#Racism in America

Text

"It is ludicrous for the

society to believe that these temporary measures can long contain the tempers of an oppressed people.

And when the dynamite does go off, pious pronouncements of patience should not go forth. Blame

should not be placed on “outside agitators” or on “Communist influence” or on advocates of Black

Power. That dynamite was placed there by white racism and it was ignited by white racist

indifference and unwillingness to act justly."

Kwame Ture and Charles V Hamilton: Black Power- The Politics of Liberation in America, 1967

#because is it 1967 or 2024??????#the dynamite has long been lit#kwame ture#charles v hamilton#black literature#us politics#racism in america#black activism

415 notes

·

View notes

Text

July 31, 1866 - The New Orleans Massacre

The New Orleans Massacre of 1866 occurred on July 30 when a peaceful demonstration of mostly Black Freedmen was attacked by a mob of white rioters. The violence erupted outside the Mechanics Institute, where a reconvened Louisiana Constitutional Convention was taking place.

According to official reports, 38 people were killed and 146 wounded, with 34 dead and 119 wounded being Black Freedmen.

Unofficial estimates suggest even higher casualties. The perpetrators included ex-Confederates, white supremacists, and members of the New Orleans Police Force.

This tragic event expressed deep-rooted conflicts in Louisiana’s social structure and catalyzed support for the Fourteenth Amendment and the Reconstruction Act, which aimed to change social arrangements in the South

As the United States approaches what are bound to be particularly contentious November midterm elections, profound questions regarding the might and meaning of the vote in American society are seemingly everywhere. Battles over voter ID laws and felon disfranchisement, lawsuits that seek to overturn gerrymandered districts, and allegations of voter fraud and election tampering by foreign powers all demonstrate that arguments about who gets to vote and whether votes are fairly counted are central to the electoral process.

Such struggles are nothing new. Today marks the 152nd anniversary of one of the deadliest attacks on voting rights activists in American history. In New Orleans on July 30, 1866, a white mob, led by police and firemen, massacred delegates and spectators at a state constitutional convention convened to guarantee voting rights to African American men. The attack left over forty African Americans dead, over 150 wounded, and a nation reeling.

In 1864, Union forces had almost entirely liberated Louisiana from Confederate control, and the state’s all-white electorate had drafted and ratified a new state constitution that acknowledged the abolition of slavery. Still, the document sanctioned restrictions on African American civil and political rights, and in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Louisiana voters, many of whom were Confederate veterans, returned numerous Confederate officials to state and federal offices under the banner of a Democratic Party that openly proclaimed to be in favor of white supremacy. “We hold this to be a Government of white people,” the platform of the state party maintained, “made and to be perpetuated for the exclusive benefit of the white race.” Indeed, the platform announced, “people of African descent cannot be considered as citizens of the United States.” It came as no surprise that the state legislature promptly passed discriminatory laws known as Black Codes that targeted the formerly enslaved, nor that the mayor of New Orleans, former Confederate John T. Monroe, instructed city policemen to single out the formerly enslaved for arrest.

Frustrated by this ongoing racial discrimination and the resumption of Confederate rule, in 1866 leading African American suffrage activists convinced a handful of white former delegates to Louisiana’s 1864 Constitutional Convention to reconvene the convention in New Orleans, and to draft a state constitutional amendment enfranchising African American men. Their plan relied upon a technicality, namely that the motion to adjourn the 1864 Convention had contained a provision authorizing it to reconvene to pass amendments at any later date.

Supporters of universal male suffrage argued that without African American political participation, former Confederates would continue passing racially discriminatory legislation, recreating slavery in all but name. “Liberty is but a word as long as taxation, elections, and the whole political machinery are confined in the hands of an inimical race,” warned Oscar Dunn, a formerly enslaved leader among suffrage activists in the city. Activists also recognized that the vote bore profound symbolic significance. In a world where women could not vote and political participation signified manhood and status, exclusion from the polls was both emasculating and humiliating. African American men demanded “political rights,” argued black Union army veteran and future Louisiana Governor P.B.S. Pinchback, but they also demanded “to become men.”

