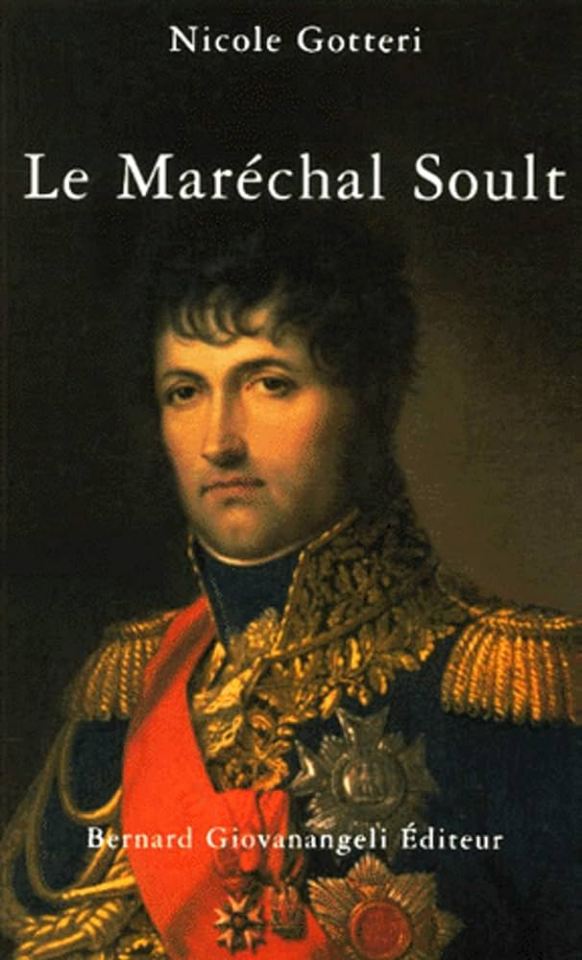

I haven’t read any biographies of Soult. If I were to read one, would you recommend that Nicole Gotteri's book on him be the one to read?

Absolutely. Especially as I am unaware of any other similar in-depth study on Soult's life.

If possible, get this one:

N. Gotteri, "Le Maréchal Soult", éditions B. Giovanangeli, Paris, 2000

I've only borrowed that one from a library and found it had some additions (in particular more images) compared to the older book I own ("Le Maréchal Soult, maréchal d'empire et homme d'état", éditions La Manufacture, Besançon, 1991)

Nicole Gotteri is or was (she may be retired by now) an archiviste, working in the Archives Nationales, in charge of the napoleonic era documents. And she really dug into those 😋. So, unlike in many popular history books, you will usually find she cites her sources very thoroughly, i.e., if you want to fact-check her or just read up some stuff yourself, it's very easy. She even unearthed some letters to and from Soult that had been missing.

Like many (most?) biographers, she is quite in love with her subject though. I've noticed that there are a couple of instances when she follows Soult's own memoirs without giving a secondary source. And in order to exonerate Soult, she often is very harsh on both Berthier and Ney (not even talking about Joseph 😁). Just to give you a fair warning.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m still losing it over that nextshark article about the trend of chinese people making “white people food” for work lunches and calling them “the lunch of suffering.” white people secret i was notorious among my friend group in high school for opening up my lunchbox and inside there was a single loose unseasoned hardboiled egg

#i packed my own lunches don’t worry#i prefer a series of snacks across the afternoon to one big meal so the egg was the first of many#but i did just gulp that thing down like a snake no salt no pepper no nothing and go back to reading a biography of napoleon or whatever#ryddles

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cochrane's Coastal Raids by Terence Lee.

During the three years that Marryat served on board the Impérieuse he was witness to more than fifty engagements, in which he took as active and prominent a part as a lad of his age could be expected to do; and in the winter that followed his joining it, Lord Cochrane captured and destroyed three French national vessels and twelve merchant ships; he also demolished Fort Roquette, at the entrance of Arcasson.

— Florence Marryat, The Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#lord thomas cochrane#thomas cochrane#napoleonic wars#royal navy#naval history#hms imperieuse#naval art#age of fighting sail#biography#life and letters#midshipman marryat

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

*Book Report!*

Napoleon, A Biography by Frank McLynn

I would just like to start off by saying that I do not recommend this book, unless you've already exhausted the 300+ other books in the world about Napoleon, then sure, why not.