The vote was no less meaningful to embittered Confederate army veterans, who already felt emasculated by military defeat and saw the prospect of African American enfranchisement as an amplification of that emasculation. State Democratic officials declared the reconvening of the Constitutional Convention illegal. When judicial challenges to the reconvening failed, Mayor Monroe, the police chief, and former Confederate officers secretly resolved to annihilate the convention delegates instead. They covertly enlisted hundreds of Confederate army veterans as emergency police officers, and police and fire stations received orders to prepare for a showdown on July 30, 1866.

On the morning of the convention, a jubilant parade of African American suffrage supporters carried a large American flag and followed a marching band through the streets towards the hall where the convention delegates were assembling. The marchers’ elation shifted towards apprehension as crowds of hostile onlookers began to gather. A fight broke out. Distant pistol fire cracked.

Inside the hall, the chairman called the convention to order. Realizing that they lacked a quorum, the delegates agreed to reconvene in one hour. But as delegates and spectators drifted towards the doorway as the beleaguered parade arrived, the city’s fire bell rang twelve tolls, the traditional code for summoning residents to defend the city against imminent enemy attack. As the bell fell silent, police, firemen, and white civilians surrounded the parade and the hall.

Then they opened fire.

Lucien Jean Pierre Capla, a freeborn storekeeper and Union army veteran, had brought his teenage son Alfred to witness the historic assembly. They watched rioters slaughter marchers kneeling in surrender, and mutilate their bodies. “I saw the people fall like flies,” Capla later recalled. “They shot them, and when they done that, they tramped upon them, and mashed their heads with their boots, and shot them after they were down.” Father seized son and tried to flee, but the mob tore the pair apart. Lucien Capla suffered a fractured skull and a gunshot wound; Alfred received four bullets, three knife wounds, and the obliteration of his right eye. Police threw both in jail, but both survived.

Inside the hall, Dr. A.P. Dostie, a white dentist and leading convention delegate, tried to calm the trapped delegates and spectators. “The flag will protect us!” Dostie cried from the podium. Then a bullet pierced his arm. The rioters entered the hall, firing indiscriminately. Two policemen dragged Dostie to the city’s main thoroughfare, where the mob took turns striking, clubbing, and shooting him. As Dostie lay dying, police flung his body into a cart, parading him before the cheering crowds.

When federal troops finally arrived hours later, the floor was sticky with blood. Three white delegates and more than forty African American supporters lay dead. Another 150 lay wounded. Only one white Democrat had been killed, by a policeman’s stray bullet.

Yet the attack backfired. News of the brutality swept the nation and horrified the North, galvanizing northern white support for African American political and civil rights. Republicans swept the 1866 Congressional elections. In 1867, Congress passed the First Reconstruction Act, placing the South under federal military control and calling for new constitutional conventions in which African American men could vote for delegates. Federal officials removed Mayor Monroe and other former Confederate officials from office. Louisiana’s new legislature dissolved the New Orleans’ police department and replaced it with a racially integrated force.

In November 1867, under the protection of federal troops, an interracial coalition of white, freeborn, and formerly enslaved political operatives convened another state constitutional convention in New Orleans. Delegates included survivors of the 1866 massacre. The assembly wrote one of the most radically advanced constitutions in the nation’s history. The document, which remained in force for just over a decade, guaranteed equal justice before the law, equal political and civil rights for men, and universal access to public transportation and public accommodations. It also mandated the creation of a state funded and racially integrated public education system.

Both perpetrators and victims of the 1866 Massacre recognized that the vote formed the basis of the nation’s political fabric. Yet in fighting to stamp out African American political participation, the 1866 rioters had inadvertently helped usher in a democratic revolution, the likes of which Louisiana would not see again for another century.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"These calls for “getting tough” also generated debate and bitter exchanges between different groups claiming to represent African Americans. Some critics insisted that “law and order” operated as a euphemism for anti-black and anti–civil rights sentiments. Leonard De Champs, chairman of the Harlem Chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), excoriated the NAACP, calling it “oppressive and Nazi-like for its Fascist proposals regarding law and order in the streets of Harlem and New York City’s other Black communities.” He charged that

Vincent Baker’s love for mandated jail sentences and tightened-up parole procedures conclusively proves that the NAACP is an effective enemy of the 1.2 million Black people in this city.

Floyd McKissick, a longtime civil rights activist and another leader of CORE, claimed that the NAACP’s punitive recommendations reflected the interests of the black middle class. He wrote that

the arguments used in the report of the NAACP smack suspiciously of the Ronald Reagan-George Wallace school of repressive ‘law and order,’ at any cost. They appeal to the fears and prejudices of citizens who have even a little bit worth protecting.

He pointed to “a gap of understanding between middle class and poor Blacks along economic lines” and explained that

we should know by now that the addition of more white cops in the ghetto solves nothing. The ones who suffer more from such measures are the poor blacks; not necessarily the guilty ones.

Instead of harsher punishment, McKissick called for community control:

The ghetto must be safe for its citizens, but it cannot be made so by police state tactics. All efforts must be directed toward the ending of conditions which breed crime and chaos; all efforts much be directed toward the development of a Black-orientated, Black controlled law enforcement agency—an agency dedicated to the aid and protection of Black people, not to their suppression.

During this period, a host of community groups and organizations set up treatment programs, many of which received New York City and state funds, intended to be more directly accountable to thecommunities in which they were embedded. Some grew out of churches and established community groups, while others were connected to more radical political organizing. For example, in March 1969, eighty volunteers and twenty-two drug addicts took over a three-story building in Harlem and set up a drug-treatment program. They hoped to bring attention to “the inadequacy of the state’s narcotic program and the entire health program for the black people.” The addicts involved told the New York Times that they had faced a maze of waiting lists and applications in their efforts to secure treatment. One had never heard back from a program he had applied to three years earlier in 1966. The journalist reported that all of the patients interviewed complained that the state’s drug addiction programs were “more punishment than rehabilitation.” One addict asked if “I should turn myself in to the state and be locked up for rehabilitation.” They contrasted the civic degradation of the state treatment programs with guerrilla programs, claiming that in the latter, they “talk to you like a man, not a statistic—the people really want to help you and it makes you want to help yourself.” After a police eviction order, the center was closed and the patients transferred to an “underground hospital.” In subsequent years, other groups also established treatment programs. The Young Lords, a radical group dedicated to Puerto Ricans’ self-determination, were integral to establishing a detox program at Lincoln Hospital.

Drastic fluctuations in policing further intensified frustration within urban communities. In 1969, the city initiated a major intensification in street-level enforcement of drug markets. At a press conference in September, Mayor Lindsay announced that the police department intended to shift the narcotics division’s 500-person force to the pursuit of upper-level drug arrests and direct the entire remaining patrols to prioritize narcotic arrests at the street level. This sweep produced a considerable uptick in narcotics arrests in New York City: they jumped from 7,199 in 1967 to 26,378 in 1970. Then, in 1971, at a high point in the surge of heroin use, the NYPD abandoned their campaign of intensive street-level drug policing. Police officials claimed that the policy was ineffective and expensive and resulted in low conviction rates because the court system did not have the capacity to process the arrests. The result was a dramatic fall-off in arrests. New York City police conducted over 24,025 felony drug arrests in 1970, 18,694 in 1971, 10,370 in 1972, and 7,041 in 1973."

- Julilly Kohler-Hausmann, Getting Tough: Welfare and Imprisonment in 1970s America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017. p. 57-59.