It took me about 6 months to read, which is actually quick for me for a book of its size (668 pages) with life and everything going on but sometimes I just had to press on, or I really would have to be coming back as a ghost to read the other books! I'm just glad it's over 😮💨

My biggest problems were the reoccurring words and themes that repeated themselves so tirelessly. I dare someone to count the times the words "Machiavelli/Machiavellian" and "oriental complex" were used. "Fabian" and "Jungian" had their moments too. Then there were all the psychoanalytical Freudian reasons behind every little thing Napoleon did. It was because he felt this way about his mother or this way about his eldest brother. His views on women and his hidden homosexuality... These were the reason for everything apparently. In fact, you could make a drinking game out of these if you have a death wish.

The book definitely had its redeeming moments when it was actually focused on a particular battle or event. Unfortunately everything in-between was just filler speculation or spouting facts.

The end of this book was the great debate of poisoning, stomach cancer, or other reasons for Napoleon's demise. You have to forgive it for being published in 1997. The author seemed to go with Montholon being the poisoner but gave decent argument for all sides, even a myriad of different diseases it could have been. He said that "officially" stomach cancer is the cause of death since that was not a malady that the British could be accused of killing him with. It obviously ran in his family as well. They couldn't go with hepatitis or another apparently "more plausible" illness without being at fault by providing negligent medical care or effects of the climate from keeping him prisoner on St. Helena.

Read at your own risk, as these are just my opinions but let me say I've never been so glad to be done with a book!

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Help I know Tsar Alexander spoke French, but was he really better than Napoleon??

#tsar Alexander#tsar Alexander I#Napoleon#napoleonic era#book pic#ref#napoleonic#first french empire#19th century#French#France#Russia#napoleon bonaparte#frev#french revolution#Michael broers#Napoleon: the spirit of the age#Napoleon bio#Napoleon biography#history#1800s#french empire#imperial Russia

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

so, like, daddy issues?

#the '' for solved was NEEDED#solved absolutely nothing. what are you doing with a father figure that hates your ass#napoleon: a biography by frank mclynn#what do you mean “especially as a corsican” !!#napoleon bonaparte#pasquale paoli#napoleonposting#certifiedhistoryaddict

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

save me joseph fouché portrait of a politician by stefan zweig

#he avoided being arrested twice in the most absurd way possible.is this shit even real.#it feels like half of this biography is made up ngl. probably not just a feeling but honestly it's so well written thay i still love it#gonna read a more accurate biography as soon as i finish this one#frev#kinda??#napoleonic era#joseph fouché#.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is on archive.org. It was published in 1909, so okay, some wouldn't touch this book with a 10-foot pole. To me, they are the best ones. Turquan wrote the book about Napoleon's sisters that I'm reading.

Kind of a random illustration on the cover but I guess it's generic for this era of publishing.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just for fun, here are all the times in Gourgaud's diary where Napoleon laments not having Fouché shot, hanged, or guillotined (and also regrets that Louis XVIII has likewise failed in this capacity).

Source: General Gourgaud, Sainte-Hélène - journal inedit de 1815 à 1818

***

29 November 1815 – “I should have hanged him, that was my intention. If I had been victorious at Waterloo, I would have had him shot immediately.”

29 December 1815 – We speak of the news from France… His Majesty says that the King has done well to name Richelieu Prime Minister, but he should have hanged Fouché.

2 February 1816 – At 8 o’clock, His Majesty asks for me and dictates to me for a long while, then I have lunch with him. Sadness and chess. In the evening, it is said that Fouché has been executed. The Emperor exclaims: “I always predicted he’d eventually be hanged.”

16 February 1817 – “I am not Louis XVIII, but it has always repelled me to deal with such a man. The King should’ve had him hanged.”

11 July 1817 – “I cannot understand the current conduct of Paris. Had I stayed there after Waterloo, if I had cut off a hundred heads, that of Fouché the first, I could have held on in Paris with the rabble.”

14 July 1817 – “On my return from Waterloo, I was of a mind to have Fouché’s head cut off. I’d already composed the military commission, that of the Duke d’Enghien…”

23 September 1817 – [Speaking, again, of what he should have done after Waterloo] “I should, it is true, have had Fouché shot immediately after my arrival, he was the soul of the party, his judgment would have been shouted under the windows of the deputies to whom I could have said: ‘who invokes the tricolor flag? This is a man who fled France to take refuge with foreigners and who owes his return to Paris to me. At this moment there is no salvation except in men who love their country.’ I would have ended by demanding to purge the Chamber and by hanging seven or eight of its members and, above all, Fouché.

24 September 1817 – “I should’ve had the Duke of Otranto shot, but Laffitte prevented me from doing so. Talleyrand will maintain himself, he is a man of the Revolution, he is a priest married to a whore…”

#I'm currently reading three Fouché biographies simultaneously so more Fouché content is imminent#Joseph Fouché#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#Gourgaud#Saint Helena#just Fouché things

159 notes

·

View notes