#new york#harlem#congress of racial equality#naacp#therapeutic community#drug rehab#addiction rehab#rehabilitation#failure of rehabilitation#war on drugs#substance dependence#history of addiction#history of drug use#academic quote#united states history#getting tough#reading 2022#street crime#nypd#civil rights#african americans#racism in america#african american history#heroin

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

#woke is wonderful#empathy education#teaching empathy#empathy#empowerment#charles schulz#charlie brown#Franklin#inclusiveness#black people invented everything#blacklivesmatter#black lives matter#black people#black people just existing#black people deserve better#black people built America#black people are the soul of America#racism in america#racism is disgraceful#racism is disgusting#racism is sad#racism is stupid

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"What does he know of the half-starved wreaths toiling from dawn till dark on the plantations? of mothers shrieking for their children, torn from their arms by slave traders? of young girls dragged down into moral filth? of pools of blood around the whipping post? of hounds trained to tear human flesh? of men screwed into cotton gins to die?"

Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

#incidents in the life of a slave girl#harriet jacobs#slavery#american slavery#abolition of slavery#abolitionist#liberation#liberty#freedom#racism#racism in america#human rights violations#human rights abuses#poc#black academia#black feminism#black liberation#american authors#american literature#literature#literature quotes#race theory#race and gender#race and ethnicity

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

White people don’t want gun control. If they did they’d stop fucking voting Republican but because gun control would benefit Black People; it’ll never fucking happen in America.

#us politics#us elections#tw shooting#tw gun violence#racism in America#and other countries can shut the fuck up since Black People are mistreated in every gd country

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes i do wonder about identity politics, and whether they truly serve us well. but then i remember! i live in a nasty queer progressive bubble that's not at ALL representative of reality.

If you do live in America, I can't recommend this article highly enough. Nikole Hannah Jones is inevitably going to be written down in the annals of history as one of the great writers of our time. She really truly blows the whole issue wide open, every time.

Excerpt:

Thus, the first time the court took up the issue of affirmative action, it took away the policy’s power. The court determined that affirmative action could not be used to redress the legacy of racial discrimination that Black Americans experienced, or the current systemic inequality that they were still experiencing. Instead, it allowed that some consideration of a student’s racial background could stand for one reason only: to achieve desired “diversity” of the student body. Powell referred to Harvard’s affirmative-action program, which he said had expanded to include students from other disadvantaged backgrounds, such as those from low-income families. He quoted an example from the plan, which said: “The race of an applicant may tip the balance in his favor, just as geographic origin or a life spent on a farm may tip the balance in other candidates’ cases. A farm boy from Idaho can bring something to Harvard College that a Bostonian cannot offer. Similarly, a Black student can usually bring something that a white person cannot offer.”

But, of course, a (white) farm boy from Idaho did not descend from people who were enslaved, because they were farmers from Idaho. There were not two centuries of case law arguing over the inherent humanity and rights of farm boys from Idaho. There was no sector of the law, no constitutional provision, that enshrined farm boys from Idaho as property who could be bought and sold. Farm boys from Idaho had no need to engage in a decades-long movement to gain basic rights of citizenship, including the fundamental right to vote. Farm boys from Idaho had not, until just a decade earlier, been denied housing, jobs, the ability to sit on juries and access to the ballot. Farm boys from Idaho had not been forced to sue for the right to attend public schools and universities.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today marks 3 years since George Floyd's murder. His death sparked demonstrations around the world and was the largest racial justice protests in the United States since the civil rights movement.

As we honor his life and legacy, discover from Advancement Project, Baltimore Action Legal Team (BALT), BlackOUT Collective, BYP100 (Black Youth Project 100), Dream Defenders (DD), Know Your Rights Camp (KYRC), Live Free, Organizing Black, Race Forward, and Southsiders Organized for Unity and Liberation (SOUL) how you can continue the fight for racial justice!

📸 by Faith Eselé on Unsplash

#george floyd#justice for george floyd#say his name#i can't breathe#police brutality#end police brutality#black lives matter#blm#blm movement#racial discrimination#racism#racism in america#institutional racism#systemic racism#end racism#stop racism#fight racism#anti-racism#no racism#no to racism#say no to racism#racial justice#racial equality#equality#racial equity#civil rights#social justice#human rights

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listen to this article here

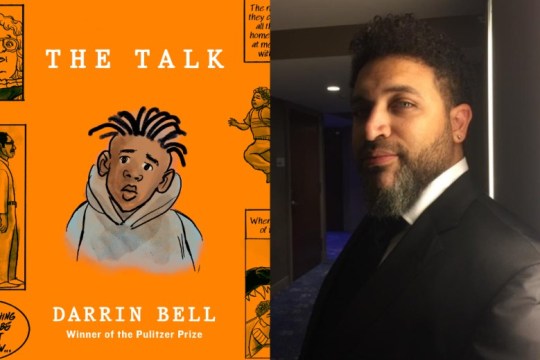

Darrin Bell, a renowned cartoonist and 2019 recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning, released his graphic memoir “The Talk” on June 6th. Throughout 352 pages, Bell recounts his own personal experiences with racism and expresses the importance of Black families having conversations about racism to prepare their children for the harsh realities of the world.

Bell explained that his motivation for creating “The Talk” stemmed from the tragic murder of George Floyd. Although he had initially been working on a different book, a profound conversation with his editor prompted him to create a work that would speak to this prevailing issue.

During a Q&A with Shelf Awareness Bell explained that he felt compelled to release the book at a time when racial discourse occupied the national spotlight, recognizing the limited duration of time in which the subject would be at the forefront of white Americans’ attention.

Launching “The Talk” with Darrin Bell

Bell drew inspiration for ‘The Talk’ through introspection on his first conversations about racism with his mother at the tender age of six, and its lasting impact on his perspective as a father, prompting him to address the subject with his son.

Bell shared that through brainstorming with his editor regarding the book’s topic he said to her, “I was six when my mom gave me the talk, and my son is six now and I’m having to deal with whether I think he’s ready for it,” to which she responded, “That’s the book.”

Aware that his son would inevitably confront the harsh realities of racism, Bell sought to arm him with the knowledge and understanding necessary to face such challenges head-on.

Initially, he grappled with providing his son honest answers about incidents of racism he inquired about. “I told him the most optimistic thing, which is that maybe this push for justice is finally going to stick, and what I didn’t tell him was that I was thinking of all the times when it didn’t stick,” Bell revealed.

Gary Trudeau, the creator of the Doonesbury comic strip, commended Bell for his ability to provide an invaluable perspective through his book.

“Bell is the Ta-Nehisi Coates of comics, an indispensable explainer of how it feels to grow up in a world that repeatedly treats you as other. The talk with my white sons boiled down to ‘Be kind.’ It’s hard to overstate the distance between that admonition and ‘Stay alive’,” Trudeau said.

Reliving trauma to share triumph

Bell shared that every scene in the book is his favorite. He explained that the first draft of “The Talk” spanned 640 pages and to decrease the page count he kept only his most exceptional work. Drawing and writing about many of the book’s events proved challenging for Bell, as it forced him to relive traumatic moments from his past.

Throughout the memoir, Bell incorporates various illustrations of vicious dogs. He revealed that his first traumatic experience involved being stalked by dogs, and he believed that incorporating them in the book served as a powerful metaphor for the emotional turmoil he endured.

“The feeling I had when those dogs were stalking me was the exact same feeling I had when I was faced with authorities when I would run into the police, and when teachers would come down on me,” Bell shared.

For Bell, the chapter in which he met his wife offered a much-needed sense of solace.

“I was going through all of these incidents that I had spent my whole life trying not to remember. So when I made it through all that dark and traumatic material and made it to the chapter with my wife it felt as if I was falling in love with her all over again,” Bell said.

Validating experiences

Ultimately, Darrin Bell aims to convey a multi-layered message to his readers. He hopes that non-Black readers, as well as those struggling to empathize with the Black community, can utilize his book as a means of stepping into his shoes.

He hopes to empower Black parents who may feel hesitant about discussing racism with their children by offering them courage through his book. Bell revealed that his father struggled to share his experiences and avoided having ‘the talk’.

Now, as a father himself, Bell understands the challenges of approaching such conversations. “He probably looked at me and saw this little kid who was still innocent, and still believed in magic and still believed that the whole world loved him. And he didn’t want to take away any of that innocence,” Bell explains.

Additionally, Bell aspires for his book to validate the experiences of children who can relate to him. He acknowledges that people often dispute accusations of racism, offering alternative explanations to dismiss or downplay these situations. With his memoir, Bell aims to provide children with comfort, assuring them that their experiences are real and not merely figments of their imagination.

#Darrin Bell’s graphic memoir ‘The Talk’ spurs conversations on race#identity#The TAlk#Black Lives Matter#Black Kids Matter#The TALK#the talk that Black Parents have with their kids about white supremacy#systemic racism#racism in america

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

February 12, 2023

Heather Cox Richardson

On February 12, 1809, Abraham Lincoln was born in Kentucky. Exactly 100 years later, journalists, reformers, and scholars meeting in New York City deliberately chose the anniversary of his birth as the starting point for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

They vowed “to promote equality of rights and eradicate caste or race prejudice among citizens of the United States; to advance the interest of colored citizens; to secure for them impartial suffrage; and to increase their opportunities for securing justice in the courts, education for their children, employment according to their ability, and complete equality before the law.”

The spark for the organization of the NAACP was a race riot in Springfield, Illinois, on August 14 and 15, 1908. The violence broke out after the sheriff transferred two Black prisoners, one accused of murder and another of rape, to a different town out of concern for their safety.

Furious that they had been prevented from vengeance against the accused, a mob of white townspeople looted businesses and burned homes in Springfield’s Black neighborhood. They lynched two Black men and ran most of the Black population out of town. At least eight people died, more than 70 were injured, and at least $3 million of damage in today’s money was done before 3,700 state militia troops quelled the riot.

When he and his wife visited Springfield days later, journalist William English Walling found white citizens outraged that their Black neighbors had forgotten “their place.” Walling claimed he had heard a dozen times: “Why, [they] came to think they were as good as we are!”

“If these outrages had happened thirty years ago…, what would not have happened in the North?” wrote Walling. “Is there any doubt that the whole country would have been aflame?”

Walling warned that either the North must revive the spirit of Lincoln and the abolitionists and commit to “absolute political and social equality” or the white supremacist violence of the South would spread across the whole nation. “The day these methods become general in the North every hope of political democracy will be dead, other weaker races and classes will be persecuted in the North as in the South, public education will undergo an eclipse, and American civilization will await either a rapid degeneration or another profounder and more revolutionary civil war….”

He called for a “large and powerful body of citizens” to come to the aid of Black Americans.

Walling was the well-educated descendant of a wealthy enslaving family from Kentucky and had become deeply involved in social welfare causes at the turn of the century. His column on the Springfield riot prompted another well-educated social reformer, Mary White Ovington, to write and offer her support. Together with Walling’s friend Henry Moskowitz, a Jewish immigrant from Romania who was well connected in New York Democratic politics, Walling and Ovington met with a group of other reformers, Black and white, in the Wallings’ apartment in New York City in January 1909 to create a new civil rights organization.

In a public letter, the group noted that “If Mr. Lincoln could revisit this country in the flesh he would be disheartened and discouraged.” Black Americans had lost their right to vote and were segregated from white Americans in schools, railroad cars, and public gatherings. “Added to this, the spread of lawless attacks upon the negro, North, South and West—even in the Springfield made famous by Lincoln—often accompanied by revolting brutalities, sparing neither sex, nor age nor youth, could not but shock the author of the sentiment that ‘government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.’”

The call continued, “Silence under these conditions means tacit approval,” and it warned that permitting the destruction of Black rights would destroy rights for everyone. “Hence,” it said, “we call upon all the believers in democracy to join in a national conference for the discussion of present evils, the voicing of protests, and the renewal of the struggle for civil and political liberty.”

A group of sixty people, Black and white, signed the call, prominent reformers all, and the next year an interracial group of 300 men and women met to create a permanent organization. After a second meeting in May 1910, they adopted a formal name, and the NAACP was born, although they settled on the centennial of Lincoln’s birth as their actual beginning.

Supporters of the project included muckraking journalists Ray Stannard Baker and Ida B. Wells, and sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, who had been a founding member of the Niagara Movement, a Black civil rights organization formed in 1905. In 1910, Du Bois would choose to leave his professorship at Atlanta University to become the NAACP’s director of publicity and research. For the next 14 years, he would edit the organization’s flagship journal The Crisis.

While The Crisis was a newspaper, a literary magazine, and a cultural showcase, its key function reflected the journalistic sensibilities of those like Baker, Wells, and especially Du Bois: it constantly called attention to atrocities, discrimination, and the ways in which the United States was not living up to its stated principles. At a time when violence and suppression were mounting against Black Americans, Du Bois and his colleagues relentlessly spread knowledge of what was happening.

That use of information to rally people to the cause of equality became a hallmark of the NAACP. It challenged racial inequality by calling popular attention to racial atrocities and demanding that officials treat people equally before the law. In 1918 the NAACP published Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889–1918, reporting that of the 3,224 people lynched during that period, 702 were white and 2,522 Black. In 1922 it took out ads condemning lynching as “The Shame of America” in newspapers across the country.

When Walter Francis White took over the direction of the NAACP in 1931, the organization began to focus on lynching and sexual assault, as well as on ending segregation in schools and transportation. In 1944 the secretary of the NAACP’s Montgomery, Alabama, chapter, Rosa Parks, investigated the gang rape of 25-year-old Recy Taylor by six white men after two grand juries refused to indict the men despite their confessions. Parks pulled women’s organizations, labor unions, and Black rights groups together into a new “Committee for Equal Justice” to champion Mrs. Taylor’s rights.

In 1946 it was NAACP leader White who brought the story of World War II veteran Isaac Woodard, blinded by a police officers after talking back to a bus driver, to President Harry S. Truman. Afterward, Truman convened the President’s Committee on Civil Rights, directly asking its members to find ways to use the federal government to strengthen the civil rights of racial and religious minorities in the country.

Truman later said, “When a Mayor and City Marshal can take a… Sergeant off a bus in South Carolina, beat him up and put out… his eyes, and nothing is done about it by the State authorities, something is radically wrong with the system.” And that is what the NAACP had done, and would continue to do: highlight that the inequalities in American society were systemic rather than the work of a few bad apples, bearing witness until “the believers in democracy” could no longer remain silent.

—

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#Racism#racism in America#NAACP#history#W.E.B. DuBois

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

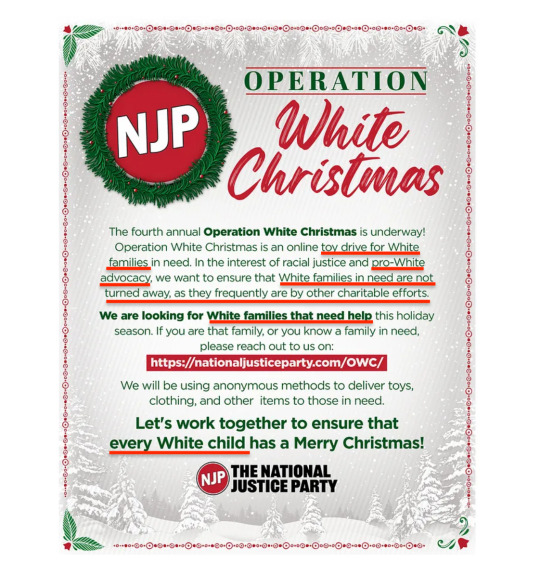

Just in case you were wondering what the Christ-hating Christians are up to this Holiday Season.

#National Justice Party#Moms for Liberty#terrorism#domestic terrorism#white supremacists#Christ haters#anti-christian#Matthew 25#happy holidays#racism#racism in America#christians#christian beliefs#Jesus wasn't white#disgusting#Anti-Americanism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once again, I welcome everyone- especially if you consider yourself an antiracist white liberal or leftist, or would like to consider yourself one- to read Martin Luther King's Letter from the Birmingham Jail (I just attached the link). It's six pages long. I'd like you to hear some of his words and ideas from his OWN mouth, rather than the whitewashed tokenized version of America's MLK used to shut down the very people and fight for justice that he would stand with.

#mlk day#martin luther king#black activists#racism in america#racism#white supremacy#us politics#world politics#current events

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

100% of White People Are Guilty of This

click the header and watch this video because you will be satisfied once you listen to what Sunn M'Cheaux has to say

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I do not underestimate the importance of the things one can do, though. One of the principal reasons I cherish this floor clerk job [as an inmate at the federal New York Detention Headquarters] is the chance to ease the really rough jolt that hits the boys the FBI brings in every night about 10 or 10:30. We clerks stay up until they come in, and after they go through the usual entry routine I show them where to get their mattresses and other bedding—which I would guess has not been cleaned in years—and the cells to which they are assigned.

Every night I rebel at the involuntary part I thus play in a jim crow institution, since the Negroes must go into one of two specified dormitories no matter how crowded it may be, or how empty one of the others. I get mad every time I see one of these kids drop his mattress wearily on the floor because there are no bunks left, but I stay on the job because I can soften the blow a little by being friendly, giving them cigarettes and generally encouraging them to keep their chins up. Many of them seem to be no more than fifteen or sixteen years old, but they get picked up anyway if they have no draft cards. The FBI tours the bars and pool halls of Harlem, I understand, and evidently operates on the theory that it is better to have a teen-age boy spend a night in jail than to take a chance of missing a possible draft-dodger!

Some of the kids are positively terrified, and they sob and cry all night. I can do little enough for them, but after they have been pushed and ordered around for hours, a little gentleness even from another convict seems to help."

- Alfred Hassler, Diary of a Self-Made Convict. Foreword by Harry Elmer Barnes. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1954 (written 1944-1945), p. 28-29.

#conscientious objectors#life inside#prisoner autobiography#world war ii#united states history#sentenced to prison#new york detention headquarters#research quote#reading 2024#american prison system#history of crime and punishment#words from the inside#new york#harlem#draft evasion#african americans#racism in america#racial segregation#jim crow#diary of a self made convict.#federal bureau of prisons#federal bureau of investigations

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#this is why we can't have nice things#lies and the lying liars who tell them#woke is wonderful#smash the patriarchy#fight the patriarchy#empowerment#racial condescension#racisim#racists#racism in America#Obama broke racists brains#Obama did not start racism#trump is a traitor#trump is fascist#trump is racist#trump is hitler#trump is a criminal#trump is a cult leader#obamacare#Obamacare is amazing#healthcare really matters#white president#black president#black lives are important#black people built america#black history#black lives fucking matter#blm#black lives matter#white people do not deserve black innovations

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

It makes me so angry how Little Richard was barely surviving all his life while so many white performers and record producers made millions of his talent,

A lot of iconic black artists suffered the same fate.

3 notes

·

View notes